Abstract

Epigenetic gene regulation has influence over a diverse range of cellular functions, including the maintenance of pluripotency, differentiation, and cellular identity, and is deregulated in many diseases, including cancer. Whereas the involvement of epigenetic dysregulation in cancer is well documented, much of the mechanistic detail involved in triggering these changes remains unclear. In the current age of genomics, the development of new sequencing technologies has seen an influx of genomic and epigenomic data and drastic improvements in both resolution and coverage. Studies in cancer cell lines and clinical samples using next-generation sequencing are rapidly delivering spectacular insights into the nature of the cancer genome and epigenome. Despite these improvements in technology, the timing and relationship between genetic and epigenetic changes that occur during the process of carcinogenesis are still unclear. In particular, what changes to the epigenome are playing a driving role during carcinogenesis and what influence the temporal nature of these changes has on cancer progression are not known. Understanding the early epigenetic changes driving breast cancer has the exciting potential to provide a novel set of therapeutic targets or early-disease biomarkers or both. Therefore, it is important to find novel systems that permit the study of initial epigenetic events that potentially occur during the first stages of breast cancer. Non-malignant human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) provide an exciting in vitro model of very early breast carcinogenesis. When grown in culture, HMECs are able to temporarily escape senescence and acquire a pre-malignant breast cancer-like phenotype (variant HMECs, or vHMECs). Cultured HMECs are composed mainly of cells from the basal breast epithelial layer. Therefore, vHMECs are considered to represent the basal-like subtype of breast cancer. The transition from HMECs to vHMECs in culture recapitulates the epigenomic phenomena that occur during the progression from normal breast to pre-malignancy. Therefore, the HMEC model system provides the unique opportunity to study the very earliest epigenomic aberrations occurring during breast carcinogenesis and can give insight into the sequence of epigenomic events that lead to breast malignancy. This review provides an overview of epigenomic research in breast cancer and discusses in detail the utility of the HMEC model system to discover early epigenomic changes involved in breast carcinogenesis.

Introduction

Epigenetics is defined as a heritable change in phenotype without a change to the underlying DNA sequence. Epigenetics plays a major role in the regulation of genomic structure, and through this can modulate gene expression. A length of up to two meters of DNA is contained within the nucleus of a single cell and, to ensure that the genome remains functional and accessible, is kept in a highly structured state. The DNA is coiled into 146-base pair (bp) loop structures termed nucleosomes that contain a protein octamer composed of two copies of each of the histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Post-translational modifications of the histone proteins or their substitution with histone variants alter the structure of chromatin, which then can become tightly packed and transcriptionally inactive, termed heterochromatin, or open and transcriptionally active, termed euchromatin [1,2]. Modifications occur primarily at the N-terminal tails of the histone proteins and include, but are not limited to, sumoylation, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, methylation, and acetylation. The best-studied modifications are histone methylation and acetylation, which have particular relevance to carcinogenesis. Tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3) is a repressive histone modification regulated by the polycomb group (PcG) family of proteins. The histone methyltransferase EZH2 (enhancer of Zeste homologue 2) is the catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), is commonly aberrantly expressed in cancer, and has been associated with aggressive disease [3]. Control of histone acetylation is carried out by histone de-acetylases (HDACs) and histone acetyltransferases. Inhibition of HDACs has been shown to induce differentiation in cancer [4] and shows promise as a potential epigenetic therapy for cancer treatment (reviewed briefly in [5]).

In addition to histone modifications, the transcriptional state of a gene can be modulated through the covalent modification of the DNA strand itself, namely by the addition of methyl groups to cytosine residues found in cytosine followed by guanosine dinucleotide pairs (CpG). CpG dinucleotides are statistically under-represented within the genome because of a relatively high mutational rate [6,7]. However, CpG dinucleotides are commonly distributed in high-density clusters - termed CpG islands - that are often associated with gene promoter regions [8,9]. Methylation at promoter CpG islands leads to transcriptional repression and is associated with silencing chromatin marks. Inversely, methylation of gene body CpGs is associated with increased expression and active chromatin marks [10,11]. Methylation of the DNA is performed predominantly by the core DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, which play specific roles in the control of DNA methylation [12]. DNMT1 is responsible for the maintenance of DNA methylation after DNA replication. DNMT1 methylates cytosines on the nascent DNA strand and has a preference for hemi-methylated CpG sites. DNMT3A and DNMT3B perform de novo methylation and methylate fully unmethylated CpG sites. DNMT3A also interacts with the gene body chromatin modification H3K36me3 and has been implicated as being responsible for gene body methylation [13]. The regulation of gene expression by DNA methylation has particularly prominent roles in cellular differentiation and development. It is well established that embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and fully differentiated cells display widely different genomic methylation patterns [14]. Increasing methylation of pluripotency genes pushes cells toward a more differentiated state, a process that has been well characterized in breast epithelium. ESCs and breast epithelial progenitor cells display similar DNA methylation profiles across differentiation- and pluripotency-associated genes (Figure 1) [15]. These genes become hypermethylated during differentiation and lineage commitment leading to the acquisition of cell type-specific gene expression profiles [15]. These cells also display cell type-specific chromatin modification profiles, particularly in polycomb-regulated H3K27me3 marked genes [16]. In summary, both histone modifications and DNA methylation have been implicated in a wide variety of biological processes such as differentiation, genomic stability, and carcinogenesis.

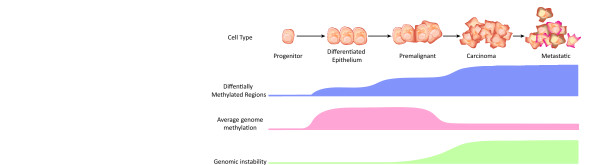

Figure 1.

Progression of the breast cell epigenome from progenitor to malignancy. During progression from progenitor cell to differentiated epithelium, cells exhibit an increasing level of DNA methylation as differentiation options are restricted. During cancer development, much of this genomic methylation is lost, with the exception of a small subset of genomic loci that exhibit DNA hypermethylation. Genomic hypomethylation is associated with increased genomic instability. The methylome of malignant lesions is remarkably similar between early lesions like ductal carcinoma in situ and later lesions like invasive ductal carcinoma.

Traditionally, the study of epigenetic modifications was performed at one or a few genomic loci at a time. Recent improvements in technology have led to high-throughput methods that allow the interrogation of many or all genes in the genome simultaneously. The combination of methylated DNA enrichment or chromatin immunoprecipitation with microarray or next-generation sequencing (ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq, respectively) has resulted in a drastic increase in the number of genomic loci that can be assessed for epigenetic information simultaneously. These technological improvements have seen a great increase in the amount of genome-wide epigenetic data being produced and have given insight into the role of epigenetics in development, embryogenesis, and complex disease. This is especially pronounced within the field of cancer research. This review aims to integrate some of the recent findings of epigenomic research in cancer and will cover in detail an under-used but powerful model of early breast carcinogenesis: human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) (reviewed in [17]).

Epigenetics and cancer

Epigenetic dysregulation has long been identified as contributing to the cancer phenotype. Global hypomethylation of the genome is considered a hallmark of cancer and was one of the earliest epigenetic traits identified in cancer cells [18]. Hypomethylation contributes to carcinogenesis in a variety of ways and, in mice, has been demonstrated to trigger the initiation of cancer [19]. DNA methylation is crucial to the inactivation of transposable genetic elements, and during carcinogenesis genomic demethylation can lead to the reactivation of these elements [20]. Unwanted transposition results in genomic instability, which deals further damage to the cancer genome and contributes to phenotype. Hypomethylation at the pericentric repeat regions also leads to an increase in instability without the activation of transposable elements. Instead, hypomethylation at the pericentric regions results in miss-segregation of chromosomes during cell division and leads to aneuploidy [21,22]. Increased genomic instability results in a higher instance of genomic rearrangements and leads to the formation of gene fusions and aberrant gene regulation. Additionally, induced hypomethylation of the genome of ESCs can block the capacity for differentiation [23], implicating this process in the loss of differentiation and increased capacity for self-renewal witnessed in cancer.

Hypermethylation of gene promoters adds to the cancer phenotype

While the cancer genome displays an overall decrease in the level of methylation compared with normal cells, CpG island-associated promoters, including tumor suppressor gene promoters, are commonly hypermethylated in cancer. Among the best-described methylation events in breast cancer are hypermethylations of p16ink4a (CDKN2A), RASSF1A, CCND2, APC, NES1 (KLK10), RARB, and HIN-1 (SCGD3A1 ) [24-32]. Several of these genes are also putative tumor suppressors, and aberrant promoter methylation is associated with gene repression and evasion of apoptosis or deregulation of the cell cycle. A recent study by Helman and colleagues [33] (2011) also demonstrated that hypermethylation of differentiation and developmental genes is crucial to lung carcinogenesis. Interestingly, several of these genes, such as PAX6, WT1, PROX1, HOXB13, HOXA1, and HOXA9, are also reported to be hypermethylated in breast cancer [34-38], suggesting that aberrant methylation and silencing of these gene sets may be as important to carcinogenesis as the aberrant silencing of tumor suppressors. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that the intrinsic molecular subtypes of breast cancer [39] exhibit different genomic methylation profiles [40,41]. Basal-like cancers, in particular, can be identified on the basis of their methylation level of a set of polycomb-regulated genes [40,41]. Given the relationship between the subtypes of breast cancer and patient outcome [39], understanding the relationship between DNA methylation and subtype may be of clinical relevance to breast cancer diagnosis or prognosis or both.

DNA methylation is an early event in breast carcinogenesis

Several studies have sought to elucidate the timing of methylation changes during breast carcinogenesis by comparing normal, pre-malignant lesions, and malignant breast tissue. In one such study, Park and colleagues [34] (2011) compared the methylation profile of 15 promoter-associated CpG islands in normal breast (NB) with the pre-malignant lesions atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and flat epithelial atypia (FEA) and the malignant lesions ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). The results showed that a significant increase in DNA methylation levels of promoter CpG islands occurred between NB and ADH/FEA. Additionally, there was a second significant gain in methylation between ADH/FEA and the malignant lesions, but no significant change in methylation profiles between DCIS and IDC, indicating that methylation is an early event in breast carcinogenesis (Figure 1). The data also agree with earlier reports of significant CpG island hypermethylation of estrogen receptor-alpha (ESR1), E-cadherin, RASSF1A, CCND2, p16, 14-3-3-σ, and SFRP1 in both DCIS and IDC [42-46]. Lehmann and colleagues [43] (2002) also assessed the methylation of CCDN2 across grade-1 to -3 DCIS and found that CCDN2 displayed higher methylation in higher-grade DCIS. This suggests that DNA hypermethylation occurs early in breast carcinogenesis and is associated with higher grade.

DNA methylation as a marker for diagnosis and prognosis

The tumor-specific nature of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) provides potential clinical biomarkers for cancer detection. Additionally, the presence of tumor-derived free DNA in the blood of patients with cancer [47,48] promises the development of simple and non-invasive tests for cancer diagnosis/prognosis. Many studies have associated promoter methylation (and subsequent gene silencing) in breast cancer with various clinic-pathological parameters. For example, hypermethylation at the promoters of putative tumor suppressors LATS1 and LATS2 was found to be associated with large tumor size, probability of metastasis, and negative estrogen/progesterone receptor status [44]. Hypermethylation of the repressor of wnt signaling, SFRP1, was associated with reduced overall survival [46], and hypermethylation of APC, CDH1, or CTNNB1 can distinguish cancer from normal tissue but is not associated with clinical outcome [49]. Table 1 provides a summary of all genes currently reported to have an association between promoter DNA hypermethylation or DNA hypomethylation (or both) and prognosis in breast cancer [36,46,50-74]. In this table, we have highlighted the cohort size and the method used to detect DNA methylation as each method has different sensitivity and specificity and may not necessarily be directly comparable. It is interesting to note that, despite the global hypomethylation of the cancer genome, only two studies found statistically significant associations between gene promoter hypomethylation and outcome of patients with breast cancer. However, hypomethylation of repetitive elements in the breast cancer genome has been associated with clinical outcome. Hypomethylation of long interspersed element 1 (LINE1) in a breast cancer cohort (379 primary ductal breast tumors, assayed by MethyLight) was associated with decreased overall survival (hazard ratio (HR) = 2.19, P = 0.014), decreased disease-free survival (HR = 2.05, P = 0.016), and increased distant recurrence (HR = 2.83, P = 0.001) in a multivariate analysis [75]. The relative lack of promoter hypomethylation in the cancer genome relative to the higher frequency of promoter hypermethylation may indicate different regulatory mechanisms and roles in carcinogenesis (reviewed in [76,77]).

Table 1.

A summary of aberrant DNA methylation associated with outcome in breast cancer

| Gene symbol | Tissue type | Hyper/Hypo | Cohort size | Detection method | Association with prognosis | P value | Hazard ratioa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACADL | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0001 | [50] | |

| BMP4 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.0002 | [51] | |

| BRCA1 | FFPE | Hyper | 536 tumors (Chinese patients) | MSP | Reduced disease-free survival | 0.045 | 1.45 | [52] |

| Reduced disease-specific survival | 0.038 | 1.56 | ||||||

| FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.018 | [51] | ||

| Serum | Hyper | 105 tumors, 20 unmatched normal | MSP | Poor prognosis | 0.002 | 6.4 | [53] | |

| FF | Hyper | 82 primary breast cancer tissues (Tunisian cohort) | MSP | Five-year survival | 0.016 | [54] | ||

| BRCA1 or P16 or both | Serum | Hyper | 105 tumors, 20 unmatched normal | MSP | Poor prognosis | 0.002 | 10.7 | [53] |

| C20ORF55 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.001 | [51] | |

| CDO1 | FF | Hyper | 163 tumors, 64 with distant metastasis | Q-BSSeq | Reduced time to distant metastasis | <0.0128 | >3.5 | [55] |

| Reduced metastasis-free survival | <0.0034 | |||||||

| CIDEB | FF | Hyper | 110 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.002 | 4.02 | [56] |

| CST6 | FFPE | Hyper | 93 carcinomas, 10 carcinomas with adjacent normal, 10 fibroadenomas, and 11 normal | MSP | Reduced disease-free interval Reduced overall survival | 0.004 0.001 | [57] | |

| Reduced disease-free interval | 0.027 | 3.48 | ||||||

| Reduced overall survival | 0.004 | 9.19 | ||||||

| DKK3 | FF | Hyper | 153 primary invasive cancers, 19 normal | MSP | Reduced overall survival | 0.011 | 14.4 | [58] |

| Reduced disease-free survival | 0.047 | 2.5 | ||||||

| ELK1 | FF | Hyper | 130 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.005 | 3.53 | [56] |

| ESR2 (ER-B) | FF | Hyper | 55 cancers | MSP | Increased incidence of relapse | 0.016 | [59] | |

| FGF12 | FF | Hyper | 113 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.004 | 3.31 | [56] |

| FGF4 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.029 | [51] | |

| FOXH1 | FF | Hyper | 129 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.00007 | 5.09 | [56] |

| FOXL2 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.02 | [51] | |

| GSTP1 | FF | Hyper | 176 invasive tumors (Japanese cohort) | MSP | Reduced relapse-free survival | <0.01 | [60] | |

| Poor prognosis | <0.05 | 2.77 | ||||||

| Poor prognosis | <0.01 | 7.13 | ||||||

| FFPE | Hyper | 974 primary in situ or invasive breast cancers | MethyLight | Increased breast cancer-specific mortality | NR | 1.71 | [61] | |

| FFPE | Hyper | 50 breast tumors | MSP | High Nottingham Prognostic Index | 0.0017 | [62] | ||

| HOXB13 | FF | Hyper | 57 ER-α+ tumors | QM-PCR | Reduced disease-free survival | 0.029 | 3.25 | [36] |

| ID4 | FF | Hyper | 171 tumors and match normal | MSP | Reduced recurrence-free survival | 0.036 | [63] | |

| ITIH5 | FF | Hyper | 109 tumors | MSP | Reduced overall survival | 0.008 | [64] | |

| ITR | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0041 | [50] | |

| KLK10 | FFPE | Hyper | 128 breast carcinomas, 10 breast carcinomas with paired adjacent normal, 10 breast fibroadenomas, and 11 normal | MSP | Reduced disease-free interval Reduced overall survival Increased incidence of relapse | 0.0025 0.003 0.026 |

/ / 3.49 |

[65] |

| LHX5 | FF | Hyper | 125 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.032 | 2.94 | [56] |

| MLH1 | FF | Hyper | 86 primary breast cancer tissues (Tunisian cohort) | MSP | Reduced overall survival | 0.015 | [54] | |

| NR2E1 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.02 | [51] | |

| OLIG2 | FF | Hyper | 115 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.023 | 2.56 | [56] |

| ONECUT1 | FF | Hyper | 128 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.023 | 2.8 | [56] |

| P16 | Serum | Hyper | 105 tumors, 20 unmatched normal | MSP | Poor prognosis | 0.001 | 5.5 | [53] |

| PITX2 | FFPE | Hyper | 427 invasive cancers | QM-PCR | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.004 | 2.75 | [66] |

| Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.013 | 2.35 | ||||||

| Reduced metastasis-free survival | 0.032 | 2.69 | ||||||

| FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | High risk of distant recurrence | 0.026 | [51] | ||

| Reduced time to distant metastasis | <0.001 | |||||||

| Reduced disease-free survival | 0.0084 | |||||||

| Reduced overall survival | 0.0003 | |||||||

| FF | Hyper | 236 node-negative tumors | Array/QM-PCR | Reduced metastasis-free survival | <0.00045 | >2.1 | [67] | |

| FF | Hyper | 416 tumors | QM-PCR | Reduced time to distant metastasis | <0.01 | 1.71 | [68] | |

| Reduced overall survival | <0.01 | 1.71 | ||||||

| Reduced metastasis-free survival | <0.01 | 1.74 | ||||||

| Reduced overall survival | 0.02 | 1.46 | ||||||

| PITX2/BMP4/c20orf55/fgf5 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Increased risk of distant recurrence Increased risk of distant recurrence | <0.01 <0.01 |

[51] | |

| RARB | FFPE | Hyper | 967 primary in situ or invasive breast cancers | MethyLight | Increased breast cancer-specific mortality | NR | 1.78 | [61] |

| RASSF1A | FF | Hyper | 80 tumors (Tunisian cohort) | MSP | Poor survival | 0.014 | [69] | |

| FFPE | Hyper | 93 carcinomas, 10 carcinomas with adjacent normal, 10 fibroadenomas, and 11 normal | MSP | Increased incidence of relapse Reduced disease-free survival | 0.011 0.028 |

[70] | ||

| FNA | Hyper | 237 patients with suspicious palpable lesions taken prior to surgery | QM-PCR | Reduced disease-free survival | 0.031 | OR = 2.53 | [71] | |

| RECK | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0001 | [50] | |

| SFRP1 | FF | Hyper | 131 tumors, 26 matched normal | MSP | Reduced overall survival | 0.045 | [46] | |

| SFRP2 | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0001 | [50] | |

| SFRP5 | FF | Hyper | 14 matched tumors and normal, 155 unmatched tumors | MSP | Reduced overall survival | 0.049 | 4.55 | [72] |

| SYNM | FF/FFPE | Hyper | 195 breast cancers | MSP | Reduced recurrence-free survival | 0.0282 | 2.94 | [73] |

| TDGF1 | FF | Hyper | 109 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.0009 | 4.08 | [56] |

| TLX3 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.008 | [51] | |

| TUBB3 | FF | Hyper | 121 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.035 | 3.19 | [56] |

| TWIST1 | FFPE | Hyper | 973 primary in situ or invasive breast cancers | MethyLight | Increased breast cancer-specific mortality | NR | 1.67 | [61] |

| UAP1L1 | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0005 | [50] | |

| UGT3A1 | NR | Hyper | 59 ductal carcinomas, 24 matched normal | IA/CoBRA | Reduced relapse-free survival | 0.0018 | [50] | |

| UNC5A | FF | Hyper | 111 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.027 | 2.74 | [56] |

| ZNF1A1 | FF | Hyper | 241 patients with breast cancer | MethyLight | Reduced time to distant metastasis | 0.044 | [51] | |

| BTG1 | FF | Hypo | 124 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.013 | 2.65 | [56] |

| GSC | FF | Hypo | 132 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.002 | 3.69 | [56] |

| HDAC4 | FF | Hypo | 117 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.016 | 2.62 | [56] |

| JUN | FF | Hypo | 131 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.025 | 2.44 | [56] |

| MKI67 (KI-67) | FF | Hypo | 116 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.004 | 3.43 | [56] |

| KIF2C | FF | Hypo | 118 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.008 | 2.65 | [56] |

| KLF4 | FF | Hypo | 114 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.009 | 2.63 | [56] |

| KLF5 | FF | Hypo | 123 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.004 | 3.56 | [56] |

| LHX2 | FF | Hypo | 126 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.028 | 2.32 | [56] |

| MAPK12 | FF | Hypo | 120 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.001 | 3.51 | [56] |

| MRD1 | FF/serum | Hypo | 100 invasive ductal carcinomas with matched normal and blood | MSP | Reduced overall survival | <0.01 | [74] | |

| ONECUT2 | FF | Hypo | 127 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.029 | 2.74 | [56] |

| SPRY1 | FF | Hypo | 112 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.002 | 4.0 | [56] |

| TOP1 | FF | Hypo | 108 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.0005 | 3.68 | [56] |

| UBE2C | FF | Hypo | 119 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.0009 | 3.57 | [56] |

| VEGF | FF | Hypo | 122 tumors, 11 normal (Indian cohort) | MOMA | Increased likelihood of relapse | 0.007 | 3.01 | [56] |

aHazard ratio given where reported. FF, fresh frozen; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; FNA, fine-needle aspirate; HR, hazard ratio; Hyper, hypermethylation; Hypo, hypomethylation; IA/CoBRA, infinium array/combined bisulfite restriction enzyme analysis; MOMA, methylation oligonucleotide analysis; MSP, methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; Q-BSSeq, quantitative bisulphite sequencing; QM-PCR, quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction.

Histone modification profiles are altered in cancer

Genome-wide studies of histone modification patterns have shown that specific histone modifications are associated with specific genomic functions and that these patterns are altered in cancer. For example, H3K4me3 (trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4) is a transcriptionally permissive histone modification associated with gene promoters [78] and can shed light on alternate promoter usage in carcinogenesis, whereas H3K27me3 is a repressive histone modification that marks large domains of the genome, including promoters, gene bodies, and inter-genic regions [79], and is important in development and differentiation. H3K27me3 marking is mediated by the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), and the repressive state is maintained by PRC1 [80]. The gene EZH2 encodes the catalytic subunit of PRC2, and upregulation of EZH2 in breast cancer has been associated with poor outcome [3]. Overexpression of EZH2 results in the formation of an alternate complex, PRC4, which displays diering substrate specificity relative to PRC2 and is expressed predominantly in undifferentiated tissue or cancer cells [81].

The active H3K4me3 and repressive H3K27me3 marks can co-occur on a single molecule (as confirmed by ChIP-reChIP [82]) and is termed bivalent marking. Bivalent marking of gene promoters occurs frequently in ESCs and typically is associated with important regulatory genes (for example, regulators of differentiation, tumor suppressors, and cell cycle regulators) [82]. Bivalent marking is associated with a transcriptionally poised state and is proposed to prevent aberrant gene expression but allow for rapid activation during differentiation. Notably, genes displaying bivalent histone marks in ESCs are reported to have an increased propensity to become aberrantly hypermethylated in cancer, but the mechanism underpinning this is unknown [83].

Integrated analysis of genetic and epigenetic data is a powerful tool in genomics research. The histone modification H3K27Ac is a mark of active regulatory sequences (that is, enhancers and promoters) [84]. A recent study by Ernst and colleagues [85] (2011) used the H3K27Ac profile from a range of cells to identify cell type-specific regulatory elements. By integrating the chromatin profiles of multiple cell types with known non-coding disease-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the authors found that non-coding SNPs often occurred within enhancer marked regions and disrupted transcription factor-binding sites. Therefore, it is important to consider both genetic and epigenetic aberrations in the investigation of carcinogenesis.

Human mammary epithelial cells as a model of breast carcinogenesis

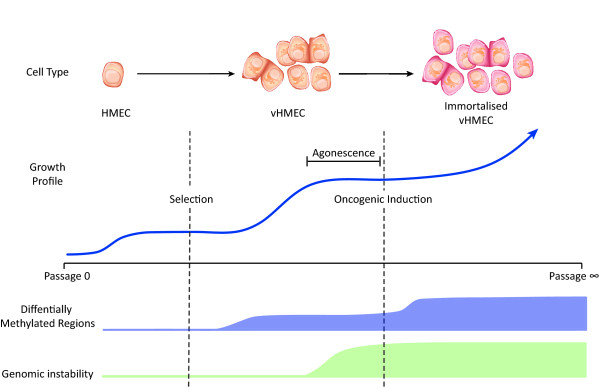

Although the integration of chromatin modifications, genetic data, and DNA methylation is likely to deliver novel insights into the biology of cancer, it is still difficult to identify the earliest epigenetic events in carcinogenesis without appropriate model systems. Clinical tumor samples and cancer cell lines contain a cacophony of genetic and epigenetic aberrations that potentially obscure crucial cancer-driving changes from passengers and, moreover, cannot easily capture the progression of epigenomic change during carcinogenesis. The HMEC model system promises to recapitulate the earliest stages of carcinogenesis in vitro. HMEC lines are established by the culture of breast epithelial cells taken from healthy, disease-free individuals during breast reduction mammoplasty [86]. In culture, HMECs will enter a temporary period of senescence (termed stasis or selection) from which a subpopulation of cells known as vHMECs (also termed post-selection HMECs) can escape (Figure 2) [86-94]. However, vHMECs are not immortalized and eventually enter an inescapable period of growth arrest termed agonescence [89]. During agonescence, the vHMEC population is unable to expand but retains unexpectedly high cell viability [89]. Initially, vHMECs display a relatively stable genome; however, as the cells approach agonescence, they rapidly acquire serious genomic defects and exhibit a wildly altered karyotype typical of early cancer lesions [90].

Figure 2.

Progression of the human mammary epithelial cell (HMEC) epigenome during growth. HMECs undergo a brief initial period of exponential growth followed by a temporary growth arrest termed selection/stasis. A subpopulation of vHMECs is able to escape this senescence and exhibit a second, longer period of exponential growth before becoming permanently arrested at agonescence. Much like during cancer progression, HMECs undergo a stepwise change in DNA methylation levels at selection/stasis and then again following the forced oncogene-induced escape from agonescence. vHMEC, variant human mammary epithelial cell.

Variant human mammary epithelial cells display cancer-associated epigenetic gene expression changes

Compared with HMECs, vHMECs display a significantly different expression program [88,93,95-102]. Among the earliest changes identified in vHMECs was the silencing of the tumor suppressor p16ink4a [96]. Silencing of p16ink4a occurs in all vHMEC populations and is associated with hypermethylation of the p16ink4a transcription start site (TSS) [87,88,96]. The gene encoding p16ink4a, CDKN2A, also encodes a second transcript called p14arf. The p14arf alternate TSS remains unmethylated in vHMECs, and transcription from this promoter is maintained. Notably, the p16ink4a locus is bivalently marked in HMECs, but in vHMECs H3K27me3 is lost in concert with a gain in promoter hypermethylation [103]. It is currently unclear whether vHMECs are a pre-existing subpopulation of normal HMECs or whether they arise de novo during selection in culture. Holst and colleagues [104] (2003) propose that vHMECs do exist prior to selection as the authors identified p16ink4a silenced and methylated p16ink4a cells in normal breast tissue, whereas Hinshelwood and colleagues [103] (2009) report that, in early vHMECs, p16ink4a methylation occurs only as the population of cells expand in culture and is a consequence of prior gene silencing. In addition to a change in p16ink4a expression, vHMECs display increased Cox-2 expression [97]. Cox-2 encodes a cyclo-oxygenase enzyme and is implicated in a wide variety of cancers, including breast cancer, to promote angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [105]. High Cox-2 expression in vHMECs is also associated with an increased rate of growth and high motility, and silencing of Cox-2 has been shown to reduce this malignant phenotype [97]. In addition to changes in individual gene expression, the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) pathway is consistently epigenetically silenced in vHMEC populations, and mutations in this pathway are commonly found in cancer. TGFβ pathway genes found to be silenced in vHMECs include TGFB2, the genes encoding the receptors TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, and an activator of TGFβ, THBS1 [101]. The TGFβ pathway is involved in regulation of the cell cycle, induction of apoptosis, and induction of differentiation. Detailed analysis demonstrated that genes in the TGFβ pathway are silenced without DNA hypermethylation and that gene silencing is associated with repressive chromatin remodelling and acquisition of H3K27me3 at gene promoters [101].

Interestingly, the PcG family of proteins is aberrantly regulated in vHMECs, specifi cally in the increased expression of SUZ12 and EZH2 [38]. SUZ12 and EZH2 are components of the PRC2 complex responsible for the methylation of histone 3 lysines 9 and 27 (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3). Increased expression of EZH2 has been associated with poor outcome in breast cancer [3,106-110]. As mentioned above, the PcG family of proteins plays important roles in the regulation of differentiation-related genes and may be involved in the recruitment of DNMTs [111]. In vHMECs, upregulation of SUZ12 and EZH2 appears to be linked to the silencing of p16ink4a [38]. Moreover, silencing of p16ink4a in HMECs by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) induced increased expression of SUZ12 and EZH2. The deregulation of the PcG in vHMECs also results in the inappropriate hyper-methylation of specific gene promoters. Silencing of p16ink4a or increased SUZ12 and EZH2 expression in HMECs leads to increased methylation at the HOXA9 promoter, mimicking its state in vHMECs [38]. Interestingly, hypermethylation was not seen in p16ink4a-silenced HMECs when SUZ12 was inhibited by shRNA. Additionally, the HOXA9 promoter was enriched for PcG proteins and DNMTs, suggesting a direct interaction. These results suggest that, in p16ink4a-silenced vHMECs, the PcG proteins and DNMTs interact to contribute to the pre-malignant breast cancer phenotype.

Variant human mammary epithelial cells proliferate rapidly despite elevated p53

In addition to the many cancer-associated changes, vHMECs exhibit upregulation of tumor suppressors, including several key members of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway [95,99,102]. The p53 protein is a key tumor suppressor and regulates the cell cycle through the activation of cell cycle checkpoints or apoptosis or both. Activation of checkpoints is achieved through DNA binding by p53 and the activation of p53 response genes, such as p21, which mediates p53-induced G1 cell cycle arrest [112-114]. Regulation of p53 is achieved through proteasomal degradation triggered by ubiquitinylation by the p53 regulator MDM2 [115-117]. In vHMECs, the p53 protein is stabilized, resulting in the upregulation of p21 [99,102]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that vHMECs contain a wild-type, mutation-free p53 protein [95,102] and that the p53 response to DNA damage remains intact [102]. However, vHMECs are able to expand faster than HMECs that have a low p53 expression. This increase in p53 stability has been linked to silencing of p16ink4a in two studies. Re-expression of p16ink4a in vHMECs results in reduced levels of p53 protein and p21 expression, whereas silencing of p16ink4a by shRNA in HMECs leads to p53/p21 activation [99,102]. In vHMECs, p53 is stabilized despite the presence of high levels of MDM2 expression. An investigation into this phenomenon found that vHMECs express a truncated 60-kDa isoform of MDM2 that can bind p53 but does not induce its degradation [102]. A 60-kDa form of MDM2 has been reported in multiple cancer cell lines as a result of caspase cleavage [118,119] that retains p53-binding capacity but lacks a C-terminal RING domain responsible for p53 ubiquitination [120]. This matches the properties of MDM2 observed in vHMECs. Silencing of p53 does not have an impact on the rate of growth of vHMECs [102]. Interestingly, silencing of p53 in an agonescent population results in loss of cell viability and widespread cell death [100], indicating that aberrations other than silencing of p53 are important in breast carcinogenesis.

Variant human mammary epithelial cells do not undergo oncogene-induced senescence

Normal cells use several checkpoints to prevent malignant transformation and one such checkpoint is oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). OIS was identified in 1997 when overexpression of mutant Ras in normal rodent cells resulted in permanent growth arrest via p16ink4a and p53 [121]. Overexpression of Ras in vHMECs did not induce OIS, whereas Ras expression in isogenic HMECs did induce senescence [94]. This may not be surprising, as vHMECs do not express p16ink4a. However, further studies have demonstrated that oncogenic Ras can induce OIS in HMECs in a p16ink4a-independent manner [122]. This study found that, in p16ink4a/p53-negative HMECs, Ras-induced senescence was suppressed by the antagonism of TGFβ signaling. The lack of TGFβ pathway expression in vHMECs likely serves as an additional factor in their ability to avoid OIS. It is interesting to note that the expression of oncogenic Ras in vHMECs did not result in carcinogenic transformation. Neither an increased growth rate nor increased genomic instability was reported in vHMEC-Ras cells [94]. However, exposure of vHMEC-Ras to low levels of serum in the growth media during agonescence did result in spontaneous immortalization and the capacity to overcome this second proliferative barrier. Removal of the serum stimulus did not cause these cells to revert to their mortal state and indicates that this transformation is permanent. However, immortalized vHMEC-Ras cells were not tumorigenic when injected into mice. The ability of vHMECs to avoid OIS is further evidence that they represent a partially transformed, pre-malignant breast cancer cell type.

Variant human mammary epithelial cells exhibit an aberrant methylome

DNA hypermethylation at the p16ink4a promoter is well documented in vHMECs but does not represent the only change across the genome. A study into genome-wide DNA methylation by Novak and colleagues [123] (2009) used MeDIP-chip (methylated DNA immunoprecipitation followed by hybridization to microarrays) analysis on HMEC and vHMEC populations. vHMECs displayed a large number of DMRs (n = 191) when compared with their isogenic counterparts; notably, there was a significant overlap between vHMEC DMRs and methylation status in tumor samples. To confirm that the progressive nature of DNA methylation change was due specifically to transformation and not to a slow ongoing process induced by prolonged culture (Figure 2), Novak and colleagues (2009) tested several time-points during HMEC and vHMEC growth. HMECs from early and late passages displayed a similar and stable methylome, as did early- and late-passage vHMECs. Overall, the vHMEC methylome remained stable until immortalization, in which vHMECs undergo a further significant change, indicating a stepwise progression of DNA methylation during HMEC transformation, much like that reported in breast carcinogenesis (Figures 1 and 2). Notably, several of the genes reported as differentially methylated in vHMECs by Novak and colleagues (2009) also appear in the list of breast cancer prognostic marker genes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overlap of genes reported as hypermethylated in variant human mammary epithelial cells and as potential prognostic epigenetic markers in breast cancer

| Gene symbol | Methylation in vHMECs | P value of vHMECs | Methylation in immortal vHMECs | P value of immortal vHMECs | Methylation in cancer | Association in cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDO1 | NA | NA | Hyper | <0.003 | Hyper | Reduced time to distant metastasis and reduced metastasis-free survival |

| CIDEB | Hyper | 0.001 | Hyper | <0.000006 | Hyper | Increased likelihood of relapse |

| ESR2 (ER-B) | Hyper | 0.000002 | Hyper | <0.000009 | Hyper | Increased incidence of Relapse |

| FOXL2 | NA | NA | Hyper | 0.001 | Hyper | Reduced time to distant metastasis |

| ID4 | Hyper | <0.004 | Hyper | <0.004 | Hyper | Reduced recurrence-free survival |

| NR2E1 | Hyper | 0.00001 | Hyper | <0.000007 | Hyper | Reduced time to distant metastasis |

| OLIG2 | Hyper | <0.01 | Hyper | <0.008 | Hyper | Increased likelihood of relapse |

| TLX3 | NA | NA | Hyper | <0.003 | Hyper/Hypo | Reduced time to distant metastasis |

| KIF2C | Hyper | 0.004 | NA | NA | Hypo | Increased likelihood of relapse |

| TOP1 | NA | NA | Hypo | 0.01 | Hypo | Increased likelihood of relapse |

| VEGF | NA | NA | Hyper | 0.001 | Hypo | Increased likelihood of relapse |

Hyper, hypermethylation; Hypo, hypomethylation; NA, not available; vHMEC, variant human mammary epithelial cell.

Temporal changes in DNA methylation occur as variant human mammary epithelial cells escape senescence

Despite the demonstrated stability of the vHMEC methylome [123], there is significant heterogeneity in methylation patterns across the p16 ink4a promoter as determined by bisulphite sequencing. Some regions at this site appear to be protected from hypermethylation during gene silencing [103]. Until recently, whether methylation at the p16ink4a promoter was a cause or consequence of gene silencing was unknown. A study by Hinshelwood and colleagues [103] (2009) assessed hypermethylation of the p16ink4a promoter region of vHMECs in the first few population doublings following selection by using laser capture and found that p16ink4a was silenced prior to hypermethylation. The study also found that DNA hypermethylation was initiated at distinct foci or 'hot spots' of DNA methylation that occurred at a regular pattern across the promoter, in accordance with the pattern of nucleosome occupancy (that is, approximately 147 bp unmethylated region followed by approximately 50 bp of hypermethylation). In a further investigation, chromatin from vHMECs was treated with the DNMT enzyme SssI in vitro. SssI can access only free DNA not bound to nucleosomes, and only the 50-bp linker region between nucleosomes is methylated during treatment. Bisulphite sequencing revealed foci of DNA methylation separated by a hypomethylated nucleosome-bound region that matched the methylation pattern seen in vivo. Hinshelwood and colleagues [103] (2009) proposed that silencing of p16ink4a is initiated in conjunction with the acquisition of repressive histone marks and that pre-existing hot spots of DNA methylation may serve as seeds of permanent silencing and the recruitment of DNMTs and other repressive complexes.

Future challenges for the human mammary epithelial cell system

Extension of this model system to include early malignancy should also be a focus of the breast cancer research field. To date, there is no system in which a study may follow the transformation from normal to pre-malignant to early malignant lesion (that is, DCIS) or beyond. Previous attempts to grow HMECs or vHMECs in mice have been unsuccessful without the introduction of oncogenes or humanizing the mouse mammary fat pad with human fibroblasts. When grown in humanized cleared mouse mammary fat pads, HMECs are able to generate normal breast ductal structures [124]. Additionally, the implantation of HMECs into mouse mammary fat pads humanized with fibroblasts transformed to abnormally express key growth factors resulted in the generation of structures similar to those seen in early breast malignancy [124]. These results demonstrate that the HMEC system is also a useful model for studies of the role of cancer/stroma interactions during carcinogenesis. The development of further model systems using HMECs and vHMECs that follow the natural progression of cancer growth in vivo will be invaluable to the understanding of breast cancer biology.

Conclusions

This review has presented much evidence that demonstrates that epigenetic dysregulation is well established as a major contributor to cancer progression and phenotype. It can be clearly seen that changes in DNA methylation contribute to a wide variety of cancer-associated phenomena such as genomic instability, silencing of tumor suppressors, and inappropriate regulation of differentiation-associated pathways. Chromatin remodelling is also a powerful tool in the evolving cancer cell and contributes to deregulation of gene expression and the inappropriate targeting of DNA methylation observed in cancer. These epigenomic phenomena are being studied with ever more powerful, sensitive, and well-developed tools (for example, ChIP-seq), and use of next-generation genomics approaches demands the use of an equally powerful and sensitive model system. It should be clear that this role could be filled by the HMEC model system. HMECs and vHMECs are able to recreate in vitro the very earliest stages of carcinogenesis and exhibit a wide variety of cancer-associated expression, chromatin, and DNA methylation changes. Additionally, the HMEC system can be used to provide temporal information that cannot be obtained by using cancer cell lines or tissue samples, particularly in the very early stages of oncogenic transformation. In terms of both the generation of cancer biomarkers and the understanding of cancer biology, the HMEC system promises to deliver findings otherwise unavailable to cancer researchers.

Abbreviations

ADH: atypical ductal hyperplasia; bp: base pair; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation; ChIP-seq: chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing; CpG: cytosine followed by guanosine dinucleotide; CpG island: regions of the genome containing a high density of CpG (cytosine followed by guanosine dinucleotide) sites; DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; DMR: differentially methylated region; DNMT: DNA methyltransferase; ESC: embryonic stem cell; EZH2: enhancer of Zeste homologue 2; FEA: flat epithelial atypia; H3K27Ac: acetylated histone 3: lysine 27; H3K4me3: trimethylated histone 3 lysine 4; HDAC: histone de-acetylase; HMEC: human mammary epithelial cell; HR: hazard ratio; IDC: invasive ductal carcinoma; NB: normal breast; OIS: oncogene-induced senescence; PcG: polycomb group; PRC1: polycomb repressive complex 1; PRC2: polycomb repressive complex 2; shRNA: short hairpin RNA; SNP: single-nucleotide polymorphism; TGFβ: transforming growth factor beta; TSS: transcription start site; vHMEC: variant human mammary epithelial cell.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Warwick J Locke, Email: w.locke@garvan.org.au.

Susan J Clark, Email: s.clark@garvan.org.au.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kate Patterson for help with figures and grant support from the National Breast Cancer Foundation and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

References

- Lennartsson A, Ekwall K. Histone modification patterns and epigenetic codes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;14:863–868. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancotto C, Frige G, Minucci S. Histone modification therapy of cancer. Adv Genet. 2010;14:341–386. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380866-0.60013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;14:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göttlicher M, Minucci S, Zhu P, Krämer OH, Schimpf A, Giavara S, Sleeman JP, Lo Coco F, Nervi C, Pelicci PG, Heinzel T. Valproic acid defines a novel class of HDAC inhibitors inducing differentiation of transformed cells. EMBO J. 2001;14:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;14:27–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, Funke R, Gage D, Harris K, Heaford A, Howland J, Kann L, Lehoczky J, LeVine R, McEwan P, McKernan K, Meldrim J, Mesirov JP, Miranda C, Morris W, Naylor J, Raymond C, Rosetti M, Santos R, Sheridan A, Sougnez C, Stange-Thomann N, Stojanovic N. et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;14:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josse J, Kaiser AD, Kornberg A. Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid VIII. Frequencies of nearest neighbor base sequences in deoxyribonucleic acid.<//b>. J Biol Chem. 1961;14:864–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A, Taggart M, Frommer M, Miller OJ, Macleod D. A fraction of the mouse genome that is derived from islands of nonmethylated, CpG-rich DNA. Cell. 1985;14:91–99. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner-Garden M, Frommer M. CpG islands in vertebrate genomes. J Mol Biol. 1987;14:261–282. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, Pelizzola M, Dowen RH, Hawkins RD, Hon G, Tonti-Filippini J, Nery JR, Lee L, Ye Z, Ngo QM, Edsall L, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Stewart R, Ruotti V, Millar AH, Thomson JA, Ren B, Ecker JR. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;14:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MP, Li JB, Gao Y, Lee JH, LeProust EM, Park IH, Xie B, Daley GQ, Church GM. Targeted and genome-scale strategies reveal gene-body methylation signatures in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;14:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZX, Riggs AD. DNA methylation and demethylation in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2011;14:18347–18353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.205286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhayalan A, Rajavelu A, Rathert P, Tamas R, Jurkowska RZ, Ragozin S, Jeltsch A. The Dnmt3a PWWP domain reads histone 3 lysine 36 trimethylation and guides DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2010;14:26114–26120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.089433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;14:1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloushtain-Qimron N, Yao J, Snyder EL, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Mani SA, Hu M, Chen H, Ustyansky V, Antosiewicz JE, Argani P, Halushka MK, Thomson JA, Pharoah P, Porgador A, Sukumar S, Parsons R, Richardson AL, Stampfer MR, Gelman RS, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Polyak K. Cell type-specific DNA methylation patterns in the human breast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;14:14076–14081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805206105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama R, Choudhury S, Kowalczyk A, Bessarabova M, Beresford-Smith B, Conway T, Kaspi A, Wu Z, Nikolskaya T, Merino VF, Lo PK, Liu XS, Nikolsky Y, Sukumar S, Haviv I, Polyak K. Epigenetic regulation of cell type-specific expression patterns in the human mammary epithelium. PLoS Genet. 2011;14:e1001369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshelwood RA, Clark SJ. Breast cancer epigenetics: normal human mammary epithelial cells as a model system. J Mol Med. 2008;14:1315–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gama-Sosa MA, Slagel VA, Trewyn RW, Oxenhandler R, Kuo KC, Gehrke CW, Ehrlich M. The 5-methylcytosine content of DNA from human tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;14:6883–6894. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.19.6883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet F, Hodgson JG, Eden A, Jackson-Grusby L, Dausman J, Gray JW, Leonhardt H, Jaenisch R. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science. 2003;14:489–492. doi: 10.1126/science.1083558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalos A, Nikolaidis G, Xinarianos G, Savvari P, Cassidy A, Zakopoulou R, Kotsinas A, Gorgoulis V, Field JK, Liloglou T. Hypomethylation of retrotransposable elements correlates with genomic instability in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;14:81–87. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan A, Ji W, Zhang XY, Marrogi A, Graff JR, Baylin SB, Ehrlich M. Hypomethylation of pericentromeric DNA in breast adenocarcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1998;14:833–838. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980911)77:6<833::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prada D, González R, Sánchez L, Castro C, Fabián E, Herrera LA. Satellite 2 demethylation induced by 5-azacytidine is associated with missegregation of chromosomes 1 and 16 in human somatic cells. Mutat Res. 2012;14:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M, Krassowska A, Gilbert N, Chevassut T, Forrester L, Ansell J, Ramsahoye B. Severe global DNA hypomethylation blocks differentiation and induces histone hyperacetylation in embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;14:8862–8871. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8862-8871.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani AK, Rathi A, Sathyanarayana UG, Padar A, Huang CX, Cunnigham HT, Farinas AJ, Milchgrub S, Euhus DM, Gilcrease M, Herman J, Minna JD, Gazdar AF. Aberrant methylation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene promoter 1A in breast and lung carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;14:1998–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Tamura G, Tsuchiya T, Sakata K, Kashiwaba M, Osakabe M, Motoyama T. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene promoter hypermethylation in primary breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 2001;14:69–73. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JG, Merlo A, Mao L, Lapidus RG, Issa JP, Davidson NE, Sidransky D, Baylin SB. Inactivation of the CDKN2/p16/MTS1 gene is frequently associated with aberrant DNA methylation in all common human cancers. Cancer Res. 1995;14:4525–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann R, Yang G, Pfeifer GP. Hypermethylation of the cpG island of Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A), a putative tumor suppressor gene from the 3p21.3 locus, occurs in a large percentage of human breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2001;14:3105–3109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evron E, Umbricht CB, Korz D, Raman V, Loeb DM, Niranjan B, Buluwela L, Weitzman SA, Marks J, Sukumar S. Loss of cyclin D2 expression in the majority of breast cancers is associated with promoter hypermethylation. Cancer Res. 2001;14:2782–2787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Goyal J, Dhar S, Dimri G, Evron E, Sukumar S, Wazer DE, Band V. CpG methylation as a basis for breast tumor-specific loss of NES1/kallikrein 10 expression. Cancer Res. 2001;14:8014–8021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Shan L, Yoshimura G, Nakamura M, Nakamura Y, Suzuma T, Umemura T, Mori I, Sakurai T, Kakudo K. 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine induces retinoic acid receptor beta 2 demethylation, cell cycle arrest and growth inhibition in breast carcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2002;14:2753–2756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias EF, Arapshian A, Bleiweiss IJ, Waxman S, Zelent A, Mira-Y-Lopez R. Retinoic acid receptor alpha2 is a growth suppressor epigenetically silenced in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;14:335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fackler MJ, McVeigh M, Evron E, Garrett E, Mehrotra J, Polyak K, Sukumar S, Argani P. DNA methylation of RASSF1A, HIN-1, RAR-beta, Cyclin D2 and Twist in in situ and invasive lobular breast carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;14:970–975. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helman E, Naxerova K, Kohane IS. DNA hypermethylation in lung cancer is targeted at differentiation-associated genes. Oncogene. 2011;14:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Kwon HJ, Lee HE, Ryu HS, Kim SW, Kim JH, Kim IA, Jung N, Cho NY, Kang GH. Promoter CpG island hypermethylation during breast cancer progression. Virchows Arch. 2011;14:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-1013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moelans CB, Verschuur-Maes AH, van Diest PJ. Frequent promoter hypermethylation of BRCA2, CDH13, MSH6, PAX5, PAX6 and WT1 in ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. J Pathol. 2011;14:222–231. doi: 10.1002/path.2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BA, Cheng AS, Yan PS, Potter D, Agosto-Perez FJ, Shapiro CL, Huang TH. Epigenetic repression of the estrogen-regulated Homeobox B13 gene in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2008;14:1459–1465. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versmold B, Felsberg J, Mikeska T, Ehrentraut D, Köhler J, Hampl JA, Röhn G, Niederacher D, Betz B, Hellmich M, Pietsch T, Schmutzler RK, Waha A. Epigenetic silencing of the candidate tumor suppressor gene PROX1 in sporadic breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;14:547–554. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PA, Sigaroudinia M, Zardo G, Wilson MB, Benton GM, Miller CJ, Hong C, Fridlyand J, Costello JF, Tlsty TD. Tumor suppressor p16INK4A regulates polycomb-mediated DNA hypermethylation in human mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;14:24790–24802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Lønning PE, Børresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;14:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easwaran H, Johnstone SE, Van Neste L, Ohm J, Mosbruger T, Wang Q, Aryee MJ, Joyce P, Ahuja N, Weisenberger D, Collisson E, Zhu J, Yegnasubramanian S, Matsui W, Baylin SB. A DNA hypermethylation module for the stem/progenitor cell signature of cancer. Genome Res. 2012;14:837–849. doi: 10.1101/gr.131169.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm K, Hegardt C, Staaf J, Vallon-Christersson J, Jönsson G, Olsson H, Borg A, Ringnér M. Molecular subtypes of breast cancer are associated with characteristic DNA methylation patterns. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/bcr2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nass SJ, Herman JG, Gabrielson E, Iversen PW, Parl FF, Davidson NE, Graff JR. Aberrant methylation of the estrogen receptor and E-cadherin 5' CpG islands increases with malignant progression in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;14:4346–4348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann U, Länger F, Feist H, Glöckner S, Hasemeier B, Kreipe H. Quantitative assessment of promoter hypermethylation during breast cancer development. Am J Pathol. 2002;14:605–612. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64880-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Miyoshi Y, Takahata C, Irahara N, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Down-regulation of LATS1 and LATS2 mRNA expression by promoter hypermethylation and its association with biologically aggressive phenotype in human breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;14:1380–1385. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo PK, Mehrotra J, D'Costa A, Fackler MJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Argani P, Sukumar S. Epigenetic suppression of secreted frizzled related protein 1 (SFRP1) expression in human breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;14:281–286. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.3.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeck J, Niederacher D, An H, Klopocki E, Wiesmann F, Betz B, Galm O, Camara O, Dürst M, Kristiansen G, Huszka C, Knüchel R, Dahl E. Aberrant methylation of the Wnt antagonist SFRP1 in breast cancer is associated with unfavourable prognosis. Oncogene. 2006;14:3479–3488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroun M, Anker P, Maurice P, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Beljanski M. Neoplastic characteristics of the DNA found in the plasma of cancer patients. Oncology. 1989;14:318–322. doi: 10.1159/000226740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V, Anker P, Maurice P, Lyautey J, Lederrey C, Stroun M. Point mutations of the N-ras gene in the blood plasma DNA of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 1994;14:774–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoque MO, Prencipe M, Poeta ML, Barbano R, Valori VM, Copetti M, Gallo AP, Brait M, Maiello E, Apicella A, Rossiello R, Zito F, Stefania T, Paradiso A, Carella M, Dallapiccola B, Murgo R, Carosi I, Bisceglia M, Fazio VM, Sidransky D, Parrella P. Changes in CpG islands promoter methylation patterns during ductal breast carcinoma progression. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;14:2694–2700. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill VK, Ricketts C, Bieche I, Vacher S, Gentle D, Lewis C, Maher ER, Latif F. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of CpG islands in breast cancer identifies novel genes associated with tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2011;14:2988–2999. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann O, Spyratos F, Harbeck N, Dietrich D, Fassbender A, Schmitt M, Eppenberger-Castori S, Vuaroqueaux V, Lerebours F, Welzel K, Maier S, Plum A, Niemann S, Foekens JA, Lesche R, Martens JW. DNA methylation markers predict outcome in node-positive, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer with adjuvant anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;14:315–323. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhou J, Xu Y, Li Z, Wen X, Yao L, Xie Y, Deng D. BRCA1 promoter methylation associated with poor survival in Chinese patients with sporadic breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009;14:1663–1667. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing F, Jun L, Yong Z, Wang Y, Fei X, Zhang J, Hu L. Multigene methylation in serum of sporadic Chinese female breast cancer patients as a prognostic biomarker. Oncology. 2008;14:60–66. doi: 10.1159/000155145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karray-Chouayekh S, Trifa F, Khabir A, Boujelbane N, Sellami-Boudawara T, Daoud J, Frikha M, Gargouri A, Mokdad-Gargouri R. Clinical significance of epigenetic inactivation of hMLH1 and BRCA1 in Tunisian patients with invasive breast carcinoma. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;14:369129. doi: 10.1155/2009/369129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich D, Krispin M, Dietrich J, Fassbender A, Lewin J, Harbeck N, Schmitt M, Eppenberger-Castori S, Vuaroqueaux V, Spyratos F, Foekens JA, Lesche R, Martens JW. CDO1 promoter methylation is a biomarker for outcome prediction of anthracycline treated, estrogen receptor-positive, lymph node-positive breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2010;14:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalakaran S, Varadan V, Giercksky Russnes HE, Levy D, Kendall J, Janevski A, Riggs M, Banerjee N, Synnestvedt M, Schlichting E, Kåresen R, Shama Prasada K, Rotti H, Rao R, Rao L, Eric Tang MH, Satyamoorthy K, Lucito R, Wigler M, Dimitrova N, Naume B, Borresen-Dale AL, Hicks JB. DNA methylation patterns in luminal breast cancers differ from non-luminal subtypes and can identify relapse risk independent of other clinical variables. Mol Oncol. 2011;14:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioulafa M, Balkouranidou I, Sotiropoulou G, Kaklamanis L, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Lianidou ES. Methylation of cystatin M promoter is associated with unfavorable prognosis in operable breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;14:2887–2892. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeck J, Wild PJ, Fuchs T, Schüffler PJ, Hartmann A, Knüchel R, Dahl E. Prognostic relevance of Wnt-inhibitory factor-1 (WIF1) and Dickkopf-3 (DKK3) promoter methylation in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;14:217. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rody A, Holtrich U, Solbach C, Kourtis K, von Minckwitz G, Engels K, Kissler S, Gätje R, Karn T, Kaufmann M. Methylation of estrogen receptor beta promoter correlates with loss of ER-beta expression in mammary carcinoma and is an early indication marker in premalignant lesions. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;14:903–916. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Miyoshi Y, Kim SJ, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. Association of GSTP1 CpG islands hypermethylation with poor prognosis in human breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;14:169–176. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YH, Shen J, Gammon MD, Zhang YJ, Wang Q, Gonzalez K, Xu X, Bradshaw PT, Teitelbaum SL, Garbowski G, Hibshoosh H, Neugut AI, Chen J, Santella RM. Prognostic significance of gene-specific promoter hypermethylation in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;14:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1712-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasabova Z, Tilandyova P, Kajo K, Zubor P, Burjanivova T, Danko J, Plank L. Hypermethylation of the GSTP1 promoter region in breast cancer is associated with prognostic clinicopathological parameters. Neoplasma. 2010;14:35–40. doi: 10.4149/neo_2010_01_035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noetzel E, Veeck J, Niederacher D, Galm O, Horn F, Hartmann A, Knüchel R, Dahl E. Promoter methylation-associated loss of ID4 expression is a marker of tumour recurrence in human breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;14:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeck J, Chorovicer M, Naami A, Breuer E, Zafrakas M, Bektas N, Dürst M, Kristiansen G, Wild PJ, Hartmann A, Knuechel R, Dahl E. The extracellular matrix protein ITIH5 is a novel prognostic marker in invasive node-negative breast cancer and its aberrant expression is caused by promoter hypermethylation. Oncogene. 2008;14:865–876. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioulafa M, Kaklamanis L, Stathopoulos E, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Lianidou ES. Kallikrein 10 (KLK10) methylation as a novel prognostic biomarker in early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;14:1020–1025. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck N, Nimmrich I, Hartmann A, Ross JS, Cufer T, Grützmann R, Kristiansen G, Paradiso A, Hartmann O, Margossian A, Martens J, Schwope I, Lukas A, Müller V, Milde-Langosch K, Nährig J, Foekens J, Maier S, Schmitt M, Lesche R. Multicenter study using paraffin-embedded tumor tissue testing PITX2 DNA methylation as a marker for outcome prediction in tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2008;14:5036–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier S, Nimmrich I, Koenig T, Eppenberger-Castori S, Bohlmann I, Paradiso A, Spyratos F, Thomssen C, Mueller V, Nährig J, Schittulli F, Kates R, Lesche R, Schwope I, Kluth A, Marx A, Martens JW, Foekens JA, Schmitt M, Harbeck N. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PathoBiology group. DNA-methylation of the homeodomain transcription factor PITX2 reliably predicts risk of distant disease recurrence in tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer patients--Technical and clinical validation in a multi-centre setting in collaboration with the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PathoBiology group. Eur J Cancer. 2007;14:1679–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmrich I, Sieuwerts AM, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Schwope I, Bolt-de Vries J, Harbeck N, Koenig T, Hartmann O, Kluth A, Dietrich D, Magdolen V, Portengen H, Look MP, Klijn JG, Lesche R, Schmitt M, Maier S, Foekens JA, Martens JW. DNA hypermethylation of PITX2 is a marker of poor prognosis in untreated lymph node-negative hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;14:429–437. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9800-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karray-Chouayekh S, Trifa F, Khabir A, Boujelbane N, Sellami-Boudawara T, Daoud J, Frikha M, Jlidi R, Gargouri A, Mokdad-Gargouri R. Aberrant methylation of RASSF1A is associated with poor survival in Tunisian breast cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;14:203–210. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kioulafa M, Kaklamanis L, Mavroudis D, Georgoulias V, Lianidou ES. Prognostic significance of RASSF1A promoter methylation in operable breast cancer. Clin Biochem. 2009;14:970–975. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins AT, Monteiro P, Ramalho-Carvalho J, Costa VL, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Leal C, Henrique R, Jerónimo C. High RASSF1A promoter methylation levels are predictive of poor prognosis in fine-needle aspirate washings of breast cancer lesions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;14:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeck J, Geisler C, Noetzel E, Alkaya S, Hartmann A, Knüchel R, Dahl E. Epigenetic inactivation of the secreted frizzled-related protein-5 (SFRP5) gene in human breast cancer is associated with unfavorable prognosis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;14:991–998. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noetzel E, Rose M, Sevinc E, Hilgers RD, Hartmann A, Naami A, Knüchel R, Dahl E. Intermediate filament dynamics and breast cancer: aberrant promoter methylation of the Synemin gene is associated with early tumor relapse. Oncogene. 2010;14:4814–4825. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Mirza S, Parshad R, Srivastava A, Datta Gupta S, Pandya P, Ralhan R. CpG hypomethylation of MDR1 gene in tumor and serum of invasive ductal breast carcinoma patients. Clin Biochem. 2010;14:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hoesel AQ, van de Velde CJ, Kuppen PJ, Liefers GJ, Putter H, Sato Y, Elashoff DA, Turner RR, Shamonki JM, de Kruijf EM, van Nes JG, Giuliano AE, Hoon DS. Hypomethylation of LINE-1 in primary tumor has poor prognosis in young breast cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;14:1103–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;14:5400–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;14:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;14:73–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y, Shen L, Cheng AS, Ahmed S, Boumber Y, Charo C, Yamochi T, Urano T, Furukawa K, Kwabi-Addo B, Gold DL, Sekido Y, Huang TH, Issa JP. Gene silencing in cancer by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation independent of promoter DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2008;14:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ng.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;14:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmichev A, Margueron R, Vaquero A, Preissner TS, Scher M, Kirmizis A, Ouyang X, Brockdorff N, Abate-Shen C, Farnham P, Reinberg D. Composition and histone substrates of polycomb repressive group complexes change during cellular differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;14:1859–1864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409875102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;14:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm JE, McGarvey KM, Yu X, Cheng L, Schuebel KE, Cope L, Mohammad HP, Chen W, Daniel VC, Yu W, Berman DM, Jenuwein T, Pruitt K, Sharkis SJ, Watkins DN, Herman JG, Baylin SB. A stem cell-like chromatin pattern may predispose tumor suppressor genes to DNA hypermethylation and heritable silencing. Nat Genet. 2007;14:237–242. doi: 10.1038/ng1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, Boyer LA, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;14:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, Ku M, Durham T, Kellis M, Bernstein BE. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;14:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SL, Ham RG, Stampfer MR. Serum-free growth of human mammary epithelial cells: <b>rapid clonal growth in defined medium and extended serial passage with pituitary extract. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;14:5435–5439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AJ, Stampfer MR, Aldaz CM. Increased p16 expression with first senescence arrest in human mammary epithelial cells and extended growth capacity with p16 inactivation. Oncogene. 1998;14:199–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huschtscha LI, Noble JR, Neumann AA, Moy EL, Barry P, Melki JR, Clark SJ, Reddel RR. Loss of p16INK4 expression by methylation is associated with lifespan extension of human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1998;14:3508–3512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov SR, Kozakiewicz BK, Holst CR, Stampfer MR, Haupt LM, Tlsty TD. Normal human mammary epithelial cells spontaneously escape senescence and acquire genomic changes. Nature. 2001;14:633–637. doi: 10.1038/35054579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlsty TD, Romanov SR, Kozakiewicz BK, Holst CR, Haupt LM, Crawford YG. Loss of chromosomal integrity in human mammary epithelial cells subsequent to escape from senescence. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2001;14:235–243. doi: 10.1023/A:1011369026168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlsty TD, Crawford YG, Holst CR, Fordyce CA, Zhang J, McDermott K, Kozakiewicz K, Gauthier ML. Genetic and epigenetic changes in mammary epithelial cells may mimic early events in carcinogenesis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;14:263–274. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048773.95897.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H, Zhang J, Crawford YG, Gauthier ML, Fordyce CA, McDermott KM, Sigaroudinia M, Kozakiewicz K, Tlsty TD. Genetic and epigenetic changes in mammary epithelial cells identify a subpopulation of cells involved in early carcinogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;14:317–327. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Pan J, Li JL, Lee JH, Tunkey C, Saraf K, Garbe JC, Whitley MZ, Jelinsky SA, Stampfer MR, Haney SA. Transcriptional changes associated with breast cancer occur as normal human mammary epithelial cells overcome senescence barriers and become immortalized. Mol Cancer. 2007;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont N, Crawford YG, Sigaroudinia M, Nagrani SS, Wilson MB, Buehring GC, Turashvili G, Aparicio S, Gauthier ML, Fordyce CA, McDermott KM, Tlsty TD. Human mammary cancer progression model recapitulates methylation events associated with breast premalignancy. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;14:R87. doi: 10.1186/bcr2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmolino L, Band H, Band V. Expression and stability of p53 protein in normal human mammary epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:827–832. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SA, Wong DJ, Barrett MT, Galloway DA. Inactivation of p16 in human mammary epithelial cells by CpG island methylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;14:1793–1801. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford YG, Gauthier ML, Joubel A, Mantei K, Kozakiewicz K, Afshari CA, Tlsty TD. Histologically normal human mammary epithelia with silenced p16(INK4a) overexpress COX-2, promoting a premalignant program. Cancer Cell. 2004;14:263–273. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier ML, Pickering CR, Miller CJ, Fordyce CA, Chew KL, Berman HK, Tlsty TD. p38 regulates cyclooxygenase-2 in human mammary epithelial cells and is activated in premalignant tissue. Cancer Res. 2005;14:1792–1799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Pickering CR, Holst CR, Gauthier ML, Tlsty TD. p16INK4a modulates p53 in primary human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2006;14:10325–10331. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbe JC, Holst CR, Bassett E, Tlsty T, Stampfer MR. Inactivation of p53 function in cultured human mammary epithelial cells turns the telomere-length dependent senescence barrier from agonescence into crisis. Cell Cycle. 2007;14:1927–1936. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.15.4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshelwood RA, Huschtscha LI, Melki J, Stirzaker C, Abdipranoto A, Vissel B, Ravasi T, Wells CA, Hume DA, Reddel RR, Clark SJ. Concordant epigenetic silencing of transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway genes occurs early in breast carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;14:11517–11527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]