Abstract

Dose intensity is important for disease control in patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. We conducted a phase I/II controlled adoptive randomized study to determine the optimal dosing schedule of i.v. busulfan. Patients with advanced hematologic malignancies, ≤ 75 years with HLA-compatible donor were eligible. All patients received fludarabine at 30mg/m2/d for 4 days and busulfan was administered in different doses in oral or i.v. formulations. As determined by the phase I trial, i.v. busulfan at a dose of 11.2 mg/kg/d was utilized for the phase II expansion cohort. Altogether, 80 patients with a median age of 56 years were enrolled. Forty percent had active disease at the time of transplant. Engraftment occurred in 91% and a complete response was achieved in 79% of patients post-transplant. At a median follow up of 91 months in the surviving patients, the outcomes for i.v. busulfan dose of 11.2 mg/kg/d vs. other doses were: non-relapse mortality: 34% vs. 23% (p=0.4); cumulative incidence of relapse: 43% vs. 68% (p=0.02); relapse-free-survival (RFS): 25% vs. 9% (p=0.017); overall-survival (OS): 27% vs. 9% (p=0.02). We conclude that optimizing intravenous busulfan dose intensity in the preparative regimen may overcome disease associated poor prognostic factors.

INTRODUCTION

Reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimen is associated with low non-relapse mortality (NRM) and has made it possible to offer allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT) to the older population. Several large registry studies have shown that the lower NRM seen in RIC comes at the cost of increased relapsed rate1–3. Although myeloablative doses of i.v. busulfan in combination with either fludarabine or cyclophosphamide have been associated with favorable outcomes, significant toxicities and treatment related morbidity and mortality remain a major concern 4–6. Slavin et al first reported the successful combination of oral busulfan with fludarabine, which resulted in 100% engraftment and was associated with long-term disease control in 77.5%7. Since then, i.v. busulfan has largely replaced its oral formulation as part of the preparative due to more predictable pharmacokinetics and ability to perform dose adjustments to avoid excess toxicities4, 6, 8. Bypassing the oral route to achieve 100% bioavailability has translated into improved control over drug administration, with increased safety and reliability in order to maximize the anti-leukemic efficacy. A recent report revealed a promising association with use of the i.v. form of busulfan and a lower NRM, even in sicker or older populations9. However, high-risk disease and/or active disease at the time of transplantation is still associated with poor outcomes10–14. Levine et al have demonstrated poor outcome associated with lower doses of busulfan in conditioning regimen, especially in patients with advanced disease12. In a retrospective analysis of 31 patients, busulfan dose of 8mg/kg was associated with better disease control when compared to a less intense regimen of 4 mg/kg15. However, other studies have not found an advantage with higher dose busulfan containing regimens. Hamadani et al reported (in a retrospective analysis) that there was no difference in the outcomes between RIC busulfan/ fludarabine (6.4mg/kg total dose of busulfan) compared with a more intense regimen (130mg/m2 of busulfan for 4 days-roughly equivalent to 12.8mg/kg cumulative dose)16. However, there were major differences in the patient profiles of two study arms with more acute leukemias in the intense therapy arm and more indolent diseases like chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the less intense arm. Therefore, optimization of busulfan containing conditioning regimens is needed for improvement clinically relevant patient outcomes.

We conducted a prospective phase I/II Bayesian adoptively randomized study to determine the best dose, dosing schedule and efficacy of i.v. busulfan in combination with fludarabine as a preparative regimen for AlloSCT.

Patients and Methods

Patients under 75 years of age undergoing AlloSCT from HLA A, B and DR matched unrelated donors or ≥ 5/6 matched related donors with the following diagnoses were eligible: chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), that was either transformed or Interferon-resistant; acute myeloid leukemia (AML); intermediate or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) as defined by the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS); lymphoma or myeloma beyond 1st remission. Eligible patients were considered unqualified to undergo ablative preparative regimen because of advanced age or the presence of co-morbidities. Patients had to be in Zubrod Performance status (PS) ≤ 2 with adequate hepatic (bilirubin <3mg/dL), and renal (creatinine <2.5mg/dL) function. The goal was to identify the optimal dose and schedule of i.v. busulfan in combination with a fixed dose of fludarabine as a RIC regimen. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas-MD Anderson Cancer Center. Informed consent was obtained from the patients and donors. Unrelated donors were consented according to the National Marrow Donor Registry Policies. Graft vs. host disease (GVHD) assessment was performed according to the consensus criteria 17. Toxicities were assessed according to the NCI common toxicity criteria (NCI CTC version 3, http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html).

Treatment plan

Fludarabine was administered at a dose of 30mg/m2/day prior to busulfan on days -5, -4, -3 and -2 to all patients. Equine anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG 10mg/kg/d ×4, on days -4, -3, -2, and -1) was added for patients receiving mismatched related (MMR) or matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplants. In the phase 1 portion of the study, 7 dose levels of busulfan were explored, with each level being delivered either once a day (m1) or every 6 hour (m2) infusions (Table 1A). Drugs were dosed according to adjusted body weight in patients whose actual weight ≥ 120% of the ideal body weight. Actual weight was used for the rest of the patients. At the time of performing this trial, the resources for performing busulfan pharmacokinetics were not available.

Table 1A.

IV BUSULFAN Dosing schedule:

Seven dose levels of IV Busulfan were administered either as a daily dose or divided into 4 doses (QID). All patients received IV Fludarabine. All unrelated donor transplant recipients received ATG.

| Dose level 0 | Dose level 1 | Dose level 2 | Dose level 3 | Dose level 4 | Dose level 5 | Dose level 6 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAY | Flu mg/m2 |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

BU QID mg/kg |

BU daily mg/kg |

| -5 | 30 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 |

| -4 | 30 | 0.8×2 | 1.6 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | ||

| -3 | 30 | 0.8×2 | 1.6 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | ||||||

| -2 | 30 | 0.8×2 | 1.6 | 0.8×4 | 3.2 | ||||||||||

| -1 | REST | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | SCT infusion | ||||||||||||||

Supportive Care

Patients received GVHD prophylaxis using tacrolimus targeting a blood level of 5–15 ng/ml and methotrexate (5mg/m2 days 1, 3, 6 and 11). Patients were allowed to be on any active GVHD prophylaxis protocols. Infectious disease prophylaxis generally included fluconazole, acyclovir, and ciprofloxacin. Ganciclovir was used on a pre-emptive basis for patients with cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia or viremia which was monitored on a weekly basis. Patients received G-CSF 5mcg/kg subcutaneously daily from Day+7 onwards until achievement of an absolute neutrophil count of >1.5 × 109/L for three days. Filtered and irradiated blood product transfusions were given to maintain hemoglobin >8g/dL and platelets >20,000/cmm3.

Statistical design and analysis

This was a phase I/II Bayesian adoptively randomized dose finding study that took into account both toxicity and efficacy. Patients were evaluated based on age, organ function and donor-match.

Study End Points

The major end points assessed during the study were engraftment (defined as absolute neutrophil count >0.5× 109 /L, for 3 days in a row), platelet recovery (platelet recovery >20 × 109/L, independent of platelet transfusions), infectious complications, achievement of complete remission (CR) (<5% blasts in the bone marrow with trilineage differentiation and freedom from platelet transfusion and ANC >0.5 ×109/L), development and grade of acute GVHD, chimerism over time, and toxicity. Overall Survival (OS) time was calculated as the time from the date of transplant to the date of death or censored at the date of last follow-up. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) 100 was defined as the binary indicator of death within the first 100 days without relapse. Relapse free survival (RFS) time was calculated as the time from the transplant date to the date of disease relapse or death, whichever was earlier. Patients who were alive without relapse at end of the study were censored at the date of last follow-up. There were four covariates of interest: age, cytogenetic risk category (good, intermediate, or bad), dose of busulfan received and the percent of bone marrow blasts.

Dose Finding Strategy

Based on factors influencing toxicity occurring from the preparative regimen; including patient age, organ function and degree of donor match; patients were separated into two strata in consideration for the toxicity for phase I endpoints: “good” risk as defined by good organ function, age <60 years for patients with sibling matched donors and age <50 years for MUD and “poor” risk group as defined by all other patients who met the eligibility criteria: As described earlier, 2 delivery modes m1 (daily dose) and m2 (every 6 hour dosing) were examined. Within each mode, a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was determined among different intravenous busulfan dose levels using the continual reassessment method (CRM18, 19) with a probability 20% for grade 3–4 organ toxicity.

Phase II portion of the study

Phase II was conducted using the MTD selected in phase I with the aim to keep the failure rate below the historical rate of 0.05 and reduce the death rate by 0.20 using the monitoring method described by Thall, Simon and Estey 20.

Statistical Methods

The CRM 18, 19, as described above, was used for dose-finding on phase I. The method of Thall, Simon and Estey 20 was used for safety monitoring in phase II. Bayesian regression models21 were fit to assess the effects of the covariates of interest on the following outcome measurements: OS, RFS, and NRM at 100 days (NRM100). For the time-to-event outcomes (OS and RFS), goodness of fit tests were performed using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)22 to choose the best fitting model from among the Weibull, normal, log normal, logistic, log logistic, exponential, and gamma distributions. For the dichotomous outcome NRM100, Bayesian logistic regression models were fit. For each model fit, we assumed that each parameter in the linear term followed a non-informative normal prior with mean 0 and variance 10. All calculations were performed in R version 2.12.0 and OpenBUGS version 3.1.2 rev 668. The cumulative incidence of relapse and NRM were analysed in a competing risks framework23 and distributions were compared using methodology of Fine and Gray24.

Results

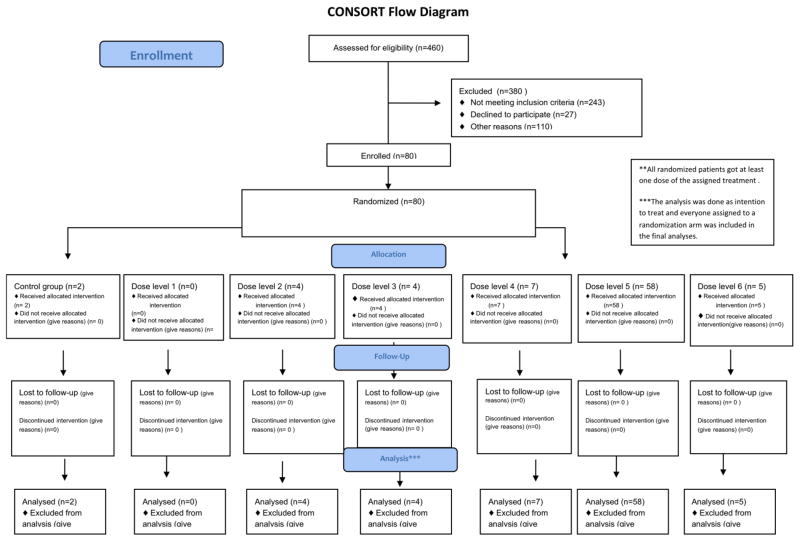

Eighty patients with median age of 56 years (range, 10–71 years) and active disease in 32 (40%) patients were enrolled in the study from March 2000 till October 2004. (Enrollment diagram, Table 1B). Median follow up for survivors was 91 months (25.5–125.7 months). Patient characteristics are described in table 2. Forty patients had a matched related donor and 35 patients had mismatched related or unrelated donor as a source of stem cells for the alloSCT. Five patients (mismatch related donor=1; MUD =4) received fludarabine, busulfan and alemtuzumab (12%). Forty two patients received peripheral blood (PB) progenitor cells and 38 received bone marrow (BM) transplants. The median number of infused CD34+ cells was 4.7 × 106/kg and the median TNC infused was 4.1×108 cells/kg. GVHD prophylaxis was tacrolimus and methotrexate in 69 (87%) patients, tacrolimus alone in 3 while 1 patient received additional extracorporeal photopheresis, and 7 received additional pentostatin25 Six cohorts of two patients each (n=2) were treated with each of the 2 modalities of schedule m1 or m2, for a total of 12 patients per modality and 24 patients overall.

Table 1B.

Enrollment Diagram

|

Table 2A.

Patient characteristics

| Dose level 0 (N=2) | Dose level 2 (N=4) | Dose level 3 (N=4) | Dose level 4 (N=7) | Dose level 5 (N=58) | Dose level 6 (N=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Busulfan Dose freq | ||||||

| Daily dose | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 54 | 3 |

| QID dose | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Age ≥ 60 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Median age at SCT | 54 | 63 | 61 | 44 | 57 | 39 |

|

| ||||||

| Gender, Male | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| AML/MDS | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 46 | 4 |

| CML | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| Othersa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Abnormal cytogenetics | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 36 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Disease status at SCT | ||||||

| CR | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 34 | 3 |

| Refractory/progressive | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 24 | 2 |

| BM Blasts >5% | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 27 | 4 |

|

| ||||||

| Type of Transplant | ||||||

| MUD | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 25 | 2 |

| MRDb | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 33 | 3 |

|

| ||||||

| Stem Cell source | ||||||

| BM | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 26 | 3 |

| PB | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 32 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| TNC (e8/kg) | 4.9 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 2.7 |

|

| ||||||

| CD34 (e6/kg) | 5.4 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 5.5 |

|

| ||||||

| CD3 (e6/kg) | 166.7 | 29.7 | 24.5 | 87.8 | 74.2 | 28 |

. Lymphoma=3, ALL=1;

7/47 had 1 antigen mismatch

QID: 4 times daily; SCT: stem cell transplant; AML: acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; CML: chronic myelogenous leukemia; CR: complete remission; BM: bone marrow; MUD: matched unrelated donor; MRD: matched related donor; PB: peripheral blood; TNC: total nucleated count

Good Risk Cohort (n=31)

Three dose levels of i.v. busulfan were examined in this cohort: 9.6 mg/kg, 11.2 mg/kg, and 12.8 mg/kg. The starting dose was chosen based on our experience and the published literature at the time of the study7.

Poor Risk Cohort (n=49)

Four dose levels on i.v. busulfan were examined in this cohort 8.0 mg/kg, 9.6mg/kg, 11.2mg/kg, and 12.8mg/kg.

The patient characteristics and their distribution is shown in table 2A. The MTD established from the phase I study for both good and high risk cohorts was i.v. busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg. After the completion of enrolment of 32 patients in the phase I portion, the subsequent 48 patients were enrolled into the phase II part of the study on i.v. busulfan dose level 11.2 mg/kg (dose level 5). Since the majority (73%) of patients in the trial received the dose level 5, this dose was re-coded as a dichotomous variable: dose level 5 vs. all other doses combined (Table 2B) for outcome analysis. All patients were included in the final planned analysis.

Table 2B.

Patient characteristics: dose level 5 vs others

| Dose level 5 (N=58) | Others (N=22) | P VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Busulfan Dose freq | 0.001 | ||

| Daily dose | 54 (93%) | 13 (59%) | |

| QID dose | 4 (7%) | 9 (41%) | |

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 60 | 23 (40%) | 7 (32%) | 0.6 |

|

| |||

| Median age at SCT | 57 | 54 | NS |

|

| |||

| Gender, Male | 37 (64%) | 17 (77%) | |

|

| |||

| Diagnosis | |||

| AML/MDS | 43 (74%) | 17 (77%) | |

| CML | 11 (19%) | 5 (23%) | |

| Othersa | 4 (7%) | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Abnormal cytogenetics | 36 (62%) | 14 (64%) | 0.7 |

|

| |||

| Relapsed/Refractory disease at time of SCT | 23 (38%) | 9 (41%) | 0.15 |

|

| |||

| Type of Transplant | 1.0 | ||

| MUD | 25 (43%) | 9 (41%) | |

| MRDb | 33 (57%) | 13 (59%) | |

|

| |||

| Stem Cell source | 0.463 | ||

| BM | 26 (45%) | 12 (55%) | |

| PB | 32 (55%) | 10 (45%) | |

|

| |||

| TNC (e8/kg) | 4.6 | 3.4 | |

|

| |||

| CD34 (e6/kg) | 4.75 | 5 | |

|

| |||

| CD3 (e6/kg) | 74.3 | 32 | |

. Lymphoma=3, ALL=1;

7/47 had 1 antigen mismatch

QID: 4 times daily; SCT: stem cell transplant; AML: acute myelogenous leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; CML: chronic myelogenous leukemia; CR: complete remission; BM: bone marrow; MUD: matched unrelated donor; MRD: matched related donor; PB: peripheral blood; TNC: total nucleated count

Toxicity

The most common (≥ 20%) adverse events of any grade, regardless of the relationship to the preparative regimen were increased creatinine (33.7%), diarrhea (35%), infection (32.5%), mucositis (51%), nausea (57.5%), skin rash (37.5%) and transaminitis (35%). Regimen-related grade 3 or higher toxicity included bleeding (2.5%), diarrhea (2.5%), increased bilirubin (2.5%), hematuria (1.2%), high blood pressure (1.2%), mucositis (1.2%), neutropenia (1.2%), skin rash (1.2%). One patient developed Veno-occlusive disease (VOD) at 67 days post-transplant and was associated with altered mental status, hepatic encephalopathy, raised transaminitis. Liver biopsy showed mild increase in periportal fibrosis with no evidence of cirrhosis and severely increased iron deposition. Patient was subsequently found to have severe iron overload and improved with phlebotomy. Ultimately, the patient died of steroid-refractory GVHD. Overall 57% had documented infections. Isolated organisms included: alpha-hemolytic streptococci (1), BK virus (2), C-difficile (1), CMV reactivation (6), Coagulase negative staphylococcus (4), E. Coli (1), Klebsiella (1), Parainfluenza (1), pseudomonas aeruginosa (7), rhizopus (1), vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (3). One patient had west nile virus encephalitis.

Engraftment, chimerism and GVHD

Engraftment occurred in 73 patients (91%). No differences were seen in the engraftment rate between i.v. busulfan dose level 11.2 mg/kg and other groups (91.4% vs. 91%, respectively; p=NS). There were 3 early deaths and four graft failures. There was signnificant correlation between graft failure and persistent disease in the post transplant setting (chi square, p<0.0001). Among those who engrafted, 37 (50%) had full donor chimerism. Routinely performed chimerism studies revealed the development of mixed chimerism (< 99% donor cells detected in peripheral blood on more than 1 occasion) in 32 patients. Among these patients, >90% donor chimerism was seen in 12 patients (38%). The median degree of chimerism in these patients was 86.5% (12%–98%) and a was significant correlation was demonstrated between the incidence of mixed chimerism and persistent disease in the post-transplant setting (chi square, p<0.0001). The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 13 days and to platelet engraftment was 17 days. The engraftment data for the whole cohort is shown in table 3A. There were no differences in the dose level 5 vs. others in terms of graft failure, time to neutrophil engraftment days or time to platelet engraftment (Table 3B).

Table 3A.

Transplant outcomes in the whole cohort

| Dose level 0 (N=2) | Dose level 2 (N=4) | Dose level 3 (N=4) | Dose level 4 (N=7) | Dose level 5 (N=58) | Dose level 6 (N=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft Failure | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Time to Neutrophil Engraftment,(days) | 13 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 13 |

| Time to platelet Engraftement, (days) | 8 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 15 | 18 |

| Grade 2–4 aGVHD | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 2 |

| Grade 3–4 aGVHD | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| Time to aGVHD, days | - | 34.5 | 48 | 26 | 46 | 35.5 |

| Chronic GVHD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 1 |

| Time to cGVHD, mos | - | - | - | 4.3 | 7.1 | 4.3 |

| Progression, n | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 26 | 4 |

| Median time to progression, days | 70 | 26 | 25.5 | 54 | 64.5 | 81 |

| Dead, n | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 43 | 5 |

| Dead at 100days without relapse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Dead at 1year without relapse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 0 |

| Median time to death, days | 167 | 48 | 65 | 165 | 157 | 258 |

Table 3B.

Transplant Outcomes Dose Level 5 vs. Others

| Dose Level 5 (N=58) | Other dose levels (N=22) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graft Failure | 2 | 2 | NS |

| Time to Neutrophil Engraftment,(days) | 13 | 13 | NS |

| Time to platelet Engraftment, (days) | 15 | 18 | NS |

| Grade 2–4 aGVHD | 17 (29.3%) | 9 (42%) | NS |

| Chronic GVHD | 19 (32.8%) | 4 (13.6%) | 0.087 |

| Progression, n | 25 (43%) | 15 (68%) | 0.045 |

| Dead, n | 43 (74%) | 20 (91%) | 0.1 |

Among the engrafted patients, grade 2–4 aGVHD occurred in 26 patients (35.6%) and grade 3–4 aGVHD occurred in 8 patients (11%). The median time to onset of acute GVHD was 43.5 days (13–208 days). The distribution of the aGVHD was primarily to the skin (n=34) followed by GI tract (n=10) and liver (n=2). The aGVHD distribution for the whole cohort is shown in table 3A. There were no differences in the aGVHD rates between dose level 5 vs. others (Table 3). Chronic GVHD occurred in 22 patients (27.5%) involving skin (n=11), GI tract (n=7), liver (n=3) and eyes (n=2). Again, no significant differences were seen between dose level 5 patients vs. others.

Non-Relapse Mortality (NRM)

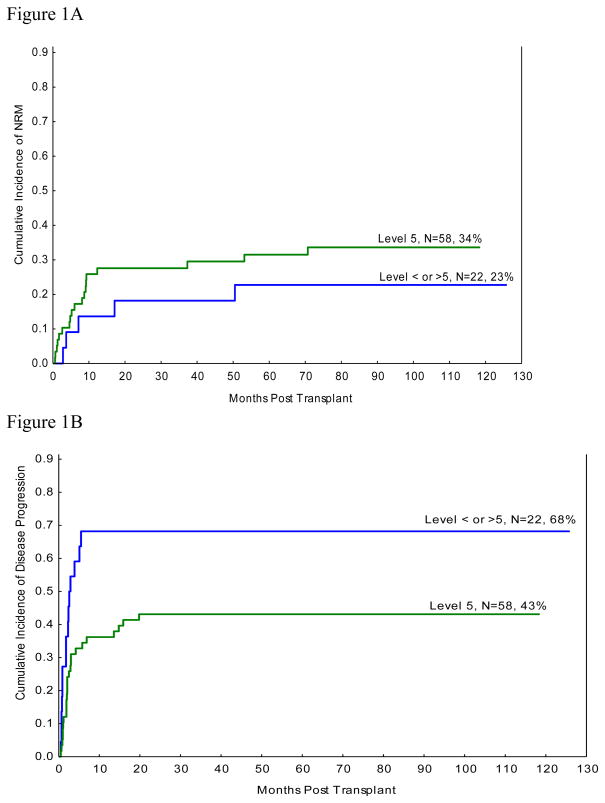

Table 4 demonstrates the results of multivariate analysis of NRM100. Advanced age at the time of transplant was the only significant factor predicting worse outcome. NRM100 was 10% for the whole cohort (due to infections=3, aGVHD=2, graft failures=2, alveolar haemorrhage=1). The 1-year NRM was 23.8% (due to GVHD=10, Infection=4, Graft Failure=2, Haemorrhage=2, Unknown=1). At 8 year follow up, no significant difference was seen for NRM of 34% for i.v. busulfan dose level 11.2 mg/kg and 23% seen in all others (p=0.4, figure 1A)

Table 4.

Summary of Bayesian Logistic Regression Model for TRM by Day 100, RFS and OS

| Day-100 NRM | RFS | OS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Pr (Harmful Effect) | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Pr (Beneficial Effect) | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Pr (Beneficial Effect) |

| Intercept | −3.042 | 0.918 | −1.033 | 0.359 | −0.637 | 0.327 | ||||||

| Age | 0.126 | 0.062 | 0.021, 0.265 | 0.992 | −0.012 | 0.015 | −0.042, 0.017 | 0.198 | −0.025 | 0.014 | −0.052, 0.017 | 0.035 |

| Cytogenetics Bad (vs. Intermediate) | 0.739 | 0.872 | −1.055, 2.388 | 0.812 | −0.924 | 0.401 | −1.722, −0.143 | 0.011 | −0.667 | 0.370 | −1.380, 0.063 | 0.035 |

| Cytogenetics Good (vs. Intermediate) | −1.845 | 2.292 | −6.560, 2.022 | 0.221 | 1.234 | 0.726 | −0.214, 2.678 | 0.954 | 1.105 | 0.662 | −0.185, 2.406 | 0.953 |

| Cytogenetics Unknown (vs. Intermediate) | 0.471 | 1.398 | −2.541, 2.916 | 0.662 | −0.330 | 0.645 | −1.585, 0.917 | 0.307 | −0.326 | 0.592 | −1.474, 0.825 | 0.293 |

| Log (Number of Blasts) | −0.138 | 0.215 | −0.550, 0.283 | 0.252 | −0.173 | 0.091 | −0.348, 0.005 | 0.027 | −0.113 | 0.084 | −0.274, 0.057 | 0.092 |

| Dose level 5 (vs. all other levels) | −0.361 | 0.907 | −2.127, 1.471 | 0.337 | 0.801 | 0.412 | −0.014, 1.608 | 0.973 | 0.761 | 0.378 | 0.015, 1.487 | 0.977 |

NRM: non relapse mortality; RFS: relapse free survival; OS: overall survival

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: Cumulative Incidence of NRM with competing risk of relapse

Figure 1B: Cumulative Incidence of Relapse

Relapse and Survival

The 8-year cumulative incidence of relapse of 43% was significantly less in the patients receiving busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg as compared to 68% relapse seen in other dose levels (p=0.02, figure 1B). In multivariate analysis, RFS was superior for patients receiving i.v. busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg (table 4). The 5 year RFS was 25% for dose level 5 patients vs. 9% for all others (p=0.017; Figure 1B). Disease related poor prognostic factors including bad cytogenetics and increased bone marrow blasts were also associated with worse RFS.

At a median follow up of 91 months in the surviving patients, the five year OS for patients treated with iv. Busulfan 11.2 mg/kg dose level was 27% compared to 9 for patients treated at the other dose levels (p=0.02; figure 2B). In multivariate analysis, improved OS was seen in dose level 5 patients (table 4). Older age, unfavorable cytogenetics, and increased bone marrow blasts were also associated with worse OS (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Figure 2A: Overall Survival

Figure 2B: Relapse Free Survival

Since indication for AlloSCT was AML/MDS in 75% of the patients in our study, we specifically studied outcomes in this population. The 5-year OS for the whole cohort was 18%. Significant improvement in OS was seen in patients receiving i.v. busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg dose when compared to others: 23% vs. 5% (p=0.019). The causes of deaths for the whole cohort were progressive disease in 39 (48.8%), GVHD in 12 (15%), infection in 5 (6.3%), graft rejection in 2 (2.5%), haemorrhage in 2 (2.5%), myocardial infarction in 1, and unknown in 2.

Potential candidates for high dose busulfan: Impact of transplant risk factors

Among the patients receiving i.v. busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg, we sought to examine whether the transplant prognostic risk factors would affect the overall outcomes. In this category, significantly improved median overall survival of 12.3 months was observed in the patients with good prognostic risk factors vs. 6.3 months seen in the patients with poor risk factors. (p=0.04; log rank). Similarly, a trend towards improved RFS of 9.4 months was seen in the patients with good prognostic risk factors compared to 4.6 months in patients with poor prognostic risk factors (p=0.08, log rank).

QID vs. Daily dosing

No significant differences were seen in terms of mortality, overall survival or PFS when comparing daily dose vs. four time daily dose of Busulfan.

Discussion

We report the results of a phase I/II study of i.v. busulfan containing reduced intensity preparative regimen, without pharmacokinetic monitoring, for older or medically infirm patients with advanced hematologic malignancies, not otherwise considered eligible for myeloablative conditioning. This trial further validated a set of favourable transplant risk factors (independent of the disease status) that include: i) good organ function, ii) age <60 years for sibling matched donor transplant and iii) age <50 years for MUD transplant that are associated with improved outcomes with a 5-year OS of 40% and RFS of 36%.

A large proportion of our study population were older than 60 years of age (38%) and harbored high risk. As shown previously, a similar patient population with active disease at the time of transplant are unlikely to achieve durable remissions and are associated with poor outcomes26, 27. However, in our study, remission was achieved in 63 patients (79%) after the transplant in the whole cohort and in 84% for those receiving busulfan at 11.2 mg/kg. Specifically, improved survival was associated with i.v. busulfan 11.2 mg/kg dose among patients with diagnosis of AML/MDS, which is a hard to treat population. Furthermore, improved relapse rates of 43% were associated with the i.v. busulfan dose intensification but not at the cost of toxicity. In fact NRM rates exceeding 40% have been reported in a younger population as compared to our patients, with relatively less advanced disease but a comorbidity index of ≥ 328, whereas in our study, the NRM was 31% for the whole cohort. Even though a majority of the patients were heavily pre-treated, we did not see any increase in liver toxicity and specifically, only one patient developed VOD. As expected, increased bone marrow blasts and poor cytogenetics still remained as poor predictors of outcome and novel post-transplant therapies including demethylating agents continue to be explored as a post-transplant strategy29, 30.

In our study, the engrafted patients demonstrated mixed chimerism in 44% patients. This is not surprising since mixed chimerism rates of upto 65% have been shown in the setting of RIC using busulfan/fludarabine combination31. In addition, we used strict criteria of <99% donor chimerism to define as mixed chimerism. Furthermore, the incidence of mixed chimerism correlated with the persistent disease in the post transplant seeting (chi square, p<0.0001).

In conclusion, optimizing the busulfan dose in the preparative RIC regimen, led to improvement of the anti-tumor activity of conditioning without significant regimen toxicity, which led to decreased relapse and improved survival. Specifically, we did not experience increased toxicity with higher busulfan doses up to 11.2 mg/kg, even in the absence of the guidance provided by the pharmacokinetic monitoring of busulfan. Therefore, in areas where busulfan monitoring is difficult, adopting the dose level of 11.2mg/kg may seem to be a reasonable option for the elderly, medically infirm patients with high risk disease..

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Simrit Parmar: wrote the manuscript, collected and analyzed data

Gabriella Rondon: collected and analyzed data ; approved and reviewed final manuscript

Marcos de Lima: collected and analyzed data and approved final manuscript

Paolo Anderlini: participated in the trial enrollment, approved and reviewed final manuscript

Issa Khouri: participated in the trial enrollment, approved and reviewed final manuscript

Partow Kebriaei: participated in the trial enrollment, approved and reviewed final manuscript

Peter Thall: Designed the statistical design of the study and performed statistical analysis

Prasanth Ganesan: collected and analyzed data; approved and reviewed final manuscript

Roland Bassett: performed statistical analysis

Richard E. Champlin: approved and reviewed final manuscript; developed the project

Sergio Giralt: approved and reviewed final manuscript; developed the project and referred patients to most studies analyzed here

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

The authors report no relevant financial conflict of interest

References

- 1.Aoudjhane M, Labopin M, Gorin NC, Shimoni A, Ruutu T, Kolb HJ, et al. Comparative outcome of reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning regimen in HLA identical sibling allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age with acute myeloblastic leukaemia: a retrospective survey from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Leukemia. 2005;19(12):2304–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger SM, Ringden O, Zhang MJ, Perez WS, Bishop MR, Bornhauser M, et al. Similar outcomes using myeloablative vs reduced-intensity allogeneic transplant preparative regimens for AML or MDS. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(2):203–11. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringden O, Labopin M, Ehninger G, Niederwieser D, Olsson R, Basara N, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning compared with myeloablative conditioning using unrelated donor transplants in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4570–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lima M, Couriel D, Thall PF, Wang X, Madden T, Jones R, et al. Once-daily intravenous busulfan and fludarabine: clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a myeloablative, reduced-toxicity conditioning regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in AML and MDS. Blood. 2004;104(3):857–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallen H, Gooley TA, Deeg HJ, Pagel JM, Press OW, Appelbaum FR, et al. Ablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults 60 years of age and older. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3439–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson BS, Kashyap A, Gian V, Wingard JR, Fernandez H, Cagnoni PJ, et al. Conditioning therapy with intravenous busulfan and cyclophosphamide (IV BuCy2) for hematologic malignancies prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a phase II study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(3):145–54. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm11939604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91(3):756–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashyap A, Wingard J, Cagnoni P, Roy J, Tarantolo S, Hu W, et al. Intravenous versus oral busulfan as part of a busulfan/cyclophosphamide preparative regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: decreased incidence of hepatic venoocclusive disease (HVOD), HVOD-related mortality, and overall 100-day mortality. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2002;8(9):493–500. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12374454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alatrash G, de Lima M, Hamerschlak N, Pelosini M, Wang X, Xiao L, et al. Myeloablative reduced-toxicity i.v. busulfan-fludarabine and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome in the sixth through eighth decades of life. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(10):1490–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lima M, Anagnostopoulos A, Munsell M, Shahjahan M, Ueno N, Ippoliti C, et al. Nonablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning regimens in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: dose is relevant for long-term disease control after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104(3):865–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martino R, Iacobelli S, Brand R, Jansen T, van Biezen A, Finke J, et al. Retrospective comparison of reduced-intensity conditioning and conventional high-dose conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using HLA-identical sibling donors in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2006;108(3):836–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine JE, Uberti JP, Ayash L, Reynolds C, Ferrara JL, Silver SM, et al. Lowered-intensity preparative regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation delays acute graft-versus-host disease but does not improve outcome for advanced hematologic malignancy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9(3):189–97. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alyea EP, Kim HT, Ho V, Cutler C, Gribben J, DeAngelo DJ, et al. Comparative outcome of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age. Blood. 2005;105(4):1810–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimoni A, Hardan I, Shem-Tov N, Yeshurun M, Yerushalmi R, Avigdor A, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in AML and MDS using myeloablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning: the role of dose intensity. Leukemia. 2006;20(2):322–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cahu X, Mohty M, Faucher C, Chevalier P, Vey N, El-Cheikh J, et al. Outcome after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT for AML in first complete remission: comparison of two regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(10):689–91. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamadani M, Mohty M, Kharfan-Dabaja MA. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Control. 2011;18(4):237–45. doi: 10.1177/107327481101800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Quigley J, Pepe M, Fisher L. Continual reassessment method: a practical design for phase 1 clinical trials in cancer. Biometrics. 1990;46(1):33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman SN, Zahurak ML, Piantadosi S. Some practical improvements in the continual reassessment method for phase I studies. Stat Med. 1995;14(11):1149–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thall PF, Simon RM, Estey EH. New statistical strategy for monitoring safety and efficacy in single-arm clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):296–303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelman ACJ, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarz Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV, Jr, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34(4):541–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.RJFJaG A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. JASA. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parmar S, Andersson BS, Couriel D, Munsell MF, Fernandez-Vina M, Jones RB, et al. Prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease in unrelated donor transplantation with pentostatin, tacrolimus, and mini-methotrexate: a phase I/II controlled, adaptively randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(3):294–302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leopold LH, Willemze R. The treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse: a comprehensive review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(9):1715–27. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000006529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giles F, O’Brien S, Cortes J, Verstovsek S, Bueso-Ramos C, Shan J, et al. Outcome of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia after second salvage therapy. Cancer. 2005;104(3):547–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106(8):2912–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Lima M, Giralt S, Thall PF, de Padua Silva L, Jones RB, Komanduri K, et al. Maintenance therapy with low-dose azacitidine after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for recurrent acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome: a dose and schedule finding study. Cancer. 2010;116(23):5420–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabbour E, Giralt S, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Jagasia M, Kebriaei P, et al. Low-dose azacitidine after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute leukemia. Cancer. 2009;115(9):1899–905. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marsh RA, Vaughn G, Kim MO, Li D, Jodele S, Joshi S, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning significantly improves survival of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;116(26):5824–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-282392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]