Abstract

This study examined associations between partner unsupportive behaviors, social and cognitive processing, and adaptation in patients and their spouses using a dyadic and interdependent analytic approach. Women with early stage breast cancer (N=330) and their spouses completed measures of partner unsupportive behavior, maladaptive social (holding back sharing concerns) and cognitive processing (mental disengagement, and behavioral disengagement), and global well-being and cancer distress. Results indicated that both individuals' reports of unsupportive partner behavior were associated with their own holding back and their partners' holding back. Similar actor and partner effects were found between unsupportive behavior and behavioral disengagement. However, both patients' and partners' mental disengagement were associated only with their own unsupportive behavior. Together, holding back, mental disengagement, and behavioral disengagement accounted for one third of the association between partner unsupportive behavior and well-being and one half of the association between partner unsupportive behavior and intrusive thoughts. These results suggest that couples' communication and processing of cancer should be viewed from a dyadic perspective because couples' perceptions of one another's unsupportive behaviors may have detrimental effects on both partners' social and cognitive processing as well as their adaptation.

Keywords: Unsupportive behaviors, social and cognitive processing, disengagement coping, psychosocial adaptation to cancer, early stage breast cancer, couples

The diagnosis of breast cancer and its treatment can be challenging for both patient and spouse. Both members of the dyad manage practical, physical, and emotional stressors that are far-reaching, and, in some cases, permanent. During treatment, couples may deal with multiple medical appointments, altered household and child-care responsibilities, and financial disruptions due to changes in their ability to fulfill employment obligations (Banning, 2011; Tiedtke, de Rijk, Dierckx, Christiaens & Donceel, 2010). For patients, physical and emotional challenges are significant, and can include reduced confidence in body image, compromised feelings of femininity, and sexual dysfunction after mastectomy/lumpectomy/breast reconstruction, chemotherapy, and radiation (Fallowfield & Hall, 1991). Treatment side effects such as hot flashes, fatigue, lymphedema, memory impairment, and sleep problems can be stressful for both patient and partner (Bower et al., 2000). Emotional concerns for patient and partner revolve around fears about disease recurrence (Vickberg, 2003) and worries about the emotional effects of cancer on their children and family (Semple & McCance, 2010). These stressors contribute to higher rates of distress among women diagnosed with breast cancer as compared with rates for women in the general population (Hinnen et al., 2008). Estimates of partner distress are not significantly higher than the general population (Hinnen et al., 2008). However, partners express cancer-related concerns and needs for support (Zahlis & Shands, 1991).

Perceived Unsupportive Responses and Social-Cognitive Processing Theory

One adaptive way that couples manage cancer is by providing support to one another (Manne et al., 2004; Manne et al., 2006). Despite findings suggesting that the provision and receipt of support is important for both patient and spouse well-being during the cancer experience (Belcher et al., 2011), both patient and partner may perceive that their partner responds in an unsupportive manner. Perceived unsupportive behavior is defined as overtly critical behavior (e.g., criticizing how the person is coping with a stressor) or more subtle avoidant behavior (e.g., changing the topic). Perceived unsupportive behaviors are relatively uncommon but highly problematic, as they are strongly associated with distress among patients dealing with cancer (Figueiredo, Fries, & Ingram, 2004; Manne, Ostroff, Winkel, Grana & Fox, 2005).

The most prevalent explanation for the destructive nature of perceived unsupportive behaviors is derived from social-cognitive processing models of adaptation to difficult life events. Social-cognitive processing theories of difficult events are based on the notion that traumatic events are not consistent with the person's perception of the world as safe, and that they are appraised as threatening (Creamer, Burgess, & Pattison 1992). Individuals can reduce their negative reactions by integrating the event into their world view through cognitive processing, which consists of accommodating (e.g., realizing the world is a place where major events happen out of one's control) and/or assimilating (e.g., realizing the event is a reason to reconsider priorities) the event into their world view. When cognitive processing is successful and integration occurs, distress is reduced. Social processing is defined as talking about the event with others in one's social network about the event, in an effort to accomplish the cognitive processing goals described above. According to social-cognitive processing theories, perceived unsupportive responses interfere with adaptive social and cognitive processing (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Janoff-Bulman & Frieze, 1983; Tait & Silver, 1989). Perceived unsupportive responses can increase distress because they interfere with cognitive and social processing (Marin, Holtzman, DeLongis, & Robinson, 2007; Tait & Silver, 1989). Interference in cognitive processing can be measured by avoidance. Two indicators of avoidance are mental disengagement (e.g., avoiding thinking about the stressor) and behavioral (e.g., alcohol use) disengagement. Indeed, prior work suggests that perceived partner unsupportive behavior predict greater avoidance among breast cancer patients (Manne et al., 2005) and that avoidance is associated with increased distress (Shapiro, McCue, Heyman, Dey & Haller, 2010; Sherman, Simonton, Adams, Vural & Hanna, 2000).

Less is known about the effects of perceived partner unsupportive behavior on social processing. According to social-cognitive processing theory, perceived partner unsupportive behavior should interfere with social processing by increasing the likelihood that the person will hold back from sharing concerns with the partner because s/he perceives that s/he is not receptive (Tait & Silver, 1989). Pasipanodya and colleagues (2012) found that patient-reported perceived unsupportive behavior was associated with less sharing of daily events with the non-patient partner. Porter and colleagues (Porter, Keefe, Hurwitz & Faber, 2005) assessed both patient and spouse perceptions of unsupportive behavior and reported positive associations with patient holding back, but not with spouse holding back. Thus, research suggests, at least from the cancer patient's perspective, perceived partner unsupportive behavior is associated with maladaptive cognitive (avoidance) and less social (holding back sharing) processing of cancer.

The Dyadic Stress and Coping Paradigm

Our work is also guided by the dyadic stress and coping paradigm. The dyadic stress and coping paradigm defines a dyadic stressor as an event that affects both partners either directly or indirectly and triggers coping efforts on the part of both partners, which is labeled dyadic coping (Berg & Upchurch, 2007; Bodenmann, 1995; 1997; 2005). Cancer is viewed as a dyadic stressor (Kayser, Watson & Andrade, 2007). This paradigm suggests that coping responses are interdependent with regard to a shared stressor (Berg & Upchurch, 2007), and proposes that individuals engage in individual coping efforts which may affect the other partner's coping and the other partner's psychological outcomes (Berghuis & Stanton, 2002). Adopting a dyadic paradigm requires adopting a dyadic analytic approach. Indeed, recent studies have successfully used dyadic analytic approaches to understand relationship support and coping in cancer patients and their partners (e.g., Berg et al., 2008; Fagundes, Berg, & Wiebe, 2012).

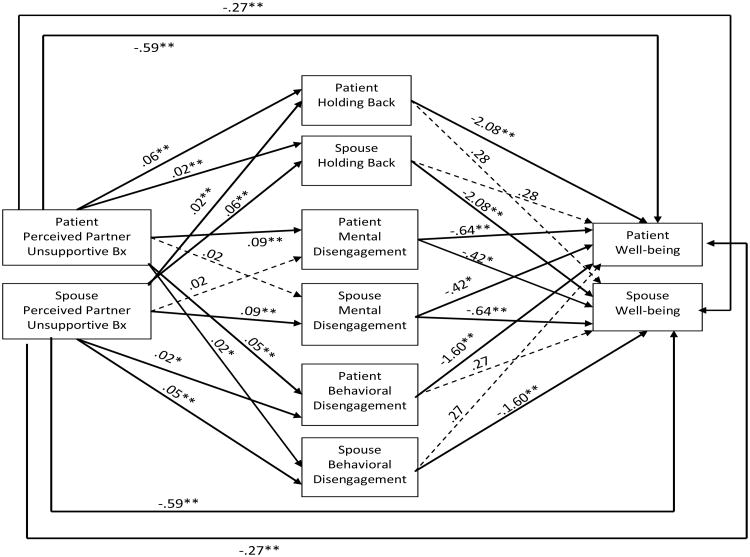

In the present study, we use the dyadic stress and coping framework and analytic approach. We also used a dyadic analytic approach to assess possible mediators of the associations between perceived partner unsupportive behavior and psychosocial adaptation. Ledermann and colleagues (2011) have proposed an extension of the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006) that can be used to estimate and test mediational processes in dyadic data. In the mediational model we are evaluating (shown in Figure 1), the effect of a person's input (X1) on his or her outcome (Y1), which is called the person's actor effect, can be mediated by his or her own standing on the mediator variable (M1) as well as his or her partner's standing on the mediator (M2). In other words, the effect of the patient's perception that her spouse is unsupportive on her own well-being may be mediated by her own mental disengagement (actor-actor mediation) or by her spouses' mental disengagement (actor-partner mediation), and likewise the effects of the spouse's perception of unsupportive behavior by the patient on the spouse's well-being may be mediated by either his own mental disengagement or the patient's disengagement.

Figure 1.

Proposed Actor Partner Independence Model Predicting Patient and Spouse Psychosocial Outcomes (Note: Bx= behavior).

The partner effect in the APIM (i.e., the effect of one person's inputs on the other person's outcomes) also may be mediated via actor or partner standing on the mediator. That is, the effect of the person's input (X1) on his or her partner's outcome (Y2) may be mediated by either the person's standing on the mediator (M1) or the partner's standing on the mediator (M2). Thus, the effect of the spouse's perception of unsupportive behavior on the patient's well-being may be mediated by the spouse's mental disengagement (partner-partner mediation), or it may be mediated by the patient's mental disengagement (partner-actor mediation). Similarly, the effect of the patient's perceptions of unsupportive spouse behavior on the spouse's well-being may be mediated by the patient's disengagement or the spouses' disengagement. Examining the specific dyadic paths of mediation is a unique approach that can provide insight into interpersonal processes for patients and their partners.

The Present Study

The present study sought to advance the literature on how perceived partner unsupportive responses relate to psychological adjustment among couples dealing with cancer in several ways. First, when studying possible mechanisms of perceived partner unsupportive behavior, prior studies have assessed perceived partner unsupportive responses as rated by the patient but have not assessed the non-patient partner's view of the patient's unsupportive responses. As noted above, cancer is a stressor that impacts both partners. Thus, the ill partner's level of unsupportive behavior towards the non-ill partner should play a role in the non-ill partner's social and cognitive processing and adjustment. Thus, we assessed non-ill partners' perceptions of patient unsupportive behavior. Second, prior studies have not evaluated the role of one person's perceptions of the partner's unsupportive behavior on the partner's social and cognitive processing. That is, if my partner perceives me as unsupportive, do I engage in less adaptive social and cognitive processing of the cancer experience? We assessed these effects in the present study. Third, we assess three possible indicators of maladaptive processing simultaneously: 1) holding back sharing concerns; 2) mental disengagement, and, 3) behavioral disengagement. Prior work has not assessed all three strategies together. Fourth, prior studies evaluating mechanisms for perceived partner unsupportive behavior have not used a dyadic analytic approach, which allows us to evaluate the inherent dependency of scores between partners and assess associations between one partner's behavior and another partner's behavior.

The study had three specific aims. The first aim was to evaluate the role of a person's (patient or spouse) perceptions of his or her partner's unsupportive behaviors and the person's and partner's social and cognitive processing. We hypothesized that perceived partner unsupportive behavior would be positively associated with one's own mental disengagement, behavioral disengagement, and holding back sharing cancer-related concerns (i.e., actor effects in the APIM). We also hypothesized that a person's (patient or spouse) perceptions of his or her partner's unsupportive behaviors would be positively related to the partner's mental disengagement, behavioral disengagement, and holding back sharing cancer-related concerns (i.e., partner effects). Second, we predicted that one's own mental disengagement, behavioral disengagement, and holding back would be related to higher levels of one's cancer distress and lower levels of one's own global well-being as well as one's partner's cancer-related distress (as measured by intrusive thoughts) and global well-being. Finally, we examined these three processing strategies as possible mechanisms for the associations of perceived partner unsupportive behaviors with patient and spouse cancer distress and well-being.

Method

Participants

Participants were 330 women with early stage breast cancer and their significant others drawn from a larger, ongoing randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a couple-focused group intervention for couples coping with breast cancer (Manne et al., unpublished data). For clarity of presentation, we use the term spouse to denote the patient's partner, even though there are some partners in the study who were not married to the patient.

Procedure

Patients were approached for study participation from the outpatient clinics of oncologists practicing in three comprehensive cancer centers in the Northeastern United States or in several smaller local community hospital oncology practices. Participants were part of a longitudinal study of the efficacy of two eight-session couple-focused group interventions. Criteria for study inclusion were as follows: a) patient had a primary diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma In Situ or Stage 1, 2, or 3a breast cancer; b) patient was female; c) patient had breast cancer surgery; d) patient and spouse were 18 years of age or older; e) patient and spouse were able to give informed consent; f) patient and spouse were English-speaking; and g) patient currently married or living with a significant other of either sex.

Eligible patients were identified and approached either after an outpatient visit, by telephone contact, or by mail. Patient and spouse were given a written informed consent document and the study questionnaire to complete and return by mail. Three hundred and thirty couples signed consent forms and completed the survey (13.8%). The most common reason provided for study refusal was that it would take too much time. The majority (62%) did not provide a reason.

Comparisons were made between patient participants and refusers with regard to available data (age, race/ethnicity, cancer stage, time since diagnosis, performance status). Results indicated that patient participants were diagnosed more recently than patient refusers (M participants = 3.8 months, SD = 5.0, M refusers = 4.9 months, SD = 6.9, t (2861) = -2.9, p < .01). No other differences were noted. We were not able to compare spouse refusers with participants because we did not have data available on spouse refusers.

Measures

Partner unsupportive behaviors

(Manne & Schnoll, 2001). The partner unsupportive behaviors scale consisted of 13 items assessing critical and avoidant responses by one's partner regarding the cancer, such as criticism of the partner's ways of handling the cancer and appearing uncomfortable when talking about the cancer experience. Sample items are: “Seemed angry or upset with me when they did something to help me,” and “Avoided being around me if I was not feeling well.” The patient version of the scale has demonstrated good construct validity (Manne & Schnoll, 2001). The only item that differed for spouses was “Avoided being around me” (“when I was not feeling well” was taken out). Items were rated on a 4-point response scale (1 = Never responded this way, 4 = Often responded this way). Scores could range from 13 to 52. Prior work has suggested that this scale comprises a single factor and illustrated satisfactory evidence of construct validity in that it is associated with significantly lower marital quality, less satisfaction with spouse support, and lower levels of perceived spouse support (Manne & Schnoll, 2001). In this study, internal consistency was .91 for both patient and spouse.

Holding back sharing concerns

A 6-item scale adapted from Pistrang and Barker (1998) was used. Participants rated the degree to which they held back sharing concerns in specific areas. Examples of concerns are: “Feelings of uncertainty regarding a possible recurrence of breast cancer” and “Changes in my/my partner's physical appearance (hair loss, weight gain, scars)”. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Talked about none of what I felt, 5 = Talked about all that I felt). Because not all concerns were endorsed, an average across concerns endorsed was used. Thus, scores could range from 0 to 5. Internal consistency for patients was .84, and for internal consistency for spouses was .81.

Mental Disengagement

The Mental disengagement subscale of the COPE was used (Carver et al., 1993). Mental disengagement consisted of psychological disengagement from the goal with which the stressor is interfering, through daydreaming, sleep, or self-distraction (Carver et al., 1993). Four items assessed turning to work or other distractions, trying not to think about the problem, and daydreaming. Sample items are “I turned to work or other substitute activities to take my mind off of things,” and “I daydreamed about things other than this.” Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = did not do this, 4 = did this a lot). Scale scores could range from 4 to 16. Participants reported how they coped with cancer in the past month. Internal consistency as calculated by Cronbach's alpha was .61 for both patient and spouse. Removal of items with lower item-total correlations would not result in an improvement in the internal consistency, and thus all items remained in the scale.

Behavioral disengagement

The Behavioral disengagement subscale of the COPE was used (Carver et al., 1993). Behavioral disengagement consisted of giving up, or withdrawing effort from, the attempt to attain the goal with which the stressor is interfering (Carver et al., 1993). Four items assessed giving up efforts to cope, giving up trying to reach one's goal, and reducing one's effort to solve the problem. Sample items are “I admitted to myself that I can't deal with it and quit trying,” and “I just gave up trying to reach my goal.” Participants were asked to rate how they dealt with stressful aspects of the cancer experience in the past month. Items were rated on a 4point Likert scale (1 = did not do this, 4 = did this a lot). Scale scores could range from 4 to 16. Participants reported how they coped with cancer in the past month. Internal consistency as calculated by Cronbach's alpha was .60 for both patient and spouse. Removal of items with lower item-total correlations would not result in an improvement in the internal consistency, and thus all items remained in the scale.

Global Well Being

The 14-item Positive Well Being subscale of the Mental Health Inventory -38 (Veit & Ware, 1983) was used. Sample items include, “During the past month, how much of the time has your daily life been full of things that were interesting to you?” and “During the past month, how much of the time have you felt calm and peaceful?” Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = All of the time, 6= None of the time). Scores could range from 14 to 84. Higher scores indicate greater well-being. Cronbach's alphas were .95 for patients and .94 for spouses.

Cancer Distress

Participants completed the Intrusions subscale of the IES (Horowitz, Wilner & Alvarez, 1979) which is a 14-item self-report measure focusing on intrusive ideation associated with a stressor, in this case breast cancer and its treatment. A sample item is, ““I thought about it when I didn't mean to.” This scale has been widely-used as a measure of cancer distress (e.g. Baider et al., 2003; Kraemer et al., 2011). Using a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 5 = often), participants rated how true each statement was for them during the past week. Scale scores could range from 0 to 70. Cronbach's alphas were .91 for both patient and spouse.

Demographic and Medical Variables

Age, sex, education, employment, and marital status were collected. Data regarding the patient's disease stage (1 to 3a), treatment status (chemotherapy, radiation), time since diagnosis, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group symptom ratings were obtained from the medical chart.

Analysis Plan

Our data analytic approach was based on the APIM (Kenny, Kashy & Cook, 2006) and the APIM for mediation (Ledermann et al., 2011). We used structural equation modeling (AMOS Version 19; Arbuckle, 2006) with a boot-strapping approach to estimate and evaluate our mediational APIM model. Our initial analysis examined the overall model that included all three mediating variables (holding back, mental and behavioral disengagement) as simultaneous mediators between perceived partner unsupportive behavior and either global well-being or intrusive thoughts. We then estimated results for each mediator separately so that we could examine more closely the specific dyadic pattern (e.g., actor-actor) in the mediational relationship.

Results

Descriptive information about the study sample is in Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in Table 2, spouses reported greater perceived partner unsupportive behavior than patients, but patients reported higher mental disengagement and higher cancer distress than spouses. In addition, the correlations on the diagonal of the table indicate that although patient and spouse scores were related (e.g., if one person reported high perceived partner unsupportive behavior, the other did as well), those associations were generally small to moderate in size.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Sample.

| Patient | Spouse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | N | (%) | M | (SD) | N | (%) |

| Age (years) | 55 | (10.5) | 57.7 | (27.2) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 330 | (100) | 2 | (0.6) | ||||

| Male | 0 | 328 | (99.4) | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| < High school | 5 | (1.5) | 6 | (1.8) | ||||

| High school | 63 | (19.1) | 57 | (17.3) | ||||

| Some college | 69 | (20.9) | 70 | (21.2) | ||||

| College degree | 71 | (21.5) | 66 | (20.0) | ||||

| Some graduate school | 39 | (11.9) | 45 | (13.7) | ||||

| Graduate degree | 81 | (24.5) | 77 | (23.3) | ||||

| Missing | 9 | (5.4) | ||||||

| Employment status | ||||||||

| Full time | 133 | (40.3) | 207 | (62.7) | ||||

| Part time | 41 | (12.4) | 17 | (5.2) | ||||

| On leave/retired | 78 | (36.0) | 83 | (25.1) | ||||

| Unemployed | 35 | (10.6) | 12 | (3.6) | ||||

| Missing | 2 | (0.6) | 11 | (6.6) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 289 | (87.6) | 279 | (84.5) | ||||

| Black | 31 | (9.4) | 30 | (9.1) | ||||

| Asian | 3 | (1.0) | 3 | (0.9) | ||||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 3 | (1.0) | 0 | (0) | ||||

| Other | 4 | (1.2) | 7 | (2.1) | ||||

| Missing | 11 | (5.4) | ||||||

| Relationship length (married) | 25.1 | (14.1) | 25.2 | (14.1) | ||||

| Relationship length (cohabitating) | 8.3 | (6.3) | 7.7 | (6.5) | ||||

| Disease stage | ||||||||

| DCIS (0) | 81 | (24.5) | ||||||

| 1 | 137 | (41.5) | ||||||

| 2 | 95 | (28.8) | ||||||

| 3a | 17 | (5.2) | ||||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Breast-conserving | 151 | (49.1) | ||||||

| Mastectomy | 168 | (50.9) | ||||||

| Current treatment | ||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 93 | (28.2) | ||||||

| Radiation | 61 | (18.5) | ||||||

| Both | 5 | (1.5) | ||||||

| No Rx | 145 | (43.9) | ||||||

| Missing | 26 | (7.9) | ||||||

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 5.1 | (4.4) | ||||||

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived Unsupportive Beh | .45** | .46** | .26** | .26** | -.52** | .38** | |

| 2. Holding back | .43** | .24** | .19** | .15** | -.37** | .26** | |

| 3. Mental Disengagement | .30** | .22** | .13* | .24** | -.31** | .33** | |

| 4. Behavioral Disengagement | .30** | .19** | .41** | .19** | -.36** | .29** | |

| 5. Global Well-Being | -.48** | -.38** | -.30** | -.30** | .45** | -.60** | |

| 6. Cancer Distress | .28** | .24** | .46** | .26** | -.47** | .33** | |

|

| |||||||

| Patient | M | 16.95 | 2.34 | 8.44 | 4.94 | 57.51 | 21.39 |

| SD | 5.79 | 0.97 | 2.47 | 1.32 | 13.19 | 14.90 | |

| Spouse | M | 19.88 | 2.26 | 6.41 | 4.77 | 57.18 | 15.89 |

| SD | 6.69 | 0.99 | 2.09 | 1.27 | 12.49 | 12.55 | |

| Paired t-test | t (329) | 8.11** | 1.19 | 12.20** | 1.84 | 0.43 | 6.26** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01.

N = 330 couples. Correlations for patients are above the diagonal and correlations for spouses are below the diagonal. The diagonal values are cross-partner correlations on the measure. Means and standard deviations are in the lower part of Table 2.

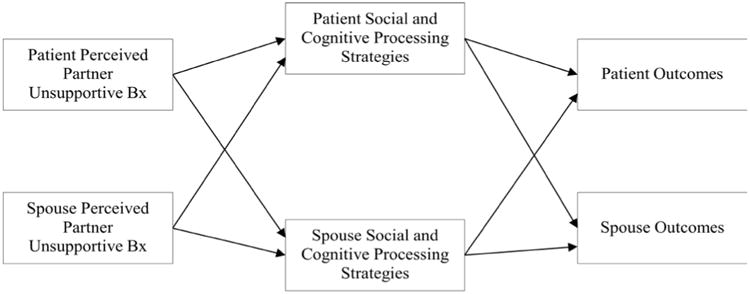

Model Predicting Global Well-being

In our initial step toward estimating the multiple mediator model in which the effects of patient and spouse perceived partner unsupportive behavior on well-being are mediated by both partners' holding back, we first tested whether there were significant differences in paths as a function of the patient/spouse role. That is, we tested whether: a) actor effect paths differed for patients versus spouses and b) partner effect paths differed for patients versus spouses, and no such differences emerged. Indeed, the model constraining these coefficients to be equal for patients and spouses fit well with c2(14) = 19.74, p = .14, RMSEA = .035, CFI = .992 and so this constrained model, which is more parsimonious than a model that allows actor and/or partner effects to vary by role, is presented in Figure 2.1

Figure 2.

Actor Partner Independence Model Predicting Patient and Spouse Well-Being (Note: Bx= behavior; statistically significant paths are depicted by solid lines and non-significant paths are depicted by dashed lines). Coefficients in the figure are unstandardized path coefficients.

As shown in Figure 2, the unstandardized regression coefficients indicate that both individuals' reports of unsupportive partner behavior were associated with their own holding back (i.e., actor effects) as well as their partner's holding back (i.e., partner effects). That is, the actor effects show that patients (and spouses) who reported that their partner engaged in more unsupportive behavior also reported holding back more. The partner effects show that patients (and spouses) who reported that their partner engaged in more unsupportive behavior had partners who reported holding back more – thus partners who are perceived as unsupportive held back more. There were similar actor and partner effects for unsupportive behavior predicting behavioral disengagement. In this case, the actor effect revealed that patients (and spouses) who reported that their partner engaged in more unsupportive behavior tended to be more behaviorally disengaged, and the partner effect showed that partners who were perceived as relatively unsupportive tend to report being more behaviorally disengaged. In contrast, the two partners' mental disengagement was predicted only by their own unsupportive behavior, indicating that a person's perception that his or her partner is unsupportive predicted that person's own mental disengagement, but not his or her partner's mental disengagement.

Each of the three mediators also predicted well-being. Significant actor effects emerged for holding back and behavioral disengagement such that individuals who reported greater holding back or greater behavioral disengagement reported lower well-being. Note that there was no evidence of partner effects for either of these mediators, so there was no evidence that having a partner who holds more back or is more behaviorally disengaged predicts a person's well-being. In contrast, mental disengagement showed evidence of both actor and partner effects. The actor effect shows that patients and spouses who were more mentally disengaged had lower well-being, and the partner effect shows that individuals whose partners were more mentally disengaged also tended to report lower well-being.

Table 3 presents the estimates, tests, and 95% confidence intervals for the total, direct, and indirect effects for the mediational model treating holding back, mental disengagement, and behavioral disengagement together as mediators using 500 boot-strapping samples. The final column of that table indicates that the three mediators together account for about one-third of the effect of a person's own unsupportive behavior on his or her own well-being, and about one-quarter of the effect of the partner's unsupportive behavior on the person's well-being.

Table 3. Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of the Three Mediators Together (Holding back, Mental disengagement, and Behavioral disengagement) on Well-Being and Cancer Distress.

| Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Percent Mediation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-Being | B | se | 95%CI | b | se | 95%CI | b | se | 95%CI | ||

| Actor | Patient | -.86** | .08 | -1.01 to -.71 | -.59** | .08 | -.75 to -.45 | -.26** | .05 | -.38 to -.78 | 30.2 |

| Spouse | -.86** | .08 | -1.01 to -.71 | -.59** | .08 | -.75 to -.45 | -.26** | .05 | -.38 to -.78 | 30.2 | |

| Partner | Patient | -.36** | .06 | -.49 to -.23 | -.27** | .07 | -.40 to -.11 | -.10* | .04 | -.19 to -.01 | 27.8 |

| Spouse | -.36** | .06 | -.49 to -.23 | -.27** | .07 | -.40 to -.11 | -.10* | .04 | -.19 to -.01 | 27.8 | |

| Cancer Distress | |||||||||||

| Actor | Patient | .61** | .08 | .45 to .78 | .32** | .09 | .13 to .49 | .30** | .06 | .19 to .42 | 49.2 |

| Spouse | .61** | .08 | .45 to .78 | .32** | .09 | .13 to .49 | .30** | .06 | .19 to .42 | 49.2 | |

| Partner | Patient | .44** | .11 | .21 to .64 | .31* | .12 | .08 to .53 | .13** | .05 | .03 to .24 | 29.5 |

| Spouse | -.04 | .12 | -.26 to .23 | -.16 | .13 | -.38 to .11 | .13** | .05 | .03 to .24 | --- | |

Note:

p <.05,

p < .01.

The 95% confidence intervals were based on bootstrapping with 500 samples.

We next took Ledermann and colleagues' (2011) approach to test the mediational paths for each mediator separately using a boot-strapping methodology. Beginning with holding back sharing concerns as the mediator, the effect of a person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on that person's own well-being was significantly mediated by the person's own holding back, and this indirect actor-actor mediational effect was b = -.137, p < .001, 95% CI: -.211 to -.075. Thus, the association between a person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior and that person's own well-being is most strongly mediated by the person's own holding back. In addition, the effect of the partner's perception that the person is unsupportive on the person's well-being was mediated by that person's reports of holding back concerns. The indirect effect of this partner-actor mediational pattern was, b = -.048, p < .001, 95% CI: -.089 to -.021, and so the finding that individuals whose partners report greater unsupportive behaviors tend to report lower well-being is also mediated by the individual's own holding back.

Turning to the mediational effects of mental and behavioral disengagement, the effect of a person's perception that his or her partner engages in unsupportive behavior on the person's own well-being was mediated by the person's own mental disengagement, b = -.086, p < .001, 95% CI: -.139 to -.046 (i.e., actor-actor), as well as by the partner's mental disengagement b = -.036, p = .025, 95% CI: -.074 to -.005 (i.e., actor-partner), a pattern that is very similar to that for holding back. In addition, the effect of a person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on that person's well-being was significantly mediated by the person's own behavioral disengagement, b = -.095, p < .001, 95% CI: -.157 to -.051 (actor-actor). Finally, the effect of the partner's perception that the person is behaving in an unsupportive manner on the person's well-being was mediated by the person's own behavioral disengagement, b = -.038, p = .041, 95% CI: -.086 to -.002 (i.e., partner-actor). The results for behavioral engagement suggest that although the effect of a person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior is most strongly mediated by the person's own mental disengagement, there is also an indication that the link is mediated by the partner's mental disengagement.

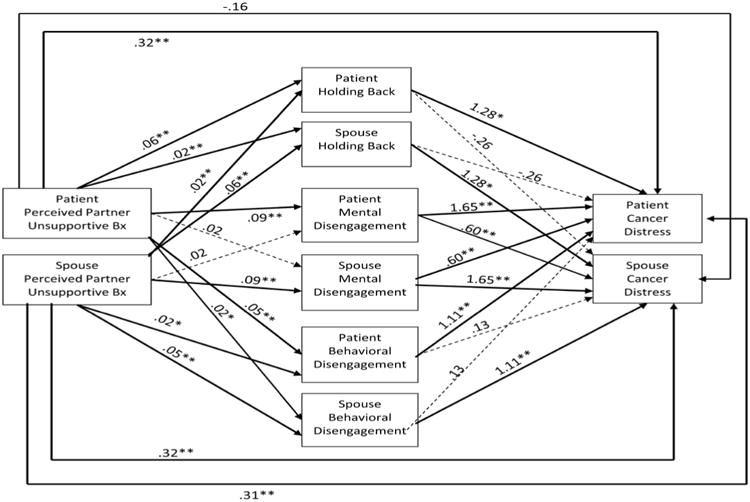

Model Predicting Cancer Distress

Next, we next examined whether the three mediators together could help to explain the link between perceived partner unsupportive behavior and cancer distress (Figure 3). Our initial model that constrained all of the actor effects and partner effects to be equal across patients and spouses did not fit well, with χ2 (14) = 32.41, p = .004. In this case, allowing the partner effects of perceived partner unsupportive behavior on cancer distress to differ for patients and spouses significantly improved model fit with χ2(1) = 11.07, p < .001. In this model, the effect of the spouse's perceived unsupportive behavior on the patient's distress was positive and statistically significant, but the effects of the patient's perceived unsupportive behavior on the spouse's distress was negative but not statistically significant. The model shown in Figure 3 fit well, with χ2 (13) = 21.34, p = .07, RMSEA = .044, CFI = .986.

Figure 3.

Actor-Partner Independence Model Predicting Patient and Spouse Cancer Distress (Note: Bx= behavior; statistically significant paths are depicted by solid lines and non-significant paths are depicted by dashed lines). Coefficients in the figure are unstandardized path coefficients.

As is evident in Figure 3, the paths from perceived partner unsupportive behavior to the three mediators are identical to those in Figure 2 and will not be discussed here. Instead, we focus on the effects of the proposed mediators on cancer distress and on the estimates and tests of total, direct, and indirect effects. Overall, the pattern of results for cancer distress is similar (but in an inverse direction) to that for well-being: Holding back and behavioral disengagement have significant actor effects, but non-significant partner effects. These actor effects show that patients (and spouses) who reported holding back more or being more behaviorally disengaged reported greater cancer distress. Results for mental disengagement were also similar to those for well-being in that both actor and partner effects are significant. Thus, individuals who were more mentally disengaged reported more cancer distress, and individuals whose partners were more mentally disengaged also reported more cancer distress. In addition, the direct effects of perceived partner unsupportive behavior show that individuals who perceived that their partners were more unsupportive reported more cancer distress. Finally, as noted earlier, patients whose spouses reported more partner unsupportive behavior also reported greater cancer distress.

The estimates, tests, and 95% confidence intervals for the total effects, direct effects, and indirect effects for the mediational model are in Table 3. The final column of that table indicates that the three mediators together account for about one half of the effect of a person's own perceptions of partner unsupportive behavior on his or her own cancer distress, and about one-third of the effect of the spouse's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on the patient's cancer distress. Note that there is no estimate of percent mediation for spouse's partner effect because there was no evidence of either a significant total effect or direct effect.

Finally, using Ledermann and colleagues' (2011) approach, we found that the dyadic mediational patterns for the effects of unsupportive partner behavior on a person's intrusive thoughts directly mirrored those for well-being. For holding back, the effect of a person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on the person's own intrusive thoughts was significantly mediated by the person's own holding back, b = .105, p = .003, 95% CI: .036 to .186 (i.e., actor-actor). In addition, the effect of the partner's perception that the person is being unsupportive on the person's cancer distress is mediated by the person's holding back, b = .037, p =.002, 95% CI: .012 to .076 (i.e., partner-actor). For mental disengagement as the mediator, we again found evidence of actor-actor mediation as the effect of the person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on that same person's cancer distress was significantly mediated by the person's own mental disengagement, b = .171, p < .001, 95% CI: .106 to .248. We also found evidence of actor-partner mediation for mental disengagement: The effect of the person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on that person's own intrusive thoughts was significantly mediated by the partner's mental disengagement b = .054, p = .004, 95% CI: .017 to .105. The effect of the person's perceived partner unsupportive behavior on his or her own cancer distress was significantly mediated by that person's own behavioral disengagement, b = .093, p < .001, 95% CI: .051 to .155 (actor-actor). Finally, the effect of the partner's perception that the person was unsupportive on the person's cancer distress was mediated by the person's own behavioral disengagement, b = .037, p = .046, 95% CI: .001 to .088 (partner-actor). In sum, the pattern of mediation for cancer distress was virtually identical to that for well-being. All three mediators showed strong actor-actor mediation suggesting that overall, the links between perceiving that a partner is unsupportive and the cancer distress was most strongly mediated by the extent to which the person held back from sharing concerns and used mental and behavioral disengagement. In addition, although the link is weaker, the pattern of results also suggested that the association between having a spouse who perceives greater unsupportive behavior and experiencing cancer distress is partially mediated by the extent to which the person held back and behaviorally disengaged.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to test an inter-individual model of perceived partner unsupportive behaviors, cognitive and social processing, and psychological adaptation in patients with cancer and their partners using a dyadic analytic approach. The results provide preliminary empirical support for crossover effects in the association between partner unsupportive behavior and social and cognitive processing and psychosocial adaptation. By using a dyadic approach, we were able to document a pattern of associations whereby perceived unsupportive behavior for both patients and spouses was significantly associated with the individuals' own social and cognitive processing and adaptation as well as their partners' processing and adaptation. Moreover, our models showed evidence of differences between patients and spouses only in a single case – the partner effect for perceived unsupportive behavior on cancer distress. These results highlight the importance of examining patient and spouse data together. First, our results suggest that individual efforts are associated with the partner's outcomes. Second, the stressful context of coping with breast cancer has similar effects for both patients and spouses. Analyses that examine patients and spouses separately may incorrectly imply that the underlying processes involved differ across role.

The associations between partner unsupportive behavior and social and cognitive processes indicate that if either partner perceives that the other partner is unsupportive, this perception has a detrimental association with one's own holding back of sharing concerns with that partner, one's own behavioral and mental disengagement, as well as one's partner's holding back and behavioral disengagement. The associations between patient's perceptions of partner unsupportive behavior on the patient's avoidant coping (Manne et al., 2005; Manne et al., 2003) and holding back (Porter et al., 2005) are consistent with previous research. The links between partner perceptions of patient's unsupportive behavior have been less studied. Porter and colleagues (2005) reported correlations between partners' perceived partner unsupportive behavior and holding back, but those correlations were not statistically significant.

Our findings suggest that couples' perceptions of one another's unsupportive behavior may have pervasive detrimental associations with both partners' cognitive and social processing of cancer. It is interesting to note that if either partner felt the other was unsupportive, they engaged in more mental disengagement, but perceptions of unsupportive behavior were not associated with their partner's mental disengagement. Unsupportive behaviors may initially be related to more overt behavioral indicators of processing (behavioral disengagement) or social processing of one's partner (holding back), but have less strong associations with on internal processing that may not be as visible to one's partner (e.g., daydreaming). Longitudinal research is needed to evaluate whether the partner effect for unsupportive behavior on one's partners' mental disengagement changes over time. It is also possible that, when rating one's spouses' unsupportive behavior, individuals consider the degree to which their partner is holding back sharing his or her concerns as well as behavioral disengagement strategies such as giving up dealing with the cancer. Although the items for our measure of unsupportive partner behavior do not appear to tap into the same construct as those for holding back or behavioral disengagement, it is possible that individuals consider how the other person is dealing with the cancer when completing the perceived partner unsupportive behavior scale.

The associations between social and cognitive processing strategies and intrusive ideation and well-being suggested that only mental disengagement had both actor and partner effects. That is, when one person is mentally disengaged from coping with the cancer, this is associated with that person's well-being and cancer distress, as well as his or her partner's well being and cancer distress. One possible explanation is that the partner feels more isolated in coping with the cancer experience when the other partner has mentally “checked out.” In contrast, holding back and behavioral disengagement showed what Kenny and colleagues (2006) refer to as an actor only pattern, in which only the person's behavior predict their own psychological outcomes. That is, if one person held back sharing, this did not predict his or her partner's well-being or cancer distress. Our findings are not consistent with previous work suggesting that holding back is associated with one's own distress and one's partner's distress (Porter et al., 2005). It is possible that holding back does not have an effect on one's partner because it is not “visible” (that is, one does not know the other is holding back) or because partners attribute this behavior as well-intentioned protection from distress. Indeed, protective buffering does not consistently predict more distress in one's partner (Manne et al., 2007).

The mediational analyses illustrated the complexity of associations between perceptions of one's partners' unsupportive behavior, one's own and one's partners processing, and one's own and one's partner's intrusive ideation and well-being. Taken together, the three mediators accounted for between one quarter to one half of the association between perceived partner unsupportive behavior and intrusions and/or well-being, which is an impressive figure. Individuals who perceived greater unsupportive partner behavior reported lower well-being in part because they and their partner held back sharing their concerns. In other words, if I feel that my partner is unsupportive, I hold back sharing concerns with my partner and my partner holds back sharing concerns with me, and my well-being is lower and intrusive ideation is higher. Similarly, individuals who perceived greater unsupportive partner behavior reported lower well-being and more intrusive ideation in part because they and their partner engaged in mental and behavioral disengagement. Thus, my own unhelpful behavior is associated with poorer processing on my own part, which is associated with my partner's psychological outcomes.

How do these findings advance both science and clinical work with cancer patients? From a research perspective, our findings clearly suggest close relationship partners' unsupportive behaviors impact their partners' as well as their own coping, distress, and well-being. Unsupportive behaviors have pervasive and large effects on distress and well-being, and it is only through an inter-individual modeling that we can elucidate the social context through which compromised well-being and distress can develop. It is interesting to note that spouses reported higher levels of unsupportive behavior on the part of patients than patients reported on the part of spouses. Thus, future studies should include spouse perceptions of patient behaviors.

From a clinical perspective, our findings illustrate that partners are aware of one another's support behaviors and, evidently, their partner's cognitive and social processes, even when they are holding back sharing concerns. When one behaves in a critical or avoidant manner towards a close other, it has a personal, as well as an interpersonal impact, and this impact is quite large: in some cases, the combination of cognitive and social processing variables accounted for 50% of the association between perceived unsupportive behavior and adaptation. Thus, interdependence models in which couples' outcomes are viewed as closely linked, such as those proposed by Lewis and colleagues (Lewis, DeVellis, & Sleath, 2002) and dyadic stress and coping paradigms (e.g., Bodenmann, 1997) are a good fit to the cancer experience. The motivation for change in couples' support provision to one another and coping should be considered using an interdependence perspective. Clinicians should point out that social and cognitive processing, as well as distress and well-being, should be viewed from a dyadic perspective. Couple-focused interventions may benefit from focusing on reducing both partners' unsupportive responses to each other and reducing both partners' use of disengagement coping.

It is important to point out the study limitations. Most important, the cross-sectional design limits conclusions about directionality of effects. It is possible that participants with lower levels of well-being and more cancer distress are more unsupportive. Thus, alternate models should be tested. Participants were primarily white, middle class, and well-educated. The participation rate was not high. Because this study was part of a couples' group intervention trial, this rate is not uncommon. Participants were diagnosed more recently than study refusers, suggesting that our results could be biased towards more recently diagnosed patients and less able to be generalized to women who were further out from diagnosis. Our measures of behavioral and mental disengagement did not have high internal consistency. Although we used intrusive thoughts as marker of cancer distress, others have conceptualized intrusions as a marker of cognitive processing (Creamer, Burgess, & Pattison, 1992; Fagundes, Berg, & Wiebe, 2012). Finally, due to the complexity of the model, we did not control for baseline marital satisfaction. It is possible that unsupportive behavior and mental and behavioral disengagement reflect marital dissatisfaction and/or characteristic marital interactions that pre-exist the cancer and occur outside the cancer context. Future studies should evaluate this possibility.

In conclusion, our findings are important because they illustrate the interdependence of couples' communication and processing of the cancer experience and suggest that unsupportive responses on the part of either partner have pervasive detrimental effects on couples' distress and well-being. Couple-focused interventions for couples coping with early stage breast cancer should focus on patients' unsupportive responses to the healthy spouse, which has not been traditionally targeted in dyadic interventions. The interdependence of couples' processing of the cancer on both partner's adaptation should also be emphasized in couple-focused interventions.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Cancer Institute grant CA78084 awarded to Sharon Manne. We would like to acknowledge the patients and partners who participated as well as the oncologists who provided access to their patients. We would also like to acknowledge Project Managers Sara Worhach, Tina Gajda, and Lauren Pigeon as well as research assistants Jennifer Burden, Joanna Crincoli, Emily Richards, and Kristen Sorice for study recruitment.

Footnotes

Although not shown in the figures, the residual variances for the mediators were allowed to correlate both within and between partners, and the residuals for the partners' distress were also allowed to correlate.

Contributor Information

Sharon Manne, Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Deborah A. Kashy, Michigan State University

Scott Siegel, Helen F. Graham Cancer Center

Shannon Myers, Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Carolyn Heckman, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Danielle Ryan, Fox Chase Cancer Center

References

- Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 7.0) [Computer Program] Chicago: SPSS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baider L, Andritsch E, Uziely B, Goldzweig G, Ever-Hadani P, Hofman G, et al. Effects of age on coping and psychological distress in women diagnosed with breast cancer: review of literature and analysis of two different geographical settings. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2003;46(1):5–16. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(02)00134-8. doi:S1040842802001348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banning M. Employment and breast cancer: a meta-ethnography. European Journal of Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20(6):708–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher AJ, Laurenceau JP, Graber EC, Cohen LH, Dasch KB, Siegel SD. Daily support in couples coping with early stage breast cancer: maintaining intimacy during adversity. Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):665–673. doi: 10.1037/a0024705. doi:2011-17047-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0024705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychology Bulletin. 2007;133(6):920–954. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. doi:2007-15350-005 [pii] 10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Butner J, Bloor J, Bradstreet C, Upchurch R, et al. Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23(3):505–516. doi: 10.1037/a0012687. doi:10/1037/a0012687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berguis J, Stanton A. Adjustment to a dyadic stressor: a longitudinal study of coping and depressive symptoms in infertile couples over an insemination attempt. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:433–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.7.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 1995;54:34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping - a systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology. 1997;47:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G. Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In: Revenson T, Kayser K, Bodenmann G, editors. Couples coping with stress. Washington: DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 33–50. doi:10/1037/11031-002. [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(4):743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, Noriega V, Scheier MF, Robinson DS, et al. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65(2):375–390. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer M, Burgess P, Pattison P. Reaction to trauma: a cognitive processing model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.452. doi:0021-843X/92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes CP, Berg CA, Wiebe DJ. Intrusion, avoidance, and daily negative affect among couples coping with prostate cancer: a dyadic investigation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(2):246–253. doi: 10.1037/a0027332. doi:2012-05100-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0027332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallowfield LJ, Hall A. Psychosocial and sexual impact of diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. British Medical Bulletin. 1991;47(2):388–399. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueirdo M, Fries E, Ingram K. The role of disclosure patterns and unsupportive social interactions in the well-being of breast cancer patients. PsychoOncology. 2004;13:96–105. doi: 10.1001/pon.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnen C, Ranchor AV, Sanderman R, Snijders TA, Hagedoorn M, Coyne JC. Course of distress in breast cancer patients, their partners, and matched control couples. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(2):141–148. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. Shattered assumptions: Towards a new psychology of trauma. New York: Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R, Frieze I. Theoretical perspective for understanding reactions to victimization. Journal of Social Issues. 1983;39:1–17. doi:0022-4537/38/0600-001. [Google Scholar]

- Kayser K, Watson LE, Andrade JT. Cancer as a “we-disease”: Examining the process of coping from a relational perspective. Families, Systems, & Health. 2007;25(4):404–418. doi: 10.1300/J010v35n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook W. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer LM, Stanton AL, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. A longitudinal examination of couples' coping strategies as predictors of adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(6):963–972. doi: 10.1037/a0025551. doi:2011-21205-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann T, Macho S, Kenny DA. Assessing mediation in dyadic data using the actor-partner interdependence model. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2011;18:595–612. doi:2009-17949-005 [pii] 10.1037/a0016197. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, DeVellis B, Sleath B. Social influence and interpersonal communication in health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer B, Lewis F, editors. Health behavior and health education. 3rd. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 240–264. [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, DuHamel K, Winkel G, Ostroff J, Parsons S, Martini R, et al. Perceived partner critical and avoidant behaviors as predictors of anxious and depressive symptoms among mothers of children undergoing stem cell transplantation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(6):1076–1083. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1076. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1076 2003-09784-013 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Norton TR, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, Fox K, Grana G. Protective buffering and psychological distress among couples coping with breast cancer: The moderating role of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21(3):380–388. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.380. doi:2007-12912-006 [pii] 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Norton TR, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. Cancer-related relationship communication in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(3):234–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Ostroff J, Rini C, Fox K, Goldstein L, Grana G. The interpersonal process model of intimacy. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):589–599. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. doi:2004-21520-005 [pii] 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Ostroff J, Winkel G, Grana G, Fox K. Partner unsupportive responses, avoidant coping, and distress among women with early stage breast cancer: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychology. 2005;24(6):635–641. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. doi:2005-14183-013 [pii] 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Schnoll R. Measuring supportive and unsupportive responses during cancer treatment: a factor analytic assessment of the partner responses to cancer inventory. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24(4):297–321. doi: 10.1023/a:1010667517519. doi:0160-7715/01/0800-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin TJ, Holtzman S, DeLongis A, Robinson L. Coping and the response of others. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:951–969. doi: 10.1177/0265407507084192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasipanodya EC, Parrish BP, Laurenceau JP, Cohen LH, Siegel SD, Graber EC, et al. Social constraints on disclosure predict daily well-being in couples coping with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(4):661–667. doi: 10.1037/a0028655. doi:2012-14969-001 [pii] 10.1037/a0028655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistrang N, Barker C. Partners and fellow patients: two sources of emotional support for women with breast cancer. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(3):439–456. doi: 10.1023/A:1022163205450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Hurwitz H, Faber M. Disclosure between patients with gastrointestinal cancer and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2005;14(12):1030–1042. doi: 10.1002/pon.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple CJ, McCance T. Parents' experience of cancer who have young children: a literature review. Cancer Nursing. 2010;33(2):110–118. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c024b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JP, McCue K, Heyman EN, Dey T, Haller HS. Coping-related variables associated with individual differences in adjustment to cancer. J Psychosocial Oncology. 2010;28(1):1–22. doi: 10.1080/07347330903438883. doi:918374406 [pii] 10.1080/07347330903438883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Simonton S, Adams D, Vural E, Hanna E. Coping with head and neck cancer during different phases of treatment. Head and Neck. 2000;22(8):787–793. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<787::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-r. doi:10.1002/1097-0347(200012)22:8<787::AID-HED7>3.0.CO;2-R [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait R, Silver RC. Coming to terms with major negative life events. In: Uleman JS, Bargh JA, editors. Unintended Thought. NY: Guilford; 1989. pp. 351–382. [Google Scholar]

- Tiedtke C, de Rijk A, Dierckx de Casterle B, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):677–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit CT, Ware JE., Jr The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(5):730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickberg SM. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS) Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;25(1):16–24. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2501_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahlis EH, Shands ME. The demands of the illness on the patient's partner. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1991;9(1):75–93. doi: 10.1300/J077v09n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]