Abstract

Background

Long-term survival data on de novo malignancy are limited following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) when compared with controls without malignancies.

Methods

Over a 12 yr period at our institution, 50 of 1043 patients (4.8%) who underwent OLT were identified to have 53 de novo malignancies. The clinical characteristics and survival of these patients were retrospectively reviewed and compared with a control cohort of 50 OLT recipients without malignancy matched with the incidence cases by age, year of OLT, sex, and type of liver disease.

Results

Chronic hepatitis C, alcohol and primary sclerosing cholangitis were the three leading causes of liver disease. Skin cancer was the most common malignancy (32%), followed by gastrointestinal (21%), including five small bowel tumors, and hematologic malignancies (17%). The cases and controls were not significantly different in the immunosuppressive regimen (p = 0.42) or the number of rejection episodes (p = 0.92). The five- and 10-year Kaplan–Meier survival rates for the cases were 77% and 34%, respectively, vs. 84% and 70%, respectively, for the controls (p = 0.02 by log-rank test). Patients with skin cancers had survival similar to the controls, but significantly better than non-skin cancers (p = 0.0001). The prognosis for patients with gastrointestinal tumors was poor, with a median survival of 8.5 months after the diagnosis.

Conclusion

In this single institutional study, de novo malignancies after OLT were uncommon. Patients with non-skin cancer after OLT had diminished long-term survival compared with the controls. Our results differ from other reports in the high incidence of gastrointestinal malignancies with attendant poor prognosis.

Keywords: de novo malignancies, orthotopic liver transplantation

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is well established as a life-saving operation for patients with acute and chronic liver failure. Patient and graft survival rates exceeding 90% at one yr have been achieved in many transplant centers (1). The recipients of OLT are, however, subjected to lifelong immunosuppression with its many attendant risks. De novo malignancy following OLT has been increasingly reported in the literature in recent years (2–14), and is suggested as a major cause of late mortality in this population (15–17). The reported incidence of de novo malignancy has ranged from 3% to 26% (2–14), which is significantly increased compared with the general population (6, 8). Previous reports on the incidence, outcome and risk factors for de novo malignancies after OLT have shown differing results, depending on the length of follow-up, pre-transplant liver disease diagnosis, and the type of malignancy studied (16). There have been no controlled studies to fully assess the impact of de novo malignancy on long-term survival after OLT.

We report our single-institutional experience with long-term follow-up of all patients diagnosed with post-transplant de novo malignancy over a 12 yr period. A control cohort of OLT recipients without malignancy was identified and matched with the incidence cases by gender, age, date of transplant, and type of liver disease to better define the impact of de novo malignancies on long-term patient survival. We then sought to further characterize the spectrum, time course of development, and disease-specific outcome of these de novo malignancies after OLT.

Patients and methods

A total of 1043 adult patients underwent OLT at the University of California, San Francisco during a 12 yr period between 1988 and 2000. Among them, 50 patients (4.8%) developed de novo malignancy during the follow-up period and were identified through a search of a computerized hospital database. The records of these patients were retrospectively reviewed for age at the time of diagnosis of malignancy, cause of liver disease, interval from OLT to diagnosis of malignancy, the type of malignancy and histopathologic features, the immunosuppression regimen, and patient survival. The diagnosis of de novo malignancy was confirmed by histology in all cases. Patients with prior diagnoses of extrahepatic malignancies and those who underwent OLT for primary hepatobiliary tumors and developed recurrent tumors after OLT were excluded from this study. All patients had undergone routine pre-transplant tumor surveillance with chest radiograph, mammography, and colonoscopy within one yr of transplant.

Fifty OLT recipients who did not have any evidence of malignancy during the follow up period served as a control group, and were matched one-to-one with the incidence cases in terms of age (±3 yr), year of OLT, sex, and when possible, the type of liver disease. The investigators were blinded to the survival status of patients in the control group at the time of matching with the incidence cases.

All statistical analyses were performed with the software STATA 8.0. Results were expressed as mean (standard deviation) if continuous variables had a normal distribution and median (range) if they had a non-parametric distribution. Categorical variables were presented as percentages. The probability of death was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The development of tumor is treated as a time-dependent covariate. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline clinical and demographic characteristics for the cases and controls. The median age at the time of liver transplant was 53.2 yr for cases and 52.4 yr for controls. There were 26 men and 24 women among cases, and 23 men and 27 women among controls. The primary immunosuppressive regimen was not significantly different between the cases and controls, and included a triple regimen of cyclosporine, azothiaprine, and prednisone in the majority. Tacrolimus in combination with mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone was the immunosuppressive regimen used in a minority of subjects. The dose of prednisone was tapered to 5 mg daily after the 42nd post-operative day. Azothiaprine was continued for 6–12 months after OLT. Immunosuppression was decreased in all patients who were diagnosed post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) and where possible, after the diagnosis of non-skin tumors on a case-by-case basis. Chronic hepatitis C, primary sclerosing cholangitis and alcohol were the three leading causes of liver disease among cases and controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and demographic characteristics between cases and controls

| Cases (n= 50) | Controls (n= 50) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplantation | |||

| Median | 53.2 | 52.4 | |

| Range | 24–70 | 24–67 | 0.32 |

| Gender | |||

| Males | 26 | 23 | |

| Females | 24 | 27 | 0.55 |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dl | |||

| Mean | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.65 |

| Number of rejection episodes | |||

| Mean | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.92 |

| Number of deaths | 27 | 15 | 0.02 |

| Immunosuppressant | |||

| Cyclosporin | 43 | 40 | |

| Tacrolimus | 7 | 10 | 0.42 |

| Liver disease diagnosis | n | % | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic hepatitis Ca | 12 | 24 | 13 | 26 |

| Sclerosing cholangitisa | 11 | 22 | 10 | 20 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 9 | 18 | 9 | 18 |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 6 | 12 | 6 | 12 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| Chronic hepatitis B | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Fulminant hepatic failure | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Budd Chiari syndrome | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Hemochromatosisa | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Polycystic liver diseasea | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

The exact numbers could not be matched between cases and controls.

Three cases could not be matched to controls in the diagnosis of liver disease. One case each with cryptogenic cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis and hemochromatosis, was matched with a control patient with chronic hepatitis C, polycystic liver disease and cryptogenic cirrhosis, respectively. The cases and controls were not significantly different in the immunosuppressive regimen, the number and treatment of rejection episodes and serum creatinine (Table 1).

Spectrum of de novo malignancies

Table 2 shows the distribution of the 53 de novo tumors occurring in 50 patients. Skin cancer was the most common malignancy (32%), followed by gastrointestinal (21%) and hematological (17%) malignancies. All except one of the hematologic malignancies were either lymphoma or PTLD. Three cases presented with a second malignancy during the follow up period (Table 3): Bowen’s tumor and lymphoma; neuroendocrine tumor of small intestine and low grade transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder; and breast cancer and papillary serous cyst adenocarcinoma of ovary. In all three cases, the second malignancy was diagnosed within two yr of the first malignancy.

Table 2.

Type of de novo tumors developing in 50 liver transplant recipients

| Type | Number of tumors | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Skin | 17 | 32 |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 | 21 |

| Hematology | 9 | 17 |

| Lung | 5 | 9 |

| Breast | 4 | 8 |

| ENT | 3 | 6 |

| Gynecological | 2 | 4 |

| Urinary system | 2 | 4 |

Table 3.

Type and location of 53 de novo tumors diagnosed in 50 patients post-liver transplantation

| Organ | Site | n | Primary tumor type | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Skin | 12 | Squamous cell | |

| Skin | 2 | Bowen’s tumor* | *One case of lymphoma as second malignancy | |

| Perianal | 2 | Carcinoma in situ | ||

| Skin | 1 | Melanoma | ||

| Gastrointestinal | Colon | 6 | Adenocarcinoma | Metastatic in two cases |

| Small Intestine | 1 | Carcinoid tumor | ||

| 1 | Kaposi’s sarcoma | |||

| 1 | Neuroendocrine tumor** | **Low grade transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder as second malignancy | ||

| 1 | Villoglandular adenocarcinoma | |||

| 1 | Adenocarcinoma | Metastatic to liver | ||

| Hematology | 8 | Lymphoproliferative disease | EBV positive in two, negative in 2 and unknown in 4 | |

| Seven with monoclonal lymphoma* one with polyclonal | CNS in one EBV negative |

|||

| 1 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia | |||

| Lung | 2 | Adenocarcinoma | Metastatic to bone in one case | |

| 2 | Unknown cell type | |||

| 1 | Non-small cell | Metastatic to thoracic spine | ||

| ENT | Larynx | 1 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Metastatic to lymph nodes |

| Tongue | 1 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Metastatic to lymph nodes | |

| Tonsil | 1 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Metastatic to hard palate | |

| Breast | 3 | Adenocarcinoma*** | Metastatic to lymph nodes in one case; ***another case had papillary serous cyst adenocarcinoma of ovary as second malignancy | |

| 1 | Small cell anaplastic | Metastatic to liver and lung | ||

| Gynecological | Cervix | 1 | Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Ovary | 1 | Papillary serous cyst adenoma*** | ||

| Urinary system | Renal | 1 | Renal cell | |

| Urinary Bladder | 1 | Low grade transitional cell carcinoma** |

Asterisks (*, **, ***) refer to three separate patients with two malignancies.

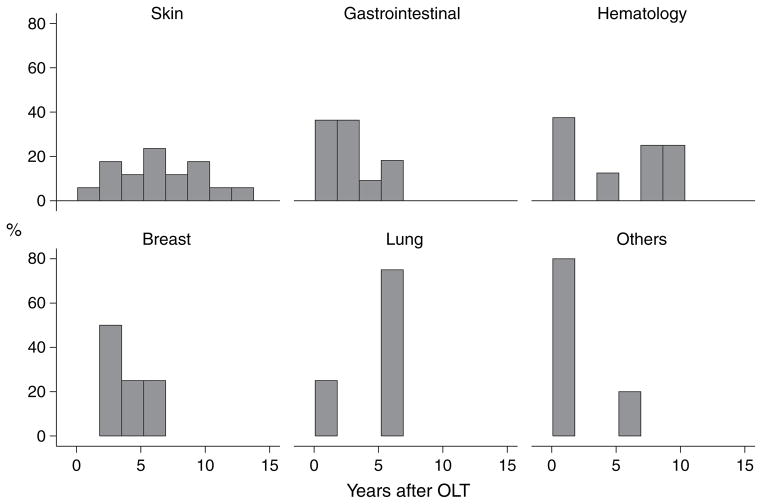

Table 3 summarizes in detail the type and location for the 53 de novo tumors. The median interval between OLT and the diagnosis of the first malignancy was 3.8 yr (range 1.3 months–12 yr). Fig. 1 shows the time to development of de novo tumors after OLT. The median interval between OLT and development of skin cancer was six yr (range 1–12 yr). The median interval between OLT and development of gastrointestinal tumor was 2.3 yr (range 2 months–6.1 yr). Three gastrointestinal tumors were diagnosed within seven months of OLT, including a neuroendocrine duodenal tumor, a colon cancer and a villoglandular adenocarcinoma of duodenum. Only one patient with colon cancer had a history of ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. The median interval between OLT and development of the eight cases of lymphoproliferative disease was 5.8 yr (range 1.3 months–9.7 yr). Three of these cases were diagnosed within nine months of OLT at time of highest immunosuppression: a monoclonal B-cell with positive EBV, a primary brain lymphoma and a polymorphic B-cell lymphoma with unknown EBV status. The median interval between OLT and development of lung cancer was 5.6 yr (range 9 months–5.8 yr). The median interval between OLT and development of breast cancer was 3.5 yr (range 2.3–5.7 yr). One of the four cases of breast cancer occurred in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis. Of the three ENT tumors, two were diagnosed within two months of OLT. Among the four cases of urogenital tumors, two were diagnosed in the first year after OLT, including a cervical tumor at seven months and a renal cell cancer at nine months after OLT.

Fig. 1.

Time to development of de novo malignancy after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) according to tumor type. *Others include three patients with ENT and four patients with urogenital tumors.

Survival analysis

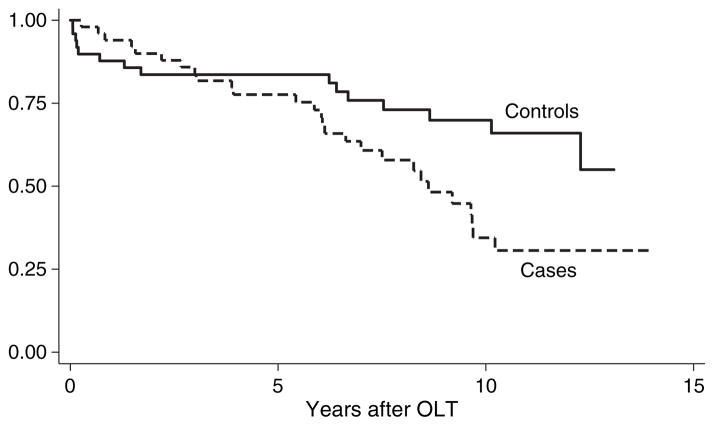

The median follow up after OLT was 6.7 yr (range, 2.5 months–13.9 yr) for cases and 7.8 yr (range, 21 d–13 yr) for controls. At last follow-up, 54% of cases and 34% of controls had died. The five and 10 yr Kaplan–Meier survival rates for the cases were 77% and 34%, respectively, vs. 84% and 70%, respectively for the controls (p = 0.02 by log-rank test) (Fig. 2). The median survival for cases was 5.9 yr after OLT.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for 50 patients with de novo malignancy (cases) and 50 patients without de novo malignancy (controls) after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Time zero represents the date of liver transplantation. The difference in survival between cases and controls was statistically significant by log-rank test (p = 0.02).

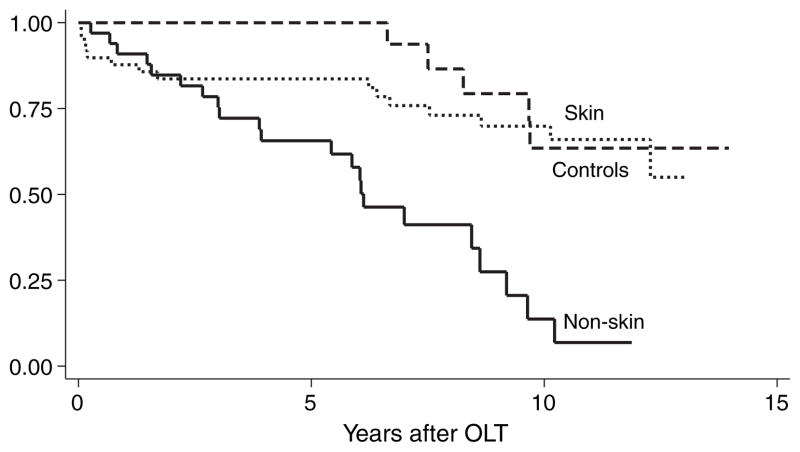

Survival differed between skin and non-skin cancer cases. Fig. 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curve for non-skin vs. skin cancers. Patients with skin cancer had post-transplant survival similar to the controls, but significantly better than those with non-skin cancer (p = 0.0001 by log-rank test; hazard ratio 4.9, 95% CI 1.67–14.2, p = 0.004). Among the cases, 22 of the 27 deaths were due to non-skin malignancies. The one patient with melanoma was alive at 11 yr after OLT, and two yr after the diagnosis of melanoma. The median post-transplant survival rates for patients with gastrointestinal, lung, and hematologic tumors were 3.9 yr, 6.0 yr, and 8.6 yr, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for patients with non-skin cancer vs. skin cancer and controls after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Time zero represents the date of liver transplantation. The 33 patients with non-skin had significantly worse survival than the 17 patients with skin cancer (p = 0.0001 by log-rank test; hazard ratio 4.9, 95% CI 1.67–14.2, p = 0.004).

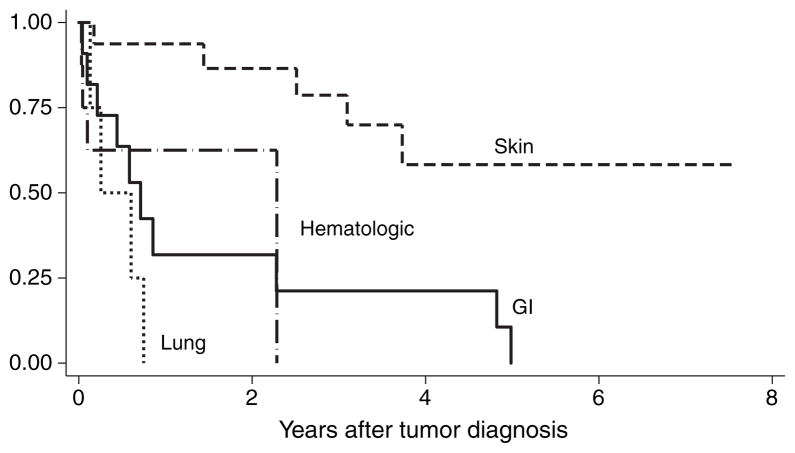

Fig. 4 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival after tumor diagnosis according to tumor type. There was a statistically significant difference in survival between different tumor types and skin cancer (p = 0.003 by log-rank test). The median survival after diagnosis of tumor for patients with lung, gastrointestinal, and hematologic tumors were three months, 8.5 months, and 27 months, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve after tumor diagnosis for patients with de novo malignancy after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) according to tumor type. Time zero represents the date of tumor diagnosis. A statistically significant difference was found in survival between different tumor types and skin cancer (p = 0.003 by log-rank test).

Discussion

In this single institution study involving over 1000 recipients of OLT over a 12 yr period, de novo malignancy was identified in 4.8% of patients at a median interval of 3.8 yr from the time of OLT. This incidence rate is among the lowest reported in the literature (2–14). Only Saigal et al. (11) and Kelly et al. (5) reported lower incidence rates at 2.6% and 4.3%, respectively, but neither series included lymphoid tumors. Herrero et al. from Pamplona, Spain (14) reported the highest incidence of post-transplant malignancies at 26% in a cohort of 187 OLT recipients. Possible explanations for the discrepancies in the reported incidence rates include differences in the size of population studies and the length of follow-up, given that the incidence of post-transplant malignancies increases over time (8), the immunosuppressive regimen used, and other potential risk factors for the development of these tumors. Although risk factors for the development of malignancies after OLT have not been fully elucidated, alcoholic liver disease appears to be the most often cited risk factor (11, 13, 16, 17). In our series, alcoholic liver disease represents one of the three leading causes of liver disease among those with de novo malignancy. Alcohol has been reported to increase karotypic chromosomal aberrations, expression of TGF-β in a variety of cells, and suppression of immunity towards cancer and infections in experimental models (9). In the present study, the cases and controls are not significantly different in terms of immunosuppressive regimen, and the number of rejection episodes. Length of follow-up is an unlikely explanation for our low incidence of post-transplant malignancies, as the median length of follow-up of 6.7 yr in our study cohort is comparable to other reports.

In our series, skin cancer represents the most common de novo malignancies, a finding that is generally consistent among published reports (5, 8, 11, 12, 14). Their survival was no different than the controls in spite of two cases with Bowen’s tumor and one with melanoma. In the University of Pittsburgh experience, PTLD was the most common type of post-transplant malignancy (6, 9). The Pittsburgh series are among the very few studies on post-transplant malignancies that include pediatric OLT recipients, in whom the frequency of PTLD has been reported to be significantly higher than adults (9, 18). We had fewer cases of EBV associated lymphoproliferative disease but the sensitivity of EBV diagnosis has changed over the time of the study so we might have underestimated the true incidence.

The present study includes a matched control cohort so that the impact of de novo malignancy on late mortality after OLT can be better defined (Figs. 2 and 3). Although de novo malignancy has been suggested in some studies as a major cause of late mortality after OLT (15, 17), there have been no published reports comparing long-term survival function between those with de novo malignancies and those without this complication after OLT. Our data also suggest that only patients with non-skin cancer post-transplant have diminished long-term survival, whereas patients with skin cancer after OLT have similar long-term survival when compared with the controls (Fig. 3). Similarly, Jain et al. (6) and Herrero et al. (14) reported that survival after diagnosis of post-transplant malignancy was better for the group with skin cancer compared with those with other solid-organ malignancies.

An unexpected finding in our study is the high proportion of gastrointestinal malignancies, which account for 46% of all non-skin, non-lymphoid tumors. The reported incidence of gastrointestinal tumors among solid-organ, non-lymphoid cancers in other large series ranges from 7% to 28% (6, 9, 11–14). Even more surprising is the diagnosis of small bowel malignancies in five of our cases, in addition to colorectal cancer in six patients. Among studies in which information on the type of gastrointestinal tumors was available (4–14), only a single case of non-lymphoid small bowel tumor (adenocarcinoma) was reported in the study by Saigal et al. (11) The interval between OLT and the diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancies also appears to be very short in comparison with other cancer types (Fig. 1). Despite routine colorectal cancer screening for all OLT candidates at our institution, it is possible that some cases of colorectal cancer were unrecognized at the time of OLT and one half of the cases of colorectal cancer were in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Our pre-transplant screening policy did not change over the study period and included yearly colonoscopy for all patients with inflammatory bowel disease and at least one screening colonoscopy for those subjects over 50 yr of age within one yr of transplant. In addition, small intestinal tumors are generally difficult to diagnose. In our series, the prognosis for patients with gastrointestinal tumors after OLT was extremely poor with a median survival of 8.5 months after the diagnosis. Based on these data we would recommend yearly screening colonoscopy for those with inflammatory bowel disease. In other transplant recipients, our data support consideration of more frequent screening after transplantation for intestinal cancer than is recommended for the general population.

In conclusion, this study confirms that patients with post-transplant non-skin cancer have diminished long-term survival at 10 yr when compared with a control group without post-transplant malignancy and those with skin cancers. Our results differ from other published reports in the high incidence of gastrointestinal malignancies, including small bowel tumors, with attendant poor prognosis. There is still a need for further studies on the time course of development and outcome of different subtypes of malignancies after OLT, so that better cancer surveillance protocols can be developed for medium- and long-term survivors of OLT.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Health to the University of California, San Francisco Liver Center (P30DK26743).

References

- 1.Yao FYK, Bass NM. Liver transplantation. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Kaplowitz N, Laine L, Owyang C, Powell DW, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. p. 2468. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheil AGR. Malignancy following liver transplantation: a report from the Australian combined liver transplant registry. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penn I. Posttransplantation de novo tumors in liver allograft recipients. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996;2:52. doi: 10.1002/lt.500020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonas S, Rayes N, Neumann U, et al. De novo malignancies after liver transplantation using tacrolimus-based protocols or cyclosporine-based quadruple immunosuppression with an interleukin-2 receptor antibody or anti-thymocyte globulin. Cancer. 1997;80:1141. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970915)80:6<1141::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly DM, Emre S, Guy SR, Miller CM, Schwartz MR, Sheiner PA. Liver transplant recipients are not at increased risk for non-lymphoid solid organ tumors. Cancer. 1998;83:1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain AB, Yee LD, Nalesnik MA, et al. Comparative incidence of de novo nonlymphoid malignancies after liver transplantation under tacrolimus using Surveillance Epidemiologic End Results data. Transplantation. 1998;66:1193. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199811150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galve ML, Cuervas-Mons V, Figueras J, et al. Incidence and outcome of de novo malignancies after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1275. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haagsma EB, Hagens VE, Schaapveld M, et al. Increased cancer risk after liver transplantation: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2001;34:84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung JI, Jain A, Kwak EJ, Kusne S, Dvorchik I, Eghtesad B. De novo malignancies after liver transplantation: a major cause of late death. Liver Transpl. 2001;11(Suppl 1):S109. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez C, Rodriguez D, Marques E, et al. De novo tumors after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:297. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saigal S, Norris S, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton N, O’Grady J. Evidence of differential risk for posttransplantation malignancy based on pretransplantation cause in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:484. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.32977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez EQ, Marubashi S, Jung G, et al. De novo tumors after liver transplantation: a single-institution experience. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:285. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.29350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benlloch S, Berenguar M, Prieto M, et al. De novo internal neoplasms after liver transplantation: increased risk and aggressive behavior in recent years? Am J Transplant. 2004;4:596. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrero JI, Lorenzo M, Quiroga J, et al. De novo neoplasia after liver transplantation: an analysis of risk factors and influence on survival. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:89. doi: 10.1002/lt.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pruthi J, Medkiff KA, Esrason KT, et al. Analysis of causes of death in liver transplant recipients who survived more than 3 years. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:811. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.27084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauffman HM, Cherikh WS, Cheng Y. Posttransplantation malignancies: a problem, a challenge, and an opportunity. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:488. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.33217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain A, DiMartini A, Kashyap R, Youk A, Rohal S, Fung J. Long-term follow-up after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease under tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2000;70:1335. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leblond V, Choquet S. Lymphoproliferative disorders after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2004;40:728. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]