Abstract

Background: Because of the increasing realization of the importance of optic nerve head perfusion in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, the influence of new antiglaucomatous drugs on ocular hemodynamic properties should be investigated.

Objective: The aim of this study was to compare the effects of 2 prostaglandin analogues, travoprost eye drops and latanoprost eye drops, on intraocular pressure (IOP) and pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Methods: Previously untreated patients aged 40 to 60 years with POAG and normal brachial blood pressure (BBP), heart rate, body mass index, and hemorheologic findings were eligible for this randomized, double-masked study. Two drops of travoprost (group T) or latanoprost (group L) were self-administered in both eyes at 9:00 pm. In all patients, IOP, pOBF, BBP, and heart rate were measured at baseline and on days 15, 30, 60, 90, and 180 of treatment.

Results: Twenty-five consecutive patients with POAG were enrolled in this study conducted at the Glaucoma Research Center of the Department of Ophthalmology, Bari University, Policlinico di Bari (Bari, Italy). Of these, 7 were withdrawn because they did not return for the second appointment, leaving 18 patients (11 men, 7 women; mean [SD] age, 51.9 [5.5] years) to complete the study. In both groups, mean IOP values were significantly reduced at all time points compared with baseline (all P<0.01). Mean pOBF values increased ∼50% from baseline following treatment with either travoprost or latanoprost by day 15, were maintained at that level for 60 days, and then gradually decreased (group T: P = NS, NS, <0.01, <0.05, and <0.05 at days 15, 30, 60, 90, and 180, respectively, vs baseline; group L: P<0.01 at all time points vs baseline). All other parameters remained constant throughout the study. An early inverse correlation between IOP and pOBF was noted in group T but not in group L. No significant differences were found between groups in IOP or pOBF at any time point.

Conclusions: In this study population, pOBF was increased with travoprost and latanoprost in the short term, but this effect was kept constant only with travoprost. IOP was reduced with both drugs after short-term therapy, and this reduction was maintained in both groups. Travoprost may represent another option for the medical treatment of POAG.

Keywords: travoprost, latanoprost, pulsatile ocular blood flow, intraocular pressure, primary open-angle glaucoma

Introduction

Because of the increasing realization of the importance of optic nerve head perfusion in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, the influence of new antiglaucomatous drugs on ocular hemodynamic properties should be investigated.1 We searched for articles on primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) using MEDLINE (key words searched: nerve head perfusion, glaucoma, ocular blood flow, hemodynamic, antiglaucomatous drugs, travoprost, and latanoprost; years searched: 1998–2002), as well as all materials available in the Bari University library (key words searched: same as above; years searched: 1985–2002). Our search revealed that in recent studies, latanoprost eye drops were reported to increase ocular blood flow (by acting on the prostaglandin F [PGF] vascular receptor2–5) and to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP).6–8 Compared with PGF20 isopropyl ester, travoprost eye drops showed a more selective affinity for the PGF receptor with fewer severe adverse events (AEs),9 offering superior IOP reduction and diurnal control.10,11 However, to date no studies have examined the effects of this drug on ocular hemodynamic properties.

Considering the importance of ocular blood flow in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, we compared the effects of travoprost and latanoprost eye drops on IOP and pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) in patients with POAG.

Patients and methods

Patients regularly attending the Glaucoma Research Center of the Department of Ophthalmology at Bari University, Policlinico di Bari (Bari, Italy), between January and March 2002 were eligible for this randomized, double-blind study. The independent ethics committee of the Policlinico approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

At their first appointment at the center, consecutive patients with POAG were enrolled in the study. The POAG diagnostic criteria were glaucomatous visual field loss, pathologic optic disc cupping or notching, an open drainage angle, IOP >20 mm Hg without topical treatment, and a tonometric curve that ruled out normotensive glaucoma.

To avoid the influence of ocular and general factors that could affect pOBF measurements, we adopted the following ocular inclusion criteria: refraction of ±3 diopters (D); absence of previous ocular hypotensive treatments; and progression of visual field loss documented by at least 3 full-threshold 30-2 visual field tests with the Humphrey Field Analyzer model 606 (Zeiss Humphrey Systems, San Leandro, California) in the previous year. The score on the full-threshold visual field test was based on the Humphrey visual field rating criteria.12 Patients with other kinds of glaucoma were excluded from the study.

Patients were eligible for the study if they met the following criteria: nonsmoker; age 40 to 60 years; systolic brachial blood pressure (BBP) 120 to 140 mm Hg; diastolic BBP 70 to 90 mm Hg; heart rate 66 to 80 beats/min; body mass index appropriate for sex and age; and normal hemorheologic parameters (hematocrit, hemoglobin concentration, plasma iron concentration, leukocyte count, platelet count). Patients could not have any cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, atherosclerosis or carotid stenosis) or be taking systemic vasoactive therapy (eg, aspirin, calcium antagonists, nitroglycerin derivatives, oral beta-blockers).

Patients who met all of the inclusion criteria were block-randomized, to improve the distribution of patients during follow-up, to the travoprost∗ group (group T) or the latanoprost† group (group L). The labels were removed from the bottles, identical in appearance, containing the eye drops so that patients would not know which drug they were receiving. Patients were instructed to self-administer 2 drops in both eyes once daily at 9:00 pm.

IOP and pOBF were determined with patients seated after a 5-minute rest period, using the Langham pOBF tonograph (Langham Ophthalmic Technologies, Timonium, Maryland). Measurements were taken at 10:00 am at baseline and on days 15, 30, 60, 90, and 180 of treatment. Blood pressure and heart rate also were measured at all of these time points. To minimize bias, all of the examinations were carried out by one of the authors (M.V.), who had considerable experience using the instruments. The physician who performed the IOP and pOBF measurements was masked to patient treatment. According to the protocol suggested by Langham et al13 to measure pOBF, the probe was mounted on a slit-lamp and was gently pushed onto the previously anesthetized corneal apex. The instrument automatically took 5 measurements, and the mean value was determined.

AEs were monitored at the same time points as the pOBF measurements. Investigators monitored objective signs and patients spontaneously reported subjective symptoms. Patients were questioned about the occurrence of a set of primary AEs (conjunctival hyperemia, conjunctival papillae, stinging, burning, and foreign-body sensation).

Statistical analysis

The mean IOP and pOBF values were calculated before and after treatment. Variation within each group was determined using the Bonferroni and Dunnett multiple comparison tests (control: baseline) and between groups using the unpaired t test. To assess the effect of the eye drops on ocular pressure, the Pearson product moment correlation was calculated for IOP and pOBF at each time point. Differences were considered significant at P≤0.05 (2-tailed test). All analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat® version 3.05 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, California).

Results

Twenty-five consecutive patients with POAG were enrolled in the study. Of these, 7 were withdrawn because they did not return for the second appointment. The baseline characteristics of the 18 remaining patients (11 men, 7 women; mean [SD] age, 51.9 [5.5] years) are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by treatment group. (Data are given as mean [SD] unless otherwise indicated.)

| Characteristic | Travoprost (n = 9) | Latanoprost (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y (range, 46–60) | 52.3 (5.2) | 51.6 (4.2) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||

| Men | 5 (55.6) | 6 (66.7) |

| Women | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) |

| Systolic BBP, mm Hg | 132.4 (7.9) | 130.3 (8.5) |

| Diastolic BBP, mm Hg | 85.0 (8.4) | 86.1 (8.0) |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 82.8 (5.8) | 81.8 (5.9) |

| Eyes, n | 18 | 18 |

| Refraction, median (SE), diopters | 0.70 (1.14) | 0.67 (0.77) |

| IOP, mm Hg | 23.7 (2.8) | 24.1 (2.9) |

| pOBF, μL/min | 709.8 (284.1) | 680.8 (88.4) |

| Cup-to-disk ratio | 0.44 (0.07) | 0.43 (0.09) |

BBP = brachial blood pressure; IOP = intraocular pressure; pOBF = pulsatile ocular blood flow.

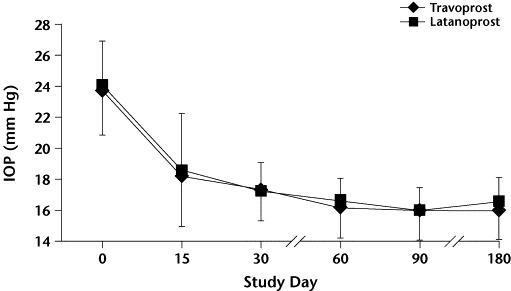

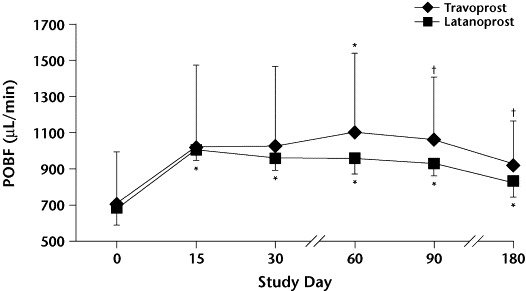

The IOP and pOBF values are shown in Tables II and III, respectively. The mean (SD) IOP and pOBF values are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively, and Table IV.

Table II.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) (mm Hg) and pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) (μL/min) in the travoprost group at baseline and throughout the treatment period.

| Baseline |

Day 15 |

Day 30 |

Day 60 |

Day 90 |

Day 180 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No./Eye | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF |

| 1/Left | 27 | 463 | 22 | 1021 | 21 | 758 | 17 | 1092 | 19 | 1159 | 16 | 840 |

| 1/Right | 25 | 916 | 18 | 1068 | 20 | 1190 | 15 | 1420 | 18 | 1454 | 16 | 1160 |

| 2/Left | 22 | 724 | 18 | 1013 | 19 | 840 | 14 | 888 | 16 | 1026 | 15 | 876 |

| 2/Right | 22 | 792 | 20 | 1033 | 19 | 969 | 17 | 687 | 15 | 962 | 17 | 851 |

| 3/Left | 25 | 537 | 25 | 485 | 20 | 570 | 22 | 728 | 18 | 793 | 20 | 693 |

| 3/Right | 24 | 710 | 22 | 865 | 19 | 659 | 16 | 1077 | 18 | 683 | 20 | 695 |

| 4/Left | 22 | 576 | 19 | 754 | 19 | 811 | 15 | 998 | 14 | 853 | 14 | 812 |

| 4/Right | 25 | 644 | 20 | 721 | 17 | 892 | 17 | 785 | 16 | 898 | 16 | 852 |

| 5/Left | 23 | 496 | 16 | 1105 | 17 | 753 | 16 | 843 | 18 | 922 | 18 | 770 |

| 5/Right | 21 | 470 | 16 | 917 | 15 | 947 | 15 | 1296 | 18 | 835 | 17 | 765 |

| 6/Left | 19 | 734 | 13 | 935 | 15 | 1065 | 16 | 954 | 16 | 754 | 15 | 702 |

| 6/Right | 22 | 629 | 14 | 1057 | 16 | 914 | 17 | 1008 | 17 | 1041 | 16 | 994 |

| 7/Left | 32 | 366 | 21 | 713 | 15 | 710 | 14 | 694 | 14 | 783 | 14 | 758 |

| 7/Right | 25 | 374 | 21 | 570 | 15 | 721 | 17 | 711 | 17 | 652 | 17 | 720 |

| 8/Left | 25 | 853 | 16 | 2576 | 16 | 2380 | 18 | 2406 | 12 | 1781 | 14 | 1251 |

| 8/Right | 23 | 829 | 16 | 1026 | 15 | 1622 | 18 | 1496 | 14 | 1581 | 14 | 1114 |

| 9/Left | 22 | 1157 | 16 | 1360 | 17 | 1171 | 14 | 1107 | 15 | 1310 | 15 | 1240 |

| 9/Right | 22 | 1506 | 15 | 1291 | 18 | 1510 | 14 | 1677 | 15 | 1595 | 15 | 1535 |

Table III.

Intraocular pressure (IOP) (mm Hg) and pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) (μL/min) in the latanoprost group at baseline and throughout the treatment period.

| Baseline |

Day 15 |

Day 30 |

Day 60 |

Day 90 |

Day 180 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No./Eye | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF | IOP | pOBF |

| 10/Left | 25 | 754 | 20 | 1021 | 17 | 980 | 17 | 970 | 17 | 990 | 25 | 754 |

| 10/Right | 22 | 816 | 20 | 1068 | 15 | 1104 | 16 | 1100 | 16 | 920 | 22 | 816 |

| 11/Left | 26 | 670 | 19 | 1013 | 18 | 840 | 16 | 820 | 16 | 990 | 26 | 670 |

| 11/Right | 24 | 745 | 18 | 1033 | 17 | 969 | 15 | 964 | 17 | 962 | 24 | 745 |

| 12/Left | 22 | 650 | 20 | 980 | 20 | 1045 | 18 | 995 | 20 | 820 | 22 | 650 |

| 12/Right | 28 | 760 | 19 | 1110 | 18 | 1000 | 18 | 1100 | 20 | 880 | 28 | 760 |

| 13/Left | 24 | 743 | 18 | 1012 | 15 | 990 | 14 | 998 | 16 | 950 | 24 | 743 |

| 13/Right | 26 | 756 | 17 | 1020 | 17 | 892 | 15 | 1045 | 16 | 898 | 26 | 756 |

| 14/Left | 23 | 540 | 17 | 940 | 16 | 990 | 18 | 843 | 18 | 922 | 23 | 540 |

| 14/Right | 21 | 570 | 15 | 917 | 15 | 947 | 18 | 800 | 17 | 835 | 21 | 570 |

| 15/Left | 18 | 780 | 15 | 1090 | 16 | 941 | 16 | 954 | 15 | 996 | 18 | 780 |

| 15/Right | 22 | 740 | 16 | 1057 | 17 | 914 | 17 | 920 | 17 | 1041 | 22 | 740 |

| 16/Left | 31 | 644 | 15 | 950 | 14 | 980 | 14 | 896 | 16 | 880 | 31 | 644 |

| 16/Right | 26 | 687 | 15 | 990 | 17 | 1010 | 17 | 1045 | 17 | 880 | 26 | 687 |

| 17/Left | 25 | 520 | 16 | 890 | 18 | 900 | 15 | 960 | 14 | 960 | 25 | 520 |

| 17/Right | 23 | 670 | 16 | 1026 | 18 | 890 | 14 | 960 | 14 | 920 | 23 | 670 |

| 18/Left | 23 | 560 | 17 | 980 | 16 | 870 | 15 | 1000 | 16 | 990 | 23 | 560 |

| 18/Right | 24 | 650 | 18 | 1021 | 16 | 992 | 15 | 890 | 15 | 840 | 24 | 650 |

Figure 1.

Mean (SD) intraocular pressure (IOP) values by treatment group at baseline (day 0) and throughout the study. P<0.01 at all time points versus baseline in both groups. No significant between-group differences were found.

Figure 2.

Mean (SD) pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) values by treatment group at baseline (day 0) and throughout the study. ∗P<0.01 versus baseline. †P<0.05 versus baseline. No significant between-group differences were found.

Table IV.

Mean (SD) values for intraocular pressure (IOP) and pulsatile ocular blood flow (pOBF) by treatment group at baseline and throughout the study.∗†

| Time Point | Travoprost | Latanoprost |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||

| IOP | 23.7(2.8) | 24.1(2.9) |

| pOBF | 709.8(284.1) | 680.8(88.4) |

| Day 15 | ||

| IOP | 18.2(3.2) | 18.6(3.7) |

| pOBF | 1028.3(447.5)‡ | 1006.6(57.7) |

| Day 30 | ||

| IOP | 17.4(2.0) | 17.3(1.8) |

| pOBF | 1026.8 (438.9)‡ | 958.6(66.0) |

| Day 60 | ||

| IOP | 16.3(2.0) | 16.7(1.5) |

| pOBF | 1103.7(434.7) | 958.9(86.6) |

| Day 90 | ||

| IOP | 16.1(1.9) | 16.0(1.5) |

| pOBF | 1060.1(343.4)§ | 926.3(63.0) |

| Day 180 | ||

| IOP | 16.1(1.9) | 16.5(1.7) |

| pOBF | 923.8(240.4)§ | 833.8(85.9) |

No statistically significant between-group differences were found (unpaired t-test).

P<0.01 versus baseline (Dunnett multiple comparison test) unless otherwise indicated.

P=NS versus baseline.

P<0.05 versus baseline.

In both groups, mean IOP was significantly decreased compared with baseline at all time points (all P<0.01). No statistically significant between-group differences in IOP were found at baseline or at any time point throughout the study.

In group T, the mean pOBF increased 44.9% by day 15 and was maintained at that level throughout the remainder of the study (P = NS, NS, <0.01, <0.05, and <0.05 at days 15, 30, 60, 90, and 180, respectively, vs baseline). In group L, mean pOBF increased 47.9% by day 15, was maintained at that level for 60 days, and then progressively decreased throughout the remainder of the study (P<0.01 at all time points vs baseline). A between-group comparison did not show any statistically significant differences in pOBF at any time point.

In group T, an inverse correlation was noted at day 15 (r = −0.49; P = 0.04), whereas in group L a correlation was noted only at 180 days of treatment (r = −0.46; P = 0.05) (Table V).

Table V.

Linear correlation between intraocular pressure and pulsatile ocular blood flow in the 2 treatment groups at baseline and throughout the study.

| Travoprost |

Latanoprost |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Point | r∗ | P | r∗ | P |

| Baseline | −0.39 | 0.11 | −0.48 | 0.85 |

| Day 15 | −0.49 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.82 |

| Day 30 | −0.28 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.12 |

| Day 60 | −0.05 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 0.45 |

| Day 90 | −0.42 | 0.08 | −0.20 | 0.40 |

| Day 180 | −0.49 | 0.04 | −0.46 | 0.05 |

Pearson product moment correlation.

Two patients in group L (22.2%) and 3 in group T (33.3%) developed treatment-related conjunctival hyperemia and itching, both of which resolved spontaneously after 3 weeks of therapy.

Discussion

The prostaglandin analogues latanoprost and travoprost have favorable ocular and systemic safety profiles and are well tolerated.10,14,15 IOP control should not be the sole aim of modern glaucoma therapy. A hypotensive agent that enhances blood flow to the eye and provides neuroprotection would be an optimal therapy because visual field loss continues in some patients despite successful medical or surgical reduction of IOP.16

Measurement of pOBF may provide an indirect estimate of optic nerve blood flow.17,18 pOBF is estimated from the ocular pulse, which is directly proportional to perfusion pressure and inversely related to vascular resistance. Although this pulse mostly reflects choroidal blood flow, the choroidal system is also the main contributor to optic nerve blood flow, accounting for 90% of choroidal circulation but for only 10% of retinal circulation.19,20 The extent of choroidal perfusion varies with the particular glaucoma treatment, and this has a direct effect on optic nerve head perfusion. Therefore, antiglaucomatous treatments can influence long-term tropism of the optic nerve head,21,22 which may be important because pOBF values have been shown to be reduced in patients with POAG.23 Previous studies11,24,25 have demonstrated the efficacy of travoprost and latanoprost in reducing IOP, but none of them have compared the effect on choroidal perfusion. Referring to a previous protocol to assess the influence of brimonidine (ophthalmic) on pOBF,26 we analyzed the effect of travoprost and latanoprost on choroidal perfusion. We demonstrated that treatment with travoprost or latanoprost has a beneficial effect on pOBF, increasing the average flow by day 15 after beginning treatment; moreover, both prostaglandin analogues significantly decreased IOP by day 15 of therapy. The increase in pOBF can be interpreted as a direct consequence of the IOP reduction.27,28

Subsequent flow variations might be related to capillary autoregulation, which is known to exist in the retina and hypothesized to exist in the choroid.29 The diameter of the capillary vessels may change according to perfusion pressure. This could explain the pOBF reduction with time, although pOBF was still increased at 180 days of treatment with latanoprost and travoprost compared with baseline. Considering the influence of IOP on pOBF, only travoprost increased pOBF, reducing IOP. This inverse correlation could be explained by greater specificity of travoprost than latanoprost on IOP and pOBF regulation. In any case, capillary autoregulation may impair this mechanism after 30 days of therapy. After 180 days, other factors seem to reactivate the correlation between IOP and pOBF predominantly in patients treated with travoprost.29 Unfortunately, our data are not adequate because of the short follow-up and the small number of patients to make conclusions regarding tolerability or effects on pOBF. Therefore, additional studies are needed.

All of the patients enrolled in this study had normal hemorheologic values. Because some patients may have vasculopathy and other systemic diseases, it may not be accurate to extrapolate our results to the general patient population.

Conclusions

In this study population, pOBF was increased with travoprost and latanoprost in the short term, but this effect was kept constant only with travoprost. IOP was reduced with both drugs after short-term therapy, and this reduction was maintained in both groups. Travoprost may represent another option for the medical treatment of POAG.

Acknowledgements

This article was sponsored by Alcon S.p.A., Milano, Italy.

Footnotes

Trademark: Travatan® (Alcon, Inc., Dallas, Texas).

Trademark: Xalatan® (Pharmacia Corp., Uppsala, Sweden).

References

- 1.Kuba G.B, Kurnatowski-Billion M, Neuser A.M, Austermann P. Effect of latanoprost on ocular hemodynamics and contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmologe. 2001;98:535–540. doi: 10.1007/s003470170114. [in German] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geyer O, Man O, Weintraub M, Silver D.M. Acute effect of latanoprost on pulsatile ocular blood flow in normal eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:198–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00797-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamaki Y, Nagahara M, Araie M. Topical latanoprost and optic nerve head and retinal circulation in humans. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2001;17:403–411. doi: 10.1089/108076801753266785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishii K, Tomidokoro A, Nagahara M. Effects of topical latanoprost on optic nerve head circulation in rabbits, monkeys, and humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2957–2963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stjernschantz J, Selen G, Astin M, Resul B. Microvascular effects of selective prostaglandin analogues in eye with special reference to latanoprost and glaucoma treatment. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:459–496. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vetrugno M, Cantatore F, Gigante G, Cardia L. Latanoprost 0.005% in POAG: Effects on IOP and ocular blood flow. Acta Ophthalmol Scand Suppl. 1998:40–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1998.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKibbin M, Menage M.J. The effect of once-daily latanoprost on intraocular pressure and pulsatile ocular blood flow in normal tension glaucoma. Eye. 1999;13:31–34. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgopoulos G.T, Diestelhorst M, Fisher R. The short-term effect of latanoprost on intraocular pressure and pulsatile ocular blood flow. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:54–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2002.800111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellberg M.R, Sallee V.L, McLaughlin M.A. Preclinical efficacy of travoprost, a potent and selective FP prostaglandin receptor agonist. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2001;17:421–432. doi: 10.1089/108076801753266802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitson J.T. Travoprost—a new prostaglandin analogue for the treatment of glaucoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:965–977. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellman R.L, Sullivan E.K, Ratliff M. Comparison of travoprost 0.0015% and 0.004% with timolol 0.5% in patients with elevated intraocular pressure: A 6-month, masked, multicenter trial. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:998–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sponsel W.E, Ritch R, Stamper R. Prevent Blindness America visual field screening study. The Prevent Blindness America Glaucoma Advisory Committee. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:699–708. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langham M.E, Farrel L.A, O'Brien V. Blood flow in the human eye. Acta Ophthalmol. 1989;191:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb07080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Netland P.A, Landry T, Sullivan E.K. Travoprost compared with latanoprost and timolol in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:472–484. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aung T, Chew P.T, Yip C.C. A randomized double-masked crossover study comparing latanoprost 0.005% with unoprostone 0.12% in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:636–642. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00943-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoles E, Schwartz M. Potential neuroprotective therapy for glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:367–372. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flammer J, Gasser P, Prunte C.H. The probable involvement of factors other than intraocular pressure in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. In: Drance S.M, Van Buskirk E.M, Neufeld A.H, editors. Pharmacology of Glaucoma. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, Md: 1992. pp. 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayreh S.S. Optic nerve head and blood supply in health and disease. In: Lambrou G.N, Greve E.L, editors. Ocular Blood Flow in Glaucoma: Means, Methods and Measurements. Proceedings of the Meeting of the European Glaucoma Society, September 9–10, 1988, Paris, France. Kugier & Ghedini; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 1989. pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bill A, Sperber G.O. Control of retinal and choroidal blood flow. Eye. 1990;4:319–325. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Büchi E.R. The blood supply to the optic nerve head. In: Kaiser H.J, Flammer J, Hendrickson P, editors. Ocular Blood Flow: New Insights into the Pathogenesis of Ocular Diseases. Glaucoma Meeting, March 24–25, 1995, Basel, Switzerland. Karger; Basel: 1996. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillunat L, Stodtmeister R. Effect of different antiglaucomatous drugs on ocular perfusion pressures. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1988;4:231–242. doi: 10.1089/jop.1988.4.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langham M.E. The influence of timolol, clonidine and aminoclonidine on ocular blood flow in the rabbit and human subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:378. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trew D.R, Smith S.E. Postural studies in pulsatile ocular blood flow:: II. Chronic open angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:71–75. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.2.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons S.T, Earl M.L. Three-month comparison of brimonidine and latanoprost as adjunctive therapy in glaucoma and ocular hypertension patients uncontrolled on beta-blockers: Tolerance and peak intraocular pressure lowering. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orengo-Nania S, Landry T, Von Tress M. Evaluation of travoprost as adjunctive therapy in patients with uncontrolled intraocular pressure while using timolol 0.5% Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:860–868. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetrugno M, Maino A, Cantatore F. Acute and chronic effects of brimonidine 0.2% on intraocular pressure and pulsatile ocular blood flow in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma: An open-label, uncontrolled, prospective study. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1519–1528. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schilder P. Ocular blood flow changes with increased vascular resistance external and internal to the eye. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1989;191:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb07082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hjortdal J.O, Hjortdal V.E, Hansen E.S. Effect of acute intraocular pressure reduction on regional ocular blood flow. Doc Ophthalmol. 1991;77:145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillunat L.E, Stodtmeister R, Wilmanns I, Christ T. Autoregulation of ocular blood flow during changes in intraocular pressure: Preliminary results. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223:219–223. doi: 10.1007/BF02174065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]