Abstract

Background

Compassion has been extolled as a virtue in the physician–patient relationship as a response to patient suffering. However, there are few studies that systematically document the behavioural features of physician compassion and the ways in which physicians communicate compassion to patients.

Objective

To develop a taxonomy of compassionate behaviours and statements expressed by the physician that can be discerned by an outside observer.

Design

Qualitative analysis of audio‐recorded office visits between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer.

Setting and Participants

Oncologists (n = 23) and their patients with advanced cancer (n = 49) were recruited in the greater Rochester, New York, area. The physicians and patients were surveyed and had office visits audio recorded.

Main Outcome Measures

Audio recordings were listened to for qualitative assessment of communication skills.

Results

Our sensitizing framework was oriented around three elements of compassion: recognition of the patient's suffering, emotional resonance and movement towards addressing suffering. Statements of compassion included direct statements, paralinguistic expressions and performative comments. Compassion frequently unfolded over the course of a conversation rather than being a single discrete event. Additionally, non‐verbal linguistic elements (e.g. silence) were frequently employed to communicate emotional resonance.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study is the first to systematically catalogue instances of compassionate communication in physician‐patient dialogues. Further refinement and validation of this preliminary taxonomy can guide future education and training interventions to facilitate compassion in physician–patient interactions.

Keywords: communication, compassion, oncology, patient suffering

Introduction

Renewed interest in promoting compassion in clinical care has accompanied profound changes in health care that threaten the intimacy of the physician–patient relationship.1, 2 Compassion begins with recognition of a patient's suffering, accompanied by an internal response to the suffering (often called emotional resonance) and movement towards addressing suffering through presence, word and action.2, 3, 4, 5 In contrast to some conceptualizations of empathy,4, 6 compassion emphasizes emotional resonance: active imagination of the sufferer's condition, concern for his or her good and sense of sharing his or her distress.3 Compassion motivates the individual not only to understand and ‘feel with’ the patient, but also to act to alleviate suffering.5

Seriously ill patients often provide both direct and indirect cues to their distress. Yet, analyses of audio‐recorded oncologist‐patient communications reveal a preference for technical and biomedical issues to the exclusion of emotional talk,7 and compassion often is absent.8, 9

While there is a growing literature on empathy,8, 9 there are few studies of compassion in health care. Qualitative studies10, 11, 12 have defined and described features of compassion based on interviews and surveys, raising questions about recall bias. None were based on direct observation of clinical encounters; accordingly, we know little about what clinicians actually do when they are being compassionate. A behavioural taxonomy of compassionate behaviours could facilitate and inform education and training interventions. In this study, we identified and described compassion by systematically reviewing audio recordings of office visits between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer.

Methods

We employed a phenomenological approach, beginning with a theoretical model of compassion consisting of three domains: recognition, emotional resonance, and movement towards addressing suffering. Based on a literature review including sources from the social sciences,13, 14 nursing,5, 15 fiction,16, 17 religion,18 bioethics4, 19, 20 and general health professions,21 subdomains were located within each domain of compassion. These subdomains were used as a sensitizing framework upon which further analyses were based. Further enquiry was informed but not restricted by this framework. Subdomains not found within the recorded conversations were deleted and additional ones added when appropriate.

Audio‐recorded data were derived from the observational phase of a larger randomized trial from which oncologists in active practice were recruited.22 Recorded encounters took place between November 2011 and June 2012 at multiple private and academic oncology clinics in the Rochester, New York, metropolitan area (three hospital‐based oncology clinics, two private community‐based oncology clinics, and one cancer centre at a large academic medical centre). All practicing oncologists in the Greater Rochester area currently caring for patients with solid (non‐haematologic) malignancies were contacted through e‐mail, phone calls and personal meetings at their clinical practices between October 2011 and March 2012. Of all the physicians who were eligible and invited to participate, 23 ultimately enrolled and 10 declined. Reasons for declining included lack of interest, lack of time and being uncomfortable with audio recording of encounters. Two physicians did not return phone calls. At the time of analysis, 49 audio recordings were available from 17 of the 23 oncologists.

Oncologists were asked to allow audio recording of one clinical encounter with each of three patients identified as having advanced stage cancer. Patients were eligible if they were age 18 or older with advanced non‐haematologic cancer (generally stage III or IV) and if the oncologist ‘would not be surprised’ if the patient died within twelve months.23 Patients were identified from office schedules by the physician or a practice nurse and, with the physician's permission and patient's assent, were approached by a research assistant who described the study and obtained informed consent. Recordings were transcribed and de‐identified by a transcriptionist not involved in data collection or analysis and blinded to the identity of the patient and the research hypotheses.

Analysis was conducted by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a medical student with a background in literature (RC), a medical student with a background in linguistics (BM), a family/palliative care physician and communication researcher (RE), an oncologist‐researcher (SM) and a nurse‐researcher (JD). We used a coding–editing method as described by Crabtree and Miller.24 First, all 49 transcripts of physician–patient visits available at the time of analysis were read line by line by two team members (RC and BM) for preliminary identification of relevant passages of compassion. A subset of 38 visits (from 17 physicians) was selected for a second reading based on appearance of either potentially compassionate dialogue or apparent lack of compassion in response to a patient comment that would call for a compassionate response. The eleven excluded from further analysis lacked any communication relating to patient suffering. Next, one of the investigators (RC) listened to the audio recordings for paralinguistic and supralinguistic elements. We used standard definitions of these elements: paralinguistic expressions are non‐phonemic speech features including tone of voice, pitch, loudness, tempo and sighing, which can be used to communicate attitudes and meaning. Supralinguistic elements are those that make inferences, derive meaning from context and use nonliteral (e.g. metaphorical) language. Next, the team developed two types of codes: emergent coding categories and a priori coding categories derived from the sensitizing framework. Potentially informative transcripts were brought to group meetings, at which all team members read through selected passages and provided comments. Codes were collapsed, revised and redefined during this phase. A final coding scheme was developed, data were entered into qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti 7.0 (The Qualitative Data Analysis & Research Software, Corvallis, OR, USA) and quotes were extracted for further analysis. Differences were resolved by consensus.

Ethics approval was through the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board.

Results

Forty‐nine patients were audio recorded (from 17 physicians, 1–4 recordings per physician) at the time of this study. Characteristics of the 17 physicians in the sample are presented in Table 1. Patient demographics are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physicians in samplea

| Characteristic | Physician sample (n = 17) |

|---|---|

| Average Age, y (std) | 46.4 (11.4) |

| Years in Practice, y (std) | 15.5 (13.1) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 4 (23.5) |

| Male | 13 (76.4) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 11 (64.7) |

| Asian | 6 (35.3) |

| Number of Patients Analysed | |

| One | 6 (35.3) |

| Two | 5 (29.4) |

| Three | 2 (11.8) |

| Four | 4 (25.5) |

Unless otherwise noted, data are reported as number (percentage) of participant physicians.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in samplea

| Characteristic | Patient sample (n = 38) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean | 63.7 |

| Age, range | 44–79 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 (34.2) |

| Female | 25 (65.8) |

| Race | |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 35 (92.1) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 2 (7.1) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.6) |

| Education | |

| Grades 9 through 11 (some high school) | 2 (7.1) |

| Grade 12 or GED (high school graduate) | 16 (42.1) |

| College 1 to 3 years (some college or technical school including the Associates degree) | 14 (36.8) |

| College 4 years (college graduate with a Bachelors degree) | 2 (7.1) |

| Graduate Degree (Masters or Doctorate‐level degree) | 4 (10.5) |

| Income | |

| $20 000 or less | 5 (13.2) |

| $20 001 to $50 000 | 10 (26.3) |

| $50 001 to $100 000 | 14 (36.8) |

| Over $100 000 | 6 (15.8) |

| Unreported | 3 (7.9) |

| Cancer Stage | |

| Stage III | 5 |

| Stage IV | 33 |

| Primary Cancer Site | |

| Breast | 10 |

| Colon | 4 |

| Pancreas | 4 |

| Lung | 3 |

| Ovary | 3 |

| Gastric | 2 |

| Otherb | 12 |

Unless otherwise noted, data are reported as number (percentage) of participant patients.

Other primary cancers included anal, bladder, carcinoid, oesophageal, gallbladder, kidney, liver, neuroendocrine, oropharynx, small bowel and unknown.

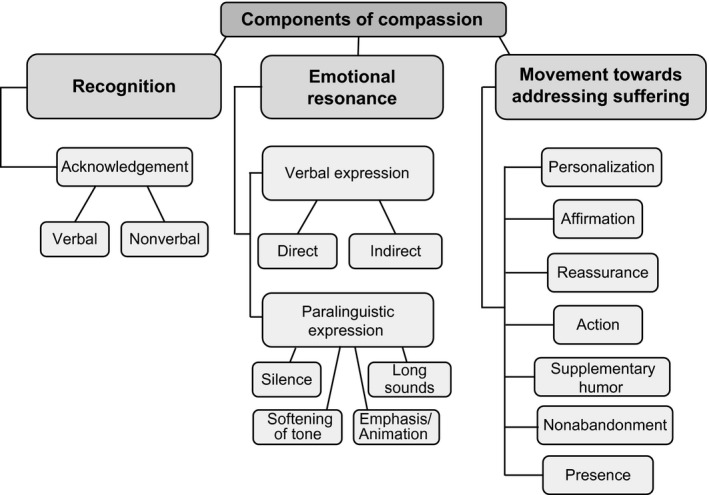

A taxonomy of compassion was developed based on the tripartite definition of compassion stated in the introduction; subcomponents were identified and revised during the course of our qualitative analysis (Fig. 1). While we first conceptualized actionable responses solely as expressions of ‘desire for action’, we found that this did not fully encompass the full range of pro‐healing behaviours physicians can enact and thus subsequently reformulated this final construct as ‘movement towards addressing suffering.’

Figure 1.

Components of compassion.

As our analysis progressed, it became apparent that compassion is not a quality of a single utterance but rather is made up of presence and engagement that suffuses an entire conversation. Thus, we first include examples of each component of compassion, followed by a description of a longer, contextualized interview segment that had evidence of all three components.

Components of compassion

Recognition of suffering

Recognition involves perceiving another person's suffering, leading to awareness but not necessarily understanding of that individual's suffering. Verbal Acknowledgement includes statements that echo, reflect, paraphrase or summarize.25

Doctor: Good to see you. I'm sorry. It sounds like you've had a tough, tough week.

Patient: Yeah, a tough couple of weeks, there, you know.

[Patient 505, Physician 404]

Non‐verbal acknowledgement that could be discerned on an audio recording include a silence, pause or sigh preceding or following a verbal acknowledgement. While non‐verbal acknowledgements might occur in the absence of verbal acknowledgements, without video recordings or access to patients’ reflections on the interactions, these events were difficult to identify and verify. In the following example, it was difficult to ascertain whether the physician's ‘other issues?’ question after a long silence represented avoidance or a respectful response to a patient non‐verbal cue.

D: So we'll do the blood work. I'll get you these two prescriptions and the steroids. Okay. And then we'll see what the blood work shows.

[Pause: ˜3.5s]

P: Sure

D: I know it's discouraging, I know. It's just hard. I know the disease is hard and the treatment is hard.

P: Yeah.

[Pause: ˜3.5s]

D: Other issues?

[Patient 500, Physician 412]

Emotional resonance

Emotional resonance is an internal emotional response of the physician, evoked by recognition of the patient's suffering. The emotion felt by the physician may be distinct from the emotional experience of the patient (e.g. the physician may feel sorrow while the patient feels anguish). Yet, even when there are these differences, emotional resonance can create a sense of sharing and connection, which, in turn, can facilitate further emotional resonance. When vocalized, emotional resonance often has verbal, supralinguistic and paralinguistic elements. The particular uses of language within the following examples suggest strong affective charge, signifying more than simply cognitive understanding.

We considered both direct and indirect verbal expressions of emotional resonance. Direct Verbal Expressions of Emotional Resonance can precede or follow statements of acknowledgement. Note the physician's statement in italics and the shared emotional response (both physician and patient chuckle).

Caregiver: I'll set those up. We have one for 12 : 30 next Tuesday.

P: I should just get a room here. [Chuckles]

D: Oh, I hope you don't really feel like you're spending that much time here.

C: Not now with the one infusion a week.

P: No, it's better. I'm just kidding. [Chuckles]

[Patient 558, Physician 410]

Indirect Verbal Expressions of Emotional Resonance are statements often containing supralinguistic qualities, which demonstrate resonance with what the patient has said. This also includes one‐word paralinguistically inflected remarks such as ‘Yeah’ and ‘Oh.’

D: How are you feeling? How are you doing with all of this?

P: I'm okay. I … they did… [Name] was having me on a Fentanyl patch.

D: Yeah?

P: And I stopped using it.

D: Did it make you sleepy?

P: Well, yeah, it was making it, you know, the … the dose I was on was just enough to take the edge off of the pain but it was… it was making me drowsy, it was making me fuzzy and it was making me constipated. You know, and so … I stopped using it‐

D: Who wants a patch that makes you drowsy, constipated and fuzzy? I'll pass, thank you very much.

P: [Chuckles] So, you know, I'll just… you know, when it hurts I'll take the Oxycodone and…

[Patient 540, Physician 404]

Paralinguistic Expressions of Emotional Resonance often are contained within verbal expressions of emotion. We identified four paralinguistic elements that often contributed to compassionate statements: silence, softening of tone, emphasis/animation and long sounds. Silence, in this context, was defined as a pause preceding or following dialogue containing emotionally charged content. We did note in this example, as in prior examples, that physicians’ questions rarely explored the emotions further in any great detail; rather they tended to re‐direct the interview by broadening or narrowing the focus.

D: Well, just like how we would prioritize your body and put your brain on the back burner I think by the fact that the two brain spots grew we now put – have to put the brain first and the body second.

P: Okay.

D: Yeah.

P: Okay.

[Pause: ˜1.5s]

D: Sorry, I know, it's always hard. It's hard. And I was hopeful as I'm sure you were because this stuff, we could stop feeling it.

P: Right, right.

D: Yeah. How did this last round of chemo go for you?

[Patient 503, Physician 412]

Softening of tone often expresses tenderness and understanding, and emphasizes connection and emotionality.

P: I'm hoping that I can go the end of March.

D: Okay, yup. So that would be like the 20th‐ish.

P: If I can. Yeah. Any time after that.

C: That would be wonderful.

P: That would be wonderful, is right. We've got people doing all kinds of things for us there. We've imposed on so many people now.

[Pause ˜1.5s]

D: I'll bet they don't mind.

P: They don't.

D: They don't.

P: But that's…

D: I know. [Softening of tone]

P: I want to go see if my house is okay.

D: You want to go use your house.

P: Absolutely.

[Patient 516, Physician 420]

Emphasis/Animation consists of accentuation of a particular syllable, word or words when expressing something of potentially therapeutic or emotional value. Here, the physician applies emphasis to an entire statement.

D: Did you lose weight?

P: I haven't lost any in a while.

D: That's huge, Mrs. [Name], that's huge. [Entire sentence spoken with added emphasis and expressivity.]

[Patient 530, Physician 412]

Long sounds occur when syllables or words are prolonged or stretched. Long sounds are indicated by colons following the stretched syllable.

P: Here comes the big question. When the treatments are over which will probably be I'm thinking the next one starting the 11th of March, I think.

D: Yup, 13th actually according to our schedule. That's ‐

P: I want to go to [city/state] so bad.

D: Ohhhhh: [Long sound]

P: For the month of April.

D: I think you should.

P: Thank you.

[Patient 516, Physician 420]

Movement towards addressing suffering

This category encompasses a broad range of statements expressing an inclination, wish, desire, intention, willingness or initiation of movement towards healing actions. These statements may be performative: that is, the uttering of the statement is itself a healing action (e.g. ‘I'm going to help you through this’). We have divided this key third element of compassion into seven subcategories: personalization, affirmation, reassurance, action, supplementary humour, non‐abandonment and presence.

Personalization refers to considering the patient as a unique and whole individual and tailoring treatment to comport with the patient's wishes and identity. The physician may show caring through word choice or modification of a patient's treatment.

D: We have other things we can try if you want. They'll all come with a little bit of constipation. We usually treat that with things to keep your bowels regular. We'll make some adjustments and things today. You can talk with [Name]. If you are feeling tired on chemotherapy, you feel like you need an extra week here or there, that would not be a problem. Of course, Easter is coming up and holidays and sometimes you like to travel, so there would be no problem with taking a break for a week or so here or there. And it sounds like we would carry on with this, as long as this is working to control the cancer I think this is what we would stick with. Does that sound like the right thing for you?

P: Yeah.

D: Yeah. And I don't think I would make any big changes today other than the things we talked about?

[Patient 540, Physician 404]

Affirmation validates something difficult or otherwise emotionally challenging for the patient. This difficult issue may be a decision made or being considered by the patient, or it may be a concern expressed during continued dialogue about an issue. Affirmation by the physician also includes giving the patient permission to feel and express strong emotions. Affirming the patient's experience itself is supportive and addresses some aspects of suffering.

P: I was worried on the way here thinking I don't think I can take this chemo today because I don't think I would be able to survive it. I think I'll end up getting sick. I'll end up, you know, 140 pounds before you know it and losing strength. So, if we can get to the bottom of what's the root of this thing and then maybe we suspend the chemo until such time as we feel comfortable then I can start to get back into the normal rhythm in life.

D: Yeah, I think clearly… yeah, I think you're absolutely right, today – treatment today is the wrong, wrong…

P: Okay, all right.

D: I think we've got to focus all our energy on trying to help you feel better and understand why you are getting sick to your stomach.

[Patient 505, Physician 404]

Reassurance expresses assurance, comfort or reasonable hope to the patient. It can be a way of giving permission, as in the example below. Reassurance too can be spoken as a performative: supportive words may directly bring psychological comfort to the patient.

P: We've been debating going to [city/state] but I'll tell you, the whole idea of the trip and all just is exhausting to me.

D: You know, if you decide to do it, break down and allow somebody to meet you at the gates and use a cart or wheelchair to get you to your next gate and things like that. And having just sent my father‐in‐law off to [city/state] and told him he had to do that he said no, no, I can get there. Just, it's okay. [Emphasis, softening of voice.] Nobody is gonna look at you and say what's that able‐bodied man doing in a cart. Just… it's okay. It's part of setting limits. [Softening of voice]

P: Is your father‐in‐law gonna use the wheelchair?

D: I can't remember what my husband said. I think they arranged but only under protest.

P: Yeah. I know.

[Patient 520, Physician 420]

A statement of Action expresses willingness or intention to take direct steps to relieve the patient of suffering, such as trying to figure out the solution to a problem or suggesting alternative treatment plans. Action can also be observed through clear explanations, advice or encouragement.

D: I know you brought it up about going for a liver transplant.

P: Yes.

D: It's a normal thought to have, why can't we do one of these things and get rid of this cancer. But the truth is studies or… nobody has shown that this… to be beneficial to the patients. It will only add more morbidity. And I would be happy to make an appointment at the [liver transplant centre] and with a stomach surgeon but this is the answer that you will get. You will get that you are not a candidate for these procedures.

P: You think that's what they would tell me?

D: Yes. But you know, I'll be happy to arrange an appointment if you want me to.

C: Your primary care told you the same thing.

D: But you know, you need to get peace of mind. We have discussed this a lot of times over the last 6 months. But you are not at peace because you are not willing to accept the answer. And if it helps you accept it by hearing from the people who do it I'll be happy to help you with it. Do you want me to arrange an appointment with the liver transplant team at [hospital]? You do? Okay. What about the surgeon? Okay. We do. She needs that. I sensed it because she's brought it up so many times.

*Continued dialogue for 30s*

P: I just want a chance to be able to sell it if I can.

D: And I give you that chance. Your blood counts are low but they are at a point where you can still get treatment.

[Patient 526, Physician 428]

Supplementary Humour contains a statement of lightheartedness that does not terminate, deviate from or cut off a conversation of importance, but that does provide breathing room within a serious dialogue and attempts to elevate the patient's spirits. The humour may be embedded within advice also intended to relieve the patient of suffering;

P: Doc, doc, doc. This CAT scan. I'm not gonna be able to drink that stuff. I'll get sick.

C: Yeah, how is he gonna do that?

D: You mean the barium?

P: Yeah. We have to drink like two litres.

C: He'll never get it down.

D: You don't think you'll be able to get it down. What we'll do is we'll give you a lot of things for nausea ahead of time and basically we will explain that you're not gonna be able to drink all of it. And if you can even get a little bit down it allows us to see how the stomach empties. If you just get down one little cup it will tell us what's going on with the stomach.

*Continued dialogue for ˜16s*

D: What I tell people when we're not being tape recorded is to take a cup and then pour the rest down the toilet and tell them that you drank it all. [Laughter]

P: That's what I did when I had my colonoscopy. [Chuckles]

D: Just a creative interpretation of what you are supposed to take.

P: I love it, I love it. Well, I thank you for that. I'm prepared to do what we've got to do to get this right. I want to feel better and I want to get stronger. So, thank you.

[Patient 505, Physician 404]

Non‐abandonment demonstrates that the physician will be available to the patient through the illness regardless of what happens. Non‐abandonment may also be expressed as a performative.

D: Do you want to stop altogether? With the chemo? I feel‐

P: No, no. We're going fine.

D: Okay. You want to keep going, okay.

C: No, we want to keep going.

D: Cause certainly that's always an option. And as long as I feel you can tolerate it, even at a lower dose or a changed schedule I will always do that.

P: Right, right.

D: But if ever you reach a point, you know, and if I feel you've reached the point I'll tell you myself as well, that you wanted to stop with the chemotherapy and just have a quality of life and let this take its course, that's reasonable.

C: No.

D: We'll do our best to get you through.

[Patient 500, Physician 412]

Presence is a category that cannot be reduced to a particular actionable moment or syntactic construction. Rather, presence may be the act of creating space for the patient to express feelings and preferences. Presence also can involve staying within a challenging moment for the patient and working through it together, especially at times when it is easier to be avoidant or dismissive.

Exemplary conversation

In our analyses, it became apparent that a fragmentary view of compassion did not provide a complete picture. Rather, compassion often appeared to unfold over the course of a conversation. Two of the seventeen physicians, whose audio recordings were analyzed, employed a rich set of ways to communicate all three components of compassion. (See Box 1 for physician 420; physician 404 available upon request.)

Box 1A.

This first conversation is a dialogue between an oncologist, female caregiver and male patient who has been experiencing increased pain and nausea over the past week. The dialogue begins with several exploratory, open‐ended questions posed by the physician, during which the patient admits, ‘I can't relax.’ This selection begins with the physician offering advice to the patient on when to take his pain medication.

| 1 | D: And I would like you to take it when you first think you're gonna need it. |

| 2 | P: Yeah. |

| 3 | D: Probably by now you have a sense of the trajectory that the pain is starting to get worse, starting to get worse and if I take it now it's gonna take it this many minutes to work and my pain is gonna be at this level. VERBAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT |

| 4 | P: Yeah. |

| 5 | D: Don't wait. [Underline indicates emphasis.] PARALINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE (EMPHASIS/ANIMATION); ACTION |

| 6 | P: Yeah, you're right. I do wait. You're right. |

| 7 | D: There's no reason to wait. And what I'd like you to do is take what you need and keep a log and then report back because we can increase the long acting. PARALINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE (EMPHASIS/ ANIMATION); ACTION |

| 8 | P: Okay. |

| *Continued dialogue for 35 sec about the treatment plan the physician would like to see* | |

| 9 | D: So, you don't have to hurt. [D drops and softens voice here.] PARALINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE (SOFTENING OF TONE); REASSURANCE |

| 10 | P: Okay. |

| 11 | D: Are you restless for other reasons? |

Box 1B.

*Physician discusses current medications with the patient and caregiver for ~ 4 min 25 sec*

| 1 | D: Or… I mean, cause, you know, the Ativan, your mood has been something that you haven't really wanted to talk too much about but has been an issue. [Pause ~4 sec] |

| 2 | P: Well, like I was… I was really nervous about coming in here today. But I don't know why. |

| 3 | C: He threw up this morning. |

| 4 | P: I can't put my finger on it. I don't know why. I don't know why I'd be nervous about coming in here. |

| 5 | D: Well, what have you been thinking about? What thoughts have been going through your head the last 24 to 48 hours? PRESENCE |

| 6 |

P: I've got a friend coming to [city/state] to hear me perform, a guy I used to play in a band with. And I don't know. |

| 7 | D: So you're worried that you might not be up to his standards? PRESENCE |

| 8 | P: Not worried but just … no, no, no. No. Just extra added activity with the Easter holiday and my gigs and now more people. And more of a draw on… whenever I'm around people I feel like I have to be entertaining. You know? And that really wears me out. |

| 9 | D: So, you… is there something we should – PRESENCE |

| 10 | P: No, but that's what's been on my mind. It kind of makes me nervous. |

| 11 | D: So you've been doing the usual number of gigs or have you been cutting back? |

| 12 | P: Yeah, pretty much. I cut back now in May, I don't have that many. But just because I've not been aggressive calling about them, you know? I'm not really sure how far out. I've booked New Year's Eve but I'm not sure how aggressive I want to get in keeping booking them out there, you know? I'm still taking them. I have to work this afternoon, somebody called. |

| 13 | C: They did? |

| 14 | P: Yeah. |

| 15 | D: So, ‐ |

| 16 | C: Now ‐ |

| 17 | D: Is it the… go ahead |

| 18 | C: Like if he does two gigs in a day he's exhausted, more so than before. |

| 19 | D: So what does that make you think? |

| 20 | P: I like that feeling. I'd rather be exhausted. |

| 21 | D: That's your choice. AFFIRMATION |

| 22 | P: Yeah. |

| 23 | D: And it may bug you because you want to see him be not exhausted. But you have a choice to say only one. AFFIRMATION |

| 24 | P: Yeah. Yeah. Well. |

| 25 | D: I think you need to feel free to set limits [pause ~2.5s] ‘cause you're probably not gonna hurt anybody else's feeling by saying this is all I can do. AFFIRMATION |

| 26 | P: Yeah. I know it. I gotta take‐ |

| 27 | C: He hates doing it, though. |

| 28 | P: I hate doing that. |

| 29 | D: It sounds to me like you're grieving your normal life and it's not something you want to give up yet. VERBAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT |

| 30 | P: A huh. |

| 31 | D: Kind of normal. |

| 32 | P: That makes sense. |

| 33 | C: He did do, what, 17 gigs in 11 days? |

| 34 | D: Oy. INDIRECT VERBAL EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE |

| 35 | C: Over the St. Patrick's Day. |

| 36 | P: I feel like I'm doing something, though, I feel like I'm contributing. [Spoken in a whisper, dropped tone] |

| 37 | D: Well, you know what, [Name]? Do it but don't do it to your own detriment. PARALINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF EMOTIONAL RESONANCE; PERSONALIZATION |

| 38 | P: Yeah. Okay. I got a lot of that stuff going. |

| 39 | D: It's rare of me to tell somebody point blank you've got to stop. However, I will say you have my permission to set limits. AFFIRMATION |

| 40 | P: Okay. |

The conversation captured in Box 1 begins after a thorough exploration of the patient's pain and nausea. We provide this as an example of what the analytic team felt to be a powerful sense of presence, which served as a performative to relieve suffering directly while also offering concrete actions to ameliorate suffering. Moreover, early in the dialogue (Box 1A), the physician expresses all three elements of compassion. After verbally acknowledging the patient's suffering (3), the physician advises the patient not to wait until the pain is unbearable to take pain medication (5, 7). The earnest tone discernible in the audio recording suggests both an internal emotional response to the patient's situation and genuine intention to relieve him of pain. The physician's persistent drive towards action is capped off by a gentle, emotionally‐laden comment oriented towards relief of the patient's suffering (9); in effect, the physician says, ‘I see you're hurting; I want you to see that there's a way to stop the hurting; and I will be there to help you.’

The physician then further explores the issue of restlessness (Box 1A, 11), which eventually segues into an intimate discussion about the patient's nervousness, exhaustion and sense of failure (Box 1B). The physician stays with the patient during this moment of disquiet, implicitly expressing willingness to look into the source of his nervousness (5, 7, 9). As before, her probing presence sets up a comforting, caring atmosphere.

Further, the physician's presence opens the door for the patient to admit uncertainty about how long his life will remain ‘normal’ (12). His physician picks up on his emotional suffering and takes steps towards relieving it. Not only does she validate his preference to feel exhausted (21), but also she affirms the complexity of his thoughts and emotions, by essentially saying, ‘It's okay to do less’ (21, 23). Adding power to the physician's movement towards addressing his suffering is the way in which she expresses her support; rather than ordering him strictly to set limits in order to avoid being run into the ground, she adopts a gentler approach, first qualifying her judgment (‘I think…’) and then encouraging him to let go of established perceptions while also reinforcing to him his own self‐worth (25).

Underneath the surface of the physician's dialogue in this sequence appears a deep recognition of this man as a previously dynamic, involved individual in society and of his agonizing reluctance to move away from his lifelong identity as an entertainer. During the physician's next utterance, this awareness emerges. After slowing down her pace, as though searching for the most appropriate words, she verbalizes a sentiment that has previously only been hinted at: a heart‐wrenching desire to hold onto his past (‘normal’) life (29). This paves the way for the patient to admit, with rich emotional affect, his resistance to the proposed idea, to which the physician responds by similarly changing her tone from earnestness to tenderness as she adjusts her advice towards personalization and compromise (37).

Ultimately, by the end of this sequence, the physician's continued presence and willingness to accompany the patient through the cataloguing of his internal suffering allows a kernel of alternative thought to be planted in his mind. In this way she helps him begin to consider moving in the direction towards acceptance of a very difficult change in life.

Discussion

Our data provide a dynamic view of key observable markers of compassion that we established though a detailed analysis of audio recordings informed by a priori elements of compassion identified in a literature review. We identified components of all three elements of compassion: recognition, emotional resonance and movement towards addressing suffering. Markers of compassion included verbal elements such as performatives, paralinguistic and supralinguistic elements and actionable responses. The goal of our study was not to document the frequency with which compassion was expressed, but we did note a wide range, from total absence to mindful responsiveness. While not the focus of this paper, we confirmed others’ extensive observations that physicians often respond inadequately to patients’ suffering and re‐direct the topic of conversation away from the exploration of emotions.7, 8, 26 One of the contributing factors may be the personal distress that oncologists report when facing unremitting patient suffering and inevitable death; when not adequately prepared psychologically, oncologists experience burnout, which in turn is associated with distancing from, avoidance of, and objectification of patients.27, 28

It is likely that many compassionate actions were missed through the analysis of audio recordings. Patients and physicians may have established an implicit trust and basis for compassion during prior visits. Verbal, paralinguistic and supralinguistic expressions of compassion may be just the tip of an iceberg; compassion may be felt deeply within an individual, but only a fraction is communicated in a way that can be captured by audio recording. This may be particularly true with regard to the emotional resonance component of compassion; although the physician may feel a strong emotional tie towards the suffering patient, his/her emotional resonance may not be expressed independently but rather may be directly linked to statements of action to relieve the suffering of the patient.

To establish that addressing all three components of compassion is possible within a clinical encounter, we presented one conversation in detail in which all components of compassion were apparent, as a model for how physicians might approach compassionate communication in clinical practice. In this conversation, the physician listened fully to her patient as he expressed concerns about ‘threats to his personhood’.29 She expressed her awareness of the patient's suffering in simple language, addressed emotion directly and used reassurance, affirmation and personalized suggestions. We were able to describe how she achieved a healing presence3, 16 through her ability to tolerate and move towards the dissonance of the patient's experience rather than distancing or invalidating the patient's experience in some way.30

The inclusion of paralinguistic elements in our analysis helped to identify many instances of compassion. This is important because most affective communication is conveyed non‐verbally31 through such dimensions as voice qualities, eye contact, facial expression, touch, gestures and space. One study has shown that when presented with 13 different vocal bursts (defined as emotion‐laden non‐word utterances) representing different positive emotions such as compassion, contentment and enthusiasm, individuals were able to reliably identify compassion along with other prosocial emotions including love and gratitude.32 We were able to similarly distinguish differences in voice qualities displayed in the audio recordings and integrate this factor into our taxonomy of compassion. However, only having access to audio recordings and not video recordings or post‐encounter debriefings impaired our ability to account for the other elements of non‐verbal communication which might also contribute to compassion.

Other challenges to describing compassion exist. It has been suggested that there are different phases of suffering, in which the sufferer reacts to the experience with different levels of understanding depending on where they are in the process.14, 16 Consequently, the nature of the compassion exhibited by the physician might also vary depending on the phase of the patient's suffering.14 More broadly, compassion can manifest differently in different contexts, can mean different things to different people and is likely expressed differently depending upon factors such as gender and culture.15, 33

Conclusion

Descriptions of compassion in the health‐care setting have usually been through post‐hoc reports by one or more of the individuals involved in the exchange.10, 11, 12 This study is the first to systematically pinpoint and catalogue instances of compassion in physician–patient dialogues. Further studies will be needed to validate and refine the taxonomy we have presented here. We hope that our detailed description of compassionate communication can inform training interventions to help clinicians communicate compassion more frequently and effectively in their interactions with patients and their families.

Sources of funding

The Advanced Cancer Communication Study, R01CA140419‐01A2, is supported through NIH/NCI funding. This research was also supported through a University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry grant.

Conflicts of interest

There are no known conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jack Coulehan, MD for his guidance on our sensitizing framework upon which we based our analyses.

Corrections added after first online publication on 4 December 2013: In order to protect patient privacy, the names of places and locations in conversations have been omitted.

References

- 1. Dougherty CJ, Purtilo R. Physicians’ duty of compassion. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 1995. Fall; 4: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liben S. Empathy, compassion, and the goals of medicine In: Hutchinson TA. (ed) Whole Person Care: A new Paradigm for the 21st Century, 1st edn New York: Spring Science+Business Media, LLC., 2011: 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blum L. Compassion In: Rorty AO. (ed) Explaining Emotions. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1980: 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gelhaus P. The desired moral attitude of the physician: (II) compassion. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 2012; 15: 397–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schantz ML. Compassion: a concept analysis. Nursing forum, 2007; 42: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hojat M. Empathy in Patient Care: Antecedents, Development, Measurement, and Outcomes, 1st edn New York: Springer, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford S, Fallowfield L, Lewis S. Doctor‐patient interactions in oncology. Social Science and Medicine, 1996; 42: 1511–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2008; 168: 1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pollak KI, Arnold R, Alexander SC et al Do patient attributes predict oncologist empathic responses and patient perceptions of empathy? Supportive Care in Cancer, 2010; 18: 1405–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kret DD. The qualities of a compassionate nurse according to the perceptions of medical‐surgical patients. Medsurg Nursing, 2011; 20: 29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sanghavi DM. What makes for a compassionate patient‐caregiver relationship? Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2006; 32: 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skaff KO, Toumey CP, Rapp D, Fahringer D. Measuring compassion in physician assistants. Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, 2003; 16: 31–36, 39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Batson CD. These things called empathy: eight related but distinct phenomena In: Decety J, Ickes W. (eds) The Social Neuroscience of Empathy, 1st edn Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reich WT. Speaking of suffering: a moral account of compassion. Soundings, 1989. Spring; 72: 83–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dewar B, Pullin S, Tocheris R. Valuing compassion through definition and measurement. Nursing Management (Harrow), 2011; 17: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coulehan J. Compassionate solidarity: suffering, poetry, and medicine. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 2009. Autumn; 52: 585–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coulehan J, Clary P. Healing the healer: poetry in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2005; 8: 382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ryan T. Aquinas on compassion: has he something to offer today? Irish Theological Quarterly, 2010; 75: 157–174. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arnold L, Stern DT. What is medical professionalism? In: Stern DT. (ed) Measuring Medical Professionalism, 1st edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2006: 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th edn New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21. McGaghie WC, Mytko JJ, Brown WN, Cameron JR. Altruism and compassion in the health professions: a search for clarity and precision. Medical Teacher, 2002; 24: 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hoerger M, Epstein RM, Winters PC et al Values and options in cancer care (VOICE): study design and rationale for a patient‐centered communication and decision‐making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers. BMC Cancer, 2013; 13: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S et al Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2010; 13: 837–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research (Research Methods for Primary Care), 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Del Piccolo L, de Haes H, Heaven C et al Development of the Verona coding definitions of emotional sequences to code health providers' responses (VR‐CoDES‐P) to patient cues and concerns. Patient Education and Counseling, 2011; 82: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levinson W, Gorawara‐Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA, 2000; 284: 1021–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shanafelt T, Dyrbye L. Oncologist burnout: causes, consequences, and responses. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2012; 30: 1235–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shayne M, Quill TE. Oncologists responding to grief. Archives of Internal Medicine, 2012; 172: 966–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. New England Journal of Medicine, 1982; 306: 639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makowski SK, Epstein RM. Turning toward dissonance: lessons from art, music, and literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2012; 43: 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor‐patient communication: a review of the literature. Social Science and Medicine, 1995; 40: 903–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simon‐Thomas ER, Keltner DJ, Sauter D, Sinicropi‐Yao L, Abramson A. The voice conveys specific emotions: evidence from vocal burst displays. Emotion, 2009; 9: 838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon‐Thomas E. Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 2010; 136: 351–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]