Abstract

BACKGROUND

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), alterations in metal homeostasis, including the accumulation of metal ions in the plaques and an increase of iron in the cortex, have been well documented but the mechanisms involved are poorly understood.

OBJECTIVE

In this study, we compared the metal content in the plaques and the iron speciation in the cortex of three mouse models, two of which show neurodegeneration (5xFAD and Tg-SwDI/NOS2−/− (CVN) and one that shows very little neurodegeneration (PSAPP).

METHODS

The Fe, Cu, and Zn contents and speciation were determined using synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), respectively.

RESULTS

In the mouse models with reported significant neurodegeneration, we found that plaques contained ~25% more copper compared to the PSAPP mice. The iron content in the cortex increased at the late stage of the disease in all mouse models, but iron speciation remains unchanged.

CONCLUSIONS

The elevation of copper in the plaques and iron in the cortex is associated with AD severity, suggesting that these redox-active metal ions may be inducing oxidative damage and directly influencing neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid plaques, copper, iron, transgenic mice, X-ray fluorescence microscopy, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, infrared microscopy

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common age-related neurodegenerative disease, affecting 2% of the total population in industrialized countries [1]. Moreover, the incidence rate of AD in the US is expected to rise by 50% over the next 20 years [2]. For a number of years, altered metal ion homeostasis has been considered an important factor in the pathogenesis of AD, but little is understood about the specific mechanisms of action. Thus, determining the content, distribution, and speciation of redox-active metal ions, such as iron or copper, may prove to be useful biomarkers that are critically needed for the early diagnosis and treatment of AD.

One of the primary characteristics of AD involves the formation of plaques in the brain that are composed of misfolded amyloid-β (Aβ) protein. The accumulation of metal ions has been observed in the Aβ plaques from AD patients in several studies [3, 4]. Additionally, in vitro studies have shown that Aβ has high and low-affinity binding sites for both copper and zinc that are coordinated by three N-terminal histidine residues [5]. The affinities for copper and zinc were measured at 10−10 M [6] and 10−7 M [7], respectively, which is significantly lower than physiological levels (~100-150 μM), making metal binding in vivo possible [8]. In addition, metal-bound Aβ has been shown to be more prone to aggregation [9, 10] and may also increase oxidative stress, which may influence neurodegeneration. Collectively these studies suggest that metal ions may play an important role in the formation of plaques and in the subsequent neurodegeneration.

In a previous study by our group, we found that iron, copper, and zinc were elevated by 177%, 466%, and 339%, respectively, in human plaques [4]. In contrast, the PSAPP mouse model, which develops amyloid plaques due to an overexpression of the amyloid precursor protein, did not exhibit elevated metal in the plaques except for a small increase in zinc at the late stages of the disease [11]. However, the PSAPP mouse model does not show neurodegeneration. Thus, since copper is a redox-active metal ion, we questioned whether the copper accumulation in the human amyloid plaques was associated with neurodegeneration directly through the formation of reactive oxygen species and/or indirectly through Aβ binding and plaque formation.

Increased metal content has not just been observed in the amyloid plaques in AD, but also throughout the brain. Over twenty years ago, it was first observed that iron levels are elevated in severe human AD [12-14] and a recent study by Smith and colleagues showed that iron content in the cortex was increased at the earliest detectable signs of cognitive decline in human AD in humans and in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [15]. A recent time-course study in the PSAPP mouse model also showed elevated iron at the early stages of the disease, i.e. at the onset of plaque formation [16]. This observation is significant because elevated brain iron could be used as a diagnostic tool in AD [15, 17, 18].

In this study, we hypothesized that elevated metal content in the brain, and most notably in the amyloid plaques, is correlated with neurodegeneration in AD. In order to test this hypothesis, we used X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to compare the metal content, distribution, and speciation in the PSAPP mouse plaques to those of two other mouse models of AD with reported significant neurodegeneration, i.e. the 5xFAD and the Tg-SwDI/NOS2−/− (CVN) mouse models.

2. Materials and Methods

Three AD mouse models were used: PSAPP, 5xFAD, and CVN. The PSAPP mouse overexpresses genetic mutations in the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene and the human presenilin-1 gene, both of which are associated with AD [19, 20]. This produces a mouse model that develops human Aβ plaques between six and seven months of age but very little neurodegeneration. The 5xFAD mouse co-express human APP and human presenilin 1 with five familial AD mutations (APP K670N/M671L + I716V + V717I and PS1 M146L + L286V) and develops early-onset Aβ accumulation and fibrillar Aβ plaques in the brain starting at about two months of age [21]. They also show signs of memory loss and neurodegeneration. The third mouse model, CVN, expresses human APP harboring several familial mutations (APP K670N/M671L + E693Q + D694N) and does not produce nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2) [22]. This mouse model develops human Aβ plaques at around three months old and exhibits phospho-tau pathology, neurodegeneration, and memory loss.

End-stage AD mice from six PSAPP mice (56 weeks old), four 5xFAD mice (63 weeks old), two CVN mice (27 weeks old), and two control (B6C3F1/J) mice (56 weeks) were sacrificed and perfused with PBS. The brains were removed, immediately frozen over dry ice, and stored at −80°C. The tissues were embedded in OCT and cryosectioned at −12°C to a thickness of 30 μm. The tissue sections were carefully mounted on 4-μm-thick Ultralene film (SPEX Certiprep, Metuchen, NJ), an X-ray transparent and trace-metal-free substrate. The Ultralene film was previously stretched and glued to a Delrin ring using 3M white/gray epoxy (3M Scotch-Weld, St. Paul, MN) to provide structural support for the Ultralene film.

The tissue sections were then stained with Thioflavin S, a β-sheet-specific fluorescent dye, to determine the location of the plaques [23, 24]. Specifically, the sections were rehydrated with a 50% ethanol/nano-pure water solution within a few hours of being cut. They were then covered with a 0.006% solution of Thioflavin S in 50% ethanol/nano-pure water, which was allowed to stand for two minutes. Then they were rinsed in 50% ethanol/nano-pure water, followed by a second rinse in nano-pure water to remove any excess Thioflavin S solution. Finally, the sections were allowed to dry and were stored in a desiccator for >1 week prior to imaging. The green fluorescence from the Thioflavin S stain was visualized using a wide-band blue filter cube (excitation: 465 nm, emission: 550 nm). Thioflavin S was previously shown to not alter iron, copper, or zinc content within tissues that were measured before and after staining [11].

Prior to XFM data collection, the protein density in the plaques was determined using Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy (FTIRM). Since the plaques are denser than the surrounding tissue, the protein density was used to normalize the XFM data when quantifying the metal content, thus avoiding an overestimate of the metal content within the plaques. FTIRM images were acquired using the Continμum FTIR microscope (Thermo-Nicolet, Madison, WI) at beamline U2B at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL, Upton, NY) with 8 cm−1 spectral resolution over the mid-infrared spectral region (4000-800 cm−1). A 10 μm aperture was used with a 4 μm step size and 64 scans per point. The relative protein content at each pixel was determined by integrating the Amide II protein peak from 1490 – 1580 cm−1 with a linear baseline from 1480 – 1800 cm−1. The area under this peak is directly proportional to the amount of protein in the specimen. The relative protein density was calculated as the Amide II area on/off the plaques.

The metal concentrations within the plaques and the surrounding tissue in the cortex were determined using synchrotron XFM at the Biophysics Collaborative Access Team (BioCAT) beamline 18-ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne, IL). The energy of the incident X-ray beam was 12 keV using a Si(111) double crystal monochromator. The X-ray beam was focused to a 5 × 5 μm spot size using Kirkpatrick-Baez (KB) focusing mirrors. The specimens were placed at a 45° angle with respect to the incident X-ray beam, and the X-ray fluorescence was detected by a Ketek (Munich, Germany) single-element Si-drift detector oriented at a 90° angle from the incident beam. Energy dispersive spectra were collected at every pixel while raster scanning across the specimen at 0.5 seconds per point with a 5 μm step size. The iron, copper and zinc concentrations were quantified based on NIST thin-film standards 1832 and 1833 by integrating the peak area for each element of interest in the standards and specimens.

XFM images were analyzed by creating spatial regions of interest (ROIs) using the Thioflavin S fluorescence to determine the plaque locations. Median concentration values were calculated from all pixels in each ROI (i.e. plaque and non-plaque regions) for each element. The metal concentrations in the plaques were normalized to the relative protein content to account for the increased density within the plaques. A percentage difference in metal concentration between the plaque and non-plaque regions was calculated as described previously [4, 11].

X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) data were collected at NSLS beamline X27A from 80 eV below the iron absorption edge (7112 eV) to 250 eV above the edge, using a channel cut Si(111) monochromator. The data were collected with 10 eV steps before the edge (−80 to −10 eV), 0.5 eV steps across the edge (−10 to 25 eV), and 0.05 k steps from 25 eV to 250 eV above the edge. KB mirrors focused the beam to 10 μm (vertical) × 15 μm (horizontal), and the X-ray fluorescence was detected with a Vortex ME4 Silicon Drift Detector Array (SII nanotechnology, CA) in the same geometry as at 18-ID-D. Iron XANES data were collected from at least four areas per mouse model, both on and off the plaques, to determine the metal speciation in the plaques and the surrounding tissue. To avoid damage from excess X-ray exposure, two spectra were collected at each location and then the sample was moved by 10 μm, where two more spectra were collected. This was repeated for a total of six XANES spectra (two scans per location) for each area analyzed. To ensure that the X-ray beam was maintained within a plaque, only plaques greater than 30 μm in size were scanned.

Iron XANES spectra of the standards were acquired at NSLS beamline X3B using a sagittally focusing double crystal Si(111) monochromator (1 × 3 mm beam size). The data were collected with 10 eV steps before the edge (−180 to −10 eV), 0.5 eV steps across the edge (−10 to 25 eV), and 0.05 k steps from 25 eV to 250 eV above the edge. Four commercially available iron-containing proteins were examined: myoglobin and cytochrome c, both ferric heme-containing proteins; ferredoxin, a ferrous iron-sulfur protein; and ferritin, a complex ferric iron storage protein. These proteins contain different iron binding environments that may be encountered in a biological tissue. Protein solutions (between 0.4 and 2.2 mM) were made in a 20 mM MOPS buffer with 20% glycerol. The protein standards were transferred to 80 μL Lucite sample cells with a 12 mm by 3 mm window sealed with kapton tape and stored in liquid nitrogen until data collection. The protein solutions were maintained at ~40 K using a He Displex cryostat during data collection to prevent radiation damage. After each spectrum was collected, the beam was moved to a new spot on the sample. The X-ray fluorescence was detected using a 31-element Canberra germanium detector. A Fe metal foil was used for internal energy calibration, with the first inflection point of the reference foil edge set to 7112.0 eV. Due to differences in pre-edge features between the standards and tissue samples, X-ray edge energies for all spectra were defined as the energy at the half-max of the edge jump in the normalized data. XANES standards were also collected at beamline X27A from the magnetite (Fe3O4), which is a possible biomineral found in AD brains [25]. Linear combination fitting was performed from −20 to 100 eV using Athena software (version 0.8.056) [26] to determine the possible iron species’ in the tissue.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Mouse plaques are less dense than human plaques

In order to determine the protein density within the amyloid plaques, the relative protein content was determined with FTIRM from the area under the Amide II absorption band both in plaque and non-plaque regions. Results showed that the plaques contained an average of 1.3 times more protein than in the surrounding tissue for the 5xFAD and CVN mice, and 1.6 times more protein in the PSAPP mice. In comparison, the human plaques were denser with 2.0 times more protein within the plaques [11]. Since the human plaques form over years to decades, while the mouse plaques form on a time frame from weeks to months, it is not surprising that the human plaques have a higher protein density. Thus, the age of the plaques is likely to contribute to the protein density as more protein is added over time.

3.2 Copper in plaques increases in mouse models with neurodegeneration

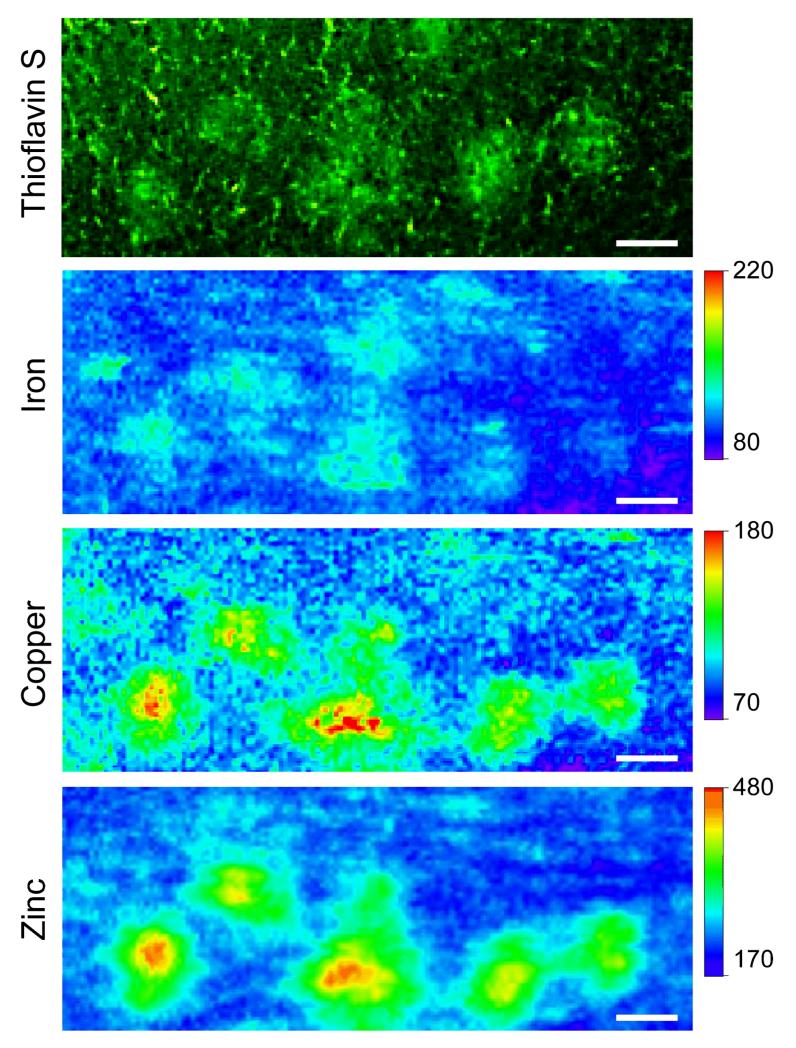

Figure 1 shows the Thioflavin-stained visible fluorescence image and the corresponding XFM images of the iron, copper, and zinc distributions in the cortex of a CVN mouse. As can be seen, elevated levels of copper and zinc are co-localized with the Thioflavin-stained plaques. Conversely, iron was not increased within the plaques.

Figure 1.

Representative plaques from a CVN mouse. (A) Epifluorescence image of the Thioflavin S stained plaques. The corresponding (B) iron, (C) copper, and (D) zinc XFM images. After density (protein) normalization, increases in copper and zinc were observed in the plaques. Concentrations are in μM. Scale bar = 45 μm.

Table 1 summarizes the metal accumulation in the human plaques compared to the three mouse models. Copper concentrations within the plaques had the most notable differences between the mouse models, where the PSAPP mice showed no increase in copper content within the plaques, while the 5xFAD and CVN mice showed a 23% and 30% increase, respectively. While the metallation levels in the plaques of the 5xFAD and CVN mice were much less than the human plaques (which showed a 466% increase), they were significantly higher than in the PSAPP mice. Together these data show that, in humans and mouse models of AD that show neurodegeneration, copper is elevated in the amyloid plaques.

Table 1.

Protein normalized ratio of iron, copper and zinc concentrations of plaque to surrounding tissue, percent difference, and age of the plaques.

| Specimen | Iron | Copper | Zinc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human [4] | Inside/Outside Plaque (Protein Normalized) |

2.79 ± 0.24 | 5.70 ± 0.49 | 4.42 ± 0.38 |

| % Difference | +177 | +466 | +339 | |

|

| ||||

| PSAPP [11] | Inside/Outside Plaque (Protein Normalized) |

0.83 ± 0.09 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 1.29 ± 0.12 |

| % Difference | −17 | −22 | +29 | |

|

| ||||

| 5xFAD | Inside/Outside Plaque (Protein Normalized) |

1.04 ± 0.20 | 1.29 ± 0.23 | 1.12 ± 0.19 |

| % Difference | +1.9 | +23 | +9.6 | |

|

| ||||

| CVN | Inside/Outside Plaque (Protein Normalized) |

0.92 ± 0.13 | 1.34 ± 0.22 | 1.39 ± 0.23 |

| % Difference | −9.5 | +30 | +31 | |

To date, copper has been implicated in the pathogenesis of AD through a number of mechanisms. For example, copper ions are released from synaptic vesicles after depolarization, providing a source of free copper ions. In AD, excitotoxicity may lead to excess free copper that is not scavenged by copper chaperones. In turn, Aβ, which is released in the glutamatergic synapse [27-29], is exposed to the free copper ions, providing an opportunity for copper to bind to the histidine-rich copper-binding domain in Aβ [6]. A number of in vitro experiments have confirmed that the presence of free copper greatly accelerates the aggregation of Aβ [9, 10]. Copper-bound Aβ is also known to generate reactive oxygen species that can increase the levels of oxidative stress, leading directly to neurodegeneration [30].

The zinc and iron contents were also examined in the plaques. An increase in zinc was observed in each of the mouse models (PSAPP = 29%; 5xFAD = 9.6%; CVN = 31%), but these values were significantly smaller than those found in the human plaques (339%). Free Zn is also released during neurotransmission and has also been shown to accelerate Aβ precipitation. However unlike copper, zinc is not redox active so it has been suggested that zinc plays a neuroprotective role by precipitating Aβ and removing the soluble and more toxic Aβ oligomers from the brain [31, 32]. In contrast to the copper and zinc contents, the iron content was not elevated in the human or mouse plaques, suggesting that iron does not bind to Aβ and/or there is no bioavailable (free) iron for this process to occur.

3.3 Plaque age is not correlated with metal content

In the PSAPP mouse model, studies have shown that initial plaque formation is not metal dependent and that only Zn ions accumulate in the plaques over the course of time [16]. Thus, it is possible that human plaques have a much higher metal content because they have many years to accumulate metal ions after formation. Here, we compared the metal content as a function of plaque age in the PSAPP, 5xFAD, and the CVN mouse models. The maximum age of the plaques was determined by the time difference between the age of initial plaque formation for each mouse model and the time of euthanization. As such, the CVN, PSAPP, and 5xFAD mice had plaques that were a maximum of 13, 32, and 48 weeks old, respectively. As can be seen in Table 1, even though the CVN mice had much younger plaques than the PSAPP mice, they contained a similar elevation in zinc and 30% more copper [16]. Based on this analysis, it does not appear that “plaque aging” is solely responsible for metal accumulation in the plaques. Rather, these findings suggest that disease-specific changes in metal ion homeostasis alter the bioavailability of free metal ions to bind to the plaques, and this process is also related to neurodegeneration.

3.4 Iron content is elevated in the cortex in three mouse models of AD

Elevated iron in the AD brain is well documented in both human specimens and mouse models [16, 33-37]. In the studies presented here, each of the AD mouse models contained approximately a two-fold increase in cortex iron concentration in comparison to the control mice (Table 2). The AD mice contained between 790 μM for the PSAPP mice and 1220 μM in the CVN mice, while the control mice contained approximately 600 μM of iron in the cortex. While the iron content in the three AD mouse models was not statistically significant from each other, there was a noticeable trend toward higher iron in the cortex in the models with reported significant neurodegeneration. The increase in iron may be a reflection of changes in metalloprotein content and metal storage within the brain that is not well understood [38]. Nonetheless, iron is ferromagnetic and detectable through MRI [39], and if increased iron can be detected at earlier stages of the disease, even before plaque formation, it could prove to be an important biomarker for AD diagnosis [39].

Table 2.

Iron content (μM) in the cortex of the three mouse models and control mice.

| Specimen | Iron (μM) |

|---|---|

| Control | 600 ± 40 |

| PSAPP | 790 ± 180 |

| 5xFAD | 960 ± 211 |

| CVN | 1212 ± 371 |

3.5 Iron speciation remains unchanged in mouse models of AD

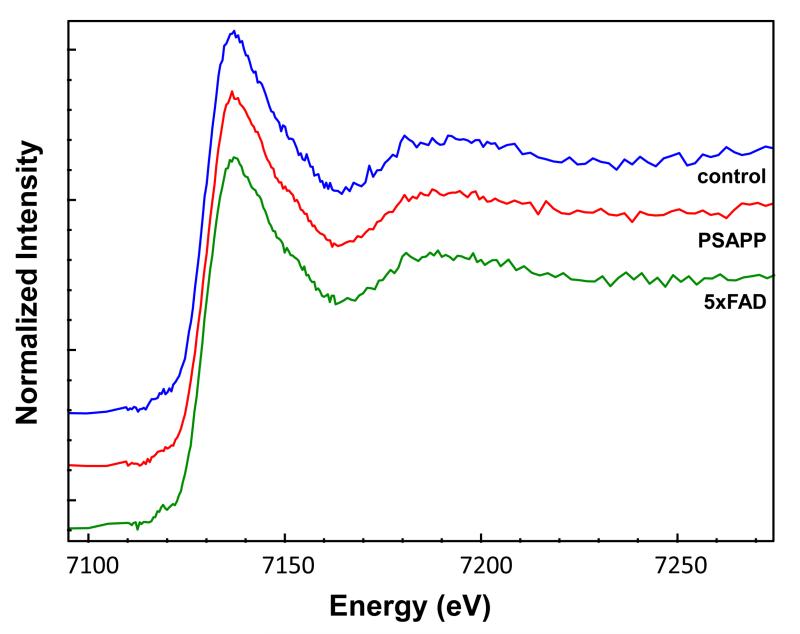

In addition to examining iron content in the three mouse models, we used X-ray absorption spectroscopy to investigate the iron speciation in order to further characterize the increase iron. Figure 2 shows representative XANES spectra from a 5xFAD mouse and its corresponding control mouse. The spectra show that there are no observable differences in the iron speciation in the cortex of the 5xFAD mice vs. the control mice. Differences were also not observed in the 5xFAD mouse plaques. In fact, there were no differences in iron speciation between any of the mouse models. These results indicate that, while the amount of brain iron increases in AD, the type of iron is not significantly altered.

Figure 2.

Iron XANES spectra from the cortex of a control, PSAPP and 5xFAD mouse. No differences were observed between the mouse models or the control mice. Spectra are offset for clarity.

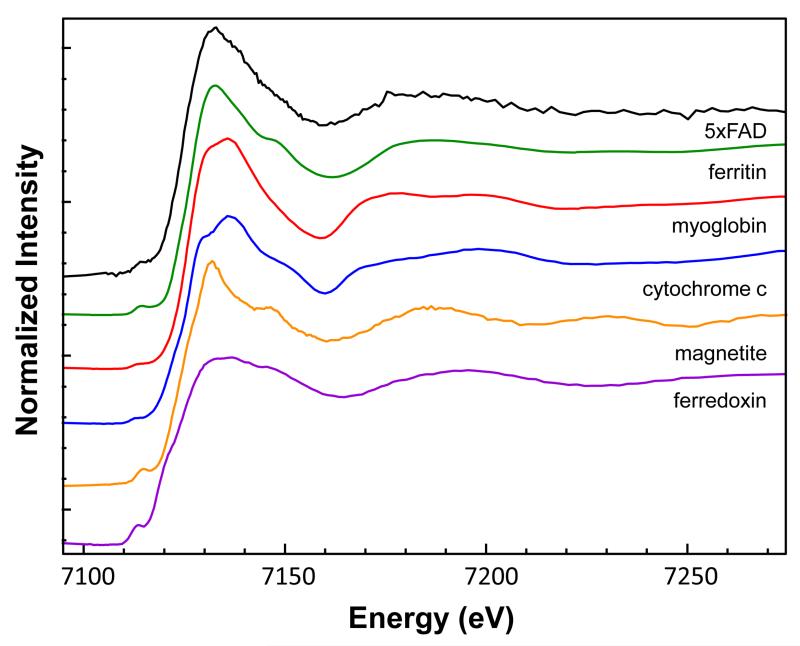

We next looked at whether the source of the increased iron could be identified. Figure 3 shows the XANES spectra from the protein standards and magnetite in comparison to the mouse brain tissue. Linear combination fitting of the standards to the mouse brain tissue indicated a combination of ferritin (0.60) and myoglobin (0.40) with a reduced χ2 = 0.12154. As can be seen, both the X-ray edge positions (Table 3) and linear combination fitting of the tissue spectra to the standards show that the data most strongly resemble ferritin, which is the most abundant iron-containing protein in the perfused (hemoglobin-removed) mouse brain, storing approximately 80% of the remaining iron predominantly in the oxidized iron (III) state [40]. There was no evidence that the iron was in the form of magnetite, as reported previously [25]. These X-ray spectroscopy results suggest that iron transport and storage in the brain may be altered in AD but future studies will be necessary to elucidate the mechanism.

Figure 3.

Iron XANES spectra from the iron standards: ferritin, myoglobin, cytochrome c, magnetite, and ferredoxin in comparison to the 5xFAD mouse. Based on linear combination fitting, the mouse speciation was found to most resemble a combination of ferritin (60%) and myoglobin (40%). Spectra are offset for clarity.

Table 3.

The iron x-ray edge positions (eV) for the mouse brain specimens and the protein and mineral standards. Due to differences in pre-edge features between the standards and tissue samples, X-ray edge energies for all spectra were defined as the energy at the half-max of the edge jump in the normalized data.

| Specimen | Iron Edge Energy (eV) |

|---|---|

| Mouse brain | 7122.8 |

| Ferredoxin | 7120.4 |

| Magnetite | 7122.2 |

| Cytochrome c | 7123.5 |

| Myoglobin | 7124.0 |

| Ferritin | 7124.0 |

4. Conclusions

The studies presented here show that copper content in the amyloid plaques is associated with neurodegeneration in humans and three mouse models of AD. We suggest that free copper that is released during neurotransmission is able to bind to the Aβ peptide in the glutamatergic synapse, enhancing plaque formation and neurotoxicity through the formation of reactive oxygen species. In addition, we also showed that iron is elevated in the cortex of the AD mouse models, but that the iron speciation does not change between the control mice or any of the AD mice. Collectively, these results indicate that preventing copper accumulation in the plaques and/or iron in the cortex is critical to neuronal survival and the redistribution of metal ions could be a viable treatment strategy for AD in the future.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Pavel Osten (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) for generously providing some of the 5xFAD mice. This research was funded by NIH Grant GM66873. The NSLS is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-98CH10886. Beamline X27A is partially supported by the U.S. Department of Energy – Geosciences (DE-FG02-92ER14244 to the University of Chicago-CARS). The Case Center for Synchrotron Biosciences operates NSLS beamline X3B with support from NIH grant P30-EB-009998. Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. BioCAT (APS Beamline 18-ID) is a National Institutes of Health-supported Research Center RR-08630.

References

- [1].Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Association A.s. 2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2012;8:131–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lovell MA, Robertson JD, Teesdale WJ, Campbell JL, Markesbery WR. Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1998;158:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Miller L, Wang Q, Telivala T, Smith R, Lanzirotti A, Miklossy J. Synchrotron-based infrared and X-ray imaging shows focalized accumulation of Cu and Zn co-localized with β-amyloid deposits in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Structural Biology. 2006;155:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Streltsov VA, Titmuss SJ, Epa VC, Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Varghese JN. The Structure of the Amyloid-β Peptide High-Affinity Copper II Binding Site in Alzheimer Disease. Biophysical journal. 2008;95:3447–3456. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Atwood CS, Scarpa RC, Huang X, Moir RD, Jones WD, Fairlie DP, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Characterization of Copper Interactions with Alzheimer Amyloid β Peptide: Identification of an Attomolar-Affinity Copper Binding Site on Amyloid β1-42. Journal of neurochemistry. 2000;75:1219–1233. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bush AI, Pettingell WH, Multhaup G, d Paradis M, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Tanzi RE. Rapid induction of Alzheimer A beta amyloid formation by zinc. Science (New York, NY) 1994;265:1464. doi: 10.1126/science.8073293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].White AR, Barnham KJ, Bush AI. Metal homeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2006;6:711–722. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huang X, Atwood CS, Moir RD, Hartshorn MA, Tanzi RE, Bush AI. Trace metal contamination initiates the apparent auto-aggregation, amyloidosis, and oligomerization of Alzheimer’s Aß peptides. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2004;9:954–960. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0602-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McColl G, Roberts BR, Gunn AP, Perez KA, Tew DJ, Masters CL, Barnham KJ, Cherny RA, Bush AI. The Caenorhabditis elegans Aβ1-42 Model of Alzheimer Disease Predominantly Expresses Aβ3-42. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:22697–22702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.028514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leskovjan AC, Lanzirotti A, Miller LM. Amyloid plaques in PSAPP mice bind less metal than plaques in human Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage. 2009;47:1215–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bartzokis G, Sultzer D, Cummings J, Holt LE, Hance DB, Henderson VW, Mintz J. In vivo evaluation of brain iron in Alzheimer disease using magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of general psychiatry. 2000;57:47–53. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Connor JR, Snyder BS, Beard JL, Fine RE, Mufson EJ. Regional distribution of iron and iron-regulatory proteins in the brain in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1992;31:327–35. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Deibel MA, Ehmann WD, Markesbery WR. Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1996;143:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Smith MA, Zhu X, Tabaton M, Liu G, McKeel, Cohen ML, Wang X, Siedlak SL, Dwyer BE, Hayashi T. Increased iron and free radical generation in preclinical Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;19:363–372. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Leskovjan AC, Kretlow A, Lanzirotti A, Barrea R, Vogt S, Miller LM. Increased brain iron coincides with early plaque formation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage. 2011;55:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bartzokis G, Tishler TA. MRI evaluation of basal ganglia ferritin iron and neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s and Huntingon’s disease. Cellular and molecular biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France) 2000;46:821–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schenck JF, Zimmerman EA, Li Z, Adak S, Saha A, Tandon R, Fish KM, Belden C, Gillen RW, Barba A, Henderson DL, Neil W, O’Keefe T. High-field magnetic resonance imaging of brain iron in Alzheimer disease. Topics in magnetic resonance imaging : TMRI. 2006;17:41–50. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245455.59912.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jankowsky JL, Slunt HH, Ratovitski T, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Borchelt DR. Co-expression of multiple transgenes in mouse CNS: a comparison of strategies. Biomolecular engineering. 2001;17:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(01)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garcia-Alloza M, Robbins EM, Zhang-Nunes SX, Purcell SM, Betensky RA, Raju S, Prada C, Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP. Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2006;24:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Colton CA, Wilcock DM, Wink DA, Davis J, Van Nostrand WE, Vitek MP. The effects of NOS2 gene deletion on mice expressing mutated human AbetaPP. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:571–87. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Saeed SM, Fine G. Thioflavin-T for amyloid detection. American journal of clinical pathology. 1967;47:588–593. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/47.5.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Westermark GT, Johnson KH, Westermark P. Staining methods for identification of amyloid in tissue. Methods in enzymology. 1999;309:3–25. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Collingwood JF, et al. High-resolution x-ray absorption spectroscopy studies of metal compounds in neurodegenerative brain tissue. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2005;17:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ravel B, Newville M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation. 2005;12:537–541. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rajan K, Colburn R, Davis J. Distribution of metal ions in the subcellular fractions of several rat brain areas. Life sciences. 1976;18:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90220-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Barnea A, Hartter DE, Cho G, Bhasker KR, Katz BM, Edwards MD. Further characterization of the process of in vitro uptake of radiolabeled copper by the rat brain. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 1990;40:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(90)80043-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kardos J, Kovács I, Hajós F, Kálmán M, Simonyi M. Nerve endings from rat brain tissue release copper upon depolarization. A possible role in regulating neuronal excitability. Neuroscience letters. 1989;103:139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90565-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Puglielli L, Friedlich AL, Setchell KDR, Nagano S, Opazo C, Cherny RA, Barnham KJ, Wade JD, Melov S, Kovacs DM. Alzheimer disease beta-amyloid activity mimics cholesterol oxidase. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:2556–2563. doi: 10.1172/JCI23610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hung YH, Bush AI, Cherny RA. Copper in the brain and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2010;15:61–76. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cuajungco MP, Goldstein LE, Nunomura A, Smith MA, Lim JT, Atwood CS, Huang X, Farrag YW, Perry G, Bush AI. Evidence that the β-amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease represent the redox-silencing and entombment of Aβ by zinc. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:19439–19442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cornett C, Markesbery W, Ehmann W. Imbalances of trace elements related to oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s disease brain. NeuroToxicology. 1998;19:339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Deibel M, Ehmann W, Markesbery W. Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease: possible relation to oxidative stress. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1996;143:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Brass SD, Chen N, Mulkern RV, Bakshi R. Magnetic resonance imaging of iron deposition in neurological disorders. Topics in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2006;17:31–31. doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245459.82782.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Haacke EM, Cheng NYC, House MJ, Liu Q, Neelavalli J, Ogg RJ, Khan A, Ayaz M, Kirsch W, Obenaus A. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2005;23:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Stankiewicz J, Panter SS, Neema M, Arora A, Batt CE, Bakshi R. Iron in chronic brain disorders: imaging and neurotherapeutic implications. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Maynard CJ, Bush AI, Masters CL, Cappai R, Li QX. Metals and amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. International journal of experimental pathology. 2005;86:147–159. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2005.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Helpern JA, Jensen J, Lee S-P, Falangola MF. Quantitative MRI assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2004;24:45–48. doi: 10.1385/JMN:24:1:045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Arosio P, Ingrassia R, Cavadini P. Ferritins: a family of molecules for iron storage, antioxidation and more. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1790:589–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]