Abstract

We show that thiols in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif of DksA, an RNA polymerase accessory protein known to regulate the stringent response, sense oxidative and nitrosative stress. Hydrogen peroxide- or nitric oxide (NO)-mediated modifications of thiols in the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif release the metal cofactor and drive reversible changes in the α-helicity of the protein. Wild-type and relA spoT mutant Salmonella, but not isogenic dksA-deficient bacteria, experience the downregulation of r-protein and amino acid transport expression after NO treatment, suggesting that DksA can regulate gene expression in response to NO congeners independently of the ppGpp alarmone. Oxidative stress enhances the DksA-dependent repression of rpsM, while preventing the activation of livJ and hisG gene transcription that is supported by reduced, zinc-bound DksA. The inhibitory effects of oxidized DksA on transcription are reversible with dithiothreitol. Our investigations indicate that sensing of reactive species by DksA redox active thiols fine-tunes the expression of translational machinery and amino acid assimilation and biosynthesis in accord with the metabolic stress imposed by oxidative and nitrosative stress. Given the conservation of Cys114, and neighboring hydrophobic and charged amino acids in DksA orthologues, phylogenetically diverse microorganisms may use the DksA thiol switch to regulate transcriptional responses to oxidative and nitrosative stress.

INTRODUCTION

The univalent and divalent reduction of oxygen by cytosolic and electron transport chain flavoproteins are important sources of endogenous oxidative stress in aerobic organisms (Messner and Imlay, 1999; Seaver and Imlay, 2004). The NADPH oxidase-mediated respiratory burst of professional phagocytes enhances the degree of oxidative stress experienced by pathogenic microorganisms, such as Salmonella, during their associations with host cells (Mastroeni et al., 2000; Vazquez-Torres et al., 2000). During infection, microorganisms also encounter nitrosative stress emanating from the production of nitric oxide (NO) generated by the reduction of nitrite or the inducible NO synthase-mediated oxidation of the guanidino group of L-arginine (Fang, 2004; Mastroeni et al., 2000; Vazquez-Torres et al., 2000). The reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated by these processes modify and disrupt critical metal cofactors and thiol groups in key enzymes of glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and amino acid biosynthetic pathways, thereby exerting considerable metabolic stress on the bacterial cell (Brandes et al., 2007; Keyer and Imlay, 1997; Kuo et al., 1987). Reactive species also exert direct genotoxicity on DNA molecules (Imlay and Linn, 1988; Moody and Hassan, 1982; Richardson et al., 2009). Given the tremendous demands imposed by reactive species, multiple regulatory proteins have subverted redox active cysteines, heme, or metal cofactors to sense reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, and coordinate the transcription of antioxidant and antinitrosative defenses (Crack et al., 2012; Farhana et al., 2012; Spiro and D'Autreaux, 2012; Vazquez-Torres, 2012). Salmonella OxyR was the first sensor of oxidative stress to be identified (Christman et al., 1985). Elegant studies using E. coli OxyR established that the oxidation of Cys199 and Cys208 by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or nitrogen oxides activates the transcription of genes encoding antioxidant and antinitrosative defenses (Hausladen et al., 1996; Kullik et al., 1995). Since the discovery of OxyR in Salmonella, diverse saprophytic and pathogenic microorganisms have been shown to express thiol-based sensors of oxidative or nitrosative stress (Chen et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Paget et al., 2001). We recently discovered that Cys203 in the dimerization domain of the SsrB response regulator of Salmonella enterica senses reactive nitrogen species and plays a role in Salmonella pathogenesis (Husain et al., 2010). It is likely that, in addition to OxyR and SsrB, Salmonella expresses other thiol-based sensors to regulate specific transcriptional responses to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species encountered in the multiple niches occupied by this enteropathogen.

In addition to being exposed to oxidative and nitrosative stress, intracellular bacteria endure limitations in nutrients during the course of an infection. Nutritional deprivation in general, and amino acid shortages in particular, trigger an adaptation known as the stringent response (Potrykus and Cashel, 2008). The stringent response in starving organisms is characterized by repressed transcription of tRNA, rRNA, and ribosomal proteins, and the activation of amino acid biosynthesis genes. Exposure of Gram-negative and –positive bacteria to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species similarly results in the down-regulation of translational machinery (Bourret et al., 2008; Chi et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2013; Henard et al., 2010; Henard and Vazquez-Torres, 2012), suggesting that the stringent response must offer similar advantages to the metabolic challenges that arise from the oxidative inactivation of key enzymes of central metabolism. The coordinated and independent actions of the ppGpp alarmone and DksA regulatory protein on the RNA polymerase regulate the stringent response in starving bacteria (Paul et al., 2004; Perederina et al., 2004; Potrykus and Cashel, 2008). The mechanism by which reactive species trigger a down-regulation of translational machinery, however, has not yet been elucidated. DksA of E. coli or Salmonella contains 4 cysteines. Structural analysis of the E. coli DksA protein has revealed that the 4 cysteines form part of a zinc-finger motif strategically placed in the globular domain between a coiled-coil and an α-helix (Perederina et al., 2004). Because zinc fingers are excellent sensors of oxidative and nitrosative stress, we tested the hypothesis that the sulfhydryls coordinating the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif of DksA serve as a thiol switch able of repressing gene expression in response to biologically relevant reactive species.

RESULTS

Sensing of nitrosative stress by the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif

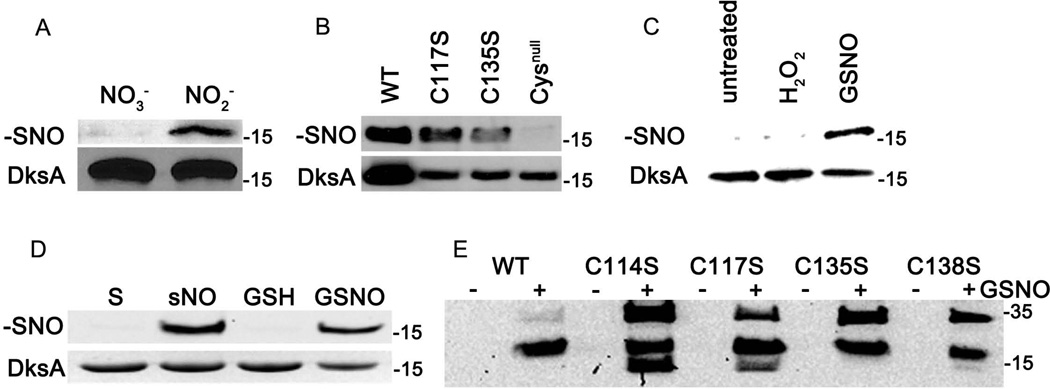

To test whether the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif is a sensor of reactive nitrogen species, a Salmonella strain expressing a 3×FLAG-tagged DksA protein was exposed to acidified nitrite (NO2−), a primary source of nitrosative stress in the gastric lumen and macrophages (Bourret et al., 2008; McCollister et al., 2007). S-nitrosylated cytoplasmic proteins were derivatized in a biotin-switch assay that distinguishes S-nitrosothiols from other oxidized or reduced thiol groups. The resulting biotinylated proteins were affinity-purified and the specimens were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blots specific for the 3 × FLAG tag revealed the S-nitrosylation of DksA in Salmonella cultures exposed to acidified NO2−, but not to acidified nitrate (NO3−) (Figure 1A). Our investigations demonstrate that thiols coordinating the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif are susceptible to biologically active nitrogen oxides generated from the acidification of NO2−.

Figure 1. Sensing of reactive nitrogen species by thiols in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif of DksA.

Salmonella strain AV08016 expressing the dksA∷3 × FLAG allele was grown for 6 h in EG medium, pH 5.5, in the presence of 750 µM NO3− or NO2−. S-nitrosothiols (−SNO) in cytoplasmic extracts were derivatized in the biotin switch assay. DksA∷3 × FLAG was detected in affinity-purified, biotinylated fractions (upper panel, A). The effect that reactive nitrogen species had on DksA content was measured in unfractionated bacterial cytoplasmic extracts (lower panel, A). S-nitrosylation of DksA was also studied in Salmonella strains expressing 3 dksA variants bearing mutations in 1 or all cysteines in the zinc-finger motif (B). The formation of S-nitrosylated DksA was also tested in Salmonella treated with 400 µM H2O2 or 500 µM S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) for 30 min (C). Salmonella grown in EG medium, pH 5.5, were used as controls (untreated). (D) 50 µM recombinant DksA protein was treated with 10 equivalents of the NO-donor spermine NONOate (sNO), or 2 equivalents of GSNO for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. Spermine (S) and glutathione (GSH) were used as controls. S-nitrosothiolated DksA derivatives were detected using the biotin switch assay (upper panel) and total recombinant DksA protein was visualized by Coomassie blue staining (lower panel). (E) S-nitrosylation of recombinant DksA variant expressing the wild-type or serine substitutions in the indicated cysteine residues. Where indicated (+), the specimens were treated with GSNO. The molecular weight markers (kDa) are shown on the right side of the immunoblots. The data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments.

A Salmonella strain expressing a DksA variant lacking all 4 cysteine residues showed a lack of S-nitrosylation of thiol groups in the zinc-finger motif (Figure 1B). On the other hand, Salmonella strains expressing the DksA C117S or C135S variants showed diminished levels of S-nitrosylation of DksA, possibly reflecting the lower concentrations of these DksA variants in the cytoplasm of Salmonella. We also tested whether DksA can be S-nitrosylated in bacteria treated with the transnitrosylating agent S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO). Treatment of Salmonella with 500 µM GSNO for 30 min resulted in the S-nitrosylation of DksA (Figure 1C). As expected, untreated or 400 µM H2O2-treated controls did not harbor S-nitrosylated DksA. Together, these findings indicate that DksA can be S-nitrosylated in vivo in response to various reactive nitrogen species encountered by Salmonella during their associations with the host. Given these results, we investigated the ability of biologically relevant reactive nitrogen species to S-nitrosylate affinity-purified, recombinant DksA protein in vitro. The recombinant, wild-type DksA protein was found to be S-nitrosylated upon treatment with the NO donor spermine NONOate or GSNO, but not with spermine or glutathione controls (Figure 1D). Because DksA cysteine variants are still S-nitrosylated in Salmonella treated with acidified NO2− (Figure 1B), we used this in vitro system to gain insights into the target cysteine residue of S-nitrosylation. Recombinant DksA proteins bearing mutations in single cysteines in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif were exposed to 500 µM GSNO for 30 min before processing in the biotin-switch assay. This analysis revealed that all DksA variants bearing single cysteine mutations were S-nitrosylated by GSNO (Figure 1E), suggesting that 2 or more of the cysteines in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif are reactive. In addition to the 17.2 kDa species corresponding to monomeric DksA, GSNO treatment of DksA cysteine mutants gave rise to S-nitrosylated species of different molecular weights (Figure 1E). The high molecular weight species likely reflects oligomers arising from oxidized cysteine residues in monomeric DksA. The nature of the S-nitrosylated species with a smaller molecular weight than monomeric DksA is currently unknown. Collectively, these findings indicate that thiols in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif of DksA can be S-nitrosylated in vivo and in vitro by a variety of reactive nitrogen species.

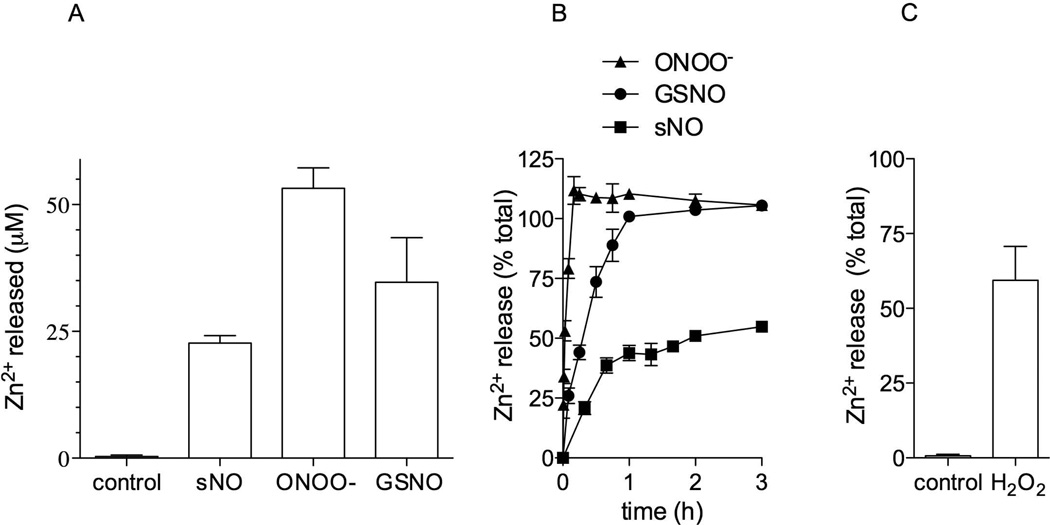

Oxidative and nitrosative stress releases the zinc cation from DksA

The zinc-finger motif in the globular domain of DksA is coordinated by the only 4 cysteines in the protein (Perederina et al., 2004), and thus S-nitrosylation of thiols forming the zinc-finger motif would be anticipated to destabilize metal binding. The chelator 4-(2-pyridylazo) resorcinol (PAR) (Hunt et al., 1985) was used to test whether reactive nitrogen species affect the binding of zinc by DksA. PAR was not observed to strip the zinc cation from wild-type DksA. Treatment of 50 µM DksA with 500 µM of the NO donor spermine NONOate resulted in the release of about 25 µM zinc (Figure 2A). The NO donor PROLI NONOate also released zinc from DksA (not shown), lending further support to the notion that the NO-dependent modification of thiols does indeed disassemble the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif. The strong oxidant peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and the transnitrosating agent GSNO also caused zinc release from DksA (Figure 2A). It appears, however, that not all reactive nitrogen species tested were as efficient at releasing the zinc from DksA. Therefore, we studied the kinetics by which these reactive nitrogen species strip the zinc cation from DksA. Nonlinear regression analysis of the concentration of zinc released over time indicated that ONOO−, GSNO, and spermine NONOate release zinc from DksA with estimated t1/2 of 2, 21, and 33 min, respectively (Figure 2B). Moreover, ONOO− and GSNO released 100% of the zinc, whereas spermine NONOate released about 50%. These data indicate that a variety of reactive nitrogen species cause the release of the metal cation from the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif, although with distinct kinetics. Taking into account the kinetics presented herein, it appears that DksA is a better sensor of ONOO− and S-nitrosothiols than NO. The addition of 500 µM H2O2 stripped about 50% of the zinc from 50 µM DksA (Figure 2C), suggesting that DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif can also sense reactive oxygen species.

Figure 2. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species release zinc from DksA.

The release of zinc from 50 µM DksA was measured by monitoring the complexation of Zn2+ with 150 mM 4-(2-pyridylazo) resorcinol 1 h after the protein was treated with 10 equivalents of spermine NONOate (sNO), S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), or peroxynitrite (ONOO−) at 37°C (A). Percent of zinc released from 50 µM DksA over time after treatment with 10 equivalents of the indicated reactive nitrogen species (B) or H2O2 (C). The data are the mean ± SEM from at least 2 separate experiments (n=4–6).

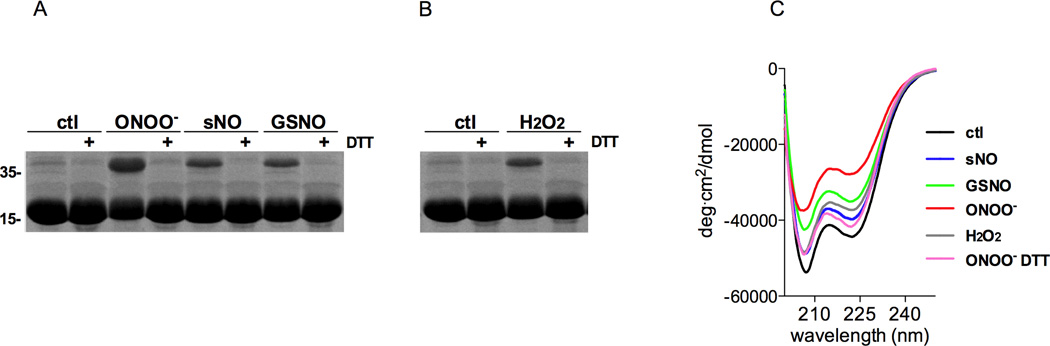

Thiol oxidation alters the secondary structure of DksA

The oxidation of the zinc fingers in the anti-sigma factor RsrA and the heat shock protein Hsp33 drives conformational and functional changes in these metalloproteins (Bae et al., 2004; Graumann et al., 2001). Consequently, the modifications of cysteines in the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif and the release of the metal cofactor noted in NO-treated specimens could induce conformational changes in this RNA polymerase regulatory protein. We first tested this hypothesis by measuring the migration of control and oxidized DksA in nonreducing, SDS-PAGE gels. ONOO−, and to a lesser extent spermine NONOate and GSNO, altered the migration patterns of DksA in SDS-PAGE gels (Figure 3A). The addition of DTT reversed the oligomeric species formed upon the oxidation of DksA. H2O2 also induced the formation of a DTT-reversible, oligomeric DksA species (Figure 3B). These findings suggest that reactive oxygen and nitrogen species induce disulfide bonds that are accompanied by changes in the secondary structure of DksA. To test this idea further, control and oxidized DksA proteins were studied by circular dichroism spectroscopy. All specimens were processed 1 h after treatment with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, because the oligomeric DksA species formed upon ONOO− treatment are stable for at least 1 h and because the amount of zinc released by GSNO, spermine NONOate and H2O2 reach the Vmax by 1 h. ONOO−, GSNO, and H2O2 each diminished the α-helical secondary structure of DksA as indicated by the loss of the 220 nm minimum (Figure 3C). Consistent with its superb ability to mediate zinc release and induce the reversible oxidation of DksA (Figure 2 and 3A), ONOO− triggered the most dramatic loss of α-helical content in DksA. The loss of α-helicity noted in ONOO−-treated DksA was reversed upon the addition of DTT (Figure 3C). Collectively, these investigations suggest that the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif behaves as a redox active thiol switch that can drive reversible changes in the secondary structure of DksA through disulfide bond formation.

Figure 3. Changes in DksA α-helicity following the reversible oxidation of cysteines in the zinc-finger motif.

50 µM DksA was treated for 1 h at 37°C in the dark with 10 equivalents of peroxynitrite (ONOO−), spermine NONOate (sNO), or S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) (A), or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (B). Reduced, zinc-bound DksA was used as control (ctl). Selected samples were co-incubated with 1 mM DTT. DksA was visualized by Coomassie blue staining after the samples were separated in non-reducing, SDS-PAGE gels. (C) CD spectra of untreated or ONOO−-, sNO-, GSNO-, or H2O2-treated DksA. Where indicated, 1 mM DTT was added to oxidized DksA 1 h after ONOO− treatment. Data on A and B are representative of 2–3 independent experiments. Panel C represents the mean of 6 independent scans.

LC-MS/MS peptide mapping of reduced and oxidized DksA

The ability of DTT to reverse the loss of secondary structure in oxidized DksA suggests that the cysteines in DksA can undergo reversible disulfide bonds. To test whether disulfide linkages are associated with these structural changes, reduced and oxidized DksA were examined by mass spectrometry. Reduced and ONOO−-treated DksA were first alkylated with iodoacetamide to selectively label free thiol groups. The protein samples were then reduced with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to break any existing disulfide bonds. The newly reduced cysteine residues were then alkylated with N-ethyl-malemeide (NEM). Differential modifications on individual cysteine residues were subsequently identified by LC-MS/MS. As shown in Table 1, all cysteine residues in DTT-treated DksA were found to be present as reduced thiols. In contrast, the cysteine residues in the ONOO−-treated DksA samples demonstrated considerable disulfide bonding. The raw spectral counts for the peptides containing the cysteine residues can be seen in Table S1. Bond formation preferentially involved Cys114 and Cys135, indicating an important role for these residues in the capacity of DksA to sense and respond to reactive species. Cys138 displayed a more modest involvement in disulfide bonding as compared to Cys114 and Cys135. Interestingly, Cys117 was very limited in its ability to participate in disulfide bond formation and was primarily observed to be terminally oxidized following ONOO− treatment. Cys114 and Cys117, as it is the case for Cys135 and Cys138, are contained within a single trypsin-digested DksA protein fragment. The LC-MS/MS analysis did not show any N-ethylmaleimide modifications in both Cys114 and Cys117 within single fragments, suggesting that these two residues do not form intramolecular disulfide bonds with each other. Similarly, only 12% of the fragments contained disulfide bonds between Cys135 and Cys138 in ONOO−-treated DksA. Surprisingly, tyrosine nitration, which is a frequent oxidative signature of ONOO−, was absent in ONOO−-treated DksA. However, methionine residues 32, 62, and 149 were oxidized to the corresponding sulfoxides. The raw spectral counts for the peptides containing the methionine residues can be seen in Table S1. Methionine oxidation is unlikely to account for DksA sensory function because reduction of sulfoxide derivatives requires enzymatic catalysis or harsh chemical treatment that is inconsistent with the ability of DTT to reverse the novel properties of oxidized DksA (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Oxidation status of cysteine residues in reduced and ONOO−-treated DksA

| DTT-treated | ONOO−-treated | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C114 | C117 | C135 | C138 | C114 | C117 | C135 | C138 | |

| Reduced1 | 100* | 100 | 99 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 6 | 18 |

| Disulfide-bonded2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 8 | 52 | 39 |

| Terminally-oxidized3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 92 | 42 | 43 |

% of cysteine residue modifications in all peptides measured

carbamidomethyl (+57 Da)

N-ethylmaleimide (+125 Da)

cysteic acid (+48 Da)

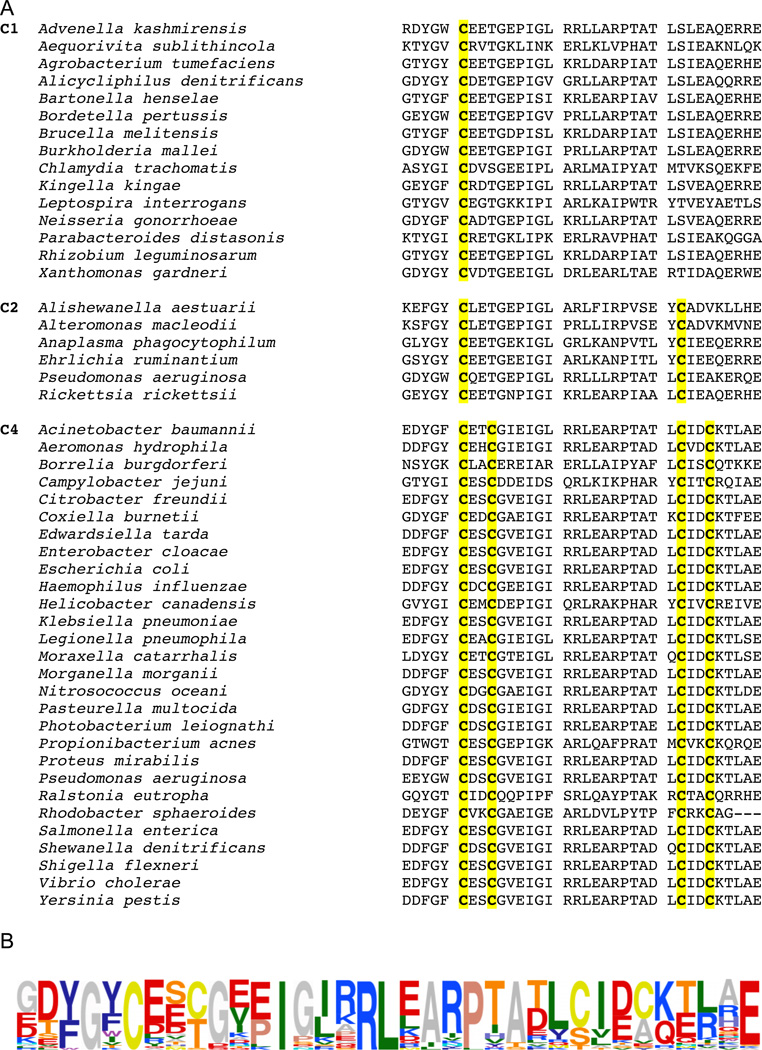

Cys114 is conserved in DksA of Gram-negative bacteria

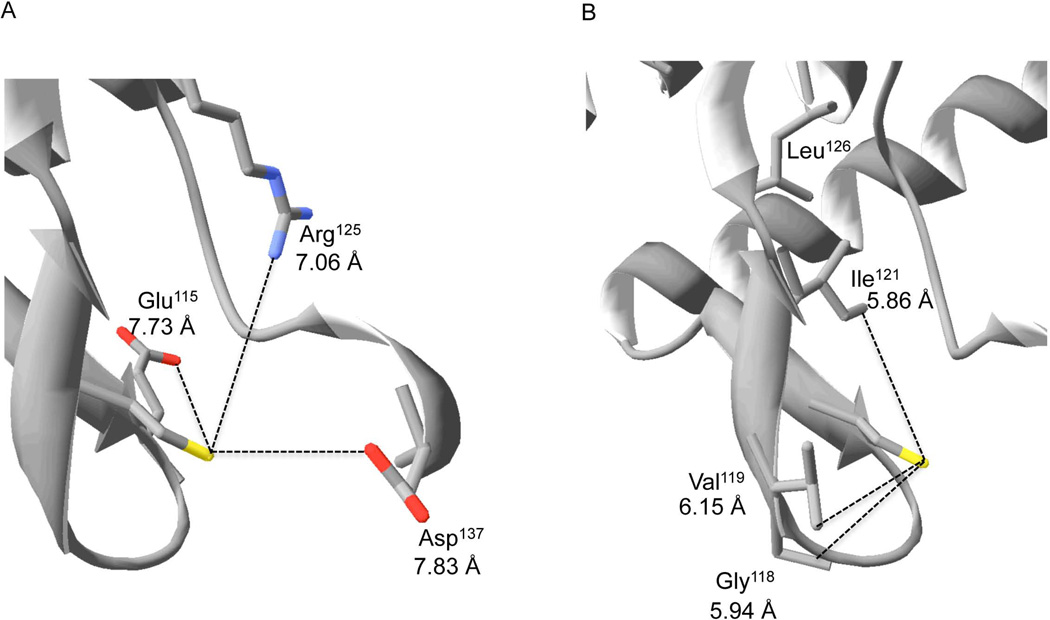

DksA is highly conserved among Gram-negative bacteria, suggesting that the ability of DksA to sense reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in Salmonella could be generalizable to other microorganisms. Orthologues of DksA express 1, 2 or 4 conserved cysteines. All known DksA proteins contain at minimum the cysteine at position 114 of the Salmonella DksA protein (Figure 4A). Analysis of the DksA consensus sequence shows considerable conservation of various charged and hydrophobic residues (Figure 4B) that are known to be critical for thiol-mediated sensing of reactive species (Vazquez-Torres, 2012). To determine the spatial localization of conserved hydrophobic and charged residues relative to Cys114, we performed an analysis of the crystal structure of E. coli DksA (Perederina et al., 2004) using Swiss-PDB Viewer v4.1.0 (Figure 5). This analysis revealed that the basic δ-guanido group of Arg125 is located 7.06 Å from the thiol group of Cys114, whereas the negatively charged carboxylic groups of Glu115 and Asp137 are 7.73 Å and 7.83 Å, respectively (Figure 5A). In addition, the conserved residues Ile121, Leu126, and Leu134 form a hydrophobic pocket flanking Cys114 (Figure 5B).

Figure 4. Amino acid sequence alignment of the C-terminal region of DksA homologs.

Selected annotated protein sequences obtained from the NCBI Protein database were aligned using Multalin (Corpet, 1988). Sequences are grouped according to their cysteine content; cysteine residues are highlighted in yellow. The DksA consensus sequence was determined using 74 protein sequences from NCBI, including those presented in panel A. The graphical representation of the consensus sequence was generated using Sequence Logo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990) and is displayed as amino acid frequency.

Figure 5. Charged and hydrophobic residues near Cys114.

Analysis of the crystal structure of E. coli DksA protein (Perederina et al., 2004) reveals the proximity of conserved positively- and negatively-charged (A) and hydrophobic residues (B) to the thiol group of Cys114.

Binding of oxidized DksA to the RNA polymerase

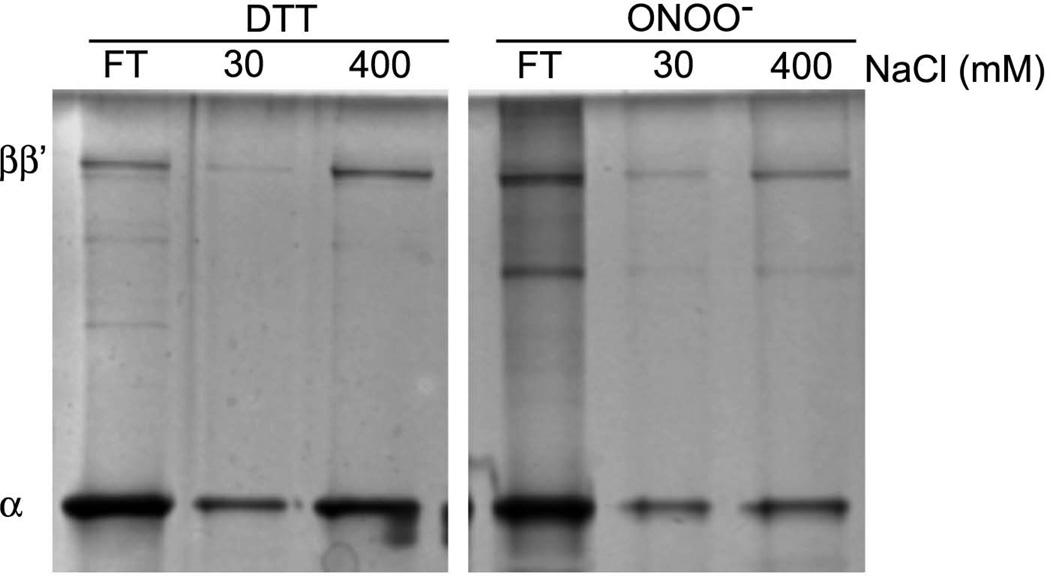

Next, we tested the effect that oxidation has on the binding of DksA to the RNA polymerase (Figure 6). Reduced and ONOO−-oxidized DksA immobilized in GSH Sephadex columns were incubated with core RNA polymerase. After 2 h of binding, the ββ’ and α subunits of the RNA polymerase were eluted from the GST-DksA with 400 mM NaCl. Densitometry of the ββ’ and α subunits of the RNA polymerase visualized by silver staining of specimens separated in SDS PAGE gels indicates that oxidized DksA binds about 60% of the RNA polymerase when compared to the reduced DksA protein. The lower binding of oxidized DksA may reflect the formation of oligomeric species (Figure 3A) unable to associate with the secondary channel of the RNA polymerase.

Figure 6. Binding of oxidized DksA to the RNA polymerase.

Binding of core RNA polymerase to GST-DksA proteins that had been treated with 1 mM DTT or 1 mM ONOO− before they were immobilized on a GSH Sepharose matrix. The gels show the α and ββ’ subunits of the RNA polymerase in the flow through (FT) or the fractions collected after the addition of NaCl. The proteins were visualized by silver staining of specimens separated in SDS-PAGE gels. The data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Oxidative stress enhances the DksA-dependent repression of gene transcription

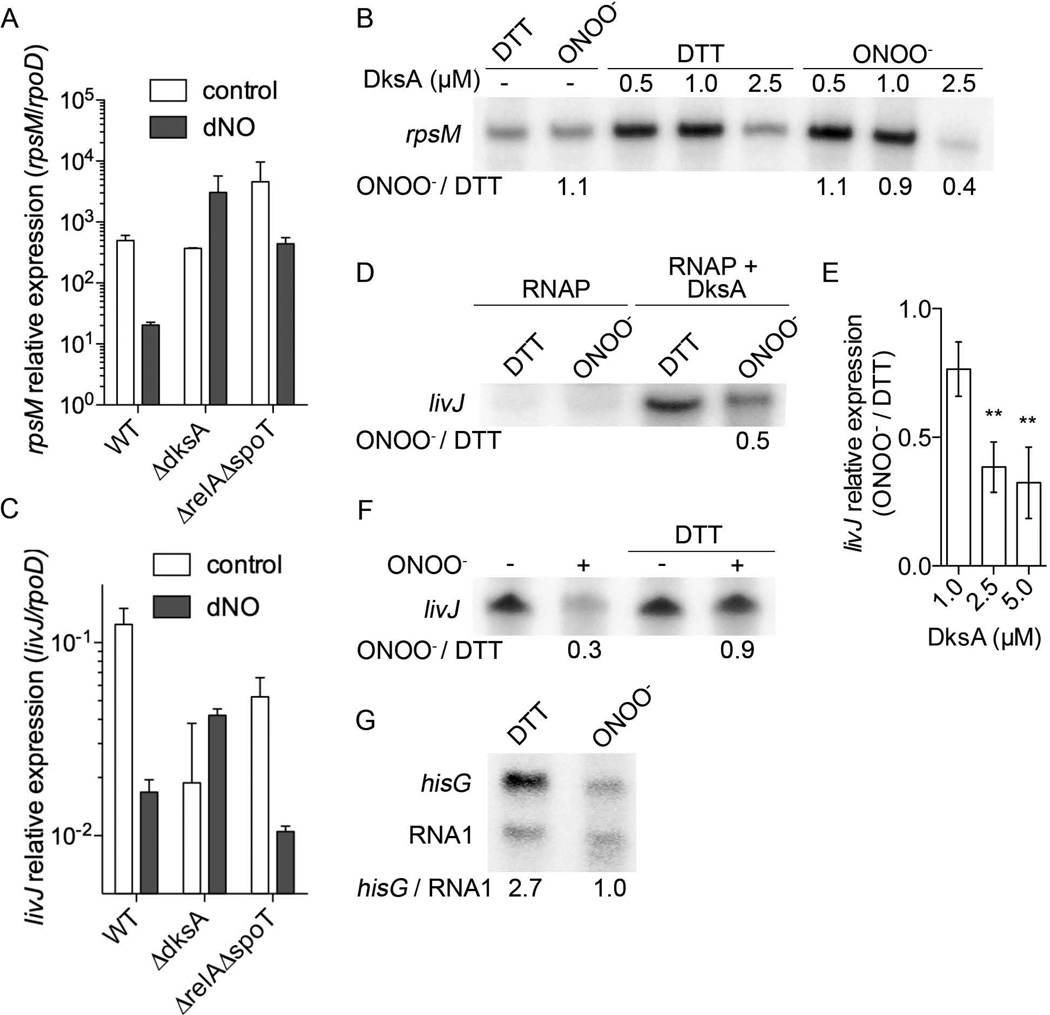

The considerable loss of α-helicity and the release of zinc seen in oxidized DksA could result in a change in the function of this RNA polymerase regulatory protein. We therefore tested whether the sensing of reactive nitrogen species by DksA has a direct effect on transcription. We measured the transcription of the ribosomal protein gene rpsM that is not only a direct target of DksA, but is also repressed in response to oxidative stress in a DksA-dependent manner (Henard et al., 2010). As previously noted for H2O2 (Henard et al., 2010), the transcription of the rpsM gene was repressed in rapidly growing Salmonella exposed to 5 µM NO generated by DETA NONOate (Figure 7A). NO also down-regulated rpsM expression in a relA spoT mutant, but did not repress the expression of this r-protein in dksA-deficient Salmonella. The rpsM transcript levels in wild-type and the dksA mutant were similar, and significantly lower than in the ppGpp0 isogenic control. These findings suggest that the down-regulation of rpsM transcription seen herein after treatment of Salmonella with low amounts of NO is independent of ppGpp.

Figure 7. DksA-dependent inhibition of gene transcription in response to reactive nitrogen species.

Relative expression of rpsM (A) and livJ (C) in control and DETA NONOate (dNO)-treated bacteria. Increasing concentrations of DksA complexed with 5 nM RNA polymerase were treated with 25 µM ONOO− before rpsM (B) and livJ (D) in vitro transcription reactions were initiated. The ratio of rpsM and livJ transcripts in oxidized over reduced samples (ONOO−/DTT) are shown at the bottom of the autoradiographs. 2.5 µM of DksA were used in the experiments shown in panel D. Increasing concentrations of DksA and 5 nM RNA polymerase were treated with 25 µM ONOO− before livJ in vitro transcription was initiated upon the addition of DNA template and reaction buffer (E). The results in E show the ratio of livJ transcription supported by the oxidized over the corresponding reduced specimens. * p < 0.01 when compared to the in vitro transcription reactions containing 1 µM DksA. 2.5 mM DTT was added to DksA/RNA polymerase complexes 5 min after treatment with 25 µM ONOO−; the transcription of livJ was initiated with the addition of the DNA template and reaction buffer (F). Effect of oxidation on the in vitro transcription of hisG and the internal standard RNA1 is shown in G. The ratio of hisG/RNA1 is shown below the autoradiograph. The results in A, C, and E are the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The data in B, D, F and G are representative of 2–3 independent experiments.

An in vitro transcription system was used to directly test whether DksA can repress rpsM in response to reactive nitrogen species. Unexpectedly, in vitro transcription of rpsM appeared to be stimulated in response to 0.5 and 1.0 µM DksA. However, as described for E. coli (Lemke et al., 2011), 2.5 µM DksA repressed rpsM in vitro transcription by ~3-fold (Figure 7B). Because of its fast kinetics and short half-life, ONOO− was chosen to test the effect that the oxidation of DksA has on rpsM in vitro transcription. Taking into account a binding constant of 100 nM (Lennon et al., 2009) and that over 90% of DksA should be bound to the RNA polymerase in the cell, we reasoned that the oxidation of DksA in vivo must take place in complex with the RNA polymerase. Therefore, we treated the RNA polymerase-DksA complex with 25 µM authentic ONOO−, a species with a half-life of 1.9 sec (Beckman et al., 1990). Of note, the addition of 25 µM ONOO− did not affect the transcription of rpsM supported by the RNA polymerase alone, indicating that the low concentrations of ONOO− used in these experiments do not have an appreciable effect on the enzymatic activity of the RNA polymerase. At 0.5 and 1 µM DksA concentrations, ONOO− did not significantly (p > 0.05) affect rpsM in vitro transcription (Figure 7B). However, as the concentration of DksA increased to 2.5 µM, ONOO− potentiated (p < 0.05) the inhibitory activity of reduced DksA by about 2-fold. These findings indicate that the oxidized DksA protein is a more potent repressor of rpsM than reduced DksA.

Because rpsM is repressed by DksA, we also measured the effect of oxidation on the transcription of livJ that is known to be directly activated by DksA (Paul et al., 2005). Salmonella strains deficient in dksA or relA spoT expressed lower concentrations of livJ than the isogenic wild-type control, which is consistent with the idea that the stringent response activates livJ transcription (Magnusson et al., 2007). As noted with rpsM, 2.5 mM DETA NONOate repressed livJ transcription in wild-type and relA spoT mutant Salmonella, but did not affect its expression in dksA isogenic bacteria (Figure 7C). These findings suggest that oxidized DksA represses or fails to activate livJ gene transcription independently of ppGpp. Accordingly, the level of livJ in vitro transcription was lower in the DksA/RNA polymerase specimens treated with 25 µM ONOO− (Figure 7D). The lack of activation of livJ noted after ONOO− treatment does not seem to be explained by the oxidation of the RNA polymerase because, in the absence of DksA, ONOO− did not repress the enzymatic activity sustained by the RNA polymerase alone (Figure 7D). Moreover, the inhibitory effects of ONOO− were dependent on the concentration of DksA. This is demonstrated by the fact that 1 and 5 µM of oxidized DksA diminished livJ transcription by 20% and 70%, respectively, as compared to the corresponding concentrations of reduced, zinc-bound DksA (Figure 7E). The addition of 2.5 mM DTT reversed the inhibition of livJ in vitro transcription observed with the ONOO−-treated DksA/RNA polymerase complex (Figure 7F), suggesting that the inhibitory effects exerted by the oxidized DksA protein are reversible. Oxidized DksA also inhibited the in vitro transcription of hisG, a gene that is activated by reduced DksA (Paul et al., 2005). In contrast, the internal RNA1 promoter that is directly transcribed by the RNA polymerase was not inhibited by oxidized DksA. Cumulatively, these investigations support the idea that DksA can behave as a novel thiol switch that inhibits target gene transcription upon oxidation of cysteines in the zinc-finger motif.

DISCUSSION

Salmonella undergoing nitrosative or oxidative stress down-regulate the transcription of ribosomal proteins, rRNA, and tRNA (Bourret et al., 2008; Henard et al., 2010). The investigations presented herein are consistent with a model by which sensing of reactive species by thiols in the 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif modulate the regulatory activity of the DksA protein in Salmonella experiencing oxidative or nitrosative stress. Analogous to the synergism exerted by ppGpp on the regulatory activity of DksA, our investigations indicate that oxidative and nitrosative stress can reversibly improve the inhibitory activity of the DksA protein. However, in contrast to the classical stringent response, DksA-dependent responses to oxidative stress are associated with the down-regulation of both translational machinery and amino acid metabolic gene transcription. Placing the expression of translational machinery and amino acid biosynthesis under the control of oxidized DksA may help bacteria quickly and reversibly adapt to the metabolic constraints associated with oxidative and nitrosative stress.

Zinc coordinating cysteines in the globular domain of DksA form a structural motif (Perederina et al., 2004) that is required for the DksA-dependent regulation of transcription of stringent response targets in nutritionally deprived bacteria. We found that, in addition to serving as a scaffold where a zinc-finger motif is assembled, the thiols of the only four cysteines of DksA respond to a variety of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These data are in keeping with the idea that thiolates coordinating zinc cations often serve as redox active sensors of oxidative and nitrosative stress (Ilbert et al., 2006), as this metal promotes cysteine reactivity by lowering the pKa of the coordinating thiolate groups. Interestingly, it is also possible that the zinc cation ameliorates the reactivity of DksA thiols. In this case, zinc would play an antioxidant role as previously described for the anti-sigma factor RsrA and PerR (Lee and Helmann, 2006a, b; Li et al., 2003). Hence, zinc coordination may limit the oxidation of DksA cysteines to situations in which oxidative stress imposes metabolic demands on the cell.

Cysteine residues are often used as redox sensors because they can adopt up to ten, often reversible, oxidation states that endow proteins with specific structural and functional properties. Our investigations have discovered that thiols in the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif can undergo a variety of covalent modifications upon exposure to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. For example, DksA becomes S-nitrosylated in Salmonella exposed to acidified NO2− or GSNO. S-nitrosylation of DksA could occur through the direct reaction of sulfenyl (−S•) and NO radicals, or through the transnitrosation of the nitrososonium cation (NO+) from low-molecular weight S-nitrosothiols, such as GSNO, to a thiolate group (−S−) in the zinc-finger motif of DksA (Vazquez-Torres, 2012). S-nitrosothiols can alter protein function by their own right, but are often intermediate species that promote stable disulfide bond formation with neighboring cysteines (Kim et al., 2002). As a matter of fact, the LC-MS/MS analysis of the ONOO−-treated protein demonstrates disulfide bonds are formed primarily among Cys114/Cys135 and, to a lesser extent, between Cys114/Cys138 and Cys135/Cys138. The oxidation of DksA thiols appears to promote changes in α-helicity and increase the ability of DksA to inhibit gene transcription. The novel regulatory effects of oxidized DksA are readily reversible upon reduction. Taken together, these observations support our proposed model that the DksA 4-cysteine zinc-finger motif is a thiol multiplex that provides DksA the capacity to rapidly integrate nutritional, oxidative, and nitrosative signals into a coordinated transcriptional response.

The conservation of Cys114 in the globular domain of DksA from phylogenetically diverse Gram-negative bacteria raises the intriguing possibility that all DksA variants described to date may sense oxidative and nitrosative stress, even though not all of them are capable of assembling a zinc-finger motif. In addition to Cys114, several nearby charged and hydrophobic residues are also highly conserved among all DksA orthologues. The proximity of conserved charged residues potentially lowers the pKa of Cys114, thus promoting the formation of a thiolate critical for reactivity with peroxides such as H2O2 or ONOO−. In fact, according to PROPKA 3.1 analysis (Rostkowski et al., 2011), the pKa of Salmonella DksA Cys114 is 5.45. Conserved hydrophobic residues may promote DksA reactivity by forcing the Cys114 thiolate group away from the protein’s core, thereby increasing its accessibility to reactive species. Importantly, in DksA proteins containing only Cys114, the cysteine residues at positions 117 and 135 are replaced with threonine or serine residues. The close proximity of these residues to Cys114, each less than 4 Å away, would allow stabilization of the thiolate through hydrogen bonding and further promote the reactivity of Cys114. Taken together, these determinants are markedly similar to those reported to influence thiolate formation in the redox-sensing transcriptional regulators OxyR and OhrR (Vazquez-Torres, 2012), and are consistent with a thiol-based sensory function for all known DksA protein variants. While the reactivity of DksA variants containing a single redox active cysteine residue would be expected to differ from those containing the more common C4 arrangement, each would be capable of dimer formation through disulfide bonding. In addition, all DksA variants could form mixed disulfides with low-molecular weight thiols such as glutathione, a modification known to regulate protein function (Antelmann and Helmann, 2011). Moreover, the C4 and C2 DksA variants could form intramolecular disulfide bonds as demonstrated for the C2 Pseudomonas aeruginosa DksA2 protein (Furman et al., 2013). Because all described DksA orthologues express one, two, or four conserved cysteines in their globular domain, phylogenetically diverse microorganisms could use this thiol switch as a mechanism for fine-tuning transcriptional regulation according to the metabolic restrictions imposed by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

Two non-mutually exclusive models may explain the DksA-dependent down-regulation of transcription noted in response to oxidative stress. First, the formation of DksA oligomers in the soluble monomeric pool in response to oxidative stress may limit the availability of this transcriptional regulator. As DksA is constitutively expressed (Paul et al., 2004), changes in the amount of monomeric protein available to bind to the RNA polymerase could be an important mechanism of regulation. Indeed, diminished association between DksA and RNA polymerase could account for the observed decrease in binding of RNA polymerase by oxidized DksA, as well as the apparent inhibition of livJ and hisG transcription noted in the reactions containing oxidized DksA. This model, however, does not easily explain why rpsM transcription, classically repressed by reduced DksA, is further down-regulated in response to increasing levels of oxidized, zinc-free DksA. It is therefore possible that monomeric, oxidized, zinc-free DksA could exert increased repressing activity on the RNA polymerase. In this second model, the regulatory effects seen upon oxidation of DksA could stem from the actual oxidation of cysteine thiols and/or the formation of a demetallated apoprotein.

The ability of relA spoT mutant Salmonella to down-regulate rpsM and livJ transcription in response to nitrosative stress argues that, under the experimental conditions tested here, oxidized DksA represses gene transcription independently of ppGpp. Distinct roles for ppGpp and DksA in regulating gene transcription in response to oxidative stress is also suggested by the observation that ppGppo dksA mutant Salmonella are even more hypersusceptible to the cytotoxicity of NO than isogenic strains lacking either relA spoT or dksA (Henard and Vazquez-Torres, 2012). Our findings are consistent with data reported by other investigators who have also suggested that DksA can mediate ppGpp-independent roles in gene regulation (Aberg et al., 2008; Aberg et al., 2009; Magnusson et al., 2007). These observations, however, do not preclude a role for ppGpp in the transcriptional response to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Specifically, reactive nitrogen species oxidize thiol groups and [Fe-S] clusters of IlvD dehydroxy-acid dehydratase, LpdA lipoamide-dependent lipoamide dehydrogenase, and MetE cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (Hondorp and Matthews, 2004; Hyduke et al., 2007; Richardson et al., 2011). The inhibition of amino acid biosynthesis and the expected depletion of charged tRNA could induce a surge in the intracytoplasmic ppGpp pool, thereby contributing to the down-regulation of translational machinery seen in bacterial cells undergoing oxidative and nitrosative stress. Separately, the cytoplasmic pool of the rRNA initiating nucleoside (usually an ATP or GTP) exerts feedback regulation on rRNA synthesis (Schneider et al., 2002). Thus, the diminution of ATP synthesis that follows the nitrosylation of terminal quinol cytochrome oxidases of the electron transport chain could also contribute to the down-regulation of translational machinery in NO-treated Salmonella (Bourret et al., 2008).

Our investigations indicate that cysteines holding the DksA zinc-finger motif behave as a thiol multiplex that integrates nutritional, oxidative, and nitrosative signals to repress gene transcription. The DksA-dependent regulation of stringent control in response to oxidative and nitrosative stress provides a rapid and reversible mechanism for fine-tuning the level of translational machinery in accord with nutritional shortages associated with the oxidation of redox active cysteines and metal cofactors of central metabolic enzymes. As all known DksA orthologues contain at least one conserved cysteine residue in the globular domain, phylogenetically diverse microorganisms could use this thiol-based sensor in the regulation of transcription according to the metabolic restrictions imposed by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial strains

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain ATCC 14028s and isogenic strains expressing several dksA variants are described in Table 2. To generate Salmonella strains carrying a wild-type or mutated dksA allele, a template plasmid was constructed by cloning an FRT-flanked chloramphenicol cassette from pKD3 into the BamHI and SacI restriction sites of pBluescript SK+ to generate pSK∷cm. The dksA open reading frame was cloned between EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites of pSK∷cm. dksA variants with cysteine to serine substitutions were generated by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and the mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were used as templates to generate amplicons with the dksA alleles and an FRT-flanked chloramphenicol resistance cassette. The addition of 60-base long primers containing homology to the dksA locus allowed for the recombination of the amplicons into the Salmonella chromosome using the λ Red recombinase system (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). The primers are listed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| S. Typhimurium ATCC 14028s | Wild-type | ATCC |

| AV08016 | dksA∷3×FLAG | (Henard et al., 2010) |

| AV10305 | dksA C135S∷3×FLAG | This study(Henard et al., 2010) |

| AV10310 | dksA C117S∷3×FLAG | This study |

| AV10311 | dksA C114S C117S C135S C138S∷3×FLAG | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSUB11 | 3×FLAG FRT ahp FRT bla R6KoriV | (Uzzau et al., 2001) |

| pGEX6P1 | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst | GE Healthcare |

| pGEX6P1∷dksA | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst dksA | This study |

| pGEX6P1∷dksAC114S | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst dksAC114S | This study |

| pGEX6P1∷dksAC117S | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst dksAC117S | This study |

| pGEX6P1∷dksAC135S | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst dksAC135S | This study |

| pGEX6P1∷dksAC138S | bla pBR322 ori lacIq Ptac gst dksAC138S | This study |

| pRLG4413 | PhisG (−60/+1) RNA1 | (Paul et al., 2005) |

Table 3.

Primers

| Mutation | Primer sequence |

| dksAC114S | F:TGGAAGATGAAGACTTCGGTTATAGCGAGTCCTGCG |

| R:CGCAGGACTCGCTATAACCGAAGTCTTCATCTTCCA | |

| dksAC117S | F:TATTGCGAGTCCAGCGGGGTGGAGATT |

| R:AATCTCCACCCCGCTGGACTCGCAATA | |

| dksAC135S | F:ACAGCCGATCTGAGCATCGACTGCAAAACGCTGGCT |

| R:AGCCAGCGTTTTGCAGTCGATGCTCAGATCGGCTGT | |

| dksAC138S | F:ACAGCCGATCTGTGCATCGACAGCAAAACGCTGGCT |

| R:AGCCAGCGTTTTGCTGTCGATGCACAGATCGGCTGT | |

| pGEX6P1∷dksA | F:AAGCGCGGATCCATGCAAGAAGGGCAAAACCG |

| R:GCCGGAATTCTTAACCCGCCATCTGTTTTTCG | |

| Real time PCR | Primer sequence |

| rpsM | F:AGTTGCCAAATTTGTCGTTG |

| R:TACGAGCGTTGGTCTTGGTA | |

| PROBE: 6-FAM-TGAAATCAGCATGAGCATCAAGCGCCTGAT-3BHQ-1 | |

| livJ | F:CGCAGGGCTGAAAACCCA |

| R: CACACGAATGCGCCGCTA | |

| PROBE: 6-FAM-TCAGCGGAAGGCTTACTGGTCAC-3BHQ-1 | |

| In vitro transcription | |

| livJ | F: GGAATTCCAATACGTTTGCCCGATGG |

| R: TGCACTGCAGTGCATATTTCACCGCGACGAGC | |

| rpsM | F: CGGAATTCCTGTCATCCGTGTGATTTGCAG |

| R: TGCAGCTAGCTGCATTTTCAGCGATACCCGCT | |

DksA purification

Genes encoding DksA variants were cloned into the BamHI-EcoRI restriction sites of pGEX6P1 (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Fairfield, CT) using the primers listed in Table 3. N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged DksA proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) at 25°C. Expression of GST-DksA was induced for 3 h by adding 0.2–0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside to cultures grown in LB broth to an OD600 of 0.5. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 50 mM Tris, pH 7, and lysed by sonication. Soluble DksA proteins were purified as GST-fusions, and the GST tag removed using PreScission protease (GE Healthcare Biosciences). DksA proteins were purified further at 4°C on a Superdex-75 size-exclusion FPLC column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0. Positive fractions were pooled and concentrated using Centricon filter devices.

Biotin switch assay

Salmonella were exposed to 750 µM NO2− or NO3− in EG medium (0.2 g/L MgSO4, 2 g/L C6H8O7-H2O, 10 g/L K2HPO4, 3.5 g/L Na(NH4)HPO4-4H2O, and 4 g/L D-glucose), pH 5.5. Some of the Salmonella cultures were exposed to 400 µM H2O2 or 500 µM GSNO for 30 min. The analysis of S-nitrosothiols in the DksA protein in Salmonella was done according to a modified method of the protocol originally described by Jaffrey and Snyder (Husain et al., 2010; Jaffrey and Snyder, 2001). Briefly, free thiols were blocked with four volumes of 250 mM Hepes, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine (HEN) buffer containing 20 mM methyl methanethiosulfonate and 2.5% (w/v) SDS at 50°C with occasional mixing. After 20 min, the cytoplasmic proteins were precipitated, and the pellets were washed with ice-cold acetone. The proteins were solubilized in 1% (w/v) SDS HEN buffer, and the nitrosothiols present in the samples were reduced with 1 mM ascorbate. The exposed thiol groups were derivatized with 16.66 mM biotin {N-[6-(Biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2’-pyridyldithio)-propionamide} (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. The proteins were then precipitated and washed with ice-cold acetone. The protein pellets were solubilized in 1% (w/v) SDS HEN buffer and mixed with two volumes of neutralization buffer [1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, 250 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.7]. NeutrAvidin-agarose resin (Thermo Scientific) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight. The resin was washed with high-salt neutralization buffer (1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 600 mM NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, 250 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.7), and the proteins were eluted after boiling the resin in 2× SDS sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol. The specimens were resolved on 12% (v/v) SDS/PAGE gels, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for the DksA∷3 × FLAG protein with the M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). To determine the S-nitrosylation of DksA in vitro, 50 µM of the DksA variants were treated with 500 µM spermine NONOate or 100 µM GSNO at 37°C. The nitrosating agents were removed after 1 h of culture using the Micro bio-spin P6 column (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Free thiols were blocked and S-nitrosothiols were derivatized as described above. S-nitrosylated DksA derivatives were resolved using 12% (v/v) SDS-PAGE gels, transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with an anti-biotin monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich).

Measurement of zinc release

50 µM recombinant protein was exposed to 500 µM spermine NONOate, 500 µM GSNO, 500 µM H2O2, or 500 µM ONOO−. GSNO and ONOO− were synthesized as previously described (Hart, 1985; Mohr et al., 1994). Free zinc was measured by the addition 150 mM of the metal chelator 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol (PAR) (Sigma-Aldrich). PAR-zinc chelates were measured spectrometrically at A500nm, and zinc concentration was calculated by regression analysis using known ZnCl2 standards.

Non-reducing, SDS-PAGE

50 µM recombinant protein was treated with 500 µM spermine NONOate, 500 µM GSNO, 500 µM H2O2, or 500 µM ONOO− for 1 h at 37°C. The specimens were then mixed with 3× Red loading buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) lacking reducing agents. 10 µL (~10 µg protein) of the samples were loaded into a 12% (v/v) SDS-PAGE gels and electrophoresed at 125V on ice. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Circular dichroism spectroscopy was performed on a Jasco-810 spectrometer with constant nitrogen flushing (Jasco, Easton, MD). Circular optical cells with a path length of 0.1 cm were used to determine the spectra of proteins in 50 mM Tris, pH 7 over a wavelength of 195–250 nm in 1 nm increments. Each spectrum is the average of four scans.

Binding of DksA to the RNA polymerase

The effect of oxidation on the binding of DksA with the RNA polymerase was assessed as described earlier with slight modifications (Paul et al., 2004). Briefly, 30 nmol GST-DksA were treated with 1 mM DTT or 1 mM ONOO− at 37°C for 1 h. Treatment of GST-DksA with ONOO− stripped all the zinc from the protein as determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the formation of zinc-PAR chelates at A500nm. DTT and ONOO− oxidation products were removed from the specimens using a Micro bio-spin P6 column. The samples were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with 1 ml of GSH Sepharose beads that had been prewashed with 40 bed volumes of 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0. DTT- and ONOO−-treated DksA proteins were retained in the GSH Sepharose matrix at similar concentrations. 40 pmol of RNA polymerase core (Epicentre, Madison, WI) were incubated at 4°C with the DksA immobilized in the columns. Two hours after incubation, the column was washed 4 times with 30 mM NaCl, and the RNA polymerase was eluted with 4 additional washes with 400 mM NaCl. Low salt and high salt eluates were combined separately. The proteins were precipitated with 15% TCA, separated by SDS PAGE, and the α and ββ’ subunits of the RNA polymerase eluted were visualized by silver staining.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Recombinant Salmonella DksA (75µM) was treated in the dark with 2 mM DTT for 60 min at room-temperature. DTT was removed using a Zebra desalt spin 25 column (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Rockford, Illinois). Selected samples of reduced DksA were treated with 10 molar equivalents of ONOO− for 60 min at 37°C. Unreacted ONOO− was removed using a Micro bio-spin P6 column and SDS was added to each sample at a final concentration of 0.05%. All samples were treated in the dark with 20 mM iodoacetamide for 60 min at 37°C. Following alkylation, the sample buffer was exchanged with 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate. Five micrograms of DksA in the specimens were resolved on 10% Bis-Tris PAGE gels, and were subjected to in gel digestion as described previously (Keene et al., 2009). Briefly, individual bands were excised from gel and treated with 5 mM TCEP for 15 min followed by alkylation with 20 mM NEM for 60 min and trypsin digestion. Peptides were extracted from gel pieces and analyzed on a hybrid Obritrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA) coupled to an Eksigent 2D LC system (Eksigent Technologies, Framingham, MA). Data was search for the presence of carbamidomethylated cysteine (+57 Da), NEM-alkylated cysteine (+125 Da), and cysteic acid oxidized cysteine (+48 Da).

Real Time RT-PCR

Bacteria grown overnight in LB broth were subcultured in EG medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 0.1% casamino acids, 10 µM FeCl3, and 2 µg/mL thiamine and grown in a shaker incubator to log phase (OD600 of 0.4). Selected samples were treated with 5 mM DETA NONOate for 30 min. After 30 min of culture, untreated controls had grown to an OD600 of ~0.77, whereas the DETA NONOate-treated specimens had grown to an OD600 of ~0.49. The cultures were mixed 1:5 (v/v) with ice-cold 5% phenol/95% ethanol and the specimens were placed on ice for 20 min for RNA stabilization. Isolation of bacterial RNA, synthesis of cDNA, and real-time RT-PCR for the rpsM-encoded ribosomal protein, the amino acid transporter livJ, and the rpoD housekeeping gene were performed as previously described (Henard et al., 2010). Briefly, the RNA was purified using the high pure RNA isolation kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN), and contaminating DNA was removed by performing treatment with Turbo DNase (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) followed by RNeasy clean-up (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). One microgram of total RNA from DETA NONOate-treated or untreated wild-type or dksA mutant cultures was used to generate cDNA in reactions that contained 100 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.45 µM N6 random hexamer primers (Life Technologies), and 20 U RNAsin Plus RNase inhibitor (Promega). Reverse transcription was performed for 1 h at 42°C. The cDNA was purified using the QIAGEN PCR purification kit as suggested by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The primers and probes used for the real-time RT-PCR are listed in Table 2. The results are expressed as relative expression over the rpoD house-keeping gene. Treatment of Salmonella with DETA NONOate did not result in any significant changes (p > 0.05) in rpoD mRNA expression.

In vitro transcription

Linear PCR products used for in vitro transcription spanned from −107 to +221, and −128 to +320 regions of the rpsM and livJ genes, respectively. The in vitro transcription vector pRLG4413 containing the hisG (−60/+1) promoter from E. coli and an internal RNA1 control was used at 1 nM in 10 µL of reaction buffer. RNA polymerase/DksA complexes were treated with 2.5 mM DTT or 25 µM ONOO− for 5 min at 37°C in buffer containing 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and 2 mM MgCl2 before they were added to the in vitro transcription reactions. The RNA polymerase was used at 5 nM, whereas DksA was used between 0.5 and 5 µM. Where indicated, DksA/RNA polymerase complexes were incubated with 2.5 mM DTT 5 min after ONOO− treatment. The in vitro transcription of the rpsM and livJ genes were performed at 37°C (final volume 10 µL) with 1 nM linear DNA, 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 60 mM potassium glutamate, 0.05% NP-40, 0.8 U/µL RNase inhibitor, 200 µM ATP, 200 µM GTP, 200 µM CTP, 10 µM UTP and 1 µCi α-32P UTP. The in vitro transcription of hisG and RNA1 were initiated by the addition of reaction buffer containing 40 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.9, 165 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 µg/µl BSA, 0.8 U/mL RNase inhibitor, 500 µM ATP, 200 µM CTP and GTP, 10 mM UTP and 1 mCi α-32P UTP. The reactions were carried out at 37°C for rpsM and livJ, and 30°C for hisG. After 10 min, the reactions were terminated with the addition of RNA loading buffer (95% formamide, 0.025% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 0.025% bromophenol blue), and heating at 70°C for 10 min. Transcripts were resolved by electrophoresis on 5% Bio-Rad TBE-Urea precasted gels, and their abundance quantified after processing in a phosphorimager.

Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. Determination of statistical significance between multiple comparisons was achieved using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-test using transformed data. Data were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI54959, AI039557 AI052237, AI073971, AI075093, AI077645 and AI083646, USDA grants 2009-03579 and 2011-67017-30127, the Veterans Administration grant IO1 BX002073, the T32 GM008730 and AI052066 Institutional Training grants, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund. We thank Dr. Brooke E. Hirsch for assistance with the CD spectroscopy, and Drs. T. Romeo and J. Jones-Carson, and Liam Fitzsimmons for comments on the manuscript. Plasmid pRLG4413 was provided by Dr. Richard Gourse.

Abbreviations

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- NO3−

nitrate

- NO

nitric oxide

- NO2−

nitrite

- NO+

nitrosonium cation

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- O2․−

superoxide anion

- PAR

4-(2-pyridylazo) resorcinol

- S−

thiolate

- S․

sulfenyl radical

Footnotes

The authors do not have a conflict of interest to declare.

Supplementary Table information:

Supplementary Table S1. Reduced and oxidized DksA spectra report.

REFERENCES

- Aberg A, Shingler V, Balsalobre C. Regulation of the fimB promoter: a case of differential regulation by ppGpp and DksA in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1223–1241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aberg A, Fernandez-Vazquez J, Cabrer-Panes JD, Sanchez A, Balsalobre C. Similar and divergent effects of ppGpp and DksA deficiencies on transcription in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3226–3236. doi: 10.1128/JB.01410-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelmann H, Helmann JD. Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1049–1063. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JB, Park JH, Hahn MY, Kim MS, Roe JH. Redox-dependent changes in RsrA, an anti-sigma factor in Streptomyces coelicolor: zinc release and disulfide bond formation. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourret TJ, Porwollik S, McClelland M, Zhao R, Greco T, Ischiropoulos H, Vazquez-Torres A. Nitric oxide antagonizes the acid tolerance response that protects Salmonella against innate gastric defenses. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes N, Rinck A, Leichert LI, Jakob U. Nitrosative stress treatment of E. coli targets distinct set of thiol-containing proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:901–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PR, Bae T, Williams WA, Duguid EM, Rice PA, Schneewind O, He C. An oxidation-sensing mechanism is used by the global regulator MgrA in Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:591–595. doi: 10.1038/nchembio820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BK, Gronau K, Mader U, Hessling B, Becher D, Antelmann H. S-bacillithiolation protects against hypochlorite stress in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by transcriptomics and redox proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009506. M111 009506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi BK, Roberts AA, Huyen TT, Basell K, Becher D, Albrecht D, Hamilton CJ, Antelmann H. S-bacillithiolation protects conserved and essential proteins against hypochlorite stress in firmicutes bacteria. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18:1273–1295. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman MF, Morgan RW, Jacobson FS, Ames BN. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack JC, Green J, Hutchings MI, Thomson AJ, Le Brun NE. Bacterial Iron-Sulfur Regulatory Proteins As Biological Sensor-Switches. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1215–1231. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang FC. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:820–832. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhana A, Saini V, Kumar A, Lancaster JR, Jr, Steyn AJ. Environmental Heme-Based Sensor Proteins: Implications for Understanding Bacterial Pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1232–1345. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman R, Biswas T, Danhart EM, Foster MP, Tsodikov OV, Artsimovitch I. DksA2, a zinc-independent structural analog of the transcription factor DksA. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann J, Lilie H, Tang X, Tucker KA, Hoffmann JH, Vijayalakshmi J, Saper M, Bardwell JC, Jakob U. Activation of the redox-regulated molecular chaperone Hsp33--a two-step mechanism. Structure. 2001;9:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TW. Some observations concerning the S-nitroso and S-phenylsulphonyl derivatives of L-cysteine and glutathione. Tetrahedron Letters. 1985;26:2013–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hausladen A, Privalle CT, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Stamler JS. Nitrosative stress: activation of the transcription factor OxyR. Cell. 1996;86:719–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henard CA, Bourret TJ, Song M, Vazquez-Torres A. Control of redox balance by the stringent response regulatory protein promotes antioxidant defenses of Salmonella. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36785–36793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henard CA, Vazquez-Torres A. DksA-dependent resistance of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium against the antimicrobial activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1373–1380. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondorp ER, Matthews RG. Oxidative stress inactivates cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (MetE) in Escherichia coli. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt JB, Neece SH, Ginsburg A. The use of 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol in studies of zinc release from Escherichia coli aspartate transcarbamoylase. Anal Biochem. 1985;146:150–157. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, Jones-Carson J, Song M, McCollister BD, Bourret TJ, Vazquez-Torres A. Redox sensor SsrB Cys203 enhances Salmonella fitness against nitric oxide generated in the host immune response to oral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14396–14401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005299107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyduke DR, Jarboe LR, Tran LM, Chou KJ, Liao JC. Integrated network analysis identifies nitric oxide response networks and dihydroxyacid dehydratase as a crucial target in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8484–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610888104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilbert M, Graf PC, Jakob U. Zinc center as redox switch--new function for an old motif. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:835–846. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA, Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988;240:1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. The biotin switch method for the detection of S-nitrosylated proteins. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:pl1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.86.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene SD, Greco TM, Parastatidis I, Lee SH, Hughes EG, Balice-Gordon RJ, Speicher DW, Ischiropoulos H. Mass spectrometric and computational analysis of cytokine-induced alterations in the astrocyte secretome. Proteomics. 2009;9:768–782. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyer K, Imlay JA. Inactivation of dehydratase [4Fe-4S] clusters and disruption of iron homeostasis upon cell exposure to peroxynitrite. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27652–27659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SO, Merchant K, Nudelman R, Beyer WF, Jr, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Hausladen A, Stamler JS. OxyR: a molecular code for redox-related signaling. Cell. 2002;109:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullik I, Stevens J, Toledano MB, Storz G. Mutational analysis of the redox-sensitive transcriptional regulator OxyR: regions important for DNA binding and multimerization. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1285–1291. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1285-1291.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CF, Mashino T, Fridovich I. α, β-Dihydroxyisovalerate dehydratase. A superoxide-sensitive enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4724–4727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Helmann JD. The PerR transcription factor senses H2O2 by metal-catalysed histidine oxidation. Nature. 2006a;440:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature04537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Helmann JD. Biochemical characterization of the structural Zn2+ site in the Bacillus subtilis peroxide sensor PerR. J Biol Chem. 2006b;281:23567–23578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Soonsanga S, Helmann JD. A complex thiolate switch regulates the Bacillus subtilis organic peroxide sensor OhrR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8743–8748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702081104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke JJ, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Burgos HL, Hedberg G, Ross W, Gourse RL. Direct regulation of Escherichia coli ribosomal protein promoters by the transcription factors ppGpp and DksA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5712–5717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019383108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon CW, Gaal T, Ross W, Gourse RL. Escherichia coli DksA binds to Free RNA polymerase with higher affinity than to RNA polymerase in an open complex. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5854–5858. doi: 10.1128/JB.00621-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Bottrill AR, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Paget MS, Kleanthous C. The Role of zinc in the disulphide stress-regulated anti-sigma factor RsrA from Streptomyces coelicolor. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson LU, Gummesson B, Joksimovic P, Farewell A, Nystrom T. Identical, independent, and opposing roles of ppGpp and DksA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5193–5202. doi: 10.1128/JB.00330-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni P, Vazquez-Torres A, Fang FC, Xu Y, Khan S, Hormaeche CE, Dougan G. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. II. Effects on microbial proliferation and host survival in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:237–248. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollister BD, Myers JT, Jones-Carson J, Husain M, Bourret TJ, Vazquez-Torres A. N2O3 enhances the nitrosative potential of IFNγ-primed macrophages in response to Salmonella. Immunobiology. 2007;212:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner KR, Imlay JA. The identification of primary sites of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide formation in the aerobic respiratory chain and sulfite reductase complex of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10119–10128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr S, Stamler JS, Brune B. Mechanism of covalent modification of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase at its active site thiol by nitric oxide, peroxynitrite and related nitrosating agents. FEBS Lett. 1994;348:223–227. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody CS, Hassan HM. Mutagenicity of oxygen free radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2855–2859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paget MS, Bae JB, Hahn MY, Li W, Kleanthous C, Roe JH, Buttner MJ. Mutational analysis of RsrA, a zinc-binding anti-sigma factor with a thiol-disulphide redox switch. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1036–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul BJ, Barker MM, Ross W, Schneider DA, Webb C, Foster JW, Gourse RL. DksA: a critical component of the transcription initiation machinery that potentiates the regulation of rRNA promoters by ppGpp and the initiating NTP. Cell. 2004;118:311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul BJ, Berkmen MB, Gourse RL. DksA potentiates direct activation of amino acid promoters by ppGpp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7823–7828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501170102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perederina A, Svetlov V, Vassylyeva MN, Tahirov TH, Yokoyama S, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG. Regulation through the secondary channel--structural framework for ppGpp-DksA synergism during transcription. Cell. 2004;118:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AR, Soliven KC, Castor ME, Barnes PD, Libby SJ, Fang FC. The Base Excision Repair system of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium counteracts DNA damage by host nitric oxide. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000451. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AR, Payne EC, Younger N, Karlinsey JE, Thomas VC, Becker LA, Navarre WW, Castor ME, Libby SJ, Fang FC. Multiple targets of nitric oxide in the tricarboxylic acid cycle of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostkowski M, Olsson MH, Sondergaard CR, Jensen JH. Graphical analysis of pH-dependent properties of proteins predicted using PROPKA. BMC Struct Biol. 2011;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider DA, Gaal T, Gourse RL. NTP-sensing by rRNA promoters in Escherichia coli is direct. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8602–8607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132285199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaver LC, Imlay JA. Are respiratory enzymes the primary sources of intracellular hydrogen peroxide? J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48742–48750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro S, D'Autreaux B. Non-Heme Iron Sensors of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1264–1276. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzzau S, Figueroa-Bossi N, Rubino S, Bossi L. Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15264–15269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261348198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Mastroeni P, Ischiropoulos H, Fang FC. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J Exp Med. 2000;192:227–236. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A. Redox Active Thiol Sensors of Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17:1201–1214. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.