Abstract

Cell death is a critical biological process, serving many important functions within multicellular organisms. Aberrations in cell death can contribute to the pathology of human diseases. Significant progress made in the research area enormously speeds up our understanding of the biochemical and molecular mechanisms of cell death. According to the distinct morphological and biochemical characteristics, cell death can be triggered by extrinsic or intrinsic apoptosis, regulated necrosis, autophagic cell death, and mitotic catastrophe. Nevertheless, the realization that all of these efforts seek to pursue an effective treatment and cure for the disease has spurred a significant interest in the development of promising biomarkers of cell death to early diagnose disease and accurately predict disease progression and outcome. In this review, we summarize recent knowledge about cell death, survey current and emerging biomarkers of cell death, and discuss the relationship with human diseases.

1. Introduction

Cell death is a fundamental biological process which has been mediated via intracellular program of biological systems [1–3]. Growing evidence has provided an expanding view for the existence of various types of cell death. Nonetheless, with different criteria, cell death can be classified into different subroutines and different subroutines of cell death own a distinct molecular mechanism and morphological characters and perform different roles in regulating the fate of cells [4]. And then along with progress and substantial insights into the biochemical and molecular mechanism exploration of cell death, its classification from the initial morphology has now been transformed to the biochemical characteristics. A functional classification suggested by the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death (NCCD) based on the biochemical characteristics, including extrinsic as well as intrinsic apoptosis, regulated necrosis, autophagic cell death, and mitotic catastrophe, has been widely accepted [5].

In natural state cell death plays an important role during the development, maintenance of tissue homeostasis, and elimination of damaged cells [1]. One of the typical examples is that once a cell infected by virus has DNA damage or cell cycle disturbed, cell death will eliminate this cell to ensure the normal life activities of organism [1, 6]. On the contrary, excessive or defective cell death contributes to a broad spectrum of human pathologies; low-rate cell death can result in cancer formation and autoimmune disease [7–9], while high-rate cell death can result in neurodegenerative disease, immunodeficiency, and muscle atrophy [10–13]. Insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in cell death will likely have important implications and offer the opportunity to target this process for therapeutic purposes. However, the rational treatment design and selection are often precluded due to the lack of adequate biomarkers for stratifying patient subgroups. Therefore, central to current research and clinical efforts is the need for finding cell death biomarkers for early detection, diagnosis, and prognosis that can provide more accurate personalized management [14]. In this review, we summarize recent literatures on cell death biomarkers and discuss the relationship with human diseases.

2. Extrinsic as well as Intrinsic Apoptosis

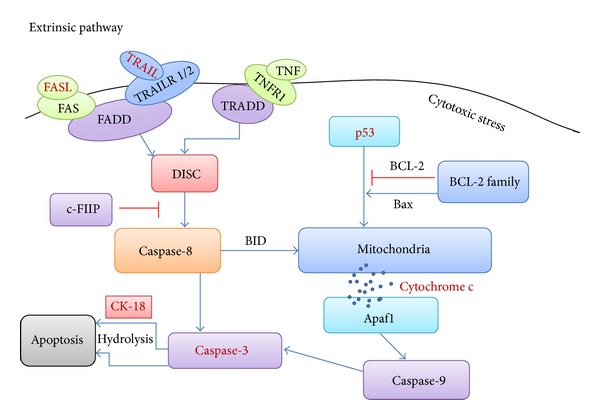

Apoptosis, being a highly complex and sophisticated process, involves a series of complex biochemical events leading to a spatiotemporal sequence of morphological changes, such as nuclear condensation and fragmentation, as well as plasma membrane blebbing [15]. Characteristic biochemical events of cells undergoing apoptosis include activation of effectors caspases (caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7), mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), and activation of catabolic hydrolases [16]. Apoptosis can occur via extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, which are initiated either by extracellular death receptors, such as FAS, TNF-α, and TRAIL, or by intracellular stimuli, such as DNA damage, hypoxia, and nutrient deprivation [12] (Figure 1). Of note, the signaling cascades triggering intrinsic apoptosis are highly heterogeneous, whose triggering can proceed in a caspase-dependent or caspase-independent manner [17]. Moreover, there is accumulating evidence that cross-talk exists between extrinsic and intrinsic pathways [18].

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram of apoptosis.

Extrinsic apoptosis is always initiated by the activation of Fas cell surface death receptor (FAS) or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) which can recruit the adaptor molecules, Fas-associating protein with death domain (FADD), while it also can be stimulated by TNFR1 which can recruit TNFR1-associated death domain (TRADD). The activated FADD or TRADD leads to the formation and activation of DISC activating caspase-8. As an inhibitor, c-FIIP inactivates caspase-8 to suppress the apoptosis. The activated caspase-8 promotes the activation of caspase-3, which in turn induces the characteristics of apoptosis. Intrinsic apoptosis is triggered by cytotoxic stress resulting in the activation of p53, which promotes mitochondrial cytochrome c release into the cytosol. This process can be regulated by BCL-2 family and also triggered by BID which stimulated by extrinsic pathway. The dissociative cytochrome c binds with Apaf1 from the apoptosome to activate caspase-9. Then caspase-3 will be activated by caspase-9 finally resulting in apoptosis. In addition, caspase-3 promotes the apoptosis through hydrolyzing Ck-18 during the final stage.

3. Autophagic Cell Death

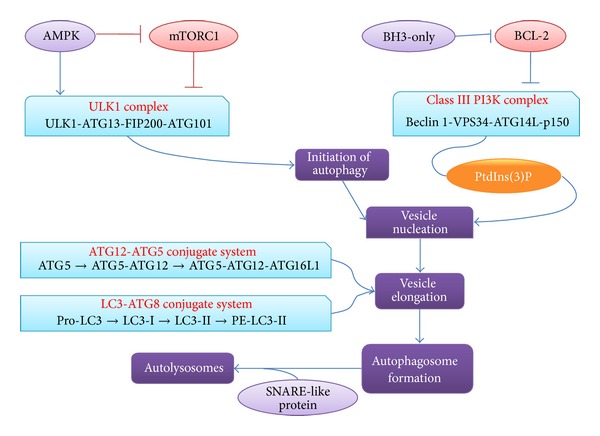

Autophagy is an essential and conserved catabolic process, which is initiated by the nucleation of isolation membrane [19] (Figure 2). This is followed by the expansion of this membrane to form the autophagosome and fuse with the lysosome to degrade cellular components [20]. Autophagic cell death is mediated by autophagy and autophagy-related proteins and that is characterized by mTOR suppression as well as Atg activation and reaction [21]. When subjected to a variety of stress stimuli, such as energy depletion or nutrient deprivation [22], autophagic cell death can be initiated by the enhanced autophagic flux, which can also be prevented by the suppression of autophagy by chemicals and/or genetic means, such as agents targeting VPS34 or RNAi targeting essential autophagic modulators, such as ATG5 or Beclin 1 [23, 24]. It should be noted that the precise molecular mechanisms regulating autophagic cell death remain to be determined [25].

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram of autophagic cell death.

The initiation of autophagy is triggered during the starvation environment which leads to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and inactivation of the rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). Both of these two mechanisms can promote the formation and activation of ULK1 complex which consists of ULK1, ATG13, FIP200, and ATG101. Vesicle nucleation mainly involves the activation of autophagy-specific class III PI3 K complex to form phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PtdIns(3)P). Class III PI3 K complex can be inactivated by BCL-2, while BCL-2 homology 3- (BH3-) only proteins can induce autophagy by competitively disrupting the interaction between Beclin 1 and BCL-2. Vesicle elongation process involves two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: ATG12-ATG5 conjugate system and LC3-ATG8 conjugate system. Once the vesicle was completed, an autophagosome formed. Then the fusion between autophagosome and lysosome is mediated by several SNARE-like proteins and forms autolysosomes.

4. Regulated Necrosis

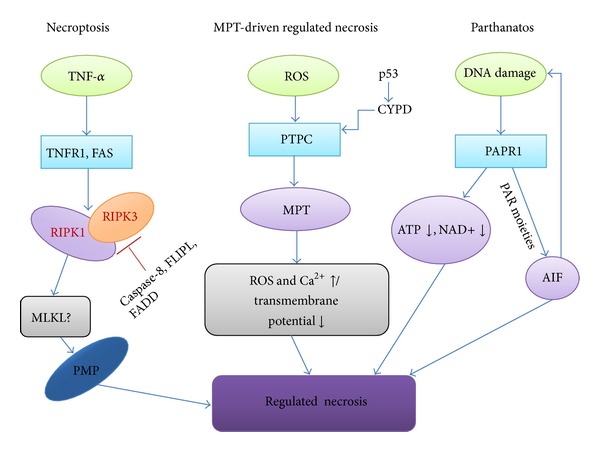

Regulated necrosis, being a genetically controlled process, can occur in a highly regulated manner [26] and is characterized by a series of morphological changes, including cytoplasmic granulation, as well as organelle and/or cellular swelling [26]. Meanwhile, regulated necrosis is accompanied by some biochemical events, including caspase inhibition, NADPH oxidase activation, and NET release [27, 28]. Regulated necrosis can be triggered in response to a variety of physicochemical insults, including alkylating DNA damage, excitotoxins, and the ligation of death receptors [5]. Clearly, substantial advances in the characterization of the molecular mechanisms have rapidly increased our understanding of regulated necrosis. With regard to its dependence on specific signaling pathways, regulated necrosis can be further divided into different types characterized by (but not limited to) necroptosis, mitochondrial permeability transition- (MPT-) dependent regulated necrosis, and parthanatos [5, 29] (Figure 3). Of note, they are interconnected and overlapping with each other at the molecular level that impinges on common mechanisms, such as redox metabolism and bioenergetics, to result in the similar morphology [26].

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram of regulated necrosis.

Regulated necrosis at least can be divided into three different pathways, including necroptosis, MPT-dependent regular necrosis, and parthanatos. In the necroptosis pathway, the activation of TNF-alpha/FASL binds to their receptors TNFR1/FAS to activates the RIPK1 and RIPK3 which in turn phosphorylate the mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL). The activated MLKL promotes the activation of plasma membrane permeabilization (PMP) and then triggers the necrosis. During this pathway, caspase-8, FLIPL, and FADD act as inhibitors of regular necrosis to suppress the activation of RIPK3. In the MPT-dependent regular necrosis pathway, transition pore complex (PTPC) plays a key role in mitochondrial permeability transition which leads to the abrupt increase of ROS and Ca2+ in the cytoplasm, resulting in the regular necrosis. In the parthanatos pathway, poly-ADP-ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1) starts to repair the damaged DNA, leading to the decrease of ATP and the hyperactivation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) promoting the regular necrosis.

5. Mitotic Catastrophe

Mitotic catastrophe acts as an oncosuppressive mechanism that can occur either during or after mitosis to precede cell apoptosis, necrosis, or senescence [30]. It is characterized by unscheduled activation of cyclin B1-CDK1, TP53, or TP73, caspase-2 activation, and mitotic arrest [30–33]. Several processes have been shown to be dispensable for mitotic catastrophe that can be initiated in response to a series of triggers, including perturbation of the mitotic apparatus and chromosome segregation early in mitosis [30, 34]. During the past few years, although progress has unraveled a myriad of pathways that can induce mitotic catastrophe, it is still poorly understood [30, 35].

6. Current and Emerging Biomarkers of Cell Death

Currently, much attention has been given to cell death and focused on developing biomarkers, but only a few of cell death-related genes have been identified as molecular biomarkers. Most frequently described are the death receptors and their ligands, caspases, cytokeratin-18, p53, and others (Table 1). More recently, breakthroughs have identified a number of noncoding RNAs as biomarkers such as microRNAs and lncRNAs that are present in the execution of cell death [36, 37].

Table 1.

Cell death biomarkers in human diseases.

| Official symbol | Official full name | Clinical relevance | Function | Pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASP3 | Caspase-3, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | A potential new biomarker for myocardial injury and cardiovascular disease | Caspase-3 is responsible for chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation | Apoptosis | [96] |

|

| |||||

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 | Implications for the regulation and execution of apoptosis in colorectal cancer and other cancers. | TP53 activation is capable of inducing apoptosis by intrinsic pathway. | Apoptosis | [97] |

|

| |||||

| KRT18 | Keratin 18 | A biomarker of liver damage and apoptosis in chronic hepatitis C | CK18-Gly(−) involves the inactivation of Akt1 and protein kinase Cθ | Apoptosis | [98–100] |

|

| |||||

| FAS | Fas cell surface death receptor | Granulomatous disease | Fas can increase the antigen-specific CD8(+) T-cell responses during viral infection | Apoptosis | [101, 102] |

|

| |||||

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 10 | Inducing the autoimmune inflammation in SLE | TRAIL directly induces apoptosis through an extrinsic pathway, which involes the activation of caspases. | Apoptosis | [103] |

|

| |||||

| MAP1LC3A | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha | Neurodegenerative and neuromuscular diseases, tumorigenesis, and bacterial and viral infections | LC3-II functions in phagophore expansion and also in cargo recognition | Autophagy | [104, 105] |

|

| |||||

| BECN1 | Beclin 1, autophagy related | Human breast cancers and ovarian cancers | BECN1 is part of a Class III PI3K complex that participates in autophagosome formation, mediating the localization of other autophagy proteins. | Autophagy | [106] |

|

| |||||

| RIPK1 | Receptor (TNFRSF)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | Involving retinal disorders including retinitis pigmentosa and retinal detachment | RIPK1 and RIPK3 association forms a necrosis-inducing complex, initiates cell-death signals (programmed necrosis). | Necrosis | [107–109] |

|

| |||||

| RIPK3 | Receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 3 | Atherosclerotic lesions and the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel | RIPK3 interacts with, and phosphorylates RIPK1 and MLKL to form a necrosis-inducing complex, then triggering necrosis. | Necrosis | [110–112] |

6.1. Current Biomarker

Death receptors are membrane-bound protein complexes that can activate an intracellular signaling cascade by binding specific ligands and play a central role in apoptosis [12, 38]. Death receptors belong to the TNFR (tumor necrosis factor receptor) superfamily whose members typically include Fas (also known as CD95, APO-1, and TNFRSF6), TNFR1 (also known as CD120a, p55, and p60), TRAILR1 (also known as DR4, CD261, and APO-2), and TRAILR2 (also known as DR5, KILLER, and CD262) [39]. These death receptors contain a cytoplasmic region of ~80 residues termed the death domain (DD) which provides the capacity for protein-protein interactions with other molecules [40]. Here, the most extensively studied death ligands are type II transmembrane proteins, including FasL (for Fas receptor), TNF (for TNFR1 receptor), and TRAIL (for TRAIL receptor) [41, 42]. After proteolytic cleavage of the membrane-anchored ligand, these ligands are released from the plasma membrane and enable them to bind to death receptors and trigger their activation [40]. Upon contacting with their corresponding ligands, these receptors are triggered, leading to the recruitment of a different set of adaptor molecules to the death domain and subsequent activation of the signaling cascade, where the major signals transmitted by death receptors such as Fas, TNFR1, TRAILR1, and TRAILR2 result in an apoptotic response mediated by intracellular caspases [43–48]. The above-mentioned associations give our hints and strategy guides for the death receptors and their ligands as potential biomarkers. In support of this notion, some of them have been shown to be utilized as biomarkers. For example, soluble Fas ligand is identified as a biomarker of thyroid cancer recurrence and may be useful for risk-adapted surveillance strategies in thyroid cancer patients [49]. Costagliola et al. demonstrated that TNF-alpha in tears can be used as a biomarker to assess the degree of diabetic retinopathy [50].

Caspases are a family of endoproteases that play an important role in maintaining homeostasis through regulating cell death [51]. According to their mechanism of action, caspases can be classified into two major types: one is initiator caspases, including caspase-2, caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-10, and the other is effector caspases, including caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7. Furthermore, initiators can be subdivided into caspases that participate in either the extrinsic (caspase-8 and caspase-10) or the intrinsic (caspase-2 and caspase-9) pathway [52]. As we know, the prodomain of different caspases is different, allowing them to interact with other different molecules that regulate their activities [51]. For example, caspase-1, caspase-2, caspase-4, caspase-5, caspase-9, caspase-12, and caspase-13 contain a caspase recruitment domain (CARD), whereas caspase-8 and caspase-10 have a death effector domain (DED) [53–55]. With complexing capacity of different molecules, caspases can be activated in different ways via granzyme B, death receptors, or apoptosome [56, 57]. For example, granzyme B, which can be released by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and NK cells, is able to activate caspase-3 and caspase-7 [58]. Fas, TRAIL, TNF, and other receptors can activate caspase-8 and caspase-10 [59, 60]. Again, apoptosome that is regulated by cytochrome c and the BCL-2 family can activate caspase-9 [61]. Initiator caspases promoting the caspase cascade reaction result in the activation of effector caspases which is achieved by cleavage of their inactive proforms and then trigger the apoptotic process [51]. There has been extensive effort to identify caspase as biomarkers, the most typical example being caspase-3 [12, 62–64]. For example, Simpson et al. indicated that the active mutant caspase-3 induced by doxycycline to drive synchronous apoptosis plays key roles in human colorectal cancer cells [62]. Singh et al. speculated that caspase-3 may be a potential new biomarker for myocardial injury and cardiovascular disease [63].

Cytokeratin-18 (CK-18) and other cytokeratins constitute the type I intermediate filaments of the cytoskeleton, which is present in epithelial cells [65]. CK-18, one of the most prominent substrates for lethal caspase activation, can be cleaved by caspases, primarily not only by caspase-9, but also by caspase-3 and caspase-7, and the subsequent release of CK-18 fragments into the extracellular space occurs during cell death [66]. Notably, there are several molecular forms of CK-18 released from dying cells that can be distinguished conveniently [67]. For example, apoptosis will lead to the release of caspase-cleaved CK-18 fragments, and necrosis will lead to release of uncleaved CK-18 [68]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that CK-18 and CK-18 fragments can be released from cells into blood [66, 67, 69, 70], suggesting the potential use of CK-18 fragments or CK-18 as noninvasive biomarkers of human diseases. Vos et al. measured plasma CK-18 levels in normal weight children and obese children with and without nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and found that its level is elevated in children with suspected NAFLD and was proposed as a diagnostic biomarker of NAFLD [69]. Feldstein et al. found that serum CK-18 fragment can be used as a useful biomarker for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in children with fatty liver disease [71]. In the review of usefulness of cytokeratin- (CK-) 18 fragments, the authors state that the caspase-cleaved fragment of cytokeratin-18 is a marker of chronic liver disease [72]. However, it should be noted that some issues with regard to the stability, reliability, and beneficial clinical utility of CK-18 and CK-18 fragments still need to be verified and answered.

In addition, DNA damage can also stimulate the transactivation of genes encoding proapoptotic proteins and trigger the apoptotic process in a p53-dependent manner [73]. The p53 is an important proapoptotic factor that is inactivated in a normal cell by its negative regulators [74]. MDM2 is the main negative regulator of p53 activity and stability [75]. A wide range of cellular stress stimuli, including DNA damage, hypoxia, and oncogene activation, can cause dissociation of the p53 from MDM2 complex [76, 77]. Once activated, p53 will induce apoptotic cell death by activating a series of positive regulators of apoptosis such as DR-5 and Bax [78, 79]. There is mounting evidence that p53 and MDM2 genes are used as biomarkers of cell death [80, 81]. Patil et al. reported using p53 as a prognostic biomarker of breast cancer [82]. Li et al. demonstrated that p53 immunohistochemical expression may serve as prognostic marker for the survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) patients receiving surgery [83]. Barone et al. indicated that targeting the interaction between p53 and its negative regulator MDM2 represents a new major therapeutic approach in poor prognosis of paediatric malignancies without p53 mutations [80].

6.2. Emerging Biomarker

Noncoding RNAs, including microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), are key regulatory molecules involved in multiple cellular processes. MicroRNAs are about 22 nt small noncoding RNA molecules, which function in transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression via mRNA cleavage or translational arrest [84]. It is established that they play an important role in cell death related pathway including autophagy and apoptosis [85–87]. Comparing to microRNA, lncRNAs are over 200 nt noncoding RNAs, which are emerging as new players in gene regulation as posttranscriptional regulators of splicing or as molecular decoys for microRNA [88]. Besides, some other mechanisms have been proposed to explain its mediated gene expression by lncRNA [89]. Although many lncRNAs have been identified, of all lncRNAs only few have been well characterized. Currently, emerging evidence suggests that microRNAs and lncRNAs may serve as diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers of human diseases [90]. For example, microRNA-21 (miR-21) is shown to be involved in apoptosis as well as inflammatory and fibrotic signaling pathways in acute kidney injury, which is now considered a novel biomarker aiding diagnosis and treatment of acute kidney injury [91]. MiR-497 is a potential prognostic marker in human cervical cancer and functions as a tumor suppressor by inducing caspase-3-dependent apoptosis to decrease cell growth [92]. MiR-181a functions as an oncogene by negatively regulating PRKCD, a promoter of apoptosis, to induce chemoresistance in cervical squamous cell carcinoma cells, and may provide a biomarker for predicting chemosensitivity to cisplatin in patients with cervical squamous cancer [93]. Recent demonstration that lncRNA silencing in preclinical models leads to cancer cell death and/or metastasis prevention, suggesting that they can be investigated as novel biomarkers, has triggered increasing interest [37]. An lncRNA has recently been found to play an important role in the growth and tumorigenesis of human gastric cancer and may be a potential biomarker for gastric cancer [94]. Weber et al. indicated that lncRNA MALAT1 might be applicable as a blood-based complementary biomarker for the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer [95].

7. Conclusions

In the past few years, accumulated knowledge continues to improve our understanding of the biological and biochemical processes during cell death. We have witnessed tremendous advances in the discovery and identification of novel cell death biomarkers for early detection, diagnosis, and prognosis of human diseases, with some biomarkers now in clinical utility. However, there are still debate and challenges regarding the cell death related biomarkers, including availability, stability, and accuracy of biomarkers. As far as a good biomarker is concerned, it should be present in peripheral body fluid and/or tissue such as blood, urine, and saliva. Second, it should be easy to detect, preferably in a quantifiable manner. Third, it should associate as specifically as possible with diseases. To achieve the goal, we need to find a clear path for biomarker translation from discovery to clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Oversea Scholars Project funded by Education Department of Heilongjiang Province (1155H012) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100901, U1304311).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Kongning Li, Deng Wu, and Xi Chen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell. 2011;147(4):742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engelberg-Kulka H, Amitai S, Kolodkin-Gal I, Hazan R. Bacterial programmed cell death and multicellular behavior in bacteria. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2(10):p. e135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407(6805):770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, et al. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2009;16(1):3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, et al. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2012;19(1):107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuzarte-Luís V, Hurlé JM. Programmed cell death in the developing limb. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2002;46(7):871–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su M, Mei Y, Sinha S. Role of the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in Cancer. Journal of Oncology. 2013;2013:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/102735.102735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mũoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2010;6(5):280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(3):485–495. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchal JA, Lopez GJ, Peran M, et al. The impact of PKR activation: from neurodegeneration to cancer. The FASEB Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonaldo P, Sandri M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2013;6:25–39. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicologic Pathology. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Su H, Gollapudi S. A paradox of immunodeficiency and inflammation in human aging: lessons learned from apoptosis. Immunity and Ageing. 2006;3, article 5 doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neves AA, Brindle KM. Imaging cell death. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;55:1–4. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.114264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishida K, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K. Crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in heart disease. Circulation Research. 2008;103(4):343–351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marino G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Self-consumption: the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochodrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397(6718):441–446. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(4):277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain MV, Paczulla AM, Klonisch T, et al. Interconnections between apoptotic, autophagic and necrotic pathways: implications for cancer therapy development. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2013;17:12–29. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyo J-O, Nah J, Jung Y-K. Molecules and their functions in autophagy. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2012;44(2):73–80. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;368:1845–1846. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1303158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Qin ZH. Coordination of autophagy with other cellular activities. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2013;34:585–594. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KS. Autophagy and cancer. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2012;44(2):109–120. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller S, Tavshanjian B, Oleksy A, et al. Shaping development of autophagy inhibitors with the structure of the lipid kinase Vps34. Science. 2010;327(5973):1638–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1184429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denton D, Nicolson S, Kumar S. Cell death by autophagy: facts and apparent artefacts. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2012;19(1):87–95. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:135–147. doi: 10.1038/nrm3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SJ, Li J. Caspase blockade induces RIP3-mediated programmed necrosis in Toll-like receptor-activated microglia. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e716 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remijsen Q, Kuijpers TW, Wirawan E, Lippens S, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. Dying for a cause: NETosis, mechanisms behind an antimicrobial cell death modality. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2011;18(4):581–588. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Krautwald S, Kroemer G, Linkermann A. Molecular mechanisms of regulated necrosis. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vitale I, Galluzzi L, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Mitotic catastrophe: a mechanism for avoiding genomic instability. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12(6):385–392. doi: 10.1038/nrm3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imreh G, Norberg HV, Imreh S, Zhivotovsky B. Chromosomal breaks during mitotic catastrophe trigger γH2AX-ATM-p53-mediated apoptosis. Journal of Cell Science. 2011;124(17):2951–2963. doi: 10.1242/jcs.081612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vakifahmetoglu H, Olsson M, Tamm C, Heidari N, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. DNA damage induces two distinct modes of cell death in ovarian carcinomas. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2008;15(3):555–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castedo M, Perfettini J-L, Roumier T, Kroemer G. Cyclin-dependent kinase-1: linking apoptosis to cell cycle and mitotic catastrophe. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2002;9(12):1287–1293. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura M, Yoshioka T, Saio M, Banno Y, Nagaoka H, Okano Y. Mitotic catastrophe and cell death induced by depletion of centrosomal proteins. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e603 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Portugal J, Mansilla S, Bataller M. Mechanisms of drug-induced mitotic catastrophe in cancer cells. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2010;16(1):69–78. doi: 10.2174/138161210789941801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eguchi A, Wree A, Feldstein AE. Biomarkers of liver cell death. Journal of Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1063–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crea F, Clermont PL, Parolia A, Wang Y, Helgason CD. The non-coding transcriptome as a dynamic regulator of cancer metastasis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9455-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo XX, Li Y, Sun C, et al. p53-dependent Fas expression is critical for Ginsenoside Rh2 triggered caspase-8 activation in HeLa cells. Protein Cell. 2014;5(3):224–234. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seirafian S, Prod'homme V, Sugrue D, et al. Human cytomegalovirus suppresses fas expression and function. Journal of General Virology. 2014;95:933–939. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.058313-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guicciardi ME, Gores GJ. Life and death by death receptors. The FASEB Journal. 2009;23(6):1625–1637. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-111005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reimers K, Radtke C, Choi CY, et al. Expression of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in keratinocytes mediates apoptotic cell death in allogenic T cells. Annals of Surgical Innovation and Research. 2009;3, article 13 doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-3-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maher S, Toomey D, Condron C, Bouchier-Hayes D. Activation-induced cell death: the controversial role of Fas and Fas ligand in immune privilege and tumour counterattack. Immunology and Cell Biology. 2002;80(2):131–137. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang YQ, Xiao CX, Lin BY, et al. Silencing of Pokemon enhances caspase-dependent apoptosis via fas- and mitochondria-mediated pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068981.e68981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messer MP, Kellermann P, Weber SJ, et al. Silencing of fas, fas-associated via death domain, or caspase 3 differentially affects lung inflammation, apoptosis, and development of trauma-induced septic acute lung injury. Shock. 2013;39:19–27. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318277d856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H-Q, Yu X-D, Liu Z-H, et al. Deregulated miR-155 promotes Fas-mediated apoptosis in human intervertebral disc degeneration by targeting FADD and caspase-3. Journal of Pathology. 2011;225(2):232–242. doi: 10.1002/path.2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mao ZG, Jiang CC, Yang F, Rick F. Thorne RFT, Hersey P, Zhang XD. TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human melanoma cells involves activation of caspase-4. Apoptosis. 2010;15(10):1211–1222. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saqr HE, Omran OM, Oblinger JL, Yates AJ. TRAIL-induced apoptosis in U-1242 MG glioma cells. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2006;65(2):152–161. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000199574.86170.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hetz CA, Hunn M, Rojas P, Torres V, Leyton L, Quest AFG. Caspase-dependent initiation of apoptosis and necrosis by the Fas receptor in lymphoid cells: onset of necrosis is associated with delayed ceramide increase. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115(23):4671–4863. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Owonikoko TK, Hossain MS, Bhimani C, et al. Soluble FAS ligand as a biomarker of disease recurrence in differentiated thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1503–1511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costagliola C, Romano V, De Tollis M, et al. TNF-alpha levels in tears: a novel biomarker to assess the degree of diabetic retinopathy. Mediators of Inflammation. 2013;2013:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/629529.629529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656.a008656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pop C, Salvesen GS. Human caspases: activation, specificity, and regulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(33):21777–21781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800084200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghavami S, Hashemi M, Ande SR, et al. Apoptosis and cancer: mutations within caspase genes. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2009;46(8):497–510. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.066944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakamaki K, Satou Y. Caspases: evolutionary aspects of their functions in vertebrates. Journal of Fish Biology. 2009;74(4):727–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alcivar A, Hu S, Tang J, Yang X. DEDD and DEDD2 associate with caspase-8/10 and signal cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22(2):291–297. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huai J, Jöckel L, Schrader K, Borner C. Role of caspases and non-caspase proteases in cell death. F1000 Biology Reports. 2010;2(1, article 48) doi: 10.3410/B2-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Caspase activation pathways: some recent progress. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2009;16(7):935–938. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adrain C, Murphy BM, Martin SJ. Molecular ordering of the caspase activation cascade initiated by the cytotoxic T lymphocyte/natural killer (CTL/NK) protease granzyme B. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(6):4663–4673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engels IH, Totzke G, Fischer U, Schulze-Osthoff K, Jänicke RU. Caspase-10 sensitizes breast carcinoma cells to TRAIL-induced but not tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis in a caspase-3-dependent manner. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25(7):2808–2818. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2808-2818.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald ER, III, El-Deiry WS. Suppression of caspase-8- and -10-associated RING proteins results in sensitization to death ligands and inhibition of tumor cell growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(16):6170–6175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307459101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marsden VS, O’Connor L, O’Reilly LA, et al. Apoptosis initiated by Bcl-2-regulated caspase activation independently of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome. Nature. 2002;419(6907):634–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simpson KL, Cawthorne C, Zhou C, et al. A caspase-3 “death-switch” in colorectal cancer cells for induced and synchronous tumor apoptosis in vitro and in vivo facilitates the development of minimally invasive cell death biomarkers. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e613 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh KP, Jaffe AS, Liang BT. The clinical impact of circulating caspase-3 p17 level: a potential new biomarker for myocardial injury and cardiovascular disease. Future Cardiology. 2011;7(4):443–445. doi: 10.2217/fca.11.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abu-Qare AW, Abou-Donia MB. Biomarkers of apoptosis: release of cytochrome c, activation of caspase-3, induction of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, increased 3-nitrotyrosine, and alteration of p53 gene. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health B: Critical Reviews. 2001;4(3):313–332. doi: 10.1080/109374001301419737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oshima RG. Apoptosis and keratin intermediate filaments. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2002;9(5):486–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.John K, Wielgosz S, Schulze-Osthoff K, Bantel H, Hass R. Increased plasma levels of CK-18 as potential cell death biomarker in patients with HELLP syndrome. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e886 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linder S, Havelka AM, Ueno T, Shoshan MC. Determining tumor apoptosis and necrosis in patient serum using cytokeratin 18 as a biomarker. Cancer Letters. 2004;214(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher MB, Zhang X-Q, McConkey DJ, Benedict WF. Measuring soluble forms of extracellular cytokeratin 18 identifies both apoptotic and necrotic mechanisms of cell death produced by adenoviral-mediated interferon α: possible use as a surrogate marker. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2009;16(7):567–572. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vos MB, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S, Carew JD, Whitington PF, McClain CJ. Cytokeratin 18, a marker of cell death, is increased in children with suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2008;47(4):481–485. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31817e2bfb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amory DW, Steffenson JL, Forsyth RP. Systemic and regional blood flow changes during halothane anesthesia in the Rhesus monkey. Anesthesiology. 1971;35(1):81–90. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197107000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feldstein AE, Alkhouri N, de Vito R, Alisi A, Lopez R, Nobili V. Serum cytokeratin-18 fragment levels are useful biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:1526–1531. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yilmaz Y. Systematic review: caspase-cleaved fragments of cytokeratin 18—the promises and challenges of a biomarker for chronic liver disease. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2009;30(11-12):1103–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yan HX, Wu HP, Zhang HL, et al. DNA damage-induced sustained p53 activation contributes to inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Oncogene. 2013;32:4565–4571. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roos WP, Kaina B. DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2006;12(9):440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iwakuma T, Lozano G. MDM2, an Introduction. Molecular Cancer Research. 2003;1(14):993–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Q, Liao L, Deng X, et al. BMK1 is involved in the regulation of p53 through disrupting the PML-MDM2 interaction. Oncogene. 2013;32:3156–3164. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurki S, Latonen L, Laiho M. Cellular stress and DNA damage invoke temporally distinct Mdm2, p53 and PML complexes and damage-specific nuclear relocalization. Journal of Cell Science. 2003;116(19):3917–3925. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu J, Wang Z, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhang L. PUMA mediates the apoptotic response to p53 in colorectal cancer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(4):1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627984100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shen Y, White E. p53-dependent apoptosis pathways. Advances in Cancer Research. 2001;82:55–84. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(01)82002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barone G, Tweddle DA, Shohet JM, et al. MDM2-p53 interaction in paediatric solid tumours: preclinical rationale, biomarkers and resistance. Current Drug Targets. 2014;15:114–123. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saddler C, Ouillette P, Kujawski L, et al. Comprehensive biomarker and genomic analysis identifies p53 status as the major determinant of response to MDM2 inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(3):1584–1593. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patil VW, Tayade MB, Pingale SA, et al. The p53 breast cancer tissue biomarker in Indian women. Breast Cancer. 2011;3:71–78. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S20695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 83.Li L, Fukumoto M, Liu D. Prognostic significance of p53 immunoexpression in the survival of oral squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Oncology Letters. 2013;6:1611–1615. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen K, Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(2):93–103. doi: 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li Y, Zhuang L, Wang Y, et al. Connect the dots: a systems level approach for analyzing the miRNA-mediated cell death network. Autophagy. 2013;9:436–439. doi: 10.4161/auto.23096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kren BT, Wong PY-P, Sarver A, Zhang X, Zeng Y, Steer CJ. microRNAs identified in highly purified liver-derived mitochondria may play a role in apoptosis. RNA Biology. 2009;6(1):65–72. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.1.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu J, Wang Y, Tan X, Jing H. MicroRNAs in autophagy and their emerging roles in crosstalk with apoptosis. Autophagy. 2012;8:873–882. doi: 10.4161/auto.19629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Deng G, Sui G. Noncoding RNA in oncogenesis: a new era of identifying key players. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013;14:18319–18349. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Krishnan J, Mishra RK. Emerging trends of long non-coding RNAs in gene activation. The FEBS Journal. 2014;281:34–45. doi: 10.1111/febs.12578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Y, Chen L, Chen B, et al. Mammalian ncRNA-disease repository: a global view of ncRNA-mediated disease network. Cell Death & Disease. 2013;4, article e765 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li YF, Jing Y, Hao J, et al. MicroRNA-21 in the pathogenesis of acute kidney injury. Protein Cell. 2013;4:813–819. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3085-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Luo M, Shen D, Zhou X, Chen X, Wang W. MicroRNA-497 is a potential prognostic marker in human cervical cancer and functions as a tumor suppressor by targeting the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Surgery. 2013;153:836–847. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen Y, Ke G, Han D, Liang S, Yang G, Wu X. MicroRNA-181a enhances the chemoresistance of human cervical squamous cell carcinoma to cisplatin by targeting PRKCD. Experimental Cell Research. 2014;320:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhao Y, Guo Q, Chen J, Hu J, Wang S, Sun Y. Role of long non-coding RNA HULC in cell proliferation, apoptosis and tumor metastasis of gastric cancer: a clinical and in vitro investigation. Oncology Reports. 2014;31:358–364. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weber DG, Johnen G, Casjens S, et al. Evaluation of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 as a candidate blood-based biomarker for the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Research Notes. 2013;6, article 518 doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Porter AG, Jänicke RU. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation. 1999;6(2):99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeestraten EC, Benard A, Reimers MS, et al. The prognostic value of the apoptosis pathway in colorectal cancer: a review of the literature on biomarkers identified by immunohistochemistry. Biomark Cancer. 2013;5:13–129. doi: 10.4137/BIC.S11475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chakraborty JB, Oakley F, Walsh MJ. Mechanisms and biomarkers of apoptosis in liver disease and fibrosis. International Journal of Hepatology. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/648915.648915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ku N-O, Toivola DM, Strnad P, Omary MB. Cytoskeletal keratin glycosylation protects epithelial tissue from injury. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12(9):876–885. doi: 10.1038/ncb2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kronenberger B, Von Wagner M, Herrmann E, et al. Apoptotic cytokeratin 18 neoepitopes in serum of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2005;12(3):307–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Montes-Berrueta D, Ramirez L, Salmen S, Berrueta L. Fas and FasL expression in leukocytes from chronic granulomatous disease patients. Investigación Clínica. 2012;53:157–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weant AE, Michalek RD, Khan IU, Holbrook BC, Willingham MC, Grayson JM. Apoptosis regulators Bim and Fas function concurrently to control autoimmunity and CD8+ T cell contraction. Immunity. 2008;28(2):218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.El-Karaksy SM, Kholoussi NM, Shahin RM, El-Ghar MM, Gheith Rel S. TRAIL mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of Egyptian SLE patients. Gene. 2013;527:211–214. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fullgrabe J, Klionsky DJ, Joseph B. The return of the nucleus: transcriptional and epigenetic control of autophagy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2014;15:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 conjugation system in mammalian autophagy. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2004;36(12):2503–2518. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402(6762):672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murakami Y, Miller JW, Vavvas DG. RIP kinase-mediated necrosis as an alternative mechanisms of photoreceptor death. Oncotarget. 2011;2(6):497–509. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Berghe TV. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Science Signaling. 2010;3(115):p. re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nature Immunology. 2000;1(6):489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin J, Li H, Yang M, et al. A role of RIP3-mediated macrophage necrosis in atherosclerosis development. Cell Reports. 2013;3:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Welz P-S, Wullaert A, Vlantis K, et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477(7364):330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhang D-W, Shao J, Lin J, et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science. 2009;325(5938):332–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1172308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]