Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate an evidence-based collaborative depression care intervention adapted to obstetrics and gynecology clinics compared with usual care.

METHODS

Two-site randomized controlled trial included screen-positive women (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 of at least 10) who then met criteria for major depression, dysthymia or both (Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview). Women were randomized to 12-months of collaborative depression management or usual care; 6, 12 and 18-month outcomes were compared. The primary outcomes were change from baseline to 12-months on depression symptoms and functional status. Secondary outcomes included at least 50% decrease and remission in depressive symptoms, global improvement, treatment satisfaction, and quality of care.

RESULTS

Participants were on average 39 years old, 44% were non-white and 56% had posttraumatic stress disorder. Intervention (n= 102) compared to usual care (n=103) patients had greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 12 months (P< .001) and 18 months (P=.004). The intervention group compared with usual care had improved functioning over 18 months (P< .05), were more likely to have an at least 50% decrease in depressive symptoms at 12 months (relative risk [RR]=1.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.11–2.73), greater likelihood of at least 4 specialty mental health visits (6 month RR=2.70, 95% CI1.73–4.20; 12 month RR=2.53, 95% CI 1.63–3.94), adequate dose of antidepressant (6-month RR=1.64, 95% CI 1.03–2.60; 12-month RR=1.71, 95%CI 1.08 2.73), and greater satisfaction with care (6-month RR=1.70, 95% CI 1.19–2.44; 12-month RR=2.26, 95% CI 1.52–3.36).

CONCLUSION

Collaborative depression care adapted to women’s health settings improved depressive and functional outcomes and quality of depression care.

INTRODUCTION

Major depression disproportionately affects women, with a lifetime prevalence of 21%1 and female-to-male ratio of approximately 2:1.2 Major depressive episodes occur throughout a woman’s lifespan, with highest rates during reproductive and menopausal transition years.3 Obstetrician–gynecologists (ob-gyns) are often the only providers that many women regularly see. One third of all visits for women aged 18–45 years and the majority of non-illness related visits for women under age 65 are provided by ob-gyns.4 Obstetrician–gynecologists estimate that 37% of their non-pregnant patients rely solely on them for routine care.5 Disadvantaged poor and minority women have the highest prevalence of depression and are more likely to seek routine care in gynecology rather than primary care settings.6

Collaborative care models that integrate depression care into primary care clinics show improvement in quality of mental health care and depression outcomes.7 Few studies have evaluated the adaptation of depression treatment models to obstetrics and gynecology settings.8 Although ob-gyns acknowledge the need for depression management, they perceive significant barriers for screening and treating depression, including inadequate training and lack of resources for follow-up care.9 Research documents marked gaps in diagnosis and quality of depression treatment in obstetrics and gynecology settings,10 greater than those observed for primary care.11,12

We conducted a randomized, controlled trial in two obstetrics and gynecology clinics, evaluating a 12 month collaborative depression care intervention. We hypothesized that patients assigned to the Depression Attention for Women Now (DAWN) study intervention would have improved depression treatment and functional outcomes, improved quality of care, and greater satisfaction with care, compared to patients assigned to usual care.

METHODS

A multi-site randomized, controlled trial with blinded assessment was designed to evaluate a collaborative care program for depression treatment in obstetrics and gynecology clinics. Women were randomized to a 12 month study intervention versus usual care, with 6 month, 12 month and 18 month follow-ups. Prior to randomization, the study team provided a depression management educational session for the study clinics’ providers, staff, and managers. The University of Washington institutional review board approved the study, all participants gave written consent, and safety was evaluated by a Data Safety and Monitoring Board. Study interventions and methods are described elsewhere in detail.13

Participants were recruited from November 2009 through December 2011 at two academic urban obstetrics and gynecology clinics with different patient populations: 1) underserved, racially and ethnically diverse, largely uninsured; and 2) mixed socioeconomic backgrounds, largely insured. Both clinic sites were staffed by attending and resident ob-gyn physicians, and Advanced Registered Nurse Practitioners.

During recruitment, clinic receptionists provided a one-page document explaining study goals and potential participant role to all patients at check-in. The research assistant then approached patients waiting for their provider and obtained verbal consent for study screening. Consenting participants were screened for depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)11,14 before or after seeing their provider.

Screen positive women (PHQ-9 score of at least 10) were eligible if they met criteria for major depression, dysthymia, or both on a structured psychiatric interview (Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)15; were English speaking; had phone access; and were at least 18 years old. Exclusions included: homelessness, alcohol or drug misuse (past three months), high suicide risk, at least 1 prior suicide attempt, bipolar or schizophrenic disorders, current severe domestic violence, or currently seeing a psychiatrist. Women taking antidepressants or other psychoactive medications, or receiving psychotherapy from non psychiatrist practitioners were eligible. All eligible, interested women were scheduled for an in-person baseline assessment, including informed consent and randomization.

Women were block randomized via computer off site (stratified by clinic site; pregnant versus non pregnant) to depression care management or usual care. We used random blocks with sizes 2 and 4 (alternated randomly) for pregnant women and random blocks with sizes 4 and 6 (alternated randomly) for non-pregnant women.

Collaborative care models integrate a team of mental health specialists to aid site clinicians in patient depression management7. Allied health specialists, such as nurse care managers, or social workers are utilized to enhance depression interventions and serve as depression care managers. Depression care managers provide evidence based psychotherapy, and track patient treatment responses, medications and compliance. Collaborative care models include team management, tracking systems, and weekly structured case reviews with a psychiatrist, depression care manager, and site clinician.

The DAWN intervention included an initial engagement session, proactive outreach for women missing sessions, choice of initial treatment, telephone visits, and social workers as depression care managers to address social barriers to treatment. Women randomized to the intervention had an initial engagement session with a depression care manager designed to: provide education about depression, elicit health concerns and barriers to treatment, and enhance participation in depression treatment.16 During the subsequent session, depression care managers obtained clinical history, reviewed educational materials, and described and discussed patient preferences for initiating treatment with either antidepressant medication or Problem Solving Treatment-Primary Care (PST-PC).17,18 Depression care managers also supported women with social interventions (e.g., financial assistance with medications or housing). All women received written depression educational materials.19,20

PST-PC, delivered by the depression care managers, has proven as effective as antidepressants for primary care patients with major depressive disorder.17 PST-PC was designed to attenuate depressive symptoms by assisting patients in developing skills to alleviate life events stresses or problems.18 Antidepressant medications (usually an SSRI) were chosen using a clinical algorithm that incorporated patient’s current medication use in addition to past response to antidepressants. All intervention patients were coached to increase positive activities (e.g., exercise, visiting a friend) that they had stopped due to depression.21

Depression care managers followed patients every 1–2 weeks (in-person or by telephone) for up to 12 months and monitored treatment response with the PHQ-9, utilizing a Microsoft Excel based tracking system. Medication and behavioral therapy recommendations were made at weekly team meetings attended by the depression care manager and physician consultants (psychiatrist and ob-gyn). Recommended medication changes were communicated by the depression care manager to the patient’s prescribing ob-gyn provider. Participants were monitored monthly for symptoms following a clinical response (≥50% decrease in PHQ-9 score from baseline), a remission (PHQ-9 score <5), or both.

Women with less than 50% improvement in depressive symptoms by 4–8 weeks received a revised treatment plan. Women on medication alone could receive an increased dosage, or switch to a different medication, with or without augmentation with PST-PC. Women receiving PST-PC could be augmented with, or switched to, a trial of antidepressant medication. Women with persistent symptoms despite collaborative care management were referred for specialty mental health treatment.

Depression care managers received one week of training that included PST PC instruction, a standardized depression care manager treatment manual,18 and training specific to women’s health (e.g. sexual assault, infertility, and domestic violence). Each depression care manager audio-recorded an introductory session and at least one PST PC session with a practice patient before certified as competent in the treatment model. In addition, at least one audio-recorded study participant session per depression care manager was reviewed by the psychologist (EL) for quality assurance using fidelity rating forms.18 Intervention fidelity feedback was given during weekly supervision to minimize intervention drift.

Women randomized to usual care were informed of their diagnosis by the research assistant and received a depression educational booklet.19 All patients had opportunity for referral to social work and psychiatric consultations. They were asked for consent to notify the provider of their depression diagnosis. Women with mild to moderate depression were encouraged to make a follow-up appointment with their ob-gyn and women with severe depression were triaged for immediate care.

Baseline data were collected by research assistants screening patients in each clinic. Outcomes were measured at 6, 12, and 18 months utilizing standardized questionnaires, collected by phone by a research assistant blinded to intervention status. Each follow-up period was defined as up to 2 weeks before and 16 weeks following the assigned time point. The primary outcomes were change from baseline to 12 months on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20 (SCL 20)22 and functional status on the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS).23 Secondary outcomes included: treatment response (at least 50% reduction in SCL 20 score from baseline), complete remission of depressive symptoms (SCL 20 score less than 0.5),22 Patient Global Improvement (PGI),24 and satisfaction with depression care.25–27 Quality of mental health care was assessed with standardized questions about antidepressant medication use (adequate dose defined as recommended starting dose on package insert, e.g. 20mg fluoxetine), counseling frequency in each 6-month period,26–28 and estimated intervention treatment costs per our previously described model29 (Appendix).

Demographic information included age, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, and insurance. Additional information was gathered, using specific validated questionnaires, for factors that could potentially confound results: currently pregnant, hormone use, medical comorbidity (Depression PORT Comorbidity Scale),30 current panic disorder (MINI 5.0.0 Panic Module),15 and post traumatic stress disorder (17 item PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL C).31 We used a PCL-C score of ≥45 which has the highest sensitivity and specificity for PTSD based on structured psychiatric interview.31

We estimated 118 participants were required in each group (N=236) to have an 80% chance, with a two-sided 5% significance level, of detecting an effect size of 0.5725 in the mean SCL-20 score.22 We estimated that a sample of 130 women per group (260 women) would have 69% power with a two sided 5% significance level of detecting an effect-size of 0.26 in the mean Sheehan Disability Score.32 These calculations allowed for correlations between 0.3 and 0.5 for our primary outcome across time and attrition up to 25%.

Analyses were conducted according to the intention to treat principle. Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables. Chi square tests of proportions, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were used to determine group differences on the dichotomous satisfaction, quality of care and depression response variables at each time point. Generalized estimating equation models (GEEs), allowing for inclusion of all available data in the estimates of the model parameters, examined treatment group trends over time. Robust standard errors were estimated33. A statistically significant treatment group-by-time interaction indicated differences in trends over time for the two groups. In the event of a non-significant interaction, the term was removed and the model re-fit; the main effects of time and group were then examined. We calculated the effect size for improvement in depressive outcomes at 12 months based on SCL-20 in order to compare our results with prior primary care meta-analyses of collaborative care trials.7 Number needed to treat (NNT) was calculated based on differences between intervention versus usual care of the percent of patients with a 50% or greater response to treatment at 12 months.

Clinic site was examined as a moderator in our models by testing clinic site as a 3-way interaction with group and time.

RESULTS

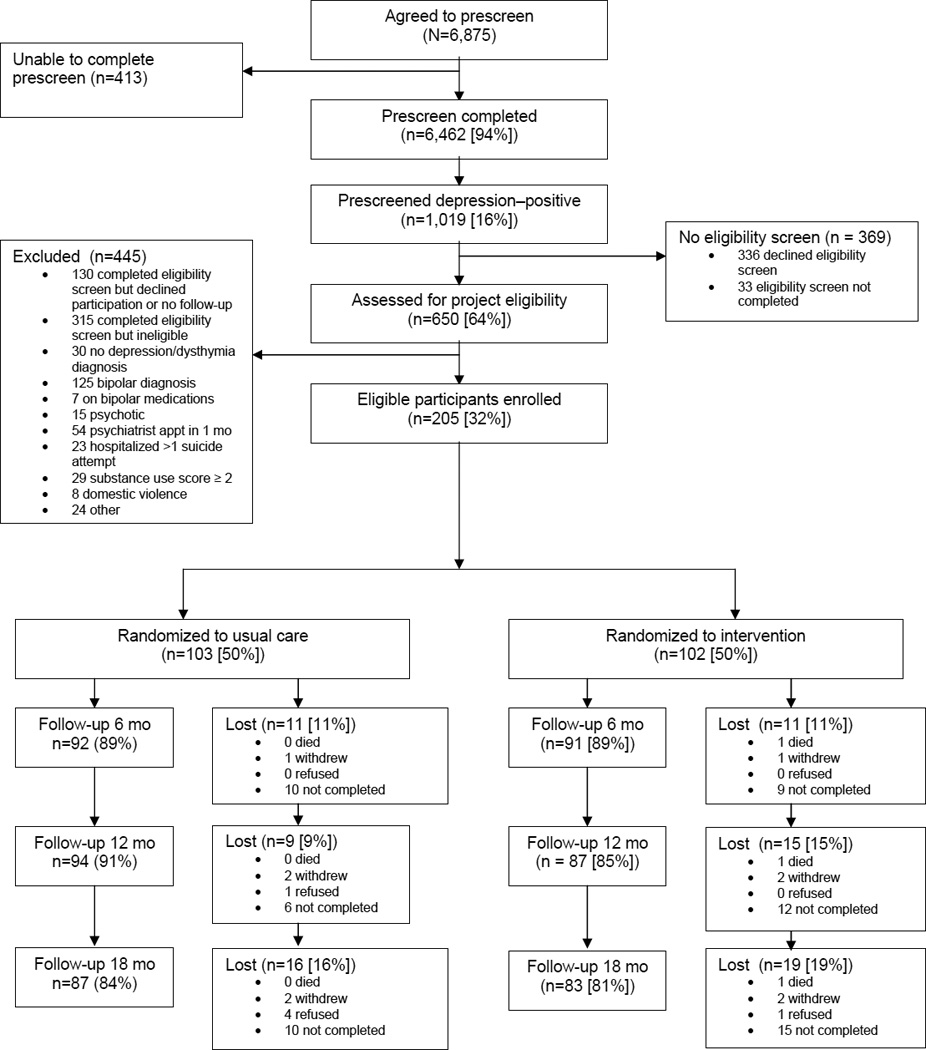

Of 6,875 patients who agreed to screening, 6,462 (94%) completed screening; 1,019 (16%) screened positive for major depression based on the PHQ-9 and 650 (64%) agreed to further eligibility screening (Figure 1). Of the 650, 445 were excluded and 205 (31%) were randomized. Of those randomized (102 Intervention, 103 Usual Care), follow-ups were completed at 6 months (89%), 12 months (88%), and at 18 months (83%).

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

“Lost” (no follow-up) categories: "refused" and "not completed" may have varied by time points, however "withdrew" and "death" were cumulative "Other" included: homeless/moving (n=12), participating in other research study (n=4), non-English speaking (n=3), medical illness (n=3), and changing provider (n=2).

There were no baseline differences between groups (Table 1). Participants were on average, 39 years (range 20–69), 48% were married or living with a partner, 40% had commercial health insurance, and 44% were non white. Ninety nine percent of patients met criteria for major depression, 33% met criteria for dysthymia, and 56% had PTSD.31

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Intervention (n = 102) |

Usual Care (n = 103) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 39.5 (12.1) | 38.6 (12.1) | .606 |

| Education, at least some college | 85.3 (87) | 85.4 (88) | 1.000 |

| Married or living with significant other | 50.0 (51) | 46.6 (48) | .676 |

| Race | |||

| White | 59.4 (60) | 54.4 (54) | |

| African American | 19.8 (20) | 21.4 (22) | .916 |

| Asian – Pacific Islander | 8.9 (9) | 8.7 (9) | |

| Hispanic | 5.0 (5) | 9.7 (10) | |

| Native American | 6.9 (7) | 5.8 (6) | |

| Insurance | |||

| None | 32.4 (33) | 29.1 (30) | |

| Medicaid/State | 23.6 (24) | 20.4 (21) | .722 |

| Medicare | 4.9 (5) | 6.8 (7) | |

| Private | 39.1 (40) | 43.7 (45) | |

| Number of chronic conditions, (PORT Comorbidity Scale), mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.6) | .839 |

| Pregnant, current | 7.8 (8) | 6.9 (7) | 1.000 |

| Currently taking hormones | 15.7 (14) | 9.2 (8) | .255 |

| Major depression diagnosis (MINI), current | 98.0 (100) | 99.0 (102) | .621 |

| Dysthymia diagnosis (MINI), current | 33.3 (34) | 34.3 (35) | 1.000 |

| Recurrent depression (≥ 2 episodes) | 74.5 (76) | 69.9 (72) | .171 |

| SCL-20 depression score, mean (SD) | 2.05 (0.61) | 1.96 (0.62) | .300 |

| PHQ-9 depression score, mean (SD) | 16.4 (4.1) | 15.9 (4.0) | .388 |

| Age at first depression episode, mean (SD) | 21.3 (10.3) | 22.0 (12.2) | .675 |

| SDS functional impairment score, mean (SD) | 6.20 (2.38) | 6.04 (2.31) | .646 |

| Panic Disorder (MINI 5.0 Panic Module), current | 10.8 (11) | 5.8 (6) | .217 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PCL-C score > 45), current | 53.9 (55) | 56.3 (59) | .780 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder PCL-C score, mean (SD) | 47.1 (12.2) | 46.0 (12.1) | .507 |

Data are % (n) unless otherwise specified.

SD, standard deviation; PORT Depression Comorbidity Scale, range 0 – 1929 ; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview diagnosis by structured interview15; SCL-20, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20, range 0–422 ; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 range 0–2711,14; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale, range 0 – 1023; PCL-C, Post-traumatic stress disorder Checklist - Civilian, range 17–85, > 45 = cut-off for PTSD.30

Most women in the Intervention group (96%) had at least one depression care manager visit. Intervention patients had a mean of 9.6 (SD=7.1) in-person visits and 6.4 (SD=6.0) telephone visits. Fifty-five women (53.9%) were treated with antidepressant medication and PST-PC, 32 (31.4%) with PST-PC alone, 12 (11.8%) with antidepressants alone, and 4 (3.9%) elected not to receive either treatment. The estimated cost per patient, including all depression care manager contacts, physician supervision, and information system support was $1,026 (Appendix).

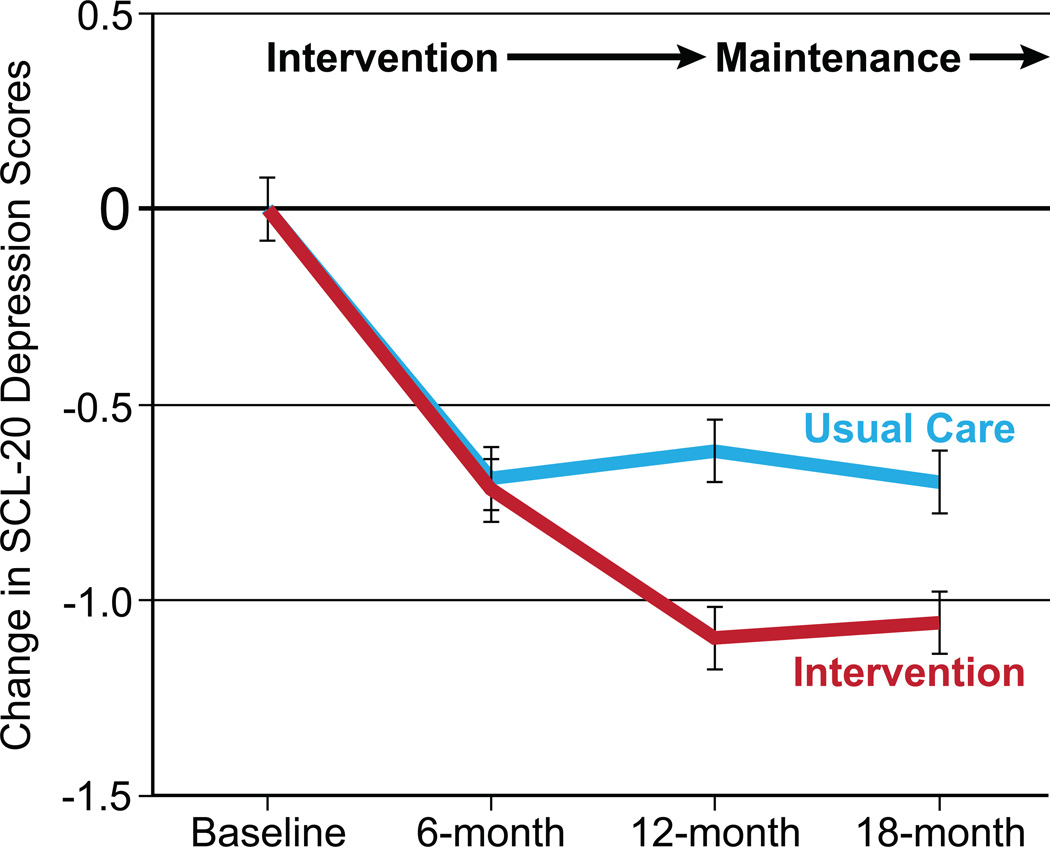

At 6 months, the reduction in depression symptom scores from baseline was similar, but at both 12 months (p<0.001) and 18- months (p=0.004), the intervention group demonstrated greater depression score decreases than the usual care group (Table 2, Figure 2). The model using baseline, 6 month, 12 month and 18 month follow-up SCL-20 continuous data showed a group by time interaction (Wald’s Chi Square = 28.36, df = 3, p<0.001). The effect size for improvement in depressive outcomes based on the SCL20 was 0.63 at 12 months.

Table 2.

Intervention Compared With Usual Care Differences in Primary Clinical Outcomes

| PRIMARY OUTCOMES |

Total N of Patients |

CONTINUOUS OUTCOMES | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Average Differences between groups Intervention – UC) Mean (95% CI) |

||||

| Intervention | Usual Care | ||||

| Decrease in depression score (SCL-20) from Baseline: | *<0.001 | ||||

| 6 Month | 183 | 0.72 (0.77) | 0.69 (0.76) | 0.03 (−0.25 to 0.19) | 0.779 |

| 12 Month | 181 | 1.10 (0.74) | 0.62 (0.78) | 0.48 (−0.70 to –0.25) | < 0.001 |

| 18 Month | 170 | 1.06 (0.74) | 0.70 (0.81) | 0.36 (−0.60 to –0.12) | 0.004 |

| Decrease in functional impairment score (SDS) from Baseline: | *<0.050 | ||||

| 6 Month | 183 | 1.58 (3.28) | 2.14 (2.60) | −0.56 (−0.30 to 1.43) | 0.200 |

| 12 Month | 180 | 2.56 (3.10) | 1.95 (2.67) | 0.62 (−1.46 to 0.23) | 0.154 |

| 18 Month | 169 | 2.56 (3.25) | 2.08 (3.36) | 0.47 (−1.48 to 0.42) | 0.354 |

SD = standard deviation;SCL-20, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20, range 0–422: SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), range 0 – 10.23

Group-by-time interaction: baseline to 18 months.

Figure 2. Mean change in depressive symptoms by study group.

The model-based estimates of the mean difference (standard error) in changes in depressive symptoms between the two groups (the change in the intervention group minus the change in the usual care or control group) at 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20 (SCL 20), range 0–4.22

The model for functional status improvement over the four assessments demonstrated a group by time interaction (Wald’s Chi Square = 7.82, df = 3, p=0.050) (Table 2). Although at 12 months and 18 months, the average functional improvement was greater for the intervention group, these differences were not significant.

The proportion of intervention patients with a depression treatment response (at least 50% decrease in SCL-20 scores from baseline) at 12 months (p=0.015) was greater than that for usual care, with a group by time effect (Wald’s Chi Square = 6.52, df = 2, p=0.031) (Table 3) and NNT of 4 (95% CI 3–10). Depression remission rates were higher in intervention compared with usual care patients at 18 months (p=0.045) but not at 6 months (p=0.655) or 12 months (p=0.195). The model for remission had a non-significant treatment group by time interaction (Wald’s Chi Square = 4.68, df = 2, p=0.096). The main effect model showed a time (Wald’s Chi Square = 8.77, df = 2, p=0.012) effect and a non-significant treatment effect (Wald’s Chi Square = 2.44, df = 1, p=0.118).

Table 3.

Intervention Compared With Usual Care Differences in Secondary Clinical Outcomes

| SECONDARY OUTCOMES |

Total N of Patients |

DICHOTOMOUS OUTCOMES | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients % (N) | Relative Risks (95% CI) |

||||

| Intervention | Usual Care | ||||

| Response (at least 50% decrease in depression score (SCL-20) from baseline: | *0.031 | ||||

| 6 Month | 183 | 37.4 (34) | 34.8 (32) | 1.07 (0.66 – 1.74) | 0.771 |

| 12 Month | 181 | 57.5 (50) | 33.0 (31) | 1.74 (1.11 – 2.73) | 0.015 |

| 18 Month | 170 | 55.4 (46) | 37.9 (33) | 1.46 (0.93 – 2.28) | 0.096 |

| Complete remission of depression symptoms (SCL-20 score < 0.5) | *0.096 | ||||

| 6 Month | 183 | 8.8 (8) | 10.9 (10) | 0.81 (0.32 – 2.05) | 0.655 |

| 12 Month | 181 | 20.7 (18) | 12.8 (12) | 1.62 (0.78 – 3.36) | 0.195 |

| 18 Month | 170 | 26.5 (22) | 12.6 (11) | 2.10 (1.02 – 4.32) | 0.045 |

| Patient rated global improvement (PGI), much or very much improved | *<0.001 | ||||

| 6 Month | 183 | 54.9 (50) | 33.7 (31) | 1.63 (1.04 – 2.55) | 0.032 |

| 12 Month | 181 | 77.0 (67) | 37.2 (35) | 2.07 (1.37 – 3.11) | < 0.001 |

| 18 Month | 170 | 69.9 (58) | 37.9 (33) | 1.84 (1.20 – 2.82) | 0.005 |

| Satisfaction with care received during the intervention period moderately or very satisfied | |||||

| 6 Months | 181 | 89.0 (81) | 52.2 (47) | 1.70 (1.19 – 2.44) | 0.004 |

| 12 Months | 177 | 89.5 (77) | 39.6 (36) | 2.26 (1.52 – 3.36) | < 0.001 |

SCL-20, Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20, range 0–422: PGI, Patient Global Improvement.24

Group-by-time interaction: baseline to 18 months.

A greater percentage of intervention versus usual care patients rated themselves as “much or very much improved” on the PGI scale at each time point (6-months, p=0.032; 12-months, p<0.001; 18-months, p=0 .005) (Table 3). The treatment group by time interaction was not significant (Wald’s Chi Square = 5.52, df = 2, p=0.063) but both the treatment (Wald’s Chi Square = 26.15, df = 2, p<0.001) and time effects (Wald’s Chi Square = 10.11, df = 1, p=0.006) were significant. Intervention patients reported greater satisfaction with depression care than usual care patients at 6 months (89.0% vs. 52.2%, p=0.004) and 12 months (89.5% vs. 39.6%, p<0.001).

Quality of care outcomes included number of mental health visits and antidepressant use/adherence (Table 4). Women receiving the intervention were more likely to have at least 4 mental health visits (including depression care manager visits) during the first 6 months (79.1% vs. 29.3%) and the second 6 months (74.9% vs. 30.8%), (both p<0.001). At baseline, the groups did not differ in self-reported antidepressant use, but at 6 months and 12 months, the intervention group showed non-significant higher rates of antidepressant use than the usual care group (Wald’s Chi Square = 4.19, df = 2, p=0.120). Re fitting the model showed no significant main effects of time or treatment group. Intervention women had higher rates of taking at least two antidepressants simultaneously at both 6 months and 12 months, with a group by time interaction (Wald’s Chi-square = 8.22, df = 2, p=0.013).

Table 4.

Intervention Compared With Usual Care Differences in Quality of Care

| Variable |

Total N of Patients |

Patients % (n) | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Usual Care |

||||

| 4 or more specialty mental health visits in prior 6 months | |||||

| 6 Months | 183 | 79.1 (72) | 29.3 (27) | 2.70 (1.73 – 4.20) | < 0.001 |

| 12 Months | 177 | 74.9 (67) | 30.8 (28) | 2.53 (1.63 – 3.94) | < 0.001 |

| Any antidepressant medication | 0.123* | ||||

| Baseline | 205 | 46.1 (47) | 49.5 (51) | 0.93 (0.63 – 1.38) | 0.722 |

| 6 Months | 183 | 61.5 (56) | 47.8 (44) | 1.29 (0.87 – 1.91) | 0.211 |

| 12 Months | 177 | 61.6 (53) | 47.3 (43) | 1.30 (0.87 – 1.95) | 0.196 |

| Two or more simultaneous antidepressant medications | 0.013* | ||||

| Baseline | 199 | 3.0 (3) | 7.1 (7) | 0.42 (0.11 – 1.61) | 0.204 |

| 6 Months | 183 | 24.2 (22) | 9.8 (9) | 2.47 (1.14 – 5.37) | 0.022 |

| 12 Months | 177 | 22.1 (19) | 7.7 (7) | 2.87 (1.21 – 6.83) | 0.017 |

| Any antidepressant for ≥ 25 days in the past month | 0.126* | ||||

| Baseline | 176 | 23.1 (21) | 18.8 (16) | 1.23 (0.64 – 2.35) | 0.539 |

| 6 Months | 182 | 56.0 (51) | 31.9 (29) | 1.76 (1.12 – 2.77) | 0.015 |

| 12 Months | 177 | 52.3 (45) | 33.0 (30) | 1.59 (1.01 – 2.52) | 0.050 |

| Any antidepressant for 3 of the past 6 months at an adequate dosage† | 0.021* | ||||

| Baseline | 177 | 14.3 (13) | 16.3 (14) | 0.88 (0.41 – 1.87) | 0.735 |

| 6 Months | 183 | 51.6 (47) | 31.5 (29) | 1.64 (1.03 – 2.60) | 0.037 |

| 12 Months | 168 | 57.1 (48) | 33.3 (28) | 1.71 (1.08 – 2.73) | 0.023 |

Group-by-time interaction: baseline to 12 months

Adequate dosage is the recommended starting dosage on package insert (eg, 20 mg of fluoxetine).

The model for antidepressant adherence (taking an antidepressant for at least 25 of the last 30 days) showed greater adherence in the intervention group vs usual care, although this difference was not statistically significant (Wald’s Chi square = 4.14, df = 2, p=0.123) (Table 4). Re fitting the model showed that both time (Wald’s Chi Square = 30.90, df = 2, p<0.001) and treatment group (Wald’s Chi Square = 7.25, df = 1, p=0.007) effects were significant, indicating greater antidepressant adherence in the intervention group at 6 months and 12 months compared to the usual care group. Intervention compared to usual care patients had higher rates of taking an antidepressant for at least three months in each 6 month period at a minimally adequate dosage with a significant time by group interaction (Wald’s Chi Square = 7.69, df = 2 p=0.021).

Clinic type was not found to be a moderating factor for any of the clinical outcomes. No 3-way, 2-way or main effects of clinic were observed.

Over the 18 month trial, one usual care patient had a psychiatrically related emergency room visit, and one intervention patient had a psychiatric hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

The DAWN intervention improved depression symptom and functional outcomes, adherence to evidence-based depression therapies, and overall treatment satisfaction in women, as compared with usual care. This depression intervention tailored for women was well-accepted and feasible to provide in the obstetrics and gynecology setting, even in clinics with high rates of poverty, PTSD and complex social challenges. These findings are noteworthy because obstetrics and gynecology clinics are the sole or primary source of health care for over one-third of women, including many underserved women who are at high risk for depression.3

The improved outcomes observed in our study of depression care customized for women’s health care settings, compare favorably to those observed in primary care clinics. In a recent meta analysis collaborative care was associated with significant improvement in depressive symptoms compared to usual primary care for up to two years.7 As in our study, collaborative care also increased the number of patients using guideline-supported medication, improved mental health related quality of life, and improved patient satisfaction with care. Remarkably, the effect-size for improvement in depressive outcomes in the current study was 0.63 at 12 months, which was approximately double that found in the primary care meta-analysis (0.34). The number needed to treat of 4 is similar to that found in a systematic review of antidepressant versus placebo treatment in medical populations34. Notably, our usual care group had opportunity for antidepressant therapy and mental health referral, thus the effectiveness of the DAWN intervention is all the more impressive. The improvement seen in these obstetrics and gynecology settings is important because ob-gyns rate their confidence in treating depression, and skills with counseling and antidepressant medication as less than internists or family physicians.12

The DAWN study population was unique in that over 50% of women had significant PTSD symptoms at baseline and over 50% were low-income. Both socio-economic deprivation35 and PTSD36 are associated with a higher prevalence and persistence of depression. This may explain why we saw a delayed response to collaborative depression care. Most other collaborative care studies in higher socio-economic populations have shown significant effects by six months,26,27 whereas we found few differences between intervention and usual care patients at six months but robust effects at 12-months and 18-months. For patients living in poverty, chronic stressors such as problems paying for medication and delays in receiving treatment37 may adversely affect treatment success. For women with depression and PTSD, the increased severity of their comorbid mental illness and symptoms like nightmares, flashbacks, and anxiety attacks makes them more complex to treat.36 A full 12 month intervention that includes an initial engagement session, proactive outreach, and social service management may be needed in settings serving women with high poverty and co-morbidities.

Strengths of our study included an intervention targeted to women, the randomized trial design, patient diversity, consistency of findings across sites, high rates of intervention adherence, and minimal missing data. Limitations self-report of antidepressant use, although earlier studies found high rates of agreement between self-reported antidepressant use and pharmacy database prescription fill data.26–28 Providers were not blinded to treatment group. There could have been a spillover/dilution effect of the intervention, since the same providers often had patients in both treatment groups; however, this would drive findings toward the null and the spillover effect is likely small given that the majority of the intervention depression care was delivered by a mental health team. Our study may not be generalizable to non-English speaking populations or smaller fee-for-service obstetrics and gynecology practices. Finally, our sample size did not allow sufficient power to analyze intervention effect by age group or by pregnancy status.

In summary, an integrated, collaborative stepped care model for women with depression being seen in obstetrics and gynecology clinics is feasible and significantly more effective than usual care in improving quality of mental health care, depressive and functional outcomes, and satisfaction with depression care, and can be provided at modest cost (not dissimilar to that of a pelvic MRI). Improving mental health care provision in women’s health care settings has important implications for U.S. families and society as a whole, particularly with upcoming anticipated changes in health care delivery.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Eddie Edmondson, Ms. Erin McCoy, Ms. Anna Harrington, Ms. Leiszle Ziemba, and Ms.Virginia Eader for assistance with data collection and tracking and Dr. Lee Cohen for chairing the data and safety monitoring board. We acknowledge Ms. Michal Inspektor and Ms. Julie Walwick (posthumously) for depression care management and Dr. Nancy Grote for training depression care managers in the engagement session.

Funding Source: National Institute of Mental Health - R01-MH085668

APPENDIX

Costs for intervention services estimated per our previously described model29 provided by study staff, which included caseload supervision, were calculated using actual salary and fringe benefit rates plus a 30% overhead rate (e.g. space, administrative support). The resulting unit costs were $80 for each care manager visit (typically 30 minutes and $31 for each telephone contact (typically 10–15 minutes). These estimates included the time required for outreach efforts and record-keeping (e.g. estimated 45 minutes of care manager time was allowed for these telephone contacts). Intervention costs also included a fixed $60 cost for each caseload supervision and information support.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Katon receives royalties reserved for research from The Depression Helpbook, Bull Publishing Co. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V. Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Psychol Med. 2010;40:225–237. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholle SH, Chang JC, Harman J, McNeil M. Trends in women's health services by type of physician seen: data from the 1985 and 1997–98 NAMCS. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12:165–177. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman VH, Laube DW, Hale RW, Williams SB, Power ML, Schulkin J. Obstetrician gynecologists and primary care: training during obstetrics-gynecology residency and current practice patterns. Acad Med. 2007;82:602–607. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180556885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miranda J, Azocar F, Komaromy M, Golding JM. Unmet mental health needs of women in public-sector gynecologic clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:212–217. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)80002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaRocco-Cockburn A, Melville J, Bell M, Katon W. Depression screening attitudes and practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:892–898. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly R, Zatzick D, Anders T. The detection and treatment of psychiatric disorders and substance use among pregnant women cared for in obstetrics. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:213–219. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JW, Jr, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, Ciotti MC, Zyzanski SJ, Cornell J. Primary care physicians' approach to depressive disorders. Effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:58–67. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaRocco-Cockburn A, Reed SD, Melville J, Croicu C, Russo JE, Inspektor M, et al. Improving depression treatment for women: Integrating a collaborative care depression intervention into OB-GYN care. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;36:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grote NK, Zuckoff A, Swartz H, Bledsoe SE, Geibel S. Engaging women who are depressed and economically disadvantaged in mental health treatment. Soc Work. 2007;52:295–308. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Day A, Baker F. Randomised controlled trial of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:26–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegel MT, Arean PA. Problem-solving treatment for primary care (PST-PC): A treatment manual for depression. Dartmouth, NH: Project IMPACT. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Mental Health. Depression: What Every Woman Should Know. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katon W, Ludman EJ, Simon GE. The depression helpbook. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing Co; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addis M, Martell C. Overcoming depression one step at a time: the new behavioral activation approach to getting your life back. New York: New Harbinger Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:79–110. doi: 10.1159/000395070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guy W National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.) ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: U. S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunders K, Simon G, Bush T, Grothaus L. Assessing the feasibility of using computerized pharmacy refill data to monitor antidepressant treatment on a population basis: a comparison of automated and self-report data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:883–890. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von KM, Lin EH, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1155–1159. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Daniels M, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin EH, VonKorff M, Russo J, Katon W, Simon GE, Unutzer J, et al. Can depression treatment in primary care reduce disability? A stepped care approach. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1052–1058. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IBM SPSS. Version 19.0 [computer program] Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gill D, Hatcher S. A systematic review of the treatment of depression with antidepressant drugs in patients who also have a physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostler K, Thompson C, Kinmonth AL, Peveler RC, Stevens L, Stevens A. Influence of socio-economic deprivation on the prevalence and outcome of depression in primary care: the Hampshire Depression Project. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:12–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanskanen A, Hintikka J, Honkalampi K, Haatainen K, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Viinamaki H. Impact of multiple traumatic experiences on the persistence of depressive symptoms--a population-based study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2004;58:459–464. doi: 10.1080/08039480410011687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon-Slaughter H. Economic factors in of patients' nonadherence to antidepressant treatment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1985–1998. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]