Abstract

Background: Chronic peripheral arterial occlusion (CPAO) is a progressive disease that is associated with a variety of symptoms, the 4 most common being a sensation of coolness in the limbs, intermittent claudication (in which pain occurs on walking), limb pain (which occurs spontaneously at rest), and ischemic leg ulcers. Beraprost sodium is an oral prostaglandin I2 analogue that may ameliorate these symptoms.

Objective: The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of beraprost sodium and ticlopidine hydrochloride in the treatment of patients with CPAO in China.

Methods: In this multicenter, single-blind, controlled study, patients with CPAO were randomly assigned to receive beraprost 120-μg tablet TID or ticlopidine 500-mg tablet BID, both administered orally. The clinical efficacy of the drugs was assessed using the 4 main symptoms of CPAO. Ankle-brachial index (ABI) also was measured as a clinical pharmacologic procedure. Adverse events were assessed throughout the study.

Results: A total of 124 patients (96 men, 28 women; mean [SD] age, 65 [12] years) were enrolled in 3 hospitals. Data from 119 patients (93 men, 26 women; mean [SD] age, 65 [12] years) were included in the efficacy analysis (64 and 55 patients in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, respectively). Although all 4 symptoms of CPAO were ameliorated after 3 and 6 weeks of treatment with both drugs, only the cool sensation was significantly improved with beraprost compared with ticlopidine at 6 weeks (P<0.05). ABI was significantly increased with both beraprost and ticlopidine at 6 weeks versus baseline (P<0.001 and P<0.01, respectively), suggesting that this pharmacologic action may have led to their beneficial effect on various symptoms. The tolerability analysis included 123 patients (65 and 58 patients in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, respectively). The numbers of patients who (1) experienced adverse events (AEs), (2) experienced adverse drug reactions, and (3) withdrew due to AEs were significantly smaller in the beraprost group than in the ticlopidine group (P<0.001, P<0.05, and P<0.05, respectively).

Conclusions: In this study population of patients with CPAO, beraprost ameliorated cool sensation in the limbs, intermittent claudication, limb pain, and ischemic/leg ulcers. Beraprost was more efficacious in relieving CPAO symptoms and was better tolerated than ticlopidine. Beraprost may be useful for the treatment of patients with CPAO, but more studies are needed.

Keywords: Beraprost, ticlopidine, prostaglandin I2 analogue, peripheral arterial occlusion

Introduction

Chronic peripheral arterial occlusion (CPAO) occurs in a variety of conditions and is associated with various symptoms, the most common being a sensation of coolness in the limbs, intermittent claudication (in which pain occurs on walking), limb pain (which occurs spontaneously at rest), and ischemic leg ulcers (Fontaine classifications1 I–IV, respectively). Treatment of these symptoms includes surgery2 and pharmacotherapy.3–7 Pharmacotherapy for CPAO has consisted mainly of vasodilating agents to dilate contracted vessels and to stimulate collateral circulation. However, CPAO is a progressive disease, with repeated aggravation and relapse due to thrombus formation secondary to abnormality of the arterial walls.8,9 Therefore, drugs that not only inhibit platelet aggregation but also cause vasodilation may be beneficial in the treatment of this condition.4,10–12

Results of clinical studies of prostaglandin I2 (PGI2) have indicated its efficacy in the treatment of arterial occlusion.13,14 However, because of its chemical instability, PGI2 has been administered by injection or infusion only.9 Furthermore, the high incidence of adverse events (AEs) associated with PGI2 (eg, headache, facial flushing) seems to restrict its applicability in clinical practice.13

Beraprost sodium is the first synthetic PGI2 analogue that is stable and can be administered orally.10,15 Beraprost has both powerful antiplatelet aggregating15–17 and vasodilating18,19 effects; in addition, the drug has antithrombotic,20 anti-inflammatory,21 and cytoprotective effects.22 The clinical efficacy of beraprost has been reported in a number of studies.23–27 Sakaguchi et al24 and Suh et al25 found that beraprost ameliorated various symptoms of arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO) and thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO) with ischemic limb ulceration in patients in Japan24 and Korea,25 respectively.

This study was undertaken to compare the efficacy and tolerability of beraprost sodium and ticlopidine hydrochloride in treating patients in China with a variety of conditions that involve CPAO. Ticlopidine, which is commonly used to treat patients with CPAO, causes antiplatelet aggregation but does not cause vasodilation.12

Patients and methods

This multicenter, single-blind, randomized, controlled study was approved by the ethics committees of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing, China), Zhong Shan Hospital (Shanghai, China), and Ren Ji Hospital (Shanghai, China). Participating physicians informed patients of the details of the study and obtained written informed consent before the start of the study.

Patients

Patients with ASO, TAO, and/or other CPAO diseases who showed at least 1 of 4 symptoms (cool sensation in the limbs, intermittent claudication, limb pain, and ischemic leg ulcers; Fontaine classifications1 I–IV, respectively) were eligible for the study. Although patients whose only symptom is a cool sensation have mild arterial occlusion, those with ischemic leg ulcers have a much more severe type of the disease.

To help ensure that patients with differing characteristics (especially with regard to the severity of their condition) were equally distributed to the 2 treatment groups (beraprost∗ or ticlopidine†), enrolled patients were randomized using a table of random numbers.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had a blood-clotting disorder; severe hepatic or renal insufficiency; any severe, complicated disease; a history of hypersensitivity to drugs; or leukopenia or a history of leukopenia. Patients also were excluded if they were pregnant, possibly pregnant, or lactating, or if they were judged otherwise inappropriate for the study by the participating physicians.

Study design

Patients in the beraprost group received beraprost 120 μg/d (40-μg tablet TID, in the morning, afternoon, and evening), and patients in the ticlopidine group received ticlopidine 500 mg/d (250-mg tablet BID, in the morning and evening) orally for 6 weeks. After patients were randomly assigned to a treatment group, they were observed initially for 2 weeks without medication. The investigators were blinded to the treatments and assessments, which were managed by the study controller.

The following drugs were prohibited during the study period: (1) any drug that was considered to influence the efficacy assessment of the study drugs (eg, antiplatelet-aggregating drugs, vasodilators, anticoagulants, fibrinolytic agents, and antiarteriosclerotic agents); (2) barbiturates, the effect of which is potentially enhanced by ticlopidine; and (3) aspirin (although other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were permitted).

Efficacy analysis

The clinical efficacy of the drugs was assessed using the 4 main symptoms of CPAO mentioned previously. At each visit, investigators asked patients about these symptoms and AEs. Compliance was checked by counting the number of unused tablets returned by the patients at each visit (baseline [week 0] and after 3 and 6 weeks of drug administration).

Symptoms

Cool sensation in the limbs, intermittent claudication, limb pain, and ischemic leg ulcers were assessed at each study visit. Cool sensation in the limbs was assessed on a 5-point scale (0 = no symptoms; 1 = very mild; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe). Limb pain also was assessed on a 5-point scale (0 = no pain; 1 = feel pain rarely; 2 = take analgesics occasionally; 3 = take analgesics constantly; 4 = disturbed sleep due to pain). We employed the scoring methods used by Sakaguchi et al.24 The investigators were trained to assess cool sensation and limb pain before the study.

Intermittent claudication causes impairment of the ability to walk. Patients were equipped with a pedometer and asked to walk under specific conditions (ie, in the flat corridor of the hospital). The walking distance at which intermittent claudication developed was calculated by multiplying the number of steps at the time pain occurred by the average stride length. Thus, spontaneous walking distance was observed, although methods used in the present study may not be completely appropriate because individual patients' level of motivation and overall health were not considered.24 In fact, a completely appropriate method of assessing intermittent claudication does not currently exist.27 Treadmill testing can be used to assess intermittent claudication, but the usefulness of this method is confounded because (1) patients can easily learn optimal treadmill testing so that the results may be better than those that would be obtained during actual walking, and (2) the treadmill must be set up for less strenuous conditions in most elderly patients, causing skewing; therefore, we did not use treadmill testing.

Ulcer size was expressed as the square root of the longest diameter of the ulcer multiplied by the shortest diameter, as described by Sakaguchi et al.24 Previously localized ulcers were photographed in color to allow objective analysis of healing rates.

Ankle-brachial index

In the clinical pharmacologic assessment, ankle-brachial index (ABI) was measured at baseline and after 3 and 6 weeks of drug administration. ABI was calculated by dividing ankle-brachial pressure by blood pressure using a vascular Doppler device (ImexLab 9100™, Nicolet Vascular Inc., Madison, Wisconsin) on the upper leg.

Tolerability analysis

For the tolerability analysis, the following tests were performed at baseline and after 6 weeks of drug administration: red and white blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, and platelet count; serum aspartate and alanine aminotransferases, γ-glutamyltransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, total and direct bilirubin, creatinine, and total cholesterol levels; plasma prothrombin time, triglycerides, sodium, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, potassium, chloride, and alkaliphosphatase levels; and blood urea nitrogen, urine protein, glucose, and urobilinogen levels. When abnormal changes were detected, follow-up tests were to be performed and their causative relation to the study drugs was to be assessed.

Clinical symptoms and abnormal laboratory values that occurred after 6 weeks of treatment but had not been observed before the study were regarded as AEs. Furthermore, they were regarded as adverse drug reactions (ADRs) unless their causative relations with the study drugs could be clearly refuted. The type, severity, time of occurrence, causative relationship with the study drugs, treatment, and changes in AEs were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Scores for cool sensation and limb pain were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Data for walking distance, ulcer size, and ABI were objectively analyzed using the Student t test. Patients' clinical characteristics were analyzed using whichever of these 2 methods was appropriate for each parameter. The Fisher exact test was used to analyze the proportion of patients experiencing AEs. Significance was set at P≤0.05.

Results

A total of 124 patients were enrolled in the study (96 men, 28 women; mean [SD] age, 65 [12] years). The beraprost group comprised 65 patients; the ticlopidine group included 59 patients. Data from 119 patients (93 men, 26 women; mean [SD] age, 65 [12] years) were used to assess efficacy (64 in the beraprost group and 55 in the ticlopidine group), and data from 123 patients (95 men, 28 women; mean [SD] age, 65 [11] years) were used to assess tolerability. The results from 5 (4.0%) patients could not be used to assess efficacy for the following reasons: in the beraprost group, 1 (1.6%) patient was withdrawn from the study for discontinuing hospital visits; in the ticlopidine group, 4 (7.3%) patients withdrew from the study due to ADRs (3 [5.5%] patients developed severe rash and 1 [1.8%] developed hematemesis). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in the efficacy analysis are presented in Table I. No significant differences were found between the 2 groups.

Table I.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of study patients.∗

| Characteristic | Beraprost | Ticlopidine |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients enrolled | 65 | 59 |

| Tolerability population | 65 | 58 |

| Efficacy population | 64 | 55 |

| Characteristics of the efficacy population (n = 119), no. patients (%) | ||

| Age group, mean (SD)† | 66.8 (12) | 64.0 (12) |

| 20–50 y | 6 (9.4) | 11 (20.0) |

| 51–75 y | 58 (90.6) | 44 (80.0) |

| Sex† | ||

| Men | 52 (81.3) | 41 (74.5) |

| Women | 12 (18.8) | 14 (25.5) |

| Disease | ||

| Arteriosclerosis obliterans | 57 (89.1) | 43 (78.2) |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans | 6 (9.4) | 5 (9.1) |

| Diabetic arterial occlusion | 1 (1.6) | 3 (5.5) |

| Aortitis | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.5) |

| Underdeveloped arteries | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Lower leg arterial surgery† | 17 (26.6) | 14 (25.5) |

| Symptoms† | ||

| Cool sensation in limbs (I‡) | 54 (84.4) | 45 (81.8) |

| Intermittent claudication (II‡) | 64 (100.0) | 55 (100.0) |

| Limb pain (III‡) | 41 (64.1) | 29 (52.7) |

| Ischemic leg ulcer (IV‡) | 7 (10.9) | 5 (9.1) |

| Disease duration† | ||

| <5 y | 45 (70.3) | 40 (72.7) |

| 5–30 y | 19 (29.7) | 15 (27.3) |

No significant between-group differences were found.

Data unavailable in 1 patient (1.5%) in the beraprost group and 4 patients (6.8%) in the ticlopidine group.

Fontaine classification.1

A total of 84.9% (101/119) of the patients included in the efficacy analysis had cool sensation, limb pain, or both, whereas 15.1% (18/119) of patients (8 [12.5%] beraprost-treated and 10 [18.2%] ticlopidine-treated patients) did not have either of these symptoms. In these 18 patients, drug efficacy was assessed only by walking distance.

Efficacy analysis

Cool sensation

At baseline, cool sensation (median score, 2 in both groups) was reported by 54 (84.4%) and 45 (81.8%) beraprost- and ticlopidine-treated patients, respectively (Table II). Compared with baseline, this score was significantly decreased in both the beraprost and ticlopidine groups at 3 weeks (median score, 2 in both groups; both P<0.001) and 6 weeks (median score, 1 in both groups; both P<0.001) of treatment.

Table II.

Efficacy of beraprost and ticlopidine treatment in patients with chronic peripheral arterial occlusion.

| Time Point/Drug | Cool Sensation Score, Median∗ | Intermittent Claudication, Mean (SE), m† | Limb Pain Score, Median‡ | Ischemic Leg Ulcer Size, Mean (SE), mm2 | Ankle-Brachial Index, Mean (SE)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||

| Beraprost | 2 (n = 54) | 215 (30) (n = 64) | 2 (n = 41) | 1092 (880) (n = 7) | 0.55 (0.03) (n = 58) |

| Ticlopidine | 2 (n = 45) | 230 (31) (n = 55) | 2 (n = 29) | 147 (90) (n = 5) | 0.61 (0.03) (n = 49) |

| 3 Weeks | |||||

| Beraprost | 2 (n = 54)∥ | 287 (36) (n = 64)∥ | 1 (n = 41)∥ | 942 (767) (n = 7) | 0.59 (0.03) (n = 58)¶ |

| Ticlopidine | 2 (n = 55)∥ | 258 (32) (n = 55)∥ | 1 (n = 29)# | 135 (107) (n = 5) | 0.64 (0.03) (n = 49) |

| 6 Weeks | |||||

| Beraprost | 1 (n = 52)∥ | 356 (50) (n = 62)∥ | 1 (n = 40)∥ | 705 (560) (n = 7) | 0.60 (0.03) (n = 49)∥ |

| Ticlopidine | 1 (n = 43)∥ | 292 (47) (n = 52)# | 1 (n = 27)# | 117 (125) (n = 4) | 0.65 (0.03) (n = 47)# |

Cool sensation scale: 0=no symptoms; 1=very mild; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe.

Measured as walking distance at which intermittent claudication appeared.

Limb pain scale: 0=no pain; 1=feel pain rarely; 2=take analgesics occasionally; 3=take analgesics constantly; 4=disturbed sleep due to pain.

Ankle-brachial index was calculated by dividing ankle-brachial pressure by blood pressure using a vascular Doppler device (ImexLab 9100™, Nicolet Vascular Inc., Madison, Wisconsin) on the upper leg.

P<0.001 versus baseline.

P<0.01 versus baseline.

P<0.05 versus baseline.

At 6 weeks of treatment, the change in median cool sensation score in the beraprost group was significantly greater than that in the ticlopidine group (change in median score, −1 and 0 in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, respectively; both P<0.05) (Table III, Figure 1). In patients with ASO, a significant difference was found between the beraprost and ticlopidine groups in change in median cool sensation score at 6 weeks of treatment (change in median score, −1 and 0 in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, respectively; P<0.05) (data not shown). Because in our study the number of patients with TAO was small (n = 10), we do not provide a detailed discussion of these results.

Table III.

Changes in the values of the efficacy indicators.∗

| Time Point/Drug | Cool Sensation Score, Median† | Intermittent Claudication, Mean (SE), m‡ | Limb Pain Score, Median§ | Ischemic Leg Ulcer Size, Mean (SE), mm2 | Ankle-Brachial Index, Mean (SE)∥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Weeks | |||||

| Beraprost | −1 (n = 54) | 72 (13) (n = 64)¶ | 0 (n = 41) | −150 (114) (n = 7) | 0.04 (0.01) (n = 58) |

| Ticlopidine | 0 (n = 45) | 27 (7) (n = 55) | 0 (n = 29) | −12 (20) (n = 5) | 0.02 (0.02) (n = 49) |

| 6 Weeks | |||||

| Beraprost | −1 (n = 52)# | 138 (30) (n = 62) | −1 (n = 40) | −387 (323) (n = 7) | 0.06 (0.01) (n = 49) |

| Ticlopidine | 0 (n = 43) | 67 (28) (n = 52) | −1 (n = 27) | −30 (26) (n = 4) | 0.05 (0.02) (n = 47) |

These values were calculated by subtracting individual patients' values at 3 and 6 weeks from those at baseline, and then calculating the median or mean (SE) difference; they were not derived from subtracting the mean scores at 3 and 6 weeks from the mean baseline scores shown in Table II.

Cool sensation scale: 0=no symptoms; 1=very mild; 2=mild; 3=moderate; 4=severe.

Measured as walking distance at which intermittent claudication appeared.

Limb pain scale: 0=no pain; 1=feel pain rarely; 2=take analgesics occasionally; 3=take analgesics constantly; 4=disturbed sleep due to pain.

Ankle-brachial index was calculated by dividing ankle-brachial pressure by blood pressure using a vascular Doppler device (ImexLab 9100™, Nicolet Vascular Inc., Madison, Wisconsin) on the upper leg.

P<0.01 versus ticlopidine (Student t test).

P<0.05 versus ticlopidine (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Figure 1.

Change in each patient's score for cool sensation in the limbs after 3 and 6 weeks of treatment with beraprost or ticlopidine in study patients. ∗P<0.05 between groups (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

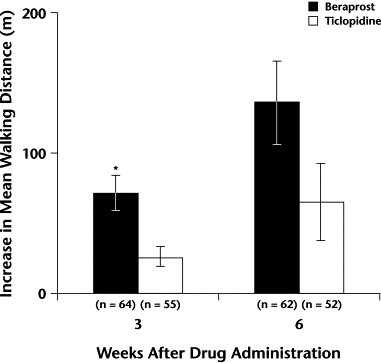

Intermittent claudication

At baseline, intermittent claudication (as measured by walking distance) was seen in all 119 patients (100.0%) included in the efficacy analysis (mean [SE] walking distance at which intermittent claudication appeared, 215 [30] m and 230 [31] m in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, respectively). Compared with baseline, a significantly prolonged mean (SE) walking distance was found in the beraprost group at 3 weeks (287 [36] m; P<0.001) and 6 weeks (356 [50] m; P<0.001) of treatment. A significantly longer mean (SE) walking distance also was found in the ticlopidine group at 3 weeks (258 [32] m; P<0.001) and 6 weeks (292 [47] m; P<0.05) (Table II).

The change in mean [SE] walking distance of beraprost was significantly greater than that of ticlopidine at 3 weeks of treatment (72 [13] m vs 27 [7] m, respectively; P<0.01) (Table III, Figure 2). In patients with ASO, a significant difference was also found between beraprost and ticlopidine in change in mean (SE) walking distance at 3 weeks (66 [13] vs 21 [5]; P<0.01) and 6 weeks (135 [33] vs 30 [8]; P<0.01) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mean increase in walking distance after 3 and 6 weeks of treatment with beraprost or ticlopidine in study patients. ∗P<0.01 versus ticlopidine (Student t test).

Limb pain

At baseline, limb pain was reported by 41 beraprost-treated patients (64.1%) and 29 ticlopidine-treated patients (52.7%) (median score, 2 in both groups). Compared with baseline, a significantly lower median limb pain score was found in the beraprost group at 3 weeks (median score, 1; P<0.001) and 6 weeks (median score, 1; P<0.001) of treatment. A significantly lower median limb pain score also was found in the ticlopidine group at 3 weeks (median score, 1; P<0.05) and 6 weeks (median score, 1; P<0.01) versus baseline (Table II).

The change in median limb pain score of beraprost was similar to that of ticlopidine after 3 weeks (change in median score, −1 in both groups) and 6 weeks (change in median score, −1 in both groups) (Table III). Analysis of patients with ASO did not show any significant changes.

Ischemic leg ulcers

At baseline, ischemic leg ulcers were present in 7 beraprost-treated patients (10.9%) and 5 ticlopidine-treated patients (9.1%) (mean [SE] ulcer size, 1092 [880] mm2 and 147 [90] mm2, respectively). Compared with baseline, ulcer size was similar at 3 and 6 weeks of treatment in both groups (Table II).

The change in mean size of ischemic leg ulcer in the beraprost group was similar to that in the ticlopidine group at 3 and 6 weeks (Table III).

Ankle-brachial index

At baseline in the beraprost and ticlopidine groups, ABI data were available for 58 (90.6%) and 49 (89.1%) patients, respectively (mean [SE] ABI, 0.55 [0.03] and 0.61 [0.03], respectively). ABI data were unavailable for most patients because of technical difficulties with the Doppler device. Compared with baseline, mean (SE) ABI was significantly higher in the beraprost group at 3 weeks (0.59 [0.03]; P<0.01) and 6 weeks (0.60 [0.03]; P<0.001) of treatment. In the ticlopidine group, ABI also was significantly higher versus baseline at 6 weeks (0.65 [0.03]; P<0.01) (Table II).

The change in mean ABI of beraprost was similar to that of ticlopidine at 3 and 6 weeks (Table III). Analysis of patients with ASO did not show any significant changes.

Tolerability analysis

Eight of 65 beraprost-treated patients (12.3%) and 25 of 58 ticlopidine-treated patients (43.1%) experienced AEs (P<0.001) (Table IV). Four beraprost-treated patients (6.2%) and 13 ticlopidine-treated patients (22.4%) experienced ADRs (P<0.05). In the beraprost group, dizziness, headache, facial flushing, and tachycardia occurred in 2 (3.1%), 2 (3.1%), 1 (1.5%), and 1 (1.5%) patient, respectively. These clinical ADRs were mild and transient. ADRs in the ticlopidine group included hematemesis, rash, and diarrhea in 1 (1.7%), 4 (6.9%), and 1 (1.7%) patient, respectively. Because the hematemesis and rash were severe, these 5 patients (8.6%) withdrew from the study, whereas none of the patients in the beraprost group withdrew due to AEs or ADRs (P<0.05).

Table IV.

Number (%) of patients experiencing adverse events (AEs) or adverse drug reactions (ADRs). All values are expressed as no. [%] of patients unless otherwise noted.

| Variable | Beraprost (n = 65) | Ticlopidine (n = 58) | P∗ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | |||

| Patients experiencing >1 AE or ADR | 7 (10.8) | 7 (12.1) | NS |

| Treatment-related | 6 (9.2) | 6 (10.3) | NS |

| Dizziness | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Headache | 2 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Facial flushing | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Tachycardia | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Hematemesis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7)† | NS |

| Rash | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.9)† | <0.05 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | NS |

| Laboratory | |||

| Patients experiencing >1 AE or ADR | 3 (4.6) | 24 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| Treatment-related | 0 (0.0) | 11 (19.0) | <0.001 |

| ↓Leukocytes | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.2) | NS |

| ↑BUN | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | NS |

| ↑ALT | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.2) | NS |

| ↑AST | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.2) | NS |

| ↑Creatinine | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | NS |

| Total patients experiencing AEs | 8 (12.3) | 25 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Total AEs, no. | 10 | 31 | <0.001 |

| Total patients experiencing ADRs | 4 (6.2) | 13 (22.4) | <0.05 |

| Total ADRs, no. | 6 | 17 | <0.01 |

| Withdrawals due to AEs | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.6) | <0.05 |

BUN = blood urea nitrogen; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase.

Between-group difference (Fisher exact test).

These patients withdrew due to this AE.

No drug-related abnormal laboratory values were observed in the beraprost group, whereas 11 abnormal values were observed in the ticlopidine group (P<0.001).

Discussion

Based on the Fontaine classifications,1 the symptoms observed in the present study were generally mild to moderate. Both beraprost and ticlopidine ameliorated cool sensation and limb pain while improving intermittent claudication in patients with CPAO. The number of patients with ischemic leg ulcers was small. The ulcers decreased in size in both treatment groups, although the change was not statistically significant in either group. These 2 results may be due, in part, to increases in the ABI that resulted from the treatment. Beraprost and ticlopidine have been reported to improve the various symptoms of severe CPAO in both Japanese24 and Korean25 patients. Our results from this study in Chinese patients are similar to those in the Japanese and Korean studies.

Beraprost was significantly more effective than ticlopidine in improving cool sensation in the limbs and intermittent claudication; however, both drugs had similar efficacy with regard to limb pain and healing of ischemic leg ulcers. These results suggest that beraprost may ameliorate the symptoms somewhat more than ticlopidine in patients with mild to moderate CPAO. Sakaguchi et al24 reported that significantly more beraprost-treated patients than ticlopidine-treated patients were moderately or markedly improved when the appearance of leg ulcer granulation tissue was assessed (67.1% vs 50.6%, respectively; P<0.05). Beraprost also received higher general efficacy satisfaction ratings from patients (67.6% vs 49.4%, respectively; P<0.05), but no significant differences were found between the groups in the overall end point analyses of final global improvement and usefulness of the drug.

As previously stated, in our study a significant difference in effect on cool sensation in the limbs was observed between the 2 drugs. This difference was observed both in patients with ASO and in those with general CPAO. Sakaguchi et al24 reported that although the improvement rate for ASO in the beraprost group was similar to that in the ticlopidine group, the improvement rate for patients with TAO in the beraprost group (62.9%), was higher than that in the ticlopidine group (45.7%). Those authors24 also reported that platelet aggregation–inhibiting drugs have equivalent effects in patients with either TAO or ASO, whereas vasodilating drugs have been shown by other authors26 to be more effective in patients with TAO. In patients with ASO, sclerotic damage develops in the collateral circulatory system or the arteriolae peripheral to the obstructed artery, which may cause resistance to drug therapy and result in poor improvement of blood flow. Again, in our study, because the number of patients with TAO was small (n = 10), we did not provide a detailed discussion of these results. Unlike Sakaguchi et al,24 we noted a significant difference in effect on cool sensation in the limbs and intermittent claudication between the 2 drugs in patients with ASO.

The clinical effects of beraprost may be ascribed to its broader pharmacologic activity compared with ticlopidine. Although beraprost inhibits platelet aggregation15–17 and increases vasodilatory activity,18,19 ticlopidine works mainly by the former.12,24 Due to its vasodilatory action, beraprost induced facial flushing and dizziness, which were considered ADRs in 5 of 65 patients in the beraprost group. Ticlopidine was not associated with these ADRs. The present results support previous studies that found both beraprost24 and cilostazole26 had vasodilatory and antiplatelet-aggregating activity and ameliorated symptoms of CPAO significantly more than ticlopidine, suggesting that drugs with both actions are beneficial in the treatment of patients with this condition.

The number of patients who developed AEs and abnormal laboratory biochemical values after treatment was significantly smaller in the beraprost group than in the ticlopidine group. Similarly, the incidence of ADRs and the number of patients who dropped out due to an ADR was significantly smaller in the beraprost group. Clinical symptoms (ie, headache, dizziness, and facial flushing) that developed in some patients in the beraprost group were apparently due to vasodilation.18,19 These symptoms were transient and not severe. Relatively severe rash developed in some of the ticlopidine-treated patients, who withdrew because of it. Beraprost had little effect on biochemical values, whereas 11 of 58 patients (19.0%) in the ticlopidine group developed treatment-related abnormal laboratory biochemical values. Similar findings have been reported in other studies.25,27,28

Conclusions

In this study population of patients with CPAO, beraprost ameliorated cool sensation in the limbs, intermittent claudication, limb pain, and ischemic leg ulcer. Beraprost was more efficacious in some patients in relieving symptoms (eg, cool sensation and intermittent claudication) and was better tolerated than ticlopidine. Beraprost may be useful for the treatment of patients with CPAO, but more studies are needed.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, and Shenyang Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Beijing, China.

The authors thank Yukiko Funatsu for statistical analysis and Junjie Liu for supporting the clinical study.

Footnotes

Trademark: Dorner® (Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Trademark: Ticlid® (Hangzhou Sanofi-Synthelabo Minsheng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, People's Republic of China).

References

- 1.Itoh M, Mishima Y. Arteriosclerosis obliterans. Geriatr Med. 1995;33:875–880. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virgolini I, Fitscha P, Linet O.I. A double blind placebo controlled trial of intravenous prostacyclin (PGI2) in 108 patients with ischaemic peripheral vascular disease. Prostaglandins. 1990;39:657–664. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(90)90025-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara D.B, Champion H.C, Kadowitz P.J. Pharmacologic management of peripheral vascular disease. Surg Clin North Am. 1998;78:447–464. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitz J.I, Byrne J, Clagett G.P. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: A critical review. Circulation. 1996;94:3026–3049. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiatt W.R. New treatment options in intermittent claudication: The US experience. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2001:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belch J.J, Bell P.R, Creissen D. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of AS-013, a prostaglandin E1 prodrug, in patients with intermittent claudication. Circulation. 1997;95:2298–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.9.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiatt W.R. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608–1621. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melian E.B, Goa K.L. Beraprost: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drugs. 2002;62:107–133. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200262010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowkes F.G. Epidemiology of atherosclerotic disease in the lower limbs. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1988;2:283–291. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(88)80002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowkes F.G, Houseley E, Cawood E.H, for Edinburgh Artery Study Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:384–392. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toda N. Beraprost sodium. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 1988;6:222–238. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller B. Pharmacology of thromboxane A2, prostacyclin and other eicosanoids in the cardiovascular system. Therapie. 1991;46:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nony P, Ffrench P, Girard P. Platelet-aggregation inhibition and hemodynamic effects of beraprost sodium, a new oral prostacyclin derivative: A study in healthy male subjects. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:887–893. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-74-8-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szczeklik A, Nizankowski R, Skawinski S. Successful therapy of advanced arteriosclerosis obliterans with prostacyclin. Lancet. 1979;1:1111–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)91792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Yatomi Y, Satoh K, Ozaki Y. Inhibitory effects of beraprost on platelet aggregation: Comparative study utilizing two methods of aggregometry. Thromb Res. 1999;94:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00187-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umetsu T, Murata T, Nishio S. Studies on the antiplatelet effect of the stable epoprostenol analogue beraprost sodium and its mechanism of action in rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 1989;39:68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirasawa Y, Nishio M, Maeda K. Comparison of antiplatelet effects of FK409, a spontaneous nitric oxide releaser, with those of TRK-100, a prostacyclin analogue. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;272:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)0062s-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiba T, Miyazaki M, Toda N. Vasodilator actions of TRK-100, a new prostaglandin I2 analogue. Br J Pharmacol. 1986;89:703–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb11174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexandrou K, Hata Y, Matsuka K. The effect of washout perfusion with beraprost sodium on the no-reflow phenomenon in the rat island flap. Eur J Plast Surg. 1996;19:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murai T, Muraoka K, Saga K. Effect of beraprost sodium on peripheral circulation insufficiency in rats and rabbits. Arzneimittelforschung. 1989;39:856–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ueno Y, Koike H, Annoh S, Nishio S. Anti-inflammatory effects of beraprost sodium, a stable analogue of PGI2, and its mechanisms. Prostaglandins. 1997;53:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(97)89601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi J, Ishida N, Sato H. Effect of beraprost, a stable prostacyclin analogue, on red blood cell deformability impairment in the presence of hypercholesterolemia in rabbits. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;27:527–531. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okuyama M, Kambayashi J, Sakon M. PGI2 analogue, sodium beraprost, suppresses superoxide generation in human neutrophils by inhibiting p47phox phosphorylation. Life Sci. 1995;57:1051–1059. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02050-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakaguchi S, Tanabe T, Mishima Y. An evaluation of the clinical efficacy of beraprost sodium (a PGI2 analogue) for chronic arterial occlusion. Jpn J Clin Exp Med. 1990;67:575–584. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh B.Y, Kwun K.B, Kwun T.W. Open-label, uncontrolled, 6-week clinical trial of beraprost in patients with chronic occlusive arterial disease. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1998;59:645–653. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radack K, Wyderski R.J. Conservative management of intermittent claudication. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:135–146. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-2-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cariski A.T. Cilostazole: A novel treatment option in intermittent claudication. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2001:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katsumura T, Mishima Y, Kamiya K. Therapeutic effect of ticlopidine, a new inhibitor of platelet aggregation, on chronic arterial occlusive disease: A double-blind study versus placebo. Angiology. 1982;33:357–367. doi: 10.1177/000331978203300601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]