Abstract

Using the 2001 Survey of Income and Program Participation, the current study examines poverty and material hardship among children living in 3-generation (n = 486), skipped-generation (n = 238), single-parent (n = 2,076), and 2-parent (n = 6,061) households. Multinomial and logistic regression models indicated that children living in grandparent-headed households experience elevated risk of health insecurity (as measured by receipt of public insurance and uninsurance)—a disproportionate risk given rates of poverty within those households. Children living with single parents did not share this substantial risk. Risk of food and housing insecurity did not differ significantly from 2-parent households once characteristics of the household and caregivers were taken into account.

Keywords: family structure, grandparents/grandparenthood, intergenerational relations, multigenerational relations, poverty

The influence of living arrangements on economic hardship in childhood has been widely documented, particularly the disadvantages associated with living in single-mother households. Less attention has been paid to the economic security of children living in the home of a grandparent (i.e., grandparent-headed households). As of 2004, nearly 4.6 million children were living in grandparent-headed households in the United States, either in three-generation (grandparent and grandchild in addition to one or both parents) or skipped-generation (grandparent and grandchild in the absence of both parents) households. Nearly one fourth of those children live below the poverty line (Kreider, 2008). Children living in skipped-generation households are particularly at risk, as nearly one third of them live below the poverty line.

Moreover, a paucity of research documents the ability of such households to meet the basic needs of resident children. The formation of grandparent-headed households is often unexpected, is fluid and informally arranged, and is characterized by a lack of recognition by federal, state, and local policy. Accordingly, conventional income-based measures of economic deprivation alone may not sufficiently capture the scope of hardship experienced by children in grandparent-headed households. Given the link between material deprivation and poor developmental outcomes among children (see Alaimo, Olson, & Frongillo, 2001; Gershoff, Aber, Raver, & Lennon, 2007; Yoo, Slack, & Holl, 2009), it is essential to document the experience of material hardship for children in this increasingly common household structure.

Using the 2001 Survey of Income and Program Participation, we examine reports of poverty and material hardship (specifically health insecurity, housing insecurity, and food insecurity), for children living in three-generation and skipped-generation grandparent-headed households as well as children living in households headed by single parents and by two parents. We investigate the extent to which living in a grandparent-headed household is associated with elevated rates of poverty and material hardship among children, controlling for the demographic composition of the household and for the labor force participation and disability of caregivers. We also explore the extent to which the association between poverty and material hardship varies depending on the generational structure of the household. This contributes to current literature by identifying groups of children living in households above traditional poverty cutoffs who are nevertheless at risk of material hardship.

The Changing Nature of Grandparenthood

Grandparents have long played an integral role within families, providing support and assistance when needed but otherwise forming part of the latent kin network awaiting activation (Riley & Riley, 1993). Recent findings suggest that a growing number of grandparents are being “activated” in this regard. The number and percentage of children living in grandparent-headed households has doubled in the United States from 2.2 million, or more than 3% of all children in 1970 (Casper & Bryson, 1998), to 4.6 million children, or more than 6% of all children in 2004 (Kreider, 2008).

This increase has been attributed both to societal trends, such as the rise in teenage pregnancy, single-parent households, and the AIDS and crack-cocaine epidemics, and to policy changes, such as the identification of grandparents as a preferable placement in the child welfare system and the steep rise in female incarceration rates due to nonviolent drug offenses and mandatory minimum sentencing (Minkler, 1999). In 2004, approximately 2.1% of children in the United States lived in a skipped-generation household (Kreider, 2008). The majority of children living in grandparent-headed households lived in three-generation households containing both a grandparent and at least one parent. In 2004, approximately 4.1% of children in the United States lived in that arrangement, most commonly with a single mother (Kreider, 2008). Parents in such households are disproportionately never married or divorced and often rely on the grandparent for financial support, either partially or entirely (Mutchler & Baker, 2009).

Children in grandparent-headed households are especially likely to display behavioral and emotional problems because of the events leading up to the move into the grandparent’s home, including economic crises, family conflict, neglect or abuse, and separation from one or both parents. High rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; depression; anxiety; and developmental, emotional, and behavioral problems have been observed in this population partially because of high rates of alcohol and drug abuse in utero (Bramlett & Blumberg, 2007). Thus, although the proportion of children living in grandparent-headed households in the United States is relatively low compared to other family structures, the welfare of those children is particularly important, as they are at risk of experiencing severe developmental problems.

Poverty and Material Hardship

There is little agreement regarding how much income is required for a family to avoid serious hardship. Indeed, income is often not an adequate indicator of the resources or hardship of a family, because of misreporting, differences across families in expenses, and other factors (Mayer, 1997). The most widely used indicator of economic hardship in the United States, the poverty threshold, is routinely criticized for offering an inadequate and partial assessment of disadvantage (Citro & Michael, 1995). When examining the experience of economic hardship, it is important to examine indicators of material hardship in addition to income-based measures of poverty, as there is not a direct association between level of poverty and material hardship. Although these measures are associated with poverty status and its determinants, they capture additional elements of hardship beyond poverty itself. In fact, a family’s income-to-needs ratio has been shown to explain less than one fourth of the variation in reports of material hardship (Mayer & Jencks, 1989).

Material hardship is a multidimensional concept encompassing several types of hardship that may be missed by examining income-based measures of hardship alone. Of particular importance are measures of health, housing, and food security, as these constructs represent basic needs that are essential to the well-being of children, the lack of which have been linked to negative developmental outcomes for children, including poor health, behavioral issues, and poor school performance (Alaimo et al., 2001; Gershoff et al., 2007; Yoo et al., 2009). Material hardship among children is largely shaped by the characteristics of their household and caregivers. The gender, race and/or ethnicity, age, education, marital status, labor force participation, and health of caregivers, as well as the number and age of children in the household, have all been associated with the likelihood of experiencing material hardship (Manning & Brown, 2006; Mayer & Jencks, 1989). Given that the characteristics of caregivers and the composition of grandparent-headed households differ dramatically from that of parent-headed households, it stands to reason that the risk of material hardship may differ depending on the generational structure of the household.

Factors Contributing to Poverty and Material Hardship Within Grandparent-Headed Households

As mentioned previously, grandparent-headed households have disproportionately high rates of poverty. It is unclear to what extent this is associated with the compositional features of the household. In other words, do grandparent-headed households face unique barriers in securing adequate income and fulfilling the material needs of coresident children? Or are rates of poverty and material hardship no higher than would be expected given the characteristics of adults in the household? In this section, we outline several factors that may be associated with higher poverty and material hardship in grandparent-headed households, including (a) the demographic composition of the households, (b) the low labor force participation and higher rates of disability of caregivers, and (c) the unexpected, fluid, and informal care arrangements in grandparent-headed households.

The Demographic Composition of Grandparent-Headed Households

Single female members of racial and ethnic minority groups with low educational attainment disproportionately head grandparent-headed households (Fuller-Thomson, Minkler, & Driver, 1997). This living arrangement is particularly common in the African American community, given historically high rates of poverty and single parenting and a long tradition of extended living arrangements as a way to pool both financial and caregiving resources (Jimenez, 2002). Grandparent-headed households tend to include younger children—often of preschool age—and older heads of household, which shape the dependency ratio of these households (Casper & Bryson, 1998). Each of these factors influences the resources available to children in the household and thus may shape poverty and material hardship.

Labor Force Participation and Disability of Caregivers in Grandparent-Headed Households

Further, because of their age and stage in the life course, grandparents may be less able than parents to adjust to the changing financial needs of coresident children. Income meant to support one or two older adults suddenly must fulfill the needs of coresident grandchildren and, in some cases, adult children. This is particularly true for those grandparents who previously exited the labor force by retirement and who rely on fixed incomes. Further, grandparents may be less able than parents to either return to work or to make adjustments in current work hours because of a greater likelihood of health limitations and disability than for parents. Such factors may inhibit the ability of caregivers in grandparent-headed households to adapt financially to the needs of coresident children.

Unexpected, Fluid, and Informally Arranged Care in Grandparent-Headed Households

Insofar as the formation of multigenerational households is often unexpected and sudden, caregivers in grandparent-headed households may not have the resources in place to adequately care for coresident children. Even an unexpected pregnancy will leave parents with 9 months of preparation; the formation of grandparent-headed households (particularly in cases of parental abuse or abandonment) may occur with little or no prior notice. Further, such care arrangements are often fluid and transitory (Lee, Ensminger, & LaVeist, 2005); if caregivers in grandparent-headed households see the arrangement as temporary, they may be reluctant to make drastic changes designed to meet the needs of coresident children (e.g., moving to a more affordable house or apartment).

These barriers are especially salient for grandparents living with grandchildren in skipped-generation households, but they may also be a problem for grandparents who head three-generation households. A sudden transition into a three-generation household may be associated with divorce, teen pregnancy, or sudden economic strain (e.g., job loss) in the parent generation. Thus, grandparents in three-generation households may be financially responsible for all generations in the household. Further, parents in three-generation households may be only a temporary addition to a formerly skipped-generation household, in which case the grandparent is the only continuous parental influence in the household. Finally, adults in three-generation households may intentionally maintain distinct subfamilies within the larger household context—particularly in cases of impermanence—which leads to an uneven distribution of resources in the household. A lack of resource pooling between grandparents, parents, and grandchildren may contribute to variations in the association between reports of poverty and material hardship as compared to parent-headed households.

Even in cases where the care is more permanent, grandparents often do not seek custody and have no formal legal relationship with the grandchild. This may affect a family’s eligibility for tax credits or employer provided parental benefits (e.g., subsidized day care, paid leave for family care). Grandparents who are below the poverty line may be eligible for Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF); unfortunately, the strict eligibility requirements imposed through welfare reform may be prohibitive for grandparent-headed households. Grandparents who receive such benefits are subject to work requirements and time limits on assistance (Cox, 2009). For grandparents who have already exited the labor force or who are disabled, work requirements may be unreasonable. In addition, grandparents who received benefits while raising their own children may be ineligible to receive funding to raise their grandchildren if they have previously exceeded the 60-month time limits imposed by welfare reform (Smith & Beltran, 2003). Grandparents, even those above the poverty line, may choose to apply for TANF child-only grants, which do not have these strict requirements; however; those benefits are quite low in comparison with benefits provided to the full family (Smith & Beltran, 2003). In addition, even those families that meet eligibility requirements may not receive benefits because they are either unaware of their eligibility for grants or incorrectly denied benefits by caseworkers unfamiliar with their unique situation (Cox, 2009).

Because health insurance benefits in the United States are obtained primarily through the employer of a child’s parent or guardian, grandparents are especially likely to face barriers with regard to health insurance (Casper & Bryson, 1998). Grandparents may be forced to purchase a prohibitively expensive private policy for their grandchild, as most insurance companies do not recognize a coresident grandchild as a dependent unless a formal legal relationship has been established (Generations United, 2002). This forces a disproportionate number of children in grandparent-headed households into the public insurance system. Many states have recognized this problem and have less restrictive eligibility requirements for children living with grandparents, particularly with regard to income limitations. Unfortunately, grandparents—particularly those with higher incomes—may be unaware of this eligibility, leaving even children who are eligible for public insurance at risk of being uninsured (Jendrek, 1994). A lack of health insurance has been associated with poor health care access and unmet health care needs among children (Olson, Tang, & Newacheck, 2005). Further, both public insurance and a lack of insurance have been linked to high rates of morbidity and mortality in childhood (Todd, Armon, Griggs, Poole, & Berman, 2006).

Current Investigation

We explore two distinct questions in the current investigation. First, are children who live in grandparent-headed households at increased risk of poverty and material hardship, in and above that which the characteristics of their household and caregivers would predict? We propose that reports of hardship will be higher in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent families than in two-parent families. To test this hypothesis, we ran a series of binary and multinomial logistic regression models to assess the association between generational structure of the household and each type of economic and material hardship; we added covariates in stages to control for a range of social indicators associated with generational structure (including the demographic composition of the household and the labor force participation and disability of caregivers). We expect that the association between generational structure and material hardship will remain strong for three-generation and skipped-generation households, even after controlling for those constraints, given the unique barriers such households face, an effect that will not be shared for children living with single parents.

Second, does the association between poverty and material hardship vary depending on the generational structure of the household? We propose that the unexpected nature of care; the fluidity and informality of care arrangements; and the resultant lack of recognition by federal, state, and local policy place children in three-generation and skipped-generation households at increased risk of experiencing material hardship even in households whose financial resources would place them above the poverty level. Further, these variations will be larger for types of material hardship associated with greater expense and/or less concrete and immediate consequences. Therefore, we expect that the association between poverty status and health security will be quite weak in grandparent-headed households compared to two-parent households. The cost of securing a private plan outside the employer-based system is prohibitively expensive. Further, many grandparents who fail to purchase insurance for a grandchild will experience few direct consequences, at least in the short term, as most children are in relatively good health and require few significant medical expenditures. Alternatively, the consequences of failing to pay rent or a mortgage will invariably lead to direct consequences, possibly even eviction. Given the comparatively low cost of food and the severe and immediate consequences of failing to provide food for the household, we do not expect that the association between poverty status and food security will vary strongly by generational structure of the household. To test this hypothesis, we ran a series of binomial and logistic regression models, adding interaction terms (Poverty × Generational Structure) to determine whether the association between poverty and material hardship varies depending on the generational structure of the household.

Method

This research used the 2001 Panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The SIPP is a nationally representative, longitudinal survey of households conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Wave 8 of the 2001 panel, collected between February and August 2003, includes an adult well-being topical module that contains detailed measures of material hardship not included in other waves, specifically measures of housing and food security. Unlike core variables, topical module questionnaires are distributed only once during the wave, making repeated assessments of housing and food security impossible. As such, data for this article were taken from the Wave 8 core and topical module files and were necessarily cross-sectional in nature.

Wave 8 includes 24,315 households and 68,349 individuals. We restricted our analyses to a randomly selected child under age 18 drawn from each parent- or grandparent-headed household. We excluded all respondents 18 and older (n = 50,267, 73.5% of sample), as well as minors who did not live in the home of either a parent or a grandparent (n = 951, 1.4% of sample). Restricting the analyses to one child per household eliminated slightly less than half of eligible children (n = 8,234, 12.0% of sample). These restrictions leave a final sample size of 8,861 children. The Census Bureau imputed missing data in the SIPP primarily through hot-deck imputation and longitudinal data editing; therefore, no cases were lost as a result of missing data.

Measures

Poverty status

Each wave of the SIPP includes reports of income by source for each person in the household, for each of the 4 months prior to the interview. Household income was measured by summing the income reported by all individuals in the household, from all sources over the entire 4-month period covered by the interview. The summed values were averaged to yield a mean monthly income for that household. Using that income and the corresponding poverty cutoff for the household, we calculated the income-to-needs ratio for each child. We then constructed a three-category measure of hardship based on the household’s income-to-needs ratio: (a) poor, household falls below the poverty line; (b) near poor, household income falls at or above the poverty line but below 200% of poverty; and (c) not poor, household income falls at or above 200% of the poverty line.

Health insecurity

We used health insurance status as a proxy for the health security of children. The SIPP provides detailed information on the insurance status of each child in the household. We assessed a three-category measure of insurance status: (a) uninsured, child does not have access to public or private insurance; (b) publicly insured, child is covered by public insurance only; and (c) privately insured, child is covered by a privately purchased insurance plan, including coverage obtained through the employment of a parent or caregiver.

Housing insecurity

Housing insecurity was defined as the inability of the household to pay housing related bills, a measure used in prior research on the influence of living arrangements on material hardship (Manning & Brown, 2006). Households were identified as housing insecure (1 = yes; 0 = no) if the householder reported not paying the full amount of the rent or mortgage or not paying gas, oil, or electricity bills at any time in the year prior to interview.

Food insecurity

A global assessment of hunger and nutrition in the household was used to measure food insecurity. Households are identified as food insecure (1 = yes; 0 = no) if the householder reported at least two of the following problems in the previous 4 months: (a) food did not last, (b) could not afford balanced meals, (c) adults cut or skipped meals, (d) adults ate less than they should, and (e) adults did not eat for a whole day. This measure is derived from questions included in the U.S. Food Security Survey Module and corresponds to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) categorization of low or very low food security (Nord, 2006).

Generational Structure

We identified four distinct living arrangements based on parental/grandparental presence and household headship: (a) two-parent households (headed by a parent and containing two parents, either step or biological), (b) single-parent households (headed by a parent and containing only one parent), (c) three-generation households (headed by a grandparent and including one or more of the grandchild’s parents), and (d) skipped-generation households (headed by a grandparent in the absence of both the grandchild’s parents). Both two-parent and single-parent households may contain one or more grandparents. The three-generation, parent-headed households were initially included as a separate category in the analysis (n = 244); however, preliminary results suggested that such households were similar to other parent-headed households. Given that inclusion (or exclusion) of this category had little impact on the significance or magnitude of the results, we collapsed categories for the final analysis.

Parents were identified using person-number pointers that linked each child to coresident biological, adoptive, or stepparents. Two-parent households included biological parents and step-parents, as well as unmarried coresiding biological parents. Single-parent households may include an unmarried coresident partner who is not the biological parent of the target child. Grandparents were identified through the household roster. If the child was listed as the grandchild of the household reference person, the reference person and his or her spouse were identified as grandparents of the child. In the SIPP, the household reference person is the person under whose name the home is rented or owned—in other words, the householder. As such, we determined headship by linking the person number of the parent(s) and/or grandparent(s) to the person number of the household reference person.

Covariates

We also included several variables in the model to control for a range of social indicators that may shape hardship among children. First, we controlled for the age (in years) and race or ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other race, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White) of the child. We also controlled for characteristics of the child’s primary and/or shared caregivers (i.e., coresident parents/grandparents), including age (1 = at least one caregiver over age 65), and a series of dummy variables representing educational attainment (no caregiver with at least a high school degree vs. at least one caregiver with a high school degree vs. at least one college-educated caregiver). Finally, we controlled for the composition of the household, including a flag for children living in households headed by a single female (1 = single female; 0 = = other) and the ratio of children to adults in the household.

We separately controlled for labor force participation (no employed caregivers vs. at least one caregiver employed part-time vs. at least one caregiver employed full-time) and disability status (1 = at least one disabled caregiver) of the child’s primary and/or shared caregivers so as to reflect grandparents’ greater likelihood of prior exit from the labor force and poorer health status than parents. Caregivers were considered disabled if they reported difficulty with any functional activities (e.g., seeing, hearing, speaking, lifting, and carrying, using stairs, walking), activities of daily living (e.g., getting around inside the home, getting in or out of a bed or chair, bathing, dressing, eating, toileting), or instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., going outside the home, keeping track of money or bills, preparing meals, doing light housework, using the telephone), or if they reported use of a wheelchair, crutches, cane, or walker. We did not include work-limiting conditions in this categorization, as only those under age 67 were asked about this type of disability.

Analysis

To assess our first research question (are children who live in grandparent-headed households at increased risk of poverty and material hardship?), we estimated a series of multinomial and binary logistic regression models to explore the associations among generational structure of a household and poverty status, health security, housing security, and food security. Analyses were conducted at the child level and separate regression models were run for each outcome. Model 1 estimated the full association between generational structure and poverty and/or material hardship. Model 2 added covariates related to the demographic composition of the household (i.e., age and race or ethnicity of the child, age and education of the child’s caregivers, the presence of a single female householder, and the ratio of children to adults in the household). Model 3 retained those demographic controls and added covariates related to the labor force participation and disability of caregivers.

To assess our second research question (does the association between poverty and material hardship vary depending on the generational structure of the household?), we entered a series of interaction terms into the models to determine the extent to which the strength of the association between poverty and material hardship differed by the generational structure of the household. Given the small sample size of grandparent-headed households and the decreased statistical power introduced by multiple interaction terms, poverty status was measured as a two-category variable (1 = not poor; 0 = poor/near poor) in these models rather than as a three-category measure as above. We entered interaction terms into the model as follows: (a) Three generation × Not poor, (b) Skipped generation × Not poor, (c) Single parent × Not poor, and (d) Two parent × Not poor (referent).

Results

Table 1 details the sociodemographic profile of children, as well as reports of poverty and material hardship, by the generational structure of the household. Children in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were disproportionately members of racial and ethnic minority groups compared with children in two-parent families. As expected, both three-generation and skipped-generation households were significantly more likely to include caregivers over age 65 than were single-parent and two-parent households. Children in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were also significantly more likely to live with less educated caregivers, to live in a household headed by a single female, and to live with no employed caregivers than were children in two-parent households. Children living in three-generation and skipped-generation households were significantly more likely to live with a disabled caregiver than were children in both single-parent and two-parent households.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Poverty, and Material Hardship by Household Generational Structure

| Grandparent Headed |

Parent Headed |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three Generation (n = 486) |

Skipped Generation (n = 238) |

Single Parent (n= 2,076) |

Two Parent (n= 6,061) |

|

| Sample Characteristics | ||||

| Age of child | 4.31bcd | 8.62ad | 8.79ad | 6.96abc |

| Race/ethnicity of child | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | .41cd | .44d | .50ad | .71abc |

| Non-Hispanic Black | .30bd | .39acd | .29bd | .08abc |

| Non-Hispanic Other | .07c | .03 | .04ad | .06c |

| Hispanic | .23bcd | .15a | .17ad | .15ac |

| Caregiver(s) 65 + | .19bcd | .28acd | .02ab | .02ab |

| Education of caregivers | ||||

| No degree | .08bc | .28acd | .18abd | .06bc |

| High school educated | .74bcd | .59acd | .68abd | .50abc |

| College educated | .18cd | .13d | .14ad | .44abc |

| Single female head | .47cd | .42cd | .86abd | .02abc |

| Ratio of children to adults | .691bcd | 1.00acd | 1.49abd | .903abc |

| Labor force participation of caregivers | ||||

| No employed caregivers | .12bcd | .41acd | .25abd | .03abc |

| Employed part-time | .10cd | .12d | .15ad | .05abc |

| Employed full-time | .77bcd | .47acd | .60abd | .92abc |

| Disabled caregiver | .38bcd | .49acd | .13ab | .12abc |

| Poverty and Material Hardship | ||||

| Poverty Status | ||||

| Poor (<100%) | 16.9bcd | 30.7ad | 31.4ad | 8.8abc |

| Near poor (100 – 199%) | 23.9cd | 29.2d | 28.8ad | 18.2abc |

| Not poor (200%+) | 59.2bcd | 40.1ad | 39.8ad | 73.0abc |

| Health insecurity | ||||

| Uninsured | 23.5cd | 31.1cd | 19.1abd | 11.5abc |

| Public insurance | 42.8cd | 39.6cd | 31.2abd | 10.6abc |

| Private insurance | 33.7cd | 29.2cd | 49.7abd | 78.0abc |

| Housing insecurity | 21.1cd | 23.9d | 25.6ad | 12.0abc |

| Food insecurity | 14.9d | 16.0d | 18.2d | 7.0abc |

Note: Weighted means are shown.

Significantly different from three generation.

Skipped generation.

Single parent.

Two parent.

Are Children Who Live in Grandparent-Headed Households at Increased Risk of Poverty and Material Hardship?

With regard to income-based measures of hardship, children living in skipped-generation and single-parent households were the most likely to be living in poverty, with approximately 60% living in either poverty or near poverty. More than 40% of children in three-generation households were living in poverty or near poverty, compared with only 27% of children in two-parent households. This relative economic advantage for children in two-parent families extended to the experience of material hardship, as children living in two-parent families were significantly less likely to experience all types of material hardship compared with children in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households. Despite lower levels of poverty, children living in three-generation households were significantly more likely to be uninsured or publicly insured than children in single-parent households. Children living in skipped-generation households showed particularly low rates of private insurance; only 29% of the children living in that household type had some type of private insurance, compared with approximately one third of children in three-generation households, half of children in single-parent households, and nearly 80% of children in two-parent households. Especially striking was that nearly one third of children living in skipped-generation households were uninsured. Children living in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households experienced elevated risk of housing and food insecurity as well, each approximately twice that of children living in two-parent households.

Poverty Status

Table 2 presents the multinomial regression results of the association between living in a three-generation, skipped-generation, or single-parent (vs. two-parent) household and poverty status among children. Model 1 confirmed that, before controls are added to the model, children living in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were significantly more likely to be living in poverty and near poverty than children in households headed by two parents. Model 2 added variables representing the demographic composition of such households. This model suggested that children in three-generation households were no more likely to be living in poverty than children in two-parent households. The strength of the association between living in a skipped-generation household and poverty was reduced somewhat, but it nevertheless remained strong and significant. Children living in single-parent households were more likely to be living near poverty, but the addition of demographic composition to the model reduced the association between single parenthood and poverty to nonsignificance. Finally, Model 3 added labor force participation and disability to the model. Once these variables were taken into account, children in three-generation households were significantly less likely to be living in poverty and near poverty than were children in two-parent households. The association between living in a skipped-generation household and poverty was reduced to nonsignificance. The addition of labor force participation and disability had little influence on the association between living in a single-parent household and poverty or near poverty.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Poverty Status (N = 8,861)

| Poverty Status |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor vs. Not Poor |

Near Poor vs. Not Poor |

|||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Living arrangements | ||||||

| Three generation | .853** | −.188 | −.531* | .482*** | −.138 | −.307* |

| Skipped generation | 1.846*** | .745** | −.524 | 1.075*** | .452* | .010 |

| Single parent (Two parent) |

1.880*** | .237 | .270 | 1.064*** | .334** | .275* |

| Age of child | −.074*** | −.078*** | −.041*** | −.048*** | ||

| Race/ethnicity of child | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | .743*** | .826*** | .425*** | .480*** | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | .779*** | .734** | .537** | .569*** | ||

| Hispanic (Non-Hispanic White) |

.658*** | .798*** | .726*** | .739*** | ||

| Caregiver(s) 65+ | −.261 | −.801** | .628*** | .186 | ||

| Education of caregivers | ||||||

| No degree | 3.043*** | 2.765*** | 2.081*** | 2.070*** | ||

| High school educated (College educated) |

1.442*** | 1.352*** | 1.278*** | 1.277*** | ||

| Single female head | 1.084*** | .528** | .346** | .176 | ||

| Ratio of children to adults | .847*** | .982*** | .541*** | .590*** | ||

| Labor force participation of caregivers | ||||||

| No employed caregivers | 3.726*** | 1.257*** | ||||

| Employed part-time (Employed full-time) |

2.753*** | 1.376*** | ||||

| Disabled caregiver | .670*** | .674*** | ||||

| Constant | −2.116*** | −3.885*** | −4.478*** | −1.386*** | −2.687*** | −2.851*** |

| Pseudo R2 | .056 | .178 | .265 | .056 | .178 | .265 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Health Insecurity

Table 3 presents the multinomial regression results of the association between living in a three-generation, skipped-generation, or single-parent (vs. two-parent) household on health security. Model 1 confirmed that children living in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were more likely to be publicly insured and uninsured than children in two-parent households. This association was particularly strong for children in three-generation and skipped-generation households. Controlling for the demographic composition of the household in Model 2 reduced the strength of this association, but the relationship remained significant and strong for all groups. Model 3 suggested that once labor force participation and disability of caregivers were added to the model, the association between living in a single-parent household and being uninsured was reduced to nonsignificance. Although these barriers reduced the strength of the association between living in a three- or skipped-generation household and health insecurity, children in such households were still much more likely to receive public insurance or to be uninsured than were children in two-parent households.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Health Insecurity (N = 8,861)

| Health Insecurity |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public vs. Private Insurance |

Uninsured vs. Private Insurance |

|||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Living arrangements | ||||||

| Three generation | 2.238*** | 1.561*** | 1.347*** | 1.558*** | 1.185*** | 1.191*** |

| Skipped generation | 2.291*** | 1.702*** | 1.178*** | 1.976*** | 1.522*** | 1.263*** |

| Single parent (Two parent) |

1.532*** | .535*** | .394** | .961*** | .333* | .241 |

| Age of child | −.075*** | −.077*** | −.023*** | −.022** | ||

| Race/ethnicity of child | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | .589*** | .591*** | .392*** | .390*** | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | .709*** | .692*** | .783*** | .780*** | ||

| Hispanic (Non-Hispanic White) |

.945*** | .999*** | .906*** | .914*** | ||

| Caregiver(s) 65+ | −.014 | −.552* | .221 | −.019 | ||

| Education of caregivers | ||||||

| No degree | 2.908*** | 2.662*** | 2.044*** | 1.951*** | ||

| High school educated (College educated) |

1.656*** | 1.566*** | .945*** | .920*** | ||

| Single female head | .711*** | .409** | .340* | .181 | ||

| Ratio of children to adults | .148** | .110* | .149** | .125* | ||

| Labor force participation of caregivers | ||||||

| No employed caregivers | 1.572*** | .976*** | ||||

| Employed part-time (Employed full-time) |

1.472*** | 1.045*** | ||||

| Disabled caregiver | .685*** | .156 | ||||

| Constant | −1.998*** | −3.254*** | −3.395*** | −1.916 | −2.841*** | −2.895*** |

| Pseudo R2 | .067 | .167 | .198 | .067 | .167 | .198 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Housing and Food Insecurity

Table 4 presents the binary regression results of the association between living in a three-generation, skipped-generation, or single-parent (vs. two-parent) household on housing and food security. Again, Model 1 confirms that children living in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were more likely to experience both housing and food insecurity than were children living in two-parent households. After controlling for the demographic composition of the household in Model 2, this association disappeared, thus suggesting that children living in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were no more likely to experience housing and food insecurity than were children living in two-parent households with a similar demographic composition.

Table 4.

Binary Logistic Regression Results: Housing and Food Insecurity (N = 8,861)

| Housing Insecurity |

Food Insecurity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Living arrangements | ||||||

| Three generation | .681*** | −.046 | −.155 | .830*** | .267 | .101 |

| Skipped generation | .833*** | .141 | −.259 | .926*** | .185 | −.251 |

| Single parent (Two parent) |

.930*** | −.200 | −.240 | 1.076*** | .130 | .074 |

| Age of child | −.021 ** | −.024*** | −.007 | −.009 | ||

| Race/ethnicity of child | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | .379*** | .377*** | .287** | .263* | ||

| Non-Hispanic Other | −.110 | −.152 | .206 | .160 | ||

| Hispanic (Non-Hispanic White) |

.072 | .061 | .567*** | .555*** | ||

| Caregiver(s) 65+ | −.368 | −.769*** | .198 | −.197 | ||

| Education of caregivers | ||||||

| No degree | 1.368*** | 1.170*** | 1.606*** | 1.135*** | ||

| High school educated (College educated) |

1.157*** | 1.088*** | 1.131*** | 1.036*** | ||

| Single female head | .742*** | .585*** | .509*** | .290** | ||

| Ratio of children to adults | .241*** | .231*** | .255*** | .241*** | ||

| Labor force participation of caregivers | ||||||

| No employed caregivers | .522*** | .792*** | ||||

| Employed part-time (Employed full-time) |

.828*** | .831*** | ||||

| Disabled caregiver | .860*** | .751*** | ||||

| Constant | −1.996*** | −2.942*** | −3.042*** | −2.581*** | −3.769*** | −3.871*** |

| Pseudo R2 | .036 | .086 | .114 | .036 | .093 | .123 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Does the Association Between Poverty and Material Hardship Vary Depending on the Generational Structure of the Household?

To assess our second research question, we entered a series of interaction terms into each of the final material hardship models to determine the extent to which the strength of the association between poverty and material hardship differed by the generational structure of the household (see Table 5). As expected, children living in households identified as not poor were significantly less likely to experience health, housing, and food insecurity than were children living in poverty or near poverty. The addition of interaction terms (Three generation × Not poor, Skipped generation × Not poor, and Single parent × Not poor) suggested that the strength of the association between poverty and health security differed depending on the generational structure of the household. More specifically, the benefit of living above poverty or near poverty on health insecurity was significantly weaker for children living in three-generation and skipped-generation households than for children living in two-parent households. This was also true for children living in single-parent households, although only in the case of uninsurance. In addition, the strength of this interaction effect was particularly pronounced for those living in grandparent-headed households. Results suggest that the benefit of living above poverty or near poverty on housing insecurity was also significantly weaker for children living in three-generation and single-parent households but not for children living in skipped-generation households. Finally, reports of food security in three-generation, skipped-generation, and single-parent households were consistent with household poverty status.

Table 5.

Binary and Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Interaction Between Household Generational Structure and Poverty (N = 8,861)

| Health Insecurity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public vs. Private | Uninsured vs. Private | Housing Insecurity | Food Insecurity | |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Three generation | .606* | .508 | −.483* | −.014 |

| Skipped generation | .470 | .760** | −.291 | −.358 |

| Single parent (Two parent) |

.124 | −.069 | −.460** | .068 |

| Not Poor | −2.079*** | −1.276*** | −1.089*** | −1.491*** |

| Interactions | ||||

| Three generation × Not poor | 1.880*** | 1.091*** | .816** | .478 |

| Skipped generation × Not poor | 1.850*** | .865* | −.273 | .364 |

| Single parent × Not poor (Two parent × Not poor) |

.345 | .542*** | .448** | .314 |

| Constant | −1.801*** | −1.768*** | −2.140*** | −2.702*** |

| Pseudo R2 | .239 | .239 | .136 | .161 |

Note: Models control for child’s age and race/ethnicity; caregiver age, education, and gender and marital status; household size; and caregiver labor force participation and disability (omitted from table).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

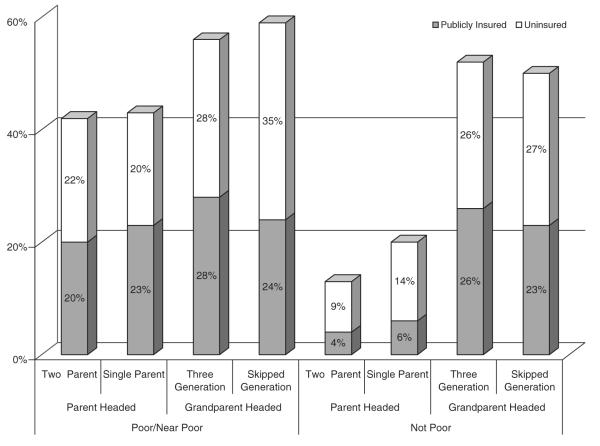

To understand more fully the magnitude and direction of the findings, we present predicted probabilities of the likelihood of experiencing health insecurity. Control variables were set to sample means to provide the predicted probability for an average child. Figure 1 clearly shows the dramatic inconsistency between poverty status and health security for children living in grandparent-headed households. Below the poverty line, all children have a high predicted probability of being either publicly insured or uninsured. This is particularly pronounced in grandparent-headed households. In fact, the model predicted that an average child in a skipped-generation household had a 35% probability of being uninsured, compared with 28% in three-generation households, 20% in single-parent households, and 22% in two-parent households.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities of Health Insecurity by Household Generational Structure and Poverty Status.

Note: Predicted probabilities calculated on the basis of coefficients in Table 5. Calculations assume sample means on independent variables.

For children in both single- and two-parent households above 200% of the poverty threshold, the predicted probability of being publicly insured or uninsured drops quite dramatically. Conversely, the probability remains quite high among children in three- and skipped-generation households. In fact, for children living in nonpoor grandparent-headed households, there is a more than 50% predicted probability of being uninsured or publicly insured, compared with only 22% for children living with a single parent and 14% for children living with two parents.

Discussion

Despite a twofold increase in the number of children living in grandparent-headed households in the United States, little research has focused on poverty and material hardship of children living in this arrangement. This research sought to determine (a) whether children who live in grandparent-headed households were at increased risk of poverty and material hardship, in and above that which the characteristics of their household and caregivers would predict, and (b) whether the association between poverty and material hardship varied depending on the generational structure of the household.

Although children living in grandparent-headed households were at risk for experiencing poverty and all types of material hardship measured, for the most part, they were no more likely to experience those outcomes than would be expected given the characteristics of their household and caregivers, at least with regard to poverty, housing insecurity, and food insecurity. Children in grandparent-headed households seem to be at disproportionate risk of experiencing health insecurity, even after taking into account the characteristics of their caregivers. This is consistent with prior research that highlights access to insurance as one of the greatest barriers children face in grandparent-headed households (Casper & Bryson, 1998). Results also suggest that the association between poverty and health insecurity in grandparent-headed households was less strong than in both single- and two-parent households, particularly as compared to two-parent households. That is, even nonpoor children in both skipped- and three-generation households were very likely to experience health insecurity—nearly as likely as similar children living in poverty. As expected, this association was most pronounced for health insecurity, as this is the type of material hardship associated with the greatest expense and least concrete and immediate consequences.

Elevated risk of poverty was primarily associated with the demographic composition of these households; labor force participation and disability of caregivers accounted for the remainder of this increased risk among both skipped-generation and three-generation households. In fact, once these factors were taken into account, children in three-generation households experienced a lower risk of poverty than did similar children in two-parent households. This finding is consistent with prior research showing that the financial security of children in three-generation households is enhanced through the economic contributions of grandparents, primarily through the household receipt of a wide range of financial resources, including Social Security income (Mutchler & Baker, 2009). Elevated risk of housing and food insecurity was explained entirely by the demographic composition of grandparent-headed households. This finding was contrary to our expectations given the unique barriers faced by these households, particularly in securing public assistance for coresident grandchildren. Further, reports of housing and food security were, for the most part, consistent with poverty status; that is, grandparent-headed households were no more or less likely than parent-headed households to report hardship once poverty status was accounted for. One exception to this was that the benefit of living above the poverty level for children in three-generation households was substantially less than that for children in two-parent households, which possibly reflects the more unexpected and transitory nature of those households.

The most notable finding was the disproportionately high rates of public insurance and uninsurance seen among children in both three-generation and skipped-generation grandparent-headed households. Even after controlling for the demographic composition of the household and the labor force participation and disability of caregivers, children living in three- and skipped-generation households were at increased risk of experiencing health insecurity, a substantial risk that children living with single parents did not share. This risk was pronounced for both uninsured children and children with public insurance.

Children living in three- and skipped-generation households are disproportionately publicly insured and uninsured, given their level of poverty. This association was strongest for public insurance, likely reflecting differential eligibility requirements in grandparent-headed households. Children living with single mothers were also disproportionately uninsured, although to a lesser degree than children in grandparent-headed households. These results suggested that some of the hypothesized differential in the association between poverty status and material hardship within grandparent-headed households with regard to uninsurance may have been ameliorated by eligibility for public insurance programs; however, these children were still at very high risk of being uninsured even above the poverty line. Given the unique barriers outlined here in obtaining private insurance for children in grandparent-headed households—barriers not faced in securing food and housing security—this finding is far from surprising.

This research is limited by the cross-sectional measurement of dependent variables; as such, we are unable to draw causal inference from the data. From this analysis, it is not possible to determine the extent to which the presence or absence of parents and grandparents cause reports of poverty and material hardship. It is entirely plausible that unmeasured characteristics of the parent, grandparent, and/or grandchild contribute to the findings. For example, children living in grandparent-headed households, particularly those in skipped-generation households, often experience developmental problems as a result of high rates of drug or alcohol abuse in utero. Such children likely experience barriers in obtaining private insurance because of their complex health care needs. Further, children who enter skipped- and three-generation households likely face economic distress before they enter the household. In fact, that distress and the potential economic support of coresident grandparents is often the reason for the formation of such households. Consequently, we cannot know that children currently living in grandparent-headed households would experience more consistent reports of poverty and material hardship if they reentered a parent-headed household, or vice versa. Further, the fluidity of living arrangements in grandparent-headed households poses problems for measurement. The frequency of nonparental living arrangements is often underestimated in this type of analysis (Hynes & Dunifon, 2007), and as these households may be short lived, the measurement of retrospective variables (e.g., experience of housing insecurity over the past year) may include reports from before the current household structure was formed.

Despite these limitations, the disproportionately high rates of health insecurity shown by this research are troubling. A lack of insurance may prevent children in grandparent-headed households from receiving needed services (Olson et al., 2005). Even those children who are covered by public insurance are at risk of poor health outcomes (Todd et al., 2006). The heavy reliance of children in grandparent-headed households on public insurance is especially problematic given the current economic climate. Escalating health care costs, in combination with the retrenchment of public insurance programs, will likely have a disparate impact on children living in grandparent-headed households. This vulnerability highlights the failings of an insurance system through which private insurance for children is obtained almost exclusively (with the exception of those who can afford an often prohibitively expensive individual policy) through the employment status of a legal guardian.

Advocacy efforts on behalf of children living in grandparent-headed households have succeeded in raising awareness of the issues and barriers faced by all members of these households and in many cases have succeeded in enacting policies designed to address the needs of children and adults in such households. Unfortunately, most programs and policies directed at this group are primarily housed at the state and local levels and are inevitably piecemeal in nature. The experience of children in such households has yet to be tied effectively to a larger national debate on the lack of comprehensive family policy in the United States and the tendency to structure existing federal, state, and local programs around an idealized notion of the family, an ideal that is increasingly unrealistic and/or undesirable for many individuals and families.

Grandparents without legal custody of coresident grandchildren may face many barriers, particularly as the children may be incorrectly denied benefits because of caseworkers’ unfamiliarity with their situation (Cox, 2009). Do such households and the children in them suffer because the U.S. system does not recognize the legitimacy of these family forms and because staff are not adequately trained to assess nonnuclear families? Further examination of the barriers faced by both children and adults living in grandparent-headed households will not only illuminate our understanding of the experience of multigenerational coresidence in childhood but also further our understanding of the consequences of rapidly changing family forms on the current policy environment and political system.

Acknowledgments

Note We gratefully acknowledge the support of research grant R03 HD043333 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and training grant T32-AG00037 from the National Institute on Aging.

Contributor Information

Lindsey A. Baker, University of Southern California

Jan E. Mutchler, University of Massachusetts.

References

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children’s cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108:44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ. Children’s physical and mental health. Health Affairs. 2007;26:549–558. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, Bryson K. Co-resident grandparents and their grandchildren: Grandparent maintained families. U. S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 1998. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0026/twps0026.html. [Google Scholar]

- Citro C, Michael R. Measuring poverty: A new approach. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cox C. Custodial grandparents: Policies affecting care. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2009;7:177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M, Driver D. A profile of grandparents raising grandchildren in the United States. Gerontologist. 1997;37:406–411. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generations United Grandparents and other relatives raising children: Support in the workplace. 2002 Retrieved from http://www.gu.org/documents/A0/Support_in_Workplace_FS_11.05.pdf.

- Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development. 2007;78:70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes K, Dunifon R. Children in no-parent households: The continuity of arrangements and the composition of households. Children and Youth Services Review. 2007;29:912–932. [Google Scholar]

- Jendrek MP. Policy concerns of white grandparents who provide regular care to their grandchildren. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1994;23:175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez J. The history of grandmothers in the African American community. Social Service Review. 2002;76:523–551. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM. Living arrangements of children: 2004. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2008. (Publication No. P70-114) [Google Scholar]

- Lee RD, Ensminger ME, LaVeist TA. The responsibility continuum: Never primary, coresident and caregiver; heterogeneity in the African-American grandmother experience. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2005;60:295–304. doi: 10.2190/KT7G-F7YF-E5U0-2KWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Brown S. Children’s economic well-being in married and cohabiting parent families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:345–362. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S. Indicators of children’s economic well-being and parental employment. In: Hauser R, Brown B, Prosser W, editors. Indicators of children’s well-being. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1997. pp. 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SE, Jencks C. Poverty and the distribution of material hardship. Journal of Human Resources. 1989;24:88–114. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Intergenerational households headed by grandparents: Contexts, realities, and implications for policy. Journal of Aging Studies. 1999;13:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, Baker LA. The implications of grandparent coresidence for economic hardship of children in mother-only families: Evidence from the 2001 SIPP. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30:1576–1597. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09340527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord M. SIPP 2001 Wave 8 Food Security Data File: Technical documentation and user notes. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; Washington, DC: 2006. Retrieved from http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/FoodSecurity/SIPP/sipp2001w8fs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Olson LM, Tang SS, Newacheck PW. Children in the United States with discontinuous health insurance coverage. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:382–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley MW, Riley JW. Connections: Kin and cohort. In: Bengtson VL, Achenbaum WA, editors. The changing contract across generations. Aldine de Gruyter; New York: 1993. pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Beltran A. The role of federal policies in supporting grandparents raising grandchildren families: The case of the U.S. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships. 2003;1(2):5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Todd J, Armon C, Griggs A, Poole S, Berman S. Increased rates of morbidity, mortality, and charges for hospitalized children with public or no health insurance as compared with children with private insurance in Colorado and the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118:577–585. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JP, Slack KS, Holl JL. Material hardship and the physical health of school-aged children in low-income households. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:829–836. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]