Abstract

AIM: To investigate moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection following failed first-line treatment.

METHODS: The sample included 312 patients for whom first-line treatment failed between January 2008 and May 2013; 27 patients were excluded, and a total of 285 patients received 7- or 14-d moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for H. pylori infection. First line regimens included 7-d standard triple (n = 172), 10-d bismuth-containing quadruple (n = 28), 14-d concomitant (n = 37), or 14-d sequential (n = 48) therapy. H. pylori status was evaluated using 13C-urea breath testing 4 wk later, after completion of the treatment. The primary outcome was the H. pylori eradication rate analyzed using intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) analyses. The secondary outcome was the occurrence of serious adverse events. Demographic and clinical factors were analyzed using Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s χ2 tests according to first- and second-line regimens. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS: The eradication rate of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy was 68.4% (ITT; 95%CI: 62.8-73.5) and 73.9% (PP; 95%CI: 68.3-78.8). The eradication rate was significantly higher with 14 d compared to 7 d of treatment (77.5% vs 62.5%, P = 0.017). Peptic ulcer patients had a higher eradication rate than the patients without ulcers (82.9% vs 70.6%, P = 0.046). The demographic and clinical characteristics were not significantly different between the groups according to first-line therapies. ITT and PP analyses of the moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy indicated the following eradication rates: 70.9% (95%CI: 63.8-77.2) and 77.2% (95%CI: 70.1-83.1) for standard triple; 67.9% (95%CI: 51.5-84.2) and 67.9% (95%CI: 51.5-84.2) for bismuth-containing quadruple; 60.4% (95%CI: 46.3-73.0) and 70.7% (95%CI: 54.0-80.9) for sequential; and 67.6% (95%CI: 51.5-80.4) and 67.6%(95%CI: 51.5-80.4) for concomitant therapy. There were no statistically significant differences in the efficacy of the first-line regimens (P = 0.492). The most common adverse event was diarrhea. There were no serious adverse events and no significant differences in the frequency of side effects between the first- and second-line regimens (28.7% vs 26.1%, respectively).

CONCLUSION: Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment resulted in low eradication rates. There were no differences in the efficacy between the first-line regimens in South Korea.

Keywords: Fluoroquinolones, Helicobacter pylori, Disease eradication, Drug resistance, Second-line

Core tip: This study aimed to examine Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication rates using moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment. The effectiveness of the failed first-line treatment options was compared. The use of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy resulted in low eradication rates, and there were no differences in the efficacy between the failed first-line regimens. As a result, we recommend tailored therapy for H. pylori and careful antibiotic selection before second-line treatment in South Korea.

INTRODUCTION

Traditional indications for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication are peptic ulcer disease, gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and early gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection[1]. However, current consensus also includes functional dyspepsia, long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), iron deficiency anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and H. pylori infection after subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer[2].

The combination of proton pump inhibitors (PPI), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin is the standard triple therapy, and it has been prescribed as a first-line treatment for H. pylori infection. Despite the increase in the indications for H. pylori treatment, there has been a decrease in the rate of H. pylori eradication due to an increase in resistance to clarithromycin and amoxicillin[3]. Therefore, levofloxacin-based triple, sequential, concomitant, hybrid, high-dose dual, and rifabutin-based triple therapies have also been used for the treatment of H. pylori infection.

Due to the increase in resistance to clarithromycin, not only standard triple therapy but also bismuth-containing quadruple therapy is recommended as first-line treatment in Korean guidelines[4]. In addition, sequential and concomitant therapies are used as first-line regimens in other countries[5]. For this reason, the availability of rescue therapies has increasingly become a concern. In the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus[2], fluoroquinolone-based triple therapy, such as levofloxacin, was used as second-line treatment after the failure of standard triple and bismuth-containing quadruple therapies. The rate of H. pylori eradication using moxifloxacin-based treatment, which is a type of fluoroquinolone, as second-line therapy is reported to be high[6,7]. However, the use of moxifloxacin as second-line treatment has only been reported after the use of standard triple and bismuth-containing therapy as first-line treatments. In addition, rescue regimens have not been well established after failed sequential and concomitant therapy as first-line treatments, and both regimens include metronidazole, which creates challenges in using bismuth-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment. To our knowledge, there have been no reports of the effectiveness of moxifloxacin as second-line treatment following failed first-line treatment in the form of sequential or concomitant therapy.

This study aimed to examine H. pylori eradication rates using moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment and compared the efficacy of failed first-line regimens which included standard triple, bismuth-containing quadruple, sequential, and concomitant therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The sample included 312 patients for whom eradication of H. pylori infection in the gastrointestinal outpatient clinic at the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital was not successful following first-line treatment between January 2008 and May 2013 and who subsequently received moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment. The patients had not previously received H. pylori eradication therapy before the first-line treatment. Patients were excluded if they received H2 receptor antagonists, PPIs, or antibiotics in the previous 4 wk, or they used a NSAIDs or steroid in the 2 wk before the 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT). The exclusion criteria were as follows: previous gastric surgery or endoscopic mucosal dissection for gastric cancer; advanced gastric cancer; a systemic illness, such as liver cirrhosis or chronic renal failure; pregnancy; age < 18 years; and insufficient data. All patients gave written informed consent, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We also received institutional review board approval from Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

Histologic evaluation and rapid urease test

The presence of H. pylori was defined as a positive result on histology or rapid urease test. A biopsy specimen, obtained by endoscopy, was fixed in formalin and used for the determination of H. pylori infection by Giemsa staining. The results of the rapid urease tests (CLO test; Delta West, Bentley, Western, Australia) were interpreted as positive if the color of the gel turned pink or red at room temperature within 24 h after the examination.

H. pylori eradication regimens

Patients received standard triple, bismuth-containing quadruple, sequential, or concomitant therapy as the first-line regimen for eradication of H. pylori. Standard triple therapy included 1 g amoxicillin twice a day (b.i.d), 500 mg clarithromycin b.i.d., and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d. for 7 d. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy was comprised of 300 mg tripotassium dicitrato bismuthate 4 times a day (q.i.d.), 500 mg tetracycline q.i.d., 500 mg metronidazole 3 times a day, and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d. for 10 d. Sequential therapy was given for 2 wk and included 1 g amoxicillin and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d. for the first week, followed by 500 mg clarithromycin, 500 mg metronidazole, and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d for the second week. Concomitant therapy consisted of 1 g amoxicillin, 500 mg clarithromycin, 500 mg metronidazole and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d for 2 wk.

As second-line treatment, moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy included 400 mg moxifloxacin q.d., 1 g amoxicillin b.i.d., and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d. for 7 or 14 d.

The patients who took < 70% of the prescribed medication were considered to have low compliance.

Urea breath test

H. pylori eradication was evaluated using 13C-UBT exactly 4 wk after the completion of treatment. An initial breath sample was obtained after 4 h of fasting, with a second breath sample obtained 20 min later. One hundred milligrams of 13C-urea powder (UBiTkit™; Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in 100 mL of water was administered orally. Collected samples were analyzed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (UBiT-IR300®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Japan) with a cutoff value of 2.5%.

Statistical analysis

The primary and secondary outcomes of this study were the H. pylori eradication rate and treatment-related adverse effects, respectively. H. pylori eradication rates were determined by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) analyses. ITT analysis compared the treatment groups including all the patients as originally allocated. PP analysis compared treatment groups including only those patients who completed the treatment as originally allocated. Eradication rates in both the overall sample and subgroups with failed first-line therapies were analyzed using Student’s t-tests and Pearson’s χ2 tests according to the demographic and clinical factors. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was conducted using SPSS 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study groups

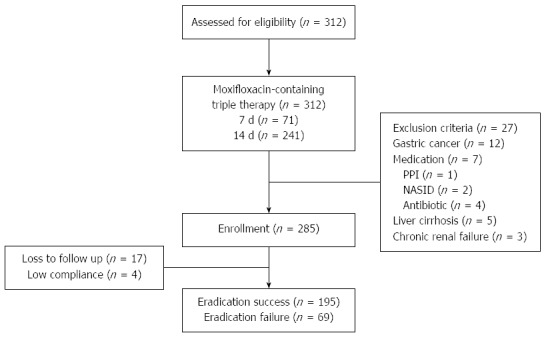

Of the 312 patients, 27 were excluded from the study due to gastric cancer (n = 12); use of medications including antibiotics, NSAIDs, or steroids (n = 7) before the 13C-UBT; liver cirrhosis (n = 5); and chronic renal failure (n = 3). Thus 285 patients underwent eradication treatment. Seventeen were lost to follow-up, and 4 had low treatment compliance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients. PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; NSAID: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients who were administered moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as the second-line regimen are shown in Table 1, and these characteristics divided into subgroups according to the first-line regimens are provided in Table 2. The proportion of patients with peptic ulcer disease (PUD) was significantly higher than patients without PUD in the moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy group (P = 0.046). There were no other significant differences between the groups of first-line therapies.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and Helicobacter pylori eradication rates due to moxifloxacin triple therapy

| Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second line | P value1 | |

| Total eradication rate | 73.9% (195/264) | |

| Clinical factors | ||

| Gender | 0.794 | |

| Male | 74.6% (94/126) | |

| Female | 73.2% (101/138) | |

| Age | 0.965 | |

| < 45 | 74.2% (23/31) | |

| ≥ 45 | 73.8% (172/233) | |

| Smoking | 0.575 | |

| Current smoker | 77.1% (37/48) | |

| Non-smoker | 73.1% (158/216) | |

| Alcohol | 0.356 | |

| Current drinker | 69.4% (43/62) | |

| Non-drinker | 75.2% (152/202) | |

| Comorbidity | ||

| HTN | 69.4% (34/49) | 0.429 |

| DM | 90.5% (19/21) | 0.076 |

| Disease status | 0.046 | |

| Peptic ulcer (DU/GU) | 82.9% (58/70) | |

| Non-ulcer | 70.6% (137/194) |

Pearson's χ2 test. HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; DU: Duodenal ulcer; GU: Gastric ulcer.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics according to first line therapies n (%)

| Standard triple therapy | Bismuth quadruple therapy | Sequential therapy | Concomitant therapy | P value1 | |

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 58.1 ± 11.6 | 58.5 ± 11.4 | 56.1 ± 11.5 | 56.9 ± 11.3 | 0.591 |

| Male/Female (n) | 72/86 | 10/18 | 20/21 | 24/13 | 0.150 |

| Smoking (n) | 28 (17.7) | 4 (13.8) | 8 (19.5) | 8 (21.6) | 0.904 |

| Alcohol (n) | 35 (22.2) | 7 (24.1) | 10 (24.4) | 10 (27) | 0.851 |

| HTN (n) | 34 (21.5) | 5 (17.2) | 6 (14.6) | 4 (10.8) | 0.451 |

| DM (n) | 14 (8.9) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (4.9) | 2 (5.4) | 0.845 |

| Endoscopic finding (n) | - | ||||

| DU/GU | 55 | 1 | 6 | 8 | - |

| CAG | 66 | 18 | 13 | 12 | - |

| IM | 23 | 1 | 5 | 3 | - |

| Erosive gastritis | 30 | 9 | 18 | 15 | - |

| MALT lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - |

Pearson's χ2 test. HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; DU: Duodenal ulcer; GU: Gastric ulcer; CAG: Chronic atrophic gastritis; IM: Intestinal metaplasia; MALT: Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue.

Outcomes of moxifloxacin-containing therapy according to the first-line regimens

The overall eradication rate by moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as the second-line treatment was 68.4% (95%CI: 62.8-73.5) and 73.9% (95%CI: 68.3-78.8) using ITT and PP analyses, respectively. The eradication rates due to moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy according to the failed first-line regimens using ITT analysis were 70.9% (95%CI: 63.8-77.2) in the standard triple therapy group, 67.9% (95%CI: 51.5-84.2) in the bismuth-containing quadruple therapy group, 60.4% (95%CI: 46.3 -73.0) in the sequential therapy group, and 67.6% (95%CI: 51.5-80.4) in the concomitant therapy group. According to PP analyses the eradication rates related to the use of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy for each of the failed first-line regimens were 77.2% (95%CI: 70.1-83.1), 67.9% (95%CI: 51.5-84.2), 70.7% (95%CI: 54.0-80.9), and 67.6% (95%CI: 51.5-80.4) in the standard triple, bismuth-containing quadruple, sequential, and concomitant therapy groups, respectively.

The 14-d moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy resulted in a higher eradication rate compared with the 7-d regimen. The ITT analyses resulted in rates of 58.0% for the 7-d treatment and 71.8% for the 14-d treatment (P = 0.032), while the PP analyses resulted in 62.5% and 77.5%, respectively (P = 0.017). The group treated with moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy following the failure of standard triple therapy had the highest rates of eradication (70.9% and 77.2% by ITT and PP analyses, respectively); however there were no statistically significant differences in the efficacy of the first-line regimens (P = 0.492). The most common adverse event was diarrhea, but there were no serious adverse events and no significant differences in the frequency of side effects between the first- and second-line regimens (28.7% vs 26.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adverse events n (%)

| First-line therapy | Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy | |

| Diarrhea | 21 (7.9) | 25 (9.4) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 14 (5.3) | 23 (8.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 14 (5.3) | 11 (4.2) |

| Taste distortion | 19 (7.2) | 4 (1.5) |

| Dizziness | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (1.1) | 5 (1.9) |

| Total | 76 (28.7) | 61 (23.1) |

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as a second-line treatment for H. pylori infection following failed first-line regimens. The use of moxifloxacin resulted in a low eradication rate, regardless of the type of first-line treatment; however, longer duration of treatment (14 d) was more effective than shorter treatment duration (7 d).

Our results are similar to those reported previously by Yoon et al[8] based on data collected in 2007-2008, where the eradication rates were 68% and 79.9% using ITT and PP analyses, respectively. These findings are comparable to our results of 68.4% (ITT) and 73.9% (PP) eradication based on data from 2008-2013. These rates are considered unacceptably low. However, the increased effectiveness observed with longer moxifloxacin treatment is similar to that previously reported[7].

The eradication rate in patients with PUD was higher than in non-ulcer patients in our study. Although strong evidence is lacking to support expectations of higher eradication rates in PUD, there are several hypotheses that may explain greater success in PUD. H. pylori strains with high virulence factors were more likely to cause PUD and had a higher eradication rate than those of low virulence. PUD results in moderate to severe inflammation of the antrum, and this may play an important role in the success of H. pylori eradication. Inflammation degrades the mucus and epithelial layers and alters the vascular and epithelial permeability; these effects may result in better penetration and delivery of drugs[9,10].

Previous reports indicate that moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy results in high rates of eradication. The eradication rate of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as first-line treatment is between 84.1% and 89%, and it results in a higher eradication rate compared to standard triple therapy[11,12]. Furthermore, it demonstrates good efficacy as second-line treatment with eradication rates up to 90% in reports from 2008[6,7]. Although bismuth-containing quadruple therapy has generally been used as a second-line therapy[13], moxifloxacin-containing therapy is preferred owing to poor compliance related to side effects, complicated dosing schedules, and low eradication rate with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy[14]. Other studies have also indicated that the use of levofloxacin-containing triple therapy as rescue treatment is effective by itself and more so than bismuth-containing quadruple therapy[15,16].

Resistance to any form of treatment is increasing, presenting difficulties in identifying the most effective treatment. A recent study conducted in South Korea demonstrated that the resistance of H. pylori to fluoroquinolone is increasing, and the authors indicated that a fluoroquinolone-based regimen is not adequate for first- or second-line eradication therapy[17]. Fluoroquinolone exhibits bacteriostatic activity by interfering with topoisomerase II (DNA gyrase) and topoisomerase IV, and DNA gyrase interrupts the DNA synthetic process in H. pylori. The mechanism of resistance in H. pylori has been associated with mutation of the fluoroquinolone resistance determining region of gyrA in DNA gyrase[18,19]. This results in a decrease in the eradication rates observed using moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment[3,8]. In 2004, the primary resistance rate to moxifloxacin was low (5.6%); however, the rate of resistance dramatically increased to 28.2% over the following 4 years[8]. In recent data, the documented resistance rate was as high as 34.6% in 2009-2012[3]. This rapid increase in moxifloxacin resistance might be explained by cross-resistance to other fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. Fluoroquinolones are being prescribed more frequently for other diseases such as respiratory and urinary tract infections potentially resulting in an increase in antibiotic resistance by H. pylori[8,20].

Amoxicillin resistance is also increasing in South Korea. Lee et al[3] reported that the prevalence of amoxicillin resistance was 7.1% from 2003 to 2005 and 18.5% from 2009 to 2012. Although a decrease in the eradication rate by standard triple therapy as first-line treatment and moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment has been observed, the effect of amoxicillin resistance on treatment remains controversial. It is difficult to determine if the resistance to amoxicillin itself is a problem such as the resistance previously demonstrated by clarithromycin and levofloxacin[3,21].

Several regimens, including standard triple therapy, are recommended as first-line therapy. The Korean Society of Gastroenterology announced a revised edition of the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection in 2013. One important change is that bismuth-containing quadruple therapy is recommended as first-line therapy[4]. In addition, several countries recommend the use sequential therapy, because previous reports have indicated that it is more effective than standard triple therapy for first-line treatment[5,22,23]. Furthermore, concomitant therapy is also effective for H. pylori eradication[24]. However, almost all of these regimens include amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, or tetracycline, and there are very few recommendations for the use of antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones after the failure of first-line treatment.

The use of an antibiotic susceptibility test for H. pylori is ideal; however, it is difficult to conduct in local clinics, and it is easy to choose fluoroquinolone antibiotics in the absence of a test. The use of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as rescue treatment without an antibiotic susceptibility test in the current study resulted in low rates of eradication. Sitafloxacin, also a fluoroquinolone, has a low minimum inhibitory concentration, and H. pylori demonstrates low resistance to its effects; therefore; it has recently been used in Japan. Triple therapy with sitafloxacin, PPI, and amoxicillin as third-line treatment has demonstrated high eradication rates of approximately 70%-90%[25,26]. However, it is not yet available in South Korea. We recommend that antibiotic susceptibility tests should be conducted before the selection of a second-line regimen.

This study had several limitations. First, it was retrospectively conducted in a single center. Second, the proportion of patients who received standard triple therapy was higher than those who received the other regimens due to health insurance coverage and typically low compliance to bismuth-containing quadruple therapy. Third, the rate of eradication was higher when esomeprazole was used than when rabeprazole was used, particularly in the PP analysis (P = 0.028) (Table 4). We selected only rabeprazole and esomeprazole because they were less influenced by polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C 19[27,28]. However, we compared the effectiveness of rabeprazole and esomeprazole only in those who received 14 d of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy, while esomeprazole was used almost exclusively in the patients who received 7 d of therapy.

Table 4.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates due to 14-d moxifloxacin triple therapy according to proton pump inhibitors

| Esomeprazole | Rabeprazole | P value1 | |

| ITT analysis | |||

| % Eradication (ratio) | 73.8% (127/172) | 63.6% (28/44) | 0.180 |

| 95%CI | 66.8-79.8 | 48.9-76.2 | |

| PP analysis | |||

| % Eradication (ratio) | 80.9% (127/157) | 65.1% (28/43) | 0.028 |

| 95%CI | 74.0-86.3 | 50.2-77.6 |

Pearson's χ2 test. ITT: Intention to treat; PP: Per protocol.

In conclusion, the use of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment demonstrated low rates of H. pylori eradication, although 14 d of therapy was more effective than 7 d of therapy. There were also no significant differences in efficacy according to the type of failed first-line regimens. Therefore, tailored treatment based on antibiotic susceptibility tests may be more effective for achieving high eradication rates when first-line therapy fails.

COMMENTS

Background

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is an important cause of stomach cancer. Treatment has the potential to prevent malignancy. However, there has been a decrease in the rate of H. pylori eradication due to an increase in resistance to clarithromycin and amoxicillin and a decrease in the success rate of standard triple therapy as first-line treatment. Thus, various regimens, such as sequential and concomitant therapy, have also been used for the treatment of H. pylori infection. However, rescue regimens have not been well established after failed sequential and concomitant therapy as first-line treatments.

Research frontiers

Fluoroquinolones are a relatively new class of antibiotic. Levofloxacin is the most commonly used fluoroquinolone worldwide for the treatment of H. pylori infection. However, the efficacy of levofloxacin-containing triple therapy is unsatisfactory in South Korea. In contrast, moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy has shown encouraging results as a first- and second-line treatment, therefore, we chose moxifloxacin instead of levofloxacin as second-line treatment. This study aimed to investigate moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for H. pylori following failed first-line therapies, and moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment demonstrated low rates of H. pylori eradication.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for H. pylori following the failure of first-line regimens.

Applications

This study offers therapeutic options for patients who failed first-line treatment of H. pylori infection.

Terminology

Moxifloxacin is a fourth generation synthetic fluoroquinolone antibacterial agent. It is a broad spectrum bactericidal antibiotic and is active against both Gram positive and negative bacteria. It functions by inhibiting topoisomerase II (DNA gyrase) and topoisomerase IV, essential enzymes that maintain the superhelical structure of DNA.

Peer review

This study may support the guideline recommendation for treatment of H. pylori infection.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Chmiela M, Ozen H, Shimatani T S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, Jang JY, Lee H, Kim CG, Shin WG, Shin ES, Lee YC. [Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;62:3–26. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2013.62.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asaka M, Kato M, Takahashi S, Fukuda Y, Sugiyama T, Ota H, Uemura N, Murakami K, Satoh K, Sugano K. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2009 revised edition. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheon JH, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Efficacy of moxifloxacin-based triple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2006;11:46–51. doi: 10.1111/j.0083-8703.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miehlke S, Krasz S, Schneider-Brachert W, Kuhlisch E, Berning M, Madisch A, Laass MW, Neumeyer M, Jebens C, Zekorn C, et al. Randomized trial on 14 versus 7 days of esomeprazole, moxifloxacin, and amoxicillin for second-line or rescue treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2011;16:420–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon H, Kim N, Lee BH, Hwang TJ, Lee DH, Park YS, Nam RH, Jung HC, Song IS. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: effect of treatment duration and antibiotic resistance on the eradication rate. Helicobacter. 2009;14:77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domingo D, Alarcón T, Vega AE, García JA, Martínez MJ, López-Brea M. [Microbiological factors that influence the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in adults and children] Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2002;20:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(02)72838-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gisbert JP, Marcos S, Gisbert JL, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is more effective in peptic ulcer than in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1303–1307. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzhen Y, Kehu Y, Bin M, Yumin L, Quanlin G, Donghai W, Lijuan Y. Moxifloxacin-based triple therapy versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy for first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Intern Med. 2009;48:2069–2076. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nista EC, Candelli M, Zocco MA, Cazzato IA, Cremonini F, Ojetti V, Santoro M, Finizio R, Pignataro G, Cammarota G, et al. Moxifloxacin-based strategies for first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1241–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, Hunt R, Azuma T, Sugano K, Xiao SD, Lam SK, Goh KL, Chiba T, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:351–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu C, Chen X, Liu J, Li MY, Zhang ZQ, Wang ZQ. Moxifloxacin-containing triple therapy versus bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for second-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2011;16:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad RJ, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, Chey WD. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung JW, Lee GH, Jeong JY, Lee SM, Jung JH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Jung HY, Kim JH. Resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains to antibiotics in Korea with a focus on fluoroquinolone resistance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JW, Kim N, Nam RH, Park JH, Kim JM, Jung HC, Song IS. Mutations of Helicobacter pylori associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Korea. Helicobacter. 2011;16:301–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore RA, Beckthold B, Wong S, Kureishi A, Bryan LE. Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene and characterization of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:107–111. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carothers JJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bensler M, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Parkinson AJ, Coleman JM, McMahon BJ. The relationship between previous fluoroquinolone use and levofloxacin resistance in Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e5–e8. doi: 10.1086/510074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JM, Kim JS, Kim N, Jung HC, Song IS. Distribution of fluoroquinolone MICs in Helicobacter pylori strains from Korean patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:965–967. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liou JM, Chen CC, Chen MJ, Chen CC, Chang CY, Fang YJ, Lee JY, Hsu SJ, Luo JC, Chang WH, et al. Sequential versus triple therapy for the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:205–213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon JH, Lee DH, Song BJ, Lee JW, Kim JJ, Park YS, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Lee SH, et al. Ten-day sequential therapy as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: a retrospective study. Helicobacter. 2010;15:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: non-bismuth quadruple (concomitant) therapy for eradication of Helicobater pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:604–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami K, Furuta T, Ando T, Nakajima T, Inui Y, Oshima T, Tomita T, Mabe K, Sasaki M, Suganuma T, et al. Multi-center randomized controlled study to establish the standard third-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1128–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furuta T, Sugimoto M, Kodaira C, Nishino M, Yamade M, Uotani T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Yamada T, Osawa S, et al. Sitafloxacin-based third-line rescue regimens for Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:487–493. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo CH, Wang SS, Hsu WH, Kuo FC, Weng BC, Li CJ, Hsu PI, Chen A, Hung WC, Yang YC, et al. Rabeprazole can overcome the impact of CYP2C19 polymorphism on quadruple therapy. Helicobacter. 2010;15:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kita T, Tanigawara Y, Aoyama N, Hohda T, Saijoh Y, Komada F, Sakaeda T, Okumura K, Sakai T, Kasuga M. CYP2C19 genotype related effect of omeprazole on intragastric pH and antimicrobial stability. Pharm Res. 2001;18:615–621. doi: 10.1023/a:1011025125163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]