Abstract

Runx2 is the master transcription factor for bone formation. Haploinsufficiency of RUNX2 is the genetic cause of cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) that is characterized by hypoplastic clavicles and open fontanels. In this study, we found that Pin1, peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase, is a critical regulator of Runx2 in vivo and in vitro. Pin1 mutant mice developed CCD-like phenotypes with hypoplastic clavicles and open fontanels as found in the Runx2+/− mice. In addition Runx2 protein level was significantly reduced in Pin1 mutant mice. Moreover Pin1 directly interacts with the Runx2 protein in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and subsequently stabilizes Runx2 protein. In the absence of Pin1, Runx2 is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathway. However, Pin1 overexpression strongly attenuated uniquitin-dependent Runx2 degradation. Collectively conformational change of Runx2 by Pin1 is essential for its protein stability and possibly enhances the level of active Runx2 in vivo.

Keywords: Pin1, Runx2, cleidocranial dysplasia, peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerization, bone formation

Introduction

Pin1 is a member of the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) superfamily, which catalyzes the isomerization of cis-trans conformations of rigid peptide bonds in the proline backbone, thereby altering the conformations of its target proteins (Lu et al., 2007; Lu and Zhou, 2007; Yeh and Means, 2007). Pin1 specifically recognizes phosphoserine-proline or a phosphothreonine-proline motifs (pS/T-P motif, proline-directed phosphorylation) of target substrates through its N-terminal WW domain (Lu et al., 2007; Lu and Zhou, 2007). Numerous Pin1 substrates have been identified to date, and many of these are indispensable to living organisms (Lu and Zhou, 2007). Previously, Pin1 is known to be important for bone homeostasis in aging (Lee et al., 2009), but little is known about underlying mechanism how it involves bone metabolism, particularly regarding osteogenesis.

Runx2 is master transcription factor for skeletal development and osteoblast differentiation. Disruption of Runx2 in mice not only resulted in complete lack of mineralized tissues due to impaired osteoblast commitment but showed embryonic lethality (Komori et al., 1997). Haploinsufficient mutation for RUNX2 is the genetic cause of cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) syndrome leading to impaired skeletal development characterized by hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles, delayed suture closure, short stature, and other skeletal anomalies (Mundlos et al., 1997). Although a number of mutations in the RUNX2 allele have been demonstrated decrease in its mRNA half-life, suppression of its trans-activation domain, and loss of its DNA binding activity (Yoshida et al., 2002; Yoshida et al., 2003); all of these mutations present with the same typical CCD phenotypes represented by clavicular anomaly, delayed suture closure and short stature due to the attenuated bone growth. However, it had been poorly understood how the large number of distinct mutations of RUNX2 causes CCD phenotypes.

A mouse genetic study indicated that Runx2 dosage is a critical determinant for the penetrance of the CCD phenotype (Lou et al., 2009). This study reported that a 70% decrease in the mRNA level of wild-type Runx2 could produce the CCD syndrome and that 50% of the mRNA level is the critical threshold to determine definitive phenotypes with hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. These findings suggest that the range of bone phenotypes observed in CCD patients could be due to a quantitative reduction in the functional activity of RUNX2. By contrast a higher gene dosage due to mutations with excess copy of RUNX2 also causes craniosynostosis (CS) syndrome (Greives et al., 2013; Mefford et al., 2010), an opposite extreme syndrome for bone development compared to CCD. CS causes premature mineralization of the bone growth areas including suture and hypertrophic zone of long bones. Therefore, dosage control of Runx2 expression is a crucial mechanism for both bone formation and osteoblast differentiation. Indeed, changes in the gene dosage of most Runt-related transcription factors are a common regulatory mechanism in the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including cancer (Osato et al., 1999; Song et al., 1999). This mechanism also plays a role in Drosophila sex determination (Duffy and Gergen, 1991). Collectively these results indicate that dosage control of Runx2 could be a key process to determine bone formation. Although many nuclear factors have been identified as substrates for Pin1 (Lu and Zhou, 2007), no report has identified its relationship with RUNX2. Runx2 might therefore be a target of Pin1-mediated conformational and functional alterations specifying the osteoblast differentiation and bone formation.

In this study, we observed that the CCD phenotype appears in Pin1-deficient mice with partial penetrance, and demonstrated that genetic interaction between Runx2 and Pin1 is crucially involved in the osteogenic pathway both in vivo and in vitro. Our data demonstrate that Pin1-dependent conformational alteration of Runx2 is a critical modification step for the stabilization of Runx2, thereby possibly supporting active Runx2 dosage in osteoblast differentiation. In addition, the Pin1-mediated modification also is a critical step for most of the post-phosphorylation regulatory events in MAPK signaling, including acetylation and ubiquitination, which implies that Pin1 could be a critical drug target for osteogenesis through which Runx2 dosage and activity is regulated.

Materials and Methods

Mouse strains

The Pin1 and Runx2 deficient mice were derived from the same background strain, as described previously (Fujimori et al., 1999; Komori et al., 1997). For analysis of the genetic interaction between Runx2 and Pin1, Runx2+/+ Pin1+/− and Runx2+/− Pin1+/− mice were obtained from heterozygous Runx2 and Pin1 mice, and the offspring were subsequently produced from intercrosses between Runx2+/+ Pin1+/− and Runx2+/− Pin1+/− mice. All animal experiments were conducted with the prior approval of the Seoul National University Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and Use Committee.

Cell culture and reagents

The MC3T3-E1 cells were maintained in α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM), and the HEK-293 and C2C12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (DMEM/10% FBS) supplemented with antibiotics. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were isolated from E13.5 embryos with Pin1+/+, Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− genotypes, as described previously (Fujimori et al., 1999). The MEFs were grown in DMEM/10% FBS and cells from passages 3-5 were used. For the cultivation of primary osteoblast, calvarial cells were isolated from embryos at E18.5 using sequential collagenase digestion. Briefly, calvariae of embryo were excised, rinsed twice with ice-cold α-MEM, and incubated in enzyme solution (α-MEM containing 0.25% collagenase I and 0.125% trypsin) with agitation. After consecutive enzyme treatments (6×20 min), the cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in α-MEM containing 10% FBS for cell culture. Differentiation of MC3T3-E1 and primary osteoblasts were induced by the addition of ascorbic acid (50mg/ml) and β-glycerophosphate (5 mM).

All antibodies and chemical reagents are described in the supplementary tables.

Alizarin red S staining

Cells were washed with Ca2+-free PBS for three times and fixed in 1% formaldehyde/PBS for 20 min at 4°C. After five washes with distilled water, the cells were stained in 1% alizarin red S solution for 5 min to visualize matrix calcium deposition.

Transfection

The neon transfection system (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) was used for the DNA transfection into the MC3T3-E1 or C2C12 cells. The co-transfection experiments were achieved with D-Fection reagent (Lugen Sci, Seoul, Korea) and the transfection of the HEK-293 cells was performed using Polyget reagent (SignaGen Laboratory, Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) expression analyses

Total RNA was extracted from the whole tibia of newborn mice (crushed in liquid nitrogen and homogenized) or cultured cell using the easy-BLUE™ Total RNA Extraction Kit. cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript II first-strand synthesis system Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Approximately 100 ng of RNA was used for each reaction in relative qPCR.

GST pull-down assay, immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblot analyses

Cell extracts were prepared in a lysis buffer of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 0.25% CHAPS, 1% NP-40, and 10% glycerol supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, including Na3VO4. For the acetylation and protein stabilization assays, the buffer was supplemented with 1 mM NaB or 1 μM MG132. For the immunoblot assays, the cells were lysed in buffer containing 0.2% SDS. Recombinant GST or GST-Pin1 proteins (2 μg) were incubated with lysates (1 mg) containing Runx2 proteins from the MC3T3-E1 or the transiently transfected HEK-293 cells for 2 h at 4°C. Glutathione agarose beads were then added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min. To examine the phosphorylation-dependent interactions, the cells were lysed in binding buffer without phosphatase inhibitors and the resulting cell extracts were incubated with lambda phosphatase for 30 min at room temperature prior to the GST-Pin1 pull-down assay. The precipitated proteins were then analyzed by immunoblot detection with specific antibodies. For the co-IP of Runx2 and Pin1, the Runx2 and MEK1-Ca were transiently expressed in combination with an empty vector, Pin1-WT or Pin1-W34A in HEK-293 cells. The cell lysates were incubated with anti-Pin1 antibody for 3 h, agarose beads were added, and the entire mixture was incubated for 1 h. The co-purified proteins were then subjected to immunoblot assays with specific antibodies. Detection of the acetylated or phosphorylated Runx2 was performed using the same IP conditions.

In vivo ubiquitination assay of Runx2 protein

In vivo ubiquitination assays were carried out in primary calvarial osteoblast cells that isolated from E18.5 embryos. Cells were cultured in ostegenic media for three days to induce either high abundance of Runx2 expression or osteoblast differentiation. Cells were treated with 5 μM MG132 for 6 h prior to harvest and lysed in the lysis buffer. Comparable amount of Runx2 proteins were adjusted by immunoblot and lysates were subsequently applied to immunoprecipition reaction using FK-2 antibody (anti-Ubiquitin mAb) at 4 °C for 12 h. Immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Runx2 antibody.

Whole-body skeletal staining and immunohistofluorescence studies with confocal microscopic analyses

Whole-body skeletal staining of cartilage and bone with alcian blue and alizarin red S was performed as described previously (McLeod, 1980). For histological evaluation, the bones were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, decalcified in 10% EDTA, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5-10 μm were prepared, deparaffinized and rehydrated. The tissue sections were then stained with H&E or used for immunohistofluorescence

Measurement of clavicle length

Clavicle of double skeletal stained postnatal day 1 mice were excised from the right side and measured with OsteoMeasure XP Version 1.01 (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, GA, USA) software connected to OlympusBx51 microscope according to standardized protocols excluding measurement of all aplastic calvaria. The length was then plotted in a boxplot format using Sigma Plot software version 8 (Systat Software Inc.) to show the distribution of values.

Statistical analyses

All quantitative data are presented as the mean ± SD. Each experiment was performed at least four times, and the results from one representative experiment are shown. Statistical differences were analyzed using the Student’s t test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Genetic data were evaluated with the Chi-square (χ2) test using the IBM SPSS Statistics 19.0 software.

Results

The mutation of Pin1 results in CCD-like phenotype

Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− mice exhibited a wide range of bone phenotypes at birth. Pin1 mutant mice followed the rules of normal Mendelian inheritance and exhibited normal skeletal patterning just prior to birth, but experienced a significant portion of post-natal lethality (<35% survival at weaning). Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− mice exhibit reduced mineralization at birth. Pin1 mutation causes short stature (Fig. 1A) with hypo-mineralization throughout the skeleton (Fig. 1B). Among them the calvarial bones (Fig. 1C), the clavicles (Fig. 1D), and the bones of the upper (Fig. 1E) and lower limb (Fig. 1F) were clearly affected. The bone phenotypes observed in the Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− mice resembled those typically observed in Runx2+/− mice and in human patients with CCD (Table 1). The majority of homozygous and heterozygous Pin1 mutant mice had wide open fontanels and/or hypoplastic clavicles. The upper tibial epiphyseal growth plate of the neonatal Pin1-deficient mice exhibited spatial irregularities in the chondrocyte columns, as well as shortened proliferative and hypertrophic zones (Fig. 1G). In the tibial metaphysis, the Pin1-deficient mice were found to have reduced histological staining of the extracellular matrix (Fig. 1H, colored pink) and loss of the immunofluorescence staining of type I collagen (Fig. 1I). The similarities in the craniofacial defects observed in Pin1-deficient and Runx2-deficient mutant mice suggested that these two proteins are functionally linked during the process of bone development. Immunofluorescence staining of the Runx2 protein indeed demonstrated that Runx2 levels in the developing bones of Pin1 null mice were dramatically reduced (Fig. 1J). These indicate that Pin1 is important for embryonic skeletogenesis.

Fig. 1. Impaired skeletal growth in Pin1 mutant mice.

(A) Whole bodies of wild-type and Pin1-KO littermate mice at birth (P0). (B) Skeletons from newborn mice were stained with alizarin red for calcified tissue and alcian blue for cartilage. Representative images of the (C) calvarium, (D) clavicle, (E) forelimb and (F) hindlimb of newborn mice are shown. (G) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the epiphyseal growth plates in the proximal tibia. (H) H&E staining of the metaphysis of the proximal tibia. Immunofluorescence staining of (I) procollagen type-I and (J) Runx2 in the proximal tibial epiphyseal growth plate of newborn mice.

Table 1. Frequency of CCD-like skeletal defects in Pin1-deficient mice.

| Bone phenotypes | Pin1 +/+ (n=13) |

Pin1 +/− (n=23) |

Pin1 −/− (n=15) |

Runx2+/− (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoplastic or aplastic clavicle | 0 | 8 (34.8%)* | 13 (86.7%)* | 9(100%)* |

| Wide fontanelle | 0 | 18 (66.6%) | 16 (94.1%) | 9(100%) |

| Hypoplastic interparietal bone | 0 | 22 (81%) | 16 (94.1%) | 9(100%) |

| Unossified nasal bone | 0 | 15 (55.5%) | 10 (58.8%) | 9(100%) |

The lengths of clavicles were measured as demonstrated in Materials and Methods. The clavicle lengths were compared to those of wild-type mice and the number of mice showing reduced clavicle length were counted.

Pin1 is important for osteoblast differentiation

Because of hypomineralization of bone tissues in Pin1 mutant mice, we speculated an impaired differentiation of osteoblast cells in the animal. To test this, we determined mRNA levels for important bone marker genes and compared the osteogenic potentials of osteoblast cells from Pin1 +/+ and Pin1 −/− mice. The mRNA levels of four typical bone markers and Runx2 target genes, Col1A1, alkaline phosphatase (Alp), osteocalcin (Oc) and the osteogenic transcription factor Dlx5, were dramatically reduced in the Pin1 null mouse tibia (Fig. 2A). However, the decreased Runx2 mRNA levels, about 80% that of wild type, in the Pin1 null mutants were not sufficient to explain the observed CCD phenotypes (Fig. 1), suggesting that the phenotype of Pin1 null mice was the result of translational or post-translational modifications of Runx2. The alizarin red S staining of primary cultured calvarial osteoblasts indicated that osteogenic potential was significantly down regulated in cells from Pin1−/− mice (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Pin1 deficiency suppresses osteoblast differentiation.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of bone marker genes in RNA extracted frome femur of newborn mice: Col1A1, (α1(I) collagen), Alp (alkaline phosphatase), Oc (osteocalcin), Dlx5 and Runx2. (B) Osteoblast cells isolated from 18.5 days of Pin1 +/+ and Pin1−/− mice were cultured in osteogenic medium for 21 days and analyzed by alizarin red staining. Magnified images of nodules with mineralized matrix formation were shown in lower panel.

The Pin1 mutation causes Runx2-related bone phenotypes

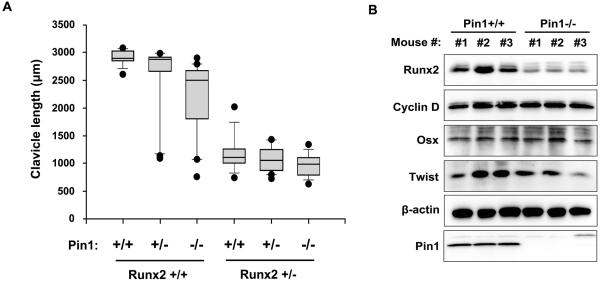

The hypoplastic clavicle is the typical phenotype characterizing CCD so we measured clavicle length of a single clavicle from all double skeletal stained mice of each genotype at P1. The measured values (μm) were plotted in a boxplot to study the distribution (Fig. 3A). Although Pin1+/+ and Pin1+/− with a Runx2+/+ background had similar median value, it was highly reduced in many Pin1 −/− mice. Pin1 mutation clearly and significantly affected the clavicle length in a Runx2+/+ background. The mice with Runx2+/− background showed not so significant change of clavicle length with deficiency of Pin1. It may be due to the reason that Runx2+/− mice already have highly reduced clavicle length and have aplastic clavicles if Runx2 protein level is reduced by more than 50% (Lou et al., 2009). Therefore it is evident from our data that clavicle lengths are decreased by Pin1-deficiency. Immunoblot analysis indicated that protein level of Runx2 was consistently downregulated in Pin1−/− mice calvarial tissue while that of cyclin D1, Twist and Osx was not (Fig. 3B), suggesting that Pin1 is required for maintaining Runx2 protein level with a relative specificity

Fig. 3. Runx2 is a critical target of Pin1 to produce bone phenotype in Pin1 mutant mice.

(A) Box plots showing distributions of the clavicle lengths (μm) of postnatal day 1 mice generated from the cross breeding of Pin1 and Runx2 double heterozygous mice. Clavicle lengths were measured with OsteoMeasure XP Version 1.01 (OsteoMetrics, Decatur, GA, USA) software fitted on a according to standardized protocols excluding measurement of all aplastic calvaria. The number of mice (n) in each group was 11, 25, 17, 9, 18, and 14 respectively. Medians are shown by solid black lines while the top and bottom box edges denote the first and third quartile. Whiskers denote the largest and smallest data within 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR). Black dots represent outliers. (B) Expression of Runx2, Pin1, Cyclin D1 and other gene products (Osterix and Twist) closely associated to CCD with clavicle hypoplasia, were quantified by western blot in calvarial tissues from 3 individual postnatal day 1 mice of Pin1+/+ and Pin1−/− genotype. Calvarial tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen following dissection. After genotyping tissues were subjected to extraction of total cellular protein in lysis buffer containing SDS which was then analyzed by western blot with indicated antibodies.

Pin1 directly binds to Runx2 protein in a phosphorylation-dependent manner

Pin1 is known to directly interact with proteins containing phosphoserine-proline motifs (Lu et al., 1999; Ranganathan et al., 1997; Yaffe et al., 1997). As expected, endogenous Runx2 protein from differentiated MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts was precipitated with recombinant glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-Pin1 fusion protein (Fig. 4A). These results indicate a molecular interaction between Runx2 and Pin1 proteins. To investigate the endogenous interaction between these two proteins, their interaction was analyzed in primary cultured calvarial osteoblasts. Runx2 protein was identified in immunoprecipitate of anti-Pin1 antibody (Fig.4B). In addition, the dephosphorylation of Runx2 by λ-phosphatase (λ-P) strongly attenuated the interaction between the two proteins (Fig. 4C), indicating that this interaction occurs in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Co-expression and immunoprecipitation analysis of epitope-tagged wild-type Pin1 (WT) and Runx2 proteins revealed that they interact in vivo in mammalian cells. The Pin1-W34A mutant (the WW domain mutant) failed to interact with Runx2 (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the WW domain of Pin1 is crucial for its interaction with Runx2, just as it is important for most of the other protein interactions with Pin1. Similar to Runx2 protein, the closely related other Runt-domain transcription factors, Runx1 and Runx3, also interact with Pin1 (Fig. 4E). Confocal microscopic analyses confirmed that two proteins are clearly co-localized in the same regions of nucleus (Fig. 4F).

Fig.4. Pin1 directly interacts with the C-terminal domain of Runx2 in a phosphorylation-dependent manner.

(A) Co-precipitation of endogenous Runx2 protein with GST-Pin1 from MC3T3-E1 cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured under osteogenic conditions for 1 day. (B) The interaction between endogenous Pin1 and Runx2 proteins in mouse primary calvarial osteoblasts. Cells were cultured in osteogenic medium for two days. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) were performed with either anti-Pin1 antibody or rabbit IgG antiserum. (C) Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between Runx2 and Pin1. Lysates containing Runx2 were incubated with lambda phosphatase (λ-P) for the dephosphorylation of Runx2 and GST pull-down assay was performed. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) of Runx2 with Pin1 in vivo. Runx2 was overexpressed with either an empty vector (-), wild-type Pin1 (WT) or mutant Pin1-W34A (WA) plasmids. An anti-Pin1 antibody was used for the Co-IP. Recombinant and endogenous Pin1 proteins are indicated by an arrowhead and an arrow, respectively. To perform the quantitative analyses of the Runx2 and Pin1 interaction, a comparable amount of the input Runx2 protein was subjected to Co-IP. (E) Determination of the interactions between Runt-domain transcription factors and Pin1. MYC-tagged Runx1, 2, and 3 were co-transfected with MEK1-Ca into HEK-293 cells. G and P indicate recombinant GST and GST-Pin1 proteins, respectively. (F) Colocalization for Runx2 (green) and Pin1 (red). EGFP-Runx2 and DsRed2-Pin1 were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells. After 24h of transfection, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde followed by confocal microscopic analyses.

Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization stabilizes Runx2

Due to significant reduced level of Runx2 in Pin1-deficent mice, we believed that Pin1 has a role in Runx2 stability. Inhibition of Pin1 enzyme activity with the potent inhibitors dipentamethylene thiuram monosulfide (DTM) (Tatara et al., 2009) or juglone strongly reduced the endogenous Runx2 protein levels in the MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 5A), supporting the hypothesis that the loss of Pin1 activity reduces Runx2 protein expression (see Fig. 1J and Fig.3B). The expression of epitope-tagged Runx2 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Pin1+/+, Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− mice indicated that Runx2 protein accumulation declines with a decrease of Pin1 expression (Fig. 5B). Transient transfection of Pin1 siRNAs, which almost completely abolished Pin1 protein expression, strongly down-regulated the steady state level of Runx2 protein (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the co-expression of Runx2 with the wild-type Pin1 (Pin1-WT), but not with the binding inactive (Pin1-W34A or Y23A) or catalytically inactive Pin1 mutant (Pin1-C113A), could increase Runx2 protein levels (Fig. 5D). Runx2 stability was compared mOB (mouse primary calvarial osteoblasts) of Pin1+/+ and Pin1−/− after cycloheximide (CHX) treatment. Runx2 half-life of was definitely decreased in Pin1−/− mOB (Fig. 5E), indicating the reduction of Runx2 protein levels in Pin1−/− mice bone tissue (see Fig. 1J and Fig.3B) is caused by the decrease of Runx2 half-life in mOB of Pin1−/− mice. This shows that the prolyl isomerase activity of Pin1 mediates the fate-determining step of Runx2 protein accumulation. Corroborating this key finding, the absence of Pin1 dramatically enhanced the ubiquitination of Runx2 in osteoblast from Pin1−/− mouse (Fig. 5F). In contrast, co-expression of wild-type Pin1 suppressed the ubiquitination of Runx2, while the expression of Pin1-C113A did not (Fig. 5G). Hence, Pin1 stabilizes Runx2 by decreasing its ubiquitination and degradation.

Fig. 5. Pin1 stabilizes Runx2.

(A) Decreased levels of endogenous Runx2 protein in bone cells after Pin1 inhibition. The chemical compounds used for Pin1 inhibition are described in Supplementary Table 2. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in osteogenic media in the presence or absence of DTM or juglone for 36 h and were then lysed for the detection of Runx2. H1-127-21-1 (Rx2-KO) cells were used as the Runx2 negative control. (B) Reduced levels of Runx2 in the Pin1 deficient MEF cells. MEF (Pin1+/+, Pin1+/− and Pin1−/−) cells were transiently transfected with a Runx2 expression vector. (C) Down-regulation of Runx2 expression by Pin1siRNA. Myc-Runx2 is transiently expressed either with control-siRNA or Pin1-siRNA in C2C12 cells. After 48h of culture, cells were harvested and Runx2 level was determined by immunoblot. (D) Overexpression of Pin1 increased Runx2 protein level while mutant Pin1 showed a dominant-negative effect. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with either an empty vector, wild-type Pin1, or a Pin1 mutant (Y23A, W34A or C113A), as described previously (Lu et al., 1999). (E) Pulse-chase experiment for determination of Runx2 protein half-life in the presence or absence of Pin1 activity. Mouse primary OBs isolated from the mice were cultured with the treatment of 40 μg/ml of cyclohexamide (CHX) for the indicated period. The remaining Runx2 protein level in the total cellular protein extracted from the cultures at the indicated time points were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Runx2 antibody. Arrowhead and asterisk indicate endogenous Runx2 and non-specific band, respectively. (F) Runx2 ubiquitination was increased in Pin1 deficient cells. Cell lysates extracted from primary calvarial osteoblasts (mOB) of Pin1+/+ and Pin1−/− embryos were subjected to immunoprecipitation with indicated antibodies. Ubiquitin-conjugated Runx2 protein level from affinity-purified bead mixtures was determined by immunoblot analysis with an anti-Runx2 antibody. (G) Suppression of Runx2 ubiquitination by Pin1 overexpression. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with HIS-Runx2 and FLAG-ubiquitin together with empty vector, wild-type Pin1 or mutant Pin1-C113A. Cells were lysed in denaturing urea lysis buffer and Runx2 protein was purified by Ni-NTA (nitrilotriacetic acid) His-tag affinity chromatography (NTA column). Ubiquitin-conjugated Runx2 protein from affinity-purified bead mixtures was examined by immunoblot analysis with anti-Ub antibodies.

Discussion

The phenotypes of the Pin1−/− mice demonstrated that the prolyl isomerization of Runx2 by Pin1 is of great importance for early bone formation. Pin1+/− and Pin1−/− newborn mice showed a range of CCD phenotypes such as abnormal development of the cranial bones and clavicle with delayed ossifications and hypomineralization of the whole skeleton. These findings indicate a causal relationship between the functional loss of Pin1 and development of CCD. Genetically, CCD results from the haploinsufficiency of RUNX2 (Mundlos et al., 1997). A previous mouse genetic study (Lou et al., 2009) reported that the functional Runx2 mRNA expression levels were critical for the CCD phenotype penetrance: a level of mRNA expression 70% below that of wild-type mice is required for development of the CCD phenotype. Importantly, we found that Pin1 mutant mice exhibit a down-regulation of the Runx2 protein expression in bone tissue. As functional loss of RUNX2 due to mutations are responsible for cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD), this decrease in Runx2 in the bone tissue of Pin1 deficient mice might have subsequently lead to the development of CCD-like phenotypes in them. Pin1 also directly interacted with Runx2 by a phosphorylation-dependent manner. These evidences indicate that genetic interaction between Runx2 and Pin1 is physiologically important in bone formation and clarify the role of Pin1 as an extrinsic regulatory enzyme influencing functional Runx2 level.

Our present study demonstrated that Pin1 played a critical role in the Runx2 protein stabilization. In the presence of normal Pin1 activity, Runx2 is highly stabilized and maintained for a longer time; however, the absence of Pin1 or the inhibition of Pin1 activity strongly attenuated Runx2 protein level. Even down regulation of Pin1 expression with siRNA, drastically inhibited Runx2 protein level, possibly demonstrating that Pin1 is an enzyme which controls the rate-limiting process of Runx2 protein stability. The control of Runx2 ubiquitination and its half-life by Pin1 is of note. Taken together, our data strongly suggest the physiological importance of Runx2 conformational change by Pin1 in regulating its functional activity.

We previously reported that phosphorylation (Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2004) and subsequent protein stabilization of Runx2 (Park et al., 2010) is required for its transactivation activity for the stimulation of osteoblast differentiation. As a matter of fact, it was reported that the genetic insufficiency of Runx2 could be overcome by osteoblast-specific overexpression of constitutively active MEK1 (MEK1-Ca) and could be exaggerated by the expression of dominant-negative MEK1 (Ge et al., 2007). These results suggested masking the effects of the genetic insufficiency of the Runx2 heterozygote throughout MAPK signaling. On the other hand it recently came to light that ERK/MAPK signaling is required for stabilization of Runx2 protein (Park et al., 2010), demonstrating that ERK/MAPK signaling accelerated Runx2 stabilization, a post-phosphorylational event, thereby preventing Runx2 from ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. Thus it could be suggested that Pin1 might be a strong candidate to mediate phosphorylation and further tran-activation of Runx2. Interestingly, Pin1 controls cell signaling as MAPK responder in fruit fly (Hsu et al., 2001). Therefore our data implicate the role of Pin1 in Runx2 control during cell signaling such as FGF2 or BMP2 signaling. Especially in cranial bone development affected by FGFR2 signaling, the CCD-like underdevelopment in the Pin1 mutant mouse thus likely results from conformational deficiency of phosphorylated Runx2.

CCD often develops in patients with phenotypic variation even in the same family. In this study, we observed that Pin1 deficiency resulted in variable expressivity of the CCD phenotype. Intriguingly, the in vivo analysis revealed a range of clavicle phenotypes in the Pin1-deficient mice. From this, it could be interpreted that Pin1 might be involved in determination of phenotypic variability. These results provide the concept that stochiometric control of Runx2 conformation could affect to phenotypic consequences. In fact Pin1 is simply a Runx2 modifying enzyme, therefore clarifying relationship between Pin1 activity and Runx2 level upon bone phenotypes could be an interesting subject for further research especially to identify the role of Pin1 in determination of phenotypic variability.

Apart from Runx2, we also identified that Pin1 commonly interacted with other Runx family members, suggesting that Pin1-mediated modification is a common regulatory mechanism for all Runx family proteins and that it likely acts to promote protein stabilization with similar manner as found in Pin1-mediated Runx2 stabilization. Indeed, changes in the gene dosage of most Runt-related transcription factors are a common regulatory mechanism in the pathogenesis of many human diseases, including cancer (Osato et al., 1999; Song et al., 1999) and sex determination of fruit fly (Duffy and Gergen, 1991). In addition, a strong correlation has also been demonstrated between Pin1 expression and tumorigenesis in various human cancers, including prostate cancer (Ayala et al., 2003) and AML (Pulikkan et al., 2010). Therefore, these findings suggest a possibility that Pin1 may play a role in hematopoiesis and tumorigenesis through the similar control of Runx1 and Runx3, respectively.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that functional interaction between Runx2 and Pin1 is an essential mode for osteogenesis. This finding is depicted in Fig. 6. Briefly, the fate of Runx2 could be determined by its conformational state via Pin1 activity. In these processes, Runx2 protein seems to progress through two different pathways towards either stabilization or fast degradation that are each dependent on Pin1. Therefore, we suggest here that modifying enzymes, such as Pin1, might represent valuable drug targets to correct abnormal Runx2 activity and to ensure the optimal fate determination of osteogenic cells in the differentiation and development of bone.

Fig. 6. Bidirectional control of Runx2 fate during bone development.

Pin1 can selectively bind the phosphorylated Runx2 peptide and immediately catalyze its prolyl isomerization, thereby inducing a conformational change in the Runx2 peptide. These Runx2 structural change(s) are important in further stabilization of functional Runx2. In contrast, Runx2 is involved in functional inactivation processes, including the ubiquitination and rapid degradation that occurs in the absence of prolyl isomerization, which in turn results in the development of CCD and reduced bone formation in vivo. Taken together, these results suggest that the Pin1-mediated Runx2 conformational change(s) could represent a binary fate-determining switch that serves to balance Runx2 activity in the development and metabolism of bone.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (20100030015), the General Researcher Program (20100010590), and the Korean-Japanese International Research Program (K20802001314-09B1200-11110) from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Ayala G, Wang D, Wulf G, Frolov A, Li R, Sowadski J, Wheeler TM, Lu KP, Bao L. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 is a novel prognostic marker in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63(19):6244–6251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JB, Gergen JP. The Drosophila segmentation gene runt acts as a position-specific numerator element necessary for the uniform expression of the sex-determining gene Sex-lethal. Genes Dev. 1991;5(12A):2176–2187. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori F, Takahashi K, Uchida C, Uchida T. Mice lacking Pin1 develop normally, but are defective in entering cell cycle from G(0) arrest. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;265(3):658–663. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge C, Xiao G, Jiang D, Franceschi RT. Critical role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-MAPK pathway in osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(5):709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greives MR, Odessey EA, Waggoner DJ, Shenaq DS, Aradhya S, Mitchell A, Whitcomb E, Warshawsky N, He TC, Reid RR. RUNX2 quadruplication: additional evidence toward a new form of syndromic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(1):126–129. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31826686d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T, McRackan D, Vincent TS, Gert de Couet H. Drosophila Pin1 prolyl isomerase Dodo is a MAP kinase signal responder during oogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(6):538–543. doi: 10.1038/35078508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim JH, Bae SC, Choi JY, Ryoo HM. The protein kinase C pathway plays a central role in the fibroblast growth factor-stimulated expression and transactivation activity of Runx2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):319–326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Park HD, Kim JH, Cho JY, Choi JY, Kim JK, Shin HI, Ryoo HM. Establishment and characterization of a stable cell line to evaluate cellular Runx2 activity. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91(6):1239–1247. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, Yagi H, Nomura S, Yamaguchi A, Sasaki K, Deguchi K, Shimizu Y, Bronson RT, Gao YH, Inada M, Sato M, Okamoto R, Kitamura Y, Yoshiki S, Kishimoto T. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89(5):755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TH, Tun-Kyi A, Shi R, Lim J, Soohoo C, Finn G, Balastik M, Pastorino L, Wulf G, Zhou XZ, Lu KP. Essential role of Pin1 in the regulation of TRF1 stability and telomere maintenance. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(1):97–105. doi: 10.1038/ncb1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y, Javed A, Hussain S, Colby J, Frederick D, Pratap J, Xie R, Gaur T, van Wijnen AJ, Jones SN, Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL. A Runx2 threshold for the cleidocranial dysplasia phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(3):556–568. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KP, Finn G, Lee TH, Nicholson LK. Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(10):619–629. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KP, Zhou XZ. The prolyl isomerase PIN1: a pivotal new twist in phosphorylation signalling and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(11):904–916. doi: 10.1038/nrm2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PJ, Zhou XZ, Shen M, Lu KP. Function of WW domains as phosphoserine- or phosphothreonine-binding modules. Science. 1999;283(5406):1325–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod MJ. Differential staining of cartilage and bone in whole mouse fetuses by alcian blue and alizarin red S. Teratology. 1980;22(3):299–301. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420220306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefford HC, Shafer N, Antonacci F, Tsai JM, Park SS, Hing AV, Rieder MJ, Smyth MD, Speltz ML, Eichler EE, Cunningham ML. Copy number variation analysis in single-suture craniosynostosis: multiple rare variants including RUNX2 duplication in two cousins with metopic craniosynostosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(9):2203–2210. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundlos S, Otto F, Mundlos C, Mulliken JB, Aylsworth AS, Albright S, Lindhout D, Cole WG, Henn W, Knoll JH, Owen MJ, Mertelsmann R, Zabel BU, Olsen BR. Mutations involving the transcription factor CBFA1 cause cleidocranial dysplasia. Cell. 1997;89(5):773–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osato M, Asou N, Abdalla E, Hoshino K, Yamasaki H, Okubo T, Suzushima H, Takatsuki K, Kanno T, Shigesada K, Ito Y. Biallelic and heterozygous point mutations in the runt domain of the AML1/PEBP2alphaB gene associated with myeloblastic leukemias. Blood. 1999;93(6):1817–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park OJ, Kim HJ, Woo KM, Baek JH, Ryoo HM. FGF2-activated ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase enhances Runx2 acetylation and stabilization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(6):3568–3574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.055053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulikkan JA, Dengler V, Peer Zada AA, Kawasaki A, Geletu M, Pasalic Z, Bohlander SK, Ryo A, Tenen DG, Behre G. Elevated PIN1 expression by C/EBPalpha-p30 blocks C/EBPalpha-induced granulocytic differentiation through c-Jun in AML. Leukemia. 2010;24(5):914–923. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R, Lu KP, Hunter T, Noel JP. Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell. 1997;89(6):875–886. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song WJ, Sullivan MG, Legare RD, Hutchings S, Tan X, Kufrin D, Ratajczak J, Resende IC, Haworth C, Hock R, Loh M, Felix C, Roy DC, Busque L, Kurnit D, Willman C, Gewirtz AM, Speck NA, Bushweller JH, Li FP, Gardiner K, Poncz M, Maris JM, Gilliland DG. Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):166–175. doi: 10.1038/13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatara Y, Lin YC, Bamba Y, Mori T, Uchida T. Dipentamethylene thiuram monosulfide is a novel inhibitor of Pin1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384(3):394–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB, Schutkowski M, Shen M, Zhou XZ, Stukenberg PT, Rahfeld JU, Xu J, Kuang J, Kirschner MW, Fischer G, Cantley LC, Lu KP. Sequence-specific and phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization: a potential mitotic regulatory mechanism. Science. 1997;278(5345):1957–1960. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ES, Means AR. PIN1, the cell cycle and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(5):381–388. doi: 10.1038/nrc2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kanegane H, Osato M, Yanagida M, Miyawaki T, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in Japanese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia demonstrates novel genotype-phenotype correlations. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(4):724–738. doi: 10.1086/342717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Kanegane H, Osato M, Yanagida M, Miyawaki T, Ito Y, Shigesada K. Functional analysis of RUNX2 mutations in cleidocranial dysplasia: novel insights into genotype-phenotype correlations. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003;30(2):184–193. doi: 10.1016/s1079-9796(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.