Introduction

Brazil currently faces a major health challenge: the pandemic scenario of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. According to Brazilian Health Ministry data, 326,000 deaths due to cardiovascular diseases (CVD) occurred in 2010, corresponding to approximately 1,000 deaths/day, 200,000 deaths due exclusively to ischemic heart and cerebrovascular diseases, reflecting a gloomy scenario far from the minimally acceptable control.

This current scenario can be attributed to many reasons, such as the insufficiency and inadequacy of public health policies for CVD prevention, leading to the well-known lack of infrastructure in primary health care, hindering the fight against preventable affections, mainly in the neediest areas.

In addition, it is worth mentioning the well-known sociocultural factors, such as the excessive consumption of high-caloric foods in association with physical inactivity, and, consequently, the development of obesity and diabetes, and excessive salt intake. Those factors contribute to the development of arterial hypertension, being decisive to the high prevalence of CVD and no opportunity to provide instructions on lifestyle changes.

The medical societies, in partnership with governments and universities, have endeavored to elaborate valuable documents containing strategic plans of CVD prevention and fight. However, simple and objective guidelines, which can be easily accessed and managed by health care personnel, are required to implement that which has been long discussed by specialists and scientists, although with modest results.

For the first time, guidelines and consensus documents, most of which already published in several other guidelines of specialties, have been gathered in a single document to provide the clinician with easy access to the recommendations for primary and secondary CVD prevention. For that, the Brazilian Society of Cardiology (SBC) has gathered specialized physicians with large experience in preventive actions to elaborate the present document.

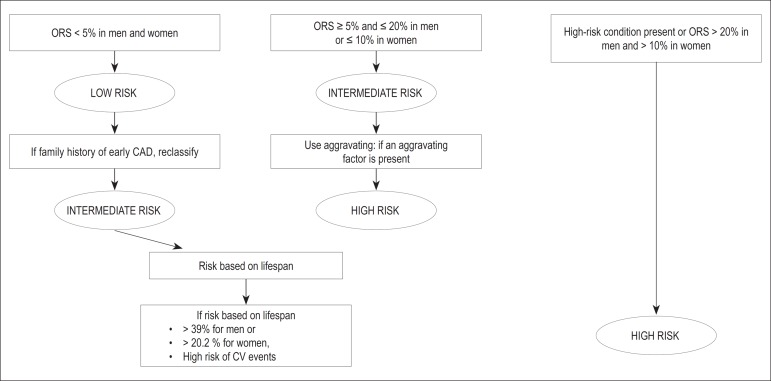

Chapter 1 presents the cardiovascular risk stratification for atherosclerosis prevention and treatment. In this chapter, the authors discuss questions such as acute coronary event as the first manifestation of atherosclerotic disease in at least half of the individuals with that complication. Thus, the identification of predisposed asymptomatic individuals is crucial to the effective prevention with correct definition of therapeutic goals, especially the criteria to identify high-risk patients (Table 1). The authors discuss the so-called risk scores, through which the overall risk is calculated, enabling the clinician to quantify and qualify the patients' individual risk, for both women (Tables 2 and 3) and men (Tables 4 and 5). The combination of those different scores allow the clinician to better estimate the risk, stratifying it gradually: presence of significant atherosclerotic disease or its equivalents; calculation of risk score; aggravating factors (Chart 1) and risk stratification based on lifespan. The authors propose a simplified algorithm for cardiovascular risk stratification, which is exemplified in Figure 1. The recommendations listed as class I and level of evidence A are few, because the other recommendations still require more comprehensive studies with long-term follow-up (Table 6).

Table 1.

Criteria to identify patients at high risk for coronary events (phase 1)

| Atherosclerotic coronary artery, cerebrovascular or obstructive peripheral diseases with clinical manifestations (cardiovascular events) and still in the subclinical form, documented by use of diagnostic methodology; |

| Arterial revascularization procedures; |

| Type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus; |

| Chronic kidney disease. |

Table 2.

Scoring according to overall risk for women

| Points | Age (years) | HDL-C | TC | SBP (untreated) | SBP (treated) | Smoking | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -3 | < 120 | ||||||

| -2 | 60+ | ||||||

| -1 | 50-59 | < 120 | |||||

| 0 | 30-34 | 45-49 | < 160 | 120-129 | No | No | |

| 1 | 35-44 | 160-199 | 130-139 | ||||

| 2 | 35-39 | < 35 | 140-149 | 120-129 | |||

| 3 | 200-239 | 130-139 | Yes | ||||

| 4 | 40-44 | 240-279 | 150-159 | Yes | |||

| 5 | 45-49 | 280+ | 160+ | 140-149 | |||

| 6 | 150-159 | ||||||

| 7 | 50-54 | 160+ | |||||

| 8 | 55-59 | ||||||

| 9 | 60-64 | ||||||

| 10 | 65-69 | ||||||

| 11 | 70-74 | ||||||

| 12 | 75+ | ||||||

| Points | Total |

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure

Table 3.

Overall cardiovascular risk in 10 years for women

| Points | Risk (%) | Points | Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤-2 | <1 | 13 | 10.0 |

| -1 | 1.0 | 14 | 11.7 |

| 0 | 1.2 | 15 | 13.7 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 16 | 15.9 |

| 2 | 1.7 | 17 | 18.5 |

| 3 | 2.0 | 18 | 21.6 |

| 4 | 2.4 | 19 | 24.8 |

| 5 | 2.8 | 20 | 28.5 |

| 6 | 3.3 | 21 + | > 30 |

| 7 | 3.9 | ||

| 8 | 4.5 | ||

| 9 | 5.3 | ||

| 10 | 6.3 | ||

| 11 | 7.3 | ||

| 12 | 8.6 |

Table 4.

Scoring according to overall risk for men

| Points | Age (years) | HDL-C | TC | SBP (untreated) | SBP (treated) | Smoking | Diabetes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -2 | 60+ | < 120 | |||||

| -1 | 50-59 | < 120 | |||||

| 0 | 30-34 | 45-49 | < 160 | 120-129 | No | No | |

| 1 | 35-44 | 160-199 | 130-139 | ||||

| 2 | 35-39 | < 35 | 200-239 | 140-159 | 120-129 | ||

| 3 | 240-279 | 160+ | 130-139 | Yes | |||

| 4 | 280+ | 140-159 | Yes | ||||

| 5 | 40-44 | 160+ | |||||

| 6 | 45-49 | ||||||

| 7 | |||||||

| 8 | 50-54 | ||||||

| 9 | |||||||

| 10 | 55-59 | ||||||

| 11 | 60-64 | ||||||

| 12 | 65-69 | ||||||

| 13 | |||||||

| 14 | 70-74 | ||||||

| 15 | 75+ | ||||||

| Points | Total | ||||||

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC: total cholesterol; SBP: systolic blood pressure

Table 5.

Overall cardiovascular risk in 10 years for men

| Points | Risk (%) | Points | Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤-3 or less | <1 | 13 | 15.6 |

| -2 | 1.1 | 14 | 18.4 |

| -1 | 1.4 | 15 | 21.6 |

| 0 | 1.6 | 16 | 25.3 |

| 1 | 1.9 | 17 | 29.4 |

| 2 | 2.3 | 18+ | > 30 |

| 3 | 2.8 | ||

| 4 | 3.3 | ||

| 5 | 3.9 | ||

| 6 | 4.7 | ||

| 7 | 5.6 | ||

| 8 | 6.7 | ||

| 9 | 7.9 | ||

| 10 | 9.4 | ||

| 11 | 11.2 | ||

| 12 | 13.2 |

Chart 1.

Aggravating risk factors

| • Family history of early coronary artery disease (male first-degree relative < 55 years-old or female first-degree relative < 65 years-old); | |

| • Criteria of metabolic syndrome according to the International Diabetes Federation; | |

| • Microalbuminuria (30-300 mg/min) or macroalbuminuria (>300 mg/min); | |

| • Left ventricular hypertrophy; | |

| • High-sensitivity C-reactive protein > 3 mg/L; | |

| • Evidence of subclinical atherosclerotic disease: | |

| carotid stenosis/thickening > 1mm | |

| coronary calcium score > 100 or > 75th percentile for age or sex | |

| ankle-brachial test < 0.9 | |

Figura 1.

Algoritmo de estratificação do risco cardiovascular. ERG: estratificação do risco global; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; CV: cardiovascular; RTV: risco por tempo de vida

Table 6.

Classification of recommendation and level of evidence for risk stratification in cardiovascular prevention

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Clinical manifestations of atherosclerotic disease or equivalents (type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus and significant chronic kidney disease), even in primary prevention, have a risk > 20% in 10 years of new cardiovascular events or of the first cardiovascular event | I | A |

| • Patients classified as intermediate-risk with a family history of early cardiovascular disease will be reclassified as high-risk | Ila | B |

| • Men with a calculated risk for any of the events cited >5% and <20% and women with that calculated risk >5% and <10% are considered intermediate-risk | I | A |

| • Men with a calculated risk >20% and women with that calculated risk >10% are considered high-risk | I | A |

| • For individuals at intermediate risk, aggravating factors should be used, and when present (at least one) reclassify the individual as high-risk | Ila | B |

| • Use of risk according to lifespan for low- and intermediate-risk individuals aged >45 years | Ila | B |

Chapter 2 approaches tobacco smoking, the major avoidable risk factor. It is known that 50% of the deaths of smokers, most of which caused by CVD, could be prevented with smoking cessation. In this chapter, the authors discuss preventive measures for tobacco use. Data from the Surveillance of Risk Factors and Protection Against Chronic Diseases via Telephone Inquiry (VIGITEL, in Portuguese), disclosed on April 2012, revealed advances in tobacco use control in Brazil, with 14.8% of smokers older than 18 years. They also approached the primordial prevention of tobacco use, enumerating factors that contribute to smoking initiation and proposing practical strategies for its combat. In addition, the authors discuss techniques to treat the psychological dependence of smokers with general and specific behavioral approaches. Furthermore, this chapter presents instruments to help to assess and understand the patient's profile by using universally accepted scales, such as Prochaska and Di Clemente's and Fagerström's. Finally, the authors approach, in a practical way, pharmacological treatment strategies of tobacco use, such as nicotine replacement with bupropion and varenicline, in addition to second-line drugs (nortriptyline), with their possible associations. Table 7 summarizes the classification of recommendation and level of evidence of those strategies.

Table 7.

Classification of recommendation and level of evidence for the treatment of smoking in cardiovascular prevention

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| • Smoking is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, therefore should be avoided | I | B | |

| • Passive tobacco exposure increases the risk for cardiovascular diseases and should be avoided | I | B | |

| • Pharmacological treatment of smoking | I | A | |

| Nicotine replacement | I | A | |

| Bupropion hydrochloride | I | A | |

| Varenicline tartrate | I | A | |

Chapter 3 discusses the real benefits of primary and secondary CVD prevention, with evident confirmation of diet, supplements and vitamins, aiming at helping the clinician to guide the community in choosing and consuming those products. In addition to supplements, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins B, C, D and E, folates, alpha-linolenic acids and carotenoids were assessed (Tables 8).

Table 8.

Summary of the recommendations for not using vitamin supplements to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) and recommendations for the consumption of products rich in omega-3 fatty acids

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • There is no evidence that supplementation of vitamin A or beta-carotene is beneficial to the primary or secondary prevention of CVD | III | A |

| • Supplementations of vitamin B and folic acid are not effective to the primary or secondary prevention of CVD | III | A |

| • There is no evidence that supplementation of vitamin C is beneficial to CVD prevention, progression or mortality | II | A |

| • Supplementation of vitamin D is not recommended to CVD prevention in individuals with normal serum levels of that vitamin. Likewise, there is no evidence that supplementation in individuals with deficiency of that vitamin will prevent CVD. | III | C |

| • Marine omega-3 supplementation (2-4g/day) or even at higher doses should be recommended for severe hypertriglyceridemia (>500mg/dL), at risk for pancreatitis, refractory to nonpharmacological measures and drug treatment | I | A |

| • At least two fish-based meals per week, as part of a healthy diet, are recommended to reduce the cardiovascular risk. That is particularly recommended for high-risk individuals, such as those with previous myocardial infarction. | I | B |

| • Supplementation of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is not recommendedfor individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease undergoing evidence-based preventive treatment. | III | A |

| • The consumption of polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids of vegetable origin, as part of a healthy diet, should be recommended to reduce the cardiovascular risk, although the real benefit of that recommendation is arguable and the evidence is inconclusive. | IIb | B |

| • Alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) supplementation is not recommended for cardiovascular disease prevention. | III | B |

Chapter 4 approaches obesity, overweight and nutrition transition, as well as the consequences for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of their association with arterial hypertension, dyslipidemias, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritides and cancer. Tables 9 and 10 list the classification of recommendation and levels of evidence for primary and secondary prevention.

Table 9.

Summary of the recommendations for obesity and overweight in cardiovascular disease primary prevention

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Three healthy meals (breakfast, lunch and dinner) and two snacks per day | II | A |

| • Read food labels and choose those with the lowest amounts of trans fats | II | A |

| • Avoid sodas and industrialized juices, cakes, cookies and stuffed cookies, sweet desserts and other sweet treats | I | A |

| • Prefer having water between meals | II | A |

| • Exercise at least 30 minutes per day, everyday | I | A |

| • Individuals with a tendency to obesity or with a familial trend should exercise moderately 45-60 minutes per day; those previously obese, who lost weight, should exercise 60-90 minutes to prevent regaining weight | I | A |

| • Avoid the excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages | I | A |

Table 10.

Summary of the recommendations for obesity and overweight in cardiovascular disease secondary prevention

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Dietary caloric reduction of approximately 500 kcal/day | I | A |

| • Intensification of physical activity, such as walking, biking, swimming, aerobic exercises, 30-45 minutes, 3 to 5 times a week. | I | A |

| • Reduce sedentary activities, such as being seated for long periods watching TV, at computers or playing video games | I | B |

| • Encourage healthy eating for children and adolescents | I | B |

| • Sibutramine for weight loss in patients with cardiovascular disease | III | B |

| • Bariatric surgery for selected patients | I | B |

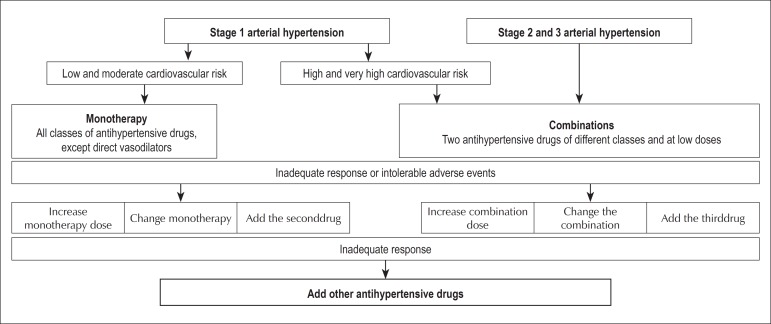

Chapter 5 summarizes the recommendations for systemic arterial hypertension (SAH), emphasizing its importance for the development of several pathologies, such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and chronic kidney disease. Table 11 shows the routine initial assessment of hypertensive patients, and Table 12, its complementary assessment. Therapeutic decision should consider the patient's additional risk. Table 13 shows nonpharmacological measures, which are listed according to their recommendation class and level of evidence. Figure 2 shows the algorithm of pharmacological treatment based on the patients' hypertension stages. Monotherapy can be initiated with any drug class, but SAH control is only achieved in one-third of the cases with that strategy. Chart 2 shows the goals to be met according to patients' characteristics.

Table 11.

Routine initial assessment of the hypertensive patient

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Urinalysis | I | C |

| • Serum potassium | I | C |

| • Serum creatinine | I | B |

| • Estimated glomerular filtration rate | I | B |

| • Fasting glycemia | I | C |

| • Total cholesterol, HDL-C, serum triglycerides | I | C |

| • Serum uric acid | I | C |

| • Conventional electrocardiogram | I | B |

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Table 12.

Complementary assessment of hypertensive patients

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chest X-ray | IIa | C | |

| Echocardiography: | • stage 1 and 2 hypertensives without LVH on ECG | IIa | C |

| • hypertensives with clinical suspicion of HF | I | C | |

| Microalbuminuria: | • hypertensives and diabetic individuals | I | A |

| • hypertensives with metabolic syndrome | I | C | |

| • hypertensives with 2 or + risk factors | I | C | |

| Carotid ultrasound | IIa | B | |

| Treadmill test when coronary artery disease is suspected | IIa | C | |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin | IIa | B | |

| Pulse wave velocity | IIb | C | |

LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; ECG: electrocardiogram; HF: heart failure

Table 13.

Nonpharmacological treatment of hypertensive patients

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | • DASH | I | A |

| • Mediterranean | I | B | |

| • Vegetarian | IIa | B | |

| Sodium: daily intake of 2g | I | A | |

| Alcohol: do not exceed 30g of ethanol per day | I | B | |

| Physical activity: 30 minutes/day/3 times a week (minimum) | I | A | |

| Body weight control: BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 | I | A | |

| Psychosocial stress control | IIa | B | |

| Multiprofessional team | I | B | |

DASH: Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension; BMI: body mass index

Figura 2.

Algoritmo do tratamento da hipertensão arterial segundo a VI Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial

Chart 2.

Blood pressure goals according to individual characteristics

| Category | Consider |

|---|---|

| • Stage 1 and 2 hypertensives at low and moderate CV risk | < 140/90 mm Hg |

| • Hypertensives and borderline behavior with high and very high CV risk, or with 3 or + risk factors, DM, MS or TOL | 130/80 mm Hg |

| • Hypertensives with kidney failure and proteinuria > 1.0 g/L | 130/80 mm Hg |

CV: cardiovacular; DM: diabetes mellitus; MS: metabolic syndrome; TOL: target-organ lesions.

Chapter 6 was aimed at discussing dyslipidemias, in an attempt to, after stratifying the individual risk, establish the therapeutic goals according to the overall risk level (low, intermediate or high). Specific goals are listed for high- and intermediate-risk patients. Patients at low cardiovascular risk should have their goals individualized at their clinician's discretion and according to lipid reference values. Table 14 presents strategies for lifestyle changes. Table 15 lists the pharmacological alternatives based on their recommendation class and level of evidence.

Table 14.

Recommendations for the nonpharmacological treatment of dyslipidemia in cardiovascular prevention

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Control LDL-C | I | A |

| • Meet the recommended LDL-C level (primary goal) | I | A |

| • No goals proposed for HDL-C | I | A |

| • Reduce the intake of saturated fatty acids and trans fatty acids, and consume phytosterols (2-3 g/day) and soluble fibers | I | A |

| • Increase physical activity | I | A |

| • Reduce body weight and increase the ingestion of soy proteins; replace saturated fatty acids with mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids | I | B |

| • Meet the recommended non-HDL-cholesterol level (secondary goal) | II | A |

| • Use proper therapy when triglyceride levels > 500 mg/dL to reduce the risk of pancreatitis, and use individualized therapy when triglyceride levels are between 150 and 499 mg/dL | II | A |

| • No goals proposed for apolipoproteins or lipoprotein(a) | II | A |

Table 15.

Recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of dyslipidemia

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Statins as the first drug option in primary and secondary prevention | I | A |

| • Use fibrates in monotherapy or in association with statins to prevent microvascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes | I | A |

| • Association of ezetimibe or resins with statins when the LDL-C goal is not met | IIa | C |

| • Association of niacin with statins | III | A |

| • Use omega-3 fatty acids for cardiovascular disease prevention | III | A |

Chapter 7 discusses diabetes, emphasizing its high prevalence in the adult population, up to 13.5% in some municipalities, which could represent a current population of 17 million individuals with diabetes. Those numbers are increasing due to factors such as population growth and aging, and increasing urbanization, sedentary lifestyle and obesity. This important chapter discusses essential measures for prevention, such as lifestyle changes (Table 16).

Table 16.

Dietary and physical activity interventions in diabetes mellitus (DM) to prevent cardiovascular disease

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Moderate physical exercise for at least 150 minutes in association with moderate diet and energy restriction to prevent DM in individuals at risk | I | A |

| • Because of the effects of obesity on insulin resistance, weight loss is an important therapeutic goal for individuals at risk for DM | I | A |

| • Reduction in fat to less than 30% of the energy ingestion and reduced energy ingestion for overweight individuals | I | A |

Chapter 8 provides a review on metabolic syndrome. There are several versions of the metabolic syndrome definition, and this guideline adopted the joint position paper of several international organizations on the topic. The authors discuss the epidemiological aspects of its prevalence, approaching different population groups, and aspects related to cardiovascular and metabolic risks, in addition to metabolic syndrome risk factors. Table 17 shows the recommendation class and level of evidence of interventions in metabolic syndrome.

Table 17.

Interventions in metabolic syndrome (MS) to prevent cardiovascular disease

| Indication | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • A 5%-10% reduction in body weight in one year and long-term maintenance of weight lossare recommended | I | B |

| • A diet with low amounts of total, saturated and trans fats, in addition to adequate amounts of fibers, is recommended | I | B |

| • Physical activity for at least 30 minutes/day, preferably 45-60 minutes/day, 5 days a week, is recommended | I | B |

| • Individuals with impaired glucose tolerance on drug therapy can have a more expressive reduction in the incidence of MS or type 2 diabetes mellitus | I | B |

| • Individuals at metabolic risk and with abdominal circumference beyond the recommended limits should undergo a 5%-10% body weight reduction in one year | IIa | B |

| • Ingestion of less than 7% of total calories from saturated fat and of less than 200 mg/day of cholesterol in the diet is recommended | IIa | B |

Chapter 9 discusses the role played by physical activity, physical exercise and sports in CVD prevention. Physically active individuals tend to be healthier and have better quality of life and longer life expectancy. Table 18 lists the recommended physical exercise levels. In addition, the risks of physical activity are approached, as well as the basic principles for exercise prescription and strategies to encourage referral, implementation and adherence.

Table 18.

Recommended exercise levels for health promotion and maintenance

| Exercise characteristics | Health benefits | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| • < 150 min/week of mild to moderate intensity | some | some exercise is certainly better than a sedentary lifestyle |

| • 150-300 min/week of moderate intensity | substantial | longer-duration and/or more intense exercise provides more benefits |

| • > 300 min/week of moderate to high intensity | additional | Current scientific data specifyan upper limit neither for benefits nor for damages to an additional apparently healthy individual |

Chapter 10 discusses psychosocial factors in CVD prevention. Beginning with the definition of the concept, the chapter discusses the psychosocial conditions frequently associated with cardiovascular risk, such as low socioeconomic status, lack of social support, stress at work place and family life, depression, anxiety, hostility and type D personality. In addition, it assesses the recommendation class and level of evidence of approaching the psychosocial factors in primary prevention (Table 19) and for adherence (Table 20) by using cognitive-behavioral methods and indicating the 'ten strategic steps' to improve counseling for behavioral changes. Interventions on depression, anxiety and distress are also proposed as potential tools for adherence to preventive strategies (Chart 3), which can also be improved with the simple measures.

Table 19.

Classification of recommendation and level of evidence in approaching psychosocial factors in primary prevention

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Behavioral changes with cognitive-behavioral strategy (motivational) I | I | A |

| • Integration of education and motivational strategies with a multiprofessional team whenever possible I | I | A |

| • Psychological or psychiatric consultation for more severe cases I | I | C |

| • Assessment of psychosocial risk factors IIa | IIa | B |

| • Pharmacological treatment and psychotherapy for patients with severe depression, anxiety and hostility, aimed at improving ^ the quality of life, despite lack of evidence | IIb | B |

Table 20.

Classification of recommendation and level of evidence of adherence to strategy in cardiovascular prevention, lifestyle and medication

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • Assess and identify the causes of lack of adherence to define the proper orientation | I | A |

| • Use behavioral and motivational strategies for patients with persistent lack of adherence | IIa | A |

Chart 3.

Clinical strategy to improve adherence

| Strategies to improve adherence | |

|---|---|

| • Simplify dosage regimen | • Reduce the number of tablets and doses per day |

| • Reduce costs | |

| • Government subsidies and low-cost programs | |

| • Proper communication | |

| • Avoid using technical terms and overloading the patient with a lot of information | |

| • Behavioral strategies | |

| • Motivation counseling | |

Chapter 11 approaches dyslipidemia, obesity and SAH in childhood and adolescence. Brazilian population studies have shown a 10%-35% prevalence of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents. Table 21 shows the reference values for lipids and lipoproteins in those age groups.

Table 21.

Reference values for lipids and lipoproteins in children and adolescents

| Parameter | Acceptable | Borderline | High (p95) | Low (p5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC | < 170 | 170-199 | > 200 | |

| LDL-C | < 110 | 110-129 | > 130 | |

| n-HDL-C | 123 | 123-143 | > 144 | |

| TG (0-9a) | < 75 | 75-99 | > 100 | |

| TG (10-19a) | < 90 | 90-129 | > 130 | |

| HDL-C | > 45 | 35-45 | < 35 | |

| Apo A1 | > 120 | 110-120 | < 110 | |

| Apo B | < 90 | 90-109 | > 110 |

TC: total cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; n-HDL-C: non-high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; HDL-C: high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol; Apo A1: apolipoprotein A1; Apo B: apolipoprotein B.

Table 22 shows the classification of SAH for children and adolescents. Changes in lifestyle are the initial therapeutic recommendation for primary SAH in children and adolescents. Pharmacological treatment is indicated for individuals with symptomatic hypertension, secondary hypertension, SAH target-organ lesion, types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, and persistent SAH despite the adoption of nonpharmacological measures, a situation in which such measures are an adjunct to the pharmacological treatment.

Table 22.

Classification of arterial blood pressure in children and adolescents

| Class | Percentile of systolic or diastolic blood pressure |

|---|---|

| Normal | < 90 |

| Prehypertension (9) | 90 to <95 or ≥ 120x80 mm Hg |

| Normal-high (10) | |

| Stage 1 SAH | 95 to 99 increased by 5 mm Hg |

| Stage 2 SAH | > 99 increased by 5 mm Hg |

SAH: systemic arterial hypertension

The diagnosis of obesity or overweight in children is clinical, and should be established via history and physical exam, followed by comparison of anthropometric data with population parameters, by using curves of body mass index (BMI) for age. Prevention comprises adequate nutrition during pregnancy, breastfeeding encouragement, identification of familial risk factors, careful child's growth and development follow-up, habit changes, especially the adoption of a healthy diet and global increase in physical activity. It is important to involve the child's entire family, parents, teachers and health care professionals, in addition to count on a multidisciplinary team.

The systematic analysis of studies on the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in the pediatric age group (more particularly adolescents) has shown better results when the actions associate school, family and community, and when the educational actions involve environmental and health policies.

Table 23 shows the recommendations and their levels of evidence to prevent CVD in children and adolescents.

Table 23 .

Classification of recommendation and level of evidence for the presence of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in children and adolescents

| Recommendation | Class | Level of evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity screening | |||

| I | B | ||

| • | In the presence of positive family history, assess all family members, especially the parents | ||

| • | I | C | |

| Identify complications and RF: SBP, gallbladder disease symptoms, diabetes, sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, orthopedic disorders, lipid profile | |||

| • | I | C | |

| • | In children aged > 2 years with BMI > 95th percentile, all measures above plus: Long-term objective: maintain BMI < 85 | I | B |

| I | A | ||

| • | Check urea and creatinine every 2 years | ||

| Nutrition - Milk/other beverages | |||

| Exclusive maternal breastfeeding for the first 6 months | I | B | |

| From the 12th to the 24th month, transition to non-aromatic low-fat milk (2% or skim) | I | B | |

| From 2 to 21 years of age, non-aromatic skim milk should be the major beverage | I | A | |

| Avoid sugar beverages, encourage water ingestion | I | B | |

| Dietary fat | |||

| Fat ingestion by infants should not be restricted without medical indication | I | C | |

| From the 12th to the 24th month, transition to family meals with fat corresponding to 30% of the total caloric ingestion, 8%-10% of which of saturated fat | I | B | |

| From 2 to 21 years of age, fat should correspond to 25%-30% of the total caloric ingestion, 8%-10% of which of saturated fat | I | A | |

| Avoid trans fat | I | B | |

| Cholesterol < 300 mg/dL | I | A | |

| Others | |||

| From 2 to 21 years of age, encourage fiber ingestion, limit sodium ingestion and encourage healthy life habits: family meals, breakfast, limit fast snacks | I | B | |

| Physical activity | |||

| Parents should create an environment that promotes physical activity and limit sedentary activities, and be role models | I | C | |

| Limit sedentary activities, especially TV/video | I | B | |

| Moderate to vigorous physical activity every day | I | A | |

BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; RF: risk factors; SBP: systolic blood pressure

Chapter 12 discusses topics related to legislation and prevention of CVD risk factors. The authors approach specific sanitary laws, discussing their effective role in health promotion and prevention, by creating healthy environments, in addition to emphasizing the importance of surveillance, prevention, health care, rehabilitation and health promotion

Chapter 13 discusses specific aspects of prevention of CVD associated with autoimmune diseases, influenza, chronic kidney disease, obstructive arterial disease, socioeconomic factors, obstructive sleep apnea, erectile dysfunction and periodontitis (Table 24).

Table 24.

Recommendation for approaching special conditions in cardiovascular disease prevention

| Recommendation | class | level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

| • In the context of preventing cardiovascular events, the benefit of using more strict therapeutic targets, especially due to the presence of autoimmune diseases, is uncertain. | IIb | C |

| • Annual influenza vaccination for patients with established coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease, regardless of age | I | B |

| • Annual influenza vaccination for patients at high risk for coronary events, but with no cardiovascular disease, regardless of age. | IIa | C |

| • Patients with chronic kidney disease should be considered at very high risk for cardiovascular risk factors, requiring the assessment of glomerular filtration rate reduction and presence of co-morbidities. | I | C |

| • Patients with obstructive arterial disease should be considered at very high risk, similarly to that of manifest coronary artery disease, for approaching cardiovascular risk factors. | I | C |

| • Socioeconomic indicators should be investigated in clinical assessment and considered when approaching a patient, to improve quality of life and the prognosis of cardiovascular diseases. | IIa | B |

| • All patients with obstructive sleep apnea should be considered as potential candidates to primary prevention, undergo cardiovascular risk stratification and be treated according to estimated risk. | IIa | A |

| • All men with erectile dysfunction should be considered as potential candidates to primary prevention, undergo cardiovascular risk stratification and be treated according to estimated risk. | IIa | B |

| • Patients with periodontitis should be considered for cardiovascular risk stratification and intensive local treatment. | IIa | B |

We provide the medical class with a guideline that gathers, in one single publication, compiled and updated essential prevention topics to be used as a reference in CVD prevention.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research: Simão AF, Précoma DB, Andrade JP, Correa Filho H, Saraiva JFK, Oliveira GMM; Acquisition of data: Simão AF, Précoma DB, Correa Filho H, Oliveira GMM; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Simão AF, Correa Filho H, Saraiva JFK, Oliveira GMM; Writing of the manuscript: Simão AF, Précoma DB, Correa Filho H, Saraiva JFK, Oliveira GMM; Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Simão AF, Précoma DB, Andrade JP, Correa Filho H, Saraiva JFK, Oliveira GMM; Revision of the manuscript: Oliveira GMM.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any thesis or dissertation work.

* To access the complete document with references requested access the link: http://publicacoes.cardiol.br/consenso/2013/Diretriz_Prevencao_Cardiovascular.aspIntroduction