Abstract

Our objective was to examine associations between glucose metabolism, as measured by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET), and age and to evaluate the impact of carriage of an apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele on glucose metabolism and on the associations between glucose metabolism and age. We studied 806 cognitively normal (CN) and 70 amyloid-imaging-positive cognitively impaired participants (35 with mild cognitive impairment and 35 with Alzheimer’s disease [AD] dementia) from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging, Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and an ancillary study who had undergone structural MRI, FDG PET, and 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) PET. Using partial volume corrected and uncorrected FDG PET glucose uptake ratios, we evaluated associations of regional FDG ratios with age and carriage of an APOE ε4 allele in CN participants between the ages of 30 and 95 years, and compared those findings with the cognitively impaired participants. In region-of-interest (ROI) analyses, we found modest but statistically significant declines in FDG ratio in most cortical and subcortical regions as a function of age. We also found a main effect of APOE ε4 genotype on FDG ratio, with greater uptake in ε4 noncarriers compared with carriers but only in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, lateral parietal, and AD-signature meta-ROI. The latter consisted of voxels from posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, lateral parietal, and inferior temporal. In age- and sex-matched CN participants the magnitude of the difference in partial volume corrected FDG ratio in the AD-signature meta-ROI for APOE ε4 carriers compared with noncarriers was about 4 times smaller than the magnitude of the difference between age- and sex-matched elderly APOE ε4 carrier CN compared with AD dementia participants. In an analysis in participants older than 70 years (31.3% of whom had elevated PiB), there was no interaction between PiB status and APOE ε4 genotype with respect to glucose metabolism. Glucose metabolism declines with age in many brain regions. Carriage of an APOE ε4 allele was associated with reductions in FDG ratio in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, lateral parietal, and AD-signature ROIs, and there was no interaction between age and APOE ε4 status. The posterior cingulate and/or precuneus and lateral parietal regions have a unique vulnerability to reductions in glucose metabolic rate as a function both of age and carriage of an APOE ε4 allele.

Keywords: Aging, Alzheimer’s disease, FDG positron emission tomography, Apolipoprotein E

1. Introduction

Understanding the influence of aging on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers is essential to our ongoing effort to model the pathophysiology of AD (Jack et al., 2013). For 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET), there has been controversy about whether brain glucose metabolism declines with aging in the absence of cognitive impairment. Early reports claimed that there were declines in glucose metabolism (Herholz et al., 2002; Loessner et al., 1995). Most subsequent studies but not all (Kalpouzos et al., 2009) claimed that declines in glucose metabolism over the adult age spectrum were abolished by partial volume correction (Ibanez et al., 2004; Kantarci et al., 2010; Yanase et al., 2005). Any analysis of the role of age on glucose metabolism must also take apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype into account. Reductions in glucose metabolism in regions known to be affected in AD dementia (Chetelat et al., 2008; Mosconi, 2005; Nestor et al., 2003; Rabinovici et al., 2010) have been shown in cognitively normal middle-aged carriers of the APOE ε4 allele (Reiman et al., 1996, 2001).

We examined associations between glucose metabolism, as measured by FDG PET and age in a large number of cognitively normal (CN) individuals. We also evaluated the impact of carriage of an APOE ε4 allele on glucose metabolic rate and whether the associations between FDG and age differed among APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers. A group of persons with cognitive impairment due to of AD were also studied for comparison purposes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We studied 806 CN participants who had undergone structural MRI, FDG PET, and PiB PET and had available APOE genotype data. They were drawn from 2 sources. The first was the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA). The MCSA is a population-based study in Olmsted County MN that originally enrolled persons between the ages of 70 and 89 years. The initial recruitment and description of baseline imaging has been described (Jack et al., 2012; Roberts et al., 2008). After the initial wave of participants were recruited beginning in October 1, 2004, the group has subsequently been replenished with new participants in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011. In 2012, the MCSA was expanded to include persons between the ages of 50 and 69 years. These participants were also drawn randomly from Olmsted County, MN, USA. In both the older than 70 and the 50 to 69-year-olds, every participant without contraindications to magnetic resonance (MR) scanning was offered the opportunity to undergo MR and PET imaging. The participants in both these groups were diagnosed as being CN through a consensus process that used information from 3 sources: a mental status examination performed by a study physician, a Clinical Dementia Rating completed by a trained study coordinator that included an interview of an informant as well as the participant and a psychometric battery previously described for the CN group (Petersen et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2008, 2012) and for the Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Kantarci et al., 2008). The second source of participants was a convenience sample of Rochester, MN residents between the ages of 30 and 49 years who were specifically recruited via flyers and word of mouth to undergo brain imaging. This group of younger participants also received the same psychometric battery as the older cognitively normal persons; all scored in the normal range.

For purposes of comparison of the magnitude of the impact of APOE genotype versus being cognitively impaired on FDG ratios, we also included 35 individuals with AD dementia from the MCSA or the Mayo Clinic ADRC who were aged 70 years or older, APOE ε4 carriers, and amyloid imaging positive. These AD dementia participants were matched on sex and age ±5 years to 35 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) participants from the MCSA or Mayo ADRC who were APOE ε4 carriers and positive on amyloid imaging from the MCSA. Both MCI and AD dementia participants were also age- and sex-matched with APOE ε4 carrier CN participants. The MCI and AD dementia individuals were diagnosed via the same consensus process described previously. The diagnosis of MCI (Albert et al., 2011) and dementia because of AD (McKhann et al., 2011) followed standard criteria.

DNA extraction and APOE genotyping was performed for each subject using standard methods (Hixson and Vernier, 1990).

2.2. Human subjects protections

All study protocols were approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards, and all cognitively normal participants provided signed informed consent to participate in the study and in the imaging protocols. In participants with cognitive impairment, they and their accompanying family member jointly provided consent.

2.3. Imaging methods

Imaging methods for structural MR, FDG PET, and PiB PET were identical to those that have been described previously (Jack et al., 2008, 2012; Knopman et al., 2012). For FDG-PET scanning, participants were injected with 366–399 MBq of FDG and imaged after 30–38 minutes, for an 8-minute image acquisition consisting of four 2-minute dynamic frames. During the 30-minute uptake period, participants were left undisturbed in a darkened room and instructed to rest quietly without activity with their eyes open. The scans were performed with eyes open. A CT image was obtained for attenuation correction. Regional cerebral glucose uptake at the static time point 30 minutes after FDG injection was expressed as a ratio of each region’s FDG uptake to that of the pons, which we will refer to as the FDG ratio.

Quantitative image analysis for FDG PET was performed using our in-house fully automated image processing pipeline (Jack et al., 2008; Lopresti et al., 2005). Statistics on image voxel values were extracted from automatically labeled cortical regions of interest (ROIs) using an atlas (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002) modified in-house. There were 19 regions of interest after combining the left and right regions from the atlas. In addition to atlas-defined regions, we also identified a meta-region of interest (ROI) that we have labeled as an “AD signature meta-ROI” that included pre-defined voxels in the angular gyrus, posterior cingulate, and inferior temporal cortical regions from both hemispheres combined (Landau et al., 2011). The pons was used as the reference region for the atlas-defined ROIs as well as for the AD signature region.

Amyloid PET images were acquired using a GE Discovery RX PET/CT scanner. Subjects are injected with 292–729 MBq 11C PiB. The PiB PETscan consists of four 5-minute dynamic frames and was acquired from 40 minutes after injection (McNamee et al., 2009; Price et al., 2005). PiB PET scans were obtained on the same day 1 hour before the FDG PET scan. In the current analyses, amyloid PET results were used only to define the MCI and dementia because of AD comparison groups. A cortical PiB PETstandardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) was formed by combining the prefrontal, orbitofrontal, parietal, temporal, anterior cingulate, and posterior cingulate and/or precuneus ROI values normalized by the cerebellar gray matter ROI of the atlas. We defined an abnormal PiB scan as an SUVr > 1.5 (Jack et al., 2012).

All participants underwent MR scanning at 3T with a standardized protocol that included a 3D-MPRAGE sequence (Jack et al., 2008). MPRAGE images were corrected for image distortion and bias field (Gunter et al., 2009) as previously described (Jack et al., 2008). The MR scans were used for atrophy correction of the FDG images.

On MR scans we quantitated white matter hyperintensity volume and numbers of cortical and subcortical infarctions. The MR protocol included a fluid attenuated inversion recovery scan from which we assessed features of cerebrovascular disease. White matter hyper-intensity burden was measured quantitatively using an algorithm developed in-house (Jack et al., 2001). Supratentorial subcortical and cortical infarctions greater than 1 cm were ascertained visually by highly experienced image analysts and confirmed by a radiologist (Kejal Kantarci).

2.4. Atrophy correction

Given concerns that brain volume loss was likely to accentuate regional FDG ratio estimates (Ibanez et al., 2004; Kantarci et al., 2010; Yanase et al., 2005), we chose partial volume corrected analyses as our primary outcome measures. Nonpartial volume corrected data are presented in Appendix Table 2. In one variation of the automated ROI parcellation algorithm, partial volume correction was performed on the FDG images, using a 2-compartment model. Each subject’s FDG images were co-registered with a 6 degrees of freedom affine registration to his or her MRI scan, which was then simultaneously spatially normalized and segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid compartments, using the unified segmentation method of SPM5. The gray matter and white matter segmentations were saved in the subject’s native space and combined to form a brain tissue probability mask, which was then re-sampled to the resolution of the PET image, and smoothed with a 6 mm FWHM Gaussian filter, to approximate the point spread function of the PET camera. Finally, each FDG PET voxel was divided by the corresponding value in this smoothed brain mask, closely following a published method (Meltzer et al., 2000).

Appendix Table 2.

Estimated mean FDG ratio and tests for significant differences in FDG by age and APOE ε4 genotype from linear regression models, not partial volume corrected

| ROI | Estimated mean FDG ratiosa

|

p-values for effect of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young carrier | Young noncarrier | Elderly carrier | Elderly noncarrier | Age p-value | APOE ε4 p-value | Agea APOE ε4 p-value | |

| Anterior cingulate | 1.64 | 1.65 | 1.38 | 1.38 | <0.001 | 0.62 | 0.96 |

| Caudate | 1.55 | 1.56 | 1.26 | 1.29 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.21 |

| Cingulate and/or precuneus | 1.79 | 1.85 | 1.54 | 1.58 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.63 |

| Insula | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.28 | 1.28 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.90 |

| Lateral parietal | 1.69 | 1.72 | 1.43 | 1.46 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.97 |

| Lateral temporal | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.35 | 1.37 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.89 |

| Medial temporal | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.11 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Occipital | 1.70 | 1.73 | 1.53 | 1.55 | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.96 |

| Orbito frontal | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.36 | 1.36 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.98 |

| Pallidum | 1.37 | 1.33 | 1.40 | 1.40 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.21 |

| Paracentral lobule | 1.55 | 1.61 | 1.47 | 1.48 | <0.001 | 0.38 | 0.22 |

| Postcentral gyrus | 1.59 | 1.62 | 1.44 | 1.45 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 0.66 |

| Precentral gyrus | 1.63 | 1.67 | 1.48 | 1.49 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.40 |

| Prefrontal | 1.74 | 1.76 | 1.48 | 1.50 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.84 |

| Primary visual | 1.94 | 1.96 | 1.64 | 1.66 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 0.98 |

| Putamen | 1.83 | 1.82 | 1.62 | 1.63 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 0.91 |

| Rolandic operulum | 1.68 | 1.67 | 1.40 | 1.41 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| Supplementary motor area | 1.70 | 1.74 | 1.50 | 1.52 | <0.001 | 0.61 | 0.57 |

| Thalamus | 1.62 | 1.63 | 1.43 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 0.69 | 0.79 |

| AD signature meta-ROI | 1.84 | 1.87 | 1.52 | 1.56 | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.92 |

Key: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; ROI, region of interest.

Estimated FDG ratios for hypothetical participants based on regression model.

2.5. Statistical methods

Linear regression was used to assess the relationship between FDG ratio and age and APOE ε4 genotype. For each region of interest, we fit a model with age, APOE ε4 carrier versus noncarrier and the interaction between age and APOE ε4 genotype as predictors of FDG ratio. Restricted cubic splines with 3 knots at ages 45, 65, and 80 years were used to allow for nonlinearity in the relationship between FDG ratio and age. We report p-values based on Wald tests. A p-value for the association between FDG ratio and age was based on a joint test of all the coefficients involving age (i.e., main effects and interactions) while a p-value for the association between FDG and APOE ε4 genotype was based on a joint test of all the coefficients involving APOE ε4 genotype.

To estimate the APOE ε4 carrier effect on FDG ratios in CN subjects, we matched 209 APOE ε4 carriers to noncarriers on sex and within the age of 5 years. t Tests were used to test for differences in FDG ratios between the carriers and noncarriers. To estimate the impact of cognitive impairment on FDG ratios, we compared FDG ratios across 3 diagnosis groups that had been matched for sex and age (as previously mentioned): CN (n = 70), MCI (n = 35), and AD dementia (n = 35). We used pairwise t tests to assess significant differences among the groups. FDG ratios were compared across the 3 diagnosis groups and pairwise t tests were used to assess significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Age and FDG ratio

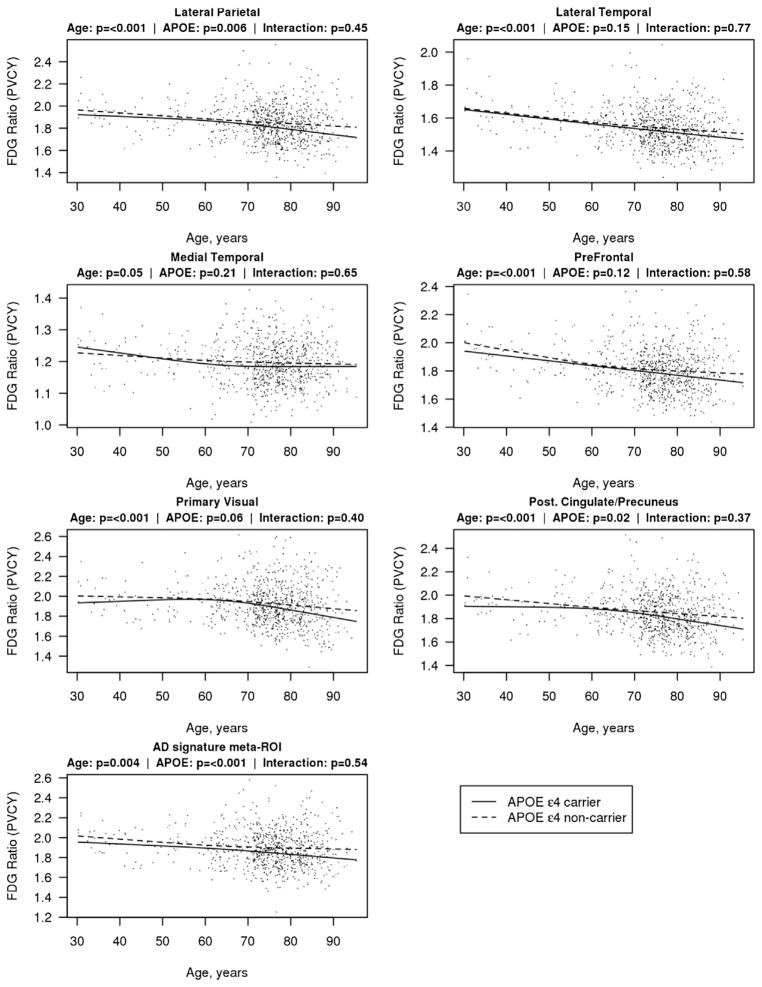

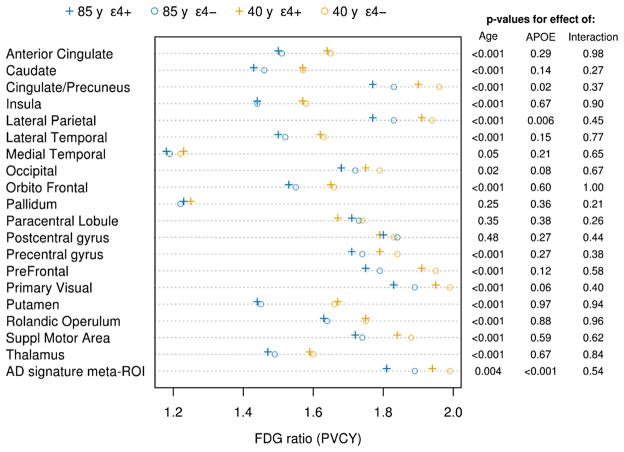

Table 1 summarizes the demographic features of the participants. In ROI analyses, FDG ratio with partial volume correction declined with advancing age in many regions of the brain including the AD signature meta-ROI, putamen, insula, thalamus, anterior cingulate, supplementary motor, lateral temporal, caudate, orbital frontal, posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, prefrontal, rolandic operculum, lateral parietal, primary visual, precentral gyrus, occipital, and medial temporal regions (Figs. 1 and 2, Appendix Table 1). While FDG was associated with age in many regions, the associations were modest. For an example, the estimated mean FDG ratio in the lateral temporal region for a 40-year-old APOE ε4 carrier was 1.62 compared with 1.50 for an 85-year-old APOE ε4 carrier, a decrease of only 0.12 SUVR over 45 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Young normal (N =35) | MCSA 50 to 70-year-old normal (N = 143) | MCSA >70-year-old normal (N = 628) | All cognitively normal (N = 806) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 39 (34, 44) | 64 (61, 68) | 78 (75, 83) | 76 (72, 82) |

| Min, max | 30, 50 | 51, 71 | 71, 95 | 30, 95 |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 18 (51) | 78 (55) | 342 (54) | 438 (54) |

| APOE ε4 positive, no. (%) | 14 (40) | 37 (26) | 158 (25) | 209 (26) |

| Education, y | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 16 (14, 17) | 16 (14, 18) | 14 (12, 16) | 14 (12, 16) |

| Min, max | 12, 20 | 12, 20 | 8, 20 | 8, 20 |

Key: APOE, apolipoprotein E; Max, maximum; MCSA, Mayo Clinic Study of Aging; Min, minimum.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplots of FDG ratio with partial volume correction (PVCY) as a function of age in representative cortical regions. Estimated mean FDG ratio for each age is shown with a solid line for APOE ε4 carriers and a dashed line for APOE ε4 noncarriers. Estimates are from a linear regression model with age, APOE ε4 genotype, and their interaction. Age was fit with restricted cubic splines with 3 knots at ages 45, 65, and 80 years to allow for nonlinearity in the FDG-age relationship. The 7 regions depicted are medial temporal, lateral temporal, lateral parietal, prefrontal, primary visual cortex, posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, and the Alzheimer signature meta-ROI. Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; ROI, region of interest.

Fig. 2.

Graphic illustration (left) and tabular listing of p-values (right) of regional FDG ratios for an average 40-year-old APOE ε4 carrier and noncarrier, and 85-year-old APOE ε4 carrier and noncarrier, where the FDG ratio values were derived from regression analyses. On the right are the p-values for the main effects of age and APOE ε4 carriage, and the p-value for the interaction term. The actual ratio values are given in the Appendix Table 1. “+” signs indicate APOE ε4 carriers and “o” signs indicate APOE ε4 noncarriers. Blue symbols indicate the 85-year-olds and gold symbols the 40-year=olds. Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose.

Appendix Table 1.

Estimated mean FDG ratio and tests for significant differences in FDG by age and APOE ε4 genotype from linear regression models, partial volume corrected

| ROI | Estimated mean FDG ratiosa

|

p-values for effect of:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40-year-old APOE ε4 carrier | 40-year-old APOE ε4 noncarrier | 85-year-old APOE ε4 carrier | 85-year-old APOE ε4 noncarrier | Age | APOE ε4 | Agea APOE ε4 | |

| Anterior cingulate | 1.64 | 1.65 | 1.50 | 1.51 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.98 |

| Caudate | 1.57 | 1.57 | 1.43 | 1.46 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| Cingulate and/or precuneus | 1.90 | 1.96 | 1.77 | 1.83 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| Insula | 1.57 | 1.58 | 1.44 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.90 |

| Lateral parietal | 1.91 | 1.94 | 1.77 | 1.83 | <0.001 | 0.006 | 0.45 |

| Lateral temporal | 1.62 | 1.63 | 1.50 | 1.52 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.77 |

| Medial temporal | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.19 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Occipital | 1.75 | 1.79 | 1.68 | 1.72 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.67 |

| Orbito frontal | 1.65 | 1.66 | 1.53 | 1.55 | <0.001 | 0.60 | 1.00 |

| Pallidum | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 1.22 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.21 |

| Paracentral lobule | 1.67 | 1.74 | 1.71 | 1.73 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.26 |

| Postcentral gyrus | 1.79 | 1.83 | 1.80 | 1.84 | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.44 |

| Precentral gyrus | 1.79 | 1.84 | 1.71 | 1.74 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.38 |

| Prefrontal | 1.91 | 1.95 | 1.75 | 1.79 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.58 |

| Primary visual | 1.95 | 1.99 | 1.83 | 1.89 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.40 |

| Putamen | 1.67 | 1.66 | 1.44 | 1.45 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.94 |

| Rolandic operulum | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 1.64 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.96 |

| Supplementary motor area | 1.84 | 1.88 | 1.72 | 1.74 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 0.62 |

| Thalamus | 1.59 | 1.60 | 1.47 | 1.49 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.84 |

| AD signature meta-ROI | 1.94 | 1.99 | 1.81 | 1.89 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.54 |

Key: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; ROI, region of interest.

Estimated FDG ratios for hypothetical participants based on regression model.

3.2. Cerebrovascular pathology

Because of the frontal predominance of the aging changes in FDG ratio, we speculated that some of the age differences might be related to the burden of cerebrovascular pathology. In a subset of 471 CN subjects who were over the age of 70 years and had available vascular-lesion imaging data, we compared the FDG ratios in the orbito- frontal, prefrontal, and supplementary motor area among subjects by white matter hyperintensity burden quartiles, presence or absence of large cortical infarcts, and presence or absence of subcortical infarcts. None of the vascular features were significantly associated with differences in FDG ratio in these frontal cortical regions (data not shown).

3.3. APOE genotype and FDG ratio

APOE ε4 genotype was associated with lower FDG ratios in the cingulate and/or precuneus and lateral parietal regions and the AD-signature meta-ROI with partial volume correction. In partial volume uncorrected data, only the AD signature region difference remained marginally significant. (Figs. 1 and 2 and Appendix Tables 1 and 2). None of the age × APOE ε4 interactions was significant indicating that the effect of APOE ε4 genotype was similar across all age ranges. However, in examining the subgroup of participants who were between the ages of 30 and 60 years (n = 62), there were no significant regional differences between APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers. We had too few APOE ε4 homozygotes (n = 14) among the CN group to analyze separately.

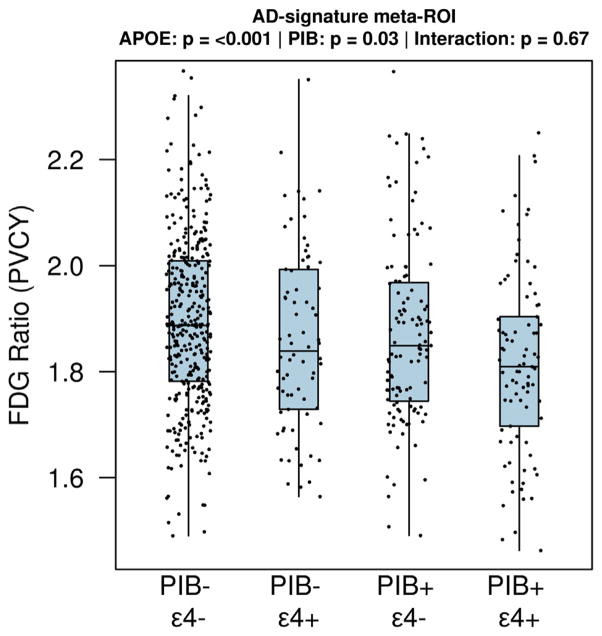

3.4. Amyloid status, APOE genotype, and FDG ratio

Only 6 of our 167 (3.6%) participants younger than 70 years had PiB SUVr > 1.5, while 200 of the 639 (31.3%) older participants had PiB SUVr > 1.5. We examined the impact of high amyloid burden in our cognitive normal individuals older than 70 years. In Fig. 3, we show FDG ratio values from the AD signature meta-ROI for CN participants who had low (SUVr < 1.5) or high (SUVr ≥ 1.5) PiB retention, with or without APOE ε4 genotype. While the FDG ratio was lower in those with higher PiB SUVr (p = 0.03), the APOE ε4 carrier groups showed lower FDG ratios (p < 0.001) with no interaction between the 2 (p = 0.67).

Fig. 3.

Boxplots of the FDG ratio (partial volume corrected [PVCY]) in the AD-signature meta-ROI among 639 elderly (age ≥70) CN participants, stratified by low (SUVr < 1.5) or high (SUVr ≥ 1.5) PiB retention and APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers. The only pairwise comparisons that reached a nominal level of significance (uncorrected for multiple comparisons) were low PiB/APOE ε4 noncarrier versus high PiB/APOE ε4 carrier (p < 0.001) and high PiB/APOE ε4 noncarrier versus high PiB/APOE ε4 carrier (p = 0.03). There were 365 low PiB/APOE ε4 noncarriers, 74 low PiB/APOE ε4 carriers, 115 high PiB/APOE ε4 noncarriers, and 85 high PiB/APOE ε4 carriers. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CN, cognitively normal; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; PiB, 11C-Pittsburgh compound B; ROI, region of interest; SUVr, standardized uptake value ratio.

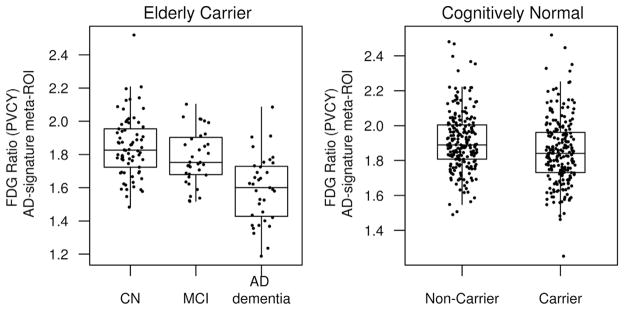

3.5. Comparison of the impact of APOE ε4 genotype and cognitive impairment on FDG ratios

We wished to characterize and contrast the impact of both the carriage of an APOE ε4 allele on reductions FDG ratio in CN participants and the magnitude of reductions in FDG ratio observed in persons with cognitive impairment. The mean reduction in FDG ratio in the AD-signature meta-ROI between persons with AD dementia versus matched CN participants was nearly 4 times larger than the APOE ε4 allele effect in CN carriers versus noncarriers (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Reductions in FDG ratio in patients with MCI due to AD were similar to the magnitude of the APOE ε4 difference in CN carriers versus noncarriers (Kantarci et al., 2010).

Fig. 4.

Boxplots of the FDG ratio (partial volume corrected [PVCY]) in the AD-signature meta-ROI among elderly (age ≥70 years) CN, MCI, and AD subjects and among CN APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers of all ages to demonstrate the relative AD dementia and APOE ε4 effects. AD dementia subjects who were APOE ε4 carriers and amyloid positive were matched to APOE ε4 carrier, amyloid positive MCI subjects, and APOE ε4 carrier CN subjects on age and sex. CN APOE ε4 carriers were matched on age and sex to APOE ε4 non-carriers. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CN, cognitively normal; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; ROI, region of interest.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of age- and sex-matched CN APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers and age- and sex-matched elderly CN, MCI, and AD APOE ε4 carriersa

| APOE ε4 carrier N = 209 | APOE ε4 noncarrier N = 209 | CN N = 70 | MCI N = 35 | AD dementia N = 35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 76 (71, 80) | 76 (71, 80) | 80 (76, 84) | 80 (76, 83) | 80 (75, 84) |

| Min, max | 31, 91 | 31, 91 | 71, 91 | 72, 88 | 71, 92 |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 117 (56) | 117 (56) | 38 (54) | 19 (54) | 19 (54) |

| Education, y | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 14 (12, 16) | 14 (12, 16) | 14 (12, 17) | 13 (12, 16) | 16 (12, 18) |

| Min, max | 8, 20 | 8, 20 | 8, 20 | 11, 20 | 8, 20 |

| AD-signature meta-ROI FDG ratio | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.85 (0.2) | 1.91 (0.2) | 1.85 (0.2) | 1.78 (0.2) | 1.59 (0.2) |

| APOE ε4 carrier versus | |||||

| MCI versusb | −0.062, p = 0.10 | ||||

| AD dementia versusb | −0.255, p < 0.001 | −0.193, p < 0.001 | |||

Key: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; CN, cognitively normal; FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; PET, positron emission tomography; PiB, 11C-Pittsburgh compound B; ROI, region of interest; SUVr, standardized uptake value ratio.

AD dementia, MCI, and CN participants are APOE ε4 carriers and age 70 or older. AD and MCI participants are also amyloid positive by PiB PET (SUVr > 1.5).

Mean differences in FDG ratios in AD signature meta-ROI with p-values from t-tests.

4. Discussion

Our findings can be summarized in 4 points. First, we demonstrated statistically significant, though modest, age-related decrements in FDG ratio in a number of frontal and parietal regions even with partial volume correction. Second, carriage of at least one APOE ε4 allele was associated with reductions in FDG ratio in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus and lateral parietal regions, including the AD-signature meta-ROI. The impact of carriage of one APOE ε4 allele versus none on FDG ratio in the AD signature region in cognitively normal individuals is about a quarter of the magnitude of that seen in AD dementia compared with age-matched normal. Third, FDG ratios in several regions including the AD signature meta-ROI were lower in APOE ε4 carriers across the age spectrum and showed no interaction with age. Fourth, the regional pattern of age-related FDG changes, APOE ε4-related FDG changes, and the changes occurring in AD dementia patients with elevated PiB retention have 2 loci in common: the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus and lateral parietal, even while the age-related changes were seen much more broadly throughout the brain. Thus, the pivotal role of these regions in the pathogenesis of AD may relate to their unique susceptibility to both aging and APOE ε4-related effects.

Decrements in glucose uptake per unit brain volume occurred as a function of age. Our sample size of CN individuals was much larger than prior studies (Ibanez et al., 2004; Kalpouzos et al., 2009; Kantarci et al., 2010; Yanase et al., 2005), which enabled us to detect declines with aging in the presence of considerable between-subject variability (Fig. 1). Declines in FDG ratio with age do not appear to be mediated by elevated brain amyloid levels, as the FDG declines appear to begin before the age of 60 years, well before there is appreciable accumulation of brain β-amyloid (Rodrigue et al., 2012; Rowe et al., 2010). The anatomic distribution of the age-related FDG declines was very broad but did not involve every region. The age-related pattern of regional declines in FDG ratio were widespread and therefore not simply a replica of that seen in AD. Further, the medial temporal lobe showed small age-related declines in FDG ratio. However, in contrast to a prior report (Kalpouzos et al., 2009), we found declines in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus FDG ratios that were comparable to declines seen in the frontal regions. Cognitively normal individuals who have reduced FDG ratios in the AD signature regions, along with elevations of brain amyloid are at increased risk for cognitive decline (Knopman et al., 2012).

There were notably large declines in FDG ratios in the putamen and thalamus with age, the relevance of which to cognitive aging or disease is not clear. In familial AD, volume loss occurs in the thalamus, suggesting that the region is involved in AD-related neuro-degeneration (Cash et al., 2013). To the best of our knowledge, changes in glucose metabolism in subcortical structures have not been described before.

We found reductions in FDG ratio with the possession of at least one APOE ε4 allele in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, lateral parietal, and an AD-signature meta-ROI that were not age-dependent (Fig. 2: there was a main effect of APOE ε4 but no age nor age × APOE ε4 interaction). Although we could not demonstrate reduced FDG ratios in our younger participants separately, the absence of age × APOE ε4 interaction suggests that the FDG changes, in fact, begin at a young age. One group, working with participants (aged 50–63 years) with a family history of AD dementia found the APOE ε4 heterozygotes exhibited declines over a 2 year interval in a number of cortical regions including ones in our AD signature meta-ROI (Reiman et al., 2001).

There was also no interaction between APOE ε4 carriage and PiB SUVr in our older participants, suggesting that the impact of APOE ε4 on FDG ratio was not simply mediated by β-amyloid burden. Rather, it appeared that amyloidosis and APOE ε4 carriage were additive in their impact on FDG hypometabolism. The separation in the mean FDG ratio values beginning in our youngest participants between ε4 carriers and noncarriers (as demonstrated by the lack of an age × APOE ε4 interaction) also suggests that brain amyloidosis was not mediating the impact of APOE ε4 carriage on FDG ratios. Some reports have found relative FDG hypermetabolism in association with amyloidosis in elderly normal individuals (Oh et al., 2014) or persons with MCI (Cohen et al., 2009). We did not observe absolute FDG hyper-metabolism in our elderly CN participants in relationship to amyloid status (Fig. 3). Such a phenomenon highlights the independence of the impact of APOE ε4 from amyloid burden on FDG.

Our findings are consistent with the assertion (Jagust et al., 2012) that the impact of APOE ε4 on glucose hypometabolism in the AD meta-ROI is not entirely because of amyloid deposition. Hypometabolism in the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus or lateral parietal regions in some asymptomatic persons may be expression of the role of APOE ε4 in neuronal function that is independent of its well-established relationship to amyloid deposition (Kok et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2010). Eventually, β-amyloidosis promotes worsening metabolic function in critical cortical regions (Knopman et al., 2013; Landau et al., 2012), but in young people decades before brain amyloid levels become elevated (Rodrigue et al., 2012), APOE ε4 genotype has a unique impact on cortical metabolism.

The large FDG hypometabolic changes in temporal, parietal, and posterior cingulate cortices in persons with AD dementia are well established (Chetelat et al., 2008; Mosconi, 2005; Nestor et al., 2003; Rabinovici et al., 2010). The magnitude of the FDG ratio declines in the AD-signature meta-ROI attributable to APOE ε4 carriage was about a quarter of that attributable to having AD dementia. Thus, while the regional predilection for the lateral parietal, posterior cingulate and/or precuneus, and AD-signature meta-ROI conferred by APOE ε4 carriage is strikingly similar to that of AD dementia, the magnitude is much smaller. The most parsimonious explanation is that excess decrement in metabolic efficacy in the AD signature regions caused by APOE ε4 carriage makes it that much easier for amyloid-related brain pathology to worsen cortical metabolism to a critical level and therefore confers risk for future cognitive decline.

Brain volume loss with advancing age in cognitively normal people is a consistently observed phenomenon (Bakkour et al., 2013; Fjell et al., 2013; Salat et al., 2004; Sowell et al., 2003). Structural imaging studies also show that some regions experience volume loss with aging, whereas the medial temporal lobe declines appear to be more specific for AD. Frontal and parietal cortex, in contrast, are susceptible to both aging and AD changes (Bakkour et al., 2013). Although brain atrophy and FDG ratio changes over the age spectrum are similar but not identical, it was beyond the scope of the current work to correlate structural imaging changes that occur with age to the metabolic changes. However, we were unable to ignore the confounding effect of brain volume loss in the current analyses, because the calculation of voxel-wise glucose metabolic rates are critically dependent upon excluding cerebro-spinal fluid in measured voxels.

The confluence of aging and genetic influences on the integrity of the precuneus and/or posterior cingulate cortex and its invariant involvement in AD (Minoshima et al., 1997; Nestor et al., 2003) is probably not a coincidence. The posterior cingulate has the highest rate of glucose metabolism at rest of any cortical region (Ivancevic et al., 2000), perhaps because of its role as one of the major hubs of the default mode network (Buckner et al., 2008). One of the principles of posterior cingulate physiology is that it tends to be tonically active (Raichle et al., 2001) but deactivates when mental effort is required. APOE ε4 carriers may be less efficient in deactivation during cognitive activity (Filippini et al., 2009). In CN elders, deactivation with mental effort also failed to occur (Lustig et al., 2003). A hypothesis is that a failure to deactivate in AD signature regions puts additional metabolic strain on the region. An alternative hypothesis is that the metabolic inefficiency because of carriage of APOE ε4 contributed to failure to deactivate. Moreover, the posterior cingulate and lateral temporal regions are also sites of high amyloid load (Jack et al., 2008; Rowe et al., 2007; Wolk et al., 2009). Finally, the posterior cingulate and/or precuneus (and the lateral parietal and inferior temporal regions) are well positioned to initiate or facilitate trans-synaptic propagation of amyloid- or tau-related neurodegeneration (de Calignon et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012) by virtue of their powerful interconnections with many other cortical regions.

In our prior work (Jack et al., 2012; Knopman et al., 2012) as well as in that of others (Landau et al., 2011), the cut-point for abnormal FDG PET was defined in relation to a demented group. There are advantages and disadvantages of that approach, the main disadvantage being that such a cut-point might be insensitive to pre-symptomatic alterations in brain glucose metabolism. The fact that a substantial fraction of AD dementia patients do not have abnormal FDG PET ratio (Lowe et al., 2013) raises another concern about defining a cut-point relative to dementia status. The discrepancy between a dementia-derived cut-point and a young normal cut-point has been shown for amyloid imaging (Mormino et al., 2012), for example. In young normal individuals, a cut-point for abnormal amyloid levels was far below the cut-point derived relative to AD dementia. Thus, one of the motivations for this analysis was to derive a cut-point for FDG ratio in some region or regions that was based on deviation from healthy youthful brains. However, the great variability in FDG ratio combined with the modest age-related changes make it unlikely that an abnormal FDG ratio can be defined with reference to normal aging. Instead, abnormal FDG ratio in the AD signature meta-ROI might need to be defined by the levels seen in persons with amyloid-positive AD dementia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P50 AG16574, U01 AG06786 and R01 AG11378, the Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum Family Foundation and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program of the Mayo Foundation. Dr Knopman took part in data collection, supervised analyses, generated the first and final drafts and takes overall responsibility for the data and the manuscript. Dr Jack took part in data collection, supervised analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Ms. Wiste performed analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript. Ms. Lundt performed analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript. Mr. Weigand performed analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Vemuri performed analyses of imaging data and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Lowe supervised collection of PET imaging, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Kantarci performed analyses of imaging data and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Gunter performed analyses of imaging data. Mr. Senjem performed analyses of imaging data. Dr Roberts critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Mielke critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Boeve took part in data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr Petersen obtained funding, took part in data collection and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors except the following authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr Knopman serves as Deputy Editor for Neurology; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lilly Pharmaceuticals; will serve on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study; served as a consultant to TauRx Pharmaceuticals, was an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Baxter and TauRX Pharmaceuticals in the past 2 years; and receives research support from the NIH. Dr Jack serves on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer, Elan and/or Janssen AI, Eli Lilly & Company, GE Healthcare; receives research support from Baxter International Inc, Allon Therapeutics, Inc, the NIH and/or NIA, and the Alexander Family Alzheimer’s Disease Research Professorship of the Mayo Foundation; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Dr Mielke receives research grants from the NIH/NIA, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, Lewy Body Association, and the Driskill Foundation. Dr Lowe serves on scientific advisory boards for Bayer Schering Pharma and receives research support from GE Healthcare, Siemens Molecular Imaging, AVID Radio-pharmaceuticals, and the NIH (NIA, NCI). Dr Kantarci receives research grants from the NIH/NIA. Dr Roberts receives research support from Abbvie Health and Economics Outcomes Research and from the NIH/NIA. Dr Boeve receives royalties from the publication of Behavioral Neurology of Dementia and receives research support from Cephalon, Inc, Allon Therapeutics, GE Healthcare, the NIH/NIA, and the Mangurian Foundation. Dr Petersen serves on scientific advisory boards for Pfizer, Inc, Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy, Elan Pharmaceuticals, and GE Healthcare; receives royalties from the publication of Mild Cognitive Impairment (Oxford University Press, 2003); and receives research support from the NIH/NIA.

References

- Albert M, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman H, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman D, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Phelps CH. The Diagnosis of Mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Demen J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkour A, Morris JC, Wolk DA, Dickerson BC. The effects of aging and Alzheimer’s disease on cerebral cortical anatomy: specificity and differential relationships with cognition. Neuroimage. 2013;76:332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash DM, Ridgway GR, Liang Y, Ryan NS, Kinnunen KM, Yeatman T, Malone IB, Benzinger TL, Jack CR, Jr, Thompson PM, Ghetti BF, Saykin AJ, Masters CL, Ringman JM, Salloway SP, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Cairns NJ, Marcus DS, Xiong C, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Ourselin S, Fox NC. The pattern of atrophy in familial Alzheimer disease: volumetric MRI results from the DIAN study. Neurology. 2013;81:1425–1433. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a841c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetelat G, Desgranges B, Landeau B, Mezenge F, Poline JB, de la Sayette V, Viader F, Eustache F, Baron JC. Direct voxel-based comparison between grey matter hypometabolism and atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2008;131:60–71. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AD, Price JC, Weissfeld LA, James J, Rosario BL, Bi W, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Snitz BE, Aizenstein HA, Wolk DA, Dekosky ST, Mathis CA, Klunk WE. Basal cerebral metabolism may modulate the cognitive effects of Abeta in mild cognitive impairment: an example of brain reserve. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14770–14778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3669-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suarez-Calvet M, William CM, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, Pitstick R, Sahara N, Ashe KH, Carlson GA, Spires-Jones TL, Hyman BT. Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2012;73:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF, Mackay CE. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell AM, McEvoy L, Holland D, Dale AM, Walhovd KB. Brain changes in older adults at very low risk for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2013;33:8237–8242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5506-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter JL, Bernstein MA, Borowski BJ, Ward CP, Britson PJ, Felmlee JP, Schuff N, Weiner M, Jack CR. Measurement of MRI scanner performance with the ADNI phantom. Med Phys. 2009;36:2193–2205. doi: 10.1118/1.3116776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Salmon E, Perani D, Baron JC, Holthoff V, Frolich L, Schonknecht P, Ito K, Mielke R, Kalbe E, Zundorf G, Delbeuck X, Pelati O, Anchisi D, Fazio F, Kerrouche N, Desgranges B, Eustache F, Beuthien-Baumann B, Menzel C, Schroder J, Kato T, Arahata Y, Henze M, Heiss WD. Discrimination between Alzheimer dementia and controls by automated analysis of multicenter FDG PET. Neuroimage. 2002;17:302–316. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez V, Pietrini P, Furey ML, Alexander GE, Millet P, Bokde AL, Teichberg D, Schapiro MB, Horwitz B, Rapoport SI. Resting state brain glucose metabolism is not reduced in normotensive healthy men during aging, after correction for brain atrophy. Brain Res Bull. 2004;63:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivancevic V, Alavi A, Souder E, Mozley PD, Gur RE, Benard F, Munz DL. Regional cerebral glucose metabolism in healthy volunteers determined by fluordeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: appearance and variance in the transaxial, coronal, and sagittal planes. Clin Nucl Med. 2000;25:596–602. doi: 10.1097/00003072-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MC, Trojanowski JQ. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, Roberts RO, Rocca WA, Boeve BF, Petersen RC. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:765–775. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, Shiung MM, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Petersen RC. 11C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2008;131:665–680. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, O’Brien PC, Rettman DW, Shiung MM, Xu Y, Muthupillai R, Manduca A, Avula R, Erickson BJ. FLAIR histogram segmentation for measurement of leukoaraiosis volume. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:668–676. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust WJ, Landau SM. Apolipoprotein E, not Fibrillar beta-amyloid, Reduces cerebral glucose metabolism in Normal aging. J Neurosci. 2012;32:18227–18233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3266-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpouzos G, Chetelat G, Baron JC, Landeau B, Mevel K, Godeau C, Barre L, Constans JM, Viader F, Eustache F, Desgranges B. Voxel-based mapping of brain gray matter volume and glucose metabolism profiles in normal aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Petersen RC, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Shiung MM, Whitwell JL, Negash S, Ivnik RJ, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Smith GE, Jack CR., Jr Hippocampal volumes, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolites, and cerebrovascular disease in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1621–1628. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.12.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Senjem ML, Lowe VJ, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, Frank AR, Shiung MM, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Effects of age on the glucose metabolic changes in mild cognitive impairment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:1247–1253. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem M, Ivnik RJ, Roberts RO, Boeve BF, Petersen RC. Short-term Clinical Outcomes for Stages of NIA-AA pre-clinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1576–1582. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182563bbe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Jack CR, Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Mielke MM, Roberts RO, Boeve BF, Petersen RC. Selective Worsening of brain Injury Biomarker Abnormalities in cognitively Normal elderly with β-amyloidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1030–1038. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok E, Haikonen S, Luoto T, Huhtala H, Goebeler S, Haapasalo H, Karhunen PJ. Apolipoprotein E-dependent accumulation of Alzheimer disease-related lesions begins in middle age. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:650–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1207–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, Koeppe RA, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2012;72:578–586. doi: 10.1002/ana.23650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Drouet V, Wu JW, Witter MP, Small SA, Clelland C, Duff K. Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031302. Epub 2012 Feb 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loessner A, Alavi A, Lewandrowski KU, Mozley D, Souder E, Gur RE. Regional cerebral function determined by FDG-PET in healthy volunteers: normal patterns and changes with age. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopresti BJ, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Hoge JA, Ziolko SK, Lu X, Meltzer CC, Schimmel K, Tsopelas ND, DeKosky ST, Price JC. Simplified quantification of Pittsburgh Compound B amyloid imaging PET studies: a comparative analysis. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1959–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe VJ, Peller PJ, Weigand SD, Montoya Quintero C, Tosakulwong N, Vemuri P, Senjem ML, Jordan L, Jack CR, Jr, Knopman D, Petersen RC. Application of the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association AD criteria to ADNI. Neurology. 2013;80:2130–2137. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318295d6cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Snyder AZ, Bhakta M, O’Brien KC, McAvoy M, Raichle ME, Morris JC, Buckner RL. Functional deactivations: change with age and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14504–14509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235925100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJ, Kawas CH, Klunk WE. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s Demen J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamee RL, Yee SH, Price JC, Klunk WE, Rosario B, Weissfeld L, Ziolko S, Berginc M, Lopresti B, Dekosky S, Mathis CA. Consideration of optimal time window for Pittsburgh compound B PET summed uptake measurements. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:348–355. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer CC, Cantwell MN, Greer PJ, Ben-Eliezer D, Smith G, Frank G, Kaye WH, Houck PR, Price JC. Does cerebral blood flow decline in healthy aging? A PET study with partial-volume correction. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1842–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Giordani B, Berent S, Frey KA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. Metabolic reduction in the posterior cingulate cortex in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:85–94. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino EC, Brandel MG, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Marks S, Baker SL, Jagust WJ. Not quite PIB-positive, not quite PIB-negative: Slight PIB elevations in elderly normal control subjects are biologically relevant. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1152–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:122–131. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi L. Brain glucose metabolism in the early and specific diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. FDG-PET studies in MCI and AD. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:486–510. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor PJ, Fryer TD, Smielewski P, Hodges JR. Limbic hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:343–351. doi: 10.1002/ana.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Habeck C, Madison C, Jagust W. Covarying alterations in Abeta deposition, glucose metabolism, and gray matter volume in cognitively normal elderly. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:297–308. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RC, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Rocca WA. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men than in women. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010;75:889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JC, Klunk WE, Lopresti BJ, Lu X, Hoge JA, Ziolko SK, Holt DP, Meltzer CC, DeKosky ST, Mathis CA. Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1528–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, Alkalay A, Racine CA, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Baker SL, Agarwal N, Bonasera SJ, Mormino EC, Weiner MW, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rosen HJ, Miller BL, Jagust WJ. Increased metabolic vulnerability in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease is not related to amyloid burden. Brain. 2010;133:512–528. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Chen K, Alexander GE, Bandy D, Frost J. Declining brain activity in cognitively normal apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 heterozygotes: a foundation for using positron emission tomography to efficiently test treatments to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3334–3339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061509598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Yun LS, Chen K, Bandy D, Minoshima S, Thibodeau SN, Osborne D. Preclinical evidence of Alzheimer’s disease in persons homozygous for the epsilon 4 allele for apolipoprotein E. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:752–758. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman D, Cha R, Pankratz VS, Boeve B, Ivnik R, Tangalos E, Petersen RC, Rocca WA. The Mayo Clinic study of aging: Design and Sampling, Participation, Baseline measures and Sample Characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Rocca WA, Petersen RC. The incidence of MCI differs by subtype and is higher in men: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2012;78:342–351. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182452862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Sr, Rieck JR, Hebrank AC, Diaz-Arrastia R, Mathews D, Park DC. beta-Amyloid burden in healthy aging: regional distribution and cognitive consequences. Neurology. 2012;78:387–395. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245d295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, Bourgeat P, Pike KE, Jones G, Fripp J, Tochon-Danguy H, Morandeau L, O’Keefe G, Price R, Raniga P, Robins P, Acosta O, Lenzo N, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Head R, Martins R, Masters CL, Ames D, Villemagne VL. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, Gong SJ, Pike K, Savage G, Cowie TF, Dickinson KL, Maruff P, Darby D, Smith C, Woodward M, Merory J, Tochon-Danguy H, O’Keefe G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Masters CL, Villemagne VL. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:1718–1725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salat DH, Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Greve DN, Desikan RS, Busa E, Morris JC, Dale AM, Fischl B. Thinning of the cerebral cortex in aging. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:721–730. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:309–315. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk DA, Price JC, Saxton JA, Snitz BE, James JA, Lopez OL, Aizenstein HJ, Cohen AD, Weissfeld LA, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Dekoskym ST. Amyloid imaging in mild cognitive impairment subtypes. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:557–568. doi: 10.1002/ana.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanase D, Matsunari I, Yajima K, Chen W, Fujikawa A, Nishimura S, Matsuda H, Yamada M. Brain FDG PET study of normal aging in Japanese: effect of atrophy correction. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:794–805. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]