Abstract

Background

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy is one of the most preventable causes of infant morbidity and mortality, yet 80% of women who smoked prior to pregnancy continue to smoke during pregnancy. Past studies have found that lower maternal-fetal attachment predicts smoking status in pregnancy, yet past research has not examined whether maternal-fetal attachment predicts patterns or quantity of smoking among pregnant smokers. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between maternal-fetal attachment and patterns of maternal smoking among pregnant smokers. We used self-reported and biochemical markers of cigarette smoking in order to better understand how maternal-fetal attachment relates to the degree of fetal exposure to nicotine.

Methods

Fifty-eight pregnant smokers participated in the current study. Women completed the Maternal-Fetal Attachment scale, reported weekly smoking behaviors throughout pregnancy using the Timeline Follow Back interview, and provided a saliva sample at 30 and 35 weeks gestation and 1 day postpartum to measure salivary cotinine concentrations.

Results

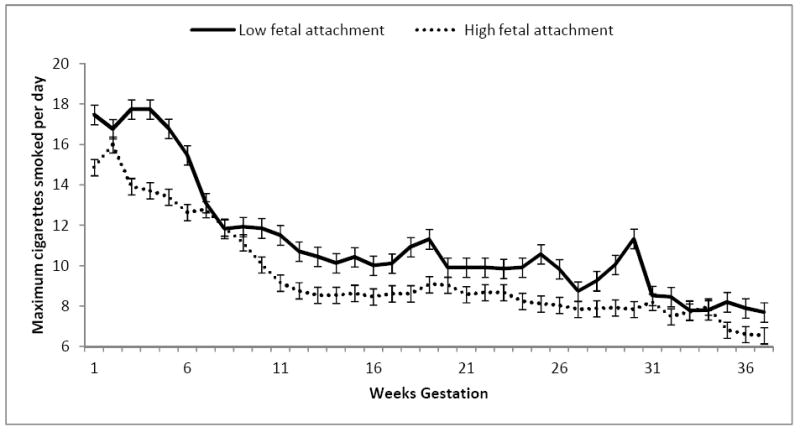

Lower maternal-fetal attachment scores were associated with higher salivary cotinine at 30 weeks gestation and 1 day postpartum. As well, women who reported lower fetal attachment reported smoking a greater maximum number of cigarettes per day, on average, over pregnancy.

Conclusion

Lower maternal-fetal attachment is associated with greater smoking in pregnancy. Future research might explore whether successful smoking cessation programs improve maternal assessments of attachment to their infants.

Keywords: Cigarette, smoking, attachment, cotinine, pregnancy

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy is one of the most preventable causes of infant morbidity and mortality (1). Continuation of smoking during pregnancy is related to increased maternal risk for spontaneous abortion and complicated birth (2), placenta previa (3), and peripartum mood disorders (4). Fetal and infant effects of nicotine exposure range from mild to severe, including infant irritability (5), increased risk of preterm birth and low birth weight (6), genetic deformities (3), and sudden infant death syndrome (7). Maternal smoking is also associated with decreased initiation and /or continuation of breastfeeding (8,9).

Despite these risks, a staggering 80% of US women who smoke prior to conception will continue to smoke throughout pregnancy (10). Thus, over 500,000 fetuses are directly exposed to tobacco per year in the US (10). More research is needed that examines factors to help motivate women to quit smoking, and remain abstinent from tobacco, during pregnancy. Investigators have proposed that strong maternal-fetal attachment may serve as a key factor in promoting healthy behaviors in pregnancy (11, 12).

According to Cranley (13), maternal-fetal attachment is “the extent to which women engage in behaviors that represent an affiliation and interaction with their unborn child.” A small number of past studies have found that lower maternal-fetal attachment scores are related to poorer health practices during pregnancy. In particular, past studies have found that women who report feeling less attached to their fetus are more likely to smoke cigarettes in pregnancy (11, 12). However, these studies have not examined whether maternal-fetal attachment is related to the amount of cigarette smoking during pregnancy among pregnant smokers. This gap in the literature is significant given that greater cigarette consumption is associated with poorer neonatal outcomes (14) and greater difficulty quitting smoking (15).

To address this gap in the literature, the current study was designed to assess the relationship between maternal-fetal attachment and patterns of maternal smoking throughout pregnancy among smokers. We examined both patterns and quantity of smoking over pregnancy using measures of self-reported weekly cigarette smoking and a biochemical marker of nicotine (e.g., salivary cotinine). We hypothesized that women who report lower maternal-fetal attachment would smoke significantly more cigarettes throughout gestation compared to women who report higher maternal-fetal attachment.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-eight pregnant smokers were included in the current analyses (Mage=25, SD=5). Participants in this study were part of a larger study on the effects of maternal smoking on fetal and infant development (Behavior and Mood in Babies and Mothers (BAM BAM)). Women were classified as ‘smokers’ if they reported smoking throughout pregnancy and/or had salivary cotinine values > 10 ng/mL at study sessions. Women were excluded from participating in the larger study if they reported more than one alcoholic drink per week throughout pregnancy, were over 40 years old, were pregnant with more than one fetus, or were at high risk for adverse neonatal outcomes. Women who reported quitting smoking during pregnancy (defined as smoking no cigarettes/week and sustaining until the end of pregnancy, biochemically verified with cotinine concentrations) were excluded from the current analyses.

Women in the current study were primarily low income from diverse racial and ethnic background (average annual income < $20K/year; 77% unemployed; 22% Black, 19% Hispanic, 53% White, 5% Asian, 5% Native American, 9% “other”, 5% >1 race). The majority of pregnancies (83%) were unplanned, and 35% of women reported that they were not married or in a committed relationship during their pregnancy. The mean maternal-fetal attachment score in this sample was 97.3 (SD=11.6, range: 69.7-118.1). The average number of cigarettes smoked per day over pregnancy was 9 (SD=7, range: 0-40), and the maximum number of cigarettes smoked, on average, per day over pregnancy was 18 (SD=11, range: 0-50).

Babies in this sample were, on average, born at 39 weeks gestation (SD=2, range: 34-42) and were an average weight of 3097 grams (SD=471, range: 1830-4280). Five percent of births were low birth weight (<2500grams), 11% were preterm (<37 weeks gestation at birth), and 6% were small for gestational age (SGA; <10th percentile in weight based on gestational age at birth).

Measures

Procedure

Women were an average of 30 weeks gestation (SD=2 weeks) at the time of study enrollment. They were interviewed again in third trimester (M=35 weeks gestation, SD=1 week) and following delivery (M=1 day postpartum, SD=1 day). Interviews were conducted in private assessment rooms within the Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine within Lifespan Hospital by trained interviewers. At the initial interview, participants provided demographic and pregnancy-specific health information. Participants completed the Maternal-Fetal Attachment Scale (13) at 30 and 35 weeks gestation. At each session, participants completed the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) interview and provided saliva samples in order to measure cotinine. Following delivery, neonatal outcomes were determined by medical chart review. Birth weight percentile (birth weight based on gestational age at delivery) was calculated using the Fenton Growth Charts (16).

All study protocols were reviewed by the Lifespan and Women & Infants Institutional Review Boards. These review boards are comprised of hospital-based multidisciplinary representatives who hold expertise in research ethics. Pregnant women signed informed consent forms prior to participating.

Maternal Fetal Attachment

To measure participants’ emotional connection to their fetus, women completed the Maternal-Fetal Attachment Scale (13). This self-report measure includes 24 items indicating a woman’s emotional connection to her fetus. Women were asked to rate how much they thought about or engaged in behaviors such as “I talked to my unborn baby,” and “I imagined myself taking care of the baby.” Response options ranged from 1 to 5, with 1= “definitely no” and 5= “definitely yes.” Higher scores indicate more feelings of attachment. The scale has previously demonstrated good reliability (13).

Maternal Cigarette Smoking

Salivary Cotinine

At 30 and 35 weeks gestation and 1 day postpartum, participants provided a saliva sample (passive drool) in order to measure salivary cotinine. Cotinine is the principal nicotine metabolite produced by the liver and has a half-life of greater than 10 hours (17). After collection, saliva samples were frozen at -80 degrees Celsius and shipped to Salimetrics (State College, PA) for biochemical analysis using Enzyme-Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) kits, with a sensitivity of 0.15 mg/mL (18).

Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) Interview

Participants reported their cigarette use during each week of pregnancy using the TLFB interview (19). This semi-structured interview utilizes a calendar to aid in participants’ recall of smoking throughout pregnancy. The TLFB method is the preferred approach to measure substance use (20) and has shown reliability when used for pregnant women in previous studies (21). Based on participants’ reports, we calculated the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, and the maximum cigarettes smoked per day over pregnancy.

Data Analysis

Very little change was noted in maternal-fetal attachment scores between 30 and 35 weeks gestation (mean change = 2 points out of 120 possible points); scores were therefore averaged to create a summary attachment score. To examine the associations between maternal-fetal attachment and salivary cotinine at 30 weeks gestation, 35 weeks gestation, and 1 day postpartum we ran Spearman’s correlation analyses. Cotinine values were log transformed to adjust for skewed distributions. Maternal-fetal attachment scores were normally distributed and therefore were not log transformed. Next, we categorized participants into ‘low’ versus ‘high’ attachment groups by performing a median split of continuous maternal-fetal attachment scores. Then we compared self-reported weekly cigarette smoking (until full-term, 37 weeks) in low versus high attachment groups by performing repeated-measure analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for self-reported smoking in the three months prior to conception and nicotine dependence (15).

Results

Maternal Demographics by maternal-fetal attachment group

Prior to testing our study hypotheses, we assessed whether women with low versus high maternal-fetal attachment scores differed on maternal demographic variables or neonatal outcomes. Groups did not significantly differ on maternal age, race, marital status, income, employment status, gravida, parity, planned pregnancy, whether they considered adoption or abortion, breastfeeding, alcohol use in pregnancy, secondhand smoke exposure, living with a smoker, nicotine dependence, or depressive or anxiety symptoms. Babies born from mothers who reported lower maternal-fetal attachment were lower birth weight and were marginally more likely to be suspected to be growth restricted in utero. Gestational age at birth and SGA did not differ by maternal-fetal attachment group. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal Demographics by Maternal-Fetal Attachment Group among Pregnant Smokers

| Maternal-Fetal Attachment Group | Low (n=28) |

High (n=30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p | |

| Maternal-Fetal Attachment score | 87.83 (8.95) | 106.15 (4.47) | <.001 |

| Maternal age (years) | 25 (5) | 26 (4) | .21 |

| Race (% Non-Hispanic White) | 64% | 40% | .26 |

| Marital Status (% married) | 7% | 21% | .36 |

| Yearly Income | $20-30K ($10K) | $10-20K ($10K) | .52 |

| Employment status (% not working) | 75% | 77% | .88 |

| Gravida (median, range) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | .23 |

| Parity (median, range) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | .30 |

| Planned pregnancy (% no) | 82% | 83% | .91 |

| Consider adoption/abortion (% yes) | 32% | 23% | .45 |

| Breastfeeding (% yes) | 18% | 23% | .61 |

| Alcoholic drinks over pregnancy | 43 (136) | 21 (42) | .41 |

| Depressive symptoms (IDS)1 | 4.44 (3.74) | 5.21 (5.23) | .53 |

| Anxiety symptoms (HAM-A)2 | 4.29 (3.74) | 5.53 (4.65) | .26 |

| Live with another smoker (% yes) | 63% | 72% | .49 |

| Secondhand smoke exposure (hours) | 22 (24) | 25 (34) | .72 |

| Nicotine dependence score (Fagerstrom) | 3.24 (2.18) | 3.17 (2.02) | .91 |

| Infant Gestational Age (weeks) | 39 (2) | 39 (2) | .28 |

| Infant Birth Weight Percentile | 30. (23) | 42 (20) | .05 |

| Small for Gestational Age3 (% yes) | 8% | 7% | .97 |

Scores > 36 indicate severe depressive symptoms.

Scores > 24 indicate severe anxiety symptoms.

Small for gestational age = birth weight below the 10th percentile for the corresponding gestational age

Associations between maternal-fetal attachment and salivary cotinine

We then examined whether maternal salivary cotinine levels at 30 weeks gestation, 35 weeks gestation, or 1 day postpartum differed according to maternal-fetal attachment. We found a negative association between maternal-fetal attachment and salivary cotinine at 30 weeks GA and 1 day after delivery, such that lower reported maternal-fetal attachment was associated with higher salivary cotinine at 30 weeks gestation (ρ =-.28, p=.05) and 1 day after delivery (ρ =-.32, p=.02). The association between attachment and cotinine at 35 weeks gestation was in the same direction, but smaller in magnitude and not statistically significant (ρ=-.17, p=.27).

Maternal-fetal attachment and patterns of smoking over pregnancy

To determine whether maternal smoking patterns over pregnancy differed according to maternal-fetal attachment, we performed repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) of weekly smoking over pregnancy, controlling for pre-pregnancy smoking. We examined two indexes of smoking behaviors: average cigarettes smoked per day and maximum number smoked per day. Analyses revealed that, while patterns of average cigarettes smoked per day over pregnancy did not differ by fetal attachment group (F(1,44)=2.23, p=.14), there was a difference in the maximum number of cigarettes smoked per day, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (F(1,48)=3.83, p=.06). Women who reported lower fetal attachment reported smoking a greater maximum number of cigarettes per day compared to women who reported higher fetal attachment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Maternal smoking over pregnancy by maternal-fetal attachment group.

Discussion

Findings from our study show that, among pregnant women who smoke, those who report lower feelings of attachment to their fetus have higher salivary cotinine levels in pregnancy and postpartum with a trend toward smoking more cigarettes per day over pregnancy and postpartum. These findings are consistent with results from the small number of previous studies reporting that women with lower maternal-fetal attachment are more likely to smoke cigarettes in pregnancy (11, 12). However, our study delineates more clearly the relationship between attachment and smoking, as we were able to demonstrate that lower feelings of maternal-fetal attachment are associated with a greater quantity of cigarette use among women smoke during pregnancy. This is particularly important given that greater cigarette smoking in pregnancy has been linked to more detrimental neonatal outcomes (14). These findings suggest that maternal-fetal attachment may be an important target for smoking cessation programs for pregnant women.

Consistent with this hypothesis, Slade and colleagues (22) found that pregnant smokers with higher maternal-fetal attachment were more likely to be in the “preparation” stage (within the transtheoretical model of change) than women with lower maternal-fetal attachment. It follows that women with higher feelings of fetal affiliation may be more prepared and motivated to engage in smoking cessation programs.

Results from our study show that women with lower maternal-fetal attachment smoke a greater maximum number of cigarettes per day, on average, over pregnancy compared to women with higher maternal-fetal attachment scores; however, we did not find a difference in the average number of cigarettes smoked per day. It may be that women with lower feelings of attachment are less able to regulate their smoking behaviors due to a lack of intrinsic motivation to resist smoking for the health of their baby. While women with higher feelings of attachment may be able to smoke one cigarette, for example, to satisfy cravings, women with lower attachment may be less able to stop themselves after just one cigarette. More research is needed in order to understand the mechanisms linking maternal-fetal attachment to smoking behaviors in pregnancy.

Limitations of this study include our small sample size and lack of biochemical verification of maternal smoking prior to study enrollment. Additionally, while the maternal-fetal attachment scale has demonstrated reliability in past research (13), the possibility exists that women inaccurately reported feelings of fetal attachment. Future directions for research on maternal attachment include the potential to observe maternal-infant attachment as a means of understanding potential bias in self-reports of attachment.

In summary, in this study we found that, among pregnant women who smoke, those with more feelings of affiliation and attachment to their fetus smoke fewer cigarettes per smoking occasion and have lower salivary cotinine concentrations than women with lower feelings of fetal attachment. These findings suggest that maternal-fetal attachment may be an important factor in understanding smoking behaviors during pregnancy, and may serve as a target for future smoking cessation interventions. Future directions of research regarding smoking and attachment might include a similar review and comparison of attachment behaviors for pregnant quitters and pregnant non-smokers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA019558) to L.R.S. and a Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Clinical Innovator Award to L.R.S.

References

- 1.Andres RL, Day MC. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco use. Seminars in Neonatology. 2000;5:231–341. doi: 10.1053/siny.2000.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services, U. S. D. o. H. a. H . The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A report of the surgeon general. (O o S a Health, Trans) Rockville: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannover W, Thyrian JR, Roske K, et al. Smoking cessation and relapse prevention for postpartum women: Results from a randomized controlled trial at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newport DJ, Brennan PA, Green P, et al. Maternal depression and medication exposure during pregnancy: comparison of maternal retrospective recall to prospective documentation. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008;115:681–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffney KF, Beckwitt MA, Friesen MA. Mothers’ reflections about infant irritability and postpartum tobacco use. Birth. 2008;35(1):66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quesada O, Gotman N, Howell HB, et al. Prenatal hazardous substance use and adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2012;25(8):1222–1227. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.602143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford JT, Tolosa JE, Goldenberg RL. Smoking cessation in pregnancy: why, how, and what’s next. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;51(2):419–435. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816fe9e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiSantis KI, Collins BN, McCoy AC. Associations among breastfeeding, smoking relapse, and prenatal factors in a brief postpartum smoking intervention. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):582–586. doi: 10.3109/00016341003678435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauria L, Lamberti A, Grandolfo M. Smoking behaviour before, during, and after pregnancy: the effect of breastfeeding. Scientific World Journal. 2012 doi: 10.1100/2012/154910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Studies, O. o. A. Results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alhusen JL, Gross D, Hayat MJ, et al. The influence of maternal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income urban women. Research in Nursing and Health. 2012;35:112–120. doi: 10.1002/nur.21464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindgren K. Relationships among maternal-fetal attachment, prenatal depression, and health practices in pregnancy. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24:203–217. doi: 10.1002/nur.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1996;18(2):188–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cranley MS. Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nursing Research. 1981;30(5):281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh RA. Effects of maternal smoking on adverse pregnancy outcomes: examination of the criteria of causation. Human Biology. 1994;66(6):1059–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dum M, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Heinecke N, Voluse A, Johnson K. A quick drinking screen for identifying women at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(9):714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenton TR, Sauve RS. Using the LMS method to calculate z-scores for the Fenton preterm infant growth chart. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;61(12):1380–1385. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benowitz NL. Cotinine as a biomarker of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Epidemiologic Reviews. 1996;18(2):188–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobell IC, Brown J, Leo GI, et al. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salimetrics. High sensitivity salivary cotinine quantitative enzyme immunoassay kit 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savage C, Wray J, Ritchey PN, et al. Current screening instruments related to alcohol consumption in pregnancy and a proposed alternative method. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2003;32(4):437–446. doi: 10.1177/0884217503255086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dum M, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, et al. A quick drinking screen for identifying women at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(9):714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slade P, Laxton-Kane M, Spiby H. Smoking in pregnancy: the role of the transtheoretical model and the mother’s attachment to the fetus. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(5):743–757. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]