Abstract

A/T mutations at immunoglobulin loci are introduced by DNA polymerase η (Polη) during an Msh2/6-dependent repair process which results in A's being mutated 2-fold more often than T's. This patch synthesis is initiated by a DNA incision event whose origin is still obscure. We report here the analysis of A/T oligonucleotide mutation substrates inserted at the heavy chain locus, including or not including internal C's or G's. Surprisingly, the template composed of only A's and T's was highly mutated over its entire 90-bp length, with a 2-fold decrease in mutation from the 5′ to the 3′ end and a constant A/T ratio of 4. These results imply that Polη synthesis was initiated from a break in the 5′-flanking region of the substrate and proceeded over its entire length. The A/T bias was strikingly altered in an Ung−/− background, which provides the first experimental evidence supporting a concerted action of Ung and Msh2/6 pathways to generate mutations at A/T bases. New analysis of Pms2−/− animals provided a complementary picture, revealing an A/T mutation ratio of 4. We therefore propose that Ung and Pms2 may exert a mutual backup function for the DNA incision that promotes synthesis by Polη, each with a distinct strand bias.

INTRODUCTION

Somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes is a locus-specific mutagenesis triggered by an initial deamination event performed by the lymphoid tissue-restricted enzyme activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) (1, 2). The process, which mostly but not exclusively takes place in B cells engaged in an immune response, allows for the unique adaptive biological process by which the immune system fighting a pathogen improves the specificity and efficiency of its recognition and therefore its control and elimination.

The paradoxical feature of hypermutation is the mutagenic outcome of the processing of this ordinary lesion, since uracils generated by cytidine deamination or dUTP incorporation during replication are normally efficiently and faithfully removed from the genome. This mutagenesis appears to result from a combined process of inefficient lesion detection, incomplete processing, and diverted repair, which mobilizes factors with a major function in genome maintenance and mutation avoidance as mutagenic partners, i.e., uracil glycosylase and mismatch repair (3).

Uracils can remain unprocessed, generating transitions at G/C bases during the next replication step. They can also be partially processed by uracil glycosylase, giving rise to abasic sites that will be bypassed by translesion DNA polymerases, among which Rev1 is the only one unambiguously shown to be implicated (4, 5). This process generates transversions but also transitions at the deamination site. Some uracils can be processed further, which results in DNA incision. Such nicks constitute a key step in class switch recombination, a second molecular alteration driven by AID at the switch regions of the Ig locus. This recombination process involves the rejoining of two double-strand breaks generated at distant sites, which replaces the constant domain of the heavy chain and thus allows the B cell to acquire new effector capacities. Nicks in DNA also take place in the V region, which results, in some events, in classical, error-free base excision repair.

Uracils paired with guanines can also be recognized as mismatches by Msh2-Msh6, which, together with exonuclease I (ExoI), triggers a long-patch error-prone DNA synthesis that relies on DNA polymerase η (Polη) and monoubiquitination of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (6, 7). This pathway generates mainly mutations at A/T bases distal to the initial deamination sites, because of the specific error-proneness of Polη, which copies Ts with low fidelity. This patch repair is unusual in that the second part of the mismatch repair complex, MutLα, composed of Pms2 and Mlh1, appears to be dispensable and relies on the sole Msh2-Msh6 complex (MutSα) together with ExoI (8, 9). Therefore, which endonuclease activity provides the DNA incision required to initiate error-prone synthesis is not completely clear. Moreover, the mutation pattern of Ig genes shows, on average, 2-fold higher targeting at A than at T bases, which suggests that Polη may preferentially synthesize the nontranscribed strand.

To understand the process directing strand choice, Uniraman and Schatz (10) designed transgenic light-chain V gene substrates in which they inserted a 100-bp oligonucleotide uniquely composed of alternate A's and T's, except for one central C or G as an AID target. The aim was to correlate the strand bias observed in the mutation pattern with the strand targeted for deamination, either the nontranscribed (top) or the transcribed (bottom) strand. Despite its elegance, this approach had major weaknesses and some inconsistencies. First, the transgene mutation load was very low, with 22 total mutations collected for the transgene including C and almost none for the one containing G. It was thus concluded that only the top strand could be targeted by AID. However, mice deficient in both uracil glycosylase and mismatch repair (Ung−/− Msh2−/−), a configuration that reveals the unprocessed footprint of AID-mediated deaminations, show a mutation profile with only a minor bias of C-over-G targeting (3, 8). Finally, the mutation pattern observed, biased toward T mutations, was not consistent with the mutagenic outcome of Polη copying the transcribed strand.

Transgenic mutation substrates are notoriously variable in their capacity to become efficiently targeted, so comparisons between mouse lines with unrelated insertion sites are difficult. Therefore, we performed a similar study by using knock-in strategies at the IgH locus, which allowed collection of large mutation databases and direct comparison of different substrates. Such a strategy gave a rather different picture of Polη function at the Ig locus, with a long patch length and different strand biases in Ung-proficient or -deficient backgrounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro Polη polymerization assay.

The oligo-C and oligo-G oligonucleotides were annealed and inserted by blunt-end cloning into the EcoRI site of the M13mp18 vector, with an orientation resulting in the presence of the oligo-G sequence in the single-stranded DNA form. Escherichia coli JM109 competent cells (Promega) were used for transformation, production of bacteriophage stocks, and midsize preparation of single-stranded DNA. We designed a polymerization initiation primer (ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT) that includes an SP6 sequence (underlined) and an M13 forward sequence priming 60 bp downstream of the oligo-G cloning site. Purified human Polη (80 nM) (Enzymax) was used to elongate this primer in the presence of 40 fmol (100 ng) single-stranded M13mp18-oligo-G vector, using polymerase-primer-template molar proportions of 50:10:1 in 25 μl of polymerization mixture containing 250 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA; MP), 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 60 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2.5% (vol/vol) glycerol (Sigma), and a 100 μM total concentration of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (Eurogentec). Following incubation for 1 h at 37°C, Polη was heat inactivated for 20 min at 65°C, and double-stranded polymerization products were denatured at 95°C for 10 min and purified on Nucleospin Gel Extract II columns with NTC buffer (Macherey-Nagel). A reaction mixture including [α-32P]dATP was run in parallel to check for the efficiency of the polymerase extension by electrophoresis on denaturing gels. Polymerization products that were fully elongated beyond the 5′ end of oligo-G were amplified by PCR with Phusion polymerase (New England BioLabs) (25 cycles of 10 s at 98°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 75 s at 72°C), with SP6 as the forward primer (ATTTAGGTGACACTATAG) and with a reverse primer complementary to the 5′-flanking region of oligo-G (GGTTAAAATAAAGACCTGGAG). PCR products of 250 bp were gel purified, cloned into the ZeroBlunt cloning vector (Invitrogen), and sequenced with the M13 reverse universal primer as described below.

Construction of mutation substrates.

A 4.1-kb segment containing the DQ52-JH locus and extending 510 bp downstream from the end of JH4 was amplified from day 14.1 embryonic stem (ES) cell DNA and cloned into the pCR-TOPO-XL vector (Invitrogen), and a ClaI site was inserted 43 bp downstream of the JH4 splicing site by PCR-based mutagenesis. A 2.3-kb fragment that was adjacent in the 3′ direction was amplified similarly, and then both fragments were inserted on either side of the floxed neor cassette of the pLNTK vector. We annealed the oligonucleotides oligo-G [CG(TATTATTAA)4GTATTATTAAGTATTATTAAG(TATTATTAA)4] and oligo-C [CG(TTAATAATA)4CTTAATAATACTTAATAATAC(TTAATAATA)4] (G's and C's are shown in bold) before their insertion into the ClaI restriction site to generate the oligo-G and oligo-C constructs, respectively, depending on the orientation of the insertion and named by the presence of G or C in the nontranscribed strand. Similarly, annealing of the oligo-noG and -noC oligonucleotides (with the same sequences, except for the absence of the three G's or C's) and cloning were used to generate the oligo-noG and -noC constructs, respectively. Transfection of day 14.1 ES cells, screening of clones, and Cre-mediated excision of the neor gene were performed as described previously (PCR primers are available on request) (11). We injected targeted ES clones into C57BL/6 blastocysts to generate 4 mouse lines: Tg-G, Tg-C, Tg-noG, and Tg-noC (Service d'Expérimentation Animale et de Transgénèse, Villejuif, France).

Mouse lines and breeding.

Screening of knock-in mice involved the following PCR primers flanking the loxP site for the 4 different lines: forward primer, TGGAAGGAGAGCTGTCTTAG; and reverse primer, TGAGTACTTGAAAACCCTCTCAC (35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 59°C, and 90 s at 72°C, using GoTaq polymerase [Promega]). Knock-in lines were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice and analyzed similarly in heterozygous or homozygous configuration. Tg-G and Tg-C lines were bred with Ung−/− mice (kindly provided by Deborah Barnes, South Mills, United Kingdom) to generate Ung−/− Tg-G and Tg-C lines. Pms2-deficient animals were kindly provided by Michael R. Liskay (Portland, OR). Animal experiments complied with the guidelines of the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale.

Immunization, cell sorting, genomic DNA extraction, and sequence analysis.

For each genotype, 3 to 6 mice were used for Peyer's patch or spleen cell isolation. Fourteen days before spleen cell isolation, mice were immunized by intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 109 sheep red blood cells (SRBC; Eurobio) resuspended in 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Peyer's patch or spleen cells were labeled with a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-B220 antibody (eBiosciences) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA; Vector) for sorting by FACS Aria I flow cytometry (Becton, Dickinson). Sorted B220+ PNAhigh cells were heat lysed at 95°C for 10 min, and proteins were digested for 30 min at 56°C with proteinase K (Roche). Three or four aliquots of 104 cells were used as a genomic DNA template to amplify the rearranged VDJ locus and adjacent JH4 intron. Five forward primers, amplifying the VH1, VH5, VH3, VH7, and VH9 gene families at a ratio of 6:3:1:1:1 (12), and a reverse primer in the JH4 intron (CTTGGATATTTGTCCCTGAGGGA) were used with Phusion polymerase (40 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 64°C, and 30 s at 72°C). PCR products (300 bp) were gel purified, A tailed with Taq polymerase (New England BioLabs), and ligated into the pCR2.1 cloning vector (original TA cloning kit; Invitrogen). Plasmid DNA was extracted by use of a Millipore 96-well miniprep system. Sequencing involved the use of an ABI Prism 3130xl genetic analyzer. The diversity of VDJ junctions and mutations within 90 or 93 bp of oligonucleotide transgenes and 66 bp of JH4 intronic sequences (43 bp upstream and 23 bp downstream of the oligonucleotide insertion site) was analyzed by use of CodonCode Aligner software.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Cochran-Armitage trend test for evaluating a significant 5′-to-3′ trend in normalized mutation distribution along the oligonucleotide transgene (13) and using the Jonckheere-Terpstra trend test for analysis of the 5′-to-3′ trend in normalized A/T mutation ratio (14).

Quantification of Ig heavy chain transcripts.

Splenic B cells were isolated by use of a mouse B cell enrichment kit (Stemcell Technologies) and cultivated for 3 days at 1 × 106 cells/ml in complete RPMI medium (15% fetal calf serum, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and nonessential amino acids) supplemented with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (serotype O55:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) and recombinant mouse interleukin-4 (IL-4; eBioscience) to final concentrations of 20 μg/ml and 25 ng/ml, respectively. For each genotype, total RNA from 1.5 × 106 cells was extracted with an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), including on-column DNase I (Qiagen) treatment. cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of RNA by random priming with an AffinityScript multiple-temperature cDNA synthesis kit (Agilent). A control reaction without reverse transcriptase was performed to assess contamination of the samples with genomic DNA. The relative abundances of different segments of the immunoglobulin pre-mRNA were measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) on a model 7500 Fast System real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed using an amount of cDNA corresponding to 10,000 cells in FastStart Universal SYBR green master mix (ROX) (Roche Applied Science) (2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C). The following primers were used: intron-JH3For, AGGATCTGCCAGAACTGAAG; intron-JH3Rev, CTCAGAGAAACCAGACAGTC; intron-JH4For, ACTGTCTAGGGATCTCAGAG; and intron-JH4Rev, AAGTCCCTATCCCATCATCC.

RESULTS

An A/T-rich mutation substrate inserted at the IgH locus.

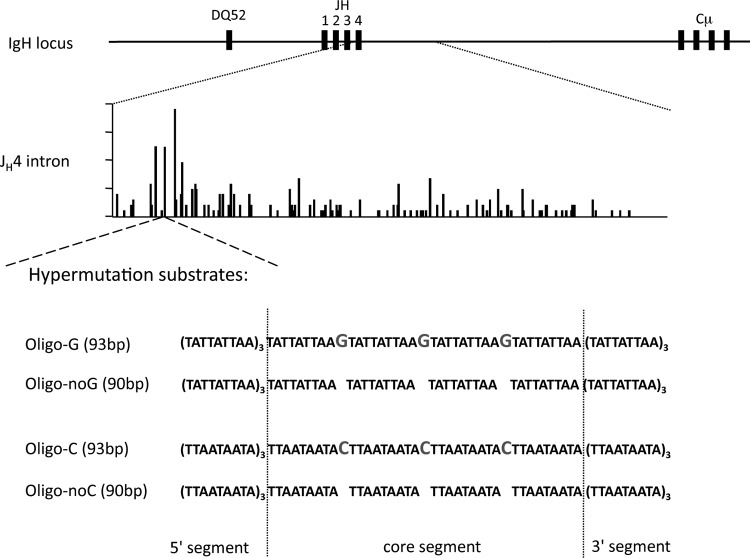

We designed an oligonucleotide that includes alternate A and T bases, as well as 3 G's or C's located in the central part, to be used as a hypermutation substrate after its insertion into the heavy chain locus. Because Polη has a preferred misincorporation pattern opposite T bases, the A/T targeting was anticipated to reveal the strand bias of the patch of Polη-mediated DNA synthesis during hypermutation. This 93-bp oligonucleotide includes 10 repeats of the 9-mer TATTATTAA motif, with 3 G's intercalated within the central repeats (Fig. 1, Oligo-G). Each of these G's is thus located within an AID RGYW (R is purine, Y is pyrimidine, and W is A or T) mutation hot spot, AGTA. Moreover, because WA (with A being the mutated base) is, on one strand or the other, the major Polη mutation hot spot at the Ig locus, each A or T of the oligonucleotide, including those flanking the G's, is thus embedded in such a motif. The knock-in construct consisted of a 6.4-kb fragment of the mouse JH4 genomic locus in which a ClaI site was generated by mutagenesis 43 bp downstream of the JH4 splicing site, a restriction site where the oligonucleotide was inserted. These constructs were used to generate a knock-in ES cell line, in which the floxed neor gene present 500 bp downstream of the JH4 intron border was excised. The recombinant mouse line thus obtained was named “transgene G” (Tg-G).

FIG 1.

Knock-in strategy for the generation of A/T-rich oligonucleotide mutation substrates. Oligonucleotide mutation substrates were inserted by knock-in at the heavy chain locus, 43 bp downstream of the JH4 segment. A schematized view of the mutation distribution within 490 bp of the JH4 intron highlights the mutation density around the oligonucleotide insertion site. The oligonucleotides consisted of 10 repeats of a 9-mer sequence, TATTATTAA, with 4 repeats flanking 3 G's separated by the same 9-mer sequence (oligo-G). Oligo-C represents the same sequence inserted in reverse orientation. Oligo-noG and -noC consisted of the same A/T backbone, with G's and C's, respectively, omitted. The 3 segments of the oligonucleotide transgene used in subsequent mutation analysis are represented as the 5′ segment, core segment, and 3′ segment.

We generated 3 other mouse strains: the “transgene C” (Tg-C) line, with the same oligonucleotide inserted in reverse polarity, and the “transgene no-C” and “transgene no-G” lines, with the 3 C's or G's absent from the same 90-nucleotide (nt) A/T backbone.

In vitro assay of Polη mutagenicity on an A/T-rich substrate.

Before analysis of mutations generated in B cells harboring the various transgenes, we determined the profile of mutations generated during Polη DNA synthesis in an in vitro assay after a copy of the oligo-G sequence was inserted into a single-stranded M13mp18 vector. Because the mutation frequency induced by Polη exceeds that of Phusion DNA polymerase by several orders of magnitude, we designed a PCR assay of the Polη-synthesized products to assess the mutagenicity of the enzyme. This PCR was based on an SP6 sequence included in the DNA synthesis primer, and thus unique to the DNA produced in the reaction, and a primer complementary to complete products that extended in the 3′ direction within the M13 vector (Fig. 2A). PCR products of the correct size were gel purified and cloned for sequence analysis.

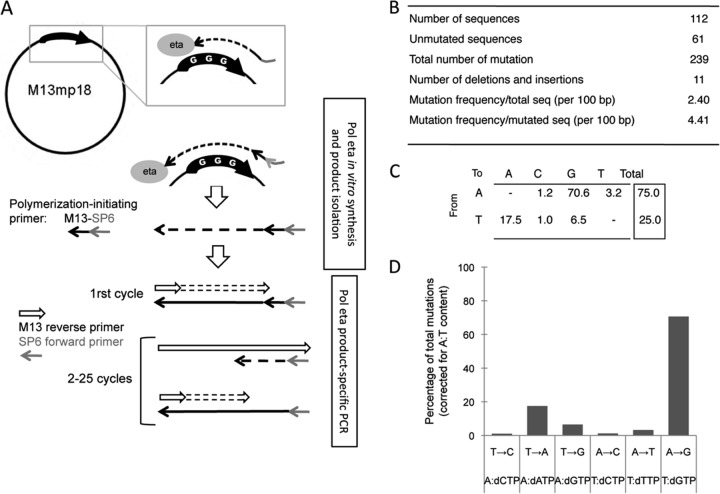

FIG 2.

Pattern of Polη synthesis in vitro on an A/T-rich oligonucleotide substrate. (A) Scheme of the strategy used for amplification of in vitro Polη DNA synthesis products. Oligo-G was inserted into a single-stranded M13 template and subjected to Polη-mediated DNA synthesis. The primer sequence included an SP6 sequence that allows selective amplification of complete in vitro-synthesized products. (B) Total mutations generated during in vitro Polη synthesis of the oligo-G template. (C) Pattern of mutations at A/T bases generated by Polη in vitro, after correction for base composition and reported for the synthesized strand. (D) Graphical representation of the mutation profile, with an indication of each nucleotide misincorporated opposite the template base.

We obtained 112 sequences, 54% of which were mutated and displayed between 1 and 8 mutations, which confirms the correct restriction of PCR amplification to the newly synthesized product (Fig. 2B). Moreover, no mutations were obtained when Klenow polymerase was used instead of Polη, as a control (not shown). The 239 mutations collected displayed a mutation bias similar to that described when Polη fidelity was assessed with the β-galactosidase sequence in the blue-white complementation assay or with the Vκox light chain sequence (15, 16). With these 2 approaches, the mutation pattern was determined after transformation of mismatch-containing M13 substrates into E. coli, as opposed to the direct PCR strategy used here. The 2 most frequent misincorporations resulted in A-to-G followed by T-to-A mutations (read in the synthesized strand), which agrees with the Polη-catalyzed misincorporation of G opposite T and A opposite A in vitro. We observed an overall A/T ratio of 3 after correction for base composition (of oligo-G, including 50 T's and 40 A's) (Fig. 2C and D). Thus, the unusual base composition of the oligonucleotide did not appear to affect the misincorporation specificity of Polη.

Control transgene substrates reveal a DNA polymerase patch synthesis exceeding the oligonucleotide length.

Mutation profiles were determined for the G and C transgenes and the 2 controls (Tg-noG and Tg-noC). These controls were included to define a core domain within the 90-bp oligonucleotide that would not be affected by mutagenesis initiated from either side.

The oligonucleotide transgenes were surprisingly highly mutated, so we restricted our analysis to Peyer's patch PNAhigh B cells from young mice (2 months of age) or, if young mice were not available, to splenic PNAhigh B cells isolated 14 days after immunization with SRBC (Table 1). Even so, transgenes accumulated up to 17 mutations, a complex situation because such mutations generated additional G and C bases, and thus new and uncontrolled AID targets. The insertion site, at the beginning of the JH4 intron, is indeed located within a highly mutated domain downstream of the CDR3 region that is a major focus of hypermutation. As a control, mutations were determined for each mouse line in 66 bp of flanking sequences (43 bp upstream and 23 bp downstream of the ClaI insertion site); this region displayed an average mutation frequency approximately 2-fold lower than that for the adjacent oligonucleotide transgene in all constructions (Table 1). Therefore, the high mutation frequencies of the different transgenes did not appear to be abnormal, considering the high density of Polη mutation hot spots they contained and which might be targeted efficiently once patch synthesis is initiated.

TABLE 1.

Relative mutation frequencies in oligonucleotide transgenes and adjacent JH4 sequences

| Transgenic mouse line | Age (mo) | Organb | JH4 intron mutations |

Transgene mutations |

Transgene/JH4 intron mutation ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. | Frequency (%) | Total no. | Frequency (%) | ||||

| Tg-noG | 2 | IPP | 25 | 0.84 | 92 | 2.42 | |

| 2 | IPP | 21 | 0.48 | 110 | 1.91 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 29 | 0.60 | 58 | 0.92 | ||

| 6 | Spleen | 37 | 0.63 | 127 | 1.60 | ||

| 6 | Spleen | 17 | 0.32 | 74 | 1.03 | ||

| 6 | Spleen | 20 | 0.40 | 64 | 0.81 | ||

| 6 | Spleen | 27 | 0.55 | 54 | 0.82 | ||

| Total | 176 (121 + 55)a | 579 | 2.41 | ||||

| Tg-noC | 5 | Spleen | 54 | 0.70 | 128 | 1.38 | |

| 10 | Spleen | 24 | 0.62 | 74 | 1.43 | ||

| Total | 78 (50 + 28)a | 202 | 1.90 | ||||

| Tg-G | 2 | IPP | 16 | 0.66 | 20 | 0.58 | |

| 2 | IPP | 10 | 0.49 | 43 | 1.26 | ||

| 2 | Spleen | 13 | 0.51 | 65 | 1.80 | ||

| 2 | Spleen | 8 | 0.39 | 35 | 1.06 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 21 | 0.77 | 85 | 2.18 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 20 | 0.89 | 47 | 1.53 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 20 | 0.80 | 80 | 2.32 | ||

| Total | 108 (73 + 35)a | 375 | 2.46 | ||||

| Tg-C | 2 | IPP | 62 | 1.71 | 250 | 5.07 | |

| 2 | IPP | 35 | 1.77 | 111 | 3.98 | ||

| 2 | Spleen | 13 | 0.36 | 40 | 0.84 | ||

| 2 | Spleen | 26 | 0.80 | 102 | 2.38 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 52 | 1.61 | 136 | 2.98 | ||

| 5 | Spleen | 25 | 0.74 | 95 | 3.10 | ||

| Total | 213 (122 + 91)a | 734 | 2.45 | ||||

| Tg-G × Ung KO | 2.5 | IPP | 17 | 0.68 | 72 | 2.04 | |

| 2.5 | IPP | 132 | 2.49 | 333 | 4.49 | ||

| 2.5 | IPP | 131 | 2.47 | 422 | 5.56 | ||

| Total | 280 (170 + 110)a | 827 | 2.10 | ||||

| Tg-C × Ung KO | 2 | IPP | 17 | 0.32 | 98 | 1.38 | |

| 2 | IPP | 71 | 1.56 | 183 | 2.91 | ||

| 2 | IPP | 19 | 0.51 | 54 | 1.09 | ||

| Total | 107 (65 + 42)a | 335 | 2.22 | ||||

Total numbers of mutations for the 66-bp JH4 sequence are divided (in parentheses) into numbers of mutations within the 43 bp and 23 bp flanking the transgene in the 5′ and 3′ directions, respectively.

IPP, intestinal Peyer's patches.

We divided the sequences analyzed into 2 categories, total sequences and sequences including 1 to 3 mutations, which could be considered a sample resulting from a single (or small number of) mutation hit (Table 2). Even within the 1- to 3-mutation sample, control transgenes harbored mutations throughout the 90-bp oligonucleotide, which precluded identification of a core region in which the impact of the 3 C's or G's could be assessed (Fig. 3). As discussed in the next section, the patch of DNA synthesis performed by Polη does indeed appear to exceed the length of the 90-bp A/T substrate.

TABLE 2.

Mutation distribution in various transgenic substrates

| Mutation | No. (%) of mutations |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg-noC/Tg-noG |

Tg-G/Tg-C |

Tg-G/Tg-C × Ung KO |

||||||||||

| Tg-noC, all mutations | Tg-noG, all mutations | Tg-noC, 1–3 mutations | Tg-noG, 1–3 mutations | Tg-C, all mutations | Tg-G, all mutations | Tg-C, 1–3 mutations | Tg-G, 1–3 mutations | Tg-C, all mutations | Tg-G, all mutations | Tg-C, 1–3 mutations | Tg-G, 1–3 mutations | |

| A to G | 68 (34.0) | 185 (32.3) | 34 (35.1) | 110 (34.5) | 239 (32.6) | 109 (29.3) | 55 (28.9) | 48 (26.8) | 93 (29.4) | 171 (24.2) | 45 (36.0) | 26 (21.3) |

| A to T | 57 (28.5) | 148 (25.9) | 30 (30.9) | 77 (24.1) | 177 (24.1) | 96 (25.8) | 58 (30.5) | 53 (29.6) | 62 (19.6) | 155 (21.9) | 16 (12.8) | 29 (23.8) |

| A to C | 34 (17.0) | 84 (14.7) | 17 (17.5) | 48 (15.0) | 118 (16.1) | 46 (12.4) | 33 (17.4) | 21 (11.7) | 39 (12.3) | 107 (15.1) | 16 (12.8) | 18 (14.8) |

| Total A mutations | 159 (79.5) | 417 (72.9) | 81 (83.5) | 235 (73.7) | 534 (72.8) | 251 (67.5) | 146 (76.8) | 122 (68.2) | 194 (61.4) | 433 (61.2) | 77 (61.6) | 73 (59.8) |

| T to C | 17 (8.5) | 71 (12.4) | 4 (4.1) | 38 (11.9) | 61 (8.3) | 44 (11.8) | 11 (5.8) | 15 (8.4) | 35 (11.1) | 95 (13.4) | 12 (9.6) | 15 (12.3) |

| T to A | 14 (7.0) | 48 (8.4) | 7 (7.2) | 28 (8.8) | 69 (9.4) | 33 (8.9) | 18 (9.5) | 11 (6.1) | 41 (13.0) | 76 (10.7) | 10 (8.0) | 14 (11.5) |

| T to G | 10 (5.0) | 36 (6.3) | 5 (5.2) | 18 (5.6) | 41 (5.6) | 22 (5.9) | 9 (4.7) | 11 (6.1) | 14 (4.4) | 53 (7.5) | 6 (4.8) | 7 (5.7) |

| Total T mutations | 41 (20.5) | 155 (27.1) | 16 (16.5) | 84 (26.3) | 171 (23.3) | 99 (26.6) | 38 (20.0) | 37 (20.7) | 90 (28.5) | 224 (31.6) | 28 (22.4) | 36 (29.5) |

| C to T, G to A | 11 (1.5) | 8 (2.2) | 4 (2.1) | 6 (3.4) | 32 (10.1) | 49 (6.9) | 20 (16.0) | 12 (9.8) | ||||

| C to A, G to T | 5 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) | 2 (1.1) | 8 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| C to G, G to C | 13 (1.8) | 9 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | ||||

| Total C/G mutations | 29 (4.0) | 22 (5.9) | 6 (3.2) | 20 (11.2) | 32 (10.1) | 51 (7.2) | 20 (16.0) | 13 (10.7) | ||||

| Total mutationsa | 200 | 572 | 97 | 319 | 734 | 372 | 190 | 179 | 316 | 708 | 125 | 122 |

Differences with Table 1 concerning total mutation numbers correspond to the elimination of mutations from clonally related sequences.

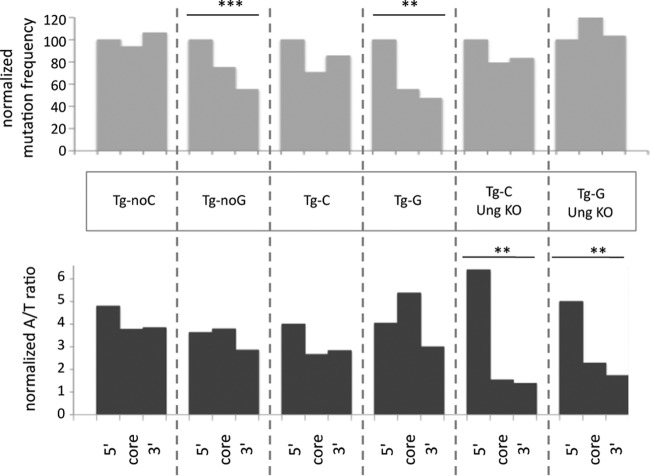

FIG 3.

Distributions of mutations and A/T ratios along the oligonucleotide sequence. Mutation frequencies (corrected for relative nucleotide length and normalized to 100 for the 5′ segment) and A/T ratios (corrected for relative A/T composition) are presented for sequences including 1 to 3 mutations and analyzed along the 3 segments of the oligonucleotide transgenes defined in Fig. 1: 5′ part, core segment, and 3′ part. Significant trends in 5′-to-3′ mutation distributions and A/T ratios are indicated (according to Cochran-Armitage and Jonckheere-Terpstra trend tests, respectively [see Materials and Methods]). **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. KO, knockout.

In vivo mutation profile of DNA polymerase η.

The control transgenes provide a unique opportunity to study the mutagenic properties of Polη in vivo, in the context of a balanced and symmetrical number of WA (TW) mutation hot spots not encountered in natural DNA templates. We collected 572 mutations for the Tg-noG line from 8 different mice, with 319 mutations in sequences in the 1- to 3-mutation range. For the Tg-noC control, no germ line transmission was obtained. Therefore, we examined 2 founder mice with high levels of chimerism (Table 2).

Mutation distributions were analyzed along the 90 bp of Tg-noC and Tg-noG templates, and the results were grouped into 3 different segments to represent mutation samples of sufficient size: the 5′ part, corresponding to the first 3 repeats; the 3′ part, corresponding to the last 3 repeats; and the core region, corresponding to the internal 4 repeats (i.e., a region including 1 repeat on each side of the central C's and G's in the Tg-C and Tg-G constructs) (Fig. 1). Mutation frequencies were corrected for the sequence length of each segment and for the base composition of each transgene in case of mutation at A's or T's, with the Tg-noC construct displaying, as mentioned above, 5 A's and 4 T's in each repeat and the Tg-noG construct displaying the reverse base composition.

In the case of Tg-noC, the distribution of mutations in the 1- to 3-mutation sequence sample was regular throughout the sequence length, whereas the Tg-noG template showed a significant decline toward the 3′ part but still with a high mutation load up to the 3′ end (Fig. 3). The trend was similar when all sequences were analyzed, so the difference was not due to the smaller mutation sample size for Tg-noC (data not shown). We tested whether this mutation decrease could be due to cryptic polyadenylation sites generated in these A/T-rich sequences in the specific orientation of the G/noG transgene, which would interrupt transcription and affect mutation targeting. First, we estimated the relative mutation frequencies in 5′ and 3′ flanks of the oligonucleotide insertion site for both constructs, and second, we estimated the relative transcript abundances upstream and downstream of the oligonucleotide (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Both analyses failed to detect any consistent 5′-to-3′ bias between the G/noG and C/noC constructs. The difference observed in mutation distribution may therefore correspond to differences in the secondary structure adopted by the two oligonucleotides, which would affect elongation of Polη DNA synthesis.

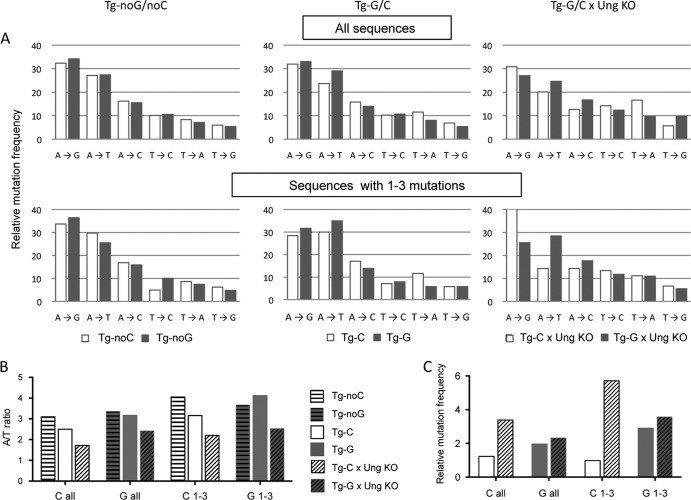

We further analyzed the A/T mutation ratio along the three segments of the oligonucleotides and observed similar values for both control transgenes, which indicates a constant strand bias over the 90-nt substrate. The average A/T ratio on the complete sequence was quite high: about 4 for both Tg-noC and Tg-noG (about 3 when all mutated sequences were considered) (Fig. 3 and 4B). This strand bias is approximately twice as high as that observed at the Ig locus. The mutation pattern was accordingly biased toward A-to-G, A-to-T, and A-to-C mutations, with decreasing frequencies, with A to G being the most prevalent mutation. Complementary mutations at T bases were approximately 3- to 4-fold lower (Fig. 4A). This mutation pattern differs from that observed in vitro: because A-to-G mutation predominated, one would expect T-to-A mutation to be the second most frequent mutation. Nevertheless, the mutation pattern mirrors that at the Ig locus in vivo, which shows a similar bias, although less pronounced, with prevalent mutations at A's showing the same decreasing frequencies from G, T, and C and a 2-fold difference for complementary mutations at T positions (from C, A, and G).

FIG 4.

Mutation profiles at A/T and G/C bases for the different oligonucleotide substrates. (A) Distributions of mutations are presented for each transgenic substrate, analyzed in 2 categories: total sequences and sequences with 1 to 3 mutations over the 90- or 93-bp oligonucleotide template, corrected for base composition. (B) Average A/T mutation ratios for the different transgenes. (C) Relative mutation frequencies at C's and G's versus the A/T backbone in wild-type (wt) and Ung-deficient (KO) contexts (corrected for their 30-fold lower representation level).

WA has been described as the main Polη hot spot at the Ig locus in vivo. When corrected for its frequency within the oligonucleotide, TA was mutated twice as frequently as AA, whether in the TAA or TAT motif (Fig. 5A). As reported by Spencer and Dunn-Walters, the trinucleotide context of the mutated base appears to affect the type of mutation generated (17). Because of its peculiar sequence, our transgene provides only 3 trinucleotide contexts for considering mutations at A bases: AAT, TAA, and TAT (and the reverse, ATT, TTA, and ATA, for mutations at T's). A-to-T mutations appear to be specifically disfavored in the TAA context, and the same holds true for the reverse-complement motif TTA, an effect apparently contributed by both the 5′- and 3′-flanking bases (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Symmetrical targeting of WA and TW motifs. (A) Mutations were analyzed for each 3-nt context, with reference to the central mutated position. (B) The distribution of mutation outcomes at the central nucleotide position is represented for each 3-nt context. Analysis of mutations was restricted to Tg-noG, for which a larger database was assembled.

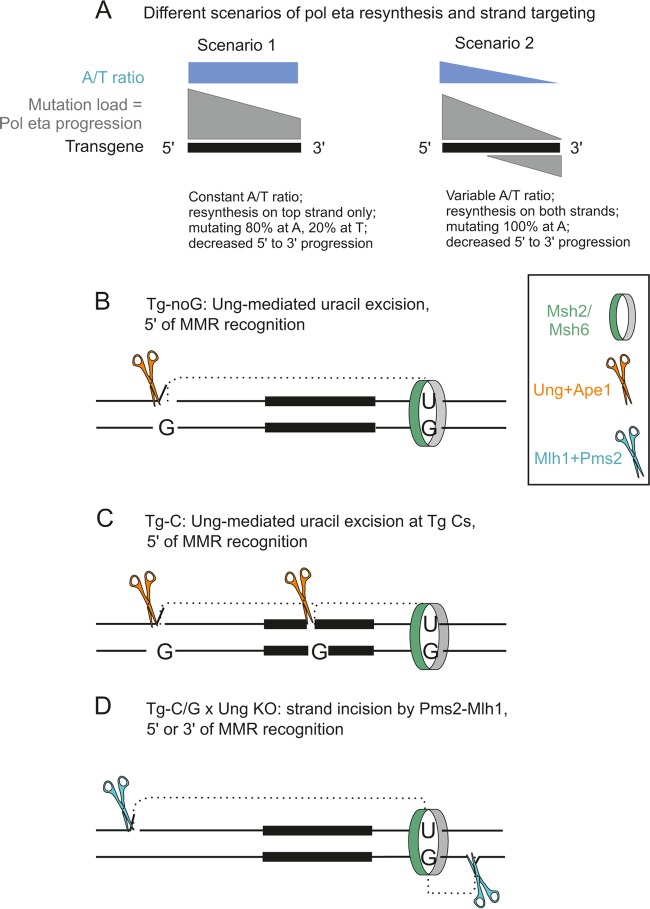

We observed a reverse complementarity for the overall A and T mutation motifs in terms of relative hot spot frequency and nucleotide context. This observation could be interpreted in two ways. First, Polη could be mutagenic when copying T only (or with several orders of magnitude of nucleotide incorporation infidelity), with the 4-fold ratio observed corresponding to the relative proportion of synthesis of each DNA strand (i.e., 80% for the nontranscribed strand and 20% for the transcribed strand). Alternatively, Polη could be targeted to synthesize the nontranscribed strand only, with a 4-fold higher mutation frequency when copying T's than when copying A's. The mutation profile of Tg-noC (a constant distribution of mutations and a constant A/T ratio along the sequence) does not allow discrimination between these two propositions. In contrast, the mutation pattern of Tg-noG is compatible with only the second possibility: indeed, the distribution shows a 5′-to-3′ gradient in mutation frequency while keeping the A/T ratio fairly constant over the whole 90-nt template, thus precluding a contribution in the reverse direction that would markedly bias mutations toward T's on the 3′ side (Fig. 6A and B). Therefore, our transgenic substrate is targeted mostly on the top strand, with a patch of Polη synthesis that is initiated by a DNA break in the 5′ flank of the oligonucleotide transgene and that can proceed over its total length and even extend beyond its 3′ end.

FIG 6.

Putative scheme of Ung/Pms2 strand targeting at the A/T oligonucleotide substrate. (A) Schematic of the impact on A/T mutagenesis of the two possible Polη synthesis profiles accounting for the observed A/T ratio of 4. Scenario 1, an 80%-20% A/T mutation profile for top-strand synthesis; scenario 2, a 100% A mutation profile, with 80% of synthesis on the top strand and 20% on the bottom strand. Only the first proposition corresponds to the pattern observed in Tg-noG, with the profile of mutations for Tg-noC (not represented) being compatible with both (Fig. 3). (B) Ung-triggered DNA incision at uracils (represented by orange scissors) is proposed to cooperate with U-G mismatch recognition by Msh2/Msh6 to promote initiation of Polη-mediated error-prone DNA synthesis at the generated nicks (18). Nearby deamination events are more likely to occur on the nontranscribed, exposed strand. (C) Initiation of DNA synthesis at internal C's of the Tg-C substrate triggered by Ung, accounting for the reduced C mutation frequency in the wt versus the Ung-deficient background (Fig. 4C). (D) Reduced A/T ratio in the Ung−/− context due to a more moderate strand bias of the noncanonical mismatch repair involving the Pms2-Mlh1 endonuclease activity (blue scissors). The recruitment of the complete mismatch repair complex (MutSα and MutLα) is proposed to be the default pathway at the Ig locus, but Ung would take over and provide abasic sites triggering DNA incision in the specific location of the oligonucleotide substrate or in a Pms2-deficient context (see Discussion). MMR, mismatch repair.

Strand bias reversed by Ung deficiency: a role for the complete mismatch repair complex.

When the mutation profiles of Tg-G and Tg-C are confronted with that of their A/T-only backbone, no major differences are observed in terms of mutation distribution along the sequence, A/T ratio, or mutation pattern. G's and C's are clearly targeted by AID, but their capacity to trigger an Msh2-driven repair process thus appears to be minor compared with the contribution of sites external to the sequence.

The Tg-G and Tg-C lines were bred into an Ung−/− background to more clearly isolate mutations contributed by the Msh2-Msh6 pathway. The most striking alteration was a diminution in the overall A/T bias, to ratios of 2.5 and 2.2 for Tg-G and Tg-C, respectively. This reduction was strikingly more pronounced in the 3′ part of the oligonucleotide template (Fig. 3). Ung deficiency thus promoted the alternate use of entry points 3′ to the oligonucleotide transgene, triggering Polη synthesis in the reverse orientation. Nevertheless, this reverse patch synthesis appears to be shorter than that initiated from the 5′ flank, because the 5′ segment conserves a high A/T ratio (Fig. 3).

Uracil glycosylase can trigger error-free repair of uracils at the Ig locus, at a frequency that is still debated but which represents only a fraction of the deamination events leading to mutations at G/C bases. Such error-free processing involves the incision of the DNA chain and has been proposed to provide an entry point for Mhs2-Msh6-driven long-patch DNA synthesis (18). This process, which requires the simultaneous formation of 2 nearby uracils, is more likely to take place in regions highly targeted for mutation and on the nontranscribed strand exposed during RNA polymerase II elongation. In its absence, the Pms2-Mlh1 endonuclease could provide nicks in DNA with a looser strand bias, typically associated with a noncanonical mismatch repair process that lacks directionality (19) (see Discussion). Our observations may provide the first set of data supporting this proposition, even though they pertain to an artificial substrate. Indeed, we interpret the strand bias observed in our transgenes as being generated by a uracil glycosylase-induced incision 5′ of the oligonucleotide transgene, coincident with recognition by the Msh2-Msh6 complex of another, downstream deamination event in this highly mutated region of the Ig locus and promoting a long patch of Polη mutagenic synthesis. In the uracil glycosylase-deficient context, access to the transcribed strand would be provided by Mlh1-Pms2, thus reequilibrating the A/T ratio toward values observed in Ig genes in vivo (Fig. 6D).

An additional difference observed in the Ung-deficient background concerns the targeting of the G and C bases. We evaluated the mutation frequency at these 3 bases compared to the rest of the transgene, corrected for their representation (3 G/C bases for 90 A/T bases, i.e., a ratio of 30 for A/T bases). G's were mutated 3-fold more than the neighboring A/T bases in both the wild-type (wt) and Ung−/− contexts for sequences with 1 to 3 mutations. C's were slightly more mutated than G's in the Ung−/− background, which confirms an efficient targeting of both DNA strands. However, in contrast, mutations at C's were 5 times less frequent in wild-type than Ung−/− animals (Fig. 4C). This observation can be interpreted again as error-free repair coupled with U/G mismatch recognition, providing entry sites within the transgene and favored, as for external incisions, on the nontranscribed strand (Fig. 6C). However, the overall mutation number at G/C bases is too small to affect the global A/T mutation pattern, which precludes the assessment of a differential effect between the Tg-C and Tg-G configurations that was initially intended in the design of the transgenes.

Increased strand bias of A/T mutations in Pms2-deficient background.

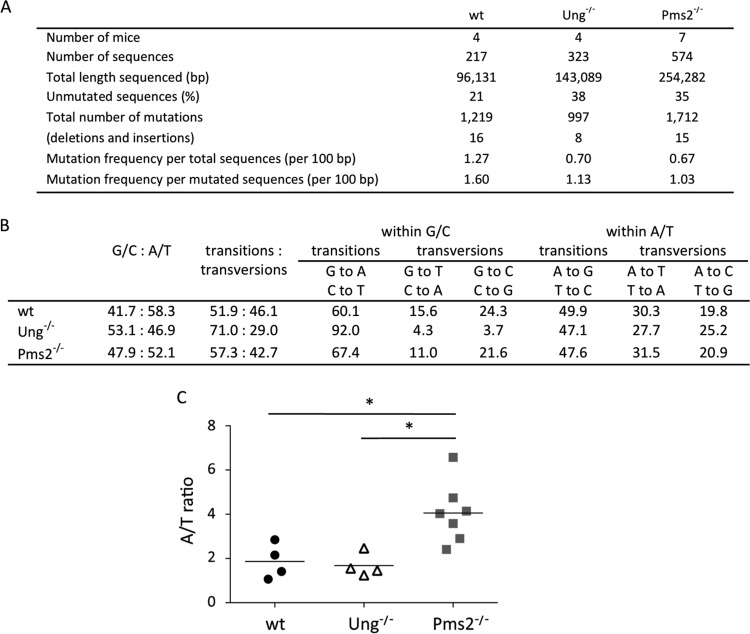

Pms2 or Mlh1 inactivation has previously been reported to have no discernible impact on somatic hypermutation, which suggests that the MutLα complex is not involved in triggering MutSα-driven error-prone repair. However, these data are based on small mutation samples, or their analysis involved tools that diminish the contribution of recurrent hot spot mutations (see Discussion). Therefore, we readdressed the question of a possible role of MutLα by generating a large mutation database from both Pms2- and Ung-deficient, nontransgenic animals (Fig. 7). The most obvious difference between the wild-type and Pms2−/− patterns was the large increase in the A-over-T mutation ratio, which reached an average value of 4 (Fig. 7C). No such bias was observed in Ung−/− mice. As for the transgene in the Ung-deficient background, this finding suggests that the MutLα complex is the main contributor of the endonuclease incision required for initiation of Polη synthesis, an incision with a more moderate strand bias. In its absence, Ung would compensate for this function, with a heavier bias toward the nontranscribed strand, in which multiple deamination events might be more likely to occur.

FIG 7.

A/T bias linked with Pms2 deficiency. (A) Analysis of mutations in JH4 intronic sequences from wt, Ung−/−, and Pms2−/− mice. (B) Mutation profiles of wt, Ung−/−, and Pms2−/− mice. (C) A-over-T mutation ratios. *, P = 0.012 (two-tailed Mann-Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

We report here the analysis of oligonucleotide mutation substrates, inserted by knock-in at the IgH locus, to study the strand bias characteristics of the MutSα-driven error-prone repair synthesis taking place during somatic hypermutation in germinal-center B cells. This mechanism represents the major developmental process during which the outcome of Polη-catalyzed synthesis on undamaged DNA templates can be assessed.

These oligonucleotide substrates consisted of 10 repeated motifs of the TATTATTAA 9-mer, inserted in both orientations and including or not including G's and C's in the central part. They were initially designed to determine the impact on strand choice of the error-prone DNA synthesis process of AID targets embedded in a 90-bp backbone of alternate WA hypermutation hot spots, with substrates lacking such G/C internal entry points as controls. Surprisingly, both G/C and control substrates were similarly targeted, so the internal sites failed to add significantly to the mutations generated by the vigorous error-prone synthesis promoted by the flanking sequences. The substrates were indeed inserted downstream of the JH4 segment (i.e., in a genomic region flanking CDR3 and highly targeted for hypermutation), which may account for the unexpected inefficiency of the AID hot spots that were designed.

The control substrates allowed us to define the Polη misincorporation profile on targets offering a symmetrical distribution of WA and TW motifs. Mutations were 4 times more frequent at A's than at T's, with decreased frequencies of mutations from A to G, A to T, and A to C. Reverse complementarity was observed for the mutation pattern at T's. This is in marked contrast to the Polη error specificity determined in vitro: if G misincorporation opposite a T is the most frequent error, then the second most frequent error is an A opposite an A (15, 16). We ensured that this difference was not due to the biased nucleotide composition of our transgene by establishing its mutation profile when copied in vitro by Polη and found the same types of errors as those reported in other in vitro studies. The contribution of Polη during hypermutation in vivo obviously takes place in a different context, involving factors such as monoubiquitinated PCNA, whose role is not reproduced in in vitro assays and which may notably affect its processivity and mutagenicity (7).

The whole 90-bp length of the A/T mutation substrates appeared to be targeted along a repair patch initiated in the flanking region. Although both substrates devoid of G/C (Tg-noG and Tg-noC) behaved slightly differently, Tg-noG displayed an informative pattern: the mutation frequency decreased 2-fold between the 5′ and 3′ sides of the 90-bp substrate, while the A/T ratio remained constant, at about 4. This finding can only be interpreted as the result of a synthesis initiated mostly from the 5′ flank, because a decreasing progression from the 5′ to the 3′ end and a synthesis of the transcribed strand initiated from the 3′ side would obviously affect the A/T ratio according to the relative contribution of synthesis proceeding from each side (Fig. 6). Therefore, our control transgenes reveal that the Polη misincorporation profile corresponds to a synthesis of the nontranscribed strand, a configuration possibly resulting from their specific location and specific base composition. Accordingly, this represents a surprisingly long patch of DNA, exceeding 90 bases, which can be copied by Polη from a single initiation event. The 2-fold A-over-T bias observed in vivo in Ig genes would thus result from an error-prone synthesis proceeding in an approximately 3-to-1 ratio on the nontranscribed and transcribed strands, respectively. This ratio can result from an inequality in frequencies of initiation between the strands, a shorter length of the patch synthesized on the transcribed strand, or a combination of both.

The second observation contributed by these mutation substrates pertains to the question of the still elusive activity that triggers DNA incision after recognition of the U-G mismatch by the MutSα complex. Jiricny and colleagues proposed that incision at the abasic sites generated by uracil glycosylase may provide such nicks in a configuration whereby two nearby uracils (tested within 300 bp) are generated and processed: the 5′ one would provide a site of incision after Ung-mediated uracil excision, which would allow exonucleolytic processing with 5′-to-3′ directionality, triggered by Msh2-Msh6 bound to the 3′ U-G mismatch (18). The relevance of this proposition can be questioned, because Ung deficiency has a limited impact on A/T mutagenesis (4). Moreover, whereas multiple deaminations have been described for the switch regions that harbor a high density of AID hot spots (20), simultaneous deamination events around the V region are infrequent and possibly restricted to the most highly targeted regions along the transcription bubble that provides accessibility to AID.

Our transgenic substrates provide the first experimental support for this proposition. Indeed, they appear to be targeted for A/T mutagenesis exclusively from nicks introduced in the 5′ flanks of the transgene and generating a 4-fold A-over-T mutation ratio reflecting the intrinsic error spectrum of Polη. In contrast, when backcrossed into an Ung-deficient background, these transgenes showed a reduced A/T mutation ratio, with a marked decrease toward the 3′ end, which reflects a synthesis initiated from the 3′-flanking sequence and proceeding over a shorter distance in the reverse orientation. Our interpretation of these striking changes is the involvement of the endonuclease activity of the MutLα complex acting instead of Ung and generating a less-pronounced strand bias, as anticipated for a mismatch repair process acting outside replication and lacking the directionality provided by the discontinuities of the replication fork (19).

As for Ung, Pms2 and Mlh1 deficiencies have been reported to have no impact on A/T mutagenesis (9). More recent data, obtained using catalytic knock-in mutants, further addressed the specific contribution of the endonuclease activity of Pms2 and did not report any major impact of its inactivation on Ig gene hypermutation (21). However, the specific analysis performed may preclude monitoring of subtle changes, first because of the multiplicity of the templates analyzed and the predominance of mutations collected in a functional, selected VH sequence. Second and more importantly, mutations were analyzed by use of the SHMTool program, which records only a single mutation of each type at each nucleotide position (22). Such an analysis will obviously reduce the contribution of recurrent changes observed at mutation hot spots.

We generated a new mutation database from JH4 intronic sequences from Pms2-deficient B cells and revealed a marked A/T strand bias, with a ratio of 4, which suggests, as for the transgene, that the DNA incision which promotes A/T mutagenesis may be provided mainly by Ung and targeted to the nontranscribed strand. Therefore, the absence of an impact of single Pms2 or Ung deficiencies on the A/T mutation frequency would be explained by the reciprocal backup they exert on each other. The function of the MutLα complex may predominate at the natural Ig locus, whereas Ung appears to be the primum movens in the transgene context, possibly due, as mentioned above, to its specific location and/or base composition.

Our transgenic substrates thus allowed a thorough description of the profile of Polη-mediated mutagenesis, showing a long patch size and a mutation profile distinct from that described for in vitro assays. Interestingly, a Polη signature was recently defined for cancer cell lines, predominantly B-cell lymphomas (23), and comparing it with the profile described in this study would be of interest. Together with the analysis of mutations in the Pms2-deficient background, our transgenes also allowed us to propose a mutual backup function between Ung and MutLα in the DNA incision step promoting A/T mutagenesis, with a distinct strand preference. It remains to be studied whether other glycosylases capable of recognizing U-G mispairs, such as thymidine glycosylase, Smug1, or MBD4, may similarly contribute redundantly to this function. Combined gene inactivations will be required to establish the complete panel of enzymatic activities that can participate in the targeting of this error-prone repair process.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the SEAT (Villejuif, France) for its expertise in generation of ES-derived mouse lines and mouse breeding. We thank Deborah Barnes and Michael Liskay for providing Ung−/− and Pms2−/− mice, respectively. We thank Jérôme Mégret (Cytometry core facility of the Structure Fédérative de Recherche Necker) for cell sorting.

The Développement du Système Immunitaire team is supported by the Ligue contre le Cancer (Équipe Labelisée) and the Fondation Princesse Grace. Marija Zivojnovic was supported by a 3-year allocation from the Ecole Normale Supérieure and by the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer for her fourth year of Ph.D. research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 April 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01452-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Muramatsu M, Kinoshita K, Fagarasan S, Yamada S, Shinkai Y, Honjo T. 2000. Class switch recombination and hypermutation require activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), a potential RNA editing enzyme. Cell 102:553–563. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Revy P, Muto T, Levy Y, Geissmann F, Plebani A, Sanal O, Catalan N, Forveille M, Dufourcq-Labelouse R, Gennery A, Tezcan I, Ersoy F, Kayserili H, Ugazio AG, Brousse N, Muramatsu M, Notarangelo LD, Kinoshita K, Honjo T, Fischer A, Durandy A. 2000. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) deficiency causes the autosomal recessive form of the hyper-IgM syndrome (HIGM2). Cell 102:565–575. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00079-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rada C, Di Noia JM, Neuberger MS. 2004. Mismatch recognition and uracil excision provide complementary paths to both Ig switching and the A/T-focused phase of somatic mutation. Mol. Cell 16:163–171. 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rada C, Williams GT, Nilsen H, Barnes DE, Lindahl T, Neuberger MS. 2002. Immunoglobulin isotype switching is inhibited and somatic hypermutation perturbed in UNG-deficient mice. Curr. Biol. 12:1748–1755. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01215-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen JG, Langerak P, Tsaalbi-Shtylik A, van den Berk P, Jacobs H, de Wind N. 2006. Strand-biased defect in C/G transversions in hypermutating immunoglobulin genes in Rev1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 203:319–323. 10.1084/jem.20052227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delbos F, Aoufouchi S, Faili A, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. 2007. DNA polymerase eta is the sole contributor of A/T modifications during immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J. Exp. Med. 204:17–23. 10.1084/jem.20062131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langerak P, Nygren AO, Krijger PH, van den Berk PC, Jacobs H. 2007. A/T mutagenesis in hypermutated immunoglobulin genes strongly depends on PCNAK164 modification. J. Exp. Med. 204:1989–1998. 10.1084/jem.20070902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weill JC, Reynaud CA. 2008. DNA polymerases in adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:302–312. 10.1038/nri2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahwan R, Edelmann W, Scharff MD, Roa S. 2011. Mismatch-mediated error prone repair at the immunoglobulin genes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 65:529–536. 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unniraman S, Schatz DG. 2005. Strand-biased spreading of mutations during somatic hypermutation. Science 317:1227–1230. 10.1126/science.1145065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres R, Kühn R. 1997. Laboratory protocols for conditional gene targeting. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delbos F, De Smet A, Faili A, Aoufouchi S, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. 2005. Contribution of DNA polymerase eta to immunoglobulin gene hypermutation in the mouse. J. Exp. Med. 201:1191–1196. 10.1084/jem.20050292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochran W. 1954. Some methods for strengthening the common chi-squared tests. Biometrics 10:417–451. 10.2307/3001616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollander M, Wolfe D. 1999. Wiley series in probability and statistics. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuda T, Bebenek K, Masutani C, Rogozin IB, Hanaoka F, Kunkel TA. 2001. Error rate and specificity of human and murine DNA polymerase eta. J. Mol. Biol. 312:335–346. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlov YI, Rogozin IB, Galkin AP, Aksenova AY, Hanaoka F, Rada C, Kunkel TA. 2002. Correlation of somatic hypermutation specificity and A-T base pair substitution errors by DNA polymerase eta during copying of a mouse immunoglobulin kappa light chain transgene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:9954–9959. 10.1073/pnas.152126799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer J, Dunn-Walters DK. 2005. Hypermutation at A-T base pairs: the A nucleotide replacement spectrum is affected by adjacent nucleotides and there is no reverse complementarity of sequences flanking mutated A and T nucleotides. J. Immunol. 175:5170–5177. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schanz S, Castor D, Fischer F, Jiricny J. 2009. Interference of mismatch and base excision repair during the processing of adjacent U/G mispairs may play a key role in somatic hypermutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:5593–5598. 10.1073/pnas.0901726106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pena-Diaz J, Bregenhorn S, Ghodgaonkar M, Follonier C, Artola-Boran M, Castor D, Lopes M, Sartori AA, Jiricny J. 2012. Noncanonical mismatch repair as a source of genomic instability in human cells. Mol. Cell 47:669–680. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xue K, Rada C, Neuberger MS. 2006. The in vivo pattern of AID targeting to immunoglobulin switch regions deduced from mutation spectra in msh2−/− ung−/− mice. J. Exp. Med. 203:2085–2094. 10.1084/jem.20061067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Oers JM, Roa S, Werling U, Liu Y, Genschel J, Hou H, Jr, Sellers RS, Modrich P, Scharff MD, Edelmann W. 2010. PMS2 endonuclease activity has distinct biological functions and is essential for genome maintenance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13384–13389. 10.1073/pnas.1008589107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maccarthy T, Roa S, Scharff MD, Bergman A. 2009. SHMTool: a webserver for comparative analysis of somatic hypermutation datasets. DNA Repair (Amst) 8:137–141. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL, Boyault S, Burkhardt B, Butler AP, Caldas C, Davies HR, Desmedt C, Eils R, Eyfjord JE, Foekens JA, Greaves M, Hosoda F, Hutter B, Ilicic T, Imbeaud S, Imielinsk M, Jager N, Jones DT, Jones D, Knappskog S, Kool M, Lakhani SR, Lopez-Otin C, Martin S, Munshi NC, Nakamura H, Northcott PA, Pajic M, Papaemmanuil E, Paradiso A, Pearson JV, Puente XS, Raine K, Ramakrishna M, Richardson AL, Richter J, Rosenstiel P, Schlesner M, Schumacher TN, Span PN, Teague JW, Totoki Y, Tutt AN, Valdes-Mas R, van Buuren MM, van't Veer L, Vincent-Salomon A, Waddell N, Yates LR, Zucman-Rossi J, Futreal PA, McDermott U, Lichter P, Meyerson M, Grimmond SM, Siebert R, Campo E, Shibata T, Pfister SM, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. 2013. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500:415–421. 10.1038/nature12477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.