Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE), a prevalent hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, is believed to be secondary to uteroplacental ischemia. Accumulating evidence indicates that hypoxia-independent mediators, including inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, are associated with PE, but it is unclear whether these signals directly contribute to placental damage and disease development in vivo. We report that LIGHT, a novel TNF superfamily member, is significantly elevated in the circulation and placentas of preeclamptic women compared to normotensive pregnant individuals. Injection of LIGHT into pregnant mice induced placental apoptosis, small fetuses and key features of PE-hypertension and proteinuria. Mechanistically, using neutralizing antibodies specific for LIGHT receptors, we found that the LIGHT receptors, herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM) and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR), are required for LIGHT-induced placental impairment, small fetuses and PE features in pregnant mice. Accordingly, we further revealed that LIGHT functions through these two receptors to induce secretion of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and endothelin-1 (ET-1), two well-accepted pathogenic factors in PE, and thereby plays an important role in hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice. Lastly, we extended our animal findings to human studies and demonstrated that activation of LIGHT receptors resulted in increased apoptosis and elevation of sFlt-1 secretion in human placental villous explants. Overall, our human and mouse studies show that LIGHT signaling is a previously unrecognized pathway responsible for placental apoptosis, elevated secretion of vasoactive factors and subsequent maternal features of PE and reveal new therapeutic opportunities for the management of disease.

Keywords: LIGHT, TNF superfamily 14, preeclampsia, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1, endothelin-1, lymphotoxin β receptor, herpes virus entry mediator

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a life-threatening pregnancy complication that affects approximately 7% of first pregnancies and accounts for more than 50,000 maternal deaths worldwide each year 1. The major features of PE are hypertension, proteinuria, and placenta and kidney damage1, 2. It is also a leading cause of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), a life-threatening condition that puts the fetus at risk for many long term cardiovascular disorders3, 4. Thus, PE is a leading cause of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity and has acute and long-term impact on both moms and babies. Despite intense research efforts, the underlying molecular mechanisms of PE are poorly understood and the clinical management of PE is unsatisfactory resulting from the lack of pre-symptomatic screening, reliable diagnostic tests and effective therapy. Thus, the identification of specific factors and signaling pathways involved in the pathogenesis of PE will facilitate the development of specific pre-symptomatic tests and effective mechanism-based preventative and therapeutic strategies for the disease.

Disease symptoms generally abate following delivery, suggesting that the placenta plays a central role in this disease. It is widely accepted that hypoxia is an initial trigger to induce placenta abnormalities, elevated secretion of vasoactive factors and subsequent maternal features5. This concept is strongly supported by animal studies showing that experimentally reduced uterine perfusion pressure (RUPP) in pregnant rats results in abnormal placentas, increased secretion of anti-angiogenic factors and key preeclamptic features including hypertension and kidney damage2. However, recent studies have provided compelling evidence that various factors other than uteroplacental hypoxia also promote placental abnormalities and disease progression: these include inflammatory cytokines6, growth factors7, components of the complement cascade8, and autoantibodies9. A growing body of evidence indicates that an increased inflammatory response is associated with PE and may contribute to disease2, 6. For example, previous in vitro studies showed that TNF-α and IFNγ induce trophoblast apoptosis10, and that IFNγ and IL-12 inhibit angiogenesis11. Moreover, early in vitro studies indicated that TNF-α contributes to elevated secretion of the anti-angiogenic factor, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), from cultured human villous explants12. Elevated sFlt-1 likely leads to impaired placentation, decreased uteroplacental perfusion and subsequent hypertension and kidney injury. Despite these accumulating data, the specific hypoxia-independent mediators and mechanisms underlying placental apoptosis, enhanced secretion of vasoactive factors and progression of the disease have not been fully determined in vivo. Therefore, this study aims to identify the pathological role of novel hypoxia-independent mediators in PE and the underlying mechanisms of disease pathogenesis.

LIGHT, TNF superfamily 14, is a type II transmembrane protein containing a C-terminal TNF homology domain that folds into a β-sheet sandwich and assembles into a homotrimer13. It is found on immature dendritic cells and activated T cells and like many TNF superfamily ligands, LIGHT is not only anchored on the cell surface, but is also secreted from cells14. In both humans and rodents, LIGHT is an immune signaling molecule functioning via two specific cellular receptors, lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) and herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM)15. Additionally, decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) is a soluble form of LIGHT receptor, present in humans but not mice. Numerous studies indicated that DcR3 functions as an immune-suppressor in cancer16, inflammation17 and transplantation18. Importantly, LIGHT has emerged as a key factor involved in multiple conditions, including hepatitis19, asthma20, atherosclerosis21, rheumatoid arthritis22, and Crohn’s disease23. Although LIGHT and its receptors are expressed in placentas, especially located in trophoblast cells and endothelial cells24–26, nothing is known about the role of LIGHT in PE. In the present study, we revealed that LIGHT is substantially elevated in the circulation and placentas of preeclamptic women and elevated LIGHT signaling via its receptors, LTβR and HVEM, directly triggers placental apoptosis, secretion of vasoactive factors including sFlt-1 and endothelin-1 (ET-1), subsequent maternal symptom development and small fetuses in vivo. Additionally, we provide evidence that LIGHT-mediated activation of its receptors directly induces apoptosis and secretion of sFlt-1 from cultured human placental villous explants. These results reveal a previously unrecognized role of LIGHT signaling in pathogenesis of PE and immediately suggest novel therapeutic possibilities for the disease.

Materials and Methods

For additional Materials and Methods see Online Supplement

Patients

Patients admitted to Memorial Hermann Hospital were identified by the obstetrics faculty of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Preeclamptic patients (n=36) were diagnosed with severe disease on the basis of the definition set by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report27. The criteria of inclusion, including no previous history of hypertension, are reported previously28–30 and include the presence of blood pressure ≥ 160/110 mmHg and urinary protein ≥300 mg in a 24-hour period or a dipstick value of ≥1. Other criteria included the presence of persistent headache, visual disturbances, epigastric pain, or the hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome in women with blood pressure of ≥140/90 mmHg. Control pregnant women were selected on the basis of having an uncomplicated, normotensive pregnancy with a normal term delivery (n=34). The research protocol was approved of by the Institutional Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. The detailed information of human subjects is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic features of human subjects

| Clinical Characteristics | NT | Severe PE |

|---|---|---|

| n | 34 | 36 |

| Age (y) | 29.6 ± 5.8 | 28.7 ± 8.6 |

| Race (%) African American | 43 | 48 |

| White | 27 | 22 |

| Hispanic | 29 | 28 |

| Other | 1 | 2 |

| Gravity | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.6± 1.5 |

| BMI | 32.8± 4.7 | 36.6 ± 8.6 |

| Weeks gestational age | 37.2 ± 2.8 | 31.9 ± 6.4 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 115.7 ± 6 | 174.2 ± 7* |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 72.8 ± 5.7 | 98.8 ± 10.7* |

| Proteinuria (mg/24h) | ND | 1809 ± 465* |

This table illustrates that the blood pressure and proteinuria are elevated in severe preeclamptic (PE) women, as compared to normotensive (NT) pregnant women. The category mean is indicated (± SEM, where applicable).

P<0.001 vs normotensive pregnant women. ND: not determined.

Introduction of recombinant mouse LIGHT and neutralizing antibodies against LTβR or HVEM into pregnant and non-pregnant mice

Pregnant C57Bl/6J mice (Harlan) were anesthetized with isofluorane, and recombinant mouse LIGHT (2ng, R&D Systems) or the same volume of saline were introduced into pregnant mice by retro-orbital sinus injection on embryonic day (E) 13.5 and E14.5 (LIGHT: n=10; saline: n=8). For neutralization experiments, either LTβR mAb (100μg; n=6) or LTβR mAb (100μg; n=6), was simultaneously coinjected with LIGHT. Some of the mice (n=5) were injected with the IgG from rat as control. This dosage was adapted from Anand et al.19. Moreover, blood pressure and proteinuria of some of the pregnant mice with saline or LIGHT injection were further monitored on postpartum day 5 and day 10 (n=5–6). The same amount of LIGHT and saline were also injected into non-pregnant mice (LIGHT: n=8; saline: n=6). Some mice injected with LIGHT were co-injected with LTβR mAb (100μg; n=4) or LTβR mAb (100μg; n=4) as with pregnant mice. IgG from rat was also used as control (n=4). All protocols involving animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Houston Health Science Center.

Human placental villous explant collection and culture

Human placentas were obtained from normotensive patients who underwent an elective term cesarean section at Memorial Hermann Hospital in Houston. The explant culture system was conducted as before7,11. On delivery, the placentas were placed on ice and submerged in phenol red-free DMEM containing 10% BSA and 1.0% antibiotics. 5 to 7 chorionic villous explant fragments were carefully dissected from the placenta and transferred to 24-well plates at 37°C and 5% CO2. All of the initial processing occurred within 30 minutes of delivery. The explants were incubated with recombinant human LIGHT (100pg/ml, R&D Systems), and co-treated with recombinant human DcR3 (4μg/ml, R&D Systems) or human IgG1-Fc (4μg/ml, R&D Systems)13. After 24 hours, the collection medium was siphoned and stored at −80°C, and the villous explants were lysed or fixed overnight in 10% formalin for embedding in paraffin wax for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m. All data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Newman Keuls post hoc test or student’s t-test to determine the significance of differences among groups. Statistical programs were run by GraphPad Prism 5 statistical software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Circulating LIGHT levels and expression profiles of its receptors in the placental tissue of preeclamptic patients and normotensive pregnant women

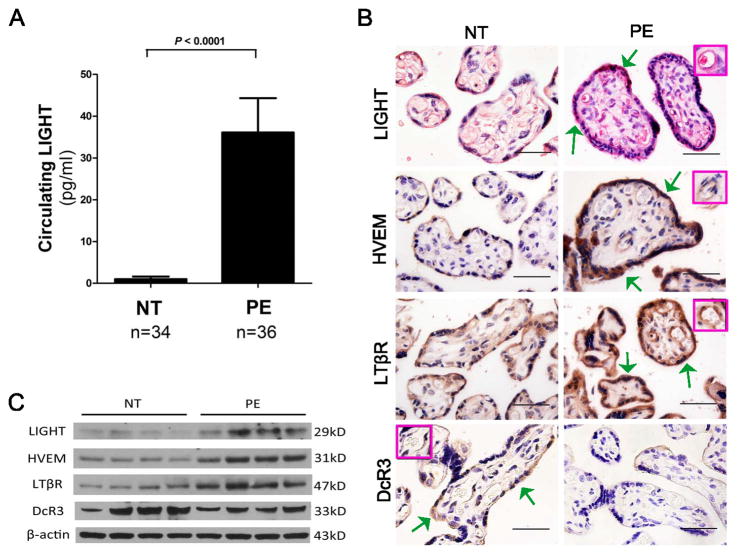

To determine the levels of LIGHT in the circulation of normotensive pregnant women and those with preeclampsia, we used a sensitive ELISA. We found that circulating LIGHT levels were increased 36-fold in women with PE compared to controls (Figure 1A). Additionally, we investigated the expression of LIGHT in human placental tissue using immunohistochemistry and detected LIGHT in trophoblast cells and endothelial cells, two major functional cell types of the placenta (Figure 1B). Quantitative RT-PCR showed that LIGHT mRNA was significantly elevated in the placentas from PE patients (Figure S1) and Western blotting analysis indicated that LIGHT protein is more abundant in placentas of preeclamptic patients compared to controls (Figure 1C). Overall, we demonstrated that the placental mRNA and protein of LIGHT and circulating LIGHT were elevated in preeclamptic patients.

Figure 1. Circulating levels of LIGHT and placental expression profiles of LIGHT and its receptors in women with normotensive and PE pregnancies.

(A) LIGHT levels were significantly increased in the circulation of preeclamptic patients (n=36) compared with normotensive pregnant women (n=34, P < 0.0001). (B) Localization of LIGHT and its receptors in the placentas was determined by immunohistochemistry. LIGHT and three receptors LTβR, HVEM and DcR3 were all present in human placental tissue-trophoblast cells (green arrows) and endothelial cells (inset box); (Scale bar = 100μm). (C) Western blotting revealed that protein levels of LIGHT and its transmembrane receptors LTβR and HVEM were elevated in placental tissue from preeclamptic patients (n=4) compared to normotensive pregnant women (n=4). However, the protein level of decoy receptor DcR3 was decreased in the placental tissue of pleeclamptic patients.

Next, we examined the localization and expression profiles of all three receptors for LIGHT. Similar to LIGHT, we found all of these three receptors are expressed in human placenta trophoblast cells and endothelial cells (Figure 1B). The protein levels of LTβR and HVEM were significantly increased in placental tissue from PE patients compared with normotensive pregnant women (Figure 1C). In contrast, the level of DcR3, a decoy receptor for LIGHT, was decreased in placenta tissue from PE patients relative to placenta tissue from normotensive pregnant women (Figure 1C).

LIGHT induces placental tissue apoptosis and reduced fetal weight in pregnant mice signaling via LTβR and HVEM

To evaluate the pathogenic role of elevated LIGHT in placental apoptosis, we injected recombinant mouse LIGHT into C57/BL6 pregnant mice on embryonic days (E) 13.5 and 14.5 to achieve blood concentrations similar to that seen in preeclamptic women. At the end of pregnancy, we evaluated the circulating levels of LIGHT, placental size and analyzed the histology of the placentas in the LIGHT injected and saline injected pregnant mice. We used an ELISA to accurately measure circulating LIGHT levels in the pregnant mice on E18.5 after injection with LIGHT. We found that the circulating level of LIGHT was approximately 150 pg/ml in LIGHT-injected pregnant mice vs 90 pg/ml in saline-injected pregnant mice on E18.5 (Figure S2).

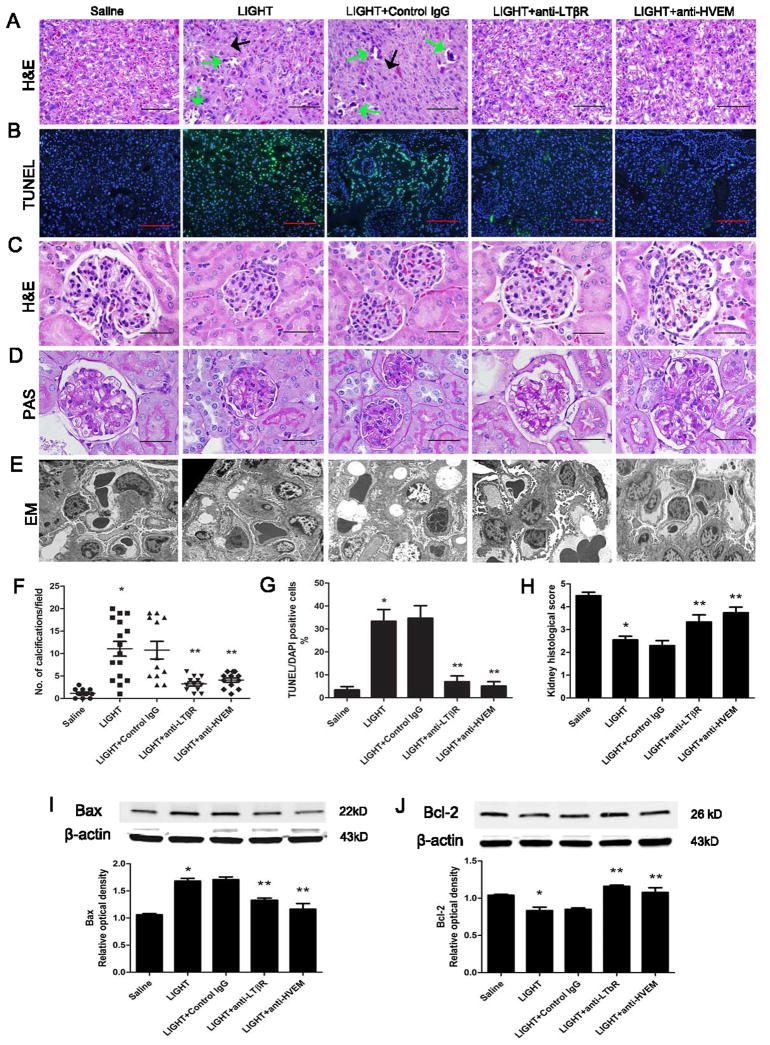

Next, we found that the placentas from pregnant mice injected with LIGHT were significantly smaller (0.0832±0.0026 g) than placentas from control pregnant mice injected with same volume of saline (0.1016±0.0018 g) (Table 2). Placenta H&E staining showed LIGHT injected pregnant mice had significant tissue damage, including increased calcification (Figure 2A, B&F). To determine whether increased placental tissue apoptosis is a potential underlying mechanism of LIGHT-induced small placental size and placental tissue damage, we performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) to detect apoptotic cells and demonstrated significantly increased apoptosis in the labyrinth zone of placentas from LIGHT injected pregnant mice compared to placentas from control mice (Figure 2B&G). Additionally, increased placental apoptosis in LIGHT injected pregnant mice was accompanied by an elevated level of Bax, a pro-apoptotic marker, and a decreased level of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic marker (Fig. 2I&J).

Table 2.

Mouse placenta and fetal weight:

| Variable | Placental weight (g) | Fetal weight (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Saline | 0.1016 ± 0.0018 | 1.02 ± 0.02 |

| LIGHT | 0.0832 ± 0.0026* | 0.85 ± 0.02* |

| LIGHT + Control IgG | 0.0823 ± 0.0024* | 0.86 ± 0.01* |

| LIGHT + anti-LTβR | 0.0914 ± 0.0024+ | 0.92 ± 0.04+ |

| LIGHT + anti-HVEM | 0.0907 ± 0.0025+ | 0.96 ± 0.06+ |

This table illustrates that injection of mouse recombinant LIGHT resulted in placentas and fetuses weighing less than pregnant mice injected with saline. Only pups born in litters of six to eight were analyzed, and those depicted in the figure were selected from the center of the uterine horn (N=51–60, collected and analyzed in four independent experiments).

P < 0.05 versus saline treatment;

P < 0.05 versus LIGHT treatment.

Figure 2. LIGHT-induced placental damage, apoptosis and kidney injury in pregnant mice by activation of LTβR and HVEM.

(A) Placentas assessed by H&E staining indicated that LIGHT-injected pregnant mice had damaged placentas: calcifications (green arrows) and fibrotic areas (black arrows). Co-injection of neutralizing antibodies to LTβR or HVEM significantly attenuated placental damage (scale bar=100μm). (B) Placental apoptosis was assessed by TUNEL staining (×10 magnification; green, TUNEL-positive cells; blue, DAPI nuclear stain; scale bar: 1 mm). LIGHT injected pregnant mice had increased apoptosis in the labyrinth zones of their placentas as compared with saline-injected animals. (C–E) Kidneys assessed by H&E staining (C), PAS staining (D) and EM studies (E) indicated that LIGHT-injected pregnant mice had damaged kidneys with typical endotheliosis with decreased capillary lumens with swollen endothelial cells. Co-injection of neutralizing antibodies to LTβR or HVEM significantly attenuated kidney injury (scale bar=100μm). (F) An arbitrary histological quantification of the number of calcifications obtained per field under ×10 magnification (12 placentas for each group). (G) Quantification of the TUNEL assay indicated elevation of the TUNEL-positive cells in the placenta of the mice injected with LIGHT. Co-injection of neutralizing antibodies for LTβR or HVEM reduced the TUNEL-positive cells in the placentas as compared with the LIGHT injected animals (n=10 placentas per variable, from 5 different mice in each group). (H) Kidney histological score in pregnant mice was significantly increased with LIGHT injection. Co-injection of neutralizing antibodies to LTβR or HVEM significantly reduced the kidney histological score. (I–J) Western blot analysis of mouse placentas indicated that LIGHT injection led to increased pro-apoptotic protein Bax (I) and decreased anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (J); n=5 for each variable collected over four independent experiments. Co-injection of neutralizing antibodies for LTβR or HVEM significantly reduced LIGHT-induced apoptotic features. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus saline injected pregnant mice; ** P < 0.05 versus LIGHT injected pregnant mice.

Because DcR3 is not expressed in rodents, we investigated the importance of LTβR and HVEM for LIGHT-induced placental damage featured with apoptosis in pregnant mice by injecting neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to each receptor into LIGHT-injected pregnant mice. We found that blocking either LTβR or HVEM by specific neutralizing antibodies restored placental size to 0.0914±0.0024 g and 0.0907±0.0025 g respectively (Table 2). In addition, co-treatment of LIGHT injected mice with either anti-LTβR mAb or anti-HVEM mAb significantly attenuated LIGHT-induced placental tissue damage, apoptosis, and elevation of Bax and reduction of Bcl-2 (Figure 2A, B, F, I&J).

Fetal development is dependent on normal placental formation, thus, we were not surprised to find that infusion of LIGHT into pregnant mice resuted in reduced fetal weight and that co-injection of neutralizing antibodies to HVEM or LTβR improved fetal weight (Table 2). Taken together, these findings provide in vivo evidence that elevated LIGHT is a previously unrecognized factor underlying placental apoptosis and reduced fetal weight in pregnant mice by activation of its membrane receptors.

Injection of LIGHT into pregnant mice induces maternal features of PE via HVEM and LTβR signaling

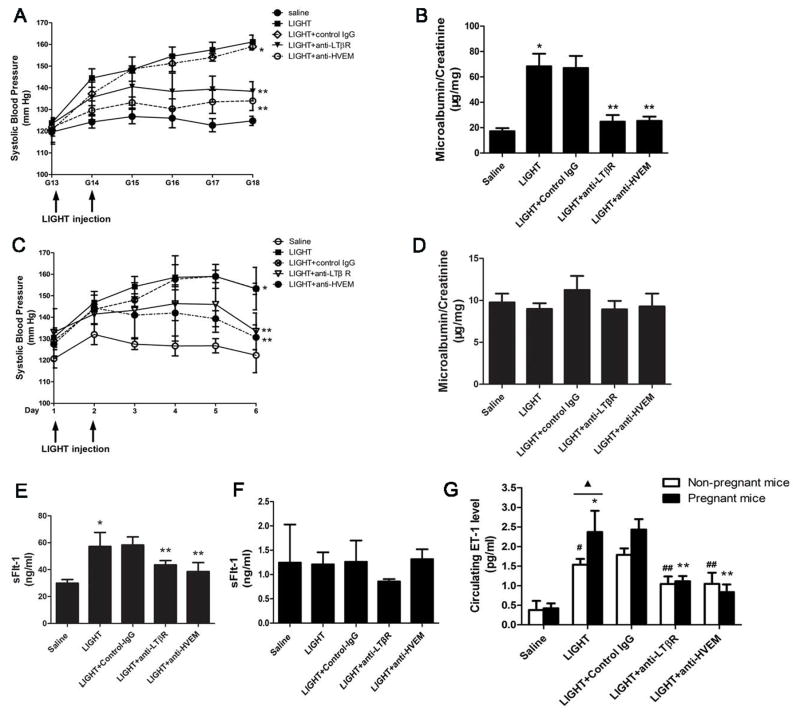

To evaluate the pathogenic role of elevated LIGHT in maternal disease development, we injected recombinant mouse LIGHT into pregnant C57/BL6 mice on E13.5 and E14.5 as described above. Blood pressure was monitored daily and 24 hour urine was collected for urinary protein measurement before we sacrificed the mice on E18.5. We found that systolic blood pressure increased significantly in mice injected with LIGHT (161±3mmHg) relative to control mice injected with saline (125±2mmHg, P<0.001) (Figure 3A). Additionally, we examined injected mice for proteinuria, another major clinical feature of PE. The ratio of urinary albumin:creatinine was significantly increased in pregnant mice injected with LIGHT (68±9.9 μg albumin/mg creatinine) compared to control mice (17±2.4 μg albumin/mg creatinine, P<0.01) (Figure 3B). Similar to women with PE, we found that on day 5 postpartum, both hypertension and proteinuria were substantially reduced (Figure S3A–B). Furthermore, we found that the decrease in blood pressure and proteinuria postpartum is associated with reduced circulating LIGHT and sFlt-1 levels (Figure S3C–D). Thus, these results indicate that increased circulating LIGHT contributes to hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice and decreased PE features postpartum is likely due to decreased LIGHT and sFlt-1 secretion from placentas.

Figure 3. LIGHT signaling through LTβR and HVEM induced hypertension and proteinuria in the pregnant mice by increasing both sFlt-1 and ET-1 secretion. However, LIGHT only induced hypertension but not proteinuria in non-pregnant mice by increasing secretion of ET-1 and not sFlt-1.

(A–B) Pregnant mice were injected with saline or LIGHT with or without injection of neutralizing antibodies for LTβR and HVEM, respectively. LIGHT injection resulted in hypertension (A) and proteinuria (B) in pregnant mice. Neutralizing antibodies for LTβR or HVEM significantly reduced hypertension seen in these mice (* P<0.001 versus saline injected mice; ** P<0.01 versus LIGHT injected mice). (C–D) LIGHT induced only hypertension (C) but not proteinuria (D) in non-pregnant mice. Neutralizing antibodies for LTβR or HVEM significantly attenuated hypertension in these mice (n=5–7). (* P<0.01 versus saline injected mice; ** P<0.05 versus LIGHT injected mice). (E–F) Circulating sFlt-1 level was significantly increased in LIGHT-injected pregnant mice (E) but not in non-pregnant mice (F). Neutralizing antibodies for LTβR and HVEM significantly attenuated LIGHT-induced sFlt-1 production in pregnant mice (E) but had no effect on the low sFlt-1 levels in non-pregnant mice (F). (G) Circulating ET-1 levels were remarkably elevated in LIGHT-injected pregnant and non-pregnant mice; and the LIGHT-mediated increase of circulating ET-1 in pregnant mice was significantly higher than that of non-pregnant mice (▲P<0.05). Neutralizing antibodies for LTβR or HVEM significantly attenuated LIGHT induced ET-1 production in pregnant mice and non-pregnant mice (*P<0.05 versus saline injected pregnant mice; ** P < 0.05 versus to LIGHT injected pregnant mice; #P<0.05 versus saline injected non-pregnant mice; ##P<0.05 versus LIGHT injected non-pregnant mice). Control rat IgG had no effect on LIGHT induced hypertension, proteinuria or sFlt-1 and ET-1 production.

Next, we examined whether LIGHT-induced hypertension and proteinuria is dependent on activation of its receptors in pregnant mice by injecting neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to each receptor into LIGHT-injected pregnant mice. The results (Figure 3A) show that the presence of anti-LTβR mAb or anti-HVEM mAb significantly inhibited LIGHT-induced hypertension (161±3 mmHg in the LIGHT injected group versus 138±4 mmHg in the LIGHT plus anti-LTβR treated group (P<0.01) and 134±5 mmHg in the LIGHT plus anti-HVEM treated group, P<0.01). Additionally, we found that elevated urinary protein levels seen in LIGHT injected pregnant mice (68±9.9μg albumin/mg creatine) were significantly attenuated by infusion of anti-LTβR mAb (25±5.2μg albumin/mg creatinine, P<0.05) or anti-HVEM mAb (25±3.3μg albumin/mg creatinine, P<0.05) (Figure 3B). Thus, we have provided in vivo evidence that elevated LIGHT coupled with HVEM and LTβR signaling leads to key preeclamptic features including hypertension and proteinuria.

Additionally, to determine whether LIGHT, signaling via LTβR and HVEM, also contributes to renal damage, kidneys were harvested on E18.5 from LIGHT and saline-injected pregnant mice for histological analysis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed narrowing of Bowman’s capsule and loss of capillary space in the majority of glomeruli of LIGHT-injected pregnant mice (Figure 2C). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining further demonstrated decreased capillary lumens and narrowed Bowman’s capsule are caused by the extensive endothelial cell swelling but not the thickening of basement membrane (Figure 2D). The kidneys of pregnant mice injected with saline rarely showed signs of glomerular damage. Blocking LTβR or HVEM by neutralizing antibodies prevented the renal abnormalities in the mice that resulted from injection with LIGHT (Figure 2C–D). Histomorphometric analysis showed that the extent of glomerular damage was significantly greater in LIGHT-injected pregnant mice compared to that in saline-injected pregnant mice and that anti-LTβR or anti-HVEM treatment resulted in improved renal histology in LIGHT-injected mice (Figure 2H). Thus, LTβR and HVEM signaling both contribute to LIGHT-induced renal damage in pregnant mice.

To validate the kidney injury, we conducted electron microscopic (EM) studies. EM studies revealed that kidney tissue from pregnant mice injected with LIGHT displayed typical endotheliosis alterations as seen in PE patients including markedly decreased luminal space of capillary loops accompanied by enlarged and swollen endothelial cells. Thus, the narrowed capillaries tended to be engorged with erythrocytes. However, the basement membranes of the capillaries were not significantly thickened. Additionally, the overlying podocyte foot processes were partially effaced and attenuated. There was no mesangial cell or matrix hyperplasia (Figure 2E). In contrast, the kidney tissue from mice injected with LIGHT and anti-LTβR or LIGHT and anti-HVEM showed similar ultrastructural features as the saline control group with unremarkable glomerular structure. Bland endothelial cells lined capillary loops with basement membranes of appropriate thickness. The capillary loops were open and not engorged with erythrocytes. The podocytes showed typical foot processes without effacement and showed no evidence of hyperplasia. The mesangial cells and matrix were not increased (Figure 2E). Overall, we have showed here that LIGHT signaling via both HVEM and LTβR contributes to hypertension, proteinuria and kidney injury in pregnant mice as seen in PE patients.

LIGHT signaling via LTβR and HVEM induces hypertension but not proteinuria in non-pregnant mice

In order to determine whether pregnancy is required for LIGHT induced features of PE, we injected LIGHT on two consecutive days into non-pregnant female mice. The results (Figure 3C) show that LIGHT induced high blood pressure in non-pregnant mice (153±3mmHg) compared to saline injected control mice (122±8mmHg). Moreover, to validate blood pressure measurement by tailcuff method, we determined intracarotid mean arterial pressure31 (Figure S4). Additionally, we co-injected anti-LTβR mAb or anti-HVEM mAb separately into non-pregnant mice that were injected with LIGHT. As with pregnant mice, blocking LTβR (131±6mmHg) or HVEM (134±9mmHg) by neutralizing antibody significantly reduced LIGHT-induced hypertension in non-pregnant mice (Figure 3C). However, urinary protein levels in non-pregnant mice were not significantly affected by LIGHT injection (Figure 3D), with or without co injection with neutralizing antibody to LTβR or HVEM. These findings indicate that pregnancy is required for LIGHT-induced proteinuria. However, LIGHT-induced hypertension is independent of pregnancy.

Circulating sFlt-1 is a downstream mediator induced by LIGHT via HVEM and LTβR activation in pregnant mice but not non-pregnant mice

In an effort to identify intracellular mediators functioning downstream of HVEM and LTβR that contribute to LIGHT-induced PE in pregnant mice, we measured circulating soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), a well-accepted pathogenic factor believed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of PE 7, 32. We found that circulating sFlt-1 levels were significantly increased in LIGHT-injected pregnant mice (57.20±10.46 ng/ml) compared with control group (29.93±2.73ng/ml). Moreover, we observed that elevated sFlt-1 levels in the circulation of LIGHT injected pregnant mice were significantly downregulated by co-treatment with anti-LTβR mAb (43.53±3.15ng/ml) or anti-HVEM mAb (38.57±6.68ng/ml) (Figure 3E). In contrast, there were no significant differences in the low levels of circulating sFlt-1 between the LIGHT injected non-pregnant mice with or without co-injection of anti-LTβR and anti-HVEM (Figure 3F). These findings indicate that LIGHT-mediated sFlt-1 induction is pregnancy-dependent and suggest that sFlt-1 induction by LIGHT signaling via LTβR and HVEM contributes to the proteinuria seen in pregnant mice but not non-pregnant mice.

Circulating ET-1 is a common downstream mediator induced by LIGHT via HVEM and LTβR activation in pregnant and non-pregnant mice

A number of studies suggest that increased levels of ET-1 contribute to the hypertensive features of PE 33, 34. To determine if LIGHT-induced hypertension is associated with elevated ET-1, pregnant and non-pregnant mice were injected with LIGHT in the presence or absence of neutralizing antibody to LTβR or HVEM and circulating ET-1 levels determined. The results (Figure 3G) show that LIGHT injection resulted in elevated circulating ET-1 in pregnant mice (2.37±0.54 pg/ml), and non-pregnant mice (1.54±0.15 pg/ml), compared to saline injected pregnant (0.42±0.13 pg/ml) and non-pregnant mice 0.54±0.23 pg/ml). Co-injection with anti-LTβR (pregnant mice: 1.11±0.13 pg/ml; non-pregnant mice: 1.04±0.19 pg/ml) or anti-HVEM (pregnant mice: 0.84±0.19 pg/ml; non-pregnant mice: 1.05±0.29 pg/ml) significantly inhibited LIGHT mediated induction of ET-1. These results indicate that LIGHT-mediated induction of ET-1 is independent of pregnancy and likely an important factor responsible for LIGHT-induced hypertension in both pregnant and non-pregnant mice.

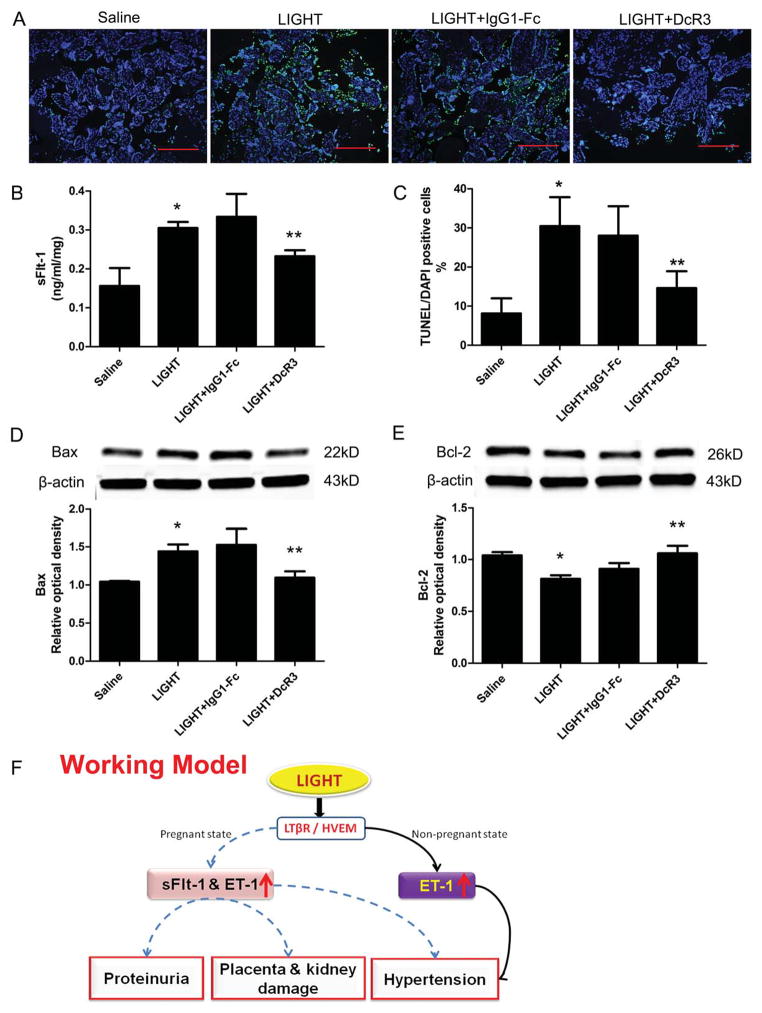

DcR3 inhibits LIGHT induced sFlt-1 secretion and placental apoptosis in human villous explants

Mice and rats do not have a DcR3 gene35. Thus, to explore the biological function of soluble receptor DcR3 in LIGHT induced features of PE, we incubated human placental villous explants from healthy term pregnancies with recombinant human LIGHT in the presence or absence of recombinant human DcR3. We measured the supernatant sFlt-1 levels by ELISA and demonstrated a significant increase in sFlt-1 secretion by placenta villous explants incubated with LIGHT (0.31±0.02ng/ml/mg) compared to placenta villous explants incubated with saline (0.16±0.05ng/ml/mg). However, elevated sFlt-1 secretion induced by LIGHT was significantly inhibited by co-treatment with DcR3 (0.23±0.02ng/ml/mg) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. LIGHT–mediated increase in placental tissue apoptosis and sFlt-1 secretion from human placental villous explants are inhibited by blocking LTβR or HVEM.

Human placental villous explants treated with saline or LIGHT in the presence or absence of DcR3 or IgG-Fc. (A) TUNEL-stained cultured human villous explants indicated that LIGHT increased apoptosis (green, TUNEL-positive cells; blue, DAPI nuclear stain; Bars, 500 μm). (B) sFlt-1 secretion from cultured human villous explants was significantly increased after 24 hour-incubation with LIGHT compared to saline-treated human villous explants. DcR3 significantly reduced sFlt-1 secretion induced by LIGHT (n=6 for each group). (C) Quantification of the increased apoptosis is reflected in an increased apoptotic index in the explants incubated with LIGHT. Co-incubation of the explants with LIGHT and DcR3 partially attenuated the increase in cell death. (D–E) Western blot analysis of explant proteins demonstrate increased Bax (D) and decreased Bcl-2 (E), indicating a proapoptotic state. Explants of placentas from two different women were cultured, and each variable was examined six times per placenta (n=12). IgG1-Fc had no effect on LIGHT-induced placental apoptosis and sFlt-1 secretion from human placental villous explants. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to saline incubated group; **P<0.05 compared to LIGHT-incubated group. (F) Working Model: Circulating LIGHT level is increased in PE patients. Elevated LIGHT functioning via activation of two transmembrane receptors, LTβR and HVEM, contributes to placental damage featured with apoptosis, secretion of vasoactive factors including sFlt-1 and ET-1 and subsequent disease development including hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice. However, LIGHT signaling via LTβR and HVEM only induces hypertension, but not proteinuria, in non-pregnant mice. LIGHT-mediated sFlt-1 production is a key mechanism underlying placenta tissue damage and preeclampsia development. Elevated of ET-1 is a common factor mediating LIGHT induced hypertension in both pregnant mice and non-pregnant mice. Decoy receptor, DcR3, can attenuate sFlt-1 secretion and placenta apoptosis stimulated by LIGHT. Thus, LIGHT signaling is a novel pathway contributing to pathogenesis of PE and serves as a potential therapeutic target for the disease.

To determine if placental tissue apoptosis is a downstream consequence of LIGHT treatment, we examined human placental tissue explants for apoptotic cells by TUNEL assay following incubation with LIGHT. Our results (Figure 4A&C) demonstrate a significant increase in the abundance of apoptotic cells in LIGHT treated human placental tissue. Additionally, we found LIGHT treatment increased Bax expression and reduced Bcl-2 expression in human placental explants (Figure 4D and E). Furthermore, increased placenta trophoblast cell apoptosis induced by LIGHT was significantly attenuated by co-treatment with DcR3 (Figure 4). Altogether, our results indicate that DcR3 can prevent LIGHT-induced sFlt-1 secretion and placental trophoblast cell apoptosis in human placenta explants.

Discussion

As a TNF superfamily member, LIGHT was initially discovered to be expressed in mature immune cells and involved in multiple inflammatory diseases and autoimmune conditions36. Although LIGHT and its receptors were subsequently shown to be expressed in trophoblasts and endothelial cells of human placentas25 and an elevated inflammatory response is a recognized feature of PE6, nothing is known about the role of LIGHT signaling in PE. Here, we provide both in vivo animal studies and in vitro human evidence that elevated LIGHT is a key contributor to hypertension, proteinuria, placental apoptosis and small fetuses in pregnant mice. Mechanistically, we determined that elevated LIGHT signaling via two membrane-anchored receptors, HVEM and LTβR, contributes to placental apoptosis and disease development. We further revealed that LIGHT signaling is a previously unrecognized immune cascade responsible not only for the induction of the vasoconstrictive peptide ET-1, but also for the induction of the anti-angiogenic factor, sFlt-1, and thereby plays an important role in the hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice. Overall, both mouse and human studies reported here provide strong evidence that LIGHT-mediated receptor activation is an underlying mechanism for placental damage, increased secretion of ET-1 and sFlt-1 and subsequent maternal clinical manifestations and suggest that these signaling pathways are novel therapeutic targets for disease management (Figure 4F).

LIGHT, as well as other TNF superfamily members, triggers both cell-death and survival signaling pathways37, 38. The functions of LIGHT are carried out by the activation of two receptors, HVEM and LTβR, expressed on the surface of specific target cells. Biological activities of LIGHT-LTβR signaling include the induction of apoptosis13, 16, 39, the generation and activation of various cytokines40, developmental organogenesis of lymph nodes41, and the restoration of secondary lymphoid structure and function42, 43. LIGHT signaling through HVEM is an important co-stimulatory signal for activation and proliferation of T cells. LIGHT stimulates T-cell proliferation and induces interferon-γ production, which can be inhibited by neutralizing antibodies to HVEM44. While most studies indicate that HVEM works principally as a pro-survival receptor for T cells and LTβR activation contributes to LIGHT induced apoptosis, there is also evidence that HVEM, but not LTβR, plays a key role in LIGHT induced tumor cell death in lymphoid malignancy45. Although LIGHT and its receptors are known to be expressed in the first trimester and term placental tissues24, 25, the biologic function of LIGHT in normal pregnancy and pregnancy related diseases has not been extensively explored. Our study is the first to show that LIGHT is significantly increased (>36 fold) in the circulation of preeclamptic women compared to normotensive pregnant women. In vivo experiments using pregnant mice and in vitro experiments using cultured human villous explants, demonstrated that LIGHT triggers placental damage characterized with placental apoptosis. These findings are strongly supported by early in vitro studies showing that LIGHT can induce human placental trophoblast cell apoptosis46. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that both LTβR and HVEM are responsible for LIGHT-induced placental cell apoptosis by increasing Bax expression and reducing Bcl-2 levels in LIGHT-injected pregnant mice. Similarly, we provide human evidence that the soluble receptor, DcR3, inhibits LIGHT-induced sFlt-1 secretion and apoptosis in human placental tissue explants, indicating a potentially protective role for DcR3 in the initiation and progression of PE. Altogether, we have revealed that elevated LIGHT signaling via its receptors is responsible for placental damage featured with placental apoptosis, an important mechanism in the pathogenesis of PE29.

We found that both LTβR and HVEM are expressed in human placenta tissue, consistent with preliminary research reported by Gill et al.25. To our surprise, not only was LIGHT expression increased in preeclamptic placentas but also the levels of LTβR and HVEM. Thus, the detrimental effects of elevated LIGHT signaling through its receptors is further enhanced by the increased placental expression of LIGHT and its receptors along with increased levels of LIGHT in the circulation. Supporting this model, we used neutralizing antibodies for LIGHT receptors to demonstrate that both HVEM and LTβR function downstream of LIGHT and contribute to LIGHT-induced disease development, including small placentas and fetuses in pregnant mice. It is possible that the combination of neutralizing antibodies would have an even greater effect than either one individually. Taken together, these studies revealed a new function of LIGHT signaling via HVEM and LTβR in pathogenesis of PE and highlighted novel therapeutic approaches to prevent LIGHT-induced placental apoptosis and PE features.

It is a widely held view that increased secretion of vasoactive factors by the placenta into the maternal circulation is responsible for systemic endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and multi-organ damage7, 47. In this regard, numerous recent studies showed that sFlt-1 is significantly elevated in the circulation of women with PE compared to women with normotensive pregnancy32. More importantly, introduction of viral vectors encoding sFlt-1 into pregnant rats resulted in proteinuria and hypertension, key features of PE7. These studies highlighted the role of sFlt-1 as a placenta-derived factor contributing to PE48. Here we showed that LIGHT injection into pregnant mice and LIGHT treatment of cultured human villous explants induced sFlt-1 production. Moreover, we have shown that LIGHT can also induce apoptosis in mouse placentas and in cultured human villous explants. Overall, our studies provide both human and mouse evidence that elevated LIGHT can induce placental apoptosis and sFlt-1 secretion. Of note, elevated sFlt-1 is known to contribute to pathophysiology of PE including abnormal placentation, hypertension and kidney injury7. Thus, it is possible that circulating LIGHT induces sFlt-1 secretion and placental apoptosis. Elevated sFlt-1 functions as downstream mediator to further impair placental development. As such, without interference, LIGHT-sFlt-1-placental impairment leads to progression of the disease and symptom development. Thus, these studies support our working model that LIGHT is a detrimental factor contributing to placental damage, increased placental secretion of vasoactive factors and disease development.

Because PE is a pregnancy specific disease, the placenta has been considered to play an indispensable role in the initiation and progression of the disease. To assess the importance of placentas in LIGHT-induced hypertension and proteinuria we injected LIGHT into non-pregnant as well as pregnant mice. In contrast to pregnant mice, LIGHT only induced hypertension, but not proteinuria, in non-pregnant mice. Mechanistically, we further revealed that LIGHT signaling via both HVEM and LTβR leads to elevation of circulating endothelin-1 (ET-1), but not sFlt-1, in non-pregnant mice. A possible explanation for these results is our finding that LIGHT is capable of inducing ET-1 production in both pregnant and non-pregnant mice, a feature that likely accounts for the increased blood pressure in each case. However, LIGHT-induced proteinuria was only observed in pregnant animals and was correlated with the induction of sFlt-1 only in pregnant animals. LIGHT mediated proteinuria in pregnant mice may be attributable to renal damage caused by increased sFlt-1 generation and secretion from placenta. In contrast to our findings with LIGHT-induced hypertension in non-pregnant mice, LaMarca and colleagues found that TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17 can only induce high blood pressure in pregnant rats, not in non-pregnant rats49–51. However these cytokine effects are presumably concentration dependent and it is possible that lower doses of LIGHT may be unable to induce hypertension in non-pregnant mice but still have effects in pregnant mice. Nevertheless, our studies provide a molecular basis underlying LIGHT-mediated differential effects between pregnant and non-pregnant mice: 1) LIGHT-mediated elevation of circulating ET-1 alone is enough to induce hypertension in non-pregnant mice; 2) the lack of renal pathology in LIGHT injected non-pregnant mice is correlated with the lack of elevated sFlt-1 in these animals; 3) A major source of sFlt-1 during pregnancy is the placenta, where LIGHT-mediated induction of sFlt-1 is likely to contribute to renal pathology.

In contrast to other members of the TNF receptor superfamily, the gene encoding DcR3 does not include a transmembrane domain and results in the production of an obligate secreted protein of 300 amino acids35. As a soluble receptor, DcR3 is capable of neutralizing the biological effects of three members of the TNF superfamily (TNFSF): Fas ligand (FasL/TNFSF6)52, LIGHT (TNFSF14)53 and TNF-like molecule 1A (TL1A/TNFSF15)54. Infusion of DcR3 ameliorates the autoimmune kidney diseases, crescentic glomerulonephritis55 and IgA56 nephropathy, in mouse models. The therapeutic potential of DcR3 has also been demonstrated for experimental rheumatoid arthritis38 multiple sclerosis57 and inflammatory bowel disease58. The underlying mechanisms include modulation of T-cell activation/proliferation or B-cell activation, protection against apoptosis suppression of mononuclear leukocyte infiltration and diminished TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-17 expression35. DcR3 orthologs have not been identified in the mouse or rat genomes, indicating a crucial difference between the human and rodent immune systems35. Thus, we took advantage of human placenta explants to investigate the biologic function of DcR3 in LIGHT induced features of PE, and demonstrated DcR3 successfully attenuated LIGHT-induced sFlt-1 secretion and trophoblast cell apoptosis in human placenta explants. In contrast to the elevated expression levels of HVEM and LTβR, the expression levels of DcR3 in the placentas of preeclamptic women are significantly reduced compared to normal individuals. These results suggest that reduction of placental expression of DcR3, a soluble decoy receptor, coupled with elevated placental expression of membrane-anchored receptors, HVEM and LTβR, are additional mechanisms to amplify elevated-LIGHT-induced placental damage and sFlt-1 secretion. Thus, DcR3, as an endogenous soluble receptor, is likely a safe and effective therapy to prevent LIGHT induced impaired angiogenesis and placenta tissue damage and therefore has potential as a treatment for human PE.

Because of its strong pro-inflammatory properties and immune-stimulatory activities excessive LIGHT is associated with a number of pathological conditions36. In particular, LIGHT contributes to pathophysiology associated with a number of autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, chronic arthritis and psoriatic arthritis37. The use of soluble DcR3 receptor or neutralizing antibodies for its membrane receptors have become important therapeutic strategies for the treatment of these autoimmune disorders in multiple animal models38. PE may also benefit from this therapeutic approach.

Perspectives

The work reported here is the first to show that elevated LIGHT, coupled with enhanced LTβR and HVEM receptor activation, promotes placental damage and triggers release of potent vasoactive factors (sFlt-1 and ET-1) in both human and murine pregnancy and suggest that LIGHT signaling is likely an important mediator of pathogenesis associated with PE. Therefore the use of HVEM/LTβR neutralizing antibodies, or the soluble form of LIGHT receptor, DcR3, to blunt the effects of elevated LIGHT may represent a novel treatment for PE. Our current findings have significantly advanced our understanding of pathogenesis of PE by revealing the pathogenic role of LIGHT signaling in PE and also provide a strong foundation for future translational studies to determine whether circulating LIGHT is elevated prior to symptoms and in this way serves as a pre-symptomatic biomarker and therapeutic target for PE.

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

The TNF family member LIGHT (TNFSF14) is substantially elevated in the circulation and placentas of women with PE.

LIGHT-mediated activation of its receptors, LTβR and HVEM, induces apoptosis and increases sFlt-1 secretion by cultured human placental explants

The introduction of LIGHT in pregnant mice stimulates placental apoptosis and increased production of sFlt-1 and endothelin-1, and is accompanied with hypertension and proteinuria via activation of its receptors.

What is Relevant?

Our results reveal a previously unrecognized role of LIGHT signaling in the pathogenesis of PE and reveal potential therapeutic opportunities.

Summary

We report that LIGHT, a novel TNF superfamily member, is significantly elevated in the circulation and placentas of preeclamptic women compared to women with normotensive pregnancies. A pathological role for LIGHT in PE is indicated by the results of experiments showing that the infusion of LIGHT into pregnant mice directly induced placental apoptosis, small fetuses and key features of PE-hypertension and proteinuria. Mechanistically, using neutralizing antibodies specific for LIGHT receptors, we found that LIGHT transmembrane receptors, herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM) and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR), are required for LIGHT-induced placental impairment, small fetuses and PE features in pregnant mice. Accordingly, we further revealed that LIGHT functions through these two receptors to induce secretion of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1) and endothelin-1 (ET-1), two well-accepted pathogenic factors in PE, and thereby plays an important role in hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice. Lastly, we extended our animal findings to human studies and demonstrated that activation of LIGHT receptors resulted in increased apoptosis and elevation of sFlt-1 secretion in human placental villous explants. Overall, both human and mouse studies revealed a novel role of LIGHT in pathophysiology of PE and potential therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants HL076558 (to Y.X.), DK077748 (to Y.X.), DK083559 (to Y.X), HL113574 (to YX) and RC4HD067977 and HD34130 (to Y.X and R.E.K.). American Heart Association Grant 10GRNT3760081 (to Y.X.) and China National Science Foundation 81228004 (to Y.X.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Roberts JM, Cooper DW. Pathogenesis and genetics of pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2001;357:53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA. Pathophysiology of preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia/hypoxia with microvascular dysfunction. Microcirculation. 2002;9:147–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey KM, Barker DJ. Fetal nutrition and adult disease. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2000;71:1344S–1352S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1344s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 1998;95:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito S, Sakai M. Th1/th2 balance in preeclampsia. Journal of reproductive immunology. 2003;59:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(03)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamarca B. The role of immune activation in contributing to vascular dysfunction and the pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia. Minerva ginecologica. 2010;62:105–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sflt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girardi G, Yarilin D, Thurman JM, Holers VM, Salmon JE. Complement activation induces dysregulation of angiogenic factors and causes fetal rejection and growth restriction. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2165–2175. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou CC, Ahmad S, Mi T, Abbasi S, Xia L, Day MC, Ramin SM, Ahmed A, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Autoantibody from women with preeclampsia induces soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 production via angiotensin type 1 receptor and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated t-cells signaling. Hypertension. 2008;51:1010–1019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yui J, Garcia-Lloret M, Wegmann TG, Guilbert LJ. Cytotoxicity of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and gamma-interferon against primary human placental trophoblasts. Placenta. 1994;15:819–835. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(05)80184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayakawa S, Nagai N, Kanaeda T, Karasaki-Suzuki M, Ishii M, Chishima F, Satoh K. Interleukin-12 augments cytolytic activity of peripheral and decidual lymphocytes against choriocarcinoma cell lines and primary culture human placental trophoblasts. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;41:320–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad S, Ahmed A. Elevated placental soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 inhibits angiogenesis in preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2004;95:884–891. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147365.86159.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rooney IA, Butrovich KD, Glass AA, Borboroglu S, Benedict CA, Whitbeck JC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Ware CF. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor is necessary and sufficient for light-mediated apoptosis of tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14307–14315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granger SW, Butrovich KD, Houshmand P, Edwards WR, Ware CF. Genomic characterization of light reveals linkage to an immune response locus on chromosome 19p13.3 and distinct isoforms generated by alternate splicing or proteolysis. J Immunol. 2001;167:5122–5128. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhai Y, Guo R, Hsu TL, Yu GL, Ni J, Kwon BS, Jiang GW, Lu J, Tan J, Ugustus M, Carter K, Rojas L, Zhu F, Lincoln C, Endress G, Xing L, Wang S, Oh KO, Gentz R, Ruben S, Lippman ME, Hsieh SL, Yang D. Light, a novel ligand for lymphotoxin beta receptor and tr2/hvem induces apoptosis and suppresses in vivo tumor formation via gene transfer. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1142–1151. doi: 10.1172/JCI3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Zhang C, Zhuang G, Luo H, Su J, Yin P, Wang J. Decoy receptor 3 overexpression and immunologic tolerance in hepatocellular carcinoma (hcc) development. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:965–974. doi: 10.1080/07357900801975256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller AM, Pedre X, Killian S, David M, Steinbrecher A. The decoy receptor 3 (dcr3, tnfrsf6b) suppresses th17 immune responses and is abundant in human cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;209:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Ge C, Liu R, Zhang K, Wu G, Huo W. Administration of dendritic cells dual expressing dcr3 and gad65 mediates the suppression of t cells and induces long-term acceptance of pancreatic-islet transplantation. Vaccine. 2010;28:8300–8305. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand S, Wang P, Yoshimura K, Choi IH, Hilliard A, Chen YH, Wang CR, Schulick R, Flies AS, Flies DB, Zhu G, Xu Y, Pardoll DM, Chen L, Tamada K. Essential role of tnf family molecule light as a cytokine in the pathogenesis of hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1045–1051. doi: 10.1172/JCI27083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Shedding light on severe asthma. Nat Med. 2011;17:547–548. doi: 10.1038/nm0511-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandberg WJ, Halvorsen B, Yndestad A, Smith C, Otterdal K, Brosstad FR, Froland SS, Olofsson PS, Damas JK, Gullestad L, Hansson GK, Oie E, Aukrust P. Inflammatory interaction between light and proteinase-activated receptor-2 in endothelial cells: Potential role in atherogenesis. Circ Res. 2009;104:60–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierer M, Brentano F, Rethage J, Wagner U, Hantzschel H, Gay RE, Gay S, Kyburz D. The tnf superfamily member light contributes to survival and activation of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Anders RA, Wang Y, Turner JR, Abraham C, Pfeffer K, Fu YX. The critical role of light in promoting intestinal inflammation and crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2005;174:8173–8182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gill RM, Coleman NM, Hunt JS. Differential cellular expression of light and its receptors in early gestation human placentas. J Reprod Immunol. 2007;74:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gill RM, Ni J, Hunt JS. Differential expression of light and its receptors in human placental villi and amniochorion membranes. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2011–2017. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64479-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips TA, Ni J, Hunt JS. Death-inducing tumour necrosis factor (tnf) superfamily ligands and receptors are transcribed in human placentae, cytotrophoblasts, placental macrophages and placental cell lines. Placenta. 2001;22:663–672. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the nhlbi working group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2003;41:437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054981.03589.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nature medicine. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Irani RA, Zhang Y, Blackwell SC, Zhou CC, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. The detrimental role of angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies in intrauterine growth restriction seen in preeclampsia. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2809–2822. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui AH, Irani RA, Blackwell SC, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibody is highly prevalent in preeclampsia: Correlation with disease severity. Hypertension. 2010;55:386–393. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Wang W, Yu H, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Ning C, Tao L, Sun H, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Xia Y. Interleukin 6 underlies angiotensin ii-induced hypertension and chronic renal damage. Hypertension. 2012;59:136–144. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.173328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:672–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain A. Endothelin-1: A key pathological factor in pre-eclampsia? Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;5:443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.George EM, Granger JP. Endothelin: Key mediator of hypertension in preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:964–969. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin WW, Hsieh SL. Decoy receptor 3: A pleiotropic immunomodulator and biomarker for inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:838–847. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauri DN, Ebner R, Montgomery RI, Kochel KD, Cheung TC, Yu GL, Ruben S, Murphy M, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Spear PG, Ware CF. Light, a new member of the tnf superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware CF. Network communications: Lymphotoxins, light, and tnf. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:787–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamada K, Shimozaki K, Chapoval AI, Zhai Y, Su J, Chen SF, Hsieh SL, Nagata S, Ni J, Chen L. Light, a tnf-like molecule, costimulates t cell proliferation and is required for dendritic cell-mediated allogeneic t cell response. J Immunol. 2000;164:4105–4110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dejardin E, Droin NM, Delhase M, Haas E, Cao Y, Makris C, Li ZW, Karin M, Ware CF, Green DR. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two nf-kappab pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Degli-Esposti MA, Davis-Smith T, Din WS, Smolak PJ, Goodwin RG, Smith CA. Activation of the lymphotoxin beta receptor by cross-linking induces chemokine production and growth arrest in a375 melanoma cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:1756–1762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheu S, Alferink J, Potzel T, Barchet W, Kalinke U, Pfeffer K. Targeted disruption of light causes defects in costimulatory t cell activation and reveals cooperation with lymphotoxin beta in mesenteric lymph node genesis. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1613–1624. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gommerman JL, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:642–655. doi: 10.1038/nri1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Foster A, Chin R, Yu P, Sun Y, Wang Y, Pfeffer K, Fu YX. The complementation of lymphotoxin deficiency with light, a newly discovered tnf family member, for the restoration of secondary lymphoid structure and function. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1969–1979. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200207)32:7<1969::AID-IMMU1969>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrop JA, Reddy M, Dede K, Brigham-Burke M, Lyn S, Tan KB, Silverman C, Eichman C, DiPrinzio R, Spampanato J, Porter T, Holmes S, Young PR, Truneh A. Antibodies to tr2 (herpesvirus entry mediator), a new member of the tnf receptor superfamily, block t cell proliferation, expression of activation markers, and production of cytokines. J Immunol. 1998;161:1786–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pasero C, Barbarat B, Just-Landi S, Bernard A, Aurran-Schleinitz T, Rey J, Eldering E, Truneh A, Costello RT, Olive D. A role for hvem, but not lymphotoxin-beta receptor, in light-induced tumor cell death and chemokine production. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2502–2514. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gill RM, Hunt JS. Soluble receptor (dcr3) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis-2 (ciap-2) protect human cytotrophoblast cells against light-mediated apoptosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:309–317. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D’Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nature medicine. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, Hanai J, Mammoto T, Kim YM, Bdolah Y, Lim KH, Yuan HT, Libermann TA, Stillman IE, Roberts D, D’Amore PA, Epstein FH, Sellke FW, Romero R, Sukhatme VP, Letarte M, Karumanchi SA. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nature medicine. 2006;12:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.LaMarca BB, Cockrell K, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Granger JP. Role of endothelin in mediating tumor necrosis factor-induced hypertension in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2005;46:82–86. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000169152.59854.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gadonski G, LaMarca BB, Sullivan E, Bennett W, Chandler D, Granger JP. Hypertension produced by reductions in uterine perfusion in the pregnant rat: Role of interleukin 6. Hypertension. 2006;48:711–716. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238442.33463.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhillion P, Wallace K, Herse F, Scott J, Wallukat G, Heath J, Mosely J, Martin JN, Jr, Dechend R, Lamarca B. Il-17-mediated oxidative stress is an important stimulator of at1-aa and hypertension during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R353–358. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00051.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Lawrence DA, Roy M, Kischkel FC, Dowd P, Huang A, Donahue CJ, Sherwood SW, Baldwin DT, Godowski PJ, Wood WI, Gurney AL, Hillan KJ, Cohen RL, Goddard AD, Botstein D, Ashkenazi A. Genomic amplification of a decoy receptor for fas ligand in lung and colon cancer. Nature. 1998;396:699–703. doi: 10.1038/25387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu KY, Kwon B, Ni J, Zhai Y, Ebner R, Kwon BS. A newly identified member of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (tr6) suppresses light-mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13733–13736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Migone TS, Zhang J, Luo X, Zhuang L, Chen C, Hu B, Hong JS, Perry JW, Chen SF, Zhou JX, Cho YH, Ullrich S, Kanakaraj P, Carrell J, Boyd E, Olsen HS, Hu G, Pukac L, Liu D, Ni J, Kim S, Gentz R, Feng P, Moore PA, Ruben SM, Wei P. Tl1a is a tnf-like ligand for dr3 and tr6/dcr3 and functions as a t cell costimulator. Immunity. 2002;16:479–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ka SM, Sytwu HK, Chang DM, Hsieh SL, Tsai PY, Chen A. Decoy receptor 3 ameliorates an autoimmune crescentic glomerulonephritis model in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2473–2485. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ka SM, Hsieh TT, Lin SH, Yang SS, Wu CC, Sytwu HK, Chen A. Decoy receptor 3 inhibits renal mononuclear leukocyte infiltration and apoptosis and prevents progression of iga nephropathy in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;301:F1218–1230. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00050.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen SJ, Wang YL, Kao JH, Wu SF, Lo WT, Wu CC, Tao PL, Wang CC, Chang DM, Sytwu HK. Decoy receptor 3 ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by directly counteracting local inflammation and downregulating th17 cells. Mol Immunol. 2009;47:567–574. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bamias G, Kaltsa G, Siakavellas SI, Gizis M, Margantinis G, Zampeli E, Vafiadis-Zoumboulis I, Michopoulos S, Daikos GL, Ladas SD. Differential expression of the tl1a/dcr3 system of tnf/tnfr-like proteins in large vs. Small intestinal crohn’s disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]