Abstract

The Notch pathway is a cell signaling pathway determining initial specification and subsequent cell fate in the inner ear. Previous studies have suggested that new hair cells (HCs) can be regenerated in the inner ear by manipulating the Notch pathway. In the present study, delivery of siRNA to Hes1 and Hes5 using a transfection reagent or siRNA to Hes1 encapsulated within poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles increased HC numbers in non-toxin treated organotypic cultures of cochleae and maculae of postnatal day 3 mouse pups. An increase in HCs was also observed in cultured cochleae and maculae of mouse pups pre-conditioned with a HC toxin (4-hydroxy-2-nonenal or neomycin) and then treated with the various siRNA formulations. Treating cochleae with siRNA to Hes1 associated with a transfection reagent or siRNA to Hes1 delivered by PLGA nanoparticles decreased Hes1 mRNA and up-regulated Atoh1 mRNA expression allowing supporting cells (SCs) to acquire a HC fate. Experiments using cochleae and maculae of p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mouse pups demonstrated that newly generated HCs trans-differentiated from SCs. Furthermore, PLGA nanoparticles are non-toxic to inner ear tissue, readily taken up by cells within the tissue of interest, and present a synthetic delivery system that is a safe alternative to viral vectors. These results indicate that when delivered using a suitable vehicle, Hes siRNAs are potential therapeutic molecules that may have the capacity to regenerate new HCs in the inner ear and possibly restore human hearing and balance function.

Keywords: hair cell regeneration, inner ear, Notch pathway, siRNA, nanoparticle, mouse

INTRODUCTION

Hair cells (HCs) and supporting cells (SCs) in the sensory epithelium of the inner ear arise from a common progenitor (Fekete et al., 1998; Lanford et al., 1999; Kiernen et al., 2005; Raft et al., 2007; Riley et al., 1999). Recent evidence suggests that Notch pathway proteins play a role in keeping SCs in their phenotypic state in mammals and prevent them from becoming HCs via a process of lateral inhibition (Landford et al., 1999; Zheng et al., 2000; Zine et al., 2001).

The Notch pathway determines initial specification and subsequent cell fate of sensory progenitors (Kelley, 2006; Murata et al., 2006). Embryonic Notch signaling directs the formation of the intricate SC and HC mosaic of inner ear epithelia. This mosaic pattern is accomplished through lateral inhibition, involving the cell surface receptor Notch and its interactions with ligands, such as Jagged and Delta. Ligand-Notch binding induces the γ-secretase-mediated cleavage of the intracellular domain of Notch, which, in turn, translocates to the nucleus to form a transcription complex that activates the expression of Hes1 and Hes5 (Hairy and enhancer of split 1 and 5), inducing a SC fate (Lanford et al., 1999; Murata et al., 2006). Hes1 and Hes5 encode two inhibitory basic helix-loop-helix proteins, which down regulate the expression of Atoh1 and other prosensory genes in differentiating SCs (Kelley, 2006). Expression of Atoh1 is critical for the formation of HCs in the normal sensory epithelium (Bermingham et al., 1999). However, in mammals, Atoh1expression is attenuated at early postnatal stages and remains low throughout adulthood, while expression of Hes1 becomes elevated at late embryonic and early postnatal stages and is maintained at a relatively high level throughout adulthood, which may be one of the mechanisms that maintains the appropriate complement of HCs and SCs in the inner ear (Zheng et al., 2000). In support of this model, reduction of Hes transcripts in presumptive HCs promotes expression of Atoh1 and leads to terminal differentiation into the HC phenotype (Zheng and Gao, 2000; Zine et al., 2001; Zine and de Ribaupierre, 2002).

It appears that the Notch pathway is altered shortly after vestibular epithelial injury, allowing HC regeneration in mammals (Batts et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010). Moreover, regeneration can be enhanced in mammalian cochlear and vestibular epithelia by ectopic Atoh1 expression, using an adenoviral vector (Izumikawa et al., 2005; Shou et al., 2003; Staecker et al., 2007). Decreasing Notch signaling with γ-secretase inhibitors results in ectopic HC replacement in the mammalian cochlea (Hori et al., 2007). Decreasing Notch pathway activity in mouse utricular epithelia in vitro by inhibiting γ-secretase or another enzyme required for Notch activity resulted in a non-mitotic increase in HCs limited to the striolar/juxtastriolar region (Collado et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011). Utricular tissue in mice exposed to an ototoxin, exhibited a reduction in Hes5 transcript levels that was correlated with an increase in Atoh1 mRNA and the appearance of embryonic-like HCs (Wang et al., 2010). Importantly, a recent report noted that toxin-induced damage to adult guinea pig cochleae resulted in increased Hes1 and Notch1 protein expression and increased levels of the Notch intracellular domain, suggesting active inhibition of a regenerative response under these conditions (Batts et al., 2009). Another recent study reported that siRNA to Hes5 enhanced HC regeneration in mouse utricles (Jung et al., 2013). Therefore, it may be possible to overcome the inhibition imposed on the regenerative process by knocking down mRNA levels for Hes1 and Hes5 and potentially driving SCs toward the formation of new HCs in the injured cochlear and vestibular sensory epithelia.

In the present study, we show that knock down of Hes1 and Hes5 mRNA levels, using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), leads to an increase in Atoh1 transcript levels, presumably inducing HC differentiation. We used siRNA targeting Hes1 and Hes5 complexed with a transfection reagent or Hes1 siRNA delivered using biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (NPs) without transfection reagent to inhibit Hes genes in the organ of Corti (OC) and in maculae (utricles and saccules) from neonatal mouse pups pre-treated with toxins to eliminate HCs. An increased number of HCs was observed in toxin-treated cochleae and maculae that had been subsequently treated with siRNA against Hes1 or Hes5. This work presents two main findings: (1) siRNA targeting of Hes genes increased the appearance of HCs in mouse pup OCs and vestibular maculae, and (2) some of the new HCs appeared to have arisen as a result of transdifferentiation of SCs. The results presented herein provide a foundation for a potential therapeutic strategy to regenerate HCs in vivo in mammals. Inner ear delivery of siRNA using PLGA NPs may be a potential approach to treat inner ear diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CD-1 Mouse pup cochleae collection and culturing conditions

The experimental procedures described herein were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Three-day-old (P3) CD-1 mouse pups (Charles River Laboratories International, Inc., Wilmington, MA) were euthanized, and inner ear capsules were dissected out. The cochlear capsule was carefully opened, and the membranous OC with the stria vascularis was removed. After stripping off the stria vascularis, the basilar membrane with the OC was placed on a collagen gel drop in a 35 mm culture dish. The cochleae were cultured in DMEM with N2 supplements (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% air.

After an initial incubation of 24 hours, the cochleae were treated with or without 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) for an additional 24 hours. The cultured OCs were then incubated in the absence of 4-HNE in fresh media containing siRNA delivered via lipofection (LF) with JetSI™ 10 mM transfection reagent (BIOPARC, Illkirch, France, siRNALF) or Hes1 siRNA NPs (Hes1 siRNANP, detailed below). Control cultures consisted of cochleae that were left untreated or were treated with lipofected scrambled siRNA (scRNALF) or scRNA-containing NPs (scRNANP). 4-HNE was prepared as a 60 mM stock solution in DMSO and used at a final concentration of 100-475 μM (Guzman et al., 2006; Ruiz et al., 2006).

CD-1 Mouse pup maculae collection and culturing conditions

After removing the cochleae, the vestibular capsule was opened and maculae (utricles and saccules) were harvested with the otoconial membrane in place. After opening the membranous sac and stripping off the otoconial membrane, the maculae were cultured on a collagen gel drop in a 35 mm culture dish in drug-free medium for 24 hours and then incubated in fresh medium alone (untreated cultures), or in medium containing 4 mM neomycin (Neo, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or in medium with neomycin plus either scRNALF, Hes1 siRNALF, Hes1 siRNANP or scRNANP. We only used Hes1 siRNA in macular studies due to the fact that we did not see any synergistic effects in OCs when Hes1 and Hes5 siRNA (Hes1/5 siRNALF) were used in combination (detailed in the Results section below).

siRNA delivery via lipofection

Twenty four hours after incubation with or without 4-HNE, siRNA was added into the dishes. scRNA (at a final concentration of 20 nM, Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX), Hes1 siRNA (20 nM), or a combination of Hes1 and Hes5 siRNA (mouse, each at 20 nM, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) were transfected via LF using JetSI™ 10 mM transfection reagent (25 nM, BIOPARC, Illkirch, France), and transfectants were cultured for an additional 48 hours prior to transitioning to drug-free medium with exchanges of fresh medium every other day (exposed to siRNA for a total of 48 hours). The cultures were maintained in vitro for a total of eight days. The Hes1 siRNA and Hes5 siRNA pools each represented a total of three target-specific, 20-25 nucleotide double-stranded RNA molecules designed to knock down either Hes1 or Hes5 expression, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA).

siRNA delivery via NPs

All NP formulations were fabricated and characterized using a double emulsion technique that was modified for high-density oligonucleotide loading (Cheng and Saltzman, 2011; Cu et al., 2010; Cu and Saltzman, 2009; Woodrow et al., 2009). The amount of siRNA loaded into the PLGA NPs was 100-500 pmol per mg of NPs.

Twenty four hours after incubation with or without 4-HNE, Hes1 siRNANP (1-800 μg/ml) or scRNANP (negative control, 1-800 μg/ml) were added along with fresh medium into the culture dishes. Media with NPs was exchanged every other day. The cultures were exposed to the NPs for a total of six days (3 doses of NPs, a total of eight days in vitro).

NP or siRNA uptake in OC cultured tissues

Our experiment was guided by previous studies suggesting that PLGA NPs are taken up over a predictable time interval in cultured cells (Cartiera et al., 2009; Davda and Labhasetwar, 2002). To estimate numbers of OC cells and of Jagged1 (Jag1) positive SCs that had taken up NPs or lipofected siRNA, cultured OCs were incubated with either 200 μg/ml of NPs loaded with the lipophilic fluorescent dye, coumarin 6, for 12-48 hours or with FAM (a fluorescent dye)-labeled scRNA (Silencer® FAM Labeled Negative Control No. 1 siRNA, 20 nM, Ambion) coupled with the JetSI™ transfection regent for 48 hours. NPs containing coumarin 6 were synthesized using a modification of a single emulsion technique (Cu et al., 2010; Cu and Saltzman, 2009).

Six OCs were used for each experimental condition and for each time point (12, 24 or 48 hours after NP incubation). Following incubation with the fluorescently-labeled reporter constructs, the OCs were harvested, and the constituent cells were enzymatically-dissociated according to a technique described previously by White and colleagues (White et al., 2006). The dissociated cells were stained with goat anti-Jagged1 antibody (a SC marker, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) and then Alexa Fluor® 594 donkey anti-goat IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. After staining, the cells were spread across the surface of a slide and air-dried. Coverslips were applied with antifade medium, and slides were randomly photographed (Leica SP2 confocal microscope, Heidenberg, Germany). Numbers of Jag1 positive or negative cells that had taken up coumarin NPs or FAM labeled scRNA were quantified. One thousand to two thousand cells were counted for each condition. Percentages of cells with coumarin NPs or FAM scRNA were calculated and statistically analyzed (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

NPs (A) or siRNA (B, C) were readily taken up by cultured OC cells from mouse pups. The OC cells were stained with anti-Jag1 IgG (red) and DAPI (blue) and examined by confocal microscopy (A-C). Examples of clusters of Coumarin NPs (green) were found in Jag1 positive (arrows in A) and negative (arrowheads in A) OC cells 48 hours after NP exposure. FAM-labeled scRNA (FAM scRNA, green) was also found in Jag1 positive (arrows in B and C) and negative cells (arrowheads in B and C) arising from dissociated OC explants (B) and in cross sectional views of intact OCs (C). The number of Jagged1 positive or negative cells that had taken up coumarin NPs or FAM scRNA was counted and statistically analyzed (D). Equal numbers of Jag1 positive (13.01-14.29%) and Jag1 negative (13.01-13.43%) cells had NPs at 12 or 24 hours after NP exposure (p > 0.05). More Jag1 positive cells (23.08%) contained NPs 48 hours compared to 24 hours after NP exposure (p < 0.05). More Jag1 positive cells (55.35%) contained scRNA than Jag1 negative cells (38.77%) 48 hours after scRNA exposure (p < 0.05). Scale bar = 10 μm in B (applies to images shown in A, B) and C.

To identify the location of transfected cells in cultured OCs, tissues were harvested 48 hours after exposure to FAM-labeled scRNA, fixed in 4% formaldehyde diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and serial vertical cryosections (10 μm of thickness) were obtained from the middle turns. Cryosectons were then stained with goat anti-Jagged1 antibody as described below. Images were acquired on a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Heidenberg, Germany).

Hes and Atoh1 mRNA expression in OCs after siRNA treatment

Inhibition of Notch signaling has been shown to up-regulate Atoh1 expression in cultured neonatal mouse utricles (Collado et al., 2011). To study the effects and efficiency of siRNA inhibition on the Notch-responsive effectors Hes1 and Hes5, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was conducted to assess changes in the levels of Hes1, Hes5, and Atoh1 among mRNA pools isolated from cultured OCs that had been treated with either 20nM scRNALF, Hes1 siRNALF, or Hes5 siRNALF or 200-600 μg/ml of empty NPs or Hes1 siRNANPs or 475 μM 4-HNE according to the minimum information for publication of quantitative rtPCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines (Taylor et al., 2010).

To this end, cochlear tissue was collected two days after siRNALF or 4-HNE treatment, or 2, 4 and 7 days after Hes1 siRNANP treatment. siRNA-treated cultures were not exposed to 4-HNE. At least four cultured OCs in each condition were used for the analysis. Three parallel RNA extracts were prepared for each treatment. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The purity and amount of RNA was determined via spectrophotometry (Shimadzu UV1700 Spectrophotometer, Kyoto, Japan) and gel electrophoresis.

qRT-PCR was performed on an Eppendorf realplex4 Real-Time PCR System (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) with SYBRGreen Gene Expression Assays (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), using Realplex software V2.0 (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). The primers for Hes1 (sc-270146-PR) and Hes5 (sc-72197-PR) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Santa Cruz, CA). The primer sequences for Atoh1 were as follows: forward, 5′-AGA TCT ACA TCA ACG CTC TGT C-3′; reverse, 5′-ACT GGC CTC ATC AGA GTC ACT G-3′. Primers specific to mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as a reference control. For each gene, triplicate qRT-PCR reactions were assayed. To estimate changes in mRNA expression levels after ototoxic trauma, the fold change for each gene was determined by the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Data from cultures that had been incubated with either 4-HNE or siRNA were normalized to untreated controls or scRNA-treated controls, respectively (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Hes1 or Hes5 siRNA treatment inhibited Hes1 or Hes5 mRNA expression, respectively, and up-regulated Atoh1 mRNA expression in OC cultures as analyzed by qRTPCR. As shown in graph A, the mRNA levels were significantly reduced 2 days after application of the siRNALF (p < 0.001 or 0.01). A significant up-regulation of Atoh1 and down-regulation of Hes1 mRNA were observed at day 7 (day 8 in vitro, all p < 0.05) but not at day 2 or day 4 (all p > 0.05) after 200 μg/ml Hes1 siRNANP treatment (B). ***, ** and * indicate p < 0.001, 0.01 and 0.05, respectively. Error bars represent standard error of the means.

Fixation, staining and HC counting in cochleae and maculae

For HC counting, organotypic cultures were fixed in 4% formaldehyde diluted in PBS for two hours at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS, the tissues were incubated with 0.01% TRITC-labeled phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 30 min in the dark, washed three times with PBS, and flat mounted in anti-fade medium on glass slides.

The stereocilia and the cuticular plates of HCs in the cochlea and maculae were examined by fluorescence microscopy as described previously (Ylikoski et al., 1992). To estimate HC numbers, we counted hair bundles and/or cuticular plates under 40X magnification (Olympus BX51, Melville, NY). In the cochleae, two regions from each turn (basal and middle turns, 100 μm in each region ≈ 1.67% of basilar membrane length) were randomly chosen, and the number of inner and outer HCs (IHCs and OHCs, respectively) within each region was estimated and statistically analyzed (Guzman et al., 2006; Ruiz et al., 2006; Takebayashi et al., 2007). In the maculae, four to five areas (50×50 μm2 per area) were randomly chosen from the striolar and edge regions, and the number of HCs within each area was estimated and statistically analyzed.

siRNA treatment was initiated 24 hours after 4-HNE exposure. To estimate HC numbers prior to siRNA treatment, OC cultures were collected 24 hours after exposure to 450 μM 4-HNE exposure. The cultures were fixed and stained with TRITC-labeled phalloidin, and HC numbers were estimated as detailed above.

HC marker immunostaining in p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mouse pup inner ears

HC recovery in the cultured OC after siRNA treatment could be the result of direct transdifferention from SCs (Izumikawa et al., 2005 and 2008; Lin et al., 2011). To test this hypothesis, we used mouse pups from p27kip1/-green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgenic mice (kindly supplied by the Segil lab at the House Ear Institute, Los Angeles, CA). In this transgenic mouse, GFP expression is observed in all types of SCs but not in HCs. Indeed, more than 95% of Hoechst-stained nuclei in OC constituent cells were GFP positive (White et al., 2006 and Doetzlhofer et al., 2006). In these SCs, GFP is observed in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, owing to the fact that GFP can passively diffuse across nuclear pore complexes (Wei et al., 2003; Seibel et al., 2007).

Harvesting and subsequent culturing of cochlear and macular tissues from p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mouse pups were conducted using the same procedures as detailed above. A group of cochleae and maculae were exposed to toxin (4-HNE or neomycin) or siRNA (scRNA, Hes1 siRNALF or Hes1 siRNANP) alone or toxin (4-HNE or neomycin) and siRNA (scRNA, Hes1 siRNALF or Hes1 siRNANP). Cochleae and maculae that were cultured in the absence of toxin and siRNA served as untreated controls. A HC-specific marker, myosin VIIa, was used to identify HCs in the organotypic cultures. New HCs that trans-differentiated from pre-existing SCs would be predicted to have GFP in their nuclei and exhibit myosin VIIa-positive staining in their cytoplasm (Doetzlhofer et al., 2006). Cultured cochleae and maculae were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS at day 5 to 7 in vitro. After washing with PBS, the tissues were blocked in 1% BSA in 1% PBS/T and then incubated with rabbit anti-myosin VIIa (1:12.5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the tissues were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4 °C. The tissues were flat mounted in anti-fade medium on glass slides. Stacks of optical sections (z-series) obtained by confocal microscopy (Leica SP2 confocal microscope, Heidenberg, Germany) were used for evaluating co-expression of the two fluorescent markers in these tissues. Myosin VIIa positive HCs (red) co-expressing nuclear p27kip1/-GFP (green) were considered to be HCs trans-differentiated from SCs (Doetzlhofer et al., 2006).

Although low levels of p27kip1 mRNA have been detected by rtPCR, no detectable protein levels of p27kip1 have been observed in auditory HCs at postnatal day 7 (P7). However, some utricular HCs have been shown to weakly express p27kip1 protein at this developmental stage (Laine et al., 2010). To determine the p27kip1/-GFP expression patterns in p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mice, fresh-fixed OCs and maculae from p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mice were examined at P9, the developmental stage at which the in vitro transdifferentiation of SCs was observed (detailed in Results). Inner ears were harvested from p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mouse pups and fixed immediately in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Post-fixation, OCs were dissected out in PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-myosin VIIa IgG to label HCs. Expression patterns of p27kip1/-GFP and myosin VIIa were characterized using confocal microscopy as described above.

SC labeling with anti-Jagged1 antibody

Previous studies have shown that the increases in HC numbers within inner ear tissues following manipulation of the Notch pathway arise at the expense of pre-existing SCs (Collado et al., 2011; Kiernan et al., 2005; Takebayashi et al., 2007). In the present study, a significant increase of HCs was observed after treatment of siRNA. If this was caused by transdifferentiation of SCs into HCs, a significant decrease in the number of SCs should occur. To address this issue, at least six cultured OCs were harvested from each condition (untreated cultures, scRNALF, Hes1 siRNALF, 4-HNE and scRNALF, 4-HNE and Hes1 siRNALF, as detailed above) at day 8 in vitro, and serial vertical cryosections (10 μm of thickness) were obtained from the middle turns for immunostaining with the SC marker, Jagged1. The sections were immunolabeled with goat anti-Jagged1 antibody (1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-myosin VIIa (1:12.5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor® 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor® 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (each at 1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. Images were acquired from serial sections on a Leica SP2 confocal microscope (Heidenberg, Germany). Jag1 positive cells in OCs on each cross-section were counted and statistically analyzed as described previously (Takebayashi et al., 2007).

BrdU labeling in the cultured OC

Previous studies demonstrated increased SC proliferation following Notch pathway manipulation in either mouse cochleae (Kiernan et al., 2005; Takebayashi et al., 2007) or within the lateral line of zebrafish (Ma et al., 2008). BrdU labeling was conducted to study cell proliferation in the cultured cochlear tissue after exposure to 4-HNE (400 μM) and/or treatment with siRNA. After a 4-day incubation period, 10 μg/ml BrdU was added to the organotypic cultures for 2 hours at 37 °C, and the tissues were then fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS. For BrdU staining, tissues were incubated in 2 M HCl for 30 minutes at 37 °C. The tissues were then blocked with 1% BSA + 5% normal serum for 1 hour and incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 mouse anti-BrdU antibody (1:200 dilution, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in the blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Cultures in which no BrdU was added were used as negative controls. The tissues were washed three times in PBST (0.2% Tween in PBS) and mounted onto slides for fluorescence microscopy.

To identify the types of cells that exhibited positive BrdU staining, fixed OC cultures were immersed in 30% sucrose in PBS overnignt, and middle turns of OCs were cryosected at 10 μm. After incubation with anti-BrdU antibody, the cryosections were then incubated with rabbit anti-myosin VIIa antibody (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA) followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor® 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight at 4 °C. The tissues were then examined by confoal microscopy as described above.

Statistical analysis

One way ANOVA (SPSS 14.0 for windows) and a post hoc test (Tukey HSD) were used to determine if there were statistically significant differences among groups and between each of the groups in the HC quantification analyses. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant in the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

NPs or siRNA are readily taken up in cultured OCs in vitro

As shown in Fig. 1A, different sized clusters of PLGA coumarin NPs (green) were detectable by confocal microscopy within both Jag1 positive (arrows in Fig. 1A) and negative (arrowheads in Fig. 1A) dissociated OC cells after NP exposure. NPs were detected in 13.01-14.29% of Jag1 positive and 13.01-13.43% Jag1 negative cells at 12 or 24 hours after NP exposure (p > 0.05). A greater number of Jag1 positive cells (23.08%) contained NPs at 48 hours than at 24 hours after NP exposure (p < 0.05), indicative of a pattern of progressive NP uptake by SCs. A modest increase (17.46%) of Jag1 negative cells contained NPs at 48 hours after NP exposure, yet the perceived increase was not statistically significant compared to 12 or 24 hours (all p > 0.05, Fig. 1D). However, the true extent of OC cells taking up NPs may be higher than we observed due to the fact that the visualization of single, unclusted NPs are not within the resolution limits of the microscope. No NP clusters were observed in untreated cells (data not shown).

FAM labeled scRNA (FAM scRNA) was detected in 44.61% of OC cells after an incubation period of 48 hours (Fig. 1B and D). At this time, more Jag1 positive cells (55.35%, arrows in Fig. 1B) contained siRNA than Jag1 negative cells (38.77%, arrowhead in Fig. 1B, p < 0.05). The location of transfected cells, including both Jag1 positive and negative cells, in cross sections of OCs is shown in Fig. 2C. These data demonstrate that both PLGA-formulated nanoparticles and lipofected double-stranded RNA molecules are readily taken up in the targeted tissue of interest.

siRNA to Hes1 and Hes5 or Hes1 siRNANP down-regulate targeted transcripts and up-regulate Atoh1 mRNA in cultured cochleae

In comparison to scRNALF controls, Hes1 mRNA expression was inhibited by 62% after Hes1 siRNALF treatment (p < 0.001). Hes5 mRNA expression was inhibited by 66% after Hes5 siRNALF treatment (p < 0.01) based on qRT-PCR data (Fig. 2A). Under these conditions, no cross-inhibition of the two Hes genes was observed (all p > 0.05). Hes1 siRNALF induced marked up-regulation of Atoh1 mRNA (~4-fold, p < 0.001). Hes5 siRNALF also induced significant up-regulation of Atoh1 mRNA (~2-fold, p < 0.01). 4-HNE treatment alone did not induce significant changes in Hes1, Hes5, or Atoh1 mRNA expression compared to untreated cultures (all p > 0.05, Fig. 2A).

Hes1 siRNA encapsulated within PLGA NPs also resulted in significant down-regulation of Hes1 mRNA and up-regulation of Atoh1 mRNA levels, although the effects were not clearly discernible until seven days after low dose of (200 μg/ml) Hes1 siRNANP treatment in OC tissues (all p < 0.05), suggesting slow release of siRNA from NPs. A high dose (600 μg/ml) Hes1 siRNANP treatment induced significant down-regulation of Hes1 mRNA (0.38 fold) and up-regulation of Atoh1 mRNA (1.63 fold) levels 4 days after NP treatment compared to scRNANP controls, respectively (all p < 0.05). Such significant changes in the mRNA levels were not observed in the OCs treated with 200-600 μg/ml NPs for 2 days or 200-400 μg/ml NPs for 4 days (all p > 0.05). Throughout the analytical timecourse, Hes1 siRNANP did not alter expression pattern of Hes5 (all p > 0.05, Fig. 2B). These results are consistent with the observation that blockage of Notch signaling is accompanied with up-regulation of Atoh1 transcription (Collado et al., 2011).

siRNA to Hes1 or Hes1/5 results in supernumerary HCs in non-toxin treated OC cultures

Quantification of HCs in the middle turn of cochlear cultures from P3 mice treated with Hes1 or Hes1/5 siRNALF consistently demonstrated atypically high IHC numbers (arrowheads in Figs. 3G and 4). We consistently observed supernumerary IHCs which produced about a 53% (Hes1 siRNALF) or 57% (Hes1/5 siRNALF) increase in total IHC numbers per unit of basilar membrane in the middle turns (all p < 0.001, Fig. 4). In addition, Hes1 siRNALF and Hes1/5 siRNALF induced approximately 29% and 20% increases in OHC numbers, respectively (all p < 0.001, Fig. 4), as well as multiple areas where more than three rows of OHCs were seen in the middle turn (arrows in Fig. 3G). There were also areas outside of the OC where there appeared to be a small number of ectopic HCs, as determined by the presence of a cuticular plate and stereociliary bundles (data not shown). An increase in HC numbers was not observed in the basal turns (all p > 0.05, Fig. 4). These results were obtained using the standard transfection reagent JetSI™ 10 mM. scRNALF control experiments using the same transfection reagent were also performed, and no increases in IHC or OHC numbers were observed under these conditions (Figs. 3B and 5).

Figure 3.

Effects of siRNA treatment on HCs in OC cultures. Examples of phalloidin staining in the middle turn of untreated neonatal mouse OC cultures (A) or in OC cultures treated with scRNALF alone (B), scRNANP alone (C), 4-HNE alone (D), 4-HNE plus scRNALF (E), 4-HNE plus scRNANP (F), Hes1 siRNALF alone (G), 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNALF (H) or 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNANP (I). All images were taken from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro. Three rows of OHCs and one row of IHCs were observed in OCs from the untreated cultures (A) and scRNA-treated cultures (B and C). One row of IHCs and few, dispersed OHCs (open arrowheads in D and E) were observed in 4-HNE treated (D) and 4-HNE plus scRNA treated (E and F) OCs. Extra OHCs (arrows in G-I) and IHCs (arrowheads in G-I) were observed in OCs treated with Hes1 siRNALF alone (G) or in OCs treated with 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNA (H and I) OCs. Scale bar = 10 μm in F for A-I.

Figure. 4.

Hes1 siRNALF significantly increased HC numbers in OCs from neonatal mice. Compared to untreated cultures, treatment of OC cultures with Hes1 siRNALF or Hes1/5 siRNALF resulted in a significant increase in the number of IHCs and OHCs in the middle turn (***, all p < 0.001) but not in the basal turn (all p > 0.05). There is a significant difference between OHC numbers in the Hes1 siRNALF and Hes1/5 siRNALF groups (#, p < 0.05) in the middle turn. *** indicate p < 0.001 compared to the untreated cultures. # indicates p < 0.05 when the Hes1 siRNALF group is compared to the Hes1/5 siRNALF group. Error bars represent standard error of the means (numbers in the brackets indicate the number of OCs in which HCs were counted). These data were obtained from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

Figure 5.

scRNA had no significant impact on HC numbers in untreated or 4-HNE (475 μM) treated OC cultures. scRNA treatment did not change HC numbers in the absence of 4-HNE (scRNALF or scRNANP alone) or in 4-HNE-exposed cultures (4-HNE plus scRNALF or scRNANP) compared to the untreated cultures or the cultures expose to 4-HNE alone, respectively (all p > 0.05). There was a significant reduction in the number of OHCs and IHCs after 4-HNE exposure compared to the untreated cultures (*** and * indicate p < 0.001 and 0.05, respectively). Error bars represent standard error of the means (numbers in the brackets in F indicate the number of OCs in which HCs were counted). These data were obtained from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

siRNA to Hes1 increases HC numbers in OC cultures exposed to 4-HNE

We estimated the number of OHCs eliminated by the toxin before the siRNA treatment was initiated. Twenty-four hours after 4-HNE (450 μM) exposure and prior to siRNA treatment, an approximately 70% reduction in the number of OHCs was observed in the middle turns, and an approximately 76% reduction in the number of the OHCs was observed in the basal turns. After eight days in culture, 4-HNE (100-475 μM) consistently eliminated 80-89% of the OHCs in the middle turns of OCs, while most of the IHCs remained intact (Fig. 3D). We repeated the toxin exposure experiments three times and always observed an approximately 80 ± 5% reduction in the number of OHCs. Significant reduction in the number of IHCs was only observed after exposure to a high dose of 4-HNE (475 μM, p < 0.05, 0.01 or 0.001, Figs. 5 and 6).

Figure 6.

Hes1 siRNALF treatment significantly increased HC numbers in 4-HNE (100-475 μM) exposed OC cultures. 4-HNE treatment significantly decreased OHC numbers in the middle and basal turns (all p < 0.001), while only high doses of 4-HNE (475 μM) significantly decreased IHC numbers in the middle and the basal turns compared to the untreated cultures (**or ***, p < 0.01 or 0.001). Treatment of 4-HNE damaged OC cultures with Hes1 siRNALF (20 nM) resulted in a significant increase in IHCs and OHCs in the middle turn (# or ###, p < 0.05 or 0.001) at all doses of 4-HNE tested. Treatment of 4-HNE damaged OC cultures with Hes1/5 siRNALF resulted in a significant increase in IHCs in the middle turn (p < 0.001) but not in OHCs (p > 0.05) compared to cultures treated with 4-HNE alone. Increased OHC and IHC numbers were not observed in the basal turn after 4-HNE plus Hes1 or Hes1/5 siRNALF treatment (all p > 0.05). ***and ** indicate p < 0.001 and 0.01, respectively, compared to untreated cultures. ### and # indicate p < 0.001 and 0.05, respectively, compared to each dose of 4-HNE only treated cultures. Error bars represent standard error of the means (numbers in the brackets indicate the number of cochleae in which HCs were counted). These data were obtained from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

However, when 4-HNE-ablated OCs were subsequently cultured with Hes1 siRNA, using a standard transfection reagent (JetSI™ 10 mM), we consistently observed a marked increase in the number of OHCs in the middle turn compared to ototoxin-treated cultures that had been subsequently treated with scRNA (Figs. 3E, F and H, 5 and 6). In general, the OHC population in the middle turn that was observed following this experimental treatment was organized into three parallel rows and had cuticular plates in conjunction (Fig. 3H) with orderly stereociliary bundles. This was in marked contrast to controls treated with 4-HNE alone (Fig. 3D) or 4-HNE followed by scRNALF (Fig. 3E), conditions which exhibited an 80-89% reduction in OHCs in the middle turn (Figs. 5 and 6). In addition, we observed a reproducibly higher number of IHCs in the middle turn after 4-HNE and Hes1 or Hes1/5 siRNALF treatment compared to 4-HNE alone or 4-HNE plus scRNA controls (arrowheads in Figs. 3H, 5 and 6). siRNA-induced increases in middle turn HC numbers were also seen at different doses of toxin exposure (100-475 μM 4-HNE, Fig. 6). Unexpectedly, treatment with 4-HNE plus Hes1/5 siRNALF did not increase OHCs in the middle turn to the same extent as treatment with 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNALF (29% vs. 76-83%, p < 0.001, Fig. 6). This result suggests competitive uptake or antagonistic effects between Hes1 siRNA and Hes5 siRNA. In contrast, siRNA-induced increases in OHC and IHC numbers were not seen in the basal turn under the same experimental conditions (7-17% of OHCs observed in 4-HNE plus siRNA treatment groups, all p > 0.05 compared to groups exposed to 4-HNE alone, Fig. 6).

Hes1 siRNANPs increase HC numbers in OC cultures

Treatment of non toxin-damaged OC cultures with Hes1 siRNANP (50 μg/ml) significantly increased OHC numbers in the middle turns compared to untreated cultures (p < 0.05, Fig. 7), indicating Hes1 siRNANP can also promote de novo HC generation in a non toxin-damaged culture condition. However, these effects were not seen in the basal turns (p > 0.05, Fig. 7). No significant change in HC number was found at low doses (1 or 10 μg/ml) of Hes1 siRNANP treatment in toxin-damaged OC cultures (200 μM 4-HNE) compared to 4-HNE only exposed cultures (p > 0.05, Fig. 7). Treatment of toxin-damaged (200 μM 4-HNE) OC cultures with 50 μg/ml Hes1 siRNANP significantly increased OHC and IHC numbers in the middle turn and IHC number in the basal turn in comparison to 4-HNE alone or to 4-HNE plus the lower dose of NPs (1 or 10 μg/ml, p < 0.01 or 0.001, Fig. 7), consistent with siRNA-specific increases in HC numbers at higher doses of Hes1 siRNANP treatment (Figs. 3I and 8). However, increased HC numbers were not seen in OCs exposed to a higher dose of 4-HNE (475 μM) and subsequently treated with 100 or 200 μg/ml of Hes1 siRNANP (data not shown). This result suggested that higher doses of NPs may be needed when higher doses of toxin are applied (see dose response study below). As expected, scRNANP (50-200 μg/ml) had no impact on HC numbers in untreated OCs or in OCs exposed to 4-HNE (all p > 0.05, Figs. 3C and F, 5).

Figure 7.

Hes1 siRNA delivered by nanoparticles significantly increased HC numbers in low dose of 4-HNE (200 μM) damaged OC cultures. Treatment of non-toxin damaged OC cultures with Hes1 siRNANP (50 μg/ml) increased OHC numbers compared to untreated cultures in the middle turn (*, p < 0.05). Low doses of NP treatment (1-10 μg/ml) in 4-HNE damaged OCs did not change HC number compared to 4-HNE only exposed (all p > 0.05). Treatment of 4-HNE-damaged OC cultures with 50 μg/ml Hes1 siRNANP significantly increased IHC and OHC numbers in the middle turn and IHC number in the basal turn compared to cultures exposed to 4-HNE alone (## or ###, p < 0.01 or 0.001). No increase in OHC numbers was observed in the basal turn under these treatment conditions (all p > 0.05). ***, ** and * indicate p < 0.001, 0.01 and 0.05, respectively, compared to untreated cultures. ### and ## indicate p < 0.001 and 0.01, respectively, compared to cultures exposed to 4-HNE alone. Error bars represent standard error of the means (numbers in the brackets indicate the number of cochleae in which HCs were counted). These data were obtained from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

Figure 8.

A dose-dependent response was observed in the number of HCs in OCs treated with 450 μM 4-HNE and Hes1 siRNANP. Following 4-HNE exposure, more HCs were observed in cultured OCs as the dose of NPs was increased. High dose (600 μg/ml) Hes1 siRNANP treatment in 4-HNE damaged OCs resulted in a similar HC increase in the middle turn compared to cultures treated with 20 nM Hes1 siRNALF following 4-HNE (475 μM) exposure (P > 0.05, Fig. 7). Treatment with high dose of NPs (> 400 or 600 μg/ml) also resulted in significant OHC increase in the basal turn and IHC increase in the middle turn (# or ##, P < 0.05 or 0.01). *** and * indicate p < 0.001 and 0.05, respectively, compared to untreated cultures. ###, ## and # indicate p < 0.001, 0.01 and 0.05, respectively, compared to the 4-HNE only exposed group. Error bars represent standard error of the means (numbers in the brackets indicate the number of OC in which HCs were counted). These data were obtained from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

A dose response effect was found in the Hes1 siRNANP treatment in OC cultures

qRT-PCR analyses indicated that Hes1 siRNA encapsulated within PLGA NPs exhibits a prolonged release profile (Fig. 2B). Compared to about an 80% HC population in OC cultures treated with siRNA plus JetSI™ 10 mM transfection reagent, only about a 50% HC population was found in 50 μg/ml NP treatment (p < 0.01, Figs. 6 and 7), suggesting that a higher concentration of NPs is needed to match the results of Hes1 siRNALF treatment. To identify a NP dose that phenocopied the 20 nM Hes1 siRNALF-induced response in HC numbers over the same timecourse, cultured OCs were exposed to a high dose of 4-HNE (450 μM) and subsequently treated with increasingly higher doses (400, 600 or 800 μg/ml) of NPs. As shown in Fig. 8, a dose response effect was observed in the Hes1 siRNANP treatment strategy, such that an increased number of HCs were observed as the dose of NPs increased. A high dose (600 μg/ml) Hes1 siRNANP treatment was capable of promoting similar HC numbers in the middle turn as was observed previously for 20 nM Hes1 siRNALF in 4-HNE-ablated OCs (P > 0.05, Figs. 6 and 8). Treatment with a high dose of NPs (> 400 or 600 μg/ml) also resulted in a significant increase in OHC numbers in the basal turn and IHC numbers in the middle turn following exposure to 4-HNE (P < 0.05 or 0.01, Fig. 8).

siRNA to Hes1 increases HC numbers in macular cultures exposed to neomycin

The vestibular sensory epithelia in mammals have a limited regenerative capacity (Forge et al., 1993; Kawamoto et al., 2009; Kopke et al., 2001; Lopez et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1998). siRNA to Hes1 may increase this capacity. We tested this hypothesis in neonatal mouse macular cultures exposed to neomycin, a toxin that kills vestibular HCs.

Cell density measurements were first conducted for six utricles and six saccules from mouse pups that had been cultured without toxin or siRNA treatment and stained with phalloidin. No significant differences in cell densities were found between the utricles and the saccules in the striola or in the non-striolar (edge) regions (all p > 0.05). Therefore, cell quantification results from each of these regions in mouse utricles and saccules were combined in each experimental group and statistically analyzed (Fig. 9E). Compared to untreated cultures (Fig. 9A), HC numbers were markedly reduced in maculae after either exposure to neomycin alone (Fig. 9B) or after neomycin exposure followed by scRNALF treatment (Fig. 9C). In comparison to maculae treated with neomycin only or neomycin plus scRNALF, more HCs were found in the maculae treated with neomycin plus Hes1 siRNALF in both striola and edge regions (Fig. 9E, all p < 0.001). However more HCs observed under these conditions exhibited shorter stereocilia (arrow in Fig. 9D), perhaps indicative of an immature phenotype. The cuticular plates of the immature HCs were also stained by phalloidin (arrow in Fig. 9D).

Figure 9.

siRNA treatment significantly increased HC numbers in macular cultures following neomycin exposure. Examples of fluorescence microscopy images from mouse macular (utricle and sacule) cultures treated with neomycin only (Neo, B), neomycin plus scRNALF (Neo/Sc, C) or neomycin plus Hes1 siRNALF (Neo/Si, D). An image from an untreated macular culture is shown in A. Few HCs survived in the maculae after neomycin only (B), neomycin plus scRNALF (C) treatment. However, more HCs with short stereocilia were found in the maculae treated with Hes1 siRNALF (arrow in D). The cuticular plates (ring like staining) of the immature HCs were also stained by phalloidin (D). All images were taken from maculae that had been cultured eight days in vitro. HC numbers from each condition were counted and statistically analyzed (E). Significantly decreased HC numbers (averaged or in edge and striola areas) were found in the neomycin only treated compared to the untreated cultures (all p < 0.001). scRNALF treatment did not change HC number in neomycin damaged maculae in all areas compared to neomycin only treated (all p > 0.05). More HCs were found in the neomycin plus Hes1 siRNALF treated maculae compared to neomycin plus scRNALF in all areas (all p < 0.001). *** indicates p < 0.001 compared to the untreated cultures. ### indicates p < 0.001 compared to the neomycin plus scRNALF group. Error bars represent standard error of the means (the number of maculae counted was 6 in each group). Scale bar = 10 μm in D for A-D.

Transdifferentiation of new HCs from SCs

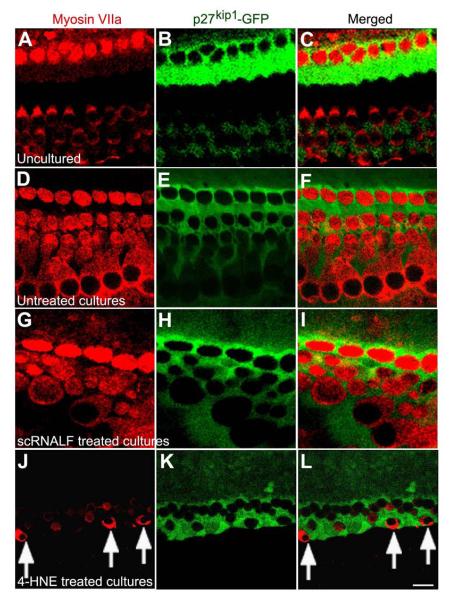

To ascertain whether Hes1 siRNA treatment induces the transdifferentiation of SCs into HCs, we examined siRNA-treated OC cultures for the presence of nascent HCs coexpressing the HC marker, myosin VIIa and the SC marker, p27kip1/GFP. p27kip1 protein is typically expressed only in SCs of the embryonic and postnatal inner ear sensory epithelia (Chen and Segil, 1999; Löwenheim et al., 1999; Minoda et al., 2007). However, some utricular HCs have been shown to weakly express p27kip1 protein at P7 (Laine et al., 2010). In the inner ear of the p27kip1/GFP transgenic mice, GFP expression is regulated by the p27kip1 promoter and is thus expressed specifically in SCs (Doetzlhofer et al., 2006; White et al., 2006). To discern whether HCs in the p27kip1/GFP transgenic mice exhibit GFP expression, we first examined the expression pattern of GFP in un-cultured OCs at an equivalent developmental stage (P9) to when Hes1 siRNA-induced transdifferentiation of supernumerary HCs was observed in vitro. In uncultured P9 OCs, the pattern of GFP expression was restricted to the SCs that surrounded Myosin VIIa-positive IHCs and OHCs, and no signal overlap was observed between these two cell populations (Fig. 10A-C). The GFP expressed in the uncultured SCs was distributed throughout the cell, exhibiting diffuse signal intensity in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, consistent with previous reports on the distribution pattern of eGFP (Chalfier et al., 1994; Kain et al., 1995). Although a similar GFP expression pattern was observed in cultured OC controls (untreated and scRNALF treated OCs, Fig. 10D-I), the uncultured P9 OCs exhibited higher intensity GFP expression in SCs that surrounded IHCs and a lower GFP signal intensity in SCs that surrounded OHCs (Fig. 10A-C). The few HCs that survived exposure to either 4-HNE (arrows in Fig. 10J-L) or neomycin (Fig. 12D-F) in the organotypic cultures did not exhibit any discernible changes in in the pattern of GFP expression compared to untreated (Figs. 10D-F and 12A-C) and scRNALF treated (Fig. 10G-I) controls as evidenced by fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 10.

Comparison of p27kip1/-GFP expression in uncultured and cultured OCs from p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mice. Examples of confocal images from untreated and uncultured OCs from p27kip1/-GFP neonatal (P9) mice (A-C), untreated OC cultures (D-F), OC cultures treated with scRNALF alone (G-I), and OC cultures treated with 4-HNE alone (J-L). HCs were stained with anti-myosin VIIa (red, column 1 at left) while SCs have GFP positive nuclei and cytoplasm (green, column 2 at middle). Images in column 3 (right) are the merged images from column 1 and column 2. All HCs have myosin VIIa positive cytoplasm with non-green nuclei in OC cultures in all conditions. Few OHCs survived in the OC treated with 4-HNE (arrows in J and L, note that most IHCs are not shown in J and L). Scale bar = 10 μm in L for A-L. Images in D-L were taken from OCs that had been cultured six days in vitro.

Figure 12.

Hes1 siRNA treatment induced transdifferentiation of SCs to new HCs in neomycin (Neo) damaged maculae of p27kip1/GFP transgenic neonatal mouse pups. Examples of confocal images from maculae without treatment (untreated cultures, A-C), treated with neomycin (D-F), or exposed to neomycin and then treated with either Hes1 siRNALF (G-I) or Hes1 siRNANP (J-L) are shown. HCs were stained with anti-myosin VIIa (red, column 1 at left) while SCs are GFP positive (green, column 2 at middle). Images in column 3 (right) are the merged images from column 1 and column 2. HCs with red cytoplasm (myosin VIIa) and green nuclei (p27kip1/-GFP) were found in maculae treated with Hes1 siRNALF (arrows in I) or Hes1 siRNANP (arrows in L), indicating that these HCs transdifferentiated from SCs. Myosin VIIa positive HCs with non-green nuclei were observed in maculae under all conditions (A-L). Fewer HCs were observed in maculae treated with neomycin alone (D-F) compared to untreated cultures (A-C). More HCs were observed in the maculae exposed to neomycin and treated with either Hes1 siRNALF (G-I) or Hes1 siRNANP (J-L) compared to neomycin only treated controls (C-F). Scale bar = 10 μm in L for A-L. All images were taken from maculae that had been cultured six days in vitro.

We exploited the fact that GFP-positive SCs exhibited a diffuse intracellular localization pattern, and surveyed the organotypic cultures for HCs that unambiguously exhibited both GFP positive nuclei and myosin VIIa positive cytoplasm. HCs with this co-expression pattern were found only in cultured OCs treated with Hes1 siRNALF alone (arrow in Fig. 11C) or in cultures exposed to 4-HNE and subsequently treated with either Hes1 siRNALF (arrows in Fig. 11F and I) or Hes1 siRNANP (arrow in Fig. 11L). These double-labeled HCs were often found in the middle turn of OC tissues at day six in vitro. These new HCs were typically located along the outside edges of OHC rows (arrows in Fig. 11C, F and L) or in the region where OHCs were normally located (arrow in Fig. 11I). HCs with GFP positive nuclei and myosin VIIa positive cytoplasm were also found in maculae treated with neomycin and Hes1 siRNALF (arrows in Fig. 12I) or neomycin and Hes1 siRNANP (arrows in Fig. 12L). Myosin VIIa positive HCs with non-green nuclei were also found in the maculae under all experimental conditions (Fig. 12) with fewer HCs surviving in maculae treated with neomycin alone (Fig. 12D-F). These findings strongly suggest that the new HCs arise from SCs (GFP positive cytoplasm and nuclei) that transdifferentiate into HCs (myosin VIIa positive cytoplasm with GFP positive nuclei) rather than from repair of injured HCs, which would not demonstrate GFP expression.

Figure 11.

Hes1 siRNA treatment induced transdifferentiation of SCs into new HCs in 4-HNE damaged OCs of p27kip1/GFP transgenic neonatal mouse pups. OC cultures were treated with Hes1 siRNALF only (A-C) or exposed to 4-HNE and subsequently treated with either Hes1 siRNALF (D-I) or Hes1 siRNANP (J-L). HCs were stained with anti-myosin VIIa (red, column 1 at left) while SCs have GFP positive nuclei and cytoplasm (green, column 2 at middle). Images in column 3 (right) are the merged images from column 1 and column 2. OHCs with red cytoplasm (myosin VIIa) and green nuclei (p27kip1/GFP) were found in OCs treated with Hes1 siRNALF alone (arrow in C), 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNALF (arrows in F and I), or 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNANP (arrow in L), indicating that these HCs transdifferentiated from SCs. Myosin VIIa positive OHCs and IHCs with non-green nuclei were found in the OCs in all conditions (AL). Scale bar = 10 μm in L for A-L. All images were taken from OCs that had been cultured six days in vitro.

Decreased numbers of SCs have previously been observed in OCs or utricles following manipulation of the Notch pathway (Collado et al., 2011; Kiernan et al., 2005; Takebayashi et al., 2007). Consistent with these previous studies, decreased numbers of Jag1-positive SCs were observed in undamaged or toxin-damaged OCs treated with Hes1 siRNALF (Fig. 13B, D and E), suggesting that the increased numbers of HCs that arise following depletion of Hes1 do so at the expense of SCs.

Figure. 13.

The number of Jag1 positive SCs decreased in OCs following Hes1 siRNA treatment. Examples of confocal images from untreated OC cultures (A), or OCs treated with Hes 1 siRNALF (B), 4-HNE plus scRNALF (C), or 4-HNE plus Hes 1 siRNALF (D) and labeled with anti-Jagged1 antibody (green, arrowheads), anti-myosin VIIa antibody (red, brackets-OHCs, arrows-IHCs), and DAPI (blue, nuclei) are shown. Note that four rows of OHCs are observed in the OC treated with either Hes1 siRNALF alone or Hes1 siRNALF plus 4-HNE (bracket in B and D) and no OHCs were observed in the cross-sectional view of the OC treated with scRNALF and 4-HNE (C). The number of Jag1 positive SCs was counted in the OCs and statistically analyzed (E). Significantly fewer Jag1 positive SCs were observed in the OC cultures treated with either Hes1 siRNALF alone or Hes1 siRNALF plus 4-HNE compared to the number of Jag1 positive cells observed in OCs treated with scRNALF alone or scRNALF plus 4-HNE treated cultures (decreased by 23.56% and 25.86%, respectively, all p < 0.01). No significant difference in Jag1 positive cell numbers was observed in OCs treated with scRNA compared to untreated cultures (p > 0.05). ** indicate p < 0.01. Scale bar = 10 μm in D for A-D. All images were taken from OCs that had been cultured eight days in vitro.

Very few BrdU positive cells were found in the OCs under all treatment conditions (Fig. 14 and data not shown), suggesting that non-mitotic HC regeneration is the major mechanism underlying the increased numbers of HCs observed following treatment with Hes1 siRNA. This is one of the two mechanisms of HC replacement described in the avian auditory organ (Duncan et al., 2006). No myosin VIIa positive HCs had BrdU positive staining (Fig. 14A’-D’). These results suggest that most of the new HCs observed upon knockdown of Hes1 mRNA trans-differentiate from SCs in the inner ear through a non-mitotic process.

Figure 14.

Few BrdU positive cells were found in the OCs after toxin and Hes1 siRNA application. Examples of BrdU labeling in untreated OC cultures (A and A’) and in OC cultures treated with either Hes1 siRNALF (B and B’), 4-HNE alone (C and C’) or 4-HNE plus Hes1 siRNALF (D and D’). Images in the left column (A-D) were from the middle turns of flat mounted OCs, and images in the right column (A’-D’) were from cross-sections of middle turn of OCs. Brackets indicate the area where HCs were located (HCs were labeled with myosin VIIa in A’-D’). Similar numbers of BrdU positive cells were found in the OCs under all conditions. The majority of BrdU positive cells were outside of the area where HCs were located (arrows in A-D and B’-D’) with only a few observed in areas where HCs were located (arrowheads in C and D). No myosin VIIa positive HCs exhibited positive BrdU staining under all conditionts (A’-D’). Scale bar = 200 μm in A-D, 10 μm in D’ for A’-D’. All images were taken from OCs that had been cultured four days in vitro.

DISCUSSION

Deafness and loss of balance are commonly caused by a loss of sensory HCs due to toxins, infection, trauma, aging, and other factors (Brigande and Heller, 2009; Cotanche, 2008). Once lost, cochlear HCs in mammals do not spontaneously regenerate, resulting in permanent hearing impairments (Bermingham-McDonogh and Rubel, 2003; Johnsson and Hawkins, 1976). In contrast to mammals, the avian auditory organ readily regenerates lost HCs and recovers hearing function (Corwin and Cotanche, 1988; Ryals and Rubel, 1988). The SCs or a subset of SCs in birds and fish have, indeed, been shown to act as HC precursors (Adler and Raphael, 1996; Ma et al., 2008). The vestibular sensory epithelia in mammals have been shown to exhibit a limited regenerative capacity (Forge et al., 1993; Kopke et al., 2001; Lopez et al., 1997; Stone et al., 1998), but the mammalian auditory sensory epithelium does not regenerate, as the cochlear SCs seemingly lose the capacity for proliferation shortly after birth (White et al., 2006). The present study demonstrated increased HC numbers in cochlear and macular explants cultured from neonatal mice that had been exposed to ototoxins and subsequently treated with siRNA against either Hes1 or Hes1/Hes5. Treatment with Hes1 or Hes5 siRNALF effectively reduced the targeted transcripts in neonatal mouse cochlear tissues and reciprocally increased the expression levels of Atoh1. The downregulation of Hes messages was accompanied by a significant increase in the number of both IHCs and OHCs under these conditions. After HC lesioning with a toxin, there was a significant increase in OHC numbers in tissues exposed to siRNA against Hes1 alone or Hes1 and Hes5 together. These HCs appeared in orderly rows in anatomically correct regions and demonstrated cuticular plates and sterocilliary bundles. The siRNA-mediated response was robust, with an approximately 5-fold increase in OHC number noted in the middle turn of toxin-damaged cultured OCs compared to toxin-ablated controls treated with scRNA (73.49% vs. 12.91%, p < 0.001, Figs. 5 and 6). After toxin-induced elimination of sensory HCs from neonatal mouse maculae, Hes1 siRNA treatment was associated with a significant increase in the apperarance of apparently immature HCs bearing short stereociliary bundles. scRNA experiments suggest that these responses were specific to the siRNA targets under investigation.

HC regeneration or protection?

Limited autonomous HC regeneration has been reported in mammalian utricles, and treatment with siRNA to Hes5 has been shown to enhance utricular HC regeneration (Forge et al., 1993 and 1998; Jung et al., 2013; Walsh et al., 2000). Consistent with previous reports, immature HCs were found in all cultured maculae in the present study. However, a significant increase in the number of HCs was only seen in maculae treated with Hes1 siRNALF (Fig. 9), suggesting siRNA to Hes1 can promote new HC formation in maculae cultured in vitro. No autonomous cochlear HC regeneration has been reported in mammals. However, new cochlear and vestibular HCs have been generated when Atoh1 was overexpressed in vitro (Zheng and Gao, 2000) and in vivo (Kawamoto et al., 2003; Staecker et al., 2007), suggesting that cochlear SCs possess an intrinsic potential to transdifferentiate into HCs through molecular manipulation of the Atoh1 pathway or the Notch pathway (Doetzlhofer et al., 2006; Hori et al., 2007; Sinkkonen et al., 2011; White et al., 2006). Consistent with these previous studies, we observed de novo HC formation induced by Hes1 and Hes5 siRNA in undamaged organotypic OC cultures (Figs. 3G and 4). However, the increased numbers of HCs induced by Hes1 siRNA following exposure of cultured OCs to the ototoxin 4-HNE could be a result of protection or regeneration. The results of the present study support the latter of these two possibilities, as evidenced by the siRNA-specific occurrence of HCs that co-expressed myosin VIIA and p27kip1/-GFP, following 4-HNE exposure and subsequent downregulation of Hes1 expresssion (Fig. 11). Moreover, there were significantly more HCs observed after siRNA treatment than were observed to have survived at the 24 hour time point post-toxin. We started siRNA treatment 24 hours after toxin exposure, at a time point when approximately 70% of OHCs were observed to be ablated by the toxin in the cultures. Thus the presence of ~70% of OHCs would suggest addition of new HCs, since only ~30% of OHCs survived the toxin. Our NP treatment regimen also supports HC regeneration. Hes1 mRNA inhibition and Atoh1 mRNA up-regulation occurred between day four and day seven of Hes1 siRNANP treatment, over a period when more than 86% of OHCs were observed to be lost in the middle turn following toxin exposure (data not shown).

The HC regeneration observed in the cultured OC may be directly attributable to stimulation of Atoh1-responsive gene expression pathways, as expression of Atoh1 significantly increased after Hes1 siRNALF or Hes1 siRNANP treatment. Others have reported that increasing Atoh1 expression by using a γ-secretase inhibitor can result in the formation of new HCs in the cochlea in vivo (Yamamoto et al., 2006). We have observed that Hes1 siRNALF treatment induced a ~four-fold increase in Atoh1 mRNA levels, supporting new HC generation through up-regulation of Atoh1. Hes5 siRNALF treatment induced only a ~2 fold upregulation of Atoh1. This result may explain why adding Hes5 siRNA did not combinatorily induce significantly more HC production (Fig. 8). Low expression of Hes5 in the inner ear after birth may also explain this phenomenon (Hartman et al., 2009).

Significant HC regeneration after exposure to ototoxic drugs and siRNA treatment was only observed in the middle turn in the OC, not in the basal turn, when 20 nM of Hes1 siRNALF or < 200 μg/ml of Hes1 siRNANP was applied. OHC regeneration in basal turns of OC explants was only observed when higher doses of Hes1 siRNANP were adminstered (Fig. 8). These results suggest a regional specificity for HC regeneration. This may be due to the fact that neonatal OC tissues are not fully developed at birth and that SCs in the basal turn of cochlear explants lose their capacity to respond to Hes1 down-regulation before the middle turn does (Shnerson et al., 1981; Tang et al., 2006). Alternatively, the basal turn of the cochlea is known to be more susceptible to ototoxins (Rybak and Ramkumar, 2007). As such, it is possible that the degree of toxicity to the SC population at the basal turn may have rendered it less responsive to Hes1 siRNA treatment, requiring significantly higher doses to elicit a transdifferentiation phenotype. However, we cannot formally rule-out that our siRNA treatment regime supports a degree of HC protection, because slightly more OHCs survived (~30% of OHC survival in the middle) when siRNA was administered (24 hours after toxin exposure) than the day when the final analyses were conducted (day 8 in vitro, ~13% of OHC survival in the middle turn, p < 0.05) in the present study. There is also a possibility that HCs were damaged to a point of not being recognizable as HCs, but did not die and then were repaired rather than regenerated. While our findings for the HES1 siRNA treatment (i.e. predominant OHC regeneration) in OC organotypic cultures differ from those reported for Hes1 knockout mice, in which increases in IHCs were the predominant feature (Zine et al., 2001 and Tateya et al., 2011), the increased complexity of the lateral inhibition mosaic that exists within the neurosensory network of the postnatal OC may elicit a unique transdifferentiation response relative to those observed during embryonic development. This may be due, at least in part, to functional redundancies imposed by the Hey family of genes within the SCs surrounding postnatal IHCs (Tateya et al., 2011). Therefore, it may be possible to induce a more robust HC regenerative response by employing siRNA therapeutic strategies that also incorporate siRNAs targeted against the Hey family of genes.

Regeneration through trans-differentiation and cell proliferation

In the mammalian vestibular system, one explanation for the disappearance of HC bundles after toxic exposure with their later reappearance is that the HCs are first injured causing a loss of the stereocilia followed by HC repair with the reconstitution of new HC bundles (Forge et al., 1993 and 1998). However, the regenerative capability of the hair bundle is lost in mammalian cochlear HCs (Jia et al., 2009). Furthermore, a degree of post-traumatic HC recovery has been documented in surviving HCs beneath the reticular laminar surface following scar formation (Sobkowicz et al., 1996). To explore these possibilities, we utilized a transgenic mouse model that specifically expresses a p27kip1/-GFP reporter construct only in cochlear and macular SCs (White et al., 2006). Based on our co-expression analyses, it is probable that some new HCs regenerate, at least in part, from p27kip1/-GFP positive SCs in both OC and macular cultures pre-treated with ototoxins. Supporting our observation, a previous study demonstrated that mammalian cochlear SCs have the capacity to divide and transdifferentiate into new HCs in vitro (White et al., 2006). A recent in vivo study also demonstrated that manipulation of Notch pathway by a γ-secretase inhibitor can induce new HC regeneration from transdifferentiation of SCs in young mice (Mizutari et al., 2013). It has been proposed that the presence of Hes1 after a lesion may prohibit the occurrence of trans-differentiation in the surviving SCs in aminoglycoside-damaged guinea pig OCs (Batts et al., 2009). In our model, we found myosin VIIa positive cells with GFP positive nuclei, which suggests that new HCs arose from transdifferentiation of SCs. The myosin VIIa positive cells with non-GFP-labeled nuclei could represent surviving HCs or transdifferentiated HCs that have matured and no longer express the p27kip1/GFP transgene, as differentiation of HCs has been shown to correspond with downregulation of this reporter (Chen and Segil, 1999). Consistent with our results, only a few myosin positive new HCs had GFP positive nuclei when p27kip1/-GFP positive SCs differentiated in vitro (Doetzlhofer, 2006). The fact that very few HCs survived in tissues exposed to toxin alone (Figs. 10J-L and 12D-F) also supports the conclusion that these new HCs are likely to represent HCs that have transdifferentiated from SCs. Therefore, we contend that siRNA-mediated reduction of Hes1 protein, in turn, allowed for enhanced Atoh1 expression, promoting a subpopulation of SCs to adopt a HC fate. However, cytoplasmic translocation of p27Kipl was found in gentamicin damaged HCs in the avian inner ear (Torchinsky et al., 1999). Therefore, there is a possibility that expression of p27Kipl/-GFP in the myosin VIIa positive cells may indicate degeneration of HCs. However, we never saw any GFP positive HCs in 4-HNE alone treated cultures. A cell lineage trace study is needed to rule out this possibility in the future.

Very few BrdU positive cells were found in the HC region of cochleae after toxin and siRNA application, suggesting a nonmitotic replacement process, which is one of the two regenerative mechanisms decribed in the avian auditory organ (Duncan et al., 2006). This result is confirmed by data from OC cultures of p27kip1/-GFP transgenic mouse pups. Normally p27kip1/-GFP is only expressed in SCs (White et al., 2006). However, myosin VIIa labeled, GFP- positive cells were observed in OCs and maculae treated with Hes1 siRNA (Figs. 11 and 12), while a decreased number of Jag1 positive SCs were observed in OCs under the same conditions (Fig. 13). All these results support a process of HC transdifferentiation from existing SCs in the absence of widespread proliferation. Consistent with our results, a previous study demonstrated that inhibition of the Notch pathway evoked a proliferation-independent increase in HC number in the OC (Takebayashi et al., 2007). While these results do not formally rule out the possibility that proliferation contributes to the regenerative process, they do indicate that, under the conditions tested, proliferation would have played a minor role.

Advantages of using siRNA and NPs

Using siRNA has several advantages: firstly, siRNA works at the RNA level, and no foreign DNA or viral vector are integrated into the host genome. Higher levels of siRNA molecules can be incorporated into polymer delivery carriers, and enhanced transfection can occur when compared to plasmid DNA for example (Salcher and Wagner, 2010). Silencing RNA technology is rapidly advancing to the clinic (Davis, 2010) and is being applied to the ear (Alvarado et al., 2011, Maeda et al., 2005, Mukherjea et al., 2008). In the auditory system, siRNA has previously been used to more closely study the proliferative mechanism of a cochlear cell line (Ozeki et al., 2007).

According to data generated from ongoing clinical trials, the use of siRNA to catalyze mRNA degradation may be a promising approach to prevent or treat human diseases (Castanotto and Rossi, 2009; Whitehead et al., 2009). However, delivery of siRNA is one of the most challenging problems in modern medicine. One aspect of this challenge is protecting and transfecting the siRNA into the desired target tissues. We have a developed a promising approach using a nontoxic, biodegradable PLGA polymer-based NP delivery platform (Barnes et al., 2007, Dormer et al., 2008, Du et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2010, Ge et al., 2007, Kopke et al., 2006, Mondalek et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2011, Wassel et al., 2007). Saltzman et al. discovered a methodology that significantly enhances the loading of siRNA into PLGA NPs, which are readily taken up into epithelial cells without the cytotoxicity seen with other methods (Cartiera et al., 2009; Cu and Saltzman, 2009; Woodrow et al., 2009). PLGA is a nontoxic and FDA-approved polymer for other applications. Using these PLGA NPs, Woodrow and colleagues reported substantial silencing of target transcripts in vivo with low toxicity after topical delivery to a sensitive epithelial tissue (Woodrow et al., 2009), providing excellent intracellular delivery and transfection efficiency. In the present study, we used lipofected siRNA targeting Hes1 and Hes5 or Hes1 siRNANP (without transfection reagent) to inhibit Hes genes in toxin-exposed OCs and maculae (utricles and saccules) from neonatal mouse pups. An increased number of HCs was found in siRNA treated cochleae and maculae after toxin damage compared to those exposed to toxin alone. Therefore, siRNA targeting of Hes genes may be an effective strategy for the post-traumatic regeneration of mammalian HCs in vivo in the future. PLGA NPs can cross the round window membrane of the inner ear in vitro and in vivo (Du et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2010; Ge et al., 2007), suggesting that PLGA NP-mediated inner ear delivery of siRNAs against these target genes may be a viable clinical approach to accomplish this aim.

This approach may have advantages over other regenerative approaches in terms of translation to the clinic. The approach described in our study avoids the use of viral vectors, which could pose a safety hazard (Bergmans et al., 2008). Encapsulating siRNA into NPs likely enhances siRNA transfection through cell uptake of the NPs and protection of the siRNA from extracellular and intracellular degradation, which ultimately allows for a degree of sustained siRNA release from the NPs by diffusion and hydrolysis of the polymer. The NP formulation used in the experiments described herein is nontoxic to delicate epithelial tissues (Cu et al., 2011; Woodrow et al., 2009). Consistent with these prior findings, scRNANP did not exhibit any discernible signs of intrinsic toxicity to inner ear tissues cultured in vitro (Figs. 3 and 5).

The results presented in this study indicate that Hes1 siRNAs are potential therapeutic molecules that could possibly regenerate new HCs in the inner ear. Whether these new HCs are functional remains to be tested. However, new HCs regenerated from manipulation of the Notch pathway has previously been shown to correlate with partial hearing recovery in mouse ears damaged by noise exposure (Mizutari et al., 2013). Nonetheless, additional experimentation needs to be performed to confirm that this regenerative phenotype can occur in vivo in adult tissues with an accompanying recovery of function.

>New hair cells can be regenerated in the inner ear by manuplating the Notch pathway. >siRNA to Hes genes decreased Hes1 mRNA and up-regulated Atoh1 expression. >Hair cells recovered in cultured inner ears treated with toxins/siRNA formulations. >Hes siRNAs delivered using a suitable vehicle are potential therapeutic molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by grants from Hough Ear Institute and Integris Health, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma (RDK). The authors would like to thank Dr. Neil Segil at House Ear Institute for providing p27kip1/GFP transgenic mice and Jim Henthorn at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center for assistance with confocal microscopy. We are also very grateful to Dr. Douglas Cotanche at Boston University School of Medicine for his thoughtful review of and suggestions for this manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HC

hair cell

- Hes1 and Hes5

hairy and enhancer of split 1 and 5

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- NP

nanoparticle

- OC

the organ of Corti

- PLGA

poly(lactide-co-glycolide acid)

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SC

supporting cell

- scRNA

scrambled siRNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- LF

lipofection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adler HJ, Raphael Y. New hair cells arise from supporting cell conversion in the acoustically damaged chick inner ear. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;205:17–20. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado DM, Hawkins RD, Bashiardes S, Veile RA, Ku YC, Powder KE, Spriggs MK, Speck JD, Warchol ME, Lovett M. An RNA interference-based screen of transcription factor genes identifies pathways necessary for sensory regeneration in the avian inner ear. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:4535–4543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5456-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes AL, Wassel RA, Mondalek F, Chen K, Dormer KJ, Kopke RD. Magnetic characterization of superparamagnetic nanoparticles pulled through model membranes. Biomagn. Res. Technol. 2007;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-044X-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batts SA, Shoemaker CR, Raphael Y. Notch signaling and Hes labeling in the normal and drug-damaged organ of Corti. Hear. Res. 2009;249:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmans H, Logie C, Van Maanen K, Hermsen H, Meredyth M, Van Der Vlugt C. Identification of potentially hazardous human gene products in GMO risk assessment. Environ. Biosafety Res. 2008;7:1–9. doi: 10.1051/ebr:2008001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham NA, Hassan BA, Price SD, Vollrath MA, Ben-Arie N, Eatock RA, Bellen HJ, Lysakowski A, Zoghbi HY. Math1: an essential gene for the generation of inner ear hair cells. Science. 1999;284:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermingham-McDonogh O, Rubel EW. Hair cell regeneration: winging our way towards a sound future. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigande JV, Heller S. Quo vadis, hair cell regeneration? Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:679–685. doi: 10.1038/nn.2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartiera MS, Johnson KM, Rajendran V, Caplan MJ, Saltzman WM. The uptake and intracellular fate of PLGA nanoparticles in epithelial cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2790–2798. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. The promises and pitfalls of RNA-interference-based therapeutics. Nature. 2009;457:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Segil N. p27(Kip1) links cell proliferation to morphogenesis in the developing organ of Corti. Development. 1999;126:1581–1590. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.8.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CJ, Saltzman WM. Enhanced siRNA delivery into cells by exploiting the synergy between targeting ligands and cell-penetrating peptides. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6194–6203. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado MS, Thiede BR, Baker W, Askew C, Igbani LM, Corwin JT. The postnatal accumulation of junctional E-cadherin is inversely correlated with the capacity for supporting cells to convert directly into sensory hair cells in mammalian balance organs. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11855–11866. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2525-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin JT, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA. Genetic and pharmacological intervention for treatment/prevention of hearing loss. J. Commun. Disord. 2008;41:421–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cu Y, Booth CJ, Saltzman WM. In vivo distribution of surface-modified PLGA nanoparticles following intravaginal delivery. J. Control. Release. 2011;156:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cu Y, Lemoellic C, Caplan MJ, Saltzman WM. Ligand-modified gene carriers increase uptake in target cells but reduce DNA release and transfection efficiency. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cu Y, Saltzman WM. Controlled surface modification with poly(ethylene)glycol enhances diffusion of PLGA nanoparticles in human cervical mucus. Mol. Pharm. 2009;6:173–181. doi: 10.1021/mp8001254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davda J, Labhasetwar V. Characterization of nanoparticle uptake by endothelial cells. Int. J. Pharm. 2002;233:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CH, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetzlhofer A, White P, Lee YS, Groves A, Segil N. Prospective identification and purification of hair cell and supporting cell progenitors from the embryonic cochlea. Brain Res. 2006;1091:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormer KJ, Awasti V, Galbraith W, Kopke RD, Chen K, Wassel R. Magnetically targeted, Technetium99m labeled Nanoparticles to the Inner Ear. J. Biomedical Nanotechnology. 2008;4:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Du X, Chen K, Kuriyavar S, Kopke RD, Grady BP, Bourne DH, Li W, Dormer KJ. Magnetic targeted delivery of dexamethasone acetate across the round window membrane in guinea pigs. Otol. Neurotol. 2013;34:41–47. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318277a40e. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318277a40e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]