Abstract

Gastrointestinal mucosa is an early target of HIV and a site of viral replication and severe CD4+ T-cell depletion. However, effects of HIV infection on gut mucosal innate immune defense have not been fully investigated. Intestinal Paneth cell (PC)-derived α-defensins constitute an integral part of the gut mucosal innate defense against microbial pathogens. Using the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infected rhesus macaque model of AIDS, we examined the level of expression of rhesus enteric α-defensins (REDs) in jejunal mucosa of rhesus macaques during all stages of SIV infection, using real-time PCR, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry. An increased expression of RED mRNAs was found in PC at the base of the crypts in jejunum at all stages of SIV infection as compared to uninfected controls. This increase correlated with active viral replication in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). Loss of RED protein accumulation in PC was seen in animals with simian AIDS (SAIDS). This was associated with the loss of secretory granules in PC, suggesting an increase in degranulation during advanced SIV disease. The α-defensin-mediated innate mucosal immunity was maintained in PC throughout the course of SIV infection despite the mucosal CD4+ T-cell depletion. The loss of RED protein accumulation and secretion was associated with an increased incidence of opportunistic enteric infections and disease progression. Our findings suggest that local innate immune defense exerted by PC derived defensins contributes to the protection of gut mucosa from opportunistic infections during the course of SIV infection.

Keywords: HIV, SIV, defensin, GALT, innate

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) complications, including diarrhea, weight loss, and enteric opportunistic infections occur frequently in therapy-naïve HIV-infected patients (1-2). HIV infection causes severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) early in infection, which contributes to impaired T-cell responses against pathogens at gut mucosal sites (3). Studies on HIV pathogenesis have been focused on the impairment of HIV-specific immune response and its role in the development of AIDS (4-5). However, innate immune defenses play a critical role in the protection of GALT against pathogens, and impairment of the innate immune system may accelerate disease progression. A better understanding of the mucosal innate defenses during HIV infection will provide insights into the mechanisms of HIV enteropathogenesis.

The GI epithelium is an important source of innate immune response and provides a functional barrier against enteropathogenic bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Paneth cells (PC) located at the base of intestinal crypts are key players in the innate immune defense of the intestinal mucosa and express an array of host defense proteins and peptides, including α-defensins (6). Human PC produce two known α-defensins, human defensin-5 (HD-5), and HD-6; whereas, rhesus macaque PC express several highly diverse enteric α-defensins (7) termed rhesus enteric defensins (REDs), of which six have been reported (8-9). The role of defensins has been well-established in determining the composition of the small bowel microbiota (10) and in protecting the intestinal crypt epithelium against colonization by microorganisms (11-12). Anti-HIV activity of various α-, β-, and θ-defensins have also been reported but their role in controlling HIV infection is unknown (13-14). The loss of α-defensin during HIV infection may lead to overgrowth of enteric pathogens resulting in gastrointestinal dysfunction.

The simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaque model is most suitable for the study of HIV-associated enteropathy (15). Rapid depletion of CD4+ T-cells in GALT correlates with active viral replication during primary SIV infection (16). Effects of the SIV infection on enteric innate immune responses in the SIV model have not been fully explored. We hypothesize that mucosal innate immune defenses, including α-defensin expression and secretion, play an important role in protecting the host against intestinal microbial pathogens in SIV infection and may locally compensate for the loss of T-cell mediated immune responses. Therefore, we sought to determine α-defensin (RED) expression during SIV infection by analyzing intestinal tissues from rhesus macaques at different stages of infection with and without antiretroviral therapy (ART). Our data showed that RED mRNA expression increased in response to SIV infection. SIV-infected animals treated with ART also maintained RED expression. A marked reduction in RED protein levels was observed in gut mucosa of animals with advanced SIV disease, coinciding with increased incidence of opportunistic infections. Our findings highlight the importance of α-defensins in protection against mucosal pathogens despite severe CD4+ T-cell depletion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rhesus macaques, SIV infection and therapy

Peripheral blood and intestinal tissue samples from 44 colony-bred rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were evaluated (17). Animals were housed in accordance with American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines. Samples from 6 healthy, SIV-negative animals served as negative controls. Thirty eight animals were inoculated intravenously with 10-100 animal infectious doses of pathogenic SIVmac251 and were euthanized during primary SIV infection (n=13), chronic infection (n=9), or during the advanced infection with simian AIDS (n=7). Nine SIV-infected animals received 9-[(R)-2-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl] adenine (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or PMPA) (Norbert Bischoffberger, Gilead Incorporated) monotherapy once daily at 10-30 mg/kg body weight, for 6-132 weeks, beginning at 6 (n=5) or 10 (n=4) weeks post-SIV inoculation (18). Animals receiving ART were euthanized between 12 and 142 weeks post-infection (6-132 weeks post-therapy). Longitudinal jejunal biopsy samples were collected by upper endoscopy and peripheral blood samples by venipuncture (19).

Microbiological and parasitological examination of intestinal mucosa

Intestinal specimens collected prior to SIV infection, at the onset of an episode of diarrhea and at necropsy, were examined for the presence of Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Plesiomonas, Aeromonas and Campylobacter species. Fecal specimens were screened for the presence of parasites and bacterial overgrowth using both a saline and an iodine wet preparation. The formalin/ethyl acetate sedimentation procedure was used for the detection of ova and parasites. The detection of Cryptosporidia oocysts and Giardia cysts was performed by direct immunofluorescence assay using the Merifluor Crypto & Giardia assay (Meridian Bioscience,Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Lesions and occult opportunistic infections were identified by microscopic examination of jejunum tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Clinical findings were obtained from health records at the CNPRC.

Measurement of viral burden

Viral burden in plasma and intestinal tissue samples was determined by real time RT-PCR analysis as previously described (20). A change in the SIV loads was presented as n-fold difference compared to the lowest level of expression as previously described (ΔΔCT method) (20). The SIV infected cells in intestinal tissue samples were detected and localized using in situ hybridization (ISH) assay (16). Formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue sections were hybridized with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled SIV gag-specific RNA probe (SIV239, clone from Charles Brown, Cat # L3-2100SP, Lofstrand Labs Ltd.; Gaithersburg, MD) at 56°C for 15 hours and processed. SIV-infected cells, stained with NBT-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Roche) in Levamisole and counterstained with nuclear fast red, were visualized by the presence of blue/violet precipitate under light microscopy. Viral burden was determined by counting number of SIV-positive cells/10× field of view. Five fields were counted for each sample and an average number recorded. The magnitude of viral infection was scored on a relative scale from 0 to 6, where 0 indicated no positive targets present, a score of 1 indicated >0 to 1; 2 = 1 to 5; 3 = 6 to 10; 4 = 11 to 15; 5 = 16 to 20; 6 = >20 positive targets/10× field of view.

Localization of RED RNA in Paneth Cells

Cells expressing RED RNA in intestinal samples were localized by in situ hybridization assay using a 204 nucleotide long DIG-labeled riboprobe, RED-J1 (Lofstrand, Ltd.) prepared from a cloned RED cDNA (Dr Alison Quayle), as previously described (9). The cells expressing RED RNA (dark blue/violet precipitate) were visualized by microscopic examination. The percentage of RED RNA + crypts was also evaluated by counting 30-50 crypts and evaluating for the presence or absence of RED mRNA in them.

Real-time PCR assay was used to determine the RED RNA levels in intestinal tissue samples. RED gene specific primers (rmDef-15f: CATCC TTGCT GCCAT TCTCC CATCCTTGCTGCCATTCTCCT and -159r: GTAGA GAGTC CATTT TCTTC AAAGG GTAGAGAGTCCATTTTCTTCAAAGGA) and probe (rmDef-75p: AACCC AGGAG AACCCAGGAGCAGCC) were designed. Reactions were carried out in a 7700 ABI PRISM® Sequence Detection System (7700SDS; Applied Biosystems). We determined the expression of a given gene using the comparative (ΔΔCT) method. The change in the expression during SIV infection was determined by comparing with the data from SIV-negative controls (20).

Localization of RED protein in intestinal tissue

The cellular localization of RED protein was determined by enzymatic immunohistochemistry (IHC) using the BioGenex i6000™ Automated Staining System and BioGenex IHC reagents (BioGenex, Inc., San Ramon, CA). Tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:800 dilution of rabbit anti-recombinant human defensin-5 (rHD-5) serum, (courtesy Dr. Tomas Ganz, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, LA) and stained using DAB (BioGenex, Inc., San Ramon). The RED protein expressing cells with red-brown color were visualized under light microscope. The percentage of crypts with HD5 protein was also analyzed.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed to determine the significance of the effects of SIV infection or therapy on plasma and gut viral loads, Paneth cell counts and RED expression using One way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison test (GraphPad Prism version 5.00, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com). When a Levene test was indicated, a weighted least squares was used, where the weights were chosen to be inversely proportional to the within-group variance. Magnitudes of effects were estimated with back-transformed least squares means.

RESULTS

SIV replication and histopathologic changes in gut mucosa

Thirty-eight SIV-infected were evaluated for the presence of SIV infected cells and pathologic changes in gut mucosa compared to six uninfected healthy rhesus macaques. SIV-negative control animals showed no obvious gastrointestinal pathology or clinical signs (Table 1). Animals with primary or chronic SIV infection exhibited lymphofollicular hyperplasia or lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, but had no evidence of pathologic changes or gastric dysfunction (Table 1). Animals with SAIDS exhibited multiple gastrointestinal complications, including gastroenterocolitis, non-responsive diarrhea and cholecystitis, as well as dehydration, inanition and pulmonary complications. One SIV-infected animal with rapid disease course (rapid progressor, RP) developed SAIDS at 12 weeks post-infection and had gastrointestinal complications. A long-term SIV-infected non-progressor (LTNP) animal suffered from Pneumonyssus simicola infection of the lungs and anemia at the time of necropsy, but experienced only mild gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical and pathological characteristics and microbial findings in study groups.

| Clinic opathological Markers | SIV Negative | Primary | Chronic | SAIDS | PMPA-treated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of infection (40) | Uninfected | 0.4 – 2 | 4 – 26 | 11 – 78 | 12 – 142 |

| Length of therapy (40) | None | Note | None | None | 4 – 132 |

| Age range (mo) | 59 – ICG | 32 – 72 | 25 – 68 | 25 – 75 | 82 – 103 |

| Weight range (kg) | 63 – 8.2 | 2.7 – 7.1 | 2.8 – 4.4 | 25 – 6.2 | 4.6 – 5.1 |

| Relative fold Δ in RED | (1.1) – 09 | (1.1) – 7.0 | 1.4 – 6.8 | 1.3 – 11.4 | (3.2) – (0.5) |

| Viral Burden: Relative fold Δ/ (ISH) | UD/(0) | 53×101-4.3×104/(1-6) | 1.0×101-18×102/(0-3) | UD-3.0×106/(0-6) | UD-0.4×101/(0.1) |

| Cinical Observations* | Various commensal bacteria. | Lympho-follicular hyperplasia, recurrent diarrhea, various commensal bacteria. | LA, SM, Pn. | Non-responsive recurrent diarrhea, cachexia, LA, SM, choledochocystits, I/D, pulmonary acariasis, Pn, GEC, various commensal & pathogenic bacteria, anemia | LA, renal tubular karyomegaly, SM, choledo-chocystitis. I/D, GEC. |

| Intestinal Pathologic Changes† | Mild Lp, ld. | Mild Lp, ld. | Mild to nod. Lp, ld, Ex, vbf. | Severe Lp, ld, Ex, vbf. | Mild to mod. Lp, ld, Ex, vbf, lamina propria micro-hemorrhage. |

| E; within normal limits. | E; acute to chronic, diffuse, mild to mod. | E; subacute to chronic, diffuse, mild to mod. | E; subacute to granulomatous, diffuse, mild to severe | E; subacute, diffuse, mild. | |

| ‡Comorbidity factors (%): | |||||

| Diarrhea | 33 | 25 | 11 | 100 | 11 |

| Cachexia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 11 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 0 | 17 | 33 | 100 | 67 |

| Splenomegaly | 0 | 0 | 22 | 57 | 33 |

| Enteritis | 17 | 33 | 33 | 10 | 78 |

| Colitis | 0 | 0 | 11 | 71 | 44 |

| ‡Secondary infections (%): | |||||

| Trichomonas hominis | 0 | 8 | 0 | 100 | 11 |

| Blastocystis hominis | 17 | 17 | 0 | 71 | 0 |

| Campylobacter (coli orjejuni) | 0 | 42 | 0 | 57 | 11 |

| Entamoeba coli | 17 | 8 | 0 | 57 | 0 |

| α-hemolytic Steptococci | 0 | 0 | 11 | 14 | 0 |

| Balantidium coli | 0 | 25 | 0 | 43 | 0 |

| Coagulase+ Staphylococcus | 0 | 0 | 11 | 29 | 0 |

| Cryptosporidia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Gardia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Gram – rods, anaerobic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Streptococcus viridans | 0 | 8 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

Detetminations made by veterinary pathologists at the time of necropsy.

Determinations made by retrospective examination of formalin-fixed tissues.

Data for comorbidity factros and secondary infections were obtained directly from clinical records maintained at the California National Primate Research Center, Davis, California. Microbial and parasitological examinations performed within one month of necropsy were included within these estimations. UD, undetectable levels (below 50 copies) of SIV RNA; NA, data is not available for this group, LA, lymphadenopathy, SM, splenomegaly, GE C, gastroenterocolitis; Pn, pneumonia; i/d, inanition/dehydration; Lp, lymphopenia; ld, lacteal dilatation; E, enteritis; Ex; exocytosis; vbf, villus blunting/fusion. Bold font designates values that differ significantly from other treatment groups (p<0.0395).

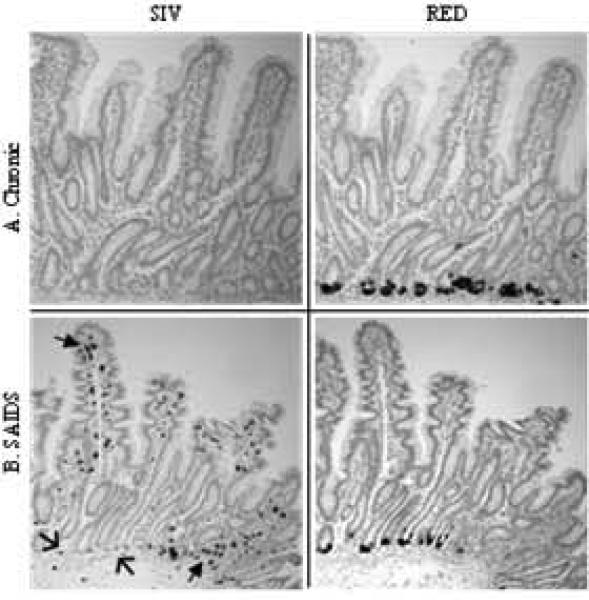

Viral burden in gut tissue of SIV-infected animals was evaluated by in situ hybridization as well as by real time RT-PCR (Table 1). SIV RNA was detected in lymphocytes and macrophages in the gut mucosa and was localized to the villus tips and cryptopatches (isolated lymphocytic aggregations). A few infected cells were detected in lamina propria surrounding the base of the crypts (Fig. 1 & 4). SIV+ cells were not frequent in the villus epithelium, with the exception of animal 26333, which had the majority of its infected cells located in the epithelial layer. Highest numbers of infected cells were seen during primary SIV infection (ISH score = 0-6, median 3.0) or during SAIDS (ISH score = 0-6, median 3.4). Low levels of SIV RNA+ cells were observed in the gut mucosa of therapy-naive animals with chronic SIV infection, as well as in the LTNP (ISH score = 0-2, median 1.3). In contrast, the RP animal had high numbers of SIV-infected jejunal lymphocytes (ISH score = 6).

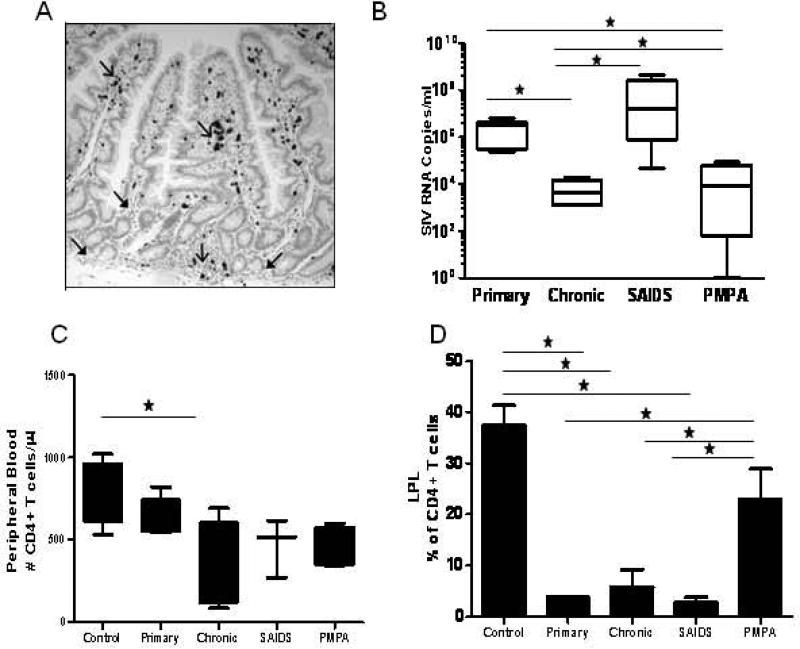

Figure 1. Plasma Viral loads, Peripheral Blood CD4+ T cell counts and Jejunal Mucosa CD4+ T cell % in SIV infected animals and SIV negative controls.

(A) SIV RNA positive cells were widely disseminated through the mucosa, but were clustered in villus and Peyer's patches (open arrows). Few SIV-infected cells were found in the lamina propria surrounding crypt bases (solid arrows). (B) Animals in the chronic stage of SIV infection had lower viral loads than during the primary stage (set point). PMPA significantly reduces viral loads in infected macaques. (C) SIV infection reduces CD4+ T cell numbers in peripheral blood (D) A dramatic loss of CD4+ T cells were observed in all stages of infection compared to uninfected controls. Incomplete CD4+ T cell restoration observed in both PBMC and LPL. * Indicated significant differences between groups.

Figure 4. Detection of RED RNA expressing cells and SIV-infected cells in intestinal mucosa of SIV infected rhesus macaques.

Serial sections of intestinal tissues were analyzed by in situ hybridization using DIG-labeled SIV gag-specific riboprobes or RED-specific riboprobes. Serial sections from a chronically infected animal (A) showed no evidence of SIV-infected lymphocytes (left), but RED expression (right) was abundant at base of the crypts. Intestinal tissue from a fast-progressor/SAIDS animal (B) showed SIV-infected lymphocytes throughout the tissue (left) and, abundance of RED expression (right) at the base of the crypt. SIV-infected cells were clustered in Peyer's patches and/or upper lamina propria and epithelial layers (solid arrows), but were mostly absent from lower crypt epithelium or the area surrounding the base of the crypts (open arrows).

Viral burden in jejunal mucosa from 26 animals was measured by real-time RT-PCR. In concordance with the ISH findings, highest levels of SIV burden were found during primary and advanced stages of disease while, a reduction in the viral burden was noted during chronic SIV infection (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Analysis of plasma samples from 17 animals by real-time RT-PCR showed that plasma viral loads correlated with tissue viral burden, with the highest levels seen during primary and SAIDS stages of infection and decreased burden during chronic SIV infection and ART (Fig. 1). As previously demonstrated CD4+ T cell depletion was observed in peripheral blood and was dramatically evident in GALT (Fig. 1)(21).

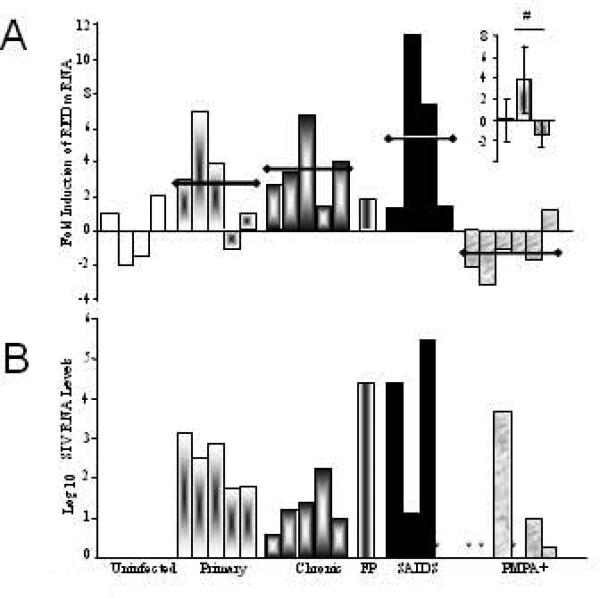

Figure 2. Analysis of RED expression in gut mucosa of SIV infected rhesus macaques.

Levels of RED mRNA (A) and SIV Gag RNA (B) were determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis from intestinal tissues. Values were normalized to endogenous housekeeping GAPDH RNA and calibrated against the average of values from SIV-negative controls (RED) or to the lowest detectable value (SIV). Insert shows RED mean values for uninfected, SIV+/PMPA- and SIV+/PMPA+ animals. * indicates undetectable levels of SIV RNA in tissue samples. # indicates p<0.05

Increased expression of RED and Paneth cell numbers in response to SIV infection

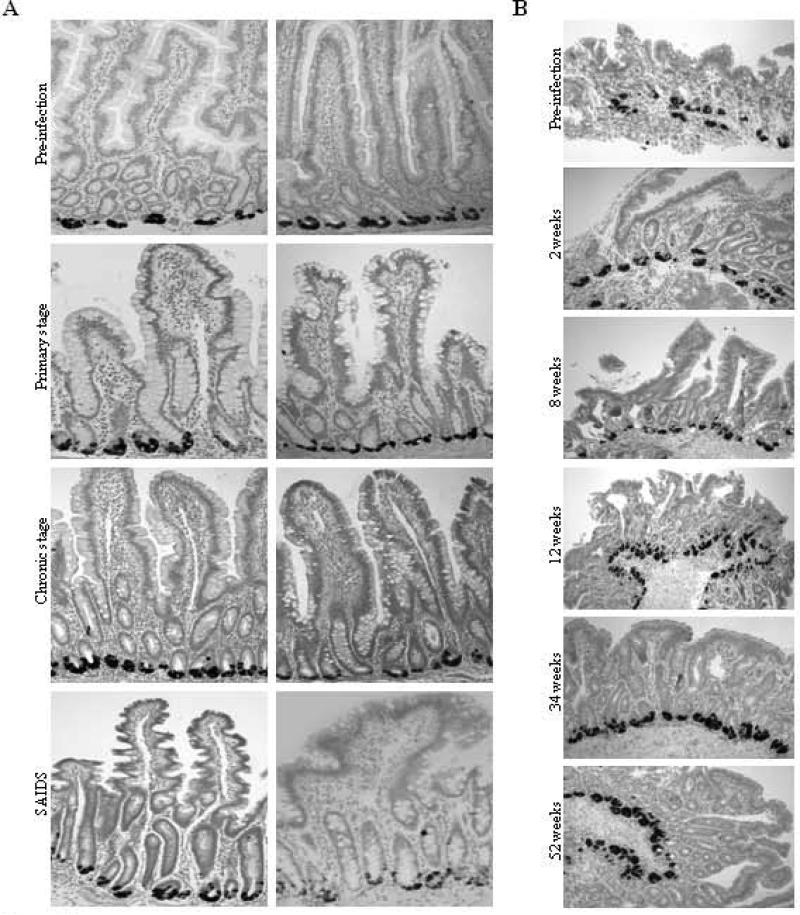

The location of RED mRNA expressing cells, performed by ISH, was restricted to the base of crypts and they were identified morphologically as Paneth cells (PC) based on presence of apical granules, basal nucleus and pyramidal shape (Fig. 3A) (22). Longitudinal analysis of jejunal biopsy samples from six SIV infected animals detected expression of RED mRNAs throughout the course of SIV infection (Fig. 3B). Our results indicated that RED mRNA was expressed in approximately 98% of crypts in the jejunal mucosa of healthy uninfected animals and not significantly changed through the course of SIV infection (Fig. 6F). Variation in the intensity of RED immunoreactivity did not correlate with stage of disease or viral burden.

Figure 3. Expression of rhesus enteric defensin RNA in gut mucosal Paneth cells from SIV-infected rhesus macaques.

(A) RED RNA was detected in intestinal tissues in SIV-negative controls and SIV-infected animals. (B) RED mRNA was detected in longitudinal intestinal biopsy samples obtained from the animal 25007 prior to SIV infection and at time points during primary (2 weeks), chronic (8, 12 and 34 weeks) and SAIDS (52 weeks) stages of SIV infection. Samples were analyzed for the expression of RED RNA by in situ hybridization using a DIG-labeled RED-specific riboprobe.

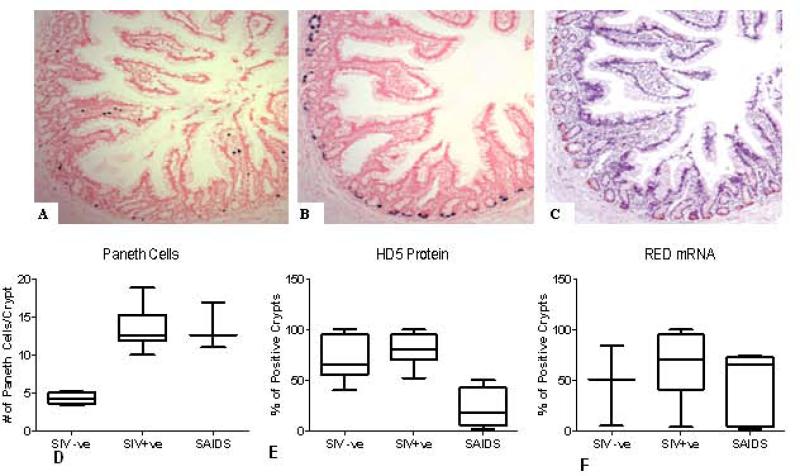

Figure 6. Localization of RED mRNA and protein in gut mucosa of SIV-infected rhesus macaques.

Serial sections from intestinal tissue were analyzed by in situ hybridization to detect SIV gag RNA (A) and RED mRNA (B) and by immunohistochemistry using HD-5 antiserum to detect RED protein (C). SIV positive cells are clustered in villus tips and Peyer's patches. RED mRNA was present in Paneth cells from >95% of the crypts. RED protein expression paralleled that of RED mRNA expression in tissues analyzed from SIV-negative animals and SIV-infected animals during primary or chronic stage of infection, as well as in PMPA-treated animals. (D) Increased Paneth Cell numbers in crypts of SIV infected animals. Paneth Cells were identified in jejunal mucosal sections from 16 animals. An increase in the number of cells were observed following SIV infection(n=12) as compared to SIV negative (n=4) animals. * indicated p<.05. (E): A decrease in HD5+ crypts was observed in SAIDS (n=4) compared to SIV+ chronic asymptomatic animals (n=9) and SIV negative animals (n=4) . (F): No difference was observed in the percentage of RED mRNA positive crypts during the course of SIV infection

Quantification of RED mRNA levels in gut mucosa demonstrated an increased expression of RED transcripts in SIV-infected, therapy-naive animals during primary (mean 2.8 fold increase), chronic (mean 3.7 fold increase), or SAIDS (mean 4.7 fold increase) stages of infection, as compared to uninfected controls (Fig. 2). A significant increase in RED expression was seen in SIV-infected, therapy-naive macaques as compared to uninfected controls and PMPA treated animals (p<0.04; Fig. 2), and was associated with an increased number of PC per jejunal crypt (Fig. 6D). Examination of H&E stained gut tissue sections detected an average of 5 PC per crypt in SIV-negative controls whereas SIV infected animals had 10, 12, and 14 PC per crypt during primary, chronic and SAIDS stages of infection, respectively. Collectively, our data suggested that SIV infection led to an increase in RED gene expression and expansion of PC numbers in jejunal mucosa that remained elevated throughout the course of SIV infection, independent of the magnitude of viral burden within the gut mucosal tissue.

Decreased RED protein levels correlate with enteric opportunistic infections and advanced SIV disease

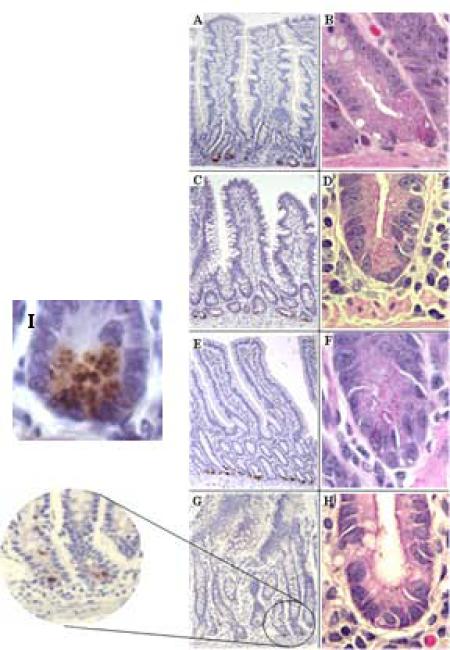

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis was performed to determine the cellular localization of RED proteins. RED proteins were detected in jejunal tissues from uninfected and SIV-infected animals during the primary and chronic stages of infection, as well as in the LTNP animal (92% RED-positive crypts) (Fig. 5 E, F, G and H). Immunohistochemical analysis showed a reduction of RED protein levels in PC in SAIDS animals, including the animal with rapid disease progression (Fig. 5G and H). The percentage of RED+ crypts did not differ between SIV-ve control animals and SIV+ asymptomatic animals. However, a sharp decline in the % of RED+ crypts was observed in animals with SAIDS (Fig. 6E).

Figure 5. Expression of RED protein and presence of eosinophilic granules in gut mucosal Paneth cells during SIV infection.

RED protein was detected by immuno-histochemistry using HD-5 antibody (left column). Eosinophilic secretory granules were visualized by conventional H&E staining (right column). Intestinal tissues were collected from SIV-negative controls (A and B) and macaques during primary (C and D), chronic (E and F) and SAIDS (G and H) stages of SIV infection. Localization of immuno-reactivity within Paneth cell granules (I).

Although the primary structure of HD-5 differs greatly from known RED peptide sequences, a short region of highly conserved sequence identity exists between RED4, RED8 and HD5, shown as underlined, bold residues in the HD-5 sequence: ATCYCRTG RCATRESLSG VCEISGRLYR LCCR. The shared CRTGRC could be an epitope shared by these REDs that is recognized by anti-HD-5 antibody. The defensin immunoreactivity in the lumen appeared to be increased in the animals with SAIDS, as compared to gut tissues from SIV-negative control animals and in animals with primary or chronic SIV infection, or SIV infected animals receiving ART. The number of PC in the crypts of animals with SAIDS remained unchanged (Fig. 6D). There was no corresponding immunoreactivity in the antibody negative controls, suggesting that defensin immunoreactivity might represent defensin protein in lumen (Fig. 5G/H). Mucosal tissue was also evaluated for the presence of granules to determine the extent of degranulation in the PC during the course of SIV infection. Very few eosinophilic granules could be detected in PC in jejunal tissue samples from SAIDS animals as compared to uninfected controls and animals during primary or chronic SIV infection (Fig. 5 and Fig 6E).

Serial gut tissue sections examined for either RED mRNA or protein, or SIV RNA demonstrated that RED protein was localized to dense granules and RED mRNA to the cytoplasm of corresponding cells in tissues from all animals. SIV RNA was not detected in PC suggesting that PC did not support viral replication. A representative example of RED expression in an SIV infected animal during primary acute stage of infection with high viral burden is shown (Fig. 6).

Advanced SIV disease was marked by a significant loss of RED protein in PC that coincided with an increase in the incidence of bacterial and protozoal infections (Table 1). The infections included Fusobacterium, Bacteroides, alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus, Streptococcus viridans, coagulase-negative/positive Staphylococci, Corynebacterium, Pseudomonas maltophilia, Iodamoeba butschlii, Peptostreptococcus, and Lactobacillus species, each of which was found in one or more animals. Pentatrichomonas hominis was the most prevalent pathogen in SAIDS animals (7/7) despite treatment of five of these animals with metronidazole. There was a significant association with the loss of RED protein and the presence of Trichomonas infection of the large intestine in animals with SAIDS (p=<0.0004). Blastocystis hominis was the second most common infection (5/7). This incidence may have been due to the ineffectiveness of most anti-protozoal medications against the organism. Entamoeba coli and Campylobacter were the third most prevalent pathogens in SAIDS animals (4/7). Entamoeba coli are typically nonpathogenic, even in people with impaired immune functions. However, a breakdown of mucosal epithelium may enable its entry and colonization. Animals with SAIDS, including the RP animal, had 8 or more secondary infections and had non-responsive, recurrent diarrhea even after metronidazole therapy. Two of these animals had high viral burden (ISH score=5), but one animal had a very low viral burden (ISH score=1).

Two animals with primary SIV infection had three or more secondary infections. The presence of RED protein in the PC of these animals was similar to that seen in uninfected animals. A high incidence of Campylobacter jejuni or C. coli was seen during the primary acute stage of infection, but was not evident during chronic SIV infection. Specific immunity, involving intestinal immunoglobulin (IgA) and systemic antibodies, is required for healthy animals to control Campylobacter infection. The pro-inflammatory environment and eventual breakdown of the mucosal epithelial barrier during SAIDS could pre-dispose animals to recurrence of Campylobacter infection due to entry and colonization.

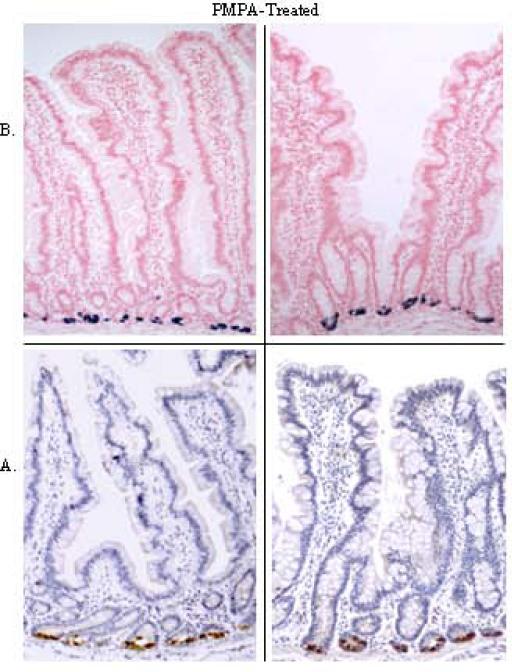

Antiretroviral therapy led to suppression of SIV replication and maintenance of enteric defensin expression

We evaluated the effect of antiretroviral therapy (ART) on viral replication and expression of RED peptides during SIV infection. The ART led to suppression of SIV loads in peripheral blood and in gut mucosal tissues (Table 1). Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization analyses detected the expression of RED mRNA and protein in gut tissue samples from all SIV-infected animals receiving ART (Fig. 7). However, quantitative analysis of RED mRNA expression by real time PCR showed that animals receiving ART had significantly decreased RED mRNA levels compared to therapy-naive SIV-infected animals but similar to SIV-negative control animals (1.6 fold decrease, p<0.0003) (Fig. 2). Our data showed that viral suppression induced by ART of SIV-infected monkeys might lead to the maintenance of RED protein expression that is comparable to uninfected healthy controls and better protection against enteric microbial infections. Thus, prevention of the loss of RED expression in the gut mucosa of these animals during ART would contribute to effective innate immunity at the mucosal site.

Figure 7. Localization of RED mRNA and protein in mucosa of SIV-infected rhesus macaques receiving PMPA therapy.

Expression of RED protein (A) and mRNA (B) was detected in intestinal tissues from SIV-infected, PMPA-treated animals. Representative samples shown, were obtained from four animals that began therapy at 6 to 10 weeks post-SIV infection.

DISCUSSION

One of the most common causes of mortality among ART-naïve, HIV-infected individuals is the incidence of opportunistic infections. The innate immunity plays an important role not only during the initial stages of HIV infection, prior to the development of a virus-specific adaptive immune response, but also throughout the course of infection by protecting the host against various pathogens. Our study examined the role of mucosal innate defense in HIV infection by analyzing changes in the expression of rhesus enteric α-defensins in gut mucosa of SIV infected rhesus macaques in the context of viral replication and CD4+ T cell depletion. Our findings showed an increased level of RED gene expression associated with Paneth cell hyperplasia at all stages of SIV infection in therapy-naïve SIV infected animals. This suggests that REDs may be an important component of the gut mucosal innate immune defense that persists through primary and chronic stages of SIV infections.

Several mechanisms may contribute to the upregulation of REDs in the PC during SIV infection and their loss during the advanced stages of infection. Severe loss of CD4+ T-cells including CD4+ Th17 cells in gut mucosa during primary HIV and SIV infections has been well documented (15, 23). This CD4+ T cell loss is not reversed despite the development of virus-specific humoral and cellular responses (3). The immediate and long-term impact of mucosal CD4+ T-cells is not fully defined. It has been demonstrated that SIV induced loss of CD4+ Th17 T-cell loss in gut mucosa of SIV infected rhesus macaques led to impaired Th17 CD4+ T-cell responses to the Salmonella typhimurium infection in the gut mucosa and resulted in increased systemic bacterial translocation (24). Thus, the gut mucosal CD4+ T-cell depletion may lead to incomplete control of enteric pathogens and increased microbial translocation from the lumen. An increase in the RED gene transcription may be a mechanism by which the host mucosal response contains the microbial burden. It is also reasonable to propose that increased RED expression may partly compensate for the immune defects generated in the gut mucosa by SIV infection. While the number of REDs in rhesus macaque PCs far outnumber that in human PCs, identification of individual defensins are beyond the scope of this study. Their anti-microbial and anti-viral activity may be crucial in providing protection to crypt epithelial progenitor cells as well as T cells in the neighboring regions. Further characterization of PC derived RED peptides will be important to gain better understanding of the PC mediated mucosal innate defense.

Increased microbial translocation due to the breakdown of the gut epithelial barrier in SIV infection may also impact the enteric defensin gene expression and peptide levels and warrants further investigation. Disruption of the integrity of the intestinal epithelium in HIV and SIV infections has been well documented that is linked to decreased nutrient digestion and malabsorption and increased microbial translocation (24-25). Increased expression of genes associated with inflammation and immune activation in the gut mucosa during HIV and SIV infections has been reported (21). Histopathologic changes of villus atrophy and crypt hyperplasia along with the mucosal CD4+ T cell loss may contribute to mucosal inflammation and inability to control microbial burden. Our findings of increased PC numbers in the gut mucosa suggest that the impairment or loss of adaptive immune responses and the integrity of the villus epithelial barrier secondary to SIV infection may result in the need for a compensatory increase in crypt innate responses resulting in expansion of the PC compartment. In the mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease, gut mucosal inflammation and disruption of PC homeostasis with hyperplasia have been reported that were associated depletion of PC gene products and secretory granules (26). Anti-retroviral therapy is effective in suppressing viral loads and reducing inflammation in the gut mucosa. We found that animals receiving ART had RED expression comparable to the uninfected controls and low, to almost no incidence of opportunistic infections in the GI tract as compared to untreated animals, indicative of better mucosal immune functions (27). It is possible that this may reduce PC secretion of innate proteins, thus preventing the exhaustion of this mucosal innate immune response. Previous studies have demonstrated that interruption of ART in SIV infected animals led to a rapid loss of GALT CD4+ T cells and increased viral loads similar to that seen in primary SIV infection (28). While our study was not designed to investigate these effects, it suggests that therapy interruption may result in increased opportunistic infections as seen in untreated SIV infection resulting increased RED expression following increased degranulation.

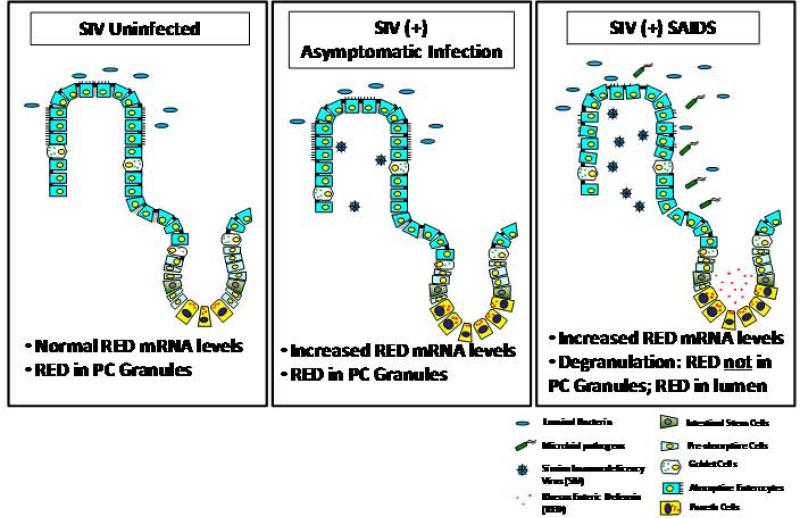

We found a loss of intestinal Paneth cell granules and detection of RED protein in SIV-infected animals with SAIDS which was accompanied by increased immunostaining in the lumen of jejunal tissues, suggesting high levels of secretion of REDs into lumen (Fig. 8). Loss of PC defensin expression through increased degranulation was previously observed in the small intestine of HIV-infected patients with AIDS (29). The loss of defensins in PC during SAIDS may be attributed to the release of the granules. Furthermore, the loss of RED protein in animals with SAIDS did not correlate with viral burden but rather with the advanced stage of disease. An animal that had a rapid SIV disease course of 12 weeks showed a loss of RED protein expression. Increased bacterial burden may cause rapid degranulation and loss of RED protein from PC in advanced SIV infection. Increased bacterial burden may cause rapid degranulation and loss of RED protein from PC in advanced SIV infection. It is also possible that the RED peptide biosynthesis may not sustain the loss of RED protein due to the increased bacterial load in the gut mucosa. A strong association between the loss of RED protein and incidence of Trichomonas infection in the large intestine was noted. Studies have shown that α-defensins are variably effective against eukaryotic pathogens, depending on their primary structures and may play a role in the maintenance of a normal microenvironment in the small intestine (10, 30). PC-derived α-defensins determine the composition of the mouse small intestinal microbiome, and disruption of PC secretion could alter the resident microflora by increasing susceptibility to opportunistic colonizers (10). Loss of this protection might have enabled increased numbers of Trichomonas to colonize in the intestine of SAIDS animals.

Figure 8.

Model of rhesus enteric α-defensin alterations in SIV-infection.

In summary, the loss of enteric defensins in simian AIDS is associated with physiological exhaustion of the regulated biosynthetic secretion pathway of PC, which may be prevented by viral suppressive and immunomodulatory therapies. Future studies are needed to determine the mechanism of the loss of REDs in SAIDS, as well as how this loss affects disease progression. Our study showed that PC derived enteric defensins may play an important role in mucosal defense by providing anti-microbial functions and protecting the gut mucosa against infections. Further studies of α-defensins may help develop strategies to exploit innate defense molecules for effective control of secondary enteric infections in HIV infected patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Alice Quayle for rhesus macaque defensin cDNA , Dr Charles Brown for the SIV riboprobe, Dr Charles Bevins and Dr Jarold Theis for their advice and Neil Willits for the statistical analysis. We appreciate the technical support from Linda Hirst and veterinary staff at the California National Primate Research Center.

This study was supported by the grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI43274 and DK43183).

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenson JK, Belitsos PC, Yardley JH, Bartlett JG. AIDS enteropathy: occult enteric infections and duodenal mucosal alterations in chronic diarrhea. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:366–372. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rene E, Marche C, Regnier B, Saimot AG, Vilde JL, Perrone C, Michon C, Wolf M, Chevalier T, Vallot T, et al. Intestinal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. A prospective study in 132 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:773–780. doi: 10.1007/BF01540353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guadalupe M, Reay E, Sankaran S, Prindiville T, Flamm J, McNeil A, Dandekar S. Severe CD4+ T-cell depletion in gut lymphoid tissue during primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and substantial delay in restoration following highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2003;77:11708–11717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11708-11717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heeney JL. The critical role of CD4(+) T-cell help in immunity to HIV. Vaccine. 2002;20:1961–1963. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy JA. HIV pathogenesis: knowledge gained after two decades of research. Adv Dent Res. 2006;19:10–16. doi: 10.1177/154407370601900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevins CL. Events at the host-microbial interface of the gastrointestinal tract. V. Paneth cell alpha-defensins in intestinal host defense. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G173–176. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00079.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llenado RA, Weeks CS, Cocco MJ, Ouellette AJ. Electropositive charge in alpha-defensin bactericidal activity: functional effects of Lys-for-Arg substitutions vary with the peptide primary structure. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5035–5043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00695-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones DE, Bevins CL. Paneth cells of the human small intestine express an antimicrobial peptide gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23216–23225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanabe H, Yuan J, Zaragoza MM, Dandekar S, Henschen-Edman A, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell alpha-defensins from rhesus macaque small intestine. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1470–1478. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1470-1478.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, Chu H, Karlsson-Sjoberg J, Amir E, Teggatz P, Barman M, Hayward M, Eastwood D, Stoel M, Zhou Y, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Bevins CL, Williams CB, Bos NA. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol. 11:76–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz T. Paneth cells--guardians of the gut cell hatchery. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:99–100. doi: 10.1038/77884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell alpha-defensins: peptide mediators of innate immunity in the small intestine. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;27:133–146. doi: 10.1007/s00281-005-0202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Agostino C, Lichtner M, Mastroianni CM, Ceccarelli G, Iannetta M, Antonucci S, Vullo V, Massetti AP. In vivo release of alpha-defensins in plasma, neutrophils and CD8 T-lymphocytes of patients with HIV infection. Curr HIV Res. 2009;7:650–655. doi: 10.2174/157016209789973600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapata W, Rodriguez B, Weber J, Estrada H, Quinones-Mateu ME, Zimermman PA, Lederman MM, Rugeles MT. Increased levels of human beta-defensins mRNA in sexually HIV-1 exposed but uninfected individuals. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6:531–538. doi: 10.2174/157016208786501463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heise C, Vogel P, Miller CJ, Halsted CH, Dandekar S. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of the gastrointestinal tract of rhesus macaques. Functional, pathological, and morphological changes. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1759–1771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smit-McBride Z, Mattapallil JJ, McChesney M, Ferrick D, Dandekar S. Gastrointestinal T lymphocytes retain high potential for cytokine responses but have severe CD4(+) T-cell depletion at all stages of simian immunodeficiency virus infection compared to peripheral lymphocytes. J Virol. 1998;72:6646–6656. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6646-6656.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smit-McBride Z, Mattapallil JJ, Villinger F, Ansari AA, Dandekar S. Intracellular cytokine expression in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from intestinal mucosa of simian immunodeficiency virus infected macaques. J Med Primatol. 1998;27:129–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1998.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CC, Follis KE, Sabo A, Beck TW, Grant RF, Bischofberger N, Benveniste RE, Black R. Prevention of SIV infection in macaques by (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine. Science. 1995;270:1197–1199. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George MD, Reay E, Sankaran S, Dandekar S. Early antiretroviral therapy for simian immunodeficiency virus infection leads to mucosal CD4+ T-cell restoration and enhanced gene expression regulating mucosal repair and regeneration. J Virol. 2005;79:2709–2719. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2709-2719.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leutenegger CM, Higgins J, Matthews TB, Tarantal AF, Luciw PA, Pedersen NC, North TW. Real-time TaqMan PCR as a specific and more sensitive alternative to the branched-chain DNA assay for quantitation of simian immunodeficiency virus RNA. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:243–251. doi: 10.1089/088922201750063160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George MD, Sankaran S, Reay E, Gelli AC, Dandekar S. High-throughput gene expression profiling indicates dysregulation of intestinal cell cycle mediators and growth factors during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Virology. 2003;312:84–94. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh I. The distribution of Paneth cells in the human small intestine. Anat Anz. 1971;128:60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heise C, Miller CJ, Lackner A, Dandekar S. Primary acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection of intestinal lymphoid tissue is associated with gastrointestinal dysfunction. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1116–1120. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raffatellu M, Santos RL, Verhoeven DE, George MD, Wilson RP, Winter SE, Godinez I, Sankaran S, Paixao TA, Gordon MA, Kolls JK, Dandekar S, Baumler AJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus-induced mucosal interleukin-17 deficiency promotes Salmonella dissemination from the gut. Nat Med. 2008;14:421–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, Kazzaz Z, Bornstein E, Lambotte O, Altmann D, Blazar BR, Rodriguez B, Teixeira-Johnson L, Landay A, Martin JN, Hecht FM, Picker LJ, Lederman MM, Deeks SG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:1365–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao F, Edwards R, Dizon D, Afrasiabi K, Mastroianni JR, Geyfman M, Ouellette AJ, Andersen B, Lipkin SM. Disruption of Paneth and goblet cell homeostasis and increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in Agr2−/− mice. Dev Biol. 338:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ullrich R, Heise W, Bergs C, L'Age M, Riecken EO, Zeitz M. Effects of zidovudine treatment on the small intestinal mucosa in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1483–1492. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lori F, Lewis MG, Xu J, Varga G, Zinn DE, Jr., Crabbs C, Wagner W, Greenhouse J, Silvera P, Yalley-Ogunro J, Tinelli C, Lisziewicz J. Control of SIV rebound through structured treatment interruptions during early infection. Science. 2000;290:1591–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly P, Feakins R, Domizio P, Murphy J, Bevins C, Wilson J, McPhail G, Poulsom R, Dhaliwal W. Paneth cell granule depletion in the human small intestine under infective and nutritional stress. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02374.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aley SB, Zimmerman M, Hetsko M, Selsted ME, Gillin FD. Killing of Giardia lamblia by cryptdins and cationic neutrophil peptides. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5397–5403. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5397-5403.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]