Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to evaluate the antimicrobial efficiency of PDT and the effect of different irradiation durations on the antimicrobial efficiency of PDT.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty freshly extracted human teeth with a single root were decoronated and distributed into five groups. The control group received no treatment. Group 1 was treated with a 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution. Groups 2, 3, and 4 were treated with methylene-blue photosensitizer and 660-nm diode laser irradiation for 1, 2, and 4 min, respectively. The root canals were instrumented and irrigated with NaOCl, ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid, and a saline solution, followed by autoclaving. All the roots were inoculated with an Enterococcus faecalis suspension and brain heart infusion broth and stored for 21 days to allow biofilm formation. Microbiological data on microorganism load were collected before and after the disinfection procedures and analyzed with the Wilcoxon ranged test, the Kruskal-Wallis test, and the Dunn's test.

Results:

The microorganism load in the control group increased. The lowest reduction in the microorganism load was observed in the 1-min irradiation group (Group 2 = 99.8%), which was very close to the results of the other experimental groups (99.9%). There were no significant differences among the groups.

Conclusions:

PDT is as effective as conventional 5% NaOCl irrigation with regard to antimicrobial efficiency against Enterococcus faecalis.

Keywords: Enterococcus faecalis, irradiation duration, methylene blue, photodynamic therapy

INTRODUCTION

The primary objective of root canal treatment is to remove pulp tissue and dentinal debris and eliminate the bacteria from the root canal system. Currently, this procedure is carried out by a chemomechanical technique, which involves a combination of mechanical shaping with instruments and irrigation with chemical disinfectants. However, the complex anatomy of the root canal system hampers the elimination of bacteria and compromises the success of the root canal treatment even when the treatment has followed the proper technical procedure precisely.[1] Due to anatomical variations, such as anastomoses, isthmuses, and re-entrances, part of the root canal system often remains untouched, and the frequent occurrence of bacterial infection is a common cause of post-treatment failure.[2]

Besides mechanical shaping, irrigation with disinfectant solutions is the other standard application in root canal treatment procedures. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is currently the most commonly used irrigant in endodontics. It is an antimicrobial, tissue-dissolving, cheap, and easily available irrigant.[3] However, pure NaOCl does not offer an irrigation solution, because indiscriminate use of caustic chemicals such as NaOCl in the root canal increases the risk of cytotoxicity and neurotoxicity if the solution gets extruded into the periapical tissues through the root canal.[4,5,6] Chemical irrigation solutions applied during the instrumentation of the root canals act directly on the targeted bacteria. However, as mentioned earlier, the anatomical variations means that not all bacteria may be killed and debris and pulpal tissue remnants may remain.[7] In addition, because of the limited permeability of the disinfectant solutions in dentine tubules, bacteria in the deeper layers of dentin are unaffected by these chemicals.[8,9]

Several alternative disinfection methods, including lasers, have been explored and described to achieve complete disinfection in the root canal. With many of these lasers, the antibacterial effect is primarily based on dose-dependent heat generation, which can char dentin, ankylose roots, melt cementum, and cause root resorption, and periapical necrosis if the application procedure is not performed properly.[10,11,12] Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been introduced to overcome these risks. PDT sensitizes the bacteria with a photoactive agent (photosensitizer), which reacts with environmental molecular oxygen, resulting in the release of singlet oxygen and free radicals when exposed to light with a specific wavelength.[13,14]

In recent years, in vitro and in vivo disinfectant effects of PDT have been widely reported and documented. However, there is still little information on the influence of the duration of the light exposure.[15,16,17,18] Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of different light exposure durations on the antimicrobial effect of PDT. The hypothesis was that different light exposure durations significantly influence the antimicrobial effect of PDT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Ethics Committee of the University of Gaziantep approved the study protocol. The root segments of 60 freshly extracted human teeth with a single root (extracted for periodontal reasons) were decoronated and shortened to a standard length of 15 mm with a diamond disc. The canals were instrumented with hand files (Maillefer Instruments SA, Ballaigues, Switzerland) using the crown-down technique, 1-mm short of the working length (WL), to a #45 master apical file (Maillefer Instruments SA). The root canals were irrigated with 2 mL of 1% NaOCl solution after the instrumentation with each file. The NaOCl (1%) was delivered with a 30-gauge needle. At the end of the procedure, the root canals were irrigated with 5 mL of 17% ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid for 3 min to remove the smear layer, followed by irrigation with 5 mL of a sterile saline solution to remove the residues of the chemical adjuncts used during instrumentation. The specimens were then autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min.

Inoculation of Enterococcus faecalis and biofilm formation

A final suspension of 20 lL of Enetrococus faecalis (2.58 × 108 colony forming units (CFU)/mL) was injected into the root canal of each specimen using a 0.3-cc insulin needle (BD Ultra-Fine, NJ). Subsequently, each specimen was placed in a well and fully covered with cotton pellets and then wetted in sterile distilled water to ensure a moist environment. The samples and the test apparatus were kept at 5% CO2 and 37°C for 21 days. To maintain the microorganisms in the exponential phase for the formation of biofilm, 20 lL of fresh brain heart infusion (BHI) broth were added every 2 days to the canals, and the cotton pellets in the wells were replenished. The root canals were irrigated with 1 mL of saline solution and sampled before and after the testing procedures. The specimens were taken using sterile paper points #20 (Protaper F3, Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) placed at the working length. The paper points were transferred to an Eppendorf tube. After vortexing the tubes for 30 s, serial dilutions of the contents were prepared, and 0.1 mL aliquots were spread over the surfaces of the BHI agar plates that were stored under 5% CO2 for 24 h. After incubation, the colonies were counted to determine the initial (T1) CFU/mL of viable cells of the experimental and the control groups.

Testing procedures

The 60 specimens were randomly distributed into five groups (n = 12): One control group (control: untreated), one conventionally treated group (Group 1: 5% NaOCl), and three groups treated with PDT using three different application times (Group 2: 1 min; Group 3: 2 min, Group 4: 4 min).

In the conventionally treated group (Group 1), a standardized irrigation protocol was used. A 30-gauge needle was placed at the working length, and 10 mL of 5% NaOCl was delivered to the specimen over a period of 15 min.

In the PDT test groups, the canals of all the specimens in the experimental groups were filled with 70 μL of sterile, single-use methylene blue (MB) (Helbo Endo Blue Phenotiazine-5-ium, 3,7-bis (dimethylamino)-, chloride) photosensitizer. The photosensitizer was left in place for 1 min and then the specimens were rinsed with H2O. The irradiation was performed with a 660-nm diode laser device (Helbo TheraLite Laser) using an intracanal optical fiber (Helbo 3D Endo fiber) with three exposure times (1, 2, and 4 min). Immediately after the testing procedures, the contents of the root canals were collected, diluted, and plated, as previously described. After incubation for 24 h, the number of viable cells (CFU/mL) from each specimen was calculated (T2).

Statistical analysis

The microbiological data (CFU/mL) were analyzed using the Wilcoxon ranged test for intragroup analysis (T1 to T2). The Kruskal-Wallis test, complemented by Dunn's test, was used for the intergroup comparative analysis of the percentage reductions. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 19, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

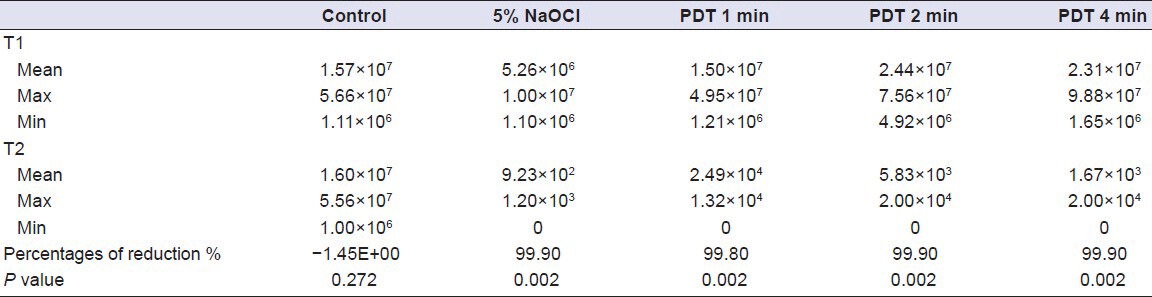

The test results of all the groups are presented in Table 1. The intragroup analyses, which were performed to evaluate the microbiological data (CFU/mL) before and after the disinfection procedures showed that all the disinfection procedures significantly reduced the number of viable cells (Wilcoxon ranged test, P < 0.05). In the control group, the number of viable cells (CFU/mL) was increased.

Table 1.

Bacterial counts and reduction rates in the experimental groups

The lowest percentage of bacterial reduction was observed in Group 2 (1 min = 99.8%), which was very close to the results of the other experimental groups (99.9%). The intergroup comparisons (Kruskal- Wallis test, Dunn's test) revealed that there were no significant differences among the groups (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study compared the influence of various irradiation durations on the antimicrobial effect of PDT. The hypothesis that there would be significant differences among the experimental groups was rejected.

In this study, the root canal system was contaminated with E. faecalis. E. faecalis is a facultative, anaerobic, and gram-positive bacterium, which has been isolated from infected root canals. It is considered as one of the most resistant species of oral cavity flora and a possible cause of post-treatment failure.[19] This microorganism penetrates deep into dentinal tubules, leads to gross infection, and may also reside in canals as a single species without assistance of the other microorganisms.[20,21] Studies have shown that E. faecalis can form a biofilm and survive in the harsh environment of the root canal and that it could be resistant to NaOCl, chlorhexidine, calcium hydroxide, and several antibiotics.[22,23,24,25]

The current study showed that PDT significantly decreases (99.80% to 99.90%) the load of microorganisms in infected root canals. In addition, the bacterial load reduction results of the PDT groups and the 5% NaOCl irrigation group (99.90%) were comparable, showing that PDT is as efficient as conventional NaOCl irrigation in preventing E. faecalis infection of root canals. Some studies in the literature have compared the antimicrobial effect of PDT and NaOCl at different concentrations and have reported controversial results. Garcez et al.,[15] reported that PDT was more effective than 0.5% NaOCl, whereas Seal et al.,[26] and Meire et al.,[27] found that NaOCl was more effective at concentrations of 2.5% and 3%. In a study of the efficiency of NaOCl versus PDT, Nunes et al.,[28] reported similar results to the current study. The differences in these reports may be related to the variety of methods used in the studies in addition to the NaOCl concentrations and the PDT procedures.

In the current study, altering the duration of the light exposure did not significantly influence the bacterial reduction. Despite increasing the irradiation dose in Group 3 (2 min), the antimicrobial effect of PDT was slightly greater when compared to that in Group 2 (1 min), but the difference was not significant. In contrast to the current study, some studies have reported significant positive effects on the bacterial load when the total energy dose was raised by increasing the duration of irradiation.[17,26,29] However, the bacteria species used and the photosensitizers tested in these studies differ from those in the current study. Some studies reported similar findings to the present study. Nunes et al.,[28] used MB and a 660-nm diode laser for PDT and reported comparable antimicrobial efficiency results for groups exposed to irradiation for 90 s and 180 s.

In the current study, none of the disinfection methods tested could eliminate all the bacteria in the root canal. It is known that disinfectant solutions kill the bacteria upon direct contact and that penetration of the NaOCl solution in the dentinal tubules is limited to approximately 130 μm.[8] Tubular infection may occur at depths of up to 1000 μm.[30] This limitation of penetration could prevent the total elimination of bacteria with NaOCl irrigation. On the other hand, microscopic studies have shown that MB can infiltrate the dentinal tubules and that light can propagate in the dentin through the dentinal tubules.[31,32,33,34,35] In spite of this advantage, PDT did not totally eliminate the bacteria in the present study in common with previous studies.[15,16] The limited availability of environmental oxygen may explain this finding. Foschi et al.,[13] suggested that PDT causes oxygen depletion during irradiation and that the limited oxygen supply in dentinal tubules leads to a greater rate of oxygen consumption than reperfusion in the photochemical reaction. Zijp and Bosch[35] reported that the oxygen concentration in the root canal, especially in irregularities and in dentinal tubules, is relatively low and that, therefore, the formation of oxygen derivatives is restricted.

The factors responsible for the antimicrobial effects of PDT, including the penetration of the photosensitizers into the root canal system and the range of free-radical activity, have not been investigated in the current study. Further studies should be carried out to investigate the clinical use of the proposed protocol and its effects on the periapical tissues.

On the basis of the results of this study, the following was concluded:

With regard to the antimicrobial efficiency against E. faecalis, PDT is as effective as conventional 5% NaOCl irrigation

Irradiation for 1 min is sufficient to achieve the antimicrobial effect of PDT.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Siqueira JF, Jr, Araujo MC, Garcia PF, Fraga RC, Dantas CJ. Histological evaluation of the effectiveness of five instrumentation techniques for cleaning the apical third of root canals. J Endod. 1997;23:499–502. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byström A, Happonen RP, Sjögren U, Sundqvist G. Healing of periapical lesions of pulpless teeth after endodontic treatment with controlled asepsis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1987;3:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1987.tb00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izu KH, Thomas SJ, Zhang P, Izu AE, Michalek S. Effectiveness of sodium hypochlorite in preventing inoculation of periapical tissues with contaminated patency files. J Endod. 2004;30:92–4. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200402000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim Z, Cheng JL, Lim TW, Teo EG, Wong J, George S, et al. Light activated disinfection: An alternative endodontic disinfection strategy. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:108–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang YC, Huang FM, Tai KW, Chou MY. The effect of sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine on cultured human periodontal ligament cells. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:446–50. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.116812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grigoratos D, Knowles J, Ng YL, Gulabivala K. Effect of exposing dentine to sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide on its flexural strength and elastic modulus. Int Endod J. 2001;34:113–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2001.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byström A, Sundqvist G. Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Scand J Dent Res. 1981;89:321–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1981.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berutti E, Marini R, Angeretti A. Penetration ability of different irrigants into dentinal tubules. J Endod. 1997;23:725–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen BH, Akdeniz BG, Denizci AA. The effect of ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid on Candida albicans. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:651–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.109640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahcall JK, Miserendino L, Walia H, Belardi DW. Scanning electron microscopic comparison of canal preparation with Nd: YAG laser and hand instrumentation: A preliminary study. Gen Dent. 1993;41:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardee MW, Miserendino LJ, Kos W, Walia H. Evaluation of the antibacterial effects of intracanal Nd: YAG laser irradiation. J Endod. 1994;20:377–80. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(06)80294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsköld LO, Fong CD, Stromberg T. Thermal effects and antibacterial properties of energy levels required to sterilize stained root canals with an Nd: YAG laser. J Endod. 1997;23:96–100. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foschi F, Fontana CR, Ruggiero K, Riahi R, Vera A, Doukas AG, et al. Photodynamic inactivation of Enterococcus faecalis in dental root canals in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:782–7. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchat M, Spikes JD, Bertoloni G, Jori G. Studies on the mechanism of bacteria photosensitization by meso-substituted cationic porphyrins. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;35:149–57. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcez AS, Nunez SC, Lage-Marques JL, Jorge AO, Ribeiro MS. Efficiency of NaOCl and laser-assisted photosensitization on the reduction of Enterococcus faecalis in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soukos NS, Chen PS, Morris JT, Ruggiero K, Abernethy AD, Som S, et al. Photodynamic therapy for endodontic disinfection. J Endod. 2006;32:979–84. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JA, Pearson GJ, Colles MJ. Antibacterial action of photoactivated disinfection (PAD) used on endodontic bacteria in planktonic suspension and in artificial and human root canals. J Dent. 2006;34:363–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcez AS, Ribeiro MS, Tegos GP, Nunez SC, Jorge AO, Hamblin MR. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy combined with conventional endodontic treatment to eliminate root canal biofilm infection. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:59–66. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes BP, Lilley JD, Drucker DB. Variations in the susceptibilities of components of the endodontic microflora to biomechanical procedures. Int Endod J. 1996;29:235–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.1996.tb01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dametto FR, Ferraz CC, Gomes BP, Zaia AA, Teixeira FB, Souza-Filho FJ. In vitro assessment of the immediate and prolonged antimicrobial action of chlorhexidine gel as an endodontic irrigant against Enterococcus faecalis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:768–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinheiro ET, Gomes BP, Ferraz CC, Sousa EL, Teixeira FB, Souza-Filho FJ. Microorganisms from canals of root-filled teeth with periapical lesions. Int Endod J. 2003;36:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Distel JW, Hatton JF, Gillespie MJ. Biofilm formation in medicated root canals. J Endod. 2002;28:689–93. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200210000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: Its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buck RA, Eleazer PD, Staat RH, Scheetz JP. Effectiveness of three endodontic irrigants at various depths in human dentin. J Endod. 2001;27:206–8. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200103000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlen G, Samuelsson W, Molander A, Reit C. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility of enterococci isolated from the root canal. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15:309–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2000.150507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seal GJ, Ng YL, Spratt D, Bhatti M, Gulabivala K. An in vitro comparison of the bactericidal efficacy of lethal photosensitization or sodium hypochlorite irrigation on Streptococcus intermedius biofilms in root canals. Int Endod J. 2002;35:268–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2002.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meire MA, De Prijck K, Coenye T, Nelis HJ, De Moor RJ. Effectiveness of different laser systems to kill Enterococcus faecalis in aqueous suspension and in an infected tooth model. Int Endod J. 2009;42:351–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunes MR, Mello I, Franco GC, de Medeiros JM, Dos Santos SS, Habitante SM, et al. Effectiveness of photodynamic therapy against Enterococcus faecalis, with and without the use of an intracanal optical fiber: An in vitro study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29:803–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prates RA, Yamada AM, Jr, Suzuki LC, Eiko Hashimoto MC, Cai S, Gouw-Soares S, et al. Bactericidal effect of malachite green and red laser on Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2007;86:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters LB, Wesselink PR, Buys JF, van Winkelhoff AJ. Viable bacteria in root dentinal tubules of teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2001;27:76–81. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George S, Kishen A. Photophysical, photochemical, and photobiological characterization of methylene blue formulations for light-activated root canal disinfection. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:034029. doi: 10.1117/1.2745982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentine hypersensitivity. A study of the patency of dentinal tubules in sensitive and nonsensitive cervical dentine. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:280–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Absi EG, Addy M, Adams D. Dentin hypersensitivity: The development and evaluation of a replica technique to study sensitive and non-sensitive cervical dentin. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:190–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb01639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kienle A, Forster FK, Diebolder R, Hibst R. Light propagation in dentin: Influence of microstructure on anisotropy. Phys Med Biol. 2003;21:N7–14. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/48/2/401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zijp JR, Bosch JJ. Theoretical model for the scattering of light by dentin and comparison with measurements. Appl Opt. 1993;32:411–5. doi: 10.1364/AO.32.000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]