Abstract

Background

Viral myocarditis is a common cause of transient electrocardiogram (EKG) abnormalities in children. The clinical presentation of acute myocarditis ranges from asymptomatic infection to fulminant heart failure and sudden death. Many children present with nonspecific symptoms such as dyspnea or vomiting, frequently leading to misdiagnosis. EKG abnormalities are a sensitive indicator of acute myocarditis and are present in more than 90% of cases.

Case Report

A 13-year-old female suffered a syncopal episode and was found to have high-grade atrioventricular (AV) block caused by acute presumed viral myocarditis. With close monitoring, the EKG abnormalities resolved over the following 48 hours. In this case report, we discuss the incidence, pathogenesis, and outcomes of conduction disturbances in acute myocarditis.

Conclusion

High-degree AV block can occur in patients with acute myocarditis, and higher-degree AV block is correlated with greater myocardial injury. Additionally, severity of pathological changes may reflect the reversibility of AV block. In the majority of cases, however, this rhythm disturbance is transient and does not require permanent pacemaker placement.

Keywords: Adams-Stokes syndrome, atrioventricular block, coxsackievirus infections, myocarditis, syncope

INTRODUCTION

Viral myocarditis is a common cause of transient electrocardiogram (EKG) abnormalities in children.1 The clinical presentation of acute myocarditis ranges from asymptomatic infection to fulminant heart failure and sudden death. Many children present with nonspecific symptoms such as dyspnea or vomiting, frequently leading to misdiagnosis.1-6 EKG abnormalities are a sensitive indicator of acute myocarditis and are present in more than 90% of cases.7 However, high-degree heart block occurs in only 23%-33% of cases.7,8 Although transvenous pacing may be required during the acute stage of infection, most patients recover without the need for definitive pacemaker implantation.9 Infectious myocarditis should be considered when physicians encounter a patient with high-degree heart block.

CASE REPORT

A 13-year-old girl was admitted to the hospital following a syncopal episode. Witnesses reported that she complained of dizziness immediately prior to briefly losing consciousness, but she denied chest pain, palpitations, or dyspnea. Five days prior to the syncopal episode, she developed an influenza-like illness consisting of subjective fevers, emesis, diarrhea, rhinorrhea, and sore throat. She took guaifenesin and pseudoephedrine for symptom relief. She had no history of significant medical illnesses prior to this event and no family history of heart disease or sudden death.

An initial EKG performed in the field showed a high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block with a ventricular rate of 40 bpm. Upon arrival to the emergency department, she was afebrile, her blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, and she had normal heart and respiratory rates along with normal oxygen saturation. She was awake and responsive, and with the exception of nasal congestion, no abnormalities were detected upon complete physical examination.

Laboratory studies were remarkable for a troponin level of 2.64 μg/L, a white blood cell count of 7,400 μL with 48% lymphocytes, mildly elevated aspartate aminotransferase of 53 U/L, and elevated C-reactive protein at 5.3 mg/L. Serum electrolytes and brain natriuretic peptide levels were within normal limits. A chest x-ray showed an appropriate cardiac size and silhouette. Echocardiogram demonstrated a small pericardial effusion but normal anatomy and function. Multiple laboratory studies were ordered, but a causative pathogen was not identified.

The patient was given 2 g/kg intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and closely monitored over the following 48 hours. A temporary pacing catheter was placed as a precautionary measure given the high-degree AV block noted on her initial EKG, but pacing was not required. Serial EKGs over the course of admission demonstrated gradual resolution of the initial conduction abnormalities (Figures 1 and 2). Finally, an episode of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia was noted by telemetry early in her hospital course. Oral amiodarone was administered and tapered over the month following her discharge. Following amiodarone taper, the patient made a full recovery without any recurring cardiovascular symptoms or abnormal electrocardiographic findings (Figure 3).

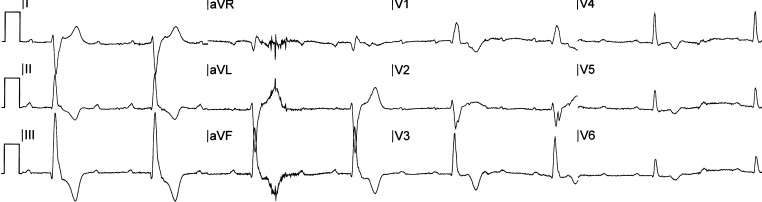

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram of the patient at presentation demonstrating high-degree atrioventricular block.

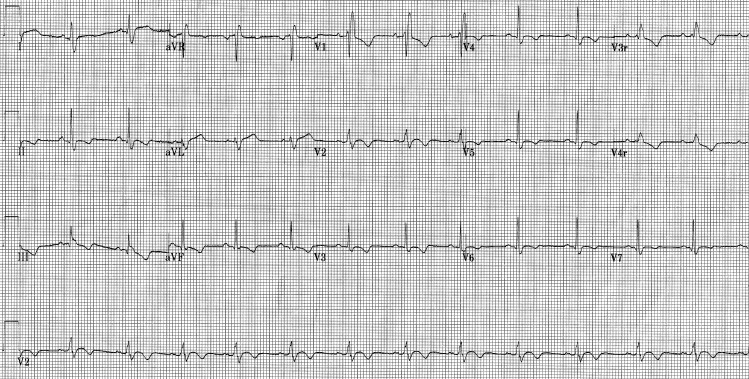

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram of the patient demonstrating the resolution of the atrioventricular block.

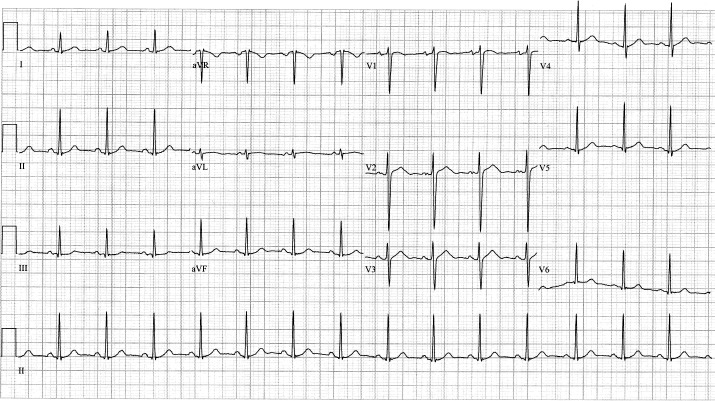

Figure 3.

Electrocardiogram of the patient at follow-up demonstrating normal sinus rhythm.

DISCUSSION

The true incidence of viral myocarditis in children is unknown because of the frequently asymptomatic nature of infection.7 Coxsackie B virus,10,11 adenovirus,11 and parvovirus B1912 are believed to account for the majority of cases, but a causative pathogen is identified in fewer than 10% of cases.5 EKG abnormalities are often early manifestations of acute myocarditis and may carry important clinical and prognostic implications.13 Most EKGs demonstrate nonspecific and usually benign ST and T wave abnormalities, axis deviation, prolonged QRS duration, or premature ventricular contractions.14-16 More serious arrhythmias such as AV conduction block, as seen in our patient, are estimated to occur in fewer than 33% of cases.7,8

The pathogenesis of conduction disturbances is influenced by viral tropism for cardiac myocytes and the inflammatory response of the host.17,18 Viruses replicating within myocytes provoke an adaptive immune response characterized by the influx of natural killer cells and T cells.9 These cells are ultimately responsible for viral clearance, but in the process cause cytokine-mediated cellular damage and edema that result in interruption of the conduction pathways.10,19 Clinically, these conduction disturbances may manifest diversely as AV block, bundle-branch and intraventricular block, or sinus arrest.15,16 Pathological mechanisms for AV block, as seen in this case, are most often attributed to diffuse and severe inflammation in the right and left bundle branches, especially in the terminal portions.20 The severity of pathological changes may reflect the degree and reversibility of AV block.21

High-degree AV block encompasses both second-degree AV block type 2 and third-degree AV block. The former is characterized by a failure of ventricular conduction of P waves without progressive lengthening of the P-R interval, while the latter involves the complete dissociation of P waves and QRS complexes. Low-degree AV block, in contrast, encompasses first-degree AV block and second-degree AV block type 1. First-degree AV block is a prolongation of the P-R interval without missed beats, while second-degree AV block type 1 is a failure of ventricular conduction of P waves with progressive P-R interval lengthening. Delayed conduction from any of these conditions may result in bradycardia that can impair cardiac output enough to cause syncope. This phenomenon, which occurred in our patient, is called Stokes-Adams syndrome.17

The treatment goal for the management of the disease is the maintenance of cardiac output sufficient for adequate tissue perfusion. No known therapy exists to shorten the duration of AV block. Evidence is also lacking to support the use of antiarrhythmics such as amiodarone for ventricular arrhythmia in the setting of conduction delay. Additionally, antiarrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone must be used cautiously in myocarditis, as they may have negative inotropic effects and exacerbate heart failure.14 If no hemodynamic compromise is present, pharmacotherapy may be attempted for supraventricular arrhythmias. Lidocaine infusions should be considered as first-line treatment for ventricular ectopy in children with myocarditis given the known side effect profile of amiodarone.22 Finally, although IVIG was used in the treatment of this patient, recent research suggests that evidence supporting its use in pediatric myocarditis is lacking.23

As might be expected, serious conduction disturbances in acute myocarditis are associated with more severe myocardial necrosis and a poorer prognosis.24,25 However, the overall survival of pediatric patients with acute, nonfulminant myocarditis remains greater than 90%.26 In one study, prolonged QRS duration was an independent predictor for cardiac death or need for heart transplantation.13 In another study, recovery of AV conduction occurred in 67% of children with myocarditis and complete AV block, with an average time to recovery of 3.3 ± 2.8 days, but 27% required permanent pacemakers, as indicated by persistent AV block lasting longer than 1 week.9

CONCLUSION

High-degree AV block can occur in patients with acute myocarditis, and higher-degree AV block is correlated with greater myocardial injury. Additionally, severity of pathological changes may reflect the reversibility of AV block. In the majority of cases, however, this rhythm disturbance is transient and does not require permanent pacemaker placement.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

This article meets the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification competencies for Patient Care and Medical Knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1.Freedman SB, Haladyn JK, Floh A, Kirsh JA, Taylor G, Thull-Freedman J. Pediatric myocarditis: emergency department clinical findings and diagnostic evaluation. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(6):1278–1285. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kibrick S, Benirschke K. Severe generalized disease (encephalohepatomyocarditis) occurring in the newborn period and due to infection with Coxsackie virus, group B; evidence of intrauterine infection with this agent. Pediatrics. 1958 Nov;22(5):857–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner AM. An experimental approach to virus myocarditis. Prog Med Virol. 1965;7:97–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith WG. Adult heart disease due to the Coxsackie virus group B. Br Heart J. 1966 Mar;28(2):204–220. doi: 10.1136/hrt.28.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mason JW, O'Connell JB, Herskowitz A, et al. A clinical trial of immunosuppressive therapy for myocarditis; The Myocarditis Treatment Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1995 Aug 3;333(5):269–275. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P, Martino T, Opavsky MA, Penninger J. Viral myocarditis: balance between viral infection and immune response. Can J Cardiol. 1996 Oct;12(10):935–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman AM, McNamara D. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 9;343(19):1388–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dec GW, Jr, Waldman H, Southern J, Fallon JT, Hutter AM, Jr, Palacios I. Viral myocarditis mimicking acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Jul;20(1):85–89. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batra AS, Epstein D, Silka MJ. The clinical course of acquired complete heart block in children with acute myocarditis. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003 Sep-Oct;24(5):495–497. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esfandiarei M, McManus BM. Molecular biology and pathogenesis of viral myocarditis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:127–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin AB, Webber S, Fricker FJ, et al. Acute myocarditis. Rapid diagnosis by PCR in children. Circulation. 1994 Jul;90(1):330–339. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orth T, Herr W, Spahn T, et al. Human parvovirus B19 infection associated with severe acute perimyocarditis in a 34-year-old man. Eur Heart J. 1997 Mar;18(3):524–525. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ukena C, Mahfoud F, Kindermann I, Kandolf R, Kindermann M, Böhm M. Prognostic electrocardiographic parameters in patients with suspected myocarditis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011 Apr;13(4):398–405. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq229. Epub 2011 Jan 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KJ, McCrindle BW, Bohn DJ, et al. Clinical outcomes of acute myocarditis in childhood. Heart. 1999 Aug;82(2):226–233. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakashima H, Honda Y, Katayama T. Serial electrocardiographic findings in acute myocarditis. Intern Med. 1994 Nov;33(11):659–666. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.33.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chien SJ, Liang CD, Lin IC, Lin YJ, Huang CF. Myocarditis complicated by complete atrioventricular block: nine years' experience in a medical center. Pediatr Neonatol. 2008 Dec;49(6):218–222. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60014-0. Erratum in: Pediatr Neonatol. 2009 Feb;50(1):39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu MH. Myocarditis and complete atrioventricular block: rare, rapid clinical course and favorable prognosis? Pediatr Neonatol. 2008 Dec;49(6):210–212. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(09)60012-7. Erratum in: Pediatr Neonatol. 2009 Feb;50(1):39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yajima T, Knowlton KU. Viral myocarditis: from the perspective of the virus. Circulation. 2009 May 19;119(19):2615–2624. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.766022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aretz HT. Myocarditis: the Dallas criteria. Hum Pathol. 1987 Jun;18(6):619–624. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiwara T, Akiyama Y, Narita H, et al. Idiopathic acute myocarditis with complete atrioventricular block in a baby. Clinicopathological study of the atrioventricular conduction system. Jpn Heart J. 1981 Mar;22(2):275–280. doi: 10.1536/ihj.22.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JN, Tsai YC, Lee WL, Lin CS, Wu JM. Complete atrioventricular block following myocarditis in children. Pediatr Cardiol. 2002 Sep-Oct;23(5):518–521. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-0129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saul JP, Scott WA, Brown S, et al. Intravenous Amiodarone Pediatric Investigators. Intravenous amiodarone for incessant tachyarrhythmias in children: a randomized, double-blind, antiarrhythmic drug trial. Circulation. 2005 Nov 29;112(22):3470–3477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.534149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson J, Hartling L, Vandermeer B, Crumley E, Klassen TP. Intravenous immunoglobulin for presumed viral myocarditis in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004370.pub2. Jan 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichikawa R, Sumitomo N, Komori A, et al. The follow-up evaluation of electrocardiogram and arrhythmias in children with fulminant myocarditis. Circ J. 2011;2011;75(4):932–938. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0918. Epub. Feb 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuura H, Palacios IF, Dec GW, et al. Intraventricular conduction abnormalities in patients with clinically suspected myocarditis are associated with myocardial necrosis. Am Heart J. 1994 May;127(5):1290–1297. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gagliardi MG, Bevilacqua M, Bassano C, et al. Long term follow up of children with myocarditis treated by immunosuppression and of children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2004 Oct;90(10):1167–1171. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.026641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]