Macrophages can suppress Chlamydia replication by targeting the bacteria to degradative organelles such as lysosomes.

Keywords: lysosome, autophagy, RAW cell, elementary body, reticulate body, fluorescent chlamydia, live imaging, spinning disk confocal

Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium responsible for one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases. In epithelial cells, C. trachomatis resides in a modified membrane-bound vacuole known as an inclusion, which is isolated from the endocytic pathway. However, the maturation process of C. trachomatis within immune cells, such as macrophages, has not been studied extensively. Here, we demonstrated that RAW macrophages effectively suppressed C. trachomatis growth and prevented Golgi stack disruption, a hallmark defect in epithelial cells after C. trachomatis infection. Next, we systematically examined association between C. trachomatis and various endocytic pathway markers. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse studies revealed significant and rapid association between C. trachomatis with Rab7 and LAMP1, markers of late endosomes and lysosomes. Moreover, pretreatment with an inhibitor of lysosome acidification led to significant increases in C. trachomatis growth in macrophages. At later stages of infection, C. trachomatis associated with the autophagy marker LC3. TEM analysis confirmed that a significant portion of C. trachomatis resided within double-membrane-bound compartments, characteristic of autophagosomes. Together, these results suggest that macrophages can suppress C. trachomatis growth by targeting it rapidly to lysosomes; moreover, autophagy is activated at later stages of infection and targets significant numbers of the invading bacteria, which may enhance subsequent chlamydial antigen presentation.

Introduction

C. trachomatis is one of the most common causes of sexually transmitted diseases in the world, which can lead to serious complications, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and fatal ectopic pregnancy [1]. C. trachomatis is a gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium that is highly adapted to live inside epithelial cells [1]. The life cycle of C. trachomatis involves two phases: the extracellular, infectious yet dormant form known as the EB and the intracellular, noninfectious reproductive form known as the RB [2]. The EB has a diameter of 0.2–0.4 μm and contains electron-dense nuclear material and a rigid cell wall that is well-suited for extracellular survival [3]. The size of a RB ranges from 0.5 to 1.0 μm, and it has less electron-dense nuclear material and a more flexible cell wall than an EB [3]. Upon invasion into epithelial cells, the EB differentiates into the noninfectious RB form and replicates within a vacuolar structure called the inclusion. The RB can differentiate back into the infectious EB form and lyse or extrude from epithelial host cells for dissemination, 2–3 days postinfection [4, 5].

Within the first 30 min of infection in epithelial cells, markers from the host plasma membrane found on the C. trachomatis inclusion are removed [6]. Host dynein motors are then recruited to the inclusion to enable its movement toward the microtubule-organizing center [7]. To facilitate their replication process, host cell-derived lipids, including sterols, sphingolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingomyelin, and cholesterol-rich vesicles from the Golgi, are intercepted by the C. trachomatis inclusion [8, 9]. To maintain optimal growth conditions within the host cell, C. trachomatis has evolved the ability to disrupt various host cell processes. Recent studies showed that C. trachomatis can secret CPAF to cleave host Golgin84 and cause Golgi fragmentation, which significantly enhanced its ability to capture Golgi-derived lipids and bacterial replication [10, 11].

Among the various effector proteins produced by C. trachomatis, the Inc protein family has been suggested to act as the central regulators of bacteria–host interactions [12]. IncG can recruit Rab6, Rab11, and Rab14 to the inclusion, which have been suggested to play key roles in intercepting Golgi-derived vesicles [13, 14]. Unlike the recruitment of exocytic Rabs to Chlamydia inclusions, endocytic markers, such as EEA1 (early endosomes), Rab5 (early endosomes) and Rab7, and LAMP1 (late endosomes/lysosomes), are absent on the inclusions in epithelial cells [4, 15]. Interestingly, Parachlamydia acanthamoeba, a Chlamydia-like bacterium, resides in a compartment that acquires EEA1, Rab7, and LAMP1 during its maturation in macrophages [16]. However, in-depth examination of the intracellular trafficking of C. trachomatis in immune cells, such as macrophages, has not been performed to date.

Our study, using epifluorescence, spinning disk confocal, and TEM, investigated the maturation process of C. trachomatis inclusions in macrophages. We observed that in macrophages, C. trachomatis EBs are rapidly targeted to lysosomes. Inhibition of lysosomal acidification or disruption of Rab7 function in macrophages led to a significant increase in C. trachomatis replication. During later stages of infection, some C. trachomatis compartments were positive for the autophagy marker LC3; moreover, EBs frequently resided in double-membrane-bound vacuoles resembling autophagosomes. Together, our results demonstrate that immune cells, such as macrophages, can combat C. trachomatis infection using endocytic and autophagic machineries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and reagents

RAW macrophages and HeLa cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. (Manassas, VA, USA). DMEM and FBS were from Wisent (St. Bruno, Quebec, Canada). FuGENE-HD was purchased from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Rat (ID4B) and mouse (H4A3) anti-LAMP1 antibodies were from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa City, IA, USA). GM130 antibody was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA), Golgin84 antibody was from Abnova (Taipei City, Taiwan), phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), and 4G10 phosphotyrosine antibody was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). TARP and Chlamydia antibodies were generous gifts from Dr. David Hackstadt (U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Hamilton, MT, USA). Cy2-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). DRAQ5 was from Cell Signaling Technology. LysoSensor Green and BODIPY FL C5-ceramide were purchased from Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada).

Cell culture, transfection, and C. trachomatis infection

HeLa and RAW cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Primary human macrophages were derived from PBMCs, as described previously [17]. RAW, primary human macrophages, and HeLa cells were grown to 70–80% confluency in DMEM on coverslips at 37°C, supplied with 5% CO2. For transient expression of constructs, cells were transfected using FuGENE-HD overnight. DNA constructs used were: Rab5-GFP, Rab5 S34N-GFP (DN), Rab5 S34N-mCherry (DN), Rab7-GFP, Rab7 T22N-GFP (DN), and LC3-GFP-RFP. Identity of each construct was confirmed by sequencing.

C. trachomatis serovar L2 was propagated in HeLa cells and purified using a Gastrografin step gradient, as described previously [18]. The purified EBs were stored as small aliquots in SPG buffer at −80°C until use. To generate DRAQ5-labeled EBs, aliquots of purified EBs were pooled together, and DRAQ5 was diluted in SPG buffer and incubated with purified EBs at a final concentration of 1 μM for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The resulting DRAQ5-labeled EBs were stored in aliquots at −80°C until use. To generate HK EBs, several purified EB aliquots were combined and placed in an 80°C water bath for 50 min. The resulting HK EBs were stored directly in small aliquots at −80°C or labeled with DRAQ5 for 10 min first and then stored at −80°C until use. Efficacy of the HK process was assessed by infecting HeLa cells with HK EBs for 72 h, and no inclusion was observed in the host cells (not shown).

For fixed studies, purified EBs were added to HeLa and RAW cells, and infection was synchronized by centrifugation at 300 g for 15 min. Cells were washed with PBS to remove unbound EBs. For live cell imaging experiments, a 35-mm glass-bottom dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA) could not be centrifuged to synchronize infection as a result of the lack of appropriate adaptors. The infection was synchronized by removing culture media from the dish and adding 30 μl fluorescently labeled EBs directly to the cells for 1 min before adding culture media back. As a result of the low volume of liquid present, many EBs attached to the host cells very quickly. In experiments where different cell lines were compared, the same aliquots of EBs were diluted and used to infect the different cell lines.

For overnight inhibition of lysosome acidification, RAW cells were pretreated with 4 nM bafilomycin A1 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h before infection with C. trachomatis. Bafilomycin was kept in the culture media at 4 nM throughout the infection until cells were fixed at 24 h.

Immunofluorescence

RAW cells, human macrophages, and HeLa cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 20 min. Cells were first stained with rabbit anti-EB and Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies to label external EBs. Cells were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS containing 100 mM glycine for 20 min. After permeabilization, cells were washed and blocked with 5% FBS for 1 h. Cells were then incubated with primary antibodies in PBS with 1% FBS for 1 h. Primary antibody dilutions used were: EB (1:200), GM130 (1:200), and LAMP1 antibodies ID4B (1:4) and H4A3 (1:50). All cells were stained with DAPI to visualize the nucleus. Cells were washed and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies, prior to mounting and imaging. Slides were imaged with point-scanning confocal microscopy using an LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA), epifluorescence microscopy using an inverted Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss), or a WaveFX-X1 spinning disc confocal (Quorum Technologies, Ontario, Canada).

Western blotting

HeLa and RAW cells were infected with EBs for indicated time-points before cell lysates were collected in RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.15 mM NaCl, 0.9% SDS, phosphatase inhibitor, and protease inhibitor cocktails. Samples were run on SDS polyacrylamide gels before transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and probed with anti-TARP (1:1,000), anti-4G10 (1:1,000), anti-Golgin84 (1:1,000), or anti-phospho-S2448-mTOR antibody (1:1,000). HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was added for 1 h, and signals were detected with chemiluminescent reagents (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Blots were imaged using Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS and analyzed with ImageJ.

Live cell imaging

Early endosome (Rab5-GFP), late endosome, and lysosome (Rab7-GFP, LAMP1-GFP, or mCherry) and autophagosome (LC3-GFP-RFP) markers were transfected overnight in RAW cells before live cell imaging. LysoSensor Green was added to RAW cells at 1 μM for 1 min to label acidic compartments before the cells were washed twice with fresh media. Rapid time-lapse imaging was carried out using WaveFX-X1 spinning disc confocal with a stage-top incubation system creating a 37°C with 5% CO2 environment. Images were acquired every 800–900 ms using a Hamamatsu electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera. For live ceramide trafficking experiments, HeLa and RAW cells were similarly infected with purified EBs for 24 h. BODIPY FL C5-ceramide complexed to BSA was incubated with infected cells at 5 μM concentration for 30 min. Cells were subsequently washed three times to remove excess ceramide and imaged within 30 min. The imaging microscope was controlled by MetaMorph, and movies were edited using Volocity.

TEM analysis of autophagosome–EB interactions

After infecting RAW cells with live or HK EBs for 6 or 9 h, the cells were fixed in 2% gluteraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorenson's phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, for 2 h. Cells were then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, 1.25% potassium ferrocyanide in sodium cacodylate buffer at room temperature for 45 min, stained for 30 min with 1% uranyl acetate in water, and then dehydrated and embedded in Epon resin. Approximately 70–80 nm sections were collected onto copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Sections were viewed using a Hitachi H-7500 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi Canada, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Subcellular compartments containing electron-dense EBs were quantified as autophagosomes or autolysosomes/lysosomes. The quantification criteria for autophagosomes and autolysosomes/lysosomes were defined previously [19]. Briefly, double-membrane-bound compartments containing undigested cytoplasmic materials were scored as autophagosomes, whereas single-membrane-bound compartments containing cytoplasmic materials were scored as autolysosomes/lysosomes.

C. trachomatis growth assay

RAW and HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis EBs at a similar MOI as described above. Host cells were scraped at 30 hpi, and lysates were stored at −80°C. The lysates from RAW and HeLa cells were used to reinfect a new culture of HeLa cells that had been grown to equal confluency. Reinfected HeLa cells were fixed at 24 hpi, immunostained, and analyzed by epifluorescence microscopy to quantify the growth of C. trachomatis in macrophage and HeLa cells.

Statistical analysis and quantification

All experiments were repeated at least three times, and Student's t test was used to determine statistical significance. P < 0.05 was used as the significance cut-off. Synchronized movements of overlapping EBs and subcellular compartment markers in time-lapse movies were quantified as positive associations. However, if EBs and fluorescent markers only overlapped in one frame throughout the time lapse, no association was scored. For fluorescent ceramide trafficking quantifications, inclusions containing C. trachomatis with visible ceramide decorating membrane of individual bacterium were quantified as positive, whereas inclusions that were devoid of bacteria with visible ceramide incorporation into chlamydial cell membrane were quantified as negative.

RESULTS

Internalization rates of C. trachomatis are similar between epithelial cells and macrophages

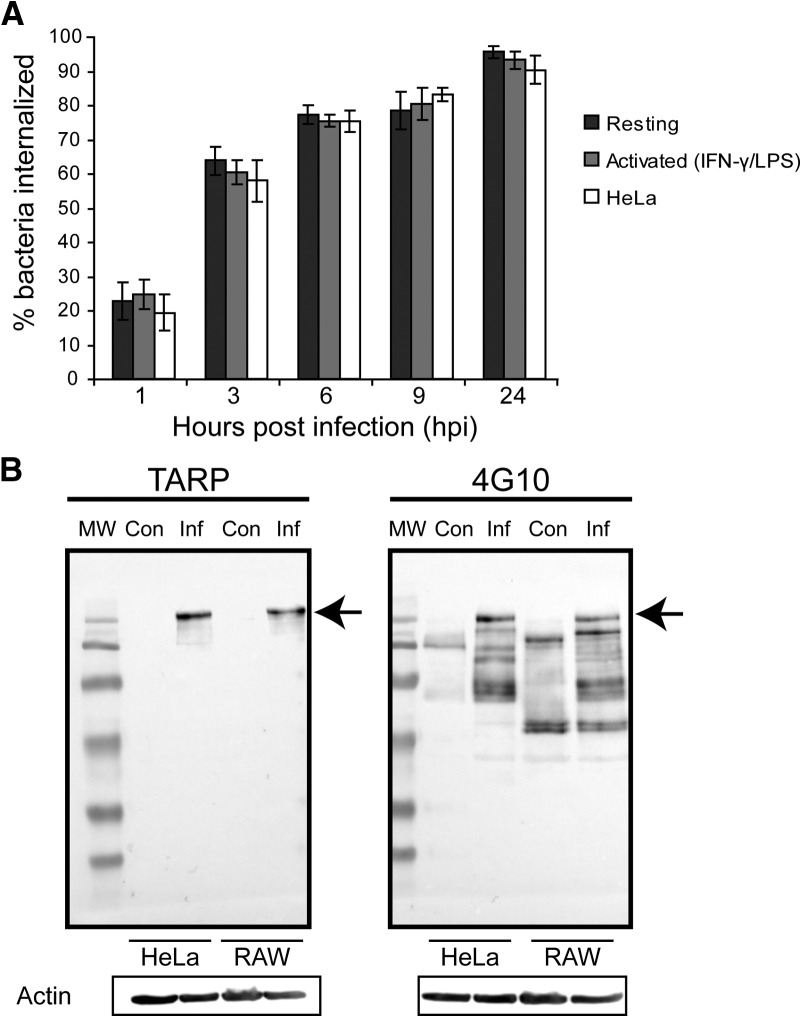

To first determine if macrophages internalized C. trachomatis differently than epithelial cells, we compared the rates of bacteria uptake between the two cell types. HeLa (epithelial) and RAW (macrophage) cells were infected with C. trachomatis EBs at identical MOIs. Cells were fixed at various time intervals over a 24-h period and immunostained for intracellular and extracellular bacteria. In infected macrophages, many EBs were bound on the surface within the 1st h, with >60% internalized 3 hpi and >75% by 6 hpi (Fig. 1A). The rate of internalization of C. trachomatis EBs in HeLa cells closely mirrored that of RAW cells (Fig. 1A). Exposure of macrophages to IFN-γ and LPS induces potent, classical activation of macrophages, which up-regulates antimicrobial activities in macrophages, including enhanced binding, phagocytosis, and clearance of microbes [20–25]. Surprisingly, infection of LPS and IFN-γ-activated macrophages also exhibited a similar rate of EB internalization to that of resting macrophages and HeLa cells (Fig. 1A). To confirm that C. trachomatis induced its own uptake in HeLa and RAW cells, we measured the levels of phospho-TARP, a key bacterial effector protein involved in EB internalization [26]. TARP becomes activated when it is phosphorylated after being injected into the host cytosol [26–28]. As a result of the lack of phospho-specific TARP antibody, phospho-TARP was detected using duplicate blots of total TARP and 4G10 antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, as carried out by previous studies [26–29]. Similar levels of phospho-TARP were detected in HeLa and RAW cells (Fig. 1B). Together, these results suggested that C. trachomatis was internalized into macrophages at a similar rate as in epithelial cells.

Figure 1. Internalization of C. trachomatis EBs is similar among resting, activated RAW macrophages, and HeLa cells.

(A) Quantification of the percentage of EBs internalized in resting, activated (IFN-γ- and LPS-stimulated) RAW macrophages, and HeLa cells over time. Cells were fixed and immunostained for external and total EBs before imaging with an epifluorescence microscope. Error bars indicate sem from three independent experiments (n>30/experiment). (B) Phospho-TARP was visualized using total TARP (left) and 4G10 anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (right) on replicate blots. Actin was used as a loading control. HeLa and RAW cells were infected for 30 min at MOIs of 200 before lysates were taken. TARP was phosphorylated to the same extent in C. trachomatis-infected (Inf) HeLa and RAW cells (arrows), compared with uninfected controls (Con), suggesting Chlamydia could induce its own uptake into HeLa and RAW cells. At least three independent experiments were performed, and a representative blot is shown.

Golgi stacks are recruited to C. trachomatis inclusions in epithelial cells but not in macrophages

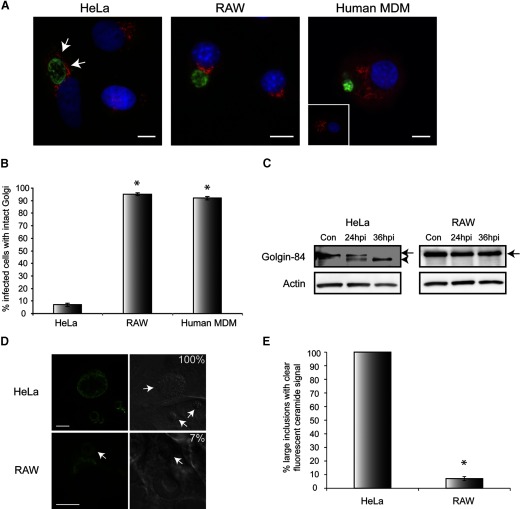

We next investigated the nature of the intracellular C. trachomatis compartments in macrophages. In epithelial cells, Chlamydia inclusions subvert Golgi-derived vesicles and manipulate the Golgi architecture [8–10]. RAW and HeLa cells were infected with C. trachomatis EBs for 24 h and then fixed and immunostained for Chlamydia and GM130 to demarcate the Golgi. In HeLa cells, GM130-positive Golgi stacks closely surrounded the inclusions and were displaced from their normal perinuclear localization. Less than 10% of HeLa cells showed normal, intact Golgi at 24 hpi (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, >90% of infected RAW cells had normal, intact perinuclear Golgi staining at 24 hpi, even in the rare cells that contained large inclusions (Fig. 2A and B). Interestingly, Golgi distribution was not altered after C. trachomatis infection in human MDMs. Similar to RAW cells, >90% of Chlamydia-infected human macrophages showed normal Golgi distribution (Fig. 2A and B). Golgi morphology was intact in all uninfected HeLa, RAW, and MDM cells (data not shown). Consistent with this observation, cleavage of Golgin84, which leads to Golgi stack disruption in epithelial cells [10], occurred in HeLa but not in RAW cells (Fig. 2C). To directly assess the ability of C. trachomatis inclusions to intercept Golgi-derived lipids, the trafficking of fluorescent ceramide to Chlamydia inclusions was investigated in infected HeLa and RAW cells. Whereas every Chlamydia inclusion was brightly labeled with ceramide in HeLa cells, only a small number of large inclusions in RAW cells obtained substantive ceramide signals (Fig. 2D and E). Together, these results indicate that macrophages could prevent C. trachomatis-induced Golgi disruption, which was correlated with decreased Golgi-derived lipid interception.

Figure 2. Disruption of host cell Golgi apparatus by C. trachomatis occurs in HeLa cells but not in RAW and primary human MDMs.

(A) Immunofluorescence images of EBs (green) and the Golgi protein GM130 (red) in Chlamydia-infected HeLa, RAW, and human MDMs at 24 hpi. An uninfected human MDM is shown in the inset to demonstrate the naturally dispersed Golgi phenotype in these cells. Arrows indicate the recruitment of Golgi stacks around the inclusion in HeLa cells. (B) Quantification of the percentage of infected cells with normally distributed Golgi in Chlamydia-infected HeLa, RAW, and human MDMs at 24 hpi. Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments (n>30/experiment). (C) HeLa and RAW cells were infected identically for indicated periods. Western blot revealed that Golgin84 was cleaved (arrowhead) in Chlamydia-infected HeLa cells but not in RAW cells (arrows). Actin was used as a loading control. At least three independent experiments were performed, and a representative blot is shown. (D) Green BODIPY C5 ceramide was used to assess interception of Golgi-derived vesicles by C. trachomatis inclusions (arrows) in HeLa and RAW cells at 24 hpi. Chlamydia inclusions could intercept ceramide in HeLa and RAW cells; however, the inclusion ceramide signal was much lower in RAW cells whose Golgi ceramide signal was still pronounced. (E) Only 7% of large inclusions in RAW cells were able to co-opt ceramide to the same extent as inclusions in HeLa cells, whereas 100% of inclusions in HeLa cells obtained bright ceramide signals (n>60/experiment for RAW cells and n>70/experiment for HeLa cells). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Original scale bars = 10 μm.

C. trachomatis is rapidly targeted to lysosomes in macrophages

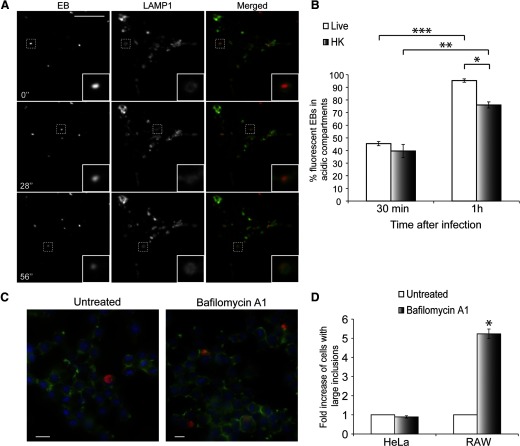

As C. trachomatis was not able to efficiently modify the Golgi in macrophages, we examined the maturation of this compartment to see if it interacted with the endocytic organelles. In epithelial cells, C. trachomatis EBs reside in vacuoles that are isolated from the host cell's endocytic machinery to avoid fusion with lysosomes [4, 5, 15]. To investigate whether a similar mechanism exists in macrophages, we generated fluorescently labeled C. trachomatis EBs using a DNA-binding dye, DRAQ5. We validated this technique by determining the viability of these bacteria in HeLa cells. First, we confirmed that most of the labeled EBs entered HeLa cells by 3 hpi based on external EB staining (data not shown). In addition, many large Chlamydia inclusions formed in HeLa cells infected with these fluorescently labeled EBs at 24 hpi, suggesting the labeled EBs were still viable (data not shown). RAW cells transfected with LAMP1-GFP were infected with DRAQ5-labeled EBs and imaged within 30 min of infection. Surprisingly, many of the fluorescent EBs associated and moved synchronously with LAMP1-GFP compartments (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Movie 1) within the first 30 min of infection. To confirm this result, we labeled acidic compartments in RAW cells with LysoSensor Green and infected these cells with DRAQ5-labled live or HK EBs. Quantification of rapidly acquired time-lapse images revealed that ∼45% of live and ∼40% of HK EBs associated with acidic compartments within the first 30 min of infection. After 1 h of infection, ∼95% of live and ∼76% of HK EBs associated with acidic compartments (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these results, when we inhibited lysosome acidification with bafilomycin, there was a fivefold increase in the number of large Chlamydia inclusions in RAW cells (Fig. 3C and D). These findings suggested that C. trachomatis EBs were rapidly transported to lysosomes, and their growth was suppressed significantly by lysosomal acidification.

Figure 3. C. trachomatis EBs are targeted rapidly to lysosomes in infected RAW macrophages.

(A) Purified EBs were labeled with DRAQ5 and added to RAW cells transfected with LAMP1-GFP. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse images were taken within the first 30 min of infection. The majority of EBs associated with LAMP1-positive compartments. Numbers indicate seconds after start of imaging. Insets are magnifications of the dotted regions, which outline various EBs that associate with LAMP1. (B) Acidic compartments in RAW cells were labeled with LysoSensor Green. DRAQ5-labeled live or HK EBs were added to RAW cells, and short time-lapse movies were taken to quantify association between EBs and acidic compartments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001, respectively (n>100/experiment for live and HK EBs). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. (C) Epifluorescence images of RAW cells pretreated with bafilomycin A1 for 1 h prior to infection, which was carried out for 24 h in the presence of bafilomycin A1 before fixation. Cells were stained for actin (green), EBs (red), and nuclei (blue). (D) Quantification of fold increase of cells with large inclusions after bafilomycin treatment. *P < 0.05. Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments (n>1000/experiment). Original scale bars = 10 μm.

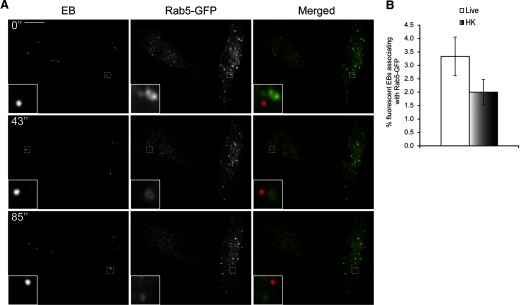

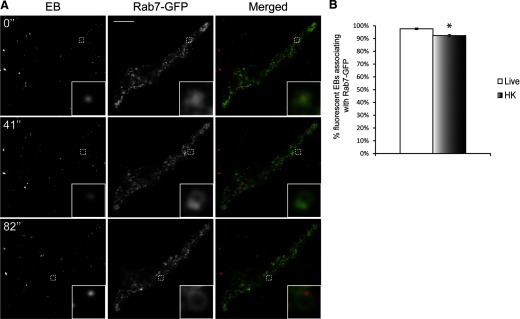

C. trachomatis compartments frequently associate with Rab7 but not Rab5 in macrophages

As we observed a rapid targeting of fluorescent EBs to lysosomes, we next determined which of the Rab-GTPases were involved in this process. Rab5 directs compartments toward fusion with early endosomes [30, 31], whereas Rab7 is critical for late endosome/lysosome recruitment [30, 32]. Rab5-GFP appeared as distinct vesicles in macrophages, as described previously [33] (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, only <5% of live- or HK-fluorescent EBs associated with Rab5-GFP, even within the first 30 min of infection (Fig. 4A and B and Supplemental Movie 2). In contrast, 98% of live and 93% of HK DRAQ5-labeled EBs associated with Rab7-GFP compartments in RAW macrophages within 30 min of infection (Fig. 5A and B and Supplemental Movie 3).

Figure 4. C. trachomatis vacuoles rarely associate with Rab5 in RAW macrophages.

(A) DRAQ5-labeled EBs were used to infect RAW cells transiently expressing Rab5-GFP, and the cells were imaged live with spinning disk confocal microscopy within the first 30 min of infection. Numbers indicate seconds after start of imaging. Insets are magnifications of the dotted areas, which outline different EBs not associating with Rab5. (B) The percentages of live- or HK-fluorescent EBs associating with Rab5-GFP were quantified. Live and HK EBs rarely associated with Rab5-GFP (n>100/experiment for live and HK EBs). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. Original scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 5. C. trachomatis vacuoles frequently associate with Rab7-GFP in macrophages.

(A) DRAQ5-labeled EBs were used to infect RAW cells expressing Rab7-GFP, and the cells were imaged live with spinning disk confocal microscopy within 30 min of infection. Numbers indicate seconds after start of imaging. Insets are magnifications of the dotted areas, which outline different EBs that associate with Rab7. (B) The percentages of live- or HK-fluorescent EBs associating with Rab7-GFP were quantified. Live and HK EBs frequently associated with Rab7-GFP. *P < 0.05 (n>100/experiment for live and HK EBs). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. Original scale bar = 10 μm.

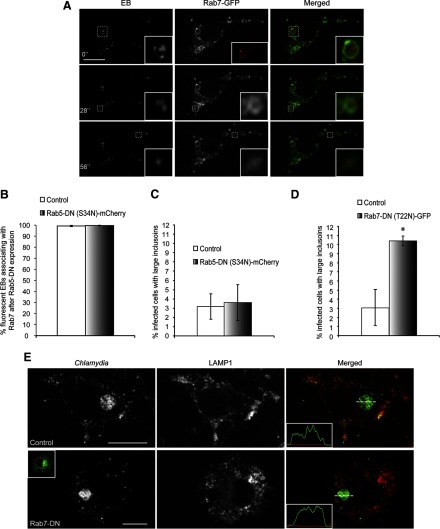

To confirm that Rab5 did not play an important role in targeting EBs to late endosomes and lysosomes, we cotransfected RAW cells with Rab5-DN-mCherry [34, 35] and Rab7-GFP and carried out infections with DRAQ5-labeled EBs. Time-lapse imaging of these cells demonstrated that even after Rab5-DN expression, >99% of live- and HK-fluorescent EBs still localized to Rab7-GFP compartments within the first 30 min of infection (Fig. 6A and B). Consistent with these findings, Rab5-DN-mCherry expression did not lead to significant changes in the number of macrophages containing large C. trachomatis inclusions at 24 hpi. To assess the functional role of Rab7 in C. trachomatis trafficking in macrophages, Rab7-DN-GFP [36] was transfected into RAW macrophages. Cells were fixed and immunostained for EBs at 24 hpi. Expression of DN-Rab7 significantly increased the number of RAW cells containing large inclusions compared with nontransfected cells (Fig. 6D); moreover, spinning disk confocal and line-intensity profile analysis revealed that large inclusions in untransfected and cells expressing Rab7-DN-GFP did not colocalize with LAMP1 (Fig. 6E). These results suggested that the recruitment of late endosomes/lysosomes to C. trachomatis inclusions was critical for limiting the growth of C. trachomatis in macrophages.

Figure 6. Expression of DN Rab7, but not Rab5, leads to increased C. trachomatis replication in macrophages.

(A) DRAQ5-labeled EBs were used to infect RAW cells cotransfected with Rab5-DN-mCherry (inset, red) and Rab7-GFP. Cells were imaged live with spinning disk confocal microscopy within 30 min of infection. Numbers indicate seconds after start of imaging. Insets are magnifications of the dotted areas, which outline different EBs that associate with Rab7. (B) The percentages of live- or HK-fluorescent EBs associating with Rab7-GFP were quantified. Live and HK EBs associated very frequently with Rab7-GFP in cells expressing Rab5-DN-mCherry (n>100/experiment for live and HK EBs). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. (C) Quantification of the percentage of infected RAW cells with large inclusions after transfection with Rab5-DN-mCherry. Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments (n>30/experiment). (D) Expression of Rab7-DN-GFP caused a slight yet significant increase in the percentages of RAW cells with large inclusions. *P < 0.05. (E) Spinning disk confocal images of immunostained cells demonstrated that large C. trachomatis inclusions in control and cells expressing Rab7-DN-GFP (inset, green) did not associate with LAMP1. Original scale bars = 10 μm.

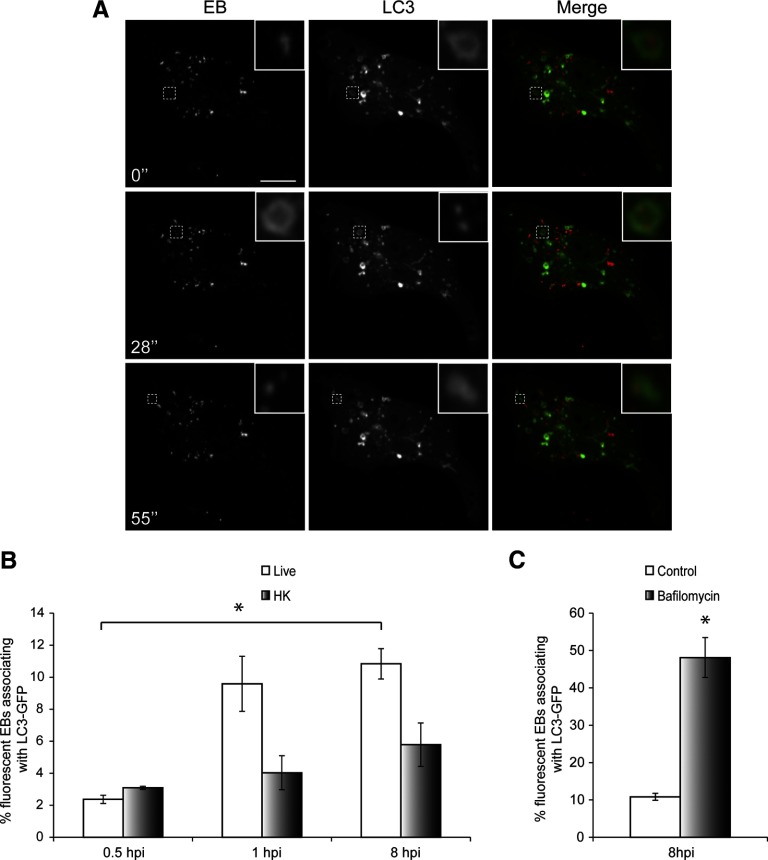

C. trachomatis associates with the autophagy marker LC3 in macrophages

Autophagy is an intracellular process that enables the host cell to recycle intracellular components and can provide protection against pathogens [37, 38]. LC3 is the most commonly used marker for autophagosomes in microscopy studies [39]. To determine whether autophagy plays a role in C. trachomatis vacuole trafficking in macrophages, we transfected RAW cells with LC3-GFP, followed by infection with DRAQ5-labeled EBs. Cells were imaged live with spinning disk confocal at various times after infection. We observed a small fraction of live-fluorescent EBs that associated with LC3-GFP in macrophages, and this fraction of EBs increased significantly by 8 hpi (Fig. 7A and B and Supplemental Movie 4). As autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, LC3-GFP signal is destroyed as a result of degradation [40, 41]. Consistent with these results, when we blocked acidification of lysosomes with bafilomycin for 3 h to protect LC3-GFP signal from degradation, the percentage of live-fluorescent EBs associating with LC3-GFP increased significantly to almost 50% (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. C. trachomatis compartments associate with autophagy marker LC3 in macrophages.

(A) RAW cells transfected with LC3-GFP were infected with DRAQ5-labeled EBs, and spinning disk confocal time-lapse images were taken 8 hpi. Numbers indicate seconds after start of imaging. Insets are magnifications of the dotted areas. (B) The numbers of live- or HK-fluorescent EBs associating with LC3-GFP at various times after infection were quantified (n>90/experiment for live and HK EBs). (C) Bafilomycin was added to infected RAW cells at 5 hpi and incubated with the cells for 3 h at the concentration of 400 nM. Spinning disk confocal time-lapse images were taken at 8 hpi, and the percentage of fluorescent EBs associating with LC3-GFP was quantified (n>40/experiment). Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Original scale bar = 10 μm.

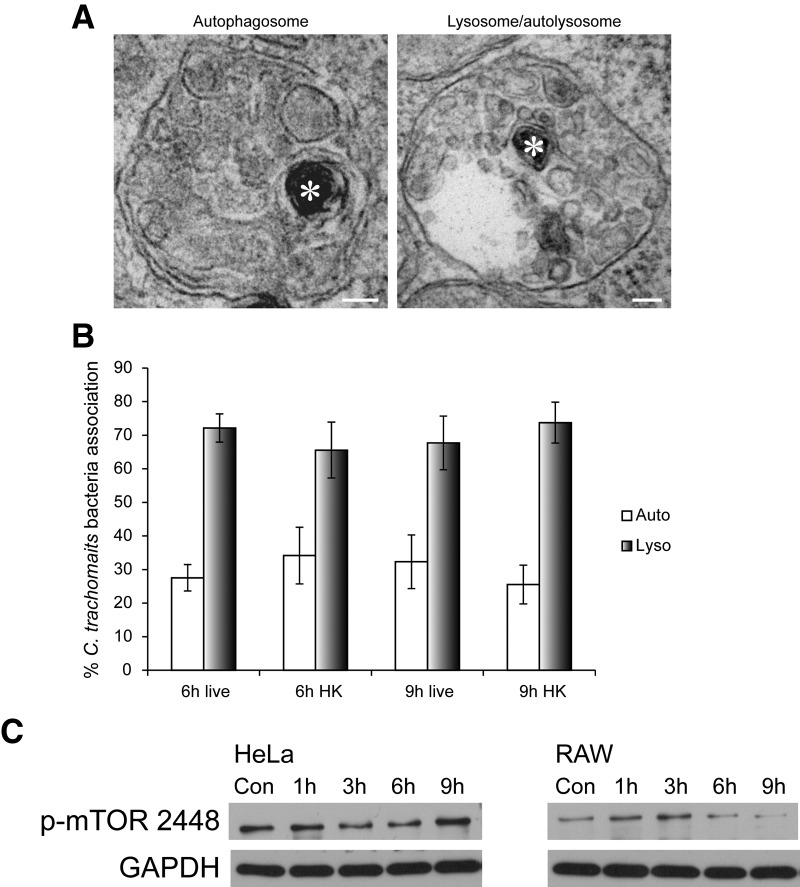

To confirm the LC3-GFP association results at a higher resolution, the same experiments were performed, and the samples were examined using TEM. C. trachomatis EBs were identified by TEM using previously established ultrastructural characteristics of the bacteria [42]. In macrophages, live and HK EBs were observed routinely in large, double-membrane-bound, multivesicle-containing compartments (Fig. 8A), indicative of autophagosomes [43]. In addition, >97% of live and HK EBs were found in autophagosomes or autolysosome/lysosomes at 6 and 9 hpi (Fig. 8B). To determine how autophagy is regulated in response to C. trachomatis infection in macrophages, we examined the levels of phospho-mTOR (S2448), an endogenous negative regulator of autophagy [44]. The levels of phospho-mTOR (S2448) did not decrease significantly over time in HeLa cells following C. trachomatis infection (Fig. 8C), whereas this repressor of autophagy started to decrease 6 hpi in macrophages (Fig. 8C). These results suggested that autophagy was turned on in macrophages but not in epithelial cells following C. trachomatis infection through down-regulation of active mTOR.

Figure 8. Interaction between autophagosomes and lysosomes with C. trachomatis EBs in RAW macrophages.

(A) TEM images of EB (asterisks) inside an autophagosome (left panel) or a lysosome/autolysosome (right panel) in RAW macrophages. Original scale bars = 100 nm. (B) The numbers of live or HK EBs in autophagosomes or lysosomes at 6 and 9 hpi were quantified using TEM images. (C) Western blot of HeLa and RAW cell lysates infected with C. trachomatis over a 9-h period showed that phospho-S2448 mTOR levels decreased in RAW but not in HeLa cells. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Three independent experiments were carried out, and representative blots are shown.

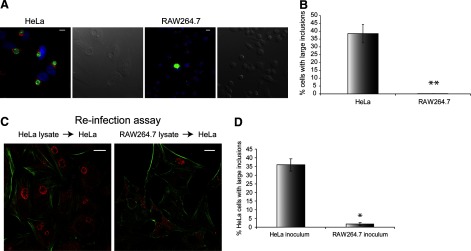

The replication rate of C. trachomatis in macrophages is slower than that in epithelial cells

As we observed a very frequent association between Chlamydia and lysosomes and autophagosomes, we examined whether this cellular trafficking affected C. trachomatis replication in macrophages. Throughout our analyses, we consistently observed reduced formation of large inclusions in infected RAW cells, compared with HeLa cells (Fig. 9A and B). To further validate this notion, the number of infectious C. trachomatis progenies in RAW macrophages was compared with that in HeLa cells using a reinfection assay. The number of large inclusions generated after reinfection of new HeLa cells was used as a measure of C. trachomatis growth. The lysate from infected HeLa cells led to the formation of large inclusions in ∼35% of the new HeLa culture, whereas only 2–3% of the new HeLa culture formed large inclusions when infected with the RAW lysate (Fig. 9B and C). Together, these results indicated that macrophages could significantly restrict C. trachomatis replication by targeting these bacteria to degradative organelles.

Figure 9. Development of C. trachomatis inclusions are suppressed significantly in RAW macrophages compared with HeLa cells.

(A) Large inclusions often formed in Chlamydia-infected HeLa but not RAW cells at 24 hpi. Cells were immunostained for Golgi (red), EB (green), and nuclei (blue) and imaged using an epifluorescent microscope. (B) The percentages of HeLa and RAW cells with large inclusions at 24 hpi were quantified. (C) Confocal images of HeLa cells infected with C. trachomatis-infected HeLa or RAW lysates. Cells were immunostained for actin (green) and inclusions (red). (D) Quantification of the reinfection assay demonstrated that HeLa lysates contained much more infectious Chlamydia than RAW lysates at 30 hpi. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Error bars represent sem from three independent experiments (n>100/experiment). Original scale bars = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Extensive research has demonstrated that C. trachomatis manipulates epithelial cells to evade the endocytic pathway, which may promote its replication [4, 15]. We focused our study on the less-known trafficking pathway of C. trachomatis in macrophages. Our results demonstrated that Chlamydia replication was hindered significantly in macrophages compared with epithelial cells. We observed very similar rates of internalization of Chlamydia in both cell types, and the internalization rate is independent of the activation state of the macrophages. Moreover, based on comparable internalization kinetics and phospho-TARP levels, it is likely that C. trachomatis could induce its own uptake into macrophages similar to epithelial cells [45, 46].

Once inside the macrophage, C. trachomatis inclusions showed several notable differences from inclusions in epithelial cells. Unlike the striking redistribution of Golgi stacks in HeLa cells [8, 9], this organelle remained intact after C. trachomatis infection in murine and primary human macrophages. Recent studies have demonstrated that C. trachomatis can secrete CPAF and cause the cleavage of Golgin84 to disrupt Golgi stacks in epithelial cells [10, 11]. This Golgi disruption does not occur to a significant degree in macrophages, as there was no detectable level of Golgin84 cleavage products in these cells. Moreover, the efficiency of C. trachomatis inclusions to capture Golgi-derived lipids, as measured by fluorescent ceramide trafficking, is reduced significantly in macrophages, consistent with the notion that Golgi fragmentation is important for efficient interception of lipids from the Golgi [10, 11].

We used the readily transfectable RAW cells to characterize the trafficking of C. trachomatis in macrophages. Whereas C. trachomatis inclusions in epithelial cells are devoid of known endocytic markers, such as EEA1, Rab7, and LAMP1 [4, 5, 15], we observed >98% association between lysosome markers LAMP1 and C. trachomatis EBs within the first 30 min of infection using spinning disk confocal live cell imaging. Close to 97% of fluorescent EBs associated with acidic compartments labeled by LysoSensor Green. Moreover, bafilomycin treatment increased the formation of large inclusions in RAW cells by more than fivefold, suggesting the acidification of lysosomes is important for limiting the C. trachomatis growth. These results are consistent with the notion that RAW cells can rapidly detect and target invading C. trachomatis EBs to lysosomes, which would suppress the bacterial growth through acidification. As >95% of C. trachomatis EBs were trafficked into the lysosomes where their development was compromised severely, they likely do not survive long enough to activate bacterial effectors required for Golgin84 cleavage. Thus, lysosome targeting and bacterial destruction appear to block the pathway of Golgi targeting and ceramide interception in macrophages.

We also observed association of C. trachomatis EBs with Rab7 but not with Rab5 in macrophages using live cell imaging. This is very unique compared with the canonical trafficking of internalized particles in macrophages [47]. Despite using very rapid spinning disk confocal imaging, we still could not capture significant association between Rab5-GFP and C. trachomatis EBs. Whereas it is possible that Rab5 associates with C. trachomatis so transiently or at such low levels that our live cell imaging was not sensitive enough to capture this event, it is also possible that Rab5 is not involved in the trafficking of C. trachomatis EBs in macrophages. Unlike our Rab7-DN-GFP findings, DN Rab5 failed to enhance the growth rate and formation of large inclusions in macrophages. Moreover, >99% of fluorescent EBs were still trafficked into Rab7-GFP compartments, even after the expression of Rab5-DN-mCherry. These results suggest that Rab5 is not essential in the trafficking of C. trachomatis to lysosomes in macrophages. HK C. trachomatis EBs also showed negligible Rab5 recruitment and strong Rab7/lysosome recruitment, although at lower levels compared with live bacteria, which is possibly attributed to a slower internalization rate.

As autophagy has been demonstrated to play an important role in controlling microbial infection [37, 48], we next examined whether C. trachomatis EBs associated with autophagic structures at later stages of infection. With the use of live cell imaging, we observed a significant increase in LC3-GFP association for fluorescently labeled EBs at 8 hpi. Moreover, this association was enhanced dramatically when acidification of lysosomes was inhibited with bafilomycin to protect the GFP signal. Consistent with the fluorescent imaging results, we observed that ∼30% of C. trachomatis EBs resided within double-membrane-bound, multivesicular body-containing compartments characteristic of autophagosomes using TEM at 6 and 9 hpi [43]. Accordingly, we observed a decreased activation level of the repressor of autophagy, mTOR, at these later stages of C. trachomatis infection. Together, these results indicate that macrophages not only rapidly target invading C. trachomatis EBs into lysosomes during early infection but also elevate their autophagy levels at later stages of the infection through down-regulation of mTOR activity. More than 95% of EBs were targeted into lysosomes and almost 50% of C. trachomatis associated with LC3-GFP after 3 h of bafilomycin treatment at 8 hpi. These numbers suggest that a significant portion of EBs trafficked into lysosomes is targeted again by autophagy. As C. trachomatis EBs were already within acidic lysosomes in the 1st h of infection, it is unlikely that a later, second round of lysosomal targeting through autophagy could further enhance bacterial degradation. As the level of the autophagy repressor, phospho-mTOR S2448, only decreased 6 hpi, it is very likely that instead of being involved in the early trafficking of C. trachomatis EBs, autophagy plays a role in the subsequent processing of this bacterium. Numerous studies have demonstrated that autophagy can enhance pathogen antigen presentation by macrophages (reviewed in ref. [49]). A recent study showed that the efficacy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine is enhanced by elevated autophagy levels [50]; therefore, it will be interesting to explore whether autophagy can similarly improve vaccines against C. trachomatis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project is funded by a MOP-68992 grant from the CIHR to R.E.H. M.R.T. was supported by a National Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant. R.E.H. is a recipient of a CIHR New Investigator Award and an Ontario Early Researcher Award. We thank Dr. Sergio Grinstein (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada) for the Rab5-GFP, Rab5 S34N-GFP, Rab7-GFP, and Rab7 T22N-GFP constructs and Dr. Nicola Jones (The Hospital for Sick Children) for the LC3-GFP construct. We thank Dr. David Hackstadt (U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Hamilton, MT, USA) for the generous gifts of Chlamydia EB and TARP antibodies. We thank Bob Temkin for his generous help with TEM.

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

- CIHR

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CPAF

- chlamydial protease-like activity factor

- DN

- dominant-negative

- EB

- elementary body

- EEA1

- early endosome antigen 1

- HK

- heat-killed

- hpi

- hours postinfection

- Inc

- inclusion

- LAMP1

- lysosome-associated membrane protein 1

- LC3

- microtubule-associated protein light chain 3

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- RAW macrophage

- RAW264.7 macrophage

- RB

- reticulate body

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- SPG

- sucrose-phosphate-glutamate

- TARP

- translocated actin recruiting phosphoprotein

AUTHORSHIP

H.S.S., E.W.Y.E., S.J., A.T-W.S., and P.P. carried out the experiments in this study. E.W.Y.E. and H.S.S. wrote the manuscript. E.G., M.R.T., R.D.I., and R.E.H. assisted in experimental design and editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Valdivia R. H. (2008) Chlamydia effector proteins and new insights into chlamydial cellular microbiology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beatty W. L., Morrison R. P., Byrne G. I. (1994) Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol. Rev. 58, 686–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hatch T. P., Allan I., Pearce J. H. (1984) Structural and polypeptide differences between envelopes of infective and reproductive life cycle forms of Chlamydia spp. J. Bacteriol. 157, 13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heinzen R. A., Scidmore M. A., Rockey D. D., Hackstadt T. (1996) Differential interaction with endocytic and exocytic pathways distinguish parasitophorous vacuoles of Coxiella burnetii and Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 64, 796–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dautry-Varsat A., Balana M. E., Wyplosz B. (2004) Chlamydia-host cell interactions: recent advances on bacterial entry and intracellular development. Traffic 5, 561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scidmore M. A., Fischer E. R., Hackstadt T. (2003) Restricted fusion of Chlamydia trachomatis vesicles with endocytic compartments during the initial stages of infection. Infect. Immun. 71, 973–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grieshaber S. S., Grieshaber N. A., Hackstadt T. (2003) Chlamydia trachomatis uses host cell dynein to traffic to the microtubule-organizing center in a p50 dynamitin-independent process. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3793–3802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hackstadt T., Rockey D. D., Heinzen R. A., Scidmore M. A. (1996) Chlamydia trachomatis interrupts an exocytic pathway to acquire endogenously synthesized sphingomyelin in transit from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 15, 964–977 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carabeo R. A., Mead D. J., Hackstadt T. (2003) Golgi-dependent transport of cholesterol to the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 6771–6776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heuer D., Lipinski A. R., Machuy N., Karlas A., Wehrens A., Siedler F., Brinkmann V., Meyer T. F. (2009) Chlamydia causes fragmentation of the Golgi compartment to ensure reproduction. Nature 457, 731–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Christian J. G., Heymann J., Paschen S. A., Vier J., Schauenburg L., Rupp J., Meyer T. F., Hacker G., Heuer D. (2011) Targeting of a chlamydial protease impedes intracellular bacterial growth. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rockey D. D., Scidmore M. A., Bannantine J. P., Brown W. J. (2002) Proteins in the chlamydial inclusion membrane. Microbes Infect. 4, 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Capmany A., Damiani M. T. (2010) Chlamydia trachomatis intercepts Golgi-derived sphingolipids through a Rab14-mediated transport required for bacterial development and replication. PLoS One 5, e14084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rejman Lipinski A., Heymann J., Meissner C., Karlas A., Brinkmann V., Meyer T. F., Heuer D. (2009) Rab6 and Rab11 regulate Chlamydia trachomatis development and Golgin-84-dependent Golgi fragmentation. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rzomp K. A., Scholtes L. D., Briggs B. J., Whittaker G. R., Scidmore M. A. (2003) Rab GTPases are recruited to chlamydial inclusions in both a species-dependent and species-independent manner. Infect. Immun. 71, 5855–5870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greub G., Mege J. L., Gorvel J. P., Raoult D., Meresse S. (2005) Intracellular trafficking of Parachlamydia acanthamoebae. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Patel P. C., Harrison R. E. (2008) Membrane ruffles capture C3bi-opsonized particles in activated macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 4628–4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caldwell H. D., Kromhout J., Schachter J. (1981) Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 31, 1161–1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mager D. L. (2006) Bacteria and cancer: cause, coincidence or cure? A review. J. Transl. Med. 4, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wirth J. J., Kierszenbaum F., Sonnenfeld G., Zlotnik A. (1985) Enhancing effects of γ interferon on phagocytic cell association with and killing of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect. Immun. 49, 61–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goerdt S., Politz O., Schledzewski K., Birk R., Gratchev A., Guillot P., Hakiy N., Klemke C. D., Dippel E., Kodelja V., Orfanos C. E. (1999) Alternative versus classical activation of macrophages. Pathobiology 67, 222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spinelle-Jaegle S., Devillier P., Doucet S., Millet S., Banissi C., Diu-Hercend A., Ruuth E. (2001) Inflammatory cytokine production in interferon-γ-primed mice, challenged with lipopolysaccharide. Inhibition by SK&F 86002 and interleukin-1 β-converting enzyme inhibitor. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 12, 280–289 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nacife V. P., Soeiro Mde N., Gomes R. N., D'Avila H., Castro-Faria Neto H. C., Meirelles Mde N. (2004) Morphological and biochemical characterization of macrophages activated by carrageenan and lipopolysaccharide in vivo. Cell Struct. Funct. 29, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gordon M. A., Jack D. L., Dockrell D. H., Lee M. E., Read R. C. (2005) γ Interferon enhances internalization and early nonoxidative killing of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by human macrophages and modifies cytokine responses. Infect. Immun. 73, 3445–3452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schroder K., Hertzog P. J., Ravasi T., Hume D. A. (2004) Interferon-γ: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75, 163–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clifton D. R., Fields K. A., Grieshaber S. S., Dooley C. A., Fischer E. R., Mead D. J., Carabeo R. A., Hackstadt T. (2004) A chlamydial type III translocated protein is tyrosine-phosphorylated at the site of entry and associated with recruitment of actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10166–10171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jewett T. J., Dooley C. A., Mead D. J., Hackstadt T. (2008) Chlamydia trachomatis tarp is phosphorylated by src family tyrosine kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 371, 339–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clifton D. R., Dooley C. A., Grieshaber S. S., Carabeo R. A., Fields K. A., Hackstadt T. (2005) Tyrosine phosphorylation of the chlamydial effector protein Tarp is species specific and not required for recruitment of actin. Infect. Immun. 73, 3860–3868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mehlitz A., Banhart S., Hess S., Selbach M., Meyer T. F. (2008) Complex kinase requirements for Chlamydia trachomatis Tarp phosphorylation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289, 233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chavrier P., Parton R. G., Hauri H. P., Simons K., Zerial M. (1990) Localization of low molecular weight GTP binding proteins to exocytic and endocytic compartments. Cell 62, 317–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bucci C., Parton R. G., Mather I. H., Stunnenberg H., Simons K., Hoflack B., Zerial M. (1992) The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell 70, 715–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng Y., Press B., Wandinger-Ness A. (1995) Rab 7: an important regulator of late endocytic membrane traffic. J. Cell Biol. 131, 1435–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roberts R. L., Barbieri M. A., Ullrich J., Stahl P. D. (2000) Dynamics of rab5 activation in endocytosis and phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68, 627–632 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vieira O. V., Bucci C., Harrison R. E., Trimble W. S., Lanzetti L., Gruenberg J., Schreiber A. D., Stahl P. D., Grinstein S. (2003) Modulation of Rab5 and Rab7 recruitment to phagosomes by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2501–2514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarantis H., Balkin D. M., De Camilli P., Isberg R. R., Brumell J. H., Grinstein S. (2012) Yersinia entry into host cells requires Rab5-dependent dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P(2) and membrane scission. Cell Host Microbe 11, 117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harrison R. E., Bucci C., Vieira O. V., Schroer T. A., Grinstein S. (2003) Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6494–6506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang J., Brumell J. H. (2009) Autophagy in immunity against intracellular bacteria. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 335, 189–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moreau K., Luo S., Rubinsztein D. C. (2010) Cytoprotective roles for autophagy. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 206–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tanida I., Ueno T., Kominami E. (2008) LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol. Biol. 445, 77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barth S., Glick D., Macleod K. F. (2010) Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J. Pathol. 221, 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Klionsky D., Abeliovich J., Agostinis H., Agrawal P., Aliev D. K., Askew G., Baba D. S., Baehrecke M., Bahr E. H., Ballabio B. A.., et al. (2008) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 4, 151–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Manor E., Sarov I. (1986) Fate of Chlamydia trachomatis in human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect. Immun. 54, 90–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yla-Anttila P., Vihinen H., Jokitalo E., Eskelinen E. L. (2009) Monitoring autophagy by electron microscopy in mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 452, 143–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tanida I., Minematsu-Ikeguchi N., Ueno T., Kominami E. (2005) Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy 1, 84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boleti H., Benmerah A., Ojcius D. M., Cerf-Bensussan N., Dautry-Varsat A. (1999) Chlamydia infection of epithelial cells expressing dynamin and Eps15 mutants: clathrin-independent entry into cells and dynamin-dependent productive growth. J. Cell Sci. 112, 1487–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hybiske K., Stephens R. S. (2007) Mechanisms of Chlamydia trachomatis entry into nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 75, 3925–3934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Flannagan R. S., Jaumouille V., Grinstein S. (2012) The cell biology of phagocytosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 7, 61–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Levine B., Mizushima N., Virgin H. W. (2011) Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469, 323–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crotzer V. L., Blum J. S. (2009) Autophagy and its role in MHC-mediated antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 182, 3335–3341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jagannath C., Lindsey D. R., Dhandayuthapani S., Xu Y., Hunter R. L., Jr., Eissa N. T. (2009) Autophagy enhances the efficacy of BCG vaccine by increasing peptide presentation in mouse dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 15, 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.