Abstract

Anxiety-related disorders are among the most common psychiatric illnesses, thought to have both genetic and environmental causes. Early-life trauma, such as abuse from a caregiver, can be predictable or unpredictable, each resulting in increased prevalence and severity of a unique set of disorders. In this study, we examined the influence of early unpredictable trauma on both the behavioral expression of adult anxiety and gene expression within the amygdala. Neonatal rats were exposed to unpaired odor-shock conditioning for 5 days, which produces deficits in adult behavior and amygdala dysfunction. In adulthood, we used the Light/Dark box test to measure anxiety-related behaviors, measuring the latency to enter the lit area and quantified urination and defecation. The amygdala was then dissected and a microarray analysis was performed to examine changes in gene expression. Animals that had received early unpredictable trauma displayed significantly longer latencies to enter the lit area and more defecation and urination. The microarray analysis revealed over-represented genes related to learning and memory, synaptic transmission and trans-membrane transport. Gene ontology and pathway analysis identified highly represented disease states related to anxiety phenotypes, including social anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorders, PTSD and bipolar disorder. Addiction related genes were also overrepresented in this analysis. Unpredictable shock during early development increased anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood with concomitant changes in genes related to neurotransmission, resulting in gene expression patterns similar to anxiety-related psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: unpredictable, early life, stress, anxiety, microarray, rodent

1.0 Introduction

Anxiety or fear-related disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobic or obsessive compulsive disorders are among the most common psychiatric illnesses reported, with about one third of the population experiencing symptoms in their lifetime. Anxiety disorders are thought to have both genetic and environmental causes (Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Charney and Drevets, 2002; Kessler et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2007; Norrholm and Kessler, 2009). Clinical studies have shown that early-life trauma, such as an abusive relationship with a caregiver results in an increased prevalence and severity of these fear-disorders throughout the lifetime (Famularo et al., 1992; Newman et al., 1996; Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Anderson, 2003; Costello et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2007; Gartstein et al., 2010). Examining adverse experience in animals allows for control over many variables, therefore providing necessary information on the causal effects of this manipulation on adult behavior and avenues for treatment. Thus, our lab and others model early life adversity by subjecting neonates to early life stressors, such as prolonged maternal separation or shock. These paradigms have resulted in heightened emotionality and anxiety in the adult (Wigger and Neumann, 1999; Huot et al., 2001; Meaney, 2001; Kalinichev et al., 2002; Price and Feldon, 2003; Koston et al., 2006; Sevelinges et al., 2007; Moriceau et al., 2009).

Manipulations of early trauma can be either predictable or unpredictable to the infant; each resulting in a unique set of disorders. While, predictable trauma, such as the temporal linking of a stimulus with a shock, disrupts the development of numerous cognitive processes and results in the enhanced expression of depressive-like behaviors (Sevelinges et al., 2011; Raineki et al., 2012), unpredictable trauma, such as a shock that is not linked in time to a specific stimulus, also disrupts normal developmental cognitive processes and leads to an enhanced expression of later life anxiety behaviors (Levine et al., 1956; Fride and Weinstock, 1984; Tyler et al., 2007; Bondi et al., 2008; Franklin et al., 2011). Anxiety, the focus of this manuscript, is often defined as the feeling of worry, nervousness, or unease and is typically about a threat or something with an uncertain outcome. Thus in this study, we were specifically interested in examining the influence of early unpredictable trauma on the expression of adult anxiety and asked which phenotypic changes within the amygdala nuclei were altered by that trauma and associated with anxiety.

It is well established that the amygdala, a complex set of nuclei, well positioned between systems of sensory input and those of motor output, is vital for the learning and expression of threat, anxiety, and other forms of emotionality (Charney and Drevets, 2002; Rodrigues et al., 2009). For example, manipulations of early life experience, such as early trauma, have been shown to alter amygdala function and amygdala-dependent behaviors in adulthood (Sevelinges et al., 2007; Sevelinges et al., 2008; Moriceau et al., 2009; Raineki et al., 2009; Landers and Sullivan, 2012). Predictable trauma, (i.e., odor-shock conditioning during early development), leads to both depressive-like behaviors as well as altered amygdala function (Sevelinges et al., 2011; Raineki et al., 2012). Moreover, experiences during early development, such as altering the quality of maternal care, induce changes in gene transcription that continue throughout the lifespan and promote changes to physiological and behavioral measures, such as the physiological response to stress (Meaney, 2001; Roth and Sweatt, 2011). This suggests that specific alterations in gene transcription within the amygdala may underlie the behavioral effect of early unpredictable trauma on the expression of anxiety in adults. While links between unpredictable early life stress and protein expression in the amygdala have been suggested (Weiss et al., 2011), the specific influence of unpredictable early life stress on the broad phenotypic expression within the amygdala and its relationship to anxiety-like behaviors is currently not known.

In the current study, we assessed whether unpredictable early life stress produces a long-term effect on adult anxiety-related behaviors and asked whether this manipulation changes the expression of specific genes within the amygdala. To explore this, neonatal rats (PN8) were exposed to a treatment that simulated unpredictable trauma (i.e., unpaired odor-shock conditioning) for 5 consecutive days. We have previously shown this to produce modified amygdala-dependent anxiety-like behavior in adults (Tyler et al., 2007). We tested for anxiety-related behaviors in adults that had experienced either unpredictable early life trauma or a normal developmental experience. We then conducted a broad screen of possible phenotypic related changes within the amygdala in a separate cohort of adults after an identical developmental experience. We show that unpredictable trauma in early life leads to heightened anxiety in adulthood and long lasting changes to gene expression. These changes were both broad in scope and specific to particular receptors and disease states.

2.0 Methods and Materials

2.1 Subjects

We used male Long-Evans rats born and bred in our colony (originally from Harlan Labs). Animals were housed in polypropylene cages (34 × 29 × 17 cm) with an abundant amount of wood shavings for nest building, and kept in a 20°C environment with a 12:12 light-dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. The day of birth was considered Postnatal day (PN) 0 and litters were culled to 12 pups (6 males and 6 females) on PN1. To preclude litter effects, only 1–2 animals per litter were assigned to each experimental group and each litter was equally represented across groups. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal care and experimental procedures, which follow the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health.

2.2 Infant experience

Beginning at PN8, pups were exposed to either an odor unpaired with an electric shock or an odor alone, daily for 5 consecutive days. Pups were placed in individual 600mL beakers and were given a 10 min acclimation period prior to conditioning to recover from experimental handling. During a conditioning session, unpaired pups (n = 6–8) received 11 presentations of a 30 sec peppermint odor (McCormick & Co Inc) and an explicitly unpaired 0.5mA hindlimb shock occurring for 1 sec. The odor was delivered by a flow dilution olfactometer (2 liters/min flow rate) at a concentration of 1:10 peppermint vapor to air every 4 min for all pups. After unpaired conditioning, pups were returned to the home cage. Control animals (n = 6) received similar treatment, but were only exposed to the odor and did not receive a shock.

2.3 Behavioral testing

2.3.1 Adult Light/Dark box

We used this test to measure anxiety-related behaviors, which capitalizes on rodents’ avoidance of brightly illuminated areas and exploratory activity (Crawley, 1985). Both unpaired and control animals (n = 6/group) were tested as adults (~3 months old). Anxiety is assumed to be high when the latency to enter the light box is high. The plastic apparatus (53 cm long · 12 cm wide · 18 cm height) was equally divided into 2 compartments by a sliding door: one compartment was painted black and shut-off from all light while the light, larger compartment was painted white and brightly lit (each compartment was 26.5 cm long · 12 cm wide · 18 cm height). The rat was placed in the dark box for a 1 min to habituate before the door separating the dark and light boxes was opened providing the animal with a 10 min exploration period. The latency to enter the light box was recorded. Rats were considered to have entered the light compartment when the rat’s entire body had passed the separation between the two compartments. We also recorded urination and defecation from each animal during the testing period. Observers were blind to the prior infant condition. Behavioral data were analyzed by paired t-tests. Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

2.4 Amygdala Dissection

In a separate cohort of animals (~3 months of age; n = 8/group), not tested for anxiety, both amygdala were dissected on ice, flash frozen and stored at −80° C. The amygdala was located using the ventral hippocampus and putamen as landmarks for the rostral and caudal cuts, respectively. The brain was turned to obtain a coronal view, where the rhinal fissure could be easily seen and used as a landmark to make the dorsal cut. The remaining cortex on the lateral side is lifted off the amygdala while the optic track was used to make the medial cut.

2.5 Microarray assessment

2.5.1 Tissue processing

The dissected amygdala tissue was processed for total RNA (Qiagen RNeasy Micro Kit). RNA was extracted using elution columns; residual buffers and enzymes were removed. mRNA was amplified linearly, and hybridized to Affymetrix rat 2.0 chips, as specified by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) and NuGEN (San Carlos, CA) (Pico system).

2.5.2 Data processing

Raw data were preprocessed, background-corrected, and normalized by GCRMA (Wu and Irizarry, 2004). The number of genes was filtered to approximately 12,000 by eliminating probe sets that did not vary across conditions (variance filtering) or for which there was no available annotation. The first step defined differentially expressed probe sets. To accomplish this, we used Rank Products (Breitling et al., 2004), which simulates probabilities based on pairwise comparison differences. From these results, we determined the percentage of differentially regulated genes fit into different biological and cellular GO categories [Panther; (Mi et al., 2013)].

Because consistent changes, even if small, are likely more important than changes in individual genes, we used additional methods to determine functional classifications. We were interested in functional pathways that were altered by the unpaired shock and we selected all probes whose fold changes were >±1.25 and entered them in DAVID for Gene Ontology functional classification (Huang da et al., 2009; Huang da et al., 2009). Up- and downregulated genes (45 and 143 respectively) were analyzed separately given the differences in GO categories in the Panther analysis. Of those Gene ontology categories, we chose categories with a fold enrichment >2.0 and a corrected probability (FDR)<10% for follow-up.

2.5.3 Pathway analysis

To determine pathways involved in the adult amygdala, we used Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, www.ingenuity.com) to define networks from the top 100 up- and top 100 down-regulated probes ordered by fold change. We included up- and downregulated genes together because the analytic methods in IPA generates pathways from both. Each identifier was mapped to its corresponding object by using the “direct connection” option in Ingenuity’s Knowledge Base. The IPA Functional Analysis identifies the biological functions most significant to the dataset. For each dataset analyzed in this manner, predefined canonical pathways were identified from the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis library. The significance of the association between the data set and the canonical pathway was measured by Fisher’s exact test for the probability that the association between the genes in the dataset and the canonical pathway was not by chance (Ingenuity Systems, 2009, www.ingenuity.com). For descriptive purposes and for clarity of presentation we show canonical paths and disease states typical of those paths.

3.0 Results

3.1 Behavior

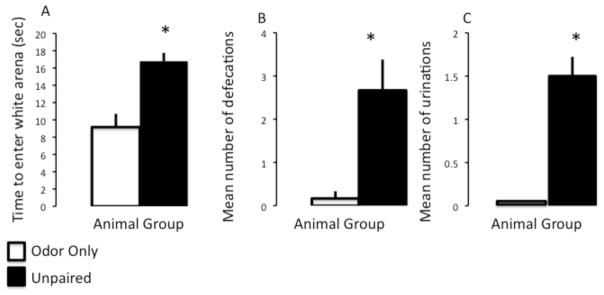

We first asked whether early life trauma (i.e., unpredicted shock) leads to heightened anxiety-like behavior in adulthood. To do so, we measured the latency of when animals entered the light compartment from the dark area in a testing arena (Light/dark box- see Methods) (n = 6/group). Those animals that had received unpaired odor-shock treatment as neonates displayed significantly longer latencies to enter the light area (Figure 1A; control: 9.17 ±1.54 vs. Unpaired: 16.79 ± 2.67; t-test: t = −4.2, p = 0.002). Furthermore, Unpaired animals also displayed significantly more numbers of defecations and urinations during the testing period than control animals (Figure 1B, defecations: control: 0.17 ± 0.17 vs. Unpaired: 2.67 ± 0.71; t-test: t = −3.41, p = 0.007; Figure 1C, urinations: control: 0 ± 0 vs. Unpaired: 1.5 ± 0.22; t-test: t = −6.71, p = 0.001). Longer latency to enter the light area of the testing arena as well as increased numbers of defecations and urinations suggest that those animals exposed to unpredictable shock during early development displayed increased anxiety-like behavior in adulthood. These results replicate and extend an earlier finding that long term anxiety-like behaviors are a result of unpredictable early-life shock. Importantly, predictable shock does not have this effect on these measures (Tyler et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Animals with early-life unpredictable trauma display enhanced levels of anxiety-like behaviors in adult hood. A: Animals with unpaired odor shock conditioning (solid bar) displayed a higher latency to enter an illuminated arena as well as higher numbers of defecations (B) and urinations (C) during a testing session than Odor only (control) animals (open bar). Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05.

3.2 Amygdala microarray assessment

3.2.1 Differential expression

Ranked products showed 64 genes differentially regulated by the neonatal treatment at pfp<.05 and 85 at pfp<.10 (pfp: percentage of false predictions). These are shown in Table 1. At the 5% pfp level, 50 were downregulated and 14 were upregulated. At the 10% pfp level, 65 were downregulated and 20 were upregulated. Thus, at all levels of significance, and for all subsequent analyses, gene expression overall was more suppressed than increased.

Table 1.

Significant gene probes from the Rank Product analysis

| Gene_ID | Symbol | C hr | Title | Min pfp | Fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 81512 | Lect1 | 15 | leukocyte cell derived chemotaxin 1 | 0 | −1.8636 |

| 315597 | Mfrp | 8 | membrane frizzled-related protein | 0 | −1.7864 |

| 80900 | Slco1a5 | 4 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 | 0 | −1.7307 |

| 300920 | Cldn2 | X | claudin 2 | 0 | −1.682 |

| 309100 | Scgb1c1 | 1 | secretoglobin, family 1C, member 1 | 0 | −1.6801 |

| 304929 | F5 | 13 | coagulation factor V (proaccelerin, labile factor) | 0 | −1.5717 |

| 84386 | Slpi | 3 | secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor | 0.001 | −1.5834 |

| 266803 | Sostdc1 | 6 | sclerostin domain containing 1 | 0.0011 | −1.6735 |

| 305858 | Otx2 | 15 | orthodenticle homeobox 2 | 0.0013 | −1.7561 |

| 57395 | Tmem27 | X | transmembrane protein 27 | 0.0014 | −1.624 |

| 25250 | Cox8b | 1 | cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIIIb | 0.0015 | −1.5842 |

| 100359478 | LOC100359478 | 13 | rCG20339-like | 0.0017 | −1.5832 |

| 24659 | Pmch | 7 | pro-melanin-concentrating hormone | 0.0018 | −1.4926 |

| 304021 | Col8a1 | 11 | collagen, type VIII, alpha 1 | 0.0019 | −1.4486 |

| 84024 | Pon1 | 4 | paraoxonase 1 | 0.002 | −1.4103 |

| 500945 | RGD1561795 | 8 | similar to RIKEN cDNA 1700012B09 | 0.0021 | −1.5813 |

| 295462 | Ccdc109b | 2 | coiled-coil domain containing 109B | 0.0035 | −1.4561 |

| 25258 | Glycam1 | 7 | glycosylation dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 | 0.0035 | −1.3865 |

| 56824 | Ifit1 | 1 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 0.0037 | −1.474 |

| 360613 | Ccdc49 | 10 | coiled-coil domain containing 49 | 0.0039 | −1.2299 |

| 297738 | Steap1 | 4 | six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1 | 0.0043 | −1.3824 |

| 83504 | Kl | 12 | Klotho | 0.0043 | −1.3616 |

| 24203 | Amy1a | 2 | amylase, alpha 1A (salivary) | 0.0045 | −1.4718 |

| 286918 | Mx2 | 11 | myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 | 0.0072 | −1.2404 |

| 29354 | Pla2g5 | 5 | phospholipase A2, group V | 0.0075 | −1.3488 |

| 312677 | Ccdc77 | 4 | coiled-coil domain containing 77 | 0.0081 | −1.5577 |

| 25240 | Aqp1 | 4 | aquaporin 1 | 0.0085 | −1.382 |

| 25400 | Camk2a | 18 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha | 0.01 | 1.3171 |

| 25049 | Atxn1 | 17 | ataxin 1 | 0.01 | 1.4662 |

| 293154 | Folr2 | 1 | folate receptor 2 (fetal) | 0.0107 | −1.3013 |

| 310707 | Chd1l | 2 | chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 1-like | 0.012 | 1.3325 |

| 315820 | Myo5c | 8 | myosin VC | 0.0131 | −1.3772 |

| 85327 | Lin7a | 7 | lin-7 homolog a (C. elegans) | 0.0138 | 1.5181 |

| 310836 | Abca4 | 2 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily A (ABC1), member 4 | 0.0147 | −1.2854 |

| 65153 | Freq | 3 | frequenin homolog (Drosophila) | 0.015 | 1.2456 |

| 171049 | Folr1 | 1 | folate receptor 1 (adult) | 0.0155 | −1.2226 |

| 366140 | Fjx1 | 3 | four jointed box 1 (Drosophila) | 0.0157 | 1.6088 |

| 24856 | Ttr | 18 | transthyretin | 0.0167 | −1.6577 |

| 83502 | Cdh1 | 19 | cadherin 1 | 0.0167 | 1.4029 |

| 308958 | Cdr2 | 1 | cerebellar degeneration-related 2 | 0.0169 | −1.4405 |

| 311491 | RGD1308385 | 3 | similar to RIKEN cDNA 1700010M22 | 0.0182 | −1.3839 |

| 361394 | Lrrc36 | 19 | leucine rich repeat containing 36 | 0.02 | −1.3778 |

| 308565 | Klk8 | 1 | kallikrein related-peptidase 8 | 0.02 | 1.4348 |

| 366035 | Wdr38 | 3 | WD repeat domain 38 | 0.0206 | −1.3965 |

| 50872 | Hpcal4 | 5 | hippocalcin-like 4 | 0.0227 | 1.4617 |

| 79247 | Htr5b | 13 | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 5B | 0.025 | 1.3337 |

| 84493 | Fmo3 | 13 | flavin containing monooxygenase 3 | 0.0278 | 1.3849 |

| 24310 | Ace | 10 | angiotensin I converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 1 | 0.0305 | −1.3355 |

| 362879 | RGD1562127 | 7 | similar to chromosome 11 open reading frame 9 | 0.0313 | −1.397 |

| 690286 | LOC690286 | 10 | similar to hepatic leukemia factor | 0.0342 | 1.1494 |

| 25504 | Oxt | 3 | oxytocin, prepropeptide | 0.0355 | −1.5973 |

| 689043 | Fam19a4 | 4 | family with sequence similarity 19 (chemokine (C-C motif)-like), member A4 | 0.0362 | −1.5561 |

| 294806 | C1qtnf3 | 2 | C1q and tumor necrosis factor related protein 3 | 0.0368 | −1.2763 |

| 362285 | Col9a3 | 3 | procollagen, type IX, alpha 3 | 0.0424 | −1.3996 |

| 24684 | Prlr | 2 | prolactin receptor | 0.0433 | −1.1666 |

| 292843 | Siglec5 | 1 | sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin 5 | 0.0433 | −1.1592 |

| 309400 | Tmem2 | 1 | transmembrane protein 2 | 0.0433 | −1.1039 |

| 25365 | Actg2 | 4 | actin, gamma 2, smooth muscle, enteric | 0.0436 | −1.1241 |

| 308794 | RGD1310371 | 1 | similar to RIKEN cDNA 1700026D08 | 0.0438 | −1.4482 |

| 304667 | Rtbdn | 19 | retbindin | 0.0439 | −1.3039 |

| 293624 | Irf7 | 1 | interferon regulatory factor 7 | 0.0441 | −1.3866 |

| 499017 | Sytl3 | 1 | synaptotagmin-like 3 | 0.0443 | −1.3515 |

| 50658 | Mapk9 | 10 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 9 | 0.0457 | 1.247 |

| 300663 | Ccdc153 | 8 | coiled-coil domain containing 153 | 0.0478 | −1.3664 |

| 498944 | Tsnaxip1 | 19 | translin-associated factor X interacting protein 1 | 0.0485 | −1.4034 |

| 64030 | Kit | 14 | v-kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 feline sarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 0.0485 | 1.2012 |

| 307562 | Dsg2 | 18 | desmoglein 2 | 0.0553 | −1.3039 |

| 362424 | Tmem72 | 4 | transmembrane protein 72 | 0.0563 | −1.2332 |

| 306454 | Cldn22 | 16 | claudin 22 | 0.057 | −1.3355 |

| 681124 | Dnase1l2 | 10 | deoxyribonuclease 1-like 2 | 0.0586 | −1.3381 |

| 171138 | Kcne2 | 11 | potassium voltage-gated channel, Isk-related subfamily, gene 2 | 0.0589 | −1.1843 |

| 171026 | Akap5 | 6 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 5 | 0.0606 | 1.3613 |

| 117019 | Eif2b4 | 6 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B, subunit 4 delta | 0.0607 | −1.3816 |

| 116455 | Atp6v0a2 | 12 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal V0 subunit A2 | 0.0633 | 1.3328 |

| 85496 | Enpp1 | 1 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 | 0.0644 | 1.2997 |

| 498278 | RGD1562658 | 13 | similar to RIKEN cDNA 1700009P17 | 0.0653 | −1.3344 |

| 291084 | Nqo2 | 17 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 2 | 0.0656 | −1.3615 |

| 290595 | LOC290595 | 16 | hypothetical gene supported by AF152002 | 0.0658 | −1.215 |

| 290372 | RGD1560137 | 15 | similar to expressed sequence AU021034 | 0.0665 | −1.3229 |

| 311061 | Itgb6 | 3 | integrin, beta 6 | 0.0674 | −1.1521 |

| 100147704 | Usp43_predicted | 10 | ubiquitin specific protease 43 | 0.077 | −1.3302 |

| 498642 | Rbpms | 16 | RNA binding protein with multiple splicing | 0.0779 | −1.3107 |

| 312790 | Gprc5a | 4 | G protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 5, member A | 0.0804 | −1.3111 |

| 288562 | Tfr2 | 12 | transferrin receptor 2 | 0.0825 | −1.3336 |

| 297595 | Leprel2 | 4 | leprecan-like 2 | 0.0901 | −1.2675 |

| 84020 | Kcnq1 | 1 | potassium voltage-gated channel, KQT-like subfamily, member 1 | 0.0901 | −1.2511 |

| 362336 | Fam180a | 4 | family with sequence similarity 180, member A | 0.0955 | 1.229 |

| 315691 | Lingo1 | 8 | leucine rich repeat and Ig domain containing 1 | 0.0956 | 1.1121 |

| 64536 | Esm1 | 2 | endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | 0.0975 | −1.2597 |

| 680802 | LOC680802 | 1 | similar to Zinc finger protein 45 (BRC1744) | 0.0989 | 1.2272 |

Note: Pfp is the percentage of false predictions

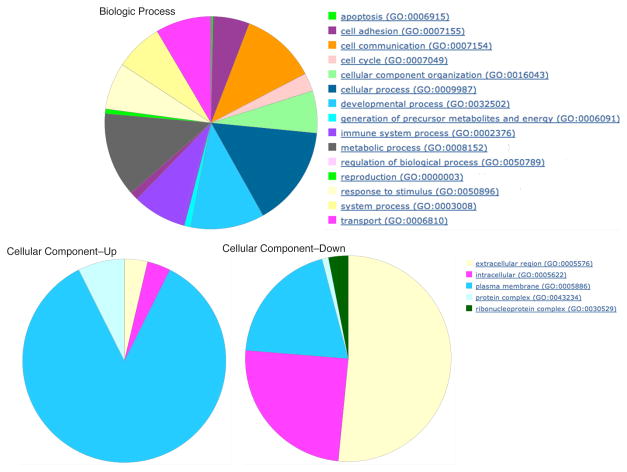

3.2.2 Gene Ontology categorization

We used Gene Ontology to classify genes by their Biological Processes and Cellular Components. For the former, most genes were classified as metabolic process, cellular communication, or cellular process. Fewer, although still a substantial proportion, were transport genes, homeostatic processes, or immune system processes. These proportions were similar for up- and downregulated genes (Figure 2a). However, when the Cellular Component class was analyzed, the direction of regulation was important. Upregulated genes were located almost exclusively at the cell junction of the plasma membrane. In contrast, downregulated genes were largely in the extracellular matrix (> 50%), and with about 25% each additionally that were intracellular or on the plasma membrane (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Gene Ontology categories for biologic and cellular function for genes that were differentially regulated (Rank Products, pfp<.05). For the biologic function (top), there were a number categories represented including cell communication, cellular processes, developmental processes, and metabolic processes. The classification for biologic function was virtually identical for up- and down regulated genes. For cellular processes (bottom), however, the direction of regulation was important. Upregulated genes were largely located on the plasma membrane whereas downregulated genes were largely extracellular.

The results of the functional annotation analysis by DAVID represent functional similarities between genes, used to identify salient ontological categories. We focused only on the Biological Process and the Cellular Component of the Gene Ontology database. For the upregulated probesets, three different pathways were apparent and we examined those at the most specific level of analysis. Probes that are within each Gene ontology category that met the criteria specified above (fold enrichment >2.0 and a corrected probability (FDR)<10%) were integrated into the Gene ontology clusters (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Upregulated Biological and Cell Component Classes

| Symbol | Gene ID | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|

| AKAP5 | 171026 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 5 |

| ARF5 | 79117 | ADP-ribosylation factor 5 |

| ATXN1 | 25049 | ataxin 1 |

| CADM3 | 360882 | cell adhesion molecule 3 |

| CAMK2A | 25400 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha |

| CAMK2N1 | 287005 | calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II inhibitor 1 |

| CDH1 | 83502 | cadherin 1 |

| CLSTN3 | 171393 | calsyntenin 3 |

| DDR1 | 25678 | discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinase 1 |

| DLG4 | 29495 | discs, large homolog 4 (Drosophila) |

| EHD3 | 315499 | similar to EH-domain containing 3; EH-domain containing 3 |

| EHD3 | 192249 | similar to EH-domain containing 3; EH-domain containing 3 |

| ENPP1 | 85496 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 |

| EPN1 | 117277 | Epsin 1 |

| FBXO10 | 362511 | F-box protein 10 |

| GABRB3 | 24922 | gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, beta 3 |

| HTR2A | 29595 | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2A |

| HTR3A | 79246 | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 3a |

| HTR5B | 79247 | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 5B |

| KCNJ4 | 116649 | potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 4 |

| KLK8 | 308565 | kallikrein related-peptidase 8 |

| LIN7A | 85327 | lin-7 homolog a (C. elegans) |

| MSLN | 60333 | mesothelin |

| SERPINF1 | 287526 | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade F, member 1 |

| SLC6A13 | 171163 | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, GABA), member 13 |

| SLC6A20 | 113918 | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 20 |

| TRH | 25569 | thyrotropin releasing hormone |

| UNC5A | 60629 | unc-5 homolog A (C. elegans) |

| WFS1 | 83725 | Wolfram syndrome 1 homolog (human) |

Table 3.

Down regulated Biological and Cell Component Classes

| ACE | 24310 | angiotensin I converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 1 | |

| ALDH1A1 | 24188 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A1 | |

| AQP1 | 25240 | aquaporin 1 | |

| AVP | 24221 | arginine vasopressin | |

| CAR9 | 313495 | carbonic anhydrase 9 | |

| CGA | 116700 | glycoprotein hormones, alpha subunit | |

| COL2A1 | 25412 | collagen, type II, alpha 1 | |

| COL8A1 | 304021 | collagen, type VIII, alpha 1 | |

| EIF2B4 | 117019 | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2B, subunit 4 delta | |

| F5 | 304929 | coagulation factor V (proaccelerin, labile factor) | |

| FOXA2 | 25099 | forkhead box A2 | |

| GBX2 | 114500 | gastrulation brain homeobox 2 | |

| GNG8 | 245986 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), gamma 8 | |

| GRM4 | 24417 | glutamate receptor, metabotropic 4 | |

| HSF4 | 291960 | heat shock transcription factor 4 | |

| IRX5 | 498918 | iroquois homeobox 5 | |

| KRT8 | 25626 | keratin 8 | |

| NQO2 | 291084 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 2 | |

| OTX2 | 305858 | orthodenticle homolog 2 (Drosophila) | |

| OXT | 25504 | oxytocin, prepropeptide | |

| PLA2G5 | 29354 | phospholipase A2, group V | |

| PMCH | 24659 | pro-melanin-concentrating hormone | |

| SHOX2 | 25546 | short stature homeobox 2 | |

| SLC27A2 | 65192 | solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member 2 | |

| SLCO1A5 | 80900 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 | |

| STEAP2 | 312052 | six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 2 | |

| SYTL3 | 499017 | synaptotagmin-like 3 | |

| TH | 25085 | tyrosine hydroxylase | |

| UCN | 29151 | urocortin | |

| ACE | 394682 | angiotensin I converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 1 | |

| AMY1A | 392205 | amylase, alpha 1A (salivary) | |

| AQP1 | 411355 | aquaporin 1 | |

| AVP | 409168 | arginine vasopressin | |

| CAR9 | 409305 | carbonic anhydrase 9 | |

| CGA | 383810 | glycoprotein hormones, alpha subunit | |

| CLDN2 | 380225 | claudin 2 | |

| CLEC1B | 407692 | C-type lectin domain family 1, member b | |

| COL2A1 | 413871 | collagen, type II, alpha 1 | |

| CTHRC1 | 406161 | collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 | |

| DSG2 | 400958 | desmoglein 2 | |

| DYSF | 407472 | dysferlin | |

| ENPP2 | 397475 | ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 2 | |

| ESM1 | 403943 | endothelial cell-specific molecule 1 | |

| F5 | 392715 | coagulation factor V (proaccelerin, labile factor) | |

| GLYCAM1 | 393551 | glycosylation dependent cell adhesion molecule 1 | |

| GNG8 | 392668 | guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), gamma 8 | |

| GRM4 | 385400 | glutamate receptor, metabotropic 4 | |

| HGS | 396973 | hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate | |

| KCNQ1 | 418114 | potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily Q, member 1 | |

| KL | 417041 | Klotho | |

| KLK6 | 404136 | kallikrein related-peptidase 6 | |

| KRT8 | 416397 | keratin 8 | |

| LECT1 | 414983 | leukocyte cell derived chemotaxin 1 | |

| OXT | 408924 | oxytocin, prepropeptide | |

| P2RX6 | 393457 | purinergic receptor P2X, ligand-gated ion channel, 6 | |

| PLA2G5 | 417130 | phospholipase A2, group V | |

| PMCH | 399481 | pro-melanin-concentrating hormone | |

| PON1 | 381133 | paraoxonase 1 | |

| PRPH | 402974 | peripherin | |

| RNASE12 | 388854 | ribonuclease, RNase A family, 12 (non-active) | |

| SCGB1C1 | 397101 | secretoglobin, family 1C, member 1 | |

| SCN2A1 | 399606 | sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, alpha 1 | |

| SCN4B | 380233 | sodium channel, type IV, beta | |

| SGMS2 | 407500 | sphingomyelin synthase 2 | |

| SLC5A11 | 406299 | solute carrier family 5 (sodium/glucose cotransporter), member 11 | |

| SLCO1A5 | 383300 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1a5 | |

| SLPI | 405412 | secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor | |

| SOSTDC1 | 400391 | sclerostin domain containing 1 | |

| STEAP2 | 413664 | six transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 2 | |

| SYTL3 | 394843 | synaptotagmin-like 3 | |

| TFR2 | 397885 | transferrin receptor 2 | |

| TH | 404368 | tyrosine hydroxylase | |

| TTR | 403842 | transthyretin | |

| UCN | 403129 | urocortin | |

| VAV3 | 403653 | vav 3 guanine nucleotide exchange factor | |

| VIPR2 | 409436 | vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 2 | |

| VOM2R31 | 394357 | vomeronasal 2 receptor, 31 | |

| XCL1 | 394484 | chemokine (C motif) ligand 1 | |

3.2.3 Upregulated probesets

The three paths were “cell adhesion/synaptic transmission”, “serotonin/neurotransmitter regulation”, and “affective behavior” (Table 4). The first, synaptic transmission, includes genes with clearly defined neurotransmitter/modulator function that regulate synaptic transmission. In some cases these have effects on specific transmitters (e.g. dlg4, which binds NMDA receptors. In most cases, however, the effects of these genes are more global (e.g. cadm3, cdh1, clstn3, kcnj4 and klk8) and affect many systems. The second class identified probes more specific to transmission processes including serotonin and GABA. Three 5HT receptors were upregulated, as well as a GABA receptor subunit and a GABA transporter that is widely distributed on neurons, astrocytes and other cells. Overall, many of the upregulated genes are implicated in anxiety. Finally, three probesets that were upregulated in the 3rd GO category have strong roles in fear and anxiety, including AKAP5, which has polymorphisms that contribute to affective phenotypes in human patient populations.

Table 4.

Functional Annotation Clusters from DAVID for Upregulated genes

| Gene Group 1. Cell Adhesion, Synaptic Transmission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Name | Putative function* | Fold |

| Cadm3 | cell adhesion molecule 3 | Brain specific Ca2+independent adhesion molecule involved in the formation of synapses, axon bundles and myelinated axons | 1.29 |

| Cdh1 | cadherin 1 | Regulates neuron projection growth via cadherin signaling pathway; Cdh1 cKO mice had impaired associative fear memory and exhibited impaired long-term potentiation (LTP) in amygdala slices. (Pick et al., 2013) | 1.40 |

| Clstn3 | calsyntenin 3 | Thought to be involved in signal transduction processes as vesicular trafficking protein in the brain that can couple synaptic vesicle exocytosis to neuronal cell adhesion. | 1.28 |

| Dlg4 | discs, large homolog 4 | Scaffolding protein that binds and clusters NMDA receptors at neuronal synapses; DLG4 gene disruption in mice produces a complex range of behavioral and molecular abnormalities relevant to autism spectrum disorders and Williams’ syndrome. (Feyder et al., 2010) | 1.28 |

| Kcnj4 | potassium inwardly- rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 4 | Forebrain specific with a key role in neuronal signaling by regulation of the excitability of neurons | 1.35 |

| Klk8 (neuropsin) | kallikrein related- peptidase 8 | A extracellular protease, mediates activity-dependent synaptic change required for hippocampal LTP (Ishikawa et al., 2011) | 1.43 |

| Gene Group 2. Serotonin/neurotransmitter Regulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Name | Putative function* | Fold |

| Gabrb3 | gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, beta 3 | Beta 3 subunit, with alpha subunits forms active GABA-A receptors | 1.28 |

| Htr2a | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2a | Linked to anxiety/affective disorders | 1.26 |

| Htr3a | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 3a | Ligand gated pre- and postsynaptic receptor implicated in anxiety disorders and IBS | 1.29 |

| Htr5b | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 5B | G-protein coupled receptor co-expressed with the 5-HT transporter in dorsal raphe. | 1.33 |

| Slc6a13 | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter, GABA), member 13 | GABA transporter (GAT2) on neurons and astrocytes | 1.27 |

| Slc6a20 | solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 20 | Amino acid transporter as part of the IMINO system. Regulates extracellular proline levels | 1.27 |

| Trh | Thyrotropin releasing hormone | Strongly implicated in anxiety, particularly in the amygdala | 1.33 |

| Gene Group 3. Other Genes implicated in Affective behaviors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Name | Putative Function* | Fold |

| AKAP5 | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 5 | AKAP5 Pro100Leu polymorphism (rs2230491) contributes to individual differences in affective control (Richter et al., 2013) | 1.36 |

| CAMK2A | calcium/calmodulin- dependent protein kinase II alpha | Significant for retrieval of fear conditioning with NMDA 2A receptors in amygdala; (Moriya et al., 2000) | 1.32 |

| WFS1 | Wolfram syndrome 1 homolog (human | Negatively related to anxiety phenotype in mice | 1.32 |

From NIH and RGD databases and the cited literature.

3.2.4 Downregulated probesets

Downregulated probes consisted of neuromodulators that play a role in social behavior. Oxytocin and vasopressin are conserved genes that have long been hypothesized to regulate a variety of homeostatic functions including regulation of stress, sexual, maternal, and social interactions [for reviews, see (Neumann and Landgraf, 2012; Goodson, 2013; Goodson and Kingsbury, 2013)]. Pro-melanin-concentrating hormone has a role in many homeostatic processes and reduced angiotensin 1 converting enzyme is anxiogenic (PMID (Okuyama et al., 1999)). The second gene group included three homeobox genes that are involved in formation of the forebrain. In particular Otx2 and Gbx2 interact to regulate rostral brain development and to close sensitive periods (Table 5).

Table 5.

Functional annotation clusters from DAVID for Downregulated genes

| Gene Group 1. Neuromodulators/social behavior | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Name | Putative function* | Fold |

| Oxt | oxytocin, prepropeptide | Codes fror oxytocin and neurophysin I, involved in cognition, tolerance, adaptation and complex sexual and maternal behavior, as well as in the regulation of water excretion and cardiovascular functions | −1.60 |

| Pmch | pro-melanin- concentrating hormone | Acts as a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator in a broad array of neuronal functions | −1.49 |

| Avp | arginine vasopressin | Acts on a variety of homeostatic functions, especially mammalian social behaviors | −1.31 |

| ACE | angiotensin I converting enzyme | Decreased ACE function results in anxiety-like but not depressant like behavior (Okuyama et al., 1999) | −1.34 |

| ALDH1A1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member A1 | ALDH1A1 is expressed in VTA dopaminergic neurons. Altered in infant attachment (Barr et al., 2009) | −1.26 |

| Gene Group 2. Homeobox genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Gene Name | Putative Function* | Fold |

| Otx2 | orthodenticle homeobox 2 | Key regulator of neural plasticity, rostral brain development and closing of critical periods (Sugiyama et al., 2009; Beurdeley et al., 2012). | −1.76 |

| Irx5 | iroquois homeobox 5 | Required for proper formation of posterior forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain and, to a lesser an extent, spinal cord | −1.40 |

| Gbx2 | gastrulation brain homeobox 2 | Interacts with Otx2 to regulate rostral brain development and brain segmentation (Inoue et al., 2012) | −1.34 |

From NIH and RGD databases and the cited literature.

Note. In addition to the two groups above, a third group of down regulated probes consisted of Cthrc1 (collagen triple helix repeat containing 1), Rnase12 (ribonuclease, RNase A family, 12 (non-active) and Scgb1c1 (secretoglobin, family 1C, member 1). However their relation to brain function is unknown.

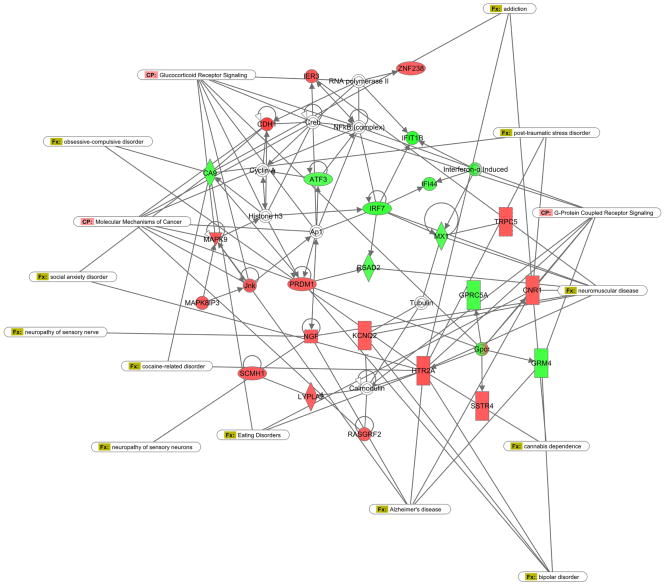

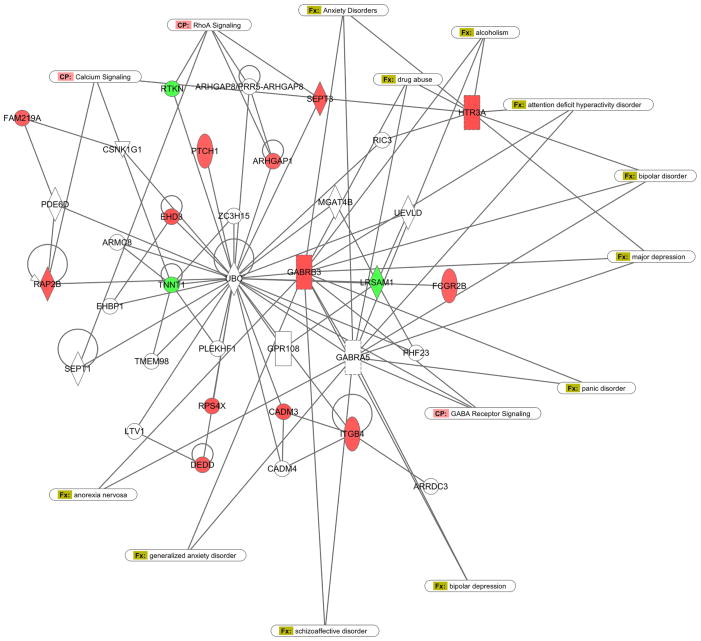

3.2.5 Pathway analysis

IPA pathway analysis showed three networks that were significantly enriched in the probe set. We present two of these networks that show relationships of gene expression to the behavioral phenotype. Network 2 was defined as a “Neurological disease, organ injury, inflammatory disease” network (Figure 3). In this network, there are a number of expression changes that focus on G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). These include receptors involved in cannabinoid, somatostatin, glutamate and serotonin processing. In addition, there are networks related to MAPKinase processing and sodium and potassium channels, as found from the DAVID analysis. Network 3 (Figure 4) focuses around GABA, calcium and RhoA signaling, processes that are putatively involved in neuropsychiatric disorders (Lowe et al., 2007).

Figure 3.

Ingenuity Pathway Analyses: Pathway analyses were from the commercially available Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. Input was the top 100 up- and top 100-downregulated probes ordered by fold change. Three networks were significantly enriched. Up-regulated probes are in red whereas down-regulated probes are in green. The network 2 shown here was defined as “Neurological disease, organ injury, inflammatory disease”. Canonical pathways identified by the pattern of gene expression are shown in the long ovals labeled “CP” in pink. These included a large number of G-protein coupled receptors. Associated disease states are also in long ovals labeled “Fx” in green. A number of disorders related to anxiety, addiction and stress were significantly over-represented (social anxiety; “ptsd”).

Figure 4.

Ingenuity Pathway Analyses: Details are as in Figure 3. This is network 3 from the IPA analysis. There were three major canonical signaling pathways associated with the phenotype including GABA, RhoA and Calcium. Similar to Figure 3, the associated disease states are directly related to anxiety disorders (e.g. generalized anxiety; anxiety disorders; panic disorder) or have an anxiety related components.

4.0 Discussion

Here we tested the hypothesis that unpredictable trauma during early development produces changes to the genetic phenotype of the amygdala nuclei and that this is associated with later life anxiety-like behaviors. The idea that unpredictable trauma can lead to enhanced anxiety draws from a multitude of clinical studies demonstrating heightened emotionality and anxiety (Famularo et al., 1992; Newman et al., 1996; Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Anderson, 2003; Costello et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2007; Gartstein et al., 2010). We modeled early life unpredictable stress in developing rats and found enhanced levels of anxiety when tested in adulthood compared to control, non-stressed adults. We then asked whether these behavioral changes were associated with specific alterations to the genetic phenotype within the amygdala. The overall results of the gene expression analysis demonstrate long-lasting changes due to the early unpredictable electrical shock. These changes were both broad in scope and specific to particular receptors and disease states. In general, multiple neurotransmitters that are implicated in anxiety, including GABA, cannabinoid, somatostatin, glutamate and serotonin were affected. However, we also show multiple changes in ion channels that imply long-term alterations in membrane potentials and firing ability. How these global effects alter the propensity for anxiety by changing specific signaling pathways remains an open question.

4.1 Unpredictable versus predictable trauma in animal models

The ability to test the impact of infant trauma using shock in a highly controlled environment allows us to examine specifically the effect of unpredictable infant pain. It is recognized that shock alters later emotionality, with unpredictable shock producing significant enhancement in adult emotionality compared to predictable infant shock and is consistent with adult literature on the impact of trauma (Levine et al., 1956; Fride and Weinstock, 1984). Our findings further indicate that shock during early life that occurs in an unpredictable manner results in enhanced measures of anxiety when tested in adulthood (Figure 1). This was determined by placing adult animals in a light/dark box, a highly sensitive test of anxiety-like behaviors often used in rodents. Animals that had experienced unpredictable developmental trauma demonstrated a longer latency for leaving the dark area and entering the light area (Figure 1A). These animals also displayed more defecations and urinations during testing (Figure 1B and 1C) than control animals, measures that are often used to indicate high levels of anxiety (O’Malley et al., 2010; Daly et al., 2012; Kolyaduke and Hughes, 2013). These results replicate and extend earlier findings that long term anxiety-like behaviors are a result of unpredictable early-life shock. Importantly, predictable shock does not have this effect on these measures (Tyler et al., 2007), but instead produces depressive-like behaviors in adulthood (Sevelinges et al., 2011; Raineki et al., 2012).

Our behavioral results supplement a body of literature using chronic unpredictable or variable stress as one of the most clinically relevant stress paradigms in the rodent, in that it produces many of the behavioral profiles observed in patients with anxiety and related mood disorders (Pittenger and Duman, 2008). Other models of early life unpredictable stress also report long-term deficits in cognitive abilities (Baram et al., 2012) For example, fragmented rough interaction with the mother during early life leads to deficits when tested on learning and memory tasks (Rice et al., 2008). In addition, these results are consistent with similar studies in adolescents or adults (D’Aquila et al., 1994; Zurita et al., 2000; Maslova et al., 2002; Bondi et al., 2008), for example, Pohl et al., (Pohl et al., 2007) found that intermittent exposure to physical stressors (foot- shock and cold water immersion) throughout adolescence led to enhanced anxiety-related behaviors in adult rats on the elevated plus-maze and shock-probe burying tests. In adult rats, chronic unpredictable stress leads to increasing levels of anxiety over the course of several weeks following the stress manipulation (Matuszewich and Yamamoto, 2003). Finally, in a non-rodent animal model, the zebra fish, unpredictable stress can lead to enhanced levels of anxiety (Piato et al., 2011; Chakravarty et al., 2013).

In contrast to the numerous effects of unpredictable trauma on later life behaviors, predictable trauma, such as pairing a sensory stimulus with a shock during early life, is strongly associated with depressive-like behaviors (Teicher et al., 2003; Stovall-McClough and Cloitre, 2006; Heim et al., 2009). For example, animal models of predictable early-life trauma have demonstrated a clear impact on later life depressive-like behaviors (Sevelinges et al., 2011). This is in sharp contrast with the effect in adolescents and adults as findings suggest that, in fact, unpredictable adverse events may lead to depressive-like behaviors and “learned helplessness” (Seligman and Maier, 1967; Sherman et al., 1979).

4.2 Comparison to clinical findings

Clinically, a myriad of studies have demonstrated that periods of variable or unpredictable stress during the lifespan can result in a higher incidence of mental illness, including heightened anxiety (Heim and Nemeroff, 2001; Heim et al., 2009), for example in adults with chronic variable stress, such as found in those in high-risk occupations or low-income status (Regier et al., 1993; Kessler et al., 1994). Surveys assessing the effects of unpredictable childhood trauma or abuse also show a strong relationship to a number of behavioral problems, including heightened anxiety, depression and other physical disorders such as irritable bowl syndrome (Lowman et al., 1987; Drossman et al., 1990; Talley et al., 1994; Talley et al., 1995; Fremont, 2004). One factor that seems to highly influence the behavioral outcome is the age at which the trauma occurs. Intermittent adversity that occurs across both childhood and adolescence seems to have a large effect on later life behavior. However, when assessed closer, adversity that occurs only during early childhood or pre-puberty seems to have a greater impact as opposed to adversity in later adolescence. In fact, chronic stress during late adolescence may lead to resilience (Beitchman et al., 1992; Maercker et al., 2004; Wilkin et al., 2012). Similar to this, our animal model more closely simulates adversity during early childhood and we show a dramatic behavioral effect in adulthood.

4.3 Modifications to genetic phenotype within the amygdala

A primary objective of this study was to examine whether modifications in the genetic phenotype within the amygdala occur as a result of early life unpredictable trauma. Prior reports have shown that the amygdala undergoes dramatic modifications as a function of early life trauma (Sevelinges et al., 2007; Sevelinges et al., 2008; Moriceau et al., 2009; Raineki et al., 2009; Landers and Sullivan, 2012). For example, predictable trauma leads to depressive-like behaviors and importantly, altered amygdala function (Sevelinges et al., 2011; Raineki et al., 2012). Here, we examined the amygdala at the genetic level using a broad unbiased screen for networks of genes that were altered by early unpredictable stress. There were three major findings. There were far more downregulated than upregulated probesets. For the Gene Ontology Biologic Function, there were global categories that did not differ for up and downregulated genes. These functions were metabolic and cellular, developmental and transport related, and reflect the large global changes induced by early unpredictable shock. However, the cellular localization of these functions did differ for each direction. Upregulated genes were largely located on the cell membrane and included adhesion molecules, receptors, transport channels, among others. One group of seemingly unrelated genes were found, each of which is implicated in anxiety or fear. Downregulated genes were more evenly dispersed, and about 50% located extracellularly and 50% intracellularly or on the plasma membrane. The gene ontology analysis showed a different set of genes that were downregulated compared to upregulated. These included genes coding for neuromodulatory transmitters that are involved in 1) social behavior and 2) brain organization and neuroplasticity. Otx2 is involved in the regulation of GABA, serotonin and dopamine neurons of the midbrain (Borgkvist et al., 2006). Of particular note here is that Otx2 binding to perineuronal nets and parvalbumin positive GABA neurons is necessary and sufficient to open and close (Beurdeley et al., 2012) the critical period of neuroplasticity in visual cortex. Although there are no data on the functional role of Otx2 specifically in the amygdala, perineuronal nets have been proposed to be a molecular mechanism that mediates the critical period when ability to “forget” conditioned fear is lost (Gogolla et al., 2009).

Finally the network analysis of altered genes showed two networks related to anxiety. The first consisted of GPRC’s including upregulated serotonin receptors and a variety of transcription factors; the second included GABA receptors and signaling pathways.

To our knowledge, there are relatively few assessments of specific changes to the genetic profile following early life trauma within the amygdala. One such study examined mRNA from the amygdala following periods of maternal separation in non-human primates and found changes to specific genes associated with social behavior (Sabatini et al., 2007). In another example, unpredictable stress in adulthood was found to alter serotonin receptor mediated and glutamatergic responses for several months following termination of the last stressor (Alfarez et al., 2003; Matuszewich and Yamamoto, 2003; Joels et al., 2004). Finally, across several brain areas and across generations, unpredictable stress can alter the cellular distribution and levels of serotonin receptor subtypes (Franklin et al., 2011; Hazra et al., 2012) as well as levels of serotonin (Huang et al., 2012). In fact, the use of antidepressant drugs, such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors can reduce the display of anxiety following paradigms of chronic unpredictable stress (Bondi et al., 2008). We also report changes in GABAergic neurotransmission following early life trauma (Table 1; Figure 4). In agreement, periods of unpredictable stress in adults, leads to modifications to GABAergic receptor genes (Qin et al., 2004) and suppression of inhibitory input to hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis neurons (Joels et al., 2004; Verkuyl et al., 2004). While in line with the above studies, our results extend this by showing that dramatic modifications occur within the amygdala, a region critical for emotionality and stress induced responses. Our results suggest that early life unpredictable trauma can lead to long-term changes to the genetic profile of the amygdala that could largely contribute to the emergence of anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood.

Highlights.

Unpredictable early-life trauma leads to higher levels of anxiety-like behavior.

Genes related to synaptic transmission, such as 5HT and GABA, were up regulated.

Genes related to social behavior, emotion, and brain formation were down regulated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MH80603 to GB and RS. We thank Kyle Muzney for the technical assistance in behavioral data collection.

Footnotes

Drs. Sarro, Sullivan and Barr report no financial interests of potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alfarez D, Joels M, Krugers H. Chronic unpredictable stress impairs long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal CA1 area and dentate gyrus in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1928–1934. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baram T, Davis E, Obenaus A, Sandman C, Small S, Solodkin A, Stern H. Fragmentation and unpredictability of early-life experience in mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:907–915. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman J, Zucker K, Hood J, daCosta G, Akman D, Cassavia E. A review of the long-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1992;16:101–118. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurdeley M, Spatazza J, Lee HH, Sugiyama S, Bernard C, Di Nardo AA, Hensch TK, Prochiantz A. Otx2 binding to perineuronal nets persistently regulates plasticity in the mature visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9429–9437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0394-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi C, Rodriguez G, Gould G, Frazer A, Morilak D. Chronic unpredictable stress induces a cognitive deficit and anxiety-like behavior in rats that is prevented by chronic antidepressant drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:320–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgkvist A, Puelles E, Carta M, Acampora D, Ang SL, Wurst W, Goiny M, Fisone G, Simeone A, Usiello A. Altered dopaminergic innervation and amphetamine response in adult Otx2 conditional mutant mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R, Armengaud P, Amtmann A, Herzyk P. Rank products: a simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty S, Reddy B, Sudhakar S, Saxena S, Das T, Meghah V, Brahmendra Sqamy C, Kumar A, Idris M. Chronic Unpredictable Stress (CUS)-Induced Anxiety and Related Mood Disorders in a Zebrafish Model: Altered Brain Proteome Profile Implicates Mitochondrial Dysfunction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney D, Drevets W. Neurobiological basis of anxiety disorders. In: Davis K, Charney D, Coyle J, Nemeroff C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; 2002. pp. 901–930. [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, PhD, Mustillo S, PhD, Erkanli A, PhD, Keeler G, MS, Angold A., MRCPsych Prevalence and Development of Psychiatric Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley J. Exploratory behavior models of anxiety in mice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1985;9:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(85)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aquila P, Brain P, Willner P. Effects of chronic mild stress on performance in behavioural tests relevant to anxiety and depression. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:861–867. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly F, Hughes R, Woodward L. Subsequent anxiety-related behavior in rats exposed to low-dose methadone during gestation, lactation or both periods consecutively. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2012;102:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman D, Leserman J, Nachman G, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:828–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-11-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Psychiatric diagnoses of maltreated children: preliminary findings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;31:863–867. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyder M, Karlsson RM, Mathur P, Lyman M, Bock R, Momenan R, Munasinghe J, Scattoni ML, Ihne J, Camp M, Graybeal C, Strathdee D, Begg A, Alvarez VA, Kirsch P, Rietschel M, Cichon S, Walter H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Grant SG, Holmes A. Association of Mouse Dlg4 (PSD-95) Gene Deletion and Human DLG4 Gene Variation With Phenotypes Relevant to Autism Spectrum Disorders and Williams’ Syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1508–1517. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin T, Linder N, Russig H, Thony B, Mansuy I. Influence of early stress on social abilities and serotonergic functions across generations in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremont W. Childhood reactions to terrorism-induced trauma: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:381–392. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Weinstock M. The effects of prenatal exposure to predictable or unpredictable stress on early development in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1984;17:651–660. doi: 10.1002/dev.420170607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein M, Bridgett D, Rothbart M, Robertson C, Iddins E, Ramsay K, Schlect S. A latent growth examination of fear development in infancy: contributions of maternal depression and the risk for toddler anxiety. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:651–668. doi: 10.1037/a0018898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolla N, Caroni P, Luthi A, Herry C. Perineuronal nets protect fear memories from erasure. Science. 2009;325:1258–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.1174146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL. Deconstructing sociality, social evolution and relevant nonapeptide functions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:465–478. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson JL, Kingsbury MA. What’s in a name? Considerations of homologies and nomenclature for vertebrate social behavior networks. Horm Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazra R, Guo J, Dabrowska J, Rainnie D. Differential distribution of serotonin receptor subtypes in BNST(ALG) neurons: modulation by unpredictable shock stress. Neurosci. 2012;225:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Bradley B, Mletzko T, Deveau T, Musselman D, Nemeroff C, Ressler K, Binder E. Effect of childhood trauma on adult depression and neuroendocrine function: Sex-specific moderation by CRH receptor 1 gene. Frontiers Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:41. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.041.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff C. The Role of Childhood Trauma in the Neurobiology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Xu H, Li H, Yang H, Chen Y, Shi X. Pre-gestational stress reduces the ratio of 5-HIAA to 5-HT and the expression of 5-HT1A receptor and serotonin transporter in the brain of foetal rat. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot R, Thrivikraman K, Meaney M, Plotsky P. Development of adult ethanol preference and anxiety as a consequence of neonatal maternal separation in Long Evans rats and reversal with antidepressant treatment. Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:366–373. doi: 10.1007/s002130100701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue F, Kurokawa D, Takahashi M, Aizawa S. Gbx2 directly restricts Otx2 expression to forebrain and midbrain, competing with class III POU factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:2618–2627. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00083-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa Y, Tamura H, Shiosaka S. Diversity of neuropsin (KLK8)-dependent synaptic associativity in the hippocampal pyramidal neuron. J Physiol. 2011;589:3559–3573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Karst H, Alfarez D, Heine V, Qin Y, van Riel E, Verkuyl M, Lucassen P, Krugers H. Effects of chronic stress on structure and cell function in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus. Stress. 2004;7:221–231. doi: 10.1080/10253890500070005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinichev M, Easterling K, Holtzman S. Long-lasting changes in stress-induced corticosterone response and anxiety-like behaviors as a consequence of neonatal maternal separation in Long–Evans rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Amminger G, Aquilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun T. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Chiu W, Demier O, Merikangas K, Walters E. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, McGonagle K, Zhao S, Nelson C, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H, Kendler K. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolyaduke O, Hughes R. Increased anxiety-related behavior in male and female adult rats following early and late adolescent exposure to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103:742–749. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koston T, Lee H, Kim J. Early life stress impairs fear conditioning in adult male and female rats. Brain Res. 2006;1087:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers M, Sullivan R. The Development and Neurobiology of Infant Attachment and Fear. Dev Neurosci. 2012;34:101–114. doi: 10.1159/000336732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S, Chevalier J, Korchin S. The effects of early shock and handling on later avoidance learning. J Pers. 1956;24:475. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1956.tb01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe XR, Lu X, Marchetti F, Wyrobek AJ. The expression of Troponin T1 gene is induced by ketamine in adult mouse brain. Brain Res. 2007;1174:7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman B, Drossman D, Cramer E, McKee D. Recollection of childhood events in adults with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:324–330. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198706000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A, Michael T, Fehm L, Becker E, Margraf J. Age of traumatisation as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder or major depression in young women. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:482–487. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslova L, Bulygina V, Markel A. Chronic stress during prepubertal development: immediate and long-lasting effects on arterial blood pressure and anxiety-related behavior. Psychoneuroendocrin. 2002;27:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszewich L, Yamamoto B. Long-lasting effects of chronic stress on DOI-induced hyperthermia in male rats. Psychopharmacol. 2003;169:169–175. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney M. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D377–386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriceau S, Raineki C, Holman J, Holman J, Sullivan R. Enduring neurobehavioral effects of early life trauma mediated through learning and corticosterone suppression. Frontiers Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:1–13. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.022.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya T, Kouzu Y, Shibata S, Kadotani H, Fukunaga K, Miyamoto E, Yoshioka T. Close linkage between calcium/calmodulin kinase II alpha/beta and NMDA-2A receptors in the lateral amygdala and significance for retrieval of auditory fear conditioning. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3307–3314. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Landgraf R. Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Magdol L, Silva P, Stanton W. Psychiatric disorder in a birth cohort of young adults: prevalence, comorbidity, clinical significance, and new case incidence from ages 11 to 21. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:552–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrholm S, Kessler R. Genetics of anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Neurosci. 2009;164:272–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley D, Julio-Pieper M, Gibney S, Dinan T, Cryan J. Distinct alterations in colonic morphology and physiology in two rat models of enhanced stress-induced anxiety and depression-like behaviour. Stress. 2010;13:114–122. doi: 10.3109/10253890903067418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyama S, Sakagawa T, Chaki S, Imagawa Y, Ichiki T, Inagami T. Anxiety-like behavior in mice lacking the angiotensin II type-2 receptor. Brain Res. 1999;821:150–159. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piato A, Capiotti K, Tamborski A, Oses J, Barcellos L, Bogo M, Lara D, Vianna M, Bonan C. Unpredictable chronic stress model in zebrafish (Danio rerio): behavioral and physiological responses. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pick JE, Malumbres M, Klann E. The E3 ligase APC/C-Cdh1 is required for associative fear memory and long-term potentiation in the amygdala of adult mice. Learn Mem. 2013;20:11–20. doi: 10.1101/lm.027383.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger C, Duman R. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl J, Olmstead M, Wynne-Edwards K, Harkness K, Menard J. Repeated exposure to stress across the childhood-adolescent period alters rats’ anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in adulthood: The importance of stressor type and gender. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:462–474. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.3.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C, Feldon J. Long-term neurobehavioral impact of the postnatal environment in rats: manipulations, effects and mediating mechanisms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Karst H, Joels M. Chronic unpredictable stress alters gene expression in rat single dentate granule cells. J Neurochem. 2004;89:364–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2003.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C, Moriceau S, Sullivan R. Developing a Neurobehavioral Animal Model of Infant Attachment to an Abusive Caregiver. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;67:1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C, Rincon-Cortes M, Belnoue L, Sullivan R. Effects of Early-Life Abuse Differ across Development: Infant Social Behavior Deficits Are Followed by Adolescent Depressive-Like Behaviors Mediated by the Amygdala. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7758–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5843-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier D, Farmer M, Rae D, Myers J, Kramer M, Robins L, George L, Karno M, Locke B. One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatrica Scand. 1993;88:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C, Sandman C, Lenjavi M, Baram T. A novel mouse model for acute and long-lasting consequences of early life stress. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4892–4900. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter S, Gorny X, Machts J, Behnisch G, Wustenberg T, Herbort MC, Munte TF, Seidenbecher CI, Schott BH. Effects of AKAP5 Pro100Leu Genotype on Working Memory for Emotional Stimuli. PLoS One. 2013:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues S, Ledoux J, Sapolsky R. The influence of stress hormones on fear circuitry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:289–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Sweatt J. Annual Research Review: Epigenetic mechanisms and environmental shaping of the brain during sensitive periods of developmenr. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:398–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini M, Ebert P, Lewis D, Levitt P, Cameron J, Mirnics K. Amygdala gene expression correlates of social behavior in monkeys experiencing maternal separation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3295–3304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4765-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M, Maier S. Failure to escape traumatic shock. J Exp Psychol. 1967;74:1–9. doi: 10.1037/h0024514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y, Moriceau S, Holman O, Miner C, Muzny K, Gervaise R, Mouly A, Sullivan R. Enduring Effects of Infant Memories: Infant Odor-Shock Conditioning Attenuates Amygdala Activity and Adult Fear Conditioning. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1070–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y, Mouly A, Raineki C, Moriceau S, Forest C, Sullivan R. Adult depression-like behavior, amygdala and olfactory cortex functions are restored by odor previously paired with shock during infant’s sensitive period attachment learning. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevelinges Y, Sullivan R, Messaoudi B, Mouly A. Neonatal odor-shock conditioning alters the neural network involved in odor fear learning at adulthood. Learn Mem. 2008;15:649–656. doi: 10.1101/lm.998508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A, Allers G, Petty F, Henn F. A neuropharmacologically relevant animal model of depression. Neuropharmacology. 1979;18:891–893. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(79)90087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stovall-McClough K, Cloitre M. Unresolved attachment, PTSD, and dissociation in women with childhood abuse histories. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:219–228. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama S, Prochiantz A, Hensch TK. From brain formation to plasticity: insights on Otx2 homeoprotein. Dev Growth Differ. 2009;51:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley J, Fett S, Zinsmeister A. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: Association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:366–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley J, Fett S, Zinsmeister A, Melton L. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: A population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher M, Andersen S, Polcari A, Andersen C, Navalta C, Kim D. The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler K, Moriceau S, Sullivan R, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Long-term colonic hypersensitivity in adult rats induced by neonatal unpredictable vs predictable shock. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:761–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkuyl M, Hemby S, Joels M. Chronic stress attenuates GABAergic inhibition and alters gene expression of parvocellular neurons in rat hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1665–1673. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss I, Franklin T, Vizi S, Mansuy I. Inheritable effect of unpredictable maternal separation on behavioral responses in mice. Frontiers Behav Neurosci. 2011:5. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2011.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigger A, Neumann I. Periodic maternal deprivation induces gender-dependent alterations in behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to emotional stress in adult rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;66:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin M, Waters P, McCormick C, Menard J. Intermittent physical stress during early- and mid-adolescence differentially alters rats’ anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in adulthood. Behav Neurosci. 2012;126:344–360. doi: 10.1037/a0027258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita A, Martijena I, Cuadra G, Brandao M, Molina V. Early exposure to chronic variable stress facilitates the occurrence of anhedonia and enhanced emotional reactions to novel stressors: reversal by naltrexone pretreatment. Behav Brain Res. 2000;117:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]