Abstract

Phosphorylation at the highly conserved serine residues S23 to S25 in the nuclear export protein (NEP) of influenza A viruses was suspected to regulate its nuclear export activity or polymerase activity-enhancing function. Mutation of these phosphoacceptor sites to either alanine or aspartic acid showed only a minor effect on both activities but revealed the presence of other phosphoacceptor sites that might be involved in regulating NEP activity.

TEXT

The 14-kDa nuclear export protein (NEP) of influenza A viruses is an indispensable factor for the nuclear export of newly synthesized viral ribonucleoprotein complexes (vRNPs) (1). The “daisy-chain” model suggests that NEP functions as an adaptor protein connecting the viral matrix protein M1, which is associated with the vRNP, to the cellular exportin CRM1 (2). While the C terminus of NEP facilitates M1 binding, two N-terminal nuclear export signals (NES) mediate CRM1 interaction (1, 3). NEP, in addition to its role in vRNP export, functions also as a regulatory cofactor of the viral polymerase (4–7). Avian H5N1 viruses seem to depend on the acquisition of adaptive mutations in NEP for efficient replication in mammalian cells and mice (8). We could recently assign the underlying polymerase-enhancing function of NEP to its C terminus, which alone is sufficient to significantly increase polymerase activity in human cells (9). NEP was also shown to be phosphorylated in virus-infected cells (10), and specific phosphoacceptor sites could recently be mapped (Fig. 1A) to three highly conserved serine residues (S23, S24, and S25) by mass spectrometry (11). While it is unclear which of these 3 serine residues are actually phosphorylated (11), it was suggested that phosphorylation at these sites may regulate the activity of NEP in the cell nucleus (8, 9, 11). Since NEP is required for both nuclear export of vRNPs and stimulation of the viral polymerase activity, phosphorylation might regulate one or both of these activities.

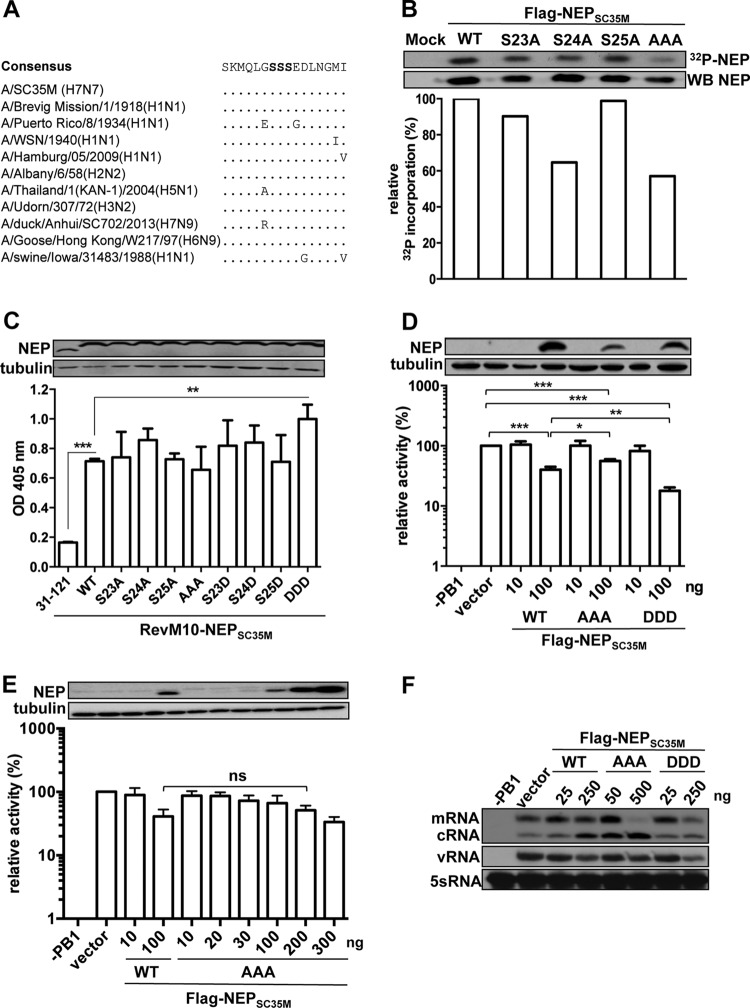

FIG 1.

Functional analysis of the major phosphoacceptor site (S23 to S25) of NEP in vitro. (A) Alignment of amino acids 17 to 32 of selected influenza A virus isolates. The conserved serine residues 23 to 25 are bolded. (B) Phosphorylation of Flag-tagged NEPSC35M and the indicated mutants. The NEP proteins were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells, 32P labeled, precipitated, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The upper panel depicts an autoradiography of radioactive 32P-labeled NEP and the corresponding levels of NEP detected by NEP-specific antibodies. The bar graph represents the relative radioactive signal normalized to total NEP levels. (C) CRM1-dependent export activity of RevM10-NEP fusion proteins. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids coding for the indicated NEP mutants fused to the export-inactive Rev protein (RevM10) and plasmids coding for an intron-containing CAT reporter mRNA harboring a Rev response element. RevM10-NEP31–121 lacking the two NESs served as a negative control. Protein levels of the NEP fusion proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Export activity was determined by measuring CAT protein levels in the cell lysates by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Error bars indicate standard deviations from three independent experiments. Student's t test was performed to determine the P value. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D and E) Effect of the indicated NEPSC35M variants on SC35M polymerase activity. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids coding for PB2, PB1, PA, and NP, a human polymerase I-driven vRNA firefly luciferase reporter plasmid, a renilla-expressing plasmid, and the indicated concentrations of Flag-tagged NEP. Omission of PB1 (−PB1) was used as a negative control. To address variations in transfection efficiency, firefly luciferase reporter activity was normalized to the renilla signal. Polymerase activity in the absence of NEP was set to 100%. Standard deviation was calculated from three independent experiments. Student's t test was performed to determine the P value. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.00; ns, nonsignificant. (F) Primer extension analysis to visualize viral RNA species synthesized by a reconstituted SC35M polymerase using segment 6 as the template in the presence of the indicated amounts of NEPSC35M variants. Determination of 5S RNA levels served as the internal loading control.

To determine the contribution of each of the three serine residues to overall NEP phosphorylation, we expressed N-terminally Flag-tagged NEPs of A/SC35M (H7N7) harboring either single or triple serine-to-alanine mutations (S23A, S24A, S25A; AAA) in HEK293T cells. After 20 h, cells were incubated for a further 4 h in the presence of 32P-orthophosphate, and NEP was immunoprecipitated by Flag-specific antibodies as described previously (12). Determination of the phosphorylation status by autoradiography and normalization to total NEP levels determined by Western blotting revealed that substitution of serine 24 resulted in a decrease of phosphorylation to 65% of the wild-type NEP (Flag-NEPSC35M_WT) levels, while substitution of serine 23 or 25 led only to a minor decrease (Fig. 1B). Moreover, phosphorylation of Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA was reduced to 59% compared to that of WT NEP (Fig. 1B). These results confirm that residues 23 to 25 represent a major phosphoacceptor site of NEP and further suggest that primarily serine 24 is phosphorylated.

To investigate whether phosphorylation at S23 to S25 is required for the export function of NEP, we subjected the serine-to-alanine mutants to a Rev-dependent export assay as recently described (9). For this purpose, we transiently expressed the respective NEP mutants fused to a CRM1-binding-deficient variant of HIV-Rev (RevM10) in HEK293T cells. In addition, we transiently transfected a plasmid (pDM128) (13) to provide chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT)-encoding mRNAs that harbor the Rev response element (RRE). Determination of CAT levels, which are an indirect measure of NEP-CRM1 interaction, revealed that neither the single serine-to-alanine mutants nor the triple alanine mutant shows altered export activity (Fig. 1C). As expected, CAT levels were higher in the presence of RevM10 fused to WT SC35M NEP than to a fusion protein lacking the NES-containing N-terminal 30 amino acids of NEP (Fig. 1C). Substitution of serine residues with aspartic acids (D) is known to mimic phosphorylated amino acids due to their charge and size (14, 15). To test the influence of NEP phosphorylation on its export activity, we analyzed NEP mutants with S-to-D substitutions (S23D, S24D, S25D; DDD) in our nuclear export assay. No change in CAT levels was observed with the single S-to-D substitutions, while the reporter levels were significantly increased with the triple-D mutant protein (Fig. 1C). This suggests that nuclear export of NEP might be regulated by phosphorylation.

To analyze whether the phosphorylation status of NEP influences its regulatory function on the viral polymerase, we reconstituted the SC35M polymerase as described previously (9) in human 293T cells in the presence of either small amounts (100 ng/12 wells) or large amounts (1,000 ng/12 wells) of Flag-NEPSC35M_WT, Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA, or Flag-NEPSC35M_DDD and measured its activity employing a minigenome from which a luciferase-encoding mRNA is transcribed (9). Consistent with other reports that the polymerases activity of human-adapted influenza A viruses is hardly affected by low concentrations of NEP (6), small amounts of the tested NEPs did not enhance the polymerase activity of the mammalian-adapted SC35M polymerase (Fig. 1D). However, expression of larger amounts of WT or mutant NEP significantly inhibited viral polymerase activity compared to the vector control. While polymerase activity was reduced to 40% of the vector control in the presence of Flag-NEPSC35M_WT, expression of Flag-NEPSC35M_DDD resulted only in a decrease up to 20%. Due to lower expression levels of Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA, we transfected increasing plasmid amounts to reach wild-type NEP levels. As shown in Fig. 1E, similar or even higher levels of Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA resulted in inhibition of the polymerase activity comparable to that of Flag-NEP. These results suggest that phosphorylation of S23 to S25 does not substantially alter the polymerase cofactor activity of NEP. By reconstitution of the SC35M polymerase using an authentic viral segment (segment 6) and visualization of the three viral RNA species by primer extension analysis as described previously (6), we could show that coexpression of large amounts of Flag-NEPSC35M results in an increase of cRNA levels and a decrease of vRNA levels (Fig. 1F). Although large amounts of Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA also led to a pronounced increase in cRNA levels, mRNA was significantly decreased. Compared to Flag-NEPSC35M, expression of high levels of Flag-NEPSC35M_DDD resulted in a decrease of all viral RNA species. Together, this suggests that the phosphorylation status of NEP might have an effect on the relative ratio of viral transcript levels.

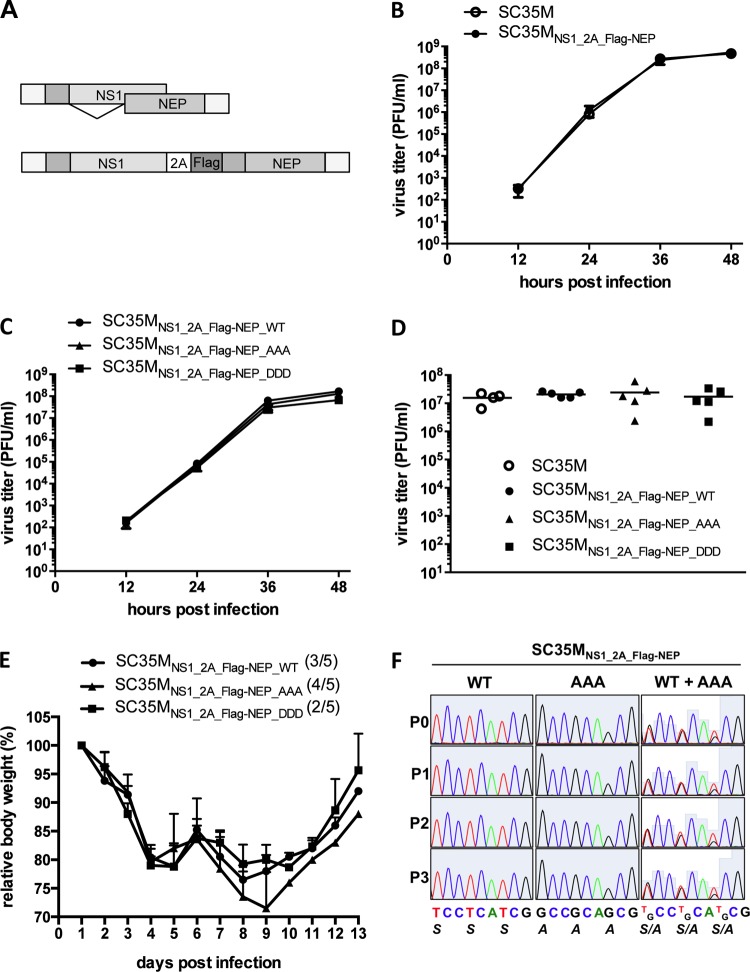

To investigate the effect of NEP phosphorylation on viral growth, we generated a pHW2000 (16)-based rescue plasmid (NS1_2A_Flag-NEP) from which a modified segment 8 is transcribed, discretely encoding the nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) and Flag-tagged NEP. To achieve this, NS1 and NEP open reading frames were separated by the PTV-1-2A peptide coding sequence (17) (Fig. 2A). This strategy allows the introduction of any mutation into NEP without altering NS1. Both recombinant viruses, WT SC35M and SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP, show comparable growth in human lung-derived A549 cells, indicating that artificial separation of the NS1 and NEP open reading frames does not affect viral replication (Fig. 2B). Importantly, both SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_AAA and SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_DDD (Fig. 2C) replicated in A549 cells as efficiently as WT SC35M, suggesting that phosphorylation of NEP at S23 to S25 is not required for viral growth in cell culture. Sequencing 48 h postinfection confirmed that all viruses harbored their respective mutated NEP. To analyze propagation of these viruses in vivo, BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with 1,000 PFU, and viral lung titers were determined 40 h postinfection. Similar to what we observed in cell culture, all tested viruses grew to comparable titers in the infected animals (Fig. 2D). Moreover, weight loss and mortality of BALB/c mice intranasally infected with 1,000 PFU of the respective viruses were comparable (Fig. 2E), indicating that phosphorylation of NEP at S23 to S25 is not essential for influenza virus replication in cell culture and in vivo. To investigate whether the absence of phosphorylation at S23 to S25 would represent a subtle disadvantage in a competitive setting, we coinfected A549 cells with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 of both SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_WT and SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_AAA and repeatedly passaged the viruses after 48 h (Fig. 2F). Sequencing of the NS segment after each passage revealed that SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_WT could not outcompete SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_AAA in the course of this experiment.

FIG 2.

Growth of NEP mutant viruses in cell culture and the mouse model. (A) Schematic representation of the wild-type NS segment and the NS1_2A_Flag-NEP segment. In the latter, splicing is prevented by mutation of the splice donor and acceptor site within the NS1 gene. NS1 and NEP are cotranslationally separated by the 2A peptide of porcine teschovirus 1 (PTV-1). (B and C) Growth of the wild-type SC35M and SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP viruses (B) and the indicated NEP mutants (C) in A549 cells. Supernatant of cells infected at an MOI of 0.001 were collected at the indicated time points, and titers were determined by plaque assay. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. (D) Determination of lung titers from BALB/c mice (n = 4 or 5) infected intranasally with 1,000 PFU of the indicated viruses 40 h postinfection. (E) Weight curve of BALB/c mice (n = 5 per group) infected intranasally with 1,000 PFU of the indicated viruses. Numbers in parenthesis indicate mice that succumbed to infection. (F) Continued passaging of either SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_WT, SC35MNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_AAA, or both in A549 cells infected with an MOI of 0.001. Cell supernatant obtained 48 h postinfection were used for passaging and sequencing of the NEP coding sequence. Indicated are electropherograms with the coding sequence corresponding to amino acids 23 to 25 of NEP or NEP_AAA after each passage (P0 to P3).

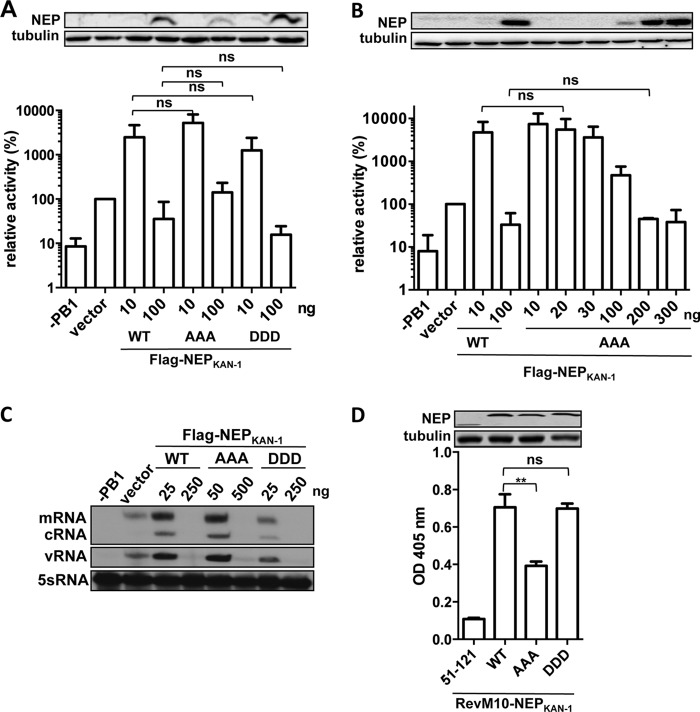

Next, we determined the role of NEP phosphorylation for an avian influenza A virus, which is more dependent on the polymerase-enhancing function of NEP in human cells. To this end, we determined the polymerase-enhancing activity of A/Thailand/1(KAN-1)/04 (H5N1) NEP (6), harboring either triple S-to-A or triple S-to-D mutations, on the polymerase of the putative avian precursor virus of KAN-1, designated AvianPr (6). Substitutions of S23 to S25 with A or D did not abrogate the polymerase-enhancing activity of NEP (Fig. 3A and B). Consistently, the inhibitory effects of WT and mutant NEP are comparable, taking into account the differences in expression levels for Flag-NEP_AAA (Fig. 3B). Polymerase reconstitution and subsequent primer extension analysis in the presence of low levels of Flag-NEP_WT and Flag-NEP_AAA showed a substantial increase of all viral RNA species (Fig. 3C). This increase was less pronounced for Flag-NEP_DDD. As expected, high levels of all tested NEP variants strongly inhibited viral RNA synthesis. Using the RevM10 nuclear export assay, KAN-1 NEP harboring the triple A substitutions showed impaired activity compared to that of WT NEP or NEP_DDD, suggesting that efficient nuclear export requires phosphorylation at these sites (Fig. 3D).

FIG 3.

Effect of NEP alanine and aspartic acid mutants on H5N1 polymerase activity. (A and B) Activity of the AvianPr (H5N1) polymerase in the presence of WT or Flag-NEPKAN-1 mutant proteins expressed from the indicated amounts of plasmid DNA. Standard deviation was calculated from three independent experiments. Student's t test was performed to determine the P value. ns, nonsignificant. (C) Primer extension analysis of the indicated viral RNA transcripts generated after reconstitution of AvianPr (H5N1) polymerase in human HEK293T cells after transfection of the indicated amounts of Flag-NEPKAN-1 expression plasmids. (D) CRM1-dependent export activity of RevM10-NEP fusion proteins. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with expression plasmids coding for the indicated NEP mutants fused to the export-inactive Rev protein (RevM10) and plasmids coding for an intron-containing CAT reporter mRNA harboring a Rev response element. RevM10-NEP51–121 lacking the two NES domains served as a negative control. Protein levels of the NEP fusion proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Export activity was determined by measuring CAT protein levels. Error bars indicate standard deviations from three independent experiments. Student's t test was performed to determine the P value. **, P < 0.01; ns, nonsignificant.

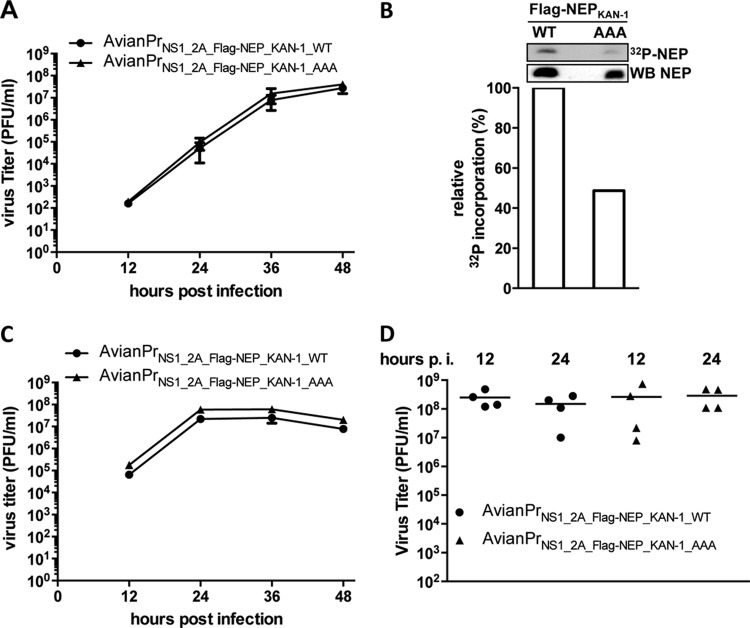

To test the KAN-1 NEP mutants in the context of a viral infection, we rescued AvianPr with an analogously modified segment 8, encoding either Flag-tagged WT NEP (AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_WT) or NEP_AAA (AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_AAA). Both viruses replicated equally well in human A549 cells (Fig. 4A), indicating that phosphorylation at S23 to S25 of KAN-1 NEP is not required for viral growth. However, we repeatedly failed to generate AvianPr coding for NEP_DDD, suggesting that constitutive phosphorylation might not be tolerated at these positions.

FIG 4.

Growth of NEP mutant H5N1 viruses in cell culture and in ovo. (A and C) Growth of AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_WT and AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_AAA in A549 cells (A) or avian DF-1 cells (C). Supernatant of cells infected at an MOI of 0.001 was collected at the indicated time points, and titers were determined by plaque assay. Error bars indicate standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. (B) Phosphorylation of Flag-NEPKAN-1_WT or Flag-NEPKAN-1_AAA in avian DF-1 cells. The bar graph depicts the relative radioactive signal normalized to total NEP levels determined by Western blotting. (D) Viral titers in the allantois fluid of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs after infection with 200 PFU of the indicated viruses 24 h or 48 h postinfection.

Since the level of phosphorylation might be dependent on the intracellular environment of the host, we determined the phosphorylation status of Flag-NEPKAN-1 and Flag-NEPKAN-1_AAA in avian DF-1 cells (Fig. 4B). Similar to results obtained in human cells (Fig. 1B), mutation of the three serine residues resulted in a decrease of phosphorylation to 50%. Infection of DF-1 cells with AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_WT or AvianPrNS1_2A_Flag-NEP_KAN-1_AAA revealed comparable viral growth (Fig. 4C). Similarly, infection of 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs with 200 PFU of each virus resulted in comparable viral titers 24 or 48 h postinfection (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that phosphorylation at serine 23 to 25 is not required for viral growth of avian H5N1 viruses.

There is an increasing body of evidence that NEP is a key regulator of the viral replication cycle (8, 18, 19) and that revelation of its own regulation might lead to a better understanding of the intracellular course of influenza virus infection. The present data indicate that an attractive candidate mechanism, namely, the phosphorylation of the highly conserved serine residues 23 to 25 of NEP, is not crucial to regulate its activity in cell culture (Fig. 2C and 4A and C), mice (Fig. 2D and E), and in ovo (Fig. 4D), although phosphorylation might play a minor role in modulating vRNP export (Fig. 1C and 3D) and polymerase cofactor activity of NEP (Fig. 1F and 3C). This suggests that NEP functions might be regulated differently. The residual phosphorylation of Flag-NEPSC35M_AAA (Fig. 1B) could reflect the presence of other regulatory phosphoacceptor sites, which were not identified previously by mass spectrometry (11). Furthermore, NEP was shown in vitro to be a bona fide target for sumoylation (20), a posttranslational modification that can functionally modify proteins in various manners (21). Alternatively, viral or cellular interaction partners could indirectly regulate NEP. In this line, Pleschka et al. (22) provided evidence that NEP-mediated export is dependent on Raf/MEK/ERK signaling without NEP itself being a target of this pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alexandra Dudek for technical assistance and Georg Kochs for critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was funded by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (FluResearchNet) and the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (SCHW 632/11-2). P.R. is supported by the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 16 April 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Neill RE, Talon J, Palese P. 1998. The influenza virus NEP (NS2 protein) mediates the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 17:288–296. 10.1093/emboj/17.1.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akarsu H, Burmeister WP, Petosa C, Petit I, Muller CW, Ruigrok RW, Baudin F. 2003. Crystal structure of the M1 protein-binding domain of the influenza A virus nuclear export protein (NEP/NS2). EMBO J. 22:4646–4655. 10.1093/emboj/cdg449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang S, Chen J, Chen Q, Wang H, Yao Y, Chen J, Chen Z. 2013. A second CRM1-dependent nuclear export signal in the influenza A virus NS2 protein (NEP) contributes to the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. J. Virol. 87:767–778. 10.1128/JVI.06519-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robb NC, Smith M, Vreede FT, Fodor E. 2009. NS2/NEP protein regulates transcription and replication of the influenza virus RNA genome. J. Gen. Virol. 90:1398–1407. 10.1099/vir.0.009639-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullido R, Gomez-Puertas P, Saiz MJ, Portela A. 2001. Influenza A virus NEP (NS2 protein) downregulates RNA synthesis of model template RNAs. J. Virol. 75:4912–4917. 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4912-4917.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mänz B, Brunotte L, Reuther P, Schwemmle M. 2012. Adaptive mutations in NEP compensate for defective H5N1 RNA replication in cultured human cells. Nat. Commun. 3:802. 10.1038/ncomms1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez JT, Zlatev I, Aggarwal S, Subramanian S, Sachidanandam R, Kim B, Manoharan M, Tenoever BR. 2012. A small-RNA enhancer of viral polymerase activity. J. Virol. 86:13475–13485. 10.1128/JVI.02295-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mänz B, Schwemmle M, Brunotte L. 2013. Adaptation of avian influenza A virus polymerase in mammals to overcome the host species barrier. J. Virol. 87:7200–7209. 10.1128/JVI.00980-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuther P, Giese S, Gotz V, Kilb N, Manz B, Brunotte L, Schwemmle M. 2013. Adaptive mutations in the nuclear export protein of human-derived H5N1 strains facilitate a polymerase-activity enhancing conformation. J. Virol. 88:263–271. 10.1128/JVI.01495-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson JC, Akkina RK. 1991. NS2 protein of influenza virus is found in purified virus and phosphorylated in infected cells. Arch. Virol. 116:69–80. 10.1007/BF01319232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson EC, Denham EM, Thomas B, Trudgian DC, Hester SS, Ridlova G, York A, Turrell L, Fodor E. 2012. Mapping the phosphoproteome of influenza A and B viruses by mass spectrometry. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002993. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmid S, Mayer D, Schneider U, Schwemmle M. 2007. Functional characterization of the major and minor phosphorylation sites of the P protein of Borna disease virus. J. Virol. 81:5497–5507. 10.1128/JVI.02233-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope TJ, Huang XJ, McDonald D, Parslow TG. 1990. Steroid-receptor fusion of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev transactivator: mapping cryptic functions of the arginine-rich motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:7787–7791. 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trautwein C, van der Geer P, Karin M, Hunter T, Chojkier M. 1994. Protein kinase A and C site-specific phosphorylations of LAP (NF-IL6) modulate its binding affinity to DNA recognition elements. J. Clin. Invest. 93:2554–2561. 10.1172/JCI117266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang W, Erikson RL. 1994. Constitutive activation of Mek1 by mutation of serine phosphorylation sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:8960–8963. 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann E, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, Hobom G, Webster RG. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6108–6113. 10.1073/pnas.100133697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manicassamy B, Manicassamy S, Belicha-Villanueva A, Pisanelli G, Pulendran B, Garcia-Sastre A. 2010. Analysis of in vivo dynamics of influenza virus infection in mice using a GFP reporter virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:11531–11536. 10.1073/pnas.0914994107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterson D, Fodor E. 2012. Emerging roles for the influenza A virus nuclear export protein (NEP). PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003019. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chua MA, Schmid S, Perez JT, Langlois RA, Tenoever BR. 2013. Influenza A virus utilizes suboptimal splicing to coordinate the timing of infection. Cell Rep. 3:23–29. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pal S, Santos A, Rosas JM, Ortiz-Guzman J, Rosas-Acosta G. 2011. Influenza A virus interacts extensively with the cellular SUMOylation system during infection. Virus Res. 158:12–27. 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meulmeester E, Melchior F. 2008. Cell biology: SUMO. Nature 452:709–711. 10.1038/452709a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pleschka S, Wolff T, Ehrhardt C, Hobom G, Planz O, Rapp UR, Ludwig S. 2001. Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:301–305. 10.1038/35060098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]