Abstract

Objective

Sociodemographic changes in Norway and other western industrialised countries, including family structure and an increasing proportion of cohabiting and divorced parents, might affect the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity issues. We aimed to examine whether parental marital status was associated with general and abdominal obesity among children. We also sought to explore whether the associations differed by gender.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

127 primary schools across Norway.

Participant

3166 third graders (mean age 8.3 years) participating in the nationally representative Norwegian Child Growth Study in 2010.

Measurements

Height, weight and waist circumference were objectively measured. The main outcome measures were general overweight (including obesity; body mass index ≥25 kg/m2) using International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) cut-offs and abdominal obesity (waist-to-height ratio ≥0.5) by gender and parental marital status. Prevalence ratios, adjusted for possible confounders, were calculated by log-binomial regression.

Results

General overweight (including obesity) was 1.54 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.95) times more prevalent among children of divorced parents compared with children of married parents, and the corresponding prevalence ratio for abdominal obesity was 1.89 (95% CI 1.35 to 2.65). Formal tests of the interaction term parental marital status by gender were not statistically significant. However, in gender-specific analyses the association between parental marital status and adiposity measures was only statistically significant in boys (p=0.04 for general overweight (including obesity) and p=0.01 for abdominal obesity). The estimates were robust against adjustment for maternal education, family country background and current area of residence.

Conclusions

General and abdominal obesities were more prevalent among children of divorced parents. This study provides valuable information by focusing on societal changes in order to identify vulnerable groups.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is representative of the Norwegian population of 8-year-old children.

Anthropometric data were objectively measured; additionally accompanied by register-based data of parental marital status, maternal education and family country background.

Data on parental marital status were a ‘snapshot’ of current status with no further information of how long the parents had been married, cohabiting or divorced.

There were no data on physical activity or diet, which could have contributed to further elucidate the differences.

Introduction

Childhood obesity has major public health implications.1 The factors accounting for the burden of overweight and obesity are not yet fully understood.2 Family structure has undergone major changes over the past few decades. The number of divorces increased between 1975 and 2005 and has then remained at a high level in Norway.3 About 25% of children live either the entirety or some part of their childhood with only one of their biological parents or grow up living in two different homes.4 Marital conflict and dissolution impact on the well-being of children and may have implications for the future health status of children.5 6 Differences in sedentary behaviour and diet habits between children from single-parent and dual-parent households have been reported.7 Recent studies have reported an association between family structure and childhood overweight and obesity, suggesting that living with either only one parent or divorced parents increases the risk of childhood overweight and obesity.7–10

The fact that in recent decades there have been large sociodemographic changes in Norway and in Western countries generally, with an increasing proportion of cohabiting and divorced parents, makes it important to examine the impact these changes have had on childhood overweight and obesity patterns. An additional concern is that over the past few decades waist circumference (WC) has exceeded trends in body mass index (BMI) in child and adult populations.11–13 This is important because a more central distribution of fat, measured as WC, is associated with metabolic complications.14 15 The current study supplements this literature providing insight into the association between family structure and the prevalence of both general and abdominal obesity.

Using data from a nationally representative study, our primary objective was to examine the association between parental marital status and general overweight and obesity in addition to abdominal obesity among Norwegian third graders (aged 8–9 years). In addition, we explored whether there were gender differences within these associations, and whether the main associations were independent of maternal education, family country background and area of residence.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from the Norwegian Child Growth Study (NCG) were used.16 NCG followed the protocol of the WHO Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI),17 which has previously been described in detail.18 19

Subjects

A nationally representative sample of 3166 third graders (1537 girls and 1629 boys) participated in the 2010 NCG; mean age 8.3 (SD 0.3) years. To ensure a national representative sample, a stratified two-stage sampling design was used. The attendance rate was 89% of all invited children. Data on parental marital status were available for 3137 of the children (99%), while additional data on maternal education were available for 2968 of the children (94%).

Data collection

Measurements were performed by trained school nurses at participating schools during October 2010. Each of the scales and stadiometers used in this study were already present at each school, that is, brand and type model probably differed from one school to another. One SECA measuring tape (SECA GmbH Hamburg, Germany) was distributed to each participating school. All school nurses were trained in anthropometric measures according to standardised procedures, which were explained and illustrated in a booklet specially developed for the NCG. Correction values were collected for each instrument involved in the survey and the measures of each child were corrected.18 19

Anthropometric measurements

Body weight and height were measured with the children wearing light indoor clothing and without shoes, and were recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively.20 Measures were corrected if the child wore items other than light indoor clothing: plus 100 g for some additional light clothing or plus 500 g for heavier clothing. BMI was calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2) and children were classified as overweight (including obesity) based on age-specific and gender-specific cut-off values for BMI for children as developed by the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF)21 and the WHO definitions for children aged 5–19.22 WC was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with arms hanging relaxed along the body with a measuring tape midway between the lower rib margin and the iliac crest.19 Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated as WC/height (cm/cm). At data entry, height, weight and WC were entered twice, with any punching errors corrected.

Outcome variables

The continuous outcome variables included weight, height, WC, BMI and WHtR. The main outcomes were the categorical variables overweight (including obesity; BMI≥25 kg/m2) referred to as general overweight and obesity and WHtR ≥0.5 (WHtR≥0.5) referred to as abdominal obesity. Adiposity is used occasionally and refers to general overweight and obesity, and abdominal obesity.

Explanatory variables

Data on parental marital status were obtained from the National Population Registry and compiled by Statistics Norway. Data were linked using the unique 11-digit personal identification code assigned to all Norwegian residents. Parental marital status was categorised into three groups: married, never married (including cohabiting, single and separated parents) and divorced.23

Data on highest attained maternal education were obtained from the National Education Database and categorised according to the Norwegian Standard Classification of Education (NUS2000) into three levels: tertiary, secondary and primary.19

Family country background was classified into three groups: Norwegian/Scandinavian, non-Western and Western (other than Norwegian/Scandinavian). Area of residence was classified as: urban, semiurban and rural.19

Statistical analyses

Mean and SD for the continuous variables were reported for all children, and gender stratified. Crude prevalence of general overweight and obesity, and abdominal obesity were calculated with 95% CI. Comparisons of difference in anthropometric characteristics between subgroups were performed by F test for continuous variables and Pearson χ² test for categorical variables. As a recommended alternative for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies,24 we used generalised linear models (log-binomial regression) with a logarithmic link function to calculate prevalence ratio (PR) and with an identity link function to calculate prevalence differences. It is especially when the outcome is common (>10%) that OR overestimates the PR. The effect of parental marital status on adiposity in boys and girls was tested in the regression models by the inclusion of the interaction terms parental marital status by gender. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.12 and with survey-prefix command (svy) to take into account the complex two-stage sampling procedure. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Consent forms and detailed information about the study were sent to parents/guardians beforehand. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent/legal guardian via the school nurse prior to the study.

Results

As previously reported, the prevalence of general overweight (including obesity) according to IOTF definitions was 19% and according to WHO definitions the prevalence was 28.6%, while 8.9% had abdominal obesity. Overall, general overweight (including obesity) was significantly more prevalent among girls compared with boys (p value for difference=0.03), whereas there was no gender difference for abdominal obesity (p value=0.82).19

In gender collapsed analyses all the mean values of the anthropometric measures were significantly higher for children of divorced parents compared to children of married parents, except for height (table 1). In gender-specific analyses, however, these differences were generally larger for boys than girls, and reached statistical significance only among boys; weight (p=0.04) and WC (p=0.03). The same pattern was found in terms of the categorical variables; in gender-specific analyses the difference between children of married and divorced parents was only significantly different among boys (table 2).

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics by parental marital status, presented as mean and SD, for all children and boys and girls separately

| Married | Never-married | Divorced | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| All children | n=2004 | n=903 | n=230 | ||

| p Value* | p Value† | ||||

| Height (cm) | 131.8 (6.0) | 131.7 (5.6) | 0.48 | 132.5 (6.4) | 0.39 |

| Weight (kg) | 29.4 (5.7) | 29.4 (5.2) | 0.76 | 30.8 (6.5) | 0.02 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.8 (2.4) | 16.9 (2.2) | 0.96 | 17.4 (2.8) | 0.03 |

| Waist (cm) | 58.3 (6.1) | 58.4 (5.7) | 0.48 | 60.3 (7.6) | <0.01 |

| WHtR | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.48 | 0.46 (0.05) | 0.02 |

| Boys | n=1017 | n=470 | n=121 | ||

| p Value* | p Value† | ||||

| Height (cm) | 132.4 (5.9) | 131.9 (5.6) | 0.16 | 133.8 (6.3) | 0.12 |

| Weight (kg) | 29.6 (5.8) | 29.2 (5.1) | 0.17 | 31.7 (6.8) | 0.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.8 (2.5) | 16.7 (2.2) | 0.59 | 17.6 (2.9) | 0.12 |

| Waist (cm) | 58.8 (6.2) | 58.4 (5.5) | 0.18 | 61.4 (8.0) | 0.03 |

| WHtR | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.49 | 0.46 (0.05) | 0.08 |

| Girls | n=987 | n=433 | n=109 | ||

| p Value* | p Value† | ||||

| Height (cm) | 131.1 (6.0) | 131.4 (5.5) | 0.71 | 131.1 (6.1) | 0.75 |

| Weight (kg) | 29.1 (5.6) | 29.5 (5.3) | 0.56 | 29.9 (6.2) | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.8 (2.3) | 17.0 (2.2) | 0.51 | 17.3 (2.6) | 0.37 |

| Waist (cm) | 57.7 (5.9) | 58.5 (5.8) | 0.21 | 59.2 (6.9) | 0.19 |

| WHtR | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.17 | 0.45 (0.05) | 0.17 |

*p Value for differences between married and never married.

†p Value for differences between married and divorced.

BMI, body mass index; WHtR, waist-to-height ratio.

Table 2.

General overweight and obesity (BMI≥25 kg/m2) according to IOTF and abdominal obesity (waist-to-height ratio ≥0.5), presented as prevalence (%) and PR (95% CI) by marital status, crude and adjusted, for all children and separately for boys and girls

| n | Crude |

Adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | PR | (95% CI) | PR | (95% CI) | ||

| General overweight and obesity | ||||||

| All children (N=3137) | 19.0 | |||||

| Parental marital status | ||||||

| Married | 2004 | 18.2 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 903 | 18.8 | 1.03 | (0.85 to 1.25) | 1.03* | (0.84 to 1.26) |

| Divorced | 230 | 28.0 | 1.54 | (1.21 to 1.95) | 1.46* | (1.16 to 1.84) |

| p Value | <0.01‡ | 0.01§ | 0.02§ | |||

| Parental marital status | ||||||

| Gender specific | ||||||

| Boys | ||||||

| Married | 1017 | 16.2 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 470 | 14.6 | 0.90 | (0.66 to 1.22) | 0.94† | (0.69 to 1.28) |

| Divorced | 121 | 27.5 | 1.69 | (1.18 to 2.44) | 1.63† | (1.11 to 2.39) |

| p Value | 0.02‡ | 0.04§ | 0.05§ | |||

| Girls | ||||||

| Married | 987 | 20.3 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 433 | 23.1 | 1.14 | (0.87 to 1.50) | 1.10† | (0.82 to 1.47) |

| Divorced | 109 | 28.5 | 1.41 | (0.97 to 2.04) | 1.34† | (0.91 to 1.98) |

| p Value | 0.16‡ | 0.19§ | 0.32§ | |||

| Abdominal obesity | ||||||

| All children (N=3137) | 8.9 | |||||

| Parental marital status | ||||||

| Married | 2004 | 8.5 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 903 | 8.2 | 0.97 | (0.71 to 1.32) | 0.97* | (0.69 to 1.36) |

| Divorced | 230 | 16.1 | 1.89 | (1.35 to 2.65) | 1.76* | (1.26 to 2.45) |

| p Value | <0.01‡ | 0.01§ | 0.02§ | |||

| Parental marital status | ||||||

| Gender specific | ||||||

| Boys | ||||||

| Married | 1017 | 8.5 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 470 | 6.7 | 0.79 | (0.54 to 1.15) | 0.85† | (0.58 to 1.24) |

| Divorced | 121 | 19.1 | 2.24 | (1.41 to 3.56) | 2.04† | (1.23 to 3.37) |

| p Value | <0.001‡ | 0.01§ | 0.03§ | |||

| Girls | ||||||

| Married | 987 | 8.5 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Ref. |

| Never married | 433 | 9.8 | 1.16 | (0.69 to 1.95) | 1.07† | (0.60 to 1.92) |

| Divorced | 109 | 12.8 | 1.51 | (0.78 to 2.95) | 1.48† | (0.77 to 2.86) |

| p Value | 0.42‡ | 0.45§ | 0.47§ | |||

*Adjusted for maternal education and gender.

†Adjusted for maternal education.

‡χ² Test.

§Test for overall p value for differences between categories.

BMI, body mass index; IOTF, International Obesity Task Force; PR, prevalence ratio.

Children of divorced parents had a 54% higher prevalence (95% CI 21% to 95%) of general overweight (including obesity) and 89% higher prevalence (95% CI 35% to 165%) of abdominal obesity compared to children of married parents (table 2), whereas children of never-married parents had a similar prevalence to children of married parents. Adjustment for maternal education and gender only slightly attenuated the associations, which indicate that maternal education and gender did not explain the association between parental marital status and childhood overweight and obesity. Similarly, the estimates were essentially unchanged after controlling for sociodemographic factors such as family's country background and their area of residence (data not shown). The crude anthropometric measures by parental marital status were essentially equal in the full sample (N=3137) and in the reduced sample with non-missing maternal education (N=2968), indicating that the reduced sample is representative of the full sample.

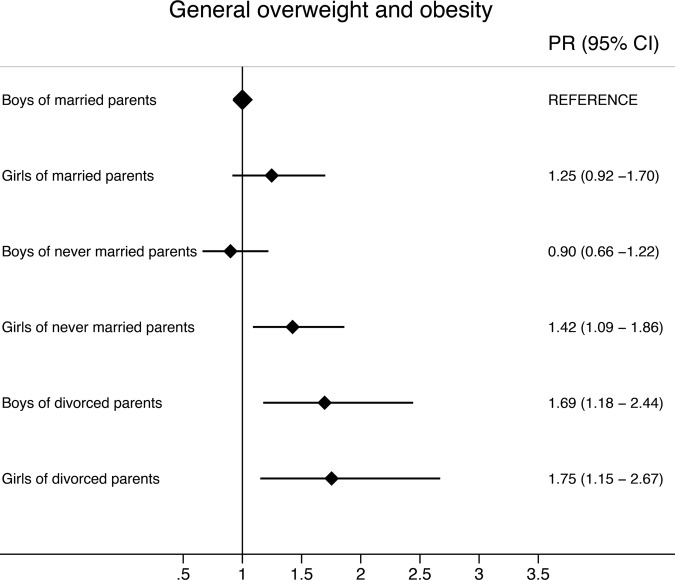

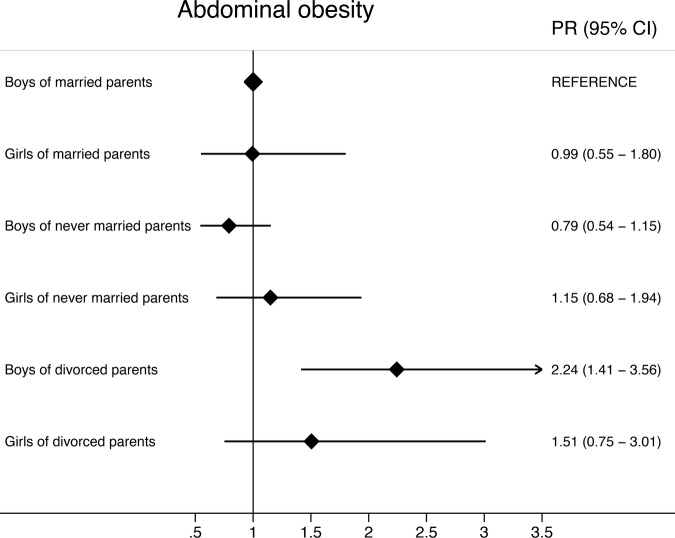

Gender stratified analyses, adjusting for maternal education, showed that boys with divorced parents had a 63% higher prevalence (95% CI 11% to 139%) of general overweight (including obesity) compared to boys of married parents (table 2), with the absolute difference being 9.9 percentage points. Correspondingly, the prevalence of abdominal obesity was 104% higher (95% CI 23% to 237%) among boys with divorced parents compared to boys of married parents (table 2), and the absolute difference was 7.4 percentage points. The same pattern was seen among girls, but the associations were less pronounced and not statistically significant. The differences between marital status categories and gender are illustrated in figures 1 and 2, suggesting that boys of divorced parents were particularly prone to abdominal obesity. However, formal tests of the interaction term parental marital status and gender was only borderline significant for WC (p=0.06), and not significant for BMI (p=0.26), WHtR (p=0.13), general overweight (including obesity; p=0.36) and abdominal obesity (p=0.27).

Figure 1.

Crude prevalence ratio (PR) of general overweight and obesity by parental marital status separately for boys and girls, where boys with married parents are the reference category, presented with 95% CI.

Figure 2.

Crude prevalence ratio (PR) of abdominal obesity by parental marital status separately for boys and girls, where boys with married parents are the reference category, presented with 95% CI.

Discussion

In this nationally representative study we found that general overweight and obesity, and abdominal obesity were more prevalent among children of divorced parents compared with children of married parents. Our findings were robust to adjustments for maternal education, family country background and current area of residence. Although formal tests of the interaction terms parental marital status by gender were not statistically significant, gender stratified analyses showed that the prevalence of general and abdominal obesity was significantly higher only among boys of divorced parents, compared to boys with married parents.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study has several limitations which ought to be considered when interpreting its findings. First, data on parental marital status were limited to a ‘snapshot’ of current status. For example, we had no information as to how long parents had been divorced. Further, the never-married category was heterogeneous and contained a diversity of family constellations, such as intact cohabiting relationships and dissolved relationships. More detailed information would have been beneficial to the study. Second, an obvious limitation is that our cross-sectional design provided no basis for studying causality; whether the development of overweight and obesity was initiated before the divorce or whether the impact on the children's weight status was primarily attributed to marital conflict or the divorce. Third, one cannot exclude the possibility that a higher proportion of overweight children were absent from school on the day measurements were taken and were therefore over-represented among non-participants, which in turn could imply that children of divorced parents were under-represented in NCG, as previously stated.25 If so, the associations shown in this study could be underestimated, but, given that the children were recruited into the NCG by the school health service, selection bias is most likely not a big issue in our study. Finally, the explanatory variables are few in the current study, with no information on, for example, physical activity level or dietary behaviour among the children, meaning that we cannot further explore our findings. On the other hand, high attendance rate was given high priority in NCG. In order to avoid non-participation parents were thus not requested to fill in time-consuming questionnaires. Few explanatory variables could therefore be considered an advantage for the current study. Another obvious strength is that, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study with objectively measured and systematically collected anthropometric data of a nationally representative sample, and is accompanied by register-based data on parental marital status, parents’ level of education, area of residence and country background for each child. Moreover, the NCG has a high attendance rate (89%).

Our finding that parental divorce is associated with childhood overweight and obesity is consistent with previous studies.7–10 Few other studies have studied gender differences, but one Australian study found an opposite gender pattern, though the gender-specific associations were not statistically significant.7 10 A Norwegian study concluded that single-parent families were not significantly associated with overweight and obesity among children aged 2–19 years.26 The divergent findings most probably reflect a lack of agreement in terms of categorisation. The dichotomisation of marital status does not tell whether a single-parent family is the result of divorce, separation or death or indeed whether a two-parent family is cohabiting or married. Accordingly, it does not form a solid basis for examining whether changing family structures or ‘divorce stress’ during childhood may affect weight status among children. Other studies have also contained methodological limitations and were either based on small samples, self-reported data and/or marital status was reported at birth.27–30 Likewise, a review considering risk factors for childhood overweight and obesity found conflicting evidence for maternal marital status.31 Only three studies were included, all of which measured marital status at birth.

Further, we found that children of never-married parents shared similar adiposity traits with children of married parents. The similarity most likely reflects the heterogeneity of the never-married category, as mentioned in the limitation section above. This category could still be interesting to investigate further; a four times higher risk of dissolution of relationship has been shown for cohabiting couples as opposed to married couples,32 and the proportion of cohabitations compared to marriages has increased steadily since 1980.5

The excess risk of adiposity among those with divorced parents remained after adjusting for maternal education, despite the fact that maternal education is the strongest single-socioeconomic predictor of childhood obesity,33 and divorced parents are more likely to have lower educational level, as reported by a Norwegian study.34

One can speculate as to whether the changing structure of daily life has a large effect on the children of divorced parents (living with only one parent or spending half their time with the mother and/or the father). The loss of various resources, like the absence of one of the parents or the loss of a parental figure, usually the father, can explain the negative implications of divorce.6 35 36 A consequence might be less time for domestic tasks such as cooking and reliance on more convenient, ready-to-eat foods. As processed foods tend to be higher in fat and calories and lower in nutritional value8 the result is an altered, less healthy diet. The household income and support from any non-custodial parent or the welfare state is often lower than in corresponding non-disrupted families.37 Consequently, fewer economic resources may be available for divorced parents, which might lead to cheaper and less healthy choices. Other mechanisms affecting children's weight status through divorce (or dissolved relationship) could be related to emotional stress. Disruption in the parent–child relationship, continuing conflict between former spouses or other negative events like moving and the need to establish new networks could induce emotional stress.35–37 It has been shown that adolescents with substantial distress symptoms doubled among those with divorced parents.38 Such emotional stress may impact on eating behaviour and physical activity level and thus explain the development and maintenance of childhood overweight and obesity.7 8 39

The higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among children of divorced parents may also be due to selection. Health, socioeconomic resources, psychological characteristics, values and preferences affect the chance of marrying and remaining married, and has previously been found to account for some of the differences between children of divorced and married parents.35 40

In the present study, children of separated parents were categorised together with children of never-married parents. From a perspective regarding selection as the main explanation, it could be argued that children of separated parents are miscategorised, since these parents will in the future most likely divorce, and are as such akin to divorced parents.

In this nationally representative study of third graders, we found that general overweight and obesity, and abdominal obesity were more prevalent among children of divorced parents compared to children of married parents, even though the divorced category was rather small and the results should be interpreted cautiously. The association remained after adjusting for maternal education, family country background and area of residence. Formal tests of interaction terms parental marital status by gender were not statistically significant. However, our data suggest that boys of divorced parents seem to be particularly prone to abdominal obesity. By focusing on actual societal changes, this study adds valuable background information about potentially vulnerable groups at risk of developing adiposity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children, parents and school health nurses who contributed to the study. They also thank Øystein Kravdal for advice at an early phase of the study, Jørgen Meisfjord for data management and Matthew McGee for proofreading the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: RH was responsible for conception of the Norwegian Child Growth Study (NCG), and AB was involved in planning and data collection. AB and HEM were responsible for the conception of this paper. AB and BHS analysed the data and AB drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revisions of the paper and approved the final submitted version.

Funding: This study is a collaboration between the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the Morbid Obesity Center (Vestfold Hospital Trust in the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and funded by South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: NCG was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet 2002;360:473–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R, et al. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev 2004;5:4–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Norway. Marriages and divorces, 2013. http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/ekteskap/ (accessed 18 Mar 2014).

- 4.Statistics Norway. Families and households, 2013. http://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/familie/aar/ (accessed 22 Oct 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. J Fam Psychol 2001;15:355–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troxel WM, Matthews KA. What are the costs of marital conflict and dissolution to children's physical health? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2004;7:29–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne LK, Cook KE, Skouteris H, et al. Parental status and childhood obesity in Australia. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6:415–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yannakoulia M, Papanikolaou K, Hatzopoulou I, et al. Association between family divorce and children's BMI and meal patterns: the GENDAI Study. Obesity 2008;16:1382–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen AY, Escarce JJ. Family structure and childhood obesity, Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten Cohort. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:A50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, et al. Associations between family circumstance and weight status of Australian children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2007;2:86–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy HD, Ellis SM, Cole TJ. Central overweight and obesity in British youth aged 11–16 years: cross sectional surveys of waist circumference. BMJ 2003;326:624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolle E, Steene-Johannessen J, Holme I, et al. Secular trends in adiposity in Norwegian 9-year-olds from 1999–2000 to 2005. BMC Public Health 2009;9:389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Midthjell K, Lee CMY, Langhammer A, et al. Trends in overweight and obesity over 22 years in a large adult population: the HUNT Study, Norway. Clin Obes 2013;3:12–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels SR, Morrison JA, Sprecher DL, et al. Association of body fat distribution and cardiovascular risk factors in children and adolescents. Circulation 1999;99:541–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freedman DS, Sherry B. The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics 2009;124:S23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norwegian Institute of Public Health. The Child Growth Study. http://www.fhi.no/artikler/?id=90892 (accessed 22 Oct 2013).

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI). Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. http://www.euro.who.int/en/what-we-do/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/activities/monitoring-and-surveillance/who-european-childhood-obesity-surveillance-initiative-cosi (accessed 22 Oct 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biehl A, Hovengen R, Meyer HE, et al. Impact of instrument error on the estimated prevalence of overweight and obesity in population-based surveys. BMC Public Health 2013;13:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biehl A, Hovengen R, Grøholt EK, et al. Adiposity among children in Norway by urbanity and maternal education: a nationally representative study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO Expert Committee. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Report No. 854 Geneva, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole TJ, Bellizzini MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. The WHO Reference 2007. Growth reference data 5–19 years. http://www.who.int/growthref/en/ (accessed 22 Oct 2013).

- 23.Statistics Norway. Classification of marital status. http://www3.ssb.no/stabas/ClassificationFrames.asp?ID=417702&Language=en (accessed 22 Oct 2013)

- 24.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Regber S, Novak M, Eiben G, et al. Assessment of selection bias in a health survey of children and families—the IDEFICS Sweden-study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Júlíusson PB, Eide GE, Roelants M, et al. Overweight and obesity in Norwegian children: prevalence and socio-demographic risk factors. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:900–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen F, Johansson M, Hansen HO. Trends in overweight and obesity among 18-year-old males in Sweden between 1971 and 1995. Acta Paediatr 1999;88:431–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauss RS, Knight J. Influence of the home environment on the development of obesity in children. Pediatrics 1999;103:e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huffman FG, Kanikireddy S, Patel M. Parenthood—a contributing factor to childhood obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:2800–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray VB, Byrd SH, Cossman JS, et al. Family characteristics have limited ability to predict weight status of young children. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:1204–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:1019–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Texmon I, Cohabitatants and Society [In Norwegian: Samliv i Norge mot slutten av 1900-tallet]. Official Norwegian Reports, 1999 (NOU 1999: 25). Oslo, Statens forvaltningstjeneste. 1999 Norwegian. http://www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/bld/dok/nouer/1999/nou-1999–25/20.html?id=116773 (accessed 22 Oct 2013).

- 33.Shrewsbury V, Wardle J. Socioeconomic status and adiposity in childhood: a systematic review of cross-sectional studies 1990–2005. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:275–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyngstad TH. The impact of parent's and spouses’ education on divorce rates in Norway. Demogr Res 2004;10:121–42 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigle-Rushton W, McLanahan S. Father absence and child well-being: a critical review. In: Moynihan DP, Smeeding TM, Rainwater L, eds. The future of the family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2004:116–55 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amato PR. The consequences of divorce for adults and children. J Marriage Fam 2000;62:1269–87 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bratberg E, Tjøtta S. Income effects of divorce in families with dependent children. J Popul Econ 2008;21:439–61 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Størksen I, Røysamb E, Holmen TL, et al. Adolescent adjustment and well-being: effects of parental divorce and distress. Scand J Psychol 2006;47:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Unger JB, Spruijt-Metz D. Psychological determinants of emotional eating in adolescence. Eat Disord 2009;17:211–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steele F, Sigle-Rushton W, Kravdal Ø. Consequences of family disruption on children's educational outcomes in Norway. Demography 2009;46:553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.