Abstract

Objective

To compare interstage cardiac catheterization hemodynamic and angiographic findings between shunt types for Single Ventricle Reconstruction (SVR) trial.

Background

The SVR trial, which randomized subjects to modified Blalock-Taussig shunt (MBTS) or right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt (RVPAS) for the Norwood procedure, demonstrated RVPAS was associated with smaller pulmonary artery diameter, but superior 12-month transplant-free survival.

Methods

We analyzed pre-stage II catheterization data for SVR trial subjects. Hemodynamic variables and shunt and pulmonary angiography were compared between shunt types; their association with 12-month transplant-free survival was also evaluated.

Results

Of 549 randomized subjects, 389 underwent pre-stage II catheterization. Smaller size, lower aortic and superior vena cava saturation, and higher ventricular end-diastolic pressure (EDP) were associated with worse 12-month transplant-free survival. MBTS subjects had lower coronary perfusion pressure (27mmHg vs. 32mmHg, P<0.001) and higher Qp:Qs ratio (1.1 vs. 1.0, P=0.009). Higher Qp:Qs ratio increased the risk of death or transplant only in the RVPAS group (P=0.01). MBTS subjects had fewer shunt (14% vs. 28%, P=0.004) and severe left pulmonary artery stenoses (0.7% vs. 9.2%, P=0.003), larger mid-main branch pulmonary artery diameters and higher Nakata index (164 vs. 134, P<0.001).

Conclusions

Compared with RVPAS subjects, MBTS subjects had more hemodynamic abnormalities related to shunt physiology, while RVPAS subjects had more shunt or pulmonary obstruction of a severe degree, and inferior pulmonary artery growth at pre-stage II catheterization. Lower BSA, higher ventricular EDP, and lower SVC saturation were associated with worse 12-month transplant-free survival.

Introduction

Despite significant advances in staged surgical repair for infants with single ventricle anatomy, early and intermediate-term outcomes remain suboptimal(1, 2). The palliative approach for these infants consists of a Norwood procedure using either a modified Blalock-Taussig shunt (MBTS) or right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt (RVPAS) to supply blood flow to the lungs. Then, usually between 3 to 7 months of age, a stage II procedure is performed, most often after an elective pre-stage II cardiac catheterization with angiography of the shunt and pulmonary arteries. Few data exist regarding the importance of the pre-stage II assessment by cardiac catheterization and the importance of these findings to outcome(3, 4).

Recently, several non-randomized studies reported improved early outcomes following Norwood procedures using a RVPAS(5–7). The Pediatric Heart Network Single Ventricle Reconstruction (SVR) trial was a multi-institutional trial that evaluated early and intermediate-term outcomes for infants undergoing a Norwood procedure randomized to either MBTS or RVPAS. The initial SVR trial results(8) demonstrated that the RVPAS, compared with MBTS, was associated with superior 12-month transplant-free survival, although beyond 12 months there was no significant transplant-free survival difference between groups. However, this primary SVR analysis also demonstrated that RVPAS subjects underwent significantly more unintended cardiovascular procedures. In addition, analysis of the pre-stage II angiograms for pulmonary artery growth, a secondary endpoint of the SVR trial, demonstrated worse branch pulmonary artery growth prior to the stage II procedure for the RVPAS group compared with the MBTS group(8), but the level of detail of the angiographic analysis was limited. Hemodynamic measures were not analyzed in the initial SVR publication.

The purposes of this analysis were to describe in detail cardiovascular hemodynamics as well as shunt or branch pulmonary artery angiographic findings at pre-stage II cardiac catheterization; to assess differences in these measures by actual shunt type; and to evaluate the impact of these factors on 12-month transplant-free survival.

Methods

Study population and design

Between May 2005 and July 2008, 15 North American centers randomized 549 single ventricle infants in the SVR trial to MBTS or RVPAS. Randomization was stratified by aortic atresia (presence or absence) and obstructed pulmonary venous return (presence or absence), with dynamic allocation by the surgeon. Details regarding the trial design have been previously published(9). The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all participating institutions, and informed consent was obtained from each subject’s parent or guardian.

All subjects enrolled in the SVR trial who underwent a pre-stage II cardiac catheterization were included in these analyses. Infants who died prior to undergoing the stage II procedure, but had undergone cardiac catheterization and had acceptable angiography, were also included in the analyses. The only subjects excluded were those who did not undergo cardiac catheterization with angiography of the shunt and pulmonary arteries prior to the stage II procedure, or those who survived but never underwent stage II palliation. Subjects for whom the angiograms were deemed inadequate by the Angiography Core Laboratory were included for hemodynamic analyses.

Catheterization hemodynamic variables

Hemodynamic variables were collected prospectively for each enrolled subject. These data were collected during catheterization in a baseline state, defined as the period when the subject was stable and prior to any intervention. The type of sedation and presence or absence of supplemental oxygen were recorded. If more than one measurement was obtained, the average of all stable baseline measurements was recorded. Coronary perfusion pressure was calculated as the aortic or femoral artery diastolic pressure minus the ventricular EDP.

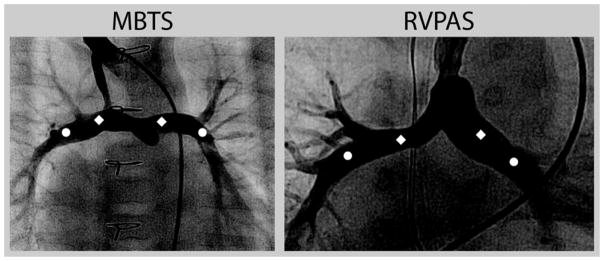

Shunt and pulmonary angiographic measurements

The Angiography Core Laboratory received angiograms blinded for subject demographics and medical center location. All angiograms were assessed for the presence of a reliable calibration factor, and image quality was scored to determine whether the angiograms were acceptable to perform complete measurements. Each measurement was performed to the nearest 0.1mm either digitally (Philips Inturis, Digital Angiographic Analysis, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) or by using digital calipers (Absolute, Digimatic, Mitutoya, Japan). Measurements were conducted separately by two physicians trained in angiography, and if there was a significant discrepancy, the study was re-reviewed and adjudicated such that discrepancies were resolved prior to entering the final data from the Angiography Core Laboratory. For both the right and left pulmonary arteries, specific measurement locations (Figure 1) were defined as the mid-main branch pulmonary artery (between shunt anastomosis and upper lobe branch or proximal to the upper lobe branch for the side contralateral to the shunt) and the proximal lower lobe branch pulmonary artery (between take-off of the upper lobe branch and lower lobe segments). These specific locations were selected to avoid measuring stenotic areas as representative of pulmonary artery growth in often-complex anatomy. The Nakata index was measured using the following formula: (10). In addition, angiograms were assessed for presence of shunt stenosis (proximal or distal), and unilateral or bilateral branch pulmonary artery stenosis. Percent stenosis was calculated with the following formula: . The severity of branch pulmonary artery stenosis was quantified as none (< 15%), mild (15 – 35%), moderate (>35 – 50%), or severe (>50%).

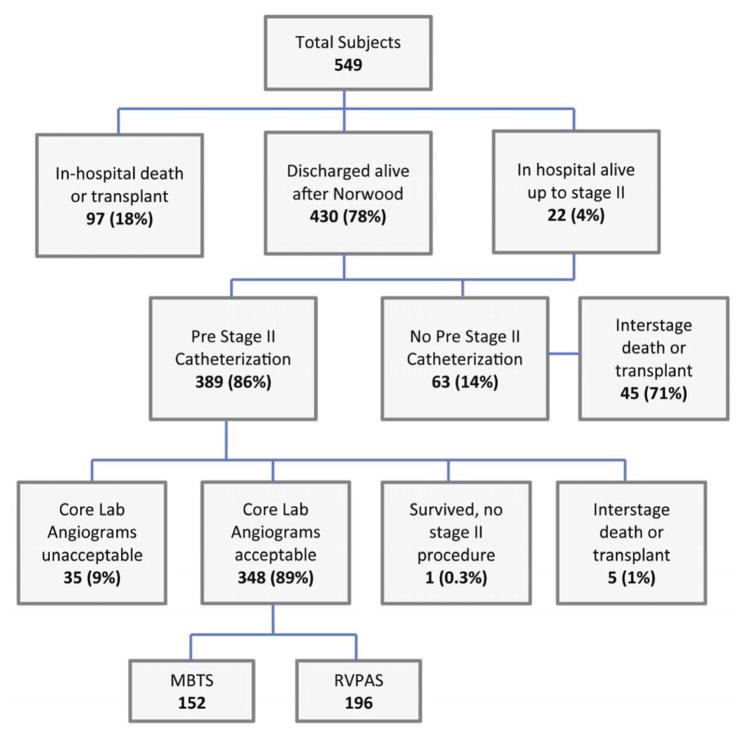

Figure 1.

Location of Branch Pulmonary Artery Measurements.

Diamonds mark the mid-main pulmonary artery measurement location, and circles mark the proximal lower lobe pulmonary artery measurement location. Abbreviations: MBTS, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt.

Statistical analyses

Shunt comparisons were performed with Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test as appropriate for continuous measures. Categorical measures were compared by shunt type with a Fisher exact test; ordinal measures were additionally compared with Mantel-Haenszel’s test for trend. The shunt type used in statistical analyses is the actual shunt type in place at the end of the Norwood procedure and thus represents a non-intention-to-treat analysis. Hazard ratios (HR) and associations between hemodynamic variables as well as angiographic measurements and 12 month transplant-free survival were examined with the Cox proportional hazards model. Interactions between shunt type and hemodynamic and angiographic measures were examined. Continuous measures were examined as quartiles when non-linear associations were identified. Due to the limited number of deaths and transplants in subjects with cardiac catheterization data, multivariate analysis was not practical, and associations with 12-month transplant-free survival were therefore unadjusted. The proportional hazards assumption was examined for each measure. Incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for catheter interventions were calculated using Poisson regression. The P values presented are raw and do not adjust for multiple comparisons. Due to the large number of comparisons performed, P values ≤ 0.01 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and R version 2.12.0.

Results

Study population

Of the 549 SVR trial subjects, this analysis was restricted to the 389 subjects who had a pre-stage II cardiac catheterization, which included 348 subjects with angiograms deemed adequate for analysis (MBTS n=152, RVPAS n=196; Figure 2). Reasons that catheterization was not performed are summarized in figure 2 and included in-hospital death or transplant (n=97), interstage death or transplant (n=45), and institutional preference (n=18). Age, body surface area (BSA), and angiogram acceptability did not differ between shunt types (Table 1). BSA at initial palliation also did not differ by shunt type (p=0.63), and frequency of low BSA did not differ between groups either at initial surgical palliation (p=0.30) or at catheterization (p=0.84). Among those with adequate pre-stage II cardiac catheterization angiography, there were 23 subjects (6.6%) who either died or underwent cardiac transplantation after the stage II procedure and prior to 12 months post-randomization (MBTS 6%, RVPAS 7%).

Figure 2.

SVR Trial Subjects’ Outcomes and Subgroup with Acceptable Pre-stage II Angiography

Abbreviations: MBTS, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt.

Table 1.

Demographic Data by Shunt Type

| Total | MBTS | RVPAS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac catheterization, n | 389 | 170 | 217 |

| Acceptable angiograms for analysis, n | 348 | 152 | 196 |

| Age at cath, months | 4.4±1.5 | 4.5±1.5 | 4.4±1.5 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 0.31±0.04 | 0.31±0.04 | 0.31±0.04 |

Data shown as mean ± standard deviation

MBTS, modified Blalock Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt

Sedation type

For the entire cohort undergoing cardiac catheterization, the procedure was performed under general anesthesia in 63% of patients and under intravenous sedation in the remaining 37%. RVPAS patients were more likely to be placed under general anesthesia than MBTS patients (69% vs. 56%, P=0.01).

Cardiovascular hemodynamic variables

For the entire cohort, three anthropometric or hemodynamic variables obtained at the pre-stage II cardiac catheterization demonstrated associations by univariate analysis with transplant or death at 12-months. These included body surface area (HR per 1 standard deviation decrease=1.87, 95% CI=1.32–2.64, P<0.001), superior vena caval saturation (HR per 1 percent decrease=1.07, 95% CI=1.03–1.12, P=0.002), and ventricular EDP (HR per 1 mmHg increase=1.17, 95% CI=1.07–1.30, P=0.006). A larger Qp:Qs ratio was associated with increased risk for only the RVPAS group (HR per 0.1 increase=1.11, 95% CI=1.02–1.21, P=0.01).

Hemodynamic data examined by shunt type (Table 2) demonstrated that the MBTS group, compared with the RVPAS group, had a higher Qp:Qs ratio, significantly lower systemic diastolic pressure and calculated coronary perfusion pressure, but similar systemic ventricle EDP.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic Variables by Actual Shunt Type

| Hemodynamic variable | Total (n=387) | MBTS (n=170) | RVPAS (n=217) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 38±8 | 35±7 | 40±7 | <0.001 |

| Coronary perfusion pressure (mmHg) | 29±8 | 27±8 | 32±8 | <0.001 |

| Ventricular end diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 8.3±3.3 | 8.7±3.4 | 7.9±3.2 | 0.02 |

| Aortic saturation (%) | 75±6 | 75±5 | 74±6 | 0.09 |

| Superior vena cava saturation (%) | 50±8 | 50±8 | 50±8 | 0.54 |

| Qp:Qs ratio | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.009 |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure | 15 (13–17) | 14 (13–17) | 15 (12–18) | 0.98 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (Wood unit × m2) | 2.0 (1.3–2.6) | 2.0 (1.3–2.3) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) | 0.25 |

| General anesthesia for procedural sedation | 242 (63%) | 95 (56%) | 147 (69%) | 0.01 |

Data shown as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range), or N (%)

MBTS, modified Blalock Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt; Qp, pulmonary blood flow; Qs, systemic blood flow.

P values comparing the MBTS to the RVPAS are from Student’s T-test for means, Wilcoxon rank-sum test for medians, or a Fisher Exact Test for frequencies.

Shunt and pulmonary artery abnormalities

Overall 55% of subjects had angiographic findings of shunt or branch pulmonary artery stenosis, including 33% with moderate or worse (> 35%) branch pulmonary artery stenosis (Table 3). The RVPAS group demonstrated more frequent shunt stenosis (MBTS 14% vs. RVPAS 28%, P=0.004). When the location of shunt stenosis was assessed, the RVPAS group more often developed proximal shunt stenosis, while distal shunt stenosis rates were similar between groups. Total pulmonary artery growth was also decreased in the RVPAS group, as reflected in smaller right and left mid-main branch pulmonary artery diameters, as well as smaller proximal right lower lobe and lower Nakata index (Table 4). For the entire cohort, severe (>50%) branch pulmonary artery stenosis occurred in 9.5% in the right pulmonary artery (RPA) and 5.5% in the left pulmonary artery (LPA); severe RPA stenosis did not differ between groups (MBTS 5.9% vs. RVPAS 12%, P=0.18), but MBTS subjects less often developed severe LPA stenosis (MBTS 0.7% vs. RVPAS 9.2%, P=0.003). When comparing the narrowest diameter of the stenotic branch pulmonary artery segment, the RVPAS group had a smaller diameter for the stenotic portion of the RPA (2.9±0.9 mm vs. 4.0±1.3 mm, P<0.001), but not the LPA (2.9±1.0 vs. 3.3±1.0, P=0.06).

Table 3.

Angiographic Pulmonary Artery and Shunt Abnormalities by Shunt Type

| Angiographic Abnormality | Total (n=348) | MBTS (n=152) | RVPAS (n=196) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid main RPA stenosis | 110 (32%) | 38 (25%) | 72 (37%) | 0.02 |

| Severe RPA stenosis, any location | 33 (9%) | 9 (6%) | 24 (12%) | 0.18 |

| Mid main LPA stenosis | 79 (23%) | 30 (20%) | 49 (25%) | 0.30 |

| Severe LPA stenosis, any location | 19 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 18 (9%) | 0.003 |

| All Shunt stenosis | 75 (22%) | 21 (14%) | 54 (28%) | 0.004 |

| Proximal shunt stenosis | 33 (10%) | 6 (4%) | 27 (14%) | 0.008 |

Data shown as N (%)

Abbreviations: MBTS, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt; RPA, right pulmonary artery; LPA, left pulmonary artery

P values comparing the MBTS to the RVPAS are from a Fisher Exact Test.

Table 4.

Pulmonary Artery Measurements by Shunt Type

| Measurement | Total (n=348) | MBTS (n=152) | RVPAS (n=196) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mid-main LPA (mm) | 4.5 (3.6–5.7) | 4.8 (4.0–6.0) | 4.3 (3.4–5.4) | 0.009 |

| Mid-main LPA, indexed (mm/m2) | 15.1 (11.9–17.9) | 15.8 (13.0–18.4) | 14.2 (11.3–17.5) | 0.003 |

| Mid-main RPA (mm) | 4.6 (3.6–5.7) | 5.0 (4.0–6.1) | 4.2 (3.4–5.2) | <0.001 |

| Mid-main RPA, indexed (mm/m2) | 15.0 (11.6–18.4) | 16.5 (13.0–19.9) | 13.9 (10.7–17.1) | <0.001 |

| Proximal right lower lobe (mm) | 5.7±1.8 | 6.3±2.1 | 5.1±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Proximal right lower lobe, indexed (mm/m2) | 18.4±5.6 | 20.7±6.2 | 16.7±4.4 | <0.001 |

| Proximal left lower lobe (mm) | 5.3±1.6 | 5.4±1.6 | 5.2±1.7 | 0.54 |

| Proximal left lower lobe, indexed (mm/m2) | 17.3±5.2 | 17.6±5.1 | 17.1±5.4 | 0.36 |

| Nakata index (mm2/m2) | 147 (110–196) | 164 (125–226) | 134 (100–180) | <0.001 |

Data shown as mean ± standard deviation or median [inter-quartile range, IQR]. Indexed data are indexed to body surface area at the time of catheterization.

Abbreviations: LPA, left pulmonary artery; RPA, right pulmonary artery; MBTS, modified Blalock-Taussig shunt; RVPAS, right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt.

P values comparing the MBTS to the RVPAS are from Student’s T-test for means or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for medians.

For the entire cohort, no single angiographic measurement was associated with 12-month transplant-free survival. The Nakata index was also not predictive of 12-month transplant-free survival.

Discussion

Our analysis represents the first prospective study to examine in detail hemodynamic and angiographic variables and their relationship with outcome in patients after Norwood procedure randomized to MBTS or RVPAS.

Hemodynamic parameters

Hemodynamic measures associated with increased risk of death or transplant at 12 months include smaller size (as evidenced by lower BSA), higher ventricular EDP, and lower SVC saturation. Higher EDP, likely reflective of poor diastolic function or increased pulmonary blood flow, would also result in increased pulmonary artery pressure after the stage II procedure. Lower SVC saturation may represent poor cardiac output or lower arterial oxygen saturation. It is not surprising that both parameters are associated with worse outcomes at 12 months. With respect to comparison of hemodynamic parameters by shunt type, our analysis was consistent with previous reports regarding retrograde aortic flow pattern(11), lower aortic diastolic pressure, and lower coronary perfusion pressure in MBTS subjects(12). Although clear data are lacking, the latter finding may result in chronic injury to the ventricular myocardium in MBTS subjects, which could explain the finding in the SVR trial of lower transplant-free survival at 12 months in MBTS subjects. On the other hand, RVPAS subjects require a ventriculotomy, which may negatively impact late ventricular function and result in the development of ventricular arrhythmias. This could in turn offset the early advantages of higher coronary perfusion pressure(13). However, this potential disadvantage of a right ventriculotomy for RVPAS subjects remains controversial. Tanoue and colleagues(14) found that, following the stage II procedure, RVPAS subjects had worse right ventricular systolic function compared with MBTS subjects. Due to concerns for late ventricular dysfunction, Ballweg and colleagues(3) analyzed 124 infants that underwent a stage II procedure for single ventricle physiology and reported no difference in 3-year survival despite RVPAS subjects having a higher incidence of ventricular dysfunction by echocardiography at the time of the stage II procedure. Graham and colleagues(13) demonstrated no difference in hospital survival comparing shunt types for 76 infants with single ventricle physiology, but higher interstage mortality for MBTS subjects (22% vs. 3%, P=0.05). These results are supported by Mahle and colleagues(15), who reported operative and 1-year survival of 81% for RVPAS subjects, with no difference in Qp:Qs or survival between shunt types, suggesting that equivalent pulmonary blood flows may result in equivalent survivals.

Angiographic Findings

Analysis of our data demonstrated that overall pulmonary artery growth was less in the RVPAS group, and that no angiographic measurement was associated with 12-month transplant-free survival. During the interstage period, pulmonary artery growth is dependent on blood flow entering the branch pulmonary arteries across the surgical shunt. Potential explanations for differences in branch pulmonary artery growth patterns include anatomical abnormalities with the shunt or branch pulmonary arteries(16) and hemodynamic factors such as shunt diameter(12), as well as pulsatile versus non-pulsatile shunt blood flow(11). In contrast to our findings of inferior pulmonary artery growth in the RVPAS cohort, Januszewska and colleagues(17) reported that despite RVPAS subjects’ having a significantly lower Qp:Qs (0.8 vs. 1.2), lower aortic oxygen saturation (67.4% vs. 75.3%), and lower SVC oxygen saturation (43.5% vs. 49.7%), they had good, symmetric pulmonary artery growth prior to the stage II procedure. One purported advantage of the RVPAS is that it allows pulsatile flow into the branch pulmonary arteries, which may improve interstage pulmonary artery growth, as compared with the MBTS, which provides continuous flow.

Shunt and pulmonary artery stenosis

Stenoses of the shunt or branch pulmonary arteries can have significant adverse effects in this population of patients. Obstruction to shunt-dependent blood flow results in poor branch pulmonary artery growth(18), and branch pulmonary artery hypoplasia is a risk factor at the time of the stage II procedure(19, 20). In addition, the presence of central pulmonary artery stenoses frequently requires catheter-based intervention or surgical revision at the time of the stage II procedure(4, 16). For the entire cohort and irrespective of shunt type, branch pulmonary artery stenosis occurred nearly 50% of the time in both the LPA and the RPA. This finding is consistent with a report from Griselli and colleagues(16) that 50% of infants undergoing a Norwood procedure develop central pulmonary artery stenosis that requires surgical revision during the stage II procedure. In our angiographic analyses, the RVPAS subjects more often had stenosis in the shunt, more often developed moderate-to-severe branch pulmonary artery stenosis, and had a significantly smaller absolute diameter of the stenotic portion of the RPA. Our data demonstrate that the Nakata index prior to the stage II procedure was lower than previously reported for both shunt types and significantly lower for RVPAS subjects. This is in contrast to prior single center, nonrandomized studies which have reported that subjects with RVPAS, compared with MBTS, have larger branch pulmonary arteries at the time of the stage II procedure(21).

By defining specific branch pulmonary artery measurement locations (Figure 1), our analysis was potentially able to avoid using the stenotic lesion for part of the measurement. Due to complex stenoses, the diameter of the proximal lower lobe pulmonary arteries may provide a more accurate assessment of branch pulmonary artery growth. Determination of the clinical significance of differences in branch pulmonary artery size among survivors will require longer-term follow-up. The RVPAS group had a significantly smaller mid-main LPA, mid-main RPA, and proximal right lower lobe pulmonary artery, while the proximal left lower lobe pulmonary artery diameters were similar. Moreover, the RVPAS subjects had a 1-year transplant-free survival advantage in the SVR trial(8). It is possible that the hemodynamic effects are more important and ultimately outweigh the effects of smaller pulmonary arteries.

Study limitations

Data on other factors which could impact survival, such as aortic arch obstruction, ventricular function, and atrioventricular valve regurgitation, were limited. We consciously did not analyze detailed surgical shunt features such as size, length, insertion site, beveled anastomosis, and size of innominate artery. Assumptions regarding calculation of coronary perfusion pressure may have been erroneous in subjects with concomitant aortic arch obstruction. Mode of sedation was different between groups and may have impacted hemodynamic measures. Due to the study design, we had no hemodynamic or angiographic information on subjects with interstage mortality. Because a greater number of MBTS subjects died during Norwood hospitalization or during the interstage period, there is the potential for survivor bias that may impact shunt type comparisons. Shunt comparisons and associations with 12-month transplant-free survival were performed without adjustment for potential confounders due to the limited number of deaths and cardiac transplants. Finally, due to the limited number of events in the transplant-free survival analyses, the statistical power to detect significant findings was limited.

Conclusion

Analysis of pre-stage II catheterization data for SVR trial subjects shows that, compared with RVPAS subjects, MBTS subjects had more hemodynamic abnormalities related to shunt physiology, including lower systemic diastolic and coronary perfusion pressures, higher ventricular EDP, and higher Qp:Qs ratio. Conversely, RVPAS subjects had more shunt or pulmonary obstruction of a severe degree, and inferior pulmonary artery growth at pre-stage II catheterization. Lower BSA, higher ventricular EDP, and lower SVC saturation were associated with worse 12-month transplant-free survival for the entire cohort, while no single angiographic measurement had such association.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Supported by U01 grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL068269, HL068270, HL068279, HL068281, HL068285, HL068292, HL068290, HL068288, HL085057, HL109781, HL109737).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CI

confidence interval

- EDP

end-diastolic pressure

- HR

hazard ratio

- LPA

left pulmonary artery

- MBTS

modified Blalock-Taussig shunt

- RPA

right pulmonary artery

- RVPAS

right ventricle-pulmonary artery shunt

- SVC

superior vena cava

- SVR

single ventricle reconstruction

APPENDIX

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Gail Pearson, Victoria Pemberton, Rae-Ellen Kavey*, Mario Stylianou, Marsha Mathis*.

Network Chair: University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Lynn Mahony

Data Coordinating Center: New England Research Institutes, Lynn Sleeper (PI), Sharon Tennstedt (PI), Steven Colan, Lisa Virzi*, Patty Connell*, Victoria Muratov*, Lisa Wruck*, Minmin Lu, Dianne Gallagher, Anne Devine*, Julie Schonbeck, Thomas Travison*, David F. Teitel

Core Clinical Site Investigators: Children’s Hospital Boston, Jane W. Newburger (PI), Peter Laussen*, Pedro del Nido, Roger Breitbart, Jami Levine, Ellen McGrath, Carolyn Dunbar-Masterson, John E. Mayer, Jr., Frank Pigula, Emile A. Bacha, Francis Fynn-Thompson; Children’s Hospital of New York, Wyman Lai (PI), Beth Printz*, Daphne Hsu*, William Hellenbrand, Ismee Williams, Ashwin Prakash*, Seema Mital*, Ralph Mosca*, Darlene Servedio*, Rozelle Corda, Rosalind Korsin, Mary Nash*; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Victoria L. Vetter (PI), Sarah Tabbutt*, J. William Gaynor (Study Co-Chair), Chitra Ravishankar, Thomas Spray, Meryl Cohen, Marisa Nolan, Stephanie Piacentino, Sandra DiLullo*, Nicole Mirarchi*; Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center, D. Woodrow Benson* (PI), Catherine Dent Krawczeski, Lois Bogenschutz, Teresa Barnard, Michelle Hamstra, Rachel Griffiths, Kathryn Hogan, Steven Schwartz*, David Nelson, Pirooz Eghtesady*; North Carolina Consortium: Duke University, East Carolina University, Wake Forest University, Page A. W. Anderson (PI) – deceased, Jennifer Li (PI), Wesley Covitz, Kari Crawford*, Michael Hines*, James Jaggers*, Theodore Koutlas, Charlie Sang, Jr., Lori Jo Sutton, Mingfen Xu; Medical University of South Carolina, J. Philip Saul (PI), Andrew Atz, Girish Shirali*, Scott Bradley, Eric Graham, Teresa Atz, Patricia Infinger; Primary Children’s Medical Center and the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, L. LuAnn Minich (PI), John A. Hawkins-deceased, Michael Puchalski, Richard V. Williams, Peter C. Kouretas, Linda M. Lambert, Marian E. Shearrow, Jun A. Porter*; Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Brian McCrindle (PI), Joel Kirsh, Chris Caldarone, Elizabeth Radojewski, Svetlana Khaikin, Susan McIntyre, Nancy Slater; University of Michigan, Caren S. Goldberg (PI), Richard G. Ohye (Study Chair), Cheryl Nowak*; Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and Medical College of Wisconsin, Nancy S. Ghanayem (PI), James S. Tweddell, Kathleen A. Mussatto, Michele A. Frommelt, Peter C. Frommelt, Lisa Young-Borkowski.

Auxiliary Sites: Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Alan Lewis (PI), Vaughn Starnes, Nancy Pike; The Congenital Heart Institute of Florida (CHIF), Jeffrey P. Jacobs (PI), James A. Quintessenza, Paul J. Chai, David S. Cooper*, J. Blaine John, James C. Huhta, Tina Merola, Tracey Griffith; Emory University, William Mahle (PI), Kirk Kanter, Joel Bond*, Jeryl Huckaby; Nemours Cardiac Center, Christian Pizarro (PI), Carol Prospero; Julie Simons, Gina Baffa, Wolfgang A. Radtke; University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Ilana Zeltzer (PI), Tia Tortoriello*, Deborah McElroy, Deborah Town.

Angiography Core Laboratory: Duke University, John Rhodes, J. Curt Fudge*

Echocardiography Core Laboratories: Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Peter Frommelt; Children’s Hospital Boston, Gerald Marx.

Genetics Core Laboratory: Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Catherine Stolle.

Protocol Review Committee: Michael Artman (Chair); Erle Austin; Timothy Feltes, Julie Johnson, Thomas Klitzner, Jeffrey Krischer, G. Paul Matherne.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board: John Kugler (Chair); Rae-Ellen Kavey, Executive Secretary; David J. Driscoll, Mark Galantowicz, Sally A. Hunsberger, Thomas J. Knight, Holly Taylor, Catherine L. Webb.

*no longer at the institution listed

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov #: NCT00115934

Relationships with industry: None to disclose related to this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alsoufi B, Bennetts J, Verma S, Caldarone CA. New developments in the treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatrics. 2007 Jan;119(1):109–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornik CP, He X, Jacobs JP, Li JS, Jaquiss RD, Jacobs ML, et al. Complications after the Norwood operation: an analysis of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011 Nov;92(5):1734–40. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballweg JA, Dominguez TE, Ravishankar C, Kreutzer J, Marino BS, Bird GL, et al. A contemporary comparison of the effect of shunt type in hypoplastic left heart syndrome on the hemodynamics and outcome at stage 2 reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007 Aug;134(2):297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabbutt S, Dominguez TE, Ravishankar C, Marino BS, Gruber PJ, Wernovsky G, et al. Outcomes after the stage I reconstruction comparing the right ventricular to pulmonary artery conduit with the modified Blalock Taussig shunt. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005 Nov;80(5):1582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.046. discussion 90–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azakie A, Martinez D, Sapru A, Fineman J, Teitel D, Karl TR. Impact of right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit on outcome of the modified Norwood procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 May;77(5):1727–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pizarro C, Mroczek T, Malec E, Norwood WI. Right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit reduces interim mortality after stage 1 Norwood for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Dec;78(6):1959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.020. discussion 63–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano S, Ishino K, Kado H, Shiokawa Y, Sakamoto K, Yokota M, et al. Outcome of right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt in first-stage palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a multi-institutional study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Dec;78(6):1951–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.055. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohye RG, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Lu M, et al. Comparison of shunt types in the Norwood procedure for single-ventricle lesions. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 27;362(21):1980–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohye RG, Gaynor JW, Ghanayem NS, Goldberg CS, Laussen PC, Frommelt PC, et al. Design and rationale of a randomized trial comparing the Blalock-Taussig and right ventricle-pulmonary artery shunts in the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008 Oct;136(4):968–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakata S, Imai Y, Takanashi Y, Kurosawa H, Tezuka K, Nakazawa M, et al. A new method for the quantitative standardization of cross-sectional areas of the pulmonary arteries in congenital heart diseases with decreased pulmonary blood flow. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984 Oct;88(4):610–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohye RG, Ludomirsky A, Devaney EJ, Bove EL. Comparison of right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit and modified Blalock-Taussig shunt hemodynamics after the Norwood operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Sep;78(3):1090–3. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(03)01386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Migliavacca F, Pennati G, Dubini G, Fumero R, Pietrabissa R, Urcelay G, et al. Modeling of the Norwood circulation: effects of shunt size, vascular resistances, and heart rate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001 May;280(5):H2076–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham EM, Atz AM, Bradley SM, Scheurer MA, Bandisode VM, Laudito A, et al. Does a ventriculotomy have deleterious effects following palliation in the Norwood procedure using a shunt placed from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries? Cardiol Young. 2007 Apr;17(2):145–50. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanoue Y, Kado H, Shiokawa Y, Fusazaki N, Ishikawa S. Midterm ventricular performance after Norwood procedure with right ventricular-pulmonary artery conduit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004 Dec;78(6):1965–71. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.014. discussion 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahle WT, Cuadrado AR, Tam VK. Early experience with a modified Norwood procedure using right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003 Oct;76(4):1084–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00343-6. discussion 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griselli M, McGuirk SP, Ofoe V, Stumper O, Wright JG, de Giovanni JV, et al. Fate of pulmonary arteries following Norwood Procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006 Dec;30(6):930–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Januszewska K, Kozlik-Feldmann R, Dalla-Pozza R, Greil S, Abicht J, Netz H, et al. Right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt related complications after Norwood procedure. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011 Sep;40(3):584–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caspi J, Pettitt TW, Mulder T, Stopa A. Development of the pulmonary arteries after the Norwood procedure: comparison between Blalock-Taussig shunt and right ventricular-pulmonary artery conduit. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008 Oct;86(4):1299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas WI, Goldberg CS, Mosca RS, Law IH, Bove EL. Hemi-Fontan procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome: outcome and suitability for Fontan. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999 Oct;68(4):1361–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00915-7. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Januszewska K, Kolcz J, Mroczek T, Procelewska M, Malec E. Right ventricle-to-pulmonary artery shunt and modified Blalock-Taussig shunt in preparation to hemi-Fontan procedure in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005 Jun;27(6):956–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rumball EM, McGuirk SP, Stumper O, Laker SJ, de Giovanni JV, Wright JG, et al. The RV-PA conduit stimulates better growth of the pulmonary arteries in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005 May;27(5):801–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]