Abstract

Syphilis is a sexually transmissible disease caused by treponema palladium, a microaerophilic spirochete. Syphilis may progress from primary to tertiary stage if left unnoticed and untreated. Dentists should be vigilant and suspect sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis in the differential diagnosis of oral inflammatory or ulcerative lesions with palatal perforation. Moreover, it is imperative that dentists should have knowledge about its stages, characteristic features, oral presentation and prosthetic rehabilitation. This case report describes a case of tertiary syphilis with palatal perforation and the prosthetic rehabilitation of the defect with a prosthetic obturator.

Background

The first association of syphilis with Spirochaeta pallida (now known as Treponema pallidum) was given by Schaudinn and Hoffmann in 1905. Syphilis can progress through four stages namely primary, secondary, latent and tertiary or late stage if left untreated. Most of the individuals with untreated syphilis may develop tertiary syphilis with lesions many years after the initial infection. The oral complications in this stage centre on gumma formation, syphilitic leukoplakia, risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma and neurosyphilis. Gummas are infectious granulomas (cell clusters in various tissues) which tend to arise on the hard palate and tongue, rarely on the soft palate, lower alveolus and parotid gland. A gumma manifests initially as one or more painless swellings which tend to coalesce, giving rise to serpiginous lesions which eventually develop into areas of ulceration, with areas of breakdown and healing which cause irreversible lesions. There may be eventual bone destruction, palatal perforation and oronasal fistula formation. Sometimes the presentation of syphilis imitates symptoms as those of many other diseases, for example, herpes infection, lymphoma, leprosy, chancroid, meningitis, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis and granulomatous diseases. Therefore, it is called as the great imitator. Syphilis has also found to be associated with HIV infection. It has been reported that there has been an increased association of atypical syphilis in patients who are HIV positive than in seronegative patients.1 Therefore, syphilis should feature in the list of differential diagnosis of mid-palatal perforation inspite of its reduced incidence in present days.

Case presentation

A 48-year-old man reported with missing teeth and a perforation in the palate leading to nasal regurgitation of food and nasal twang on speaking. History revealed that he developed a lesion in the anterior part of the mid-palate, which became a perforation at the end of the healing process. His family history was not significant.

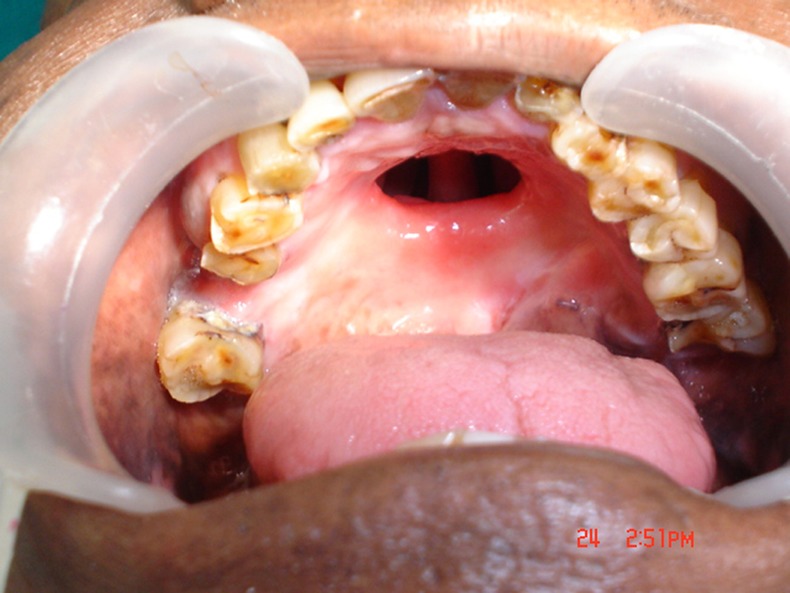

Intraoral examination revealed a spherical perforation of the anterior hard palate in the midline (figure 1). It measured about 2 cm in diameter extending anteriorly up to the rugae area and posteriorly till the premolar region. The margin was smooth, taut and healthy with no tissue growth. Nasal septum was visible. He was using handkerchief to cover the defect to prevent food from entering nasal cavity during feeding.

Figure 1.

Palatal perforation.

Investigations

Records of the patient revealed that following tests had been performed to rule out active disease:

Positive direct microscopic examination (dark field microscopy).

Reactive blood VDRL test (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test).

Reactive RPR (rapid plasma reagin).

Positive TPHA (T. pallidum haemagglutination test).

Negative ELISA.

Since the patient was asymptomatic and free of disease, he was considered for prosthetic rehabilitation.

Differential diagnosis

Palatal perforations can be seen due to various aetiological factors as:2–4

Developmental—cleft palate, impacted canine.

Infections—leprosy, tertiary syphilis, tuberculosis, rhinoscleroderma, naso-oral blastomycosis, leishmaniasis, actinomycosis, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis and diphtheria, secondary syphilis, aspergillosis, atypical mycobacterial infections, deep mycotic infections.

Malignancy—eosinophilic granuloma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, salivary gland tumours, mesenchymal tumours, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, neoplasms (salivary or squamous cell) and midline lethal granuloma, a type of T-cell lymphoma.

Autoimmune diseases-lupus erythematous, sarcoidosis, Crohn's disease and Wegener granulomatosis.

Drug related—cocaine, heroine and narcotics.

Iatrogenic-oroantral fistula following tooth extraction, tumour surgery, corrective surgeries and intubation.

Rare causes—rhinolithcan, patients with psychological problems.

Treatment

Various surgical procedures5 namely, local pediculate flaps, lingual grafts, temporal muscle flaps, oral adipose tissue grafting, free microvascularised flap were considered for correction of palatal perforation. However, in the present case the patient was not willing for surgery and prosthetic rehabilitation at a later stage. He opted for a treatment option of an obturator with removable partial denture for replacement of posterior teeth at a single stage.

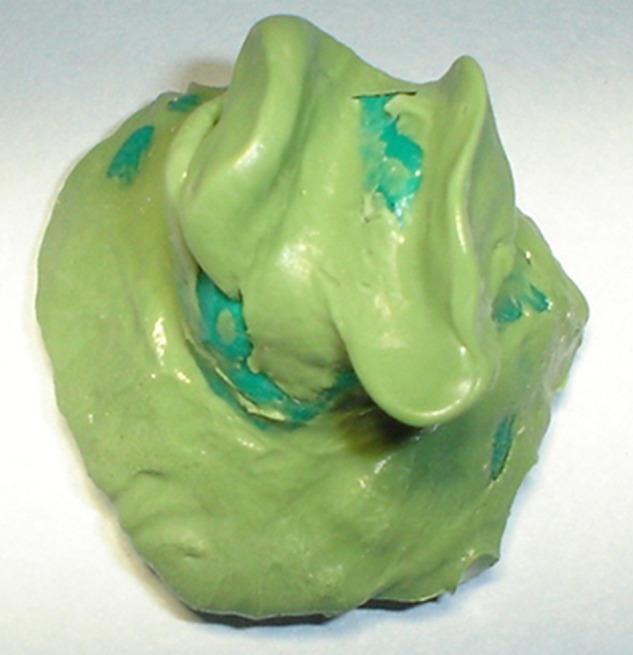

The palatal defect was packed with a continuous cotton strip, coated with petroleum jelly to prevent entry of the impression material into the nasal cavity. Green stick compound (DPI pinnacle tracing sticks, Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India) was softened and used for making primary impression and after occupying the defect, the remaining material was adapted on the palatal surface which could be used as a handle for holding as well as for pick up impression. The material was scraped around 1 mm all over and final impression was made using heavy body impression material (Exaflex,GCAmerica Inc, Alsip, Illinois, USA) (figure 2). Then tray adhesive was applied on the stainless steel tray and a pick up impression was made with putty impression material. The impression was poured with dental stone (Goldstone, Asian chemicals, Rajkot, Gujarat, India). The cast recorded the nasal septum through the perforation (figure 3). Undercuts were blocked with plaster of Paris (White gold) and wax up was carried out so that the future prosthesis extends just inside to be retentive. Trial of the teeth arrangement was performed and after obtaining the patient’s approval it was processed as a conventional removable partial denture. The prosthesis was finished and polished (figure 4) and inserted (figures 5 and 6).

Figure 2.

Final impression of the defect.

Figure 3.

Final cast with the defect and missing teeth.

Figure 4.

Tissue surface of the obturator.

Figure 5.

Intraoral view of the obturator with removable partial denture.

Figure 6.

Lateral profile in occlusion.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was satisfied with the treatment. The obturator improved the clarity of speech by adding resonance to the voice, it prevented nasal regurgitation and also facilitated swallowing as well as mastication.

Discussion

There is very less literature published on prosthetic management for palatal perforation in syphilitic patients. The treatment options for the present case were a hollow bulb obturator (open or closed type) or a simple obturator for aiding speech and normal oral functions of the patient.

The choice of open or closed hollow obturators is controversial. Each type has advantages and disadvantages. Hollow obturators are lightweight and easier to fabricate, but such a design has some inherent disadvantages. First, the open type requires the patient to remove and clean the obturator more often because it can accumulate secretions and food particles. The closed type prevents collection of fluid and secretions over the obturator but still the fluid can get absorbed through microporosities in the acrylic resin seal. The hollow inner surface cannot be cleaned and provides a medium for the growth of microorganisms. Second, the objects packed in the obturator to occupy the space (salt, sugar) may move or deform under pressure during packing resulting in an uneven thickness of the obturator. Third, sometimes large undercuts require blocking out too much of the undercuts resulting in a heavy hollow obturator. Considering these disadvantages of hollow bulb obturators, a simple obturator was planned for the patient.

In the present case the height of the obturator was adjusted to just engage the walls of the defect to provide retention and stability. If overextended the obturator may cause nausea or vibration during mastication. To overcome this, the lateral wall of the bulb can be extended higher than the mesial wall. In the present case, the lateral band of palatal perforation and tissue undercuts provided retention in the tissue fitting side of the prosthesis. Since surgical option would have just closed the defect and would have required a second-stage prosthetic rehabilitation the patient did not opt for it. The obturator not only took care of the perforation but also helped in mastication as it replaced teeth.

Learning points.

Although incidence of syphilis, especially advancement to the stage of tertiary syphilis, has reduced, it should still feature in the list of differential diagnosis of mid palatal perforations.

The clinical manifestations and the routine diagnosis may be masked by the oral and systemic clinical presentations of syphilis as it imitates many other diseases.

Dentists should be aware of the correlation between syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases as HIV.

Dentists must be aware of the manifestations of syphilis in different stages and should refer for medical management of sexually transmitted diseases.

Footnotes

Contributors: VM and YV were involved in patient care. DL and AP reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Iglesias VH, Kustner CE. The reappearance of a forgotten disease in the oral cavity: syphilis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2009;14:416–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffari PM, Seyyedi S, Chaghmaghi MA. Palatal perforation: causes and features. Webmed Central Oral Med 2011;2:WMC001890 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calka O, Karadag AS, Bilgili SG, et al. A case presenting with gummas. J Turk Acad Dermatol 2012;6:1263c1 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lypka MA,, Urata MM. Cocaine-induced palatal perforation. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelo S, Gasparini G, Di Petrillo A, et al. Le Fort I osteotomy and the use of bilateral bichat bulla adipose flap: an effective new technique for reconstructing oronasal communications due to cocaine abuse. Ann Plast Surg 2008;60:49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]