Abstract

Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) serve as key negative-feedback regulators of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades. However, their roles and regulatory mechanisms in human fungal pathogens remain elusive. In this study, we characterized the functions of two PTPs, Ptp1 and Ptp2, in Cryptococcus neoformans, which causes fatal meningoencephalitis. PTP1 and PTP2 were found to be stress-inducible genes, which were controlled by the MAPK Hog1 and the transcription factor Atf1. Ptp2 suppressed the hyperphosphorylation of Hog1 and was involved in mediating vegetative growth, sexual differentiation, stress responses, antifungal drug resistance, and virulence factor regulation through the negative-feedback loop of the HOG pathway. In contrast, Ptp1 was not essential for Hog1 regulation, despite its Hog1-dependent induction. However, in the absence of Ptp2, Ptp1 served as a complementary PTP to control some stress responses. In differentiation, Ptp1 acted as a negative regulator, but in a Hog1- and Cpk1-independent manner. Additionally, Ptp1 and Ptp2 localized to the cytosol but were enriched in the nucleus during the stress response, affecting the transient nuclear localization of Hog1. Finally, Ptp1 and Ptp2 played minor and major roles, respectively, in the virulence of C. neoformans. Taken together, our data suggested that PTPs could be exploited as novel antifungal targets.

INTRODUCTION

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) govern a plethora of cellular processes in eukaryotes, such as proliferation, differentiation, programmed cell death, and stress responses (1–4). MAPKs are the final kinases in three-tiered signaling cascades; the T-X-Y motif in the activation loop contains conserved threonine (Thr) and tyrosine (Tyr) residues, which are phosphorylated for full activation of the MAPK by a dual-specificity MAPK kinase (MAPKK or MEK), which is in turn phosphorylated by a MAPKK kinase (MAPKKK or MEKK) (4, 5). In response to a variety of chemical and physical stresses, sensors/receptors and signal components are serially activated to sense environmental cues, relay or amplify signaling, and eventually activate the expression of MAPK target genes. During this process, negative-feedback regulation for controlling the duration and magnitude of signaling is as important as positive regulation because all signaling cascades must be properly tuned to avoid deleterious overactivation or constitutive activation and subsequently desensitized to recurrent external cues in a timely manner. However, the functions of negative regulators or inactivating signaling components in MAPK pathways are less well characterized than those of positive regulators.

In fungal pathogens, MAPK signaling pathways also play key roles in controlling fungal pathogenicity (6, 7). For example, in Cryptococcus neoformans, which causes often-fatal meningoencephalitis in humans (8, 9), three MAPKs, including Cpk1, Hog1, and Mpk1, have been found to play pivotal roles in diverse biological events (10, 11). Cpk1 and Mpk1 belong to the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) family of MAPKs, which harbor a T-E-Y motif, whereas Hog1 belongs to the p38 family of MAPKs, which harbor a T-G-Y motif. The MAPK Hog1 is a central component of the high osmolarity glycerol response (HOG) pathway, which consists of the multicomponent phosphorelay system and the Ssk2 MAPKKK-Pbs2 MAPKK-Hog1 MAPK module (12–16). The HOG pathway plays pleiotropic roles in C. neoformans by controlling the stress response, sexual differentiation, capsule and melanin production, and ergosterol biosynthesis (12–15). Perturbation of these MAPK pathways causes significant defects in differentiation, stress response, and/or virulence regulation.

Phosphatases are thought to be key negative-feedback regulators of MAPK pathways and can be categorized into three classes depending on the target phosphorylated amino acid residues of protein kinases (see reviews in references 17, 18, and 19): (i) protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), which dephosphorylate only phosphotyrosine; (ii) protein phosphatase type 2C (PP2Cs), which dephosphorylate phosphothreonine and phosphoserine; and (iii) dual-specificity phosphatases (DSPs), which are capable of dephosphorylating both phosphotyrosine and phosphothreonine. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, three PTPs (Ptp1 to 3), seven PP2Cs (Ptc1 to 7), and two DSPs (Msg5 and Sdp1) have been identified to date. Of the three yeast PTPs, Ptp2 and Ptp3 are involved in the dephosphorylation of several yeast MAPKs, whereas Ptp1 is dispensable for MAPK regulation (19). Ptp2 localizes mainly to the nucleus and dephosphorylates Hog1 and Mpk1 (involved in the cell wall integrity pathway) more efficiently than Ptp3. In contrast, Ptp3 localizes mainly to the cytoplasm and dephosphorylates Fus3 (involved in the pheromone response pathway) more preferentially than Ptp2 (20–23). Nevertheless, overexpression of PTP2 or PTP3 suppresses the lethality induced by hyperactivation of Hog1, such as mutation of SLN1, suggesting the redundant roles of these PTPs in Hog1 signaling (20, 21, 24). However, while accumulating evidence has supported the roles of MAPKs as negative-feedback regulators in organisms such as S. cerevisiae, their roles remain elusive in C. neoformans.

In human fungal pathogens, the roles of PTPs in MAPK regulation and fungal pathogenicity are poorly understood. Our prior transcriptome analysis of the HOG pathway revealed that two PTP-type phosphatase genes (CNAG_06064 and 05155), encoding yeast Ptp1 and Ptp2/3 orthologs, respectively, are differentially regulated by the HOG pathway and are therefore predicted to be strong candidates for the negative-feedback regulation of Hog1 (15). Based on these findings, we propose the following questions regarding cryptococcal PTP-type phosphatases. (i) Is the cryptococcal Ptp1 regulated by or required for the HOG pathway unlike yeast Ptp1? (ii) Does the cryptococcal Ptp2 have integrated functions of yeast Ptp2 and Ptp3, which have discrete and overlapping functions in S. cerevisiae? (iii) Are both Ptp1 and Ptp2 involved in regulation of the HOG pathway in C. neoformans? If so, do they play separate or redundant roles in controlling the HOG pathway? (iv) Are the other MAPK signaling cascades, including Mpk1 and Cpk1 MAPKs, subject to regulation by Ptp1 and Ptp2? In the current study, we sought to answer these questions through functional characterization of the PTP-type phosphatases Ptp1 and Ptp2 in C. neoformans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Animal care and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Yonsei University. The Yonsei University IACUC approved all of the vertebrate studies.

Strains and media.

Strains and primers used in this study are listed in Table 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material, respectively. C. neoformans strains were cultured and maintained on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium unless indicated otherwise. Niger seed medium for melanin production, agar-based Dulbecco's modified Eagle's (DME; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) medium for capsule production, and V8 medium, which contained 5% V8 juice (adjusted to pH 5; Campbell's Soup Co.), for mating assays were prepared as previously described (25). For urease assays, Christensen's agar medium was used (26).

TABLE 1.

C. neoformans strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotypea | Parent | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| H99 | MATα | 51 | |

| KN99a | MATa | 52 | |

| YSB42 | MATα cac1Δ::NAT-STM#159 | H99 | 25 |

| YSB119 | MATα aca1Δ::NAT-STM#43 ura5 ACA1-URA5 | YSB108 | 25 |

| YSB121 | MATa aca1Δ::NEO ura5 ACA1-URA5 | YSB108 | 25 |

| YSB64 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 | H99 | 13 |

| YSB242 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 ura5 URA5-PACT1:HOG1-FLAG-GFP | YSB114 | 13 |

| YSB253 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 HOG1T171A+Y173A-NEO | YSB64 | 13 |

| YSB308 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 HOG1K49S+K50N-NEO | YSB64 | 13 |

| YSB676 | MATα atf1Δ::NAT-STM#220 | H99 | 32 |

| YSB275 | MATα ptp2Δ::NAT-STM#184 | H99 | This study |

| YSB1704 | MATα ptp1Δ::NAT-STM#125 | H99 | This study |

| YSB1492 | MATa ptp2Δ::NEO | KN99a | This study |

| YSB1619 | MATa ptp1Δ::NAT-STM#125 | KN99a | This study |

| YSB2058 | MATα ptp1Δ::NAT-STM#125 ptp2Δ::NEO | YSB1704 | This study |

| YSB2635 | MATα ptp1Δ::NAT-STM#125 PTP1-NEO | YSB1704 | This study |

| YSB2195 | MATα ptp2Δ::NAT-STM#184 PTP2-NEO | YSB275 | This study |

| YSB1617 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 ptp2Δ::NEO | YSB64 | This study |

| YSB2586 | MATα PH3:PTP1-NEO | H99 | This study |

| YSB2572 | MATα PH3:PTP1-NEO ptp2Δ::NAT-STM#184 | YSB275 | This study |

| YSB2655 | MATα PH3:PTP1-NEO hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 | YSB64 | This study |

| YSB2569 | MATα PH3:PTP2-NEO | H99 | This study |

| YSB2590 | MATα PH3:PTP2-NEO ptp1Δ::NAT-STM#125 | YSB1704 | This study |

| YSB2658 | MATα PH3:PTP2-NEO hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 | YSB64 | This study |

| YSB2558 | MATα ptp1Δ::NEO | YSB242 | This study |

| YSB2563 | MATα ptp2Δ::NEO | YSB242 | This study |

| YSB2785 | MATα PTP1-GFP-NEO | YSB1704 | This study |

| YSB2891 | MATα PTP2-GFP-NEO | H99 | This study |

| YSB2563 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 ura5 URA5-PACT1:HOG1-FLAG-GFP ptp2Δ::NEO | YSB242 | This study |

| YSB2558 | MATα hog1Δ::NAT-STM#177 ura5 URA5-PACT1:HOG1-FLAG-GFP ptp1Δ::NEO | YSB242 | This study |

NAT-STM#, Natr marker with a unique signature tag. PACT1 and PH3 indicate ACT1 and H3 promoters, respectively.

Expression analysis by Northern blotting.

Each strain was grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 16 h and subcultured in fresh YPD medium at 30°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the cells reached approximately 1.0. For the zero time sample, a portion of the culture was sampled, and the remaining culture was added with an equal volume of YPD containing 2 M NaCl or treated with the indicated concentration of H2O2. During incubation, a portion of culture was sampled at indicated time points. Total RNA was isolated by the TRIzol reagent as previously described (15). Ten micrograms of total RNA in each strain was used for Northern blot analysis. Electrophoresis, membrane transfer, hybridization, and washing were performed by following the protocols previously described (27). Each probe for the PTP1 or PTP2 gene was amplified with gene-specific primers described in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Identification of 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR region of PTP1 and PTP2.

For identification of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and 3′ UTR region of PTP1 and PTP2, C. neoformans was grown in YPD medium for 16 h at 30°C, centrifuged at 4°C, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and lyophilized. The total RNA was isolated using Ribo-EX (GeneAll). By using the GeneRacer kit (Invitrogen), 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACEs) were performed by PCR, and subsequently, nested PCR was performed with the primers provided by manufacturers. All PCR products were cloned into a plasmid pTOP-V2 vector (Enzynomics) and sequenced for analyzing transcriptional start sites and terminator regions.

Construction of the ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutants and their complemented strains.

The PTP1 and PTP2 genes were deleted in C. neoformans var. grubii strains H99 and KN99a or other mutant backgrounds. The disruption cassettes were generated by using overlap PCR or split marker/double joint (DJ)-PCR strategies with a set of primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material (28, 29). The PCR-amplified gene disruption cassettes were introduced into each strain through the biolistic transformation method as previously described (28, 30). Transformants were selected on YPD medium containing nourseothricin or G418 for selection of the NAT (nourseothricin acetyltransferase gene) or NEO (neomycin/G418-resistant gene) marker, respectively, and were initially screened by diagnostic PCR with primer sets listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The correct genotypes of positive transformants were verified by Southern blotting as previously described (27).

To confirm the phenotypes manifested by the ptp1Δ and the ptp2Δ mutants, corresponding complemented strains were constructed as follows. To generate construct ptp1Δ::PTP1 complemented strains, a DNA fragment containing the 5′/3′ UTR and full-length open reading frame (ORF) of PTP1 was subcloned into plasmid pTOP-NEO, which contained the selectable NEO marker, resulting in plasmid pNEO-PTP1. To construct ptp2Δ::PTP2 complemented strains, a DNA fragment containing the full-length ORF and 5′/3′ UTRs of PTP2 was amplified using PCR with a set of primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, cloned into pTOP-V2 vector, and sequenced for verification, resulting in plasmid pTOP-PTP2. The NEO marker fragment with the HindIII restriction site was subcloned into the plasmid pTOP-PTP2 to generate plasmid pNEO-PTP2. These plasmids were linearized by restriction digestion with SspI for pNEO-PTP1 and MluI for pNEO-PTP2, which were in turn biolistically transformed into the ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutant strains, respectively. To confirm the targeted or ectopic reintegration of the wild-type (WT) gene, diagnostic PCR was performed.

Construction of PTP1 and PTP2 overexpression strains.

To replace the native PTP1 or PTP2 promoter with the histone H3 promoter, PH3:PTP1 (where the colon indicates a transcriptional fusion) and PH3:PTP2 replacement cassettes were constructed as diagrammed in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Primers B3655 and B5059 for the 5′-flanking region of PTP1 and primers B5060 and B3764 for the 5′ exon region of PTP1 were used in the first-round PCR. The 5′-flanking region of PTP2 was amplified with primers B4470 and B5061, and the 5′ exon region of PTP2 was amplified with primers B5062 and B3759 for the first-round PCR. The NEO marker was amplified with primers B4017 and B4018. Next, the PH3:PTP1 cassettes with the 5′ or 3′ region of the NEO split marker were amplified by DJ-PCR with primer pairs B3655/B1887 or B1886/B3764, respectively. The PH3:PTP2 cassettes were also amplified by DJ-PCR with primer pairs B4470/B1887 and B1886/B3759, respectively. Then, the PH3:PTP1 or PH3:PTP2 cassette was introduced into the wild-type strain H99 and the hog1Δ, ptp1Δ, or ptp2Δ mutant by biolistic transformation. Stable transformants selected on YPD medium containing G418 were screened by diagnostic PCR with primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material, and their correct genotypes were verified by Southern blotting. Probes for PTP1 and PTP2 were amplified by using PCR with primer pairs B3658/B3660 and B3758/B3759, respectively.

Construction of C. neoformans strains expressing PTP1-GFP and PTP2-GFP.

To construct PTP1-GFP strains, a DNA fragment that harbored the promoter and the coding regions of PTP1 was amplified through PCR with primer B5671 and B5672 containing NotI restriction sites and was cloned into pTOP-V2, resulting in plasmid pTOP-PTP1PE. After sequencing, the insert was subcloned into plasmid pNEO-GFPht containing NEO, GFP, and HOG1 terminator, resulting in plasmid pNEO-PTP1GFPht. This plasmid was linearized by SspI-digestion and biolistically transformed into the ptp1Δ mutants. The targeted reintegration of the PTP1-GFP allele into the native locus of PTP1 was confirmed by diagnostic PCR using primers B3655 and B3660.

To construct the PTP2-GFP strains, three PCR products were separately generated in the first round: (i) The 3′-exon region of PTP2 with primers B2902 and B5924, (ii) the 3′-flanking region of PTP2 with primers B5925 and J13647, and (iii) the GFP-HOG1ter-NEO fragment with primers B354 and B5665 by using the plasmid NEO-GFPht as a template. Next, two separate DJ-PCR products were generated: (i) a fusion fragment that contains the 3′ exon region of PTP2 and the 5′ split region of the GFP-HOG1ter-NEO fragment, with primer pair B2902/B1886, by mixing the first-round PCR products 1 and 2 as the templates; and (ii) a fusion fragment that contains the 3′ flanking region of PTP2 and the 3′ split region of the GFP-HOG1ter-NEO fragment, with primer pair B1887/J13647, by mixing the first-round PCR products 2 and 3 as the templates. Then, the two DJ-PCR products were combined and biolistically transformed into the H99 strain. The targeted insertion of the PTP2-GFP insertion cassette was confirmed with Southern blot analysis.

To study the roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in the cellular localization of Hog1, the PTP1 or PTP2 gene was deleted in a C. neoformans strain harboring pACT-HOG1fGFP (YSB242), which constitutively expresses a functional Hog1-GFP (13), as described above. To monitor the cellular localization of Ptp1-GFP, Ptp2-GFP, and Hog1-GFP, cells expressing PTP1-GFP, PTP2-GFP, or pACT-HOG1fGFP were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase in YPD medium and transferred to YPD liquid medium containing 1 M NaCl for the indicated times. For nuclear DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining, cells from each sample were fixed as previously described (31) and visualized by fluorescence microscope (Nikon eclipse Ti microscope).

Immunoblotting.

Each strain was grown in YPD medium at 30°C for 16 h and subcultured in fresh YPD medium at 30°C until it reached an OD600 of ∼0.8. A portion of culture was pelleted for the zero time sample. To the remaining culture, an equal volume of YPD medium containing 2 M NaCl was added for osmotic stress, and the mixture was further incubated for the indicated times. Proteins were extracted, and immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (13). To monitor Hog1 protein levels as loading controls, a primary rabbit polyclonal Hog1 antibody (SC-9079; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and a secondary anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody were used (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-2004). The immunoblot was developed using the ECL Western blotting detection system (ChemiDoc; Bio-Rad). To monitor phospho-Tyr and phospho-Tyr/Thr levels, antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (PY-20 antiphosphotyrosine mouse hybridoma; MPbio) and anti-phosphothreonine/tyrosine antibodies (Phospho-p38 MAP kinase [Thr180/Tyr182]; Cell signaling) were used, respectively.

Stress and antifungal drug sensitivity test.

Cells grown overnight at 30°C in YPD liquid medium were serially diluted (1 to 104 dilutions) with sterile H2O and spotted onto solid YPD medium containing the indicated concentration of stress-inducing agents and antifungal drugs, including fluconazole (FCZ), ketoconazole (KCZ), flucytosine, and fludioxonil. For oxidative stress sensitivity test, YPD medium containing the indicated concentrations of diamide, tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH), and H2O2 was used. For the osmosensitivity test, YP (no dextrose) or YPD medium containing the indicated concentration of NaCl or KCl was prepared. Hydroxyurea (HU) and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) were used for genotoxic stress, and CdSO4 was used for heavy metal stress sensitivity assays, respectively. Plates were incubated at 30°C and photographed for 2 to 4 days.

Mating, agar adherence, and invasion assay.

Each mating type α and a cell was incubated in 2 ml liquid YPD medium overnight at 30°C. After cell counting, the concentration of cells was adjusted to 107 cells/ml with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For mating, equal volumes of MATa and MATα cells were mixed, and 5 μl of the mixture was spotted onto V8 solid medium and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 to 2 weeks. The spots were monitored weekly and photographed (Olympus BX51 microscope). Cell fusion efficiency and pheromone gene expression were measured as previously described (25, 27). Adherence and invasion were assessed as previously described (32).

Capsule, melanin, and urease production assays.

Each C. neoformans strain was incubated for 16 h at 30°C in YPD liquid medium, spotted onto DME solid medium, and further incubated for 2 days at 37°C. After incubation, capsules were stained by India ink (Bactidrop; Remel) and visualized by using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a Spot insight digital camera. For quantitative measurement of capsules, a packed cell volume was measured by using hematocrit capillary tubes as described previously (27). For the melanin production assay, each cell was spotted onto niger seed medium containing 0.1% or 0.5% glucose and was incubated for up to 7 days at 30°C or 37°C. Melanin production was monitored and photographed daily. For urease activity, each strain was incubated in 2 ml liquid YPD medium overnight at 30°C. After cell counting, equal concentrations of each cell (1 × 107 cells/ml) were spotted onto Christensen's agar medium and incubated for up to 7 days at 30°C. Urea is converted into ammonia by urease secreted in each Cryptococcus strain, thereby increasing the pH, which changes in color from yellow to red-violet by phenol red, as a pH indicator, in Christensen's agar medium. Urease production was monitored and photographed daily.

Virulence and fungal burden assays.

For infection, the wild-type strain (H99) and ptp1Δ (YSB1714), ptp2Δ (YSB275), and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ (YSB2058) mutants were cultured overnight in YPD liquid medium at 30°C. The cultured cells were pelleted, washed three times in PBS, and resuspended in sterile PBS at a concentration of 107 cells/ml. Seven-week-old female A/J mice (10 mice per group) anesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) were infected intranasally with 5 × 105 cells in 50 μl PBS. Mice were housed with free access to food and water under a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle. After infection, the concentration of each initial inoculum was confirmed by plating serial dilutions onto the YPD solid medium and counting CFU. Mice were daily checked for signs of morbidity (extension of the cerebral portion of the cranium, abnormal gait, paralysis, seizures, convulsion, or coma) and their body weight. Mice exhibiting signs of morbidity or a significant weight loss were sacrificed with an overdose of Avertin. The log rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed to analyze differences between survival curves, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

To determine fungal burden, 7-week-old female A/J mice (n = 3 for each strain) were intranasally infected with 5 × 105 cells of the wild-type strain (H99), ptp1Δ (YSB1714), ptp2Δ (YSB275), ptp1Δ ptp2Δ (YSB2058) mutants, or ptp2::PTP2 (YSB2195). C. neoformans-infected mice were dissected at 15 days postinfection. Lungs and brains were harvested from the mice and then homogenized in 3 ml PBS by grinding. To determine CFU per gram of lung or brain, tissue homogenates were serially diluted into YPD medium containing chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) and cells were incubated for 3 days at 30°C. The remaining tissue homogenates were dried to measure organ weight in a dry oven. The Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test was performed to analyze the significance of differences in fungal burden, and P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences of PTP1 and PTP2 were registered in GenBank (accession numbers JX975719 and JN833628, respectively).

RESULTS

Ptp1 and Ptp2 are negative-feedback regulators of the HOG pathway in C. neoformans.

Our microarray analysis of the HOG pathway uncovered two PTP-encoding genes, CNAG_06064 and CNAG_05155, as potential negative regulators of the MAPK Hog1 (15). For further structural and functional analyses, we first elucidated the genomic DNA structures of PTP1 and PTP2 by performing 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and analyzing the coding sequence of the whole open reading frame. CNAG_06064 consisted of four exons and three introns and was predicted to encode a 282-amino-acid protein, with a 46-bp 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and a 48-bp 3′ UTR. CNAG_05155 consisted of five exons and four introns and was predicted to encode a 1,211-amino-acid protein, with a 46-bp 5′ UTR and a 401-bp 3′ UTR (GenBank accession no. JX975719 for PTP1 and JN833628 for PTP2). In silico analysis of fungal phosphatases and protein domain analysis by Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk) revealed that CNAG_06064 was more homologous to ScPtp1, CaPtp1, and SpPyp3 whereas CNAG_05155 was more homologous to ScPtp3, SpPyp1/2, and CaPtp3 (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). In addition, phylogenetic analysis showed that ScPtp2 was separately classified from other fungal PTP groups (Fig. S1A). The predicted proteins encoded by CNAG_06064 and CNAG_05155 contained a typical PTP signature sequence [(I/V)HCXAGXGR(S/T)G], which is conserved among all PTPs (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). In particular, the essential Cys residue was conserved in both CNAG_06064 and CNAG_05155. Although S. cerevisiae Ptp2 and Ptp3 contain a second cysteine residue (HCXAGCXR), unlike other PTPs, this second Cys residue was not conserved in CNAG_06064 or CNAG_05155 (Fig. S1B). Considering these structural features, CNAG_06064 and CNAG_05155 were named PTP1 and PTP2, respectively, because C. neoformans contained only two PTP-like genes in its genome.

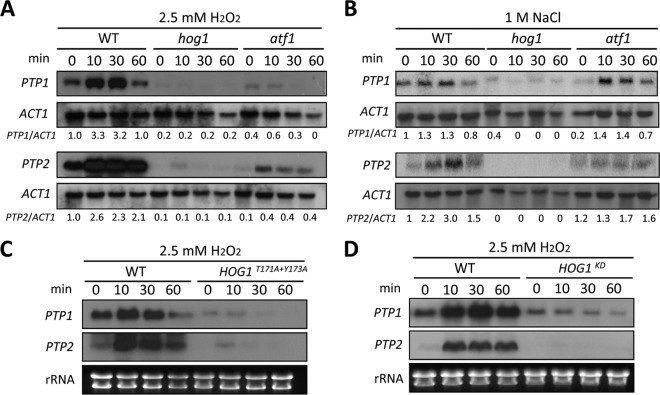

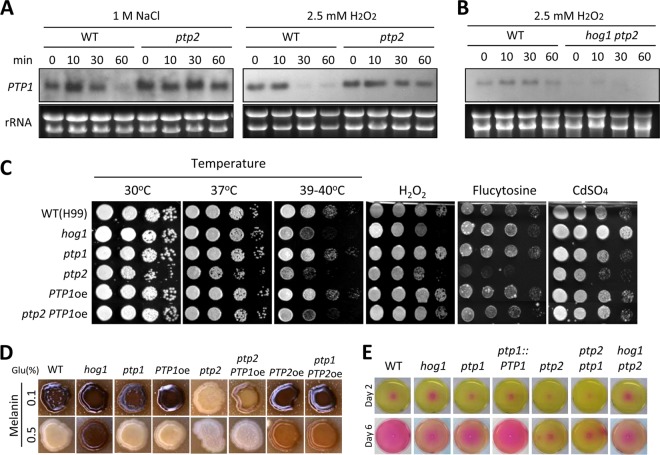

Next, we examined whether the expression of PTP1 and PTP2 was differentially modulated in a Hog1-dependent manner in response to environmental stresses. In response to oxidative stress (2.5 mM H2O2), the expression of both PTP genes was induced in a similar pattern (Fig. 1A). Expression of both PTP1 and PTP2 was rapidly induced after 10 min of exposure to H2O2 in wild-type cells. However, in hog1Δ mutants, both basal and induced expression levels of PTP1 and PTP2 were dramatically decreased, suggesting that Hog1 was a key regulator of PTP1 and PTP2 expression (Fig. 1A). The expression levels of PTP1 and PTP2 were also induced by osmotic stress (1 M NaCl), albeit to a lesser extent than those induced by oxidative stress (Fig. 1B). Similar to the results observed after oxidative stress, osmotic stress led to significant reductions in both basal and induced levels of PTP1 and PTP2 in the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 1B). However, the residual induction of PTP2 in the hog1Δ mutant in response to H2O2 (Fig. 1A) indicated that PTP2 may also be under the control of other signaling pathway(s).

FIG 1.

PTP1 and PTP2 are Hog1-dependent stress-inducible genes. Northern blot analyses were performed using the total RNA isolated from each strain [WT (strain H99) and hog1 (YSB64), atf1 (YSB676), HOG1T171A+Y173A (YSB253), and HOG1K49S+K50N (YSB308) mutant strains], which was grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C in YPD medium and exposed to 2.5 mM H2O2 (A, C, and D) or 1 M NaCl (B). Each membrane was hybridized with PTP1- or PTP2-specific probes, washed, and developed. The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with the ACT1-specific probe. (A and B) The relative PTP1 or PTP2 expression levels were quantitatively measured through phosphorimager analysis after normalization with ACT1 expression levels. Each value at indicated time points represents expression levels relative to the levels at the zero time point of the wild-type strain. (C and D) Each membrane was hybridized with the PTP1-specific probe, washed, and developed. The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with the PTP2-specific probe. Ethidium bromide staining results of rRNA were used as loading controls.

Previously, we had shown that mutation of either T171A or Y173A completely abolishes the Hog1 MAPK activity, similar to the effects of K49S and K50N mutations in the Hog1 kinase domain (HOG1KD) (13). Therefore, we next examined whether regulation of PTP1 and PTP2 expression depended on the dual phosphorylation of the T-G-Y motif (where boldface indicates phosphorylation) and the kinase activity in Hog1. In both HOG1T171A+Y173A (Fig. 1C) and HOG1KD mutants (Fig. 1D), basal and induced PTP1 and PTP2 expression levels were greatly reduced, similar to the results observed in the hog1Δ mutant. These data strongly suggested that both the dual Thr/Tyr phosphorylation and the kinase activity of Hog1 were required for the regulation of PTP1 and PTP2 expression.

We then sought to determine which transcription factor downstream of Hog1 controlled the expression of PTP genes. Our previous work had implicated the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain-containing Atf1 transcription factor as a potential candidate regulated by Hog1 in C. neoformans (our unpublished results). Therefore, we next examined PTP expression levels among the wild-type strain, the atf1Δ mutant, and the hog1Δ mutants. In the atf1Δ mutant, both basal and oxidative-stress-induced levels of PTP1 and PTP2 genes were reduced, albeit to a lesser extent than in the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 1A). In contrast, Atf1 appeared to be less involved in regulating the expression of PTP1 and PTP2 in response to osmotic stress, although induction of PTP2 was reduced by 50% in the atf1Δ mutant (Fig. 1B). These data corroborated previous findings that Atf1 is involved mainly in the oxidative stress response, not the osmotic stress response (32, 33). Taken together, our data supported that PTP1 and PTP2 were stress-inducible PTPs, whose basal and induced expressions were both primarily regulated by Hog1, partly through the transcription factor Atf1 in C. neoformans.

Ptp2 was required for vegetative cell growth by suppressing overactivation of Hog1.

In S. cerevisiae, Ptp2 and Ptp3 play major and minor roles, respectively, in regulating Hog1, whereas Ptp1 is not involved in MAPK regulation. Therefore, Tyr phosphorylation levels of Hog1 are significantly increased in the ptp2Δ mutant, but not in the ptp3Δ mutant, and are further enhanced in the ptp2Δ ptp3Δ mutant in response to osmotic stress (20, 21). However, our expression analysis implied that both Ptp1 and Ptp2 might act as negative-feedback regulators in controlling Hog1. To test this hypothesis, we characterized the functions of Ptp1 and Ptp2 through a gene knockout study. For this purpose, more than two independent ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutants and their complemented strains were constructed in serotype A MATα H99 strain and MATa KN99 strain. Given the possibility that Ptp1 and Ptp2 have redundant functions, independent ptp1Δ ptp2Δ double mutants were also constructed (Table 1).

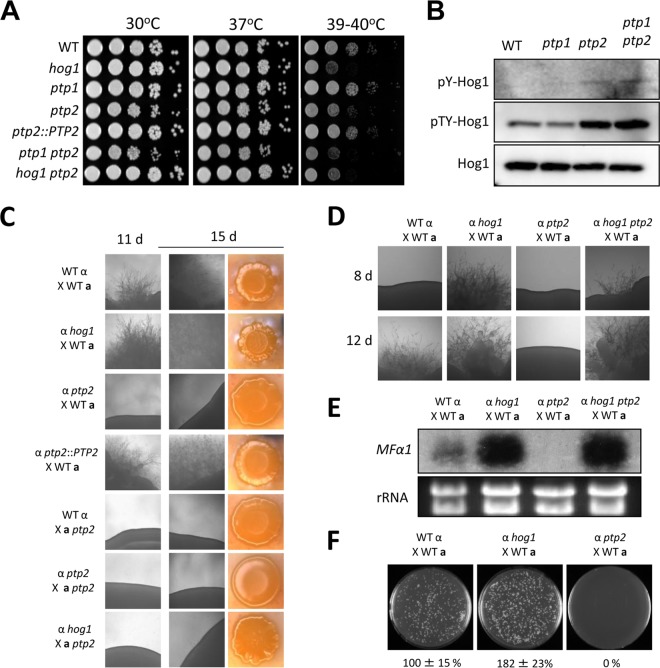

Phenotypic analyses revealed that Ptp2, but not Ptp1, was a major PTP in regulator of the Hog1 MAPK. Disruption of PTP2, but not PTP1, affected the normal growth of C. neoformans (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the growth defects of the ptp2Δ mutant appeared to be even more severe at high temperatures (39 to 40°C), whereas the ptp1Δ mutant did not show any temperature sensitivity, and reintegration of PTP2 abolished the growth defects in the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 2A), confirming these results. The ptp1Δ ptp2Δ double mutant was as defective in growth as the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 2A). Additionally, we further analyzed the growth defects of the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants in growth assays by using liquid YPD medium (data not shown). ptp2Δ mutants not only grew more slowly but also entered the stationary phase earlier than the wild-type strain.

FIG 2.

Ptp2 is required for the growth and differentiation of C. neoformans as a negative-feedback regulator of Hog1. (A) Growth of ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutants at diverse temperatures. Each strain (WT [strain H99] and hog1, ptp1 [YSB1704], ptp2 [YSB275], ptp2::PTP2 [YSB2195], ptp1 ptp2 [YSB2058], and hog1 ptp2 [YSB1617] strains) was grown overnight at 30°C in liquid YPD medium, 10-fold serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD agar medium. Cells were incubated at 30°C, 37°C, and 39 to 40°C for 4 days and photographed. (B) The WT strain (H99) and ptp1, ptp2, and ptp1 ptp2 mutants were grown to mid-logarithmic phase, and total protein extracts were prepared for immunoblot analysis. The anti-pY-Hog1 and anti-pTY-Hog1 antibodies were used for monitoring phosphotyrosine and phosphotyrosine/threonine levels, respectively. The same blots were stripped and then reprobed with polyclonal anti-Hog1 antibody for loading controls. (C) Ptp2 was essential for the sexual differentiation in C. neoformans. Serotype A MATα and MATa strains were cocultured on V8 medium (pH 5) for 15 days at room temperature in the dark. The images were photographed after 11 and 15 days. (D) Ptp2 modulated mating by negatively controlling Hog1. Each indicated α strain was cocultured with KN99a on V8 medium in the dark at room temperature and photographed after 8 and 12 days. (E) The deletion of PTP2 resulted in decreased levels of a pheromone gene, MFα1. Northern blot analysis for measuring the expression of MFα1 was performed with total RNA isolated from the coculture of the indicated strains, which were grown for 24 h under mating conditions. (F) Ptp2 was required for cell-cell fusion during mating response. Cell fusion efficiency was calculated relative to the control strains (WT α [YSB119] × WT a [YSB121]).

The finding that PTP2, whose expression was controlled by Hog1, was required for the vegetative growth of C. neoformans implied that Ptp2 may be induced to suppress the hyperactivation of Hog1. In addition, we had previously shown that hyperactivation of the HOG pathway by either fludioxonil treatment or deletion of YPD1 causes severe growth defects in C. neoformans (16, 34). To test whether the role of Ptp2 in the growth of C. neoformans is mediated through Hog1, we constructed a ptp2Δ hog1Δ double deletion mutant (Table 1) and examined its growth defects. Interestingly, we found that the growth defects of the ptp2Δ mutant were significantly restored by deletion of HOG1 at temperatures ranging from 30°C to 37°C (Fig. 2A). At high temperatures (39 to 40°C), however, the ptp2Δ hog1Δ mutant exhibited levels of thermosensitivity similar to those of the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 2A), indicating that both overactivation and inhibition of the HOG pathway could perturb thermoresistance in C. neoformans.

These data strongly suggested that increased Tyr phosphorylation of Hog1 by deletion of PTP2 hyperactivated Hog1 and caused growth defects in C. neoformans. As other kinases upstream of Hog1, such as Pbs2 and Ssk2 (Ser/Thr kinases) and Tco1/2 and Ssk1 (His kinases), do not require any phosphorylated Tyr residues for their activation, Hog1 is likely to be the major target of Ptp2 in the HOG pathway. Nevertheless, this was a rather unexpected finding because Hog1 activation requires dual phosphorylation on both Thr and Tyr residues in C. neoformans (13). In S. cerevisiae, deletion of any PTP gene does not cause growth defects alone but causes synthetic growth lethality with deletion of PP2C genes, such as PTC1 (35). Therefore, we hypothesized that the increased tyrosine (Y173) phosphorylation levels of Hog1 (pY-Hog1) by deletion of PTP2 may lead to a subsequent increase in the threonine (T171) phosphorylation levels of Hog1 (pT-Hog1). To investigate this, we examined pY and pTY levels of Hog1 in the ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutants. In support of the expression and growth analysis data described above, the levels of pY-Hog1 appeared to be increased in both the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants, but not in the ptp1Δ mutant (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, signals from immunoblots with anti-pY-Hog1 antibodies were very weak, even in ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants, implying that the amount of Hog1 harboring only Tyr phosphorylation was likely too small to be detected. Surprisingly, pTY-Hog1 levels, analyzed using immunoblotting with pTY-antibodies, were significantly increased in both the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants, but not in the ptp1Δ mutant (Fig. 2B). However, we could not rule out the possibility that the increased pTY-Hog1 signal in the ptp2Δ mutants may just have resulted from the increased pY-Hog1 signal without the increased pT-Hog1 signal. Taken together, our data demonstrated that Ptp2 had a major role in suppressing the hyperphosphorylation and hyperactivation of Hog1 and promoting the optimal vegetative growth of C. neoformans. In contrast, Ptp1 was largely dispensable for Hog1 regulation, despite the Hog1-dependent regulation of PTP1.

Ptp2 negatively regulated Hog1 during sexual differentiation and virulence factor production.

Increased phosphorylation of Hog1 by deletion of PTP2 may alter the normal behavior of Hog1 positively or negatively, which may affect HOG-related phenotypes. Besides its roles in vegetative growth, the HOG pathway functions to control sexual differentiation and virulence factor production in C. neoformans (13). Based on prior observations, we hypothesized that deletion of PTP2 may also affect the mating efficiency and virulence factor production in C. neoformans by altering Hog1 phosphorylation levels.

In contrast to the hog1Δ mutant, which was more proficient in mating than the wild-type strain, as previously reported (13), the α ptp2Δ mutant exhibited severe mating defects, even in unilateral crossing with opposite mating partners of wild-type strains (KN99a; Fig. 2C). Similarly, the a ptp2Δ mutant also showed a complete lack of mating in unilateral crossing with the H99 strain or the α ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the a ptp2Δ mutant was also not able to mate with the α hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 2C). However, deletion of HOG1 almost completely restored normal mating efficiency in the α ptp2Δ mutant and enhanced mating efficiency, as was observed with the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these data together strongly suggested that Ptp2 promoted mating by negatively controlling Hog1.

To further support these data, we compared cell fusion efficiency and pheromone production levels of the ptp2Δ mutant with those of wild-type and hog1Δ mutant strains. Upon mating with KN99a, the α ptp2Δ mutant was completely defective in pheromone production and subsequent cell-to-cell fusion whereas the α hog1Δ mutant exhibited augmentation of both pheromone production (Fig. 2E) and cell fusion process (Fig. 2F). The α ptp2Δ hog1Δ double mutant showed enhanced pheromone production, similar to the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 2E), verifying that Ptp2 positively regulated the mating of C. neoformans by negatively controlling Hog1. In contrast, the ptp1Δ mutant did not show any discernible defects in unilateral or bilateral crossing events (data not shown).

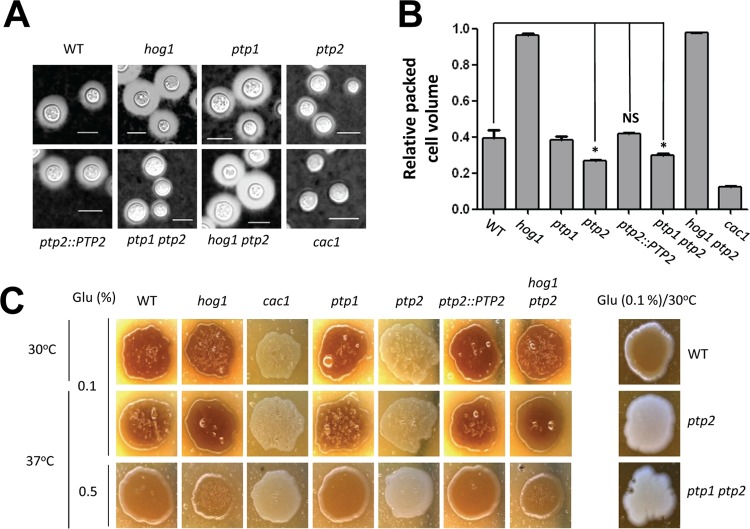

In capsule and melanin production, the ptp2Δ mutant, but not the ptp1Δ mutant, showed phenotypes opposite to those of the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 3). In contrast to the hog1Δ mutant, which exhibited enhanced capsule size, the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants, but not the ptp1Δ mutant, exhibited reduced capsule sizes (Fig. 3A and B). Similarly, both the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants produced markedly reduced levels of melanin compared to those of the wild-type strain, which were almost equivalent to those of the cac1Δ mutant in the cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling pathway (Fig. 3C). Both capsule and melanin production levels were restored in the ptp2Δ hog1Δ double mutant to levels comparable to those of the hog1Δ mutant, strongly suggesting that Ptp2 controlled capsule and melanin production through Hog1. Taken together, our data suggested that Ptp2 negatively regulated Hog1 during sexual differentiation and production of two virulence factors, capsule and melanin, in C. neoformans.

FIG 3.

Ptp2 negatively regulates virulence factor production in C. neoformans through modulation of Hog1. (A and B) Each strain (WT [strain H99] and hog1, ptp1, ptp2, ptp2::PTP2, ptp1 ptp2, hog1 ptp2, cac1 [YSB42] strains) was spotted onto DME medium for capsule production at 37°C for 2 days. Cells were scraped, resuspended in PBS, and visualized by India ink staining. The relative packed cell volume was measured by calculating the ratio of the length of a packed cell volume phase to the length of a total volume phase. Bars, 10 μm. *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant (P > 0.05). (C) Cells were spotted onto niger seed medium containing 0.1% or 0.5% glucose and incubated at 30°C or 37°C. Melanin production was monitored and photographed daily.

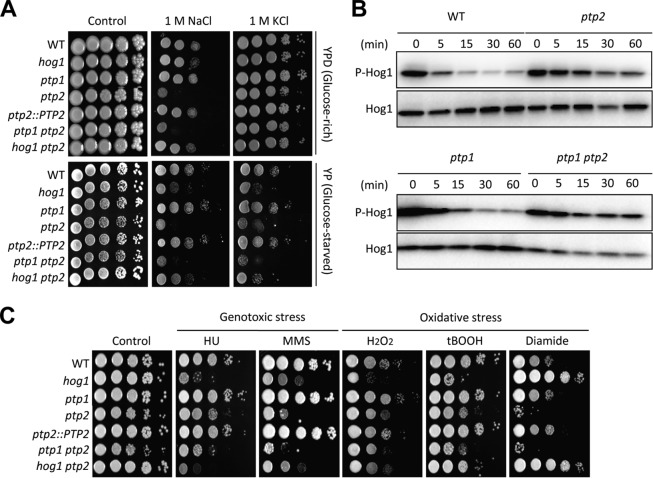

Disruption of the negative-feedback loop of the HOG pathway by deletion of Ptp2 differentially affected the environmental stress response and adaptation.

Next, we assessed the effects of PTP1 and PTP2 deletion on the stress response and adaptation, which are mediated by the HOG pathway in C. neoformans (13–15). The ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants showed differential susceptibilities to diverse stresses, whereas the ptp1Δ mutant was almost as resistant as the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A and C). Surprisingly, however, deletion of PTP2 often resulted in stress phenotypes equivalent to those of the hog1Δ mutant. For instance, the ptp2Δ mutant showed even higher osmosensitivity than the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 4A) and sustained phosphorylation of Hog1 during osmotic stress, unlike the wild-type strain, which exhibited dephosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the increased Hog1 phosphorylation observed in the ptp2Δ mutant was further enhanced during osmotic stress response by deletion of PTP1, suggesting that Ptp1 may play a role in Hog1 regulation (Fig. 4B). Moreover, deletion of HOG1 restored the osmoresistance of the ptp2Δ mutant to the degree observed in the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 4A), supporting our hypothesis that both positive and negative regulation of the HOG pathway could be critical for maintaining the osmotic balance.

FIG 4.

The balanced regulation of the HOG pathway is critical for environmental stress response and adaptation in C. neoformans. (A and C) Each strain was grown for 16 h at 30°C in liquid YPD medium, 10-fold serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD (glucose-rich) or YP (glucose-starved) medium containing the indicated concentration of KCl or NaCl. (B) WT (strain H99) and ptp1, ptp2, and ptp1 ptp2 mutant strains were grown to mid-logarithmic phase and exposed to 1 M NaCl in YPD medium for the indicated time, and then total proteins were extracted for immunoblot analysis. The Hog1 phosphorylation levels were monitored using anti-dually phosphorylated p38 antibody (P-Hog1; number 4511; Cell Signaling). The same blots were stripped and then reprobed with polyclonal anti-Hog1 antibody for the loading control (Hog1). (C) Each strain was cultured for 16 h at 30°C in liquid YPD medium, 10-fold serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD containing genotoxic stress inducers (110 mM hydroxyurea [HU], 0.04% methyl methanesulfonate [MMS]) or oxidative stress agents (3.5 mM H2O2, 0.65 mM tert-butyl hydroperoxide [tBOOH], 2 mM diamide).

A similar phenomenon was observed in the genotoxic stress response (Fig. 4C). As was found for the hog1Δ mutant, the ptp2Δ mutant showed higher susceptibility to two genotoxic agents, hydroxyurea (HU) and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) (Fig. 4C). In all cases, the ptp2Δ hog1Δ mutant was similar to the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 4C). Deletion of PTP2 also enhanced susceptibility to certain oxidative stress agents, such as diamide (a thiol-specific oxidant) and tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBOOH). In response to diamide in particularly, against which the hog1Δ mutant exhibited increased resistance, the ptp2Δ mutant showed hypersensitivity (Fig. 4C). These oxidative stress patterns of the ptp2Δ mutant were converted to those of the hog1Δ mutant by deletion of HOG1 (Fig. 4C), indicating that Hog1 mediates the role of Ptp2 in response to diamide.

In summary, abnormal overactivation of the HOG pathway appeared to perturb the normal environmental stress response and adaptation in C. neoformans, similar to pathway inhibition, suggesting that balanced and orchestrated regulation of the HOG pathway by coordinated regulation of Hog1 and Ptp2 is critical for stress management.

Roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in antifungal drug susceptibilities.

The HOG pathway modulates susceptibility to multiple classes of antifungal agents: (i) the HOG pathway promotes susceptibility to a member of the phenylpyrrole class of fungicide, fludioxonil, by triggering intracellular glycerol synthesis and cell swelling in C. neoformans (34); (ii) the HOG pathway affects azole and polyene drug susceptibility by repressing the expression of ERG11 (15); and (iii) the HOG pathway is involved in flucytosine susceptibility (36). Therefore, we next investigated the effects of changes in the negative regulation of the HOG pathway by PTP2 on antifungal drug susceptibility.

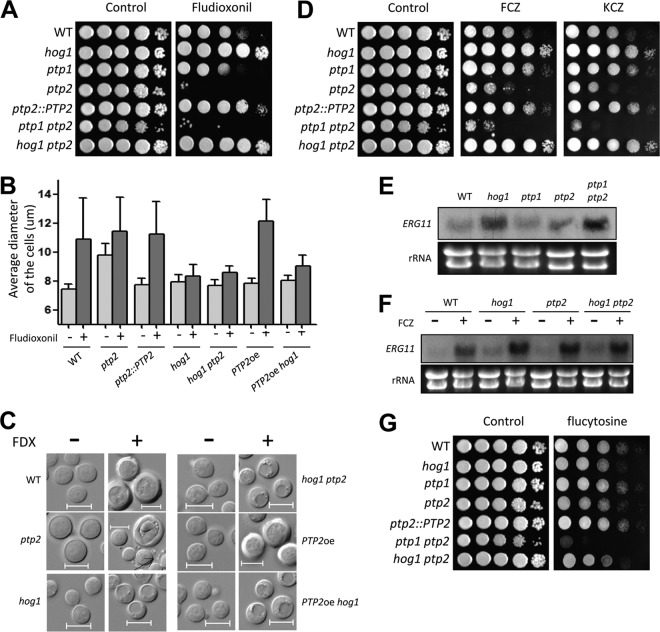

The ptp2Δ mutant was much more susceptible to fludioxonil than the wild-type strain, while the hog1Δ mutant was resistant to fludioxonil (Fig. 5A). This increased susceptibility appeared to result from hyperactivation of Hog1, as the ptp2Δ hog1Δ mutant was as resistant to fludioxonil as the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 5A). Moreover, the ptp2Δ mutant exhibited swollen cell size, even under unstressed conditions (Fig. 5B and C), which might be related to defective vegetative growth, as previously shown (Fig. 2A). In response to fludioxonil, the ptp2Δ cells were further swollen to the levels of fludioxonil-treated wild-type cells. Notably, in fludioxonil-treated ptp2Δ cells, cell debris-like particles were frequently found around the cells (see the regions indicated by arrows in Fig. 5C).

FIG 5.

Roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in antifungal drug susceptibilities of C. neoformans. (A, D, and G) Each strain was grown for 16 h at 30°C in liquid YPD medium, 10-fold serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD medium containing 2 μg/ml fludioxonil (A), 14 μg/ml fluconazole (D), 0.03 μg/ml ketoconazole (D), or 400 μg/ml flucytosine (G). (B) Each strain (WT [strain H99] and hog1, ptp2, ptp2::PTP2, hog1 ptp2, PTP2oe [YSB2569] and PTP2oe hog1 [YSB2658] strains), which were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase, was reincubated in YPD medium with or without fludioxonil (10 μg/ml) at 30°C for 48 h with shaking and then photographed by using a Spot insight digital camera. The cell diameter of each strain was quantitatively measured by using the Spot Imaging solutions. The y axis indicates the average diameter of cells. A total of 100 cells per strain were measured. (C) Representative pictures of fludioxonil (FDX)-treated or nontreated cells. Bars, 10 μm. A black arrow indicates cell debris-like particles. (E and F) Northern blot analysis results for the basal and azole-induced expression levels of ERG11 in ptp1Δ and ptp2Δ mutants. To determine the basal expression levels of ERG11, each indicated strain was grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C in YPD liquid medium and total RNA was extracted (E). These cells were further treated with 10 μg/ml fluconazole for 90 min and were subjected to total RNA isolation (F). The Northern blot membrane was hybridized with the ERG11-specific probe, washed, and developed. Ethidium bromide staining results of rRNA were used as loading controls.

Ptp2 also appeared to be involved in azole susceptibility in a manner opposite to that of Hog1. In contrast to the hog1Δ mutant, which showed fluconazole resistance, the ptp2Δ mutant, but not the ptp1Δ mutant, exhibited enhanced susceptibility to fluconazole (Fig. 5A). Previously, we have shown that deletion of HOG1 increases basal ERG11 expression levels but not fluconazole-induced ERG11 expression levels (15, 37). However, deletion of PTP2 did not significantly affect either basal or induced expression levels of ERG11 upon fluconazole treatment (Fig. 5E and F). In fact, basal ERG11 expression levels were even higher in the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutant than the wild-type strain (Fig. 5E), although the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutant was highly susceptible to azole drugs. Interestingly, the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutant was more susceptible to azole drugs than the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 5D), indicating that Ptp1 may play a minor role in azole resistance. These data suggested that increased azole susceptibility by PTP2 and PTP1 deletion did not result from altered ERG11 expression. Nevertheless, the fact that the hog1Δ ptp2Δ mutant was as resistant to azole drugs as the hog1Δ mutant suggested that Ptp2 promoted azole resistance by controlling Hog1 without involvement in ERG11 expression.

Unlike what was observed in fludioxonil and azole drug susceptibility, both ptp2Δ and hog1Δ mutants exhibited increased susceptibility to flucytosine (Fig. 5G). Notably, the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ double mutant was even more susceptible to flucytosine than the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 5E), suggesting that Ptp1 and Ptp2 play redundant roles in flucytosine resistance. These data might be correlated to the fact that Ptp1 played a role in the genotoxic stress response, as the antifungal activity of flucytosine (5FC) results from its ability to inhibit DNA/RNA synthesis (38).

Taken together, our data demonstrated that Ptp1 and Ptp2 played minor and major roles in susceptibility to multiple classes of antifungal drugs.

Ptp2 may have targets other than Hog1 in C. neoformans.

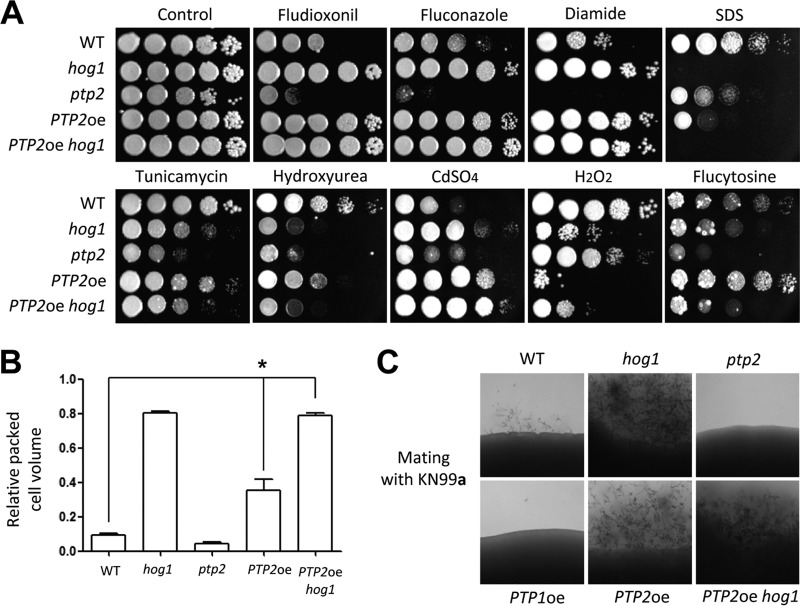

To examine whether Ptp2 may mediate other MAPKs and Tyr-phosphorylated kinases, we examined phenotypes generated by PTP2 overexpression by replacing the native PTP2 promoter with the constitutively active H3 promoter because deletion of PTP2 genes may not fully hyperactivate Hog1, which can be activated by dual Thr/Tyr phosphorylation. In the majority of phenotypes examined, we found that PTP2 overexpression (PTP2oe) yielded phenotypes similar to those observed for the hog1Δ mutant. For instance, the PTP2oe strain was as resistant to fludioxonil, fluconazole, and diamide as the hog1Δ mutant, while the ptp2Δ mutant exhibited hypersensitivity to these compounds (Fig. 6A). In response to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), tunicamycin (TM; an endoplasmic reticulum [ER] stress agent), and HU, the PTP2oe strain also showed hypersensitivity, albeit to a lesser extent than that observed for the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, overexpression of PTP2 increased the production of capsule and melanin to the same degree as the hog1Δ mutation (Fig. 6B and Fig. 7D). Overexpression of PTP2 also increased mating efficiency, as did the hog1Δ mutation (Fig. 6C). In all of these phenotypes, the PTP2oe hog1Δ mutant was phenotypically identical to the hog1Δ mutant, further indicating that the effects of PTP2 overexpression were manifested mainly through negative regulation of Hog1.

FIG 6.

Ptp2 may have Hog1-independent targets. (A) Each strain (WT [strain H99] and hog1, ptp2, PTP2oe, and PTP2oe hog1 mutant strains) was grown overnight at 30°C in liquid YPD medium, 10-fold serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD medium containing fludioxonil (1.5 μg/ml), fluconazole (14 μg/ml), diamide (3 mM), SDS (0.04%), tunicamycin (0.3 μg/ml), hydroxyurea (110 mM), CdSO4 (27.5 μM), H2O2 (3.5 mM), and flucytosine (600 μg/ml). Cells were incubated at 30°C for 2 to 4 days and photographed. (B) Effects of PTP2 overexpression on capsule production. The relative packed cell volume was measured by calculating the ratio of the length of packed cell volume phase to the length of the total volume phase. *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant (P > 0.05). (C) Each indicated set of α cells were cocultured with KN99a on V8 medium in the dark at room temperature and photographed after 10 days.

FIG 7.

Ptp1 plays minor roles in growth, stress response, and virulence factor production. (A and B) Northern blot analyses using the total RNA isolated from WT (H99) strain and ptp2 and ptp2 hog1 mutants, which were grown to the mid-logarithmic phase at 30°C in YPD medium and were then exposed to 2.5 mM H2O2 or 1 M NaCl. Each membrane was hybridized with a PTP1-specific probe, washed, and developed. Ethidium bromide staining results of rRNA were used as loading controls. (C) Each indicated strain grown to the mid-logarithmic phase was 10-fold serially diluted and spotted onto YPD medium containing CdSO4 (25 μM), H2O2 (3 mM), or flucytosine (600 μg/ml). Cells were incubated at 30°C for 2 to 4 days and photographed. To determine thermotolerance, cells were spotted onto YPD agar medium and incubated at 30°C, 37°C, or 39 to 40°C for 4 days and photographed. (D) Cells were spotted onto niger seed medium containing 0.1% or 0.5% glucose, incubated at 30°C, and photographed daily. (E) Roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in urease production. Cells were spotted onto the Christensen's medium, incubated at 30°C, and photographed daily.

However, several phenotypes manifested by the PTP2oe strain implied that Ptp2 may have targets other than Hog1. First, overexpression of PTP2 further enhanced the CdSO4 resistance of the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 6A). Second, the PTP2oe strain exhibited even higher H2O2 sensitivity than the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 6A). Third, the PTP2oe strain was more resistant to flucytosine even than the wild-type strain, which was in contrast to the phenotype of the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 6A). However, the fact that HOG1 deletion in the PTP2oe strain generated hog1Δ mutant levels of flucytosine sensitivity indicated that such Ptp2 targets may operate through the HOG pathway. In summary, Hog1 was likely the major Ptp2 target, but other kinases may also be targets of Ptp2 in C. neoformans.

Ptp1 acted as a backup PTP for Ptp2 and played minor roles in growth, differentiation, stress response, and virulence factor production in C. neoformans.

Ptp1 was shown to be dispensable for growth, differentiation, and virulence factor production in C. neoformans. Ptp1 also appeared to be largely dispensable for the environmental stress response. The ptp1Δ mutant was as resistant to osmotic, oxidative, and genotoxic stresses as was the wild-type strain (Fig. 4). However, some data suggested that Ptp1 may play some minor roles in the stress response. The ptp1Δ ptp2Δ double mutant exhibited a greater susceptibility to osmotic stresses, genotoxic agents (e.g., HU, MMS, and flucytosine), ketoconazole, and some oxidative stress agents (e.g., H2O2 and tBOOH) than the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 4 and 5). Therefore, it is possible that Ptp1 acts as a backup PTP to compensate for loss of Ptp2 following certain environmental stress responses. To address this possibility, we monitored PTP1 expression levels and patterns in ptp2Δ mutants during osmotic and oxidative stress responses (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, PTP1 expression was consistently high with or without osmotic and oxidative stresses in the ptp2Δ mutant but was only transiently induced in the wild-type strain (Fig. 7A). Such PTP1 induction in cells lacking PTP2 appeared to be mediated by the HOG pathway, as PTP1 was not induced in the ptp2Δ hog1Δ double mutant (Fig. 7B). In contrast, PTP2 induction levels in the ptp1Δ mutant were equivalent to those in the wild-type strain (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), indicating that a lack of Ptp1 did not affect PTP2 expression.

To further verify the minor roles of Ptp1, we examined whether PTP1 overexpression could rescue some phenotypes of the ptp2Δ mutant. For this purpose, we constructed a PTP1 overexpression (PTP1oe) strain by replacing its native promoter with the H3 promoter. We confirmed PTP1 overexpression by Northern blot analysis (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). PTP1 overexpression did not result in any discernible phenotypes in the wild-type background (Fig. 7C), probably due to the presence of intact Ptp2. However, PTP1 overexpression restored some stress resistance in the ptp2Δ mutant. Interestingly, PTP1 overexpression not only restored normal vegetative growth of the ptp2Δ mutant but also recovered its thermoresistance (Fig. 7C). The ptp2Δ PTP1oe strain was more resistant to H2O2 than the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 7C). In addition, PTP1 overexpression restored resistance to flucytosine and CdSO4 in the ptp2Δ mutant (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, severe melanin defects in the ptp2Δ mutant were also slightly recovered by PTP1 overexpression (Fig. 7D). In contrast, however, PTP1 overexpression did not restore capsule production in the ptp2Δ mutant (data not shown).

Urease, one of the virulence factors of C. neoformans, appeared to be regulated by both Ptp1 and Ptp2. The ptp1Δ mutant produced less urease than did the wild-type strain, and its defect was restored to normal by PTP1 complementation (Fig. 7E). However, the ptp2Δ mutant produced even less urease than the ptp1Δ mutant (Fig. 7E), indicating that Ptp1 and Ptp2 play minor and major roles in urease production.

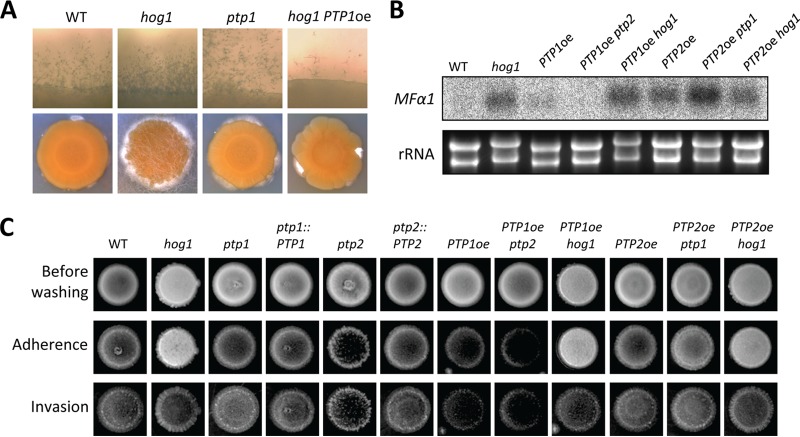

Although deletion of PTP1 did not significantly reduce or enhance mating, PTP1 overexpression reduced mating (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, PTP1 overexpression partially suppressed enhanced mating in the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 8A). If the MAPK Cpk1 was the Ptp1 target, PTP1 overexpression would be expected to inactivate Cpk1, resulting in decreased pheromone production. However, PTP1 overexpression did not reduce pheromone gene (MFα1) expression in the wild-type strain and was not able to suppress the enhanced MFα1 expression in the hog1Δ mutant (Fig. 8B), suggesting that PTP1 overexpression may inhibit the filamentous growth in a Hog1- and Cpk1-independent manner. To further support the role of Ptp1 in filamentous growth, we investigated whether Ptp1 was also involved in the adherence and invasiveness of C. neoformans because they are correlated phenotypes. For this purpose, we performed adherence and invasiveness assays as previously reported by Alspaugh et al. (39). The hog1Δ mutant exhibited enhanced agar adherence and invasion compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 8C). However, the PTP1 overexpression strain showed reduced agar adherence and invasion. All these data suggested that Ptp1 negatively controlled adherence and invasive growth as well as filamentous growth during mating.

FIG 8.

Hog1 and Ptp1 play opposing roles in sexual differentiation and adherence/invasion. (A) Each indicated α strain (WT [strain H99] and hog1, ptp1, and PTP1oe hog1 mutant strains) was cocultured with KN99a on V8 medium in the dark at room temperature and photographed after 13 days. (B) Northern blot analysis for monitoring pheromone gene (MFα1) expression was performed with total RNA isolated from solo cultures or cocultures of the following strains, which were grown for 24 h under mating conditions: WT (strain H99) and hog1 (YSB64), PTP1oe (YSB2586), PTP1oe ptp2 (YSB2572), PTP1oe hog1 (YSB2655), PTP2oe (YSB2569), PTP2oe ptp1 (YSB2590), PTP2oe hog1 (YSB2658) mutants. (C) Each strain was grown in liquid YPD medium for 16 h at 30°C. Five microliters of the culture was spotted onto filament agar plates and incubated at room temperature for 14 days. Agar adherence was determined by washing the plate under gently flowing water for 20 s. Agar invasion was assessed by gently rubbing each colony with a gloved finger under a water stream. After washing, colonies were photographed.

Taken together, our data demonstrated that Ptp1 served as a backup PTP for Ptp2 and may be able to play minor roles in growth, virulence factor production, and stress responses in the absence of Ptp2 and to regulate sexual reproduction by suppressing the filamentous growth and adherence/invasion in C. neoformans.

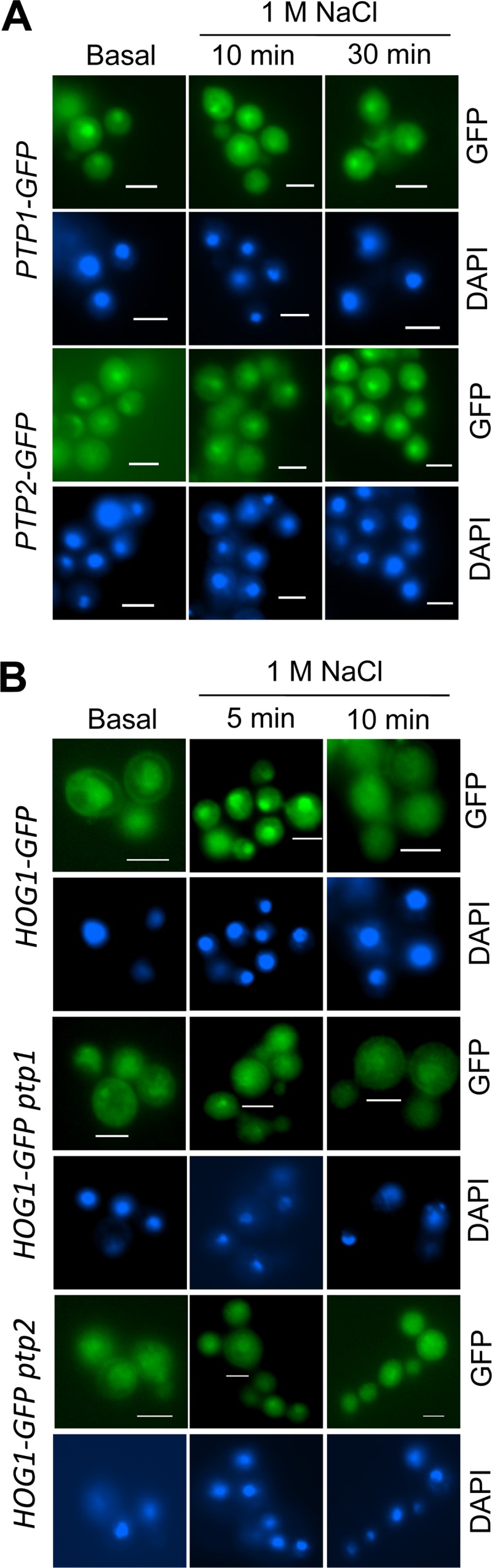

Cellular localization of Ptp1 and Ptp2 and their roles in Hog1 localization.

Previous studies of S. cerevisiae have demonstrated that the cellular localization of Hog1 is not governed by Hog1 phosphorylation but rather by the anchoring functions of Ptp2 and Ptp3 (40). Ptp2 localizes and tethers Hog1 to the nucleus, while Ptp3 localizes and anchors Hog1 to the cytosol. Such an anchoring function has not been observed for Ptp1. Thus, the role of Cryptococcus Ptp2 in the cellular localization of Hog1 remains unclear because C. neoformans contains only a single Ptp2/3 ortholog. In fact, the structural features of Cryptococcus Ptp2 are more homologous to the yeast Ptp3.

To investigate this question, we constructed strains expressing PTP1-GFP and PTP2-GFP, in which both C-terminal GFP fusion proteins were expressed by each native promoter and were confirmed to be functional (data not shown). Notably, we discovered that Ptp1 and Ptp2 were present in both the cytosol and the nucleus, with greater enrichment in the nucleus under unstressed conditions (Fig. 9A). Under stressed conditions (e.g., osmotic stress), the nuclearly enriched cellular localization of Ptp1 and Ptp2 was not significantly altered (Fig. 9A). In addition, to address whether the cellular localization of Ptp1 and Ptp2 may affect the localization of Hog1, we deleted the PTP1 and PTP2 genes in C. neoformans strains expressing a functional Hog1-GFP protein (Fig. 9B). Under unstressed conditions, Hog1 localized to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, albeit with greater enrichment in the nucleus. In response to osmotic shock, Hog1 transiently localized to the nucleus within 5 min and then later exhibited an even distribution within the cells (Fig. 9B), as previously reported (13). Interestingly, however, the transient nuclear enrichment of Hog1 was less evident when PTP1 or PTP2 was deleted (Fig. 9B). Taken together, our data showed that Ptp1 and Ptp2 localized to the cytosol and nucleus, with greater enrichment in the nucleus, which may support the nucleus-anchoring function of Ptp1 and Ptp2 for Hog1 in C. neoformans.

FIG 9.

Cellular localization of Ptp1 and Ptp2 and their Hog1-anchoring function. (A) Strains expressing Ptp1-GFP (YSB2785) or Ptp2-GFP (YSB2891) were cultured in YPD liquid medium at 30°C for 16 h and subcultured in YPD liquid medium containing 1 M NaCl for the indicated times. (B) Roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in the cellular localization of Hog1. Hog1-GFP expressing strains, in which PTP1 or PTP2 was deleted (YSB2558 and YSB2563, respectively), were exposed to 1 M NaCl for the indicated times as described for panel A. The cellular localization of each GFP fusion protein was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. For DAPI staining of the nucleus, cells were fixed by formaldehyde. Bars, 10 μm.

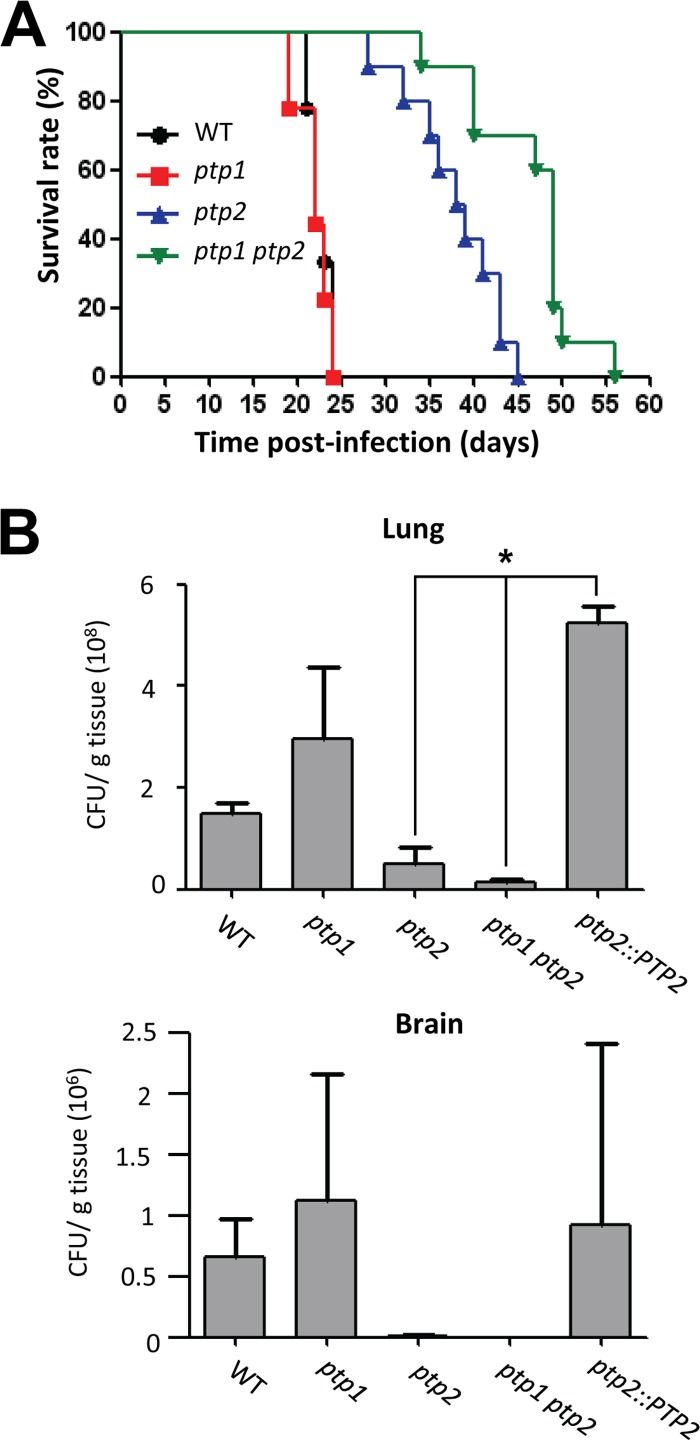

Roles of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in C. neoformans virulence.

Our prior study showed that deletion of HOG1 or PBS2 only slightly attenuates C. neoformans virulence, despite their pleiotropic roles (13). The current study demonstrated that Ptp1 and Ptp2 played minor and major roles, respectively, in controlling the HOG pathway of C. neoformans. Therefore, we next investigated how deletion of PTP1 or PTP2 affected the virulence of C. neoformans. In a murine model of systemic cryptococcosis, the ptp1Δ mutant was as virulent as the wild-type strain (average survival, 22 days), while the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ double mutants exhibited severely attenuated virulence (Fig. 10A), suggesting that Ptp2 played a critical role in determining the virulence of Cryptococcus. Interestingly, however, the virulence of the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutant (average survival, 46.3 days) was significantly more attenuated than that of the ptp2Δ mutant (average survival, 38 days), indicating that Ptp1 may play a minor role in determining the virulence of C. neoformans.

FIG 10.

Ptp1 and Ptp2 play minor and major roles in survival, proliferation, and virulence of C. neoformans within the host. (A) A/J mice were infected with 105 cells of the WT strain (H99; black line with circles) or ptp1 (red line with rectangles), ptp2 (blue line with triangles), or ptp1 ptp2 (green line with inversed triangles) strains by intranasal inhalation. Virulence attenuation was measured by statistical analysis using a log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. P values were 0.6859 for WT versus ptp1 mutant, <0.0001 for WT versus ptp2 mutant, <0.0001 for WT versus ptp1 ptp2 mutant, and 0.0019 for ptp2 versus ptp1 ptp2 mutant. (B) A/J mice were infected with 105 cells of the WT strain, ptp1, ptp2, ptp1 ptp2 mutant strains, or ptp2::PTP2 complemented strain by intranasal inhalation. Fungal burden (CFU/g tissue) was measured by plating homogenates of the lung and the brain tissues onto YPD medium containing chloramphenicol (100 μg/ml) at 15 days postinfection. *, P < 0.05.

To investigate whether the highly attenuated virulence of the ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants stemmed from reduced cell survival and proliferation within the host, we performed fungal burden assays to measure the number of C. neoformans cells recovered from the lungs and the brains of sacrificed mice. Both ptp2Δ and ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutants showed severe defects in colonizing and proliferating in the lungs (Fig. 10B). Therefore, our data in this in vivo model demonstrated that Ptp1 and Ptp2 played minor and major roles, respectively, in determining the virulence of C. neoformans. In particular, Ptp2 was critical for the survival and proliferation of the pathogen during the initial stages of infection.

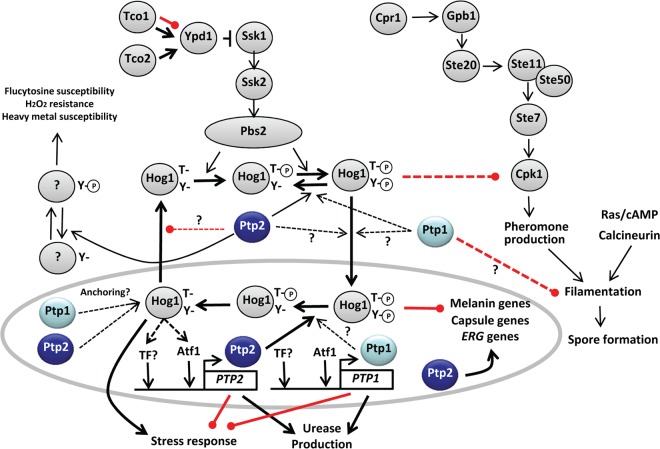

DISCUSSION

C. neoformans is a fungal pathogen that causes fatal meningoencephalitis in humans. While many aspects of C. neoformans virulence have been well studied, the roles of PTPs in this process were not clear. Therefore, in this study we characterized the functions of two PTPs, Ptp1 and Ptp2, in C. neoformans for the first time; the proposed regulatory mechanism of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in C. neoformans is summarized in Fig. 11. Our data provided important insights into the distinct and overlapping roles of these two PTPs in C. neoformans.

FIG 11.

Proposed regulatory mechanism of protein tyrosine phosphatases in C. neoformans. Both PTP1 and PTP2 were strongly induced in response to environmental stresses in a Hog1-dependent manner, partly through the Atf1 transcription factor. Ptp1 and Ptp2 localized to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, with greater enrichment in the nucleus. Both PTPs appeared to have a Hog1-anchoring function. Ptp2 was a major negative-feedback regulator of Hog1 and controlled stress responses, virulence factor productions (melanin, capsule, and urease), and sexual differentiation. However, Ptp2 may also be involved in other signaling pathways, which controlled susceptibilities to heavy metal, flucytosine, and H2O2. In contrast, Ptp1 played minor roles in the HOG pathway and also controlled the filamentation process during mating of C. neoformans in a Hog1-independent manner.

In contrast to S. cerevisiae, Candida albicans, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, which express three PTPs, C. neoformans expresses only two PTPs, the levels of which are tightly regulated by the MAPK Hog1. In the current study, we demonstrated that the stress-inducible induction of PTP1 and PTP2 required kinase activity of Hog1. These data provided a reasonable explanation for our previous finding that Hog1KD (the kinase-dead version of Hog1) does not undergo dephosphorylation and exhibits increased phosphorylation following osmotic stress (13). The lack of Hog1 kinase activity failed to induce PTP1 and PTP2 expression, resulting in increased phosphorylation of Hog1. Similarly, the Tyr residue of Hog1KD in S. cerevisiae is also constitutively phosphorylated (21). Moreover, in S. cerevisiae, both PTP2 and PTP3 are induced by osmotic shock in a Hog1-dependent manner (20), suggesting that both ScPtp2 and ScPtp3 are negative-feedback regulators of Hog1. In contrast to these results, Wurgler-Murphy et al. observed that expression of PTP2 and PTP3 are transcriptionally induced by osmotic shock but in a Hog1-independent manner (21). It remains unknown whether PTP1 expression is controlled by the HOG pathway in S. cerevisiae. In C. neoformans, however, our data clearly demonstrated that both PTP1 and PTP2 were under transcriptional control by active Hog1.

Despite the Hog1-dependent, stress-inducible expression of PTP1 and PTP2, several lines of evidence indicated that only Ptp2 appeared to be a major negative regulator of Hog1 in C. neoformans. First, disruption of PTP2, but not PTP1, increased basal phosphorylation levels of Hog1. Second, the majority of the ptp2Δ phenotypes were opposite to those of the hog1Δ mutant. Most importantly, the ptp2Δ hog1Δ mutant was phenotypically similar to the hog1Δ mutant. In S. cerevisiae, ScPtp2 and ScPtp3 have been shown to play major and minor roles, respectively, in controlling Hog1; however, deletion of both PTP2 and PTP3 greatly increases pY levels of Hog1 compared to each single deletion, suggesting that they may have redundant roles (20, 21). However, unlike the Cryptococcus ptp2Δ mutant, which exhibits growth defects, the ptp2Δ ptp3Δ mutant does not show any growth defects in S. cerevisiae because increased pY levels in Hog1 only minimally increase the dual phosphorylation (pTY) of Hog1 (21). Supporting this, additional deletion of a phospho-Ser/Thr-specific phosphatase gene, PTC1, in the ptp2Δ background leads to growth arrest by Hog1 overactivation (35). Interestingly, we found that deletion of PTP2 increased pY and pTY phosphorylation of Hog1 and resulted in discernible growth defects in C. neoformans, suggesting that Tyr phosphorylation was closely connected to subsequent Thr phosphorylation in Cryptococcus Hog1. However, it is possible that additional deletion of a Hog1-specific PP2C type gene will further enhance the dual phosphorylation of Hog1, along with PTP2 deletion, and may result in more-severe growth defects, as has been observed in the lethal effects of YPD1 deletion or fludioxonil treatment (16, 34). C. neoformans appears to contain six putative PP2C genes in its genome. Currently, the functional connection of each PP2C gene to MAPK and other signaling cascades is still under investigation.

Several studies have investigated the role of Ptp2 in regulation of other MAPK systems in S. cerevisiae. In yeast, Ptp2 is the more effective negative regulator of Hog1 and Mpk1, while Ptp3 is the more effective negative regulator of Fus3 (19, 41). In the Mpk1 MAPK pathway for cell integrity regulation, Ptp2 physically interacts with Mpk1 to dephosphorylate Mpk1-pY, which is induced by heat shock at 39°C (23). Ptp3 also plays a minor role in dephosphorylating Mpk1. In response to heat shock, the expression of PTP2, but not PTP3, is induced by Mpk1 but not by Hog1 (23). In the Fus3/Kss1 MAPK pathway for pheromone response mating, Ptp3 mainly controls dephosphorylation of the MAPK Fus3, while Ptp2 plays some minor roles (22). In C. neoformans, however, Cpk1 (a Fus3/Kss1 ortholog) in the pheromone-responsive pathway and Mpk1 in the cell wall integrity pathway are not likely to be major Ptp2 targets. If Cpk1 were a target of Ptp2, overexpression of PTP2 would be expected to perturb normal mating and suppress the enhanced mating of the hog1Δ mutant. However, PTP2 overexpression enhanced mating and did not suppress the enhanced mating of the hog1Δ mutant. If Mpk1 were a target of Ptp2, the PTP2oe strain would be expected to show hypersensitivity to cell wall-damaging agents, such as Congo red (CR) and calcofluor white (CFW). However, the PTP2oe strain was as resistant to CR and CFW as the wild-type strain (data not shown). Based on our unpublished data, the hog1Δ mpk1Δ mutant is much more sensitive to H2O2 than each single mutant. However, PTP2 overexpression did not further increase H2O2 sensitivity in the hog1Δ mutant. In summary, the functions of Ptp2 appeared to be largely limited to regulation of the MAPK Hog1.

While Hog1 was obviously a major target of Ptp2, other signaling pathways appeared to also be regulated by Ptp2 in C. neoformans. The PTP2oe strain often showed more-severe or opposite phenotypes compared to the hog1Δ mutant in response to stresses (e.g., CdSO4, H2O2, and flucytosine); however, these potential additional targets are not yet clear. Ptp2 is likely to be involved in cell cycle control signaling pathways, as was observed in our results demonstrating retarded growth and swollen morphology. In S. pombe, the overexpression of either pyp1+ or pyp2+, orthologs of CnPtp2, not only causes mitotic delay in a wee1 kinase-dependent manner (42, 43) but also inhibits the transcription of fbp1, which encodes fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, and sexual development of the organism, both of which are controlled by the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway (44). In C. albicans, the nutrient-sensing target of rapamycin (Tor1) signaling pathway regulates Ptp2 and Ptp3 to control Hog1 for sustained hyphal elongation (45). Therefore, upstream and downstream signaling pathways governing Ptp2 regulation other than the HOG pathway need to be further elucidated in C. neoformans.

In our study, Ptp1 appeared to be largely dispensable for Hog1 signaling and the growth of C. neoformans, despite its Hog1-dependent induction. Nevertheless, Ptp1 was also found to have some minor roles in the stress response and virulence factor regulation in C. neoformans based on several findings. First, in the absence of Ptp2, PTP1 induction was more sustained under stress conditions in a Hog1-dependent manner. Second, the ptp1Δ ptp2Δ mutant showed a greater susceptibility to genotoxic and oxidative stresses than the ptp2Δ mutant. Third, PTP1 overexpression rescued some of the ptp2Δ phenotypes, including growth, stress resistance, and melanin production. Fourth, deletion of PTP1 reduced urease production. Fifth, deletion of PTP1 exacerbated the attenuated virulence of the ptp2Δ mutant. Although ScPtp1 is the first PTP identified in budding yeast, its physiological functions are poorly known because its deletion or overexpression does not generate any phenotypic differences from wild-type strains (46, 47). Nevertheless, because overexpression of PTP1 can suppress the synthetic lethality of ptp2Δ ptc1Δ mutants and because ptp1Δ ptp2Δ ptc1Δ triple mutants grow even slower than ptp2Δ ptc1Δ double mutants, Ptp1 may play some minor roles in the absence of Ptp2 in S. cerevisiae. Therefore, the backup PTP role of Ptp1 may be generally conserved among fungi.

One notable role of Ptp1 is its involvement in sexual differentiation. Overexpression of PTP1, but not PTP2, reduced normal mating efficiency and suppressed enhanced mating in the hog1Δ mutant. However, PTP1 overexpression failed to suppress enhanced MFα1 expression, strongly suggesting that Ptp1 could modulate mating without direct involvement in Cpk1 and pheromone production. In S. cerevisiae, Ptp1 was originally thought to be distinct from the MAPK signaling pathways and to have a broad substrate specificity (48). Recently, however, Ptp1 was found to physically interact with and negatively regulate the MAPK Kss1, which controls the diploid pseudohyphal growth and haploid invasive filamentous growth of S. cerevisiae (49). During the mating process of S. cerevisiae, the MAPK Fus3 plays a major role in the pheromone response, while Kss1 plays a prominent role in invasive growth. In fact, C. neoformans contains another MAPK gene (CNAG_02531), which is highly paralogous to CPK1 (CNAG_02511), in its genome. Based on our unpublished data, however, deletion of CNAG_02531 did not cause any mating defects, suggesting that CNAG_02531 was not likely to be a target of Ptp1. In addition, Fpr3, an FK506-binding protein, is known to be a direct Ptp1 target in S. cerevisiae (48). The calcineurin pathway, which can be inhibited by FK506, is involved in the mating and filamentous growth of C. neoformans (50). Therefore, it remains to be determined which Tyr kinases are targeted and how they are regulated by Ptp1 to control filamentous growth in future studies.

The Hog1-anchoring function of Ptp1 and Ptp2 in C. neoformans is also notable. Hog1 phosphorylation levels did not appear to affect Hog1 localization in C. neoformans for the following reasons. First, Hog1 was transiently enriched (within 5 min) in the nucleus upon osmotic stress, during which Hog1 was dephosphorylated. Second, deletion of PTP2 increased Hog1 phosphorylation but failed to enrich the nuclear localization of Hog1. This is similar to observations in S. cerevisiae showing that dephosphorylation of Hog1 is not required for its nuclear export during adaptation (40). In S. cerevisiae, highly phosphorylated Hog1, as observed in the ptp2Δ ptp3Δ mutant, can be exported from the nucleus, similar to the phenotype of the wild-type strain. Control of Hog1 cellular localization is orchestrated by the anchoring functions of Ptp2 and Ptp3. Ptp2 is localized in the nucleus and tethers Hog1 in the nucleus, whereas Ptp3 is localized in the cytosol (40). Thus, in the ptp2Δ mutant, which does not have the capability to anchor Hog1 in the nucleus, Hog1 is localized to the cytosol. Similarly, in the ptp3Δ mutant, which does not have the capability to tether Hog1 in the cytoplasm, Hog1 is enriched in the nucleus. However, PTP2 overexpression sequesters the majority of Hog1 to the nucleus, while PTP3 overexpression sequesters Hog1 in the cytoplasm. These anchoring and tethering functions of Ptp2/3 do not require the catalytic activity of PTPs (40). Furthermore, neither Hog1-pY nor Hog1 kinase activity is required for PTP tethering. However, Hog1 kinase activity is required for the export of Hog1 because the kinase-dead Hog1 protein is retained in the nucleus, even after osmotic shock. Therefore, kinase activity is required to upregulate or activate proteins other than phosphatases to allow the export of Hog1. In C. neoformans, Ptp1 and Ptp2 localized to both the cytosol and the nucleus but were enriched in the nucleus. Furthermore, the finding that deletion of PTP1 or PTP2 reduced transient nuclear accumulation of Hog1 under stressed conditions implied that both Ptp1 and Ptp2 may have Hog1-anchoring functions in the nucleus of C. neoformans. However, it remains to be addressed how Ptp1 and Ptp2 modulate the cellular localization of Hog1.

The most important finding of our study was that both Ptp1 and Ptp2 played minor and major roles in determining the virulence of C. neoformans in a murine model of cryptococcosis. Because it exhibited defects in growth at high temperatures, in production of melanin, capsule, and urease, and in stress resistance to multiple stresses (osmotic, genotoxic, and oxidative stresses), it was not surprising that the ptp2Δ mutant exhibited highly attenuated virulence. However, Ptp1 appeared to be required for the virulence of C. neoformans only in the absence of Ptp2, further supporting its role as a backup for Ptp2. Deletion of PTP1 appeared to exacerbate the attenuated virulence of the ptp2Δ mutant, mainly due to its reduced ability to produce urease and its resistance to some environmental stresses (e.g., genotoxic and oxidative stresses). Notably, all of these data further suggested that overactivation of the HOG pathway may be more effective as an antifungal therapeutic treatment than pathway inhibition. For example, fludioxonil, a commercially available agricultural antifungal agent, is known to hyperactivate the HOG pathway by triggering the overaccumulation of intracellular glycerols and growth arrest with cell swelling and cytokinesis defects (34). Moreover, deletion of YPD1, which negatively regulates the HOG pathway, causes cell death (16). This study suggested that a specific inhibitor of PTP2 may effectively eliminate C. neoformans infections. Another benefit of using these types of inhibitors is their synergistic antifungal effect when administered with azoles or flucytosine. Our data demonstrated that the inhibition of Ptp2 significantly enhanced susceptibility to azole and flucytosine. Therefore, combinatorial therapy with a Ptp2 inhibitor and azoles or flucytosine could be very effective for the treatment of cryptococcosis.

In conclusion, Ptp2 (or both Ptp1 and Ptp2) may be an effective antifungal drug target for monotherapy or combination therapy in patients with systemic cryptococcosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS