Abstract

Background

Traditionally inhaled treatment for asthma has been considered as preventer and reliever therapy. The combination of formoterol and budesonide in a single inhaler introduces the possibility of using a single inhaler for both prevention and relief of symptoms (single inhaler therapy).

Objectives

The aim of this review is to compare formoterol and corticosteroid in single inhaler for maintenance and relief of symptoms with inhaled corticosteroids for maintenance and a separate reliever inhaler.

Search methods

We last searched the Cochrane Airways Group trials register in September 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials in adults and children with chronic asthma.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion and extracted the characteristics and results of each study. Authors or manufacturers were asked to supply unpublished data in relation to primary outcomes.

Main results

Five studies on 5,378 adults compared single inhaler therapy with current best practice, and did not show a significant reduction in participants with exacerbations causing hospitalisation (Peto OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.45) or treated with oral steroids (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.03). Three of these studies on 4281 adults did not show a significant reduction in time to first severe exacerbation needing medical intervention (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.07). These trials demonstrated a reduction in the mean total daily dose of inhaled corticosteroids with single inhaler therapy (mean reduction ranged from 107 to 267 micrograms/day, but the trial results were not combined due to heterogeneity). The full results from four further studies on 4,600 adults comparing single inhaler therapy with current best practice are awaited.

Three studies including 4,209 adults compared single inhaler therapy with higher dose budesonide maintenance and terbutaline for symptom relief. No significant reduction was found with single inhaler therapy in the risk of patients suffering an asthma exacerbation leading to hospitalisation (Peto OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.09), but fewer patients on single inhaler therapy needed a course of oral corticosteroids (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.64). These results translate into an eleven month number needed to treat of 14 (95% CI 12 to 18), to prevent one patient being treated with oral corticosteroids for an exacerbation. The run-in for these studies involved withdrawal of long-acting beta2-agonists, and patients were recruited who were symptomatic during run-in.

One study included children (N = 224), in which single inhaler therapy was compared to higher dose budesonide. There was a significant reduction in participants who needed an increase in their inhaled steroids with single inhaler therapy, but there were only two hospitalisations for asthma and no separate data on courses of oral corticosteroids. Less inhaled and oral corticosteroids were used in the single inhaler therapy group and the annual height gain was also 1 cm greater in the single inhaler therapy group, [95% CI 0.3 to 1.7 cm].

There was no significant difference found in fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events for any of the comparisons.

Authors’ conclusions

Single inhaler therapy can reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations needing oral corticosteroids in comparison with fixed dose maintenance inhaled corticosteroids. Guidelines and common best practice suggest the addition of regular long-acting beta2-agonist to inhaled corticosteroids for uncontrolled asthma, and single inhaler therapy has not been demonstrated to significantly reduce exacerbations in comparison with current best practice, although results of five large trials are awaiting full publication. Single inhaler therapy is not currently licensed for children under 18 years of age in the United Kingdom.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): Administration, Inhalation, AdrenalCortexHormones [*administration & dosage], Anti-Asthmatic Agents [*administration & dosage], Asthma [*drug therapy], Bronchodilator Agents [administration & dosage], Budesonide [*administration & dosage], Chronic Disease, Drug Therapy, Combination, Ethanolamines [*administration & dosage], Terbutaline [administration & dosage]

MeSH check words: Adult, Child, Humans

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

There is currently no universally accepted definition of the term ’asthma’. This is in part due to an overlap of symptoms with other diseases such as chronic bronchitis, but is also due to the probable existence of more than one underlying pathophysiological process. There are, for example, wide variations in the age of onset, symptoms, triggers, association with allergic disease and the type of inflammatory cell infiltrate seen in patients diagnosed with asthma. Patients will typically all have intermittent symptoms of cough, wheeze and/or breathlessness. Underlying these symptoms there is a process of variable, at least partially reversible airway obstruction, airway hyper responsiveness and (with the possible exception of solely exercise-induced asthma) chronic inflammation.

Description of the intervention

People with persistent asthma can use preventer therapy (usually low dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)) to maintain symptom control, improve lung function and reduce emergency care requirement. However, when symptoms deteriorate reliever medication in the form of short-acting beta-agonists such as salbutamol or terbutaline, or formoterol (a fast-acting but longer lasting formulation) can be used on an ‘as needed’ basis (BTS/SIGN 2008). Since most exacerbations have an onset over several days (Tattersfield 1999) there is potential for the person with asthma to increase both budesonide and formoterol at an early stage in response to increased symptoms of asthma. The pharmacological properties of another long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA), salmeterol, result in slower onset of bronchodilation (Palmqvist 2001), and it is not licensed for use on an ‘as needed’ basis. The inclusion of ICS in a reliever inhaler for use during episodes of loss of control requires monitoring and assessment of overall ICS dose (BTS/SIGN 2008).

How the intervention might work

The combination of ICS and LABA in one inhaler is an effective way of delivering maintenance anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator therapy in chronic asthma (Greenstone 2005; Ni Chroinin 2005). The anti-inflammatory properties of the ICS and the bronchodilatory effect of the LABA play complementary roles in reducing inflammation in the airways and improving lung function with relief of symptoms related to bronchospasm (Adams 2008; Walters 2007). Both are recommended when low dose ICS alone is not sufficient to control asthma, which is at step three in British asthma guidelines (BTS/SIGN 2008). Concerns have been raised about the use of single inhaler LABA in chronic asthma, in particular where it is used without a regular ICS, in relation to the possible increased risk of severe adverse events and asthma-related death (Cates 2008; Cates 2008a; Walters 2007). The concomitant delivery of ICS and LABA avoids the inadvertent use of LABA without prescribed ICS treatment.

Why it is important to do this review

It is recognised that many patients who are prescribed ICS do not continue to take the treatment in clinical practice, and combination inhalers can increase ICS use both as maintenance Delea 2008 and single inhaler therapy Sovani 2008. Whilst the trials which have investigated doubling the dose of ICS early in exacerbations have been disappointing (FitzGerald 2004, Harrison 2004), there is the potential with single inhaler therapy for the patient to automatically increase both LABA and ICS when their asthma is worse and cut down again as their symptoms improve. This holds out the prospect of maintaining control of asthma and preventing exacerbations with lower overall exposure to ICS.

This review has identified and summarised clinical trials that compare single inhaler therapy for maintenance and relief with budesonide/formoterol against maintenance with ICS and a separate reliever therapy.

OBJECTIVES

To assess the efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in a single inhaler to be used for both maintenance and reliever therapy in asthma in comparison to maintenance with inhaled corticosteroids (alone or as part of current best practice) and any reliever therapy.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials of parallel group design have been included in the review.

Types of participants

Adults and children with a diagnosis of chronic asthma. We accepted trialist-defined asthma, recording the definition of asthma used in the studies, and the entry criteria. We have summarised baseline severity of lung function and persistence of symptoms, and we collected data on pre-study maintenance therapies. We did not include studies conducted in an emergency department setting.

Types of interventions

Eligible treatment group intervention

This review included studies which have assessed the effects of using a combined inhaled steroid and long-acting beta2-agonist delivered through a single inhaler device for regular maintenance and the relief of asthma symptoms.

Eligible control group treatment

The control groups for the studies in this review consisted of a prescribed inhaled corticosteroid given as regular maintenance treatment with a separate reliever inhaler.

Study duration was at least 12 weeks.

We did not consider studies that compared different combination therapy inhalers (regular seretide versus regular symbicort has been reviewed elsewhere Lasserson 2008), or titration of maintenance dosing of combination therapy based on clinical signs and symptoms.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Patients with exacerbations requiring hospitalisation

Patients with exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids

Serious adverse events (including mortality and life-threatening events)

Growth (in children)

Secondary outcomes

Severe Exacerbations (composite outcome of hospitalisation/ER visit/oral steroid course)

Diary card morning and evening peak expiratory flow (PEF)

Clinic spirometry (FEV1)

Number of rescue medication puffs required per day

Symptoms/Symptom-free days

Nocturnal awakenings

Quality of life

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. All records in the Specialised Register coded as ‘asthma’ were searched using the following terms: (“single inhaler therapy” or SiT or SMART or relie* or “as need*” or as-need* or prn or flexible or titrat*) and ((combin* or symbicort or viani) or ((steroid* or corticosteroid* or ICS or budesonide or BUD or Pulmicort or beclomethasone or BDP or becotide) and (“beta*agonist” or “beta*adrenergic agonist” or formoterol or eformoterol or oxis or foradil)))

Date of last search was September 2008

Searching other resources

We contacted trialists and manufacturers in order to confirm data and to establish whether other unpublished or ongoing studies are available for assessment. We hand-searched clinical trials web sites (www.clinicalstudyresults.org; www.clinicaltrials.gov; www.fda.gov) and the clinical trial web sites of combination inhaler manufacturers (www.ctr.gsk.co.uk; www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Following electronic literature searches, two review authors (CC & TL) independently selected articles on the basis of title and/or abstract for full text scrutiny. The authors agreed a list of articles which were retrieved, and subsequently assessed each study to determine whether it was a secondary publication of a primary study publication, and to determine whether the study met the entry criteria of the review.

Data extraction and management

We extracted information from each study for the following characteristics:

Design (description of randomisation, blinding, number of study centres and location, number of study withdrawals).

Participants (N, mean age, age range of the study, gender ratio, baseline lung function, % on maintenance ICS or ICS/LABA combination & average daily dose of steroid (BDP equivalent), entry criteria).

Intervention (type and dose of component ICS and LABA, control limb dosing schedule, intervention limb dose adjustment schedule, inhaler device, study duration & run-in)

Outcomes (type of outcome analysis, outcomes analysed)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed trial bias protection in the following domains study quality according to whether studies meet the following pre-specified quality criteria (as met, unmet or unclear, Higgins 2008):

Sequence Generation

Allocation Concealment

Blinding of participants and investigators

Loss to follow-up

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted data for each of the outcomes considered by the review from the trial publication(s) or from correspondence with trialist or manufacturer. Exacerbations were the primary outcome for this review and were reported by subtype (hospitalisation and courses of oral steroids), rather than just as a composite outcome. Serious adverse events were considered separately as fatal and non-fatal events.

Unit of analysis issues

We sought to obtain data from the trial sponsors that is reported with patients (rather than events) as the unit of analysis for the primary outcomes. Some patients may have suffered more than one exacerbation over the course of the studies and these events are not independent.

Data synthesis

Data were combined with RevMan 5.0, using a fixed effect mean difference (calculated as a weighted mean difference) for continuous data variables, and a fixed effect Odds Ratio for dichotomous variables. When zero cells were present for an outcome in any of the included studies the Peto Odds Ratio was used to combine the results as it does not require a continuity correction to be used. For the primary outcomes of exacerbations and serious adverse events, when a significant Odds Ratio was found, we calculated an NNT(benefit or harm) for the different levels of risk as represented by control group event rates over a specified time period using the pooled Odds Ratio and its confidence interval (Visual Rx).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We pooled the data from adults and children in subgroups. Adult studies were considered as those which recruited participants from 18 years of age upwards. Adult and adolescent studies were considered as those which recruit participants from 12 years of age upwards. We considered participants in studies where the upper age limit was 12 years as children, and in studies where the upper age limit was 18 years as children and adolescents. Subgroup analysis were not possible in relation to asthma severity and degree of control of symptoms at baseline.

We measured statistical variation between combined studies by the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Where this exceeded 20% we will investigate the heterogeneity found, before deciding whether to combine the study results for the outcome.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis were planned on the basis of risk of bias in studies and methods of data analysis (fixed and random effects models).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

The search was last carried out in September 2008 and included 198 citations. From these 51 were retrieved as full text articles, representing 24 unique studies. There were 10 studies (21 citations) included in the review and 14 studies (31 citations) that were excluded. Full details are given in the lists of Included studies and Excluded studies. Four further ongoing studies have been identified from handsearching clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00463866; NCT00628758; SYMPHONIE 2008; SPAIN 2008).

Included studies

All of the studies were on adults and adolescents with the exception of STAY - Children, in which the results from the 224 children included in the STAY study were reported in a separate paper by Bisgaard. This has therefore been regarded separately from STAY - Adults which reported the adult results from the STAY study. The active treatment in most studies was budesonide/formoterol 160/4.5 mcg 1 Inhalation twice daily plus as-needed; this is the delivered dose and is the same as 200/6 mcg actuator dose described in some of the studies. In STEAM the maintenance treatment dose was the same but was given as two inhalations in the evening, and in STAY - Children the maintenance dose was budesonide/formoterol 160/4.5 mcg one inhalation in the evening.

Of the 10 adult studies, six studies compared single inhaler therapy (SiT) to current best practice; these were DE-SOLO; MONO; NCT00235911; SALTO; SOLO; STYLE. In these studies long-acting beta2-agonists were allowed in the control arm, and many of the participants were already using long-acting beta2-agonists. The other four studies compare SiT to inhaled corticosteroids as maintenance and terbutaline as reliever (Scicchitano 2004; STAY - Adults; STEAM; Sovani 2008) and of these, the first three compared SiT to a higher dose of maintenance ICS. In these studies long-acting beta2-agonists were not allowed in the control arm, and were withdrawn from those patients previously taking them.Sovani 2008 compared to the same dose of ICS (as the main aim of this study was to assess compliance with ICS).

Two large completed studies have not yet been reported in a paper publication or on the sponsors web site of controlled trials. DE-SOLO aimed to randomise 1600 participants and STYLE 1000 participants. Both compared SiT to current best practice so for this comparison the results from 2600 patient remain unpublished out of 7000 patients who have completed trials, although for the purpose of this review AstraZeneca have provided data on file for the primary exacerbation outcomes from STYLE. There are also three studies of similar size that are nearing completion and will report on a further 3000 patients in comparison to current best practice (NCT00628758; SPAIN 2008; SYMPHONIE 2008). The reported mean daily dose of inhaled corticosteroids previously used by participants was high in most of the studies: MONO (1035 mcg), SALTO (579 mcg), Scicchitano 2004 (746 mcg), SOLO (569 mcg), Sovani 2008 (590 mcg, but poor compliance was an inclusion criterion), STAY - Adults (660 mcg), STAY - Children (315 mcg). The mean daily dose was lower in STEAM (340 mcg) and is not available from the other three studies (DE-SOLO; NCT00235911; STYLE).

Inclusion criteria for DE-SOLO and SOLO were that the participants had to be stable on a combination of LABA and ICS or symptomatic on ICS maintenance, and MONO and SOLO reported that 74% to75% of participants had previously taken LABA as well as ICS before the trial. Scicchitano 2004, STAY-Adults, and STAY - Children included participants who had suffered a clinically important exacerbation in the previous year. InSALTO 27% of patients were reported to have mild persistent asthma, 37% moderate persistent and 36% severe persistent. Some studies included a run-in of about two weeks in which LABA was withdrawn (Scicchitano 2004; STAY - All ages; STEAM) and in the case of STEAM, the maintenance dose of ICS was reduced from an average of 350 mcg/day to 200 mcg/day as well, and in order to secure “a symptomatic population that could respond differently to different treatments, patients were required to have at least 7 inhalations of as-needed medication during the last 10 days of the run-in period”. SALTO and SOLO continued usual therapy over the two week run-in period, but details of any runin period are not currently available for the other studies.

The primary outcomes for the studies are shown in the Characteristics of included studies. For the majority of studies this was time to first severe asthma exacerbation, which usually included hospitalisation, visits to an emergency department, a course of oral steroids and sometimes a 30% drop in peak expiratory flow (PEF) such as in Scicchitano 2004; STEAM; STAY - Adults; STAY - Children. The definition of severe exacerbation was not specified in the current reports of DE-SOLO; MONO; NCT00235911; SALTO or STYLE. Sovani 2008 had a different design from the other studies and the primary outcome was the dose of inhaled corticosteroids.

All of the studies (apart from Sovani 2008 and possibly NCT00235911) are multi-centre studies, and no information has been found in relation to differences between centres or countries in any of these trials.

Excluded studies

The reasons for the exclusion of 14 studies is documented in the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

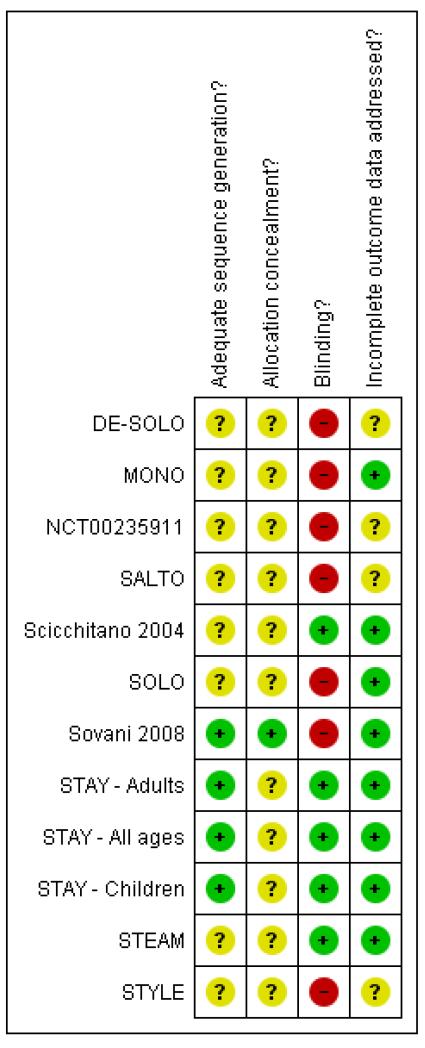

The overview of risk of bias is shown in Figure 1

Figure 1. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Few details are reported in relation to sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Blinding

The studies comparing SiT with current best practice are un-blinded, whilst those comparing with higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids are double-blind. Sovani 2008 was also unblinded as adherence was the primary outcome for this study.

Incomplete outcome data

The trial reports are clear about the proportion of randomised patients who were analysed in MONO; Scicchitano 2004; SOLO; STAY - All ages; Sovani 2008, and the dropout rate does not raise serious concerns.

Selective reporting

Missing trial reports

No reported results have been found for two large studies including around 2,600 participants (DE-SOLO; STYLE) out of around 7,000 patients comparing SiT to current best practice. Moreover two other studies for this comparison have only been reported in the form of a summary on the sponsors’ trial register (MONO;SALTO).

Missing details of outcome data

Publication bias is a problem from the web reports which do not present sufficient information to use for many outcomes. Hospitalisations tend to be reported as part of a combined outcome of “severe” asthma exacerbation and are much rarer than courses of oral corticosteroids. Separate outcome data for patients with at least one asthma hospitalisation (or asthma SAE) and patients with at least one course of oral corticosteroids have been requested from the sponsor and have been obtained from MONO; Scicchitano 2004; STAY - Adults; STEAM; NCT00235911 and STYLE.

Other potential sources of bias

All of the included studies are sponsored or supported by AstraZeneca, the manufacturers of Symbicort.

Effects of interventions

The primary outcomes for this review are exacerbations leading to hospitalisation, exacerbations treated with a course of oral corticosteroids and serious adverse events. In general the trials have reported composite outcomes that include the above types of exacerbation combined with Emergency Room (ER) visits and sometimes a 30% drop in peak flow. We have obtained data on our primary outcomes from the trial sponsors. Most of the studies are also multi-site randomised controlled trials and have not reported data from any of the individual sites.

Adults and Adolescents treated with Single inhaler Therapy compared to current best practice

Primary Outcomes

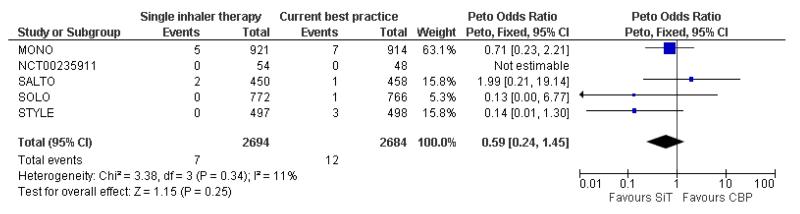

Exacerbations of asthma causing hospital admissions

There were 19 hospitalisations from a total of 5,378 participants in the five trials providing data for this review (seven in the single inhaler therapy arms and 12 in the current best practice arms of MONO; NCT00235911; SALTO; SOLO and STYLE). SALTO reports 2 asthma exacerbations that require hospitalisation in the single inhaler therapy arm of the study, so this could represent 1 or 2 patients. In either case there is no significant difference in the pooled outcome: (Peto OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.24 to 1.45) if this is two patients, (Peto OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.20 to 1.29) if the two events were in the same patient, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus Conventional Best Practice, outcome: 1.1 Patients with exacerbations causing hospitalisation.

Results from a further 4,600 patients in DE-SOLO; NCT00628758; SPAIN 2008 and SYMPHONIE 2008 are awaited.

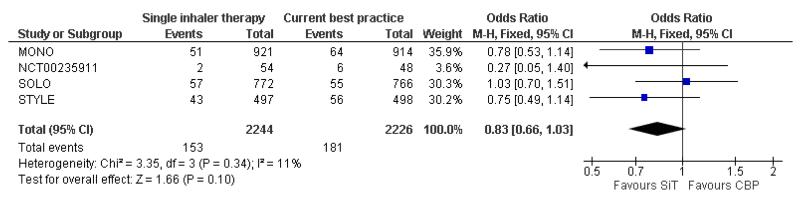

Exacerbations of asthma treated with oral corticosteroids

We have obtained data from four studies (MONO,NCT00235911, SOLO and STYLE, 4,470 participants) on patients with one or more courses of oral corticosteroids and the reduction with single inhaler therapy was not significant (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.03). There were 153 of 2244 in the SiT arm and 181 of 2226 in the current best practice arm who needed one or more courses of oral steroids, see Figure 3. No data has been made available from SALTO for this outcome, and again results are awaited from the four trials described above.

Figure 3. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus Conventional Best Practice, outcome: 1.2 Patients with exacerbations treated with oral steroids.

Serious adverse events

No significant difference was seen in either fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events from the combined results of MONO, SALTO and SOLO; for fatal events (Peto OR 1.95; 95% CI 0.39 to 9.67) Analysis 1.3, and for non-fatal events (OR 1.02; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.52) Analysis 1.4. However it should be pointed out that the overall number of events (6 fatal and 102 non-fatal SAEs) was too small to rule out the possibility of a clinically important increase or decrease. Results from the currently unpublished studies above may throw further light on these outcomes. Peto OR was used for the fatal SAE analysis in view of the presence of two trials with no deaths in the current best practice arms (MONO; SALTO).

A post-hoc observation was that each of these three studies found a higher number of discontinuations due to adverse events with single inhaler therapy, and these were significantly raised in MONO and SOLO, see Analysis 1.5. This finding requires further clarification from the currently unpublished studies, and was attributed by the investigators to patients in the SiT arm who changed from MDI to dry-powder inhaler devices.

Secondary Outcomes

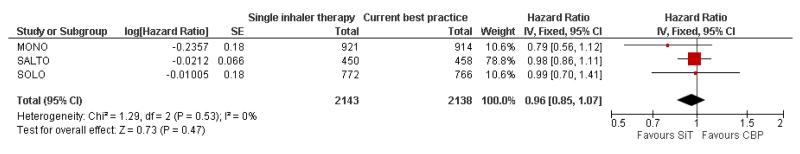

Severe exacerbations requiring medical intervention

There were 2143 patients on SiT compared with 2138 patients on current best practice in MONO, SALTO and SOLO. There was no overall significant reduction in the time to a serious exacerbation, as defined by the investigators, (Hazard Ratio 0.96; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.07), Figure 4.

Figure 4. Forest plot of comparison: 1 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus Conventional Best Practice, outcome: 1.6 Patients with “severe” exacerbation (time to event).

Change in morning Peak Expiratory Flow

The change in morning PEF (% predicted) in SOLO was 1.00% [95% CI −0.96 to 2.96] which was in favour of SiT, but neither clinically nor statistically significant ( Analysis 1.7). Data were not available for this outcome from MONO and SALTO.

Rescue Medication use

There was a difference of −0.16 [−0.27, −0.05] puffs per day of rescue medication use in the SiT arm of SOLO compared to current best practice, Analysis 1.8.

Quality of Life (Change in ACQ score)

The two studies reporting this outcome had heterogeneous findings (Analysis 1.9). SALTO demonstrated an improvement in the ACQ score in favour of SiT, whilst in SOLO the direction of effect favoured current best practice. The results have not been combined in view of the heterogeneity (I2 = 84%) and quality of life results are awaited from the other studies that have not yet been reported.

Steroid load

All three published studies demonstrated a significantly lower in-take of inhaled steroids in the SiT arms in comparison with current best practice but again heterogeneity was high (I2 = 91%) and the results were therefore not combined. It is expected that the size of the reduction in ICS dose will reflect the trial design for each study, giving rise to the heterogeneity, and in the mean differences ranged from 107 mcg/day in SALTO to 267 mcg/day in SOLO (Analysis 1.10).

Adults and Adolescents treated with Single inhaler Therapy compared to maintenance Inhaled Corticosteroids with separate reliever inhaler

Primary Outcomes

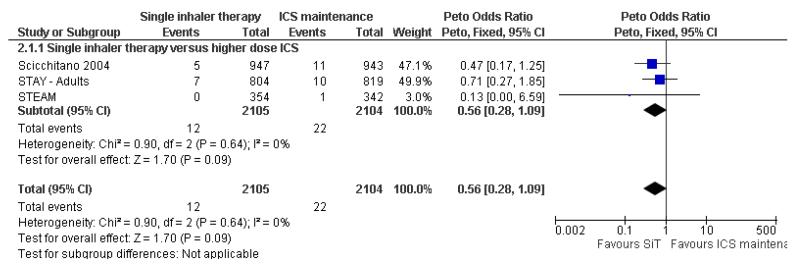

Exacerbations of asthma causing hospital admissions

Scicchitano 2004, STAY - Adults and STEAM contributed 4,209 participants to this outcome, and overall there were fewer admissions on SiT in comparison to ICS, but this was not statistically significant. The number of admitted patients was small (12 in total on SiT and 22 on ICS) and the pooled result is (Peto OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.09), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Forest plot of comparison: 2 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus higher fixed dose ICS, outcome: 2.1 Patients with exacerbations causing hospitalisation.

The data used for Scicchitano 2004, STEAM were on file from AstraZeneca, and were reported as patients with at least one asthma-aggravated serious adverse event that required hospitalisation. The composite outcome of hospitalisation or ED visits was dominated by participants attending ED and was therefore not used for this outcome. In total 17 patients were admitted to hospital in comparison to 38 seen in ED from these two studies. Peto OR was chosen for this meta-analysis as this method does not require a continuity correction for zero cells. Sensitivity analysis using Mantel-Haenszel OR gave very similar results (OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.11).

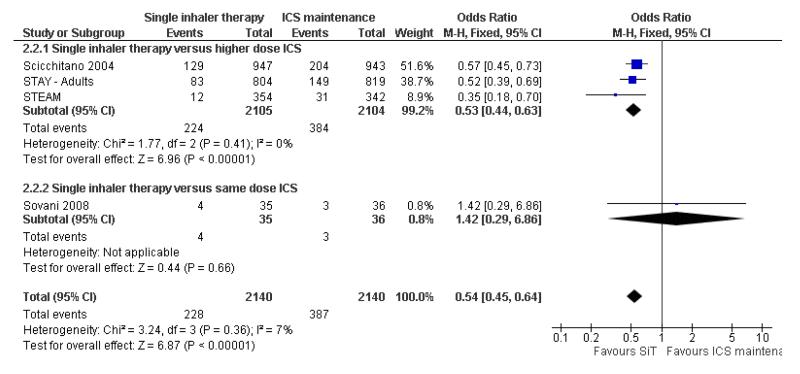

Exacerbations of asthma treated with oral corticosteroids

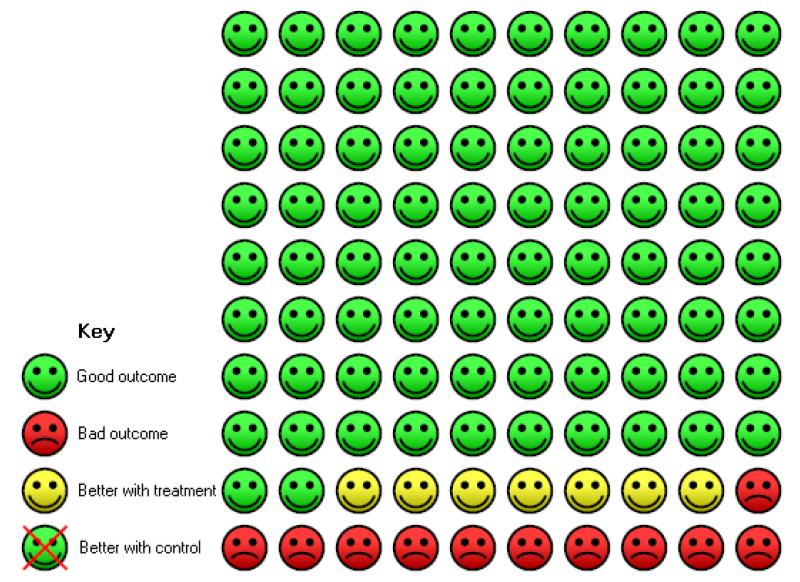

Scicchitano 2004, Sovani 2008, STAY - Adults and STEAM contribute data on this outcome from 4,280 participants; unpublished data on file from AstraZeneca has been obtained from Scicchitano 2004 and STAY - Adults. The STAY - Adults paper reported descriptive statistics only of courses of oral steroids per year, and in adults this was 0.19 on SiT and 0.38 on budesonide. The pooled result showed a significant reduction in the number of patients requiring a course of steroids (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.64) and with a total of 228 patients with an event on SiT and 387 on budesonide, Figure 6. This translates into a number needed to treat to prevent one patient needing oral corticosteroids over an eleven month period of 14 (95% CI 12 to 18), see Figure 7.

Figure 6. Forest plot of comparison: 2 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus higher fixed dose ICS, outcome: 2.2 Patients with exacerbations treated with oral steroids.

Figure 7. In the control group 18 people out of 100 had exacerbation treated with oral steroids over 11 months, compared to 11 (95% CI 9 to 12) out of 100 for the active treatment group. NNT(B) = 14, (95% CI 12 to 18).

Sensitivity analysis using random effects Mantel-Haenszel OR gave a marginally wider confidence interval (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.65). The design of Sovani 2008 was different from the other studies in that adherence with inhaled corticosteroids was the primary concern of the study.

Serious adverse events

No significant difference was seen in either fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events from the combined results of Scicchitano 2004,STAY - Adults and STEAM; for fatal events (Peto OR 0.37; 95% CI 0.05 to 2.62), and for non fatal events (OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.29). Again the number of events is small (4 fatal and 201 non-fatal) so the confidence interval includes the possibility of important increase or decrease with SiT.

In contrast to the studies comparing SiT to current best practice, a post hoc inspection of discontinuations due to adverse events in Scicchitano 2004 and STEAM found a significant decrease in favour of SiT.

Secondary Outcomes

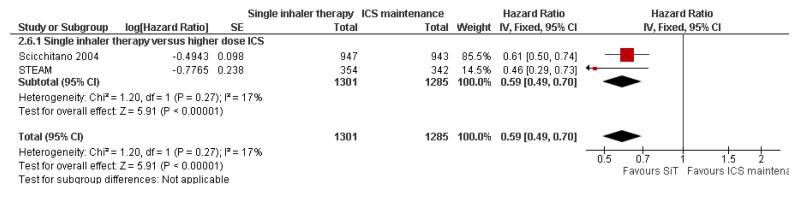

Severe exacerbations requiring medical intervention

There were 1301 on SiT compared with 1285 on twice the dose of budesonide in Scicchitano 2004 and STEAM. There was a significant reduction in the time to a serious exacerbation, as defined by the investigators, (Hazard Ratio 0.59; 95% CI 0.49 to 0.70), Figure 8.

Figure 8. Forest plot of comparison: 2 Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus higher fixed dose ICS, outcome: 2.6 Patients with “severe” exacerbation (time to event).

Change in morning Peak Expiratory Flow and clinic FEV1

There was a significant increase in PEF in the SiT arms ofScicchitano 2004, STAY - Adults and STEAM compared to higher doses of budesonide (MD 22.29 L/min; 95% CI 17.62 to 26.95), Analysis 2.7. Similarly an increase of FEV1 in favour of SiT was found (MD 0.10 L ; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.13), Analysis 2.8.

Rescue Medication use

There was a reduction in rescue medication use in favour of SiT (MD −0.37 puffs per day; 95% CI −0.49 to −0.25), Analysis 2.9.

Quality of Life (Change in ACQ score)

The only study reporting ACQ scores was Sovani 2008 and no significant difference was found, Analysis 2.10.

Steroid load

Scicchitano 2004 reported a mean daily budesonide dose of 466 mcg/day in the SiT arm in comparison with 640 mcg/day in the ICS arm, and 1776 days on oral corticosteroids in comparison with 3177 days. STAY - Adults does not report the mean daily doses of budesonide, but does report 0.19 courses of oral corticosteroids per year for SiT compared to 0.38 per year for higher dose budesonide. STEAM reports a mean daily budesonide dose of 240 mcg/day with SiT and 320 mcg/day in the higher dose ICS arm. However the paper also reports five patients on SiT who had a mean daily dose of > 640 mcg/day on SiT. Again STEAM reported a total of 114 days of oral corticosteroids with SiT and 498 days with higher dose budesonide.

Sovani 2008 was designed to investigate whether single inhaler therapy could overcome poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids, and found an increase in mean daily use of budesonide (448 versus 252 mcg/day, mean difference 196 mcg/day, 95% CI 113 to 279 mcg/day).

Children treated with Single inhaler Therapy compared to higher doses of Inhaled Corticosteroids

Primary Outcomes

Exacerbations of asthma causing hospital admissions

It has been possible to obtain clarification from the sponsors in relation to the hospitalisations for children in each treatment arm of STAY - Children. Hospitalisations related to asthma are reported as none on SiT and one with ICS (this does not quite match the asthma SAE data, as one child was already in hospital with laryngitis, and the stay was prolonged due to an asthma exacerbation) Analysis 3.1. These events are too few to draw any conclusions.

Exacerbations of asthma treated with oral corticosteroids

The only information in the report of STAY - Children in relation to oral corticosteroid use relates to the total number of treatment days in each group (32 days for SiT and 141 days for ICS). This is not suitable for use in meta-analysis as there is no report of how many children were treated with oral corticosteroids in each group. The sponsors have not been able to provide this data.

Serious Adverse Events

There were no fatal serious adverse events in STAY - Children and non-fatal events occurred in 2 out of 118 children on SiT compared to 5 out of 106 on ICS (a non-significant reduction) Analysis 3.3.

Annual Height gain

The mean increase in height over one year in the SiT group was 5.3 cm (range 1 to 14 cms) and in the ICS group the mean increase was 4.3 cm (range −2 to 15 cm). The fact that some children appear to have become shorter raises concerns about the accuracy of the measurements carried out in some of the 246 centres (as the paper reports that local procedures were used to measure height), but the average advantage of 1 cm for SiT was statistically significant (95% CI 0.3 to 1.7 cms) Analysis 3.4.

Secondary Outcomes

Severe exacerbations requiring medical intervention

There were nine patients on SiT with exacerbations requiring medical intervention (hospitalisation or ER visit or course of oral steroids) which was significantly less than the 21 patients given ICS, (OR from this single study 0.33 [0.15, 0.77]).

Change in morning Peak Expiratory Flow

The children given SiT therapy in STAY - Children had an average increase in morning PEF of 12 Litres/min [95% CI: 4.55 to 19.45] in comparison with those given ICS.

Clinic Spirometry (FEV1)

There was no significant difference in FEV1 between the SiT and ICS groups in STAY - Children (0.10 Litres [95% CI: −0.14, 0.34]).

Nocturnal Awakenings

There were, on average, two less nocturnal awakenings per night for children on SiT than those on ICS in STAY - Children (−2.00 [−3.33, −0.67]).

Steroid load

The mean daily dose of budesonide in children given SiT in STAY - Children was 126 mcg/day in comparison to 320 mcg/day in the group randomised to fixed dose budesonide. There were also less days spent on oral corticosteroids in the SiT group (32 v 141 days). Two of 51 children given SiT had abnormally low cortisol levels in comparison with three of 41 on ICS, a non significant reduction (OR = 0.52 [0.08, 3.25]).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

In comparison to common best practice, which allowed the use of long-acting beta2-agonists in the control arms, four large studies (MONO; SALTO, SOLO and STYLE) on 5,378 patients have not demonstrated significant advantages for SiT in exacerbations needing medical intervention. There was no significant difference found in fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events. All three published studies found a reduction in ICS dose when using SiT. The full results from further studies, which aimed to recruit a further 5600 patients, are awaited (DE-SOLO; STYLE; SPAIN 2008; SYMPHONIE 2008; NCT00628758).

In contrast, in comparison to higher maintenance doses of budesonide (with no long-acting beta2-agonists in the control arms), four studies (Scicchitano 2004, STAY - Adults, STEAM and Sovani 2008) on 4,280 patients demonstrated significant reductions in patients with an exacerbation needing oral steroids (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.64) but not on exacerbations leading to hospitalisation (Peto OR 0.56; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.09). There was no significant difference found in fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events. The studies found a reduction in ICS dose when using SiT. Sovani 2008 demonstrated increased adherence with inhaled corticosteroids using single inhaler therapy in comparison to maintenance budesonide at the same dose.

Only one study included 224 children (STAY - Children) and compared SiT to four times the dose of regular budesonide. There was a significant reduction in exacerbations needing increase in inhaled steroid treatment and/or additional treatment in this study, but only two hospitalised patients and no separate data on courses of oral corticosteroids. There was no significant difference found in fatal or non-fatal serious adverse events. Less inhaled and oral corticosteroids were used in the SiT group and the annual height gain was also greater in the SiT group.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All the included studies have been sponsored by AstraZeneca, and large numbers of patients that have been studied or are in ongoing trials are still unreported. For this reason we would regard the current evidence as provisional until further data becomes available. This is especially relevant to trials comparing SiT with current best practice, and the results in children, in whom the use of long-acting beta2-agonists is more contentious (Bisgaard 2003).

It is possible that the difference between the results in trials comparing SiT with current best practice as opposed to higher doses of ICS alone as a comparison arm could relate to the design of the trials. Many of the patients in the control arm of the current best practice trials were probably taking long-acting beta2-agonists (as previous long-acting beta2-agonists was around 75% in MONO and SOLO), whereas none of the control arm patients in the higher dose maintenance ICS were taking long-acting beta2-agonists (as they were withdrawn from those patients previously using them).

The inclusion of patients who were symptomatic during run-in periods in which LABA was withdrawn may favour SiT, as formoterol would be expected to control symptoms more quickly than inhaled corticosteroids in Scicchitano 2004, STEAM and STAY - All ages. There is some suggestion that this may have occurred from the plots of individual patient exacerbations that show steeper gradients initially for the budesonide arms of these trials but similar gradients in the two groups towards the end of the study period.

This implies that the current evidence comparing SiTto fixed doses of ICS can be applied directly only to patients who become symptomatic when maintenance treatment with ICS (with or without LABA) is reduced. How these results should be extrapolated to other groups of patients remains a matter for debate.

Quality of the evidence

Despite sparse information on sequence generation and allocation concealment, we concluded that as all the studies were regulatory studies, the risk of bias in these domains is low. The studies comparing SiT with current best practice were not blinded, whilst those that compared SiT to fixed doses of ICS were blinded. Although bias could have been introduced in the former, the treatment effects in comparison with current best practice are generally smaller.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We agree with the reservations voiced by Lipworth 2008 in his response in the BMJ to the review by Barnes 2007. The run-in for the trials comparing SiT with fixed dose inhaled corticosteroids was designed to select patients who became symptomatic when their maintenance treatment was reduced or when long-acting beta2- agonists were withdrawn. This feature of the trial design may contribute to the improvement in time to first asthma exacerbation on SiT, because the onset of action of higher dose inhaled corticosteroids would be expected to be slower, and more patients may therefore have suffered an early exacerbation in the higher dose inhaled corticosteroid arm of the trials.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Single inhaler therapy can reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations needing oral corticosteroids in comparison with fixed dose maintenance inhaled corticosteroids. Guidelines and common best practice suggest the addition of regular long-acting beta2-agonist to inhaled corticosteroids for uncontrolled asthma, and single inhaler therapy has not been demonstrated to significantly reduce exacerbations in comparison with current best practice, although results of five large trials are awaiting publication. Single inhaler therapy is not currently licensed for children under 18 years of age in the United Kingdom.

Implications for research

The majority of trials comparing single inhaler therapy to current best practice have not been fully published, and we have chosen not to suggest implications for further research on adults until these results are known. There is very little current evidence with respect to children.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | A Comparison of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy (Symbicort Turbuhaler 160/4.5 μg, 1 Inhalation b.i.d. Plus as Needed) and Conventional Best Practice for the Treatment of Persistent Asthma in Adults - a 26-Week, Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Multicentre Study. Dec 2004 to October 2006. 169 centres in Germany. No report of run-in The purpose of this study is to determine whether Symbicort dosed according to the Symbicort Maintenance and Reliever Therapy (SMART) concept is superior to standard asthma treatment according to the local German treatment guidelines |

|

| Participants | Estimated enrolment: 1600. Patients 18 years or older Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

|

| Interventions |

|

|

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Not specified |

|

| Notes | No published results found for this study in September 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear No | details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | No details |

| Methods | This was a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, Multicentre study in 1900 patients (planned number) with persistent asthma. Patients were treated with either Symbicort® SMART (i.e. Symbicort®Turbuhaler® (budesonide/formoterol) 160/4.5 μg (delivered dose), 1 inhalation b.i.d. plus as needed), or conventional best practice according to the investigator’s judgement, following GINA guidelines (Ref: Global Initiative for Asthma 2002). The treatment period lasted for 26 weeks, with no mention of any run-in period This study was conducted in Denmark (123 centres), Finland (69 centres) and Norway (83 centres) between September 2004 and October 2006 | |

| Participants | 1854 patients were randomised, 1835 took at least one treatment and contributed to the analysis, and 1667 completed the study. 75% were taking LABA and daily ICS dose was 1035 mcg/day (BDP equivalence). Male and female patients, > 12 years of age, with persistent asthma who were currently treated with inhaled glucocorticosteroids (IGCSs) and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) |

|

| Interventions |

Investigational product was Symbicort® Turbuhaler®, 160/4.5 μg/dose budesonide/formoterol (delivered dose), 1 inhalation b.i.d. as maintenance treatment plus as needed, in response to symptoms Comparator products were any conventional best practice treatments, except Symbicort ® SMART and/or maintenance with oral glucocorticosteroids prescribed at the discretion of the investigator according to GINA treatment guidelines Ref: Global Initiative for Asthma 2002) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary variable

Only information regarding SAEs and discontinuations due to AE (DAEs) were collected in this study Definition of severe exacerbation Not specified Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicated 51/64 patients with at least one course of oral steroids and 5/7 with at least one hospitalisation on single inhaler therapy/current best practice (921/914) |

|

| Notes | One (1) death was reported in the study in the single inhaler therapy group in Denmark. The patient contacted the investigator 16 August due to asthma deterioration. The patient discontinued the study and study medication on 9 September 2005 due to “Subject not willing to continue study” and experienced asthma exacerbation on 30 September 2005.The event was considered serious due to hospitalization, and the patient died the same day. The events pneumonia and in compensatio cordis lead to death and not the event of asthma exacerbation. The investigator considered the event to be unrelated to the study therapy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open study |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | 90%of randomised patients completed the study and analyses was ITT |

| Methods | Treatment, Randomized, Open Label, Active Control, Parallel Assignment, Efficacy Study. August 2003 start Effects of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy on Bronchial Hyper Responsiveness, Asthma Control and Safety in Mild to Moderate Asthmatics in General Practice, Compared to Usual Care Therapy. The primary objective is to compare the effects of Symbicort SiT and treatment according to NHG-guidelines on bronchial hyper responsiveness in asthmatic patients, as measured by PD20 histamine, and to validate the Bronchial Hyper responsiveness Questionnaire (BHQ). Two research centres in the Netherlands |

|

| Participants | Enrolment planned: 100 Inclusion Criteria:

|

|

Exclusion Criteria:

|

||

| Interventions |

|

|

| Outcomes |

Primary Outcome Measures:

Not specified Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicate that no patients were hospitalised, and 2/54 compared to 6/48 patients had at least one course of oral steroids on SMART and current best practice respectively |

|

| Notes | Study BN-00S-0011 is reported on the clinical trials register as completed, but no study report summary had been posted by AstraZeneca on the trials web site (www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com/ncmprintchapter.aspx?type=article¶m=528362) by September 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | No details |

| Methods | This was a randomised, open-label, phase IIIB, multicenter study with a parallel group design. Patients were treated with either SMART i.e. Symbicort® Turbohaler® 160/ 4.5μg/inhalation (delivered dose), 1 inhalation b.i.d. plus as needed (in response to symptoms), or conventional best practice. The study consisted of the following periods: 2-week run-in period followed by a 26-week randomised treatment period. Usual therapy used in run-in period A total of 194 centres in Belgium and Luxembourg participated in this study, between December 2004 and June 2006 |

|

| Participants |

Population: 908 adults and adolescents were randomised. All were analysed for efficacy and safety and 867 completed the study. 38% classified as moderate persistent asthma, 36% severe persistent asthma and 27% mild persistent asthma. Mean ICS daily dose during run-in 579 mcg/day (range 100 to 2000). Inclusion criteria: Male and female, adolescent (≥ 12 years of age) and adult patients with persistent asthma, currently treated with inhaled glucocorticosteroid (IGCS) or IGCS and long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) |

|

| Interventions | 1. Investigation medication was Symbicort® Turbohaler® 160/4.5μg/inhalation (delivered dose), 1 inhalation b.i.d. + as needed in response to symptoms. 2. Comparators were conventional best practice, active stepwise individualized treatment according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) treatment guidelines. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary variable

Not specified |

|

| Notes | Twenty patients reported a total of 20 serious adverse events during treatment (9 in the SMART group and 11 in the current best practice group). Six patients discontinued treatment due to an SAE/AE [4 in the SMART group (including two patients who died: one suicide and one myocardial infarction with no relation with the treatment) and 2 in the current best practice group] | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | No details |

| Methods | This was a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, active-controlled, parallel-group, Multicentre study comparing the efficacy and safety of Symbicort 160/4.5 μg/inhalation, two inhalations once daily + Symbicort 160/4.5 μg/inhalation as-needed (Symbicort single-inhaler therapy (SiT)) with Pulmicort 160 μg/inhalation, two inhalations bid + Bricanyl 0.4 mg/inhalation as-needed, in adults and adolescents (12-80 years) for a period of 12 months in the treatment of asthma.(Carried out between May 2001 and January 2003). The run-in period was on usual ICS dose but LABA was withdrawn This was a Multicentre study with 211 centres participating from the following 18 countries: Argentina (6 centres), Australia (10 centres), Canada (22 centres), Czech republic (5 centres), Finland (6 centres), France (29 centres), Germany (20 centres) , Hungary (7 centres), Israel (17 centres), Italy (11 centres), Mexico (5 centres), the Netherlands (24 centres), New Zealand (4 centres), Norway (13 centres), Portugal (7 centres), Russia (6 centres), South Africa (11 centres) and Turkey (8 centres) | |

| Participants |

Population: Mean age: 43 years. FEV1 70% predicted. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 746mcg/day. Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown%. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: unknown%. Previous clinically important exacerbation required for eligibility. 45% of enrolled patients were already on LABA as well as ICS Inclusion criteria: Male and female subjects, 12 to 80 years with asthma, previously treated with inhaled glucocorticosteroids (IGCS) 400-1600 μg per day, with a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1 ) of 50-90% of predicted normal (% P.N. ), a history of at least one clinical important asthma exacerbation 1-12 months prior to inclusion, a reversibility in FEV1 from baseline of at least 12%, and who had an asthma symptom score ≥ 1 during 4 of the last 7 days of the run-in period (in which usual dose of ICS was used but LABA was withdrawn from the 45% taking LABA previously) |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide/formoterol 200/6 mcg two inhalation in the evening [400 mcg budesonide/day], with additional doses as needed as reliever (3 turbuhalers formorning, evening and relief ) 2. Budesonide 200 mcg two inhalations twice daily [800 mcg budesonide/day], with terbutaline reliever (3 turbuhalers as above with placebo in the morning) Maximum of 10 as needed inhalations could be used per day before contacting the investigator *200/6 mcg actuator dose is described as 160/4.5 mcg delivered dose in the paper |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary efficacy variable

N.B. As-needed-free days and symptom-free days were added as variables to the statistical analyses to conform with previous Symbicort studies. It was done after finalisation of the study protocol, but before un blinding of study data Safety Safety assessments including physical examination, adverse events (AEs), pulse and blood pressure, were obtained in all subjects Definition of severe exacerbation Included PEF less than 70% baseline on two consecutive days, severe exacerbations requiring medical intervention were also reported (hospitalisation, ED visit or course of oral steroids), but all severe exacerbations were to be treated with a 10 day course of oral prednisolone Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicated the number patients given at least one course of oral steroids was 129/947 on SMART and 204/943 on Pulmicort. For Hospitalisation/ER treatment there were 12/947 and 20/947 respectively. Asthma SAE was 5/947 and 11/943 which have been used as the hospital admission outcomes for this study |

|

| Notes | There were three deaths reported in the study, two in the Pulmicort group and one in the Symbicort SiT group. None of the deaths were related to asthma or, as judged by the investigator causally related to investigational product. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | 1573/1890 completed (83%) |

| Methods | Randomised, open, parallel group study over a 6 month period. In the two week run-in patients used current asthma treatment (pre-study ICS +/− LABA). Unknown number of centres in Canada | |

| Participants |

Population: 1538 asthmatic adults aged 12 years and over with asthma on at least 400 mcg/day ICS and symptomatic unless also on LABA (74% of those randomised were on LABA and ICS) Inclusion Criteria: Aged 12 years or more and asthma diagnosis for aminimum of three months. Previous treatment with ICS for at least 3 months (at least 400mcg/day) with at least 3 inhalations of relief medication in the last 7 days of run in, or concurrent use of LABA. Patients with a smoking history of over 10 pack-years or exacerbation requiring a change in asthma treatment in the past 14 days were not included; nor were patients already using Single inhaler Therapy Baseline Characteristics: Mean age: 40 years. FEV1 not measured but PEF 94% predicted. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 569 mcg/day, and 74% were also using LABA. Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: unknown |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide/formoterol 200/6mcg one inhalation twice daily [400mcg budesonide/day], as maintenance and reliever 2. Current best practice. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Hospitalisation, or emergency room visit or course of oral corticosteroids for at least 3 days due to asthma |

|

| Notes | Study D5890L00004 is reported on the clinical trials register as completed in September 2005, but no study report summary had been posted by AstraZeneca on the trials web site (http://www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com/article/514143.aspx) by September 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | 1400/1538 (91%) completed the study |

| Methods | Randomised, open, parallel group study over a 6 month period | |

| Participants |

Population: 71 asthmatic adults aged 18-70 years with asthma on at least 400-1000 mcg/day ICS who demonstrated poor compliance and were poorly controlled. Inclusion Criteria: Aged 18-70 years. Previous treatment with ICS (400-1000 mcg/day beclometasone equivalent) who demonstrated poor compliance by collecting less than 70% of expected ICS prescriptions in the previous year. Poor control demonstrated by at least two prescriptions of prednisolone or 10 canisters of reliever inhaler in previous year. At least four puffs of reliever for at least 4 days per week over past 4 weeks. Patients with a smoking history of over 20 pack-years or exacerbation requiring oral steroids in the past 4 weeks were not included Baseline characteristics: Mean age: 36 years. FEV1 85% predicted. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 590 mcg/day, but only 278 mcg/day was being taken! Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: mean of one course per year (SD 1) |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide/formoterol 200/6 mcg one inhalation twice daily [400 mcg budesonide/day], as maintenance and reliever. 2. Budesonide 200 mcg [400 mcg budesonide/day], one inhalation twice daily via Turbohaler and usual reliever |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

|

|

| Notes | Supported by an unconditional grant from AstraZeneca | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | computer-generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | An independent pharmacist used computer-generated random numbers to randomise each participant to one of two groups |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | 55/71 (77%) completed the study and there were more withdrawals in the control arm: 13 compared to 3 in active arm (all 3 reported difficulty using the inhaler) |

| Methods | Study Design: Randomised, double-blind, parallel group study over a 12 month period in 246 centres in 22 countries (between Jan 2001 and Jan 2003). In the 14-18 day run-in patients used pre-study ICS with terbutaline for symptom relief (LABA had to be discontinued at least 3 days before run-in) | |

| Participants |

Adult Population: 2419 asthmatic adults aged 12 years or more with asthma uncontrolled on ICS (400-1000 mcg/day) and a history of at least one “clinically important” exacerbation in the past year. The maintenance ICS dose was cut to a quarter with additional Formoterol (SiT) or maintenance with Terbutaline for relief Adults Mean age: 40 years. FEV1 73% predicted pre bronchodilator. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 660 mcg/day. Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown proportion. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: unknown proportion Inclusion Criteria: Aged 12-80 years, with a constant dose of ICS (400-1000 mcg/day) at least 3 months. Prebronchodilator FEV1 of 60-90% predicted normal value and at least 12% reversibility following Terbutaline. To be included patients had to need at least 12 rescue inhalations in the last 10 days of run-in. Adults using ten or more rescue inhalations in a single day or with an exacerbation during run-in were not randomised |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide/formoterol 100/6 mcg twice daily [200 mcg budesonide/day] and as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) 2. Budesonide/formoterol 100/6 mcg twice daily [200 mcg budesonide/day] and Terbutaline as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) 3. Budesonide 400 mcg twice daily [800 mcg budesonide/day] and Terbutaline as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) Maximum of 10 as needed inhalations could be used per day before contacting the investigator |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome

Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicate that 7/804 adults and adolescents had at least one asthma related SAE on SMART and 10/819 on Pulmicort. Similarly 83/804 on SMART and 149/819 on Pulmicort had at least one course of oral corticosteroids |

|

| Notes | SAE data (44,46,42) in the adult population; deaths given for whole trial (0,2,1) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | Computer generated randomisation scheme |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | Eligible patients were randomised in balanced blocks by allocating patient numbers in consecutive order |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Double blind. All study medication was given by turbuhalers. Maintenance and as needed medication distinguished by the colour of the label and its wording |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | Withdrawals and Dropouts: 2039/2419 (84%) completed the study |

| Methods | see STAY - Adults & STAY - Children | |

| Participants | Combined data on Children and Adults aged 4 to 60 years with a history of one or more exacerbations in the past year | |

| Interventions | see STAY - Adults & STAY - Children | |

| Outcomes | see STAY - Adults & STAY - Children | |

| Notes | Data presented for adults and children. P values based on ANOVA and changes from baseline calculated from Tables 1 & 2 in the primary publication. Standard Errors estimated from P values | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | See STAY - Adults |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Methods | Study Design: Randomised, double-blind, parallel group study over a 12 month period in 41 centres in 12 countries (between Jan 2001 and Jan 2003). In the 14-18 day runin patients used pre-study ICS with terbutaline for symptom relief (LABA had to be discontinued at least 3 days before run-in) | |

| Participants |

Children in Study: 341 asthmatic children aged 4-11 years with asthma uncontrolled on ICS (200-500 mcg/day) and a history of at least one “clinically important” exacerbation in the past year. Mean age: 8 years. Mean morning PEF: 220 L/min. FEV1 76% predicted pre bronchodilator. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 315 mcg/day. Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown proportion. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: unknown proportion Inclusion Criteria: Aged 4-11 years, with a constant dose of ICS (200-500 mcg/day) at least 3 months. Prebronchodilator FEV1 of 60-100% predicted normal value and at least 12% reversibility following Terbutaline. To be included patients had to need at least 8 rescue inhalations in the last 10 days of run-in. Children using seven or more rescue inhalations in a single day or with an exacerbation during run-in were not randomised |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide 100 mcg (80 mcg delivered dose) and Formoterol 4.5 mcg in the evening and as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) 2. Budesonide 100 mcg (80 mcg delivered dose) and Formoterol 4.5 mcg in the evening and Terbutaline as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) 3. Budesonide 400 mcg (320 mcg delivered dose) in the evening and Terbutaline as needed (one maintenance and one relief Turbuhaler) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome

Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicate that 0/118 children under the age of 12 years had at least one asthma related SAE on SMART and 2/106 on Pulmicort. Data on children given a course of oral corticosteroids has not been obtained |

|

| Notes | Adverse Events:SAE data given (2,16,5) of these (0,7,2) were related to asthma. Change from baseline nights with awakenings were the same in both groups, P value in the paper not used as it related to post treatment levels not changes. No SD data published in the paper with respect to growth comparing budesonide/formoterol to Terbutaline as reliever, so SD calculated from the other comparisons presented | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | See STAY - Adults |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | See STAY - Adults |

| Methods | The study was double-blind, randomised, active-controlled, multi-centre and multinational with a parallel group design comparing the efficacy and safety of Symbicort 80/4.5 μg/inhalation, 2 inhalations once daily plus Symbicort 80/4.5 μg/inhalation asneeded (Symbicort single-inhaler therapy, SiT)with that of Pulmicort 160 μg/inhalation, 2 inhalations once daily plus Bricanyl 0.4 mg/dose as-needed when given to adults and adolescents (12-80 years) for a period of 6 months in the treatment of asthma This was a Multicentre study with 77 centres participating from the following countries: Argentina (5 centres), Brazil (7 centres), China (4 centres), Denmark (15 centres), Indonesia (6 centres), Norway (10 centres), The Philippines (10 centres), Spain (9 centres), and Sweden (11 centres) |

|

| Participants |

Population: Male and female subjects, 12 to 80 years with asthma, previously treated with 200-500 μg per day of inhaled glucocorticosteroids (IGCS). They had to have a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1 ) of 60-100% of predicted normal at Visit 1 and a reversibility in FEV1 from baseline of at least 12% at Visit 1 or 2, or a peak expiratory flow (PEF) variability of at least 12%on at least 3 out of the last 10 days of the run-in. During the last 10 days of the run-in period the subjects also had to have used at least 7 inhalations of the as-needed medication. Run-in was on Budesonide 100mcg bd with Terbutaline prn (this represents around half the previous dose of ICS and LABA was withdrawn from the 20% participants who were taking LABA previously) Baseline Characteristics: Mean age: 38 years. FEV1 75% predicted. Mean ICS dose at enrolment 348 mcg/day and 20% were also on LABA. Hospital admission for asthma in the past year: unknown. Course of oral steroids for asthma in past year: unknown. Previous exacerbation not required for eligibility. |

|

| Interventions | 1. Budesonide/formoterol 100/6 mcg two inhalation in the evening [200 mcg budesonide/day], with additional doses as needed as reliever 2. Budesonide 200 mcg two inhalations once daily [400 mcg budesonide/day], with terbutaline reliever *200 mcg actuator dose is described as 160 mcg delivered dose in the paper |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicate 12/354 patients with at least one course of oral steroids on SMART and 31/342 on Pulmicort. For asthma-aggravated SAE the figures were 0/1 and for hospitalisation or ER visits 1/9 (which suggests that most of these were ER visits as hospitalisation for asthma is a mandatory category for asthma SAE) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

Yes | Double blind |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Yes | 639/697 (92%) completed the study |

| Methods | A Comparison of the Efficacy of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy (Symbicort Turbuhaler ® 160/4.5 mcg 1 Inhalation b.i.d. Plus as-Needed) and Conventional Best Practice for the Treatment of Persistent Asthma in Adolescents and Adults - a 26 Weeks, Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Multicentre Study. July 2005 to December 2006 53 study locations in Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, Greece, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia |

|

| Participants | Age at least 12 years. Aim to enrol 1000 participants. Inclusion Criteria: - - Diagnosis of asthma at least 3 months - Prescribed daily use of glucocorticosteroids at a dose > 320 mcg/ day for at least 3 months prior to Visit 1 Exclusion Criteria: - Smoking history > 10 pack-years - Asthma exacerbation requiring change in asthma treatment during the last 14 days prior to inclusion - Any significant disease or disorder that may jeopardize the safety of the patient |

|

| Interventions | The purpose of the study is to compare the efficacy of a flexible dose of Symbicort with conventional stepwise treatment according to asthma treatment guidelines in patients with persistent asthma

|

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Definition of severe exacerbation Not specified Additional Data Data on file from AstraZeneca indicates no patients with admission for asthma and 43 with at least one course of oral steroids (N=497) on SMART and 3/498 and 56/498 respectively on current best practice |

|

| Notes | This study was completed in December 2006 but no results have yet been published in medical journals or on the AstraZeneca web site | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | No details |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No details |

| Blinding? All outcomes |

No | Open |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes |

Unclear | No details |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Balanzat 2004 | Overview of three existing trials |

| Bousquet 2007 | Budesonide/formoterol for maintenance and relief in uncontrolled asthma vs. high-dose salmeterol/fluticasone |

| COMPASS | Different doses of Symbicort used for maintenance |

| COSMOS | Comparison with maintenance on Fluticasone/Salmeterol |

| D5890C00003 | SiT compared to higher dose maintenance regimen on BDF and Budesonide |

| Ind 2002 | Formoterol v Terbutaline as reliever |

| Jenkins 2007 | budesonide/formoterol dose adjustment with FeNO (not used as reliever) |

| Jonkers 2006 | Single dose study |

| Loukides 2005 | SiT compared to separate inhalers for maintenance treatment and Formoterol relief |

| Lundborg 2006 | Higher dose combination maintenance therapy but no ICS maintenance arm |

| Richter 2007 | Formoterol not combination therapy as reliever |

| SMILE | No comparison with maintenance ICS arm |

| SOMA | No maintenance ICS arm |

| Tattersfield 2001 | Formoterol v Terbutaline as reliever |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

| Trial name or title | NCT00463866 |

|---|---|

| Methods | The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of two different maintenance doses of Symbicort SMART (Symbicort Maintenance And Reliever Therapy) in adult asthmatic patients. A 6 month treatment period. Estimated enrolment 8000 |

| Participants | Inclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | Two different doses of SMART therapy - unclear if there is a placebo arm |

| Outcomes | Not described |

| Starting date | March 2007 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | NCT00628758 |

|---|---|

| Methods | The primary objective is to compare the efficacy of Symbicort Single inhaler Therapy with treatment according to conventional best practice in adult patients with persistent asthma. Treatment, Randomized, Open Label, Active Control, Parallel Assignment, Efficacy Study. Estimated enrolment 1000 |

| Participants | No details |

| Interventions | A Comparison of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy (SymbicortTurbuhaler 160/4.5mcg, 1 Inhalation b.i.d. Plus as Needed) and Conventional Best Practice for the Treatment of Persistent Asthma in Adults a -26-Week, Randomized, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Multicentre Study |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures: Time to first severe asthma exacerbation. Defined deterioration in asthma leading to at least one of the following:1.Hospitalisation/Emergency room (or equivalent) treatment due to asthma 2.Oral GC treatment due to asthma for at least 3 days Secondary Outcome Measures: Number of severe asthma exacerbations Change in AQLQ(S) score from randomisation (visit 1) to Visits 4 Mean use of as-needed medication per day during treatment period Prescribed asthma medication during the treatment period |

| Starting date | March 2006 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | Study SPAIN A Comparison of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy (Symbicort Turbuhaler 160/4.5 mcg, 1 Inhalation b.i. d. Plus as Needed) and Conventional Best Practice for the Treatment of Persistent Asthma in Adults - a 26-Week, Randomised, Open-Label, Parallel-Group, Multicentre Study. Estimated enrolment: 1000 |

| Methods | Treatment, Randomized, Open Label, Active Control, Parallel Assignment, Efficacy Study |

| Participants | Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | A Comparison of Symbicort Single Inhaler Therapy (Symbicort Turbuhaler 160/4.5 meg, 1 Inhalation b.i.d. Plus as Needed) and Conventional Best Practice |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome variable will be time to first severe asthma exacerbations. Exacerbations are considered an appropriate outcome variable by CPMP The definition of a severe asthma exacerbation is based on the same guideline A secondary objective is to collect safety data for treatment in the two treatment groups in adult patients with persistent asthma |

| Starting date | Sept 2006 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

| Trial name or title | SYMPHONIE |

|---|---|

| Methods | A Comparison of Symbicort Single Inhaler and Conventional Best Practice for the Treatment of Persistent Asthma in Adolescents and Adults. A 26-Week, Randomised, Open, Parallel Group Multicentre Study. Estimated enrolment: 1000 |

| Participants | Inclusion Criteria:

Exclusion Criteria:

|

| Interventions | A flexible dose of Symbicort compared with conventional stepwise treatment according to asthma treatment guidelines in patients with persistent asthma |

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome Measures: Time to first severe asthma exacerbation Secondary Outcome Measures: Number of asthma exacerbations, Mean use of as-needed medication, Prescribed asthma medication, Asthma Control Questionnaire, Satisfaction with Asthma Treatment Questionnaire, Safety: Serious Adverse Events and discontinuations due to adverse events |

| Starting date | Sept 2005 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

DATA AND ANALYSES

Comparison 1.

Adults and Adolescents treated with Single Inhaler Therapy versus Current Best Practice

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Patients with exacerbations causing hospitalisation | 5 | 5378 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.24, 1.45] |

| 2 Patients with exacerbations treated with oral steroids | 4 | 4470 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.66, 1.03] |

| 3 Serious Adverse Events (fatal) | 3 | 4281 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.95 [0.39, 9.67] |

| 4 Serious Adverse Events (non-fatal) | 3 | 4281 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.68, 1.52] |

| 5 Discontinuation due to Adverse Events | 3 | 4281 | Odds Ratio (M-H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.92 [1.70, 5.01] |

| 6 Patients with “severe” exacerbation (time to event) | 3 | 4281 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.85, 1.07] |

| 7 Change in PEF (% predicted) | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8 Rescue Medication Use (puffs per day) | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |