Abstract

Background

Appetite is frequently affected in cancer patients leading to anorexia and consequently insufficient food intake. In this study, we report on hypothalamic gene expression profile of a cancer-cachectic mouse model with increased food intake. In this model, mice bearing C26 tumour have an increased food intake subsequently to the loss of body weight. We hypothesise that in this model, appetite-regulating systems in the hypothalamus, which apparently fail in anorexia, are still able to adapt adequately to changes in energy balance. Therefore, studying changes that occur on appetite regulators in the hypothalamus might reveal targets for treatment of cancer-induced eating disorders. By applying transcriptomics, many appetite-regulating systems in the hypothalamus could be taken into account, providing an overview of changes that occur in the hypothalamus during tumour growth.

Methods

C26-colon adenocarcinoma cells were subcutaneously inoculated in 6 weeks old male CDF1 mice. Body weight and food intake were measured three times a week. On day 20, hypothalamus was dissected and used for transcriptomics using Affymetrix chips.

Results

Food intake increased significantly in cachectic tumour-bearing mice (TB), synchronously to the loss of body weight. Hypothalamic gene expression of orexigenic neuropeptides NPY and AgRP was higher, whereas expression of anorexigenic genes CCK and POMC were lower in TB compared to controls.

In addition, serotonin and dopamine signalling pathways were found to be significantly altered in TB mice. Serotonin levels in brain showed to be lower in TB mice compared to control mice, while dopamine levels did not change. Moreover, serotonin levels inversely correlated with food intake.

Conclusions

Transcriptomic analysis of the hypothalamus of cachectic TB mice with an increased food intake showed changes in NPY, AgRP and serotonin signalling. Serotonin levels in the brain showed to correlate with changes in food intake. Further research has to reveal whether targeting these systems will be a good strategy to avoid the development of cancer-induced eating disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13539-013-0121-y) contains supplementary material.

Keywords: Cancer, Hypothalamus, Appetite, Serotonin, Transcriptomics, Anorexia

Introduction

Anorexia affects 60–80 % of all patients with cancer and considerably contributes to disease-related malnutrition and cachexia, which in turn strongly affect patient’s morbidity, mortality and quality of life [1].

Anorexia is often linked to cachexia, a complex metabolic syndrome associated with underlying illness which is characterised by progressive loss of muscle (muscle wasting) with or without loss of fat mass resulting in weight loss [2]. Although anorexia and cachexia are likely to be initiated by similar pathologies, several lines of evidence suggest that both conditions progress via distinct mechanisms. However, the presence of cachexia makes it difficult to disentangle the primary underlying mechanisms of cancer anorexia since this might be due to tumour growth, cachexia progression or other disease-related mechanisms.

Cancer anorexia is generally considered to be a multifactorial condition. Contributing to its complexity is the observation that evolution has developed powerful physiological mechanisms favouring food intake. It has been shown that upon shifting the balance to anorexia, pathways can become redundant when they are not functioning properly. This is for example shown by data obtained from studying knockout animals for well-known food intake regulators, the NPY knockout mouse [3], the AgRP knockout mouse [4] or the ghrelin knockout mouse [5]. These mice display regular food intake and body weight regulation despite the loss of a significant key modulator in appetite regulation. The difficulties encountered in studying cancer anorexia inspired us to approach the problem from a different angle. Cancer-induced anorexia is suggested to be predominantly caused by the inability of the hypothalamus to respond adequately to pivotal peripheral signals involved in appetite regulation [6]. This hypothalamic resistance to peripheral neuro-endocrine signals is believed to be due to the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting from tumour growth [6]. In this study, we report on hypothalamic gene expression profiles in a cancer-cachectic model with increased food intake. In this model, appetite-regulating systems, which apparently fail in anorexia, are still able to adapt adequately to changes in energy balance. By applying transcriptomics, many appetite-regulating systems in the hypothalamus could be taken into account. Here, we provide an overview of changes that occur in the hypothalamus during tumour growth which could be important in the development of cancer-induced eating disorders.

Materials and methods

Tumour model

Male CDF1 (BALB/cx DBA/2) mice aged 6 to 7 weeks were obtained from Harlan Nederland (Horst, The Netherlands).

Animals were individually housed 1 week before start of the experiment in a climate-controlled room (12:12 dark–light cycle; 21 °C ± 1 °C).

Mice were placed on a standard ad libitum diet (AIN93M, research Diet Services, The Netherlands) and had free access to water.

Murine C26 adenocarcinoma cells were cultured and suspended as described previously [7]. Under general anaesthesia (isoflurane/N2O/O2), tumour cells in 0.2 ml HBSS were inoculated subcutaneously into the right inguinal flank. Controls were sham-injected with 0.2 ml HBSS.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Ethical Committee (DEC, Bilthoven, The Netherlands) and complied with the principles of good laboratory animal care.

Experimental design

On day 0, tumour cells were injected. BW, food intake and tumour size were measured three times a week. Tumour size was determined by measuring the length and width of the tumour with a calliper. On day 20, body composition was determined by DEXA (Lunar, PIXImus). Subsequently, blood was collected by cardiac puncture. After sacrifice, brain, hypothalamus, organs and lower leg skeletal muscles were weighted and frozen at −80 °C. Two studies were performed with similar settings: study A was a pilot study to optimise experimental conditions and was followed by study B. Table 1 shows the number of tumour cells used for inoculation in the different groups that were included in the two studies.

Table 1.

Groups included in study A and study B. Pilot study A was performed prior to study B. In study A, mice were injected with different amounts of C26-colon adenocarcinoma cells, while study B comprised of one tumour-bearing group and one control group

| Study A | Study B |

|---|---|

| C: control, sham injected (n = 4) | C: control, sham injected (n = 6) |

| TB-0.5: tumour-bearing, 0.5 × 106 C26-cells (n = 4) | TB: tumour-bearing, 1 × 106 C26-cells (n = 9) |

| TB-1: tumour-bearing, 1 × 106 C26-cells (n = 3) |

Blood plasma amino acids and cytokines

Amino acids were measured by using HPLC with ortho-phthalaldehyde as derivatization reagent and L-norvaline as internal standard (Sigma Aldrich). The method was adapted from van Eijk et al. [8].

Cytokines were measured using a mouse cytokine 10-plex bead immunoassay (Biosource, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands). Prostaglandin E2 was measured using an enzyme-immunoassay kit (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI, USA).

Serotonin and dopamine levels

Hypothalamic samples were used for microarray experiments, while remaining brain parts were used to determine serotonin and dopamine levels. Brains were homogenized in 1 ml containing 40 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 0.50 % Triton X-100 and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor (Roche Nederland, The Netherlands). Citric acid (1 %) was added to prevent serotonin oxidation. Serotonin and dopamine levels were measured using enzyme-immunoassay kits (BAE-5900, BAE-5300, LDN, Nordhorn, Germany).

Statistics

Data was analysed by statistical analysis of variance followed by a post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison/Bonferroni test or by a Student’s t test. Differences were considered significant at a two-tailed P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism 5. For statistical analysis of microarray data, see microarray section (below).

Microarray studies

Total RNA from the hypothalamus was isolated by using RNeasy Lipid tissue kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). RNA concentrations were measured by absorbance at 260 nm (Nanodrop). RNA quality was checked using the RNA 6000 Nano assay on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Techologies, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For each mouse, total RNA (100 ng) was labelled using the Ambion WT expression kit (Life Technologies, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands). Microarray experiments were performed by using Affymetrix Mouse Gene ST 1.0 (study A) and 1.1 (study B).

For both studies A and B, samples were pooled for each group. Also, individual samples from study B were included in a subsequent microarray experiment to confirm the findings on appetite regulators and canonical pathways. In this microarray experiment, four control samples and five samples from tumour-bearing mice were included in this experiment; however, one control sample gave various spots on the array and was therefore excluded from analysis.

Array data were analysed using an in-house online system [9]. Shortly, probe sets were redefined according to Dai et al. [10] using remapped CDF version 15.1 based on the Entrez Gene database. In total, these arrays target 21,225 unique genes. Robust multi-array analysis was used to obtain expression values [11, 12]. For study B, we only took genes into account that had an intensity >20 on at least two arrays, had an interquartile range throughout the samples >0.1 and had at least seven probes per genes. In total, 8,763 genes passed the filter. Genes were considered differentially expressed at P < 0.05 after intensity based moderated t-statistics [13]. Further functional interpretation of the data was performed through the use of IPA (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Canonical pathway analysis identified the pathways from the IPA library of canonical pathways that were most significant to the data set. Genes from the data set that met the cutoff of 1.3-fold change and p value cutoff of 0.05 and were associated with a canonical pathway in the Ingenuity Knowledge Base were considered for the analysis.

Array data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE44082.

Results

Body weight and food intake

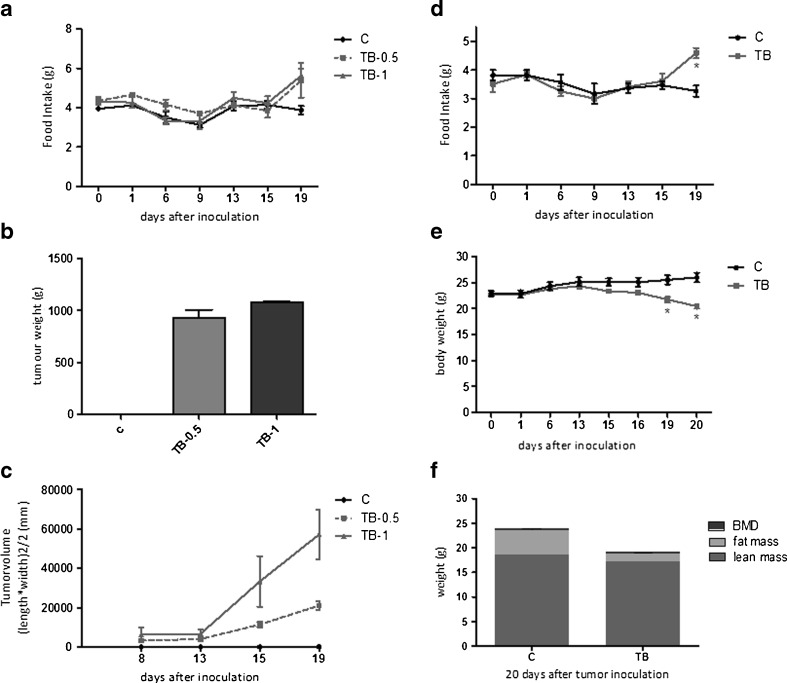

In study A, tumour size and tumour weight did not increase correspondingly to the number of tumour cells injected (Fig. 1b, c). However, carcass weight, epididymal fat pad weight and skeletal muscle weight decreased proportionally to the number of tumour cells injected, suggesting that body wasting increases with tumour load despite the weight of the tumour being similar (Supplementary table S1). Food intake in all tumour-bearing animals was found to increase after 15 days. At day 19, tumour-bearing (TB) mice in TB-0.5 and TB-1 groups ate approximately 45 % more than the controls. An increase of food intake in TB mice was again noticed in subsequent study B (Fig. 1a, d). In this study, food intake of TB mice was 40 % higher than controls at day 19. On day 13, after tumour inoculation, TB mice started to lose body weight (BW). Synchronously to the decline in body weight, an increase in food intake in TB mice was measured, suggesting compensatory eating by TB mice in order to cope with loss of BW. The loss of lean mass, fat mass and skeletal muscle weight in TB mice in study B was comparable with that of study A, showing that the level and severity of cachexia developed in TB animals was similar in both studies (Supplementary table S1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of tumour inoculation on food intake, tumour size, tumour weight, body weight and body composition in studies A and B. a Time course of change in food intake of TB mice in study A. b Tumour weight at day 20 in study A. c Tumour width and length were measured twice a week with a calliper and used to calculate tumour volume. d Time course of change in food intake of TB mice in study B. e Time course of change in body weight in study B. f Body composition determined by DEXA scan in study B. *P < 0.05 (significantly different from C). Data is expressed as mean ± SEM. C sham-injected control, TB-0.5 injected with 0.5 × 106 tumour cells, TB-1 injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells and TB injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells

Microarray analysis of the hypothalamus

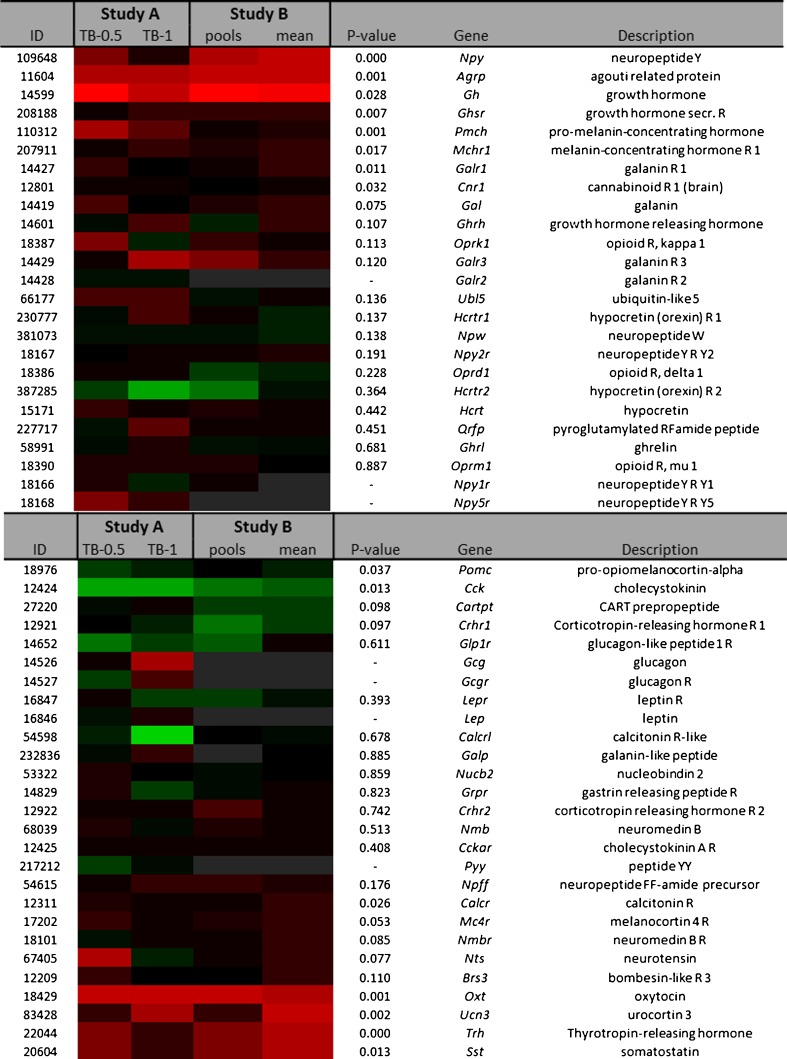

The heat map in Fig. 2 shows fold changes of orexigenic and anorexigenic gene expressions. Orexigenic neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related protein (AgRP) expression were found to be significantly higher by 1.9 and 1.6-fold, respectively, in TB mice. Orexigenic ghrelin expression was comparable between TB mice and controls. However, expression of the growth hormone-secretagogue receptor (GHsR), which mediates ghrelin signalling, showed to be slightly higher by 1.2-fold. In addition, growth hormone (GH) expression, which also acts via GHsR and stimulates food intake, showed to be highly upregulated in TB mice. Expression of anorexigenic somatostatin showed to be 1.2-fold higher in TB mice compared to controls. Somatostatin is a strong negative feedback regulator of GH, suggesting that its upregulation could be a result of increased GH expression.

Fig. 2.

Heat map representation of fold changes of orexigenic and anorexigenic genes in the hypothalamus in studies A and B. RNA from hypothalamus was used to perform microarray experiment using Affymetrix chips. Fold changes relative to their control group were calculated and compared between the two studies. Each row represents a gene and each column represents a group of animals. RNA samples from the same group were pooled for analysis in study A. Study A: TB-0.5 injected with 0.5 × 106 tumour cells and TB-1 injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells. In study B, TB mice were injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells and both pooled samples (pools) and individual replicates (mean) were analysed. Pools RNA from all mice within one group were pooled, mean calculated mean from replicates. Red colour indicates genes that were higher expressed as control, and green colour indicates genes that were lower expressed as the control. Black indicates genes whose expression was similar to compared to control. Grey indicates genes that were filtered out (NA) because absolute expression values were below the predefined threshold limits (M and M section) ID Entrez ID, R receptor, NA not analysed

Anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and cholecystokinin (CCK) expressions were slightly lower in TB by 1.1-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively. PYY, leptin and glucagon expression were not included in the analysis because absolute expressions were below threshold.

In addition to analysis of appetite regulators, a list of highly upregulated genes was generated. Genes that were upregulated with a fold change above 1.5 in both studies A and B resulted in a list of 19 genes that were highly upregulated in both studies (Supplementary table S2). Lipocalin 2 and leucin-richα2-glycoprotein 1 are both discussed for their role in tumour progression and for being potential biomarkers for cancer progression [14, 15] and secretoglobin (Scgb3a1) is considered a strong tumour suppressor [16]. Lipocalin 2 expression in hypothalamus has been reported to be strongly elevated upon influenza infection in mice, suggesting that lipocalin 2 in the brain is able to sense inflammatory stressors from the periphery [17]. The strong upregulation of also other inflammatory genes as interleukin 1 receptor and oncostatin M receptor in both studies contribute to the idea of an elevated inflammatory status in the hypothalamic area.

Pathway analysis: serotonin and dopamine signalling

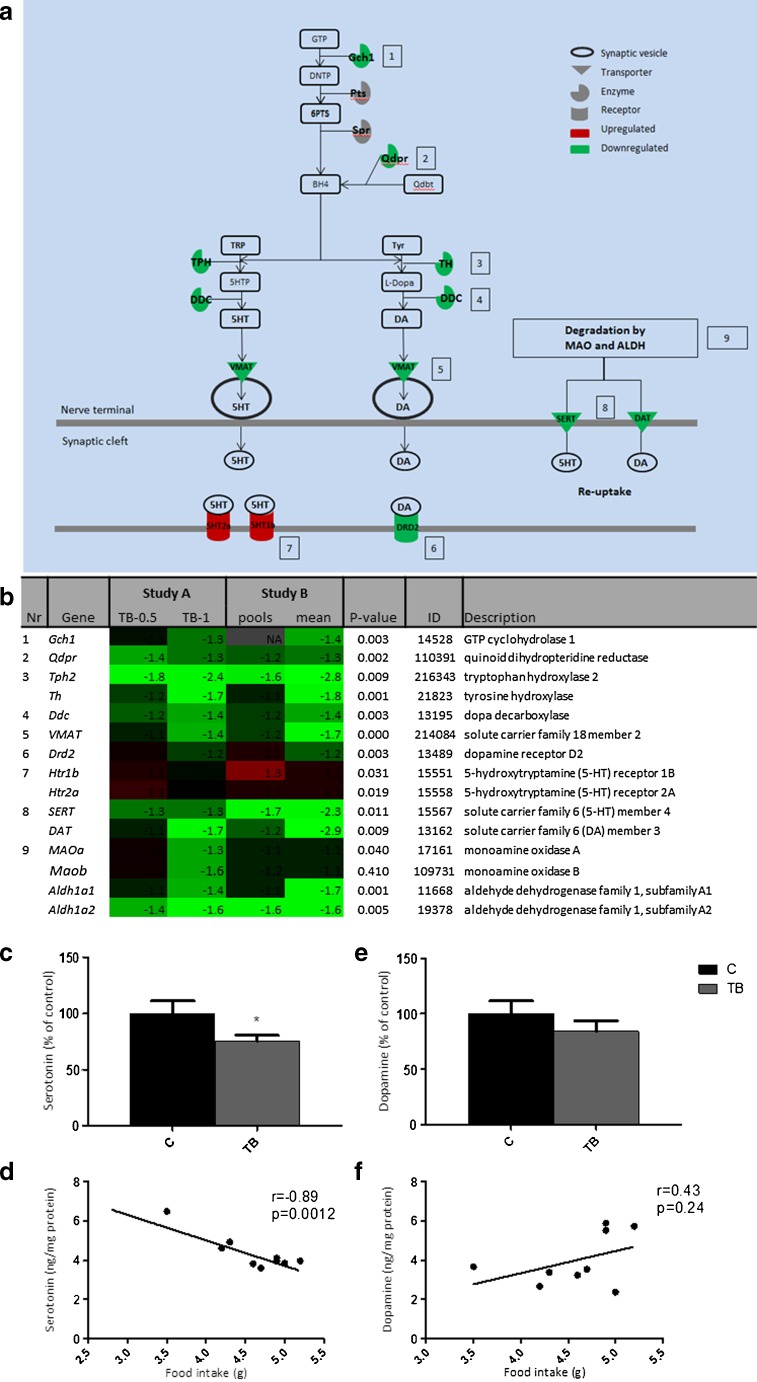

Pathway analysis using Ingenuity Systems showed that the serotonin (5-HT) receptor signalling pathway was significantly altered (P < 0.05) in the hypothalamic tissues of TB mice (Supplementary figure 1). Expression of genes involved in both 5-HT synthesis and 5-HT degradation showed to be lower in TB mice than in controls, pointing towards a compensatory mechanism regulating expression of these enzymes.

Pathway analysis further showed that besides 5-HT signalling, also dopamine (DA) signalling was altered (Supplementary figure 1). Several genes involved in 5-HT signalling are also of importance in dopamine signalling. Changes in these shared genes between the 5-HT and DA pathways are therefore likely to have an effect on both neurotransmitters. Expression of gch1, qdpr and ddc, which are involved in the synthesis of both 5-HT and DA, were strongly downregulated. Also, transporter vmat, which is important in transporting 5-HT and DA into the neuronal synapse, showed to be 1.7-fold lower in TB mice compared to controls. Tryptophan hydroxylase (tph) and tyrosine hydroxylase (th), rate-limiting enzymes in the synthesis of 5-HT or DA, respectively, were also strongly downregulated. In addition, SERT and DAT, re-uptake transporters of 5-HT and DA, respectively, in order to terminate activation in the synaptic cleft showed to be more than twofold lower in TB mice. This indicates that besides shared genes between the 5-HT and DA pathways, also genes specifically involved in either DA or 5-HT synthesis, were altered.

Figure 3a shows an overview of genes involved in 5-HT and DA signalling and their fold changes.

Fig. 3.

Serotonin and dopamine signalling in TB mice and correlations with food intake. Canonical pathway analysis with IPA (Ingenuity® Systems) revealed serotonin receptor signalling pathway and dopamine receptor signalling pathway as being significantly changed in tumour-bearing mice in both studies. a Overview of serotonin and dopamine signalling pathway and their overlapping genes (Gch1, Qdpr, DDC, VMAT and degrading enzymes MAO and ALDH). Expression of genes necessary for the synthesis of serotonin/dopamine as well as genes playing a role in the termination of serotonin/dopamine signalling in the synapse showed to be downregulated. b Heat map of fold changes of numbered genes. Genes 1–5 represent genes involved in both serotonin and dopamine signalling. c Serotonin level in brain relative to control mice. d Correlation of serotonin with food intake. e Dopamine level in brain relative to control mice. f Correlation of dopamine with food intake. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. C sham-injected control, TB injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells *P < 0.05 (significantly different from C). DHNTP 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate, 6PTS 6-pyruvoyl-tetrahydropterin, 5HIAA 5-Hydroxyindole acetic acid, q-dbt q-dihydrobiopterin, KYN kynurenine, TRP tryptophan, DA dopamine, 5HT 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), MAO mono amine oxidase, ALDH aldehyde dehydrogenase, SULT sulfotransferase

To determine the effects of these changes on gene expression, 5-HT and DA levels were measured. Serotonin levels showed to be significantly lower in the TB mice, whereas DA levels showed not to be different in TB mice compared to control animals (Fig. 3c–e). Since both DA and 5-HT have been discussed for their role in food intake and feeding behaviour, correlation between these neurotransmitters and food intake were studied. Serotonin levels were found to correlate with food intake in both C and TB mice, while this correlation could not be made for DA and food intake (Fig. 3d–f).

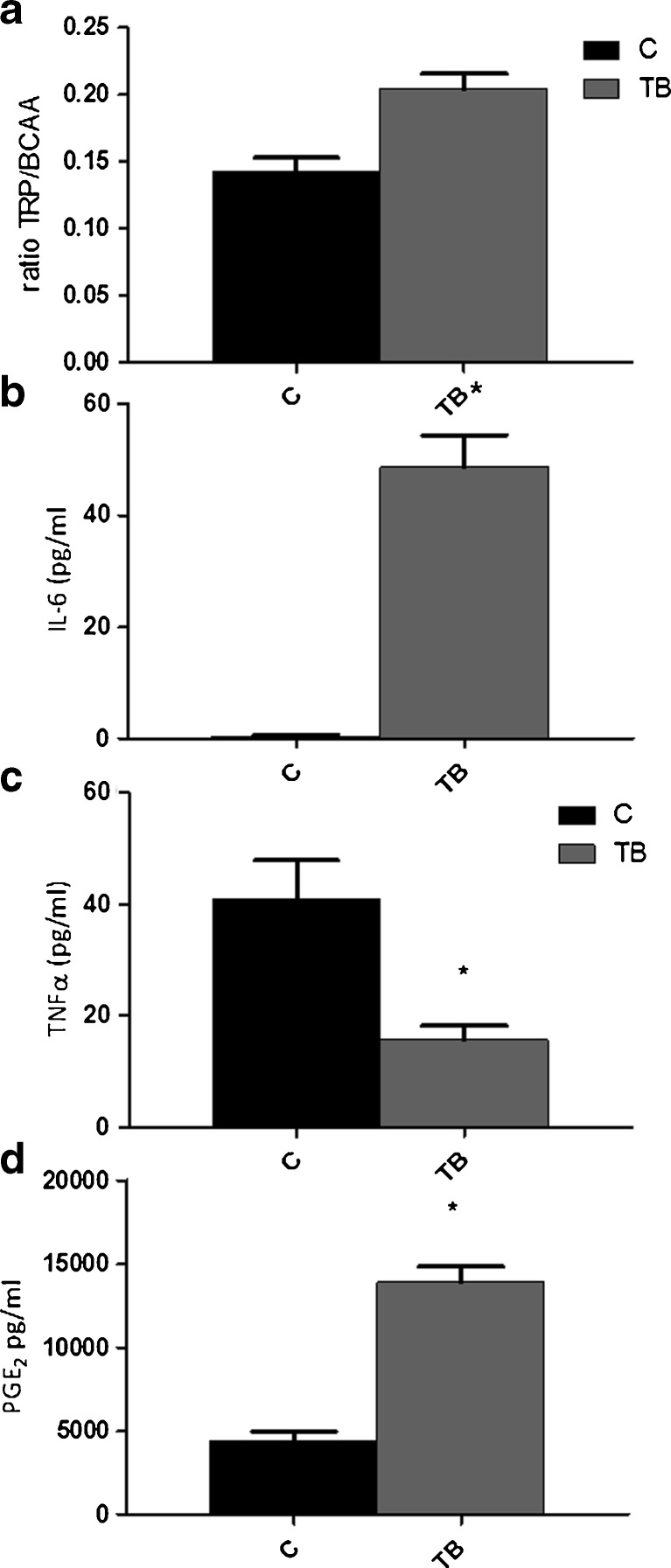

Plasma amino acid levels and immune parameters

In study B, levels of various amino acids in plasma were measured (Supplementary table S3). TRP levels relative to branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) is often used as a predictor for 5-HT status in the brain. Surprisingly, TRP/BCAA ratios showed to be significantly higher in TB animals compared to controls (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Ratio TRP/BCAA and cytokine plasma level in blood plasma. a Blood plasma amino acid levels in TB mice. b IL-6 plasma levels. c TNFα plasma levels. d PGE2 plasma levels. *P < 0.05 (significantly different from C). TRP tryptophan, BCAA branched-chain amino acids, comprising valine, leucine and isoleucine

To assess tumour-driven inflammatory response, PGE2, TNFα and IL-6 were measured in blood plasma (Fig. 4b–d). TNFα levels showed to decrease, while pro-inflammatory mediators IL-6 and PGE2 showed to be significantly elevated.

Discussion

In the present study, we report on the hypothalamic gene expression profile in C26 tumour-bearing mice that show an increase in food intake concomitant with body weight loss. It is likely that in these TB mice, hypothalamic appetite-regulating systems respond and adapt adequately to changes in energy balance resulting from tumour growth, although other causes for this compensatory eating behaviour (e.g. stress from the tumour) are difficult to exclude. At the same time, in situations where cancer anorexia develops food intake regulation seems to fail. By studying changes in the hypothalamus in response to disturbed energy balance during tumour growth, we aim to discover new targets for prevention or treatment of cancer anorexia.

Here, we show gene expressions of important orexigenic genes to be increased, while expression of anorexigenic genes decreased. Remarkable is the downregulation of the complete serotonin signalling cascade in TB mice. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that serotonin synthesis, degradation and synaptic release is affected during tumour growth and subsequent changes on serotonin levels are correlated to changes in food intake.

The observed increase in food intake in these C26 TB mice in both experiments has not yet been reported. The C26 cancer–cachexia mouse model as described in 1990 by Tanaka et al. [18] is often referred to as “the standard” for the C26 model. With this setup, cachexia develops, which is reflected in a decrease in muscle weight as well as adipose tissue depletion. Our findings on cachexia in the present model correspond to the results found by Tanaka et al. A specific characteristic for this model is that in this particular setting, food intake of TB mice does not change and is not different from that of healthy controls. However, in the meantime, various research groups have reported a strong decrease in food intake in mice injected with these C26 cancer cells [19, 20], suggesting that changes in morphology of the cell line, variation in the strain of mice and differences in number of tumour cells used for inoculation might lead to these discrepancies in findings on food intake. It has already been reported that C26-induced cachexia and anorexia can vary according to the inoculation site [21] and origin of C26 cells [22], as well as the use of solid tumour fragments or cell suspensions for inoculation can cause variation [23].

Also, adaptation of C26 cells to in vitro culture conditions can cause mutations in the cell line leading to changes in cell characteristics, sensitivity to chemotherapy, metastatic potential and tumour-induced cachexia in mice, suggesting that C26 cells can differentiate to different variants and change tumour characteristics despite being derived from the same source [24]. Subsequently, the extent and type of inflammatory response that is induced by tumour growth might play a role in the severity of cachexia and anorexia. Differences in tumour-driven inflammation, might therefore explain differences between various cancer models. To confirm tumour-induced inflammation in our model, various cytokines and PGE2 levels in blood plasma were measured. IL-6 and PGE2 showed to be elevated in TB mice, which also has been reported previously [25]. However, in contrast to previous results, TNFα levels in blood plasma were not elevated in TB mice compared to control mice.

Elevated concentrations of TNFα are reported to decrease food intake [26], suggesting that the absence of TNFα-mediated inflammation might play a role in compensating feeding behaviour in this model. All together, we would like to propose the hypothesis that although the “C26 model” is referred to as such, in fact the model is heterogeneous with many varieties. Small differences in experimental settings and spontaneous mutations in the cell line used might lead to great changes in characteristics of the model.

In the present study, pathway analysis indicates serotonin (5-HT) and dopamine (DA) signalling to be altered in TB mice compared to controls. DA and 5-HT are both important neurotransmitters involved in eating behaviour. The signalling pathways of 5-HT, DA and DA metabolites norepinephrine and epinephrine are closely linked by shared synthesising enzymes and transporters. Therefore, it is very likely that changes in these shared genes will propose these comprehensive effects. Since both pathways were predicted to be altered, we measured 5-HT and DA levels in whole brain homogenates. Serotonin levels were found to be significantly lower in TB mice compared to control. This might be caused by decreased TPH and SERT expression, which have been directly correlated to lowered 5-HT levels in other studies [27, 28]. However, DA levels in TB mice showed not to be different from levels in controls, suggesting that effects on expression of shared genes are of greater impact on 5-HT synthesis than on DA synthesis. In addition, in relation to changes in food intake in TB mice, only 5-HT levels showed to inversely correlate with food intake whereas DA levels did not. A limitation of the present setup is that gene pathway analysis was based on hypothalamic transcripts whereas analysis of 5-HT and DA levels took place in homogenates of remaining brain material. Therefore, levels of these neurotransmitters reflect an indication and local differences in the various regions of the brain in both DA and 5-HT cannot be ruled out.

Overall, our results suggest that primarily 5-HT is associated with altered food intake regulation caused by tumour growth. This is consistent with findings reported by other research groups. In MCA tumour-bearing rats which showed clear anorexia, 5-HT levels were elevated in the PVN of the hypothalamus [29]. This elevation of 5-HT showed to be clearly tumour-driven since it did not occur in the pair-fed controls. In addition, 5-HT levels were restored after tumour resection. On the other hand, also DA levels in the hypothalamus were reported to be decreased in that study. However, this decrease in DA level was also found in the pair-fed control group to a similar extent as observed in TB rats. This suggests that the decrease DA in the hypothalamus was a consequence and not a direct cause of decreased food intake. Dopamine has shown to play a role in mechanisms induced during and after feeding, such as rewarding mechanisms [30]. For example, DA levels in the hypothalamus have been shown to increase directly after eating and the magnitude of DA response is relative to the size of meal ingested [31]. Our results, together with the existing literature, suggest that DA is not a direct causative factor in the development of cancer anorexia since it is not induced by tumour growth but decreases subsequent to a reduction in food intake. However, DA is likely to play a role in sustaining cancer anorexia once this has been manifested. Long-term alterations in DA in the hypothalamus are suggested to affect feeding pattern [32] and treatment with L-dopa, precursor of DA, has been shown to be beneficial in restoring appetite in severely anorectic cancer patients [33]. In addition, an increase in hypothalamic expression of several DA receptors (DRD), including DRD2, during tumour growth in anorectic TB rats might play a role in sustainment of cancer anorexia [32]. Our results support this finding, as we found a decreased expression of this receptor in TB mice with compensatory feeding behaviour.

In summary, our results suggest that changes in 5-HT signalling and 5-HT levels contribute to compensatory eating during tumour growth. Serotonin is considered an important mediator in the regulation of satiety and hunger [34]. High brain levels induce satiation, whereas lowered levels stimulate food intake. In cancer, elevated brain serotonin has been suggested to play a crucial role in the development of anorexia [6, 29]. On the other hand, lowered serotonin levels and downregulation of SERT are discussed for their role in eating abnormalities and hyperphagia in obesity [35, 36].

Next to changes on 5-HT signalling and 5-HT levels, also tryptophan (TRP) metabolism appeared to change in TB mice. TRP/BCAA ratios in plasma showed to be increased in TB animals. TRP, precursor of 5HT, competes with BCAA at the blood brain barrier. Therefore, plasma TRP/BCAA ratio is used as predictor for 5-HT levels in the brain and is often linked to food intake. From this perspective, an elevated TRP/BCAA ratio would result in increased TRP availability for serotonin synthesis in the brain and subsequently higher brain 5-HT levels. However, inconsistencies in this theory have been reported. Several reports show that plasma TRP levels do not predict TRP in brain and consequently brain 5-HT levels [37, 38]. In addition, plasma TRP/BCAA ratio as predictor for changes in food intake [39], appetite [40] and satiety [41] has been reported to fail in several studies. Amino acid profiles in blood reflect skeletal muscle status and total protein metabolism in the body and is dependent on the physical status of the subject [42]. In the case of severe cachexia, it could be that large metabolic alterations in muscle [43] and the presence of insulin resistance in the muscle [44] might distort amino acid profiles in blood in order to predict brain 5-HT levels via TRP ratios adequately.

In the present study, various appetite regulators were studied for their role in the observed increased food intake in TB mice. AgRP and NPY expressions were highly upregulated in TB mice. Central infusion of AgRP in cachectic C26 tumour-bearing mice results in an increase in food intake [45], which supports our findings. However, increased expression of NPY and its relation to potentiate feeding in this study is more difficult to interpret, as messenger NPY has been reported to not correlate with NPY levels in the hypothalamus in cancer-cachectic conditions [46]. Several studies have shown that in cachectic and anorectic TB mice [47] and rats [46], messenger NPY is also elevated. However, translation of messenger NPY or transport of NPY to NPY terminals showed not to correspond to mRNA changes shown by measurements of NPY levels and immunohistochemistry [46]. Serotonin has been discussed to play a role in this imbalance between messenger NPY and NPY signalling in feeding behaviour in cancer anorexia [29]. Inhibition of 5-HT signalling showed to increase NPY levels [48], while induction of 5-HT signalling reduced NPY levels in rats [49].

All together, this suggests that 5-HT signalling can interfere with NPY synthesis or transport. Therefore, it could be that in the current study, decreased 5-HT levels and lowered 5-HT signalling might preserve NPY signalling.

In this study, we report on the transcriptomic analysis of a cancer-cachectic model with an increased food intake. In this model, appetite-regulating systems, of which failure might contribute to anorexia, are able to adapt properly to changes in energy balance. We showed that alterations in NPY, AgRP and serotonin signalling are likely to explain compensatory eating behaviour of mice bearing a C26 tumour. Therefore, targeting these systems might offer promising strategies to avoid the development of cancer-induced anorexia.

Electronic supplementary material

Top 5 Canonical pathways in mice bearing C26-adenocarcinoma Canonical pathway analysis with IPA (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com) revealed the serotonin receptor signalling pathway and the dopamine receptor signalling pathway as being significantly changed in tumour-bearing mice in both studies. A set of genes involved in serotonin signalling is also of importance in dopamine signalling. These overlapping genes are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, degradation of these neurotransmitters showed to be altered, since a specific set of genes including aldehyde dehydrogenases was downregulated. (JPEG 8 kb)

Differences in body weight and organ weight at day 20 after tumour inoculation in study A and B. C-26 cells were subcutaneously inoculated in CDF1 mice with different numbers of tumour cells. At day 20, organs were dissected and weighted. For skeletal muscles, the average of muscles from both legs was used for calculations. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Study A: C=sham injected control (n = 4), TB-0.5 = injected with 0.5 × 106 tumour cells (n = 4), TB-1 = injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells (n = 3). Study B: C = sham injected control (n = 6), TB= injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells (n = 9). * Significantly different from C (P < 0.05). EDL: m. extensor digitorum longus, m. gastroc: m. gastrocnemius, m.tib: m. tibialis anterior (DOCX 19 kb)

List of genes highly upregulated in the hypothalamus in TB groups in both study A and B. Upregulated genes in TB mice compared to control mice from study A and B that were injected with 1 million C-26 cells were compared. All genes with an induction fold above 1.5 were included. A list of 19 overlapping genes was revealed, showing genes that were highly upregulated in both studies. (DOCX 19 kb)

Plasma amino acid levels at day 20 in study B. Plasma levels of various amino acids were measured using HPLC. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. C = sham injected control, TB= injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells * Significantly different from C (P < 0.05). BCAA: (leucine, isoleucine, valine). LNAA: (isoleucine, leucine, valine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, histidine, methionine) EA: isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, histidine. Abbreviations: BCAA= branched-chain amino acids, LNAA=Large neutral amino acids, EA= essential amino acids. (DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicole Buurman, Gerrit de Vrij and Angeline Visscher for their technical support. The work presented in this manuscript was funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 266408 (Full4Health). The authors confirm that they comply with the principles of ethical publishing in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia, and Muscle 2010;1:7–8 (von Haehling S, Morley JE, Coats AJ and Anker SD).

Conflict of interest

M.V Boekschoten, M. Müller, J.M Argilès, A. Laviano and R.F Witkamp declare that they have no conflict of interest. J.T Dwarkasing is a guest employee and M.van Dijk, F.J Dijk, J. Faber and K.van Norren are employees of Nutricia Research, a medical nutrition company.

References

- 1.Argiles JM, et al. Optimal management of cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cancer Manag Res. 2010;2:27–38. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S7101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon K, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson JC, Clegg KE, Palmiter RD. Sensitivity to leptin and susceptibility to seizures of mice lacking neuropeptide Y. Nature. 1996;381:415–421. doi: 10.1038/381415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian S, et al. Neither agouti-related protein nor neuropeptide Y is critically required for the regulation of energy homeostasis in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5027–5035. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5027-5035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun Y, Ahmed S, Smith RG. Deletion of ghrelin impairs neither growth nor appetite. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7973–7981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.7973-7981.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laviano A, et al. NPY and brain monoamines in the pathogenesis of cancer anorexia. Nutrition. 2008;24:802–805. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Norren K, et al. Dietary supplementation with a specific combination of high protein, leucine, and fish oil improves muscle function and daily activity in tumour-bearing cachectic mice. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:713–722. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Eijk HM, Rooyakkers DR, Deutz NE. Rapid routine determination of amino acids in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with a 2–3 microns Spherisorb ODS II column. J Chromatogr. 1993;620:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)80062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin K, et al. MADMAX—management and analysis database for multiple omics experiments. J Integr Bioinform. 2011;8:160. doi: 10.2390/biecoll-jib-2011-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai M, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucl Acids Res. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irizarry RA, et al. Summaries of affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolstad BM, et al. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sartor MA, et al. Intensity-based hierarchical Bayes method improves testing for differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments. BMC Bioinforma. 2006;7:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Moses MA. Lipocalin 2: a multifaceted modulator of human cancer. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2347–2352. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavathia N, et al. Serum markers of apoptosis decrease with age and cancer stage. Aging. 2009;1:652–663. doi: 10.18632/aging.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomita T, Kimura S. Regulation of mouse Scgb3a1 gene expression by NF-Y and association of CpG methylation with its tissue-specific expression. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding M, Toth LA. mRNA expression in mouse hypothalamus and basal forebrain during influenza infection: a novel model for sleep regulation. Physiol Genomics. 2006;24:225–234. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00005.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka Y, et al. Experimental cancer cachexia induced by transplantable colon 26 adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2290–2295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iizuka N, et al. Anticachectic effects of the natural herb Coptidis rhizoma and berberine on mice bearing colon 26/clone 20 adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:286–291. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soda K, et al. Manifestations of cancer cachexia induced by colon 26 adenocarcinoma are not fully ascribable to interleukin-6. Int J Cancer J Int du Cancer. 1995;62:332–336. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto T, et al. Tumour inoculation site-dependent induction of cachexia in mice bearing colon 26 carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:764–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy KT, et al. Importance of functional and metabolic impairments in the characterization of the C-26 murine model of cancer cachexia. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:533–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Aulino P, et al. Molecular, cellular and physiological characterization of the cancer cachexia-inducing C26 colon carcinoma in mouse. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:363. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacchi A, Mauro F, Zupi G. Changes of phenotypic characteristics of variants derived from Lewis lung carcinoma during long-term in vitro growth. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1984;2:171–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00052417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faber J, et al. Beneficial immune modulatory effects of a specific nutritional combination in a murine model for cancer cachexia. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:2029–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonti G, Ilyin SE, Plata-Salaman CR. Anorexia induced by cytokine interactions at pathophysiological concentrations. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R1394–R1402. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman RB, et al. High-dose fenfluramine administration decreases serotonin transporter binding, but not serotonin transporter protein levels, in rat forebrain. Synapse. 2003;50:233–239. doi: 10.1002/syn.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, et al. Tryptophan hydroxylase-2 controls brain serotonin synthesis. Science. 2004;305:217. doi: 10.1126/science.1097540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meguid MM, et al. Tumor anorexia: effects on neuropeptide Y and monoamines in paraventricular nucleus. Peptides. 2004;25:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salamone JD, Correa M. Dopamine and food addiction: lexicon badly needed. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;73:e15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Meguid MM, Yang ZJ, Koseki M. Eating induced rise in LHA-dopamine correlates with meal size in normal and bulbectomized rats. Brain Res Bull. 1995;36:487–490. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)92128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato T, et al. Hypothalamic dopaminergic receptor expressions in anorexia of tumor-bearing rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1907–R1916. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.R1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozano RH, Jofre IS. Novel use of L-dOPA in the treatment of anorexia and asthenia associated with cancer. Palliat Med. 2002;16:548. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm612xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garfield AS, Heisler LK. Pharmacological targeting of the serotonergic system for the treatment of obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587:49–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.164152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratner C, et al. Cerebral markers of the serotonergic system in rat models of obesity and after roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:2133–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Wurtman RJ, Wurtman JJ. Brain serotonin, carbohydrate-craving, obesity and depression. Obes Res. 1995;3:477S–480S. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madras BK, et al. Elevation of serum free tryptophan, but not brain tryptophan, by serum nonesterified fatty acids. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1974;11:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molfino A, et al. Free tryptophan/large neutral amino acids ratios in blood plasma do not predict cerebral spinal fluid tryptophan concentrations in interleukin-1-induced anorexia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;89:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato T, et al. Involvement of plasma leptin, insulin and free tryptophan in cytokine-induced anorexia. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:139–146. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bossola M, et al. Anorexia and plasma levels of free tryptophan, branched chain amino acids, and ghrelin in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19:248–255. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koren MS, et al. Changes in plasma amino acid levels do not predict satiety and weight loss on diets with modified macronutrient composition. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:182–187. doi: 10.1159/000103323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newgard CB, et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9:311–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Argiles JM, et al. Catabolic mediators as targets for cancer cachexia. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:838–844. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02826-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asp ML, et al. Evidence for the contribution of insulin resistance to the development of cachexia in tumor-bearing mice. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:756–763. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joppa MA, et al. Central infusion of the melanocortin receptor antagonist agouti-related peptide (AgRP(83–132)) prevents cachexia-related symptoms induced by radiation and colon-26 tumors in mice. Peptides. 2007;28:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chance WT, et al. Alteration of NPY and Y1 receptor in dorsomedial and ventromedial areas of hypothalamus in anorectic tumor-bearing rats. Peptides. 2007;28:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nara-ashizawa N, et al. Response of hypothalamic NPY mRNAs to a negative energy balance is less sensitive in cachectic mice bearing human tumor cells. Nutr Cancer. 2001;41:111–118. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2001.9680621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dryden S, et al. Increased feeding and neuropeptide Y (NPY) but not NPY mRNA levels in the hypothalamus of the rat following central administration of the serotonin synthesis inhibitor p-chlorophenylalanine. Brain Res. 1996;724:232–237. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shinozaki T, et al. Fluvoxamine inhibits weight gain and food intake in food restricted hyperphagic Wistar rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:2250–2254. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Top 5 Canonical pathways in mice bearing C26-adenocarcinoma Canonical pathway analysis with IPA (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com) revealed the serotonin receptor signalling pathway and the dopamine receptor signalling pathway as being significantly changed in tumour-bearing mice in both studies. A set of genes involved in serotonin signalling is also of importance in dopamine signalling. These overlapping genes are shown in Fig. 3. In addition, degradation of these neurotransmitters showed to be altered, since a specific set of genes including aldehyde dehydrogenases was downregulated. (JPEG 8 kb)

Differences in body weight and organ weight at day 20 after tumour inoculation in study A and B. C-26 cells were subcutaneously inoculated in CDF1 mice with different numbers of tumour cells. At day 20, organs were dissected and weighted. For skeletal muscles, the average of muscles from both legs was used for calculations. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Study A: C=sham injected control (n = 4), TB-0.5 = injected with 0.5 × 106 tumour cells (n = 4), TB-1 = injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells (n = 3). Study B: C = sham injected control (n = 6), TB= injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells (n = 9). * Significantly different from C (P < 0.05). EDL: m. extensor digitorum longus, m. gastroc: m. gastrocnemius, m.tib: m. tibialis anterior (DOCX 19 kb)

List of genes highly upregulated in the hypothalamus in TB groups in both study A and B. Upregulated genes in TB mice compared to control mice from study A and B that were injected with 1 million C-26 cells were compared. All genes with an induction fold above 1.5 were included. A list of 19 overlapping genes was revealed, showing genes that were highly upregulated in both studies. (DOCX 19 kb)

Plasma amino acid levels at day 20 in study B. Plasma levels of various amino acids were measured using HPLC. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. C = sham injected control, TB= injected with 1 × 106 tumour cells * Significantly different from C (P < 0.05). BCAA: (leucine, isoleucine, valine). LNAA: (isoleucine, leucine, valine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, histidine, methionine) EA: isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, histidine. Abbreviations: BCAA= branched-chain amino acids, LNAA=Large neutral amino acids, EA= essential amino acids. (DOCX 17 kb)