Abstract

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading cause of disability worldwide. Of those patients who present to primary care with acute LBP, 40% continue to report symptoms 3 months later and develop chronic LBP. Although it is possible to identify these patients early, effective interventions to improve their outcomes are not available. This double-blind (participant/outcome assessor) randomised controlled trial will investigate the efficacy of a brief educational approach to prevent chronic LBP in ‘at-risk’ individuals.

Methods/analysis

Participants will be recruited from primary care practices in the Sydney metropolitan area. To be eligible for inclusion participants will be aged 18–75 years, with acute LBP (<4 weeks’ duration) preceded by at least a 1 month pain-free period and at-risk of developing chronic LBP. Potential participants with chronic spinal pain and those with suspected serious spinal pathology will be excluded. Eligible participants who agree to take part will be randomly allocated to receive 2×1 h sessions of pain biology education or 2×1 h sessions of sham education from a specially trained study physiotherapist. The study requires 101 participants per group to detect a 1-point difference in pain intensity 3 months after pain onset. Secondary outcomes include the incidence of chronic LBP, disability, pain intensity, depression, healthcare utilisation, pain attitudes and beliefs, global recovery and recurrence and are measured at 1 week post-intervention, and at 3, 6 and 12 months post LBP onset.

Ethics/dissemination

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Ethics Committee in June 2013 (ref number HC12664). Outcomes will be disseminated through publication in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at international conference meetings.

Trial registration number

https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?ACTRN=12612001180808

Keywords: Pain Management, Preventive Medicine, Primary Care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This randomised controlled trial will investigate a new, simple and inexpensive approach to treating patients at-risk of developing chronic low back pain (LBP).

A sham-controlled design is being implemented to control for non-specific effects of therapist–patient interaction.

Only those individuals identified as being at-risk of chronic LBP will be included to minimise the potential influence of natural recovery on the estimation of treatment effect.

Therapist blinding is not possible.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is very common1 2 and the leading cause of disability worldwide.3 Not everyone who gets LBP will develop chronic LBP (more than 3 months’ duration), in fact, most do not.4 Although 60% of people who have LBP recover in a few weeks,5 and often with minimal intervention,6 for the other 40%, recovery is slow and the risk of long-term symptoms, or chronic LBP, is high. For patients who develop chronic LBP,7 research has consistently shown that treatments are seldom effective in returning them to a pain-free or productive life.8–11 These people face a downward spiral of increasingly lengthy periods of pain and disability with substantial social and personal disadvantage.1 Most of the costs associated with LBP can be attributed to patients with chronic symptoms.12

Evidence for preventing chronic LBP

Attempts to prevent chronic LBP have typically treated all patients with acute LBP with the same intervention focused on either biomechanics,13 fear avoidance,14 work and social factors15 or exercise.16 17 That these approaches have not been successful18 may be due, at least in part, to the positive natural history of acute LBP for the majority of patients, resulting in a large Number Needed to Treat (NNT). A more logical approach would be to target interventions to patients ‘at-risk’ (elevated risk) of poor outcome.19

Identifying patients at-risk of chronic LBP

A number of prospective cohort studies have identified characteristics of patients who are at-risk of developing chronic LBP.4–6 20 Screening tools have been developed so that treatments can be targeted towards those at-risk of developing chronic LBP,21 22 and have shown promising results.23 However, the predictive validity of these tools is often reduced when applied to samples which are different from that in which the tool was developed.24 25 Indeed, the relative contribution of each factor and the validity of cut-off scores for classifying at-risk individuals appears to vary substantially between study samples.26 Considering these limitations data from the same target population, acute LBP in Australian primary care,5 were used to identify those patients who are at-risk of developing chronic LBP.

Pain biology education

International guidelines recommend educating patients with acute LBP to reduce fear and concern about their LBP, and to promote an active recovery.27 Education is a treatment option that is simple, inexpensive and readily used by primary care practitioners.

One educational approach that has not been tested to prevent chronic LBP is pain biology education, or ‘explaining pain’. Explaining pain aims to reconceptualise pain as a protective output of the brain, rather than an accurate measure of tissue damage. It presents a conceptual framework that is based on biological processes that are accepted in the pain science community, but only recently introduced to people in pain. This framework integrates the various cognitive, social and contextual factors that modulate pain, and the appropriateness of a biopsychosocial approach to management and rehabilitation.28

Experimental studies have shown that pain biology education changes pain-related attitudes and beliefs29 and reduces catastrophising (holding a overly pessimistic interpretation of one's symptoms and prognosis) in people with chronic or sub-acute pain and in pain-free individuals.30–33 A blinded randomised experiment showed that pain biology education increased pain threshold during a straight leg raise test, in contrast to explaining lumbar spine physiology and anatomy, which decreased pain threshold during the same test.29 Pain biology education can also reduce pain and disability in people with chronic pain.33 34 These findings have been replicated in distinct chronic pain disorders in different language and cultural groups by independent researchers,33 35 36 and are supported by systematic review and meta-analysis level evidence.34

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary hypothesis of this study is that the addition of pain biology education to clinical guideline-based care for acute LBP will reduce the intensity of LBP at 3 months.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives are to determine whether pain biology education (a) increases recovery and decreases disability, depression, pain-related beliefs and healthcare utilisation (b) effects can be maintained at 6 and 12 months.

Methods

Setting

Participants will be recruited from primary care (general practitioner and physiotherapy) practices in the Sydney metropolitan area.

Target population

Participants identified in primary care will be eligible for the study if they fulfill the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Aged 18–75 years;

The primary symptom is LBP with or without leg pain;

A new episode of LBP,37 ie, current pain preceded by ≥1 month without LBP;

Average pain intensity ≥3/10 on numeric rating scale (NRS)7 during the past week;

The duration of current symptoms <6 weeks;

At-risk of developing chronic LBP (at-risk status will be determined using responses to seven questions found to be predictive of chronic LBP by Henschke et al 5: self-rated general health, presence of leg pain, previous episodes, compensation status, current pain intensity, depressive feelings and self-perceived risk of persistence);

Sufficient fluency in English language to understand and respond to English language and questionnaires

Exclusion criteria

Chronic (ie, >3 months’ duration) spinal pain (intensity NRS>1/10);

Known or suspected serious spinal pathology (eg, cauda equina syndrome, inflammatory arthritis, malignancy etc.);

Previous spinal surgery;

Uncontrolled mental health condition (eg, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder) that precludes successful participation.

Recruitment

A primary care practitioner will provide a potential participant with an information sheet containing details of the study and contact study researchers with the contact details. Study researchers will contact the potential participant within 24 h to screen for study eligibility.

Eligible participants will then be given an appointment with the study physiotherapist at either the referring practitioners’ rooms, a physiotherapy practice or at Neuroscience Research Australia. On the morning of the first appointment with the study physiotherapist, participants will be given a reminder phone call to check they still have LBP (ie, average pain intensity ≥3/10 in the past week7). The intervention will take place within 6 weeks of LBP onset. Immediately before treatment, time will be given for any questions to be addressed, written informed consent will be obtained, and all participants will be reminded to continue with the care provided by their primary care clinician for their LBP. The second session will be scheduled no more than 2 weeks after the first session, so that study treatment will be completed while participants are in the ‘acute’ phase of LBP (less than 6 weeks’ pain duration). Participants will be contacted to remind them of their appointments.

Treatment allocation and randomisation

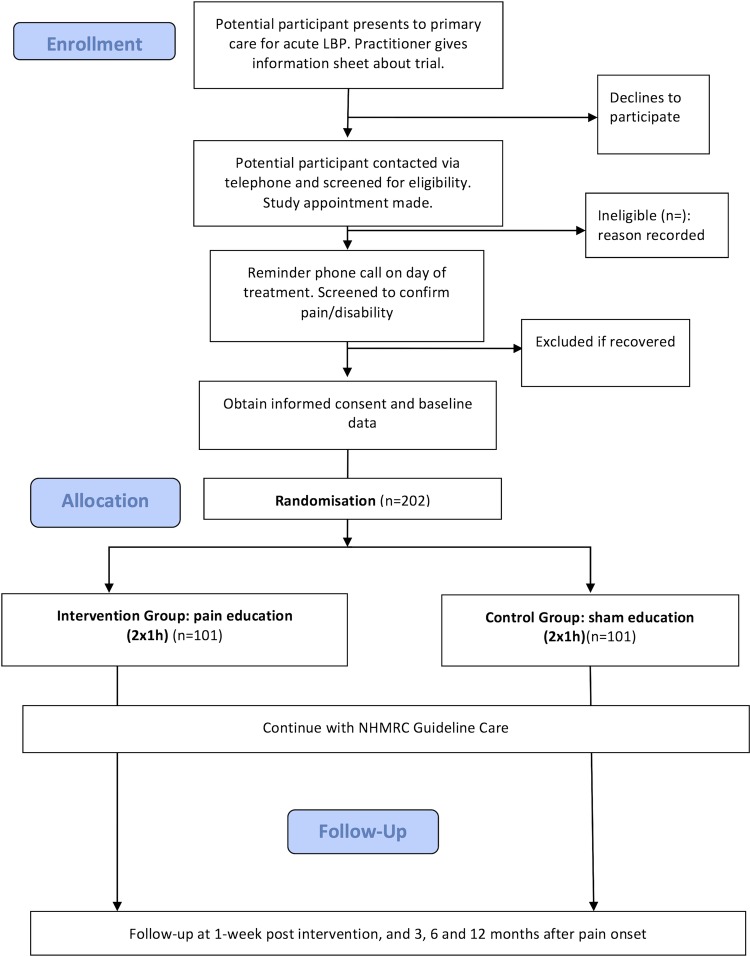

A block randomisation schedule will be created using a computer-generated random number table, to allocate participants to one of the two treatment arms: ‘pain biology education’ or ‘sham education’. The schedule will be generated by a statistician who is not involved in any other aspect of the study, and all researchers will be blinded to block size(s) and randomisation list. Sealed, sequentially numbered opaque envelopes will be used to ensure allocation concealment. A member of staff, not involved in the trial, will prepare the envelopes. Once the study physiotherapist will obtain informed consent and baseline data, the participant will be given a study number, an explanation of the study and a short history and physical examination. The randomisation envelope with the same study number of the participant will then be opened. Participants in both treatment arms will continue to receive guideline care from their primary care practitioner. Participant progress through the study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial design.

Blinding

All outcome assessors and participants will be blinded to group allocation. The statistician conducting the primary data analysis will also be blinded to group allocation. The study physiotherapist delivering the intervention will not be blinded to group allocation due to the nature of the intervention being tested.

Interventions

Features of brief pain education and sham education are compared with the ‘traditional’ and guideline approach in online supplementary appendix A.38 39

Guideline care

All participants will receive current guideline care from their primary care providers in addition to the study interventions. Participating clinicians will be given a booklet and trained on the delivery of care based on the Australian National Medical and Research Council guideline for recent onset LBP.40 In general, the guideline recommends that after performing diagnostic triage, first-line care should consist of advice, reassurance and analgesic medication. Participants will be reassured of the benign nature of LBP, advised to remain active and avoid bed rest and instructed in the use of simple analgesics to manage their symptoms. The practitioner may consider second-line options such as spinal manipulation if the participant does not respond to first-line care.

Physical examination

The study physiotherapist will conduct a physical examination of all participants prior to group allocation. The examination will involve active movement assessment, palpation and neurological testing. Findings, for example, movement restriction, tenderness and/or neurological signs will be used as discussion points during the education intervention.

Pain education

Participants randomised to the pain education intervention will participate in 2× 1 h sessions of pain education by the specifically trained study physiotherapist. The educational programme includes the following three broad components: (i) reframe any unhelpful beliefs about the nature of LBP; (ii) present key concepts of pain biology; (iii) evaluate understanding and discuss recovery.

Part (i). Reframe any unhelpful beliefs about the nature of LBP

The study physiotherapist will identify any unhelpful beliefs, those that have been found to be associated with poor recovery from LBP, such as poor recovery expectations, intentions to avoid activity due to fear of damage and beliefs concerning a reliance on passive treatment approaches.26 These beliefs will be addressed by discussing any potentially unhelpful diagnostic, prognostic or therapeutic conclusions that the participant might have made. For example, a participant may express concern about a ‘disc slipping out’ with bending tasks at work. This belief will be identified to the participant as understandable, but inaccurate and unhelpful. Less threatening, evidence-based information will then be provided about the nature of the intervertebral disc, its inability to ‘slip’ and its relationship to LBP. The inherent strength and stability of spinal structures will be emphasised.41

Part (ii). Present key concepts of pain biology

Part (ii) introduces the key aspects of pain biology and is designed to complement part (i) as well as explanations given by the primary care provider. Topics have been adapted for the acute LBP population from previous work on pain education.29 Pain will be presented as being a protective output of the brain that is influenced by many factors, rather than being a robust signal of tissue damage. More specifically, participants will be taught that: nociceptive input is modulated at the tissues, spinal cord and brain; the brain evaluates many inputs before selecting a response; pain is the conscious part of the response. This explanation provides support for current guideline instructions. For example, instructions such as ‘hurt doesn't equal harm’, ‘stay active’ and ‘return to work as soon as possible’,27 will be discussed in the context of evidence from pain biology.

Research has shown that the concepts of pain education can be understood by participants from a wide-range of socioeconomic and educational backgrounds31 and that metaphors and stories are a useful way to present complex and new information.42 Metaphors are meant to provoke contemplation and increase the potential for re-organisation of previous thoughts about pain. Metaphors will be used to both reframe unhelpful beliefs (part i) and present new concepts, in accordance with established principles of conceptual change (see ref. 43 for review).

In summary, the key concepts to be presented by the pain education are:

Pain is a protective mechanism, not necessarily a symptom of damage

In acute LBP, the system can become overprotective (sensitisation)

How one makes sense of their pain is an important factor for recovery

Part (iii). Evaluate understanding and discuss recovery

The final component of the intervention reinforces the concepts outlined in part (i) and (ii), and discusses recovery within these concepts. Understanding the cause of the symptoms and their variable relationship to tissue damage is discussed as the most important starting point for a good recovery. Emphasis is placed on the reliability of the tissue healing process, and the necessity of gradually returning to all activities. The explanation of pain biology in part (ii) provides evidence that rehabilitation approaches such as pacing are safe and effective. The participant is encouraged to discuss more specific aspects of rehabilitation (eg, goal setting) with their primary care provider.

Sham education

Participants randomised to the control intervention will receive 2× 1 h treatment sessions of sham education based on a ‘reflective, non-directive approach described in our previous study’.44 This approach uses active listening techniques such as paraphrasing,45 and is designed to control for time with a health professional and the empathy that occurs within a consultation. Participants randomised to this intervention will be given the opportunity to discuss their LBP and any other problems that they may have. The study physiotherapist will respond in an empathic way, but will not offer advice or information on pain, their condition or any other matter. Any questions the participant may have about the management of their LBP will be referred back to the primary care provider. We have shown that study participants find this approach to be equally as credible as advice.44

Baseline and outcome measures

In addition to clinical/ demographic data assessed at baseline (age, sex, duration of current LBP episode, number of previous episodes, other painful areas, compensation status) outcome measures and their measurement time points are outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Outcome measures

| Domain | Measures | Time point* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Pain | Pain intensity: 0–10 NRS average pain in the past week7 | 12 |

| Secondary | Chronic LBP | ≥2/10 pain intensity (yes/no); no periods of recovery (yes/no) | 12 |

| Disability | Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire46 | 0, 1, 12, 26, 52 | |

| Disability NRS: 0–10 current and average disability in the past week7 | 0, 1, 12, 26, 52 | ||

| Depression | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale47 | 0, 1, 12 | |

| Pain | Pain Intensity NRS: current and average disability in the past week7 | 0, 1, 26, 52 | |

| Catastrophising | Pain Catastrophising Scale48 | 0, 1 | |

| Credibility | Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire49 | 1 | |

| Healthcare utilisation | Medication | 12, 26, 52 | |

| Visits for LBP | 12, 26, 52 | ||

| Treatment type | 12, 26, 52 | ||

| Global change | Global Back Recovery Scale50 | 12 | |

| Pain-free and disability-free periods | Periods >1 week no pain or disability | 12 | |

| Recurrence | >2 episodes lasting >24 h, >2/10 pain intensity, and 30 days pain free in between37 | 26, 52 | |

| Neuroscience knowledge | Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire51 | 0, 1 | |

| Attitudes and beliefs | Survey of Pain Attitudes Two-item Version52 | 0, 1, 12, 26, 52 | |

| Back Beliefs Questionnaire53 | 0, 1 | ||

| Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire21 | 0, 1 | ||

| Self efficacy | Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire54 | 0, 1 | |

| Reassurance | Nothing seriously wrong55 | 0, 1 | |

| Further investigations required56 | 0, 1 |

*Time points: 0=baseline; 1=1 week after intervention; 12, 26 and 52=weeks after pain onset.

NRS, numeric rating scale.

After the final study treatment, participants will be given a package containing all follow-up questionnaires. They will be contacted via SMS, email or telephone prior to the follow-up assessments to remind them to complete the questionnaires. They will be telephoned at 2 weeks post-treatment, then 3, 6 and 12 months after the reported date of pain onset to transcribe the results of the questionnaires over the phone. Alternatively questionnaires will be available for participants to complete online.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be self-reported pain intensity (NRS)7 at 3 months following the reported onset of symptoms. The 3 month follow-up time point was chosen for the primary outcome as this is the most common definition of chronic LBP57 58 and reflects the time when a clear change in prognosis occurs.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes will include the proportion of participants who have chronic LBP at 3 months. A participant will be determined as having chronic LBP if he or she has pain intensity (‘In the past week, on average, how intense was your pain on a 0–10 scale where 0 is ‘no pain’ and 10 is ‘pain as bad as it could be’ ’) ≥2/10 and no periods of recovery in the last 3 months.6

Additional secondary outcomes to be assessed via self-report questionnaire will be disability (Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire,46 Disability NRS: 0–10 current and average disability in the past week7), depression (Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale47), catastrophisation (Pain Catastrophising Scale48), credibility (Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire49), healthcare utilisation, global change (Global Back Recovery Scale50), pain- and disability-free periods (periods >1 week no pain or disability), recurrence (>2 episodes of low back pain lasting >24 h, >2/10 pain intensity and at least 30 days pain free between37), neurobiology knowledge (Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire51), pain-related attitudes and beliefs (Survey of Pain Attitudes Two-item Version;52 Back Beliefs Questionnaire;53 Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire21), self-efficacy (Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire54) and reassurance (nothing seriously wrong;55 further investigations required56).

Data and treatment integrity

Trial data integrity will be monitored by regularly scrutinising data files for omissions and errors. All data will be double entered and the source of any inconsistencies will be explored and resolved. Treatment integrity will be checked by audio recording interventions. Ten per cent of recordings will be randomly selected and integrity determined by two independent assessors who are experts in the field.

Sample size calculations

Sample size was calculated using the Stata sample size calculation method for cluster randomised trials.59 With four repeated observations, an estimated intra-cluster correlation (correlation between the observations) of 0.4, α set at 5%, and allowing for 15% loss to follow-up, 101 participants are required in each group to have 80% power to detect a difference in pain intensity of 1 point (SD of 3) on the NRS at 3 months. In these calculations the increase in statistical power conferred by baseline covariates has been conservatively ignored.

Statistical analysis

The data will be analysed by intention-to-treat and by a statistician blinded to group allocation. The effect of treatment will be analysed separately for each outcome using linear mixed models with random intercepts for individuals to account for correlation of repeated measures. Estimates of the effect of the intervention and 95% CI will be estimated by constructing linear contrasts to compare the adjusted difference in means or proportions at each time point between the treatment and control groups.

Conclusion

This trial has been designed to provide robust data on the efficacy of a brief educational treatment aimed at preventing chronic LBP. The results have the potential to change how LBP is managed in primary care.

Footnotes

Contributors: JHM and GLM conceived the idea for the trial. GLM, JHM, ACT and MKN were responsible for developing the interventions. The trial was designed by JHM, MH, HL and ACT. ACT prepared the first draft of the manuscript. Successive drafts were contributed by ACT, GLM, MH, HL, IWS, NH, JMH, KMR and JHM. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

Funding: This work is supported by NHMRC grant number APP1047827. GLM supported by research fellowship NHMRC ID 1061279.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: University of New South Wales Human Ethics Committee, June 2013 (ref number HC12664).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, et al. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2012;379:482–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croft C, Blyth FM, van der Windt D. Chronic pain epidemiology: from aetiology to public health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menezes Costa LC, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, et al. The prognosis of acute and persistent low-back pain: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184:E613–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Can rate of recovery be predicted in patients with acute low back pain? Development of a clinical prediction rule. Eur J Pain 2009;13:51–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, et al. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 1992;50:133–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado LA, Maher CG, Herbert RD, et al. The effectiveness of the McKenzie method in addition to first-line care for acute low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med 2010;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(7):CD002014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LO, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Motor control exercise for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys Ther 2009;89:1275–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macedo LG, Latimer J, Maher CG, et al. Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2012;92:363–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD. Low back pain in Australian adults: the economic burden. Asia Pac J Public Health 2003;15:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahar T, Cohen MJ, Ne'eman V, et al. Insoles for prevention and treatment of back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD005275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George SZ, Fritz JM, Bialosky JE, et al. The effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine 2003;28:2551–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heymans MW, van Tulder MW, Esmail R, et al. Back schools for non-specific low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(4):CD000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell JA, Burnett A. Exercise for the primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of low back pain in the workplace: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:8–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi BK, Verbeek JH, Tam WW, et al. Exercises for prevention of recurrences of low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010(1):CD006555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bigos SJ, Holland J, Holland C, et al. High-quality controlled trials on preventing episodes of back problems: systematic literature review in working-age adults. Spine J 2009;9:147–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent P, Kjaer P. The efficacy of targeted interventions for modifiable psychosocial risk factors of persistent nonspecific low back pain—a systematic review. Man Ther 2012;17:385–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa Lda C, Maher CG, McAuley JH, et al. Prognosis for patients with chronic low back pain: inception cohort study. BMJ 2009;339:b3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:1891–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:632–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1560–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritz JM, Beneciuk JM, George SZ. Relationship between categorization with the STarT Back Screening Tool and prognosis for people receiving physical therapy for low back pain. Phys Ther 2011;91:722–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Traeger A, McAuley JH. STarT Back Screening Tool. J Physiother 2013;59:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, et al. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (‘yellow flags’) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther 2011;91:737–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J 2010;19:2075–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain pain. Noigroup Publications, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain 2004;8:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moseley GL, Nicholas MK, Hodges PW. A randomized controlled trial of intensive neurophysiology education in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain 2004;20:324–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moseley L. Unraveling the barriers to reconceptualization of the problem in chronic pain: the actual and perceived ability of patients and health professionals to understand the neurophysiology. J Pain 2003;4:184–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan CG, Gray HG, Newton M, et al. Pain biology education and exercise classes compared to pain biology education alone for individuals with chronic low back pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Man Ther 2010;15:382–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meeus M, Nijs J, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. Pain physiology education improves pain beliefs in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared with pacing and self-management education: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91:1153–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, et al. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011;92:2041–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Oosterwijck J, Meeus M, Paul L, et al. Pain physiology education improves health status and endogenous pain inhibition in fibromyalgia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2013;29:873–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Oosterwijck J, Nijs J, Meeus M, et al. Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: a pilot study. J Rehabil Res Dev 2011;48:43–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanton TR, Latimer J, Maher CG, et al. A modified Delphi approach to standardize low back pain recurrence terminology. Eur Spine J 2011;20:744–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henrotin YE, Cedraschi C, Duplan B, et al. Information and low back pain management: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:E326–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waddell G, Nachemson AL, Phillips RB. The back pain revolution. Churchill Livingstone Edinburgh, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 40.NHMRC. Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain Canberra, 2003

- 41.Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:473–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallagher L, McAuley J, Moseley GL. A randomized-controlled trial of using a book of metaphors to reconceptualize pain and decrease catastrophizing in people with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 2013;29:20–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moseley G, Butler D, Beames T, et al. The graded motor imagery handbook. Adelaide: NOIgroup Publishing, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pengel LHM, Refshauge KM, Maher CG, et al. Physiotherapist-directed exercise, advice, or both for subacute low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:787–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy: its current practice, implications and theory. Houghton Mifflin Boston, 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: Development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8:141–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovibond S, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2000;31:73–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hush JM, Kamper SJ, Stanton TR, et al. Standardized measurement of recovery from nonspecific back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:849–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Catley MJ, O'Connell NE, Moseley GL. How good is the Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire? A Rasch analysis of psychometric properties. J Pain 2013;14:818–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jensen MP, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, et al. One- and two-item measures of pain beliefs and coping strategies. Pain 2003;104:453–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Symonds TL, Burton AK, Tillotson KM, et al. Do attitudes and beliefs influence work loss due to low back trouble? Occup Med (Lond) 1996;46:25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;11:153–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller PM, Kendrick DMD, Bentley EM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lumbar spine radiography in primary care patients with low back pain. Spine 2002;27:2291–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Speckens AEM, Spinhoven P, Van Hemert AM, et al. The Reassurance Questionnaire (RQ): psychometric properties of a self-report questionnaire to assess reassurability. Psychol Med 2000;30:841–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Vet HC, Heymans MW, Dunn KM, et al. Episodes of low back pain: a proposal for uniform definitions to be used in research. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:2409–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Von Korff M, Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:2833–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013 [Google Scholar]