Abstract

We present a case of a 70-year-old man with abdominal aortic aneurysm and coincident pelvic arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Before the operation for the aneurysm, we embolised the pelvic AVM that had multiple feeding arteries and an aneurysmal-dilated draining vein. After decreasing the number of the feeding arteries by coil embolisation, an n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate/lipiodol mixture (1:1) was injected into the prominent feeding artery and nidus with proximal balloon occlusion of the right internal iliac artery to decrease the flow to the nidus. The mixture (1:4–8) was also added for the finer feeding arteries that became apparent after the initial procedure to embolise the rest of the nidus. A follow-up study showed no contrast enhancement of the nidus and aneurysmal draining vein.

Background

Congenital pelvic arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is presumed to be a focal persistence of primitive and vascular channels. AVM in the body and extremity is classified into three types according to the number of feeding arteries and draining veins.1 Most pelvic lesions seem to have a particular angioarchitecture consisting of multiple small arteries and a single draining fistula.2 3

Previous reports have described many cases of embolisation for feeding arteries.2–5 Selective arterial embolisation tends to be staged embolisation and is inadequate because it leaves an evolutive residual AVM. To embolise the nidus sufficiently, blood flow to the AVM should be controlled. Several approaches such as transvenous embolisation of the draining vein or direct puncture have been combined in the transarterial approach.2–4 6

We present a case of pelvic AVM with multiple feeding arteries and a single draining vein treated by transarterial glue embolisation combining coil embolisation of other feeding arteries and balloon occlusion of the internal iliac artery (IIA). As a result, the feeding arteries were simplified, decreasing the proximal flow to the AVM and filling the glue in the nidus as much as possible.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old man with hypertension was diagnosed with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Preoperative contrast-enhanced CT incidentally demonstrated pelvic AVM adjacent to the urinary bladder as well as an abdominal aortic aneurysm greater than 5 cm in diameter (figure 1). CT angiography showed abnormal connections between the arteries from the right IIA and veins with enlargement of the right internal iliac vein (IIV). CT also showed the prominent feeding artery to the nidus. Preoperative vascular mapping angiography showed some feeding arteries from the right IIA and a single draining vein to the right IIV (figure 2). The vascular surgeon scheduled him for replacement of the abdominal aortic aneurysm. To lower the risk of rupture of the pelvic AVM, the surgeon referred the patient to us for embolisation of the pelvic AVM before the abdominal aortic aneurysm operation.

Figure 1.

CT scan demonstrating the nidus of pelvic arteriovenous malformation (arrow) and aneurysmal-dilated vein adjacent to the urinary bladder.

Figure 2.

Angiography showed some feeding arteries from the right internal iliac artery, nidus (arrow) and a single draining vein (arrow head) to the right internal iliac vein.

Two options for the approach to the lesion were considered: a transarterial approach or transarterial and transvenous approaches. We also considered the embolic material—n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) or absolute ethanol. In this case, since the draining vein was aneurysmal dilated, we selected the transarterial approach and an NBCA/lipiodol mixture for the embolic material under balloon occlusion of the prominent feeding artery that could decrease the blood flow to the AVM.

Treatment

A 6.2-F guiding catheter (Elway; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was positioned into the right IIA via the left common femoral artery. Arteriography revealed several feeding arteries arising from the right IIA. A 3.0-F microballoon catheter (Attendant; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was superselectively catheterised into the prominent feeding artery, which was observed by CT angiography using a coaxial technique. On right internal iliac angiography from the guiding catheter under microballoon occlusion of the feeding artery, however, the nidus and expanded emissary vein remained perfused by other smaller feeding arteries. This method did not control the blood flow to the nidus. Next, we embolised the superior and inferior glutaeal arteries and the iliolumbar artery by microcoils to decrease the number of feeding arteries (figure 3, left). A 5.2-F balloon catheter (Selecon MP catheter II; Terumo) was then positioned into the right IIA. A 2.0-F microcathether (Spiner 2μ7; Terumo) was superselectively inserted into the feeding artery that was initially catheterised. When the right IIA was occluded by the proximal balloon catheter, the nidus was entirely perfused from the microcatheter. The NBCA/lipiodol mixture (1:1) was injected from the microcatheter. The feeding artery and part of the nidus were filled with the mixture, but the rest of the nidus was still perfused through other smaller feeding arteries, a finding that became apparent after embolisation (figure 3, right). These arteries were additionally embolised using the NBCA/lipiodol mixture (1:4–8) without proximal balloon occlusion of the IIA. Finally, the right IIA was embolised using microcoils (Tornado, Cook, Indiana, USA) to prevent recanalisation. Right common iliac arteriography showed complete obliteration of the nidus and aneurysmal dilated vein (figure 4).

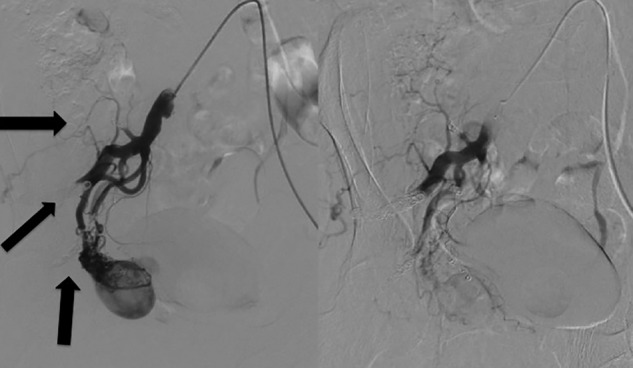

Figure 3.

(Left) We embolised the superior and inferior glutaeal arteries and the iliolumbar artery by microcoils to decrease the number of feeding arteries (arrow:coil). (Right) The rest of the nidus was still perfused through other feeding arteries, which became apparent after the embolisation.

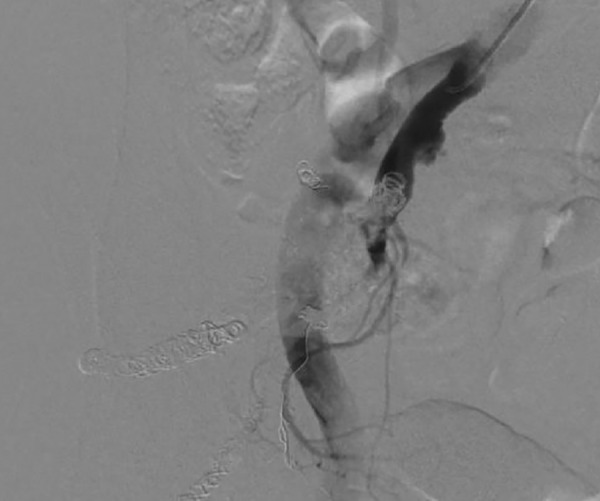

Figure 4.

Right common iliac arteriogram showing complete obliteration of the nidus and aneurysmal-dilated vein.

Outcome and follow-up

After endovascular treatment, the patient has undergone follow-up postcontrast CT for up to 1 year and 5 months. CT demonstrated that the nidus did not show contrast enhancement and the collateral arteries did not develop surrounding the nidus (figure 5). No complication related to endovascular therapy was noted.

Figure 5.

Follow-up CT scans (1 year and 5 months) demonstrating the nidus which was partly filled with the mixture (arrow) but did not show contrast enhancement in the rest of the nidus.

Discussion

We present a case of a pelvic AVM that was embolised only by a transarterial approach. We controlled the flow to the nidus by decreasing the number of feeding arteries—that is, devascularisation—and balloon occlusion of the proximal artery (right IIA).

For embolisation of an AVM with multiple feeding arteries and a single draining vein, control of blood flow to the nidus is critical. Generally, blood flow through the nidus is equal between the draining vein and feeding arteries. When arterial flow to the nidus decreases, draining venous flow also decreases, and vice versa. Therefore, several methods of controlling the blood flow to the nidus have been applied. The first option is to embolise the single draining vein.6 The advantage of this method is that it decreases the arterial blood flow to the nidus using a single vascular procedure. However, the catheter should be inserted as close to the nidus as possible. Embolisation of the draining vein distant to the nidus could change the route of the draining flow. Second, transarterial control of blood flow is also possible. In this case, we combined embolisation of the superior and inferior glutaeal arteries and the iliolumbar artery with proximal balloon occlusion of the IIA. The former directly helped devascularisation of the feeding arteries, and the latter helped to decrease the blood flow to the nidus. Thus, we could control the blood flow to the nidus using only a transarterial approach. However, the disadvantage of this method is the multiplicity of potential feeding arteries. Transarterial devascularisation may not be sufficient when too many feeding arteries are present.

The method of occluding the nidus is also important, as well as control of blood flow to the nidus, because the final goal is to occlude the nidus itself to prevent the development of residual AVM. Liquid agents such as absolute ethanol or NBCA are suitable to fill the nidus. Embolosclerotherapy with direct puncture combined with endovascular treatment was reported recently.2 4 However, in that case, a direct approach was difficult because of the relatively small pelvic AVM. Another option is to fill the nidus transarterially. This is the most conventional option and requires the control of blood flow as aforementioned. We succeeded in opacifying the entire nidus from the prominent feeding artery by controlling the blood flow and filling part of the nidus with the NBCA/lipiodol mixture. However, the rest of the nidus remained, and other smaller arteries that became obvious after the first embolisation were further embolised. The smaller arteries were embolised without balloon occlusion. The first reason was that the small and numerous arteries made catheterisation to each artery impossible. Second, by embolising the part of the nidus and major vessels from the superior and inferior glutaeal arteries, the blood flow to the nidus decreased. Taking into account the viscosity of NBCA/lipiodol mixture, we considered that there was little risk for the mixture to reach non-targeted site through the nidus into draining iliac vein even without proximal balloon occlusion.

In conclusion, transarterial balloon-occluded glue embolisation with devascularisation could be an effective treatment option for pelvic AVM.

Learning points.

For embolisation of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) with multiple feeding arteries and a single draining vein, control of blood flow to the nidus is critical. Transarterial balloon occlusion could be effective for decreasing the blood flow.

The final goal of embolising the AVM is to occlude the nidus itself to prevent the development of residual AVM.

Liquid agents such as absolute ethanol or n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate are suitable for filling the nidus.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Dr Kenji Takizawa who gave advice regarding the treatment method and coordinated the procedure. Although he should have been a coauthor on this manuscript, he passed away and could not be listed. Here, the authors acknowledge his supervision.

Footnotes

Contributors: KM and TY performed the procedure and wrote the manuscript. RK selected the figures and wrote the figure legend. She also advised regarding the discussion. YN provided the approval of the final version of the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Cho SK, Do YS, Shin SW, et al. Arteriovenous malformations of the body and extremities: analysis of therapeutic outcomes and approaches according to a modified angiographic classification. J Endovasc Ther 2006;13:527–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Do YS, Kim Y-W, Park KB, et al. Endovascular treatment combined with emboloscleorotherapy for pelvic arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Surg 2012;55:465–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houbballah R, Mallios A, Poussier B, et al. A new therapeutic approach to congenital pelvic arteriovenous malformations. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24:1102–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae S, Do YS, Shin SW, et al. Ethanol embolotherapy of pelvic arteriovenous malformations: an initial experience. Korean J Radiol 2008;9:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobowitz GR, Rosen RJ, Rockman CB, et al. Transcatheter embolization of complex pelvic vascular malformations: results and long-term follow-up. J Vasc Surg 2001;33:51–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koganemaru M, Abe T, Iwamoto R, et al. Pelvic arteriovenous malformation treated by superselective transcatheter venous and arterial embolization. Jpn J Radiol 2012;30:526–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]