Significance

Sensory inputs are known to control aging. The underlying circuitry through which these cues are integrated into regulatory physiological outputs, however, remains largely unknown. Here, we use the taste sensory system of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to detail one such circuit. Specifically, we find that water-sensing taste signals alter nutrient homeostasis and regulate a glucagon-like signaling pathway to govern production of internal water production. This metabolic alteration likely serves as a response to water sensory information. This control of metabolic state, in turn, determines the organism’s long-term health and lifespan. Our studies, then, provide a framework for understanding sensory control of aging as well as several targets to potentially maximize organismal health.

Keywords: taste, adipokinetic hormone signaling

Abstract

Sensory perception modulates lifespan across taxa, presumably due to alterations in physiological homeostasis after central nervous system integration. The coordinating circuitry of this control, however, remains unknown. Here, we used the Drosophila melanogaster gustatory system to dissect one component of sensory regulation of aging. We found that loss of the critical water sensor, pickpocket 28 (ppk28), altered metabolic homeostasis to promote internal lipid and water stores and extended healthy lifespan. Additionally, loss of ppk28 increased neuronal glucagon-like adipokinetic hormone (AKH) signaling, and the AKH receptor was necessary for ppk28 mutant effects. Furthermore, activation of AKH-producing cells alone was sufficient to enhance longevity, suggesting that a perceived lack of water availability triggers a metabolic shift that promotes the production of metabolic water and increases lifespan via AKH signaling. This work provides an example of how discrete gustatory signals recruit nutrient-dependent endocrine systems to coordinate metabolic homeostasis, thereby influencing long-term health and aging.

Sensory signaling systems are potent modulators of organismal metabolism and lifespan (1–6) but the mechanisms by which sensory inputs are transduced into relevant physiological outputs remain poorly understood. For even the simplest organisms, an extensive array of sensory stimuli—including chemical, mechanical, thermal, and visual cues—must be properly transduced and integrated to ensure a reliable response to environmental quality. In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, sensory neurons alone may accomplish these tasks. They express multiple sensory receptors, which provide simple integrative capabilities to the cell, and they secrete neuropeptides, which can direct cell-nonautonomous responses in peripheral tissues (7). The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, however, is similar to mammals in that sensory neurons are often highly specialized, and elaborate mechanisms of sensory integration and interpretation are performed by specialized processing centers in the central brain (8). Once decoded, sensory signals are presumably relayed to neuroendocrine centers to stimulate appropriate actions in peripheral tissues. Whereas the release of endocrine molecules, including insulin-like peptides, via central nervous system (CNS) control has emerged as a critical regulator of aging across model organisms, the extent to which sensory signals impact such systems, and the underlying neurocircuitry involved, are unknown (9–11).

The Drosophila system is a powerful tool for elucidating evolutionarily conserved aspects of neural circuitry that link sensory information to a variety of behavioral and metabolic responses. Although comprised of only ∼100,000 neurons, the fly brain is sufficiently complex to share many aspects of structure and function with humans and mice. This, along with the ability to manipulate neuronal activity in a temporally and spatially controlled manner, has made it an effective tool for elucidating neural mechanisms of complex behaviors that include, among others, feeding (12, 13) and mating (14). We thus inferred that this system would have high utility for mapping the circuitry underlying changes in aging due to sensory input.

To identify and dissect sensory networks that regulate aging in the fly, we focused on taste perception. We reasoned that gustatory chemosensory signals would be particularly relevant given their role in assessing dietary landscape, the composition of which has been found to have profound effects on organismal lifespan (15, 16). Additionally, the similarity between taste processing in Drosophila and mammalian systems suggested that our work could be applied broadly. In mammals, for example, taste receptors (G protein-coupled receptors or ion channels) are segregated by modality in specialized epithelial taste receptor cells, and their activation leads to transduction of taste cue to the primary gustatory cortex of the CNS (8). Comparably, D. melanogaster also maintains specialized and segregated taste cells, expressing either G protein-coupled gustatory receptors (GRs) or members of the pickpocket (ppk) family of ion channels (17–19). These bona fide neurons directly map to the gustatory center of the Drosophila CNS, the subesophageal ganglion (8). Little is known in either system, however, about links between the taste processing centers and well-characterized neuroendocrine cells.

As a vital nutrient for all animals, we predicted that water would be an environmental component capable of driving gustatory modulation of physiology and lifespan. The regulation of water intake, for example, is essential for organisms to maintain proper osmotic homeostasis, and whole organ systems are devoted to maintaining its balance. It has long been known that insects harbor specialized sensory neurons that are sensitive to water (20, 21). These are concentrated on the proboscis, the major organ of ingestion of the fly. The proboscis is covered with taste sensilla, with each sensillum harboring up to four GR neurons that each recognize a distinct taste modality (sweet, bitter, pheromone, or water) (17–19). The osmosensitive ion channel ppk28 is expressed in water-sensitive neurons, and it is required for a functional gustatory response to external water (18). Osmosensitive taste receptors have also been identified in the rat (22, 23) and the ability of water to stimulate gustatory nerve fibers, a response that has been termed “water response,” is common in many vertebrates (22). Finally, water availability has been implicated in Drosophila aging (24, 25).

We therefore asked whether sensory perception of water modulates aging in the fly. We first determined the metabolic and longevity consequences of loss of function of the gustatory gene ppk28. We found that loss of this critical water sensor promoted longevity, which was accompanied by increased glucose and lipid stores and by enhanced physical performance throughout life. The receptor for the glucagon-like molecule adipokinetic hormone (AKHR) was required for ppk28-mediated effects, as was the integral insulin-like signaling transcription factor, Drosophila homolog of FoxO transcription factor (dFOXO). Consistent with the genetic data, ppk28 mutant flies exhibited an up-regulation of AKH signaling, which is known to promote lipid mobilization (26) and therefore may serve to increase metabolic water production (27). Indeed, mutant animals were desiccation resistant and retained greater amounts of internal water. Finally, activation of AKH-producing neurons was sufficient to increase lifespan, suggesting that the promotion of longevity in our sensory mutants may result from an alteration of physiologic priorities to emphasize metabolic water production in response to a perceived environmental scarcity. This work, then, provides a framework for understanding how the perception of nutrients, distinct from consumption, is processed in the CNS to direct longevity-regulating physiological consequences. Furthermore, these data reveal the role that water specifically maintains as a physiologically influential dietary component.

Results

Loss of ppk28 Function Increases Drosophila Health and Lifespan.

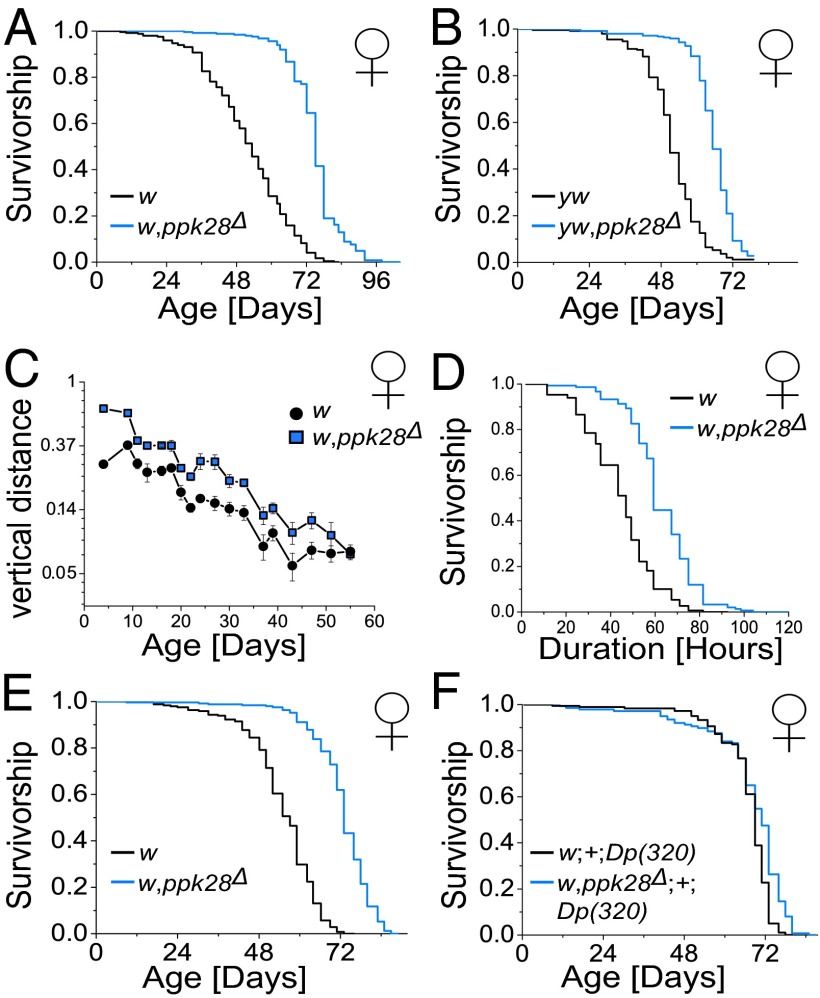

To determine whether water-sensing inputs, requiring ppk28 function, were capable of affecting longevity, we acquired a ppk28-null mutant line (ppk28Δ) containing a 1.769-kb deletion surrounding the ppk28 endogenous locus (18). Flies lacking ppk28 fail to exhibit a functional gustatory response to a water stimulus (18). Deletion mutants were backcrossed to two separate control lines [w1118-VDRC (w) and yw] for six to eight generations with lifespan measured and compared with background controls (Fig. 1 A and B). Indeed, female ppk28-null mutant flies showed a significant increase in mean and maximum lifespan in both genetic backgrounds (a maximum of 43.55% increase in mean lifespan in w and 24.78% in yw; see Table S1 for replicate experiments). Loss of ppk28 also extended male lifespan in both genetic backgrounds, although to a lesser degree (Fig. S1 A and B). Additionally, a second ppk28 mutant allele created via P-element insertion into the third of four exons of the ppk28 gene (ppk28G981) (28) extended female lifespan (a mean lifespan increase of 13.1%) compared with background control (Fig. S1C). To test whether loss of water-sensing gustatory information was also associated with an increase in overall health, we performed a negative geotaxis assay and found that ppk28 mutants showed greater performance than background controls throughout their lifespan (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, ppk28 mutants showed increased resistance to starvation stress (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Loss of ppk28 function increases healthy lifespan in D. melanogaster. (A and B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for female ppk28 deletion mutants in both w1118-VDRC (w) [n = 246 (w); n = 248 (w,ppk28Δ); mean lifespan increase of 20.68 d (43.55%)] (A) and yw [n = 244 (yw); n = 248 (yw,ppk28Δ); mean lifespan increase of 13.48 d (24.78%)] (B) background and their corresponding background controls. (C) Analysis of vertical distance climbed in the longitudinal negative geotaxis assay of ppk28 mutant (w,ppk28Δ) and background control (w) female flies (n = 10 groups of 20 flies per genotype per time point). Page < 1 × 10−15, Pgenotype = 1.13 × 10−10, and Pinteraction = 0.031 for ANCOVA. Error bars indicate ±SEM. (D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for approximately 2-wk old female ppk28 mutant (w,ppk28Δ) and background control (w) female flies [n = 149 (w); n = 150 (w,ppk28Δ)] under starvation conditions. (E and F) Survival curves for female ppk28 deletion mutants (w,ppk28Δ) and background controls (w) [n = 245 (w); n = 247 (w,ppk28Δ); mean lifespan increase of 17.50 d (30.54%)] (E) compared with survival curves representing the addition of a genomic region containing the endogenous ppk28 locus into both ppk28 mutant [w,ppk28Δ;+;Dp(320)] and control [w;+;Dp(320)] backgrounds (n = 180 [w;+;Dp(320)]; n = 137 [w,Δppk28;+;Dp(320)]; mean lifespan increase of 1.14 d [1.65%]) (F) on SY5% (wt/vol) food. Pairwise comparisons between statistically significantly different genotypes in survival analyses yielded P < 1 × 10−6 by log-rank test for all cases.

Gustatory manipulations have the potential to alter food intake, and dietary restriction is sufficient to affect lifespan across model organisms (15). Therefore, to determine whether ppk28-null mutants were long-lived simply because they were eating less than their background controls, we quantified feeding behavior in these flies. Our longevity assays used a sugar–yeast medium containing 10% (wt/vol) of both macronutrients (called “SY10%”), and food intake rates in ppk28 mutant flies were statistically indistinguishable from control animals under these conditions at a young age and significantly increased at an advanced age (Fig. S2A). Furthermore, we found that overall nutrient concentration (ranging from SY5% to SY15%), and therefore the osmolarity of the medium, had no effect on this relationship (Fig. S2B). These data suggest that ppk28 mutant flies are not long-lived due to decreased feeding behavior.

Improvements in lifespan and health measures in our flies were attributable to disruption of the ppk28 locus. Transgenic addition of a small duplication element (Dp) from the first chromosome inserted onto the third chromosome (1;3) containing the endogenous ppk28 locus [Dp(1;3)DC320, “Dp(320)” for brevity] rescued the lifespan extension associated with ppk28 deletion. Whereas transgenic stocks were marginally longer lived than the w1118 stock in general, loss of ppk28 had no effect on lifespan in flies that simultaneously carried a duplication of the region (Fig. 1 E and F). The presence of the duplication also reversed physiological changes associated with ppk28 loss of function (see ppk28-Mediated Signals Regulate Nutrient Homeostasis). Together, these data suggest that integration of ppk28-mediated gustatory signals negatively regulate Drosophila lifespan independently of feeding behavior and that loss of ppk28 function is efficacious for sustained health and longevity.

ppk28-Mediated Signals Regulate Nutrient Homeostasis.

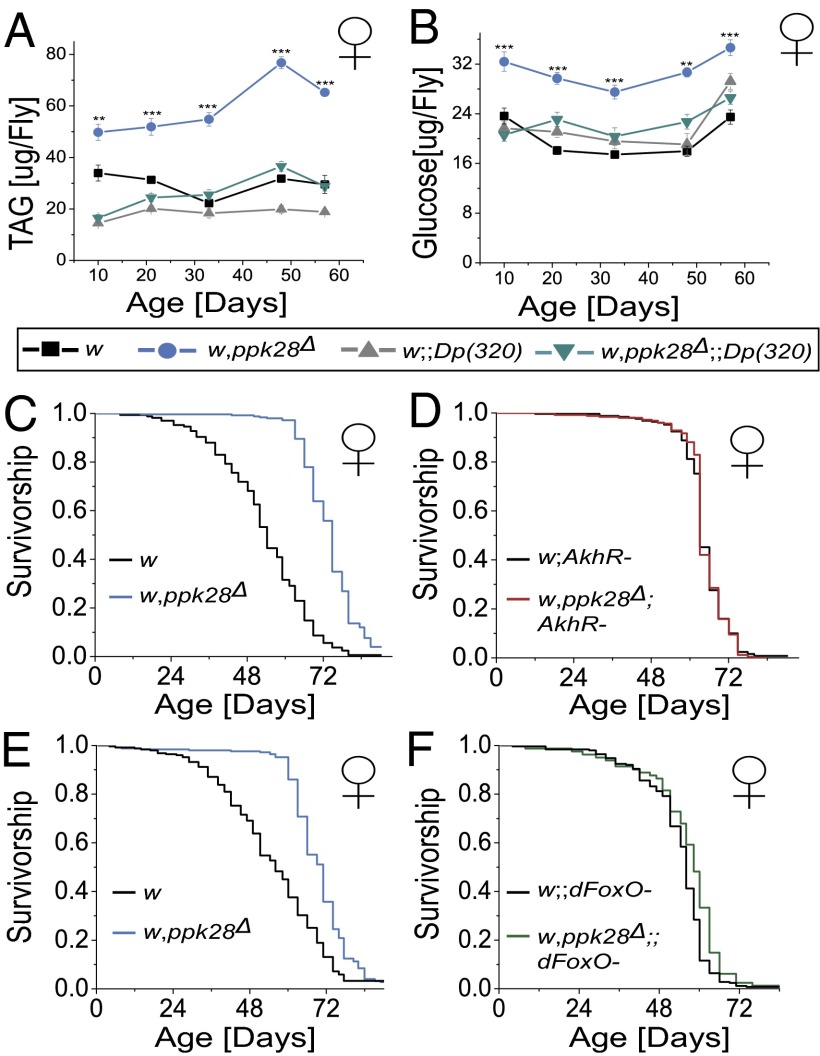

The criticality of water for metabolic processes led us to hypothesize that water gustatory neurons may exert their regulatory effect through control of nutrient metabolism. To establish whether loss of ppk28 input was sufficient to modulate nutrient homeostasis, we assayed whole organism levels of both carbohydrate and lipid in the long-lived ppk28 deletion mutants. Indeed, these flies displayed both increased levels of triacylglyceride (TAG) and glucose compared with background controls, effects that were rescued with reintroduction of ppk28 into the mutant background (Fig. 2 A and B). Notably, we observed that aging had little effect on TAG and glucose levels as differences among genotypes persisted throughout life. Although ppk28 mutants were slightly heavier than background controls (Fig. S3A), normalization by body weight did not affect the relationship between genotypes (Fig. S3 B and C). Furthermore, the difference in mass was not present immediately posteclosion (Fig. S3D). These data suggest that altered nutrient levels in water-sensing mutants were due to a directed switch in physiological state early in adult life rather than a loss of homeostatic control.

Fig. 2.

ppk28 modulates lifespan through nutrient signaling. (A and B) Longitudinal measures of whole-fly TAG (A) and glucose (B) in ppk28 deletion mutant female flies (w,ppk28Δ) and in mutant animals also containing a ppk28 genomic rescue construct [w,ppk28Δ;+;Dp(320)], as well as their appropriate genetic background controls [w and w;+;Dp(320), respectively]. n = 8–12 groups of five flies per genotype per time point. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 for the interaction term of two-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate ±SEM. (C and D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for female ppk28 deletion mutant flies (w,ppk28Δ) and background controls (w) [n = 162 (w); n = 249 (w,ppk28Δ); mean lifespan increase of 20.68 d (36.96%)] (C) and the same backgrounds containing loss of function of AKHR (w;AkhR−) and (w,ppk28Δ;AkhR–) [n = 253 (w;AkhR−); n = 248 (w,ppk28Δ;AkhR−); mean lifespan increase of 0.67 d (0.99%)] (D). (E and F) Survival curves for female ppk28 deletion mutant flies (w,ppk28Δ) and their controls (w) [n = 221 (w); n = 243 (w,ppk28Δ); mean lifespan increase of 14.16 d (24.73%)] (E) and same backgrounds containing deletion of the FoxO transcription factor (w;dFoxO− and w,ppk28Δ;dFoxO−) [n = 248 (w;dFoxO−); n = 80 (w,ppk28Δ;dFoxO−); mean lifespan increase of 2.4 d (4.28%)] (F). Pairwise comparisons between statistically significantly different genotypes yielded P < 1 × 10−6 by log-rank test for all cases.

ppk28-Mediated Lifespan Extension Requires Components of Nutrient Homeostasis Pathways.

Having observed significant differences in nutrient levels, we next hypothesized that signaling pathways responsible for the coordination of metabolic homeostasis may be required for ppk28-mediated lifespan extension. In mammals, levels of glucagon and insulin are key to the coordination of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (29). Flies maintain functionally homologous molecules to each of these hormones—the glucagon-like adipokinetic hormone (dAkh) (30) as well as eight insulin-like peptides (dILPs 1–8) (31–33). To test the requirement of each signaling network in ppk28-mediated lifespan extension, we undertook an epistasis approach in which double mutant flies, functionally null for ppk28 as well as a critical component of either pathway, were generated and assessed for lifespan. We found that the extended lifespan of ppk28-null flies (Fig. 2C) was abrogated by the introduction of a null mutation for AkhR (34) into the control and ppk28 mutant backgrounds (Fig. 2D). Likewise, a similar strategy using a null mutation for dFoxO (35), an integral component in ILP signaling, also abolished the increased longevity found in ppk28 mutant flies (Fig. 2 E and F). Notably, this strategy does not allow genetically controlled comparisons between AkhR and dFoxO mutants with w controls, and, as such, interpretation of lifespan effects of these single mutants is not within the scope of this study. As dFoxO is normally active under levels of low ILP signaling, these data support a model by which lifespan extension may be due, at least in part, to reduced levels of insulin signaling. Consistent with this interpretation, we found that transcript levels of dILP2 were decreased in ppk28 mutants (Fig. S4A). Details of the downstream mechanism through which dFoxO acts, however, remain unclear because whole-organism transcript levels of dFoxO targets were variable (Fig. S4B).

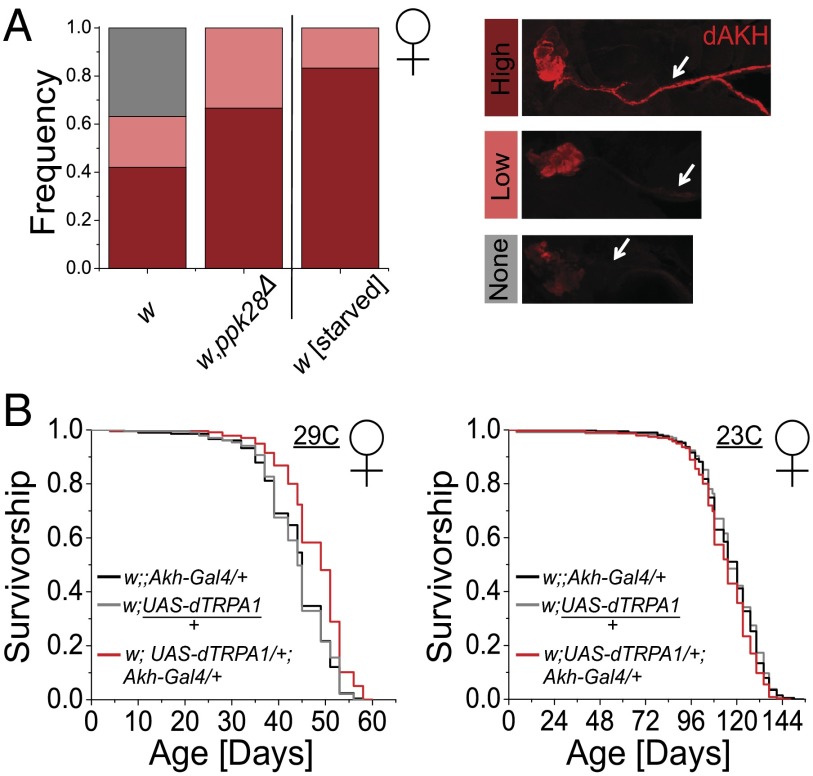

ppk28 Signals Control Release of AKH from the Corpora Cardiaca.

The requirement of AKHR was a surprise as its cognate hormone has been little studied in relation to aging. One prediction from the genetic data is that release of AKH neuropeptide from its site of synthesis would be increased in ppk28 mutant flies. AKH is produced in a small subset of neurons called “corpora cardiaca” (CC) (26). Although Akh mRNA levels were not significantly different between ppk28 mutant and control flies (Fig. S4C), previous work in both the locust (Locusta migratoria) and Drosophila suggests that Akh gene transcription is uncoupled from neuropeptide release and that the neuropeptide may be discharged in a controlled fashion from a pool of continuously synthesized protein (36, 37). To determine whether loss of ppk28 affected AKH release or sequestration, we directly imaged neuropeptide localization in dissected CC from adult flies stained with a dAKH-specific antibody (26). As a positive control indicative of active AKH signaling, we used starved control flies. AKH pathway activity is inversely correlated with starvation resistance (26), and starvation should thus stimulate AKH release. We found that ppk28 mutants showed increased neuropeptide staining, compared with background controls, specifically in the axonal projections from which AKH is released to target areas. A complete lack of staining in these projections was never observed in ppk28 mutant animals but was frequently observed in control animals (Fig. 3A and Fig. S5). The staining pattern of ppk28 mutants closely resembled that of starved flies, arguing that loss of ppk28 function activates AKH signaling.

Fig. 3.

AKH signaling mediates ppk28 effects on lifespan and physiology. (A) Quantification of AKH levels in axonal projections of adult CC. Preparations from fully fed female ppk28 deletion mutant flies (w,ppk28Δ) as well as fed and starved control animals (w) were stained with α-dAKH and categorized as having high, low, or no observable AKH. A representative image from each category is shown for reference [n = 19 (w); n = 15 (w,ppk28Δ); n = 6 (w,starved)]. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for female flies with activated Akh-ergic neurons at both an activating (29 °C) and control nonactivating (23 °C) temperature (neuronal activation: w;UAS-dTRPA1/+;Akh-Gal4/+; Gal4 construct control: w;;Akh-Gal4/+; UAS construct control: w;UAS-dTRPA1/+) on SY5% food [23 °C: n = 202 (w;;Akh-Gal4/+); n = 235 (w;UAS-dTRPA1/+); n = 237 (w;UAS-dTRPA1/+;Akh-Gal4/+); mean lifespan decrease of 3 d (2.50%) and 3.19 d (3.65%) compared with Gal4 and UAS construct controls, respectively; 29 °C: n = 207 (w;;Akh-Gal4/+); n = 237 (w;UAS-dTRPA1/+); n = 235 (w;UAS-dTRPA1/+;Akh-Gal4/+); mean lifespan extension of 3.80 d (8.21%) and 3.74 d (8.07%) compared with Gal4 and UAS construct controls, respectively]. Pairwise comparisons between statistically significantly different genotypes yielded P < 1 × 10−6 by log-rank test for all cases.

Activation of AKH-Producing Cells Extends Lifespan in Absence of Sensory Manipulation.

Our results indicated that an increase in AKH signaling was induced in water-sensing mutants and was essential for lifespan extension. These data are indicative of AKH as a key effector of water taste sensation and as a cause of ppk28 lifespan extension. If so, then increasing activity of this pathway, in the absence of sensory manipulation, should similarly increase lifespan. We therefore tested this hypothesis by conditionally expressing the activating cation channel dTRPA1 (38) in Akh-ergic neurons and studying the effects of targeted neuronal activation on lifespan. Indeed, we found that transgenic flies (Akh-Gal4;UAS-dTRPA1) were significantly long-lived compared with genetic control animals at a temperature in which dTRPA1 is activated (29 °C) but not at a control temperature (23 °C) in which it is not (Fig. 3B). Depleted TAG levels, which are characteristic of enhanced neuronal AKH secretion, persisted for at least 26 d in flies with activated dTRPA1, suggesting that this genetic strategy was effective in securing chronic pathway stimulation (Fig. S6A). Furthermore, this manipulation increased staining in CC cell axons, consistent with findings in long-lived ppk28 mutants (Fig. S6B). Importantly, this lifespan extension could not be attributed to a reduction in food intake (Fig. S6C). The overexpression of Akh in Akh-ergic neurons (Akh-Gal4;UAS-Akh) had no effect on lifespan (Fig. S6D). This is not unexpected because of the documented uncoupling between Akh mRNA synthesis and secretion of AKH protein in insects where physiological phenotypes associated with activation of AKH signaling, including an increase in larval hemolymph trehalose, are not recapitulated by modulation of gene overexpression (26). Together, these data suggest that neuronal modulation of Akh-expressing cells is required to promote physiological changes that are advantageous for maximizing health and longevity.

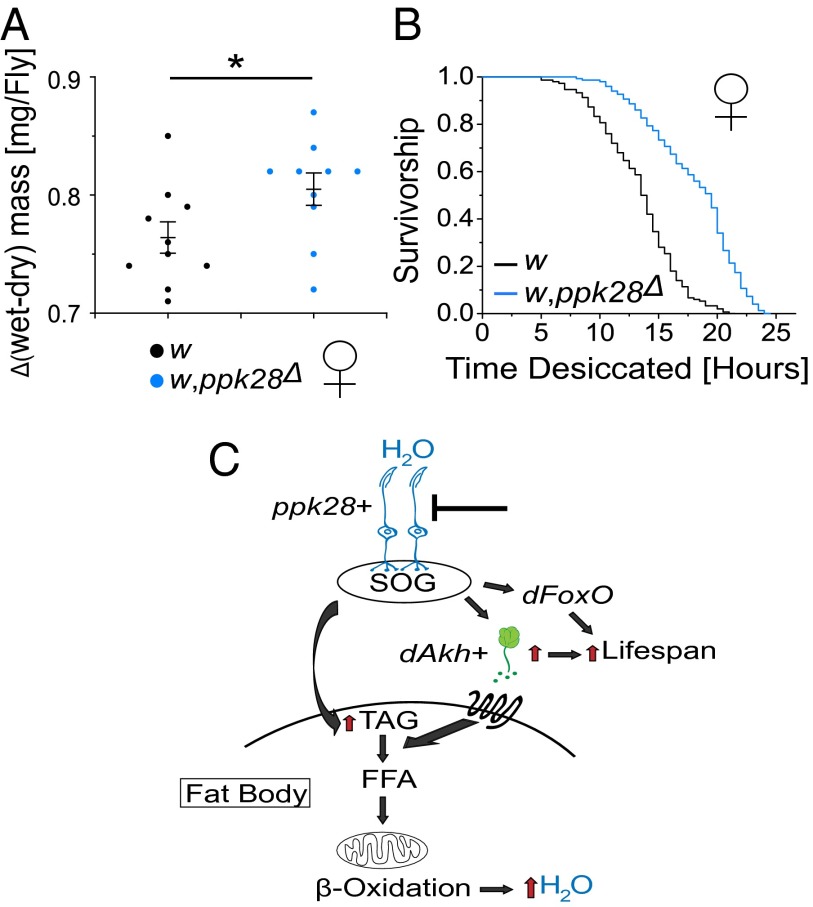

Loss of External Water Gustatory Information Induces Promotion of Internal Water Stores.

The physiologic effects of ppk28 loss of function were reminiscent of adaptations used by a number of desert species that have limited access to fresh water, which use TAG lipolysis and oxidation of free fatty acids as primary sources of metabolic water production (39, 40). We considered that ppk28 mutants, although not physically starved for water, might nevertheless induce similar physiological strategies due to its perceived scarcity. In this model, mutant flies should maintain higher levels of internal water, which in Drosophila can be measured by the subtraction of mass postdesiccation (“dry mass”) from its initial mass (“wet mass”) (41). Indeed, ppk28 mutant flies showed an increased change in mass after desiccation than background controls (Fig. 4A). Although ppk28 mutants maintained a modest, yet significant, increase in wet mass (Fig. S3A), this is almost certainly due to augmented stores of water, as well as TAG and glucose levels (Fig. 2 A and B), rather than an increase in gross size. Indeed, whole-organism protein levels were not significantly different between ppk28 mutants and their background controls (Fig. S7). Furthermore, insects with higher internal water content have been found to be desiccation resistant (42), and we found that ppk28 mutants exhibited significantly increased survivorship under desiccating conditions (Fig. 4B). Consistent with a model by which internal water stores are increased through the action of the AKH-signaling pathway, we found that constitutive activation of AKH-expressing cells also increased the difference between wet and dry mass (Fig. S8). Together, these results suggest that loss of ppk28 function may drive the production of metabolic water through a glucagon-like AKH-dependent mobilization of lipid stores as a compensatory response to the absence of sensory information pertaining to accessible water.

Fig. 4.

Perceived scarcity of external water promotes longevity through metabolic water production. (A) Difference in wet and dry mass for approximately 2-wk-old ppk28 deletion mutant background control (w) and ppk28 deletion mutant (w,ppk28Δ) female flies (n = 10 groups of 10 flies per genotype). *P < 0.05 two-sided Student’s t test. Error bars indicate ±SEM. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for ppk28 deletion mutant background control (w) and ppk28 deletion mutant (w,ppk28Δ) female flies under desiccating conditions (n = 100 flies for both genotypes). Pairwise comparisons between genotypes yielded P < 1 × 10−6 by log-rank test. (C) Model for control of metabolic homeostasis and lifespan by ppk28-mediated gustatory inputs. FFA, free fatty acid; SOG, subesophageal ganglion.

Discussion

Organisms are regularly subjected to diverse sensory stimuli, which provide vital information about the surrounding environment. Establishing how individuals coordinate appropriate physiological responses to such cues is critical for understanding how a lifetime of perceptive experiences may affect overall health. Previous work has provided compelling evidence that nutrient-sensing signaling pathways are key regulators of longevity (10, 43). Additionally, there is a conserved role for the function of chemosensory systems in control of aging (1, 5, 6, 44, 45), including a study in PNAS showing that subsets of gustatory inputs were capable of modulating Drosophila lifespan in a bidirectional manner (6). One logical prediction followed that, in response to transduction and integration of a taste signal, an organism reprograms its metabolic state through modulation of nutrient homeostatic pathways, ultimately altering lifespan. Which specific inputs—and the associated physiological states that result from their manipulation—are capable of altering longevity, however, remained largely untested.

Here, we exploited a specific gustatory signal—emanating from water-sensing taste neurons—as a model by which to understand sensory modulation of aging. As water is an essential component of an organism’s diet and its recognition and ingestion are critical to an organism’s health, we reasoned that modulation of this sensory cue alone may have significant physiological consequences. Indeed, we discovered that loss of function of the ion channel required for water taste perception—ppk28—extended lifespan and augmented health-related parameters (e.g., stress resistance and climbing ability). Furthermore, mutation of ppk28 resulted in alteration of metabolic homeostasis through an increase in lipid stores and a subsequent activation of glucagon-like AKH signaling. Several observations suggested that this physiological switch increased production of metabolic water, resembling a strategy used by species with a severe or complete lack of access to environmental water. Compatible with this model, we find that activation of Akh-ergic neurons is sufficient to increase lifespan, suggesting that signals leading to such activation are also efficacious for increasing health and longevity (Fig. 4C).

Although often overlooked as a principal dietary component in favor of carbohydrate, protein, or lipid, water is just as crucial to an organism’s ability to maintain metabolic homeostasis and just as quintessential for its survival. Indeed, diverse organisms, including flies and mammals, commit a similar amount of sensory resources to the perception of water (18, 46). Our studies suggest that information about external water availability transduced through ppk28-sensing neurons is capable of affecting its internal production and that stimulation of this system by water intake may represent an important consideration for determining dietary influence on health status.

Classic dietary restriction (DR) paradigms of carbohydrate and protein robustly increase lifespan across species, and act at least partially through sensory mechanisms independent of caloric intake (4, 44). Although conclusions from previous work over the role of dietary water in mediating the Drosophila DR–lifespan extension axis have been mixed (24, 25), our studies suggest that water restriction, inasmuch as it decreases stimulation of water-sensing neurons, may also be a viable strategy for enhancing physiological state. Given the necessity of water for metabolic reactions and the discomfort of thirst, however, of perhaps more translational relevance is the implication that the glucagon-like AKH-signaling pathway is a potent modulator of health and lifespan. There is some evidence suggesting that this pathway may, in fact, impinge on the control of lifespan via protein restriction as a recent study found that ectopic overexpression of Akh extends lifespan in flies which are fully fed, yet not under yeast restriction (47). Although the ubiquitous nature of this manipulation may confound its physiological relevance, this is indicative that restriction of dietary components may converge on similar regulatory mechanisms. Congruously, levels of plasma glucagon increase under dietary restriction in mice (48). Dietary or pharmacological interventions that stimulate release of glucagon may, therefore, promote a healthier lifespan in mammals, without the necessity of actual restriction of dietary components.

The evidence that ppk28-mediated inputs require the transcription factor dFoxO for their lifespan effects suggests an additional layer of complexity to this control, one potentially including the insulin/ILP-signaling pathway. Indeed, lifespan extension in C. elegans gustatory mutants requires the FoxO homolog daf-16 (1), and work presented in PNAS suggests a similar dFoxO-dependent mechanism in D. melanogaster (6). The relationship between the insulin and glucagon signaling pathways in maintaining metabolic homeostasis has been well studied in mammalian contexts, with high levels of insulin known to inhibit glucagon release (49). Although this association is less well understood in Drosophila, dILP2-producing median neurosecretory cells and AKH-producing cells are in close proximity, with dILP2-ergic axons extending to the CC (50). If a similar cross-talk occurs in flies, activation of AKH release in ppk28 mutants may be, possibly, in part due to down-regulation of ILP signaling, as suggested by decreased dILP2 levels and dFoxO dependence of longevity increase in these flies. As such, lifespan modulation due to interventions reducing insulin/ILP activity may additionally need to be understood in light of their effect on glucagon-like signaling.

The significance of our findings for the enhancement of health and longevity underscore the importance of the further work that remains. For instance, the mechanisms responsible for the initial increase in TAG stores used as substrate for AKH remain unknown. Furthermore, the signal that activates AKH signaling in response to increased TAG levels has also not been determined. Finally, it remains to be discovered how an increase in AKH pathway activity is responsible for increasing health and longevity. Nonetheless, the results described here form the basis for an understanding of the dynamics of lifespan-modulating sensory signals and their means of command.

Materials and Methods

Fly Strains.

For background controls, we used w1118-VDRC (Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center) or yw (Bloomington Stock Center) lines. Transgenic flies included w,ppk28Δ;+;+ (a gift from K. Scott, University of California, Berkeley, CA), w;+;Dp(1;3)DC320 (Bloomington Stock Center), w;UAS-dTRPA1;+ (a gift from P. Garrity, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA), w;AkhR−;+ (a gift from R. Kühnlein, Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, Germany), and w;+;dFoxO(Δ94) (a gift from L. Partridge, University College London, London).

Survival Analyses.

Lifespan analyses were performed using an empirically optimized protocol established by our laboratory and facilitated by the use of an radiofrequency identification-based tracking system and associated statistical software (dLife) developed by our laboratory (51). See SI Materials and Methods for technical details.

For desiccation resistance, approximately 2-wk-old flies were placed in vials containing ∼1 cm drierite (anhydrous calcium sulfate; W. A. Hammond Drierite Company) and allowed to desiccate at room temperature.

For starvation resistance, approximately 2-wk-old flies were placed in vials containing 1% agar and maintained at 25 °C with vials changed daily.

Nutrient Level Assays.

For all nutrient measurements, female flies were frozen at −80 °C and homogenized in groups of five in 200 μL PBS + 0.05% Triton X-100 (IBI Scientific). Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 1 min to settle debris. All reactions were read with Synergy2 plate reader (BioTek). See SI Materials and Methods for technical details.

Negative Geotaxis Assay.

Flies maintained on SY10% food were placed in empty vials and forced to the bottom with four hard taps. Flies were allowed to climb for 2 s and then photographed. Images were analyzed using Climber Software (developed by S.D.P.) to quantify the distance climbed.

Immunohistochemistry.

Adult female flies were reared as described then dissected at approximately 2 wk of age and stained with a dAKH-specific antibody (a gift from J. Park, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN), then visualized on Olympus FluoView 500 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope using 20× magnification. Starved flies were placed on 1% agar vials for 14 h before dissection. See SI Materials and Methods for technical details.

Wet and Dry Mass Calculations.

Groups of 10 female flies were weighed to determine wet mass and then placed overnight at 65 °C and reweighed to determine dry mass.

Statistical Methods.

All survivorship data were compared via log-rank analysis between relevant genotypes. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for the negative geotaxis assay and a two-way ANOVA in analysis of TAG and glucose levels. Two-sided Student’s t tests were performed for wet/dry mass calculations and quantitative PCR results. Sample sizes and replicate numbers are explicitly stated in each figure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank many colleagues for the generous sharing of reagents. We also thank Jason Braco for technical advice on CC dissection, Alyson Sujkowski for instruction on the negative geotaxis assay, and Markus Noll and Damian Brunner for use of laboratory space. Imaging was performed at the University of Michigan Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory. This work was funded by US National Institutes of Health Grants 5-T-32-GM007315 and T-32-AG000114 (to M.J.W.); T-32-AG000114 and F-32-AG042253 (to B.Y.C.); 5-T32-GM007863-32 (to Z.M.H.); R-01-AG030593, R-01-AG043972, and R-01-AG023166 (to S.D.P.); as well as the Novartis Research Foundation (I.O. and J.A.), the Glenn Foundation, the American Federation for Aging Research, and the Ellison Medical Foundation (S.D.P.). Additionally, this work used the Drosophila Aging Core of the Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Biology of Aging funded by the National Institute on Aging (P30-AG-013283).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315461111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alcedo J, Kenyon C. Regulation of C. elegans longevity by specific gustatory and olfactory neurons. Neuron. 2004;41(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00816-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libert S, Pletcher SD. Modulation of longevity by environmental sensing. Cell. 2007;131(7):1231–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shostal OA, Moskalev AA. The genetic mechanisms of the influence of the light regime on the lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Front Genet. 2012;3:325. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith ED, et al. Age- and calorie-independent life span extension from dietary restriction by bacterial deprivation in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apfeld J, Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402(6763):804–809. doi: 10.1038/45544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostojic I, et al. Positive and negative gustatory inputs affect Drosophila lifespan partly in parallel to dFOXO signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8143–8148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315466111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittaker AJ, Sternberg PW. Sensory processing by neural circuits in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14(4):450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarmolinsky DA, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. Common sense about taste: From mammals to insects. Cell. 2009;139(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mattson MP. Brain evolution and lifespan regulation: Conservation of signal transduction pathways that regulate energy metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123(8):947–953. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broughton S, Partridge L. Insulin/IGF-like signalling, the central nervous system and aging. Biochem J. 2009;418(1):1–12. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatar M. The neuroendocrine regulation of Drosophila aging. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39(11-12):1745–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marella S, Mann K, Scott K. Dopaminergic modulation of sucrose acceptance behavior in Drosophila. Neuron. 2012;73(5):941–950. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dus M, Ai M, Suh GS. Taste-independent nutrient selection is mediated by a brain-specific Na+/solute co-transporter in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(5):526–528. doi: 10.1038/nn.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezával C, et al. Neural circuitry underlying Drosophila female postmating behavioral responses. Curr Biol. 2012;22(13):1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328(5976):321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skorupa DA, Dervisefendic A, Zwiener J, Pletcher SD. Dietary composition specifies consumption, obesity, and lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2008;7(4):478–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montell C. A taste of the Drosophila gustatory receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(4):345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron P, Hiroi M, Ngai J, Scott K. The molecular basis for water taste in Drosophila. Nature. 2010;465(7294):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature09011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thistle R, Cameron P, Ghorayshi A, Dennison L, Scott K. Contact chemoreceptors mediate male-male repulsion and male-female attraction during Drosophila courtship. Cell. 2012;149(5):1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans DR, Mellon D., Jr Electrophysiological studies of a water receptor associated with the taste sensilla of the blow-fly. J Gen Physiol. 1962;45:487–500. doi: 10.1085/jgp.45.3.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujishiro N, Kijima H, Morita H. Impulse frequency and action-potential amplitude in labellar chemosensory neurons of Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 1984;30(4):317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson KJ, et al. Expression of aquaporin water channels in rat taste buds. Chem Senses. 2007;32(5):411–421. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindemann B. Taste reception. Physiol Rev. 1996;76(3):718–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ja WW, et al. Water- and nutrient-dependent effects of dietary restriction on Drosophila lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18633–18637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908016106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piper MD, et al. Water-independent effects of dietary restriction in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(14):E54–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914686107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee G, Park JH. Hemolymph sugar homeostasis and starvation-induced hyperactivity affected by genetic manipulations of the adipokinetic hormone-encoding gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004;167(1):311–323. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arrese EL, Soulages JL. Insect fat body: Energy, metabolism, and regulation. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:207–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellen HJ, et al. The BDGP gene disruption project: Single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics. 2004;167(2):761–781. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang G, Zhang BB. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(4):E671–E678. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00492.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bharucha KN, Tarr P, Zipursky SL. A glucagon-like endocrine pathway in Drosophila modulates both lipid and carbohydrate homeostasis. J Exp Biol. 2008;211(Pt 19):3103–3110. doi: 10.1242/jeb.016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brogiolo W, et al. An evolutionarily conserved function of the Drosophila insulin receptor and insulin-like peptides in growth control. Curr Biol. 2001;11(4):213–221. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombani J, Andersen DS, Léopold P. Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science. 2012;336(6081):582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1216689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garelli A, Gontijo AM, Miguela V, Caparros E, Dominguez M. Imaginal discs secrete insulin-like peptide 8 to mediate plasticity of growth and maturation. Science. 2012;336(6081):579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1216735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grönke S, et al. Dual lipolytic control of body fat storage and mobilization in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(6):e137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slack C, Giannakou ME, Foley A, Goss M, Partridge L. dFOXO-independent effects of reduced insulin-like signaling in Drosophila. Aging Cell. 2011;10(5):735–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diederen JH, Oudejans RC, Harthoorn LF, Van der Horst DJ. Cell biology of the adipokinetic hormone-producing neurosecretory cells in the locust corpus cardiacum. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;56(3):227–236. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhea JM, Wegener C, Bender M. The proprotein convertase encoded by amontillado (amon) is required in Drosophila corpora cardiaca endocrine cells producing the glucose regulatory hormone AKH. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(5):e1000967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamada FN, et al. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454(7201):217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frank CL. Diet selection by a heteromyid rodent: Role of net metabolic water production. Ecology. 1988;69(6):1943–1951. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naidu SG. Why does the Namib Desert tenebrionid Onymacris unguicularis (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) fog-bask? Eur J Entomol. 2008;105(5):829–838. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Folk DG, Han C, Bradley TJ. Water acquisition and partitioning in Drosophila melanogaster: Effects of selection for desiccation-resistance. J Exp Biol. 2001;204(Pt 19):3323–3331. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.19.3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gray EM, Bradley TJ. Physiology of desiccation resistance in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(3):553–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapahi P, et al. With TOR, less is more: A key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 2010;11(6):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Libert S, et al. Regulation of Drosophila life span by olfaction and food-derived odors. Science. 2007;315(5815):1133–1137. doi: 10.1126/science.1136610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poon PC, Kuo TH, Linford NJ, Roman G, Pletcher SD. Carbon dioxide sensing modulates lifespan and physiology in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(4):e1000356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilbertson TA. Hypoosmotic stimuli activate a chloride conductance in rat taste cells. Chem Senses. 2002;27(4):383–394. doi: 10.1093/chemse/27.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katewa SD, et al. Intramyocellular fatty-acid metabolism plays a critical role in mediating responses to dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2012;16(1):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ash CE, Merry BJ. The molecular basis by which dietary restricted feeding reduces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2011;132(1-2):43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maruyama H, Hisatomi A, Orci L, Grodsky GM, Unger RH. Insulin within islets is a physiologic glucagon release inhibitor. J Clin Invest. 1984;74(6):2296–2299. doi: 10.1172/JCI111658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rulifson EJ, Kim SK, Nusse R. Ablation of insulin-producing neurons in flies: Growth and diabetic phenotypes. Science. 2002;296(5570):1118–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.1070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linford NJ, Bilgir C, Ro J, Pletcher SD. Measurement of lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. J Vis Exp. 2013;71:50068. doi: 10.3791/50068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.