Abstract

Maintaining high transcriptional fidelity is essential for life. Some DNA lesions lead to significant changes in transcriptional fidelity. In this review, we will summarize recent progress towards understanding the molecular basis of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcriptional fidelity and DNA lesion-induced transcriptional mutagenesis. In particular, we will focus on the three key checkpoint steps of controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity: insertion (specific nucleotide selection and incorporation), extension (differentiation of RNA transcript extension of a matched over mismatched 3'-RNA terminus), and proofreading (preferential removal of misincorporated nucleotides from the 3'-RNA end). We will also discuss some novel insights into the molecular basis and chemical perspectives of controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity through structural, computational, and chemical biology approaches.

Keywords: RNA polymerase II, transcription elongation, fidelity control, DNA damage recognition, transcriptional lesion bypass, synthetic nucleotide analogs, unlocked nucleic acid, nonpolar isostere, chemical biology, structural biology, computational biology

1. Introduction

Eukaryotic RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is one of the central enzymes for the first key step of gene expression (1). During transcription, Pol II reads the DNA template and synthesizes a complementary RNA strand. The functional RNA molecules include precursors of protein-coding messenger RNAs as well as non-coding RNAs which may have important and diverse biological roles. Therefore, maintaining a highly accurate transfer of genetic information from DNA to RNA (high transcriptional fidelity) is essential for the process of life (2).

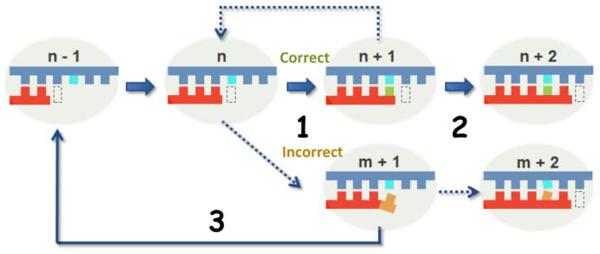

Pol II, as a highly specific “DNA reader” and “RNA writer”, is able to maintain a low error rate during transcription (less than 10−5) (3, 4). The Pol II active site forms a network of interactions that specifically recognizes cognate nucleoside triphosphates and excludes non-cognate ones through three fidelity checkpoint steps (3, 5). These three checkpoint steps include insertion (specific nucleotide selection and incorporation), extension (differentiation of RNA transcript extension of a matched over mismatched 3'-RNA terminus), and proofreading (preferential removal of misincorporated nucleotides from the 3'-RNA end) (Figure 1) (3, 5, 6).

Figure 1.

Schematic model showing the three fidelity checkpoint steps of Pol II transcription. The matched nucleotide (in green) is selected over an incorrect substrate (orange) during the incorporation step (step 1) and the RNA transcript can be efficiently elongated from a matched pair (step 2). In addition, proofreading is required to remove misincorporated nucleotides, backtrack, and reactivate the transcription process (step 3). The DNA template and RNA product are shown in blue and red, respectively. The active site of Pol II is shown in a dash box.

RNA Pol II has also been proposed to be a highly selective DNA damage sensor, since it constantly scans the transcribed genome during transcription (7, 8). In fact, a potentially lethal challenge that all cells and organisms must constantly face is the generation of harmful genomic DNA lesions caused by endogenous and environmental agents (9, 10). There can be as many as one million DNA lesions generated in a cell per day (11). Many of these lesions cause significant DNA structural and chemical alterations. The presence of DNA lesions within highly transcribed genomic regions significantly alters Pol II transcription with deleterious consequences (12–15).

Biochemical and genetic studies have shown that the action Pol II takes when encountering DNA damage is lesion specific (7, 13–17). Pol II can either bypass, backtrack, or stall at DNA lesions. Pol II transcriptional bypass may cause misincorporation within the RNA transcript, termed transcriptional mutagenesis (15, 18). Pol II backtracking leads to intrinsic or transcription factor IIS (TFIIS)-mediated RNA transcript cleavage. Pol II stalling initiates a specialized DNA repair pathway, termed transcription-coupled repair (TCR) (13, 15–17). The TCR pathway, first discovered by the Hanawalt Lab, specifically repairs DNA lesions in the transcribed genome (13, 16, 19–23). In this pathway, the Cockayne Syndrome B protein (CSB) is one of the first proteins recruited to the arrested Pol II site and is involved in the early stages of TCR, although the detailed recruiting mechanism remains to be elucidated (22, 24–28). Finally, as the last resort to remove persistently arrested Pol II, the arrested Pol II undergoes ubiquitylation and degradation (7, 14, 29). Defects in genes involved in TCR cause premature aging and several human diseases, such as UV-sensitive syndrome, Cockayne Syndrome, Xeroderma Pigmentosum, Trichothiodystrophy, and Cerebro-Oculo-Facio-Skeletal Syndrome (13, 30–35). Several excellent reviews on transcription-coupled DNA damage processing can be found elsewhere (13–17). In this review, we will focus on discussing some novel insights into the molecular basis and chemical perspectives in controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity and DNA lesion-induced transcriptional mutagenesis through structural, computational and chemical biology approaches.

2. Recent studies on elucidating the molecular basis of transcriptional fidelity

2.1 Understanding the molecular basis of transcriptional fidelity through structural biology approaches

Pol II is an RNA polymerase containing 12 subunits with a total molecular weight of 550 kDa. A combination of genetic, biochemical, and structural studies have shed new light on the Pol II transcriptional mechanism at an atomic level over the last decade (5, 36–56). There are several excellent reviews focusing on Pol II enzymatic catalysis and transcriptional regulation published elsewhere (6, 57–61). Here we will focus on understanding the molecular basis of the three key checkpoint steps in controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity during transcription elongation phase.

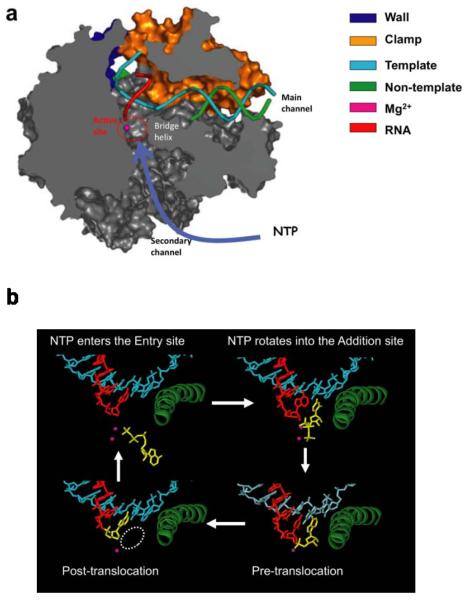

The first atomic three-dimensional crystal structures of Pol II (apo form) and the Pol II transcribing elongation complex were solved in 2001 by the Kornberg group (36, 62). The Pol II elongation complex is in a “pre-translocation” state in which the Pol II active site is still occupied by the newly added nucleotide at the 3'- RNA end. The structure of this Pol II elongation complex reveals two key structural features: first, the DNA template bends about 90 degrees as it crosses over the bridge helix and enters the Pol II active site; second, the RNA forms a short upstream RNA-DNA hybrid with the template DNA strand extending from the Pol II active site. In order to make the active site available for the next nucleotide addition, Pol II must translocate along the DNA template one base pair downstream, referred to as the “post-translocation” state (Figure 2a) (40, 41). The Pol II elongation complex in a post-translocation state was subsequently solved using a synthetic RNA/DNA scaffold to mimic the transcription bubble during transcription (40, 41). In this structure, the active site of the Pol II elongation complex is empty and available for substrate binding, while the Pol II protein has almost an identical conformation with that of the pre-translocation state.

Figure 2.

Structure of Pol II elongation complexes (EC). (a) Interaction networks between the binding NTP and Pol II EC in the active site (PDB ID: 2E2H). The incoming NTP enters the active site through the secondary channel of Pol II, as indicated with the blue arrow. (b) The nucleotide addition cycle. The NTP can first bind to the “entry site”, and rotates into the “addition site” to form the matched base pair with the DNA template nucleotide. After catalysis, the pre-translocation state will translocate one base-step forward to create a new active site and reinitiate the nucleotide addition cycle.

Having the Pol II elongation complex structure in a post-translocation state makes it possible to address how the nucleotide substrate is selected and bound to the Pol II active site using structural biology approaches. A major challenge to overcome during protein crystallization is to separate two kinetically coupled events: nucleotide binding and nucleotide addition. Two approaches were employed to allow nucleotide binding in the Pol II active site while preventing nucleotide addition at the 3'-RNA end (37, 39–41). In one strategy, the 3'-RNA terminus of the Pol II elongation complex at a “post-translocation” state was modified with 3'-deoxyribose. NTPs can bind to the active site but subsequent addition is prevented due to the lack of a 3'-OH on the RNA chain. An alternative strategy is to employ non-hydrolyzable NTP analogues to prevent nucleotide addition. Using these two approaches, a series of structures of Pol II elongation complexes with matched or mismatched substrates binding in the active site were determined.

These structural studies provided several important insights into understanding the molecular basis of the first checkpoint step of Pol II transcriptional fidelity (nucleotide selection and addition). The matched NTP binding to the Pol II active site in which its nucleobase forms a Watson-Crick base pair with the DNA template base is referred to as the “addition site” (Figure 2b, 3a). A key structural feature is that, upon binding of the matched NTP, a conserved motif of Pol II, termed the trigger loop, switches from an inactive open state to an active closed state (Figure 3a–c) (37). It is important to note that the closure of the active site is a common strategy for many other enzymes to greatly facilitate enzymatic efficiency and selectivity (63–65). In addition, Pol II shares a universal two-metal ion catalytic mechanism with many other nucleic acids enzymes (66–70). Two magnesium ions are required to bind the active site for Pol II catalytic activity (Figure 3a–c). All key functional moieties of the substrate, including the nucleobase, sugar and triphosphate, are recognized by the Pol II active site through a substrate recognition network (37). The nucleobase of NTP is base paired with the DNA template and further sandwiched by the 3'-RNA primer and Leu1081(Rpb1) from the Pol II trigger loop to ensure correct positioning in both lateral and vertical directions. Both hydroxyl groups of the sugar moiety are recognized by Pol II residues (hydrogen bonding networks formed by Arg446(Rpb1), Asn479(Rpb1), Gln1078(Rpb1), and Asn1082(Rpb1)). The triphosphate moiety is coordinated by two catalytic magnesium ions and His1085(Rpb1), Lys1020(Rpb2) and Arg766(Rpb2) (Figure 3a). Altogether, these interactions form a network to ensure the NTP is correctly positioned for nucleotide addition and to also ensure correct nucleotide selection. In sharp contrast, the mismatched nucleotide is bound in an inverted conformation in which the nucleobase is facing away from the DNA template, referred to as the “entry site”, and the trigger loop is left in the inactive open conformation. Therefore, the rate of misincorporation is several orders of magnitude slower than the rate of correct substrate incorporation (3, 5). Consistently, several mutations in the trigger loop and the nearby active site that significantly affect Pol II transcription fidelity and catalytic efficiency have been identified (52, 53, 56, 71–78).

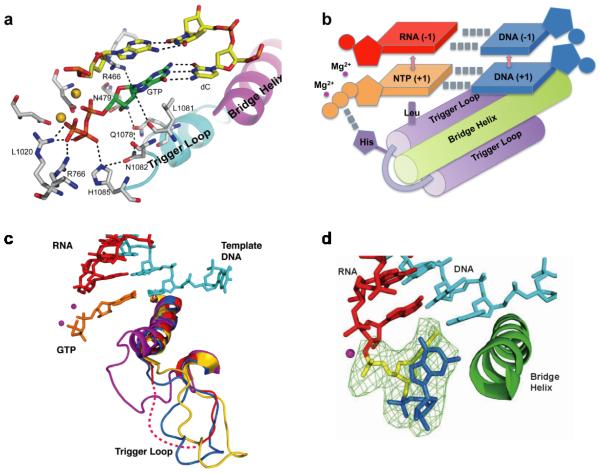

Figure 3.

NTP recognition by the Pol II EC. (a) Interaction networks between the binding NTP and Pol II EC in the active site. The bridge helix (BH, in magenta), trigger loop (TL, in cyan), RNA/DNA hybrid chain (in yellow), NTP (in green), and the Pol II residues interacting with the NTP (in gray) are shown. (b) Schematic model of chemical interactions involved in the recognition interaction networks. The hydrogen bonds within the base pairs and the stacking interactions between the base groups in stabilizing the NTP are indicated as dashed grey lines. The highlighted TL residue Leu1081 serves as an anchor point to position the NTP in the active site. (c) The closing motion of the TL domain can stabilize the NTP in the active site and further facilitates the catalytic reaction. The various forms of the TL captured by X-ray studies are shown in different colors. (d) Substrate misincorporation can lead to Pol II EC backtracking (PDB ID: 3GTG).

In the second fidelity checkpoint step, Pol II transcript extension from a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus is much less efficient than extension from a fully matched end. A series of Pol II structures containing a mismatched RNA terminus provided the structural basis for our understanding of this second checkpoint step. The mismatched 3'-RNA terminus causes a distortion in the RNA/DNA duplex, and thus the nucleotide will either adopt the frayed state or promote Pol II to move in a reverse direction in a backtracking state (Figure 3d) (42, 79, 80). The locations of the 3'-RNA terminus in these Pol II complexes overlap with the canonical substrate binding site and thus inhibit the next round of nucleotide binding and addition.

The slow extension over the mismatched 3'-RNA terminus also provides enough time for Pol II proofreading, which is the third fidelity checkpoint step. Pol II backtracking is an important step for proofreading and ensuring transcriptional fidelity (42, 44, 45, 51, 80, 81). Pol II proofreads nascent transcripts and excises incorrectly added nucleotides via two independent mechanisms: intrinsic cleavage and TFIIS-mediated cleavage (5, 39, 42, 44, 45, 51, 80–92). In intrinsic cleavage, Pol II catalyzes the Mg2+-dependent excision of a 3' dinucleotide, which removes the 3' mismatch. The second form of proofreading involves the recruitment of the transcription factor TFIIS to the backtracked complex, which stimulates fast cleavage of the transcript and the generation of a new 3'-RNA end, after which transcription resumes (38, 39, 42, 80, 93). Several structural studies of backtracked RNA polymerases, generated from either a synthetic scaffold or extension of a tailed template, provide a detailed understanding of these backtracked states and proofreading mechanisms (38, 42, 80). The misincorporated 3'-RNA terminus extrudes from the Pol II active site as a kinked single strand toward the secondary channel (Figure 3d), which is also the channel for NTP diffusion. Dinucleotides or short oligomers containing the misincorporated nucleotide are preferentially removed either by Pol II intrinsic cleavage or by TFIIS-stimulated cleavage, as revealed by structural studies of backtracked Pol II and in complex with TFIIS (38, 42, 80). In the TFIIS-mediated cleavage mechanism, the domain III of TFIIS is inserted into the Pol II active site, pushing the Pol II trigger loop into an open (inactive) conformation. To reactivate Pol II elongation, the domain III of TFIIS must move away from the Pol II active site, allowing the Pol II trigger loop to access the closed conformation and the Pol II active site during nucleotide addition cycles (73). It is important to note that Pol II can also backtrack when it encounters a DNA lesion on the template (5, 39, 42, 44, 45, 51, 81–92, 94). In this scenario, multiple rounds of backtracking, cleavage, and reactivation can happen. This may provide a mechanism for correcting DNA lesion-induced transcriptional mutagenesis, increasing overall transcriptional bypass, and pausing long enough to recruit general DNA repair machinery.

2.2 Understanding the Pol II transcriptional dynamics through computational biology approaches

While X-ray structures of Pol II elongation complexes have greatly advanced our understanding of Pol II transcription at an atomic level (1, 36, 42, 62, 73, 95), these crystals only provide static information on Pol II elongation complexes under the particular experimental conditions used, and the dynamics of these biological functions remained to be elucidated (96, 97). How are the substrate (NTP) and pyrophosphate (PPi) diffused in and out of the secondary channel? How is the substrate correctly positioned with the help of the trigger loop closure? How does Pol II move in both forward and reverse directions? Equipped with great advances in computational power and algorithms and the development of accurate force field, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations provide us with a powerful complementary approach to gain novel understandings of the Pol II transcription process (54, 98–102). Here we will review some of these computational studies, mainly focusing on NTP loading and recognition, subsequent PPi release, and trigger loop motions.

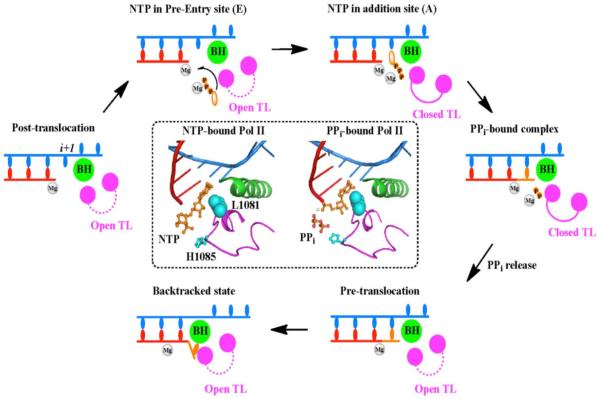

Batada et al studied the diffusion of NTP through the secondary channel using a computational biology approach (102). Interestingly, their results indicate that the presence of the “entry site” greatly increases the occupancy of NTP in the pore region and promotes its transfer to the “addition site”, suggesting a critical role for the “entry site” in recruiting NTP to the active site (Figure 4). Once NTP binds to the active site, it is further recognized by the closed trigger loop by several specific interactions between the NTP and trigger loop residues (73). To investigate the functional roles of trigger loop residues Leu1081(Rpb1) and His1085(Rpb1) in positioning and stabilizing the NTP, Huang et al performed a total of 500-ns all-atom MD simulations for the Pol II elongation complex (54). The MD simulations for the wild-type (WT) and mutant forms of the Pol II elongation complex indicate that the protonated His1085 is the most favorable form when interacting with the β-phosphate atom of NTP. In addition, both H1085F and H1085Y mutants can significantly interrupt the interaction network between the NTP and trigger loop domain. These results explained the experimental observations that H1085Y can induce defects in cell growth and H1085F is lethal to the cells (78). On the other hand, Leu1081 was found to be important for stabilizing the nucleotide base in the correct position and preventing it from deviating laterally or vertically. This computational study greatly enhanced our understanding of the role of His1085 and nearby residues in positioning and stabilizing NTP. After nucleotide addition, the release of PPi from the secondary channel is required before the Pol II elongation complex can advance to the post-translocation state and begin a new nucleotide addition cycle. The kinetics of PPi release and the functional interplay between PPi and Pol II residues were investigated using MD simulations from our group and the Huang group (98). We found that the trigger loop tip domain becomes more flexible following the formation of the phosphodiester bond compared to the NTP-bound Pol II complex (Figure 4). Interestingly, the PPi release along the secondary channel follows a hopping mode in which several hopping sites were observed. In each hopping site, several positively charged residues play critical roles in stabilizing the (Mg-PPi)2− group and keeping it metastable. In addition, PPi release was also tightly coupled with the trigger loop tip motion, but due to the fast dynamics of PPi release, only a partially open state of the trigger loop domain was observed (Figure 4). Therefore, PPi release cannot be directly coupled with translocation, which is believed to occur in longer timescales (tens of microseconds or even longer). This study not only revealed the detailed molecular mechanism of PPi release in Pol II but also captured the kinetic information of PPi release that remains inaccessible by experimental methods. In current collaboration with the Huang group, we are studying the detailed dynamics of Pol II forward translocation after NTP addition and the backtracking process at an atomic level.

Figure 4.

A complete nucleotide addition cycle during the transcriptional elongation process, which primarily consists of the following steps: (1) The NTP (in orange) binds to the post-translocation state of the Pol II EC, accompanied by the TL closing motion. (2) The catalytic reaction takes place and one pyrophosphate ion (PPi) is formed. (3) PPi is released from the active site, followed by the TL opening motion. (4) The pretranslocation state of Pol II EC translocates to the post-translocation state to reinitiate another nucleotide addition cycle. (5) When misincorporation occurs, the Pol II EC can move in reverse direction to form a backtracked state. The NTP- and modeled PPi-bound Pol II EC complexes are shown in the inset where the TL residues Leu1081 and His1085 are highlighted in cyan.

2.3 Understanding chemical interactions and intrinsic structural features in controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity by synthetic nucleic acid analogues

Structural studies have revealed a network of interactions between the Pol II residues, the NTP substrate, and the RNA/DNA hybrid that ensures high transcriptional fidelity. This recognition network is composed of multiple types of chemical interactions including base stacking, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and salt bridge interactions (54, 73). The individual contributions of each of these interactions to the transcription process were not well understood. Dissecting these contributions is very important for fully understanding the molecular mechanisms by which Pol II reads the DNA template and maintains high transcriptional fidelity. Moreover, this knowledge can also provide us with a framework for systematically understanding how DNA modifications and damage affects transcriptional fidelity, as DNA lesions often cause changes in the chemical functional groups and structural features (shape, size, and linkage) of nucleic acids.

Isolating and dissecting the contribution of an individual chemical interaction from others is difficult by conventional biological approaches. Synthetic nucleic acid chemistry has provided us with powerful tools to advance our understanding of the functional interplay between nucleic acids and nucleic acid enzymes, which cannot be achieved by conventional biological methods (such as genetics, biochemistry, or structural biology). These valuable chemical tools can be used to understand how individual chemical interactions and intrinsic structural features of nucleic acids are specifically recognized by Pol II during transcription.

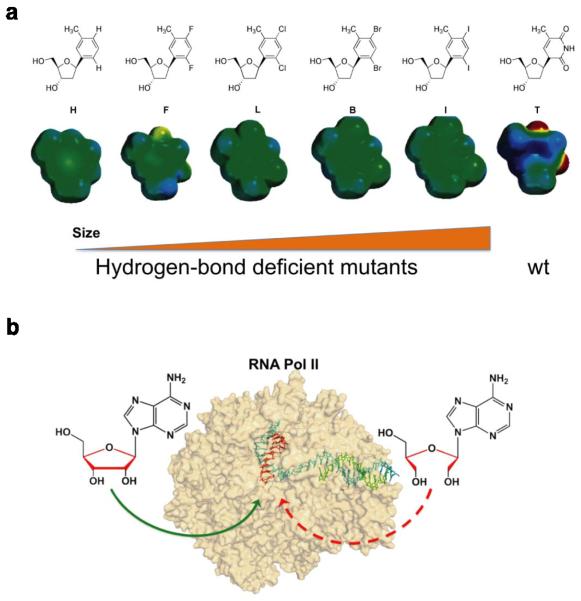

Wang, Kool, and coworkers used a series of “hydrogen bond deficient” nucleoside analogues to dissect the roles of hydrogen bond interactions governing Pol II transcriptional fidelity (3). In this case, a single nucleotide (T) in the DNA template was substituted with nonpolar thymidine isosteres that closely mimic the shape of thymine but lack the capability of hydrogen bonding formation (Figure 5a). The five analogues (H, F, L, B, I) varies by sub-Ångstrom increments in size (Figure 5a)(103, 104). The overall change in size across this series is only about 1.0 Å. F is nearly identical in size and shape to T, while H is smaller and L, B, and I are increasingly larger. In this approach, the effects of the presence and absence of strong hydrogen bonds at the individual fidelity checkpoint steps were systematically examined (3). The size effect was also evaluated by comparing the five analogues.

Figure 5.

Chemical biology tools to dissect the contributions of hydrogen bonding and the sugar backbone to transcriptional fidelity. (a) Chemical structures of several thymidine (T) analogues (H, F, L, B, I) with sub-angstrom increments in size and varying abilities to form hydrogen bonds, compared to wild-type. (b) The unlocked nucleoside was designed to evaluate the roles of the sugar backbone in transcriptional fidelity.

The analogues were used to evaluate each of the three checkpoint steps that contribute to Pol II transcriptional fidelity (3). To test the role of hydrogen bonding in the first fidelity checkpoint step, the substrate specificities were systematically measured for correct (ATP) or incorrect substrate (UTP) incorporation opposite to “wild type” (T) or “hydrogen bond deficient” templates (H, F, L, B, I). Strikingly, Pol II essentially showed no discrimination between ATP (correct) and UTP (incorrect) for “hydrogen bond deficient” templates (F, L, B, and I)(~1.0 selectivity for ATP over UTP), while there was a ~105 fold selectivity of ATP over UTP for T template. This result revealed a significant role of Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding (at the +1 position) in Pol II substrate recognition. Kinetics studies also demonstrated that the loss of substrate discrimination is mainly attributed to decreased incorporation rates (kpol) rather than lower substrate binding affinities (Kd,app). This indicates that Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding has a stronger effect on correctly positioning the incoming NTP for phosphodiester bond formation. The hydrogen bond contribution to Pol II nucleotide incorporation is in sharp contrast to that of many DNA polymerases, in which a lack of hydrogen bonds has a relatively minor effect on deoxyribose nucleotide incorporation (105–111).

The extension of RNA transcripts beyond the “wild type” (T) or “hydrogen bond deficient” templates (F and I), the second fidelity checkpoint step, was subsequently investigated. Surprisingly, replacing a matched A:T base pair with an A:F or A:I base pair did not drastically affect the next nucleotide incorporation specificity for the extension from a matched 3'-RNA terminus, suggesting that Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding at −1 position is dispensable. This result is in sharp contrast to the significant role of Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding (+1 position) in the first checkpoint step. Therefore, the requirement of hydrogen bonding in Pol II transcription is step specific. Much more surprising results were seen in the extension of a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus. Replacing a U:T mismatched pair with a U:F or U:I pair increased the specificity of the next nucleotide addition by ~250- and ~1000-fold, respectively. This result reveals the significant contribution of wobble pair hydrogen bonding at the −1 position in preventing extension from a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus. Taken together, these “hydrogen bond deficient” substitutions cause a significant decrease in the discrimination of a matched over a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus in the second checkpoint step.

The role of hydrogen bonding in the third checkpoint step of Pol II transcription was evaluated by TFIIS-stimulated transcript cleavage assays. As expected, the transcript cleavage rate of Pol II complex with a U:T mismatch is ~10-fold faster than that of Pol II complex with a matched A:T base pair. Replacing T with H and F analogues produced faster cleavage of both matched (A) and mismatched (U) 3'-RNA residues. However, Pol II complexes containing larger base sizes (L, B, and I) resulted in slower cleavage rates comparable with the A:T base pair. Taken together, these results indicated that both Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding and base stacking at 3'-RNA terminus are important in preventing backtrack and subsequent transcript cleavage. The loss of hydrogen bonding leads to an increase of transcript cleavage rate (as seen with the F template) and this “hydrogen bonding deficient” effect can be rescued by increasing base stacking (L, B, and I templates).

Taken together, this study systematically evaluated the effects of hydrogen bonding on each transcriptional fidelity checkpoint step, as well as the contributions of nucleobase size and stacking during transcription. Loss of hydrogen bonding with the template base results in a lower discrimination between correct and incorrect substrate nucleotides, an increase of mismatch extension, and an increase in cleavage rate from a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus. On the other hand, increased size and base stacking causes a universal decrease in NTP incorporation and cleavage, as well as an increase in transcript extension from a mismatched 3'-RNA terminus. This knowledge may be applied to understanding how small DNA lesions affect transcriptional fidelity through changes of hydrogen bonding pattern or base stacking in future studies.

In addition, previous studies have focused on Pol II recognition of the substrate's peripheral functional groups. Wang, Wengel, and co-workers recently investigated the contribution of the sugar backbone to transcriptional fidelity (112). The sugar backbone is the central structural moiety connecting all of the nucleic acid peripheral functional groups: the nucleobase, 2'- and 3'-OH, and phosphate groups. However, the contribution of this core moiety in maintaining accurate genetic information transfer was unclear.

The contribution of the sugar backbone to Pol II transcription fidelity was measured by directly comparing Pol II transcription of a “wild type” ribonucleotide to that of a “sugar backbone mutant” ribonucleotide analogue. This “mutant” ribonucleotide analogue, termed unlocked nucleoside, contains all of the same peripheral functional groups of the “wild type” ribonucleotide except the bond that connects the C2' and C3' atoms of the ribose ring is missing (Figure 5b) (113). Importantly, the unlocked nucleic acid (UNA) residues are still able to form Watson-Crick base pairing with DNA strands without significant disruption to the RNA/DNA hybrid duplex structure (114).

The sugar backbone was found to be a dominant factor in controlling all three fidelity checkpoint steps of Pol II transcriptional fidelity, indicating that the sugar backbone integrity is a prerequisite for correct nucleotide selection in Pol II transcription (112). Nucleobase discrimination is almost completely abolished following the replacement with the unlocked sugar in every single fidelity checkpoint step. Pol II has an unexpectedly strong discrimination power for interrogating substrate ribose integrity, which is 103–104 stronger than its ability to discriminate against deoxyribonucleotides and ~100-fold stronger than its ability to discriminate against a mismatched base (112). These results provide a novel understanding of the molecular basis of the sugar backbone recognition by Pol II, which has been underappreciated. The important lesson to learn here is that the peripheral functional groups of the nucleotide per se are insufficient for efficient Pol II transcription. Rather, the correct spatial arrangement of the functional groups, which are restrained by the sugar backbone, is key to maintaining high Pol II catalytic activity and fidelity. The active site of Pol II is not fully pre-assembled or rigid, and the binding of the nucleotide substrate with the correct spatial arrangement of its functional groups triggers the full closure of the trigger loop and full assembly of the interactions between the Pol II residues and the substrate that poises it for catalysis (5, 37, 53, 115).

Collectively, these studies using synthetic nucleic acid analogues highlight the importance of chemical interactions and the intrinsic structural features of nucleic acids in controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity. These studies also provide a framework for understanding the effect of disrupted chemical interactions and structural features (by DNA lesions) on Pol II transcriptional fidelity.

3. Recent studies on DNA lesion-induced transcriptional mutagenesis

It has long been recognized that Pol II can bypass certain types of DNA lesions (15, 18, 116–118). Among these lesions, some types of DNA damage frequently cause nucleotide misincorporation into an RNA transcript (error-prone transcription bypass) in a manner similar to translesion synthesis by error-prone DNA polymerases, while other types of DNA lesions have little effect on transcriptional fidelity (error-free transcription bypass) (15, 119, 120). Error-prone transcription bypass, termed transcriptional mutagenesis by Paul Doetsch (18, 121, 122), may be an important pathway for the generation of mutant proteins or malfunctioning non-coding RNAs and therefore plays a role in tumor development (122). Impacts of several types of DNA lesion on Pol II transcription have been well documented and thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (13, 15, 116–118). However, the structural mechanisms that dictate error-prone versus error-free transcription are still not fully understood. Here we summarize some recent progress in this area using a combined structural biology and biochemical approach on the following three categories of DNA lesions: oxidative DNA lesion, 1,2-intrastand bulky DNA lesion, and monofunctional bulky DNA lesion.

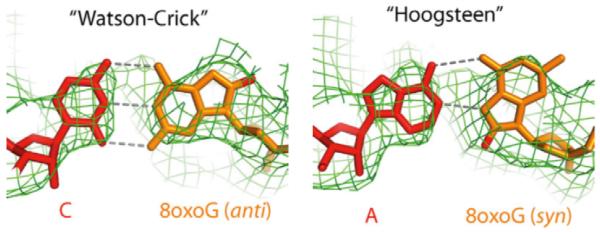

3.1 Structural studies on oxidative DNA lesion-induced transcriptional mutagenesis

8-oxo dG, a major oxidative DNA damage, is well documented as a mutagenic DNA lesion. Mammalian Pol II can bypass this lesion and incorporate either cytosine or adenine opposite 8-oxo dG (123, 124). The 8-oxo dG DNA lesion is speculated to form a Watson-Crick base pair with cytosine and also a Hoogsteen base pair with adenine. Indeed, a recent structural study of Pol II containing 8-oxo G in the DNA template by the Cramer group confirmed that 8-oxo dG adopts a canonical anti conformation paired with cytosine as a Watson Crick base pair and a syn conformation to form Hoogsteen base pair with adenine (Figure 6) (125). It is very interesting to note that Pol II shares the same mechanism of adenine misincorporation at 8-oxoG with high fidelity DNA polymerases (126, 127). At least in the case of 8-oxo dG, the DNA lesion-induced changes in nucleic acid structural features play a very important role in controlling the potential functional outputs from DNA readers (DNA and RNA polymerases).

Figure 6.

8-oxo dG adopts an anti-form when pairing with cytosine and a syn-form when pairing with adenine in the Pol II active site.

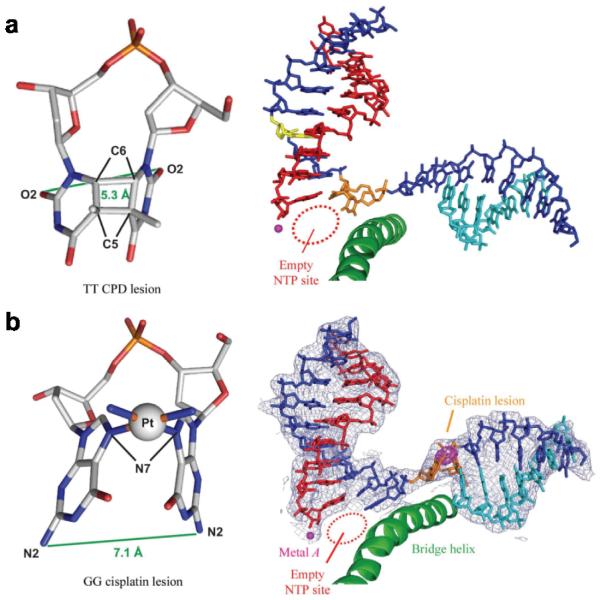

3.2. Structural studies on Pol II blockage and transcriptional mutagenesis at 1,2-intrastand bulky DNA lesions

UV light-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) and cisplatin-induced 1,2-dGpG intrastrand cross-links are two well-studied bifunctional bulky DNA lesions that substantially distort the DNA duplex structure (Figure 7) (128, 129). These two DNA lesions strongly block Pol II transcription and trigger transcription-coupled repair (21, 81, 130–141). The molecular mechanisms of Pol II complexes stalled at the intrastrand cross-links by CPD lesion or cisplatin-DNA lesions are revealed by recent structural studies (Figure 7) (56, 73, 142, 143). Interestingly, the mechanisms of DNA lesion recognition by Pol II are somewhat different. For 1,2-dGpG cisplatin DNA lesion, Pol II stalls simply because the cisplatin-DNA lesion cannot be delivered to the active site (Figure 7b). The cisplatin lesion can be accommodated in a Pol II elongation complex at position +2/+3 of the template strand (Figure 7b), but translocation to position +1/+2 is strongly disfavored (73, 143). Slow AMP misincorporation is observed presumably via a non-template-directed addition (143). In contrast, the CPD lesion can be delivered to the active site. The presence of a CPD DNA lesion at the active site greatly distorts the RNA/DNA hybrid region (Figure 7a), and therefore greatly reduces AMP incorporation opposite to the 3'-thymine. Pol II stalls at a CPD DNA lesion after specific UMP misincorporation opposite to the 5'-thymine. The translocation of the CPD 5'-T:U mismatch base pair from the +1 position to the −1 position is strongly disfavored (Figure 7b) (56, 142). A small portion of translesion bypass of CPD has also been reported (56).

Figure 7.

The structural basis of the bifunctional bulky DNA lesion-containing Pol II ECs. (a) Stick model of the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD, left panel) and the crystal structure of the stalled Pol II EC with one CPD lesion in the DNA template (right panel). (b) Stick model of the cisplatin-induced 1,2-dGpG intra-strand cross-link (left panel) and the crystal structure of the stalled Pol II EC with the 1,2-dGpG cisplatin DNA lesion in the DNA template (right panel).

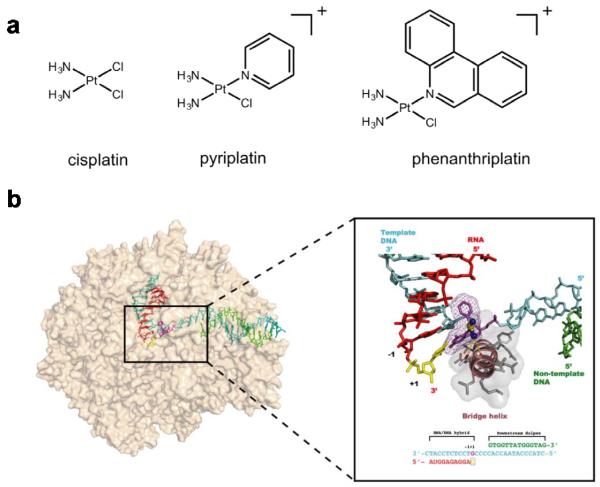

3.3. Structural studies on Pol II blockage and bypass at monofuctional bulky DNA lesions

Monofunctional platinum compounds, including pyriplatin (cis-diamminepyridinechloroplatinum(II)) and phenanthriplatin (cis-diamminephenanthridinechloroplatinum(II)) (Figure 8a), have recently been identified to display a unique spectrum of activity against a panel of cancer cell lines (144, 145). In contrast to cisplatin, these compounds exclusively form monofunctional DNA adducts that do not distort the DNA duplex (145). It is particularly interesting to understand how these bulky platinum groups are accommodated in the Pol II active site and affect Pol II transcriptional fidelity, and whether there is a difference between how Pol II processes these lesions in comparison to a cisplatin-DNA lesion.

Figure 8.

Structural basis of the monofunctional bulky DNA lesion-containing Pol II EC. (a) Chemical structures of cisplatin, pyriplatin and phenanthriplatin. (b) The crystal structure of the Pol II EC stalled at a pyriplatin-DNA monofunctional adduct.

The structures of the Pol II complex stalled at a pyriplatin-DNA monofunctional adduct were recently reported by Wang, Lippard and co-workers (120). Intriguingly, the bulky monofunctional platinum-damaged residues can crossover the bridge helix and be accommodated into the Pol II active site. The correct CMP nucleotide forms a canonical Watson-Crick base pair with platinum-damaged guanosine (Figure 8b). The bulky pyridine ligand extrudes from the major grove but does not disrupt the overall structure of the RNA/DNA hybrid. The platinum DNA adduct interacts with bridge helix residues to stabilize the Pol II complex in the pre-translocation state and introduces a strong steric barrier to inhibit the transition of the next base on the template strand into the Pol II active site. Therefore, the mechanism of transcriptional inhibition by pyriplatin differs significantly from that of cisplatin, in which the cisplatin-DNA lesion cannot be delivered into the Pol II active site (120).

The impact of the monofunctional platinum-DNA lesion on each Pol II transcriptional fidelity checkpoint step was systematically investigated using a DNA scaffold containing a site-specific phenanthriplatin-dG monofunctional lesion (146). The influence of the phenanthriplatin-dG DNA lesion on the template strand is significantly different in each of the three transcriptional fidelity checkpoint steps. Strikingly, the presence of a phenanthriplatin-dG DNA lesion does not affect the first transcriptional fidelity checkpoint step. The specificity for CTP incorporation is essentially the same as for undamaged dG on the template. The high nucleotide discrimination in the first checkpoint step is largely maintained even in the presence of the bulky phenanthriplatin-DNA lesion. In sharp contrast, the presence of a phenanthriplatin-DNA lesion significantly slows down the incorporation of the next nucleotide and greatly diminishes the strong kinetic discrimination of transcript extension from a matched over a mismatched end. The presence of the phenanthriplatin-DNA lesion does not change the cleavage pattern and proofreading activity in the third checkpoint step. As a result, while the majority of the Pol II elongation complexes stall after successful addition of CTP opposite to the phenanthriplatin-dG adduct in an error-free manner, a small portion of Pol II undergoes a slow, error-prone bypass of the phenanthriplatin-dG lesion. Pol II switches from an effective “error-free” to a slow “error prone” mode during lesion bypass, somewhat resembling DNA polymerases switch in a translesion DNA synthesis scenario (147, 148). The difference is that for DNA replication, the high-fidelity replicative DNA polymerases swap with low-fidelity translesion DNA polymerases to continue translesion DNA synthesis, whereas for transcription the same Pol II switches from an effective “error-free” to a slow “error-prone” mode during lesion bypass.

4. Conclusions

In summary, recent advances in structural biology, computational biology and synthetic chemical biology provide us with new perspectives in studying the molecular basis of transcriptional fidelity and functional interplay between DNA lesions and Pol II transcription. We now have detailed molecular mechanisms of Pol II transcriptional fidelity maintenance and have started to gain important insights into what chemical interactions and intrinsic structural features of nucleic acid are important for controlling Pol II transcriptional fidelity.

Based on the previous structrural studies of Pol II processing the three categories of DNA lesions, the exact mechanisms of Pol II bypass and stalling are more likely to be lesion specific. For example, Pol II processing at a monofunctional platnium-DNA lesion is distinct from that of a bifunctional platnium-DNA lesion or 8-oxo dG lesion. Even the mechanisms of Pol II processing of 1,2-instrastrand cisplatin DNA lesion and 1,2-instrastrand CPD lesion are also somewhat different. Yet, we can still learn some general themes from these limited case studies. For the DNA lesions that cannot be well accommodated in the active site, nucleotide incorporation is reduced by several orders of magnitude and Pol II preferentially incorporates AMP through a non-template directed mode. In sharp contrast, a monofunctional platinum-DNA lesion can enter the Pol II active site and support efficient incorporation of CMP opposite to the monofunctional platnium-DNA lesion at a rate that is several orders of magnitude higher than that of AMP incorporation. In the case of 8-oxo G, the oxidative lesion alters the energy landscape of syn and anti conformation of the template base. As a result, the misincorporation of AMP is significantly increased compared to the undamaged template.

Decades of excellent work from many labs in the field pioneered by Hanawalt, Doeutsch, Geacintov, Broyde, Tornaletti, Scicchitano, and many others have set the current frontiers of our understanding of transcriptional processing of many different types of DNA lesions (123, 124, 130–133, 135, 136, 140, 149–163). Intriguingly, recent research efforts have revealed that natural unconventional DNA structures and epigenetic DNA modifications also exert effects on transcription dynamics (164–170). More detailed structural information and systematic comparisons of different DNA lesions in complex with Pol II transcription machinery and other polymerases would provide a comprehensive biochemical basis and structural framework for understanding the functional interplay between DNA lesions and the transcriptional machinery. There is no doubt that we will gain a much deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of DNA-lesion recognition and processing by Pol II transcription machinery through multidisciplinary approaches in the next decade. This knowledge may also provide the basis for designing more potent chemotherapeutic drugs in the future.

Acknowledgements

D.W. acknowledges the NIH (GM102362), Kimmel Scholars award from the Sidney Kimmel Foundation for Cancer Research, and start-up funds from Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, UCSD. E.T.K. acknowledges the NIH (GM072705 and GM068122) for support. S.W.P. acknowledges the UCSD Graduate Training Program in Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology training grant (T32 GM007752).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kornberg RD. The molecular basis of eucaryotic transcription. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(12):1989–1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby R, Gallant J. The role of RNA polymerase in transcriptional fidelity. Mol Microbiol. 1991 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellinger MW, Ulrich S, Chong J, Kool ET, Wang D. Dissecting chemical interactions governing RNA polymerase II transcriptional fidelity. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(19):8231–8240. doi: 10.1021/ja302077d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kireeva M, et al. Millisecond phase kinetic analysis of elongation catalyzed by human, yeast, and Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Methods. 2009;48(4):333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuzenkova Y, et al. Stepwise mechanism for transcription fidelity. BMC Biol. 2010;8:54. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang S, Wang D. Understanding the Molecular Basis of RNA Polymerase II Transcription. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 2013;53(6–7):442–449. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsey-Boltz LA, Sancar A. RNA polymerase: the most specific damage recognition protein in cellular responses to DNA damage? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(33):13213–13214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706316104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ljungman M, Lane DP. Transcription - guarding the genome by sensing DNA damage. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):727–737. doi: 10.1038/nrc1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoeijmakers JH. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(15):1475–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Repair of endogenous DNA damage. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:127–133. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laine JP, Egly JM. When transcription and repair meet: a complex system. Trends Genet. 2006;22(8):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanawalt PC, Spivak G. Transcription-coupled DNA repair: two decades of progress and surprises. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(12):958–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svejstrup JQ. Contending with transcriptional arrest during RNAPII transcript elongation. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32(4):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxowsky TT, Doetsch PW. RNA polymerase encounters with DNA damage: transcription-coupled repair or transcriptional mutagenesis? Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):474–488. doi: 10.1021/cr040466q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagerwerf S, Vrouwe MG, Overmeer RM, Fousteri MI, Mullenders LH. DNA damage response and transcription. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10(7):743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tornaletti S, Hanawalt PC. Effect of DNA lesions on transcription elongation. Biochimie. 1999;81(1–2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doetsch PW. Translesion synthesis by RNA polymerases: occurrence and biological implications for transcriptional mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 2002;510(1–2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohr VA, Smith CA, Okumoto DS, Hanawalt PC. DNA repair in an active gene: removal of pyrimidine dimers from the DHFR gene of CHO cells is much more efficient than in the genome overall. Cell. 1985;40(2):359–369. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellon I, Bohr VA, Smith CA, Hanawalt PC. Preferential DNA repair of an active gene in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(23):8878–8882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mellon I, Spivak G, Hanawalt PC. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell. 1987;51(2):241–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarker AH, et al. Recognition of RNA polymerase II and transcription bubbles by XPG, CSB, and TFIIH: insights for transcription-coupled repair and Cockayne Syndrome. Mol Cell. 2005;20(2):187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fousteri M, Mullenders LH. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells: molecular mechanisms and biological effects. Cell Res. 2008;18(1):73–84. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Troelstra C, et al. ERCC6, a member of a subfamily of putative helicases, is involved in Cockayne's syndrome and preferential repair of active genes. Cell. 1992;71(6):939–953. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troelstra C, Hesen W, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. Structure and expression of the excision repair gene ERCC6, involved in the human disorder Cockayne's syndrome group B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(3):419–426. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.3.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Boom V, et al. DNA damage stabilizes interaction of CSB with the transcription elongation machinery. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(1):27–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Gool AJ, et al. The Cockayne syndrome B protein, involved in transcription-coupled DNA repair, resides in an RNA polymerase II-containing complex. EMBO J. 1997;16(19):5955–5965. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malik S, et al. Rad26p, a transcription-coupled repair factor, is recruited to the site of DNA lesion in an elongating RNA polymerase II-dependent manner in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(5):1461–1477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson MD, Harreman M, Svejstrup JQ. Ubiquitylation and degradation of elongating RNA polymerase II: the last resort. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanawalt PC. Emerging links between premature ageing and defective DNA repair. Mech Ageing Dev. 2008;129(7–8):503–505. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaakkola E, et al. ERCC6 founder mutation identified in Finnish patients with COFS syndrome. Clin Genet. 2010;78(6):541–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laugel V, et al. Mutation update for the CSB/ERCC6 and CSA/ERCC8 genes involved in Cockayne syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(2):113–126. doi: 10.1002/humu.21154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, et al. Mutations in UVSSA cause UV-sensitive syndrome and destabilize ERCC6 in transcription-coupled DNA repair. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):593–597. doi: 10.1038/ng.2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakazawa Y, et al. Mutations in UVSSA cause UV-sensitive syndrome and impair RNA polymerase IIo processing in transcription-coupled nucleotide-excision repair. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):586–592. doi: 10.1038/ng.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwertman P, et al. UV-sensitive syndrome protein UVSSA recruits USP7 to regulate transcription-coupled repair. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):598–602. doi: 10.1038/ng.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnatt AL, Cramer P, Fu J, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II elongation complex at 3.3 A resolution. Science. 2001;292(5523):1876–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, et al. Liver X receptor agonist TO-901317 upregulates SCD1 expression in renal proximal straight tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(5):F1065–1073. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00131.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kettenberger H, Armache K-J, Cramer P. Architecture of the RNA polymerase II-TFIIS complex and implications for mRNA cleavage. Cell. 2003;114(3):347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kettenberger H, Armache K-J, Cramer P. Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS. Mol Cell. 2004;16(6):955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: separation of RNA from DNA by RNA polymerase II. Science. 2004;303(5660):1014–1016. doi: 10.1126/science.1090839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: nucleotide selection by rotation in the RNA polymerase II active center. Cell. 2004;119(4):481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D, et al. Structural basis of transcription: backtracked RNA polymerase II at 3.4 angstrom resolution. Science. 2009;324(5931):1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1168729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erie DA, Yager TD, von Hippel PH. The single-nucleotide addition cycle in transcription: a biophysical and biochemical perspective. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1992;21:379–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.21.060192.002115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeon C, Agarwal K. Fidelity of RNA polymerase II transcription controlled by elongation factor TFIIS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(24):13677–13682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas MJ, Platas AA, Hawley DK. Transcriptional fidelity and proofreading by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1998;93(4):627–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reines D, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Mechanism and regulation of transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11(3):342–346. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80047-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brégeon D, Doddridge ZA, You HJ, Weiss B, Doetsch PW. Transcriptional mutagenesis induced by uracil and 8-oxoguanine in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2003;12(4):959–970. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kashkina E, et al. Elongation complexes of Thermus thermophilus RNA polymerase that possess distinct translocation conformations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(14):4036–4045. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nesser NK, Peterson DO, Hawley DK. RNA polymerase II subunit Rpb9 is important for transcriptional fidelity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(9):3268–3273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511330103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trinh V, Langelier M-F, Archambault J, Coulombe B. Structural perspective on mutations affecting the function of multisubunit RNA polymerases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70(1):12–36. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.12-36.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koyama H, Ito T, Nakanishi T, Sekimizu K. Stimulation of RNA polymerase II transcript cleavage activity contributes to maintain transcriptional fidelity in yeast. Genes Cells. 2007;12(5):547–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kireeva ML, et al. Transient reversal of RNA polymerase II active site closing controls fidelity of transcription elongation. Mol Cell. 2008;30(5):557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaplan CD, Larsson K-M, Kornberg RD. The RNA polymerase II trigger loop functions in substrate selection and is directly targeted by alpha-amanitin. Mol Cell. 2008;30(5):547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang X, et al. RNA polymerase II trigger loop residues stabilize and position the incoming nucleotide triphosphate in transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(36):15745–15750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009898107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yuzenkova Y, Zenkin N. Central role of the RNA polymerase trigger loop in intrinsic RNA hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(24):10878–10883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914424107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walmacq C, et al. Mechanism of translesion transcription by RNA polymerase II and its role in cellular resistance to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2012;46(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaplan CD. Basic mechanisms of RNA polymerase II activity and alteration of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez-Rucobo FW, Cramer P. Structural basis of transcription elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svetlov V, Nudler E. Basic mechanism of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Svejstrup JQ. RNA polymerase II transcript elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu X, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. RNA polymerase II transcription: structure and mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cramer P, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: RNA polymerase II at 2.8 angstrom resolution. Science. 2001;292(5523):1863–1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1059493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cramer P. Multisubunit RNA polymerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doublie S, Sawaya MR, Ellenberger T. An open and closed case for all polymerases. Structure. 1999;7(2):R31–35. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beard WA, Wilson SH. Structure and mechanism of DNA polymerase Beta. Chem Rev. 2006;106(2):361–382. doi: 10.1021/cr0404904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steitz TA, Steitz JA. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(14):6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmidt BH, Burgin AB, Deweese JE, Osheroff N, Berger JM. A novel and unified two-metal mechanism for DNA cleavage by type II and IA topoisomerases. Nature. 2010;465(7298):641–644. doi: 10.1038/nature08974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.De Vivo M, Dal Peraro M, Klein ML. Phosphodiester cleavage in ribonuclease H occurs via an associative two-metal-aided catalytic mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(33):10955–10962. doi: 10.1021/ja8005786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feng H, Dong L, Cao W. Catalytic mechanism of endonuclease v: a catalytic and regulatory two-metal model. Biochemistry. 2006;45(34):10251–10259. doi: 10.1021/bi060512b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sosunov V, et al. Unified two-metal mechanism of RNA synthesis and degradation by RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 2003;22(9):2234–2244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Braberg H, et al. From structure to systems: high-resolution, quantitative genetic analysis of RNA polymerase II. Cell. 2013;154(4):775–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larson MH, et al. Trigger loop dynamics mediate the balance between the transcriptional fidelity and speed of RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(17):6555–6560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200939109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang D, Bushnell DA, Westover KD, Kaplan CD, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: role of the trigger loop in substrate specificity and catalysis. Cell. 2006;127(5):941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Strathern JN, Jin DJ, Court DL, Kashlev M. Isolation and characterization of transcription fidelity mutants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(7):694–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nedialkov YA, et al. The RNA polymerase bridge helix YFI motif in catalysis, fidelity and translocation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walmacq C, et al. Rpb9 subunit controls transcription fidelity by delaying NTP sequestration in RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(29):19601–19612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tan L, Wiesler S, Trzaska D, Carney HC, Weinzierl ROJ. Bridge helix and trigger loop perturbations generate superactive RNA polymerases. J Biol. 2008;7(10):40. doi: 10.1186/jbiol98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toulokhonov I, Zhang J, Palangat M, Landick R. A central role of the RNA polymerase trigger loop in active-site rearrangement during transcriptional pausing. Mol Cell. 2007;27(3):406–419. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sydow JF, et al. Structural basis of transcription: mismatch-specific fidelity mechanisms and paused RNA polymerase II with frayed RNA. Mol Cell. 2009;34(6):710–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheung AC, Cramer P. Structural basis of RNA polymerase II backtracking, arrest and reactivation. Nature. 2011;471(7337):249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature09785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kalogeraki VS, Tornaletti S, Cooper PK, Hanawalt PC. Comparative TFIIS-mediated transcript cleavage by mammalian RNA polymerase II arrested at a lesion in different transcription systems. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4(10):1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sigurdsson S, Dirac-Svejstrup AB, Svejstrup JQ. Evidence that transcript cleavage is essential for RNA polymerase II transcription and cell viability. Mol Cell. 2010;38(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weilbaecher RG, Awrey DE, Edwards AM, Kane CM. Intrinsic transcript cleavage in yeast RNA polymerase II elongation complexes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(26):24189–24199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koyama H, Ito T, Nakanishi T, Kawamura N, Sekimizu K. Transcription elongation factor S-II maintains transcriptional fidelity and confers oxidative stress resistance. Genes Cells. 2003;8(10):779–788. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Izban MG, Luse DS. SII-facilitated transcript cleavage in RNA polymerase II complexes stalled early after initiation occurs in primarily dinucleotide increments. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(17):12864–12873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rudd MD, Izban MG, Luse DS. The active site of RNA polymerase II participates in transcript cleavage within arrested ternary complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(17):8057–8061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson TL, Chamberlin MJ. Complexes of yeast RNA polymerase II and RNA are substrates for TFIIS-induced RNA cleavage. Cell. 1994;77(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Awrey DE, et al. Transcription elongation through DNA arrest sites. A multistep process involving both RNA polymerase II subunit RPB9 and TFIIS. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(23):14747–14754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Erie DA, Hajiseyedjavadi O, Young MC, von Hippel PH. Multiple RNA polymerase conformations and GreA: control of the fidelity of transcription. Science. 1993;262(5135):867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.8235608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.von Hippel PH. An integrated model of the transcription complex in elongation, termination, and editing. Science. 1998;281(5377):660–665. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Reines D, Chamberlin MJ, Kane CM. Transcription elongation factor SII (TFIIS) enables RNA polymerase II to elongate through a block to transcription in a human gene in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(18):10799–10809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zenkin N, Yuzenkova Y, Severinov K. Transcript-assisted transcriptional proofreading. Science. 2006;313(5786):518–520. doi: 10.1126/science.1127422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Powell W, Bartholomew B, Reines D. Elongation factor SII contacts the 3'-end of RNA in the RNA polymerase II elongation complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(37):22301–22304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Awrey DE, et al. Yeast transcript elongation factor (TFIIS), structure and function. II: RNA polymerase binding, transcript cleavage, and read-through. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(35):22595–22605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheung AC, Sainsbury S, Cramer P. Structural basis of initial RNA polymerase II transcription. EMBO J. 2011;30(23):4755–4763. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brueckner F, et al. Structure-function studies of the RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65(Pt 2):112–120. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908039875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Svetlov V, Nudler E. Macromolecular micromovements: how RNA polymerase translocates. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19(6):701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Da LT, Wang D, Huang X. Dynamics of pyrophosphate ion release and its coupled trigger loop motion from closed to open state in RNA polymerase II. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(4):2399–2406. doi: 10.1021/ja210656k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feig M, Burton ZF. RNA polymerase II flexibility during translocation from normal mode analysis. Proteins. 2010;78(2):434–446. doi: 10.1002/prot.22560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feig M, Burton ZF. RNA polymerase II with open and closed trigger loops: active site dynamics and nucleic acid translocation. Biophys J. 2010;99(8):2577–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kireeva ML, et al. Molecular dynamics and mutational analysis of the catalytic and translocation cycle of RNA polymerase. BMC Biophys. 2012;5(1):11. doi: 10.1186/2046-1682-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Batada NN, Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Levitt M, Kornberg RD. Diffusion of nucleoside triphosphates and role of the entry site to the RNA polymerase II active center. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(50):17361–17364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408168101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim TW, Delaney JC, Essigmann JM, Kool ET. Probing the active site tightness of DNA polymerase in subangstrom increments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(44):15803–15808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505113102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim TW, Kool ET. A series of nonpolar thymidine analogues of increasing size: DNA base pairing and stacking properties. J Org Chem. 2005;70(6):2048–2053. doi: 10.1021/jo048061t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Moran S, Ren RX, Rumney S, Kool ET. Difluorotoluene, a Nonpolar Isostere for Thymine, Codes Specifically and Efficiently for Adenine in DNA Replication. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(8):2056–2057. doi: 10.1021/ja963718g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim TW, Brieba LG, Ellenberger T, Kool ET. Functional evidence for a small and rigid active site in a high fidelity DNA polymerase: probing T7 DNA polymerase with variably sized base pairs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(4):2289–2295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sintim HO, Kool ET. Remarkable sensitivity to DNA base shape in the DNA polymerase active site. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45(12):1974–1979. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Silverman AP, Garforth SJ, Prasad VR, Kool ET. Probing the active site steric flexibility of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: different constraints for DNA- versus RNA-templated synthesis. Biochemistry. 2008;47(16):4800–4807. doi: 10.1021/bi702427y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wolfle WT, et al. Evidence for a Watson-Crick hydrogen bonding requirement in DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase kappa. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(16):7137–7143. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7137-7143.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Washington MT, Wolfle WT, Spratt TE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Yeast DNA polymerase eta makes functional contacts with the DNA minor groove only at the incoming nucleoside triphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(9):5113–5118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0837578100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mizukami S, Kim TW, Helquist SA, Kool ET. Varying DNA base-pair size in subangstrom increments: evidence for a loose, not large, active site in low-fidelity Dpo4 polymerase. Biochemistry. 2006;45(9):2772–2778. doi: 10.1021/bi051961z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu L, Plouffe SW, Chong J, Wengel J, Wang D. A chemical perspective on transcriptional fidelity: dominant contributions of sugar integrity revealed by unlocked nucleic acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52(47):12341–12345. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Langkjaer N, Pasternak A, Wengel J. UNA (unlocked nucleic acid): a flexible RNA mimic that allows engineering of nucleic acid duplex stability. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(15):5420–5425. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Pasternak A, Wengel J. Thermodynamics of RNA duplexes modified with unlocked nucleic acid nucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(19):6697–6706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Malinen AM, et al. Active site opening and closure control translocation of multisubunit RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7442–7451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tornaletti S. Transcription arrest at DNA damage sites. Mutat Res. 2005;577(1–2):131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Scicchitano DA, Olesnicky EC, Dimitri A. Transcription and DNA adducts: what happens when the message gets cut off? DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(12):1537–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Scicchitano DA. Transcription past DNA adducts derived from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Mutat Res. 2005;577(1–2):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Waters LS, et al. Eukaryotic translesion polymerases and their roles and regulation in DNA damage tolerance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73(1):134–154. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00034-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wang D, Zhu G, Huang X, Lippard SJ. X-ray structure and mechanism of RNA polymerase II stalled at an antineoplastic monofunctional platinum-DNA adduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9584–9589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002565107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu J, Zhou W, Doetsch PW. RNA polymerase bypass at sites of dihydrouracil: implications for transcriptional mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(12):6729–6735. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bregeon D, Doetsch PW. Transcriptional mutagenesis: causes and involvement in tumour development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(3):218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrc3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tornaletti S, Maeda LS, Kolodner RD, Hanawalt PC. Effect of 8-oxoguanine on transcription elongation by T7 RNA polymerase and mammalian RNA polymerase II. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3(5):483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kuraoka I, et al. RNA polymerase II bypasses 8-oxoguanine in the presence of transcription elongation factor TFIIS. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6(6):841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Damsma GE, Cramer P. Molecular basis of transcriptional mutagenesis at 8-oxoguanine. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(46):31658–31663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Brieba LG, et al. Structural basis for the dual coding potential of 8-oxoguanosine by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 2004;23(17):3452–3461. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Eoff RL, Irimia A, Angel KC, Egli M, Guengerich FP. Hydrogen bonding of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine with a charged residue in the little finger domain determines miscoding events in Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(27):19831–19843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Park H, et al. Crystal structure of a DNA decamer containing a cis syn thymine dimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(25):15965–15970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242422699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Todd RC, Lippard SJ. Inhibition of transcription by platinum antitumor compounds. Metallomics. 2009;1(4):280–291. doi: 10.1039/b907567d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tornaletti S, Donahue BA, Reines D, Hanawalt PC. Nucleotide sequence context effect of a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer upon RNA polymerase II transcription. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(50):31719–31724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tornaletti S, Reines D, Hanawalt PC. Structural characterization of RNA polymerase II complexes arrested by a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer in the transcribed strand of template DNA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(34):24124–24130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mei Kwei JS, et al. Blockage of RNA polymerase II at a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer and 6–4 photoproduct. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320(4):1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kalogeraki VS, Tornaletti S, Hanawalt PC. Transcription arrest at a lesion in the transcribed DNA strand in vitro is not affected by a nearby lesion in the opposite strand. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(21):19558–19564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Donahue BA, Yin S, Taylor JS, Reines D, Hanawalt PC. Transcript cleavage by RNA polymerase II arrested by a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer in the DNA template. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(18):8502–8506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lee K-B, Wang D, Lippard SJ, Sharp PA. Transcription-coupled and DNA damage-dependent ubiquitination of RNA polymerase II in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(7):4239–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072068399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tornaletti S, Patrick SM, Turchi JJ, Hanawalt PC. Behavior of T7 RNA polymerase and mammalian RNA polymerase II at site-specific cisplatin adducts in the template DNA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):35791–35797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Corda Y, Job C, Anin MF, Leng M, Job D. Spectrum of DNA--platinum adduct recognition by prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Biochemistry. 1993;32(33):8582–8588. doi: 10.1021/bi00084a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mello JA, Lippard SJ, Essigmann JM. DNA adducts of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and its trans isomer inhibit RNA polymerase II differentially in vivo. Biochemistry. 1995;34(45):14783–14791. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cullinane C, Mazur SJ, Essigmann JM, Phillips DR, Bohr VA. Inhibition of RNA polymerase II transcription in human cell extracts by cisplatin DNA damage. Biochemistry. 1999;38(19):6204–6212. doi: 10.1021/bi982685+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jung Y, Lippard SJ. RNA polymerase II blockage by cisplatin-damaged DNA. Stability and polyubiquitylation of stalled polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1361–1370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509688200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wang D, Lippard SJ. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4(4):307–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Brueckner F, Hennecke U, Carell T, Cramer P. CPD damage recognition by transcribing RNA polymerase II. Science. 2007;315(5813):859–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1135400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Damsma GE, Alt A, Brueckner F, Carell T, Cramer P. Mechanism of transcriptional stalling at cisplatin-damaged DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(12):1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lovejoy KS, et al. cis-Diammine(pyridine)chloroplatinum(II), a monofunctional platinum(II) antitumor agent: Uptake, structure, function, and prospects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(26):8902–8907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803441105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Park GY, Wilson JJ, Song Y, Lippard SJ. Phenanthriplatin, a monofunctional DNA-binding platinum anticancer drug candidate with unusual potency and cellular activity profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(30):11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207670109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kellinger MW, Park GY, Chong J, Lippard SJ, Wang D. Effect of a monofunctional phenanthriplatin-DNA adduct on RNA polymerase II transcriptional fidelity and translesion synthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(35):13054–13061. doi: 10.1021/ja405475y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Friedberg EC, Lehmann AR, Fuchs RPP. Trading places: how do DNA polymerases switch during translesion DNA synthesis? Mol Cell. 2005;18(5):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]