Abstract

Introduction

Our efforts to prevent and treat breast cancer are significantly impeded by a lack of knowledge of the biology and developmental genetics of the normal mammary gland. In order to provide the specimens that will facilitate such an understanding, The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Cancer Center (KTB) was established. The KTB is, to our knowledge, the only biorepository in the world prospectively established to collect normal, healthy breast tissue from volunteer donors. As a first initiative toward a molecular understanding of the biology and developmental genetics of the normal mammary gland, the effect of the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraceptives on DNA expression in the normal breast epithelium was examined.

Methods

Using normal breast tissue from 20 premenopausal donors to KTB, the changes in the mRNA of the normal breast epithelium as a function of phase of the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraception were assayed using next-generation whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq).

Results

In total, 255 genes representing 1.4% of all genes were deemed to have statistically significant differential expression between the two phases of the menstrual cycle. The overwhelming majority (221; 87%) of the genes have higher expression during the luteal phase. These data provide important insights into the processes occurring during each phase of the menstrual cycle. There was only a single gene significantly differentially expressed when comparing the epithelium of women using hormonal contraception to those in the luteal phase.

Conclusions

We have taken advantage of a unique research resource, the KTB, to complete the first-ever next-generation transcriptome sequencing of the epithelial compartment of 20 normal human breast specimens. This work has produced a comprehensive catalog of the differences in the expression of protein-coding genes as a function of the phase of the menstrual cycle. These data constitute the beginning of a reference data set of the normal mammary gland, which can be consulted for comparison with data developed from malignant specimens, or to mine the effects of the hormonal flux that occurs during the menstrual cycle.

Introduction

In 1997, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) convened a meeting of researchers from academia, industry and government, and representatives of the patient advocate community. The purpose of the meeting was to identify deficiencies that would have to be addressed if we are to continue and accelerate progress in treating breast cancer, and ultimately, to prevent this disease. Thirteen deficiencies were identified, the first of which was as follows:

‘Our limited understanding of the biology and developmental genetics of the normal mammary gland is a barrier to progress. …it is now clear that a more complete understanding of the normal mammary gland at each stage of development—from infancy through adulthood—will be a critical underpinning of continued advances in detecting, preventing, and treating breast cancer[1]’.

The ideal approach to end the scourge of breast cancer would be to prevent it. Annual age-adjusted breast cancer incidence rates in the United States are a testament to the lack of effective prevention strategies [2]. Current breast cancer prevention strategies fall into one of three categories: lifestyle modification, surgical intervention, and chemoprevention. Lifestyle modifications are directed at women with the general population risk of breast cancer, and modifications include limiting postmenopausal weight gain and moderation of alcohol intake. Surgical intervention, by convention, has been limited to those women estimated to be at substantially increased risk of breast cancer, including women with known or suspected germline mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2, or a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer among first- and second-degree relatives. Surgical interventions include bilateral prophylactic mastectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or a combination of both procedures. Multiple chemoprevention trials examining the efficacy of tamoxifen (for example, NSABP-P1, IBIS-1), raloxifene (MORE, CORE, STAR) and aromatase inhibitors have been completed [3-9]. All chemopreventative agents identified to date, with a single exception, were introduced into the clinic as breast cancer treatments; a significant reduction in the rate of contralateral breast cancer in treated patients was used as an indication that these treatments also act to prevent breast cancer. Few, if any, interventions are based on an understanding of breast cancer risk or of how risk is transduced at the molecular level.

The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the Indiana University (IU) Simon Cancer Center (KTB, The Bank) was established expressly as a resource to be used to address the deficiency identified by the NCI’s Progress Review Group and stated above [10]. To the best of our knowledge, the KTB has the largest and most varied collection of normal breast tissue in the world. The KTB was organized as a clinical trial, and specimens are obtained under broad consent. Healthy volunteer women are recruited by flyer, workplace newsletter, and email solicitation by friends and acquaintances. Donors present to a clinic on a weekend day. They fill out a questionnaire, which provides detailed information on their menstrual history, reproductive history, personal health history, medication usage and family history of breast, ovarian and other cancers. Blood is obtained and processed for leukocyte DNA, as well as for serum and plasma. Breast tissue acquisition is done utilizing a 10-gauge breast biopsy system. Three tissue cores are fresh frozen in liquid nitrogen within five minutes of extraction and a fourth is fixed in formalin and paraffin-embedded (FFPE).

As a first initiative toward a molecular understanding of the biology and developmental genetics of the normal mammary gland, the effect of the menstrual cycle and hormonal contraception on DNA expression in the normal breast epithelium was examined. The normal epithelium was chosen for sequencing for two major purposes: 1) to determine how DNA expression changes as a consequence of the menstrual cycle in the functional unit of the breast, that is, the ductal/lobular epithelium; and 2) anticipating that this sequencing information would be used as a normal control in breast cancer experiments, the epithelium was deemed to be the best comparator as it is hypothesized that breast cancer originates in the terminal ductal lobular unit of the epithelium. This manuscript reports the findings for protein-coding genes.

The human mammary gland undergoes rounds of proliferation, differentiation, and regression/involution in response to cyclic fluctuations in the concentration of ovarian steroidal hormones. Much of what is known about the specific changes in the normal mammary gland as a function of these hormones comes from the study of other mammals [11,12]. A large proportion of our knowledge of menstrual cycle effects in the human breast comes from histologic observations [13], and studies of markers of proliferation and apoptosis. It is known that the mitotic index is low during the follicular phase with the peak of mitotic activity occurring in the mid to late luteal phase [14,15]. In the event that a pregnancy does not occur, to prevent hyperplasia following the cell proliferation of the luteal phase, apoptosis must be activated to clear the superfluous cells. There is evidence to suggest that apoptosis occurs during the luteal phase [16], while other researchers have found no differences between the phases [17]. With the identification of the breast stem cell, attention has turned to the effect of the menstrual cycle on this cell and its niche. Asselin-Labat and colleagues demonstrated markedly decreased murine mammary stem cell numbers and outgrowth potential as a consequence of the elimination of steroidal hormones following ovariectomy [18]. Joshi et al. observed that the number of mouse ‘mammary stem cell-enriched basal cells’ increases at diestrus or following the administration of exogenous progesterone [19]. Breast malignancies also appear to be affected. Murine breast cancers fluctuate in size as a function of the menstrual cycle, thought likely a consequence of the periodic proliferation and apoptosis driven by the hormone flux [20]. Human tumors show increased proliferative activity as a function of the menstrual cycle [21], but measures of apoptosis remain unchanged [22].

Materials and methods

All studies were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB-04, protocol number 0709–17; IRB-01, protocol number 1110007030). All research was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Donors provide broad consent for the use of their specimens in research. The consent document informs the donor that the donated specimens and medical data will be used ‘for the general purpose of helping to determine how breast cancer develops’. It is explained in the consent that the exact laboratory experiments are unknown at the time of donation, and that proposals for use of the specimens will be reviewed and approved by a panel of ‘independent researchers’ before specimens and/or data are released for research purposes.

Premenopausal donors to the KTB were identified by a query of the Bank’s database. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of the FFPE tissue of the identified donors were reviewed and tissue was graded on the basis of the abundance of epithelium within the section. Only cores containing abundant epithelium were considered for this study. Based on dates, the specimens of nine women in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and five in the luteal phase were chosen (Table 1). Six donors using hormonal contraception at the time of donation were also included (Table 1). Whole blood obtained from 19 of the 20 donors at the time of tissue donation was processed for serum. Estradiol, estriol, luteinizing hormone (LH) and progesterone concentrations were determined by the IU Health Pathology Laboratory using a Beckman Unicel DxI 800 Immunoassay System (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The phase of the menstrual cycle was verified by serum progesterone concentration (Table 1). The epithelium of these 20 specimens was microdissected from multiple 8 micron thick frozen tissue sections. Total RNA extracted from the tissue was subsequently depleted of rRNA via locked nucleic acid probes (see Additional file 1). This enabled profiling of both poly-A and non-poly-A RNA species. Barcoded cDNA libraries from the 20 normal breast epithelia were prepared and sequenced on an Applied Biosystems (AB) SOLiD 3 or SOLiD 4 platform (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) (Table S1 in Additional file 2). Whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) reads for each sample were then mapped to the human genome (hg19) using the LifeScope software version 2.5.1 (Life Technologies) and Binary Alignment/Map (BAM) files were generated. The files can be accessed using the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) [23,24], study accession number phs000644.v1.p1. Read counts for each gene were derived from the output BAM files using the RefSeq database (UCSC Genome Brower) as the gene model. The total number of reads and the mapped reads are provided in Table S2 in Additional file 2; the raw read counts of the individual genes are listed in Table S3 in Additional file 2.

Table 1.

Age, menstrual phase data and hormonal contraception (HC) formulation

| Sequencing ID | Age | Menstrual day | HC | HC type | F or L | Estradiol pg/mL | Progesterone ng/mL | LH milliunits/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal_1 |

37 |

5 |

no |

|

F |

49 |

0.5 |

5.7 |

| Normal_2 |

20 |

14 |

yes |

Tri-Legest Fe |

- |

32 |

1.5 |

9.6 |

| Normal_3 |

30 |

13 |

no |

|

F |

32 |

<0.01 |

3.6 |

| Normal_4 |

44 |

19 |

yes |

Ortho Tri-Cyclen Lo |

- |

432 |

0.4 |

5.1 |

| Normal_5 |

40 |

9 |

no |

|

F |

28 |

0.5 |

5.6 |

| Normal_6 |

27 |

27 |

yes |

Nuvaring |

- |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| Normal_7 |

23 |

29 |

no |

|

L |

71 |

6.1 |

3.2 |

| Normal_8 |

27 |

25 |

no |

|

L |

82 |

3.7 |

4.9 |

| Normal_9 |

39 |

4 |

no |

|

F |

198 |

0.1 |

N/A |

| Normal_10 |

38 |

26 |

no |

|

L |

131 |

21.4 |

3 |

| Normal_11 |

22 |

28 |

yes |

Necon1-35 |

- |

36 |

1.1 |

0.2 |

| Normal_12 |

45 |

27 |

no |

|

L |

47 |

2.9 |

3.6 |

| Normal_13 |

19 |

7 |

yes |

Zenchent |

- |

26 |

0.7 |

2.4 |

| Normal_14 |

36 |

2 |

no |

|

F |

53 |

0.6 |

4.4 |

| Normal_15 |

26 |

9 |

no |

|

F |

43 |

0.9 |

10.3 |

| Normal_16 |

22 |

29 |

no |

|

L |

136 |

12.4 |

5.3 |

| Normal_17 |

46 |

6 |

no |

|

F |

121 |

0.5 |

5.6 |

| Normal_18 |

31 |

29 |

yes |

LoEstrin 24 |

- |

34 |

1.1 |

2 |

| Normal_19 |

29 |

2 |

no |

|

F |

61 |

0.6 |

7.9 |

| Normal_20 |

21 |

7 |

no |

|

F |

43 |

0.3 |

3.5 |

|

HC type | ||||||||

| Tri-Legest Fe |

1 mg norethindrone acetate and 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol × 1 week; 1 mg norethindrone acetate and 30 mcg ethinyl estradiol × 1 week; 1 mg norethindrone acetate and 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol × 1 week |

|||||||

| Ortho Tri-Cyclen Lo |

0.180 mg of norgestimate and 0.025 mg ethinyl estradiol × 1 week; 0.215 mg of norgestimate and 0.025 mg ethinyl estradiol × 1 week; 0.250 mg of norgestimate and 0.025 mg of ethinyl estradiol × 1 week |

|||||||

| Nuvaring |

|

|||||||

| Necon1-35 |

Norethindrone 1 mg, ethinyl estradiol 35 mcg |

|||||||

| Zenchent |

0.4 mg norethindrone and 0.035 mg ethinyl estradiol |

|||||||

| LoEstrin 24 | 1 mg norethindrone acetate and 20 mcg ethinyl estradiol | |||||||

Menstrual day was calculated from information provided by the donor on her questionnaire and verified by serum progesterone concentration. F, follicular; L, luteal; LH, luteinizing hormone.

The original data comprised 25,203 sequenced genes, many of which exhibit very low expression levels. Omitting low-expression genes that contribute little to the analysis yields a more powerful statistical test overall, that is, the asymptotic theory required by the statistical tests is satisfied. Genes that had average counts greater than 5 across all samples were retained for analysis. A total of 7,208 genes were removed based upon this criterion (28.6% of the original number); 17,995 genes remained for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Differential expression (DE) was tested using the Bioconductor package edgeR in R (v. 2.15). A negative binomial (NB) distribution was employed to model the count data generated from the RNA-Seq experiments.

Three similar general linear models were employed to test a set of three hypotheses. In addition to modeling the effects of membership in the groups of interest (luteal phase, follicular phase, and contraceptives), terms are also included to model the effects of batch membership. Specifically, Batch 1 (samples 1 through 10) acts as the baseline for comparison, and the coefficients for Batch 2 (samples 11 through 20 except 19) and Batch 3 (sample 19) indicate departures from that baseline. These terms ensure that the systematic differences in expression that are present between batches, including differences due to single-end versus paired-end reads, are not falsely attributed to differential expression between the actual groups of interest. Details are provided in Additional file 1.

There are situations when a set of genes is highly expressed in one sample but not in another. When this occurs, the remainder of the genes in the first sample would be ‘under-sampled’, and thus creates a potential bias due to its particular RNA composition. To prevent this occurring, and from skewing the DE analysis and results, the data was normalized using an empirical approach that estimates bias [23]. The scaling factors that were estimated ranged from 0.4402 to 1.3760 across the 20 samples; the departure of these factors from 1 indicates the presence of compositional differences between libraries.

The NB model includes ψg as a dispersion parameter. Initially a common dispersion was estimated, which is the average ψg across all genes, and then this was extended by estimating a separate dispersion for each individual gene. This was done using an empirical Bayes method that ‘squeezes’ the gene-wise dispersions toward the common dispersion, thus allowing for information borrowing from other genes [25].

Adjustments for multiple testing

Since a separate statistical test is performed for all of the 17,995 genes, it is necessary to adjust the P values for multiple testing (to control the Type I error rates across the ‘family’ of genes rather than for ‘each’ gene). This was accomplished using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the expected proportion of incorrectly rejected null hypotheses, also known as the false discovery rate (FDR) [25].

Residual RNA from specimens 11 to 20 was utilized to validate the sequencing findings. TaqMan qPCR was performed for 29 genes (Additional file 1). qPCR reactions were run on an ABI 7900HT Real-Time PCR System and data analyzed using the SDS2.3 and DataAssist v2.0 software from Applied Biosystems.

Functional analysis

Networks and functional analyses were generated through the use of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity systems, [26]) and the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID) [27,28] bioinformatics resources.

Ki-67 immunohistochemistry

Tissue cores were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin within 5 minutes of acquisition and delivered to IU Health Pathology for routine paraffin embedding. Sections 3 to 5 microns thick were deparaffinized and hydrated to running water. Antigen retrieval was carried out in the pretreatment module (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) using low pH target retrieval (DAKO). All staining was performed on the AutoStainer Plus (DAKO). Sections were incubated with 3% H2O2 for 5 minutes and subsequently exposed to the primary antibody, Ki-67 (Mib-1, DAKO), for 20 minutes. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (EnVision™/HRP) was placed on the tissue for 20 minutes followed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) + chromogen for 10 minutes. Sections were counterstained with EnVision™ Flex Hematoxylin (DAKO). The pathologist (SB) was blinded as to the phase of the menstrual cycle or to the use of hormonal contraception (HC). Each section was classified from grade 1 to 4 where 1 is the lowest number of cells stained/slide and 4 is highest number of cells stained/slide.

Results

Gene expression differences between the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle

Some 255 genes representing 1.4% of all genes were deemed to have statistically significant differential expression between the two phases of the menstrual cycle (Table S4 in Additional file 2). A total of 221 of the genes have higher expression during the luteal phase.

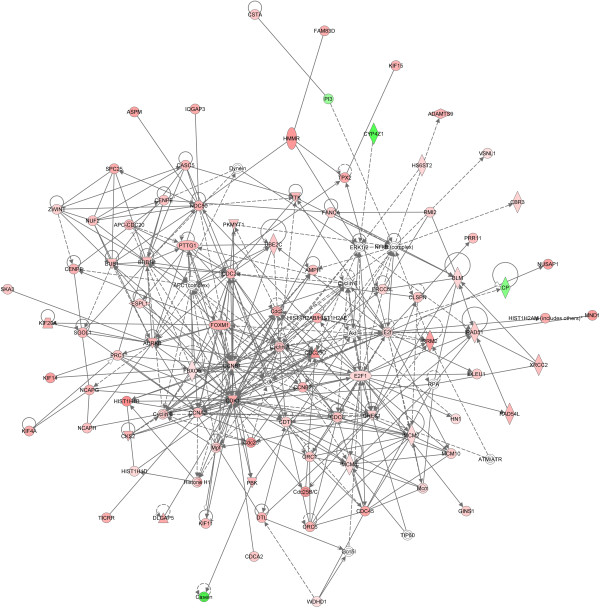

The genes with significant differential expression were analyzed using IPA. The molecular and cellular functions enriched in the gene list are provided in Table 2. These functions occur during the luteal phase. The top three networks as determined by IPA were merged and are presented in Figure 1. A total of 151 of the 255 genes are periodically expressed in the cell cycle as determined by comparison to lists generated in HeLa cells [29], foreskin fibroblasts [30], immortalized keratinocytes [31] and osteosarcoma [32] cell lines. Genes are displayed by the cell cycle phase in which they are expressed as well as by Gene Ontology (GO) biologic process terms in Table 3. GO biologic processes were ranked by statistical significance by DAVID; the top 30 are listed in Table S5 in Additional file 2.

Table 2.

Biologic functions in the luteal phase

| Function | P value |

|---|---|

| Cell cycle |

1.36E-28-1.22E-02 |

| Cellular organization and assembly |

1.36E-28-1.22E-02 |

| DNA replication, recombination and repair | 1.36E-28-1.22E-02 |

Top biologic functions of differentially expressed genes as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Figure 1.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis networks. The three most significant networks as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis were merged. The top functions represented in this figure are cell cycle; cellular assembly and organization; DNA replication, recombination, and repair.

Table 3.

Cell cycle phase and function

| G1/S | S | G2 | G2/M | M/G1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA replication initiation |

CDC45L |

|

|

|

MCM10 |

| CDC6 | |||||

| MCM2 | |||||

| MCM4 | |||||

| ORC1 | |||||

| ORC6 | |||||

| CDT1 | |||||

| Nucleotide metabolism |

|

|

|

DTYMK |

|

| RRM2 | |||||

| DNA replication and repair |

BRIP1 |

TYMS |

TOP2A |

FANCA |

|

| BLM |

RAD54L |

||||

| DNA2 |

NEIL3 |

||||

| RAD51 |

PTTG1 |

||||

| EXO1 |

POLQ |

||||

| POLE2 |

TRIP13 |

||||

| PCNA |

KIAA0101 |

||||

| UNG | |||||

| BRCA1 | |||||

| GINS2 | |||||

| DTL | |||||

| Chromatin assembly and disassembly |

HELLS |

HIST1H1B |

HJURP |

ASF1B |

|

| EZH2 |

HIST1H1D |

||||

| |

HIST1H2AB |

||||

| HIST1H2AH, HIST1H2AK, HIST1H2AM, HIST1H2AG, | |||||

| HIST1H2AL | |||||

| HIST1H2AJ | |||||

| HIST1H2BH | |||||

| HIST1H2BF, HIST1H2BE | |||||

| HIST1H2BL | |||||

| HIST1H2BM | |||||

| HIST1H2BN | |||||

| HIST1H2BO | |||||

| HIST1H2AD, HIST1H3C, HIST1H3F, HIST1H3G, HIST1H3B, HIST1H3H, HIST1H3J, HIST1H3A, HIST1H3D | |||||

| HIST1H4L, HIST1H4F, HIST1H4A | |||||

| Cell cycle regulation-interphase |

CLSPN |

|

|

CCNA2 |

|

| E2F1 |

CKS2 |

||||

| CHEK1 |

MKI67 |

||||

| Cell cycle regulation-mitosis |

FBXO5 |

|

|

FOXM1 |

CCNB1 |

| CCNB2 |

|

||||

| CDC20 | |||||

| CDC25C | |||||

| CIT | |||||

| MELK | |||||

| PKMYT1 |

|

||||

| UBE2C | |||||

| Microtubules and spindle formation |

|

|

|

KIF11 |

KIF18A |

| KIF14 |

KIF4A |

||||

| KIF15 | |||||

| KIF23 | |||||

| KIF2C | |||||

| SPAG5 | |||||

| TPX2 | |||||

| Spindle regulation |

|

|

|

BUB1B |

ASPM |

| BUB1 | |||||

| AURKB | |||||

| PLK4 | |||||

| PRC1 | |||||

| TTK | |||||

| Chromosome segregation |

NDC80 |

ZWINT |

NUF2 |

BIRC5 |

ESPL1 |

| SPC25 |

NCAPG |

CENPE |

CENPF |

||

| DSCC1 |

NCAPH |

DLGAP5 |

|

||

| SGOL1 |

KIFC1 |

||||

| CASC5 |

NUSAP1 |

||||

| Cytoskeleton |

AMPH |

|

|

CKAP2L |

|

| Nuclear membrane |

|

|

|

|

LAMB1 |

| Transcription |

ATAD2 |

|

|

MLF1IP |

|

| CDCA7 | |||||

| ZNF367 | |||||

| Nuclear division |

|

|

CDCA2 |

ANLN |

|

| FAM83D |

CDC20 |

||||

| CDCA3 | |||||

| GTPase activator activity |

|

|

|

DEPDC1 |

|

| DEPDC1B | |||||

| ARHGAP-11A | |||||

| IQGAP3 | |||||

| Cytokinesis |

|

|

|

PBK |

RACGAP-1 |

| ECT2 | |||||

| KPNA2 | |||||

| Membrane transport |

|

ABCC2 |

|

|

|

| Metabolic process | HMMR |

CBR3 |

|||

| HSPH1 |

ELOVL6 | ||||

| SRD5A1 |

Differentially expressed genes were allocated to a phase of the cell cycle by referring to phase allocations for HeLa cells [29], foreskin fibroblasts [30], immortalized keratinocytes [31] and osteosarcoma cells [32]. Functions were assigned by referring to Bar-Joseph et al.[30], the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Table modeled after Table S3 in Additional file 2 in reference [30].

A closer look at several of these genes and the processes they are involved in as well as non-cell cycle-controlled genes follows.

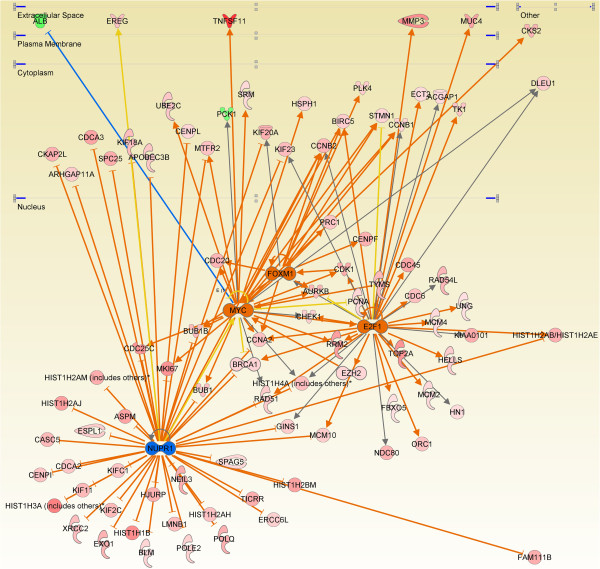

Luteal phase genes

Two of the major cellular events occurring during the cell cycle are DNA replication and mitosis. These events must occur at a specific time within the cycle and be successfully completed before progression to the next phase. Transcription of the genes that control or execute these functions is initiated by transcription factors. Both E2F1 and FOXM1 have higher expression during the luteal phase. Upstream analysis by IPA (Table S6 in Additional file 2) predicts E2F1 and MYC, and FOXM1 (Table S7 in Additional file 2) are activating gene transcription during the luteal phase while NUPR1 is the most significantly inhibited releasing its suppression of transcription (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Transcription factor targets. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis upstream analysis was employed to determine the transcription factor (TF) pathways activated and inhibited during the luteal phase. This figure displays the E2F1, MYC, FOXM1 And NUPR1 targets whose expression changes during the luteal phase. Genes with increased expression in the luteal phase are indicted in red, those decreased in green. Orange TFs are activated and blue are inhibited. Line color indicates the following: orange: activation, blue: inhibition, yellow: findings inconsistent with the state of the downstream molecule, and grey: an effect not predicted.

DNA replication

Initiation of DNA replication at the replication origins

There are four phases that occur during the initiation of DNA synthesis: recognition of the replication origins, assembly of the pre-replication complexes (pre-RC), activation of the DNA helicase(s) and loading of the replicative enzymes [33]. DNA becomes licensed for replication during late mitosis or the early G1 phase by the formation of pre-RC on replication origins [34]. Origins of replication are bound by origin replication complex (ORC)1-6 proteins and these form the platform for the loading of the minichromosome maintenance (MCM) proteins by CDC6 and CDT 1 to form the pre-RC. The expression of ORC1, ORC6, CDC6, CDT1, MCM2, and MCM4 are increased during the luteal phase in the normal breast epithelium. The CMG complex consisting of the CDC45, MCM2-7 and the GINS proteins functions as a helicase. The expression of CDC45, MCM2 and 4 and GINS1 and 2 was observed to be increased during the luteal phase. With regard to the final step, the replicative enzymes, PCNA and POLE were increased in the luteal phase.

DNA damage

BRCA1, RAD51, RAD54L, CHEK1, XRCC2, HJURP, RMI2 and BLM are involved in homologous recombination [35], and the expression of all seven genes increases during the luteal phase. BRIP1, which interacts with the BRCT repeats of BRCA1 and is important to BRCA1 function, is also increased [36]. HMMR and MAD1L1 are both more highly expressed in the luteal phase. The proteins encoded by these genes associate in protein complexes with BRCA 1 and BRCA2 [37]. Base excision repair (BER) is represented by NEIL3[38], POLE2, UNG and PCNA. Fanconi anemia proteins are required for the repair of DNA cross-links [39]; FANCA expression is higher in the luteal phase. EXO1, the protein product of which is involved in DNA end resection and double-strand break repair, is increased during the luteal phase. DNA polymerase POLQ is more highly expressed during the luteal phase. This polymerase has the unique ability to bypass blocking lesions such as abasic sites and thymine glycols [38]. It is also able to extend unpaired termini [38].

Mitosis

The terms associated with the gene group with the highest enrichment score as determined by the gene functional classification tool in DAVID are M phase and mitosis. Forty-seven (21%) of the 221 genes with increased levels of expression during the luteal phase are involved in mitosis. A list of the genes involved in mitosis and increased in expression during the luteal phase is provided in Table S8 in Additional file 2. While not intended to be exhaustive, a survey of some of the functions during mitosis of the encoded gene are also provided in the table. Recent studies employing small interfering RNA (siRNA) and proteomic strategies have enabled the kinetochore proteins to be assigned to complexes with specific functions at the kinetochore [33-35]. Using this information it was possible to assign three genes increased during the luteal phase to the Ndc80 complex, two to the chromosome passenger complex (CPC), three to the constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN) and three to the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC). Nine kinesin motor protein genes also demonstrate increased expression.

Paracrine signaling

RANKL, WNT4 and EREG are all overrepresented during the luteal phase.

Hormones

GHR expression is increased during the luteal phase as are PTHLH and SRD5A1. SRD5A1 catalyzes the conversion of progesterone to the 5alpha-pregnanes, which are mitogens in the normal human breast [40]. It also converts testosterone to dihydroxytestosterone, which has distinctly anti-proliferative effects in the breast [41]. PTHLH promotes nipple formation and mammary duct branching during embryogenesis and has an important role in calcium transport in the lactating gland [42]. ESRRB encodes the estrogen-related receptor beta, an orphan nuclear receptor. This protein would seem to have disparate functions in that it is a key regulator of embryonic stem cell self-renewal in the mouse [43,44], however, its ortholog functions as a metabolic switch during development in the Drosophila[45].

Matrix metalloproteinases

MMP3 and ADAMTS9 are both higher in expression during the luteal phase. MMP3 plays a role in mammary gland branching morphogenesis [46,47].

Follicular phase genes

Thirty-four of the 251 differentially expressed genes show increased expression during the follicular phase. They can be assigned to categories based on function. Two are associated with fat droplets in milk: BYN1A1, MUC15. Three genes encode ion channels or transporters: GLRA3, NHEDC1, and KCNT2. Two genes are associated with a fully differentiated phenotype: HOXB6, TFCP2L1. A number of genes encode proteins with metabolic functions: CYP4Z1, CYP4X1, HMGCS2, and PCK1. PCK1 expression in the normal mammary gland results in gluconeogenesis and glycerolneogenesis [48]. PCK1-dependent glyceroneogenesis may contribute to the formation of milk triglycerides in epithelial cells during lactation [49]. PI3 is a serine protease inhibitor that has antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as fungal pathogens on epithelial surfaces [50].

Effect of hormonal contraception

CCDC144A was the only gene differentially expressed between the hormone contraceptive group and luteal phase group (Table S9 in Additional file 2). This gene encodes a protein of unknown function.

qPCR validation

Twenty-nine genes were selected for qPCR validation; the expression of 27 of the 29 was validated (Table 4).

Table 4.

Validation cohort

| Gene | logFC (RNA-Seq) | P value | Fold change (qPCR biological validation) | Validation status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AURKB |

1.694476904 |

1.10E-05 |

8.56 |

V |

|

BRCA1 |

1.042815222 |

4.95E-06 |

2.39 |

V |

|

BUB1 |

1.526455024 |

2.82E-07 |

2.95 |

V |

|

BUB1B |

1.602146974 |

8.86E-07 |

3.87 |

V |

|

CCNB1 |

1.055253675 |

9.55E-05 |

2.73 |

V |

|

CDC25C |

2.501848634 |

4.13E-11 |

6.1 |

V |

|

CDC6 |

1.49654134 |

2.33E-08 |

3.76 |

V |

|

CDK1 |

1.965582801 |

6.77E-12 |

6.33 |

V |

|

CENPE |

1.462857192 |

1.39E-06 |

3.05 |

V |

|

CLSPN |

1.383625655 |

6.57E-06 |

6.07 |

V |

|

E2F1 |

0.996887203 |

0.000372 |

3.06 |

V |

|

ECT2 |

0.872573718 |

0.000152 |

1.89 |

V |

|

ERCC6L |

1.102811499 |

8.88E-05 |

0.79 |

N |

|

FANCA |

1.224811173 |

1.63E-06 |

4.33 |

V |

|

FOXM1 |

1.92032584 |

2.17E-07 |

8.43 |

V |

|

HIST1H2AH |

1.485622497 |

0.000196 |

0.99 |

N |

|

HIST1H2AJ |

2.284502132 |

8.84E-06 |

2.96 |

V |

|

HIST1H2AM |

1.530373984 |

0.000151 |

1.98 |

V |

|

HIST1H2BH |

1.563333889 |

3.04E-07 |

1.32 |

V |

|

HIST1H3B |

2.979880506 |

6.94E-16 |

1.43 |

V |

|

KIF20A |

1.876073752 |

5.20E-08 |

8.09 |

V |

|

KIF23 |

1.604227334 |

1.98E-09 |

3.22 |

V |

|

NCAPG |

1.888216879 |

2.37E-10 |

7.2 |

V |

|

PCNA |

0.939041116 |

1.44E-05 |

2.09 |

V |

|

RAD51 |

1.255859843 |

1.79E-05 |

4.75 |

V |

|

RRM2 |

2.285244825 |

5.90E-09 |

1.3 |

V |

|

TK1 |

1.410412144 |

2.83E-05 |

5.67 |

V |

|

TPX2 |

2.025558609 |

1.21E-10 |

5.49 |

V |

| TYMS | 1.667388087 | 2.36E-09 | 5.64 | V |

TaqMan qPCR was performed for 29 genes representing the DNA replication and mitosis clusters. Twenty-seven of 29 were validated. RNA-Seq, whole transcriptome sequencing; V, validated; N, not validated.

Ki-67 immunohistochemistry

Ki-67 immunohistochemistry shows strong (4) staining in the tissue sections from donors in the luteal phase or those using HC (Table S10 in Additional file 2). All sections demonstrating weak staining were from donors in the follicular phase. Intermediate staining (2 to 3) was mixed among both phases and donors using HC.

Discussion

The functioning ovaries produce relatively large amounts of estradiol and progesterone in a cyclical pattern approximately every 28 days. The mid-cycle estrogen peak concentration can be 10 times that in the early follicular phase and progesterone serum concentrations are 10-fold higher in the luteal phase than follicular phase. In this study, next-generation RNA sequencing has been utilized to determine how these changes in serum steroid hormone concentrations effect breast epithelial gene expression. Gene expression in the breast epithelium of women using HC has also been assayed to determine the effects of these exogenous hormones. A total of 255 genes were differentially expressed when comparing the two phases of the menstrual cycle, of these 221 (87%) were more highly expressed during the luteal phase.

The specific changes in gene expression observed in the human breast epithelium as a function of the menstrual phase confirm and expand upon the results of Graham et al. who used both breast organoids and cell lines to test the effects of progesterone treatment [51]. The specific functions identified by those investigators were DNA replication, the G2/M checkpoint and kinetochore function, and the G1/S transition. A large percentage of the genes expressed during the luteal phase are cell cycle regulated and they can be broadly placed into one of two clusters: DNA replication and mitosis. The DNA replication cluster includes genes involved in DNA synthesis, including components of the pre-RC, nucleotide biosynthesis, DNA replication, DNA packaging, S phase regulation and DNA repair. The G1/S phase transcription phase regulator E2F1 binds to the promoter and thereby initiates the transcription of most genes in this cluster [32]. E2F1 transcription, in turn, is stimulated by the increased progesterone concentration during the luteal phase. This may be the direct result of the binding of the E2F1 promoter by the progesterone receptor (PR) [52]. Progesterone may also act by increasing the expression of MYC [53], which subsequently facilitates, directly and indirectly, the expression of E2F1 [54,55]. The mitosis cluster contains genes involved in the processes of chromosome segregation, spindle organization, protein-DNA complex assembly, regulation of mitosis and cytokinesis. The promoters of most of these genes are bound by FOXM1. FOXM1 has a pivotal role in the regulation of cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. It exerts control on the G1/S transition, S-phase progression, DNA replication, centriole duplication, sister chromatid cohesion, G2/M transition, mitosis, DNA damage response and DNA repair [56]. Increased FOXM1 expression during the luteal phase is likely an indirect effect of the change in the concentration of ovarian steroids. Grant et al. state that E2F1 does not bind to the promoter of FOXM1[32], however, chromatin immunoprecipitation reveals binding of E2F1 to the proximal promoter of FOXM1 in MCF-7 cells [57]. FOXM1 has been shown also to be regulated by TNFSF11 (RANKL) [58] and 14-3-3ζ [59]. Additional data reported by Bergamaschi, Katzenellenbogen and colleagues is also of interest: just over one-third of the 29 genes they identified to be significantly associated with 14-3-3ζ overexpression, tamoxifen resistance, FOXM1 expression, and the luminal B and a minority of basal subtypes of breast cancer have higher expression in the luteal phase [59]. The level of FOXM1 expression has also been shown to be correlated with the effectiveness of a number of other breast cancer therapies including herceptin [60], gefitinib [61], lapatinib [62], paclitaxel [60], and cis-platinum [63]. The downregulation of NUPR1, although not observed at the transcript level, is inferred by IPA upstream analysis. NUPR1, also known as p8 and COM1, is a chromatin-binding protein, which inhibits cell proliferation [64]. Reducing the expression of this protein accelerates the kinetics of G1 progression to S phase [64]. Clinical breast cancer studies have demonstrated significantly decreased p8 nuclear staining in breast cancer cells [65].

Only a small percentage of normal mammary cells are estrogen receptor (ER) and/or PR+ and mammary stem cells lack these receptors. Nevertheless, progesterone elicits significant changes in gene expression, which must be mediated by other factors. Brisken and colleagues have demonstrated that progesterone’s effect on mammary gland morphogenesis is mediated by WNT4 [66,67] and proliferation by RANK ligand [68], both acting by a paracrine mechanism. RANK ligand and WNT4 have been identified as paracrine effectors of progesterone-induced mammary stem cell expansion [18,19]. The data presented in this paper reveals increased expression of these genes during the luteal phase, likely a consequence of the increased progesterone concentration during this phase. Amphiregulin (AREG) has also been shown to be a downstream target of progesterone in the mouse mammary epithelium and its actions thought to be paracrine [69]. The expression of AREG was not increased during the luteal phase, however, another member of the epidermal growth factor family, epiregulin (EREG), was increased. EREG is an autocrine growth factor for normal human keratinocytes [70]. It can also induce the resumption of meiosis [71].

Asselin-Labat and colleagues utilized fluorescent-activated cell sorting to divide mouse mammary cells into luminal (CD29loCD24+) and mammary stem cell-enriched (CD29hiCD24+) subfractions [18]. They then compared gene expression in these two subfractions as a function of ovariectomy. It is interesting to note that 54 (21%) of the genes differentially expressed as a function of the menstrual cycle are decreased as a consequence of ovarian hormone deprivation (Table S11 in Additional file 2). The reprise of these genes in the Asslin-Labat study is confirmatory evidence that the changes in the expression of these genes are indeed a consequence of the elaboration of ovarian hormones.

ESSRB expression was increased during the luteal phase. In Drosophila the activated single estrogen-related receptor ortholog causes a metabolic switch to a form of aerobic glycolysis that is reminiscent of the Warburg effect. It is tempting to speculate that a metabolic switch, such as occurs in Drosophila, provides the building blocks for the synthesis of amino acids, lipid and nucleotides required for the proliferation taking place during the luteal phase.

Many of the cell cycle genes identified with increased expression during the luteal phase have been shown to be overexpressed in breast cancer. This begs the question as to whether they have a role in oncogenesis or if the increased expression is simply a reflection of proliferating tumor cells. An increased number of ovulatory menstrual cycles and the prolonged use of progestin-containing hormone replacement therapy are both associated with an increased risk of the development of breast cancer [72,73]. Pike and colleagues hypothesized almost two decades ago that many of the epidemiologic observations regarding the relation of ovarian/steroidal hormones to breast cancer risk could be explained by an increased mitotic rate [14]. An increased mitotic rate may be increased mitotic activity above some baseline rate or it may be the division of a subset of cells that would ordinarily not be dividing, that is, stem cells. Joshi and colleagues clearly demonstrated that progesterone is driving the proliferation of murine mammary breast stem cells [19], and stem cells are likely to have accumulated a wealth of DNA lesions during their quiescence. Pike’s increased mitotic rate is likely a surrogate for cells re-entering and traversing the cell cycle. There are numerous redundant systems functioning during the cell cycle to ensure the correct replication of DNA and segregation of chromosomes; and, in those instances where repair cannot be affected, to eliminate those cells. Nevertheless, some of the products of the genes identified to have increased expression in the luteal phase genes have tight tolerances meaning there is a small margin of error. For example, both depletion and overexpression of KIAA0101 result in supernumerary centrosomes. The cell cycle is regulated by transcription, phosphorylation and ubiquitination events that must occur at a precise time within the cell cycle. Loss of this temporal control, such as the inappropriate expression of the progesterone-driven genes identified in the luteal phase, can result in genomic instability [74].

Oral contraceptives have been shown to leave the mitotic activity in the breast effectively unchanged when compared to a normal menstrual cycle and therefore have no chemopreventative effect [75]. These epidemiologic observations are substantiated by the findings of this sequencing study: there was only a single gene significantly differentially expressed when comparing the breast epithelium of women taking HC to women in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. The breast epithelium of a woman taking HC experiences a continuous luteal phase during the weeks that the breasts are exposed to the exogenous hormones. These hormones drive mitosis, cell cycle progression and proliferation using the same genetic programs as with endogenous ovarian hormones.

Conclusions

Fundamental insights into the prevention of breast cancer are unlikely until we develop an understanding of the genetics and developmental biology of the normal mammary gland. The breast is one of the most complex genetic organs within the body. This is because DNA expression is under the control and influence of the hormonal milieu present in the circulation, which changes as a function of age; and for premenopausal women as a function of the menstrual cycle. We have taken advantage of a unique research resource: The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Cancer Center (KTB), a biorepository of normal, healthy breast tissue, to complete the first ever next-generation transcriptome sequencing of epithelial compartment of 20 normal human breast specimens. This work has produced an initial catalog of the differences in the expression of protein-coding genes as a function of the phase of the menstrual cycle. Gene expression in the breast epithelium was also compared between women using HC and those not. Gene expression increased in the luteal phase for the majority of the differentially expressed genes. The products of these genes regulate the cell cycle, mitosis, DNA licensing and replication, and the response to DNA damage including checkpoints and repair. Their expression is likely to have been a consequence of paracrine effectors of progesterone including RANKL, WNT4 and EREG. The breast epithelium of women using HC from the perspective of gene expression is that of a premenopausal woman during the luteal phase.

Abbreviations

BER: base excision repair; bp: base pair; CCAN: constitutive centromere-associated network; CORE: Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista; CPC: chromosome passenger complex; DAB: 3,3′-diaminobenzidine; DAVID: database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery; DE: differential expression; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; F: follicular; ER: estrogen receptor; FDR: false discovery rate; FFPE: formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded; GO: Gene Ontology; GEF: guanine-nucleotide exchange factor; HC: hormonal contraception; IBIS-1: International Breast Cancer Intervention Study-1; IPA: Ingenuity Pathway Analysis; IU: Indiana University; kMT: kinetochore-microtubules; KTB: The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Cancer Center; L: luteal; LCM: laser capture microdissection; LH: luteinizing hormone; MCM: minichromosome maintenance; MORE: Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation; mRNA: messenger RNA; MT: microtubule; NB: negative binomial; NCI: National Cancer Institute; NSABP-P1: The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, Breast Cancer Prevention Trial 1; ORC: origin recognition complex; pre-RC: pre-replicative complexes; PR: progesterone receptor; RNA: ribonucleic acid; RNA-Seq: whole transcriptome sequencing; SAC: spindle assembly checkpoint; siRNA: small interfering RNA; STAR: Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) Clinical Trial; TF: transcription factor.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SEC conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. SEC, TM, and AVS recruited normal volunteers and directed and maintained the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Cancer Center. IP, HAL, RJB, MRC, CAMS, DKD, TM, and BAH performed the laser capture microdissection and RNA extractions. DB assisted in data analysis. JG was responsible the experimental design of the next-generation sequencing; MH, JZ, and JG performed the next-generation sequencing. FZ, RWD, and YL performed the statistical analysis. MR participated in the microdissection of the breast tissue, study design and data analysis. RA participated in data analysis. SB reviewed histologic tissue sections and scored the immunohistochemistry. FZ, RWD, and SB drafted parts of the work; all authors participated in the revision of the various versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Experimental details of samples used, next-generation whole transcriptome sequencing, data analysis and qPCR validation.

Description of data: experimental details, serum estriol concentrations, additional demographics of specimen donors. Table S2. Description of data: total number of sequencing reads and the reads able to be mapped to the human genome (hg 19). Table S3. Description of data: raw read counts of the individual genes. Table S4. Description of the data: differential gene expression luteal versus follicular. Table S5. Description of the data: functional annotation chart. Table S6. Description of the data: list of transcription factors identified by IPA Upstream Analysis. Table S7. Description of the data: luteal phase genes previously identified as FOXM1 target genes. Table S8. Description of the data: functions of a subset (34/47) of the genes involved in mitosis or cytokinesis [76-101]. Table S9. Description of the data: differential gene expression luteal versus hormonal contraception. Table S10. Description of the data: Ki-67 immunohistochemistry. Table S11. Description of the data: comparison of RNA-Seq data with that of Asselin-Labat and colleagues. List of genes identified to have differential expression as a function of ovarian hormones by both this study and that of Asselin-Labat et al.[18].

Contributor Information

Ivanesa Pardo, Email: ivanesapardo@gmail.com.

Heather A Lillemoe, Email: heather.a.lillemoe@gmail.com.

Rachel J Blosser, Email: rblosser@iupui.edu.

MiRan Choi, Email: mi.choi@northwestern.edu.

Candice A M Sauder, Email: marcumc@iupui.edu.

Diane K Doxey, Email: kardox5@aol.com.

Theresa Mathieson, Email: tmathies@iupui.edu.

Bradley A Hancock, Email: hancockb@iupui.edu.

Dadrie Baptiste, Email: dbaptist@iupui.edu.

Rutuja Atale, Email: ruatale@umail.iu.edu.

Matthew Hickenbotham, Email: matthew.hickenbotham@lifetech.com.

Jin Zhu, Email: jin.1.zhu@monsanto.com.

Jarret Glasscock, Email: jarret_glasscock@cofactorgenomics.com.

Anna Maria V Storniolo, Email: astornio@iu.edu.

Faye Zheng, Email: zheng64@purdue.edu.

RW Doerge, Email: doerge@purdue.edu.

Yunlong Liu, Email: yunliu@iupui.edu.

Sunil Badve, Email: sbadve@iupui.edu.

Milan Radovich, Email: mradovic@iupui.edu.

Susan E Clare, Email: susan.clare@northwestern.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Robert J. Goulet, Jr., Valerie P. Jackson, Erika L. Rager, Patricia R. Kennedy, Monet Williams-Bowling, Barbara Savader, Stephen M. Westphal, Robert E. Pennington, Katherine H. Walker, Hadley E. Ritter, Richard C. Berg, Jr., and Roger Bangs for their donation of their time and technical expertise for the purpose of obtaining the tissue cores. Mark Mooney, James Elliott, and Ryan Richt engaged with us in discussions of next-generation sequencing and data analysis. We also thank Dr. Mayandi Sivaguru for assistance with laser capture microdissection. Dr. Marguerite Shepard’s assistance in verifying phase of the menstrual cycle based on serum hormone concentrations and insights regarding the donors who were using contraception were invaluable. Drs. George W. Sledge, Jr. and Eric A. Wiebke were unstinting in their support of the KTB. The authors thank the staff of the KTB; and the thousands of donors and hundreds of volunteers who have selflessly given of themselves to enable the success of the KTB. This work was funded by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure (SEC, AVS, TM), The Breast Cancer Research Foundation (SEC, AVS, MC), the Catherine Peachey Fund (MR, SEC, AVS), the Department of Surgery Indiana University School of Medicine (IP, HAL, RJB, CAMS), and the Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine (BAH). MR was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the NIH, NRSA 1 T32 CA 111198 Cancer Biology Training Program. Publication costs were defrayed by donations received at the Solheim Pink Bow Luncheon in Lake Geneva, WI.

References

- Charting the Course: Priorities for Breast Cancer. Research Report of the Breast Cancer Progress Review Group. [ http://planning.cancer.gov/library/1998breastcancer.pdf]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, Bevers TB, Kavanah MT, Atkins JN, Margolese RG, Runowicz CD, James JM, Ford LG, Wolmark N. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: current status of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, Daly M, Wieand S, Tan-Chiu E, Ford L, Wolmark N. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Forbes J, Edwards R, Baum M, Cawthorn S, Coates A, Hamed A, Howell A, Powles T. First results from the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS-I): a randomised prevention trial. Lancet. 2002;360:817–824. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09962-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzick J, Forbes JF, Sestak I, Cawthorn S, Hamed H, Holli K, Howell A. Long-term results of tamoxifen prophylaxis for breast cancer–96-month follow-up of the randomized IBIS-I trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:272–282. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, Bevers TB, Fehrenbacher L, Pajon ER Jr, Wade JL 3rd, Robidoux A, Margolese RG, James J, Lippman SM, Runowicz CD, Ganz PA, Reis SE, McCaskill-Stevens W, Ford LG, Jordan VC, Wolmark N. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, Bevers TB, Fehrenbacher L, Pajon ER, Wade JL 3rd, Robidoux A, Margolese RG, James J, Runowicz CD, Ganz PA, Reis SE, McCaskill-Stevens W, Ford LG, Jordan VC, Wolmark N. Update of the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project study of tamoxifen and raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial: preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Ales-Martinez JE, Cheung AM, Chlebowski RT, Wactawski-Wende J, McTiernan A, Robbins J, Johnson KC, Martin LW, Winquist E, Sarto GE, Garber JE, Fabian CJ, Pujol P, Maunsell E, Farmer P, Gelmon KA, Tu D, Richardson H. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381–2391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman ME, Figueroa JD, Henry JE, Clare SE, Rufenbarger C, Storniolo AM. The Susan G. Komen for the Cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Cancer Center: a unique resource for defining the “molecular histology” of the breast. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:528–535. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange R, Westerlind KC, Ziemiecki A, Andres AC. Proliferation and apoptosis in mammary epithelium during the rat oestrous cycle. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;190:137–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedin P, Mitrenga T, Kaeck M. Estrous cycle regulation of mammary epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and death in the Sprague–Dawley rat: a model for investigating the role of estrous cycling in mammary carcinogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5:211–225. doi: 10.1023/A:1026447506666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel PM, Georgiade NG, Fetter BF, Vogel FS, McCarty KS Jr. The correlation of histologic changes in the human breast with the menstrual cycle. Am J Pathol. 1981;104:23–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:17–35. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TJ, Ferguson DJ, Raab GM. Cell turnover in the “resting” human breast: influence of parity, contraceptive pill, age and laterality. Br J Cancer. 1982;46:376–382. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DJ, Anderson TJ. Morphological evaluation of cell turnover in relation to the menstrual cycle in the “resting” human breast. Br J Cancer. 1981;44:177–181. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete MA, Maier CM, Falzoni R, Quadros LG, Lima GR, Baracat EC, Nazario AC. Assessment of the proliferative, apoptotic and cellular renovation indices of the human mammary epithelium during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2005;7:R306–R313. doi: 10.1186/bcr994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F, Sheridan JM, Pal B, Wu D, Simpson ER, Yasuda H, Smyth GK, Martin TJ, Lindeman GJ, Visvader JE. Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature. 2010;465:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature09027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi PA, Jackson HW, Beristain AG, Di Grappa MA, Mote PA, Clarke CL, Stingl J, Waterhouse PD, Khokha R. Progesterone induces adult mammary stem cell expansion. Nature. 2010;465:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature09091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PA, Hrushesky WJ. Sex cycle modulates cancer growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-8269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso A, Serio G, Fanelli M, Mangia A, Cellamare G, Schittulli F. Predictability of monthly and yearly rhythms of breast cancer features. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;67:41–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1010658804640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coradini D, Veneroni S, Pellizzaro C, Daidone MG. Fluctuation of intratumor biological variables as a function of menstrual timing of surgery for breast cancer in premenopausal patients. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:962–964. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, Hao L, Kiang A, Paschall J, Phan L, Popova N, Pretel S, Ziyabari L, Lee M, Shao Y, Wang ZY, Sirotkin K, Ward M, Kholodov M, Zbicz K, Beck J, Kimelman M, Shevelev S, Preuss D, Yaschenko E, Graeff A, Ostell J, Sherry ST. The NCBI dbGaP database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dgGaP) [ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=gap]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. [ http://www.ingenuity.com]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, Murray JI, Ball CA, Alexander KE, Matese JC, Perou CM, Hurt MM, Brown PO, Botstein D. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Joseph Z, Siegfried Z, Brandeis M, Brors B, Lu Y, Eils R, Dynlacht BD, Simon I. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the human cell cycle identifies genes differentially regulated in normal and cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:955–960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704723105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Diaz J, Hegre SA, Anderssen E, Aas PA, Mjelle R, Gilfillan GD, Lyle R, Drablos F, Krokan HE, Saetrom P. Transcription profiling during the cell cycle shows that a subset of Polycomb-targeted genes is upregulated during DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:2846–2856. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant GD, Brooks L 3rd, Zhang X, Mahoney JM, Martyanov V, Wood TA, Sherlock G, Cheng C, Whitfield ML. Identification of cell cycle-regulated genes periodically expressed in U2OS cells and their regulation by FOXM1 and E2F transcription factors. Mole Biol Cell. 2013;24:3634–3650. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-05-0264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JA, Aves SJ. Initiation of DNA replication: functional and evolutionary aspects. Ann Bot. 2011;107:1119–1126. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HT, Tsang YH, Marxer M, Poon RY. Cyclin A2-cyclin-dependent kinase 2 cooperates with the PLK1-SCFbeta-TrCP1-EMI1-anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome axis to promote genome reduplication in the absence of mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6500–6514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00669-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen CS, Hansen LT, Dziegielewski J, Syljuasen RG, Lundin C, Bartek J, Helleday T. The cell-cycle checkpoint kinase Chk1 is required for mammalian homologous recombination repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:195–201. doi: 10.1038/ncb1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor SB, Bell DW, Ganesan S, Kass EM, Drapkin R, Grossman S, Wahrer DC, Sgroi DC, Lane WS, Haber DA, Livingston DM. BACH1, a novel helicase-like protein, interacts directly with BRCA1 and contributes to its DNA repair function. Cell. 2001;105:149–160. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujana MA, Han JD, Starita LM, Stevens KN, Tewari M, Ahn JS, Rennert G, Moreno V, Kirchhoff T, Gold B, Assmann V, Elshamy WM, Rual JF, Levine D, Rozek LS, Gelman RS, Gunsalus KC, Greenberg RA, Sobhian B, Bertin N, Venkatesan K, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Sole X, Hernandez P, Lazaro C, Nathanson KL, Weber BL, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Offit K. et al. Network modeling links breast cancer susceptibility and centrosome dysfunction. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1338–1349. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg M, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Johansson E. Promiscuous DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase θ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2611–2622. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe N, Turner NC, Lord CJ, Kluzek K, Bialkowska A, Swift S, Giavara S, O’Connor MJ, Tutt AN, Zdzienicka MZ, Smith GC, Ashworth A. Deficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8109–8115. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe JP, Muzia D, Hu J, Szwajcer D, Hill SA, Seachrist JL. The 4-pregnene and 5alpha-pregnane progesterone metabolites formed in nontumorous and tumorous breast tissue have opposite effects on breast cell proliferation and adhesion. Cancer Res. 2000;60:936–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigeliene N, Elo T, Linhala M, Hurme S, Erkkola R, Harkonen P. Androgens inhibit the stimulatory action of 17beta-estradiol on normal human breast tissue in explant cultures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1116–E1127. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Giner M, Noguera JL, Balcells I, Alves E, Varona L, Pena RN. Expression study on the porcine PTHLH gene and its relationship with sow teat number. J Anim Breed Genet. 2011;128:344–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0388.2011.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G, Sugimoto T, Diamanti E, Joshi A, Hannah R, Ohtsuka S, Gottgens B, Niwa H, Smith A. Esrrb is a pivotal target of the Gsk3/Tcf3 axis regulating embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festuccia N, Osorno R, Halbritter F, Karwacki-Neisius V, Navarro P, Colby D, Wong F, Yates A, Tomlinson SR, Chambers I. Esrrb is a direct Nanog target gene that can substitute for Nanog function in pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:477–490. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen JM, Baker KD, Lam G, Evans J, Thummel CS. The Drosophila estrogen-related receptor directs a metabolic switch that supports developmental growth. Cell Metab. 2011;13:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sympson CJ, Talhouk RS, Alexander CM, Chin JR, Clift SM, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Targeted expression of stromelysin-1 in mammary gland provides evidence for a role of proteinases in branching morphogenesis and the requirement for an intact basement membrane for tissue-specific gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:681–693. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simian M, Hirai Y, Navre M, Werb Z, Lochter A, Bissell MJ. The interplay of matrix metalloproteinases, morphogens and growth factors is necessary for branching of mammary epithelial cells. Development. 2001;128:3117–3131. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CW, Huang C, Bederman I, Yang J, Beidelschies M, Hatzoglou M, Puchowicz M, Croniger CM. Function of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in mammary gland epithelial cells. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1352–1362. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M012666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CW, Millward CA, DeSantis D, Pisano S, Machova J, Perales JC, Croniger CM. Reduced milk triglycerides in mice lacking phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in mammary gland adipocytes and white adipose tissue contribute to the development of insulin resistance in pups. J Nutr. 2009;139:2257–2265. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Shen Z, Fahey JV, Cu-Uvin S, Mayer K, Wira CR. Trappin-2/Elafin: a novel innate anti-human immunodeficiency virus-1 molecule of the human female reproductive tract. Immunology. 2010;129:207–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JD, Mote PA, Salagame U, van Dijk JH, Balleine RL, Huschtscha LI, Reddel RR, Clarke CL. DNA replication licensing and progenitor numbers are increased by progesterone in normal human breast. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3318–3326. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Roqueiro D, Huang L, Owen JK, Xie A, Navarro A, Monsivais D, Coon JS 5th, Kim JJ, Dai Y, Bulun SE. Genome-wide progesterone receptor binding: cell type-specific and shared mechanisms in T47D breast cancer cells and primary leiomyoma cells. PloS One. 2012;7:e29021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Zhou JL, Blankenship KA, Strobl JS, Edwards DP, Gentry RN. A sequence in the 5′ flanking region confers progestin responsiveness on the human c-myc gene. J Steroid Biochem Mole Biol. 1997;62:243–252. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(97)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JY, Ehmann GL, Giangrande PH, Nevins JR. A role for Myc in facilitating transcription activation by E2F1. Oncogene. 2008;27:4172–4179. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JV, Dong P, Nevins JR, Mathey-Prevot B, You L. Network calisthenics: control of E2F dynamics in cell cycle entry. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3086–3094. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.18.17350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierstra I. The transcription factor FOXM1 (Forkhead box M1): proliferation-specific expression, transcription factor function, target genes, mouse models, and normal biological roles. Adv Cancer Res. 2013;118:97–398. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407173-5.00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millour J, de Olano N, Horimoto Y, Monteiro LJ, Langer JK, Aligue R, Hajji N, Lam EW. ATM and p53 regulate FOXM1 expression via E2F in breast cancer epirubicin treatment and resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1046–1058. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellen D, Luong-Nguyen NH, Bongiovanni S, Grenet O, Wanke C, Susa M. Transcriptional program of mouse osteoclast differentiation governed by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor and the ligand for the receptor activator of NFkappa B. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21971–21982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamaschi A, Christensen BL, Katzenellenbogen BS. Reversal of endocrine resistance in breast cancer: interrelationships among 14-3-3zeta, FOXM1, and a gene signature associated with mitosis. BCR. 2011;13:R70. doi: 10.1186/bcr2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JR, Park HJ, Wang Z, Kiefer MM, Raychaudhuri P. FoxM1 mediates resistance to herceptin and paclitaxel. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5054–5063. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern UB, Francis RE, Peck B, Guest SK, Wang J, Myatt SS, Krol J, Kwok JM, Polychronis A, Coombes RC, Lam EW. Gefitinib (Iressa) represses FOXM1 expression via FOXO3a in breast cancer. Mole Cancer Ther. 2009;8:582–591. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis RE, Myatt SS, Krol J, Hartman J, Peck B, McGovern UB, Wang J, Guest SK, Filipovic A, Gojis O, Palmieri C, Peston D, Shousha S, Yu Q, Sicinski P, Coombes RC, Lam EW. FoxM1 is a downstream target and marker of HER2 overexpression in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:57–68. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok JM, Peck B, Monteiro LJ, Schwenen HD, Millour J, Coombes RC, Myatt SS, Lam EW. FOXM1 confers acquired cisplatin resistance in breast cancer cells. MCR. 2010;8:24–34. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan R, Cheedipudi S, Pasupuleti N, Saleh A, Pavlath GK, Dhawan J. The small chromatin-binding protein p8 coordinates the association of anti-proliferative and pro-myogenic proteins at the myogenin promoter. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3481–3491. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang WG, Watkins G, Douglas-Jones A, Mokbel K, Mansel RE, Fodstad O. Expression of Com-1/P8 in human breast cancer and its relevance to clinical outcome and ER status. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:730–737. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, Park S, Vass T, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW, Weinberg RA. A paracrine role for the epithelial progesterone receptor in mammary gland development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5076–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisken C, Heineman A, Chavarria T, Elenbaas B, Tan J, Dey SK, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Weinberg RA. Essential function of Wnt-4 in mammary gland development downstream of progesterone signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;14:650–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beleut M, Rajaram RD, Caikovski M, Ayyanan A, Germano D, Choi Y, Schneider P, Brisken C. Two distinct mechanisms underlie progesterone-induced proliferation in the mammary gland. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2989–2994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915148107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axlund SD, Sartorius CA. Progesterone regulation of stem and progenitor cells in normal and malignant breast. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;357:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata Y, Komurasaki T, Toyoda H, Hanakawa Y, Yamasaki K, Tokumaru S, Sayama K, Hashimoto K. Epiregulin, a novel member of the epidermal growth factor family, is an autocrine growth factor in normal human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5748–5753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi H, Cao X, Motola S, Popliker M, Conti M, Tsafriri A. Epidermal growth factor family members: endogenous mediators of the ovulatory response. Endocrinology. 2005;146:77–84. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland M, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Spiegelman D, Speizer F, Willett WC. Menstrual cycle characteristics and history of ovulatory infertility in relation to breast cancer risk in a large cohort of US women. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:636–643. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidorova JM, Breeden LL. Precocious G1/S transitions and genomic instability: the origin connection. Mutat Res. 2003;532:5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike MC, Spicer DV. Hormonal contraception and chemoprevention of female cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7:73–83. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0070073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman IM, Desai A. Molecular architecture of the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:33–46. doi: 10.1038/nrm2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, Midgley C, Bergh AM, Bell SM, Askham JM, Roberts E, Binns RK, Sharif SM, Bennett C, Glover DM, Woods CG, Morrison EE, Bond J. Human ASPM participates in spindle organisation, spindle orientation and cytokinesis. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labit H, Fujimitsu K, Bayin NS, Takaki T, Gannon J, Yamano H. Dephosphorylation of Cdc20 is required for its C-box-dependent activation of the APC/C. EMBO J. 2012;31:3351–3362. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Cell biology. A helix for the final cut. Science. 2011;331:1533–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1204208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai M, Camera P, Dema A, Bianchi F, Berto G, Scarpa E, Germena G, Di Cunto F. Citron kinase controls abscission through RhoA and anillin. Mole Biol Cell. 2011;22:3768–3778. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Zhang J, Ahmad S, Rozier L, Yu H, Deng H, Mao Y. Aurora B regulates formin mDia3 in achieving metaphase chromosome alignment. Dev Cell. 2011;20:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye F, Tan L, Yang Q, Xia Y, Deng LW, Murata-Hori M, Liou YC. HURP regulates chromosome congression by modulating kinesin Kif18A function. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1584–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su KC, Takaki T, Petronczki M. Targeting of the RhoGEF Ect2 to the equatorial membrane controls cleavage furrow formation during cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouzeau S, Cordelieres FP, Buhagiar-Labarchede G, Hurbain I, Onclercq-Delic R, Gemble S, Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Jaulin C, Amor-Gueret M. Bloom’s syndrome and PICH helicases cooperate with topoisomerase IIalpha in centromere disjunction before anaphase. PloS One. 2012;7:e33905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Kucej M, Fan HY, Yu H, Sun QY, Zou H. Separase is recruited to mitotic chromosomes to dissolve sister chromatid cohesion in a DNA-dependent manner. Cell. 2009;137:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Ohsumi K, Iwabuchi M, Kawamata T, Ono Y, Takahashi M. Kendrin is a novel substrate for separase involved in the licensing of centriole duplication. Curr Biol. 2012;22:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshe Y, Bar-On O, Ganoth D, Hershko A. Regulation of the action of early mitotic inhibitor 1 on the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome by cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16647–16657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kais Z, Barsky SH, Mathsyaraja H, Zha A, Ransburgh DJ, He G, Pilarski RT, Shapiro CL, Huang K, Parvin JD. KIAA0101 interacts with BRCA1 and regulates centrosome number. MCR. 2011;9:1091–1099. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada K, Susumu H, Sakuno T, Watanabe Y. Condensin association with histone H2A shapes mitotic chromosomes. Nature. 2011;474:477–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heale JT, Ball AR Jr, Schmiesing JA, Kim JS, Kong X, Zhou S, Hudson DF, Earnshaw WC, Yokomori K. Condensin I interacts with the PARP-1-XRCC1 complex and functions in DNA single-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2006;21:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]