Abstract

Background: Several studies have shown that antihypertensive monotherapy is commonly insufficient to control blood pressure (BP) in hypertensive patients and that concomitant use of ≥2 drugs is necessary in ∼50% of these patients. The combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and a diuretic, delapril plus indapamide (D + I), has been shown to be effective and tolerable, with no interaction between the 2 components. Another widely used combination of ACE inhibitor and diuretic is lisinopril plus hydrochlorothiazide (L + H).

Objectives: The aims of this study were to confirm the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of the fixed combination of D + I in mild to moderate hypertension, and to compare its therapeutic efficacy and tolerability with that of L + H.

Methods: The antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of a fixed combination of D + I (30-mg + 2.5-mg tablets once daily) or L + H (20-mg + 12.5-mg tablets once daily) in patients with mild to moderate hypertension were compared in a multinational, multicenter, randomized, 2-armed, parallel-group study. Eligible patients were aged 18 to 75 years and had a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 95 to 115 mm Hg and a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤180 mm Hg, both measured in the sitting position. After a single-blind, placebo run-in period of 2 weeks, patients were randomized to receive 1 of the 2 treatments for a 12-week period. The primary efficacy end point was the BP normalization rate (ie, the percentage of patients with a sitting DBP ≤90 mm Hg) after 12 weeks of treatment. Secondary end points were as follows: (1) the responder rate (ie, the percentage of patients whose sitting DBP was reduced by ≥10 mm Hg from baseline or had a DBP ≤90 mm Hg after 12 weeks of treatment), (2) the percentage of patients with a DBP ≤85 mm Hg, and (3) changes in sitting SBP and DBP after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment.

Results: A total of 159 hypertensive patients (88 women, 71 men) were randomized to receive D + I (44 women, 36 men; mean [SD] age, 53 [11] years) or L + H (44 women, 35 men; mean [SD] age, 55 [10] years). No significant between-group differences were found in any of the primary or secondary end points of the study. Both combinations induced a significant reduction in sitting DBP and SBP from baseline (P<0.001 for both groups at week 12), without significant differences between the groups. Five mild to moderate adverse drug reactions (ADRs) occurred in each treatment group. No patient dropped out of the study because of an ADR.

Conclusion: This study showed no difference between D + I and L + H interms of antihypertensive efficacy or tolerability in patients with mild to moderate hypertension.

Keywords: hypertension, delapril, indapamide, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, combination therapy

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension represents one of the most common risk factors for cardiovascular disease, the major cause of mortality and disability in industrialized countries. The results of 2 clinical studies1,2 have demonstrated that blood pressure (BP) reduction provides benefits in terms of reduced cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, and the scientific community recommends early diagnosis and aggressive therapy for hypertension.3,4 The major goal in the treatment of hypertensive patients should be normalization of BP; 1 trial5 also has shown that the incidence of cardiovascular complications is often higher in treated hypertensive patients than in matched normotensive subjects.

Several studies3,4,6 conducted to identify the ideal antihypertensive drug have shown that monotherapy is commonly insufficient to control BP in hypertensive patients and that concomitant use of ≥2 drugs is necessary in ∼50% of these patients. Moreover, in addition to the superior therapeutic efficacy of this approach, the concomitant administration of antihypertensive drugs with different mechanisms of action allows dose decreases with the associated advantage of reduction of adverse events (AEs).3,4

Among antihypertensive therapies, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)inhibitors have become widely used therapeutic agents; in particular, a common approach is the combined administration of an ACE inhibitor and a diuretic.7 The greater antihypertensive efficacy of the combination is due not only to the antihypertensive effect of the single components but also to their complementary mechanisms of action. The ACE inhibitor blocks the counter-regulatory increase in angiotensin II (AII) triggered by diuretic therapy, and the diuretic appears to enhance the antihypertensive action of ACE inhibition, particularly in patients with reduced activity of the renin–angiotensin system. Furthermore, the modern fixed combinations of antihypertensive drugs have the advantages of ease of use; convenience; improved compliance; and, in general, lower cost.

Delapril is an esterified nonsulfhydryl ACE inhibitor, characterized structurally by the presence of an indanylglycine group. It is a prodrug that is well absorbed after oral administration and widely metabolized in vivo to the active metabolites M-I and M-III and the inactive metabolite M-II. Delapril has high, protracted antihypertensive activity. This drug strongly inhibits ACE, is more potent than captopril and enalapril in inhibiting vascular ACE, and differs from these drugs in that it is specific to the C-site of human tissue ACE.8

Indapamide is a methylindoline derivative with diuretic activity that interferes with vascular hyperreactivity in hypertensive patients, acting directly on vascular smooth muscle. As with thiazide-like diuretics, the diuretic activity of indapamide is limited to the cortical diluting segment of the nephron, and its vasodilating activity is thought to be due to different mechanisms—antagonism of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and AII vasoconstriction, reduction of transmembrane ionic exchange, and stimulation of prostaglandin E2 synthesis.Compared with thiazide diuretics, indapamide appears to have less potassium-depleting activity, and, in long-term therapy, it induces no negative effect on lipid or glucose metabolism.9–11

Clinical trials12–17 of the combination of delapril plus indapamide (D + I) showed, both in case of single administration and at steady state, no interaction between the 2 components, and demonstrated its antihypertensive efficacy. The efficacy of this combination therapy in comparative studies15,16 was significantly higher than that of the single components and was superior to that of captopril plus hydrochlorothiazide. The D + I combination was well tolerated,17 with a low incidence of AEs, which were mainly neurologic (vertigo, headache), respiratory (cough), gastrointestinal, and fatigue. Dermal and cardiovascular reactions were found to a lesser extent. The systemic tolerability was confirmed by the results of laboratory examinations. Another widely used combination of ACE inhibitor plus diuretic is lisinopril plus hydrochlorothiazide (L + H).

The aims of this study were to confirm the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of the fixed combination of D + I in mild to moderate hypertension, and to compare its therapeutic efficacy and tolerability with those of L + H.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a multinational, multicenter, randomized, 2-armed, parallel-group study with a 2-week, single-blind, placebo (matching D + I) run-in period followed by 12 weeks of treatment with a fixed combination of either D + I (30-mg + 2.5-mgtablets once daily) or L + H (20-mg + 12.5-mg tablets once daily). The study was approved by the ethics committee at each of the participating centers. After written informed consent was obtained, the patients discontinued all existing antihypertensive medications (if any) and entered the placebo run-in period.

Patients

Patients with mild to moderate hypertension and aged 18 to 75 years were eligible. Patients had a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) 95 to 115 mm Hg anda systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤180 mm Hg, both measured in the sitting position. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: SBP >180 mm Hg; secondary hypertension; orthostatic hypotension (decrease in SBP ≥30 mm Hg on standing); heart failure; major arrhythmias; myocardial infarction, bypass graft, coronary angioplasty, or cerebrovascular accidents in the preceding 6 months; severe peripheral arteriopathy; serum creatinine concentration>1.5 mg/dL; severe hepatic, metabolic, hematologic, or immunologic disorders; diseases of the gastrointestinal tract; psychiatric or neurologic disorders; known hypersensitivity to the study drugs; poor compliance (<75% during the placebo run-in period); or a history of alcohol or drug abuse. Patients also were excluded if they were obese (body mass index, >32 kg/m2). Pregnant, possibly pregnant, or lactating women also were excluded.

Methods

Patients who were eligible on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomized to 1 of the 2 treatment groups. During the 12-week study, each patient visited the clinic 5 times: 2 weeks before randomization; at randomization (week 0); and at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after randomization. SBP and DBP were measured at each visit at 9:00 AM±2 hours before drug administration. BP was measured after the patient had been sitting comfortably at rest for 5 minutes. Three consecutive measurements were performed in the sitting position (at 3-minute intervals), and the mean of the 3 measurements was used. BP also was measured in the standing position after the patient had been standing for 1 minute. Heart rate (HR) was measured at each visit in both the sitting and standing positions after at least 5 minutes of comfortable rest.

The primary efficacy end point was the BP normalization rate (ie, the percentage of patients with a sitting DBP ≤90 mm Hg) after 12 weeks of treatment. Secondary end points were as follows: (1) the responder rate (ie, the percentage of patients whose sitting DBP was reduced by ≥10 mm Hg from baseline or had a DBP ≤90 mm Hg after 12 weeks of treatment), (2) the percentage of patients with a DBP ≤85 mm Hg, and (3) changes in sitting SBP and DBP after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of treatment.

Tolerability analysis was performed by recording the occurrence of AEs, changes in laboratory parameters (hematology, biochemistry, and urinalysis) and physical signs, HR, and electrocardiographic abnormalities.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis was carried out on both the intent-to-treat (ITT) population (ie, patients who received ≥1 dose of the study drugs) and the per-protocol (PP) population (ie, patients who completed the study without protocol violations). In the ITT population, the last-observation-carried-forward method was applied to manage missing data. Homogeneity of data was verified at baseline (chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, and the Student t test), and normality of distribution was tested at each study time point (Shapiro and Wilk's W test). Comparisons of normalized and responder patients between the 2 treatment groups were performed using the chi-square test. Between-treatment differences in BP changes were tested by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test adjusted for multiple comparisons (in case of nonnormal distribution of data) or by analysis of variance for multiple comparison (in case of normal distribution of data). Tolerability analysis was carried out on the ITT population using the chi-square test. Data are expressed as mean (SD). P<0.05 was used as the level of statistical significance. The study provided an 80% power to detect a difference in BP normalization rate of at least 12% between groups, with a hypothesis of 82% of normalization in the L + H group and a significance level of 0.05. Thus, a total of 156 patients was the target.

RESULTS

The study was conducted at 9 centers in Croatia, the Czech Republic, and Slovenia. A total of 163 outpatients entered the run-in phase; of these, 159 (97.5%; 88 women, 71 men) were eligible for the active-treatment phase. Among this sample, 80 patients (50.3%; 44 women, 36 men; mean [SD] age, 53 [11] years) were randomized to the D + I group and 79 (49.7%; 44 women, 35 men; mean [SD] age, 55 [10] years) to the L + H group (Table I). Two major protocol violations occurred; therefore, the PP population comprised 78 patients (49.1%) in the D + I group and 79 patients (49.7%) in the L + H group.

Table I.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the intent-to-treat studypopulation (N = 159).

| Characteristic | D + I (n = 80) | L + H (n = 79) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, no. (%) | ||

| Women | 44 (55.0) | 44 (55.7) |

| Men | 36 (45.0) | 35 (44.3) |

| Age, y | ||

| Mean (SD) | 53 (11) | 55 (10) |

| Range | 24–73 | 23–72 |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kg | 79 (11) | 79 (9) |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 170 (8) | 170 (8) |

| Sitting DBP, mm Hg | ||

| Mean (SD) | 101.6 (4.9) | 102.2 (4.8) |

| Range | 95–115 | 95–115 |

| Sitting SBP, mm Hg | ||

| Mean (SD) | 161.9 (11.5) | 162.3 (13.1) |

| Range | 127–180 | 135–180 |

| HR, bpm | ||

| Mean (SD) | 72.9 (9.7) | 70.4 (7.4) |

| Range | 55–98 | 56–88 |

| Concomitant diseases, no. (%) | ||

| DM | 14 (17.5) | 9 (11.4) |

| Dyslipidemia | 8 (10.0) | 3 (3.8) |

| IHD | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| Previous antihypertensive treatment, no. (%) | 31 (38.8) | 33 (41.8) |

| ACE inhibitors | 14 (17.5) | 14 (17.7) |

| CCBs | 9 (11.3) | 7 (8.9) |

| Beta-blockers | 5 (6.3) | 7 (8.9) |

| Combination therapy | 3 (3.8) | 5 (6.3) |

D + I = delapril + indapamide; L + H = lisinopril + hydrochlorothiazide; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; HR = heart rate; DM = diabetes mellitus; IHD = ischemic heart disease; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; CCBs = calcium channel blockers.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline were comparable in the 2 treatment groups.

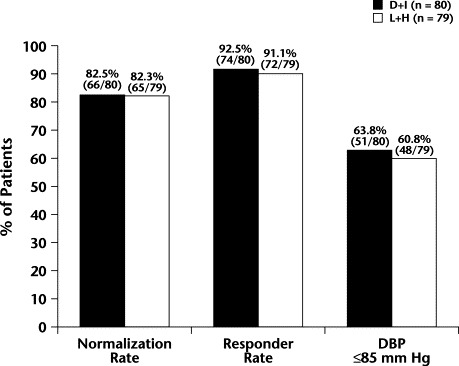

The BP normalization rates were 82.5% [66/80] and 82.3% [65/79] in the D + I and L + H groups, respectively (ITT analysis) (Figure 1). The PP analysis showed normalization rates of 83.3% (65/78) and 82.3% (65/79) in the D + I and L + H groups, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found between the 2 groups.

Figure 1.

Normalization rate (sitting diastolic blood pressure [DBP] ≤90 mm Hg), responder rate (sitting DBP ≤90 mm Hg or a reduction in sitting DBP from baseline ≥10 mm Hg), and patients with sitting DBP ≤85 mm Hg in the delapril plus indapamide (D + I) and lisinopril plus hydrochorothiazide (L + H) groups (intent-to-treat analysis) after 12 weeks of treatment. No statistically significant between-group differences were found.

The responder rate was 92.5% (74/80) in the D + I group compared with 91.1% (72/79) in the L + H group (ITT analysis); the between-group difference wasnot statistically significant. In the PP analysis, the responder rates were93.6% (73/78) and 91.1% (72/79) in the D + I and L + H groups, respectively; no significant between-group difference was found.

The percentage of patients who reached a sitting DBP ≤85 mm Hg was 63.8% (51/80) in the D + I group and 60.8% (48/79) in the L + H group in the ITT analysis, and 65.4% (51/78) and 60.8% (48/79) in the PP analysis. The between-group differences were not statistically significant.

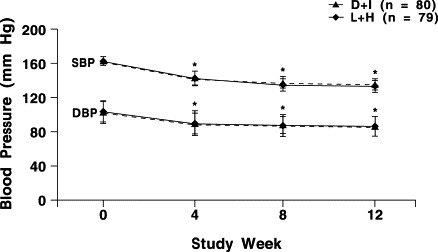

Sitting SBP was significantly reduced from baseline to study end with both treatments (Table II). In the D + I group, the mean (SD) sitting SBP decreased significantly, from 161.9 (11.5) mm Hg to 133.8 (12.2) mm Hg (P<0.001). In the L + H group, the mean (SD) sitting SBP significantly decreased from 162.4 (13.1) mm Hg to 131.2 (11.6) mm Hg (P<0.001). No significant between-group differences were found in changes in SBP or DBP at any visit (Figure 2).

Table II.

Sitting systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (mm Hg) during the 12-week study period (intent-to-treat analysis).

| Baseline | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | ||||

| D + I (n = 80) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 161.9 (11.5) | 141 (14.4) | 136.4 (12.7) | 133.8 (12.2)∗ |

| Range | – | 110–180 | 110–166 | 113–172 |

| Mean change | – | −20.9 | −25.5 | −28.1 |

| 90% CI of mean change | – | −23.4 to −18.5 | −27.9 to −23.1 | −30.7 to −25.6 |

| L + H (n = 79) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 162.4 (13.1) | 140 (12.4) | 133 (10.3) | 131.2 (11.6)∗ |

| Range | – | 119–175 | 106–155 | 108–160 |

| Mean change | – | −22.4 | −29.6 | −31.2 |

| 90% CI of mean change | – | −29.9 to −19.6 | −31.2 to −26.7 | −34.2 to −28.3 |

| DBP | ||||

| D + I (n = 80) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 101.6 (5.0) | 88.0 (8.2) | 86.0 (7.2) | 84.3 (6.7)∗ |

| Range | – | 67–105 | 62–101 | 65–104 |

| Mean change | – | −13.6 | −15.6 | −17.3 |

| 90% CI of mean change | – | −15.2 to −11.9 | −17.0 to −13.8 | −18.8 to −15.8 |

| L + H (n = 79) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 102.3 (4.9) | 88 (4.4) | 85 (7.5) | 84.4 (7.1)∗ |

| Range | – | 70–108 | 65–100 | 70–100 |

| Mean change | – | −14.3 | −17.3 | −17.9 |

| 90% CI of mean change | – | −15.4 to −12.3 | −18.7 to −15.8 | −19.3 to −16.5 |

D + I = delapril + indapamide; L + H = lisinopril + hydrochlorothiazide.

P<0.001 versus baseline.

Figure 2.

Sitting systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) during the 12-week study period (intent-to-treat analysis) in the delapril plus indapamide (D + I) andthe lisinopril plus hydrochlorothiazide (L + H) groups. No statistically significant between-group differences were found. ∗P<0.001 compared with baseline.

In the D + I group, the mean (SD) sitting DBP after 12 weeks of treatment significantly decreased, from 101.6 (5.0) mm Hg to 84.3 (6.7) mm Hg (P<0.001). Similarly, in the L + H group, mean (SD) sitting DBP decreased significantly, from 102.3 (4.9) mm Hg to 84.4 (7.1) mm Hg (P<0.001).

In normalized patients, mean (SD) SBP decreased from 162.0 (11.3) mm Hg (range, 127–180 mm Hg) to 130.0 (10.3) mm Hg (range, 113–161 mm Hg) and from 162.7 (12.9) mm Hg (range, 125–180 mm Hg) to 128.3 (10.4) mm Hg (range, 108–160 mm Hg) in the D + I and L + H groups, respectively. DBP decreased from 101.3 (5.0) mm Hg to 82.2 (5.1) mm Hg (range, 65–90 mm Hg) in the D + I group and from 101.7 (4.7) mm Hg to 81.9 (4.9) mm Hg (range, 70–90 mm Hg) in the L + H group.

No significant change in HR was observed in either group throughout the study (data not shown).

During the 12-week treatment period, 19 AEs were reported (10 AEs [52.6%] in the D + I group; 9 AEs [47.4%] in the L + H group); these included fatigue and malaise, dizziness, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, and increase in serum gamma-glutamyltransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels. Among these 19 AEs, 10 [52.6%] were recorded as adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Five ADRs (50%; 4 [80%] of mild severity and 1 [20%] of moderate severity) occurred in the D + I group. In the L + H group, 5 ADRs (1 [20%] mild and 4 [80%] moderate) occurred. No patient dropped out of the study because of an ADR. No clinically relevant changes were found in laboratory or electrocardiographic findings, except for increased serum uric acid level (by 7.1% and 5.4% in the D + I and L + H groups, respectively); the between-group difference was not significant. At the final visit, no patient had a plasma potassium level <3 mEq/L, and only4 patients (2.5%; all in the D + I group) had a potassium level ≤3.5 mEq/L, butin 3 of these patients (75.0%), the potassium level had been ≤3.5 mEq/Lat baseline.

DISCUSSION

A combination of drugs with different, complementary mechanisms of action can provide effective antihypertensive therapy while reducing ADRs, thereby increasing cardiovascular protection. A fixed combination ensures greater compliance, simple administration, and lower cost, while reducing the risk for inappropriate associations.

Experimental and clinical data18 have demonstrated the antihypertensive efficacy of the combination of an ACE inhibitor and a diuretic, with a response rate >80%. The great efficacy of this combination has been shown to be due not only to the combined antihypertensive effect of the single drugs, but also to their reciprocal potentiation; in fact, the diuretic stimulates the renin-angiotensin system, which increases the hypotensive effect of the ACE inhibitor and, in turn, the ACE inhibitor prevents the production of AII, which tends to blunt the hypotensive effect of the diuretic. In other words, the conditions are created for the ACE inhibitor to act at its full potential and for the diuretic to maintain its efficacy in chronic treatment.

The present results, within the limitations of an open study, demonstrated no difference in the antihypertensive efficacy or in the tolerability profile of the combination of D + I compared with that of L + H. Efficacy analyses14–17 demonstrate the capacity of D + I to significantly reduce SBP and DBP; in particular, the data of this study confirm the normalization rate (82.5%) and responder rate (92.5%) observed in previous controlled trials for D + I. The results demonstrate a similar antihypertensive efficacy of both combinations and showed similar tolerability between treatments. Neither D + I nor L + H was associated with serious AEs (ie, AEs that led to dropping out). The favorable tolerability profile is confirmed by the absence of abnormal findings on standard laboratory tests.

CONCLUSION

This study showed no difference between D + I and L + H in terms of antihypertensive efficacy or tolerability in patients with mild to moderate hypertension.

Acknowledgements

The following investigators participated in the study: J. Cikes, MD, and A. Smalcelij, MD, Clinic of Cardiovascular Disease, University of Zagreb, Zagreb; D. Planinc, MD, Klinical Bolnica Sestre Milosdrnice, Zagreb; D. Popanic, MD, Klinicka Bolnica “Mercur,” Zagreb, Croatia; E. Fabian, MD, First Prague Health Department, “Medicover,” Prague; J. Sedlak, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Policlinic International Vinohrady, Prague; E. Valentova, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, St. Elizabeth Hospital, Prague; J. Zeman, MD, Department of Clinical Cardiology, University Hospital Bulovka, Prague, Czech Republic; and J. Dobovisek, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Footnotes

Reproduction in whole or part is not permitted.

References

- 1.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease: Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: Overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staessen J.A, Wang J.G, Thijs L. Cardiovascular protection and blood pressure reduction: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2001;358:1305–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06411-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guidelines Subcommittee 1999 World Health Organization–International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999;17:151–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers S.G, for the HOT Study Group Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: Principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancia G, Carugo S, Grassi G. Prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients without and with blood pressure control: Data from the PAMELA population. Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni. Hypertension. 2002;39:744–749. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.104669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rappelli A. Controlling hypertension: Lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide vs captopril-hydrochlorothiazide. An Italian multicentre study. J Hum Hypertens. 1991;5(Suppl 2):55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevilacqua M, Vago T, Rogolino A. Affinity of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for N- and C-binding sites of human ACE is different in heart, lung, arteries, and veins. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;28:494–499. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plante G.E, Dessurault D.L. Hypertension in elderly patients. A comparative study between indapamide and hydrochlorothiazide. Am J Med. 1988;84(Suppl 1B):98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gambardella S, Frontoni S, Pellegrinotti M. Carbohydrate metabolism in hypertension: Influence of treatment. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22(Suppl 6):S87–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ames R.P. A comparison of blood lipid and blood pressure responses during the treatment of systemic hypertension with indapamide and with thiazides. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:12b–16b. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poli G, Acerbi D, Ventura P, Hutt V. Pharmacokinetics of delapril and indapamide after single and repeated administration in healthy volunteers. Blood Press. 1994;3(Suppl):17S–25S. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutt V, Pabst G, Dilger C. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of a fixed combination of delapril/indapamide following single and multiple dosing in healthy volunteers. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1994;19:59–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03188824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rappelli A, Dessì Fulgheri P, Agabiti-Rosei E. Delapril and indapamide combination therapy in hypertensive patients: A double-blind randomized multicenter study. Blood Press. 1994;3(Suppl):34S–38S. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonetti G, on behalf of the DIMS investigators Delapril-Indapamide Multicenter Study (DIMS) Cardiologia. 1997;42(Suppl):401S–406S. [in Italian] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosei E.A, Rizzoni D. Evaluation of the efficacy and tolerability of the combination delapril plus indapamide in the treatment of mild to moderate essential hypertension: A randomised, multicentre, controlled study. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:139–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosiello G, Tozzi N, Sarno D. Safety and tolerability of long-term treatment with delapril-indapamide combination in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. Blood Press. 1994;3(Suppl):74S–79S. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambrosioni E, Borghi C, Costa F.V. Captopril and hydrochlorothiazide: Rationale for their combination. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23(Suppl 1):43S–50S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]