Cancer genome sequencing studies indicate that a single breast cancer typically harbors multiple genetically distinct subclones1–4. Since carcinogenesis involves a breakdown in the cell-cell cooperation that normally maintains epithelial tissue architecture, individual subclones within a malignant microenvironment are commonly depicted as self-interested competitors5,6. Alternatively, breast cancer subclones might interact cooperatively to gain a selective growth advantage in some cases. Although interclonal cooperation has been shown to drive tumorigenesis in fruitfly models7,8, definitive evidence for functional cooperation between epithelial tumor cell subclones in mammals is lacking. Here, we use mouse models of breast cancer to show that interclonal cooperation can be essential for tumor maintenance. Aberrant expression of the secreted signaling molecule Wnt1 generates mixed-lineage mammary tumors composed of basal and luminal tumor cell subtypes, which purportedly derive from a bipotent malignant progenitor cell residing atop a tumor cell hierarchy9. Using somatic HRas mutations as clonal markers, we show that some Wnt tumors indeed conform to a hierarchical configuration, but others unexpectedly harbor genetically distinct basal HRas mutant (HRasmut) and luminal HRas wild-type (HRaswt) subclones. Both subclones are required for efficient tumor propagation, which strictly depends on luminally-produced Wnt1. When biclonal tumors were challenged with Wnt withdrawal to simulate targeted therapy, analysis of tumor regression and relapse revealed that basal subclones recruit heterologous Wnt-producing cells to restore tumor growth. Alternatively, in the absence of a substitute Wnt source, the original subclones often evolve to rescue Wnt pathway activation and drive relapse, either by restoring cooperation or by switching to a defector strategy. Uncovering similar modes of interclonal cooperation in human cancers may inform efforts aimed at eradicating tumor cell communities.

Cancer progression is known to depend on cooperation between tumor cells and neighboring host cells in the microenvironment. Some have suggested that cooperation between distinct tumor cell subsets also may contribute to the malignant phenotype10–12. Favoring this possibility, genetically distinct subclones cooperatively enhanced tumor growth in models engineered to recapitulate a form of tumor cell heterogeneity identified in brain cancers13. Similarly, phenotypically distinct tumor cell subsets cooperatively enhanced tumor invasion in a murine lung cancer model14. In the case of human breast cancer, recent studies highlight the phenotypic and genetic diversity present locally within individual tumors15,16, but whether this heterogeneity is a cause or a consequence of tumor progression remains unclear. Accordingly, we sought definitive evidence for functional cooperation between tumor cell subsets in mouse models of human breast cancer.

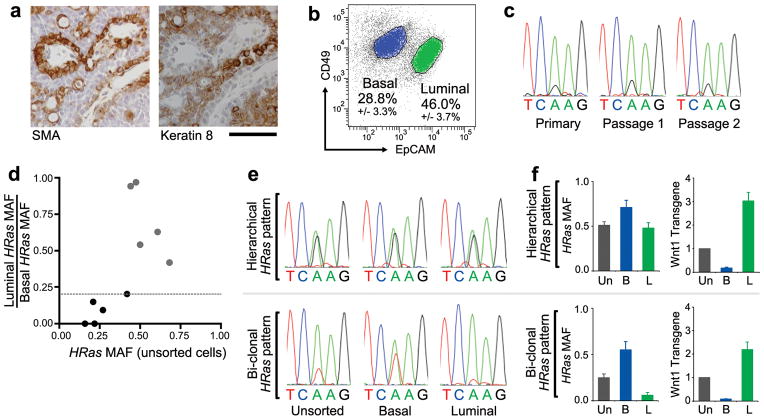

Mammary cancers arising in the classic MMTV-Wnt1 transgenic mouse model17 display tumor cell heterogeneity that is widely attributed to malignant transformation of a bipotent mammary progenitor cell9,18,19. Concordantly, MMTV-Wnt1 tumor cells partition into basal and luminal subsets which comingle, recalling the corresponding basal and luminal lineages found in the normal mammary gland (Figure 1a, b). Although mutations in Wnt pathway components are rare in human breast cancers, the transcriptional profile of Wnt1-initiated tumors resembles that of other mammary cancer models that commonly show mixed-lineage histopathology, including chemical carcinogen-induced rodent mammary cancers20,21.

Figure 1. Evidence for distinct basal HRasmut/Wnt1low and luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high subclones within some MMTV-Wnt1 tumors.

a, Immunostaining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and Keratin-8 performed on serial sections of a representative MMTV-Wnt1 mammary tumor. Scale bar, 50μm. b, Separation of MMTV-Wnt1 tumor cells into basal (CD49fhigh/EpCAMlow) and luminal (CD49flow/EpCAMhigh) cell subpopulations by flow cytometry. Percentages depict mean +/− SEM for n = 10 tumors. c, DNA sequencing chromatograms depicting an HRasCAA61CGA mutation appearing at a fixed MAF during serial propagation of an MMTV-Wnt1 tumor. d, Graphic depiction of the ratio of luminal to basal HRas MAF plotted against the MAF for unsorted cells. Dotted line depicts the threshold at which tumors show 5-fold HRasmut allele enrichment in basal versus luminal cells. Black circles denote tumor values with >5-fold basal enrichment. e, DNA sequencing chromatograms depicting an HRasCAA61CGA mutation (upper panels) and an HRasCAA61CTA mutation (lower panels) detected in representative Wnt tumors whose basal HRasmut allele enrichment fits a hierarchical pattern or biclonal pattern, respectively. f, Tumor cell populations analyzed by DNA sequencing and by qRT-PCR for Wnt1 expression relative to Gapdh. Histograms at left show HRas MAFs determined from chromatogram peak heights. Histograms at right show relative Wnt1 expression with values from unsorted tumor cells set at 1. Un, unsorted; B, basal; L, luminal. Data represent mean +/− SEM for n = 5 tumors of each pattern.

While studying cooperating oncogenic mutations in the MMTV-Wnt1 model, we found evidence suggesting some Wnt tumors harbor unexpected genetic heterogeneity. About half of all Wnt-initiated mammary tumors spontaneously acquire somatic HRas mutations that encode an activated oncoprotein22,23. Since HRas mutations act dominantly, HRas mutant allele fractions (MAFs) of approximately 0.5 are expected, barring copy number changes at the HRas locus. Instead, when tumor-derived HRas alleles were amplified by PCR and subjected to DNA sequencing, chromatogram peak heights often indicated smaller HRas MAFs with fractions < 0.3 detected in 4 of 10 tumors. Notably, tumors maintained their small HRas MAFs as a stable property when explanted onto the flanks of syngeneic host mice (Fig. 1c). This discrepancy could not be explained by contamination of samples with normal (non-tumor) cells since tumor cell content assessed by histopathology consistently exceeded 80%. Moreover, copy number variations leading to either HRaswt allele gain or HRasmut allele loss seemed unlikely driver events. Instead, we considered whether some Wnt tumors might harbor distinct HRasmut and HRaswt subclones, noting that biclonal tumors would adopt a mixed-lineage phenotype provided each subclone were committed to a distinct lineage.

To search for lineage-restricted HRasmut and HRaswt subclones, dissociated cells prepared from Hrasmut Wnt tumors were sorted into basal and luminal subsets (Extended Data Fig. 1), then HRas MAFs were determined for each subset and for corresponding samples of unsorted cells. Half of the HRasmut Wnt tumors analyzed (5 of 10) showed negligible subset-specific enrichment in HRasmut alleles, a pattern consistent with a hierarchical configuration (Fig. 1d,e). In these cases, basal and luminal cells from the same tumor always harbored identical HRasmut alleles (Fig. 1e), suggesting they descended from a common bipotent HRasmut progenitor. In contrast, for the remaining half of tumors analyzed, HRasmut alleles were highly enriched within the basal tumor cell subset, a pattern consistent with a biclonal configuration (Fig. 1e). Basal HRasmut allele enrichment correlated with a lower overall HRas MAF, further suggesting the presence of a private, subclone-restricted mutation. Regardless of whether the distribution of HRasmut alleles fit a hierarchical or biclonal pattern, tumors showed classic mixed-lineage histopathology (Extended Data Fig. 2), and luminal tumor cells were invariably the main source of Wnt1 expression as previously reported24 (Fig. 1f). Therefore, some Wnt tumors appeared to harbor distinct basal HRasmut/Wnt1low and luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high subclones, implicating interclonal cooperation in tumor maintenance. These findings recall early reports in which MMTV-associated mammary tumors initiated by activation of endogenous Wnt genes sometimes were noted to be oligoclonal25,26.

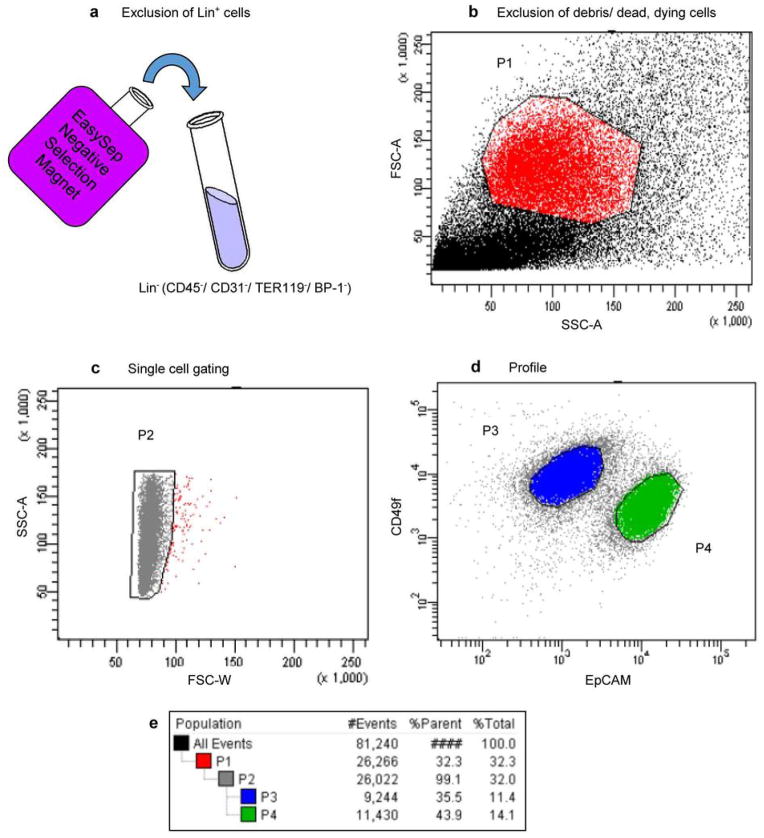

Extended Data Figure 1. FACS gating strategy for resolving basal and luminal subsets from mammary tumors.

Mammary tumors were mechanically and enzymatically dissociated into single cell suspensions. a, Negative selection against Lin+ cells using Stem Cell Technologies EasySep Mouse Epithelial Cell Enrichment Kit. Resulting Lin− (CD45−/ CD31−/ TER119−/ BP-1−) cells were then immunostained with antibodies for CD49f (α6 integrin) and EpCAM and analyzed by FACS. b, Exclusion of cell debris and dead/ dying cells. Dead/dying cells collect as a band along the bottom of a FSC-A vs. SSC-A two-parameter plot, and these were gated out in P1. c, Cell doublets were discarded in P2. d, Basal and Luminal mammary epithelial cell populations were separated by immunophenotype. Basal epithelial cells are CD49fhigh/ EpCAMlow (P3) and luminal epithelial cells are CD49fLow/ EpCAMhigh (P4). e, Gating tree showing gating strategy for FACS analysis as well as parent and total cell percentages within each of the gates for a representative MMTV-Wnt1 tumor.

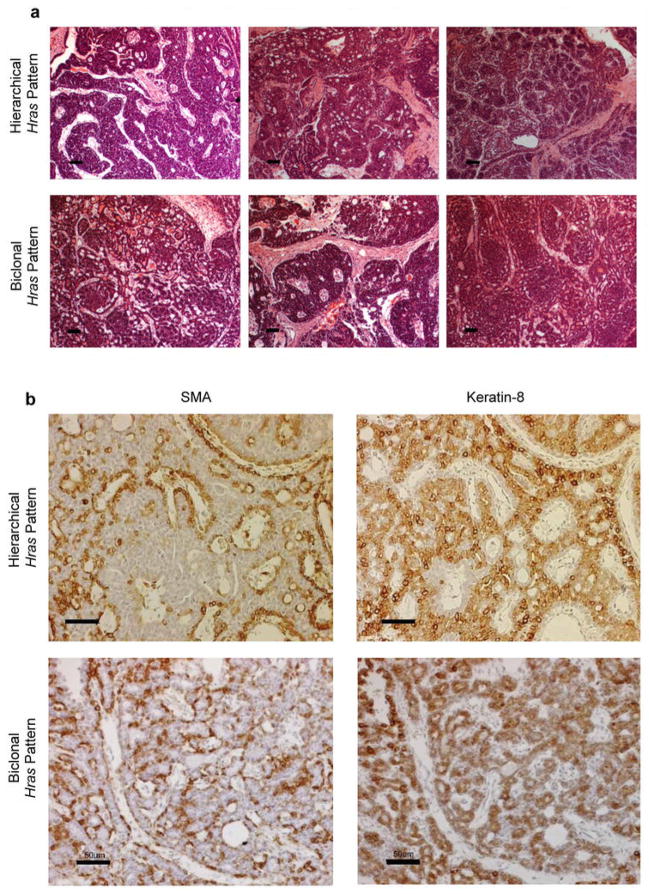

Extended Data Figure 2. Hierarchical and Biclonal MMTV-Wnt1 tumors are histologically indistinguishable.

a, H&E stained sections from a series of MMTV-Wnt1 mammary tumors whose HRasmut allele distribution pattern suggests hierarchical or biclonal configuration, as indicated. Scale bar, 50 um. b, Both hierarchical and bi-clonal MMTV-Wnt1 tumors display mixed-lineage character. Serial sections from a hierarchical and bi-clonal MMTV-Wnt1 mammary tumors immunostained for Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) or Keratin 8 (K8), which recognize basal and luminal epithelial cells respectively. For both, brown pigment is positive staining. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm.

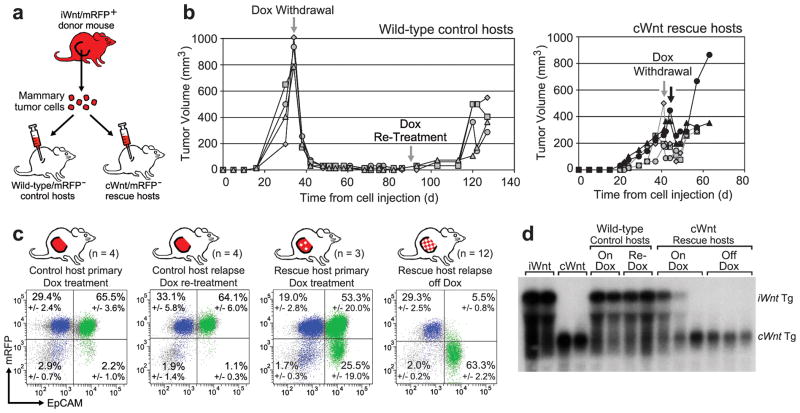

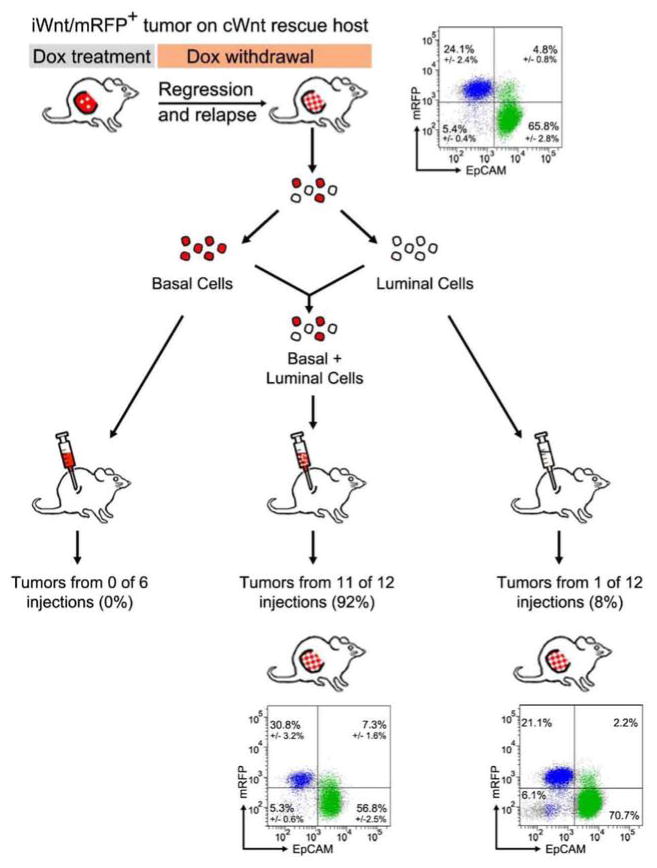

Seeking stringent proof that some Wnt tumors are biclonal and require interclonal cooperation for maintenance, we attempted to rescue growth of basal HRasmut/Wnt1low subclones from Wnt1 deprivation by providing access to replacement Wnt1-producing cells. For these experiments, the original MMTV-Wnt1 model (hereafter cWnt denoting constitutive Wnt1 expression) was used in combination with a closely related model engineered for doxycycline (Dox)-dependent transgene expression (MMTV-rtTA/Tet-O-Wnt1; hereafter iWnt denoting inducible Wnt1 expression). During chronic Dox treatment, iWnt mice and mammary tumors phenocopy their cWnt counterparts, but iWnt tumors regress following Dox withdrawal due to abrogation of Wnt1 transgene expression27. To enable tracking of cell lineages in tumor reconstitution experiments, iWnt mice were crossed with an mRFP reporter line, generating iWnt/mRFP+ mice. As expected, a subset of Dox-dependent iWnt/mRFP+ mammary tumors appeared biclonal, since they harbored a basally-restricted HRasmut subclone. After dissociating these tumors into cell suspensions, 105 unsorted cells were injected orthotopically into the mammary fat pads of two sets of Dox-treated, mRFP reporter-negative female host mice (Fig. 2a). Control hosts lacked a transgene capable of rescuing tumor cells from Wnt withdrawal (wt/mRFP−), whereas rescue hosts expressed the constitutive Wnt1 transgene (cWnt/mRFP−).

Figure 2. Rescue of basal HRasmut iWnt tumor cells from Wnt withdrawal by heterologous luminal cWnt cells.

a, Schematic of experimental design. b, Growth curves of tumors reconstituted on wild-type or cWnt hosts following injection of iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cells. c, Representative FACS plots showing contributions by donor-derived mRFP+ cells and host-derived mRFP− cells to reconstituted tumors. Percentages depict mean +/− SEM for n tumor explants as indicated. Colors indicate events within the basal (blue; CD49fHigh/EpCAMlow) and luminal (green; CD49fLow/EpCAMhigh) gates. d, Northern hybridization analysis of tumor RNA with Wnt1 probe. The larger bicistronic iWnt transcript encodes both Wnt1 and firefly luciferase.

During chronic Dox treatment, both control and rescue hosts developed mammary tumors in most glands injected with iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cells (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Table 1). As expected, these reconstituted tumors usually regressed when iWnt transgene expression was switched off via Dox withdrawal. On control hosts, tumor regression always was complete, and mice remained relapse-free during 6 weeks of monitoring. Interestingly, subclinical disease often persisted, since most control hosts subsequently relapsed after Dox re-treatment (Fig. 2b). By contrast, on cWnt rescue hosts, most reconstituted tumors only partially regressed, then relapsed spontaneously (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3a). On control hosts, primary tumors were reconstituted almost exclusively from donor mRFP+ cells, and relapses triggered by Dox re-treatment remained mRFP+ as expected (Fig. 2c). By contrast, on rescue hosts primary tumors showed varying degrees of chimerism due to incorporation of mRFP− (host-derived) luminal cells (Extended Data Fig. 3b), and relapses arising during Dox withdrawal always showed pronounced lineage-restricted chimerism, resulting in mRFP+/basal and mRFP−/luminal subpopulations (Fig. 2c). To confirm that donor basal subclones recruit host luminal epithelium to serve as a replacement Wnt1 source at relapse, we turned to Northern hybridization analysis of tumor RNAs. Strikingly, tumors reconstituted on rescue hosts typically expressed the larger iWnt transgene prior to Dox withdrawal (pertinent exceptions discussed in Extended Data Fig. 3), then switched to expressing the smaller cWnt transgene at relapse, indicating heterologous rescue (Fig. 2d).

Extended Data Table 1. Unsorted tumor cells efficiently reconstitute tumors.

Unsorted (FACS naïve) tumor cells from 3 independent iWnt/mRFP+ tumors were injected orthotopically into intact, post-pubertal mammary glands of wild-type control hosts or cWnt rescue hosts. Host mice were maintained on chronic Dox treatment. Each tumor harbored a different basally-restricted HRas mutation, as indicated. 105 tumor cells were injected into each gland.

| HRas mutation | No. of tumors*, wild-type hosts | No. of tumors*, cWnt hosts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor 1 | GGA12GAA | 8/12 (67%) | 20/24 (83%) |

| Tumor 2 | GGA12AGA | 4/4 (100%) | 4/4 (100%) |

| Tumor 3 | CAA61CGA | 4/4 (100%) | 3/4 (75%) |

| Totals | --- | 16/20 (80%) | 27/32 (84%) |

Shown as number of reconstituted tumor outgrowths per injected gland.

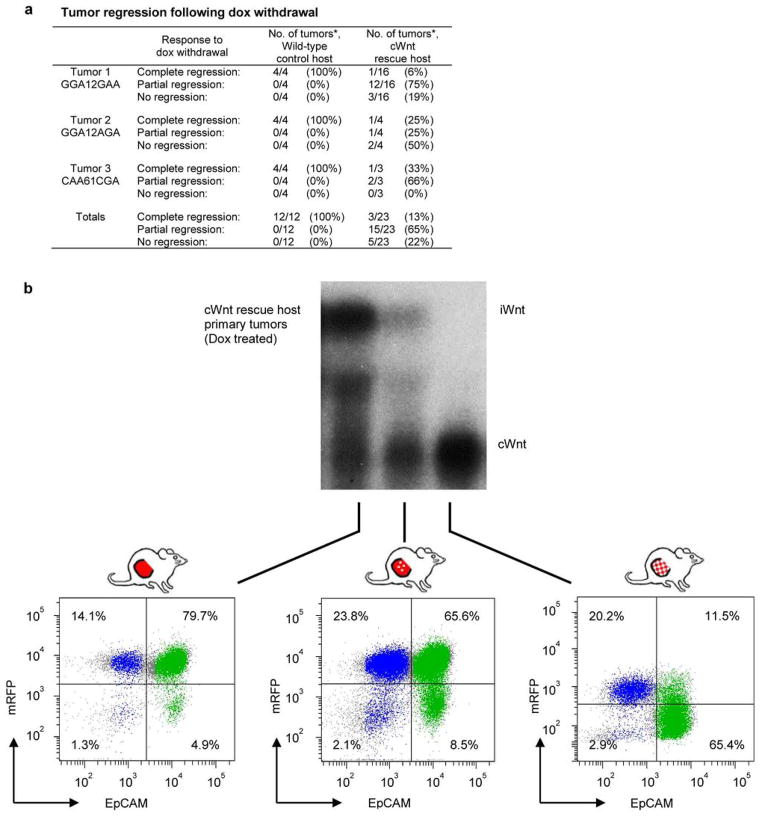

Extended Data Figure 3. Tumor regression following Dox withdrawal.

a, Tumors reconstituted on wild-type or cWnt hosts following injection of iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cells were subjected to Dox withdrawal and monitored for regression. *Shown as number of tumor regressions per number of tumors subjected to Dox withdrawal. b, Northern hybridization analysis of tumor RNA with Wnt1 probe. Tumors were reconstituted on Dox-treated cWnt hosts following injection of iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cells. Depicted below are the corresponding FACS plots showing the range of contributions by donor derived mRFP+ and host-derived mRFP− cells to reconstituted tumors prior to Dox withdrawal. Colors indicate events within the basal (blue; CD49fhigh/EpCAMlow) and luminal (green; CD49flow/EpCAMhigh) gates.

On rescue hosts, primary tumors that arose during Dox treatment incorporated a variable number of cWnt luminal cells, indicating that the crosstalk between heterologous cells required to seed relapse sometimes occurs early in tumor reconstitution. For one of three primary tumors analyzed, the conversion to lineage-restricted chimerism and cWnt transgene expression was essentially complete, meaning that cWnt-producing cells had replaced iWnt-producing cells despite ongoing Dox treatment. Analysis of this tumor required necropsy of the host, precluding determination of its clinical response to Dox withdrawal, which we propose would have been negligible. Concordantly, in rare cases the growth of sibling primary tumors propagated on rescue hosts continued unimpeded by Dox withdrawal, and these tumors always showed pronounced, lineage-restricted chimerism at necropsy. Elucidating mechanisms whereby host cWnt cells compete with luminal iWnt tumor cells to become the predominant Wnt-producing subclone may offer new insights into evolutionary forces shaping tumor microenvironments.

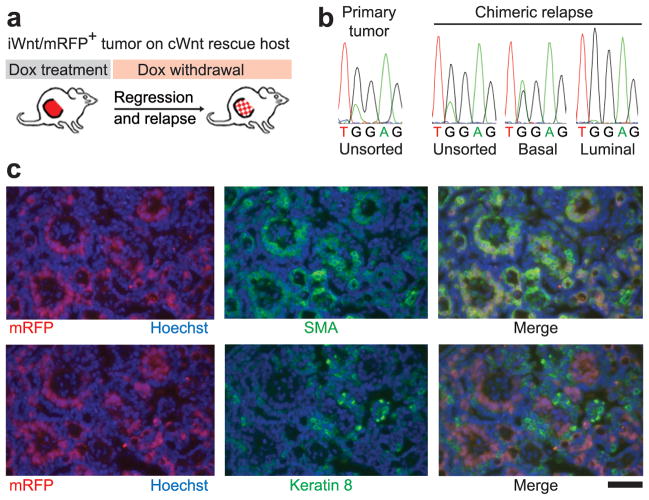

Figure 3. Lineage-restricted subclones recapitulate mosaiform heterogeneity in chimeric cWnt/iWnt tumors.

a, Schematic. b, DNA sequence chromatograms depicting matching HRasGGA12AGA mutations detected in unsorted and sorted populations from primary and relapsed tumors as indicated. c, Immunostaining of basal (SMA, top panels) and luminal (Keratin-8, lower panels) tumor cells within a Dox-independent relapse arising on a cWnt host. Red fluorescence marks donor-derived iWnt/mRFP+ cells intermingled with mRFP− host-derived cells. Scale bar, 50μm.

Furthermore, the biclonal configuration evident in parental tumors was maintained in all reconstituted tumors in that basal cells were HRasmut/Wnt1low whereas luminal cells were HRaswt/Wnt1high (Extended Data Fig. 4). We repeated these rescue experiments twice, beginning each time with an independent, iWnt/mRFP tumor harboring a distinct, basally-restricted HRas mutation. In all cases, we observed rescue of donor-derived basal HRasmut/Wnt1low tumor cells by cWnt host-derived luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high cells (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 5). Moreover, the HRasmut allele detected in relapsed tumors was always identical to that detected in parental tumors, confirming that basal subclones found at relapse were descended from donor-derived tumor cells and were not novel clones. Examination of tumor sections by fluorescence microscopy revealed pervasive intermingling of basal mRFP+ and luminal mRFP− tumor cells within chimeric relapses, consistent with the prevailing notion that secreted Wnts provide a short-range signal to neighboring cells (Fig. 3c). Prospective analysis of a larger set of independent Wnt tumors will be required to precisely estimate the overall fraction of Wnt tumors that is biclonally configured. Notably, we cannot yet determine clonal configurations for that half of Wnt tumors that lack an HRas mutation.

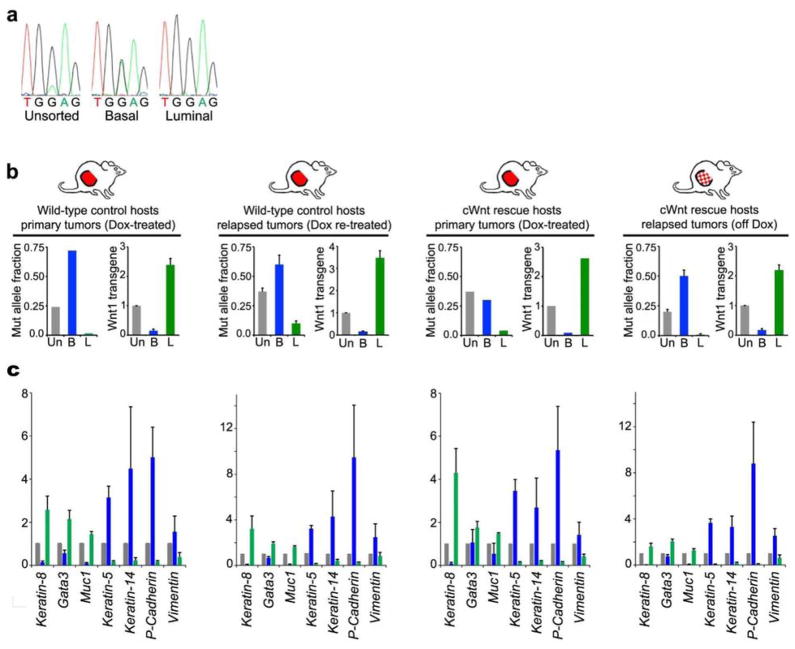

Extended Data Figure 4. Biclonal configuration of reconstituted iWnt/mRFP+ tumors.

a, DNA sequencing chromatograms depicting a basally-enriched HRasGGA12GAA mutation detected in the parental tumor. b, Evidence for distinct basal HRasmut/Wnt1low and luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high tumor subclones. Sorted tumor cell subsets were analyzed by DNA sequencing and by qRT-PCR for Wnt1 expression relative to Gapdh. Histograms at left show HRas MAFs determined from chromatogram peak heights. Histograms at right show relative Wnt1 expression with values from unsorted tumor cells set at 1. Un, unsorted; B, basal; L, luminal. Data represent mean +/− SEM for (from left to right) n = 2, 4, 3, 4, 1, 2, 6, or 12 explants. c, For each condition, sorted tumor cell subsets were analyzed by qRT-PCR for expression of several epithelial lineage-specific genes relative to Gapdh, with values for unsorted tumor cells set at 1. Gray bars, unsorted; Blue bars, basal; Green bars, luminal. Data represent mean +/− SEM for (from left to right) n = 4, 4, 3, or 12 explants.

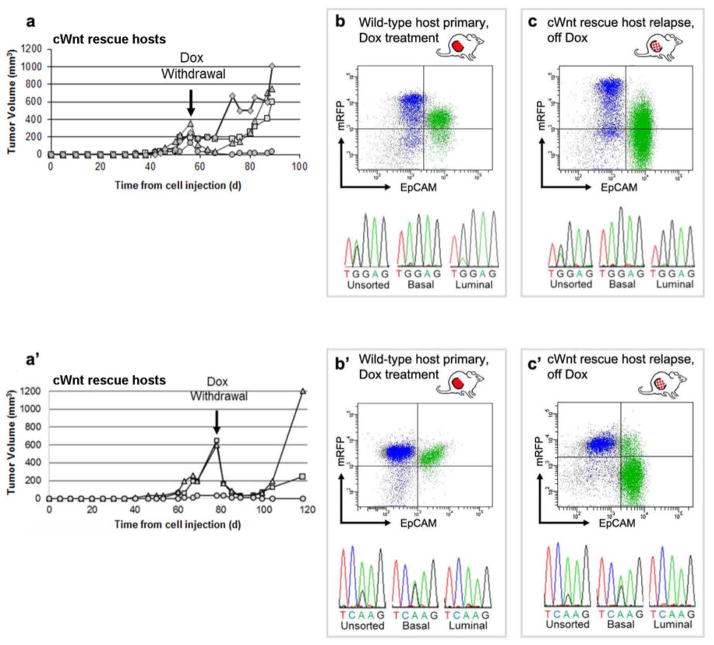

Extended Data Figure 5. Basal subclones from two additional iWnt/mRfp+ tumors rescued from Dox withdrawal by heterologous cWnt host cells.

a, Growth curves of tumor outgrowths derived from an iWnt/mRFP+ tumor harboring a basally-restricted HRasGGA12AGA mutation. Curves depict regression and relapse of tumors reconstituted on cWnt rescue hosts following Dox withdrawal. b,c, Upper panels. Representative FACS plots showing contributions from donor-derived mRFP+ cells and host-derived mRFP- cells during tumor reconstitution. Colors indicate events within the basal (blue; CD49fHigh/EpCAMlow) and luminal (green; CD49fLow/EpCAMhigh) gates. Lower panels. DNA sequencing chromatograms showing matching, basally-restricted HRas mutations present in both primary Dox-dependent tumors and chimeric Dox-independent relapses. a′–c′. Data panels presented as in a–c, showing similar results for an independent iWnt/mRFP+ tumor harboring a distinct, basally- restricted HRasCAA61CGA mutation. For both tumors shown here, Northern hybridization analysis confirmed expression of donor-derived iWnt transgene prior to Dox withdrawal, followed by a switch to expression of host-derived cWnt transgene at relapse (data not shown).

Whereas biclonal iWnt/mRFP+ tumors were readily reconstituted from unsorted (FACS-naïve) cells, sorted basal and luminal cells each reconstituted tumors inefficiently when injected into mammary glands (Extended Data Fig. 6a), perhaps owing in part to loss of cell viability during FACS. Remarkably, tumors that did arise after injecting a single sorted subtype always were biclonal, comprised of both basal HRasmut/Wnt1low and luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high subsets (7 of 7 tumors analyzed, Extended Data Fig. 6b). Given the imperfect separation achieved by FACS (95 – 98% purity), rare cells cross-contaminating each subset presumably sufficed to permit interclonal cooperation during tumor reconstitution. Consistent with this notion, the relative sizes of the basal and luminal cell populations within these tumors approximated that found in parental tumors and did not reflect the lineage enrichment achieved by sorting. We confirmed this result in an experimental context where the putative cooperating subclones were differentially labeled by the mRFP transgene. Here, tumor cells derived from chimeric relapses generated in our rescue experiment were studied prospectively. Again, neither the basal (mRFP+/HRasmut/Wnt1low) nor the luminal (mRFP−/HRaswt/Wnt1high) subsets reconstituted tumors efficiently, whereas a 1:1 admixture of both sorted populations reliably reconstituted biclonal tumors (Extended Data Fig. 7). Notably, every tumor reconstituted in these experiments faithfully restored the subclonal composition of the source tumor, pointing to strong selection favoring propagation of both subclones in tandem.

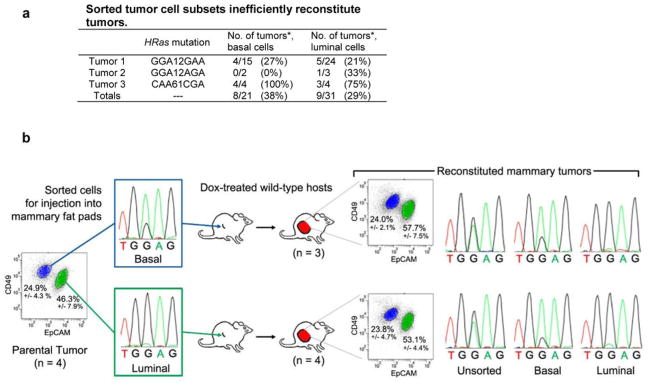

Extended Data Figure 6. Biclonal configuration of tumors reconstituted from sorted iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cell subsets.

a, Sorted tumor cell subsets inefficiently reconstitute tumors. Three independent iWnt/mRFP+ bi-clonal tumors were resolved into component basal and luminal tumor cell subsets by FACS. Each tumor harbored a different basally-restricted HRas mutation, as indicated. 105 sorted tumor cells were injected orthotopically into intact, post-pubertal mammary glands of wild-type host mice maintained on chronic Dox treatment. *Shown as number of reconstituted tumor outgrowths per injected gland. b, Tumor cells from a parental iWnt/mRFP+ tumor harboring a basally-restricted HRasGGA12GAA mutation were resolved into basal and luminal cell subsets by FACS. When these isolated tumor cell subsets were injected orthotopically into the mammary glands of Dox-treated wild-type hosts, few tumors were reconstituted. However, tumors that did arise always were comprised of basal HRasmut/Wnt1low and luminal HRaswt/Wnt1high subsets, implicating interclonal cooperation in tumor reconstitution (n = 3 tumors reconstituted from the basal cell-enriched subset; n = 4 tumors reconstituted from the luminal cell-enriched subset).

Extended Data Figure 7. Both sorted basal and sorted luminal cell populations are required to reconstitute biclonal tumors.

Chimeric tumor relapses generated by injecting iWnt/mRFP+ tumor cells onto cWnt rescue hosts were resolved into their component basal (mRFP+/HRasmut/Wnt1low) and luminal (mRFP−/HRaswt/Wnt1high) cell subsets by FACS. Each sorted population was injected separately (105 basal cells/injection or 105 luminal cells/injection) or as a 1:1 admixture (5×104 basal cells + 5×104 luminal cells/injection) onto wild-type, Dox-naïve hosts. All reconstituted tumors faithfully recapitulated the biclonal configuration of the source tumor. Depicted are FACS plots from parental and reconstituted tumors showing both mRFP+ and mRFP− subclonal populations. Colors indicate events within the basal (blue; CD49fHigh/EpCAMlow) and luminal (green; CD49fLow/EpCAMhigh) gates. Percentages depict mean +/− SEM for n = 5 clonally related parental tumor outgrowths and n = 11 tumor outgrowths reconstituted from injection of admixed cells.

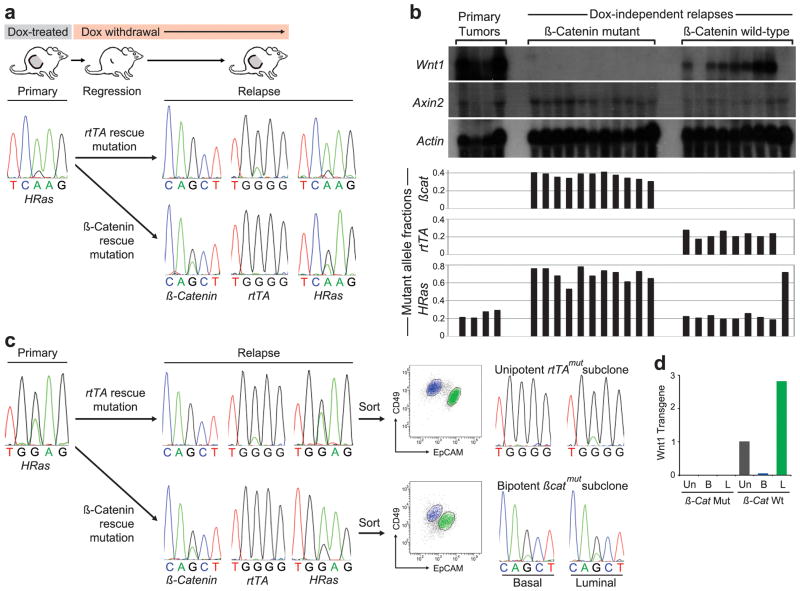

iWnt tumors that regress upon Dox withdrawal frequently relapse weeks later as Dox-independent tumors (DITs), mirroring the clinical scenario of acquired resistance to effective targeted therapy. Next, we asked which subclone(s) contribute when biclonal tumors beget relapse. A putative biclonal iWnt tumor with an HRas MAF <0.3 was identified and propagated on host mice, generating a set of Dox-dependent tumor explants. Explants maintained the HRas MAF observed in the parental tumor, suggesting a stable biclonal configuration (Fig. 4a,b). Host mice then were subjected to Dox withdrawal and monitored until relapse, generating a set of 20 DITs. In accord with our previous work28, 18 of the 20 relapses (90%) occurred through one of two mutually exclusive modes of Wnt pathway reactivation. Seven DITs (35%), re-expressed the Wnt1 transgene, and all 7 had acquired one of two rtTA mutations (G138R or H100Y) previously shown to rescue mammary tumors from oncogene withdrawal by enabling aberrant, Dox-independent expression of TetO-controlled transgenes29. All 7 of these tumors had an HRas MAF comparable to parental tumor (Fig. 4b), strongly suggesting that rtTA mutations originating within the HRaswt sublone restored both Wnt1 expression and cooperation with HRasmut cells, culminating in biclonal relapse.

Figure 4. Relapse of biclonal tumors through the evolution of either subclone.

a, DNA sequencing chromatograms depicting matching HRasCAA61CGA mutations detected in primary and relapsed tumors, with an increased MAF detected in the setting of a βcat mutation. b, Histogram depicting MAFs for a series of primary and relapsed tumors derived from a parental biclonal tumor. Upper panel depicts corresponding gene expression patterns for each tumor by Northern hybridization analysis. c, DNA sequencing chromatograms depicting matching HRasGGA12GAA mutations detected in primary and relapsed tumors, with an increased MAF detected in the setting of a βcat mutation. Panels at right depict analysis of unsorted and sorted cells at relapse showing unipotent or bipotent mutant subclones, depending on the mode of Wnt pathway reactivation. d, Histogram shows Wnt1 expression levels relative to Gapdh in unsorted and sorted tumor cells from a β-catmut/rtTAwt relapse versus a β-catwt/rtTAmut relapse with the value measured in unsorted cells from the latter relapse set at 1. Un, unsorted; B, basal; L, luminal.

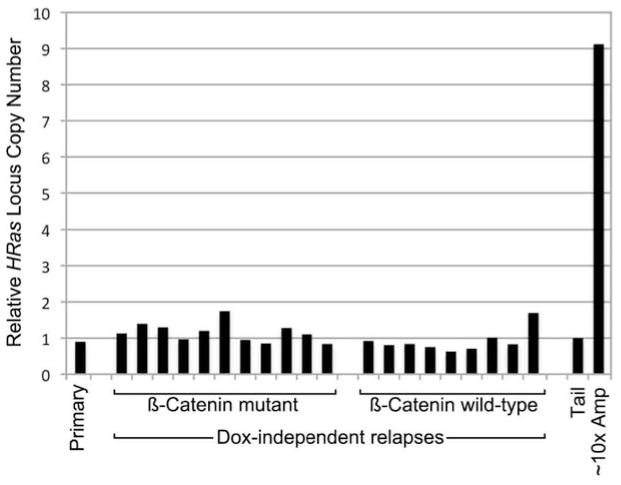

Eleven DITs (55%) instead rescued oncogenic signaling by acquiring an activating mutation in β-catenin (Ctnnb1, hereafter βcat), a key downstream Wnt effector (Fig 4a,b). Compared with parental tumor, these relapses showed markedly increased HRas MAFs that were highly reproducible across the tumor set (Fig. 4b). Therefore, βcat mutations likely originated within HRasmut cells that later emerged as predominant relapse clones. By activating the Wnt pathway in a cell-autonomous manner, βcat mutations presumably obviated the need to maintain cooperation with Wnt-producing HRaswt subclones. As such, βcatmut relapse clones act like “defectors” in evolutionary game theory terms. HRas MAFs in βcatmut relapses consistently exceeded 0.5, indicating that βcatmut clones must harbor additional HRas locus aberrations; however, no gross changes in HRas gene copy number were observed (Extended Data Fig. 8), implicating copy number neutral loss-of-heterozygosity events.

Extended Data Figure 8. Increased HRas MAFs in βcatmut DITs is not due to gross copy changes at the HRas locus.

Histogram depicts HRas allele copy number relative to β-actin determined for a cohort of clonally-related Wnt tumor outgrowths. Independent relapse samples are presented in the same order depicted in Fig. 4b. Copy number values were obtained by performing qPCR on genomic DNA from tumor samples and from normal tail, with tail values set at 1. As a positive control, we included a p19Arf-deficient Wnt tumor sample (~10x Amp) previously found to have approximately 10-fold HRas copy number gain as determined by Southern hybridization. Since, HRas MAFs reproducibly exceeded βcat MAFs by approximately 2-fold across the βcatmut relapse set (Fig. 4b), elevated HRas MAFs may reflect duplication of the HRasmut allele (e.g., via a gene conversion event) sometime in the life history of βcatmut subclones.

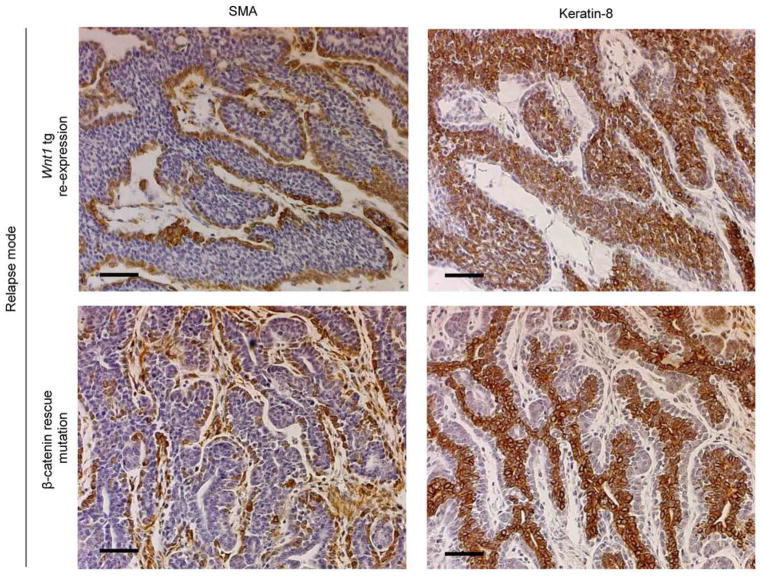

To further examine the clonal configuration of relapsed tumors, an iWnt/mRFP+ tumor previously confirmed as biclonal in our rescue experiments (Fig. 2) was propagated as above to derive DITs, then relapse-derived tumor cells were separated into basal and luminal subsets and analyzed. One DIT that relapsed via Wnt1 transgene re-expression was biclonal with a luminally-restricted rtTA mutation (Fig. 4c). Trophic support from this luminal rtTAmut subclone likely rescued growth of its basal rtTAwt counterpart, providing a plausible cellular mechanism whereby this rescue mutation was maintained at a low MAF. In contrast, our prior analysis indicated that βcat rescue mutations originate within basal tumor cells and obviate the need to cooperate with Wnt-producing luminal cells. Nonetheless, βcatmut relapses consistently harbored abundant luminal tumor cells (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 9). We hypothesized that acquired βcat mutations endow basally-restricted subclones with novel bipotent differentiation potential, thereby converting them to hierarchically-configured clones at relapse. Two βcatmut DITs analyzed as above showed comparable βcatmut allele prevalence in the basal and luminal subsets (Fig. 4c), consistent with a scenario in which βcatmut relapse clones acquired bipotency. (An alternative scenario in which each subclone independently acquired matching βcat mutations cannot be formally excluded, but seems less likely). In our prior experiments (Fig. 2, Extended Data Fig. 4) and in the rtTAmut relapse profiled above, this same subclone invariably behaved in a unipotent manner, remaining basally-restricted when partnered with a Wnt1-expressing luminal subclone in the context of primary and relapsed tumors.

Extended Data Figure 9. Mixed-lineage character of DITs.

Serial sections of representative Wnt1 transgene re-expressing and β-catmut relapsed tumors immunostained for Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) or Keratin-8, which recognize basal and luminal epithelial cells respectively. For both, brown pigment indicates positive staining. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Efforts to explain how some cancers stably maintain intratumoral lineage diversity typically invoke tumor cell hierarchies. Here, we show that cooperation between lineage-restricted subclones provides an alternative mechanism for maintaining tumor cell heterogeneity. In our Wnt models, we found evidence for both hierarchically and biclonally configured tumors, yet differently configured tumors were indistinguishable by histopathology, acquired equivalent cooperating HRasmut alleles (albeit with differences in tumor cell compartmentalization), and were comparably Wnt1-dependent. Thus, although distinct clonal configurations evolved, they converged toward analogous malignant phenotypes. These findings highlight the difficulties associated with inferring the clonal architecture of cancers from histopathology, even in the “simplified” context of mouse models. Notably, the Wnt models described here provide an experimentally tractable system for exploring whether and how a tumor’s clonal configuration determines its clinical behavior and curability.

Our study does not define when distinct subclones emerge in the course of tumor progression. Interclonal cooperation may be particularly prevalent in tumors initiated by aberrant expression of secreted signaling molecules, such as Wnt1 and PDGF30. In principle, germline mutations that impart a cancer predisposition also might bias tumors toward a biclonal configuration, since any subsequent cooperation-enabling mutations would necessarily accrue in a cell with mutant neighbors. As such, it will be important to determine whether interclonal cooperation can arise when initiating events originate in somatic cells or act primarily in a cell-intrinsic manner. If cooperation emerges as a common mechanism for maintaining subclone diversity in malignancies, this scenario would counter a key assumption made when interpreting cancer genome sequences. Specifically, certain mutations detected at low allelic fractions and commonly assumed to be late events in tumor progression, instead may be early events that enable interclonal cooperation.

Methods

Transgenic Mice

Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine rodent facility with access to water and chow ad libitum. All experimental protocols were approved by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The MMTV-Wnt1 (FVB.Cg-Tg(Wnt1)1Hev/J; stock #002934) and mRFP (B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-mRFP1)1F1Hadj/J; stock #005884) transgenic lines were obtained from the Jackson Labs. The MMTV-rtTA and tetO-Wnt1 transgenic lines were a gift from Dr. Lewis Chodosh. All mice either were generated in an inbred FVB/N background or were back-crossed 10 or more generations with FVB/N breeders before initiating experiments. Dox was administered by replacing standard mouse chow with chow containing 2g/kg Dox (Bio-serv). Genotyping was performed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tail clips and transgene specific primers (available upon request).

Cell Sorting

Mammary tumors were dissociated into single cell suspensions through mechanical separation and enzymatic digestion as described22. Dissociated tumor cells were enriched for Lin− (CD45−/ CD31−/ TER119−/ BP-1−) mammary epithelial cells with StemCell Technologies EasySep Mouse Epithelial Cell Enrichment Kits per the manufacturer’s instructions. Lin− cells were then incubated on ice for 20 min with anti-CD49f (α6 integrin) (BD Biosciences 555734) together with Alexafluor 647 (Invitrogen A21247) in PBS. Cells were spun down for 5 min at 550x g, then incubated with EpCAM-FITC conjugated antibody (Biolegend 118208) in PBS. Tumor cells were sorted on a BD FACS Aria cell sorter machine equipped with Diva software into their luminal (Lin−/ CD49flow/EpCAMhigh) and basal (Lin−/CD49fhigh/EpCAMlow) subpopulations. Sorted cells were collected into 15ml conical tubes containing PBS. Genomic DNA was collected from sorted cell populations using Qiagen Blood and Tissue DNeasy spin column kit. Total RNA was collected from sorted cell populations using Qiagen RNeasy spin column kit. RNA was reversed transcribed using Invitrogen Superscript II First Strand Synthesis kit.

Tumor reconstitution and propagation

In tumor reconstitution experiments, tumor cells for injection were counted using a hemocytometer and suspended at a concentration of 1000 cells/ul in a 50% Matrigel solution in PBS (BD Biosciences Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel Matrix). 105 cells in 100 ul of Matrigel solution were injected directly into intact #3 or #4 mammary fat pads of anesthetized adult female hosts, after using a small skin incision to expose the injection site. Incisions were closed with surgical clips. No randomization was performed since host mice were genetically identical, and no mice were excluded from analysis of tumor onset. Mice were monitored at least twice weekly for tumor growth by an investigator blinded to the tumor cell injection source. To generate a cohort of clonally related tumors for generating DITs, tumor fragments were explanted onto the flanks of wild-type Dox-treated host mice. Tumors were permitted to grow to a diameter of 8–10 mm, at which point mice received a single i.p. injection of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU) (Sigma 50mg/kg) to accelerate tumor relapse one week prior to Dox withdrawal. Without MNU treatment, only about a third of iWnt tumor explants relapsed during 12 months of continuous Dox withdrawal, and relapses arose after an average latency of 6 months. With MNU treatment, more than 90% of iWnt explants relapsed within 3 months of Dox withdrawal. Tumor regression and relapse was monitored at least twice weekly. Tumors were measured in two dimensions with calipers.

DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA or copy DNA isolated from tumor specimens or sorted tumor cell populations was amplified by PCR using gene specific primers (available upon request). PCR product was run out on an agarose gel, cut out and isolated using Qiagen QiaQuick Gel Isolation spin column kit. Samples were subjected to Sanger sequencing using gene specific primers on an ABI 3130XL Capillary sequencer machine. Sequence traces were analyzed using AB DNA Sequencing Analysis Software v5.2 and AB Sequence Scanner v1.0. Peak height (PH) on sequencing chromatograms was measured using ImageJ 1.46 software and HRas MAF was calculated using the following formula: MAF = PHMutant / (PHMutant + PHWild-type).

Immunofluorescence

Tumor samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde on ice for 2 hrs before being paraffin embedded. Paraffin sections (5um) were stained with antibodies for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and Keratin 8, which label basal and luminal epithelial cells, respectively. Primary antibodies used were: rabbit anti-SMA (AbCAM 5694, 1:250), and rat anti-Keratin 8 (Troma-I) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, 1:250). Secondary antibodies were: biotinylated rabbit-anti-rat IgG (Dako Cytomation E0468) and biotinylated rabbit IgG (Vector BA-1000). The fluorophore was a streptavidin fluorescein (Vector SA-5001). Hoechst-33342 dye (Invitrogen H1399) was used for nuclear DNA counterstaining, and slides were visualized using a Zeiss wide-field fluorescent microscope equipped with AxioVision 4.8 software.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was reversed transcribed using Invitrogen Superscript II First Strand Synthesis kit. We used Taqman Gene Expression Assay mix containing unlabeled PCR primers and a FAM-labeled Taqman probe to detect expression of the following genes: Wnt1 transgene (Applied Biosystems Mm01300555_g1), Keratin-8 (Applied Biosystems Mm00835759_m1), Gata3 (Applied Biosystems Mm00484683_m1), Muc1 (Applied Biosystems Mm00449604_m1), Keratin-5 (Applied Biosystems Mm00503549_m1), Keratin-14 (Applied Biosystems Mm00516876_m1), P-Cadherin (Applied Biosystems Mm01249209_m1), and Vimentin (Applied Biosystems Mm01333430_m1). Relative quantification Real-time PCR (ΔΔCt method) was performed in triplicate using Agilent Technologies Stratagene Mx3005P detection system and analyzed using Stratagene MxPro software. Gene expression levels in sorted cell populations were normalized to Gapdh transcript levels (Applied Biosystems 4352339E) and compared to the unsorted sample (relative expression=1).

Northern Hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from snap-frozen bulk tumor pieces by CsCl Density Gradient Centrifugation. Northern hybridization was performed as previously described28 using cDNA probes generated by RT-PCR. Primer pairs for probes are as follows: Wnt1, forward 5_-TGCGGTTCCTGTATTTTGC-3_ and reverse 5_-TGCATTCCTTTGGCGAGAGG-3_; Axin2, forward 5′-CCGAGCTCATCTCCAGGC-3′ and reverse 5′-GGACAGAGGCAGCGGACTC-3′; β-actin, forward 5′-TGAGACCTTCAACACCCCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGAGACCTTCAACACCCCAG-3′. After subcloning, the identity of each probe was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the benefactors of the Jake Gittlen Laboratories for Cancer Research and the following Penn State College of Medicine staff: Lynn Budgeon of the Gittlen Histology Core; Nate Sheaffer and Joseph Bednarczyk of the Flow Cytometry Core; David Stanford of the Molecular Genetics Core; and Jeanette Mohl of the Barrier Rodent Facility. This project was funded with grant support from the NIH/NCI and the Mary Kay Foundation. A.C. is supported by DOD pre-doctoral traineeship award W81XWH-11-1-0038.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions

A.C. designed and carried out experiments, interpreted data, and co-wrote the manuscript. T.L. and S.G. performed experiments, interpreted data, and provided commentary on the manuscript. E.G. designed experiments, interpreted data, and co-wrote the manuscript.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Shah SP, et al. Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2009;461:809–813. doi: 10.1038/nature08489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding L, et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature. 2010;464:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/nature08989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nik-Zainal S, et al. The life history of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149:994–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011;472:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu M, Pastor-Pareja JC, Xu T. Interaction between Ras(V12) and scribbled clones induces tumour growth and invasion. Nature. 2010;463:545–548. doi: 10.1038/nature08702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohsawa S, et al. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;490:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, et al. Evidence that transgenes encoding components of the Wnt signaling pathway preferentially induce mammary cancers from progenitor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:15853–15858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136825100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heppner GH. Cancer cell societies and tumor progression. Stem Cells. 1993;11:199–203. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530110306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axelrod R, Axelrod DE, Pienta KJ. Evolution of cooperation among tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:13474–13479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inda MM, et al. Tumor heterogeneity is an active process maintained by a mutant EGFR-induced cytokine circuit in glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1731–1745. doi: 10.1101/gad.1890510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calbo J, et al. A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park SY, Gonen M, Kim HJ, Michor F, Polyak K. Cellular and genetic diversity in the progression of in situ human breast carcinomas to an invasive phenotype. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:636–644. doi: 10.1172/JCI40724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navin N, et al. Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res. 2010;20:68–80. doi: 10.1101/gr.099622.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukamoto AS, Grosschedl R, Guzman RC, Parslow T, Varmus HE. Expression of the int-1 gene in transgenic mice is associated with mammary gland hyperplasia and adenocarcinomas in male and female mice. Cell. 1988;55:619–625. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90220-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu BY, McDermott SP, Khwaja SS, Alexander CM. The transforming activity of Wnt effectors correlates with their ability to induce the accumulation of mammary progenitor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4158–4163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400699101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho RW, et al. Isolation and molecular characterization of cancer stem cells in MMTV-Wnt-1 murine breast tumors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:364–371. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim S, Roopra A, Alexander CM. A phenotypic mouse model of basaloid breast tumors. PloS one. 2012;7:e30979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herschkowitz JI, et al. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome biology. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podsypanina K, Li Y, Varmus HE. Evolution of somatic mutations in mammary tumors in transgenic mice is influenced by the inherited genotype. BMC Med. 2004;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jang JW, Boxer RB, Chodosh LA. Isoform-specific ras activation and oncogene dependence during MYC- and Wnt-induced mammary tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8109–8121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00404-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S, Goel S, Alexander CM. Differentiation generates paracrine cell pairs that maintain basaloid mouse mammary tumors: proof of concept. PloS one. 2011;6:e19310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mester J, Wagenaar E, Sluyser M, Nusse R. Activation of int-1 and int-2 mammary oncogenes in hormone-dependent and -independent mammary tumors of GR mice. J Virol. 1987;61:1073–1078. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.1073-1078.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roelink H, Wagenaar E, Nusse R. Amplification and proviral activation of several Wnt genes during progression and clonal variation of mouse mammary tumors. Oncogene. 1992;7:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunther EJ, et al. Impact of p53 loss on reversal and recurrence of conditional Wnt-induced tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:488–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1051603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Debies MT, et al. Tumor escape in a Wnt1-dependent mouse breast cancer model is enabled by p19Arf/p53 pathway lesions but not p16 Ink4a loss. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:51–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI33320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podsypanina K, Politi K, Beverly LJ, Varmus HE. Oncogene cooperation in tumor maintenance and tumor recurrence in mouse mammary tumors induced by Myc and mutant Kras. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:5242–5247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801197105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fomchenko EI, et al. Recruited cells can become transformed and overtake PDGF-induced murine gliomas in vivo during tumor progression. PloS one. 2011;6:e20605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]