The major role of BRCA1 in meiosis is not in meiotic recombination but instead in promotion of the dramatic chromatin changes required for formation and function of the XY body.

Abstract

During meiosis, DNA damage response (DDR) proteins induce transcriptional silencing of unsynapsed chromatin, including the constitutively unsynapsed XY chromosomes in males. DDR proteins are also implicated in double strand break repair during meiotic recombination. Here, we address the function of the breast cancer susceptibility gene Brca1 in meiotic silencing and recombination in mice. Unlike in somatic cells, in which homologous recombination defects of Brca1 mutants are rescued by 53bp1 deletion, the absence of 53BP1 did not rescue the meiotic failure seen in Brca1 mutant males. Further, BRCA1 promotes amplification and spreading of DDR components, including ATR and TOPBP1, along XY chromosome axes and promotes establishment of pericentric heterochromatin on the X chromosome. We propose that BRCA1-dependent establishment of X-pericentric heterochromatin is critical for XY body morphogenesis and subsequent meiotic progression. In contrast, BRCA1 plays a relatively minor role in meiotic recombination, and female Brca1 mutants are fertile. We infer that the major meiotic role of BRCA1 is to promote the dramatic chromatin changes required for formation and function of the XY body.

Introduction

DNA damage response (DDR) pathways recognize harmful DNA damage and are essential for the activation of cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair mechanisms that maintain the integrity of the genome (Ciccia and Elledge, 2010; Polo and Jackson, 2011). DDR/checkpoint proteins also have an essential role during meiosis, when homologous chromosomes undergo recombination and synapsis to generate haploid gametes. In mammals, DDR proteins recognize and transcriptionally silence unsynapsed chromosomes in a general process known as meiotic silencing of unsynapsed chromatin (Baarends et al., 2005; Turner et al., 2005). In normal male meiosis, meiotic silencing is confined to unsynapsed X and Y chromosomes in a process called meiotic sex chromosome inactivation (MSCI), an essential step for meiotic progression (Turner, 2007; Ichijima et al., 2012). As part of MSCI, DDR proteins and subsequent epigenetic modifications are synchronously established on the sex chromosomes at subsequent stages of meiotic prophase (van der Heijden et al., 2007). Therefore, the study of meiotic sex chromosomes dissects not only essential processes in meiosis but also serves as a model to uncover how DDR proteins are coordinated and how chromatin changes and epigenetic modifications are regulated (Sin et al., 2012).

Mice harboring a knockout of histone variant H2AX fail to undergo MSCI, suggesting that phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX), a prominent marker of inactive sex chromosomes in meiosis, is important for successful MSCI (Fernandez-Capetillo et al., 2003). We have previously shown that MDC1, a binding partner of γH2AX, directs chromosome-wide spreading of γH2AX and initiation of MSCI (Ichijima et al., 2011). Curiously, in MDC1 mutant mice, DDR proteins such as ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related) and TOPBP1 (DNA topoisomerase 2 binding protein 1) accumulated on unsynapsed chromosome axes, suggesting that axial recognition is independent of MDC1. It remains unclear how these DDR proteins accumulate on unsynapsed chromosome axes before MDC1-dependent chromosome-wide spreading of γH2AX.

BRCA1, the product of the breast cancer susceptibility gene 1, accumulates on unsynapsed axes of the sex chromosomes (Scully et al., 1997) and is proposed to recruit the ATR kinase to phosphorylate H2AX on unsynapsed chromosomes (Turner et al., 2004). BRCA1 could therefore have a role in the recognition of unsynapsed axes. In this context, it should be noted that in somatic cells BRCA1 functions primarily to repair DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by homologous recombination (HR; Moynahan et al., 1999). BRCA1 has also been suggested to have a potential role in repairing DSBs during meiotic recombination (Xu et al., 2003). Thus, it is widely held that defective meiotic DSB repair may cause failure of meiotic silencing, the expression of toxic genes from the sex chromosomes, and apoptotic elimination of spermatocytes at the mid-pachytene stage (Royo et al., 2010). However, the alternative possibility remains that BRCA1 has a direct role in MSCI that is distinct from its potential role in meiotic recombination.

In this study, our genetic experiments define the roles of BRCA1 in MSCI and meiotic recombination. Our results demonstrate that the function of BRCA1 in MSCI is distinct from its role in recombination-associated repair of DSBs. Additionally, although BRCA1 deficiency has a large impact on MSCI, the effect on meiotic recombination is minor. Consistently, BRCA1 is not required for meiotic recombination in female meiosis. However, BRCA1 has a clear role in MSCI in males, including the establishment of DDR signals along unsynapsed XY axes and the establishment of the pericentric heterochromatin (PCH) of the X chromosome.

Results

The male meiotic phenotype of Brca1 deletion is not rescued by 53bp1 deletion

In previous studies of meiosis, the embryonic lethality of mice with a deletion of Brca1 exon 11 (Brca1Δ/Δ), which produces a functionally compromised and truncated form of BRCA1, was rescued by heterozygosity for Trp53 deletion (Xu et al., 2003). Because the Trp53 (also known as p53) network is activated during meiosis (W.J. Lu et al., 2010), it is important to evaluate the function of BRCA1 in a Trp53+/+ background without the potential effect of Trp53 heterozygosity. To test the role of BRCA1 in directing the DDR pathway during MSCI, we used the Cre/LoxP system with Ddx4 (also known as mouse Vasa homologue)-cre to generate a conditional, germline-specific deletion of Brca1 exon 11 (Brca1cKO).

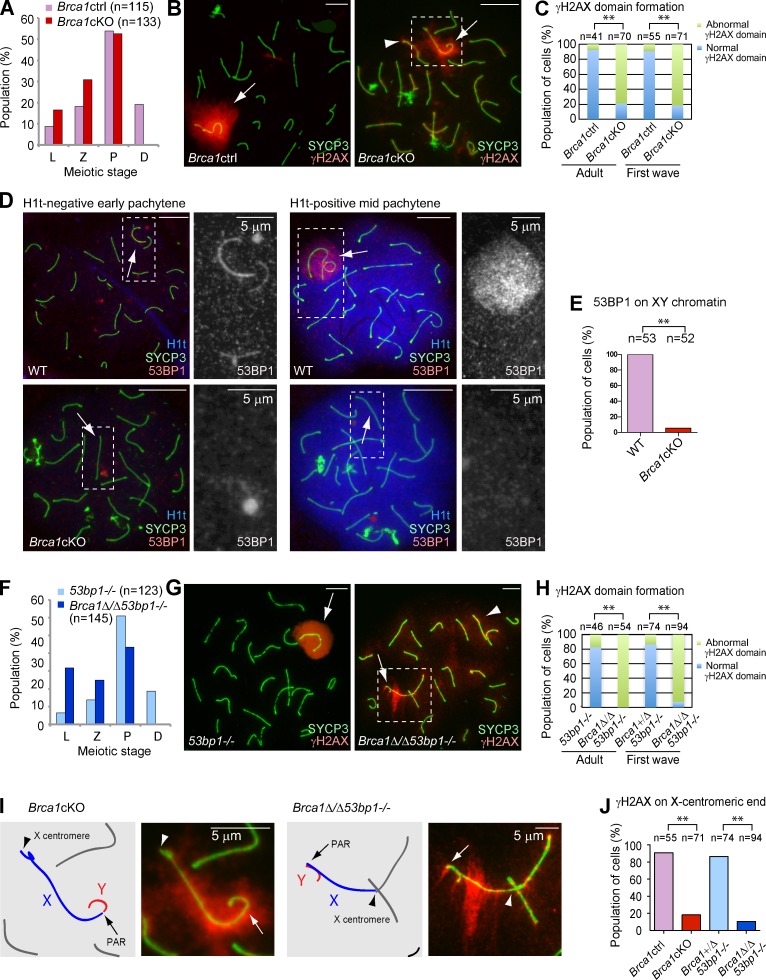

The high efficiency of deletion of exon 11 of Brca1 (98.2% of first wave spermatocytes that occur in juvenile testes: n = 57; 95.2% of adult spermatocytes: n = 124) was confirmed using immunofluorescence microscopy with an antibody raised against amino acids 789–1,141 of BRCA1 (encoded by exon 11; Fig. S1; Ichijima et al., 2011). We found that Brca1cKO spermatocytes are arrested and eliminated by apoptosis after the mid-pachytene stage, as judged by the presence of the testis-specific linker histone H1t (Fig. S1). In both first wave and adult Brca1cKO spermatocytes, normal formation of a chromosome-wide γH2AX domain on the sex chromosomes was severely disrupted during the pachytene stage in comparison to those of control littermates (termed Brca1ctrl; see Materials and methods; Fig. 1, B and C). We found that 21.4% of Brca1cKO spermatocytes showed normal γH2AX domain formation on the sex chromosomes. However, ectopic γH2AX foci (foci detected on synapsed autosome regions) were observed regardless of normal or abnormal γH2AX domain formation on the sex chromosomes in the Brca1cKO (Fig. S1). Therefore, we conclude that the conditional deletion of Brca1 exon 11 in a Trp53+/+ background is sufficient to disturb γH2AX signaling during meiotic prophase.

Figure 1.

The meiotic phenotype of BRCA1 is not rescued by deletion of 53BP1. (A and F) Population distribution of spermatocytes. L, leptotene; Z, zygotene; P, pachytene; D, diplotene. (B and G) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-SYCP3 and -γH2AX antibodies. Arrows indicate the sex chromosomes. Arrowheads indicate ectopic γH2AX signals on autosomes. (C and H) Population distribution of pachytene spermatocytes exhibiting normal and abnormal γH2AX domain formation. Normal γH2AX domain formation was characterized as a large, compacted γH2AX-rich region, encompassing the entirety of the XY axes and excluding autosomal interactions. (D) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-53BP1 and -SYCP3 antibodies. H1t-negative early pachytene spermatocytes and H1t-positive mid-pachytene spermatocytes are shown. Arrows indicate the sex chromosomes. Regions inside of the dotted squares are magnified in the right panels. (E) Percentage of mid-pachytene spermatocytes with 53BP1 signal on XY chromatin. (I) Magnified images of the regions inside of the dotted squares in B and G. Schematics of the chromosome axes are shown in the left panels. Arrows indicate PAR. Arrowheads indicate the X centromere. (J) Percentage of cells with γH2AX on the X centromere. P-values were derived from an unpaired t test. **, P < 0.001. Bars, 10 µm (unless otherwise indicated).

In somatic cells, BRCA1 functions to maintain genomic stability through a role in the repair of chromosomal DSBs by HR (Moynahan et al., 1999). HR-deficient cells are forced to rely on nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). The DDR protein 53BP1 promotes NHEJ while simultaneously suppressing HR. In contrast, it has been proposed that a key function of BRCA1 is to remove end-joining proteins, such as 53BP1, from replication-associated breaks (Bouwman et al., 2010; Bunting et al., 2010). As such, we examined the effects of Brca1 deletion in the regulation of 53BP1 during meiosis. A previous study using tissue sections showed that 53BP1 is absent in meiotic cells ranging from the leptotene stage to the early pachytene stage, and then begins to accumulate on the sex chromosomes in the mid-pachytene stage (Ahmed et al., 2007). Our study, using chromosome spreads, demonstrates that in wild-type spermatocytes 53BP1 localizes on the axes of the sex chromosomes in H1t-negative early pachytene cells and on the entire domain of the sex chromosomes in 100% of H1t-positive mid-pachytene cells (Fig. 1, D and E). Interestingly, 53BP1 localization was largely abolished on the sex chromosomes in the Brca1cKO spermatocytes (Fig. 1, D and E). These results suggest that BRCA1 regulates the localization of 53BP1 during meiosis. In contrast to the function of BRCA1 in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in somatic cells (Bunting et al., 2012), BRCA1 does not regulate another NHEJ factor (Ku) during meiosis (Fig. S1).

Because 53bp1 deletion rescues embryonic lethality of Brca1 mutants and phenotypes related to defects in somatic HR (Bouwman et al., 2010; Bunting et al., 2010, 2012), we sought to determine whether 53bp1 deletion rescues meiotic defects caused by deletion of Brca1 exon 11. Consistent with the fecundity of 53bp1−/− males (Ward et al., 2003), we observed normal γH2AX domain formation in 53bp1−/− pachytene stage spermatocytes (Fig. 1, F and G). In contrast with the rescue of Brca1 mutant phenotypes in somatic HR by deletion of 53bp1, we observed a more severe meiotic phenotype in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice than that of Brca1cKO mice. First, we found an increase in the number of leptotene stage spermatocytes and a decrease in the number of pachytene stage spermatocytes (Fig. 1 F). Second, we found that γH2AX domain formation was largely disrupted in pachytene stage spermatocytes in adult and juvenile Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice (Fig. 1 H). These results suggest that 53BP1 functions in meiosis when full-length BRCA1 is absent. Unexpectedly, we found that γH2AX signals were largely depleted from the X-centromeric end and its surrounding pericentric region, both in Brca1cKO and Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− spermatocytes (Fig. 1, I and J). We rarely observed γH2AX signals on the X-centromeric end when compared with other areas of the sex chromosomes (Fig. S1), suggesting that BRCA1 regulates the X-pericentric region in meiosis.

BRCA1 amplifies DDR signals on unsynapsed axes

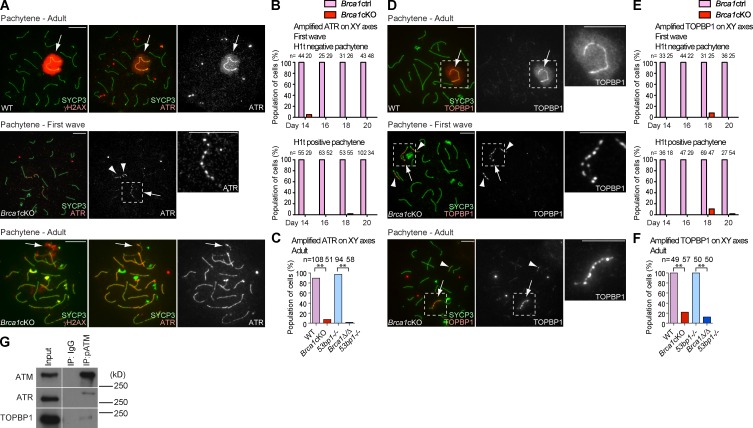

To further understand the role of BRCA1 on unsynapsed axes, we examined the localization of the ATR kinase, which is believed to function with BRCA1 and mediate γH2AX domain formation in MSCI (Turner et al., 2004; Bellani et al., 2005; Royo et al., 2013). In normal meiosis, ATR accumulates on the unsynapsed XY axes and spreads onto the chromosome-wide domain (Fig. 2 A). In contrast, ATR signals were punctate and were not amplified along the length of the XY axes in early to mid-pachytene stage spermatocytes of both first wave and adult meiosis of the Brca1 mutants (Fig. 2, A–C). In particular, ectopic, punctate ATR signals accumulated on the autosomal axes in first wave meiosis in the Brca1cKO. During adult meiosis, ectopic AT R accumulation occurred on the entire length of autosomal axes in the Brca1cKO, whereas accumulation of ATR along autosomal axes was not observed during first wave meiosis (Figs. 2 A and S2).

Figure 2.

BRCA1 amplifies ATR and TOPBP1 on unsynapsed sex chromosomes. (A) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads of adult meiosis using anti-SYCP3, -γH2AX, and -ATR antibodies. (B and C) Percentage of pachytene spermatocytes exhibiting amplified ATR accumulation in first wave meiosis (B) and adult meiosis (C). (D) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-SYCP3 and -TOPBP1 antibodies. (E and F) Percentage of pachytene spermatocytes exhibiting amplified TOPBP1 accumulation in first wave meiosis (E) and adult meiosis (F). (G) Immunoprecipitation using the anti–phospho-ATM antibody, followed by detection of coimmunoprecipitation using ATM, ATR, and TOPBP1 antibodies. 10-fold more material was used in the immunoprecipitation than is present in the input. The migration of the nearest protein molecular mass size markers are shown. Images in the same row are from different parts of the same gel. Arrows indicate sex chromosomes. Arrowheads indicate ectopic foci on autosomes. P-values were derived from an unpaired t test. **, P < 0.001. Bars, 10 µm.

Next, we investigated the localization of an activator of ATR, TOPBP1, which colocalizes with ATR during normal meiosis (Perera et al., 2004). In both first wave and adult meiosis, amplification of TOPBP1 along the entire length of XY axes is dependent on BRCA1 (Fig. 2, D–F), and ectopic TOPBP1 signals on autosome axes were observed in the Brca1 mutants (Figs. 2 D and S2). These results suggest that ATR and TOPBP1 are able to recognize unsynapsed XY axes and accumulate in a punctate manner independent of BRCA1, though BRCA1 assists in the effective amplification of ATR and TOPBP1 along XY axes in meiosis.

Although ATR has a major role in phosphorylation of H2AX during MSCI (Royo et al., 2013), a potential role for ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated), which is involved in meiotic DSB processing (Lange et al., 2011), has not been excluded. Thus, we examined the localization of a phosphorylated and activated form of ATM (referred to as phospho-ATM hereafter; Bakkenist and Kastan, 2003). Two independent anti–phospho-ATM monoclonal antibodies demonstrated localization patterns very similar to that of TOPBP1, and phospho-ATM and ATR localize to identical sites along the X axis in Brca1cKO spermatocytes (Fig. S3). Furthermore, our immunoprecipitation experiments suggest that phospho-ATM interacts with both ATR and TOPBP1 in adult testes (Fig. 2 G). In this experiment, ATR detected in phospho-ATM immunoprecipitates has a slightly higher molecular mass when compared with the major portion of ATR detected in the input, suggesting that there is an interaction of phospho-ATM with posttranslationally modified ATR.

A majority of cells completed autosomal synapsis, but at least one area of autosomal asynapsis was frequently observed in Brca1 mutants (Fig. S4). Because ATR and TOPBP1 localize to unsynapsed autosomal axes for meiotic silencing of unsynapsed chromatin (Turner et al., 2005), ectopic autosomal foci of these DDR factors may be partly associated with the presence of autosomal asynapsis.

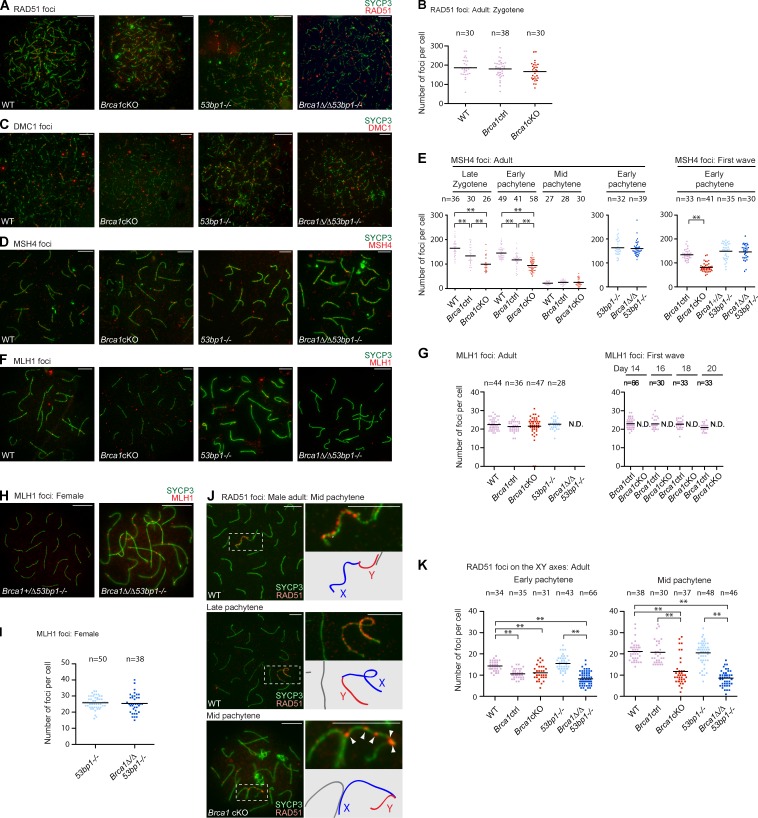

Brca1 mutation causes minor perturbations in meiotic recombination

To distinguish the role of BRCA1 in meiotic silencing from its potential role in DSB repair during meiotic recombination, we examined the localization of four factors that are involved in various steps of meiotic recombination: RAD51 and DMC1, RecA homologues that mediate homology recognition and strand invasion (Bishop et al., 1992; Pittman et al., 1998; Yoshida et al., 1998); MSH4, a meiosis-specific MutS homologue that promotes crossover formation, present in the late zygotene and pachytene stages (Kneitz et al., 2000); and MLH1, a MutL homologue that marks one or two crossover sites per chromosome during the pachytene stage (Edelmann et al., 1996). In contrast with a previous study showing that BRCA1 is required for RAD51 loading to sites of meiotic DSBs (Xu et al., 2003), RAD51 accumulated normally at sites of DSBs in the leptotene and zygotene stages of Brca1 mutants, as in the wild type (Fig. 3, A and B). We also found normal accumulation of DMC1 foci in Brca1 mutants (Fig. 3 C) and we did not see any significant difference in the removal of RAD51 and DMC1 foci from synapsed autosomes in the Brca1 mutants versus controls (unpublished data). These results suggest that BRCA1 does not regulate the assembly or removal of RAD51 and DMC1 foci and are consistent with the efficient homologue pairing and synapsis observed in Brca1 mutants.

Figure 3.

BRCA1 deficiency has a modest impact on meiotic recombination. (A, C, D, and F) Immunostaining of adult meiotic chromosome spreads using the antibodies shown in the panels. (B) Number of RAD51 foci per each zygotene spermatocyte of each genotype. (E) Number of MSH4 foci per each spermatocyte of each genotype. (G) Number of MLH1 foci per each mid-pachytene spermatocyte of each genotype. (H) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads of female meiosis with anti-MLH1 and -SYCP3 antibodies. (I) Number of MLH1 foci per each mid-pachytene oocyte of each genotype. (J) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-RAD51 and -SYCP3 antibodies. Areas surrounding sex chromosomes (dotted rectangles) are magnified in right panels and schematics of chromosome axes are shown below. Arrowheads indicate unamplified RAD51 foci along the XY axes in Brca1cKO. (K) The number of RAD51 foci along the XY axes is quantified. The mid-pachytene stage was judged by positive staining for H1t. P-values were derived from an unpaired t test. **, P < 0.001. N.D., not detected. Bars, 10 µm.

To determine the role of BRCA1 in the regulation of recombination intermediates, we examined the localization of MSH4. Although MSH4 foci also accumulated in Brca1 mutants (Fig. 3 D), the number of MSH4 foci was statistically reduced during both the first wave and adult meiosis (Fig. 3 E). We observed an intermediate phenotype in heterozygous control littermates, suggesting that the effect is based on the copy number of Brca1. Hence, BRCA1 may regulate efficient formation or stabilization of recombination intermediates. Intriguingly, we did not observe a decrease in the mean number of MSH4 foci in adult Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− nuclei (Fig. 3 E). This suggests that deletion of 53bp1 promotes efficient MSH4 foci formation in the Brca1 mutant background in meiosis.

Finally, we examined the role of BRCA1 in the formation of MLH1 foci, which mark sites of crossovers. In the Brca1cKO, MLH1 foci were present in 95.7% of H1t-positive mid-pachytene spermatocytes (n = 47; Fig. 3, F and G). Among these MLH1-positive cells, the number of MLH1 foci was comparable to those in the wild type (Fig. 3 G). However, MLH1-positive cells were not observed in spermatocytes in juvenile Brca1cKO mice (Fig. 3 G), suggesting that formation of MLH1 foci is delayed. Strikingly, we did not observe MLH1 foci formation in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice (Fig. 3, F and G). Absence of MLH1 foci was also observed previously in Mdc1−/− mice (Ichijima et al., 2011). Although both Brca1Δ/Δ 53bp1−/− and Mdc1−/− spermatocytes reach the H1t-positive mid-pachytene stage, it is conceivable that germ cells are eliminated just before the formation of MLH1 foci. In contrast, female Brca1 mutants are fertile and MLH1 foci formation is normal in Brca1Δ/ΔTrp53+/− mice (Xu et al., 2003) and in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice (Fig. 3, H and I), indicating that BRCA1 is not directly required for DSB repair during meiotic recombination in females. Thus, although BRCA1 is not essential for meiotic recombination, our data suggest a role in the timing of crossover formation, as indicated by decreased numbers of MSH4 foci and the delayed appearance of MLH1 foci.

BRCA1 amplifies RAD51 signals on unsynapsed axes

Consistent with our preceding results that BRCA1 amplifies DDR signaling along XY axes, we noticed that numerous RAD51 foci remained on the unsynapsed XY axes after the removal of RAD51 foci from autosomes in early pachytene spermatocytes. In normal meiosis, during the transition from the early to mid-pachytene stages, RAD51 foci were increased along the axis of the X chromosome, though RAD51 foci did not accumulate on the Y chromosome (Fig. 3, J and K). RAD51 foci then accumulated on both the X and Y axes in late pachytene cells (Fig. 3 J). Although RAD51 foci were present on the X axes of Brca1 mutant spermatocytes, they were punctate and were not amplified in the mid-pachytene stage (Fig. 3 J). These results suggest that BRCA1 aids in the amplification of RAD51 foci along unsynapsed XY axes in meiosis.

Next, we investigated whether other components of unsynapsed axes are amplified by BRCA1. Two HORMA domain proteins, HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, localize on unsynapsed chromosomes and regulate meiotic silencing (Shin et al., 2010; Daniel et al., 2011; Kogo et al., 2012a,b; Wojtasz et al., 2012). HORMAD1 and HORMAD2 uniformly covered the entire length of the unsynapsed XY axes both in Brca1 mutants and in controls (Fig. S4). Although a previous study reported that phosphorylation of HORMAD1 and HORMAD2 is regulated by BRCA1 (Fukuda et al., 2012), our results indicate that the loading of HORMAD1 and HORMAD2 is not regulated by BRCA1.

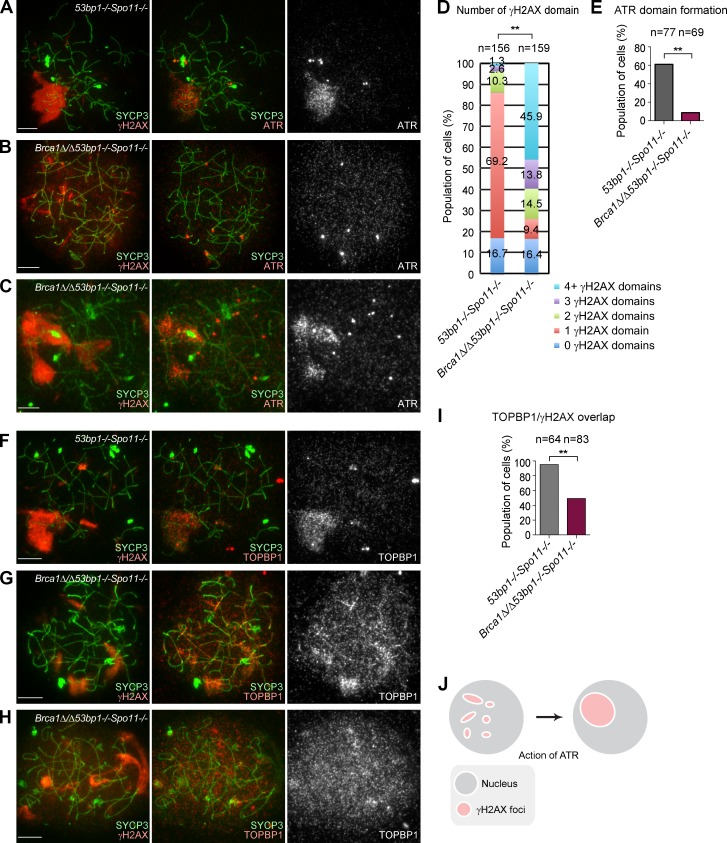

BRCA1 regulates ATR recruitment in meiotic silencing independent of meiotic DSBs

To test the direct role of BRCA1 in meiotic silencing independent of recombination-associated meiotic DSBs mediated by SPO11, we designed a genetic experiment using a Spo11 mutant allele. Meiotic silencing occurs in the absence of SPO11-dependent meiotic DSBs. However, the silent domain localizes ectopically, not specifically to the X and Y chromosomes, and is thus referred to as a pseudo sex body (Barchi et al., 2005; Bellani et al., 2005). In control littermates (53bp1−/−Spo11−/−), we observed the formation of a pseudo sex body possessing a single γH2AX domain in 69.2% of pachytene-like spermatocytes (Fig. 4, A and D). In contrast, the Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− mutant typically displayed multiple γH2AX domains (Fig. 4, B–D). These results suggested that BRCA1 promotes efficient formation of large, consolidated γH2AX domains during meiotic silencing. The formation of a dense ATR domain, which overlaps with the pseudo sex body, was observed in 61.0% of 53bp1−/−Spo11−/− pachytene-like spermatocytes (Fig. 4, A and E). However, in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− spermatocytes, ATR domain formation was largely impaired (Fig. 4, B and E) and occurred in only 8.7% of pachytene-like spermatocytes (Fig. 4, C and E). Thus, we conclude that BRCA1 regulates ATR recruitment in meiotic silencing independent of meiotic DSBs.

Figure 4.

BRCA1 regulates ATR recruitment in meiotic silencing independent of meiotic DSBs. (A–C) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-γH2AX, -ATR, and -SYCP3 antibodies. (D) The percentage of pachytene-like spermatocytes with the indicated number of γH2AX domains. P-values were derived using a χ2 test. **, P < 0.001. (E) The percentage of pachytene-like spermatocytes with formation of ATR domains. (F–H) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-γH2AX, -TOPBP1, and -SYCP3 antibodies. (I) The percentage of pachytene-like spermatocytes with overlap of γH2AX and TOPBP1 overlap in pachytene-like spermatocytes. (J) Model of biogenesis of the pseudo sex body. Maturation of multiple pseudo sex bodies into a single pseudo sex body requires ATR, which acts in a BRCA1-dependent manner. P-values in D, E, and I were derived from an unpaired t test. **, P < 0.001. Bars, 10 µm.

Next, we examined the role of BRCA1 in the recruitment of TOPBP1 and phospho-ATM in the absence of meiotic DSBs. γH2AX domains and TOPBP1 signals overlapped in 95.3% of pachytene-like spermatocytes in 53bp1−/−Spo11−/− mice (Fig. 4, F and I). In contrast, γH2AX domains overlapped with TOPBP1 in only 49.4% of pachytene-like spermatocytes in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− mice (Fig. 4, G and I); however, TOPBP1 showed a diffuse nuclear localization in the remaining samples (Fig. 4 H). Therefore, in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− spermatocytes, TOPBP1 signals overlapped with γH2AX domains more frequently than did ATR signals. Furthermore, we found that phospho-ATM signals never overlapped with γH2AX domains in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− spermatocytes (Fig. S3), suggesting that BRCA1 also regulates phospho-ATM in meiotic silencing independent of meiotic DSBs.

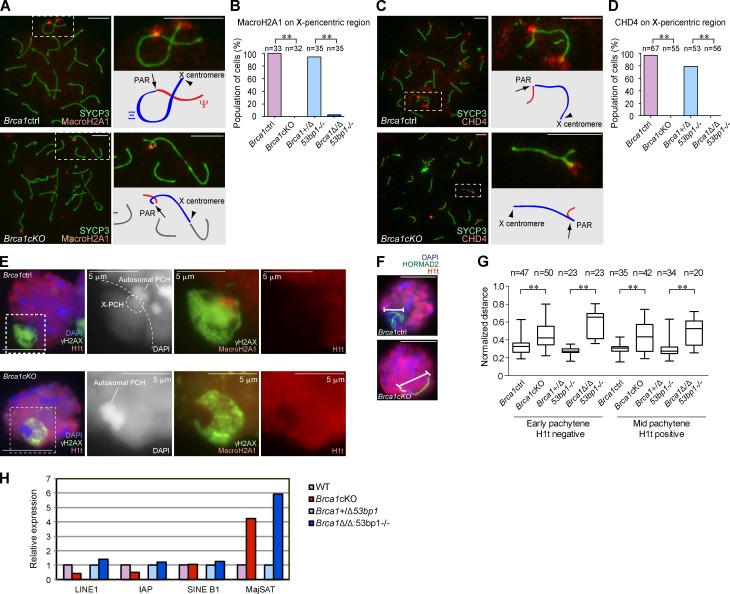

BRCA1 establishes PCH of the X chromosome in male meiosis

To further elucidate the role of BRCA1 in meiotic silencing, we investigated the Brca1 mutants’ phenotype on the sex chromosomes. We observed abnormal γH2AX signals on the X-pericentric region in Brca1 mutants (Fig. 1), which prompted us to examine the distribution of MacroH2A1, a histone variant that specifically accumulates on the X-centromeric end and the pseudoautosomal region (PAR) of meiotic sex chromosomes (Turner et al., 2001). In normal meiosis, MacroH2A1 starts to accumulate on the X-pericentric region and PAR after the mid-pachytene stage (Fig. 5 A) and also accumulates on the Y-pericentric region after the late pachytene stage (not depicted). In Brca1 mutants, MacroH2A1 accumulated on the PAR, but did not localize on the X-pericentric region (Fig. 5, A and B), suggesting that BRCA1 regulates the localization of MacroH2A1 at the X-pericentric region.

Figure 5.

BRCA1 establishes PCH on the X chromosome in male meiosis. (A and C) Immunostaining of meiotic chromosome spreads using anti-SYCP3 and -MacroH2A1 or -CHD4 antibodies. Arrows indicate the PAR. Arrowheads indicate the X centromere. (B and D) Percentage of mid-pachytene spermatocytes with MacroH2A1 or CHD4 on the X-pericentric region. (E) Immunostaining of mid-pachytene spermatocytes using slides that preserve the three-dimensional structure of nuclei. Single Z sections are shown. The regions inside of the dotted squares are shown in the right panels. In the Brca1ctrl, X-PCH is defined by the intensity of DAPI staining and by MacroH2A1 accumulation. The border between the sequestered XY body and the rest of the nucleus is shown in the dotted line. (F) The conformation of sex chromosome axes is detected by HORMAD2 staining in pachytene spermatocytes. (G) Summary of linear distances between the two most distal regions of the chromosomes. Boxes encompass 50% of data points and bars indicate 90% of data points. Meiotic stages were judged by immunostaining using anti-SYCP3 and -H1t antibodies. (H) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of repetitive genomic elements using total RNA from whole testes at postnatal day 14. Expression in the mutants is compared with the controls. The data shown are from a single representative experiment out of three repeats. P-values were derived from an unpaired t test. **, P < 0.001. Bars, 10 µm (unless otherwise indicated).

Because DDR proteins regulate epigenetic modifications on the meiotic sex chromosomes (Ichijima et al., 2011; Sin et al., 2012), we investigated the localization of potential chromatin modifiers that work downstream of the DDR pathway. We found that CHD4, a core component of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation complex and an interacting partner of RNF8 (Luijsterburg et al., 2012), localizes specifically on both the PAR and X-pericentric regions beginning in the early pachytene stage (Fig. 5 C). Whereas CHD4 localized on the PAR in Brca1 mutants, localization on the X-pericentric region was abolished (Fig. 5, C and D).

Pericentric regions are enriched with major satellite repeats and form constitutive heterochromatin called PCH. In somatic cells, BRCA1 recruits heterochromatin proteins to PCH (Zhu et al., 2011). In contrast, in meiosis, localization of heterochromatin proteins (CBX1 and CBX3) on X and autosomal PCH is not obviously compromised in Brca1 mutants (Fig. S5). These results are consistent between adult and first wave meiosis spermatocytes (unpublished data), and therefore suggest that X-PCH is modified with MacroH2A1 and CHD4 in a BRCA1-dependent manner at the onset of the pachytene stage.

Because heterochromatin maintains nuclear architecture and genome integrity (Peng and Karpen, 2008), we next investigated the role of BRCA1 in nuclear architectural organization during meiosis. We examined specialized slides that preserve the relative three-dimensional nuclear architecture of testicular germ cells (Namekawa and Lee, 2011). During the mid-pachytene stage, the sex chromosomes form a distinct nuclear compartment called the XY body (sex body; Fig. 5 E). At this stage, the XY body forms a domain that excludes the testis-specific histone H1t and is thereby distinct from the rest of the nucleus. X-PCH, detected with MacroH2A1 signals and by a slight enrichment of DAPI, is located next to autosomal PCH and is located at the junction between the XY body and the autosomal area. We did not observe the exclusion of H1t from XY bodies in mid-pachytene spermatocytes of Brca1 mutants, although we did observe a γH2AX domain (Fig. 5 E). In these cells, the XY body and X-PCH were not clearly discernible, based on DAPI staining, when compared with normal meiotic cells. These results suggest that proper establishment of X-PCH is associated with proper formation of the XY body. Because all spermatocytes of Brca1 mutants are eliminated at this stage, distinct compartmentalization of the sex chromosomes may be an essential step in meiotic progression.

In accord with the structural defects of XY bodies, we also note that the XY axes were not condensed properly in Brca1 mutants. In both early and mid-pachytene stages of Brca1 mutants, the XY axes were irregularly elongated in comparison to controls, which demonstrated a compacted XY axial conformation (Fig. 5, F and G). Furthermore, in Brca1 mutants, we found that the X-centromeric end tended to associate with autosomes and that there is a significant decrease in the pairing of the X and Y chromosomes in pachytene spermatocytes (Fig. S5). These results suggest that the proper establishment of the X-pericentric region in pachytene spermatocytes is associated with the compaction and stabilization of XY axes.

Consistent with the abnormal regulation of X-PCH, we found that major satellite DNA was highly expressed in testes when BRCA1 was absent (Fig. 5 H). In situ hybridization confirmed that satellite DNA expression in testes was derived from germ cells (Fig. S5). Because small RNA biogenesis is uniquely regulated in germ cells and because defects in the regulation of small RNAs is generally associated with meiotic arrest and germ cell elimination (Saxe and Lin, 2011), we tested whether germ cell–specific derepression of satellite DNA affects small RNA biogenesis. Our small RNA sequencing results revealed that small RNAs derived from long terminal repeats (LTRs) were greatly diminished in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− testes, although the overall level of small RNA was not affected (Fig. S5). These results suggest that satellite DNA and LTRs are potential genomic elements regulated by BRCA1 in meiosis.

Discussion

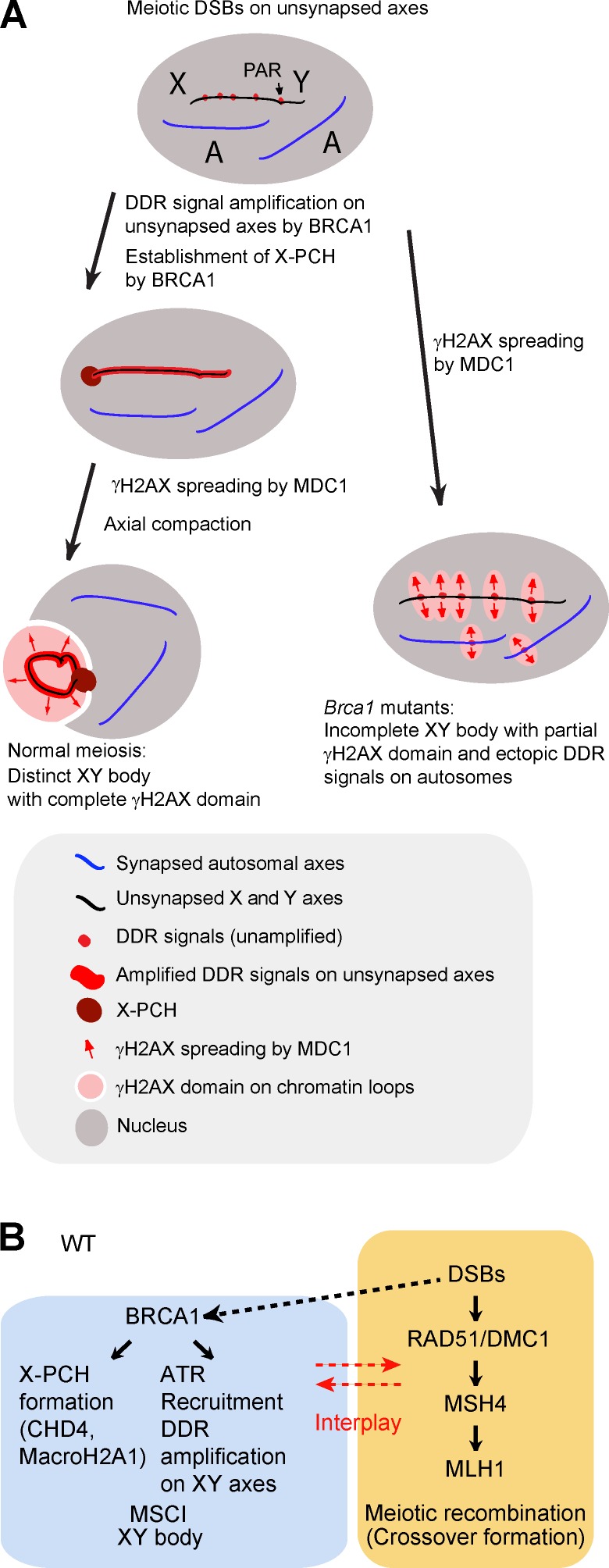

Our study demonstrates that BRCA1 has two major roles in the establishment of MSCI (Fig. 6, A and B). First, in agreement with a previous study concerning BRCA1-dependent recruitment of ATR (Turner et al., 2004), BRCA1 recruits ATR to unsynapsed XY axes and amplifies DDR signals along the axes for the establishment of MSCI. In Brca1 mutants without proper amplification of DDR signals on unsynapsed XY axes, γH2AX partially spreads to the chromosome-wide domain by the action of MDC1, leading to incomplete γH2AX domain formation. Second, BRCA1 is required for the proper establishment of X-PCH. X-PCH defects in Brca1 mutants likely account for abnormal compartmentalization of the XY body (Fig. 6 A). Thus, our results suggest that both the proper establishment of DDR signaling on sex chromosome axes and the establishment of X-PCH is required for chromatin compaction and for proper formation of the XY body.

Figure 6.

Model of the role of BRCA1 in meiosis. (A) Model of BRCA1-dependent amplification of DDR signals along the entirety of the XY axes and BRCA1-dependent formation of X-PCH. (B) Model of two distinct DDR pathways in meiotic silencing and meiotic recombination. In the wild type (WT), BRCA1 promotes ATR recruitment and DDR signal amplification on unsynapsed XY axes and suppresses ATR signals on synapsed autosomes. A dotted line indicates a possible effect of DSBs in meiotic silencing. BRCA1 is not directly required for meiotic recombination. There is some degree of interplay between these two pathways.

BRCA1 is a multifunctional protein that regulates the maintenance of genome integrity by the DDR in somatic cells (Huen et al., 2010). 53BP1 functions at the intersection of two major DSB repair pathways in somatic cells by promoting NHEJ and inhibiting homology-directed repair. Notably, 53bp1 deletion rescues defects associated with Brca1 mutants (Bouwman et al., 2010; Bunting et al., 2010, 2012). In the current study, many aspects of meiotic defects in Brca1 mutants were not rescued by 53BP1 deletion, supporting the notion that the primary cause of meiotic defects in Brca1 mutants is not defective DSB repair during meiotic recombination. Consistent with this possibility, we demonstrate that RAD51 and downstream factors MSH4 and MLH1 are present during meiotic recombination in the Brca1cKO, although the formation of MSH4 foci is less efficient and the formation of MLH1 foci is delayed. These results strongly suggest that BRCA1 deficiency has a modest impact on DSB repair in meiotic recombination in males. Even more striking, female Brca1 mutants are fertile (Xu et al., 2003; Bunting et al., 2012) and BRCA1 is not required for DSB repair during meiotic recombination in females. Therefore, we propose that the DDR pathway for DSB repair in meiotic recombination is distinct from that used for meiotic silencing (Fig. 6 B). The role of BRCA1 in meiotic silencing is consistent with the fact that MDC1 and RNF8, which function in a pathway with BRCA1 in somatic cells, are required for the regulation of sex chromosomes but not generally for meiotic recombination (L.Y. Lu et al., 2010; Ichijima et al., 2011; Sin et al., 2012).

Our genetic analysis using a deleted Spo11 allele indicates that BRCA1 facilitates ATR recruitment and that the amplification of DDR signals is independent of meiotic DSBs. Importantly, although rarely observed, ATR accumulation correlated with the presence of a large γH2AX domain in Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− spermatocytes (Fig. 4 C). Thus, it is conceivable that ATR promotes the assembly of discrete γH2AX domains into the large γH2AX domain during meiotic silencing, leading to the formation of pseudo sex bodies in the Spo11 mutant background (Fig. 4 J). Although these results suggest that meiotic recombination and meiotic silencing are distinctly regulated, the events may share components, including ATM and RAD51. Both of these proteins are involved in meiotic recombination, but are also regulated by BRCA1 on the axes of sex chromosomes.

Although BRCA1 amplifies DDR signals on unsynapsed XY axes, localization of the meiosis-specific proteins HORMAD1 and HORMAD2 on unsynapsed XY axes is not regulated by BRCA1 (Fig. S4). In one study, BRCA1 loading to the unsynapsed XY was inferred to be limited in Hormad2−/− mice (Wojtasz et al., 2012). However, in another study, loading was not limited (Kogo et al., 2012a). It is possible that both HORMAD1/2 proteins and BRCA1 work independently to establish DDR signals on unsynapsed XY axes. Consistent with this notion, both HORMAD1/2 proteins and BRCA1 are required for proper ATR signaling and completion of the γH2AX domain formation on the sex chromosomes.

How does BRCA1 amplify DDR signals on unsynapsed axes? BRCA1 forms several distinct complexes in vivo (Huen et al., 2010), and one of these distinct BRCA1 complexes could be involved in signal amplification along unsynapsed XY axes. Among the various BRCA1 complexes, one complex includes RAD51, which is involved in HR-mediated repair in somatic cells (Dong et al., 2003; Sy et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009a,b, 2012). Also, BRCA1 forms at least one complex for DNA replication and S phase progression (Greenberg et al., 2006). Interestingly, a recent study suggests that one of the BRCA1 complexes, termed the BRCA1-A complex, is involved in the regulation of meiotic sex chromosomes (Lu et al., 2013).

Notably, there are some parallels in the regulation of DDR proteins between meiotic silencing and the somatic DDR. First, BRCA1 is required for activation of both ATR and ATM in the somatic DDR (Foray et al., 2003; Kitagawa et al., 2004). Similarly, in meiotic silencing, BRCA1 regulates signal amplification of ATR, TOPBP1, and phospho-ATM along the unsynapsed axes (Figs. 2 and S3). ATM may participate in γH2AX formation on unsynapsed sex chromosomes, whereas ATR signaling has a more important role and is required for successful establishment of DDR signals on the sex chromosomes (Royo et al., 2013). Because MSCI occurs in ATM mutants with heterozygosity for Spo11 deletion (Bellani et al., 2005), ATR might compensate for the loss of function of ATM. A second parallel is that although TOPBP1 activates ATR in the somatic DDR, TOPBP1 and ATR are recruited by different mechanisms (Cimprich and Cortez, 2008). In meiotic silencing, recruitment of TOPBP1 is also regulated differently from that of ATR on the XY axes (Fig. 2) and on the pseudo sex body (Fig. 4). Finally, BRCA1 promotes RAD51 foci formation during the somatic DDR (Bhattacharyya et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2012), as is the case with the meiotic sex chromosomes (Fig. 3). Because RAD51 is a single-stranded DNA binding protein that can be loaded to sites of single-stranded DNA independent of DSBs during the somatic DDR (Tarsounas et al., 2003), it is possible that RAD51 is similarly loaded to single-stranded DNA regions of unsynapsed sex chromosomes during meiosis.

Because BRCA1-independent RAD51 foci likely persist at previous sites of SPO11-dependent DSBs, DSBs may serve as landmarks to locate meiotic silencing on unsynapsed sex chromosomes. Furthermore, a recent study suggests that persistent DSBs may even serve as a trigger of meiotic silencing (Carofiglio et al., 2013). Of note, in a yeast study, DSBs persisted on chromosomes that lacked the homology necessary for DSB repair by HR, and chromosome-wide amplification of RAD51 was observed (Kalocsay et al., 2009). Therefore, it is possible that persistent DSBs serve as an evolutionarily conserved cue for chromosome-wide amplification of DDR factors. Furthermore, Carofiglio et al. (2013) revealed the existence of SPO11-independent DSBs in meiotic prophase, which potentially serves as the trigger of pseudo sex body formation in a Spo11 mutant background. In agreement with this, ATR and TOPBP1 signals were present in meiosis in the Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− mutant. Therefore, SPO11-independent DSBs are a potential cause of meiotic silencing upstream of BRCA1.

We demonstrate that X-PCH is specifically modified by the action of BRCA1, and we identified accumulation of MacroH2A1 and CHD4 as downstream events that are dependent on BRCA1. In the somatic DDR, MacroH2A1 and the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylation complex, including CHD4, are assembled at sites of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and establish repressive chromatin (Lukas et al., 2011). It is conceivable that poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, MacroH2A1, and CHD4 are established on X-PCH downstream of recombination-associated DSBs in a BRCA1-dependent manner. ATM may be a candidate factor because it is responsible for phosphorylating CHD4 to maintain genome integrity (Urquhart et al., 2011).

Our results also reveal the importance of X-PCH in the establishment of a proper XY body. In normal meiosis, the area of sex chromosomes is distinct from the rest of the nucleus, and all DDR proteins are sequestered and confined to the XY body. X-PCH is located at the junction between the XY body and the rest of the nucleus. The structural establishment of the XY body and sequestration of DDR proteins could serve to prevent the induction of meiotic arrest via checkpoint activation and might thereby promote normal meiotic progression.

Finally, our results implicate satellite DNA and LTRs as potential targets of BRCA1 regulation in meiosis. Promising questions include the following: (a) How are synapsed and unsynapsed chromosomes recognized and targeted by DDR pathways? (b) Do DDR pathways in meiosis specifically target satellite DNA and LTRs? (c) Is it possible that BRCA1 maintains the integrity of retrotransposons by suppressing their expression through small RNAs in meiosis? Because small RNAs are able to suppress long transcripts, from which the small RNAs are originally derived, reduction of LTR-derived small RNAs in Brca1 mutants could be associated with the instability of LTRs. It would be intriguing to examine the function of these specific genomic elements at the onset of MSCI.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mice with the floxed allele of Brca1 exon 11 (Xu et al., 1999) were obtained from the National Cancer Institute mouse repository. Ddx4-cre transgenic mice (Gallardo et al., 2007) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Because the Ddx4-cre allele needs to be transmitted from the paternal allele to generate mice with a germline-specific conditional deletion, males with Brca1+/ΔDdx4-cre were mated with females homozygous for the floxed allele of Brca1 exon 11 (Brca1F/F), and the conditional deletion model Brca1F/ΔDdx4-cre (Brca1cKO) was obtained. We used littermates of Brca1+/FDdx4-cre as controls (Brca1ctrl). Because this breeding scheme does not generate wild-type controls, we used C57BL/6 wild-type mice as controls when necessary. The 53bp1−/− mice (the exon spanning nucleotides 3,777 to 4,048 of the mouse 53BP1 cDNA was replaced with the PGK-neor gene to nullify 53BP1; Ward et al., 2003) and the Spo11−/− mice (most of exon 1 and part of intron 1 of Spo11 gene were removed to nullify Spo11; Romanienko and Camerini-Otero, 2000) were used to generate Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice and Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/−Spo11−/− mice, respectively. All mice used in this study, except C57BL/6 wild-type controls, were on a mixed background.

Spermatogenesis slide preparation

Meiotic chromosome spreads were prepared using hypotonic treatment, as described previously (Peters et al., 1997). In brief, testicular tubules were incubated in hypotonic extraction buffer (30 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, 50 mM sucrose, 17 mM trisodium citrate dihydrate, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, pH 8.2) for 30 min, torn to pieces in 100 mM sucrose, and spread onto slides pretreated with the fixation solution (2% paraformaldehyde, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 0.02% sodium monododecyl sulfate, pH 9.2). To conserve the morphology of meiotic chromatin, specialized slides that preserve the relative three-dimensional nuclear architecture of testicular germ cells were prepared as described previously (Namekawa et al., 2006; Namekawa and Lee, 2011; Namekawa, 2014). In brief, the permeabilization step and subsequent fixation step were performed directly on seminiferous tubules and were followed by the mechanical dissociation of germ cells with forceps before cytospinning onto slides. For these slide preparations, mutants and littermate controls were processed between 40 to 80 d postpartum. The first wave of meiosis was examined using testes from juvenile mice. Brca1 mutants and their littermates were examined at days 14, 16, 18, and 20 after birth for the analysis of the Brca1cKO and at day 16 for the analysis of Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice. TUNEL assay was performed on paraffin sections using the In Situ Cell Death (Apoptosis) Detection kit (Fluorescein; Roche).

Immunofluorescence microscopy of spermatogenesis

Slides were incubated in PBT (0.15% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS) for 60 min before overnight incubation at RT with the following antibodies: mouse anti-SYCP3 (Abcam), 1:5,000; mouse anti-γH2AX (EMD Millipore), 1:5,000; rabbit anti-BRCA1 (Ichijima et al., 2011), 1:1,500; rabbit anti-MacroH2A1 (EMD Millipore), 1:200; rabbit anti-CHD4 (Active Motif), 1:100; rabbit anti-ATR (Cell Signaling Technology; for Figs. 2, 4, S2, and S3), 1:50; rabbit anti-TOPBP1 (gift from J. Chen, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX), 1:500; mouse anti–phospho-ATM pS1981 (#200-301-400; Rockland), 1:500; mouse anti–phospho-ATM pS1981 (#200-301-500; Rockland), 1:100; rabbit anti-SYCP1 (Abcam), 1:1500; rabbit anti-RAD51 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), 1:100; rabbit anti-DMC1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), 1:100; rabbit anti-MSH4 (Abcam), 1:200; rabbit anti-MLH1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), 1:100; rabbit anti-53BP1 (Novus Biologicals), 1:100; rabbit anti-Ku80 (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:400; rabbit anti-HORMAD1 (gift from A. Toth, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany; Wojtasz et al., 2009), 1:300; rabbit anti-HORMAD2 (gift from A. Toth; Wojtasz et al., 2009), 1:500; guinea pig anti-H1t (gift from M.A. Handel, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; Inselman et al., 2003), 1:500; rabbit anti-CBX1 (Abcam), 1:200; and mouse anti-CBX3 (EMD Millipore), 1:500. Thereafter, slides were washed three times for 5 min each in PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20, incubated with secondary antibodies (Invitrogen or Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) at 1:500 for 60 min in PBT, washed in PBS plus 0.1% Tween 20, and mounted in Vectashield with DAPI. Details of immunofluorescence microscopy are described elsewhere (Namekawa and Lee, 2011). In brief, slides were blocked in PBT (0.15% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS) for 30 min, incubated with primary antibodies in PBT at RT overnight, washed in 0.1% Tween 20, washed in PBS for 5 min three times at RT, incubated with second antibodies in PBT at RT for 1 h, washed in 0.1% Tween 20, washed in PBS RT for 5 min three times at RT, and mounted with DAPI in vectashield; slides were stored at 4°C.

Microscopy and image analyses

Images of germ cells were acquired with one of two microscope systems: (1) A TE2000-E microscope (Nikon) and CoolSNAPHQ camera (Photometrics), with 60× and 100× Apochromat oil immersion lenses (Nikon), numerical aperture 1.40; image acquisition was performed using Phylum software (PerkinElmer); (2) an ECLIPSE Ti-E microscope (Nikon) and Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera (Andor Technology), with 60× and 100× CFI Apochromat TIRF oil immersion lenses (Nikon), numerical aperture 1.40; image acquisition was performed using NIS-Elements Basic Research software (Nikon). Images were taken at RT (∼22°C). Phylum, Volocity 3D Image Analysis (PerkinElmer), NIS-Elements Basic Research, NIS-Elements Viewer (Nikon), and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) were used for image analysis. Photoshop and Illustrator (Adobe) were used for composing figures. Particular stages of primary spermatocytes were determined by staining for SYCP3 and H1t. XY axes were distinguished by SYCP3 staining if γH2AX was severely disrupted. For data analysis, the matched substage of meiosis was analyzed in controls and mutants. All data were confirmed with at least two or three independent mice. Total numbers of analyzed nuclei in at least two independent experiments are shown in each panel.

Immunoprecipitation

Testes from CD-1 mice were dissected and incubated in 0.5 mg/ml collagenase and 16 U/ml DNase I at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were lysed with TNE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40) containing complete EDTA-free medium (Roche) at 4°C for 30 min. After centrifugation, supernatants containing 5 mg of proteins were incubated with protein G Dynabeads (Life Technologies) coupled with mouse control IgG (EMD Millipore) and anti–phospho-ATM antibodies (Rockland) at 4°C. The samples were washed with TNE buffer and eluted with 2× SDS loading buffer. Proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membrane was blocked in 5% dry milk and analyzed using anti-ATM (1:500; EMD Millipore), -ATR (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology), and -TOPBP1 antibodies (1:500; gift from J. Chen), and visualized using ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Real-time RT-PCR

For real-time RT-PCR, RNA was prepared using Trizol, DNase-treated (Ambion), reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen), and then random hexamer primed. Real-time PCR was performed with the StepOnePlus system (ABI) using the following conditions: 95°C, 20 s; (95°C, 3 s; 60°C, 30 s) for 40 cycles. β-Actin expression was used for normalization. Forward and reverse primers were as follows: β-actin: 5′-CCGTGAAAAGATGACCCAG-3′ and 5′-TAGCCACGCTCGGTCAGG-3′; LINE-1 ORF2: 5′-GGAGGGACATTTCATTCTCATCA-3′ and 5′-GCTGCTCTTGTATTTGGAGCATAGA-3′; IAP GAG: 5′-AACCAATGCTAATTTCACCTTGGT-3′ and 5′-GCCAATCAGCAGGCGTTAGT-3′; SINE B1 5′-TGAGTTCGAGGCCAGCCTGGTCTA-3′ and 5′-ACAGGGTTTCTCTGTGTAGCCCTG-3′; Major satellite: 5′-GGCGAGAAAACTGAAAATCACG-3′ and 5′-CTTGCCATATTCCACGTCCT-3′.

In situ hybridization

Paraformaldehyde-fixed frozen sections of adult testes from Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice and those of its control littermates (Brca1Δ/+53bp1−/−) were processed onto the same slide and hybridized with 35S-labeled cRNA probes (Lim et al., 1997). Mouse-specific antisense and sense cRNA probes for γ-satellite (PγSa plasmid; Lundgren et al., 2000) were used for hybridization.

Small RNA sequencing

Total RNA was purified from the testes of Brca1Δ/Δ53bp1−/− mice and those of its control littermates (Brca1Δ/+53bp1−/−) at postnatal day 14. Small RNA sequencing was performed using a next-generation sequencing platform (Hiseq 2000; Illumina). Sequence processing (removing adapters and grouping identical sequences) was performed using miRExpress (Wang et al., 2009). Reads were mapped to the mm9 reference genome with Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009) with no mismatches allowed and all alternative match locations reported. Genomic annotation of reads was based on overlap with genome elements. In cases of multiple possible annotations, the element type with the largest number of mappings was selected, with ties resolved in the following order of priority: satellite, ncRNA, miRNA, LTR, SINE, LINE, exons, and introns.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the characterization of Brca1 mutants, including evaluation of the efficiency of conditional deletion of Brca1, apoptosis assay, and meiotic progression. Fig. S2 shows ectopic accumulation of ATR and TOPBP1 on autosome axes in Brca1 mutants. Fig. S3 shows the localization of phospho-ATM in Brca1 mutants. Fig. S4 shows autosomal asynapsis in Brca1 mutants. Fig. S5 shows that BRCA1 does not regulate heterochromatin proteins on the X-PCH, but suppresses satellite DNA expression detected by in situ hybridization and regulates LTR expression detected by small RNA sequencing. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201311050/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Developmental Fund and Trustee Grant at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center to S.H. Namekawa, the Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Award from the March of Dimes Foundation to S.H. Namekawa, the National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health) Intramural Research Program to R.D. Camerini-Otero, and National Institutes of Health grants HL085587 to P.R. Andreassen and GM098605 to S.H. Namekawa.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- DDR

- DNA damage response

- DSB

- DNA double-strand break

- HR

- homologous recombination

- LTR

- long terminal repeat

- MSCI

- meiotic sex chromosome inactivation

- NHEJ

- nonhomologous end joining

- PAR

- pseudoautosomal region

- PCH

- pericentric heterochromatin

References

- Ahmed E.A., van der Vaart A., Barten A., Kal H.B., Chen J., Lou Z., Minter-Dykhouse K., Bartkova J., Bartek J., de Boer P., de Rooij D.G. 2007. Differences in DNA double strand breaks repair in male germ cell types: lessons learned from a differential expression of Mdc1 and 53BP1. DNA Repair (Amst.). 6:1243–1254 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarends W.M., Wassenaar E., van der Laan R., Hoogerbrugge J., Sleddens-Linkels E., Hoeijmakers J.H., de Boer P., Grootegoed J.A. 2005. Silencing of unpaired chromatin and histone H2A ubiquitination in mammalian meiosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:1041–1053 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1041-1053.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkenist C.J., Kastan M.B. 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 421:499–506 10.1038/nature01368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barchi M., Mahadevaiah S., Di Giacomo M., Baudat F., de Rooij D.G., Burgoyne P.S., Jasin M., Keeney S. 2005. Surveillance of different recombination defects in mouse spermatocytes yields distinct responses despite elimination at an identical developmental stage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:7203–7215 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7203-7215.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellani M.A., Romanienko P.J., Cairatti D.A., Camerini-Otero R.D. 2005. SPO11 is required for sex-body formation, and Spo11 heterozygosity rescues the prophase arrest of Atm−/− spermatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 118:3233–3245 10.1242/jcs.02466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A., Ear U.S., Koller B.H., Weichselbaum R.R., Bishop D.K. 2000. The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is required for subnuclear assembly of Rad51 and survival following treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23899–23903 10.1074/jbc.C000276200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D.K., Park D., Xu L., Kleckner N. 1992. DMC1: a meiosis-specific yeast homolog of E. coli recA required for recombination, synaptonemal complex formation, and cell cycle progression. Cell. 69:439–456 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90446-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman P., Aly A., Escandell J.M., Pieterse M., Bartkova J., van der Gulden H., Hiddingh S., Thanasoula M., Kulkarni A., Yang Q., et al. 2010. 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple-negative and BRCA-mutated breast cancers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:688–695 10.1038/nsmb.1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting S.F., Callén E., Wong N., Chen H.T., Polato F., Gunn A., Bothmer A., Feldhahn N., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Cao L., et al. 2010. 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell. 141:243–254 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting S.F., Callén E., Kozak M.L., Kim J.M., Wong N., López-Contreras A.J., Ludwig T., Baer R., Faryabi R.B., Malhowski A., et al. 2012. BRCA1 functions independently of homologous recombination in DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol. Cell. 46:125–135 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carofiglio F., Inagaki A., de Vries S., Wassenaar E., Schoenmakers S., Vermeulen C., van Cappellen W.A., Sleddens-Linkels E., Grootegoed J.A., Te Riele H.P., et al. 2013. SPO11-independent DNA repair foci and their role in meiotic silencing. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003538 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia A., Elledge S.J. 2010. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell. 40:179–204 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimprich K.A., Cortez D. 2008. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:616–627 10.1038/nrm2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel K., Lange J., Hached K., Fu J., Anastassiadis K., Roig I., Cooke H.J., Stewart A.F., Wassmann K., Jasin M., et al. 2011. Meiotic homologue alignment and its quality surveillance are controlled by mouse HORMAD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:599–610 10.1038/ncb2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y., Hakimi M.A., Chen X., Kumaraswamy E., Cooch N.S., Godwin A.K., Shiekhattar R. 2003. Regulation of BRCC, a holoenzyme complex containing BRCA1 and BRCA2, by a signalosome-like subunit and its role in DNA repair. Mol. Cell. 12:1087–1099 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00424-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann W., Cohen P.E., Kane M., Lau K., Morrow B., Bennett S., Umar A., Kunkel T., Cattoretti G., Chaganti R., et al. 1996. Meiotic pachytene arrest in MLH1-deficient mice. Cell. 85:1125–1134 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81312-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O., Mahadevaiah S.K., Celeste A., Romanienko P.J., Camerini-Otero R.D., Bonner W.M., Manova K., Burgoyne P., Nussenzweig A. 2003. H2AX is required for chromatin remodeling and inactivation of sex chromosomes in male mouse meiosis. Dev. Cell. 4:497–508 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00093-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foray N., Marot D., Gabriel A., Randrianarison V., Carr A.M., Perricaudet M., Ashworth A., Jeggo P. 2003. A subset of ATM- and ATR-dependent phosphorylation events requires the BRCA1 protein. EMBO J. 22:2860–2871 10.1093/emboj/cdg274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T., Pratto F., Schimenti J.C., Turner J.M., Camerini-Otero R.D., Höög C. 2012. Phosphorylation of chromosome core components may serve as axis marks for the status of chromosomal events during mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002485 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo T., Shirley L., John G.B., Castrillon D.H. 2007. Generation of a germ cell-specific mouse transgenic Cre line, Vasa-Cre. Genesis. 45:413–417 10.1002/dvg.20310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg R.A., Sobhian B., Pathania S., Cantor S.B., Nakatani Y., Livingston D.M. 2006. Multifactorial contributions to an acute DNA damage response by BRCA1/BARD1-containing complexes. Genes Dev. 20:34–46 10.1101/gad.1381306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huen M.S., Sy S.M., Chen J. 2010. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:138–148 10.1038/nrm2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijima Y., Ichijima M., Lou Z., Nussenzweig A., Camerini-Otero R.D., Chen J., Andreassen P.R., Namekawa S.H. 2011. MDC1 directs chromosome-wide silencing of the sex chromosomes in male germ cells. Genes Dev. 25:959–971 10.1101/gad.2030811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijima Y., Sin H.S., Namekawa S.H. 2012. Sex chromosome inactivation in germ cells: emerging roles of DNA damage response pathways. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69:2559–2572 10.1007/s00018-012-0941-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inselman A., Eaker S., Handel M.A. 2003. Temporal expression of cell cycle-related proteins during spermatogenesis: establishing a timeline for onset of the meiotic divisions. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 103:277–284 10.1159/000076813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalocsay M., Hiller N.J., Jentsch S. 2009. Chromosome-wide Rad51 spreading and SUMO-H2A.Z-dependent chromosome fixation in response to a persistent DNA double-strand break. Mol. Cell. 33:335–343 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa R., Bakkenist C.J., McKinnon P.J., Kastan M.B. 2004. Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM–NBS1–BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev. 18:1423–1438 10.1101/gad.1200304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneitz B., Cohen P.E., Avdievich E., Zhu L., Kane M.F., Hou H., Jr, Kolodner R.D., Kucherlapati R., Pollard J.W., Edelmann W. 2000. MutS homolog 4 localization to meiotic chromosomes is required for chromosome pairing during meiosis in male and female mice. Genes Dev. 14:1085–1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogo H., Tsutsumi M., Inagaki H., Ohye T., Kiyonari H., Kurahashi H. 2012a. HORMAD2 is essential for synapsis surveillance during meiotic prophase via the recruitment of ATR activity. Genes Cells. 17:897–912 10.1111/gtc.12005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogo H., Tsutsumi M., Ohye T., Inagaki H., Abe T., Kurahashi H. 2012b. HORMAD1-dependent checkpoint/surveillance mechanism eliminates asynaptic oocytes. Genes Cells. 17:439–454 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange J., Pan J., Cole F., Thelen M.P., Jasin M., Keeney S. 2011. ATM controls meiotic double-strand-break formation. Nature. 479:237–240 10.1038/nature10508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S.L. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10:R25 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H., Paria B.C., Das S.K., Dinchuk J.E., Langenbach R., Trzaskos J.M., Dey S.K. 1997. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2–deficient mice. Cell. 91:197–208 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80402-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.Y., Wu J., Ye L., Gavrilina G.B., Saunders T.L., Yu X. 2010. RNF8-dependent histone modifications regulate nucleosome removal during spermatogenesis. Dev. Cell. 18:371–384 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W.J., Chapo J., Roig I., Abrams J.M. 2010. Meiotic recombination provokes functional activation of the p53 regulatory network. Science. 328:1278–1281 10.1126/science.1185640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.Y., Xiong Y., Kuang H., Korakavi G., Yu X. 2013. Regulation of the DNA damage response on male meiotic sex chromosomes. Nat. Commun. 4:2105 10.1038/ncomms3105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijsterburg M.S., Acs K., Ackermann L., Wiegant W.W., Bekker-Jensen S., Larsen D.H., Khanna K.K., van Attikum H., Mailand N., Dantuma N.P. 2012. A new non-catalytic role for ubiquitin ligase RNF8 in unfolding higher-order chromatin structure. EMBO J. 31:2511–2527 10.1038/emboj.2012.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J., Lukas C., Bartek J. 2011. More than just a focus: The chromatin response to DNA damage and its role in genome integrity maintenance. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1161–1169 10.1038/ncb2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren M., Chow C.M., Sabbattini P., Georgiou A., Minaee S., Dillon N. 2000. Transcription factor dosage affects changes in higher order chromatin structure associated with activation of a heterochromatic gene. Cell. 103:733–743 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00177-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynahan M.E., Chiu J.W., Koller B.H., Jasin M. 1999. Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol. Cell. 4:511–518 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80202-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa S.H. 2014. Slide preparation method to preserve three-dimensional chromatin architecture of testicular germ cells. J. Vis. Exp. 10:e50819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa S.H., Lee J.T. 2011. Detection of nascent RNA, single-copy DNA and protein localization by immunoFISH in mouse germ cells and preimplantation embryos. Nat. Protoc. 6:270–284 10.1038/nprot.2010.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa S.H., Park P.J., Zhang L.F., Shima J.E., McCarrey J.R., Griswold M.D., Lee J.T. 2006. Postmeiotic sex chromatin in the male germline of mice. Curr. Biol. 16:660–667 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J.C., Karpen G.H. 2008. Epigenetic regulation of heterochromatic DNA stability. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 18:204–211 10.1016/j.gde.2008.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera D., Perez-Hidalgo L., Moens P.B., Reini K., Lakin N., Syväoja J.E., San-Segundo P.A., Freire R. 2004. TopBP1 and ATR colocalization at meiotic chromosomes: role of TopBP1/Cut5 in the meiotic recombination checkpoint. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:1568–1579 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A.H., Plug A.W., van Vugt M.J., de Boer P. 1997. A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res. 5:66–68 10.1023/A:1018445520117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman D.L., Cobb J., Schimenti K.J., Wilson L.A., Cooper D.M., Brignull E., Handel M.A., Schimenti J.C. 1998. Meiotic prophase arrest with failure of chromosome synapsis in mice deficient for Dmc1, a germline-specific RecA homolog. Mol. Cell. 1:697–705 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80069-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo S.E., Jackson S.P. 2011. Dynamics of DNA damage response proteins at DNA breaks: a focus on protein modifications. Genes Dev. 25:409–433 10.1101/gad.2021311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanienko P.J., Camerini-Otero R.D. 2000. The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol. Cell. 6:975–987 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00097-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H., Polikiewicz G., Mahadevaiah S.K., Prosser H., Mitchell M., Bradley A., de Rooij D.G., Burgoyne P.S., Turner J.M. 2010. Evidence that meiotic sex chromosome inactivation is essential for male fertility. Curr. Biol. 20:2117–2123 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royo H., Prosser H., Ruzankina Y., Mahadevaiah S.K., Cloutier J.M., Baumann M., Fukuda T., Höög C., Tóth A., de Rooij D.G., et al. 2013. ATR acts stage specifically to regulate multiple aspects of mammalian meiotic silencing. Genes Dev. 27:1484–1494 10.1101/gad.219477.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe J.P., Lin H. 2011. Small noncoding RNAs in the germline. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3:a002717 10.1101/cshperspect.a002717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully R., Chen J., Plug A., Xiao Y., Weaver D., Feunteun J., Ashley T., Livingston D.M. 1997. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 88:265–275 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81847-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin Y.H., Choi Y., Erdin S.U., Yatsenko S.A., Kloc M., Yang F., Wang P.J., Meistrich M.L., Rajkovic A. 2010. Hormad1 mutation disrupts synaptonemal complex formation, recombination, and chromosome segregation in mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001190 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin H.S., Barski A., Zhang F., Kartashov A.V., Nussenzweig A., Chen J., Andreassen P.R., Namekawa S.H. 2012. RNF8 regulates active epigenetic modifications and escape gene activation from inactive sex chromosomes in post-meiotic spermatids. Genes Dev. 26:2737–2748 10.1101/gad.202713.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sy S.M., Huen M.S., Chen J. 2009. PALB2 is an integral component of the BRCA complex required for homologous recombination repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:7155–7160 10.1073/pnas.0811159106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarsounas M., Davies D., West S.C. 2003. BRCA2-dependent and independent formation of RAD51 nuclear foci. Oncogene. 22:1115–1123 10.1038/sj.onc.1206263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.M. 2007. Meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Development. 134:1823–1831 10.1242/dev.000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.M., Burgoyne P.S., Singh P.B. 2001. M31 and macroH2A1.2 colocalise at the pseudoautosomal region during mouse meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 114:3367–3375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.M., Aprelikova O., Xu X., Wang R., Kim S., Chandramouli G.V., Barrett J.C., Burgoyne P.S., Deng C.X. 2004. BRCA1, histone H2AX phosphorylation, and male meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Curr. Biol. 14:2135–2142 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner J.M., Mahadevaiah S.K., Fernandez-Capetillo O., Nussenzweig A., Xu X., Deng C.X., Burgoyne P.S. 2005. Silencing of unsynapsed meiotic chromosomes in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 37:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart A.J., Gatei M., Richard D.J., Khanna K.K. 2011. ATM mediated phosphorylation of CHD4 contributes to genome maintenance. Genome Integr. 2:1 10.1186/2041-9414-2-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden G.W., Derijck A.A., Pósfai E., Giele M., Pelczar P., Ramos L., Wansink D.G., van der Vlag J., Peters A.H., de Boer P. 2007. Chromosome-wide nucleosome replacement and H3.3 incorporation during mammalian meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Nat. Genet. 39:251–258 10.1038/ng1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.C., Lin F.M., Chang W.C., Lin K.Y., Huang H.D., Lin N.S. 2009. miRExpress: analyzing high-throughput sequencing data for profiling microRNA expression. BMC Bioinformatics. 10:328 10.1186/1471-2105-10-328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward I.M., Minn K., van Deursen J., Chen J. 2003. p53 Binding protein 53BP1 is required for DNA damage responses and tumor suppression in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:2556–2563 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2556-2563.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasz L., Daniel K., Roig I., Bolcun-Filas E., Xu H., Boonsanay V., Eckmann C.R., Cooke H.J., Jasin M., Keeney S., et al. 2009. Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000702 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtasz L., Cloutier J.M., Baumann M., Daniel K., Varga J., Fu J., Anastassiadis K., Stewart A.F., Reményi A., Turner J.M., Tóth A. 2012. Meiotic DNA double-strand breaks and chromosome asynapsis in mice are monitored by distinct HORMAD2-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Genes Dev. 26:958–973 10.1101/gad.187559.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Wagner K.U., Larson D., Weaver Z., Li C., Ried T., Hennighausen L., Wynshaw-Boris A., Deng C.X. 1999. Conditional mutation of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells results in blunted ductal morphogenesis and tumour formation. Nat. Genet. 22:37–43 10.1038/8743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Aprelikova O., Moens P., Deng C.X., Furth P.A. 2003. Impaired meiotic DNA-damage repair and lack of crossing-over during spermatogenesis in BRCA1 full-length isoform deficient mice. Development. 130:2001–2012 10.1242/dev.00410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K., Kondoh G., Matsuda Y., Habu T., Nishimune Y., Morita T. 1998. The mouse RecA-like gene Dmc1 is required for homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis. Mol. Cell. 1:707–718 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80070-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Fan Q., Ren K., Andreassen P.R. 2009a. PALB2 functionally connects the breast cancer susceptibility proteins BRCA1 and BRCA2. Mol. Cancer Res. 7:1110–1118 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Ma J., Wu J., Ye L., Cai H., Xia B., Yu X. 2009b. PALB2 links BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the DNA-damage response. Curr. Biol. 19:524–529 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Bick G., Park J.Y., Andreassen P.R. 2012. MDC1 and RNF8 function in a pathway that directs BRCA1-dependent localization of PALB2 required for homologous recombination. J. Cell Sci. 125:6049–6057 10.1242/jcs.111872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q., Pao G.M., Huynh A.M., Suh H., Tonnu N., Nederlof P.M., Gage F.H., Verma I.M. 2011. BRCA1 tumour suppression occurs via heterochromatin-mediated silencing. Nature. 477:179–184 10.1038/nature10371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.