Abstract

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of luciferase reporters provides a cost-effective and sensitive means to image biological processes. However, transport of luciferase substrates across the cell membrane does affect BLI-readout-intensity from intact living cells.

To investigate the effect of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters on BLI readout, we generated Click Beetle-(cLuc), Firefly-(fLuc), Renilla-(rLuc), and Gaussia-(gLuc) luciferase HEK-293 reporter cells that overexpressed different ABC-transporters (ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2). In vitro studies showed a significant BLI intensity decrease in intact-cells compared to cell-lysates, when ABCG2 was overexpressed in HEK-293/cLuc, fLuc, and rLuc cells. Selective ABC-transporter inhibitors were also applied. Inhibition of ABCG2 activity increased the BLI intensity >2-fold in HEK-293/cLuc, fLuc and rLuc cells; inhibition of ABCB1 elevated the BLI intensity 2-fold only in HEK-293/rLuc cells. BLI of xenografts derived from HEK-293/ABC-transporter/luciferase-reporter cells confirmed the results of inhibitor treatment in vivo.

These findings demonstrate that coelenterazine-based rLuc-BLI intensity can be modulated by ABCB1 and ABCG2. ABCG2 modulates D-luciferin-based BLI in a luciferase-type-independent manner. Little ABC-transporter effect on gLuc-BLI intensity is observed since a large fraction of gLuc is secreted. The expression level of ABC-transporters is one key factor affecting BLI intensity, and this may be particularly important in luciferase-based applications in stem cell research.

Keywords: ABC transporters, Bioluminescence imaging, Coelenterazine, D-luciferin, Stem cells

Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are one of the largest families of active transport molecules.1 There are 48 ABC genes in the human genome and they are dispersed mostly on different chromosomes.2 The functional protein typically contains two nucleotide-binding folds and two transmembrane domains. The transporters can be grouped into seven subfamilies (A–G) based on the conservation of amino acid sequence in nucleotide-binding folds. ATP binding and hydrolysis provide an energy-requiring mechanism for ABC-transporters to efflux specific compounds across the membrane, or to flip them from the inner to the outer leaf of the membranes.1,3,4 ABC-transporters can serve a wide variety of cellular roles. They regulate local transport across the blood-brain, blood-cerebrospinal fluid, blood-testis barriers and the placenta.5 In the liver, gastrointestinal tract and kidney, ABC-transporters protect the organism through the excretion of toxins.6 ABC-transporters also play an active role in the immune system by transporting peptides into the endoplasmic reticulum that are identified as antigens by the class I HLA molecules.7,8 Furthermore, they play physiological roles in cellular lipid transport and homeostasis.9 From a clinical perspective, multidrug resistance (MDR) involves increased expression of members of the ABC-transporter family. The most extensively characterized MDR genes include ABCB1 (also known as MDR1 or P-glycoprotein), ABCC1 (also known as MRP1) and ABCG2 (also known as BCRP or MXR).10 ABC-transporter inhibition remains an attractive potential adjuvant to drug resistance in chemotherapy.11,12 ABC transporters have emerged as an important new field of investigation in the regulation of stem cell (SC) biology. For example, the ‘side population’ phenotype in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis profiles can be identified on the basis of ABC-transporter expression, and used as an important marker in the analysis and isolation of SCs.13

Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) exploits the emission of visible photons at specific wavelengths based on energy-dependent reactions catalyzed by luciferases. Luciferases comprise a family of proteins that emit detectable photons during an enzymatic reaction with specific substrates in the presence of oxygen. Luciferases from the Firefly Photinus pyralis (fLuc) and Click Beetle (cLuc) catalyzes the conversion of luciferin to oxyluciferin and simultaneously produces CO2, phosphate and light.14,15 The Renilla luciferase (rLuc) and Gaussia luciferase (gLuc) genes were cloned from renilla reniformis, the sea pansy, and gaussia princeps, the marine copepod, respectively. Both use coelenterazine as a substrate, which is converted to coelenteramide, CO2, and light. In contrast to fLuc and cLuc, rLuc and gLuc do not require ATP to metabolize coelenterazine.16,17 BLI has been widely used as a noninvasive method to evaluate gene expression, signal transduction, protein-protein interaction, receptor activation, and several molecular events.18 BLI as well as fluorescence imaging is simpler, less expensive, more convenient, and more user friendly than other imaging modalities. Compared with fluorescence imaging, BLI is independent of an activation light source and has much higher sensitivity and lower background, but requires substrate delivery.19

The effects of ABC-transporters on the efflux of established imaging agents (radiotracers for nuclear imaging and substrates for BLI) have been reported recently. For example, retention of the radiotracers 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-PTSM in human and murine tumors is influenced by ABCB1 expression.20 Two papers also reported that ABC-transporters modulated BLI readout through efflux of its substrates, coelenterazine (ABCB1) and D-luciferin (ABCG2).21,22 To investigate whether the BLI intensity alteration is enzyme (luciferase)-dependent as well as substrate-dependent, four luciferases (cLuc, fLuc, rLuc and gLuc), were studied and compared with respect to the effects of ABC-transporters on BLI readout. Both in vitro and in vivo data indicate that ABCG2 affects BLI signal intensity generated from coelenterazine and D-luciferin, and that ABCB1 affects coelenterazine (but not D-luciferin) signal intensity.

In addition, we initiated a comparative study of ABC-transporter expression and BLI in a mouse embryonic stem cell (ESC) line (mES-J1) and a mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line (NIH/3T3). We showed significant differences in the levels of ABC-transporter expression in these cells that correspond with the differences in fLuc and rLuc BLI readout that was observed. This report points out several confounding factors in quantitative or semi-quantitative BLI related to the active efflux of luciferase substrates, particularly when SCs are involved.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

HEK-293 cell lines overexpressing ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 transporters (HEK-293/ABC-transporter), as well as HEK-293 mock cells (control cells stably transfected with empty vector), were generously provided by Drs. Susan Bates and Robert Robey (National Cancer Institute).23 These cells were cultured in MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 2 mg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen). The mouse ESC line, mES-J1, generously provided by Dr. Mark Tomishima (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), was cultured in the conditional medium (830 ml Knockout DMEM (Invitrogen), 150 ml fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 10 ml MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 10 ml L-Glutamine (200 mM), and 1600 U/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (Millipore, Billerica, MA). NIH/3T3 cells were obtained from ATCC. All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air incubator.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (AmBion, Austin, TX) before cDNA synthesis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Specific primers for mouse ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCG2 and β-actin gene for PCR amplification were as follows:

-

ABCB1: forward 5′-TCGACTCGCTACCTGATAAA-3′

backward 5′-GTGCCGTGCTCCTTGACCT-3′

-

ABCC1: forward 5′-CCCCATTCAGGCCGTGTAGA -3′

backward 5′-TCCAGGGCCATCCAGACTTC-3′

-

ABCG2: forward 5′-CCATGGGCCAGCACAGA-3′

backward 5′-AGGGTTCCCGAGCAAGTTT-3′

-

β-actin: forward 5′-CCTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAGATG-3′

backward 5′-GGGTGTAAAACGCAGCTCAGTAAC-3′

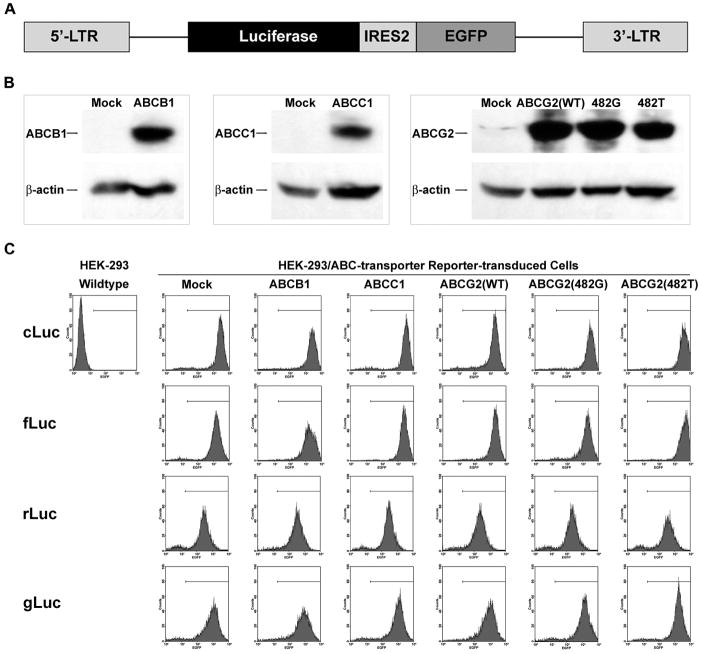

Plasmid construction and virus packaging

We developed a dual-reporter system in a SFG retrovirus backbone; the SFG plasmid was originally developed to transduce bone marrow cells for transplantation and was derived from Moloney murine leukemia virus.24 This vector contained a constitutively expressed luciferase gene and enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) separated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (Figure 1A). Four dual-reporter constructs were generated by cloning four different luciferases, cLuc,25 fLuc,26 rLuc and gLuc, into the vector, respectively. The reporter construct was transiently transfected into the H29 virus packaging cell line27 by Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen) according manufacturer’s instruction. To generate HEK-293/ABC-transporter cells with four different BLI reporters, supernatant from the packaging cells was applied to HEK-293 cells overexpressing ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 transporters and HEK-293 mock cells, respectively, with 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Two rounds of FACS were performed to select stable transduced GFP-positive reporter cells.

Figure 1.

Generation of HEK-293 reporter cells with ABC-transporter overexpression (HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells). A, structure of the dual-reporter system in a SFG backbone. Luciferase and GFP were constitutively expressed. GFP was used as a selection marker. B, validation of ABC-transporter overexpression in stably-transfected HEK-293/ABC-transporter cells by Western blotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. C, FACS analysis of the stably-transduced HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells. Mock cells, empty vector stably-transfected HEK-293 cells, were used as a negative control; ABCG2(WT), wildtype ABCG2; ABCG2(482G) and ABCG2(482T), two ABCG2 mutants with point mutations at amino acid 482 (R→G, ABCG2(482G) and R→T, ABCG2(482T). cLuc, fLuc, rLuc and gLuc: HEK-293/ABC-transporter cells transduced with cLuc-IRES2-EGFP, fLuc-IRES2-EGFP, rLuc-IRES2-EGFP, and gLuc-IRES2-EGFP, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Total protein (10 μg) from HEK-293/ABC-transporter cells were run on 4–12% PAGE (Invitrogen) and electrophoretically transferred to a PVDF membrane. Mouse anti-ABCB1 monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) (1:1000) and mouse anti-ABCC1/ABCG2 monoclonal antibodies (Kamiya Biomedical, Seattle, WA) were used as primary antibodies. After binding an HRP-anti-mouse-IgG antibody (1:5000) (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA), Western blot was visualized using the ECL luminescent system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The stripped membrane was reprobed by mouse anti-beta-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma) (1:10000).

In vitro BLI

HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells were seeded in triplicate into two separate 96-well-plates (1×104 cells/well). After 24 hours, potassium D-luciferin (Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA) was added to cLuc and fLuc reporter cells on one plate (final concentration 150 μg/ml), or coelenterazine (Biotium, Hayward, CA) was added to rLuc and gLuc reporter cells (final concentration of 470 nM). A Biospace system (Biospace Lab, Paris, France) was used to measure bioluminescence intensity for these in vitro studies. Cells in the second, duplicated plate were lysed with lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) (20 μl/well) for 10 min at room temperature. BLI from the cell extracts was determined by the above procedure. For the ABC-transporter inhibition assay, HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells were preincubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of Reversin 121 (ABCB1 inhibitor, Sigma, 1.5 μg/ml), MK-571 (ABCC1 inhibitor, Sigma, 1.5 μM) and fumitremorgin C (FTC) (ABCG2 inhibitor, 1 μM, a generous gift from Drs. Bates and Robey). Photo Acquisition (V2.7) and M3Vision software were used to acquire and analyze BLI data. Light intensities of the regions of interests were expressed as total flux (photons per second).

In vivo BLI

Animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee in Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. All animal procedures were performed under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia. 1×106 HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells were suspended with Matrigel (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and injected subcutaneously in 8-week-old female BALB/cAnNCr-nu/nu mice. Four xenografts were inoculated in each mouse and locations of the xenografts were paired (Mock vs ABC-transporter reporter cells) in both shoulders and thighs for BLI imaging convenience. These animals were injected retro-orbitally with potassium D-luciferin (60 mg/kg) for fLuc- and cLuc-expressing xenografts, or with coelenterazine (0.4 mg/kg) for rLuc- and gLuc-expressing xenografts. The animals were imaged 2 minutes after injection to obtain the initial, pretreatment BLI intensity measure, using an IVIS 200 imaging system (Caliper). The animals then received two injections separated by one hour (injection of the vehicle followed one hour later by injection of the ABC transporter inhibitor). BLI was performed every 5 minutes following each injection, and the BLI intensity data was normalized to the value obtained immediately after each injection. In the ABC transporter inhibition studies, mice were treated with Reversin 121 (2.5 mg/kg in 50 μl DMSO, i.p. injection), MK-571 (50 mg/kg in 100 μl saline, i.p. injection) or FTC (25 mg/kg in 100 μl DMSO/cremopher/ethanol/saline (1:1:2:12), tail vein injection). Living Image software was used to acquire and analyze BLI data.

Statistics

Each cellular assay was performed in triplicate and xenograft studies were repeated in five animals for each HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cell line. Data were presented as mean±SE. t test was used to determine the significance and values of p<0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

The effects of ABC-transporters on luciferase-based BLI intensity have not been fully elucidated. We investigated whether BLI intensity could be enzyme (luciferase)-dependent as well as substrate-dependent when a constitutive reporter is expressed at comparable levels. In a retroviral plasmid, SFG vector24, we developed a dual-reporter system with a bicistronic cassette (e.g., luciferase-IRES2-EGFP) (Figure 1A). The dual reporter constructs allow both bioluminescence and fluorescence constitutive reporter imaging. Four different luciferase, cLuc, fLuc, rLuc and gLuc, were cloned into the bicistronic cassette respectively. HEK-293 cells stably transfected to overexpress ABC-transporters (ABCB1, ABCC1, ABCG2, and two ABCG2 mutants with point mutations at amino acid 482 (R→G, ABCG2(482G) and R→T, ABCG2(482T))11 were used in this study. Overexpression of ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 (wildtype and mutants) in HEK-293/ABC-transporter cells was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 1B). Then these five cell lines, plus HEK-293 mock cells, were stably transduced with the four different dual-reporter constructs (cLuc/fLuc/rLuc/gLuc-IRES2-EGFP), respectively. Stably reporter-transduced cells were selected by FACS based on comparable level of GFP expression (Figure 1C).

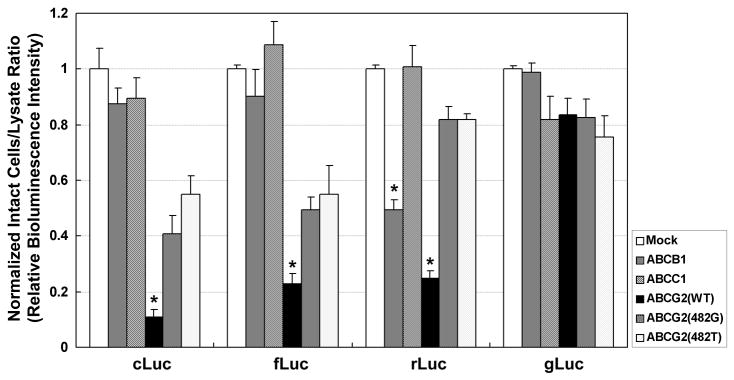

To investigate the effect of ABC-transporters on luciferase-based BLI, we examined the BLI intensity from HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells. These in vitro studies showed that BLI intensity of intact cells, compared to cell lysates, decreased significantly when ABCG2 was overexpressed in HEK-293 cLuc, fLuc and rLuc reporter cells (Figure 2). The normalized BLI intensity ratio of living cells to cell lysates was 0.11, 0.23 and 0.25 in HEK-293/ABCG2/cLuc, fLuc and rLuc cells, respectively. No significant BLI change was observed in HEK-293/ABCG2/gLuc cells. Overexpression of ABCB1 transporter reduced the BLI intensity ratio only in HEK-293/ABCB1/rLuc cells by 51%. ABCC1 overexpression did not affect the BLI intensity ratio in any of the HEK-293/ABCC1/reporter cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative BLI intensity of HEK-293 reporter cells with and without ABC transporter overexpression. Reporter cells were seeded into duplicate 96-well-plates for BLI intensity measurements in intact cells and in cell lysates. Relative BLI intensity was determined by calculating the BLI intensity ratio from intact cells divided by that from cell lysates, and then normalized to the value obtained from mock cells. Mock refers to empty vector stably-transfected HEK-293 cells without ABC-transporter overexpression; the cell-to-lysate BLI intensity ratio of the mock reporter cells (prior-to normalization) was: cLuc 0.095±0.003; fLuc 0.085±0.005; rLuc 0.059±0.002; gLuc 0.919±0.015. Error bar, SE; *, p<0.05.

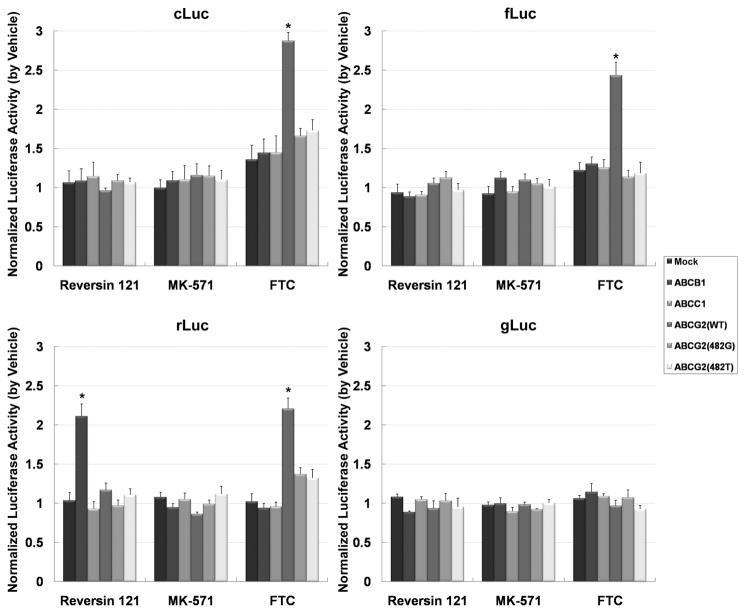

The effect of selective ABC-transporter inhibitors (Reversin 121 against ABCB1,28 MK-571 against ABCC1,29 and FTC against ABCG230) on BLI intensity from HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells was also studied. Compared with vehicle treatment, Reversin 121 elevated BLI intensity 2.11±0.16 fold only in HEK-293/ABCB1/rLuc reporter cells, whereas FTC increased BLI intensity more than 2-fold in HEK-293/ABCG2/cLuc, fLuc and rLuc reporter cells (Figure 3). These results indicate that ABCG2 expression modulates BLI signal intensity generated from both D-luciferin and coelenterazine, and that ABCB1 affects coelenterazine (but not D-luciferin) signal intensity. GLuc signal intensity was affected minimally or not at all by upregulating ABC-transporter expression (Figure 2) or by incubation with any of the specific transporter inhibitors (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Normalized BLI intensity of HEK-293 reporter cells with and without ABC transporter overexpression treated by selective ABC transporter inhibitors. Relative BLI intensity was determined by calculating the BLI intensity intact cells/cell lysates ratio, and then normalized to the value obtained from corresponding vehicle-treated cells. Reversin 121, ABCB1 inhibitor; MK-571, ABCC1 inhibitor; FTC, ABCG2 inhibitor. Error bar, SE; *, p<0.05.

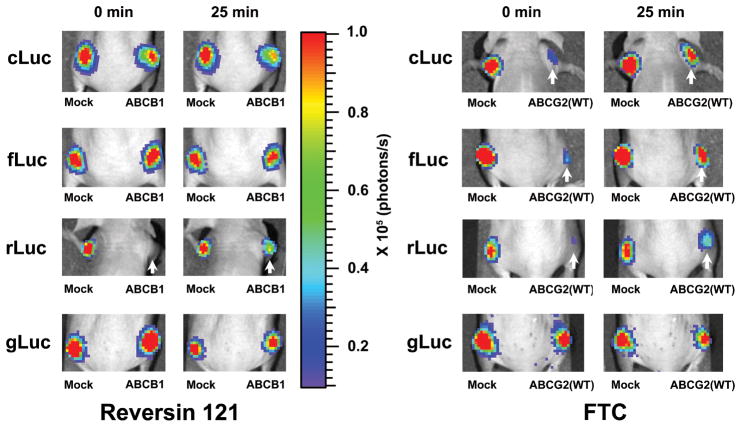

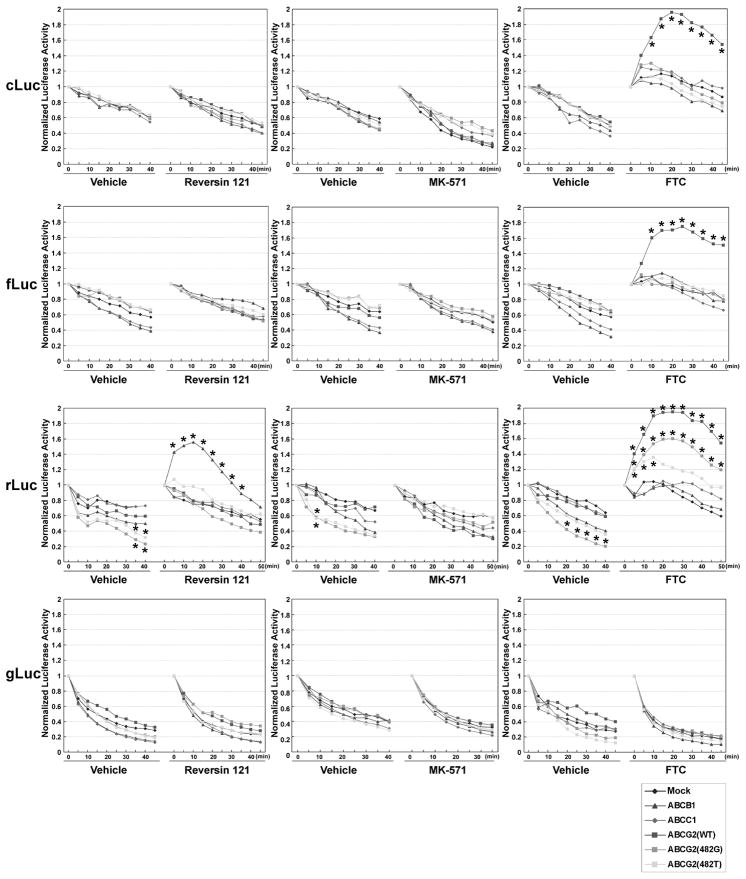

BLI of xenografts derived from HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells confirmed the results of the in vitro inhibitor treatment studies. Animals bearing subcutaneous HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter xenografts were imaged sequentially after Reversin 121, MK-571, FTC and corresponding vehicle treatment. Reversin 121 had little or no effect on cLuc- or fLuc-based BLI intensity with D-luciferin (Figure 4, left upper panels), or on coelenterazine-generated gLuc BLI intensity (Figure 4, left lower panel) in mock or any of the overexpressing ABC-transporter HEK-293 xenografts. In contrast, BLI intensity was barely measureable in HEK-293/ABCB1/rLuc xenografts prior to Reversin 121 administration, but was clearly visible after injecting Reversin 121 (Figure 4, left panel, white arrow). The time-course of mean BLI intensity for these studies (n = 5) is shown in Figure 5 (left panels). Twenty minutes after Reversin 121 administration, the signal intensity increase in HEK-293/ABCB1/rLuc xenografts was 1.56±0.21 fold, and the signal from the HEK-293/mock/rLuc xenografts decreased ~25% (Figure 5). These results show that inhibition of the ABCB1 transporter elevated only intracellular enzyme-coelenterazine-based BLI intensity (rLuc), and not the secreted enzyme-coelenterazine-based BLI intensity (gLuc).

Figure 4.

Effects of specific ABC transporter inhibitors on BLI intensity from xenografts derived from HEK-293 reporter cells with and without ABC transporter overexpression. Reporter cells were subcutaneously implanted into the nude mice. After inhibitor or vehicle injection, sequential imaging was performed. Representative images of the same animal are shown. The pseudocolor bar shows BLI intensity (photons/cm2/sec/seradian). The white arrows point to xenografts with enhanced BLI intensity after inhibitor treatment. Reversin 121, ABCB1 inhibitor; FTC, ABCG2 inhibitor.

Figure 5.

Time course of the normalized BLI signal from HEK-293 reporter-xenografts with and without ABC transporter overexpression treated with specific ABC transporter inhibitors. The BLI signal immediately after inhibitor or vehicle injection was defined as 1. Data are presented as mean normalized BLI signal from five xenografts in separate animals. *, the data with significant differences (p<0.05) compared with the normalized luciferase activity profiles of mock cells. Standard errors range from 0.012 to 0.125. Reversin 121, ABCB1 inhibitor; MK-571, ABCC1 inhibitor; FTC, ABCG2 inhibitor.

MK-571 had no effect on any of the xenografts (Figure 5, middle panels). It is consistent with the in vitro result and suggests that ABCC1 does not affect BLI intensity in all HEK-293/ABC-transporter reporter cells. In contrast, FTC administration significantly increased BLI intensity in both D-luciferin and coelenterazine-based HEK-293 reporter xenografts expressing high levels of the ABCG2 transporter (Figure 4, right panels). Again, no difference was observed with the predominantly secreted luciferase from the gLuc reporter. The time-course of mean BLI intensity for these studies is shown in Figure 5 (right panels). FTC treatment induced 1.93±0.15, 1.75±0.18, 1.95±0.23 fold increase of BLI was detected in HEK-293/ABCG2/cLuc, HEK-293/ABCG2/fLuc and HEK-293/ABCG2/rLuc cells at the 25-min time point (n=5) (Figure 5). These data suggest that blocking ABCG2 transporter activity may increase the intracellular concentration of both D-luciferin and coelenterazine and result in the increase in BLI signal intensity.

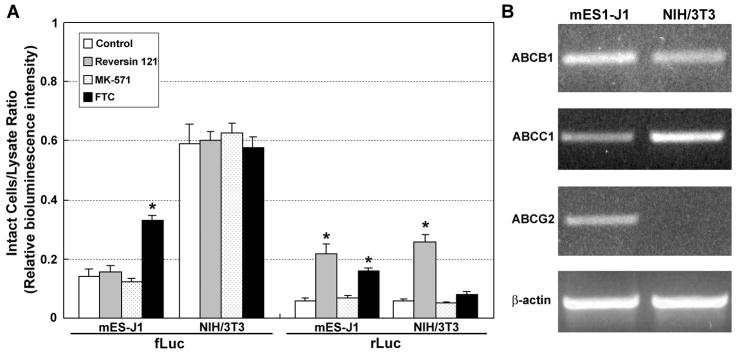

To study the effects of ABC-transporters expressed in mouse ESCs, we stably transduced a mouse ESC line (mES-J1) and a mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line (NIH/3T3) with the fLuc-IRES2-EGFP and rLuc-IRES2-EGFP reporter constructs (Figure 1A). In the first series of experiments, BLI signal intensity from intact reporter-transduced mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 cells was compared to lysates from the same reporter cells (Figure 6A). There was a significant difference in the BLI intensity ratio, comparing intact cells to cell lysates. For D-luciferin, the ratio was 0.142±0.024 for mES-J1/fLuc cells and 0.591±0.069 for NIH/3T3/fLuc cells; the difference between the two cell lines was significant (p<0.01). For coelenterazine, the ratio was 0.058±0.008 for mES-J1/rLuc cells and 0.059±0.005 for NIH/3T3/rLuc cells, and the difference between the two cell lines was not significant (p>0.05).

Figure 6.

A, relative BLI intensity of mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 reporter cells treated by selective ABC transporter inhibitors. Relative BLI intensity is the ratio of BLI intensity from intact cells divided by that from cell lysates. Control, untreated cells; Reversin 121, ABCB1 inhibitor; MK-571, ABCC1 inhibitor; FTC, ABCG2 inhibitor. *, relative BLI intensity from the treated cells has significant difference compared with untreated cells, p<0.01. Error bar, SE. B, endogenous expression of ABC-transporters in mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 cells by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. β-actin was used as a loading control.

To explain the discordance of BLI intensity in fLuc and rLuc reporter cells, we first examined the expression level of ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG211 in mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 cells by semi-quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (Figure 6B). Notably, ABCB1 was expressed in both mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 cells, whereas ABCG2 expression was only detected in mES-J1 cells. Then, ABC-transporter activity in mES-J1 and NIH/3T3 reporter cells was selectively blocked using specific ABC-transporter inhibitors to address whether endogenous ABCB1 and ABCG2 expression can affect BLI intensity. As shown in Figure 6A, inhibition of ABCB1 by Reversin 121 increased the relative intensity in coelenterazine-based rLuc-BLI in both cell lines; the intact cell to cell lysate ratio increased 0.058→0.218 in mES-J1-rLuc cells and 0.059→0.259 in NIH/3T3-rLuc cells. Inhibition of ABCG2 by FTC elevated the relative BLI intensity in both fLuc and rLuc mES1-J1 reporter cells, but not in NIH/3T3 reporter cells. The increase 0.142→0.331 in mES-J1-fLuc cells and 0.058→0.259 in mES-J1-rLuc cells was comparable. The absence of an FTC response in NIH/3T3 reporter cells is consistent with undetectable ABCG2 expression in these cells. These data confirm that high endogenous expression of ABCB1 and ABCG2 in mESCs can modulate both coelenterazine-based rLuc-BLI and D-luciferin-based fLuc-BLI.

Discussion

In this report, we examined the effects of three major ABC-transporter proteins (ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2) on luciferase-based BLI. This is the first time that four widely used luciferases, cLuc, fLuc, rLuc and gLuc, were systemically studied and compared with respect to the effects of ABC-transporters on the magnitude of BLI readout.

Our new finding is that coelenterazine, the substrate for rLuc and gLuc, is a substrate ABCG2-mediated efflux. Overexpression of ABCG2 reduced BLI intensity by 75%, and inhibition of ABCG2 transporter activity increased BLI intensity more than 2-fold, in HEK-293/ABCG2/rLuc reporter cells. In contrast, there was no significant change of BLI intensity with overexpression or inhibition of ABCG2 in HEK-293/ABCG2/gLuc reporter cells. The major difference between rLuc and gLuc is their subcellular localization; rLuc is an intracellular protein and gLuc is a secreted protein, which suggests that coelenterazine-based BLI intensity change is primarily related to an intracellular substrate concentration alteration, mediated by the ABCG2 efflux pump. Additionally, we confirmed the previous observation that coelenterazine is a substrate for the ABCB1 efflux pump.21 Thus, coelenterazine-based rLuc-BLI intensity could be modulated by several different transporter proteins, including ABCB1 and ABCG2, since different transporters have overlapping substrate specificities.

In addition, we show that ABCG2 affects D-luciferin-based cLuc- and fLuc-BLI in a similar way, extending previous work that demonstrated D-luciferin was a substrate ABCG2-mediated efflux.22 Although cLuc and fLuc share the same substrate, D-luciferin, to generate bioluminescence, they have distinct evolutionary origins and very different enzyme structures. Therefore, we compared the ABCG2 effects on cLuc- and fLuc-based BLI both in vitro and in vivo to determine whether the effect on BLI intensity was more substrate-dependent or more luciferase-dependent. Consistent with the prior report,22 overexpression of ABCG2 resulted in a comparable decrease in BLI intensity in HEK-293/ABCG2/cLuc and fLuc reporter cells, and inhibition of ABCG2 transporter activity led to a comparable increase in BLI intensity. These results indicate that ABCG2 transporter modulation of D-luciferin-based BLI is luciferase-type independent, and depends on a change in the intracellular concentration of D-luciferin.

Bioluminescence involves exergonic reactions of molecular oxygen with substrate (luciferin) and enzyme (luciferase), resulting in photons of visible light.31 Several factors, including the expression level of luciferase, oxygen concentration, presence of magnesium ions, and substrate concentration determine the BLI intensity. For example, hypoxia in solid tumors could influence oxygen availability for the bioluminescence reaction, leading to an underestimation of the actual number of luciferase-labeled cells during in vivo experiments.32 Routes of substrate administration33,34 and vascular permeability35,36 also influence BLI dynamics considering substrate delivery. Here we show that overexpression of ABC-transporters also impacts on the magnitude of BLI readout, and that this mostly occurs through modulation of the intracellular substrate concentration.

The decrease in BLI readout observed in ABC-transporter overexpressed-cells is due to a greater efflux of substrate in these cells, which is the only one component of several potential confounding factors affecting BLI values. We compared the normalized BLI readout from mock-reporter cells and ABC-transporter-overexpressed reporter cells under the same culture and imaging condition, to avoid differences in luciferase enzyme expression, oxygen concentration and magnesium ion concentration in both the in vitro and in vivo experiments. Our results showed that blocking ABC-transporter activity with selective inhibitors, Reversin 121 for ABCB1 and FTC for ABCG2, increased BLI readout approximately 2-fold, which are consistent with the previous literature.21,22 Considering that we inhibited only one type of ABC-transporter in each inhibition experiment-set and that the inhibition was most likely incomplete at the non-toxic inhibitor concentrations used, we speculate that the ABC-transporter effect could be highly significant in some biological systems.

Since many therapeutic compounds have been shown to be substrates for ABC efflux-transporters and that upregulation of transporter expression can lead to drug resistance and treatment failure, new ABC-transporter inhibitors have been sought. A treatment paradigm has been advocated, where transport inhibitors are considered ‘tumor cell sensitizing agents’.37 In this paradigm, drug-resistant cells in a tumor can be effectively killed through a drug-combination strategy in which a cytotoxic drug was given along with an ABC-transporter inhibitor.37 Despite initial optimism, the results of early clinical trials using ABC-transporter inhibitors have been disappointing.38 Functional redundancy of this highly conserved transporter superfamily has limited the clinical success of ABC-transporter inhibitors to date.39 High throughout screens for assaying inhibitors of the full set of ABC-transporters are required in order to obtain more effective inhibitors.40 Our and others’ data21,22 demonstrate that both coelenterazine and D-luciferin are substrates for ABC-transporter proteins (ABCB1 and ABCG2). The reporter cell lines that we have developed in this study could facilitate a high throughout cellular assay for compounds that modulate ABCB1 or ABCG2 transport, based on rLuc- or fLuc-BLI techniques. Considering the low-cost, high sensitivity and convenience of BLI, drug screening and animal studies based on BLI may provide a new tool to accelerate the development of new ABCB1 and ABCG2 inhibitors.

Recent progress in SC research has led to the discovery that SCs or progenitor cells (PCs) can be induced to differentiate into a wide range of tissues and potentially can be used for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine.41 Monitoring SCs/PCs trafficking in vivo by BLI is considered a very important new imaging strategy. It has enabled the non-invasive, repetitive assessment of SC/PC location, migration, proliferation, and differentiation within the recipient organism.42,43 However, in some cases, BLI is not always effective for monitoring SCs/PCs. For example, the cytomegalovirus promoter (pCMV), a frequently used promoter to drive constitutive BLI reporter gene expression, is quickly silenced in ESCs by the endogenous epigenetic mechanisms that leads to loss of reporter gene expression over time.44 Other molecular mechanisms, in addition to CMV promoter silencing, that result in a loss or decrease in BLI reporter gene expression or BLI signal intensity in SCs/PCs should be investigated in the future.

High expression of ABC-transporter proteins is observed in SCs13. For example, hematopoietic SCs express high levels of ABCG2. As the SCs/PCs become lineage-committed, expression of the ABCG2 gene is silenced in most committed progenitor and mature blood cells.45 In this study, we used a mESC line, mES-J1, with high endogenous expression of ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2. Our results show that overexpression of ABC-transporters, including ABCB1 and ABCG2, significantly reduced BLI readout-intensity for both D-luciferin- and coelenterazine-based luciferases. This reduction in BLI most likely reflects reduced intracellular substrate concentrations due to enhanced efflux the substrates. For example, coelenterazine-based BLI intensity in intact mES-J1-rLuc cells decreased 94% compared to a similar assay performed on cell lysates. Inhibition of ABCB1 and ABCG2 activity in the intact mES-J1-rLuc cells increased the BLI by 3.8 fold and 2.8 fold, respectively (Figure 6A). These findings clearly demonstrate the potent effects of ABC-transporter expression and one likely mechanism for low BLI signal intensity in luciferase-transduced SCs. Thus, a note of caution is raised with respect to future applications luciferase-based BLI in SC research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Susan Bates, Robert Robey, Mark J. Tomishima and Vladimir Ponomarev for their generous reagents and cell lines. We thank Dr. Tatiana Beresten and Ms. Katerina Dyomina for technical assistance. We thank the SKI Stem Cell Research Facility and Small Animal Imaging Core for their support.

Abbreviations

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- BLI

bioluminescence imaging

- cLuc

click beetle luciferase

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- fLuc

firefly luciferase

- FTC

fumitremorgin C

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- gLuc

gaussia luciferase

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- PC

progenitor cell

- rLuc

renilla luciferase

- SC

stem cell

Footnotes

Financial disclosure of authors: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P50 CA86438 and R01 CA102673. MSKCC Small Animal Imaging Core Facility was supported NIH Small-Animal Imaging Research Program grant R24 CA83084 and NIH Center grant P30 CA08748.

References

- 1.Higgins CF. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean M, Rzhetsky A, Allikmets R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001;11:1156–66. doi: 10.1101/gr.184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Childs S, Ling V. The MDR superfamily of genes and its biological implications. Important Adv Oncol. 1994:21–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean M, Allikmets R. Evolution of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:779–85. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80011-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fromm MF. Importance of P-glycoprotein at blood-tissue barriers. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:423–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borst P, Elferink RO. Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:537–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trowsdale J, Hanson I, Mockridge I, et al. Sequences encoded in the class II region of the MHC related to the ‘ABC’ superfamily of transporters. Nature. 1990;348:741–4. doi: 10.1038/348741a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abele R, Tampe R. The ABCs of immunology: structure and function of TAP, the transporter associated with antigen processing. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:216–24. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Kimura Y, Nagata K, et al. ABC proteins: key molecules for lipid homeostasis. Med Mol Morphol. 2005;38:2–12. doi: 10.1007/s00795-004-0278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher JI, Haber M, Henderson MJ, et al. ABC transporters in cancer: more than just drug efflux pumps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:147–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates SE. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teodori E, Dei S, Martelli C, et al. The functions and structure of ABC transporters: implications for the design of new inhibitors of Pgp and MRP1 to control multidrug resistance (MDR) Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:893–909. doi: 10.2174/138945006777709520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunting KD. ABC transporters as phenotypic markers and functional regulators of stem cells. Stem Cells. 2002;20:11–20. doi: 10.1002/stem.200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah K, Weissleder R. Molecular optical imaging: applications leading to the development of present day therapeutics. NeuroRx. 2005;2:215–25. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood KV, Lam YA, Seliger HH, et al. Complementary DNA coding click beetle luciferases can elicit bioluminescence of different colors. Science. 1989;244:700–2. doi: 10.1126/science.2655091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenz WW, McCann RO, Longiaru M, et al. Isolation and expression of a cDNA encoding Renilla reniformis luciferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4438–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wurdinger T, Badr C, Pike L, et al. A secreted luciferase for ex vivo monitoring of in vivo processes. Nat Methods. 2008;5:171–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serganova I, Moroz E, Vider J, et al. Multimodality imaging of TGFbeta signaling in breast cancer metastases. Faseb J. 2009;23:2662–72. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang JH, Chung JK. Molecular-genetic imaging based on reporter gene expression. J Nucl Med. 2008;49 (Suppl 2):164S–79S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, Hajibeigi A, Ren G, et al. Retention of the radiotracers 64Cu-ATSM and 64Cu-PTSM in human and murine tumors is influenced by MDR1 protein expression. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1332–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.061879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pichler A, Prior JL, Piwnica-Worms D. Imaging reversal of multidrug resistance in living mice with bioluminescence: MDR1 P-glycoprotein transports coelenterazine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1702–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304326101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Bressler JP, Neal J, et al. ABCG2/BCRP expression modulates D-Luciferin based bioluminescence imaging. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9389–97. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robey RW, Honjo Y, Morisaki K, et al. Mutations at amino-acid 482 in the ABCG2 gene affect substrate and antagonist specificity. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1971–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riviere I, Brose K, Mulligan RC. Effects of retroviral vector design on expression of human adenosine deaminase in murine bone marrow transplant recipients engrafted with genetically modified cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:6733–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobrenkov K, Olszewska M, Likar Y, et al. Monitoring the efficacy of adoptively transferred prostate cancer-targeted human T lymphocytes with PET and bioluminescence imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1162–70. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moroz E, Carlin S, Dyomina K, et al. Real-time imaging of HIF-1alpha stabilization and degradation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hagani AB, Riviere I, Tan C, et al. Activation conditions determine susceptibility of murine primary T-lymphocytes to retroviral infection. J Gene Med. 1999;1:341–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199909/10)1:5<341::AID-JGM58>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koubeissi A, Raad I, Ettouati L, et al. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug efflux by aminomethylene and ketomethylene analogs of reversins. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5700–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverstein PS, Audus KL, Qureshi N, et al. Lipopolysaccharide Increases the Expression of Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 (MRP1) in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robey RW, Medina-Perez WY, Nishiyama K, et al. Overexpression of the ATP-binding cassette half-transporter, ABCG2 (Mxr/BCrp/ABCP1), in flavopiridol-resistant human breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson T, Hastings JW. Bioluminescence. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:197–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriyama EH, Niedre MJ, Jarvi MT, et al. The influence of hypoxia on bioluminescence in luciferase-transfected gliosarcoma tumor cells in vitro. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2008;7:675–80. doi: 10.1039/b719231b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross S, Abraham U, Prior JL, et al. Continuous delivery of D-luciferin by implanted micro-osmotic pumps enables true real-time bioluminescence imaging of luciferase activity in vivo. Mol Imaging. 2007;6:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue Y, Kiryu S, Izawa K, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous and intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin for in vivo bioluminescence imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:771–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-1022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paroo Z, Bollinger RA, Braasch DA, et al. Validating bioluminescence imaging as a high-throughput, quantitative modality for assessing tumor burden. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:117–24. doi: 10.1162/15353500200403172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao D, Richer E, Antich PP, et al. Antivascular effects of combretastatin A4 phosphate in breast cancer xenograft assessed using dynamic bioluminescence imaging and confirmed by MRI. Faseb J. 2008;22:2445–51. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-103713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dean M, Fojo T, Bates S. Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:275–84. doi: 10.1038/nrc1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaye SB. Reversal of drug resistance in ovarian cancer: where do we go from here? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2616–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szakacs G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, et al. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:219–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Byun Y, Ren YR, et al. Identification of inhibitors of ABCG2 by a bioluminescence imaging-based high-throughput assay. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5867–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H, Park J, Forget BG, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine: an argument for continued research on human embryonic stem cells. Regen Med. 2009;4:759–69. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang Y, Shah K, Messerli SM, et al. In vivo tracking of neural progenitor cell migration to glioblastomas. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:1247–54. doi: 10.1089/104303403767740786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waerzeggers Y, Klein M, Miletic H, et al. Multimodal imaging of neural progenitor cell fate in rodents. Mol Imaging. 2008;7:77–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson K, Yu J, Lee A, et al. In vitro and in vivo bioluminescence reporter gene imaging of human embryonic stem cells. J Vis Exp. 2008 doi: 10.3791/740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scharenberg CW, Harkey MA, Torok-Storb B. The ABCG2 transporter is an efficient Hoechst 33342 efflux pump and is preferentially expressed by immature human hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 2002;99:507–12. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]