Abstract

Background

Mental disorders account for a substantial proportion of the total disease burden in China but the number, distribution and characteristics of the mental health professionals available to provide services for mentally ill individuals is unknown.

Aim

Describe the distribution and characteristics of medical professionals working in mental health facilities around China.

Methods

Information on the numbers and characteristics of health professionals working in mental health facilities in China in 2010 was obtained from the Statistical Information Center of the Ministry of Health and the population-adjusted ratios and characteristics of these mental health professionals were compared across the seven geographic regions of the country.

Results

Among the 757 specialized mental health facilities identified, 649 (86%) were psychiatric hospitals. A total of 68,796 medical professionals (5.16/100,000 population) were working in these facilities, including 20,480 psychiatrists (1.54/100,000) and 35,337 registered nurses (2.65/100,000). Over 98% of these medical professionals worked in psychiatric hospitals. Among the psychiatrists, 29% only had a technical school degree and 14% had no academic degree at all; among the nurses, 46% had no academic qualifications. The duration of employment as a psychiatrist or as a psychiatric nurse was longer among medical professionals working in the economically less dynamic northern parts of the country. The population ratios of licensed physicians and registered nurses working in mental health facilities were significantly higher than average in the relatively wealthy eastern and northeastern parts of the country.

Conclusions

Almost all mental health professionals in China work in specialty psychiatric hospitals. The numbers and geographic distribution of trained mental health professionals in China are grossly inadequate to meet the mental health needs of the population. China has a much smaller mental health workforce per 100,000 residents than other upper-middle-income countries, and the range of professionals who provide mental health services is much narrower.

Abstract

背景

精神障碍在我国疾病总负担中占有相当大的比例,但可提供于精神障碍患者心理卫生服务的专业人员数量,分布和特点还是未知数。

目的

全面了解我国精神卫生机构人力资源分布现状和特点。

方法

从卫生部统计信息中心获得2010年在中国精神卫生机构中工作的卫生技术人员的数量和特征,比较七个地理区域精神卫生专业人员的人口比例和特征。

结果

在757家精神卫生机构内,649家(86%)是精神病院。在这些机构内卫生技术人员共计68,796人(5.16人/10万人口),包括精神科医师20,480人(1.54人/10万人口)和注册护士35,337人(2.65人/10万人口)。超过80%的卫生技术人员都工作在精神病院。29%的精神科医生人仅具有技校学历,而14%的精神科医生没有学位。在护士中有46%的护士没有学历。我国经济比较落后的北部地区精神科医生或护士的工龄较其长。在我国相对较富裕的东部和东北部地区,精神卫生机构中执业医师和注册护士的人口比例要高于平均水平。

结论

我国几乎所有的精神卫生技术人员都工作在精神科专科医院。训练有素的卫生技术人员在数量和地区的分布上远远无法满足人们对卫生健康的需求。与其他中上等收入国家相比,我国每10万人口拥有的精神卫生资源较少,所能提供精神卫生服务的专业人员范围也较窄。

1. Introduction

Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Project indicate that mental disorders account for 11% of overall disease burden in low- and middle-income countries, but only 35 to 50% of individuals with mental illnesses ever received treatment.[1]-[4] In China, mental disorders have become a major cause of disease burden;[5] based on current projections, by 2020 they will account for over 15% of the total burden of disease and injury in the country.[6] The largest mental health epidemiological study conducted in China to date (with a sample of 63,000 and a sampling frame of 113 million adults)[7] estimated that there are 173 million individuals with current mental disorders in the country but only 8% of them have ever received any type of mental health treatment. It is unknown whether or not the current mental health services and the currently available numbers of mental health professionals can meet this large and growing need for services. To help understand the current situation, this study describes the number and characteristics of health professionals working in mental health institutions throughout China.

2. Methods

2.1. Data

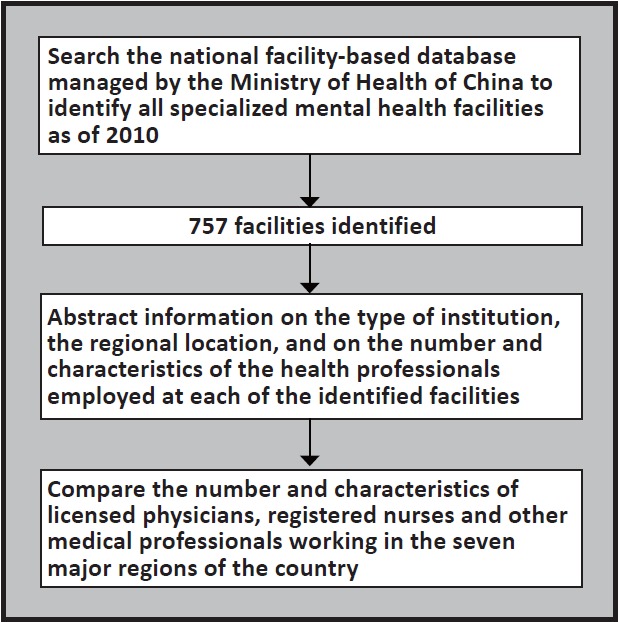

The steps used to identify the data used in this analysis are shown in Figure 1. For the purpose of this study, a ‘mental health facility’ refers to any specialty mental health facility including psychiatric hospitals, free-standing outpatient clinics (that are not administered by psychiatric hospitals), and mental health surveillance centers (that monitor mental health conditions in the community and, in some locations, provide follow-up care to mentally ill individuals). Most of these facilities are administered by the Ministry of Health, but the Ministry of Civil Affairs (the ministry responsible for public welfare services) also administers many chronic-care psychiatric hospitals, the Ministry of Public Security administers the forensic psychiatric hospitals, and there are a growing number of mental health facilities administered by local communities or by private individuals or organizations.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

All medical facilities in China provide monthly updates to the Ministry of Health Statistics Information Center, where data is archived annually. The authors searched this database (updated to 2010) using the keywords ‘mental health’ and ‘medical facility’ and identified 757 different specialized mental health facilities. The characteristics of the facilities and the number and characteristics of the medical professionals working at these facilities in 2010 were abstracted from the database and used in the current analysis. According to the definition in the Provisional Regulations of Medical Professionals,[8] ‘medical professionals’ refers to physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and medical technicians; in the current analysis these professionals were categorized as ‘licensed physicians’ (i.e., psy-chiatrists and other physicians working in mental health institutions), ‘registered nurses’, and ‘other medical professionals’ (i.e., pharmacists and medical technicians). Physicians and nurses in China are classified into six groups based on their professional rank: senior clinician, associate-level clinician, intermediate-level clinician, assistant-level clinician, entry-level clinician, and clinicians who are not yet classified. Seven geographical regions of China employed in the analysis were defined as follows: ‘North China’ included Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia; ‘North-East China’ included Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang; ‘East China’ included Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, and Shandong; ‘Central China’ included Henan, Hubei, and Hunan; ‘South China’ included Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan; ‘South-West China’ included Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan; and ‘North-West China’ included Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, and Xinjiang. The 2010 population of each region was obtained from the 2010 national census published by the National Statistical Bureau.[9]

2.2. Statistical analysis

SPSS13.0 statistical software was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the gender, age, level of education, years of experience in mental health, and professional ranks of the three categories of medical professionals in the seven geographical regions. The proportion of all licensed physicians and registered nurses in China working in mental health facilities was assessed by referring to the total number of physicians and nurses reported in the 2010 Public Report of Developments in Medical Services of China.[10] The population-adjusted numbers of physicians, nurses, and other medical professionals working in mental health facilities in China were compared to the 2010 aggregated data for different types of countries reported by the World Health Organization.[11] Comparison of rates of mental health professionals between the seven regions was conducted using at Tukey-type multiple comparison method based on an arcsin transformation of the original proportions.[12] Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests and the Ridit method[13] were used for cross-regional comparisons of the characteristics of mental health professionals.

3. Results

3.1. Number and institutional distribution of mental health professionals

As shown in Table 1, a total of 757 specialized mental health facilities were identified in the Ministry of Health database, including 649 (85.6%) psychiatric hospitals, 82 (10.8%) free-standing mental health clinics, and 26 (3.4%) mental health surveillance centers. There were a total of 68,796 medical professionals working in these institutions in 2010, including 20,480 (30%) licensed physicians, 35,337 (51%) registered nurses, and 12,979 (19%) other medical professionals. Over 98% of these medical professionals worked in psychiatric hospitals. The Ministry of Health administered 56.9% of all types of facilities and 63.2% of all psychiatric hospitals; 79.7% of all mental health professionals worked in these facilities. The Ministry of Civil Affairs administered 15.5% of all types of facilities and 17.3% of all hospitals; 15.0% of all mental health professionals worked in these facilities. The Ministry of Public Security administered 1.8% of all facilities and 2.0% of all psychiatric hospitals; 1.8% of all mental health professionals worked in these facilities. And 25.8% of all facilities and 17.6% of all hospitals were administered by local agencies or private individuals; 4.6% of all mental health professionals worked in these facilities.

Table 1.

Numbers of different types of medical professionals working in the 757 specialized mental health facilities listed in China's Ministry of Health Database in 2010

| Type of facility | number of facilities |

all professional staff |

licensed physicians |

registered nurses |

other professional staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All facilities | 757 | 68,796 | 20,480 | 35,337 | 12,979 |

| all hospitals | 649 | 67,834 | 20,133 | 34,943 | 12,758 |

| all free-standing clinics | 82 | 206 | 114 | 57 | 35 |

| all surveillance centers | 26 | 756 | 233 | 337 | 186 |

| Ministry of Health facilities | 431 | 54,080 | 16,172 | 27,808 | 10,100 |

| hospitals | 410 | 53,570 | 16,007 | 27,609 | 9954 |

| free-standing clinics | 6 | 20 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

| surveillance centers | 15 | 490 | 150 | 196 | 144 |

| Ministry of Civil Affairs facilities | 117 | 10,289 | 2823 | 5522 | 1944 |

| hospitals | 112 | 10,147 | 2780 | 5448 | 1919 |

| free-standing clinics | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| surveillance centers | 4 | 141 | 42 | 74 | 25 |

| Ministry of Public Security facilities | 14 | 1245 | 345 | 701 | 199 |

| hospitals | 13 | 1236 | 341 | 697 | 198 |

| free-standing clinics | 1 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| surveillance centers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Private or locally administered facilities | 195 | 3182 | 1140 | 1306 | 736 |

| hospitals | 114 | 2881 | 1005 | 1189 | 687 |

| free-standing clinics | 74 | 176 | 94 | 50 | 32 |

| surveillance centers | 7 | 125 | 41 | 67 | 17 |

3.2. Numbers and population ratios of medical professionals in mental health facilities in China

Table 2 shows the regional distribution of medical professionals working in the identified facilities. In 2010, the overall number of mental health professionals per 100,000 population was 5.16, including 1.54 physicians, 2.65 nurses, and 0.97 other types of mental health professionals. For licensed physicians, registered nurses and all types of mental health professionals, the highest rates per 100,000 population were in North-East China and East China and the lowest rates were in North-West China and Central China. For other mental health professionals (i.e., pharmacists and medical technicians working in mental health facilities) the highest rates per 100,000 population were in North China and the lowest in North-West China. Given the large numbers involved, most of these regional differences in population-adjusted rates of mental health professionals were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Number of mental health professionals working in 757 specialized mental health facilities in seven regionsa of China listed in China's Ministry of Health Database in 2010

| Region | Population (100 million) |

All mental health professionalsb |

Licensed physiciansb |

Registered nursesb |

Other professionalsb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (% total) | /100,000 | n (% total) | /100,000 | n (% total) | /100,000 | n (% total) | /100,000 | |||||

| North-East | 1.10 | 7552 (11.0%) | 6.87 | 2255 (11.0%) | 2.05 | 3988 (11.3%) | 3.63 | 1309 (10.1%) | 1.19 | |||

| East | 3.93 | 24,785 (36.0%) | 6.31 | 7530 (36.8%) | 1.92 | 13,078 (37.0%) | 3.33 | 4177 (32.2%) | 1.06 | |||

| North | 1.65 | 9320 (13.6%) | 5.65 | 2650 (12.9%) | 1.61 | 4502 (12.7%) | 2.73 | 2168 (16.7%) | 1.31 | |||

| South | 1.59 | 7907 (11.5%) | 4.97 | 2279 (11.1%) | 1.43 | 4062 (11.5%) | 2.56 | 1566 (12.1%) | 0.98 | |||

| South-West | 1.93 | 8723 (12.7%) | 4.52 | 2693 (13.2%) | 1.40 | 4541 (12.9%) | 2.35 | 1489 (11.5%) | 0.77 | |||

| Central | 2.17 | 7685 (11.2%) | 3.54 | 2210 (10.8%) | 1.02 | 3857 (10.9%) | 1.78 | 1618 (12.5%) | 0.75 | |||

| North-West | 0.97 | 2824 (4.1%) | 2.91 | 863 (4.2%) | 0.89 | 1309 (3.7%) | 1.35 | 652 (5.0%) | 0.67 | |||

| Total | 13.40 | 68,796 (100%) | 5.16 | 20,480 (100%) | 1.54 | 35,337 (100%) | 2.65 | 12,979 (100%) | 0.97 | |||

a See the Methods section for a description of the Provinces included in each of the geographic regions

b Multiple pairwise comparison analysis (using a Tukey-type multiple comparison method) found that the number of all mental health professionals and the numbers of registered nurses per 100,000 population between each of the seven regions were significantly different, with highest rate in the North-East to the lowest rate in the North-West. The same pattern existed for licensed physicians and other professionals but some of the between-region differences were not statistically significant: in physicians the rate per 100,000 between the North-East and the East and between the South and South-West were not significant; in other professionals the North versus North-East, East versus South, South-West versus South, and Central versus North-West rates per 100,000 population were not significant.

According to the 2010 Public Report of Developments in Medical Services of China,[13] there were 2,413,000 licensed physicians and 2,048,000 registered nurses in all of China in 2010. Thus, physicians working in mental health facilities accounted for 0.85% of all physicians in the country and registered nurses working in mental health facilities accounted for 1.73% of all registered nurses in the country.

Table 3 compares the mental health workforce in China to that of other regions of the world. Despite currently being classified as an upper-middle-income country, China has a much smaller number of health professionals per 100,000 population working in mental health institutions than other upper-middle-income countries (5.16 v. 28.15). Another unique aspect of the mental health workforce is China is the much higher proportion of physicians: in China 30% of mental health professionals are licensed physicians but the corresponding proportions in low-income, lower-middle-income, upper-middle-income and high-income countries are 7%, 10%, 7%, and 14%, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison of numbers of different types of mental health professionals per 100,000 population between China and different regions of the world in 2010

| Region | All professionals |

Physicians | Nurses | Psycho- therapists |

Social workers |

Rehabilitation specialists |

Other professionals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Low-income countries | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.18 |

| Lower-middle-income countries | 5.29 | 0.54 | 2.93 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 1.54 |

| Upper-middle-income countriesa | 28.15 | 2.03 | 9.72 | 1.47 | 0.76 | 0.23 | 13.94 |

| High-income countries | 62.28 | 8.59 | 29.15 | 3.79 | 2.16 | 1.51 | 17.08 |

| Global averagea | 10.05 | 1.27 | 4.95 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.06 | 3.26 |

| China | 5.16 | 1.54 | 2.65 | unknownb | unknownb | unknownb | 0.97 |

a includes China

b there is, as yet, no formal professional designation for psychotherapists, psychiatric social workers or psychiatric rehabilitation specialists in China

3.3. Characteristics of medical professionals working in mental health facilities in China

Among licensed physicians working in mental health facilities, 11,897 (58.1%) were male and 8583 (41.9%) were female; among registered nurses, 4495 (12.7%) were male and 30,842 (87.3%) were female; and among other professionals working at mental health facilities 5322 (41.0%) were male and 7657 (59.0%) were female. Among licensed physicians, 0.1% were under 25 years of age, 67.4% were 25 to 44 years of age, and 32.6% were 45 years of age or older; among registered nurses, 13.3% were under 25, 63.2% were 25 to 44, and 23.4% were 45 or older; among other mental health professionals, 15.6% were under 25, 58.7% were 25 to 44, and 25.7% were 45 or older.

As shown in Table 4, 32% of licensed physicians working in mental health facilities had less than 10 years of experience working in mental health while 18% had more than 30 years of experience working in mental health. There was a statistically significant cross-regional difference in the level of experience of licensed physicians (χ2=178.89, p<0.001); pair-wise comparisons found that physicians working in North-East China had longer work histories in mental health than physicians working in other regions of the country, and those working in South China had shorter work histories than those working in other regions of the country.

Table 4.

Years of work experience of licensed physicians and registered nurses working in 757 mental health facilities in different regions of Chinaa in 2010

| Region | Years of work experience in mental health [n (%)] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| <5 years | 5-9 years | 10-19 years | 20-29 years | ≥30 years | |

|

| |||||

| Licensed physiciansb | |||||

| North-East | 240 (10.6%) | 324 (14.4%) | 572 (25.4%) | 687 (30.5%) | 432 (19.2%) |

| East | 1217 (16.2%) | 1275 (16.9%) | 2053 (27.3%) | 1619 (21.5%) | 1366 (18.1%) |

| North | 302 (11.4%) | 394 (14.9%) | 829 (31.3%) | 559 (21.1%) | 566 (21.4%) |

| South | 413 (18.1%) | 459 (20.1%) | 668 (29.3%) | 414 (18.2%) | 325 (14.3%) |

| South-West | 407 (15.1%) | 459 (17.0%) | 727 (27.0%) | 561 (20.8%) | 539 (20.0%) |

| Central | 310 (14.0%) | 440 (19.9%) | 640 (29.0%) | 501 (22.7%) | 319 (14.4%) |

| North-West | 74 (8.6%) | 156 (18.1%) | 274 (31.8%) | 211 (24.5%) | 148 (17.2%) |

| Total | 2963 (14.5%) | 3507 (17.1%) | 5763 (28.1%) | 4552 (22.2%) | 3695 (18.0%) |

|

| |||||

| Registered nursesc | |||||

| North-East | 549 (13.8%) | 494 (12.4%) | 673 (16.9%) | 1356 (34.0%) | 916 (23.0%) |

| East | 3098(23.7%) | 2073 (15.9%) | 3227 (24.7%) | 3279 (25.1%) | 1401 (10.7%) |

| North | 814 (18.1%) | 548 (12.2%) | 1065 (23.7%) | 1295 (28.8%) | 780 (17.3%) |

| South | 845 (20.8%) | 787 (19.4%) | 1212 (29.8%) | 874 (21.5%) | 344 (8.5%) |

| South-West | 1456 (32.2%) | 611 (13.5%) | 884 (19.5%) | 936 (20.6%) | 654 (14.4%) |

| Central | 815 (21.1%) | 749 (19.4%) | 930 (24.1%) | 912 (23.7%) | 451 (11.7%) |

| North-West | 218 (16.7%) | 185 (14.1%) | 376 (28.7%) | 350 (26.7%) | 180 (13.8%) |

| Total | 7795 (22.1%) | 5447 (15.4%) | 8367 (23.7%) | 9002 (25.5%) | 4726 (13.4%) |

a See the Methods section for a description of the Provinces included in each of the geographic regions

b Using Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the duration of work experience for licensed physicians was significantly different by region; listed from longest to shortest duration of work, the regional differences were as follows: North-East>North, North-West>South-West, East, Central>South; and South-West>Central

c Using Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the duration of work experience for registered nurses were significantly different by region; listed from longest to shortest duration of work, the regional differences were as follow: North-East>North>North-West>Central, East>South, South-West

Among all registered nurses working in mental health facilities, 38% had less than 10 years of pro-fessional experience and 13% had more than 30 years of experience. There were statistically significant differences across regions (χ2=886.07, p<0.001); nurses working in North-East China had longer work histories than those in other regions and nurses working in South China and South-West China had shorter work histories.

As shown in Table 5, slightly over half (51%) of the licensed physicians working in mental health facilities in China have a bachelor's degree in medicine (which is usually a 5-year degree after completing high school). A relatively small proportion of psychiatrists (6%) have graduate degrees – that is, master's or doctoral degrees in medicine (usually specializing in psychiatry). Twenty-nine percent of the physicians have technical college degrees (usually 3-years post high school). And 14% of the licensed physicians do not have any formal degree; most of these are older clinicians or senior nurses who have been ‘grandfathered’ into the physician role. There were significant differences by region in the level of education of physicians working as psychiatrists: those working in North China had higher academic qualifications than those working in other regions.

Table 5.

Educational status of licensed physicians and registered nurses working in 757 mental health facilities in different regions of Chinaa in 2010

| Region | Postgraduate degree |

Bachelor's degree |

Technical college |

High school and below |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Licensed physiciansb | |||||||

| North-East | 73 (3.2%) | 1149 (51.0%) | 691 (30.6%) | 342 (15.2%) | |||

| East | 434 (5.8%) | 4304 (57.2%) | 1912 (25.4%) | 880 (11.7%) | |||

| North | 279 (10.5%) | 1189 (44.9%) | 807 (30.5%) | 375 (14.2%)) | |||

| South | 141 (6.2%) | 1151 (50.5%) | 629 (27.6%) | 358 (15.7%) | |||

| South-West | 89 (3.3%) | 1077 (40.0%) | 945 (35.1%) | 582 (21.6%) | |||

| Central | 193 (8.7%) | 1120 (50.7%) | 635 (28.7%) | 262 (11.9%) | |||

| North-West | 31 (3.6%) | 405 (46.9%) | 307 (35.6%) | 120 (13.9%) | |||

| Total | 1240 (6.1%) | 10,395 (50.8%) | 5926 (28.9%) | 2919 (14.3%) | |||

| Registered nursesc | |||||||

| North-East | 0 (0.0%) | 429 (10.8%) | 1351 (33.9%) | 2208 (55.4%) | |||

| East | 6 (0.0%) | 1738 (13.3%) | 6154 (47.1%) | 5180 (39.6%) | |||

| North | 9 (0.2%) | 528 (11.7%) | 2024 (45.0%) | 1941 (43.1%) | |||

| South | 0 (0.0%) | 287 (7.1%)) | 1508 (37.1%) | 2267 (55.8%) | |||

| South-West | 1 (0.0%) | 196 (4.3%) | 2077 (45.7%) | 2267 (49.9%) | |||

| Central | 2 (0.1%) | 503 (13.0%) | 1857 (48.1%) | 1495 (38.8%) | |||

| North-West | 0 (0.0%) | 74 (5.7%) | 525 (40.1%) | 710 (54.2%) | |||

| Total | 17 (0.0%) | 3761 (10.6%) | 15,496 (43.9%) | 16,068 (45.5%) | |||

a See the Methods section for a description of the Provinces included in each of the geographic regions

b Using Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the educational attainment of licensed physicians were significantly different by region; North>Central>East, North-West, South, South-West, North-East; and East, North-West, South>North-East

c Using Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the educational attainment of registered nurses was significantly higher in North China than in the other six regions

Very few of the registered nurses working in mental health facilities had post-graduate degrees and only 11% had bachelor's degrees. Forty-four percent of registered nurses had a two-year or three-year degree from a technical college and the remaining 46% had no academic qualification of any kind. There were significant differences in the educational attainment of psychiatric nurses in the seven regions: similar to the situation with physicians, nurses working in mental health facilities in North China had higher academic qualifications than those working in other regions of the country.

As shown in Table 6, the professional rank of the majority of licensed physicians working in mental health facilities were at the assistant-level or intermediate-level. There were significant cross-regional differences in the professional ranks of physicians working in mental health facilities (χ2=196.11, p<0.001): multiple comparison tests showed that physicians working in North-East China had higher professional ranks than those working in other regions of the country while those working in South China and South-West China had lower professional ranks than those working in other parts of the country.

Table 6.

Professional level of licensed physicians and registered nurses working in 757 mental health facilities in different regions of Chinaa in 2010

| Region | Senior clinician |

Associate-level clinician |

Intermediate-level clinician |

Assistant-level clinician |

Entry-level clinician |

Clinicians not yet classified |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Licensed physiciansb | |||||||||||

| North-East | 154 (6.8%) | 382 (16.9%) | 821 (36.4%) | 657 (29.1%) | 138 (6.1%) | 103 (4.6%) | |||||

| East | 342 (4.5%) | 1138 (15.1%) | 2424 (32.2%) | 2699 (35.8%) | 467 (6.2%) | 460 (6.1%) | |||||

| North | 216 (8.2%) | 314 (11.9%) | 857 (32.3%) | 841 (31.7%) | 153 (5.8%) | 269 (10.2%) | |||||

| South | 58 (2.5%) | 310 (13.6%) | 643 (28.2%) | 938 (41.2%) | 189 (8.3%) | 141 (6.2%) | |||||

| South-West | 38 (1.4%) | 277 (10.3%) | 849 (31.5%) | 1144 (42.5%) | 234 (8.7%) | 151 (5.6%) | |||||

| Central | 95 (4.3%) | 305 (13.8%) | 723 (32.7%) | 801 (36.2%) | 224 (10.1%) | 62 (2.8%) | |||||

| North-West | 47 (5.5%) | 113 (13.1%) | 269 (31.2%) | 326 (37.8%) | 66 (7.7%) | 42 (4.9%) | |||||

| Total | 950 (4.6%) | 2839 (13.7%) | 6586 (32.2%) | 7406 (36.2%) | 1471 (7.2%) | 1228 (6.0%) | |||||

| Registered nursesc | |||||||||||

| North-East | 7 (0.2%) | 220 (5.5%) | 1203 (30.2%) | 1097 (27.5%) | 1387 (34.8%) | 74 (1.9%) | |||||

| East | 12 (0.1%) | 308 (2.4%) | 3509 (26.8%) | 4240 (32.4%) | 4564 (34.9%) | 445 (3.4%) | |||||

| North | 4 (0.1%) | 78 (1.7%) | 969 (21.5%) | 1562 (34.7%) | 1505 (33.4%) | 384 (8.5%) | |||||

| South | 5 (0.1%) | 70 (1.7%) | 813 (20.0%) | 1222 (30.1%) | 1830 (45.1%) | 122 (3.0%) | |||||

| South-West | 1 (0.0%) | 60 (1.3%) | 719 (15.8%) | 1323 (29.1%) | 2259 (49.8%) | 179 (3.9%) | |||||

| Central | 1 (0.0%) | 67 (1.7%) | 988 (25.6%) | 1139 (29.5%) | 1615 (41.9%) | 47 (1.2%) | |||||

| North-West | 2 (0.2%) | 34 (2.6%) | 285 (21.8%) | 430 (32.9%) | 530 (40.5%) | 28 (2.1%) | |||||

| Total | 32 (0.1%) | 837 (2.4%) | 8486 (24.0%) | 11,013 (31.2%) | 13,690 (38.7%) | 1279 (3.6%) | |||||

a See the Methods section for a description of the Provinces included in each of the geographic regions

b Using Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the professional ranks of licensed physicians were significantly different by region: North-East>East, North, Central, North-West>South, South-West

cUsing Ridit analysis to compare ranks, the professional ranks of registered nurses were significantly different by region: North-East>East>Central, North-West>North>South>South-West

The professional rank of most registered nurses working in mental health facilities were at the entry-level, assistant-level or intermediate-level. Around the entire nation, there were only 32 registered nurses who had the highest professional level (i.e., senior clinician). There were statistically significant cross-regional differences in the professional rank of registered nurses (χ2=595.86, p<0.001): nurses working in North-East China had higher professional ranks than those in other regions while those working in South-West China had lower professional ranks than those working in other regions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This study provides the most comprehensive national analysis of medical professionals working in mental health facilities in China yet available. Unlike most other countries in which the majority of mental health professionals work in private clinics or non-specialized institutions, the vast majority of mental services in China are provided at specialized mental health facilities, so the current analysis provides a reasonable assessment of the overall distribution of mental health professionals in the country. Our findings show that most services are provided by psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses working in psychiatric hospitals and that the regional distribution of these services is heavily skewed in favor of the relatively wealthy eastern and north-eastern parts of the country. This regional distribution is consistent with other analyses which show that medical professionals tend to be concentrated in more economically prosperous communities.[14] Compared to other countries at a similar level of development to that of China, there is a serious insufficiency of mental health professionals in China (5.2 v. 28.2 per 100,000 population) and the proportion of mental health professionals who are licensed physicians is much higher in China (30% v. 7%), primarily because of the virtual absence of clinical psychologists, psychiatric social workers, psychiatric rehabilitation workers, and other non-medical mental health professionals.

We also found that the level of training of the licensed physicians and registered nurses working in mental health facilities in China is quite low. Twenty-nine percent of physicians only had a technical school degree and 14% have no academic degree at all. Forty-six percent of the nurses had no academic qualifications. This is a common problem in low- and middle-income countries,[15] partly because qualified young medical professionals avoid psychiatry as a career choice due to its limited professional flexibility and due to the perceived low efficacy of the available treatments for mental health disorders.[16] This problem is magnified in China by the relatively low pay of mental health professionals compared to that of other medical professionals and by the transference of the stigma associated with mental illnesses to those who work with the mentally ill.[17] There were also regional differences in the educational attainment of mental health professionals; for both physicians and nurses, those from North China had better educational qualifications than those from other parts of the country.

The interregional differences in the duration of employment as a mental health professional may be indirectly related to regional economic differences. For both physicians and nurses working as mental health professionals, those in North-East China, North China and North-West China had longer work histories in mental health than those from South-West China, South China, East China and Central China. This may reflect the more static economic environment and less frequent career changes of professionals in northern China compared to the dynamic economic environment in other parts of the country that promotes more frequent career changes among young professionals.

4.2. Limitations

There are some mental health facilities administered by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, by the Ministry of Public Security, and by local agencies that were not identified in the Ministry of Health database used in our analysis. And some large general hospitals in China are now providing specialized psychiatric and psychological services. Thus our analysis does not identify all mental health professionals working in the country; but we expect that the number of professionals not captured in our analysis is relatively small, so this is unlikely to affect our overall results.

This analysis does not consider mental health services provided by non-specialized physicians in general hospitals and community health clinics around the country so it may give a skewed picture of the overall pattern of mental health providers. There is little data available to determine the volume of these non-specialized mental health services, but we expect this to be a very small part of the overall mental health delivery system. Reasons for this assumption include the limited training in mental health during medical school, the high volume of most medical services, and general physicians' reluctance to deal with their patients' mental health problems.

Future research about the provision of mental health services in the country needs to expand the monitoring system to include all specialized and non-specialized health facilities and, possibly, non-health facilities that provide general counseling (e.g., hotline services, psychological clinics in schools, etc.). Future research also needs distinguish other types of mental health professionals (e.g., clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers) and to better characterize the mental health training received by the professionals who provide mental health services.

4.3. Implications

These findings demonstrate the magnitude of the challenge facing China as it moves forward with implementing its new national mental health law[18] which aims to provide evidence-based mental health services to all citizens who need them. At present the population-adjusted ratios of mental health professionals in China are very low compared to other countries, the vast majority of mental health professionals work in specialized psychiatric hospitals (most of which are situated in urban areas), the educational qualifications of mental health professionals is quite low, there are almost no clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers in the country, and there is a serious regional maldistribution of the mental health facilities and personnel that are available. Rectifying these structural problems require supporting the creation of new types of mental health professionals,[17],[19] establishing incentives that encourage more physicians and nurses to specialize in mental health, standardizing the professional training of medical personnel who work in mental health, providing preferential treatment for professionals who work in the less-developed western parts of the country, and, perhaps most importantly, understanding the incentive systems that can increase the willingness of non-specialized medical professionals – particularly those working in community settings – to provide mental health care as part of a comprehensive package of health services.

Biography

Dr. Caiping Liu graduated from the Medical College of Jiangsu University in 2006 with a bachelor's degree in medicine. She received a master's degree from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in 2009. She is currently working as a resident psychiatrist at the Shanghai Mental Health Center. Her research interest is in violent behavior among adolescents.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Ministry of Health Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC-MH 2011-3)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Patel V. Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2007;81-82:81–96. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, Gao GF, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhai JG, Zhao JP, Chen M, Guo XF, Ji F. Disease burden of mental disorders. Guide of China Medicine. 2012;10(21):60–63. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips MR, Zhang JX, Shi QC, Song ZQ, Ding ZJ, Pang ST, et al. Prevalence, associated disability and treatment of mental disorders in four provinces in China, 2001-2005: an epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2009;373:2041–2053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Provisional Regulations of Medical Professionals. Beijing: National Coordinating Group for Reform of Professional Standards; [cited 28 Oct 2013]. [Internet] Available from: http://www.people.com.cn/item/flfgk/gwyfg/1986/407203198601.html . (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.State Statistical Bureau. China Statistical Yearbook 2010. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.China Ministry of Health. 2010 Statistical Report on Development of Medical Services of China. Beijing: China Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2011. Genava: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zar HG. Biostatistical Analysis 4th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1999. pp. 563–565. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen ME. Ridit analysis, a review. Stat Neerl. 1984;38(3):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Xie F. Discussion on distribution of health human resources from the point of view of economy. Chinese Health Service Management. 2007;23(1):19–21. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Garrido-Cumbreea M, Seedat S, Mari JJ, et al. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now. Lancet. 2007;370(9592):1061–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rabin S, Shorer Y, Nadav M, Guez J, Hertzanu M, Shier A. Burnout among general hospital mental health professionals and the salutogenic approach. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(3):175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun YF, Hui W, Wu HZ. Problems and policy analysis of human resource in mental health. Health Economics Research. 2012;297(2):23–25. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HH, Phillips MR, Cheng H, Chen QQ, Chen XD, Fralick D, et al. Mental health law of the People’s Republic of China (English translation with annotations) Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry. 2012;24(6):305–321. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39(11):1759–1762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291709005224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]