Abstract

This study evaluated the financial impact of integrating a systemic care management intervention program (Community Care of North Carolina) with person-centered medical homes throughout North Carolina for non-elderly Medicaid recipients with disabilities during almost 5 years of program history. It examined Medicaid claims for 169,676 non-elderly Medicaid recipients with disabilities from January 2007 through third quarter 2011. Two models were used to estimate the program's impact on cost, within each year. The first employed a mixed model comparing member experiences in enrolled versus unenrolled months, accounting for regional differences as fixed effects and within physician group experience as random effects. The second was a pre-post, intervention/comparison group, difference-in-differences mixed model, which directly matched cohort samples of enrolled and unenrolled members on strata of preenrollment pharmacy use, race, age, year, months in pre-post periods, health status, and behavioral health history. The study team found significant cost avoidance associated with program enrollment for the non-elderly disabled population after the first years, savings that increased with length of time in the program. The impact of the program was greater in persons with multiple chronic disease conditions. By providing targeted care management interventions, aligned with person-centered medical homes, the Community Care of North Carolina program achieved significant savings for a high-risk population in the North Carolina Medicaid program. (Population Health Management 2013;17:141–148)

Introduction

In 2011, aged, and disabled Medicaid recipients represented 26% of Medicaid enrollees and accounted for 65% of expenditures nationally. During 2012 through 2021, Medicaid expenditures per disabled enrollee are projected to remain substantially higher than for aged, or non-disabled adult and child beneficiaries.1

Disabled Medicaid recipients are characterized by complex care needs arising from numerous chronic physical and behavioral conditions. They impose high costs on Medicaid related to ambulatory care sensitive admissions, multiple emergency room (ER) visits and readmissions, polypharmacy, and uncoordinated care in numerous settings.2 As Medicaid expenditures displace other state spending priorities, managing this population's costs has become an urgent matter.

Many states use managed care organizations (MCOs) to control Medicaid costs for most of their recipients but have been reluctant to mandate managed care for disabled recipients, citing numerous concerns: MCO inexperience with disabled populations, potential network inadequacy, and the lack of sufficient quality measures to guard against excessive service restrictions.2–3 Cognizant of these concerns, yet perceiving savings opportunities, some states have moved cautiously to test managed care solutions and alternative care models such as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) and accountable care organizations.2

The pathway to effective care and savings for this population is challenging. In a recent report of key issues related to Medicaid managed care for people with disabilities, the Kaiser Family Foundation highlighted the need for integrating behavioral and long-term supports and services with medical care.2 Although a few states (eg, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Texas) have demonstrated cost savings for the disabled,4 other approaches also have shown promise. An analysis of a large Medicare physician pay-for-performance initiative reported that almost all of the program's savings derived from dually eligible participants.5 Additional targeted disease and care management programs, alone or combined with PCMH, have reported successes,6,7 particularly those favoring a population health focus, integration with medical homes, and a focus on patient engagement,8,9,10 information system supports, strong care manager/physician communication, motivational interviewing, and pharmaceutical management assistance.11,12,13

Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC),14 an organization serving Medicaid recipients and their providers since 1998, has been a leader in creating, testing, and refining innovative care management programs. CCNC relies on a medical home model exemplified by a strong integration of professional care managers and information systems, and close collaboration across the full continuum of service providers. This study evaluates the economic impact of the CCNC program on non-elderly Medicaid recipients with disabilities. In an era where value-based purchasing and financial incentives are considered the pathway to providing more efficient, higher quality care, the CCNC program is an important experiment to understand the independent contribution to effective quality care from combining external care management with medical homes.

About CCNC

CCNC's 14 regional networks are staffed by physicians, pharmacists, and care managers providing multidisciplinary support to local hospitals and medical homes.14–15 The CCNC program has been described as a key example of a successful model supporting primary care in difficult populations.16–17 The CCNC care model is consistent with the Chronic Care Model (CCM)18, 19, 20 and the care coordinator models of team-based primary care.21 The following interventions—all with a track record of success—are employed by CCNC:

- change is targeted at system, provider, and person levels;

- collaboration is facilitated across disciplines and settings;

- timely, care critical information is disseminated to key providers in multiple locations;

- patient engagement is supported; and

- enrollees are encouraged to use preferred settings that emphasize ready access and provider continuity.18,22,23,24,25,26,27

Beginning in 2007, CCNC created specialized chronic care programs to serve high-cost, vulnerable aged, blind, and disabled Medicaid recipients. Distinguishing elements of this initiative were the establishment of a pharmaceutical home; broad-scope disease management for combinations of chronic diseases; improvements in access to urgent care for special needs; comingling mental health care in primary care settings; patient/family/caregiver training for system navigation and self-management; transition management; and system-wide reporting on high-risk needs and continuing care services. These and other features mirror attributes necessary for successful disease management and medical homes for high-risk patients.28,29,30 This study reports the impact of the CCNC programs from 2007 through the third quarter of 2011.

Methods

Previous reports by the actuarial firms Milliman and Mercer demonstrated overall savings from the CCNC program,31 particularly in reducing inpatient and ER use.14 These findings are consistent with evaluations of other care coordination programs.12 However, these actuarial reports relied on comparisons of costs with limited adjustments for age, sex, and disease burden scores, and although valuable, their insufficiency in not accounting for numerous other important factors might bias them. More sophisticated, quasi-experimental methods have been recommended to conduct robust evaluations of programs such as CCNC.32–33 Consistent with those recommendations, this study extends the earlier actuarial research by refining the sample, using pre-post comparison methods, controlling for a number of additional factors, and applying hierarchical regression models to adjust for potential correlation among outcomes.

The present study used 2 hierarchical modeling approaches with different samples to examine the effect of CCNC's program on eligible non-elderly disabled Medicaid recipients during the target time period. Each model attempts to estimate what would have happened to CCNC enrollees had they not been enrolled. Model 1 relies on almost all CCNC disabled recipients within the time period and uses each recipient's experience within and outside the CCNC program once (but with weighting to account for duration). Model 2 employs matching to create cohorts of enrolled and non-enrolled recipients, which are then similar in terms of observed characteristics. Model 1 compares the cost of a CCNC-enrolled month of care versus a non-enrolled month based on almost 5 years of data, after adjusting for other covariate values. Model 2 refined the regression by using a matched comparison sample and pre-post difference-in-differences analysis, analyzing fixed and random effects over time. This quasi-experimental modeling approach overcomes some of the traditional nonequivalency biases inherent in some previous evaluation studies of population health management.35 Establishing concurrent equivalent comparison groups can reduce threats to validity, especially for Medicaid care management interventions such as CCNC.36

In addition to the regression modeling the study team conducted additional analyses to test the validity of the findings. Validity is the extent to which one is measuring the phenomena that one thinks one is measuring. A technique referred to as “pattern matching”41,42 is a method to determine validity by comparing expected patterns derived from a theory or logic model to the patterns actually observed. The logic model for CCNC at its most basic is to increase primary care use and reduce the incidence of inpatient and ER services. With this logic model in mind, the study team examined patterns in the use of services to test the plausibility of the regression results.

Data preparation

Monthly Medicaid claims data from the period January 1, 2007 through September 30, 2011 were supplied by CCNC. These data, produced by the North Carolina Division of Medicaid Assistance, covered individuals with disabilities younger than age 65 for whom Medicaid was the sole source of insurance coverage. Several adjustments to the data were performed prior to model building. First, the initial month of enrollment was excluded because information on the precise date of enrollment was not available. Second, individuals were classified as disabled for the entire year if they were classified as disabled for the majority of the months in the year. Third, short skips in eligibility were filled in. The Medicaid population experiences considerable movement in and out of Medicaid status and incidences of eligibility loss often would be followed by Medicaid reinstatement with retroactive eligibility. To improve the accuracy of Medicaid eligibility in the data, single non-enrolled months were converted to enrolled months when the single non-enrolled month occurred within an enrollment period of at least 2 months prior and 2 months post. Less than .28% of all months in the study were converted in this way.

Analytic models

Hierarchical models34 by year were conducted to estimate CCNC program effects on cost. Model 1 included all CCNC-eligible Medicaid recipients. Each recipient's average cost per month, enrolled or not enrolled, was used as an observation. When a subject had experience as both enrolled and not enrolled, 2 observations were included in the sample with different values for CCNC status and separately calculated outcomes. Each observation was weighted by the months within the year with the given CCNC status. The key variable of interest in the model was the indicator of CCNC enrollment. Additional variables included race, sex, age, physician region, physician group affiliation, calendar year, and measures of disease morbidity and behavioral health (described in the following Variables section). To account for potential clustering, variables for regional differences were included as fixed effects and variables for physician group were included as random effects.

The Model 2 sample consisted of cohorts of intervention and comparison of Medicaid members matched on preenrollment pharmacy use, race, age, year, and months in pre-post periods, ACRG (an aggregation of Clinical Risk Groups discussed later in this article), and behavioral health. The direct matching technique on these variables derived from Coarsened Exact Matching.39–40 To construct the sample for this model, each intervention subject (ie, Medicaid recipient enrolled in CCNC) was randomly matched to 10 comparison subjects, selected with replacement, to form case-control clusters.

Model 2 includes all the variables of the first model—the individual characteristics as well as geographic indicators as fixed effects and physician group indicators as random effects. In addition, the triplet consisting of the CCNC indicator, the pre-post indicator, and their interaction is included in Model 2 to facilitate the difference-in-differences estimate of CCNC impact. The number of months involved in calculating the observation's average cost in the post period serves as a weight for each CCNC enrollee. Because comparison subjects were matched on this number of months, they had the same weight as the CCNC enrollee they matched to. All regression analyses were conducted with SAS Proc Mixed, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).37 The hypothesis tested by the study was that the CCNC program would significantly reduce average monthly cost, and therefore a 1-sided test for significance at .05 was adopted.

Variables

Age was defined as age at the end of the year being modeled. Race and sex were each coded as binaries. Zip code of the primary care physician defined region. Months of enrollment were months enrolled in the calendar year.

3M Clinical Risk Groups (CRG)38 defined physical and behavioral health disease burden. CRGs use claims-based diagnoses to assign subjects to mutually exclusive, hierarchically ranked risk groups. When a CRG had less than .1% of observations, it was reclassified into an aggregated CRG (ACRG) group. CRG “weights” also were calculated for tabular display.

The variables identifying Chronic Dominant Mental Health (eg, schizophrenia) and Chemical Dependency are “everlasting,” meaning that once set to a value of 1, they retain that value afterward. This approach takes into account the concept that the conditions represented often continue long after any diagnosis and present a “time spanning” burden to the patient and their care.

Model 2 also included indicators for a preintervention and a postintervention period, and an indicator for the interaction of the postintervention period with the treatment condition to derive the estimate for the program's impact.

The dependent variable for the cost analysis was per member per month (PMPM) spending on all medical services, including pharmacy and the administrative program costs for enrolled members. All data included at least a 3-month “run-out” to allow for claims lag. Claims at 4 standard deviations from the mean within CRG/age strata were capped at this “4 standard deviation above” value. Only .65% of the sample was subject to this capping.

Results

Model 1

The sample for Model 1 included 169,667 CCNC-eligible Medicaid recipients, ages 0 to 64, who were not already enrolled in the CCNC program in January 2007. Recipients enrolled in CCNC as of January 2007 were not included because there was no preprogram information on their use of health care. Table 1 presents the distribution of member months during the covered time period from January 2007 to September 2011.

Table 1.

Model 1 Non-Matched Population: Characteristics of non-Elderly Disabled Individuals by Enrolled Status—All Years (N=169,667)

| Characteristic | Non-Enrolled | Enrolled | P valueafor Ho: no difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Months of Medicaid Eligibility | 2,550,284 | 1,737,096 | |

| Medical Risk Score (CRG Weight)b | 0.95 | 1.11 | <.001 |

| Age (years) | 37 | 35 | <.001 |

| Male | 53% | 52% | <.001 |

| White | 46% | 45% | <.001 |

| Serious Mental Illness | 20% | 24% | <.001 |

| Chemical Dependency | 7% | 8% | <.001 |

Associations determined by month weighted t tests and chi-square.

Relative average cost for individuals with equivalent CRG/Age combinations, normalized to a population average of “1.”

CRG, Clinical Risk Group.

Beneficiaries enrolled in CCNC were younger on average, had a higher disease burden, and a slightly higher prevalence of mental health conditions and chemical dependency.

The direct effect of program enrollment was associated with statistically significant cost savings, ranging from almost $190.91 PMPM in the first year to $63.74 PMPM in the last study year (Table 2). Total savings from the program can be derived from multiplying the direct effect of enrollment each year against the number of months in the enrolled category. The study team estimated enrollment in CCNC produced a total cost savings of $184,064,611 over the 4.75 years. These savings are net of CCNC program costs and represent a 7.87% relative savings from the average PMPM cost.

Table 2.

Model 1 Savings Impact of CCNC Enrollment by Year for Non-Matched Sample of Non-elderly Medicaid Recipients with Disabilitiesa

| Year | Enrolled Months | Unenrolled Months | Savings | Standard Error | t Value | Pr>|t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 76193 | 535243 | −$190.91 | 22.16 | 8.61 | <.0001 |

| 2008 | 250329 | 573317 | −$153.71 | 13.99 | 10.98 | <.0001 |

| 2009 | 421067 | 575421 | −$117.54 | 12.61 | 9.32 | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 551886 | 508594 | −$97.22 | 11.92 | 8.16 | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 437621 | 357709 | −$63.74 | 13.37 | 4.77 | <.0001 |

Mixed model regression of each calendar year total cost of care on enrollment, region, race, age, sex, CRG, mental health and chemical dependency as direct effects, physician group as a random effect, and weighted by months of eligibility in the year. All models achieved null model likelihood ratio test Pr>chi-square <.0001. CCNC, Community Care of North Carolina; CRG, Clinical Risk Group.

The study team theorized that CCNC would have the greatest impact on persons with severe chronic conditions given the targeted program design features for this subpopulation of high-risk individuals. As presented in Table 3, when Model 1 was applied to persons with multiple dominant chronic conditions there was an even greater cost savings, ranging from $228.41 PMPM during 2007 to $92.61 PMPM during 2011.

Table 3.

Model 1 Savings Impact of CCNC Program Enrollment by Year for Non-Matched Sample of Non-elderly Medicaid Recipients with Disabilities and Multiple Dominant Chronic Conditionsa

| Year | Enrolled Months | Unenrolled Months | Savings | Standard Error | t Value | Pr>|t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 34089 | 221247 | −$228.41 | 40.47 | 5.64 | <.0001 |

| 2008 | 122745 | 239359 | −$202.45 | 23.80 | 8.51 | <.0001 |

| 2009 | 215833 | 233180 | −$173.90 | 21.15 | 8.22 | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 282697 | 206993 | −$122.89 | 19.34 | 6.35 | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 220578 | 152853 | −$92.61 | 21.44 | 4.32 | <.0001 |

Mixed model regression of each calendar year total cost of care on enrollment, region, race, age, sex, CRG, mental health and chemical dependency as direct effects, physician group as a random effect, and weighted by months of eligibility in the year. All models achieved null model likelihood ratio test Pr>chi-square <.0001.

CCNC, Community Care of North Carolina; CRG, Clinical Risk Group.

Model 2

Matching CCNC enrollees with sets of similar comparison recipients, as done in Model 2, yields alternative estimates of the effect of the CCNC program on the total cost of care. Because of the need to have pre-CCNC experience, some CCNC enrollees had to be dropped. The matched sample for Model 2 represents 65% of all the enrollees in the non-matched sample and 79% of all enrolled months. Table 4 illustrates the general equivalence achieved in the preenrollment period. Preenrollment differences show as significant because of the sizes of the groups, but inclusion of these variables in the models as covariates should adjust for any remaining bias.

Table 4.

Model 2 Matched Sample: Characteristics of non-Elderly Disabled Individuals by Enrolled Status—All Years (N=102,116)

| Preenrollment Period | Postenrollment Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Non-Enrolled | Enrolled | P valueafor Ho: no difference | Non-Enrolled | Enrolled | P valueafor Ho: no difference |

| Months of Medicaid Eligibility | 5,275,017 | 537,336 | 6,709,286 | 682,006 | ||

| *Medical Risk Score (CRG Weight)b | 0.89 | 0.93 | <.0001 | 0.87 | 0.94 | <.0001 |

| *Age (years) | 38.2 | 38.4 | <.0001 | 37.7 | 37.5 | <.0001 |

| *Male | 53% | 53% | .0154 | 53% | 53% | .8425 |

| *White | 47% | 47% | .0220 | 46% | 46% | .0037 |

| *Pharmaceutical Cost | $191 | $179 | <.0001 | $207 | $273 | <.0001 |

| *Serious Mental Illness | 23% | 24% | <.0001 | 22% | 23% | <.0001 |

Matching variable.

Associations determined by month weighted t tests and chi-square, both with period clustering accounted for.

Relative average cost for individuals with equivalent CRG/Age combinations, normalized to a population average of “1.”

CRG, Clinical Risk Group.

Regression results from Model 2 are presented in Table 5. Model 2 demonstrated statistically significant savings from CCNC in each year after the first, with an increasing rate of savings most years.

Table 5.

Model 2 Savings from CCNC Program Enrollment by Year for Matched Individuals

| Year* | Postenrollment Months | Savings | Standard Error | t Value | Pr>|t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 28,492 | $27.14 | 44.91 | 0.60 | 0.5455 |

| 2008 | 319,848 | −$52.54 | 18.77 | −2.80 | 0.0051 |

| 2009 | 348,136 | −$80.75 | 17.33 | −4.66 | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 381,482 | −$72.65 | 17.02 | −4.27 | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 286,054 | −$120.69 | 17.16 | −7.03 | <.0001 |

Year post period ended.

Mixed model regression of each calendar year total cost of care on enrollment, region, race, age, sex, CRG, pre period months, mental health and chemical dependency as direct effects, physician group as a random effect, and weighted by months of post period. All models achieved null model likelihood ratio test Pr>chi-square<.0001. CCNC, Community Care of North Carolina; CRG, Clinical Risk Group.

Utilization trend analysis

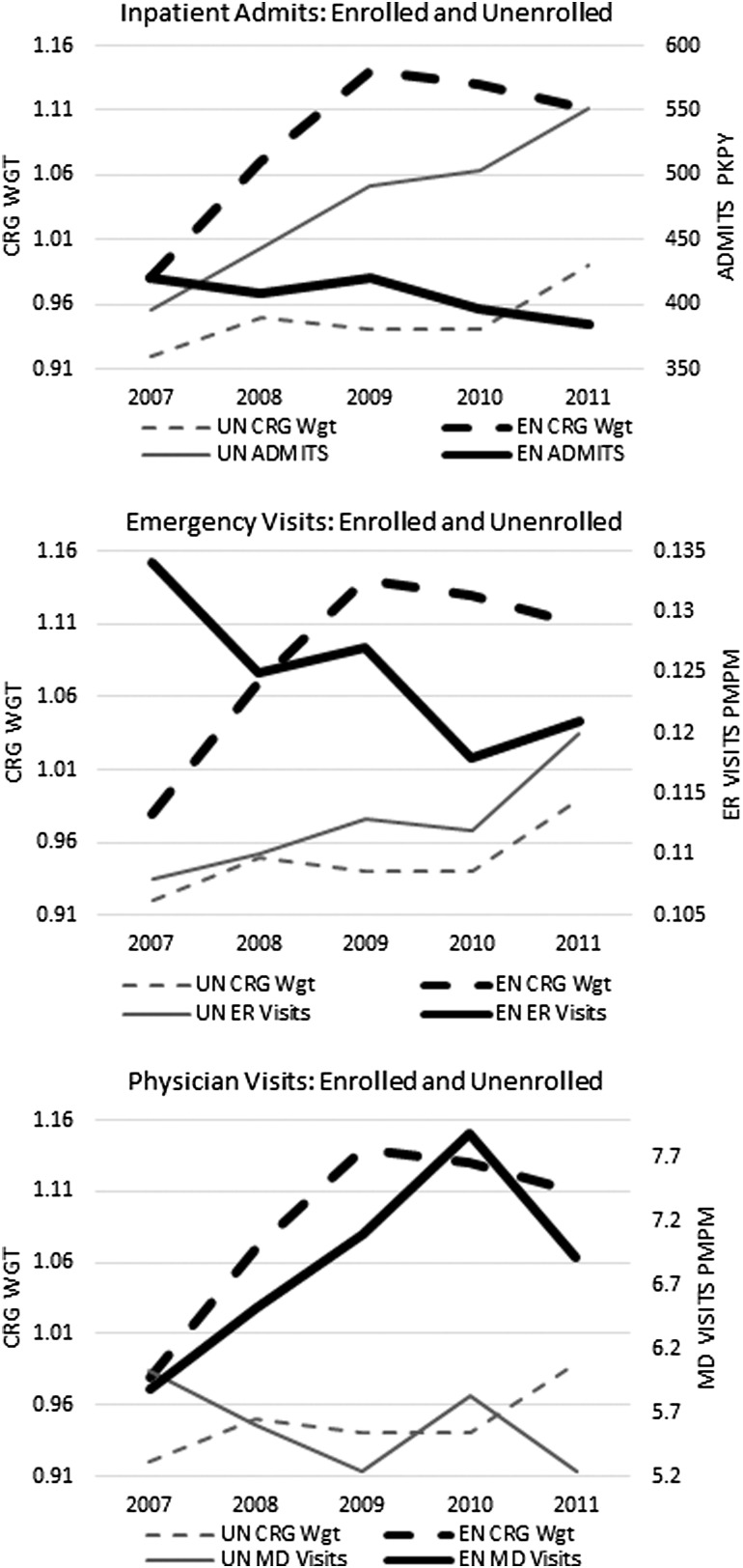

The study team also examined health care utilization in the Model 1 population. Consistent with the objectives of the CCNC program model, in every year after the first one (Figure 1), the rate of hospitalizations was significantly (P<.001) lower for enrolled members, even though their risk score was higher. Inpatient admission rates declined from 420 per thousand per year (PKPY) in 2007 to 384 PKPY in 2011 among enrolled members, while increasing from 396 PKPY to 552 PKPY among the unenrolled. At the same time, in concert with the emphasis on improved access to ambulatory physician services, in every year after 2007, the rate of non-acute physician visits by enrolled members was significantly higher (P<.001) than for unenrolled (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Utilization of health services and disease burden (CRG weight) among enrolled and unenrolled over 5 years. CRG, Clinical Risk Group; EN, enrolled; ER, emergency room; MD, physician; PKPY, per thousand per year; PMPM, per member per month; UN, unenrolled; WGT, weight.

ER visits that did not result in admissions were higher for the enrolled population initially, but over time the difference narrowed and became insignificant (Figure 1). This occurred despite the higher disease burden among the enrolled. Taken together, this evidence is consistent with the program's logic model and buttresses the conclusions that there were real program effects.

Discussion

This investigation highlighted the performance of a statewide care management program for non-elderly Medicaid recipients with disabilities, which encouraged both wraparound and embedded services in PCMHs. CCNC's success suggests carefully designed, large-scale care management programs can have a significant impact and can increase program efficiency independent of financial risk sharing. The findings of this study are consistent with and confirm previous actuarial studies, removing the threats to validity inherent in non-matched, cross-sectional analyses.

The results of 2 analytic models, both showing positive impact from CCNC, help to bracket the estimated range of potential program benefit. Although these 2 models provide different perspectives, they converge on the same conclusion—the CCNC program is cost-effective. The complementary results from Model 2 should satisfy Model 1 concerns about alternative explanations such as selection effects. Furthermore, this study goes beyond estimation of overall cost impacts, identifying key sources of savings and highlighting the causal pathway that links the intervention to the savings. Other reports15,46 delineate CCNC quality initiatives that dovetail with the present study findings of increased access to ambulatory care and reduced acute care—evidence that efficiencies were achieved without sacrificing quality.

It can be argued that Model 2 represents a more accurate picture of program impact. The approach of Model 2 better addresses the threat to validity from unmeasured differences between the enrolled and non-enrolled, which might systematically relate to enrollment and also affect utilization of care and its corresponding cost. It only compares individuals with at least 3 months of Medicaid and has better covariate controls. Model 2 CRG risk scores are more robust and reduce many potential sources of bias through the matching procedure. Based on Model 2 results, it is also reasonable to suggest that the program has gained effectiveness as it has matured.

Previous positive evaluations of the CCNC program have been challenged and rebutted.47,48,49 In this context, the methods used in the present study can be seen as advancing the analytic “state of the art” for evaluating CCNC. Nevertheless, although the study team employed more rigorous methods than previous work, the results from the present study are consistent with prior actuarial studies and more recent research50—thus, there is a preponderance of evidence that the targeted system-wide efforts of CCNC are having a positive impact on Medicaid recipients.

The present analysis provides a complementary tool for those who advocate incentivizing clinician behavior through value-based health care financing, an approach that also has shown some promise for cost savings and quality improvement.43,44,45,5 The mechanism for the purported savings from value-based programs rests on changing referral patterns, targeting patients, and improving care coordination. However, the role of financial incentives in achieving these objectives is not clear. The experience of CCNC provides evidence for the independent effect of accessing a primary care medical home and using a community-based framework for care coordination and quality improvement.

Limitations

Several limitations to the study should be considered. Although the study team controlled for clinical risk burden and patient demographic factors including geographic region, they could not fully account for all differences in health system practices and socioeconomic factors that influence care utilization, nor did they include a direct measure of dose or test specific activities to parse the impact of particular CCNC program activities. Explicitly including these factors would provide additional insight. It also should be noted that this study did not adjust for Medicaid reimbursement differentials among providers and, to the extent enrollees systematically frequented higher or lower cost providers for the same service, it could have influenced results. However, there is no financial incentive for providers or recipients to choose services on the basis of cost, a fact that lessens the probability of any systematic bias in the results from this factor. Finally, although the matching approach used in Model 2 is thought to better protect against potential threats to validity in the comparisons, it must be noted that without true randomization the possibility remains that unmeasured variables could lead to bias in results.

Conclusion

Enrollment in CCNC was associated with significant cost savings for the non-elderly disabled—savings that were greater for persons with multiple chronic disease conditions. By providing targeted care management interventions, aligned with person-centered medical homes, and with a focus on systems to enable change, the CCNC program demonstrates an important part of the solution for creating lasting health care improvement.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of Tom Galligan, BA, Community Care of North Carolina, and Steve Owen, MSM, North Carolina Division of Medical Assistance, who provided reviews of the project and feedback on the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the analyses, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Mr. Fillmore works for Treo Solutions, which provides analytic and information services to CCNC. The results of this and other evaluation studies of the CCNC program have no contractual or other bearing on the financial relationship between the parties. Dr. DuBard is employed by Community Care of North Carolina, which manages the program under evaluation in this study. Dr. Ritter is a statistical and methods design consultant to Treo Solutions, providing them with analytic support on the CCNC project. Dr. Jackson is employed by Community Care of North Carolina, which manages the program under evaluation in this study.

References

- 1.Truffer CJ, Klemm J, Wolfe C, Rennie K. 2012Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid. Available at: <https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/downloads/MedicaidReport2012.pdf>. Accessed September10, 2013

- 2.Kaiser Family Foundation. People with Disabilities and Medicaid Managed Care: Key Issues to Consider. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns ME. Medicaid managed care and health care access for adult beneficiaries with disabilities. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(5 pt 1):1521–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewin Group. Medicaid Managed Care Cost Savings—A Synthesis of 24 Studies: Final Report; 2004. Available at: <http://www.lewin.com/publications/publication/395/>. Accessed January29, 2013

- 5.Colla CH, Wennberg DE, Meara E, et al. Spending differences associated with the Medicare physician group practice demonstration. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1015–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takach M. About half of the states are implementing patient-centered medical homes for their Medicaid populations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2432–2440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdier JM, Byrd V, Stone C. Enhanced primary care case management programs in Medicaid: issues and options for states. Available at: <http://www.chcs.org/usr_doc/EPCCM_Full_Report.pdf>. Accessed May19, 2013

- 8.Rosenberg CN, Peele P, Keyser D, McAnallen S, Holder D. Results from a patient-centered medical home pilot at UPMC health plan hold lessons for broader adoption of the model. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2423–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rust G, Strothers H, Miller WJ, McLaren S, Moore B, Sambamoorthi U. Economic impact of a Medicaid population health management program. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14(5):215–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes AM, Ackermann RD, Zillich AJ, Katz BP, Downs SM, Inui TS. The net fiscal impact of a chronic disease management program: Indiana Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):855–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson L. CBO: lessons from Medicare's demonstration projects on disease management and care coordination. Available at: <http://www.cbo.gov/publication/42924>. Accessed January30, 2013

- 12.Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1156–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown R. The Promise of Care Coordination: Models that Decrease Hospitalizations and Improve Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries with Chronic Illnesses. Available at: <http://www.nyam.org/social-work-leadership-institute/docs/N3C-Promise-of-Care-Coordination.pdf>. Accessed January31, 2013

- 14.DuBard CA, Cockerham J, Jackson C. Collaborative accountability for care transitions: the community care of North Carolina transitions program. N C Med J. 2012;73(1):34–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steiner BD, Denham AC, Ashkin E, Newton WP, Wroth T, Dobson LA. Community care of North Carolina: improving care through community health networks. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):361–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy D, Mueller K. Community Care of North Carolina: Building Community Systems of Care Through State and Local Partnerships. Available at: <http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Case-Studies/2009/Jun/Community-Care-of-North-Carolina–Building-Community-Systems-of-Care-Through-State-and-Local-Partner.aspx>. Accessed February1, 2013

- 17.Bodenheimer T. North Carolina Medicaid: a fruitful payer-practice collaboration. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):292–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):75–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg DG, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, Love LE, Carver MC. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013:16:150–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVries A. Impact of medical homes on quality, healthcare utilization, and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(9):534–544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stream G. Investments in medical home model starting to pay dividends. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):80–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yee T, Lechner A, Carrier E. High-intensity primary care: lessons for physician and patient engagement. Available at: <http://www.nihcr.org/High-Intensity-Primary-Care#>. Accessed January30, 2013

- 25.Berry-Millett R, Bodenheimer TS. Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Synth Proj Res Synth Rep. 2009;(19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):427–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorr DA, Wilcox A, Burns L, Brunker CP, Narus SP, Clayton PD. Implementing a multidisease chronic care model in primary care using people and technology. Dis Manag. 2006;9:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rich EC, Lipson D, Libersky J, Peikes DN, Parchman ML. Organizing care for complex patients in the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):60–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American medical home runs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1317–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Tusler M. Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient's level of activation. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):353–360 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Community Care of North Carolina. Our results. Available at: <https://www.communitycarenc.org/our-results/>. Accessed December10, 2012

- 32.Wells AR, Hamar B, Bradley C, et al. Exploring robust methods for evaluating treatment and comparison groups in chronic care management programs. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:35–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fetterolf D, Wennberg D, Devries A. Estimating the return on investment in disease management programs using a pre–post analysis. Dis Manag. 2004;7:5–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Educ Behav Stat. 1998;23(4):323–355 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy SM, McGready J, Griswold ME, Sylvia ML. A method for estimating cost savings for population health management programs. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(pt 1):582–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortune-Greely AK, Greene SB. CCNC program evaluation: strategies and challenges. N C Med J. 2009;70(3):277–279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SAS Institute. SAS/STAT 9.2 User's Guide. 2nd ed. Available at: <http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#titlepage.htm>. Accessed January31, 2013

- 38.Hughes JS, Averill RF, Jon Eisenhandler, et al. Clinical risk groups (CRGs): a classification system for risk-adjusted capitation-based payment and health care management. Med Care. 2004;42(1):81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iacus SM, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis. 2011;20(1):1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iacus SM, King G, Porro G. Multivariate matching methods that are monotonic imbalance bounding. J Am Statist Assoc. 2011;106(493):345–361 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trochim WMK. Outcome pattern matching and program theory. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12(4):355–366 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trochim WMK. Pattern matching, validity, and conceptualization in program evaluation. Evaluation Rev. 1985;9(5):575–604 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markovich P. A global budget pilot project among provider partners and Blue Shield of California led to savings in first two years. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(9):1969–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. The ‘alternative quality contract,’ based on a global budget, lowered medical spending and improved quality. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1885–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. Health care spending and quality in year 1 of the alternative quality contract. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):909–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DuBard CA. Improving quality of care for Medicaid patients with chronic diseases: community care of North Carolina. N C Med J. 2013;74(2):142–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis A. Questioning the widely publicized savings reported for North Carolina Medicaid. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(8):e277–e279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cosway R. Questioning the widely publicized savings. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(1):68–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobson LA., Jr Questioning the widely publicized savings. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(1):69–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson CT, Trygstad TK, DeWalt DA, DuBard CA. Transitional care cut hospital readmissions for North Carolina Medicaid patients with complex chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1407–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]