Abstract

The study described here was designed to determine treatment preferences among Latinas to identify treatment options that meet their needs and increase their engagement. Focus group interviews were conducted with 22 prenatal and postpartum Latinas at risk for depression. The group interviews were conducted in Spanish and English using a standardized interview protocol. Focus group transcripts were analyzed to identify themes regarding perinatal depression coping strategies, preferred approaches to treating perinatal depression, and recommendations for engaging perinatal Latinas in treatment. The results suggest that Latinas’ treatment preferences consist of a pathway (i.e., hierarchical) approach that begins with the use of one’s own resources, followed by the use of formal support systems (e.g., home-visiting nurse), and supplemented with the use of behavioral therapy. Antidepressant use was judged to be acceptable only in severe cases or after delivery. The data indicate that to increase health-seeking behaviors among perinatal Latinas, practitioners should first build trust.

Keywords: depression, focus groups, Latino/Hispanic people, mothers, mothering, perinatal health

Postpartum depression is the most common complication of childbirth and is associated with serious health outcomes for mothers and their children (Grace, Evindar, & Stewart, 2003). Researchers estimate that 9.4% to 12.7% of all women develop major depressive disorders during pregnancy and that 15% do so within 3 months after birth (Gaynes et al., 2005). The estimates for depressive symptoms are worrisome. For example, Zayas, Jankowski, and McKee (2003) found that in a sample of 106 prenatal Latinas, 52% reported elevated levels of depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), with symptoms declining over the course of the study among those who completed the three interviews (prenatal, 2 weeks postpartum, and 3 months postpartum). It is unclear whether those who were lost to follow-up experienced any change in symptoms (e.g., increased symptoms).

Although rates of major depression among all Latina mothers have not been estimated, the initial estimates are alarming. Yonkers and colleagues (2001) found that 35% of the 604 Latina mothers in their study had major depressive symptoms immediately after delivery. Based on a study of 3,952 postpartum Latinas, Kuo et al. (2004) suggested that the postnatal period can also represent a vulnerable time for new mothers. Kuo and colleagues found that 43 of the postpartum women in their study had probable cases for depression, as indicated by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Using the CES-D, Davila, McFall, and Cheng (2009) found that 21% of 439 prenatal and post-partum Latinas had moderate levels of depressive symptoms and 15% had more severe symptoms.

Significant risk factors for postpartum depression and a correspondingly elevated incidence of depressive symptoms are present in the Latina community (Lara, Le, Letechipia, & Hochhausen, 2009). Recent immigrants are especially likely to report symptoms of depression (Munet-Vilaró, Folkman, & Gregorich, 1999), as are Latinas who are under the age of 25, have less than a high school education, and have limited access to health care providers (Howell, Mora, Horowitz, & Leventhal, 2005). Women living in poverty are also known to be at high risk for depression; this is a serious concern for Latinas, who are overrepresented among the poor (Belle & Doucet, 2003; Nadeem, Lange, & Miranda, 2008).

Given the diversity of the Latino community in the United States, it is equally important to pay close attention to differences that might exist across Latino groups. Some of those group differences have been unraveled in recent studies (e.g., Davila et al., 2009). For example, Davila and colleagues found that U.S.-born Latinas are significantly more likely to report moderate to high rates of depressive symptoms compared to foreign-born Latinas. As Davila and colleagues stipulated, acculturation levels can also help to explain differences within Latinas, given that language acquisition and acculturative stress can have differential impacts on a woman’s well-being.

Despite the growing awareness of prenatal and post-partum depression, these conditions are not always readily recognized by the woman herself or diagnosed by her providers (Chaudron et al., 2005). One possible explanation might be barriers to detection such as language barriers, poor health literacy, and culturally different ways of describing symptoms. Latina women’s definitions of depression can also help explain low levels of detection. For example, somatic presentation of depression is common in the Latino community and results in patients reporting the physical sequelae of depression, rather than sadness or anhedonia; however, Latinas are most likely to recognize depression based on suicidal ideation or severe symptomology (Lewis-Fernández, Das, Alfonso, Weissman, & Olfson, 2005). Thus, a woman’s own explanation of her problem is a critical aspect of the detection of depression as well as for the development of a treatment plan (Karasz & Watkins, 2006).

Many women understand depression as a social rather than medical condition. They do not consider themselves to be ill, but instead understand their symptoms as a normal reaction to a high level of stress. Therefore, they are less likely to find the use of pharmacology acceptable (Karasz & Watkins, 2006; Lara-Cinisomo, Burke Beckjord, & Keyser, 2010). Perhaps for similar reasons, Latinos are less likely than non-Hispanic Whites to accept a physician’s diagnosis of depression (Cardemil, Kim, Pinedo, & Miller, 2005). Given the importance of correctly diagnosing depression, determining a common definition of depression, and addressing stereotypes or misconceptions about depression among Latinos, health care providers should recognize that focusing their attention on accomplishing these goals will enable them to identify and appropriately treat Latinas at risk of or suffering from depression.

Treatment Approaches

Prenatal and postpartum women tend to cope with depression by seeking social support from partners, friends, and family (Ahmed, Stewart, Teng, Wahoush, & Gagnon, 2008; Dennis, 2005). Research has also suggested that perinatal women access strategies that include participating in formal support networks (e.g., parent support groups), resuming activities outside of the home (e.g., work or school), and/or attempting to modify their attitudes and expectations of a given situation (Ahmed et al., 2008). Passive approaches, such as waiting for symptoms to pass, are other commonly endorsed strategies for coping (Cooper et al., 2003; Sleath et al., 2005).

Attitudes about depression treatments vary across racial, ethnic, and cultural groups (Givens, Houston, Van Voorhees, Ford, & Cooper, 2007; Lin et al., 2005; Sleath et al., 2005). For example, minorities are more likely to perceive that nonpharmacological therapies are effective and that antidepressants are addictive. These perceptions of treatment effectiveness might be because of variation in social and cultural perspectives (Givens et al., 2007; Karasz & Watkins, 2006; Lin et al.). Depression treatment preferences have been identified in high-risk women, including perinatal Latinas (Alvidrez & Azocar, 1999; Givens et al.; Nadeem et al., 2008; Sleath et al.); however, there are no data about the order in which women would approach their treatment preferences.

In a recent study of prenatal and postpartum women’s depression treatment decision-making processes, slightly more than half (53%) of the 100 perinatal women sampled preferred having an active role in the decision-making process regarding their depression treatment (Patel & Wisner, 2011), with a combination of counseling and medication ranking highest among treatment options. The sample included a small number of Latinas, which did not allow a determination of where they fall within the decision-making spectrum. There is evidence to suggest that Latina mothers prefer individual psychotherapy over the use of antidepressants (e.g., Sleath et al., 2005), but what other treatment approaches they would pursue before or after psychotherapy remains unknown. This article is intended to address this gap in the literature.

Barriers to Treatment Seeking

Approaches that Latina mothers recommend for addressing some common barriers to treatment among Latinos have also been understudied. Three types of barriers to mental health care among Latinos have been identified in previous research: structural, instrumental, and social. These three types of barriers have been shown to prevent or limit access to mental health care among Latinos as well as Latinas. Structural barriers refer to those at the health care or organizational level; these include provider unavailability or responsiveness, language barriers, and lack of information about services, particularly in Spanish (Ahmed et al., 2008; Alvidrez & Azocar, 1999; Anderson et al., 2006; Guarnaccia & Marinez, 2002; Lagomasino et al., 2005).

Instrumental barriers are most commonly related to limited or no mental health insurance coverage, few financial resources, and lack of transportation and child care (Ahmed et al., 2008; Alvidrez & Azocar, 1999; Anderson et al., 2006; Guarnaccia & Marinez, 2002; Kouyoumdjian, Zamboanga, & Hansen, 2003). Social barriers include (among others) stigma of mental illness, a preference for family and other informal support networks over formal care, lack of awareness and recognition of mental health problems, the perceived failure of previous treatment, concerns about efficacy and safety (regarding pharmaceutical treatment), self-reliant attitudes, and lack of trust (Ahmed et al.; Alvidrez & Azocar; Chaudron et al., 2005; Guarnaccia & Marinez; Kouyoumdjian et al., 2003; Lewis-Fernández et al., 2005). Some fears are unique to pregnant women and new mothers. Prominent among these are the fears that a mental health diagnosis or treatment will result in the loss of custody of their children (Anderson et al.).

Given the range of barriers Latina mothers might encounter while seeking help and treatment, whether they are seeking these things from friends or formal support systems, it is important to understand what Latinas believe behavioral health providers can do to treat their symptoms. In this article, we address three questions designed to identify treatment preferences for the highly unstudied population of perinatal Latinas: What are strategies used by perinatal Latinas to cope with depressive symptoms? What are acceptable depression treatments among Latina mothers at risk of depression? What are Latinas’ recommendations for addressing common barriers to treatment?

Methods

We chose focus groups as the most appropriate methodology because group discussions allow participants to share their perspectives without feeling targeted (Keim, Swanson, Cann, & Salinas, 1999; Morgan, 1993). Focus groups also allow for the emergence of a synergy of information that could not occur in one-on-one interviews or self-administered surveys (Keim et al., 1999).

Data Collection

Women were recruited using networks established by a faith-based research partner and a local Latina mothers’ support group designed to discuss issues related to stress during the perinatal period. Prior research with at-risk, low-income women has suggested that using the term stress is more culturally acceptable and less threatening than the term depression. Women were also recruited using trusted health care providers such as home-visiting nurses and a Spanish-speaking pediatrician. Providers were asked to identify perinatal women with a history of stress during the perinatal period who would feel comfortable meeting in a group with other perinatal women to answer the interview questions. A flyer describing the study and the focus on perinatal women experiencing stress was distributed to prospective participants after church services and in health facility waiting areas. Prospective participants were also approached by the first author, a Latina and native Spanish-speaker, after their providers described the project and the women consented to the introductions.

Eligible participants for our study were 18 years of age or older, self-identified as Latina, and were pregnant or had given birth within 24 months from the date of recruitment. The study was conducted in two cities located in southwestern Pennsylvania, a region in which Latino immigration is relatively new. The study was approved by the RAND Corporation Human Subjects Review Board as well as the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate in the study was secured prior to conducting the focus group interviews. Each focus group took approximately 90 minutes to complete. Focus group discussions were audiotaped with the participants’ consent. Spanish, English, and bilingual (Spanish and English) focus groups were conducted based on participant preference. One prenatal and two postpartum focus groups were formed. The prenatal group was conducted in English. One postpartum group opted to be interviewed in Spanish and the other participated in both Spanish and English. Eight prenatal women and 14 post-partum mothers participated in the study. Focus groups were facilitated by the first author, who has extensive experience facilitating Spanish, English, and bilingual focus groups. Interviews were conducted in a private conference room located in the first author’s offices and in a community room used by health care professionals for group education and other patient meetings. Participants were given a modest gift in appreciation of their participation.

Participants

Twenty-two prenatal and postpartum Latina mothers participated in the study. The mean age was 24.12 years (SD = 4.46). The vast majority of participants (64%) were postpartum. The mean child age was 11.57 months (SD = 5.73). Thirty-six percent of participants were pregnant and in the second or third trimester. Given that concerns about immigration status were raised during recruitment, we limited our questions to country of origin. Three Latino ethnicities were represented in the sample: Puerto Rican (59%), Dominican (23%), and Mexican (9%); 9% of respondents self-identified as Other.

All participants spoke Spanish but only 9% chose to be interviewed in Spanish; 36% opted to speak English; and 55% preferred both English and Spanish. More than half (55%) were married or living with their partner. Thirty-two percent had less than a high school education; 46% had a high school education; 9% had some college; 4% had a bachelor’s degree; and 9% did not report their highest level of education. All participants were eligible for Medicaid, a federal health insurance program available to low-income individuals, including pregnant women and Medicaid-eligible mothers.

Interview Topics

The aim of the focus groups was to determine treatment preferences and barriers to treatment among a sample of perinatal Latinas at risk for depression. Being at risk for perinatal depression includes the presence of risk factors identified in the cited literature, including a history of depression or distress during the perinatal period and psychosocial risk factors for postpartum depression (e.g., poverty, acculturative stress, limited access to quality health care, and social isolation). Four primary areas of inquiry guided the focus group discussions. The topics were developed on the basis of prior research with low-income perinatal women (Lara-Cinisomo et al., 2010) as well as the cited literature. The interview questions were piloted with two perinatal Latinas who resided in the target region.

The first area of inquiry included defining both depression and postpartum depression to ensure that a common definition of depression would be used among all participants. To arrive at a common definition, we asked the women what depression meant to them, how they defined depression, and how it was similar and/or different for pregnant and postpartum women. This set of questions allowed us to use terms that reflected these women’s conceptual frameworks and to use definitions that were meaningful to them. The second area of inquiry was focused on treatment preferences, particularly treatment approaches and options the women believed to be appropriate for prenatal and postpartum women at risk for or suffering from depression. This area of inquiry also allowed us to identify treatment options and interventions that would meet participants’ cultural and linguistic needs.

The third area of inquiry, barriers to treatment, was focused on factors that might prevent health providers and researchers from treating prenatal and postpartum Latinas. Consequently, we inquired about potential barriers to treatment, including cultural barriers and beliefs about the costs and benefits of various treatments. The fourth and final area of inquiry included the solicitation of suggestions for treatment delivery, so that recommendations could be gathered to address barriers mentioned during the focus group interviews. The demographic information mentioned above was collected using an anonymous survey administered after each focus group interview.

Data Analysis

The first author conducted all of the discussions. The unit of analysis was the focus group transcript. The Spanish interviews were transcribed by a native Spanish speaker who is also a professional translator. The transcriber/translator provided side-by-side translations that two Latino, native Spanish speakers on the research team (first and fourth authors) reviewed and confirmed. To reduce potential researcher bias on the part of the native Spanish speakers on the team, a native English-speaking research assistant also participated in discussions about the translations and how data analysis would be conducted; these discussions constituted the first step of the data analysis process (Temple & Young, 2004). On confirmation of the translation, coding of the data was initiated.

Using procedures recommended by Miles and Huberman (1984), the first author, third, and fourth authors individually read each transcript using the four areas of inquiry described above to guide their reading for themes (Miles & Huberman). Next, the three coders each identified salient themes in the data that were relevant to the four areas of inquiry described above. In addition to coding for specific themes, the coders identified sub-themes as they separately reread each set of transcripts. For example, while exploring the text for information regarding barriers, it became clear that trust was an important subtheme that functioned as a barrier if it had not been established.

The coders then met to discuss their respective codes and discrepancies and to reach consensus. For example, when coding for coping strategies, each coder identified themes that emerged from the data and created representative labels for each theme. During the team discussions, each coder presented his or her labels and illustrated the definition of those labels using quotes from the transcripts. Next, the coding team discussed the labels and reached a consensus on which labels to use to code all of the transcripts. This process was carried out for each area of inquiry that had been designed to answer the three research questions. Following this phase of the data analysis, study participants were invited to a data feedback session in which their impressions of the identified patterns were solicited by the coding team; the coding scheme was affirmed by the input of participants who attended this meeting.

Results

Coping Strategies

To identify coping strategies among a sample of at-risk perinatal Latinas, the first research question addressed was, What coping strategies are used by perinatal Latinas to cope with depressive symptoms? Three primary approaches to coping with depression emerged from the data: planful problem-focused, cognitive coping, and emotional disengagement. Planful problem solving refers to a deliberate strategy used to address a stressful event (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986). In this instance, participants reported strategically seeking social support from trusted individuals such as family, friends, or a health care professional (e.g., a nurse or obstetrician) with whom they had an ongoing patient–provider relationship. Two participants described their primary care provider as a friend: “My primary … she’s my OBG [obstetrics and gynecology provider] … she’s almost everything [to me].” Another woman said, “I like her. I talk to her [because she has] an open door. She’s like a friend.”

Cognitive coping, or focusing on an activity or specific thoughts for a period of time, also emerged as a way of coping with depressive symptoms. Unlike problem avoidance, cognitive coping allows the woman to put her thoughts and energy into something constructive. Examples included focusing on the baby’s physical growth, thinking positive thoughts about the child, planning for the child, and knitting clothing for the child. Emotional disengagement, by contrast, was an intentional isolation or withdrawal from others. This strategy was reportedly implemented when symptoms were heightened because of an external stressor, such as during periods of economic strain or demanding family obligations. One prenatal mother stated,

[I tell my children], “I don’t want to be bothered. Please don’t bother me. I don’t want to be bothered.” I go straight to my room and they’ll be like, “Mommy, are you okay? Mommy, are you sure we are bothering you? Mommy, can we lay down here?” And I say, “Baby, go over there. When it goes away, I’ll go downstairs and I’ll sit with you.”

Treatment Preferences

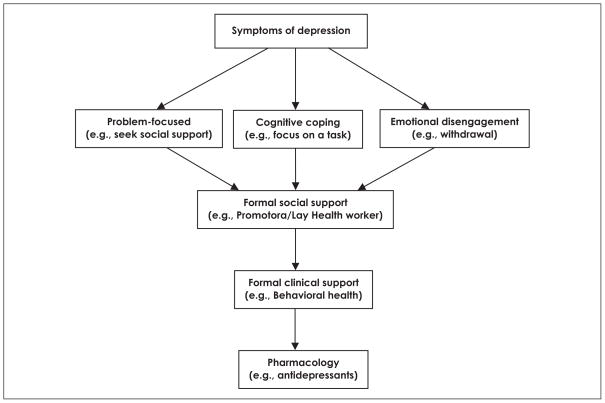

The second aim of our study was to determine treatment approaches that study participants thought would be appropriate for treating prenatal and/or postpartum depression. Results revealed that participants saw a woman’s own coping strategies as the first line of defense. Our analysis also revealed a hierarchy of treatment preferences (e.g., a pathway to treatment for depression; see Figure 1). Following use of their own coping strategies, women in our study reported that a second-level, or tiered approach would include the use of formal support by a home-visiting nurse or lay community health worker (referred to as promotora in Spanish-speaking and Latino communities). The women specified, however, that a home visitor/promotora should be introduced by a trusted health care professional or friend.

Figure 1.

Illustration of perinatal Latinas’ mental health treatment preferences that emerged from focus group discussions.

Participants who received a home-visiting nurse during their pregnancy reported having a positive experience and said that they would welcome the opportunity to meet with someone in their home, especially because they could talk to the provider in private without having to leave home. This possibility was especially appealing to women who were uneasy meeting new providers. One mother stated,

It’s a good idea [to have a home visitor]. In my case, I would like it because I am a person who is not sure of herself, and I like to talk to a person alone, and then I am able to relax.

A promotora’s visit was also appealing to women who were worried about their immigration status. Women talked about fears of being detained by authorities when visiting what they termed “official” or federal buildings for services.

Behavioral treatment, the fourth identified approach to coping with depression, was among the least preferred treatment options, primarily because women worried about possible threats when seeking professional mental health care services. One mother described this fear:

Once I had like a nervous breakdown. I got shaky and said that I wanted to talk to a professional because it could affect my baby, do you understand? [People] frighten you with, “Oh, they’re going to take your baby away,” or they try to make you feel like you’re crazy. You understand me? At times you want to talk and maybe you can talk to a professional, but you think, “They are going to take my baby away. They are going to say that I’m crazy.” You understand what I am saying? You at times want to talk, but sometimes you say, “No,” it is best for you to talk to a friend, or somebody who is not a professional, and who will provide you with the same support, or even go further and help you even more.

Participants also worried about feeling pressured to take antidepressant medication and were concerned about being judged or having “opinion[s]” imposed upon them. One woman said, “The psychologist, they have an opinionated mind. They will give you opinions that you don’t want to hear about.” Although the women noted that a behavioral health professional might be the best treatment option in severe cases, a trusted and known individual (e.g., a friend or known health care provider) was given preference.

As Figure 1 shows, the last resort for treating depression for this sample would be the use of antidepressants. Participants noted that antidepressants would be appropriate in severe cases during pregnancy or after breast-feeding has ceased. In fact, one postpartum participant disclosed that she sought help from a mental health specialist because her own efforts were fruitless. This participant noted that the antidepressant pills she was taking made it possible for her to care for her infant. Despite this testimony, however, most participants worried about potential side effects, such as feeling lethargic, and potential negative effects on the fetus or breastfeeding infant.

Addressing Barriers to Treatment Engagement

The third research question involved participants’ recommendations for addressing barriers to treatment among perinatal Latinas. According to our analysis of the data, regardless of focus group type (prenatal vs. postpartum, Spanish vs. English), a lack of trust is the primary barrier to seeking formal mental health services. Women repeatedly emphasized the importance of relying on individuals whom they trust. Logistical issues (e.g., child care) were not reported as a barrier to seeking formal care; instead, the women expressed concern about seeking services from individuals and facilities that could threaten their stability (e.g., by taking their child or having them deported).

When asked how those barriers could be addressed, the women responded that health care professionals should provide referrals to behavioral health professionals whom other women have seen and with whom those women have developed trusting relationships. The women also said they would seek behavioral and medical care from professionals if a friend or family member provided the referral (i.e., referrals are best received when provided by trusted health care providers, friends, or family). In addition, according to the data, the use of personal contacts or testimonies from community members to engage patients can help to address a lack of trust and misconceptions about proposed interventions and treatments. For example, the women noted that they would be more likely to seek a specific type of service or would agree to participate in an intervention if a friend or family member had prior experience with that service or program.

The location of the intervention also mattered. For example, a home-visiting nurse or program located in a safe place was more appealing to women who worried about their immigration status than services offered at unfamiliar facilities, especially facilities that have an official appearance. A home-visiting program was also appealing to women who wished to have privacy or were unable to travel to a clinic or hospital. However, as previously mentioned, the home visitor should be introduced by a trusted health care provider or friend/family member. Women who were comfortable and able to seek formal mental health care services away from the home specified that the professional should avoid imposing his or her personal views or appearing to pressure them to use antidepressants.

Discussion

Our findings reveal a treatment pathway that highlights the important role family and friends play in helping pre-natal and postpartum Latinas cope with depressive symptoms. This pathway also acknowledges that although trusted health care professionals can be seen as a source of support, behavioral health professionals are not necessarily viewed favorably; nor are they cited as a trusted option for treating depression. This sentiment, which held true both for Spanish- and English-speaking participants, supports previous reports that have cited lack of trust as a primary factor in the low levels of mental health participation among Latinos and other low-income minorities (Anderson et al., 2006).

Our findings also support previous results that have shown the importance of trusted formal support systems, such as the use of promotoras, in addressing and treating health issues among the Latino population, including depression (Lujan, Ostwald, & Ortiz, 2007; Wasserman, Bender, & Lee, 2007). Researchers have also found that effective programs with Latinas have not only included promotoras but also were especially well received and successful in addressing health disparities (Lujan et al.; Wasserman et al.). Researchers have attributed the success of such programs to the emotional aid and institutional support they provide. This conclusion echoes the value participants in our study placed on relationships they perceived as being the most supportive and effective when treating depression. Another promising use of pro-motoras has included partnerships with researchers; such partnerships have been shown to benefit research teams as well as targeted communities because the two systems bring together community insight and content expertise (Lujan et al.; Wasserman et al.).

In summary, perceptions of depression and preferences for treating depression were highlighted among the sample of prenatal and postpartum Latinas in our study. Specifically, health care professionals who are offering prenatal and postpartum depression treatment should take into account the need for trust when engaging Latinas. To do this, providers should access women via a network of providers or community members that the target community trusts, and/or practitioners should implement culturally sensitive practices. Evidence in the literature suggests that the use of culturally competent or culturally appropriate practices, such as tapping into the Latino value of comadrismo (trust and mutual respect, in this case among women), increases engagement in research; the same can be said about engaging Latinas in health care practices (Preloran, Browner, & Lieber, 2001). Evidence also suggests that knowing where to go for help increases the odds of using a mental health specialist among Mexican American Latinos (Vega, Kolody, & Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2001).

Latinas’ preferences for treatment (e.g., relying on social networks), however, should also be noted and respected when promoting specific treatment approaches such as behavioral health. Treatment preferences should also be considered, given that this population’s perceptions about effective treatment approaches and preferred options might be driven by fears and misconceptions about the risks and consequences associated with various treatment options. Therefore, health care providers should explore the Latina patient’s beliefs about depression and tailor the discussion to the treatment(s) she prefers. In addition, health care providers should present alternative therapies should the preferred or initial treatment be ineffective. Practitioners should also focus on informing mothers about the potential benefits of various treatments (e.g., psychotherapy, pharmacology). For example, whereas the participants described in this article clearly preferred alternatives to mental health professionals and pharmacological interventions, certain cases of depression during the prenatal and postpartum period might necessitate the use of professionals and pharmacological interventions for the safety of both mother and child. Finally, given the potential fear mothers might experience if they seek mental health support, practitioners might want to inform mothers about the circumstances in which a child might be removed, to inform the mother what symptoms constitute a major concern while providing a supportive environment in which the mother can openly describe her mood and needs.

Because treatment preferences and attitudes play important roles in compliance and satisfaction, which in turn can influence outcomes, researchers and health care providers must better understand the treatment preferences of individuals from diverse cultural groups, such as prenatal and postpartum Latinas (Lagomasino et al., 2005). Furthermore, information about different treatment options should be made available to perinatal Latinas, given their high reliance on the reputations and opinions of those around them. Perinatal Latinas have specific fears and concerns about the use of behavioral health and/or pharmacology to treat depression. In fact, these concerns were emphasized in the focus groups even though one postpartum woman noted the effectiveness of antidepressants in treating her depression. Therefore, education about the benefits of those therapeutic approaches should be offered in a culturally sensitive manner that takes into account fears about addiction and side effects to mother and child.

Given the perceived benefits of using personal networks to cope with depression, and the clear preference of our study population for the use of such networks, significant others, immediate and extended family, and friends should be informed about depression symptoms and ways to support a mother suffering with depression. Those supportive individuals can also become partners in the treatment process should the woman consent to their engagement and involvement. The woman should also have the option to alter the role and function of such networks as her treatment evolves.

Limitations

With regard to focus group design, because of the small sample size the generalizability of focus group data from this study is limited and thus not representative of the overall population. However, given the nature of qualitative research, a sample of 22 women is sizable considering the sensitive nature of the issues being addressed and the descriptive nature of this article. Although participants’ responses might not be representative of Latina prenatal and postpartum women, given that both Spanish- and English-speaking Latinas participated, we believe that perspectives from a range of participants were captured. Still, the qualitative nature of most of the data inevitably limits its representativeness. It would have been ideal to compare the focus groups with other ethnic and racial groups, and with nonimmi-grant groups. This approach would have allowed us to compare results of conceptualizations of depression as well as treatment preferences by race/ethnicity and immigration status.

A final consideration is the lack of depression history among the study participants. Nonetheless, we were interested in learning about treatment preferences among prenatal and postpartum Latinas and were able to do so. Despite the fact that we did not collect participants’ depression histories, some reported having depression or having been depressed, and all women were recruited because they either had experienced or were experiencing stress during the perinatal period. Given that one of our study goals was to provide new insights into the issues under investigation that will enable us to design follow-up interventions that meet the cultural needs of the population in our study, we believe the data achieved this.

Conclusions

Despite cultural preferences, it is important for educational programs to raise awareness of the importance of the role of mental health professionals as well as the alternative of consulting such professionals and the safety and efficacy that pharmacological treatments might confer. Health care providers should also take great care when describing postpartum depression symptoms, to ensure that definitions and terminology reflect the perceptions of this target population. In addition, interventions should include an educational component to help women become informed about the benefits and risks associated with each treatment option. For example, participants reported that they would consider pharmacological interventions in severe cases or after breastfeeding has been discontinued. This perception provides a clear example of the potential benefit of education about pharmacological alternatives, as infant exposure to antidepressants through breastfeeding is very low when using approved drugs; still, their use must be balanced against the substantial risks of depression to the mother and child (Wisner et al., 2009). Finally, engagement of Latinas should include a treatment model that reflects their preferences and comfort levels, including key issues such as trust.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Kristyn Felman for her assistance with the literature search. We also thank the clinics and staff for their assistance in recruiting participants. We gratefully acknowledge the study participants for their time, candor, and courage.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support was received from the RAND–University of Pittsburgh Health Institute and the Magee Women’s Research Institute. Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo’s perinatal mood disorders research was supported by the National Institute of Health (MH093315, “Postdoctoral Training in Reproductive Mood Disorders”; Drs. Girdler and Rubinow, principal investigators).

Biographies

Sandraluz Lara-Cinisomo, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill School of Medicine, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Katherine L. Wisner, MD, MPH, is an Asher Professor and director of the Asher Center for Research and Treatment of Depression in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, in Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Rachel M. Burns, MA, is a project associate at the RAND Corporation in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Diego Chaves-Gnecco, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, of UPMC, University of Pittsburgh, and program director and founder, Salud Para Niños, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with regard to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was supported by an unrestricted grant from the RAND–University of Pittsburgh Health Institute for this project. Katherine Wisner served on an advisory board for Eli Lilly Company and received a donation of estradiol and matching placebo transdermal patches from Novartis for a National Institute of Mental Health-funded randomized trial.

References

- Ahmed A, Stewart DE, Teng L, Wahoush O, Gagnon AJ. Experiences of immigrant new mothers with symptoms of depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Azocar F. Distressed women’s clinic patients: Preferences for mental health treatments and perceived obstacles. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1999;21:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Robins CS, Greeno CG, Cahalane H, Copeland VC, Andrews RM. Why lower income mothers do not engage with the formal mental health care system: Perceived barriers to care. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:926–943. doi: 10.1177/1049732306289224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory manual. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Belle D, Doucet J. Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among US women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Kim S, Pinedo TM, Miller IW. Developing a culturally appropriate depression prevention program: The family coping skills program. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:99–112. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Kitzman HJ, Peifer KL, Morrow S, Perez LM, Newman MC. Self-recognition of and provider response to maternal depressive symptoms in low-income Hispanic women. Journal of Women’s Health. 2005;14:331–338. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzalez JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Ford DE. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41:479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila M, McFall SL, Cheng D. Acculturation and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2009;13:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: Systematic review. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:15–18. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7507.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;50:992–1003. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr K, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, Miller WC. Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No 119. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Retrieved from http://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/peridepsum.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: A review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2003;6:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnaccia PJ, Marinez I. Comprehensive in-depth literature review and analysis of Hispanic mental health issues. New Jersey: Mental Health Institute, Inc; 2002. Retrieved from www.njmhi.org/litreviewpdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, Leventhal H. Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;105:1442–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000164050.34126.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasz A, Watkins L. Conceptual models of treatment in depressed Hispanic patients. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4:527–533. doi: 10.1370/afm.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim KS, Swanson MA, Cann SE, Salinas A. Focus group methodology: Adapting the process for low-income adults and children of Hispanic and Caucasian ethnicity. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 1999;27:451–465. doi: 10.1177/1077727X99274005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kouyoumdjian H, Zamboanga BL, Hansen DJ. Barriers to community mental health services for Latinos: Treatment considerations. Clinical Psychology. 2003;10:394–422. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpg041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH, Wilson TE, Holman S, Fuentes-Afflick E, O’Sullivan MJ, Minkoff H. Depressive symptoms in the immediate postpartum period among Hispanic women in three U.S. cities. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2004;6:145–153. doi: 10.1023/B:JOIH.0000045252.10412.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagomasino IT, Dwight-Johnson M, Miranda J, Zhang L, Liao D, Duan N, Wells KB. Disparities in depression treatment for Latinos and site of care. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:1517–1523. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara MA, Le HN, Letechipia G, Hochhausen L. Prenatal depression in Latinas in the U.S. and Mexico. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2009;13:567–576. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cinisomo S, Burke Beckjord E, Keyser DJ. Mothers’ perspectives on enhancing consumer engagement in behavioral health treatment for maternal depression. In: Kronenfeld JJ, editor. Research in the sociology of health care: Vol. 28. The impact of demographics on health and health care: Race, ethnicity and other social factors. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group; 2010. pp. 249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R, Das AK, Alfonso C, Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in US Hispanics: Diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18:282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P, Campbell DG, Chaney EF, Liu CF, Heagerty P, Felker BL, Hedrick SC. The influence of patient preference on depression treatment in primary care. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:164–173. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan J, Ostwald SK, Ortiz M. Promotora diabetes intervention for Mexican Americans. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33:660–670. doi: 10.1177/0145721707304080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: A source book of new methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Munet-Vilaró F, Folkman S, Gregorich S. Depressive symptomatology in three Latino groups. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21:209–224. doi: 10.1177/01939459922043848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2008;11:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Wisner KL. Decision making for depression treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Depression & Anxiety. 2011;28:589–595. doi: 10.1002/da.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preloran HM, Browner CH, Lieber E. Strategies for motivating Latino couples’ participation in qualitative health research and their effects on sample construction. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1832–1841. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B, West S, Tudor G, Perreira K, King V, Morrissey J. Ethnicity and depression treatment preferences of pregnant women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2005;26:135–140. doi: 10.1080/01443610400023130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple B, Young A. Qualitative research and translation dilemmas. Qualitative Research. 2004;4:161–178. doi: 10.1177/1468794104044430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Help seeking for mental health problems among Mexican Americans. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3:133–140. doi: 10.1023/A:1011385004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman M, Bender D, Lee SD. Use of preventive maternal and child health services by Latina women: A review of published intervention studies. Medical Care Research & Review. 2007;64:4–45. doi: 10.1177/1077558706296238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Sit DKY, Hanusa BH, Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen DL, Hunker DF, Bodnar LM. Major depression and antidepressant treatment: Impact on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:557–566. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Ramin SM, Rush AJ, Navarrete CA, Carmody T, March D, Leveno KJ. Onset and persistence of post-partum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1856–1863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Jankowski KRB, McKee DM. Prenatal and postpartum depression among low-income Dominican and Puerto Rican women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:370–385. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]