Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness, efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for patients with functional constipation.

Methods and analysis

We will electronically search OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, AMED and ISI web of knowledge without any language restrictions. We will also try to obtain literatures from other sources, such as a hand search of library journals or conference abstracts. After searching and screening of the studies, we will run a meta-analysis of the included randomised-controlled trials. We will summarise the results as risk ratio for dichotomous data and standardised or weighted mean difference for continuous data.

Dissemination

This systematic review will summarise current evidence for using non-pharmacological therapies to treat functional constipation, and will be disseminated through peer-review publications or conference presentations.

Trial registration number

PROSPERO 2014: CRD42014006686.

Keywords: Complementary Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review protocol to assess the effectiveness, efficacy and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for adult patients with functional constipation.

The results of this systematic review will help clinicians in making decisions in clinical practice, and help patients with functional constipation seeking more treatment options.

Difficulty in locating all the non-pharmacological treatments for functional constipation may be the limitation of this systematic review. We will follow the several steps advised by specialists in informatics to ensure a broad search for studies.

Introduction

Functional constipation (FC) is a common clinical condition without any specific physiological causes. The prevalence of constipation ranges from 0.7% to 81% around the world,1 2 whereas the prevalence of FC varies from 2.4% to 27.2%.3–5 The mean prevalence of FC was reported to be 14% in a recent systematic review.4 FC is a chronic and refractory condition; a study showed that 89% of patients with constipation still reported constipation during a mean follow-up period of 14.7 months.5 Constipation symptoms significantly reduce patients’ quality of life (QOL), mentally and physically.2 6 Additionally, it is reported that constipation is related to a higher possibility of obesity.7 Direct cost of chronic FC for each patient ranges from $1912 to $7522/year.8 Considering that FC makes a significant impact on QOL and influences physical and emotional well-being, it should be considered as a major public health problem.

A number of therapies are used to manage constipation symptoms for patients with FC, such as laxatives, selective 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 (5-HT4) agonists, etc. Recent systematic reviews reported that laxatives, prucalopride, lubiprostone and linaclotide are effective for managing FC compared with placebo; however, more events of diarrhoea were reported.9 Similar findings were made in several recent reviews that pharmacological therapies are effective for relieving constipation symptoms, but more adverse events happen in patients receiving these treatments.10 11 Traditional herbal medicine was reported to be helpful with less adverse events in the treatment of FC; however, recent reviews concluded that more trials with rigorous design are needed to confirm the effectiveness of traditional herbal medicine for FC.12 13

Non-pharmacological therapies are popular among patients with FC; however, most of them lack supportive evidence. A systematic review reporting non-pharmacological treatments for paediatric constipation concluded that there is a lack of well-designed randomised-controlled trials to verify whether these treatments are effective.14 Although several non-pharmacological therapies were claimed to be beneficial for patients with FC,15–19 most of them lacked supportive evidence. Therefore, we raised the following questions: (1) Are non-pharmacological therapies effective and efficacious for patients with FC? (2) If so, are non-pharmacological therapies safe for patients with FC? To answer these questions, we will conduct a systematic review of non-pharmacological therapies for patients with FC, hoping to find the answers. In this article, we present a protocol for the systematic review.

Methods and analysis

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Before starting this review, we carried out a research to get a general understanding of recent studies on this topic. We found a few randomised-controlled trials. To ensure reliability of the evidence, we agreed that it was reliable and feasible to include randomised-controlled trials only for this review. Furthermore, we found that cross-over design was not common in trials studying non-pharmacological treatments because the washout periods of these interventions could not be evaluated accurately, which may bring bias to outcome assessments. Therefore, we will only include randomised-controlled trials with parallel design. We will also include trials using open label, single-blind or double-blind designs.

Types of participants

We will include participants who were diagnosed with FC according to the ROME II or III criteria in this systematic review. If the ROME II or III criteria was not mentioned, the participants will still be included only if they were excluded for specific pathological causes, such as underlying structural or metabolic diseases. We will focus on constipation in the adult population, so trials including participants with age under 18 years will be excluded.

Types of interventions

We plan to include only trials testing non-pharmacological treatments. So, after we have searched the databases, we will first exclude trials using any pharmacological interventions, including pharmaceutics, herbs, traditional medicine, etc. Second, we will include trials in which non-pharmacological treatments were used at least once a week for a minimum total of 4 weeks. Non-pharmacological interventions with different protocols of intervention procedure will be included. To assess the effectiveness of non-pharmacological treatments, we plan to compare them with positive controls. According to the guidelines and recent systematic reviews,10 20 21 laxatives, selective 5-HT4 agonists and the patient's education are reported to be effective for managing constipation, so we will set these interventions as positive controls. To assess the efficacy of non-pharmacological treatments, we plan to compare these treatments with placebo control, which includes placebo drugs, sham interventions, etc.

Types of outcome assessments

The primary outcome of this review will be the mean spontaneous bowel movements per week, from the first week after finishing all treatment sessions. Since non-pharmacological treatment sessions are different across studies, it is impossible to define an exact time point for the primary outcome. Therefore, we agreed that performing the primary outcome assessment after the end of treatment is a relatively suitable time point. The secondary outcomes will be: proportion of responders, mean transit time, proportion of patients using laxatives, QOL and proportion of adverse events. The proportion of responders is defined as the number of responders divided by the total number of participants in each group. Transit time is defined as the time from the first perception of wanting to defaecate to the finish of defaecation; we will also calculate the mean transit time. Participants who use laxatives (types of laxatives will not be limited in this review) during the trial will be counted up, and we will calculate the proportion of patients using laxatives. The outcome QOL will be measured by scales that are normally used by constipation studies, such as the Short Form 36 Health Surveys (SF-36), etc. We will sum up the number of patients reporting adverse events in each study, and calculate the proportion of adverse events.

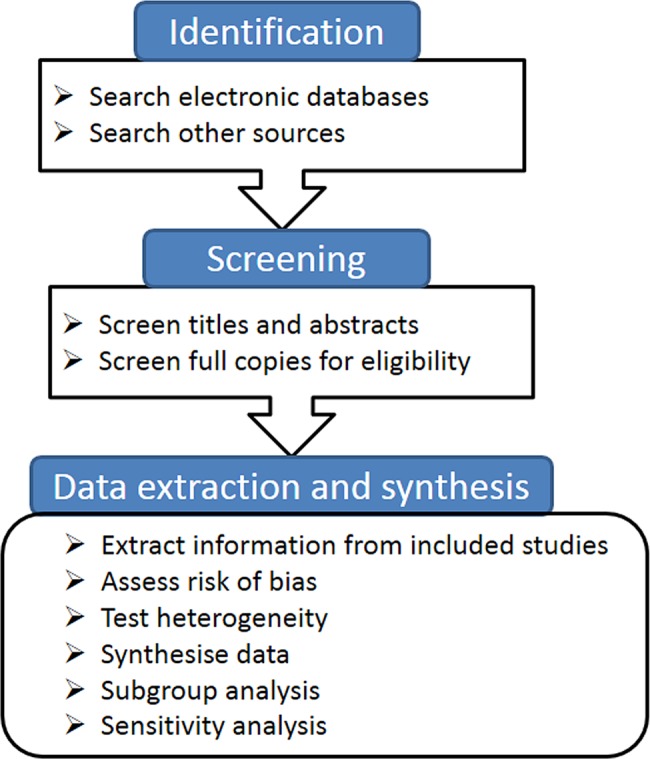

The workflow of this systematic review is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The flow chart for performing the systematic review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We will electronically search the following databases: OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane library, CINAHL, AMED and ISI web of knowledge from inception to 2014, without any language restrictions. The search strategy will be developed after a discussion among reviewers, according to the guidance of the Cochrane handbook.22 To ensure a broad search, we will include Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) such as randomised-controlled trial, constipation, etc. Titles, abstracts and subject headings will also be searched for the above MeSH words and several other words related to randomised-controlled trials, FC, etc. The search strategy for OVID MEDLINE is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy used in OVID MEDLINE database

| Number | Search terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 2 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 3 | randomized.ab. |

| 4 | randomised.ab. |

| 5 | placebo.ab. |

| 6 | randomly.ab. |

| 7 | trial.ab. |

| 8 | groups.ab. |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

| 10 | exp constipation/ |

| 11 | functional constipation. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 12 | idiopathic constipation. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 13 | slow transit constipation. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 14 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 |

| 15 | Nonpharmacological. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 16 | non pharmacological. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 17 | nonpharmacologic. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 18 | non pharmacologic. ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 19 | dietary fiber. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 20 | probiotics. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 21 | behavioral medicine. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 22 | cognitive therapy. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 23 | biofeedback. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 24 | fluid therapy. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 25 | acupuncture. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 26 | massage. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 27 | ear acupuncture. sh, ti, ab. {Including Related Terms} |

| 28 | 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 |

| 29 | 9 and 14 and 28 |

This search strategy was modified to be suitable for other electronic databases.

Other sources

Potentially eligible studies will also be obtained through the following methods:

Review the reference list of previously published reviews for possible candidates.

If possible, we will review conference abstracts to find unpublished trials, and contact the authors for data.

Hand search a list of medical journals in the university library, such as Chinese Medical Journal, etc.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Before the selection of studies, a procedure for screening will be developed by discussion among all the reviewers. After electronic searches, the output will be cited in a database created by endnote software (version X6). Studies obtained from other sources will also be cited in the same database. Two reviewers (HZ and JL) will independently screen the titles and abstracts in this database through the following steps: first, find out the duplicates (studies published in different languages, or studies published as journal articles as well as conference abstracts, or at least two articles reporting the same trial in different aspects); second, exclude studies in which participants were receiving pharmacological treatment in an experimental group or participants were diagnosed with constipation due to structural or metabolic diseases; third, exclude studies which were not designed as randomised-controlled trials with parallel design; fourth, exclude studies in which participants under the age of 18 were recruited. Full copies will be sought if the reviewers (HZ and JL) are not able to clearly screen the studies based on their titles and abstracts. Two other reviewers (MC and QC) will screen the full copies of these studies. If disagreements occur between reviewers during screening, they will be resolved through discussion and consensus. If the disagreement persists, a third reviewer (DH or JF) will be consulted.

Data extraction and management

Before data extraction, all the reviewers will discuss and develop a standardised data extraction form. We will extract information from at least three studies using this form to check its applicability. Two independent reviewers (HZ and JL) will extract the following information from the studies: organisational aspects (including reference ID, reviewer's name, the first author of the article, year of publication, publication source, etc), trial characteristics (design of the study, number of participants, number of groups, method of randomisation, method of allocation concealment, blinding, primary aims of the study, etc), participants (age, ethnicity, gender, diagnosis, concurrent conditions, laboratory parameters, etc), interventions and controls (name of the intervention, length of treatment, type and name of control, information on care providers, additional treatment, etc), outcome measurements (type of outcome, definition of the outcome, time point for assessment, length of follow-up, etc), results (name of the outcome, mean, SD, observed events after intervention, total sample size, etc) and other research information. If there is a disagreement between the two reviewers, consensus will be achieved by discussion among all the reviewers. The extraction data will be entered into R project 3.02 (http://www.r-project.org), and QC will check the data to ensure there are no data entry errors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (MC and HZ) will independently assess the risk of bias, using the Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias of the included trials,22 which is composed of six domains of a trial, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, etc. After assessing all the domains, the reviewers will summarise the assessments and categorise the included trials into three levels of bias: low, unclear and high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We will calculate the risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data during synthesis, and provide p values for comparison of the experimental group with the control group. For continuous data, we will calculate the weighted mean difference (WMD) if all the studies use the same measurement tool and the same unit, if not, we will calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD). We will calculate 95% CIs for RR, WMD or SMD.

Unit of analysis issues

In this review, we will include data from parallel design trials. If there are multiple observations at different time points, we will define data assessed within 4 weeks as short-term outcomes, and those assessed over 4 weeks as long-term outcomes. As most of the treatment length of non-pharmacological therapies will usually be at least 4 weeks, we will focus on long-term outcomes in the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

If there are missing data in the included studies, we will try to contact the authors of the included studies to get original data for analysis. If we are not able to access the missing data, we will exclude these studies and synthesise the rest of the included studies.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before this meta-analysis, we will perform a heterogeneity examination using the Higgins I2 test. We will calculate the I2 statistics to find out whether there are inconsistencies among the included trials. We will set a cut-off point of 50% for the I2 statistics. An I2>50% will be considered as a marker of significant heterogeneity among studies. In that case, we will perform a metaregression analysis to find out the source of heterogeneity. Moreover, we will run a subgroup analysis according to the source of the heterogeneity. Additionally, we will combine the outcomes using a random effects model when significant heterogeneity exists, and explain the results with caution.

Assessment of reporting biases

We will use funnel plots to assess reporting biases as well as small study effects. If 10 or more studies are included in a meta-analysis, we will use Egger's method to test funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

Data synthesis will be performed using R project 3.02 (http://www.r-project.org). For dichotomous data, we will combine RR of each study and calculate 95% CI using fixed effects model, if no heterogeneity is detected. If significant heterogeneity is found, we will combine the data using random effects model and explain the results with caution. Moreover, we will provide a p value for a comparison of non-pharmacological therapies with positive drug, sham intervention or waiting list controls. For continuous data, we will combine the WMD of each study and compute 95% CI if the same outcome measurement is used; if not, we will combine the SMD instead. Additionally, we will also choose fixed or random effects models according to the result of the heterogeneity test, and provide p values.

Subgroup analysis

Non-pharmacological treatments will include a lot of different therapies, so we will first calculate the overall effect size of all the treatments. Second, we will perform a subgroup analysis according to different non-pharmacological treatments, which is considered to be the most significant source of heterogeneity among studies. Also, we will run a subgroup analysis according to the source of heterogeneity using metaregression method.

Sensitivity analysis

First, we will assess the impact of including studies with a high risk of bias on the results of this review. We will combine all the included studies, and find out if the results are still consistent after excluding the studies with high risk of bias. Second, to clarify whether different models affect the results of data synthesis, we will combine the outcomes using fixed and random effects models, and check whether the results remain the same. Third, to assess the impact of sample size on the results of this review, we will exclude small sample size trials (<100 participants) to find out if the results are still consistent with combining all the included studies.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review does not need ethical approval because data that we used will not be linked to individual data and privacy. The results of this review will provide a general view and evidence of non-pharmacological treatments for the management of FC. The findings of this review will also give implication for clinical practice and further research, and will be disseminated by peer-review publications and conference presentations.

Discussion

In this article, we present a protocol for systematic review of using non-pharmacological treatments to treat FC, which is becoming a major public health problem. The most difficult part of this review is to define non-pharmacological interventions and to run a broad search for them. After consultation with specialists in informatics, we decided to locate the studies we want to include through three steps: first, we will use keywords related to non-pharmacological treatments; we will also use non-pharmacological interventions commonly applied in clinical practice as search keywords, such as dietary fiber, probiotics, acupuncture, moxibustion, etc. Second, after running the search strategy, we will screen the titles and abstracts to exclude studies using any pharmacological interventions. Third, we will screen the full copies of the potential studies to ensure we locate the correct studies.

The second difficult part of this review is to define the condition FC in the studies. We consulted several specialists in the field of gastroenterology who suggested that it will be better to include studies using ROME II or III as diagnostic criteria in this review. So we took their advice; moreover, we will use several keywords in addition to functional constipation, such as constipation, idiopathic constipation, etc, to ensure that we run a broad search of studies on this topic.

How to deal with missing data is also a major concern in this protocol. According to the Cochrane handbook,22 there are four options for dealing with missing data. After discussion, we agreed that analysing only the available data will be the best choice because imputing the missing data may cause bias to the results.

The strength of this review lies in that the results will give an overview of current evidence on non-pharmacological treatments for adult patients with FC. The limitations of this review may be that first, we focused on the adult population only because there is a recent systematic review studying the effectiveness of non-pharmacological therapies for paediatric constipation14; however, this may restrict the generalisation of the results. Second, we defined the primary outcome of this protocol as the mean spontaneous bowel movements per week from the first week after finishing all treatment sessions, which may introduce bias to the results since treatment session may be different across studies. But after discussion, we agreed that defining a specific time point (eg, 4 weeks after randomisation) may bring a higher risk of bias, since different studies used different assessment time points.

This systematic review will give a summary of the current evidence on the effectiveness and safety of non-pharmacological therapies for patients with FC. This review will benefit patients with FC and care providers as they will have more treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MC, HZ and JF contributed to the conception and design of the study protocol. The search strategy was developed and run by HZ and JL, who will also screen the title and abstract of the studies after running the search strategy. MC and QC will screen full copies of the remaining studies after title and abstract selection. HZ and JL will extract information from the included studies and enter into electronic database. QC will check the accuracy and completeness of the data entry. DH and JF will give analysis suggestions during data synthesis. All the authors drafted and revised this study protocol and approved for publication.

Funding: This work was supported by Open Research Fund of Zhejiang First-foremost Key Subject—Acupuncture & Tuina, grant number (ZTK2010A16), Research fund of Chengdu University of TCM, grant number (ZRZ0201104), as well as National Natural Science Foundation, grant number (81102656).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mugie SM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of constipation in children and adults: a systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2011;25:3–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, et al. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 2008;8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iraji N, Keshteli AH, Sadeghpour S, et al. Constipation in Iran: SEPAHAN Systematic Review No. 5. Int J Prev Med 2012;3(Suppl 1):S34–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1582–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:750–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belsey JD, Geraint M, Dixon TA. Systematic review and meta analysis: polyethylene glycol in adults with non-organic constipation. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:944–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pashankar DS, Loening-Baucke V. Increased prevalence of obesity in children with functional constipation evaluated in an academic medical center. Pediatrics 2005;116:e377–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nellesen D, Yee K, Chawla A, et al. A systematic review of the economic and humanistic burden of illness in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19:755–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2011;60:209–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin A, Camilleri M, Kolar G, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: highly selective 5-HT4 agonists (prucalopride, velusetrag or naronapride) in chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:239–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford AC, Brenner DM, Schoenfeld PS. Efficacy of pharmacological therapies for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1566–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin LW, Fu YT, Dunning T, et al. Efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine for the management of constipation: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:1335–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng CW, Bian ZX, Wu TX. Systematic review of Chinese herbal medicine for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:4886–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabbers MM, Boluyt N, Berger MY, et al. Nonpharmacologic treatments for childhood constipation: systematic review. Pediatrics 2011;128:753–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang T, Chon TY, Liu B, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for chronic constipation: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med 2013;41:717–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suares NC, Ford AC. Systematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarrett ME, Mowatt G, Glazener CM, et al. Systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation. Br J Surg 2004;91:1559–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MS, Choi TY, Park JE, et al. Effects of moxibustion for constipation treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Chin Med 2010;5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chmielewska A, Szajewska H. Systematic review of randomised controlled trials: probiotics for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:69–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., III American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology 2013;144:218–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: constipation—a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011;45:483–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1. 0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.