Abstract

Objective

To investigate the effects of TLR4 antagonism on human endothelial cells activation and cytokine expression, and whether the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with better endothelial function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), OxPAPC, and free fatty acids (FFA) at baseline and after incubation with the TLR4 antagonist eritoran (E5564). Cytokine expression was assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. In vivo endothelial function was assessed as brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) in RA patients with the wild type gene (aa) and with the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphic variant (ag).

Results

In HAEC, TLR4 antagonism with eritoran inhibited LPS-induced mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, CCL-2, VCAM and ICAM (P<0.05 for all) and inhibited Ox-PAPC-induced mRNA expression of IL-8 (P<0.05) and IL-6, albeit not to a statistically significant level (p = 0.07). In contrast, eritoran did not affect FFA-induced mRNA expression of IL-6 (P>0.05). In 30 patients with RA (15 with the ag allele) undergoing measurement of FMD, no differences in FMD and plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM, and ICAM were found between the aa and the ag phenotype (P>0.05 for all).

Conclusions

TLR4 signaling in endothelial cells may be triggered by LPS and oxidized phospholipids, leading to endothelial activation and inflammation, which are inhibited by eritoran. Our in vivo investigation, however, does not support an association between the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism and improved endothelium-dependent vasodilator function in patients with RA. Further study is needed to better understand the potential role of TLR4 on endothelial dysfunction in this and other patient populations.

Introduction

Chronic inflammation represents a pivotal mechanism in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [1]. Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that innate immunity may also contribute to the development of vascular damage by interacting with inflammatory pathways [2]. In particular, toll-like receptors (TLRs) are increasingly being recognized as a link between the innate immune system, inflammation, and atherogenesis. This family of innate immune receptors is expressed by endothelial cells, in which they trigger various signaling pathways and lead to cell activation, increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, and endothelial dysfunction [3], [4]. While initially identified as sensors of microbial invasion, TLRs are now known to be activated also by endogenous ligands produced in inflamed tissues, potentially leading to further inflammation and perpetuating an inflammatory milieu [3]. Among them, TLR4, a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram negative bacterial cell walls, also exhibits affinity for fatty acids [5], extracellular matrix components, fibrinogen, and various heat shock proteins [6]. Of note, TRL4 signaling leads to activation of NF-κB [4], a pathway associated with andothelial injury [7], and TRL4 expression is increased in human atherosclerotic plaques [8]. Additionally, lack of TLR4 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in apoE-deficient mice fed a high-cholesterol diet [9]. In agreement with these data, clinical evidence indicates that the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism, a functional variant in the TLR4 gene (896A→G) that attenuates receptor signaling and diminishes the inflammatory response to LPS [10], is associated with decreased atherosclerotic risk [11]. However, whether antagonism of TLR4 prevents TLR4-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in human macrovascular endothelial cells has not been investigated in detail.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of the most prevalent systemic autoimmune diseases [12] and is associated with endothelial dysfunction [13] and increased cardiovascular risk [14]. This risk is attributed to the presence of both traditional and non-traditional risk factors, including inflammation and immunologic abnormalities [15]. A growing body of knowledge indicates that TLR4 may play a relevant role of in the pathogenesis of autoimmune damage in RA [3]. In line with this evidence, the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with decreased RA disease susceptibility and lower baseline disease activity [16]. However, whether the presence of the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with better endothelial function compared with the wild type genotype in patients with RA has not been studied.

The current investigations were therefore designed to test the following hypotheses: 1) antagonism of TLR4 with eritoran (E5564) inhibits the expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in human endothelial cells; and 2) the presence of the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with better endothelium-dependent vasodilation compared with the wild type genotype in patients with RA.

Materials and Methods

In-Vitro Experiments: Cell Culture and Treatment

Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All experiments were performed using HAECs between the 2th and the 5th passage. HAECs were treated with: LPS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 100 ng/mL for 6 hours; ox-PAPC (oxidation products of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine, Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands), an antigenic epitope of oxidized LDL, at a concentration of 100 µg/mL for 6 hours; or long chain free fatty acids (FFA, oleic acid 500 µM+palmitic acid 500 µM) for 24 hours. Cells were incubated with 10 nM eritoran for 30 minutes prior to treatments where indicated. Eritoran (Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ) is a synthetic analog of lipid A and a potent and specific antagonist of LPS action, which inhibits lipid A binding to MD2 and terminates MD2/TLR4-mediated signaling [17]. At the end of treatments, HAECs where collected and used for molecular analysis.

In-Vitro Experiments: Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from HAECs using Trizol reagents (Invitrogen Corp, Eugene, OR). A total of 2 µg of RNA was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Fifty nanograms of cDNA was amplified by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using an ABI PRISM 7500 System and TaqMan reagents (Applied Biosystems) and normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA as an endogenous control. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and the relative gene copy number was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt as previously described [18].

In-Vitro Experiments: Western Blots

Total protein was isolated from HAECs and western blots were performed as previously described [19]. The following antibodies were used: anti-P65, anti-phosphoSer536 P65, anti-IκBα, and anti-phosphoSer32/36 IκBα, (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA).

Clinical Study: Study Population

Nonsmoker patients with a diagnosis of RA according to the ACR revised criteria [20] and age- and sex-matched healthy controls were enrolled in the study. None of the patients had history or presence of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular disease, vasculitis, or any other systemic condition. All RA patients were on chronic treatment with either disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), monoclonal antibodies, or their combination. When used, aspirin, coxibs or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were withdrawn at least one week before the study; patients were allowed to use acetaminophen (paracetamol) or tramadol as needed. The Disease Activity Score 44 (DAS 44) was calculated for each patient. This score assesses disease activity by including tender and swollen joint count and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The level of disease activity can be interpreted as low (DAS≤2.4), moderate (2.4<DAS≤3.7), or high (DAS>3.7) [21]. A DAS<1.6 corresponds with being in remission according to the American Rheumatism Association (ARA) criteria [22]. The study protocol was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Tor Vergata University, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Clinical Study: Laboratory Methods

EDTA-collected blood samples were drawn on the study day after an overnight fast, immediately centrifuged for 15 min at 1000×g and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Detection of autoantibodies

Rheumatoid factor (RF)-IgM and RF-IgA (Orgentec Diagnostika GmbH, Mainz, Germany) and anti-CCP antibodies (Axis Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK) were measured using commercially available ELISA kits Equal volumes for each sample were loaded according to each specific kit’s instructions. The suggested cut-off levels were 20 U/mL for RF-IgM and RF-IgA and 5 U/mL for anti-CCP antibodies. Soluble biomarkers: plasma levels of IL-6, IL-8, ICAM, VCAM and MCP-1 were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Equal volumes for each sample were loaded according to each specific kit’s instructions. Quantitative levels of cytokines were determined by comparison with standard curves and reported as picograms or nanograms per mL (pg/mL or ng/mL). The sensitivity of the test was of 0.7 pg/mL for IL-6, 1.5 pg/mL for IL-8, 0.1 ng/mL for ICAM, 0.6 ng/mL for VCAM and 5.0 pg/mL for MCP-1. Genomic DNA for TLR4 genotyping was prepared from frozen whole blood with the use of a blood DNA isolation kit (Genomic Prep, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Subsequent allele-specific PCR amplification for the TLR4 allele Asp299Gly was performed according to a previously described protocol [23].

Clinical Study: Endothelial Function Testing

Assessment of endothelial function was conducted in the fasting state using a standardized ultrasound procedure [24]. Brachial artery reactivity, a test of endothelium-dependent vasodilation, was assessed as previously reported [25]. Briefly, participants lay supine on a bed and were allowed to rest for at least 10 minutes. During the rest period, participants were connected to a continuous ECG monitor and a pressure cuff was applied around the upper forearm. The left brachial artery was then visualized on the anterior aspect of the arm, 2–15 cm proximal to the antecubital fossa, using a Logiq E ultrasound machine (GE Healthcare Italia, Milan, Italy) with a high-resolution probe (12-MHz linear array transducer). After baseline images and flow measurements were obtained, the pressure cuff applied on the forearm was inflated at 250 mmHg for 5 minutes. Blood flow was measured during the first 15 seconds after cuff deflation, and arterial image acquisition for diameter measurements was performed between 60 and 90 seconds after cuff deflation. Arterial diameter was measured from the anterior to the posterior interface between the lumen and the endothelium at end diastole, incident with the R wave on the ECG. Images were analyzed by an investigator, different from the sonographer, blinded to image sequence and clinical data of study participants.

Statistical Analysis

For the clinical study, sample size calculation was based on differences between the values of FMD in the three groups. Using a 2-sided paired t test, a sample of 12 subjects in each group was calculated to be necessary to detect a 2% difference in FMD with 80% power and α<0.05. With anticipation of up to 3 (i.e. 20%) technically inadequate vascular studies, 15 participants per group were enrolled to yield 12 evaluable participants in each group. All group data are reported as mean ± SD. Group differences were analyzed by one way ANOVA, Fisher exact test, and unpaired Student t test, as appropriate. All calculated p values are two-tailed, and a value of p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software.

Results

In-Vitro Experiments: Eritoran Inhibits LPS-Induced mRNA Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines in HAECs

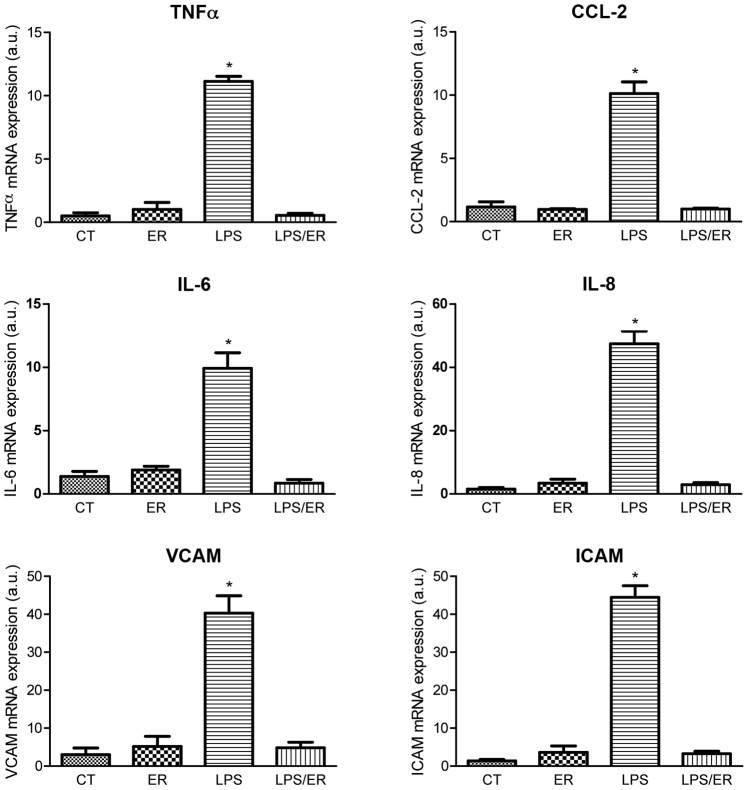

To determine the effects of TLR4 receptor antagonism on LPS-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines in HAECs, we assessed mRNA levels of IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and CCL-2 mRNA after treatment with LPS, alone and following pretreatment with eritoran for 30 minutes. Incubation with eritoran did not lead to significant changes in mRNA levels of these cytokines compared to control. Treatment with LPS alone for 6 hours induced a significant increase in cytokine expression. In contrast, when HAECs were treated with LPS following pretreatment with eritoran, cytokine mRNA levels were similar to control (figure 1, top and middle panels).

Figure 1. Effects of eritoran on LPS-induced mRNA expression (arbitrary units) of TNFα (top left panel), CCL-2 (top right panel), IL-6 (middle left panel), IL-8 (middle right panel), VCAM (bottom left panel), and ICAM (bottom right panel).

Values reported as mean±SD (n = 5 per group). CT: control; ER: eritoran; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; ER/LPS: eritoran/lipopolysaccharide. *p<0.05 vs CT, ER, and LPS/ER.

In-Vitro Experiments: Eritoran Inhibits LPS-Induced mRNA Expression of Adhesion Molecules in HAECs

To assess whether TLR4 receptor antagonism impacts LPS-induced expression of adhesion molecules in HAECs, we measured mRNA levels of VCAM and ICAM after treatment with LPS, alone and following pretreatment with eritoran for 30 minutes. compared with control, eritoran alone did not lead to significant changes in VCAM and ICAM mRNA levels. Treatment with LPS alone for 6 hours caused a significant increase in mRNA levels of the adhesion molecules. In contrast, when HAEC were treated with LPS following pretreatment with eritoran, mRNA levels of VCAM and ICAM were similar to control (figure 1, bottom panels).

In-Vitro Experiments: Eritoran Inhibits ox-PAPC-Induced mRNA Expression of IL-8 in HAECs

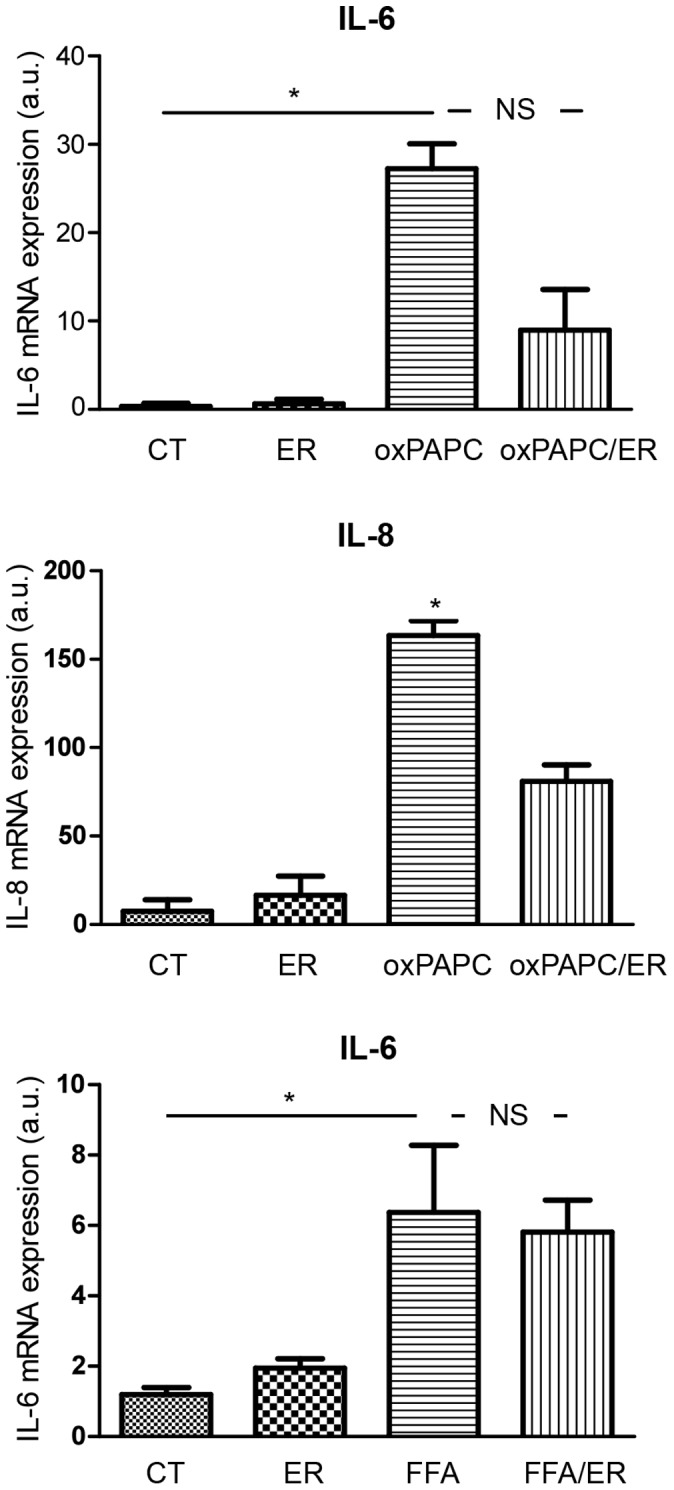

To explore the effects of TLR4 receptor antagonism on ox-PAPC-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines in HAECs, we assessed the effects of ox-PAPC treatment on mRNA levels of IL-6 and IL-8, alone and following pretreatment with eritoran for 30 minutes. Eritoran did not affect cytokine mRNA levels compared with control. ox-PAPC alone for 6 hours significantly increased cytokine mRNA levels. In contrast, when ox-PAPC treatment followed pretreatment with eritoran, mRNA levels of IL-8 were significantly reduced when compared with ox-PAPC alone (figure 2, top panel). Similarly, mRNA levels of IL-6 were reduced; however, they failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.07) (figure 2, middle panel).

Figure 2. Effects of eritoran on OxPAPC-induced mRNA expression (arbitrary units) of IL-6 (top panel) and IL-8 (middle panel) and on FFA-induced mRNA expression (arbitrary units) of IL-6 (bottom panel).

Values reported as mean±SD (n = 5 per group). CT: control; ER: eritoran; OxPAPC: oxidation products of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine; FFA: free fatty acids; OxPAPC/ER: oxidation products of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphatidylcholine/eritoran. Top panel: *p<0.05 vs CT and ER; NS: p = 0.07 vs OxPAPC/ER. Middle panel: *p<0.05 vs CT, ER, and OxPAPC/ER. Bottom panel: *p<0.05 vs CT and ER; NS: p>0.05 vs FFA/ER.

In-Vitro Experiments: Eritoran Does Not Affect FFA-Induced mRNA Expression of IL-6 in HAECs

To confirm that eritoran’s effects on inflammatory cytokines are mediated by TLR4, we assessed the effects of FFA treatment on mRNA levels of IL-6, alone and after incubation with eritoran for 30 minutes. As in the previous experiments, eritoran did not affect IL-6 mRNA levels compared with control. FFA alone for 6 hours led to significantly increased IL-6 mRNA levels. Consistent with our hypothesis that eritoran’s effects on inflammatory cytokines are mediated by TLR4, pre-treatment with eritoran did not affect FFA-induced inflammatory cytokine expression (figure 2, bottom panel).

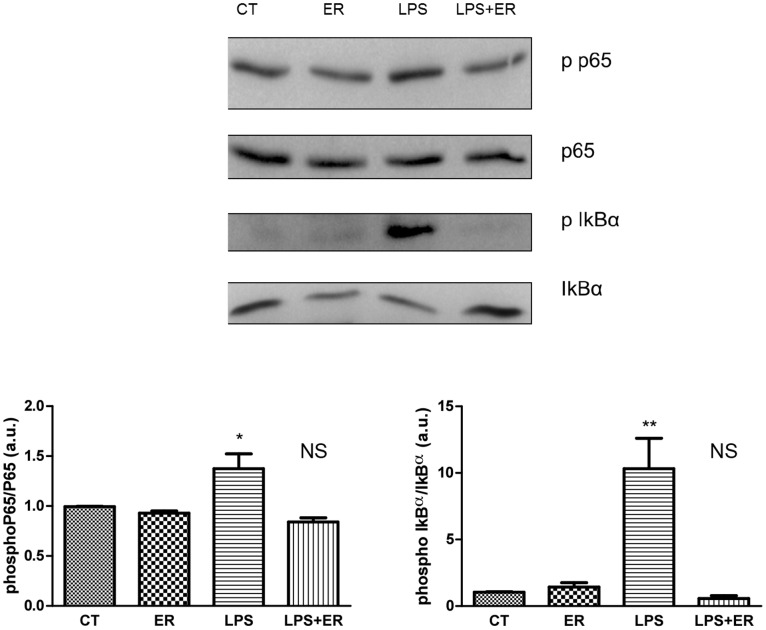

In-Vitro Experiments: Eritoran Reduces LPS-Induced Phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 Subunit and IκB-α in HAECs

To confirm that the effects of TLR4 antagonism on the expression of inflammatory cytokines are mediated by a modulation of the NF-κB pathways, we assessed phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and of IκB-α by western blotting (figure 3, top panel). Compared with control, treatment with eritoran for 30 minutes did not induce phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and of IκB-α. In contrast, treatment of HAECs with LPS for 6 hours caused an increase in the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and IκB-α. Pretreatment with eritoran prevented the LPS-induced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit (figure 3, bottom left panel) and IκB-α (figure 3, bottom right panel).

Figure 3. Representative Western blots (top panel) and bar graphs showing the effect of eritoran on LPS-induced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit (bottom left panel) and IκB-α (bottom right panel) (n = 5 per group).

Bottom left panel: *p<0.05 vs CT; NS: p>0.05 vs LPS/ER. Bottom right panel: **p<0.005 vs CT; NS: p>0.05 vs LPS/ER.

Clinical Study: Study Population

Thirty patients and 15 age- and sex-matched healthy controls took part in the study. Their baseline clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. The mean DAS 44 score of all the patients was 2.2 (range: 0.5–3.9). The majority of the patients were treated with a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (27/30) and/or a biologic agent (19/30). No significant differences were observed in these parameters, disease activity, and drug treatment between the two patient groups (all P>0.05).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Parameter | TLR4 Alleles | P | ||

| Control | AA (Wild type) | AG (Asp299Gly) | ||

| Participants per group (number) | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Sex (women/men) | 10/5 | 12/3 | 10/5 | 0.71* |

| Age (years) | 54±4 | 47±12 | 50±14 | 0.22# |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.0±4.3 | 26.3±4.8 | 27.0±2.7 | 0.40# |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/mL) | 94±10 | 94±36 | 105±28 | 0.44# |

| Disease duration (Years) | N/A | 8.0±7.8 | 6.1±9.4 | 0.56 |

| Disease Activity Score (DAS 44) | N/A | 2.08±0.93 | 1.84±0.74 | 0.43 |

| DMARD (yes/no) | N/A | 13/2 | 14/1 | 0.54 |

| Anti-CCP antibodies level (U/mL) | N/A | 93.0±192.8 | 42.1±41.0 | 0.33 |

| Rheumatoid Factor – IgM level (IU/mL) | N/A | 69.7±130.0 | 59.6±67.0 | 0.79 |

| Rheumatoid Factor – IgA level (IU/mL) | N/A | 26.6±49.4 | 30.9±41.5 | 0.80 |

| ESR (mm/h) | N/A | 19±17 | 40±76 | 0.31 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | N/A | 4.7±4.1 | 3.8±2.8 | 0.51 |

DMARD: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; anti-CCP: anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate. hsCRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein; BMI: body mass index.

*p value calculated using Fisher exact test and #p value calculated using one way ANOVA; all other p values calculated using unpaired t test.

Values are reported as mean ± SD unless specified otherwise.

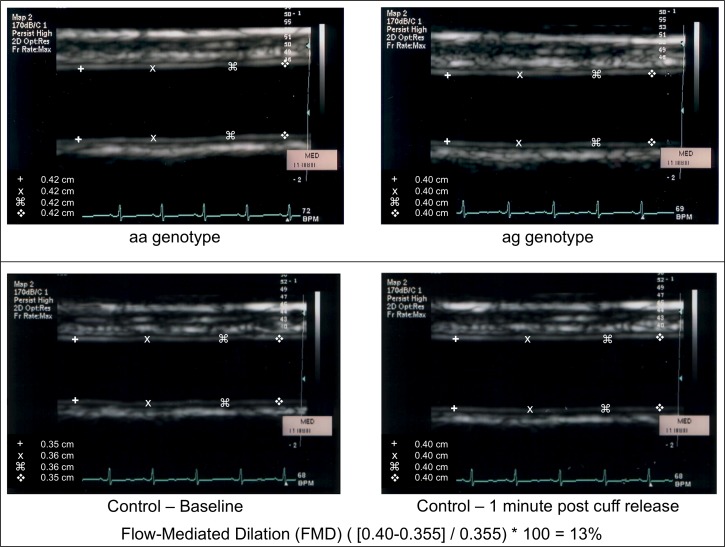

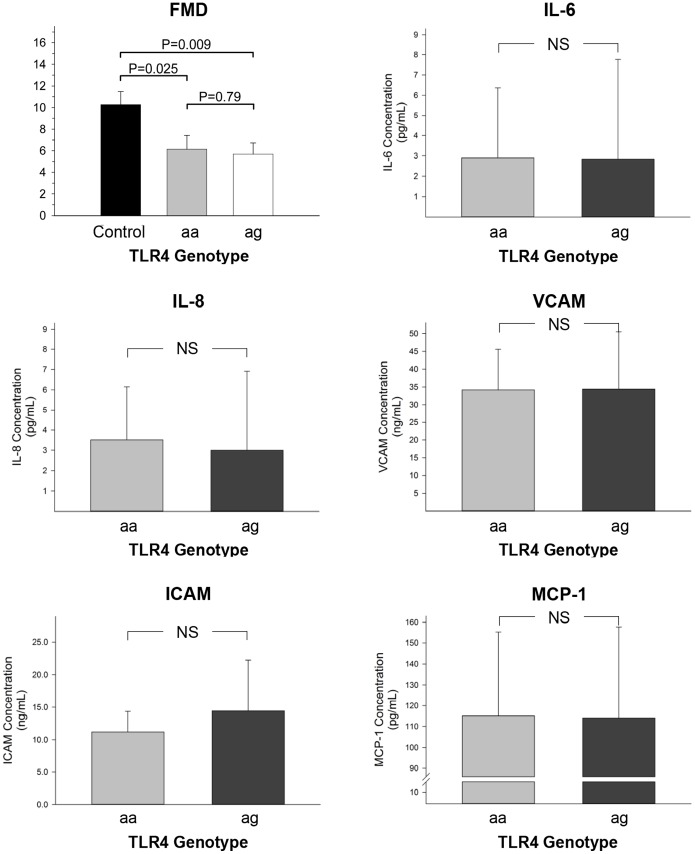

Clinical Study: Brachial Artery Reactivity

Baseline brachial artery diameter was similar in the three groups (3.7±0.6 mm, 3.3±0.5 mm, and 3.4±0.7 mm in the control, aa, and ag group, respectively, p = 0.18). Flow-mediated dilation was significantly higher in the controls compared to the RA groups (p = 0.014). However, no significant differences in FMD were observed between the two patient groups (p>0.05) (figure 4 and figure 5, top left panel).

Figure 4. Representative images of the baseline brachial ultrasound of a participant with the aa genotype (top left picture), of a participant with the ag genotype (top right picture), and of the baseline and post-hyperemic ultrasound of a healthy control (bottom pictures).

The calculation of flow-mediated dilation (FMD) using the values collected in the healthy control is also reported.

Figure 5. Flow-mediated dilation (top left panel) and plasma levels of IL-6 (top right panel), IL-8 (middle left panel), VCAM (middle right panel), ICAM (bottom left panel), and MCP-1 (bottom right panel) according to TLR4 genotype in study participants.

Values reported as mean±SD.

Clinical Study: Plasma Cytokines and Adhesion Molecules in RA Patients

Plasma levels of IL-6 and IL-8, of MCP-1, and of VCAM and ICAM were similar between the aa and ag groups (figure 5).

Discussion

The main results of our in-vitro investigations are that, in HAEC, TLR4 antagonism with eritoran: 1) inhibits LPS-induced mRNA expression of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, and CCL-2, and of the adhesion molecules VCAM and ICAM; 2) inhibits ox-PAPC-induced mRNA expression of IL-8 and of IL-6, albeit to a borderline significant level; and 3) reduces LPS-induced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and IκB-α. These findings indicate that TLR4 induces activation of human macrovascular endothelial cells through NF-κB-dependent pathways, leading to the expression of genes regulating the production of inflammatory mediators and adhesion molecules. Importantly, TLR4-dependent activation of these pathways is not restricted to exogenous ligands such as LPS, as mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL-8 was also triggered by Ox-PAPC. These phospholipid oxidation products are present in sites of chronic inflammation, in apoptotic cell membranes, and in oxidized LDL [26], suggesting a potential pathophysiologic role of Ox-PAPC-dependent LTR4 activation in atherosclerosis. Finally, as FFA-induced IL-6 expression was not affected by eritoran, our data suggest that TLR4 activation in macrovascular endothelial cells is possibly restricted to specific lipid ligands such as Ox-PAPC.

Our results are in agreement with the recent findings from Lu and colleagues. These authors reported that, in HAEC and in dermal microvascular endothelial cells, LPS induced an increase in mRNA expression and synthesis of IL-6, as well as a more robust gene expression of IL-8 and other inflammatory cytokines, ICAM, VCAM, chemokines, growth factors, and adhesion molecules [27]. Our study shows that also Ox-PAPC, an endogenous byproduct of phospholipid peroxidation, triggers TLR4-dependent expression of inflammatory mediators, confirming and further expanding previous observations [28]. In addition, we also confirm previous evidence that the synthesis of inflammatory mediators induced by TLR4 signaling is mediated by activation of NF-κB [4], which has been associated with endothelial injury [7]. Our in vitro findings complement the current understanding of the role of TLR4 signaling in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction proposed by Liang and colleagues. [29] In a series of elegant ex-vivo experiments using vessels from type 2 diabetic mice with mutated TLR4 (TLR4−/−), these investigators demonstrated that TLR4 activation leads to the transcription of NADPH oxidase 1 and 4 and increased reactive oxidative species (ROS) generation. In turn, the higher concentration of ROS impairs eNOS coupling, thereby reducing nitric oxide (NO) production; blunts endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated vasodilation; and increases the synthesis of vasoconstrictor prostanoids by cyclooxygenase 1. Thus, activation of TLR4 in macrovascular endothelial cells appears to trigger an inflammatory and proatherosclerotic phenotype, with enhanced expression of cytokines and adhesion molecules, increased ROS production, and abnormal synthesis of vasoactive factors. Conversely, in our study, TRL4 blockade by eritoran significantly inhibited LPS-stimulated expression of inflammatory and adhesion molecules in macrovascular endothelial cell cultures. In the same setting, TRL4 signaling inhibition was also effective in blunting IL-8 responses to Ox-PAPC treatment. These findings are in keeping with previous observations of mitigated inflammatory responses to LPS in endothelial cells pretreated by TRL4-blocking antibodies [27]. Even more importantly, our results are consistent with the recent evidence that TLR4 antagonism may inhibit vascular inflammation and atherogenesis in diabetic ApoE−/− mice, supporting the concept that TLR4 pathway is a potential therapeutic target [30].

The principal findings of our clinical study are that well-treated RA patients, despite low disease activity, have impaired brachial artery FMD and that the presence of the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is not associated with better endothelial function or lower plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and MCP-1. Of note, MCP-1 and its associated protein MCPIP are increased in experimental models of RA and exert detrimental effects on endothelial function by decreasing NO bioavailability [31]. Therefore, our investigation does not confirm the hypothesis that the Asp299Gly polymorphism, which has been reported to decrease TLR4 signaling activity [10], is associated with better vasodilator function compared to the wild type in this population. These results are apparently at odds with our and other groups’ laboratory data that suggest LTR4-mediated endothelial activation and dysfunction, and are not consistent with the evidence that the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with a decreased risk of atherosclerosis [11]. A number of factors may account for our negative results. The impact of the Asp299Gly variant on the endothelium may be modest and minor differences in endothelial function may have been missed due to small sample size and high variability of FMD. Alternatively, it is possible that the effects of this polymorphism on endothelial function are negligible in patients with RA, in whom other inflammatory stimuli may represent the main players in the pathogenesis of endothelial damage and atherosclerosis [32]. In this regard, it must be considered that patients with RA recruited for our study were receiving optimal medical treatment and had normal DAS 44 scores and low levels of inflammatory markers. It might be postulated, therefore, that it was difficult under those conditions to detect possible differences in endothelial activation and vasodilator function related to polymorphisms of the TRL4 gene. However, our results are in line with other studies that did not find a significant association between TLR4 Asp299Gly polymorphism and risk for development and progression of atherosclerosis, including a recently published meta-analysis [33]–[34].

In conclusion, the results of our in vitro study indicate that TLR4 signaling in endothelial cells may be triggered by both LPS and endogenous ligands, such as oxidized phospholipids, leading to endothelial cell activation and a proinflammatory phenotype. Importantly, TLR4 activation by endogenous ligands is likely to occur in the presence of a proatherosclerotic milieu, where it can contribute to maintain and amplify endothelial activation and vessel wall inflammation. Further investigations are needed to better understand the potential impact of TLR4 polymorphisms on endothelial function in this and other populations at onset of the disease and while on high disease activity. Certainly the findings of our in vivo investigation do not suggest that the Asp299Gly TLR4 polymorphism is associated with improved endothelial function in patients with RA, while treated and in low disease activity.

Acknowledgments

Eritoran (E5564) was kindly provided by EISAI Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ.

Funding Statement

This work as supported by an intramural grant of Tor Vergata University to Dr. Menghini. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. The New England journal of medicine 340: 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michelsen KS, Doherty TM, Shah PK, Arditi M (2004) TLR signaling: an emerging bridge from innate immunity to atherogenesis. Journal of immunology 173: 5901–5907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O’Neill LA (2008) Primer: Toll-like receptor signaling pathways–what do rheumatologists need to know? Nature clinical practice Rheumatology 4: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dauphinee SM, Karsan A (2006) Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 86: 9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, et al. (2006) TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation 116: 3015–3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vabulas RM, Ahmad-Nejad P, da Costa C, Miethke T, Kirschning CJ, et al. (2001) Endocytosed HSP60s use toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 to activate the toll/interleukin-1 receptor signaling pathway in innate immune cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 276: 31332–31339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun R, Zhu Z, Su Q, Li T, Song Q (2012) Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in bacterial endotoxin-induced endothelial cell injury and SOC-mediated calcium regulation. Cell biology international 36: 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu XH, Shah PK, Faure E, Equils O, Thomas L, et al. (2001) Toll-like receptor-4 is expressed by macrophages in murine and human lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaques and upregulated by oxidized LDL. Circulation 104: 3103–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Michelsen KS, Wong MH, Shah PK, Zhang W, Yano J, et al. (2004) Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101: 10679–10684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC, Zabner J, Kline JN, et al. (2000) TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nature genetics 25: 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kiechl S, Lorenz E, Reindl M, Wiedermann CJ, Oberhollenzer F, et al. (2002) Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and atherogenesis. The New England journal of medicine 347: 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW (2010) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 376: 1094–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murdaca G, Colombo BM, Cagnati P, Gulli R, Spano F, et al. (2012) Endothelial dysfunction in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Atherosclerosis 224: 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Ballman KV, Roger VL, et al. (2005) Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis and rheumatism 52: 402–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollan I, Meroni PL, Ahearn JM, Cohen Tervaert JW, Curran S, et al.. (2013) Cardiovascular disease in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Autoimmunity reviews. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Radstake TR, Franke B, Hanssen S, Netea MG, Welsing P, et al. (2004) The Toll-like receptor 4 Asp299Gly functional variant is associated with decreased rheumatoid arthritis disease susceptibility but does not influence disease severity and/or outcome. Arthritis and rheumatism 50: 999–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barochia A, Solomon S, Cui X, Natanson C, Eichacker PQ (2011) Eritoran tetrasodium (E5564) treatment for sepsis: review of preclinical and clinical studies. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 7: 479–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menghini R, Menini S, Amoruso R, Fiorentino L, Casagrande V, et al.. (2009) Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 deficiency causes hepatic steatosis and adipose tissue inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology 136: 663–672 e664. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Casagrande V, Menghini R, Menini S, Marino A, Marchetti V, et al. (2012) Overexpression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 in macrophages reduces atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, et al. (2010) 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis and rheumatism 62: 2569–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Gestel AM, Prevoo ML, van ‘t Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, et al. (1996) Development and validation of the European League Against Rheumatism response criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Comparison with the preliminary American College of Rheumatology and the World Health Organization/International League Against Rheumatism Criteria. Arthritis and rheumatism 39: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prevoo ML, van Gestel AM, van THMA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, et al. (1996) Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. British journal of rheumatology 35: 1101–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lorenz E, Frees KL, Schwartz DA (2001) Determination of the TLR4 genotype using allele-specific PCR. BioTechniques 31: 22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, Celermajer D, Charbonneau F, et al. (2002) Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rizza S, Cardellini M, Porzio O, Pecchioli C, Savo A, et al. (2011) Pioglitazone improves endothelial and adipose tissue dysfunction in pre-diabetic CAD subjects. Atherosclerosis 215: 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen L, Liang B, Froese DE, Liu S, Wong JT, et al. (1997) Oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein in normal and hyperlipidemic patients: effect of lysophosphatidylcholine composition on vascular relaxation. Journal of lipid research 38: 546–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lu Z, Li Y, Jin J, Zhang X, Lopes-Virella MF, et al. (2012) Toll-like receptor 4 activation in microvascular endothelial cells triggers a robust inflammatory response and cross talk with mononuclear cells via interleukin-6. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1696–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dvoracek LA, Kreisberg JI, McKinney J, Schmid G, Francis AD, et al. (2010) Lovastatin inhibits oxidized L-A-phosphatidylcholine B-arachidonoyl-gamma-palmitoyl (ox-PAPC)-stimulated interleukin-8 mRNA and protein synthesis in human aortic endothelial cells by depleting stores of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Atherosclerosis 208: 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liang CF, Liu JT, Wang Y, Xu A, Vanhoutte PM (2013) Toll-like receptor 4 mutation protects obese mice against endothelial dysfunction by decreasing NADPH oxidase isoforms 1 and 4. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lu Z, Zhang X, Li Y, Jin J, Huang Y (2013) TLR4 antagonist reduces early-stage atherosclerosis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Endocrinol 216: 61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. He M, Liang X, He L, Wen W, Zhao S, et al. (2013) Endothelial dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1-induced protein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Protogerou AD, Zampeli E, Fragiadaki K, Stamatelopoulos K, Papamichael C, et al. (2011) A pilot study of endothelial dysfunction and aortic stiffness after interleukin-6 receptor inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis 219: 734–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Netea MG, Hijmans A, van Wissen S, Smilde TJ, Trip MD, et al. (2004) Toll-like receptor-4 Asp299Gly polymorphism does not influence progression of atherosclerosis in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Eur J Clin Invest 34: 94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang K, Zhang L, Zhou B, Wang Y, Song Y, et al. (2012) Lack of association between TLR4 Asp299Gly polymorphism and atherosclerosis: evidence from meta-analysis. Thrombosis research 130: e203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]