Abstract

The incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) rises with age. Among adult IPD patients, the avidity of antipneumococcal polysaccharide antibodies against the infecting serotype increased with age and severity of disease, indicating that susceptibility to IPD in the elderly may rather be due to flaws in other aspects of opsonophagocytosis.

TEXT

Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) causes an estimated 1.6 million deaths per year worldwide (1). The highest burden of IPD is among the elderly (2), and from the age of 50, the incidence of IPD increases with age (3). Antibodies directed at the pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPS) capsule have been shown to be highly protective against IPD in children, as illustrated by the high effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (4, 5). Moreover, in infants the effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines correlates with a protective anti-PPS antibody concentration of ≥0.35 μg/ml (6). In nonvaccinated adults, the anti-PPS antibody levels generally increase with advancing age against a broad spectrum of pneumococcal serotypes (7). However, little is known about the functional quality of these anti-PPS antibodies in the elderly. High-avidity anti-PPS antibodies have been reported to be more effective in opsonophagocytosis of the pneumococcus in vitro and in protecting mice from lethal bacteremia (8). Although one study reported lower pneumococcal opsonization by naturally acquired antipneumococcal antibodies in the elderly (mean age, 79 years; range, 65 to 97 years) than in younger adults (9), the avidity of anti-PPS antibodies in the elderly has mainly been studied in the context of pneumococcal vaccination. Despite an apparent decrease in functional quality of vaccine-elicited antibodies with aging (10, 11), it is unknown whether the avidity of anti-PPS antibodies actually plays a role in the acquisition and severity of IPD in nonvaccinated adults. In this study, we investigated whether unvaccinated adults with a bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia had a low concentration or avidity of anti-PPS antibodies. In addition, it was studied whether avidity was negatively associated with age and severity of disease.

Twenty-seven adults hospitalized with a blood culture-proven pneumococcal pneumonia at a Dutch hospital between January 2009 and June 2011 from whom a stored serum sample collected at the day of admission was available were included in the study. Ages of IPD patients ranged from 28 to 89 years. To assess whether antibody avidities against the infecting serotype were lower in IPD patients than in healthy adults, a control pool of healthy unvaccinated volunteer serum was prepared by mixing equal amounts of serum from 14 volunteers between 21 and 50 years old. This observational study was approved by the Local Medical Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals. Determination of the anti-PPS antibody concentrations was performed according to the WHO training manual for Pn PS enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (007sp version) (12). Duplicates of the serum samples were prediluted 4 times and further diluted by 2-fold titration 12 times. The U.S. Reference Pneumococcal antiserum (89SF for serotypes 8, 9N, 12F, and 20 and 007sp for serotypes 1, 3, 4, 7F, 9V, 19A, and 19F) was included as a sample in each microtiter plate. Alongside this protocol, antibody avidity was determined by elution of one duplicate with 2.5 M sodium isothiocyanate (NaSCN), a chaotropic agent that weakens antigen-antibody interactions. The avidity index was defined as the ratio between NaSCN-treated and untreated antibody binding signals expressed in concentrations as inferred from the reference serum. In IPD patients, the serum IgG concentration and avidity against their infecting serotype were determined, as well as for the pooled control serum to each pneumococcal serotype isolated from the IPD patients in this study. In addition, the serum IgG concentration against a noninfecting serotype was measured for each IPD patient. Serotype 19A was selected as the noninfecting serotype because this is a serotype not included in the 10-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine to which adults in The Netherlands are relatively frequently exposed via nasopharyngeal carriage (13).

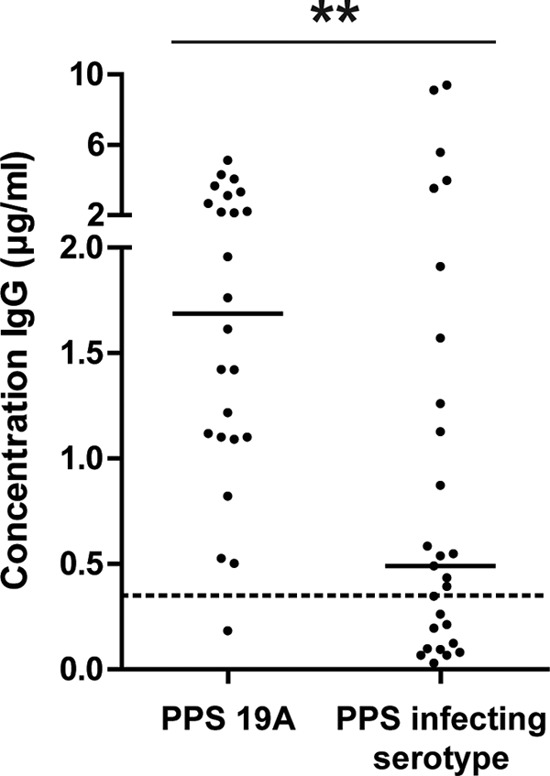

In 41% of the IPD patients, the IgG antibody concentrations against the infecting serotype were below the pediatric protective level of 0.35 μg/ml at hospital admission compared with 4% of antibody concentrations against a noninfecting serotype, 19A (Fisher exact test P = 0.0025; Fig. 1). Because in adults protective anticapsular antibody levels have never been established and might vary by serotype, it is unknown to what extent comparing antibody levels for different serotypes is appropriate here. Nonetheless, in comparison to anti-PPS 19A antibody levels, the IgG concentrations against the infecting serotypes were particularly low among IPD patients. Low levels of antibody against the infecting serotype indicate that the IPD patients may have had a serotype-specific deficit in IgG antibodies that made them vulnerable to infection or that antibodies against the infecting serotype had already been expended at the time of hospital admission. A preexisting deficit would be less likely if the avidity of these antibodies is similar to the avidity of those in healthy adults, indicating that the process from antigen presentation to affinity-maturated antibody production was not disturbed.

FIG 1.

Concentrations of IgG antibodies in IPD patients are lower against the PPS of the infecting serotype than against PPS 19A (two patients infected with serotype 19A excluded). Short horizontal lines, medians. Dashed line, protective antibody concentration in infants. **, P < 0.01.

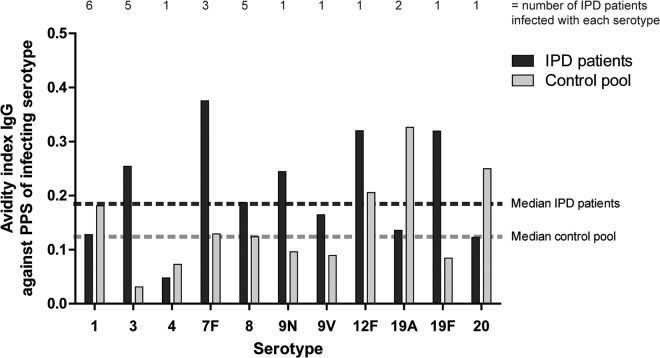

In IPD patients, the median IgG antibody avidity against their infecting serotypes was 0.19. For the control pool, a similar distribution of IgG antibody avidities was observed against the 11 serotypes considered (median, 0.12; Mann-Whitney U test, P = 0.21; Fig. 2). Notably, IgG antibody concentration and avidity were not inversely correlated in IPD patients (Pearson r = −0.01, P = 0.2). The similar antibody avidity against the infecting serotype in IPD patients compared with healthy controls differs from what was observed in a previous study in which a lower avidity of antibodies against the infecting serotype was observed (14). An important difference with our study is that in the previous study the healthy adult control group was a selection of highest responders after 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination, whereas our controls were unvaccinated like the IPD patients, which may be more informative on differences in susceptibility to pneumococcal disease.

FIG 2.

Similar avidities of anti-PPS IgG antibodies were measured in IPD patients against the infecting serotype compared to the healthy control pool. Black bars, median avidity of patients infected with a particular serotype.

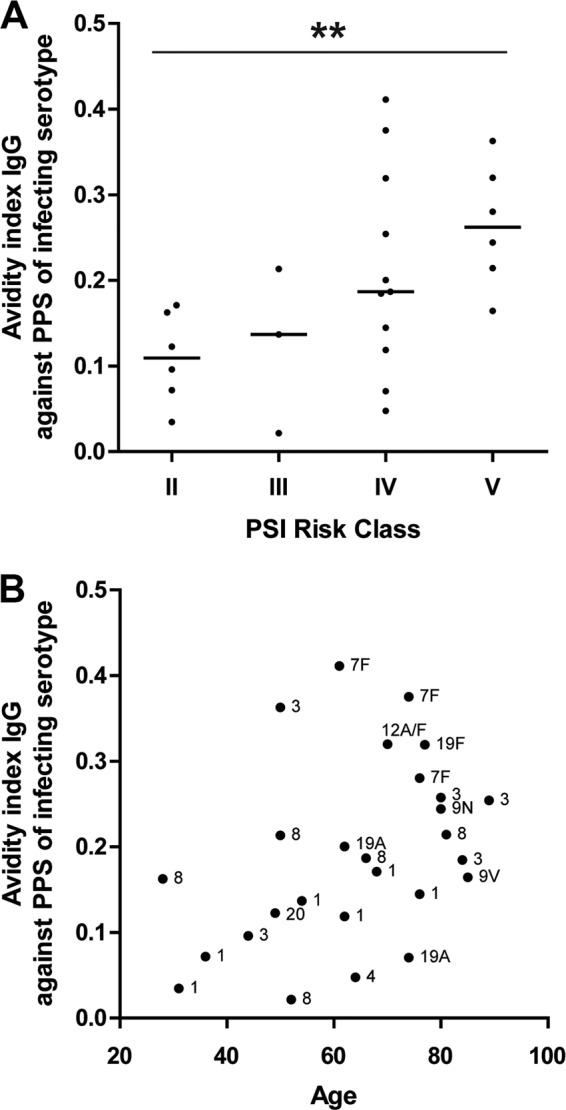

More-severe bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia according to pneumonia severity index (PSI) risk class was associated with increased IgG antibody avidities against the infecting serotype (Spearman r = 0.59, P = 0.0016; Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the IgG antibody avidity against the infecting serotype was positively correlated with age (Spearman r = 0.42, P = 0.028) in IPD patients (Fig. 3B). High-avidity antibodies result from the process of affinity maturation, which requires previous exposure to the pneumococcal polysaccharide involved. The higher avidity in older IPD patients than in younger IPD patients may be due to more extensive nasopharyngeal pneumococcal carriage. Although among the elderly pneumococcal carriage rates below 10% have been reported (15–17), other studies demonstrate increasing carriage rates with senior age (18, 19). Moreover, pneumococcal carriage was recently shown to be present in 33% of the Dutch elderly (20) and may still induce an anti-PPS memory response at this age (21). However, the higher avidity of anti-PPS antibodies in the elderly may also have been elicited in the initial phase of pneumococcal infection prior to disease.

FIG 3.

Avidity of anti-PPS antibodies in IPD patients increases with PSI risk class (A) and with age (B). Short horizontal lines in panel A indicate medians. Infecting serotypes against which IgG avidity is measured are displayed next to the corresponding dot in panel B. **, P < 0.01.

Antibody avidity may serve as a surrogate measure for other, more elaborate functional antibody tests such as in vitro opsonophagocytic killing or passive protection in mice (8, 14, 22). However, it is unknown how each of these assays actually correlates with protection from pneumococcal disease in adults. In addition, if there were a relationship, it could be serotype specific. To understand whether high-avidity anti-PPS antibodies are desirable in the elderly, their functional consequences should be studied in more detail in relation to acquisition and severity of disease in IPD patients of different ages infected with different serotypes.

In adult IPD patients, we observed an age-related increase in avidity of antibodies against the infecting serotype, indicating that the rise in IPD incidence with aging is not caused by a lack of avidity in anti-PPS antibodies. Therefore, among the elderly, flaws in other aspects of opsonophagocytosis, such as complement activation or intracellular killing, may play a more important role in the increased susceptibility to pneumococcal disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Mustafa Akkoyunlu from the U.S. FDA for providing us with the U.S. Reference Pneumococcal antiserum (007sp). We thank the staff of the participating Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital for facilitating the clinical sample and data collection. Furthermore, we thank Elles Simonetti for laboratory consultation and all volunteers who participated in the study.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 April 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2003. Pneumococcal vaccines. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 78(14):110–119 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller E, Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Slack MP, George RC. 2011. Herd immunity and serotype replacement 4 years after seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in England and Wales: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 11:760–768. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70090-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis (AMC/RIVM). 2013. Bacterial meningitis in the Netherlands; annual report 2012. Netherlands Reference Laboratory for Bacterial Meningitis (AMC/RIVM), Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Lynfield R, Reingold A, Cieslak PR, Pilishvili T, Jackson D, Facklam RR, Jorgensen JH, Schuchat A, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network 2003. Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1737–1746. 10.1056/NEJMoa022823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, Lewis E, Ray P, Hansen JR, Elvin L, Ensor KM, Hackell J, Siber G, Malinoski F, Madore D, Chang I, Kohberger R, Watson W, Austrian R, Edwards K. 2000. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. 2005. Recommendations for the production and control of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. WHO technical report series no. 927. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elberse KEM, de Greeff SC, Wattimena N, Chew W, Schot CS, van de Pol JE, van der Heide JGJ, van der Ende A, van der Klis FRM, Berbers GAM, Schouls LM. 2011. Seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against 13 vaccine Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in the Netherlands. Vaccine 29:1029–1035. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Usinger WR, Lucas AH. 1999. Avidity as a determinant of the protective efficacy of human antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides. Infect. Immun. 67:2366–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simell B, Vuorela A, Ekstrom N, Palmu A, Reunanen A, Meri S, Kayhty H, Vakevainen M. 2011. Aging reduces the functionality of anti-pneumococcal antibodies and the killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae by neutrophil phagocytosis. Vaccine 29:1929–1934. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubins JB, Puri AK, Loch J, Charboneau D, MacDonald R, Opstad N, Janoff EN. 1998. Magnitude, duration, quality, and function of pneumococcal vaccine responses in elderly adults. J. Infect. Dis. 178:431–440. 10.1086/515644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero-Steiner S, Musher DM, Cetron MS, Pais LB, Groover JE, Fiore AE, Plikaytis BD, Carlone GM. 1999. Reduction in functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae in vaccinated elderly individuals highly correlates with decreased IgG antibody avidity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:281–288. 10.1086/520200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Pneumococcal Serology Reference Laboratories. Training manual for enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for the quantitation of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype specific IgG (Pn PS ELISA) (007sp version). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.vaccine.uab.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spijkerman J, van Gils EJM, Veenhoven RH, Hak E, Yzerman EPF, van der Ende A, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, van den Dobbelsteen GPJM, Sanders EAM. 2011. Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae 3 years after start of vaccination program, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:584–591. 10.3201/eid1704.101115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musher DM, Phan HM, Watson DA, Baughn RE. 2000. Antibody to capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae at the time of hospital admission for pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 182:158–167. 10.1086/315697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridda I, Macintyre CR, Lindley R, McIntyre PB, Brown M, Oftadeh S, Sullivan J, Gilbert GL. 2010. Lack of pneumococcal carriage in the hospitalised elderly. Vaccine 28:3902–3904. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.03.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regev-Yochay G, Raz M, Dagan R, Porat N, Shainberg B, Pinco E, Keller N, Rubinstein E. 2004. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae by adults and children in community and family settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:632–639. 10.1086/381547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konno M, Baba S, Mikawa H, Hara K, Matsumoto F, Kaga K, Nishimura T, Kobayashi T, Furuya N, Moriyama H, Okamoto Y, Furukawa M, Yamanaka N, Matsushima T, Yoshizawa Y, Kohno S, Kobayashi K, Morikawa A, Koizumi S, Sunakawa K, Inoue M, Ubukata K. 2006. Study of upper respiratory tract bacterial flora: first report. Variations in upper respiratory tract bacterial flora in patients with acute upper respiratory tract infection and healthy subjects and variations by subject age. J. Infect. Chemother. 12:83–96. 10.1007/s10156-006-0433-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mackenzie GA, Leach AJ, Carapetis JR, Fisher J, Morris PS. 2010. Epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carriage of respiratory bacterial pathogens in children and adults: cross-sectional surveys in a population with high rates of pneumococcal disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:304. 10.1186/1471-2334-10-304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott JR, Millar EV, Lipsitch M, Moulton LH, Weatherholtz R, Perilla MJ, Jackson DM, Beall B, Craig MJ, Reid R, Santosham M, O'Brien KL. 2012. Impact of more than a decade of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use on carriage and invasive potential in Native American communities. J. Infect. Dis. 205:280–288. 10.1093/infdis/jir730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krone CL, Van Beek J, Wyllie AL, Rots NY, Oja A, Chu MLJN, Bruin JP, Bogaert D, Sanders EAM, Trzcinski K. 2014. High rates of Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage in saliva of elderly detected using molecular methods, poster P-056. 9th Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxendale HE, Davis Z, White HN, Spellerberg MB, Stevenson FK, Goldblatt D. 2000. Immunogenetic analysis of the immune response to pneumococcal polysaccharide. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:1214–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anttila M, Voutilainen M, Jantti V, Eskola J, Kayhty H. 1999. Contribution of serotype-specific IgG concentration, IgG subclasses and relative antibody avidity to opsonophagocytic activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 118:402–407. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01077.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]