Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes can cause severe food-borne disease (listeriosis). Numerous outbreaks have involved three serotype 4b epidemic clones (ECs): ECI, ECII, and ECIa. However, little is known about the population structure of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b from sporadic listeriosis in the United States, even though most cases of human listeriosis are in fact sporadic. Here we analyzed 136 serotype 4b isolates from sporadic cases in the United States, 2003 to 2008, utilizing multiple tools including multilocus genotyping, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and sequence analysis of the inlAB locus. ECI, ECII, and ECIa were frequently encountered (32, 17, and 7%, respectively). However, annually 30 to 68% of isolates were outside these ECs, and several novel clonal groups were identified. An estimated 33 and 17% of the isolates, mostly among the ECs, were resistant to cadmium and arsenic, respectively, but resistance to benzalkonium chloride was uncommon (3%) among the sporadic isolates. The frequency of clonal groups fluctuated within the 6-year study period, without consistent trends. However, on several occasions, temporal clusters of isolates with indistinguishable genotypes were detected, suggesting the possibility of hidden multistate outbreaks. Our analysis suggests a complex population structure of serotype 4b L. monocytogenes from sporadic disease, with important contributions by ECs and several novel clonal groups. Continuous monitoring will be needed to assess long-term trends in clonality patterns and population structure of L. monocytogenes from sporadic listeriosis.

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a food-borne bacterial pathogen associated with significant human disease burden (1, 2). L. monocytogenes is often transmitted through ready-to-eat foods originating from contaminated food processing facilities; this is promoted by a variety of environmental adaptations of L. monocytogenes such as cold tolerance, biofilm formation, and resistance to disinfectants (3–7).

At special risk for listeriosis are pregnant women and their fetuses, the elderly, and immunosuppressed patients (1). Listeriosis can have severe symptoms, including septicemia, meningitis, stillbirths, and abortions, and continues to be associated with relatively high mortality (1, 2). Even though 13 serotypes have been recognized, most human cases involve strains of serotypes 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b (7–9).

Serotype 4b strains are responsible for many outbreaks of food-borne listeriosis (8). Three major epidemic clones (ECs), designated ECI, ECII, and ECIa (also referred to as ECIV), have been implicated in numerous outbreaks (10, 11). These ECs can be identified by their unique genomic markers and via numerous typing schemes, including multilocus genotyping (MLGT), multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA), and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (12–16).

In spite of attention to outbreaks, most human listeriosis cases are sporadic, with serotype 4b strains being important contributors (ca. 36%) (8, 17). However, our understanding of the population structure of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b from sporadic listeriosis in the United States remains severely limited. Strains from sporadic listeriosis from New York State were analyzed with MLST (18), but the relatively small number of serotype 4b isolates (n = 28) in that study and its regional focus do not permit extrapolations to the United States as a whole. We currently lack information on prevalence of ECI, ECII, or ECIa in the United States, and even less is known about the potential contributions to sporadic listeriosis of novel clonal groups that have not yet been documented to be associated with outbreaks. In this study, we employed multiple subtyping tools to characterize the clonal prevalence and overall population structure of a panel of 136 serotype 4b L. monocytogenes isolates from sporadic human listeriosis in the United States over the 6-year period from 2003 to 2008. In addition, we characterized this panel for selected environmental adaptations previously documented to be exhibited by certain strains of L. monocytogenes, including several involved in outbreaks, i.e., resistance to heavy metals (arsenic and cadmium) (19–22) and to the quaternary ammonium disinfectant benzalkonium chloride (BC) (23).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The isolates examined in this study (Table 1) were from the Listeria strain collection at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Atlanta, GA) and were obtained between 2003 and 2008 from invasive human listeriosis cases in the United States. The isolates (16 to 27 annually) were chosen based on (i) serotype 4b, (ii) lack of known association with outbreaks (i.e., sporadic incident of listeriosis), and (iii) maximal geographical representation; specifically, in any given year each isolate typically originated from a different state in the United States (Table 1). Bacteria were routinely grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) or on BHI plates containing 1.2% agar (Becton, Dickinson and Co.) at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Serotype 4b L. monocytogenes strains used in this study

| Strain | Isolation yr | State | Cda | BCa | Arsa | Clonal groupb | MLGT haplotype | Sau3AIc | MboIc | 85Md | Hsp001219d | LMSG_01573d | Non-ECIIC-WAPd | McrBd | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J2213 | 2003 | AZ | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2269 | 2003 | GA | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2275 | 2003 | PA | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2282 | 2003 | MD | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16 |

| J2302 | 2003 | CA | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2327 | 2003 | MI | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16 |

| J2353 | 2003 | IL | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2584 | 2003 | VT | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J2854 | 2004 | AZ | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J2985 | 2004 | IL | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3082 | 2004 | GA | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3106 | 2004 | NY | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3133 | 2004 | TX | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3180 | 2004 | CO | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3232 | 2004 | OK | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3410 | 2005 | SC | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3535 | 2005 | RI | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3559 | 2005 | GA | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3592 | 2005 | ME | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3709 | 2005 | NH | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3799 | 2005 | CT | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3916 | 2006 | NM | ■ | ■ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4001 | 2006 | TX | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4099 | 2006 | VA | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4116 | 2006 | ME | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4187 | 2006 | WI | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4253 | 2006 | TN | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4274 | 2006 | NH | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4297 | 2006 | PA | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4316 | 2006 | IA | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4429 | 2007 | OR | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4600 | 2007 | OK | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4685 | 2007 | MO | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4950 | 2008 | WI | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4977 | 2008 | NC | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4979 | 2008 | TX | ■ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J5043 | 2008 | MA | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5080 | 2008 | NM | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J5095 | 2008 | MD | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J5136 | 2008 | SC | ■ | □ | ■ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J5202 | 2008 | MS | □ | ■ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5354 | 2008 | UT | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5392 | 2008 | KY | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5478 | 2008 | IL | □ | □ | □ | ECI | 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 | − | + | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J2206 | 2003 | NJ | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 39 |

| J2230 | 2003 | MA | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.9_4b_US98_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16 |

| J2446 | 2003 | OH | ■ | ■ | □ | ECII | 1.9_4b_US98_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 29, 39 |

| J2685 | 2004 | NY | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 29 |

| J3006 | 2004 | TX | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 39 |

| J3033 | 2004 | IL | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 29 |

| J3075 | 2004 | CT | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3170 | 2004 | MI | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 29 |

| J3200 | 2004 | CT | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 16, 29 |

| J3333 | 2004 | MN | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3527 | 2005 | WI | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3565 | 2005 | IL | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3606 | 2005 | MI | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3785 | 2005 | MA | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.9_4b_US98_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3840 | 2005 | MD | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3881 | 2006 | CO | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 29 |

| J4101 | 2006 | WV | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4105 | 2006 | AL | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4120 | 2006 | OH | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4210 | 2006 | GA | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4485 | 2007 | MA | ■ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | 29 |

| J4610 | 2007 | ME | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J5172 | 2008 | MN | □ | □ | □ | ECII | 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 | + | + | □ | ■ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J2967 | 2004 | CA | ■ | □ | □ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3290 | 2004 | ME | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3419 | 2005 | CA | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3768 | 2005 | CO | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3921 | 2006 | CT | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4503 | 2007 | NY | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4948 | 2008 | GA | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4954 | 2008 | CT | ■ | □ | ■ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J5074 | 2008 | WI | □ | ■ | □ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5375 | 2008 | WA | □ | □ | □ | ECIa | 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J2621 | 2003 | OR | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 1 | 1.5_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 16 |

| J3917 | 2006 | CA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 1 | 1.5_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4010 | 2006 | NE | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 1 | 1.5_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4109 | 2006 | NJ | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 1 | 1.5_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3976 | 2006 | MA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 2 | 1.6_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4179 | 2006 | RI | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 2 | 1.6_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4726 | 2007 | FL | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 2 | 1.6_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J5032 | 2008 | PA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 2 | 1.6_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J2422 | 2003 | RI | ■ | □ | ■ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 16, 29 |

| J3120 | 2004 | WA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3309 | 2005 | IA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3618 | 2005 | NJ | ■ | □ | ■ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J3684 | 2005 | OR | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3795 | 2005 | AZ | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3909 | 2006 | OR | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4434 | 2007 | TN | ■ | □ | ■ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 29 |

| J4465 | 2007 | CO | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3415 | 2005 | TX | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 3 | 1.7_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3422 | 2005 | LA | ■ | □ | ■ | ND | 1.16_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 29 |

| J2255 | 2003 | GA | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 16, 26 |

| J3139 | 2004 | WI | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J3913 | 2006 | IN | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J4016 | 2006 | SC | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J4500 | 2007 | NE | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J5000 | 2008 | VA | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 1) | 1.17_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J3215 | 2004 | NJ | □ | □ | □ | 2000NC | 1.42_4b_NC00 | + | − | □ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J4045 | 2006 | MO | □ | □ | □ | 2000NC | 1.42_4b_NC00 | + | − | □ | □ | □ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J3085 | 2004 | MD | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3728 | 2005 | NY | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3793 | 2005 | WV | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4548 | 2007 | WI | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4713 | 2007 | RI | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J5502 | 2008 | NM | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 4 | 1.45_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3026 | 2004 | CT | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J3053 | 2004 | MI | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J3195 | 2004 | OH | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J4458 | 2007 | MN | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J4490 | 2007 | SC | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J4953 | 2008 | OH | □ | □ | □ | IVb-v1 (group 2) | 1.46_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | 26 |

| J3751 | 2005 | OH | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 5 | 1.58_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4432 | 2007 | PA | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 5 | 1.58_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3155 | 2004 | IL | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 6 | 1.59_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4696 | 2007 | SD | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 6 | 1.59_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J5421 | 2008 | FL | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 6 | 1.59_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3070 | 2004 | TN | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3554 | 2005 | MS | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J3762 | 2005 | IN | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4428 | 2007 | OH | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J4435 | 2007 | WI | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5038 | 2008 | MI | □ | □ | □ | Novel clonal group 7 | 1.62_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | This study |

| J5166 | 2008 | KS | □ | □ | □ | ND | 1.64_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | This study |

| J3182 | 2004 | OR | □ | □ | □ | ND | 1.71_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J3115 | 2004 | VA | □ | □ | □ | ND | 1.73_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | ■ | □ | 30 |

| J4221 | 2006 | MD | □ | □ | □ | ND | 1.75_4b | + | + | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | This study |

| J4291 | 2006 | NY | □ | □ | □ | ND | 1.76_4b | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | ■ | ■ | This study |

| J4460 | 2007 | GA | □ | □ | □ | ND | Untypeable LMOx(−)e | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | This study |

| J2571 | 2003 | KY | □ | □ | □ | Lineage III cluster | Lm3.42 | − | + | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | 16 |

| J2479 | 2003 | MI | □ | □ | □ | Lineage III cluster | Lm3.42 | + | − | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | 16, 30 |

| J3720 | 2005 | PA | □ | □ | □ | Lineage III cluster | Lm3.42 | + | + | □ | □ | ■ | □ | ■ | This study |

Black and white squares represent resistance and susceptibility, respectively, to cadmium (Cd), arsenic (Ars), and BC. Resistance was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined because isolates with such MLGT haplotypes were encountered only once in the panel.

+ and −, susceptibility and resistance, respectively, to digestion by the indicated restriction enzyme.

Black and white squares designate the presence and absence, respectively, of the signal in the hybridization with a DNA probe or PCR amplicon using the primers targeting the DNA probe.

This strain was untypeable by MLGT but belonged to lineage I according to the PCR-based lineage designation (35).

Serotyping and resistance to arsenic, cadmium, and BC.

The serotype was determined at the CDC as previously described (24) and reexamined at North Carolina State University using a multiplex PCR serotyping scheme (25), which also allowed identification of the recently recognized 4b subset IVb-v1 (Table 1) (26, 27). Resistance to arsenic, cadmium, and BC was determined as described previously (28) with the modification that cadmium-resistant isolates were those growing at ≥35 μg/ml cadmium chloride, reflecting our recent discovery of the association between a cadmium resistance determinant (cadA4) and growth at 35 μg/ml (but not at 70 μg/ml) cadmium chloride (29).

EC determination and molecular characterization.

Genomic DNA extractions and PCR were as described previously (30) using primers listed in Table 2. DNA probes (Table 2) were obtained by PCR using the indicated primers and hybridized to the immobilized genomic DNA as described previously (12). Probes specific to ECI and ECII were 85M and Hsp001219, respectively (Table 2) (12, 31). ECIa strains were identified based on hybridization patterns with probes LMSG_01573 and Non-ECIIC-WAP (positive signal) and probe McrB (negative) (12, 32, 33).

TABLE 2.

DNA probes and primers utilized in this study

| Probe | Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85M | F2365_85MF | AATATATTTTCAATGTTTGATGGT | LMOf2365_0327 | 31 |

| F2365_85MR | GCTAATTCAATCCCTATTCT | LMOf2365_0327 | 31 | |

| Hsp001219 | Hspec01219F | GAGGCTATCGAAATTGCTCG | LMOh7858_1168 | 12 |

| Hspec01219R | AGGATTCGGAATTTCATCCA | LMOh7858_1168 | 12 | |

| LMSG_01573 | LMSG_01573F | TACAATTGGTCGGACACGTG | LMSG_01573 | 32 |

| LMSG_01573R | AGAATCCGCTCATAAACAGC | LMSG_01573 | 32 | |

| Non-ECIIC-WAP | ECIC-WAPF | ATGGAAATTGGGCATGGC | LMOf2365_0450 | 12 |

| ECIC-WAPR | GTAGTTCCAGTGGACATG | LMOf2365_0450 | 12 | |

| McrB | H7858_0337F | ATATCCATGCCCATCACCAC | LMOh7858_0337 | 32 |

| H7858_0337R | CGGGAGGAATCTCGTTATAC | LMOh7858_0337 | 32 |

ECs were confirmed by MLGT as described previously (13, 26, 34). Prior to MLGT, lineage was determined via an allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR multiplex as previously described to determine whether the serotype 4b isolates were of lineage I or, as is found for a minority of serotype 4b strains, lineage III (35). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed at North Carolina State University with AscI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and ApaI (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), as described previously (36). PFGE profiles were analyzed with BioNumerics (Applied Maths, Austin, TX). Resistance of genomic DNA to Sau3AI and MboI (New England BioLabs) was determined as described previously (31); ECI strains are known to have DNA resistant to digestion by Sau3AI (cytosine methylation at GATC sites), while DNA from certain other strains is resistant to MboI (adenine methylation at GATC) (26, 31).

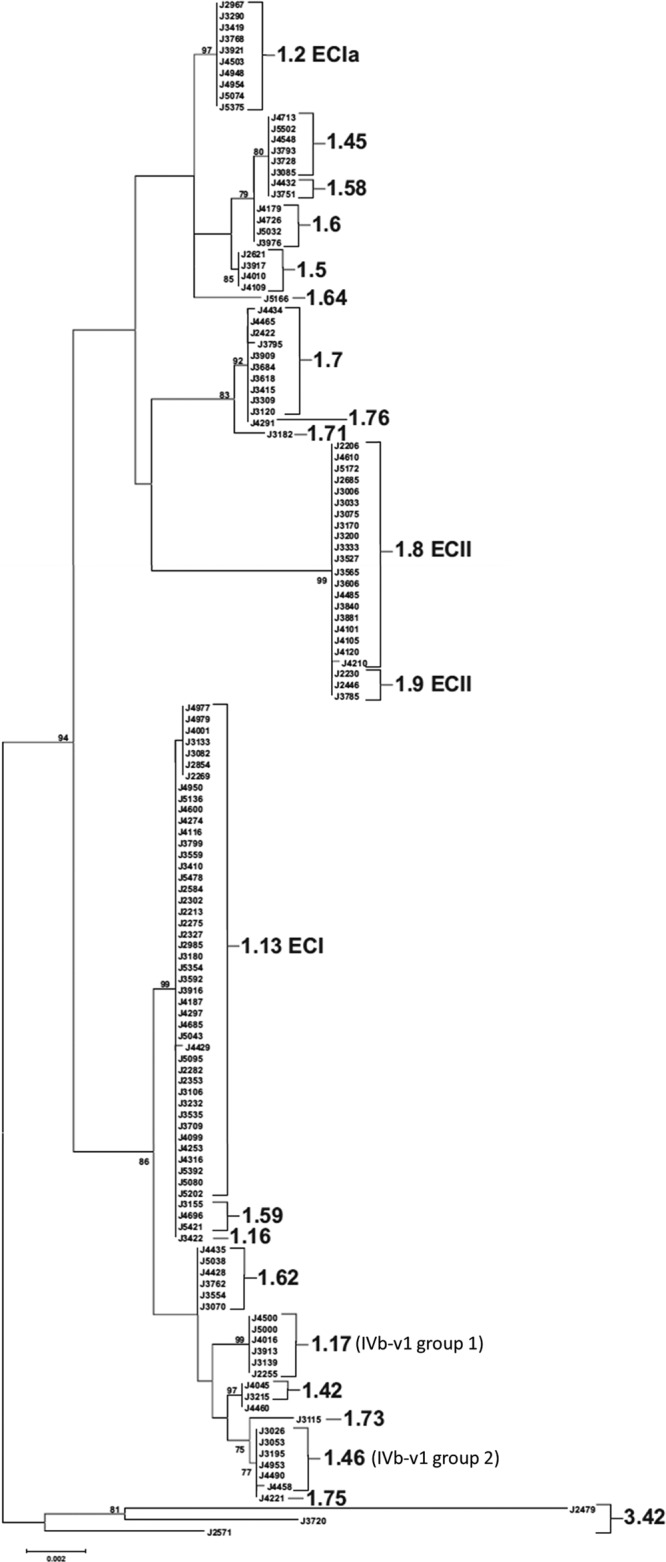

Phylogenetic analysis using inlAB sequencing.

DNA sequences from the inlA and inlB genetic region (inlAB locus; ∼4.3 kb) were used to assess phylogenetic relationships. PCR amplification and sequencing were performed as described previously (34). DNA sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm implemented in MEGA v. 5.05 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) (37). Phylogenetic relationships were inferred from aligned sequences using maximum likelihood as implemented in MEGA v. 5.05 using the GTR+G model of molecular evolution. The best-fit model of molecular evolution was selected based on estimates of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each of the 24 nucleotide substitution models included in MEGA v. 5.05. Support for individual nodes in the maximum likelihood tree was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications.

Statistics.

Fisher's exact test was conducted with SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Temporal trends were analyzed with the exact test of population differentiation (38) in Arlequin version 2.0 (CMPG; Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland) utilizing 100,000 Markov chain steps and 10,000 dememorization steps.

RESULTS

Fluctuation in annual prevalence of ECI, ECII, and ECIa among serotype 4b L. monocytogenes from sporadic listeriosis.

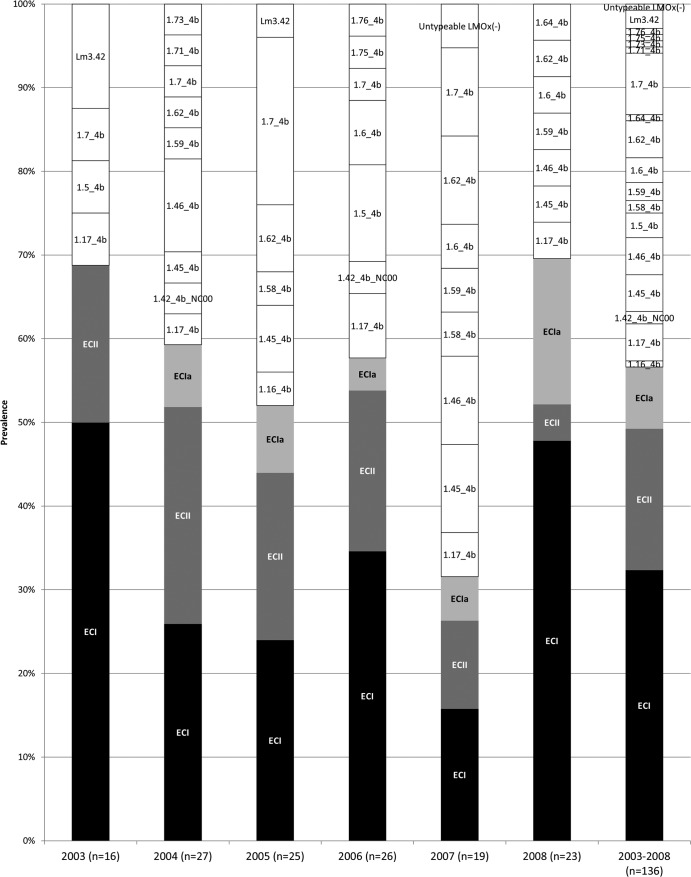

The majority (133/136) of the sporadic serotype 4b isolates were lineage I, while three were lineage III (Tables 1 and 3). ECI was the most predominant group, followed by ECII: these clonal groups accounted for 32 and 17% of the total, respectively, while 7% of the isolates were identified as ECIa (Fig. 1). The combined prevalence of ECI, ECII, and ECIa amounted to 57% of the total isolates, exceeding 50% of the annual total for 5 of the 6 years and ranging from 32% in 2007 to ca. 70% in 2003 and 2008 (Fig. 1). Pairwise comparisons of total EC prevalence across years failed to reveal significant differences, with the possible exceptions of 2007 versus 2003 (32 versus 69%, respectively; P = 0.045) and 2007 versus 2008 (32 versus 70%, respectively; P = 0.03).

TABLE 3.

MLGT haplotype distribution among the serotype 4b isolates in the panel

| MLGT haplotypea | Lineage | No. (%) of isolatesb | Yrs (no. of isolates)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| EC haplotypes | |||

| 1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1 (ECI) | I | 44 (32) | 2003 (8), 2004 (7), 2005 (6), 2006 (9), 2007 (3), 2008 (11) |

| 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2 (ECII) | I | 20 (15) | 2003 (1), 2004 (7), 2005 (4), 2006 (5), 2007 (2), 2008 (1) |

| 1.9_4b_US98_EC2 (ECII) | I | 3 (2) | 2003 (2), 2005 (1) |

| 1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a (ECIa) | I | 10 (7) | 2004 (2), 2005 (2), 2006 (1), 2007 (1), 2008 (4) |

| Non-EC haplotypes | |||

| 1.7_4b | I | 10 (7) | 2003 (1), 2004 (1), 2005 (5), 2006 (1), 2007 (2) |

| 1.17_4b (IVb-v1 group 1) (26) | I | 6 (4) | 2003 (1), 2004 (1), 2006 (2), 2007 (1), 2008 (1) |

| 1.45_4b | I | 6 (4) | 2004 (1), 2005 (2), 2007 (2), 2008 (1) |

| 1.46_4b (IVb-v1 group 2) (26) | I | 6 (4) | 2004 (3), 2007 (2), 2008 (1) |

| 1.62_4b | I | 6 (4) | 2004 (1), 2005 (2), 2007 (2), 2008 (1) |

| 1.5_4b | I | 4 (3) | 2003 (1), 2006 (3) |

| 1.6_4b | I | 4 (3) | 2006 (2), 2007 (1), 2008 (1) |

| 1.59_4b | I | 3 (2) | 2004 (1), 2007 (1), 2008 (1) |

| Lm3.42 | III | 3 (2) | 2003 (2), 2005 (1) |

| 1.42_4b_NC00 (North Carolina outbreak strain) | I | 2 (1) | 2004 (1), 2006 (1) |

| 1.58_4b | I | 2 (1) | 2005 (1), 2007 (1) |

| Unique haplotypes | I | 7 (5) | 2004 (2), 2005 (1), 2006 (2), 2007 (1), 2008 (1) |

Haplotypes were determined by MLGT as described in Materials and Methods. Unique haplotypes were those encountered only once in the panel (1.16_4b, 1.64_4b, 1.71_4b, 1.73_4b, 1.75_4b, 1.76_4b, and the MLGT-untypeable strain J4460).

Percentage of isolates with the indicated haplotype among the total isolates in the panel.

Multiple isolates of the same haplotype in the same year are indicated in boldface.

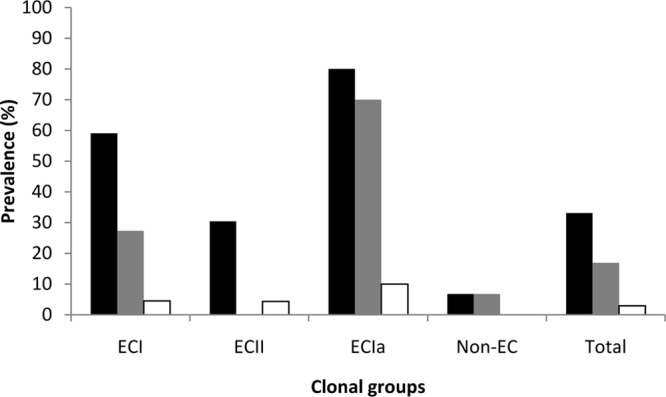

FIG 1.

Annual prevalence of ECI, ECII, ECIa, and non-EC isolates. Data for ECI, ECII, and ECIa are indicated with black, dark gray, and light gray, respectively. Non-EC isolates are in white, and MLGT haplotype designations are indicated.

ECI was a major contributor to the serotype 4b population each year, ranging in prevalence from 16 to 50% (Fig. 1). Annual fluctuations were also noted for ECII and ECIa (prevalence ranging from 4 to 26% and from 0 to 17%, respectively) (Fig. 1). However, we did not detect any consistent trends in these fluctuations and year-to-year changes were not significant, with the possible exception of ECI prevalence for 2007 and 2008 (16 versus 48%, respectively; P = 0.048).

Intra-EC diversity in serotype 4b L. monocytogenes from sporadic listeriosis.

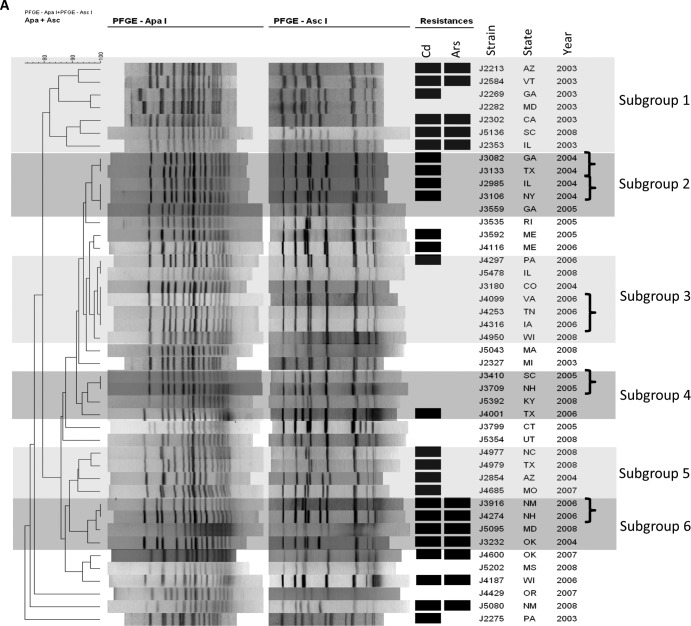

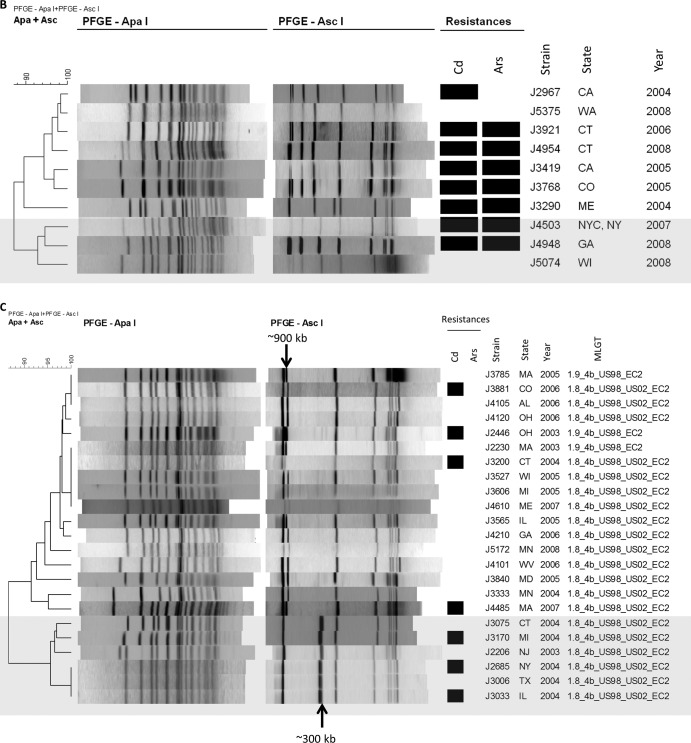

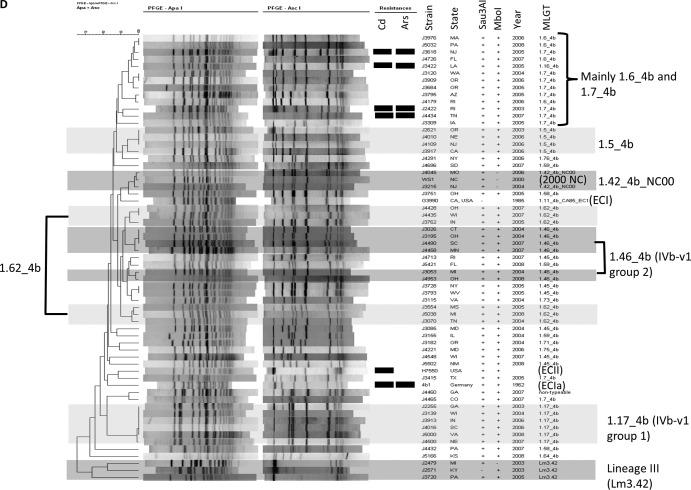

Diversity within individual ECs was examined with MLGT, PFGE, and comparison of inlAB sequences. Even though multiple closely related MLGT haplotypes were previously identified among ECI strains (13, 26), a single haplotype (1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1) was noted for all ECI isolates in our panel (Tables 1 and 3). However, diversity among ECI isolates was suggested by analysis of PFGE profiles, which revealed several subgroups, including six major ones (Fig. 2A). On several occasions, two or more isolates with indistinguishable PFGE profiles were from the same year, suggesting the possibility of unrecognized common-source transmission (hidden outbreaks) (Fig. 2A). For instance, five occasions (each involving 2 to 3 isolates) were identified in which ECI isolates from the same year exhibited PFGE profiles of 100% similarity (Fig. 2A). Analyses of inlAB sequences (Fig. 3) revealed three sequence types within the ECI group, including one represented by a single strain and another represented by seven isolates from different years; the latter were found in various subgroups in the PFGE-based dendrogram (Fig. 2A). Most ECI isolates shared the same inlAB sequence type with isolates having MLGT haplotypes 1.59_4b and 1.16_4b (Fig. 3). However, strains with MLGT haplotypes 1.59_4b or 1.16_4b did not share the ECI-specific hybridization profile or resistance to Sau3AI (Table 1).

FIG 2.

PFGE-based dendrograms of ECI (A), ECIa (B), ECII (C), and non-EC (D) isolates. Resistance to cadmium (Cd) and arsenic (Ars) is indicated by black rectangles. Major subgroups within ECI and non-EC isolates are in various shades of gray (A and D). (A) Isolates displaying PFGE profiles with 100% similarity and collected from the same year are marked with brackets. (B and C) The larger subgroup is unshaded, while the smaller one is shaded in gray. (D) Representative EC strains and the 2000 North Carolina outbreak strain are included for comparison: G3990 (1985 California outbreak, ECI), H7550 (1998-1999 hot dog outbreak, ECII), 4b1 (ECIa), and WS1 (2000 North Carolina outbreak). MLGT haplotypes are indicated for ECII isolates. The same haplotype was found in all ECI (1.13_4b_Sw87_EC1) and ECIa (1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a) isolates (Table 1).

FIG 3.

Maximum likelihood tree inferred from analysis of inlAB sequences as described in Materials and Methods. MLGT results are shown to the right of individual isolates or clades, with the exception of J4460, which could not be fully typed using the MLGT method. Epidemic clonal groups are annotated according to Ducey et al. (13). The tree was rooted with sequences from lineage III strains. The frequency (%) with which a given branch was recovered in 1,000 bootstrap replications is shown for branches recovered in more than 70% of bootstrap replicates.

Similarly to ECI, all ECIa isolates exhibited the same MLGT haplotype (1.2_4b_UK88_EC1a) (Tables 1 and 3), although four MLGT haplotypes were previously detected among ECIa strains (13, 26). ECIa isolates clustered together as a single group with identical inlAB sequences in the inlAB-based phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3). Their PFGE profiles were also highly similar, but minor variations were noted, revealing two subgroups, one of which consisted of three isolates (J4503, J4948, and J5074) from 2007 and 2008 (Fig. 2B).

Two of the three known ECII MLGT haplotypes (13, 26) were noted among ECII isolates (Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 2C). Haplotype 1.9_4b_US98_EC2, identified in some of the isolates from the 1998-1999 hot dog outbreak, was detected in three isolates: J2230, J2246 (both from 2003), and J3785 (from 2005) (Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 2C) (13). All other ECII isolates had haplotype 1.8_4b_US98_US02_EC2, first identified among certain isolates from the 1998-1999 hot dog outbreak as well as those from the 2002 turkey deli meat outbreak (Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 2C) (13, 39). In the phylogenetic tree inferred from inlAB sequences, all ECII isolates formed a single group (Fig. 3); however, PFGE analysis revealed two major subgroups in ECII: one (n = 17) had two high-molecular-weight AscI bands at approximately 900 kb, while the other (n = 6) had one band at approximately 900 kb and an additional AscI band of approximately 300 kb (Fig. 2C). With the exception of one isolate from 2003, the isolates in the latter group were from 2004 (Fig. 2C). The three isolates with MLGT haplotype 1.9_4b_US98_EC2 belonged to the former group (Fig. 2C).

Non-EC isolates represent diverse strains and several novel clonal groups.

In any given year, 30 to 68% of isolates (43% of the total panel) did not belong to ECI, ECII, or ECIa (Fig. 1). The prevalence of such non-EC isolates was especially high (68%) in 2007 (significantly higher than in 2003 and 2008, with P values of 0.045 and 0.03, respectively).

Diversity among these non-EC isolates was assessed with MLGT and further examined with PFGE, comparison of inlAB sequences, Sau3AI/MboI resistance, and hybridization profiles. A total of 17 MLGT haplotypes were identified among the 59 non-EC isolates, while one strain (J4460) was not fully typeable with MLGT (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Eleven of these haplotypes were identified among ≥2 isolates (Table 3). With the exception of the three lineage III strains with MLGT haplotype Lm3.42, non-EC isolates with the same MLGT haplotype exhibited the same hybridization profiles and Sau3AI/MboI resistance phenotypes, had indistinguishable or highly similar PFGE profiles, and were indistinguishable or closely related in the inlAB-based phylogenetic tree (Table 1; Fig. 2D and 3). Such data strongly suggest that serotype 4b lineage I isolates sharing the same haplotype belong to the same clonal group.

Each year, 4 to 9 different MLGT haplotypes were noted among non-EC isolates (Fig. 1), and except for 2008, 1 to 4 MLGT haplotypes were identified more than once each year (Table 3). Especially noteworthy was the high prevalence of isolates of haplotype 1.7_4b in 2005; of the 12 non-EC isolates in that year, 5 (42%) were 1.7_4b (Table 3). Other examples include the identification of three 1.5_4b isolates in 2006 and three 1.46_4b in 2004 (Table 3).

Only two non-EC isolates had strain genotypes previously implicated in an outbreak. These isolates (J3215 and J4045) shared the same MLGT haplotype (1.42_4b_NC00), PFGE profile, and hybridization pattern with strains from the 2000 North Carolina outbreak (12, 13, 40) (Table 1 and Fig. 2D). Similarly to the North Carolina outbreak strains, their DNA was resistant to MboI digestion (Table 1) (41). However, they were collected from different locations in different years (2004 and 2006) and were thus unlikely to be members of a common-source cluster (Tables 1 and 3). These findings suggest that, albeit uncommon in the strain panel, the North Carolina outbreak strain exhibits persistence and geographic dispersal with minimal modification.

Two clonal groups, with haplotypes 1.17_4b (n = 6) and 1.46_4b (n = 6), consisted of isolates with the previously reported atypical profile IVb-v1 based on multiplex PCR for serotype designations (Tables 1 and 3) (26, 27). In the inlAB-based phylogenetic tree, isolates with these haplotypes were in a diverse clade that also included ECI along with the isolates from the 2000 North Carolina outbreak (1.42_4b_NC00 haplotype) (Fig. 3). Several IVb-v1 isolates with the same haplotype were from the same year (e.g., three 1.46_4b isolates from 2004 and two from 2007) (Tables 1 and 3). These isolates had the same inlAB sequences, hybridization profiles, and Sau3AI/MboI resistance phenotypes and exhibited indistinguishable or closely related PFGE profiles, possibly reflecting unrecognized outbreaks involving these strains (Table 1; Fig. 2D and 3).

As mentioned earlier, the panel included three lineage III isolates (Tables 1 and 3). These shared the same MLGT haplotype (Lm3.42) and formed a distinct cluster when analyzed with PFGE and inlAB sequencing (Fig. 2D and 3). Two isolates, both from 2003, exhibited highly similar AscI patterns and the same hybridization profile (Table 1 and Fig. 2D). However, the combined PFGE, inlAB sequences, hybridization and Sau3AI/MboI susceptibility data suggested that each of the three lineage III isolates was a distinct strain (Table 1; Fig. 2D and 3).

Resistance to BC is infrequent among sporadic case isolates, while resistance to cadmium or arsenic is significantly more common in ECs than among non-EC isolates.

Of the 136 isolates in the panel, only 4 (3%) were resistant to BC (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In contrast, heavy metal resistance was relatively common: 45 (33%) and 23 (17%) of the isolates could grow at 35 μg/ml cadmium chloride and 500 μg/ml sodium arsenite, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 4). All 23 arsenic-resistant isolates were also resistant to cadmium, while the reverse was not observed; about one-half (22/45) of the cadmium-resistant isolates were susceptible to arsenic (Table 1). Only one strain (J3916, ECI) exhibited coresistance to cadmium, arsenic, and BC (Table 1).

FIG 4.

Prevalence of resistance to cadmium, arsenic, and BC among ECI, ECII, ECIa, and non-EC isolates. Resistance to cadmium, arsenic, and BC is shown in black, gray, and white bars, respectively. Resistance was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

The prevalence of cadmium resistance among EC isolates (53%) was significantly higher than among non-EC isolates (7%; P < 0.0001); cadmium resistance among each EC group was more frequent than among non-EC isolates (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4), but prevalence among ECII was lower than among ECI or ECIa isolates (P < 0.02). A similar finding was obtained when resistance to arsenic was compared between EC and non-EC isolates (25% in EC versus 7% in non-EC isolates, P = 0.006); however, only ECI and ECIa contributed to this difference (P < 0.01), with ECIa exhibiting a significantly higher prevalence than ECI (P = 0.024) (Fig. 4). BC resistance was not encountered among non-EC isolates; the four BC-resistant isolates consisted of ECI (n = 2), ECII (n = 1), and ECIa (n = 1) (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

In the PFGE dendrogram of ECI, two subgroups (1 and 6 in Fig. 2A) were primarily composed of isolates coresistant to cadmium and arsenic (5/7 in subgroup 1 and all 4 in subgroup 6), while most isolates in subgroups 2 and 5 were resistant only to cadmium (Fig. 2A). Among other isolates, however, resistance to cadmium and arsenic was not associated with a particular PFGE-based cluster (Table 1 and Fig. 2B to D). In the inlAB sequence analyses, all seven isolates (J2269, J2854, J3082, J3133, J4001, J4977, and J4979) sharing one of the aforementioned three ECI sequence types were resistant to cadmium but not to arsenic (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Population studies of serotype 4b L. monocytogenes have focused mainly on outbreak strains; little is known regarding the population structure and longitudinal trends of isolates from sporadic listeriosis, even though strains of serotype 4b are responsible for a considerable portion (ca. 36%) of sporadic cases (17). Our analysis of the 136 serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis in the United States in the 2003-to-2008 period showed that the known epidemic clones were responsible for over one-half of the sporadic cases and were continuously causing listeriosis during this period. Since the isolates were collected during a relatively short time frame (6 years), further studies are needed to characterize the temporal dynamics and population trends of serotype 4b L. monocytogenes responsible for sporadic listeriosis.

A previous longitudinal study of the population structure of clinical L. monocytogenes isolates employed MLST and included 58 serotype 4b isolates from sporadic listeriosis in France from 1987 to 2005 (15). ECI, ECII, and ECIa comprised 34, 7, and 14%, respectively, of the serotype 4b sporadic isolates in that study (15). ECII was identified only in three years (1998, 2003, and 2004), possibly reflecting the relatively recent emergence of this clone, which was first recognized during the 1998-1999 hot dog outbreak of listeriosis in the United States (15, 41, 42). Comparable data from the United States have been lacking; however, MLST investigation of 28 serotype 4b isolates from sporadic listeriosis in New York State (1999 to 2003) also revealed that ECI, ECII, and ECIa were the most common contributors (19/28, ca. 68%) (14, 18).

The mechanisms responsible for the frequent involvement of these three clonal groups in sporadic listeriosis remain poorly understood. The strains may have unusually high human virulence in comparison to others of the same serotype. Furthermore, many studies indicate that ECI, ECII, and ECIa generally predominate among serotype 4b isolates from foods and food processing plants (31, 32, 34, 41, 43, 44), suggesting that their high prevalence in human disease may also reflect common human exposure to these ECs via contaminated food.

In spite of the major contributions of ECs to sporadic listeriosis, our analysis also revealed that a substantial fraction (30 to 68% annually) of the isolates were not ECI, ECII, or ECIa. These non-EC serotype 4b isolates formed a heterogeneous population that included several strain clusters with conserved MLGT haplotypes, inlAB locus sequences, PFGE profiles, hybridization profiles, and Sau3AI/MboI susceptibility phenotypes. Identification of multiple isolates with the same haplotype (and with other conserved molecular attributes) in a single year was noted on several occasions, possibly reflecting unrecognized outbreaks. This may have been the case for some of the ECI, ECII, or ECIa isolates as well; isolates of the same EC and from the same year often exhibited unusually high similarity in PFGE profiles, possibly reflecting a common-source origin.

Lineage III strains are primarily associated with animal listeriosis, with roughly 1% of human listeriosis cases attributed to this lineage (45, 46). An intriguing finding from the current study of sporadic listeriosis isolates was that all three lineage III serotype 4b strains were of the same MLGT haplotype (Lm3.42). Analysis of a broader collection of 90 lineage III isolates subtyped via MLGT revealed that the majority (14/15, 93%) with MLGT haplotype Lm3.42 were from human clinical cases, whereas human clinical isolates comprised only 40% (30 of 75 isolates) of the lineage III isolates with other MLGT haplotypes (T. J. Ward, unpublished data). The identification of the Lm3.42 strains in the current panel may reflect enhanced virulence or possibly enhanced fitness in food processing or other environments that results in higher frequencies of human exposure to these strains than to other strains of lineage III.

Even though major outbreaks of listeriosis have involved strains resistant to the disinfectant BC (23), BC resistance was infrequent (only 4 of the 136 isolates) among the sporadic listeriosis isolates characterized here. It is possible that disinfectant resistance is less likely to be encountered among isolates from sporadic cases than among those implicated in outbreaks. Outbreak strains may have had prolonged residence in the processing plant environment (where disinfectants are commonly used) and thus greater potential to become involved in large-scale food contamination events that may lead to outbreaks.

Arsenic- and cadmium-resistant isolates from the current panel were previously analyzed for the genetic determinants conferring resistance to these heavy metals (29). Findings from the current study clearly suggest that prevalence of heavy metal resistance was significantly higher among EC isolates than non-EC isolates. Furthermore, the findings suggest differences in prevalence of resistance among the ECs. Most notably, arsenic resistance was significantly more common among ECIa isolates than those of ECI and not encountered at all among ECII isolates; similar findings were obtained from an investigation of arsenic resistance among serotype 4b isolates from foods and food processing environments (32). The reasons for the apparent association of arsenic resistance with specific clonal groups remain to be elucidated.

Previous studies indicated that cadmium-resistant strains were more likely to be repeatedly isolated from foods than susceptible strains (20), but the potential impact of heavy metal resistance on the ability of L. monocytogenes to persist in food processing plants or foods remains poorly understood. Also, it is worth noting that several outbreaks of listeriosis have involved heavy metal-resistant strains. For instance, cadmium-resistant ECII strains were involved in the 1998-1999 and 2002 outbreaks (involving hot dogs and turkey deli meats, respectively), while ECIa strains resistant to both arsenic and cadmium were implicated in the 1983 Massachusetts outbreak and a milk-related outbreak in 2007 (21, 22, 47) (S. Lee and S. Kathariou, unpublished data). The potential consequences of heavy metal resistance on fitness of L. monocytogenes in foods, in the environment, or in the human host merit further research.

In conclusion, characterization of serotype 4b isolates from sporadic listeriosis in 2003 to 2008 revealed that clonal groups implicated in outbreaks (ECI, ECII, and ECIa) were also major contributors to sporadic cases and often exhibited resistance to heavy metals. In addition, we identified a number of other (non-EC) clonal groups not yet documented to be involved in outbreaks. On several occasions, these novel clonal groups were detected in multiple isolates from the same year, possibly reflecting unrecognized common-source outbreaks. Further studies are warranted to enhance our understanding of the dynamics of the population structure and special adaptive attributes (e.g., heavy metal resistance) of serotype 4b isolates responsible for sporadic listeriosis in the United States and elsewhere and to elucidate the contributions of novel, non-EC clonal groups to human disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by USDA grant 2006-35201-17377 and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Research Service.

We thank Peter Gerner-Smidt for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank all members of our laboratories for discussions and support during this project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 April 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Painter J, Slutsker L. 2007. Listeriosis in humans, p 85–110 In Ryser ET, Marth EH. (ed), Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:7–15. 10.3201/eid1701.09-1101p1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpentier B, Cerf O. 2011. Persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food industry equipment and premises. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 145:1–8. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva EP, De Martinis EC. 2013. Current knowledge and perspectives on biofilm formation: the case of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97:957–968. 10.1007/s00253-012-4611-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi M, Chikindas ML. 2007. Listeria: a foodborne pathogen that knows how to survive. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 113:1–15. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kornacki JL, Gurtler JB. 2007. Incidence and control of Listeria in food processing facilities, p 681–766 In Ryser ET, Marth EH. (ed), Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety, 3rd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kathariou S. 2002. Listeria monocytogenes virulence and pathogenicity, a food safety perspective. J. Food Prot. 65:1811–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P. 2007. The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes Infect. 9:1236–1243. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasanov U, Hughes D, Hansbro PM. 2005. Methods for the isolation and identification of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes: a review. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:851–875. 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Y, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2008. Genomic divisions/lineages, epidemic clones, and population structure, p 337–358 In Liu D. (ed), Handbook of Listeria monocytogenes, 1st ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Zhang W, Knabel SJ. 2007. Multi-virulence-locus sequence typing identifies single nucleotide polymorphisms which differentiate epidemic clones and outbreak strains of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:835–846. 10.1128/JCM.01575-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng Y, Kim JW, Lee S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2010. DNA probes for unambiguous identification of Listeria monocytogenes epidemic clone II strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:3061–3068. 10.1128/AEM.03064-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducey TF, Page B, Usgaard T, Borucki MK, Pupedis K, Ward TJ. 2007. A single-nucleotide-polymorphism-based multilocus genotyping assay for subtyping lineage I isolates of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:133–147. 10.1128/AEM.01453-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Bakker HC, Didelot X, Fortes ED, Nightingale KK, Wiedmann M. 2008. Lineage specific recombination rates and microevolution in Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:277. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ragon M, Wirth T, Hollandt F, Lavenir R, Lecuit M, Le Monnier A, Brisse S. 2008. A new perspective on Listeria monocytogenes evolution. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000146. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperry KE, Kathariou S, Edwards JS, Wolf LA. 2008. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis as a tool for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1435–1450. 10.1128/JCM.02207-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varma JK, Samuel MC, Marcus R, Hoekstra RM, Medus C, Segler S, Anderson BJ, Jones TF, Shiferaw B, Haubert N, Megginson M, McCarthy PV, Graves L, Gilder TV, Angulo FJ. 2007. Listeria monocytogenes infection from foods prepared in a commercial establishment: a case-control study of potential sources of sporadic illness in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:521–528. 10.1086/509920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Bakker HC, Fortes ED, Wiedmann M. 2010. Multilocus sequence typing of outbreak-associated Listeria monocytogenes isolates to identify epidemic clones. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7:257–265. 10.1089/fpd.2009.0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLauchlin J, Hampton MD, Shah S, Threlfall EJ, Wieneke AA, Curtis GD. 1997. Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes on the basis of plasmid profiles and arsenic and cadmium susceptibility. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:381–388. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey J, Gilmour A. 2001. Characterization of recurrent and sporadic Listeria monocytogenes isolates from raw milk and nondairy foods by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, monocin typing, plasmid profiling, and cadmium and antibiotic resistance determination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:840–847. 10.1128/AEM.67.2.840-847.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2010. Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the turkey processing plant environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:627–630. 10.1128/AEM.01751-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buchanan RL, Klawitter LA, Bhaduri S, Stahl HG. 1991. Arsenite resistance in Listeria monocytogenes. Food Microbiol. 8:161–166. 10.1016/0740-0020(91)90009-Q [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elhanafi D, Dutta V, Kathariou S. 2010. Genetic characterization of plasmid-associated benzalkonium chloride resistance determinants in a Listeria monocytogenes strain from the 1998-1999 outbreak. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:8231–8238. 10.1128/AEM.02056-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeliger HPR, Höhne K. 1979. Serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes and related species. Methods Microbiol. 13:31–49. 10.1016/S0580-9517(08)70372-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doumith M, Buchrieser C, Glaser P, Jacquet C, Martin P. 2004. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3819–3822. 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3819-3822.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Ward TJ, Graves LM, Wolf LA, Sperry K, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2012. Atypical Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strains harboring a lineage II-specific gene cassette. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:660–667. 10.1128/AEM.06378-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leclercq A, Chenal-Francisque V, Dieye H, Cantinelli T, Drali R, Brisse S, Lecuit M. 2011. Characterization of the novel Listeria monocytogenes PCR serogrouping profile IVb-v1. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 147:74–77. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2008. Heavy-metal and benzalkonium chloride resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the environment of turkey-processing plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1464–1468. 10.1128/AEM.02426-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Rakic-Martinez M, Graves LM, Ward TJ, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2013. Genetic determinants for cadmium and arsenic resistance among Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis patients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:2471–2476. 10.1128/AEM.03551-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Ward TJ, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2012. Two novel type II restriction-modification systems occupying genomically equivalent locations on the chromosomes of Listeria monocytogenes strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:2623–2630. 10.1128/AEM.07203-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yildirim S, Lin W, Hitchins AD, Jaykus LA, Altermann E, Klaenhammer TR, Kathariou S. 2004. Epidemic clone I-specific genetic markers in strains of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b from foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4158–4164. 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4158-4164.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratani SS, Siletzky RM, Dutta V, Yildirim S, Osborne JA, Lin W, Hitchins AD, Ward TJ, Kathariou S. 2012. Heavy metal and disinfectant resistance of Listeria monocytogenes from foods and food processing plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:6938–6945. 10.1128/AEM.01553-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S. 2011. PhD thesis North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ward TJ, Evans P, Wiedmann M, Usgaard T, Roof SE, Stroika SG, Hise K. 2010. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes from U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service surveillance of ready-to-eat foods and processing facilities. J. Food Prot. 73:861–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward TJ, Gorski L, Borucki MK, Mandrell RE, Hutchins J, Pupedis K. 2004. Intraspecific phylogeny and lineage group identification based on the prfA virulence gene cluster of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186:4994–5002. 10.1128/JB.186.15.4994-5002.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves LM, Swaminathan B. 2001. PulseNet standardized protocol for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes by macrorestriction and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 65:55–62. 10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00501-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousset F, Raymond M. 1995. Testing heterozygote excess and deficiency. Genetics 140:1413–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward TJ, Usgaard T, Evans P. 2010. A targeted multilocus genotyping assay for lineage, serogroup, and epidemic clone typing of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6680–6684. 10.1128/AEM.01008-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacDonald PD, Whitwam RE, Boggs JD, MacCormack JN, Anderson KL, Reardon JW, Saah JR, Graves LM, Hunter SB, Sobel J. 2005. Outbreak of listeriosis among Mexican immigrants as a result of consumption of illicitly produced Mexican-style cheese. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:677–682. 10.1086/427803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eifert JD, Curtis PA, Bazaco MC, Meinersmann RJ, Berrang ME, Kernodle S, Stam C, Jaykus LA, Kathariou S. 2005. Molecular characterization of Listeria monocytogenes of the serotype 4b complex (4b, 4d, 4e) from two turkey processing plants. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2:192–200. 10.1089/fpd.2005.2.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 1999. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998-1999. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 47:1117–1118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Franciosa G, Scalfaro C, Maugliani A, Floridi F, Gattuso A, Hodzic S, Aureli P. 2007. Distribution of epidemic clonal genetic markers among Listeria monocytogenes 4b isolates. J. Food Prot. 70:574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chenal-Francisque V, Lopez J, Cantinelli T, Caro V, Tran C, Leclercq A, Lecuit M, Brisse S. 2011. Worldwide distribution of major clones of Listeria monocytogenes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1110–1112. 10.3201/eid/1706.101778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeffers GT, Bruce JL, McDonough PL, Scarlett J, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. 2001. Comparative genetic characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from human and animal listeriosis cases. Microbiology 147:1095–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiedmann M, Bruce JL, Keating C, Johnson AE, McDonough PL, Batt CA. 1997. Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect. Immun. 65:2707–2716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2008. Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes infections associated with pasteurized milk from a local dairy—Massachusetts, 2007. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 57:1097–1100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]