Abstract

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae and related yeast species, the TEA transcription factor Tec1, together with a second transcription factor, Ste12, controls development, including cell adhesion and filament formation. Tec1-Ste12 complexes control target genes through Tec1 binding sites (TEA consensus sequences [TCSs]) that can be further combined with Ste12 binding sites (pheromone response elements [PREs]) for cooperative DNA binding. The activity of Tec1-Ste12 complexes is known to be under negative control of the Dig1 and Dig2 (Dig1/2) transcriptional corepressors that confer regulation by upstream signaling pathways. Here, we found that Tec1 and Ste12 can associate with the transcriptional coregulators Msa1 and Msa2 (Msa1/2), which were previously found to associate with the cell cycle transcription factor complexes SBF (Swi4/Swi6 cell cycle box binding factor) and MBF (Mbp1/Swi6 cell cycle box binding factor) to control G1-specific transcription. We further show that Tec1-Ste12-Msa1/2 complexes (i) do not contain Swi4 or Mbp1, (ii) assemble at single TCSs or combined TCS-PREs in vitro, and (iii) coregulate genes involved in adhesive and filamentous growth by direct promoter binding in vivo. Finally, we found that, in contrast to Dig proteins, Msa1/2 seem to act as coactivators that enhance the transcriptional activity of Tec1-Ste12. Taken together, our findings add an additional layer of complexity to our understanding of the control mechanisms exerted by the evolutionarily conserved TEA domain and Ste12-like transcription factors.

INTRODUCTION

Transcriptional regulatory networks play a key role in coordinating temporal and spatial gene expression in response to environmental stimuli and developmental signaling pathways (1, 2). A crucial step in understanding eukaryotic gene regulation is the determination of the composition of transcription factor complexes and their assembly at specific genes through binding of transcriptional regulatory elements (3). The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an important model to study multicellular development of microorganisms and underlying transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (4, 5). A large number of studies have shown that S. cerevisiae can choose between unicellular growth and different adhesion-mediated multicellular lifestyles, for example, biofilms and filaments (6–8). These developmental switches are under the control of numerous evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways, including the Fus3/Kss1 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (9). This regulatory pathway has been studied in great detail and controls several developmental programs, including sexual conjugation (mating) as well as biofilm and filament formation (10). Central components of the pathway include the MAPKs Fus3 and Kss1, which control activity of the transcription factors Ste12 and Tec1. Ste12 is able to activate genes involved in both the mating and biofilm/filamentation programs (11–14). In contrast, Tec1 activates biofilm/filamentation genes, e.g., the adhesin gene FLO11, but is not required for the expression of mating genes (15–19). Importantly, Tec1 is degraded in response to mating pheromone, a mechanism that contributes to signaling specificity of the Fus3/Kss1 MAPK cascade (20–23).

In S. cerevisiae and several other yeast species, the DNA-binding transcription factors Ste12 and Tec1 are a paradigm to study the mechanisms of combinatorial and promoter-specific transcriptional control (19, 24, 25). Ste12 is the founding member of the Ste12-like transcription factors and specifically binds to pheromone response elements (PREs), which are present in the promoters of mating and biofilm/filamentation genes (11, 12, 19, 24, 25). Ste12 can form different complexes with other transcription factors such as Mcm1 and Matα1 to activate mating genes (12, 26–28) and Tec1 to induce biofilm/filamentation genes (24, 29). In addition, Ste12 activity is regulated by the Dig1 and Dig2 proteins, whose inhibitory functions are relieved upon MAPK activation (30–34). Tec1 is a member of the TEA family of transcriptional regulators that control cellular development in many eukaryotes (35). Common to this family is the TEA DNA binding domain that binds to conserved TEA consensus sequence (TCS) elements (36). By forming a complex with Ste12, Tec1 regulates target genes either by cooperative binding to combined filamentation response elements (FREs), which consist of a TCS and a PRE, or by binding to single TCS elements (24, 25, 29, 37). The Tec1-Ste12 complex can also associate with and be inhibited by Dig1 but not Dig2 (29). Finally, Tec1 was found to activate target genes by Ste12-independent mechanisms, although corresponding Tec1-interacting transcription factors have not yet been identified (38).

In this study, we aimed at further elucidating the mechanisms by which Tec1 and Ste12 confer promoter-specific transcriptional control. We found that Tec1 and Ste12 are able to form complexes in vivo and in vitro with the coregulators Msa1 and Msa2, which were previously found to interact with the cell cycle transcription factors Swi4 and Mbp1 (39). We further found that Tec1-Ste12-Msa complexes do not contain Swi4 or Mbp1 but assemble at Tec1-binding sites in vitro and coregulate genes involved in adhesive and filamentous growth by direct promoter binding in vivo. In contrast to the Dig proteins, Msa proteins act as coregulators that are able to enhance the transcriptional activity of Tec1-Ste12. In summary, our report adds a further layer of complexity to our understanding of the mechanisms of transcriptional control that are exerted by TEA domain and Ste12-like transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and growth conditions.

All yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material and were of the Σ1278b genetic background except EGY48-p1840 (40). Gene deletions for MSA1 (msa1Δ::hphNT1), MSA2 (msa2Δ::natNT2), and genomic C-terminal fusions (ProA, Myc3, Myc9, or YFP) to TEC1, STE12, MSA1, MSA2, SWI4, or MBP1 were obtained by using appropriate plasmids (see Table S2) and primers (see Table S3) following a PCR-based transformation method (41). TEC1, TEC1TEA, TEC1TEA-MSA1, and TEC1TEA-MSA2 alleles were inserted at the URA3 genomic locus by using integrative plasmids BHUM2787, BHUM1923, BHUM1935, and BHUM1936. Cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-based reporter genes were integrated at the LEU2 locus by using plasmids BHUM1754 (2xTCS-PCYC1-Ubi-Y-Δk-CFP) and BHUM1858 (PFLO11-Ubi-Y-Δk-CFP). Introduction of tec1Δ::HIS3 and ste12Δ::TRP1 mutations, PTEC1-TEC1 alleles, and TCS-PCYC1-lacZ reporter genes was described earlier (37, 38). Yeast culture medium was prepared following standard protocols (42), and adhesive growth tests were performed as described previously (14). Cycloheximide-induced translational shutoff experiments were performed as described previously (38).

Plasmids.

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Plasmid BHUM749 was isolated from a yeast two-hybrid library (43). Plasmid BHUM1639 was obtained by introducing a NotI restriction site into pNC955 (44) by site-directed mutagenesis. Plasmids BHUM1696 and BHUM1697 were obtained by homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae using plasmid pGREG546 (45). Plasmid BHUM1576 was obtained by fusion of the PGK1 promoter region to a fragment containing the FLO11 open reading frame and terminator region in plasmid YEplac195. BHUM1754 was obtained by PCR amplification of the 2xTCS-PCYC1 promoter region from plasmid BHUM175 (37) and NotI/Acc65I-based insertion into BHUM1716, which carries the Ubi-Y-Δk-CFP cassette from BHUM1639 in YIplac128. BHUM1858 was generated by substitution of the 2xTCS-PCYC1 promoter region of BHUM1754 for a 3-kb FLO11 promoter region amplified from B3782 (18) using restriction enzymes NotI and Acc65I. BHUM1923 and BHUM2787 were obtained using a PTEC1-TEC11–280 gene cassette and a PTEC1-TEC1 gene cassette (38) in plasmid YIplac211. BHUM1935 and BHUM1936 were obtained by PCR amplification of open reading frames of MSA1 and MSA2, respectively, from genomic DNA and fusion to a PTEC1-TEC11–280 gene cassette (38) in plasmid YIplac211. Plasmids BHUM2025 and BHUM2026 were obtained by PCR amplification of MSA1 and MSA2 fragments and insertion into Escherichia coli expression plasmid pET28a (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Yeast two-hybrid screen.

Yeast two-hybrid screening was performed using strain EGY48-p1840 transformed with plasmid BHUM752 as bait and a pJG4-5-based yeast genomic library as previously described (23).

β-Galactosidase assays.

Yeast strains carrying TCS-PCYC1-lacZ reporters were grown in selective liquid synthetic complete (SC) medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1, and cell extracts were prepared and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as described earlier (46). Assays were performed in triplicate, and the mean values of the results were determined. Standard deviations did not exceed 20%.

Quantitative fluorescence microscopy.

Yeast strains carrying 2xTCS-PCYC1-CFP or PFLO11-CFP reporters were grown in low fluorescence medium (47) to the exponential phase, and cells were imaged in a bright field and for cyan fluorescence using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with a Hamamatsu camera and a 63× oil lens. Fluorescent signals of 500 to 1,000 cells were quantified for each strain as described earlier (48).

Microarray analysis.

Duplicates of overnight cultures of appropriate yeast strains were grown in SC medium lacking His and Leu (SC–His–Leu medium), diluted into 30 ml fresh medium to an OD600 of 0.25, and cultivated to an OD600 of 1. Cells were harvested, and microarray analysis was performed using Affymetrix GeneChip Yeast Genome 2.0 arrays as described previously (38). Genes that (i) had an average signal intensity that differed by at least 15 units from that of the control strain and (ii) showed a fold change of at least 1.5 (calculated as the fold change of average expression in the duplicates) were defined as differentially expressed.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by reverse transcription of 500 ng of total RNA into cDNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). Quantitative real-time PCR experiments were performed in duplicate in 96-well plates using a CFX Connect Real-Time detection system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) as previously described (38). Gene-specific primers are shown in Table S3 in the supplemental material. The reaction mix had a final volume of 20 μl and consisted of 10 μl 2× iQ SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany), 1 μl of each primer (0.5 μM final concentration), 7 μl H2O, and 1 μl of the cDNA preparation. The thermocycling program consisted of one hold at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 44 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C. After completion of these cycles, melting curve data were collected to determine PCR specificity, contamination, and the absence of primer dimers. The detection of the threshold cycle was done automatically by the cycler software. Quantification of gene expression was carried out using the formula 2CT(reference) − CT(target) (where CT represents “threshold cycle”) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Preparation of total yeast cell extracts.

Preparation of total yeast cells extracts was performed as previously described (49).

GST affinity purification.

Purification of glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusions and associated proteins from yeast cells was performed as previously described (23).

ProA-mediated coimmunoprecipitation.

Extracts from yeast strains producing ProA fusion proteins were prepared from cultures grown to an OD600 of 1 in SC–His–Leu medium. Cells were harvested and washed twice with IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA) and resuspended in 1 ml ice-cold IP buffer with 1 μg/ml pepstatin, Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and 0.05% Tween 20. Cells were broken by the use of a vortex procedure with glass beads for 5 min at 4°C, followed by addition of 400 μl IP buffer with protease inhibitors and Tween 20. Samples were again subjected to the vortex procedure for 3 min and centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm to remove cell debris. In total, 1.1 ml of the extract was mixed with 100 μl of 50% IgG-Sepharose. The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 3.5 h, and beads were washed three times with IP buffer plus Tween 20 and collected to purify ProA fusion and associated proteins. Samples were denatured by heating at 60°C for 8 min in urea buffer. For input controls, total cell extracts were prepared from an aliquot of harvested cells.

Immunoblot analysis.

Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Tec1, GST fusion proteins, and Myc-tagged and His-tagged proteins were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) technology after incubation of membranes with polyclonal rabbit anti-Tec1 antibodies (38), polyclonal goat anti-Cdc28 and rabbit anti-GST antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), monoclonal mouse anti-Myc antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), or antipolyhistidine antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany). As secondary antibodies, peroxidase-coupled goat anti-rabbit, donkey anti-goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or goat anti-mouse (Jackson Immuno Research, Suffolk, United Kingdom) antibodies were used. For quantification of signals, a ChemoCam Imager (INTAS, Göttingen, Germany) and LabImage 1D software (Kapelan, Leipzig, Germany) were used.

Purification of proteins from E. coli.

MBP-Tec1 and MBP-Ste12 proteins were purified from E. coli using plasmids BHUM388 and BHUM389 as described previously (24, 38). His-Msa1 and His-Msa2 proteins were purified from E. coli strain BL21(DE3)-Gold (Merck) using plasmids BHUM2025 and BHUM2026, respectively, following standard protocols. Essentially, E. coli strains were incubated in LB medium supplemented with 1% glucose and 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 4 h at 20°C. After lysis of cells and clarification of the supernatant, proteins were purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity chromatography (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

Protein-DNA complex formation was performed essentially as described previously (38). Briefly, Cy5-labeled DNA fragments carrying TCS, PRE, or FRE sequences were generated by annealing synthetic 5′ Cy5-labeled oligonucleotides (Metabion, Martinsried, Germany) and unlabeled complementary oligonucleotides (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The indicated amounts of labeled DNA fragments and purified proteins were mixed with 0.2 μg of poly(dI-dC)·poly(dI-dC) DNA, Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics), 20 μg bovine serum albumin (BSA), 16 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5), and 0.1 mM EDTA. When used together, MBP-Tec1, MBP-Ste12, His-Msa1, and His-Msa2 proteins were premixed and incubated on ice for 10 min before addition of DNA. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, samples were mixed with loading buffer and separated on 6% native polyacrylamide gels for 1.5 h at 110 to 150 V. Gels were directly scanned and visualized on a Typhoon Trio variable-mode manager (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany).

ChIP.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described previously (50). Briefly, yeast cultures were grown overnight in SC–His–Leu medium, diluted into 50 ml fresh medium to an OD600 of 0.25, and cultivated to an OD600 of 1. Protein-DNA cross-links were induced by incubation with formaldehyde (1% final concentration) for 30 min at room temperature, and the reaction was stopped by addition of glycine (320 mM final concentration). Cells were harvested and washed twice with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Pellets were suspended in 300 μl FA lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), and cells were broken with glass beads four times for 8 min each time with 2-min cooling steps between. The chromatin fraction was pelleted, resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold FA lysis buffer, sheared into ∼500-bp fragments by sonication four times for 30 s each time, and clarified by centrifugation. Myc-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated with 4 μl of monoclonal anti-Myc antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and rProtein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). Immune complexes were washed twice with 700 μl FA lysis buffer, twice with 700 μl chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) wash buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 0.25 M LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), and twice with 700 μl Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0). Protein-DNA complexes were eluted with 100 μl ChIP elution buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS), and protein-DNA cross-linking was reversed at 65°C overnight. The remaining protein was digested with 2.5 μl proteinase K, and DNA was purified by phenol extraction and precipitation. PCRs were performed using Taq polymerase (2 min at 95°C, 29 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 25 s at 68°C, and 5 min at 68°C) with 1/15 of immunoprecipitated DNA (ChIP) and 1/2,500 of the input DNA with primers listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Microarray data accession number.

Array data are available on the ArrayExpress database (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) under accession number E-MEXP-3619.

RESULTS

Tec1 physically associates with Msa1 and Msa2 in vivo and in vitro.

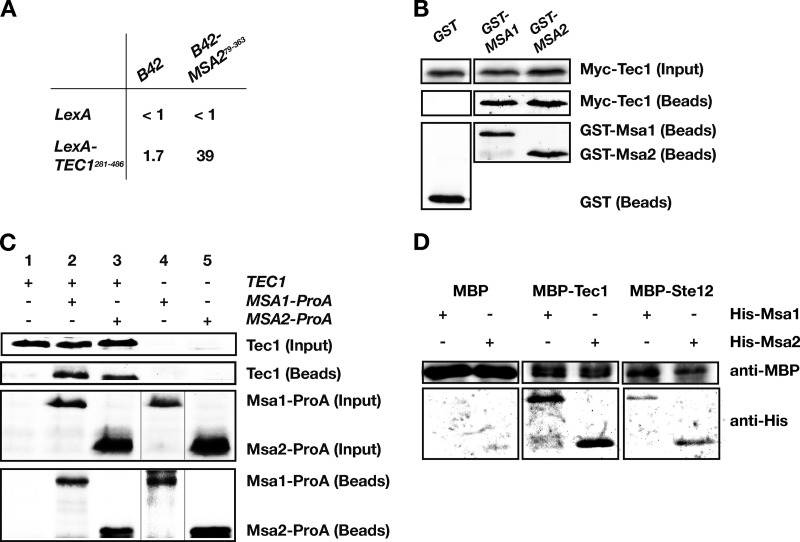

We performed a yeast two-hybrid screen to identify Tec1 interaction partners following a previously described protocol (23). Specifically, a lexA-TEC1 construct was used that lacks the Tec1 DNA-binding domain and leads to only minimal induction of a lexA-driven lacZ reporter gene (Fig. 1A). Screening of roughly 100,000 B42-fused yeast cDNAs (43) led to the identification of the G1-specific regulator protein Msa2 as a potential interaction partner for Tec1. Previous studies have shown that Msa2 is related to Msa1, an activator that confers proper timing of G1-specific transcription (39). We therefore tested whether full-length Tec1 is able to associate with Msa1 or Msa2 in vivo. For this purpose, we performed GST co-affinity purification experiments. We found that Tec1 could be efficiently copurified with GST-Msa1 as well as with GST-Msa2 (Fig. 1B). In vivo formation of complexes between Tec1 and Msa1 or Msa2 was further corroborated by coimmunoprecipitation using strains which produced Msa1-ProA or Msa2-ProA fusion proteins from single chromosomal copies and contained endogenous Tec1 levels (Fig. 1C). Finally, we purified MBP-Tec1, His-Msa1, and His-Msa2 from E. coli and found that Tec1 was able to directly interact with both Msa proteins in vitro (Fig. 1D). These data demonstrate that Msa1 and Msa2 are specific Tec1-interacting proteins.

FIG 1.

Interaction between Tec1, Msa1, and Msa2. (A) Two-hybrid interaction between Tec1 and Msa2. Numbers indicate β-galactosidase activities obtained in strain EGY48-p1840 expressing lexA (pEG202) or lexA-TEC1281–486 (BHUM752) in combination with B42 (pJG4-5) or B42-MSA279–363 (BHUM749). Values are the means of the results of three independent measurements. (B) Co-affinity purification of Tec1 with GST-Msa1 and GST-Msa2. Protein extracts were prepared from yeast strain YHUM216 expressing GST (pYGEX-2T), GST-MSA1 (BHUM1696), or GST-MSA2 (BHUM1697) together with Myc-TEC1 (BHUM768). The presence of Myc-Tec1 protein in cell extracts (Input) and in GST-purified complexes (Beads) was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Myc antibodies. GST, GST-Msa1, and GST-Msa2 were detected by antibodies against GST. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of Tec1 with Msa1-ProA and Msa2-ProA. Protein extracts were prepared from yeast strains YHUM1694 (TEC1) (lane 1), YHUM1995 (MSA1-ProA TEC1) (lane 2), YHUM1996 (MSA2-ProA TEC1) (lane 3), YHUM1997 (MSA1-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 4), and YHUM1998 (MSA2-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 5). The presence of Tec1 protein in cell extracts (Input) and in ProA-purified complexes (Beads) was analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-Tec1 antibodies. Msa1-ProA and Msa2-ProA were detected by secondary anti-goat antibodies. (D) Co-affinity purification of MBP-Tec1 or MBP-Ste12 with His-Msa1 or His-Msa2 purified from E. coli. MBP (4 μg), MBP-Tec1 (1 μg), or MBP-Ste12 (1 μg) was mixed with 1 μg of His-Msa1 or His-Msa2. MBP proteins were affinity purified and analyzed for presence of copurified His-Msa proteins by immunoblot analysis.

Msa1 and Msa2 form a complex with Tec1 bound to DNA and enhance Tec1-mediated gene expression.

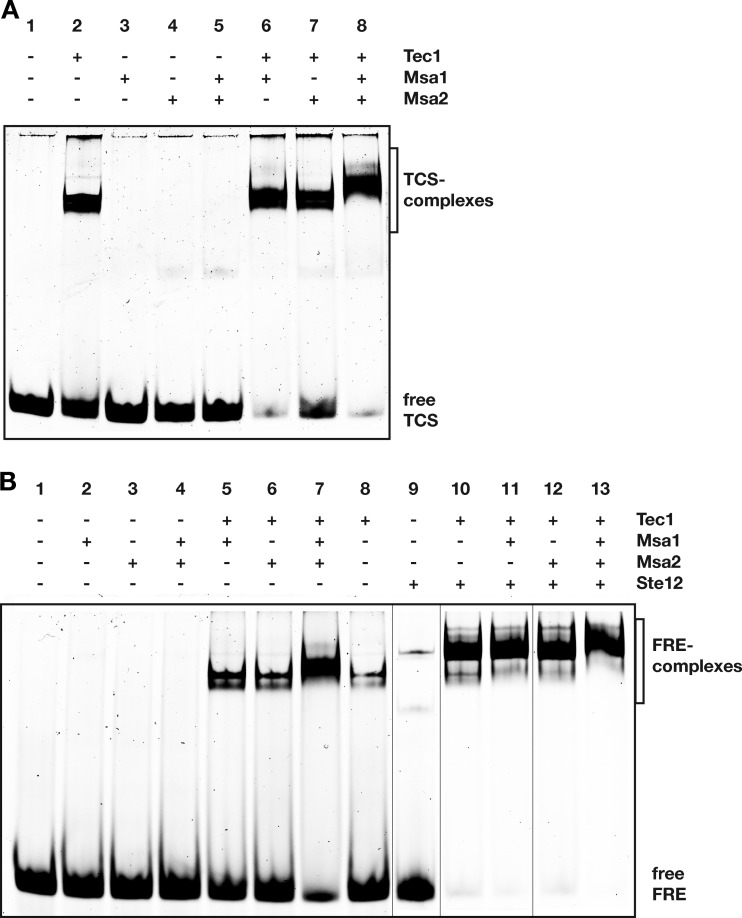

We next measured how Msa1 and Msa2 interact with Tec1 in the presence of DNA carrying a Tec1 binding site (TCS) by performing gel retardation analysis with proteins purified from E. coli. As previously shown (38), Tec1 efficiently bound to a single TCS at nanomolar concentrations (Fig. 2A). In contrast, Msa1 and Msa2 were unable to form stable TCS complexes (Fig. 2A), a finding that is in agreement with the fact that Msa1 and Msa2 both lack an obvious DNA-binding domain (www.uniprot.org). We next measured how Msa proteins affect the binding of Tec1 to the TCS. Here, we found that addition of Msa1 or Msa2 to Tec1 and TCS slightly stabilized formation of the Tec1-TCS complex but did not significantly alter its mobility. Addition of both proteins, however, led to a clear shift in the mobility of the Tec1-TCS complex (Fig. 2A). This suggests that Tec1 is able to form a stable complex together with both Msa1 and Msa2 when bound to its target site.

FIG 2.

Formation of protein-DNA complexes. (A) Interaction of Tec1 with TCS in the absence and presence of Msa proteins. Gel shift analysis was performed with approximately 1 nM Cy5-labeled TCS DNA and 100 nM MBP-Tec1, His-Msa1, and His-Msa2 proteins that were premixed in the indicated combinations. TCS complexes and free TCS are indicated and were visualized after separation by native gel electrophoresis. (B) Interaction of Tec1 and Ste12 with FRE (combined TCS and PRE) in the absence and presence of Msa proteins. Formation of FRE complexes was analyzed as described for panel A by using 1 nM Cy5-labeled FRE DNA and 50 nM indicated proteins.

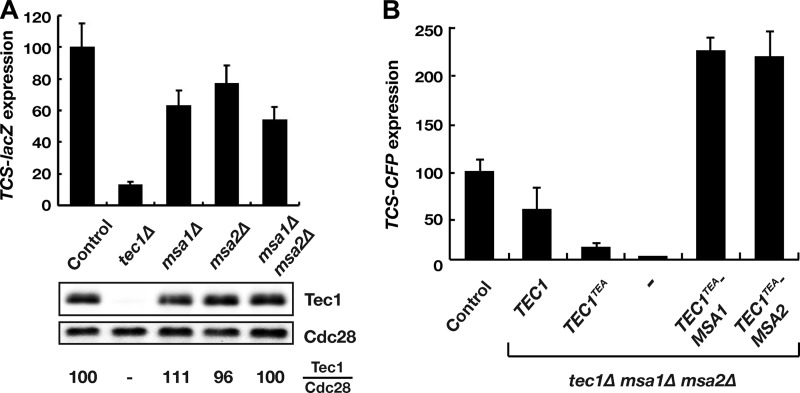

To address the physiological role of the Tec1-Msa interaction, we expressed a TCS-driven lacZ reporter gene in yeast strains lacking TEC1, MSA1, MSA2, or both MSA genes. As expected, TCS-lacZ reporter gene expression is markedly reduced in strains that lack Tec1 (Fig. 3A). Deletion of MSA1 or MSA2 or both also led to a clear reduction in TCS-lacZ reporter gene activity, indicating that Msa1 and Msa2 enhance Tec1-dependent gene expression. Importantly, absence of Msa proteins did not affect the intracellular amounts or stability of Tec1 (Fig. 3A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To further measure the effect of Msa proteins on TCS-mediated gene expression, we fused MSA1 or MSA2 to the N-terminal part of TEC1 containing the TEA domain (TEC1TEA), which efficiently binds TCS elements but is unable to activate transcription (38). These constructs were expressed in a yeast strain lacking TEC1, MSA1, and MSA2 and carrying a TCS-CFP reporter gene. As expected, TEC1TEA alone was unable to efficiently activate expression of TCS-CFP (Fig. 3B). Also, activation of the reporter gene by TEC1 was reduced in the absence of Msa1 and Msa2. However, we found that both the TEC1TEA-MSA1 and the TEC1TEA-MSA2 fusions led to efficient activation of the TCS-CFP reporter in the absence of Tec1, Msa1, and Msa2 (Fig. 3B), supporting the view that Msa1 and Msa2 are able to efficiently enhance TCS-mediated gene expression.

FIG 3.

Effect of Msa1 and Msa2 on Tec1-dependent gene expression. (A) Expression of a TCS-lacZ reporter gene was determined in yeast strains YHUM1702 (Control), YHUM1630 (tec1Δ), YHUM1872 (msa1Δ), YHUM1873 (msa2Δ), and YHUM1897 (msa1Δ msa2Δ). Bars (upper part) show the reporter gene activity corrected to the Tec1 protein levels (lower part) and as a percentage of the activity of the control strain. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Tec1 protein levels were determined by immunoblot analysis using specific antibodies against Tec1 and Cdc28 and are indicated as percentages of Tec1 protein present in the control strain. (B) Expression of a TCS-CFP reporter gene was determined in the presence of TEC1, MSA1, and MSA2 in yeast strain YHUM2277 (Control), in the tec1Δ msa1Δ msa2Δ mutant strain YHUM2197 (−), and in tec1Δ msa1Δ msa2Δ mutant strains that carry TEC1 (YHUM2281), TEC1TEA (YHUM2279), TEC1TEA-MSA1 (YHUM2183), or TEC1TEA-MSA2 (YHUM2184) fusion genes. Bars represent reporter gene expression relative to the control strain.

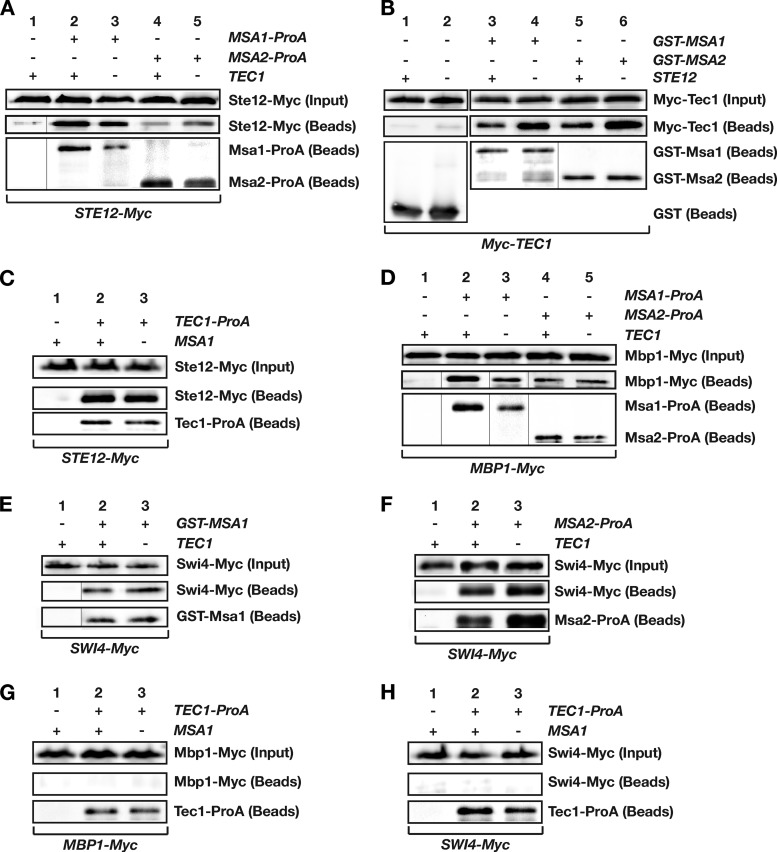

Tec1-Msa complexes can also include Ste12 but do not contain Swi4 or Mbp1.

Tec1 is well documented to associate directly with Ste12 (24, 29, 37, 38). We therefore wanted to know whether Ste12 can also interact with Msa proteins and whether Tec1-Msa complexes can include Ste12. We found that Ste12 was able to interact with Msa1 and Msa2 independently of Tec1 both in vitro (Fig. 1D) and in vivo (Fig. 4A; see also Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Moreover, weak Tec1-independent association of Ste12 with Msa1 and Msa2 could be observed in gel retardation assays using DNA containing a Ste12 recognition site (PRE) (see Fig. S3A). In contrast, we found that (i) Tec1-Msa complex formation is independent of Ste12 in vivo (Fig. 4B), a result that was expected from in vitro binding (Fig. 1C), and that (ii) in vivo Tec1-Ste12 complex formation is independent of Msa1 (Fig. 4C). Thus, both Tec1 and Ste12 appear to be able to directly interact with Msa1 and Msa2. We next wanted to know whether all four proteins might be present in a single complex. For this purpose, we performed gel retardation analysis using single TCS elements and FREs. With the TCS element, no change in mobility was observed after adding Ste12 to either the Tec1-TCS complex or the Tec1-Msa1-Msa2-TCS complex (see Fig. S3B). This suggests that Ste12 does not bind efficiently to Tec1 and Msa proteins under the conditions used for gel retardation analysis or that binding of Ste12 does not affect mobility of Tec1-TCS complexes due to, e.g., its biophysical properties. However, clear results were obtained with DNA carrying the FRE. As previously shown, Tec1 and Ste12 cooperatively bound to this element and formed a very stable complex (Fig. 2B, compare lanes 8 to 10). Moreover, the presence of both Msa proteins together with Tec1 and Ste12 led to the formation of a FRE complex whose mobility differed from that of Tec1-Ste12-FRE as well as from that of Tec1-Msa1-Msa2-FRE (Fig. 2B [compare lanes 7, 10, and 13]; see also Fig. S3C). This complex is likely to contain Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2, and the data indicate that all four proteins can associate at Tec1 target sites.

FIG 4.

Analysis of Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, Msa2, Mbp1, and Swi4 interactions. (A) Tec1-independent interaction between Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2. Protein extracts were prepared from STE12-Myc yeast strains YHUM2168 (TEC1) (lane 1), YHUM2153 (MSA1-ProA TEC1) (lane 2), YHUM2161 (MSA1-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 3), YHUM2157 (MSA2-ProA TEC1) (lane 4), and YHUM2164 (MSA2-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 5), and the presence of Ste12-Myc was analyzed by immunoblotting before (input) and after (beads) ProA-mediated affinity purification. (B) Ste12-independent interaction between Tec1, Msa1, and Msa2 was determined in yeast strains RH2754 (STE12) and RH2755 (ste12Δ) expressing Myc-TEC1 together with GST alone (lanes 1 and 2), GST-MSA1 (lanes 3 and 4), or GST-MSA2 (lanes 5 and 6) from plasmids and by GST-mediated affinity purification and immunoblotting. (C) Msa1-independent interaction between Tec1 and Ste12 was measured in STE12-Myc yeast strains YHUM2168 (MSA1) (lane 1), YHUM2169 (TEC1-ProA MSA1) (lane 2), and YHUM2170 (TEC1-ProA msa1Δ) (lane 3). (D) Tec1-independent interaction between Msa1, Msa2, and Mbp1 was determined in MBP1-Myc yeast strains YHUM2171 (TEC1) (lane 1), YHUM2154 (MSA1-ProA TEC1) (lane 2), YHUM2162 (MSA1-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 3), YHUM2158 (MSA2-ProA TEC1) (lane 4), and YHUM2165 (MSA2-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 5). (E) Tec1-independent interaction between Swi4 and Msa1 was determined in SWI4-Myc yeast strains YHUM2174 (TEC1) and YHUM2163 (tec1Δ) expressing GST (lane 1) or GST-MSA1 (lanes 2 and 3) from plasmids. (F) Tec1-independent interaction between Swi4 and Msa2 was measured using SWI4-Myc yeast strains YHUM2174 (TEC1) (lane 1), YHUM2159 (MSA2-ProA TEC1) (lane 2), and YHUM2166 (MSA2-ProA tec1Δ) (lane 3). (G) Interaction between Mbp1 and Tec1 was determined using MBP1-Myc yeast strains YHUM2171 (MSA1) (lane 1), YHUM2172 (TEC1-ProA MSA1) (lane 2), and YHUM2173 (TEC1-ProA msa1Δ) (lane 3). (H) Interaction between Swi4 and Tec1 was measured using SWI4-Myc yeast strains YHUM2174 (MSA1) (lane 1), YHUM2175 (TEC1-ProA MSA1) (lane 2), and YHUM2176 (TEC1-ProA msa1Δ) (lane 3).

Previous studies have shown that Msa proteins can associate with the G1/S transcription factor complexes SBF (Swi4/Swi6 cell cycle box binding factor) and MBF (Mbp1/Swi6 cell cycle box binding factor) to confer G1-specific transcription (39). In addition, TEC1 gene expression is cell cycle regulated and peaks in G1 (51). We therefore wanted to know whether Tec1-Msa complexes include Swi4 or Mbp1. Here, we found that Tec1 associated with neither Mbp1 nor Swi4 and that complex formation of Msa1 or Msa2 with Mbp1 or Swi4 was independent of the presence of Tec1 (Fig. 4D to H; see also Fig. S2B in the supplemental material). Thus, Msa proteins are likely to form separate complexes with Tec1 and Mbp1/Swi4 and do not bridge these DNA-binding transcription factors.

Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 coregulate genes involved in adhesive and filamentous growth by direct promoter binding.

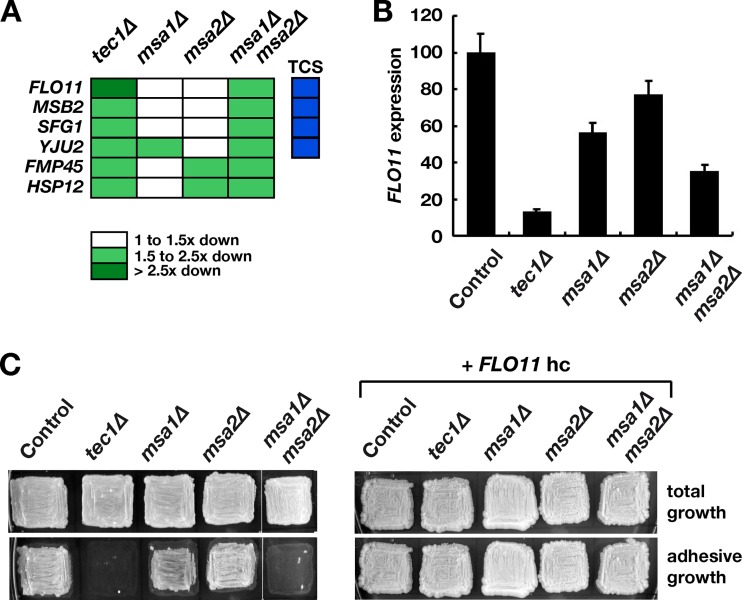

Because we found that Tec1-Msa complexes appeared to activate transcription when bound to TCS elements, we wanted to identify genes that are coregulated by Tec1 and Msa proteins, specifically, the genes that are positively regulated by these transcription factors. For this purpose, we performed genome-wide comparative transcript analysis using high-density oligonucleotide arrays with yeast strains that lack Tec1, Msa1, Msa2, or both Msa proteins. This approach identified six genes that were positively regulated by both Tec1 and Msa proteins (Fig. 5A; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). Interestingly, five of these genes, namely, FLO11, MSB2, SFG1, FMP45, and HSP12, have been reported to affect adhesion, biofilm formation, and/or filamentation (see Table S4). We therefore further tested whether Msa proteins are required for FLO11-dependent adhesion and biofilm formation, processes that are well known to be under the control of Tec1. We found that expression of a FLO11-CFP reporter gene was significantly reduced in strains that lack both Msa proteins (Fig. 5B), verifying the positive effect of Msa1 and Msa2 on FLO11. As a consequence, the msa1Δ msa2Δ mutant strain was significantly suppressed for adhesive growth, which is comparable to the results seen with a strain lacking TEC1 (Fig. 5C). Moreover, adhesive growth could be restored by overexpression of the FLO11 gene, supporting the conclusion that Tec1 and Msa proteins confer adhesive growth by activating FLO11.

FIG 5.

Coregulation of genes involved in FLO11-mediated adhesion and filamentation by Tec1, Msa1, and Msa2. (A) A class of genes positively coregulated by Tec1 and Msa proteins was identified by transcriptional profiling using yeast strains YHUM1700 (tec1Δ), YHUM1864 (msa1Δ), YHUM1865 (msa2Δ), and YHUM1900 (msa1Δ msa2Δ) and microarrays. Expression of indicated genes is shown as fold changes (white and green boxes), and the presence of TCS elements in corresponding promoter regions is indicated (blue boxes). (B) Expression of a FLO11-CFP reporter gene was determined in yeast strains YHUM1988 (Control), YHUM2194 (tec1Δ), YHUM2050 (msa1Δ), YHUM2051 (msa2Δ), and YHUM2052 (msa1Δ msa2Δ) by quantitative fluorescence microscopy. Bars represent reporter gene expression relative to the control strain. (C) Adhesive growth of yeast strains YHUM1694 (Control), YHUM1700 (tec1Δ), YHUM1864 (msa1Δ), YHUM1865 (msa2Δ), and YHUM1900 (msa1Δ msa2Δ) carrying control plasmid YEplac195 (left) or FLO11 on high-copy-number plasmid BHUM1576 (right) was determined after cultivation on solid SC-Ura medium for 3 days. Plates were photographed before (total growth) and after (adhesive growth) removal of nonadhesive cells by a washing assay.

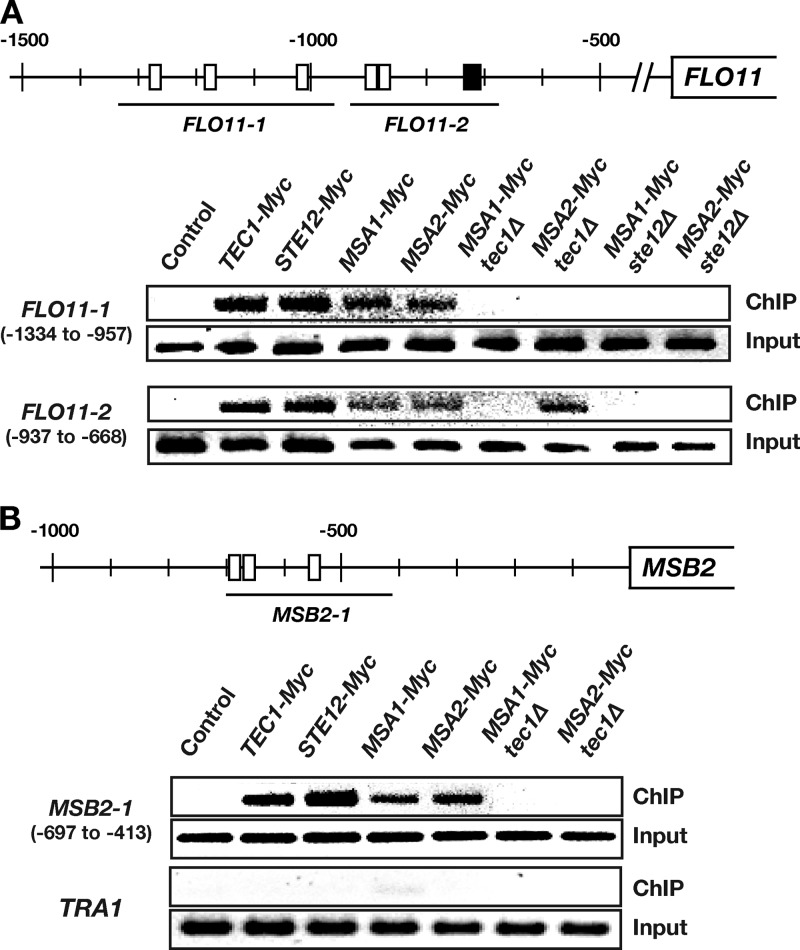

Finally, we determined if Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 bind to target gene promoters in vivo by performing chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using yeast strains that produce epitope-tagged and functional versions of the transcription factors (Fig. 6; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). In the case of FMP45 and HSP12, which do not contain binding sites for Tec1 or Ste12, no transcription factor binding was found (see Fig. S4), indicating indirect regulation by Tec1, Ste12, and Msa proteins. For SFG1 and YJU2, two genes that carry TCS promoter elements, binding of Tec1 and Ste12 but not of Msa1 or Msa2 was detected (see Fig. S4), suggesting that these two genes are directly regulated by Tec1-Ste12 and indirectly by Msa proteins. Finally, all four transcription factors were found to bind the promoters of FLO11 and MSB2 (Fig. 6), whose roles in adhesion and filamentation are well documented (5, 8). For FLO11, we found binding of Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 at two promoter regions (FLO11-1 and FLO11-2) that were previously described as conferring regulation by Tec1 and/or Ste12 (18). At FLO11-1, which contains three TCS elements, binding of Msa1 and Msa2 was lost in the absence of Tec1, indicating that both Msa proteins are recruited to this region via Tec1 binding to TCS elements. Binding of Msa proteins was also lost in the absence of Ste12; that result was most likely caused by the well-documented strong decrease of Tec1 levels observed in ste12Δ strains (38). However, Msa1 and Msa2 protein levels were not decreased in the absence of Tec1 or Ste12 (see Fig. S5). For FLO11-2, which carries two TCS elements and one FRE site, we found that binding of Msa1, but not binding of Msa2, was lost in the absence of Tec1. However, Msa2 binding was absent in ste12Δ mutant strains, indicating that Msa2 can be recruited to the FLO11-2 region independently of Tec1 either by Ste12 binding to the FRE or by another DNA-binding protein whose expression depends on Ste12. In the case of MSB2, we analyzed a promoter region that contains three TCS elements (Fig. 6B, MSB2-1). Here, we also found binding of Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2. As in the case of FLO11-1, binding of both Msa proteins was dependent on the presence of Tec1.

FIG 6.

In vivo binding of target gene promoters by Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2. (A) Analysis of the FLO11 promoter. The upper part shows the two FLO11-1 and FLO11-2 regions that were analyzed for transcription factor binding. The positions of consensus binding sites for Tec1 (TCS; white boxes) and combined binding sites for Tec1 and Ste12 (FRE; black boxes) are indicated relative to the translation start site. The lower part shows the binding of transcription factors that was determined in yeast strains YHUM1694 (Control without Myc), YHUM2167 (TEC1-Myc), YHUM2168 (STE12-Myc), YHUM2097 (MSA1-Myc), YHUM2098 (MSA2-Myc), YHUM2099 (MSA1-Myc tec1Δ), YHUM2100 (MSA2-Myc tec1Δ), YHUM2231 (MSA1-Myc ste12Δ), and YHUM2232 (MSA2-Myc ste12Δ) by Myc-directed chromatin immunoprecipitation, PCR amplification of regions FLO11-1 and FLO11-2 using immunoprecipitated (ChIP) or input DNA, separation of PCR products on 2% agarose, and visualization with ethidium bromide. (B) Analysis of the MSB2 promoter was performed as described for panel A using primers for the MSB2-1 promoter region that contains several consensus TCS sites. The TRA1 promoter region that lacks Tec1 and Ste12 binding sites was included as a negative control.

In summary, these data indicate that Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 confer activation of genes involved in adhesion and filamentous growth by direct promoter binding.

DISCUSSION

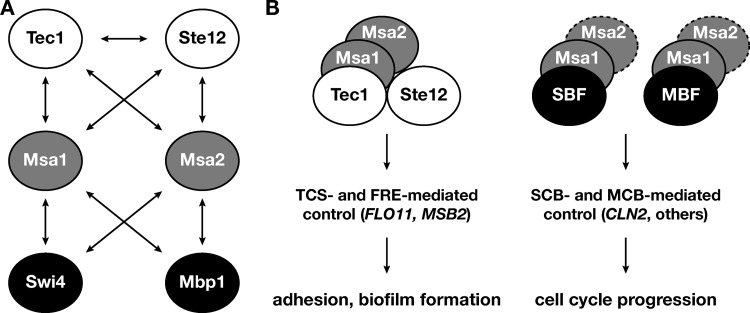

In this report, we provide novel insights into the mechanisms that enable the TEA transcription factor Tec1 to control target gene expression during development of S. cerevisiae. Specifically, we have shown that Tec1 and its interaction partner Ste12 associate in vitro and in vivo with the regulatory proteins Msa1 and Msa2, which were previously found to interact with the cell cycle transcription factors Swi4 and Mbp1 (39). We further provide evidence that Tec1-Ste12-Msa complexes do not contain Swi4 or Mbp1 and bind to promoters of genes involved in multicellular development to activate their expression. As such, our study uncovered new molecular connections that broaden the known combinatorial repertoire of Tec1 and Ste12 (Fig. 7A) and provided new insights into the composition and the physiological significance of functionally relevant complexes of these transcription factors.

FIG 7.

Target gene regulation by Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, Msa2, SBF, and MBF. (A) Summary of protein-protein interactions between the six transcription factors. (B) Different regulatory complexes formed by Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, Msa2, SBF, and MBF either regulate adhesion and biofilm formation via TCS and FRE promoter elements or control cell cycle progression by targeting SCB (Swi4-dependent cell cycle box) or MCB (Mpb1-dependent cell cycle box) sites. Dotted lines indicate that the role of Msa2 in G1-specific transcription is characterized only poorly (39). For further details, see the text.

How exactly do Tec1 and Ste12 interact with the Msa proteins to control gene expression? Our in vitro experiments with proteins purified from E. coli in combination with co-affinity purifications and ChIP analysis using yeast extracts provide evidence for the existence of a complex containing Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 that binds to TCS or FREs at target gene promoters (Fig. 7B). Importantly, we have demonstrated (i) binary interactions between Tec1 and Ste12 with Msa1 and Msa2 using purified proteins, (ii) complex formation between Tec1, Ste12, and Msa proteins in yeast extracts, (iii) the existence of a Tec1-Ste12-Msa1-Msa2 complex that binds to target DNA elements in vitro, (iv) the presence of all four transcription factors at target gene promoters in vivo, and (v) Tec1-dependent in vitro and in vivo binding of Msa proteins to target DNA. These findings strongly support the view that all four proteins interact to form a stable quaternary complex at target DNA. Our data do not preclude the possibility that further complexes, e.g., a ternary Tec1-Msa1-Msa2 complex, which we found to form at target DNA in vitro and that might be found to bind to target genes other than FLO11 and MSB2, are relevant in vivo. Here, detailed studies will be required to determine the exact stoichiometry of the physiologically relevant complexes. Also, the domains and individual residues involved in protein-protein interactions between Tec1, Ste12, Msa1, and Msa2 must be precisely mapped. So far, the domains required for the Tec1-Ste12 interaction are known only roughly (29), and no information is available concerning the domains involved in the association of Msa proteins with SBF and MBF (39).

Our data further suggest that binding of Msa proteins to Tec1 and Ste12 increases the transcriptional activation (TA) function conferred by these DNA-binding proteins and that the resulting Tec1-Ste12-Msa1-Msa2 complexes positively control a subset of genes involved in adhesion and biofilm/filament formation. Specifically, our analysis of Tec1TEA-Msa1 and Tec1TEA-Msa2 fusion proteins indicates that each of the two Msa proteins might carry its own TA domain, because both fusions confer efficient activation of a Tec1-dependent reporter gene. This conclusion is also supported by the observation that single msa gene deletions cause a weaker effect on target gene expression than deletion of both genes. Thus, both Msa proteins, if present in vivo, seem to bind to Tec1 and Ste12 and confer maximal transcriptional activation. The exact mechanisms by which Msa proteins confer this activity are not clear. Msa proteins could, for example, bind to the TA domains of Ste12 and Tec1, which have previously been identified (38, 52). Alternatively, they might provide additional TA activity to the Tec1-Ste12 complex by binding to other regions.

Our report shows that Msa proteins act as coregulators of not only cell division but also cellular development. Msa proteins were previously found as transcription factors that regulate the timing of G1-specific gene expression (39) and entry into the S phase (53). Specifically, both Msa proteins (i) are expressed in a cell cycle-dependent manner peaking during G1, (ii) associate with SBF and MBF, and (iii) bind to promoters of SBF- and MBF-regulated genes, for example, CLN2. Msa1 was further shown to associate with G1-specific promoter elements peaking in early G1 and to function as an activator of G1-specific genes and cell cycle initiation (39). In addition, MSA1 was identified as a high-copy-number suppressor of mutations in SLD2 and MBP11, which encode proteins forming a complex that is critical for the initiation of DNA replication, although Msa1 does not appear to directly associate with the Sld2-Dbp11 complex (53). Our report shows that Msa proteins fulfill a further physiological function and control expression of genes involved in adhesion and biofilm/filament formation by a separate mechanism through SBF- and MBF-independent association with Tec1 and Ste12 (Fig. 7). Thus, Msa proteins might fulfill a role as coordinators of cell division and development. It is interesting that expression of TEC1 is regulated by the cell cycle, with transcripts peaking in early G1 (51). This indicates that levels of Tec1-Msa complexes might increase during G1 and confer cell cycle-dependent regulation of developmental genes. Indeed, expression of MSB2, a gene that we found here to be positively coregulated by Tec1 and Msa proteins, is known to be cell cycle regulated (51). Msb2 is a signaling mucin that regulates activity of the invasive/filamentous MAPK cascade (54, 55) and consequently enables efficient expression of downstream targets, including not only TEC1 and FLO11 but also CLN1, which encodes a G1 cyclin (23, 56). Msb2 is also a potential target for phosphorylation by the Cdc28 cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) (57). Thus, Msb2 and Tec1, together with Msa proteins, might form a positive-feedback loop that controls the activity of the invasive/filamentous MAPK cascade. Moreover, this loop might be connected to the G1 phase of the cell cycle by a double positive-feedback loop, because (i) expression of MSB2 and TEC1 peaks in early G1 and (ii) Tec1 activates expression of CLN1. As such, this circuitry might represent a regulatory device for coordination of cell division and multicellular development which operates in addition to the well-established regulatory circuit which coordinates cell division and sexual mating and involves CDK inhibitor Far1 (10, 58). It has recently been shown that the activity of the mating MAPK cascade is linked to the cell cycle via a double negative-feedback regulatory loop, which is thought to be important to keep cells in an stable, nonmating state in the absence of a mating partner (59). It is therefore tempting to speculate that a double positive-feedback regulatory loop connecting the G1-CDK and invasive/filamentous MAPK cascade might help to stably maintain cells in an invasive or filamentous growth mode under, e.g., nutrient-limiting conditions.

In summary, our report provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms that underlie the regulatory circuits involving Tec1 and Ste12. Both transcription factors are deeply conserved within the phylum of Ascomycota, and they are functionally exchangeable between S. cerevisiae and the human-pathogenic yeast Candida albicans, which separated over 300 million years ago (60–66). In contrast, Msa-like proteins are not present outside the family of Saccharomycetaceae, for example, in C. albicans and other fungi carrying orthologs of Tec1 and Ste12 (our unpublished results). Thus, Msa coregulators appear to be a recent addition to the more ancient Tec1-Ste12-based regulatory circuit within the Saccharomycetaceae family. It will therefore be interesting to see which role Msa-like proteins fulfill in other members of the family, e.g., the human-pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata. In contrast, Tec1-interacting coregulators not related to Msa proteins might have evolved in other Ascomycota, as has been found for TEA regulators of insects and vertebrates. In Drosophila and mammals, for example, the TEA regulators Scalloped and TEAD1 to -4 are known to control development by interacting with the coactivators Yki and YAP, which are not found in fungi (67–69). Thus, not only adaptation of DNA-binding domains and cis-regulatory sequences but also the development of novel coregulators might be important to drive the evolution of fungal transcriptional regulatory networks (70–72).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Knop and Florian Bauer for generous gifts of plasmids. We are grateful to Konstanze Bandmann, Patrick Berndt, Raphael Birke, and Christof Taxis for help with some of the experiments and Diana Kruhl for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK 1216; SFB 987) and by the Marburg Center for Synthetic Microbiology (SYNMIKRO).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 April 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01599-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levine M, Davidson EH. 2005. Gene regulatory networks for development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:4936–4942. 10.1073/pnas.0408031102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busser BW, Bulyk ML, Michelson AM. 2008. Toward a systems-level understanding of developmental regulatory networks. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 18:521–529. 10.1016/j.gde.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reményi A, Schöler HR, Wilmanns M. 2004. Combinatorial control of gene expression. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:812–815. 10.1038/nsmb820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn S, Young ET. 2011. Transcriptional regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: transcription factor regulation and function, mechanisms of initiation, and roles of activators and coactivators. Genetics 189:705–736. 10.1534/genetics.111.127019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen PJ, Sprague GF., Jr 2012. The regulation of filamentous growth in yeast. Genetics 190:23–49. 10.1534/genetics.111.127456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gimeno CJ, Ljungdahl PO, Styles CA, Fink GR. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68:1077–1090. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90079-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds TB, Fink GR. 2001. Bakers' yeast, a model for fungal biofilm formation. Science 291:878–881. 10.1126/science.291.5505.878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brückner S, Mösch H-U. 2012. Choosing the right lifestyle: adhesion and development in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36:25–58. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaman S, Lippman SI, Zhao X, Broach JR. 2008. How Saccharomyces responds to nutrients. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42:27–81. 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen RE, Thorner J. 2007. Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773:1311–1340. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolan JW, Kirkman C, Fields S. 1989. The yeast Ste12 protein binds to the DNA sequence mediating pheromone induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:5703–5707. 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Errede B, Ammerer G. 1989. Ste12, a protein involved in cell-type-specific transcription and signal transduction in yeast, is part of protein-DNA complexes. Genes Dev. 3:1349–1361. 10.1101/gad.3.9.1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu H, Styles CA, Fink GR. 1993. Elements of the yeast pheromone response pathway required for filamentous growth of diploids. Science 262:1741–1744. 10.1126/science.8259520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts RL, Fink GR. 1994. Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: mating and invasive growth. Genes Dev. 8:2974–2985. 10.1101/gad.8.24.2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavrias V, Andrianopoulos A, Gimeno CJ, Timberlake WE. 1996. Saccharomyces cerevisiae TEC1 is required for pseudohyphal growth. Mol. Microbiol. 19:1255–1263. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mösch H-U, Fink GR. 1997. Dissection of filamentous growth by transposon mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 145:671–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo WS, Dranginis AM. 1998. The cell surface flocculin Flo11 is required for pseudohyphae formation and invasion by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:161–171. 10.1091/mbc.9.1.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rupp S, Summers E, Lo HJ, Madhani H, Fink GR. 1999. MAP kinase and cAMP filamentation signaling pathways converge on the unusually large promoter of the yeast FLO11 gene. EMBO J. 18:1257–1269. 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeitlinger J, Simon I, Harbison CT, Hannett NM, Volkert TL, Fink GR, Young RA. 2003. Program-specific distribution of a transcription factor dependent on partner transcription factor and MAPK signaling. Cell 113:395–404. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00301-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao MZ, Schwartz MA, Cantin GT, Yates JR, III, Madhani HD. 2004. Pheromone-dependent destruction of the Tec1 transcription factor is required for MAP kinase signaling specificity in yeast. Cell 119:991–1000. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brückner S, Köhler T, Braus GH, Heise B, Bolte M, Mösch H-U. 2004. Differential regulation of Tec1 by Fus3 and Kss1 confers signaling specificity in yeast development. Curr. Genet. 46:331–342. 10.1007/s00294-004-0545-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou S, Huang L, Liu H. 2004. Fus3-regulated Tec1 degradation through SCFCdc4 determines MAPK signaling specificity during mating in yeast. Cell 119:981–990. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brückner S, Kern S, Birke R, Saugar I, Ulrich H-D, Mösch H-U. 2011. The TEA transcription factor Tec1 links TOR and MAPK pathways to coordinate yeast development. Genetics 189:479–494. 10.1534/genetics.111.133629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madhani HD, Fink GR. 1997. Combinatorial control required for the specificity of yeast MAPK signaling. Science 275:1314–1317. 10.1126/science.275.5304.1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borneman AR, Gianoulis TA, Zhang ZD, Yu H, Rozowsky J, Seringhaus MR, Wang LY, Gerstein M, Snyder M. 2007. Divergence of transcription factor binding sites across related yeast species. Science 317:815–819. 10.1126/science.1140748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mueller CG, Nordheim A. 1991. A protein domain conserved between yeast MCM1 and human SRF directs ternary complex formation. EMBO J. 10:4219–4229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Primig M, Winkler H, Ammerer G. 1991. The DNA binding and oligomerization domain of MCM1 is sufficient for its interaction with other regulatory proteins. EMBO J. 10:4209–4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan YO, Stroke IL, Fields S. 1993. Coupling of cell identity to signal response in yeast: interaction between the alpha 1 and Ste12 proteins. Genes Dev. 7:1584–1597. 10.1101/gad.7.8.1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou S, Lane S, Liu H. 2006. Regulation of mating and filamentation genes by two distinct Ste12 complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:4794–4805. 10.1128/MCB.02053-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook JG, Bardwell L, Kron SJ, Thorner J. 1996. Two novel targets of the MAP kinase Kss1 are negative regulators of invasive growth in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 10:2831–2848. 10.1101/gad.10.22.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook JG, Bardwell L, Thorner J. 1997. Inhibitory and activating functions for MAPK Kss1 in the S. cerevisiae filamentous-growth signalling pathway. Nature 390:85–88. 10.1038/36355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tedford K, Kim S, Sa D, Stevens K, Tyers M. 1997. Regulation of the mating pheromone and invasive growth responses in yeast by two MAP kinase substrates. Curr. Biol. 7:228–238. 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00118-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bardwell L, Cook JG, Voora D, Baggott DM, Martinez AR, Thorner J. 1998. Repression of yeast Ste12 transcription factor by direct binding of unphosphorylated Kss1 MAPK and its regulation by the Ste7 MEK. Genes Dev. 12:2887–2898. 10.1101/gad.12.18.2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardwell L, Cook JG, Zhu-Shimoni JX, Voora D, Thorner J. 1998. Differential regulation of transcription: repression by unactivated mitogen-activated protein kinase Kss1 requires the Dig1 and Dig2 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:15400–15405. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrianopoulos A, Timberlake WE. 1991. ATTS, a new and conserved DNA binding domain. Plant Cell 3:747–748. 10.1105/tpc.3.8.747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anbanandam A, Albarado DC, Nguyen CT, Halder G, Gao X, Veeraraghavan S. 2006. Insights into transcription enhancer factor 1 (TEF-1) activity from the solution structure of the TEA domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:17225–17230. 10.1073/pnas.0607171103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köhler T, Wesche S, Taheri N, Braus GH, Mösch H-U. 2002. Dual role of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae TEA/ATTS family transcription factor Tec1p in regulation of gene expression and cellular development. Eukaryot. Cell 1:673–686. 10.1128/EC.1.5.673-686.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heise B, van der Felden J, Kern S, Malcher M, Brückner S, Mösch H-U. 2010. The TEA transcription factor Tec1 confers promoter-specific gene regulation by Ste12-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Eukaryot. Cell 9:514–531. 10.1128/EC.00251-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashe M, de Bruin RA, Kalashnikova T, McDonald WH, Yates JR, III, Wittenberg C. 2008. The SBF- and MBF-associated protein Msa1 is required for proper timing of G1-specific transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 283:6040–6049. 10.1074/jbc.M708248200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golemis EA, Brent R. 1992. Fused protein domains inhibit DNA binding by LexA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3006–3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, Knop M. 2004. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21:947–962. 10.1002/yea.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guthrie C, Fink GR. 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Methods Enzymol. 194:1–863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fashena SJ, Serebriiskii IG, Golemis EA. 2000. LexA-based two-hybrid systems. Methods Enzymol. 328:14–26. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)28387-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hackett EA, Esch RK, Maleri S, Errede B. 2006. A family of destabilized cyan fluorescent proteins as transcriptional reporters in S. cerevisiae. Yeast 23:333–349. 10.1002/yea.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansen G, Wu CL, Schade B, Thomas DY, Whiteway M. 2005. Drag&Drop cloning in yeast. Gene 344:43–51. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mösch H-U, Roberts RL, Fink GR. 1996. Ras2 signals via the Cdc42/Ste20/mitogen-activated protein kinase module to induce filamentous growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:5352–5356. 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheff MA, Thorn KS. 2004. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 21:661–670. 10.1002/yea.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jungbluth M, Renicke C, Taxis C. 2010. Targeted protein depletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by activation of a bidirectional degron. BMC Syst. Biol. 4:176. 10.1186/1752-0509-4-176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaffe MP, Schatz G. 1984. Two nuclear mutations that block mitochondrial protein import in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 81:4819–4823. 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aparicio O, Geisberg JV, Sekinger E, Yang A, Moqtaderi Z, Struhl K. 2005. Chromatin immunoprecipitation for determining the association of proteins with specific genomic sequences in vivo. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2005:Chapter 21:Unit 21.23. 10.1002/0471142727.mb2103s69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spellman PT, Sherlock G, Zhang MQ, Iyer VR, Anders K, Eisen MB, Brown PO, Botstein D, Futcher B. 1998. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:3273–3297. 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kirkman-Correia C, Stroke IL, Fields S. 1993. Functional domains of the yeast STE12 protein, a pheromone-responsive transcriptional activator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:3765–3772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li JM, Tetzlaff MT, Elledge SJ. 2008. Identification of MSA1, a cell cycle-regulated, dosage suppressor of drc1/sld2 and dpb11 mutants. Cell Cycle. 7:3388–3398. 10.4161/cc.7.21.6932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cullen PJ, Sabbagh W, Jr, Graham E, Irick MM, van Olden EK, Neal C, Delrow J, Bardwell L, Sprague GF., Jr 2004. A signaling mucin at the head of the Cdc42- and MAPK-dependent filamentous growth pathway in yeast. Genes Dev. 18:1695–1708. 10.1101/gad.1178604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chavel CA, Dionne HM, Birkaya B, Joshi J, Cullen PJ. 2010. Multiple signals converge on a differentiation MAPK pathway. PLoS Genet. 6:e1000883. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madhani HD, Galitski T, Lander ES, Fink GR. 1999. Effectors of a developmental mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade revealed by expression signatures of signaling mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:12530–12535. 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ubersax JA, Woodbury EL, Quang PN, Paraz M, Blethrow JD, Shah K, Shokat KM, Morgan DO. 2003. Targets of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Nature 425:859–864. 10.1038/nature02062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peter M, Gartner A, Horecka J, Ammerer G, Herskowitz I. 1993. FAR1 links the signal transduction pathway to the cell cycle machinery in yeast. Cell 73:747–760. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90254-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doncic A, Falleur-Fettig M, Skotheim JM. 2011. Distinct interactions select and maintain a specific cell fate. Mol. Cell 43:528–539. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu H, Köhler J, Fink GR. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723–1726. 10.1126/science.7992058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pesole G, Lotti M, Alberghina L, Saccone C. 1995. Evolutionary origin of nonuniversal CUGSer codon in some Candida species as inferred from a molecular phylogeny. Genetics 141:903–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schweizer A, Rupp S, Taylor BN, Rollinghoff M, Schroppel K. 2000. The TEA/ATTS transcription factor CaTec1p regulates hyphal development and virulence in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 38:435–445. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hedges SB. 2002. The origin and evolution of model organisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3:838–849. 10.1038/nrg929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borneman AR, Leigh-Bell JA, Yu H, Bertone P, Gerstein M, Snyder M. 2006. Target hub proteins serve as master regulators of development in yeast. Genes Dev. 20:435–448. 10.1101/gad.1389306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taylor JW, Berbee ML. 2006. Dating divergences in the Fungal Tree of Life: review and new analyses. Mycologia 98:838–849. 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE, Sorrells TR, Mitrovich QM, Hernday AD, Tuch BB, Andes DR, Johnson AD. 2012. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148:126–138. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hilman D, Gat U. 2011. The evolutionary history of YAP and the hippo/YAP pathway. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2403–2417. 10.1093/molbev/msr065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. 2011. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:877–883. 10.1038/ncb2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Varelas X, Wrana JL. 2012. Coordinating developmental signaling: novel roles for the Hippo pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 22:88–96. 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wray GA. 2007. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8:206–216. 10.1038/nrg2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tuch BB, Li H, Johnson AD. 2008. Evolution of eukaryotic transcription circuits. Science 319:1797–1799. 10.1126/science.1152398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wohlbach DJ, Thompson DA, Gasch AP, Regev A. 2009. From elements to modules: regulatory evolution in Ascomycota fungi. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19:571–578. 10.1016/j.gde.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.