Abstract

Primary uterine sarcomas are infrequent neoplasms and most commonly leiomyosarcomas or endometrial stromal sarcomas. We report a rare case of primary uterine osteosarcoma discovered in a woman in her 60s following staging CT imaging for bilateral breast carcinomas. Examination of the subsequent hysterectomy specimen showed a tumour composed of malignant spindle cells and osteoclast-like giant cells associated with osteoid and neoplastic bone, in keeping with primary uterine osteosarcoma. Distinction of osteosarcoma from the more common carcinosarcoma is important due to the worse prognosis impacting on treatment decisions. In addition, synchronous presentation of this unusual tumour with bilateral breast carcinomas raises the possibility of a mutual genetic pathogenesis.

Background

Primary uterine sarcomas are infrequent neoplasms and most commonly leiomyosarcomas or endometrial stromal sarcomas.1 We report a rare case of primary uterine osteoblastic variant of osteosarcoma, diagnosed in a woman who initially presented with bilateral breast carcinomas.

Case presentation

A woman in her 60s was found to have screen detected invasive lobular breast carcinoma of the right breast and invasive ductal carcinoma, no special type, of the left breast. Staging CT imaging prior to mastectomy showed a 12 cm pelvic mass which on initial impression was thought to be a fibroid uterus. Associated postmenopausal bleeding led to pelvic ultrasound, hysteroscopy and biopsy. The biopsy showed undifferentiated sarcoma, unclassifiable with immunohistochemistry. Following discussion at a multidisciplinary team meeting it was felt that the uterine tumour was a separate primary malignancy rather than metastasis from the breast. Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed for both treatment purposes and to fully categorise the malignancy to guide further adjuvant therapy.

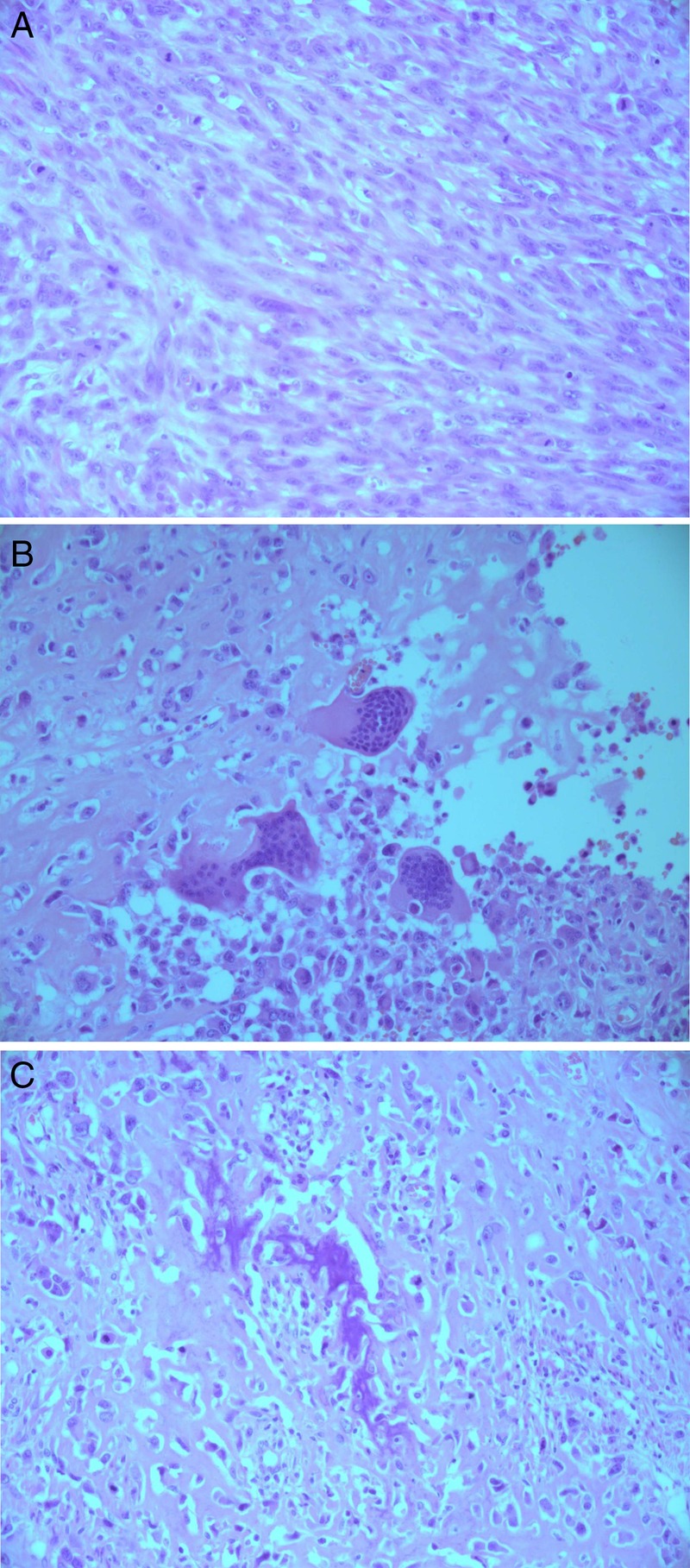

Histological examination of the resection specimen showed a partially necrotic tumour with a discrete outline located within and extending throughout the myometrium. The tumour was composed of malignant spindle cells (figure 1A), with an intermittent component of pleomorphic cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Plentiful osteoclast-like giant cells were present (figure 1B). Mitoses were numerous and structurally abnormal forms were common. Neoplastic cells were surrounded by hyaline osteoid matrix and foci of coarse neoplastic woven bone (figure 1C). Generous sampling of the tumour showed no admixed neoplastic epithelial elements, thus ruling out the more common carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Müllerian tumour).

Figure 1.

(A) Malignant spindle cells (H&E stain, original magnification ×20). (B) Osteoclast-type giant cells (H&E stain, original magnification ×20). (C) Neoplastic woven bone (H&E stain; original magnification ×20).

Tumour cells showed immunohistochemical expression for vimentin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin (focally) and CD99. Epithelial markers were not expressed. The morphological and immunohistochemical appearances were in keeping with primary uterine osteoblastic variant of osteosarcoma.

Unfortunately, despite treatment, further CT imaging showed the development of multiple peritoneal and pulmonary deposits, confirmed on biopsy to be metastatic osteosarcoma. The patient received palliative chemotherapy and died several months later.

Discussion

The majority of pure mesenchymal uterine tumours are leiomyomas or endometrial stromal tumours. Uterine sarcomas are infrequent, accounting for 1–2% of all uterine neoplasms.1 2 Pure homologous osteosarcomas are exceptionally rare, with only a handful of cases reported in the literature.3 In the reported cases patients presented in the fifth to sixth decades of life with non-specific gynaecological symptoms of lower abdominal pain, postmenopausal bleeding or presence of a mass. Ultrasound and CT imaging findings were generally non-specific.4 Treatment included hysterectomy with adjuvant chemotherapy. Prognosis was poor with high rates of metastasis and a mean survival time of 11 months.3 4

One postulated pathogenetic theory relates to multipotential cells residing in the myometrium, capable of differentiating into myocytes, endometrial stromal cells and other elements. These cells may subsequently undergo malignant transformation leading to uterine osteosarcoma. Alternative explanations include monomorphic differentiation from a malignant mixed Müllerian tumour or even malignant change in a focus of osseous metaplasia.3–5

Histologically, the defining feature of osteosarcoma is the production of neoplastic osteoid, bony matrix or both; although diagnosis may be challenging due to its focal nature.6 Osteoid outlines individual cells or less commonly solid sheets of osteoid may be present. Tumours are generally cellular and composed of mitotically active spindle to epitheloid cells which show significant nuclear pleomorphism. The majority of the tumour is usually non-specific, undifferentiated sarcoma with areas of necrosis. Lobules of atypical hyaline cartilage may be present, with tumours potentially showing any histological pattern of osseous osteosarcoma. Immunohistochemistry is usually unhelpful; however, commonly expressed markers include: vimentin, osteocalcin, osteonectin, S-100, SMA, desmin, neuron-specific enolase and CD99.5

Uterine neoplasms displaying osteosarcomatous differentiation are most commonly malignant mixed Müllerian tumours, with this being an important differential diagnosis to consider.7 The distinction is made by identifying the presence of an epithelial component, seen in malignant mixed Müllerian tumours but not osteosarcomas. Extensive tumour sampling by the pathologist may be necessary to identify this component, as well as utilisation of cytokeratin immunohistochemistry.

The other unusual aspect to this case was the synchronous presentation of bilateral breast carcinomas with primary uterine osteosarcoma, raising the possibility of a mutual genetic pathogenesis. Sporadic osteosarcomas appear to result from the accrual of complex genetic alterations involving overexpression of oncogenes and inactivation of tumour suppressor genes. Few consistent genetic mutations have been identified in osteosarcomas; however, of relevance to this case is the loss of heterozygosity of the tumour suppressor gene BRCA1 (17q21.31) seen in some tumours.8 Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 impart an increased risk of developing breast cancer with increased rates of bilateral breast cancer.9 Of further interest is the association of breast carcinomas and osteosarcomas in Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS). LFS is a rare autosomal-dominant hereditary disorder predisposing to the development of multiple types of cancer, with most individuals found to have a germline mutation in the tumour suppressor gene p53.10 Families presenting with incomplete features of LFS are referred to as having Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome. “Molecular testing of the tumour tissue from this case is under consideration.”

In conclusion, this is an unusual case due to the rarity of primary uterine osteosarcoma and presentation synchronously in a woman with bilateral breast carcinomas. The distinction of osteosarcoma from the more common carcinosarcoma is important due to the worse prognosis impacting on treatment decisions. In addition, presentation of synchronous unusual tumours should raise the possibility of a genetic association or inherited disorder.

Learning points.

Primary uterine osteosarcomas are rare aggressive tumours with a poor prognosis.

Thorough tumour sampling by the pathologist is required to exclude an epithelial component to differentiate osteosarcoma from the more common differential diagnosis of malignant mixed Müllerian tumour.

Synchronous unusual tumours should raise the possibility of a genetic association or inherited disorder.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: None.

Provenance and peer review : Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Giuntoli RL, Metzinger DS, DiMarco CS, et al. Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol 2003;89:460–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang RC, Wen MC, Wang J, et al. Osteosarcoma arising in a long-standing uterine leiomyoma: a case report and literature review. Int J Surg Pathol 2011;19:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin JW, Ko SF, Ng SH, et al. Primary osteosarcoma of the uterus with peritoneal osteosarcomatosis: CT features. Br J Radiol 2002;75:772–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribeiro-Silva A, Ximenes L. A 60-year-old woman with diffuse uterine enlargement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:172–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen ML, Schumacher B, Jense OM, et al. Extraskeletal osteosarcomas: a clinicopathologic study of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:588–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soslow RA. Uterine mesenchymal tumors: a review of selected topics. Diagn Histopathol 2008;14:175–88 [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumors: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? J Clin Pathol 2002;55:321–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin J, Squire JA, Zielenska M. The genetics of osteosarcoma. Sarcoma 2012;2012:627254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weitzel JN, Robson M, Pasini B, et al. A comparison of bilateral breast cancers in BRCA carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1534–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, et al. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nig.gov/books/NBK1116/ (accessed 15 Jul 2013). [Google Scholar]